Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.51 São Paulo 2021 Epub 27-Ago-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147218

BASIC EDUCATION, CULTURE, CURRICULUM

ASSESSMENT OF A PEER TUTORING PROGRAM FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

IUniversidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos (SP), Brazil; kerenhcm@gmail.com

IIUniversidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos (SP), Brazil; gerusa@ufscar.br

The objective of this study was to propose a Peer Tutoring program, in an elementary school - final grades, and to verify its influence on the participation from the Target Audience of Special Education (TASE). A TASE student, three tutor students, a Portuguese Language teacher and a Math teacher were the participants. The data collection procedure involved five sessions of initial observation, thirty sessions of continuous observation, eight tutoring meetings and six initial and final interviews. The content analysis technique was used for data treatment. It was evident that the Peer Tutoring contributed to the inclusion of the student with intellectual disability, in terms of interactions and his ability to respond to the activities proposed in the classroom, which culminated in increasing his participation and academic and social improvements.

Key words: SPECIAL EDUCATION; INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY; PEER TUTORING; INCLUSION

O objetivo do estudo foi propor um programa de Tutoria por Pares, no ensino fundamental - anos finais, e verificar sua influência na participação de um aluno público-alvo da educação especial (PAEE). Participaram um aluno PAEE, três alunos tutores, um professor de Língua Portuguesa e um de Matemática. A coleta de dados envolveu cinco sessões de observações iniciais, trinta contínuas, oito reuniões de tutoria e seis entrevistas iniciais e finais. Utilizou-se a técnica de análise de conteúdo para o tratamento dos dados. Evidenciou-se que a Tutoria por Pares contribuiu para a inclusão do aluno com deficiência intelectual no âmbito das interações e na sua capacidade de resposta às atividades em sala, o que culminou no aumento da sua participação e melhoras acadêmicas e sociais.

Palavras-Chave: EDUCAÇÃO ESPECIAL; DEFICIÊNCIA INTELECTUAL; TUTORIA POR PARES; INCLUSÃO

El objetivo del estudio era proponer un programa de Tutoría entre Pares, en la enseñanza primaria - años finales, y verificar su influencia en la participación de un estudiante público-objetivo de la educación especial (PAEE). Participaron un alumno PAEE, tres alumnos tutores, un profesor de Lengua Portuguesa y uno de Matemáticas. La recopilación de datos incluyó cinco sesiones de observaciones iniciales, treinta observaciones continuas, ocho reuniones de tutoría y seis entrevistas iniciales y finales. Se utilizó la técnica de análisis de contenidos para el tratamiento de datos. Se evidenció que la tutoría entre pares contribuyó a la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad intelectual en el contexto de las interacciones y en su capacidad de respuesta a las actividades en el aula, lo que culminó con una mayor participación y mejoras académicas y sociales.

Palabras-clave: EDUCACIÓN ESPECIAL; DISCAPACIDAD INTELECTUAL; TUTORIA EN PAREJA; INCLUSIÓN

Cette étude vise à proposer un programme de tutorat par les pairs dans les dernières années d’école élémentaire et à vérifier son influence sur la participation d’un élève appartenant à son public cible, celui de l’éducation spéciale (público-alvo da educação especial - PAEE). Un élève de la PAEE, trois élèves tuteurs, ainsi qu’un professeur de langue portugaise et un professeur de mathématiques y ont participé. La récolte des données a comporté cinq séances initiales, trente séances d’observation en continu, huit réunions de tutorat et six entretiens réalisés au début et à la fin de l’étude. La technique d’analyse de contenu a été utilisée pour traiter les données. Il a été mis en évidence que le tutorat entre pairs favorise l’inclusion des élèves ayant une déficience intellectuelle dans les interactions de classe et augmente leur capacité à réagir aux activités qui y sont proposées, conduisant à une augmentation de leur participation et à des améliorations d’ordre scolaire et social.

Key words: ÉDUCATION SPÉCIALE; HANDICAP INTELLECTUEL; TUTORAT ENTRE PAIRS; INCLUSION

The right of the target group of learners with special educational needs (SEN)1 to receive quality education has been regulated by a large number of legislative texts, world meetings and documents, guaranteeing such students accessibility and permanence in regular school. In Brazil, Law no. 13,146, of July 6, 2015, known as the Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (Statute of Persons with Disabilities), Chapter IV, On the Right to Education, article 28, three items emphasize that there must be improvement in educational systems to ensure access, permanence, learning and participation, adopting individual and collective measures in environments that seek the academic and social development of students with disabilities.

Searching for teaching strategies that guarantee the participation of everyone and meet the different educational needs of students is a challenge for educational systems. In this sense, Duran and Vidal (2007) state that cooperative learning, based on heterogeneity is a methodology that: a) recognizes diversity; b) obtains an educational benefit from it; c) transforms the differences between students into a positive element that facilitates learning; d) makes the diversity of knowledge levels a facilitating element of the teacher’s role, as it enables learning among peers, making students responsible for their own learning and their peers. Bowman-Perrott et al. (2013), when carrying out a meta-analysis study on the subject, state that Peer Tutoring is an effective intervention that does not depend on the degree, schooling level or disability condition. Among students with disabilities, those with emotional and behavioral disorders benefited the most, which makes Peer Tutoring an ally in promoting academic achievement in the content and effective areas for elementary and secondary education (Bowmann-Perrott et al., 2013). Firmiano (2011) states that cooperative learning in the classroom encourages students to work together and help each other, using content discussion as a way to facilitate understanding of a problem, which indicates that this strategy allows for interaction between peers and gain autonomy and responsibility in decision-making. In this sense, the author highlights some advantages of the aforementioned cooperative learning methodology: a) stimulates and develops social skills; b) creates a stronger social support system; c) encourages responsibility for others; d) raises self-esteem; e) creates a positive relationship between students and teachers; f) encourages critical thinking; g) helps students to clarify ideas through dialogue; h) develops oral communication skills; i) improves content recall; and j) creates an active and investigative environment.

In this context, evaluating peer tutoring (PT) acquires its scientific relevance when it proposes to investigate a collaborative strategy in everyday school life that can: favor the participation of the SEN learners, providing conditions for them to participate in the proposed activities; result not only in the academic gain but also social gain; be, for teachers, a source of support to meet the needs of all students in such heterogeneous classes. Therefore, the possibility of using PT was investigated, as this is a didactic resource that values mutual cooperation between students and respect for differences. Duran and Vidal (2007, p. 14) emphasize that PT is a strategy to meet diversity that enables the student with difficulty - tutored - to find “personalized assistance” and gives those who will collaborate in this learning - tutor - an opportunity to deepen the student’s knowledge.

In Brazil, the topic of PT, in general, is still poorly studied, with a low number of publications. However, studies such as: Orlando (2010), Fernandes and Costa (2015), applied to students with visual impairments; Souza et al. (2017), applied to students with intellectual disability (ID) associated with autism spectrum disorder; Pereira (2018), applied to a student with cerebral palsy, and Ramos et al. (2018), applied to students with autism, corroborate the idea that PT is a strategy that can be effective and improves the academic and social performance of SEN learners.

The establishment of cooperative relationships in tutorial action in school contexts is relevant not only as a development and learning mechanism, but also as a teaching strategy that allows the SEN learner to celebrate diversity and acquire basic and functional social skills and attitudes to democratic functioning and for the knowledge of society (Duran & Vidal, 2007). Hoot et al. (2012) cite the five models most frequently used in the tutoring action: 1) Peer Tutoring of the whole class; 2) Peer Tutoring between ages; 3) Peer Assisted Learning Strategies; 4) Reciprocal Peer Tutoring; 5) Tutoring by peers of the same age. For the tutor-tutee dyad to work, it is necessary that the students who will be tutors are trained to play the role of collaborating with the tutee’s learning. Students must have an interaction script that allows them, at any time, to know what they have to do according to the role they play. Prior training, especially for tutors, is a fundamental requirement to transform the collaborative interaction into a true tutoring relationship in which each member of the pair plays their role.

An inclusive education must focus on teaching the individuals and not their disability, and this implies a restructuring of the school system, emphasizing teaching, the school and the opportunities for learning, as well as the resources and support/assistance that may promote the academic success of the SEN learner (Jannuzzi, 2012).

Planning this support/assistance should involve five basic components: identification of desired life experiences; setting goals to be achieved; determining the intensity of support/assistance needed to achieve these goals; development of individual support plan; monitoring/following-up progress and evaluation. (Almeida, 2012, p. 60).

Given the above, the aim of this study was to investigate the use of the PT strategy as personalized support/assistance to a SEN learner and to assess whether this collaborative strategy in daily school life favored the participation of this student in the proposed activities.

Methodological aspects

The research was based on a qualitative and applied methodological approach (Gil, 2008). As for the procedures, a field research was carried out (Marconi & Lakatos, 2003). The study was submitted to and approved by the Committee on Research with Human Beings of the Federal University of São Carlos, Opinion no. 96205918.1.0000.5504.

Participants

Two teachers participated in the research, one of Portuguese Language (male, 45 years old and 24 years of experience in teaching) and one of Mathematics (female, 41 years old and 11 years of teaching), as the tutoring sessions took place in the classes of these disciplines - which were selected because they have a higher workload than the other disciplines, six weekly classes (Resolution SE-30, of July 10, 2017), which allowed a longer time of interaction between the tutor and the tutee.

As for the participating students, after initial observation and in consultation with teachers, three students were selected as tutors (two girls and one boy, all 13 years old), according to the following criteria: empathy, ease of interaction with peers and teachers, class attendance, emphasis on academic skills, effective participation in classroom activities, responsibility, and expressing interest in participating in the program. Classmates from the same class and age were chosen because, according to the literature, from the point of view of learning and involvement, dyads of students of similar ages are better than dyads formed by students of different ages. It was also decided to have more than one tutor to avoid fatigue arising from the tutoring sessions and also so that the tutored students could exercise their ability to interact with more than one peer, not becoming dependent on a single peer tutor (Duran & Vidal, 2007).

The tutored student selected for the study was appointed by the school and was registered with the São Paulo State Department of Education (Secretaria de Educação do Estado de São Paulo - SEDUC) as a student with intellectual disability (ID), which guaranteed his enrollment in the Resource Room, attended in the extraclass period, twice a week. In the afternoon, he was enrolled in a regular classroom, 8th grade (corresponding to the 3rd grade of Middle School in the US), with 25 students, 16 boys and 9 girls. According to the records of the school, the tutee presented delays in his academic development and emotional problems, for which he used medication. The school team identified special educational needs in his school trajectory and presented a medical report that indicated additional psychopedagogical support for his school activities, which justified his selection for the present study.

All participants and their respective guardians consented to the research.

Research environment

The school where the study took place is located in a small city in the hinterlands of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, with 3,246 inhabitants. It is the only state school in the city and attends Elementary School students - final grades and High School students. This school was chosen because of the proximity the researcher had with the institution and because the school has a Resource Room. At the time, the school had 312 students enrolled, 208 at Elementary School and 104 at High School. Of these, ten attended the Resource Room. The school’s staff, at the time of the research, consisted of 24 teachers, three school organization agents, three secretaries and three cleaners. The management team had a substitute principal, a vice- principal and a pedagogical coordinator teacher who attended to both segments.

Data collection instruments

To carry out this study, two types of instruments were used: systematic and non-participant initial and continuous observation scripts and initial and final semi-structured interview scripts.

Data collection procedures

The research design took place in three stages. The first, Elaboration of the peer tutoring program, consisted of five sessions of systematic and non-participant observation carried out in the classroom, prior to the formation of dyads, in order to collect information about the behavior of the tutored student and other peers. The data were registered in the initial observation script, taking into account the following categories: a) relationship between the teacher and the research target student and other students; b) interaction of the tutor with peers and their level of participation in the activities proposed by the teachers; c) participation of other students in the classroom, with emphasis on those indicated by teachers as students with favorable characteristics to be tutors. Also at this stage, the initial semi-structured interviews with participating teachers and students took place.

In the second stage, Implementation of the Peer Tutoring program, careful planning was necessary. This program followed nine essential steps suggested by Topping (2005): 1) Context - analysis and selection of the SEN learner who should participate in the program, which class, which teachers, which disciplines; 2) Objectives - what is intended to be achieved by implementing the program; 3) Curriculum area - which disciplines will implement the program in class; 4) Selection and training of pairs - through initial observations in the classroom and consultation with teachers; 5) Structure and method of tutoring - choice of the five tutoring models will be adopted; 6) Training of tutors, training of teachers and preparation of tutees - key to the success of the entire program; 7) Sessions - establishment of schedules; 8) Monitoring - through continuous observation for effective monitoring of the dyads, especially the role of the tutor; 9) Assessment - continuous. For data collection at this stage, 30 sessions of non-participant systematic observations in the performance of tutors in the classroom and eight meetings to evaluate the tutoring sessions were carried out.

In the third stage, Evaluation of the Peer Tutoring program, final interviews were carried out with all those involved, in order to analyze and evaluate the influence of the strategy on the participation of the SEN learner, the tutor-tutee relationship, the expectations of tutors and teachers involved in the tutoring action and the impressions, understanding and feelings about the tutoring, after the participation of those involved.

In Table 1, there is an overview of the program’s implementation:

TABLE 1 STAGES IN IMPLEMENTING THE PEER TUTORING PROGRAM

| STAGES | PROCEDURE | PARTICIPANTS | FOCUS OF THE OBSERVATIONS/INTERVIEWS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I Program elaboration 1.Context 2. Objectives 3. Curriculum Area 4. Selection and formation of pairs 5. Structure and method of tutoring |

Initial, systematic, structured and non-participant observation | SEN learner | Potentialities, personal characteristics, interaction with peers and participation in the activities proposed by the professors participating in the research. |

| All students in the classroom | Class participation, interaction with peers, with the SEN learner and teachers for the selection of three tutors. | ||

| Portuguese Language and Mathematics Teachers | Relationship with students and, in particular, with the SEN learner. | ||

| Semi-structured initial interview | Tutee Students chosen as tutors |

Perception about the space they occupy in the classroom. Perception about what was initially presented by the researcher regarding the program. |

|

| Teachers participating in the research | Perception about the participation of the student with ID in classes. | ||

| Stage II Program Implementation 6. Training of Tutors 7. Tutoring Sessions 8. Monitoring |

1. Continuous, systematic, structured and non-participant observation 2. Tutoring Meetings |

Tutors Tutees |

Performance of dyads during the performance of activities in the classroom (Monitoring). |

| Stage III 9. Program Evaluation |

Semi-structured final interview | Tutors Tutee Portuguese Language and Mathematics Teachers |

Perception of the SEN learner participation after the implementation of the program. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

In stage II, the training of tutors took place. Baudrit (2009) states that tutors need to be well trained and suggests the use of the PPP method: Pause, Prompt, Praise. In the study, the acronym PPP was adopted to refer to the method. The author emphasizes that the method improves the tutor’s psychosocial and interaction skills, as it requires the use of social communicative skills, such as, for example, paying attention or expressing oneself clearly and helping and giving the tutee time to think or ask questions. The three steps of the PPP method instruct the tutor to: wait for the tutee to identify mistakes and have enough time to correct them; intervene, in order to help in the investigation, if the tutee, alone, is not successful in rectifying the mistakes; and encourage self-correcting behaviors, leading the tutee to appropriately use the information provided by the tutor.

Data analysis

For the analysis of the data of this research, the technique of Content Analysis of Bardin (2010) was adopted. The procedures used to process the data are presented below.

The first of them was the Organization of Analysis, when the pre-analysis took place, through skim reading the material collected throughout the research, at which time it was decided on the documents that made up the corpus of the analysis (the records of the initial observations and records of tutoring meetings and statements from 12 interviews). Finally, the theoretical framework was organized in which the results of the analysis were treated according to the literature consulted throughout the study.

The second procedure was the Coding, when the raw data of the text were transformed into a representation of the content studied in the corpus, also obtaining the characteristics of the written or verbal messages. Three techniques followed: clipping, enumeration and classification and aggregation.

The next procedure was the Categorization, carried out in two stages - inventory and classification -, which allowed defining the ten categories around which the data were discussed, namely: a) Relation of the tutee with tutors and teachers; b) Understanding of the PT program; c) Perceptions of tutors and teachers about the PT program; d) Perceptions about expectations regarding the PT program; e) Perceptions of tutors about the training process for the tutoring action; f) Perceptions of those involved about the participation of the tutored person; g) Duration of tutoring sessions; h) Difficulties in the tutoring action; i) Self-assessment of the tutoring experience; j) Evaluation of the PT program after the end of the research in the perception of teachers and tutors.

The fourth and last procedure - Treatment of results, inference and interpretation of results - made it possible to find the answers to the research questioning, through the statements of the participants, from the answers to the interviews and the statements of the tutee and tutors in the tutoring meetings, with the objective of faithfully comparing the participation of the tutor in the classroom. At this stage, the theoretical frameworks relevant to the investigation were returned. Table 2 below shows how the categories were created.

TABLE 2 CATEGORIES’ ELABORATION

| CATEGORIES | ELABORATION |

|---|---|

| 1 - Relation between tutee and tutors/ teachers. | The initial observation and the statements in the initial and final interviews were essential to carry out the comparison of the participants before and after the implementation of the program. |

| 2 - Understanding about the PT program. | Elaborated based on the statements of tutors and teachers after training, which allowed the researcher to infer the understanding they had about the program and even return to points that were not well clarified at this point. |

| 3 - Perceptions of tutors and teachers about the PT program. 4 - Perceptions about expectations regarding the PT program. |

The statements of the tutors and teachers clearly presented what the various authors claim regarding the formation of dyads and the feeling of the participants regarding collaborating with the improvement of the student who needs help. |

| 5 - Perceptions of tutors about the training process for the tutoring action. | Presented the importance of carrying out good training with the tutors so that the tutoring sessions are well executed. |

| 6 - Perceptions of those involved about the participation of the tutee. | Data emerged that made it possible to assess the participation of the tutee before and after the implementation of the program. |

| 7 - Duration of tutoring sessions. 8 - Difficulties in the tutoring action. 10 - Evaluation of the PT program after the end of the research in the perception of teachers and tutee. |

Essential to establish the points that need to be better elaborated when implementing the Peer Tutoring strategy in a classroom. |

| 9 - Self-assessment of the tutoring experience. | It was possible to infer the presence of what the literature presents regarding the satisfaction that students involved in the tutorial action feel when participating in a PT program. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Results and discussion

The results found relate to the process of content analysis applied from the participants’ statements throughout the study and are presented in two parts: 1) results found before the implementation of the program, and 2) results found after the implementation of the program. In order to indicate the statements of the participants, the acronyms TT for the tutee, T1 for tutor 1, T2 for tutor 2, T3 for tutor 3, PLT for Portuguese Language teacher and MT for Mathematics teacher will be used.

Results found before implementing the PT program

In the first category, Relationship of the tutee with tutors and teachers, it was observed that the TT had no bond of friendship with any classmate except one who sat behind him, who was the one who helped him to carry out the proposed activities by the teachers. In the initial interview, when reporting how his classmates treated him, the TT answered only: “Well”; the tutors, in turn, about their relationship with the TT before the beginning of the program, answered2 (Table 3):

TABLE 3 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON THE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE TUTEE

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “I don’t have much of a friendship with him, but I know him well enough to help him.” | T1 |

| “Good. We have no indifferences.” | T2 |

| “It’s not a great friendship, but I know him to the point of knowing what I need in order to be his tutor.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interview with the tutors.

When asked about his relationship with the teachers, TT replied that some helped him and others did not. In a tutoring meeting, he said that the Mathematics teacher was nice, had patience with him, explained well and praised him a lot, but since he could not read or write, the Portuguese teacher thought he did not want to do the activities.

In the second category, Understanding about the Peer Tutoring program, when TT was asked in the initial interview if he understood how his participation in the research would take place, he replied: “Are you going, how to say? You are going to talk, then you are going to talk to the teachers and students”. The continuation of the dialogue was: Who will these students be? “Tutors” (TT). And these peer tutors what will they do? “They is going to sit with me and help me” (TT). Duran and Vidal (2007) state that tutors are satisfied with the help of a peer to the detriment of the prejudice that holds that students tend to reject the help of their peers and seek help from the teacher (p. 36).

After four days of training the tutors, they reported what they understood about the PT strategy (Table 4):

TABLE 4 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON UNDERSTANDING THE PEER TUTORING STRATEGY

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “It’s when two students study together, in classroom activities.” | T1 |

| “It’s a moment when one student with more ability helps to improve another student´s learning.” | T2 |

| “Peer tutoring can be interpreted and understood as a way to encourage the tutee to develop himself and for that there is a tutor who will help him.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interview with the tutors.

After training, the teachers were able to understand a significant aspect of the tutoring action, which is the benefit it brings to the classes (Table 5).

TABLE 5 TEACHERS’ STATEMENTS ON UNDERSTANDING THE PEER TUTORING STRATEGY

| Teachers’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “I believe it is a very useful strategy for the teacher and also for students, both for tutors and students with some specific difficulty.” | PLT |

| “Certainly the investigation process will be beneficial both for the improvement of my practice and for the student’s learning.” | MT |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interview with the teachers.

Duran and Vidal (2007) emphasize that teachers should take advantage of the ability to cooperate among students and, precisely, see the differences between students as an enriching and helpful element in the educational task (p. 14). The authors claim that many teachers believe that they will lose control of the class and have discipline problems if they use cooperative work, but, on the contrary, the results of cooperative work encourage students to take control of the rules, regulating peers and themselves and that all this change in the classroom should be under the supervision of teachers (p. 36).

In the third category, Perceptions of tutors and teachers about the program, tutors demonstrated that they understood that they were chosen because of their school performance (Table 6).

TABLE 6 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON THE FEELING OF HAVING BEEN INVITED TO BE TUTORS

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “I felt that I am an exemplary student, good to be a tutor.” | T1 |

| “I thought it was cool, but at the same time, I don’t know if I’ll be able to take on all this responsibility.” | T2 |

| “I felt happy to be able to help someone with my knowledge.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interview with the tutors.

Duran and Vidal (2007) state that tutors feel that the tutee’s learning will depend on the level of help they will provide and this will cause them to get emotionally involved in the quality of this relationship, of which, for the role they play, is the maximum responsibility (p. 47), which is in line with the T3 statement. It was he who, during the entire process, worked most with TT in Mathematics classes.

As for the teachers, they were very satisfied with having been chosen to participate in the research (Table 7).

TABLE 7 TEACHERS’ STATEMENTS ON THE FEELING OF HAVING BEEN CHOSEN TO PARTICIPATE IN THE RESEARCH

| Teachers’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “It’s great to be able to collaborate with initiatives that support those who need this most, especially students with a greater degree of difficulty, as often the teacher, for various reasons, is unable to pay more attention to them.” | PLT |

| “I feel very honored and grateful for the opportunity.” | MT |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interview with the teachers.

Regarding the fourth category, Reports on expectations regarding the Peer Tutoring program, the statements in the initial interviews, after the presentation of everything that would happen during the program, revealed the hopes of the participants placed in a strategy that would be implemented with the objective of evaluating the participation of a student who, until then, had not had good quality participation in the classroom, as shown in Table 8:

TABLE 8 PARTICIPANTS’ EXPECTATIONS REGARDING THE PEER TUTORING PROGRAM

| Tutors’ and teachers’ answers | PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|

| ““Because they [the tutors] is going to help me.” | Tutee |

| “That everything will be all right.” | T1 |

| ““It is going be difficult, hard and it will not be easy.” | T2 |

| “I think it is going result in a great research.” | T3 |

| “I hope that tutors can help to solve learning problems, help reduce the difficulties of peers and improve some friend relationships within the classroom.” | PLT |

|

“I believe that studying will improve the quality of my classes.” “It can help students with disabilities and can also contribute to the classroom’s awareness of the topic and encourage them to live with diversity.” |

MT |

|

“It can be positive when a classmate manages to make the other understand certain contents that are not yet fully mastered, in addition to promoting closer ties between students through partnership. I believe the classes will become more interesting, they can be more dynamic.” “Using it [PT strategy] during classes will be very beneficial for everyone who participates in the classes, especially for the teacher, who will be able to count on extra help from the tutors.” |

PLT |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interviews.

The statement of the PLT is in accordance with the definitions presented in the literature. Duran and Vidal (2007) point out that the PT strategy shows teachers that, in class, they are not alone to carry out their educational work and that students can become allies in this task, as everyone is able to help peers who need additional support to learn. They also emphasize that this moment of interaction between students may even be beneficial to the solution of discipline problems that exist in the classroom, as the focus of learning will be the dialogue on the activities undertaken by the pairs, which will allow learning and metacognition (Duran & Vidal, 2007, p. 65), which is a great opportunity for teachers to understand how their students think.

For tutoring sessions to occur successfully, it is necessary to dedicate quality time to tutors’ training. As pointed out by Mosca and Santiviago (2013), the experience of training the dyads puts both the tutor and the tutee in an active role in relation to the learning process in academic and affective aspects, and it is precisely these aspects that support the processes of learning.

Therefore, in the fifth category, Perception of tutors about the training process for the tutoring action, the tutors were asked if the training week, prior to the beginning of the program, was enough to prepare them for the tutoring sessions (Table 9).

TABLE 9 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON THE TIME OF TRAINING FOR THE TUTORING ACTION

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “Quite a bit, but I don’t think it’s going to be that easy.” | T2 |

| “Yes, but we will still have more meetings and I will also have the help of two more peers.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interviews.

The tutors were also asked if they understood what role they would play (Table 10):

TABLE 10 STATEMENTS ABOUT THE ROLE OF THE TUTOR

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “Yes. We will have to help the tutee in the activities, explain the subjects he did not understand in an easier way, so that he understands.” | T1 |

| “The tutor must be patient during the time he is teaching the tutee, in our case, two months. Must not put pressure on the tutee, and even less feel bad if he can’t.” | T2 |

| “I am aware of my activities, responsibilities. I will have to help the tutee by pausing, prompting and praising him.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interviews.

According to Baudrit (2009), the tutors’ mission is to help their peers when they have learning problems, but also integration or insertion problems (p. 46).

In the sixth category, Perceptions of those involved about the participation of the tutored, it can be inferred that the tutors understood that, in addition to academic competence, social competence should also be stimulated (Table 11).

Before the end of the training, the researcher carried out the initial interview with the tutors and it can be inferred that they understood that not only academic competence, but social competence should also be stimulated, as shown in Table 11.

TABLE 11 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON THE INFLUENCE OF TUTORING ACTION ON TUTEE’S PARTICIPATION

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| ““To fit in and participate more in classes, improving his development.” | T1 |

| “In school performance in every way: with friends and in class.” | T2 |

| “It will help him to socialize, as he will be more encouraged and will not be shy about asking, which will help him with his doubts. That way he will be able to understand the subject. But, the most important thing is that the tutee will be more focused.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interviews (2019).

The next table presents the statements of tutors and teachers in the initial interviews regarding the participation of TT in the classroom (Table 12).

TABLE 12 PARTICIPANTS’ STATEMENTS ON TUTEE’S PARTICIPATION BEFORE IMPLEMENTING THE PEER TUTORING PROGRAM

| Tutors’ and teachers’ answers | PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|

| “He’s very quiet, doesn’t fit in very much with the others and doesn’t participate in classes.” | T1 |

| “Slow, very quiet. He has difficulties and doesn’t express himself much in class.” | T2 |

| “Not very good. He’s ashamed of himself and he’s also distracted and that doesn’t do him any good.” | T3 |

| “The student has very little interaction during classes. He talks to some peers too, but not all of them, as he’s a little aloof. He contacts the teacher only to ask to go to the bathroom or go and drink water. When answering the attendance checklist, he usually forgets and some peers have to remind him of this detail. He has a lot of difficulty in everyday tasks, he doesn’t ask when he has any questions. At times, he seems to be feeling sick, sometimes he cries.” | PLT |

| “He is apathetic. He always carries out activities with the help of a peer. He does not participate by giving his opinion or answering any questions.” | MT |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the initial interviews.

Results found after implementing the PT program

In the first category, Tutored relationship with tutors and teachers, the tutors confirmed that there was an evolution in the interaction with the TT (Table 13).

TABLE 13 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON INTERACTION WITH THE TUTEE DURING THE SESSIONS

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| “At first he didn’t show interest. He even thought about giving up, but now he’s even participating more in classes.” | T1 |

| “I was honest with him. Always speaking the truth, that’s how we got closer.” | T2 |

| “He is much more confident about talking to me now than he was in the beginning and we ended up becoming friends.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the final interview with the tutors.

This relationship established in a tutoring action promotes social interactions between those involved, as tutors are able to listen, advise and provide information to the TT when he experiences difficulties, which leads him to acquire trust in the tutors (Baudrit, 2009). It was observed that this relationship with the tutors extended to other peers in the classroom, because, unlike the week in which the initial observation was carried out, the TT left his desk to talk with other peers and they also came to his desk to borrow some material or to chat.

At the end of the program, the statements in the final interviews allow us to infer that the relationship of the participants has changed. When TT was asked if receiving help from a classmate made a difference in his daily life at school, his answer was:

It did. Before, I had no friendship with R. (T3) and G. (T1). With I. (T2) I had. Now we are friends and we even went to sleep at another peer’s house. And the next day R. (T3) and I. (T2) and her sister went to eat at my house. This has happened twice already. It had never happened before. I think the three tutors like me a lot. Being friends with them was better than having improved in the activities (TT).

In the fifth category, Perception of tutors on the training process for the tutoring action, based on continuous observations carried out throughout the program, it is believed that the time of one week used for the training of tutors was sufficient for the work carried out in this research. However, it is noteworthy that, in another situation, with more tutees and tutors and, depending on the condition of disability that requires broader training to know how to deal with different characteristics, more time should be reserved for that training.

The next table presents the statements of tutors and teachers in the final interviews (Table 14), which express a change in the participation of the TT, both in academic and social competence, but particularly in social competence:

TABLE 14 PARTICIPANTS’ STATEMENTS ON TUTEE’S PARTICIPATION AFTER THE PEER TUTORING PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

| Tutors’ and teachers’ answers | PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|

| “I know I helped him a lot. He really needed it. At least he received a little more knowledge and also became more confident. He’s even talking too much.” | T1 |

| “I feel fulfilled, but next year I intend not to participate in this program anymore, because if he doesn’t improve, I wouldn’t be happy, as I would find myself unable to help someone. And it was also good because we became friends.” | T2 |

| “Very happy to know that the little intelligence I have I can develop it more by helping him. I feel like everything is in place. Duty accomplished. Besides having befriended him. He’s even talking in class, which he didn’t do before. So I think I helped with everything, right?” | T3 |

| Tutors’ and teachers’ answers | PARTICIPANTS |

|

“Yes, as much as I could, in relation to what he was able to do, he improved. It is interesting to note that the tutee was somewhat dependent on the tutors and did not do anything without them.” “In the sense of feeling like a person, receiving attention from peers and being able to occupy more space in the classroom. The student with ID was noticed more and they wanted to help him.” “The student continued to interact very little with the teacher, but with some peers, including non-tutors, he even started to debate in some cases.” |

PLT |

|

“As said earlier, the student is much more confident and participatory.” “The student is more relaxed, participates more in different activities, asks more and has developed a better logical reasoning.” |

MT |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the final interviews with tutors and teachers.

It is noteworthy that, during the tutoring sessions, the PPP method was used and it is believed that it was essential for the program to run smoothly. The tutors tried to forward the session in the following order: first they explained the activity and waited for the TT’s response; then, when he did not respond or responded unsatisfactorily, they intervened, trying to explain in another way; at the end of the sessions, they always gave feedback, encouraging him to persist. The researcher insisted on this method, because it was a way to prevent the tutors - when explaining the activity, if the TT could not do it - from delivering a ready answer. It is important to inform the TT that the method will be used, so that he is aware that the performance of activities by him is linked to these three steps.

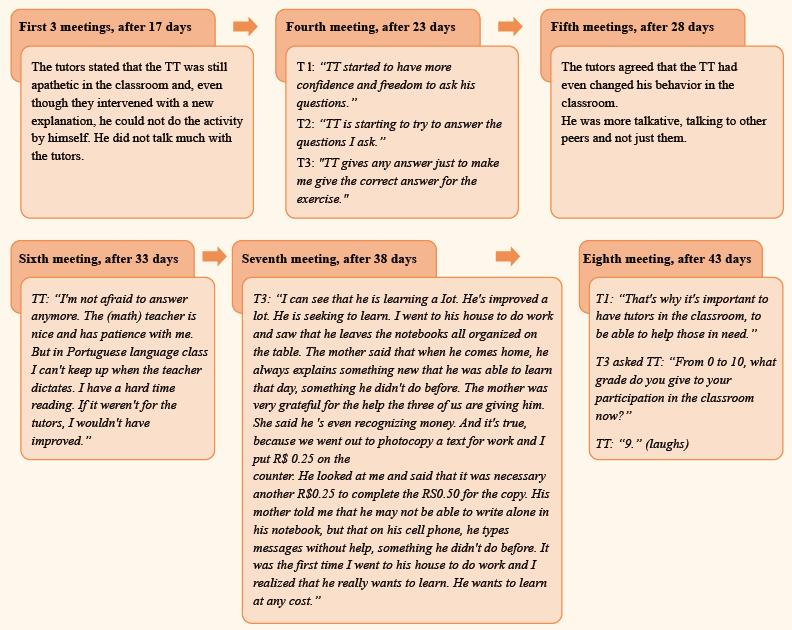

Tutoring meetings were times dedicated to evaluating the tutoring sessions. A total of eight meetings were held. A brief timeline with important facts that marked each one is presented below.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on records of the tutoring meetings (2019).

FIGURE 1 TUTORING MEETINGS’ TIMELINE

At the last tutoring meeting, an evaluation of the program was carried out. In it the tutors reported that they felt that they themselves had changed, as they realized how difficult it is for a person to want to learn and have difficulty, and how difficult it is to teach. The TT reported:

I’m happy because I’m doing the quizzes. I improved more in Mathematics than in PL. My biggest difficulty is reading and writing. I want to thank my friends [at first he referred to tutors as peers] who helped me. Before, my mother would look at my notebooks and would ask what I learned at school and I didn’t know how to say. Now I explain. And I also liked it because they go to my house (TT).

To complete the study, tutors were asked if they would like to continue with the sessions. The three tutors said yes, but that they would like new tutors to be trained so that they can rest a little (Table 15).

TABLE 15 FEELINGS OF THE TUTORS TO CONTINUE WITH THE TUTORING ACTION

| Tutors’ answers | PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|

| “Yes. Although it’s a lot tiring, but I know I’m helping someone in need.” | T1 |

| “Yes, but it’s very tiring. Next time, I might get a reward for my effort. A toast, anything (laughter).” | T2 |

| “Yes and no. I really want to prioritize myself now and I know that it won’t be easy with him.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from observations of tutoring meetings.

After the end of the program, the assessment of the use of the strategy began, through the final interviews. In the seventh category, Duration of tutoring sessions, participants reported whether the time allocated to the sessions was sufficient or not (Table 16).

TABLE 16 PARTICIPANTS’ VIEW ON THE DURATION OF TUTORING SESSIONS

| Tutors’ and teachers’ answers | PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|

| “Yes. I think it was.” | T1 |

| “No, because he didn't learn enough, especially in Portuguese, which hasn't evolved much.” | T2 |

| “Yes. More has happened than I expected and I feel that if I keep helping him he will improve even more.” | T3 |

| “Depending on the activity performed, it was sufficient, as the tutors helped the peer a lot.” | PLT |

| “Yes.” | MT |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the final interviews.

The authors consulted do not determine an amount of time that should be allocated to the tutoring action. Duran and Vidal (2007) leave it up to the teacher to arrange the time in which the sessions will take place, whether inside or outside of school hours, and also cite a PT experience that was carried out within a context of structured format in weekly sessions of 45 minutes, over a period of two and a half to five months, with five pre-initial training sessions (p. 45). Baudrit (2009, p. 15) cited a successful PT experience in which sessions were spread over eight weeks, at the rate of three sequences of forty-five minutes per week (p. 15). Hoot et al. (2012) consider that “peer tutoring can occur two to three times per week for 20 minutes” (p. 3). In this program, the dyads worked a total of 100 classes, with daily meetings of 50 or 100 minutes when there were two classes together.

According to the results obtained, it is believed that this time should vary according to each situation: number of students involved, type of disability and the place where the tutoring action will take place. The important thing is that there is careful planning so that this time is significant for the work of the dyads and so that, at the same time, it prevents the tutors from getting tired.

In the eighth category, Difficulties in tutoring action, it can be seen how the implementation of this strategy has to be carefully elaborated. Arguis et al. (2002, p. 16) warn that tutoring is not the work of a day, it is an interactive work between everyone. There is a danger of drawing a profile so perfect that it is impossible or that it seems so impossible to the tutors that they give up straight away (p. 16). Through continuous observations, four situations were listed that caused fatigue to the tutors: 1) explaining the same exercise three, four or even more times and in different ways, which required patience and skills; 2) working with the TT before they perform the exercise themselves, which reduced their time to perform the activity in the notebook; 3) asking the teacher about any doubts so as not to explain wrongly to the TT, which they would not normally do, as the doubt would be clarified at the time of collective correction, but this situation could not be expected because the orientation to the TT happens before this moment of solution of doubts; 4) being careful when talking to the TT so as not to create any embarrassment. For this reason, it is believed that it is essential to have more tutors so that a better division of the time allocated to tutoring sessions is possible.

In the ninth category, Self-assessment of the tutoring experience, the TT statement demonstrates how benefited he felt through the use of the strategy:

It was cool. It was fun. I got better at other things outside of school, like counting money and texting on WhatsApp. I was just able to add numbers. Now I can subtract, multiply and divide. I managed to improve my reading a little. Before, I couldn’t write any message on WhatsApp. Now I can write a little bit. I text my father and aunt. I couldn’t read the names on the cell. I asked my mother to read it. Now I read almost all of them. (TT)

When asked what he liked most about being tutored, TT replied: “I liked more that I was able to do more things”. When asked what he liked least, TT said: “I couldn’t improve much in Portuguese”. About what he thinks did not work out, TT stated: “It all worked out”. We can infer that he was more confident because he was able to perform activities that he was unable to do before. Regarding this, Fulk and King (2001) highlight that PT seems to be particularly beneficial in improving the self-esteem of TT who have low social and academic performance. But it was not only the TT that felt the benefits of the strategy in their daily lives, as can be seen from what the tutors declared (Table 17).

TABLE 17 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON THE FEELING OF HAVING BEEN TUTORS

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

|

“For me it was very good because I know that I helped someone and also improved in my learning.” “I can’t say for sure, but it was a very important experience for my growth.” |

T1 |

|

“Difficult, but a lot of it felt good to be helping the tutee and I also ended up helping myself.” “I don’t know how to answer very well because it was a mixture of a lot. I can only say that it was really cool.” |

T2 |

|

“It was great and bad at the same time. Bad when I saw what he couldn’t do. I felt bad, but I never thought about giving up.” “What I liked the most was being praised by the tutee and the teachers. It was a recognition.” |

T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the final interviews.

The need to help another peer to solve problems that he alone cannot make the tutor organize his own cognitive process to be able to transmit the content more clearly to the TT. The perception of the cognitive benefit that the tutor acquired when performing his role was portrayed in the tutors’ statements (Table 18).

TABLE 18 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON THE FEELING OF HAVING ACTED AS TEACHERS

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

|

“I think this experience was good even for me, because I improved in my learning and helped mainly in the tutee’s learning.” “I felt important, I felt happy helping someone in need.” |

T1 |

|

“I think this sentence says everything about tutoring, not just for school, but for life. I learned more by teaching a tutee.” “I thought it was bad being a teacher because a teacher suffers to try to make students learn. But on the other hand I helped myself by helping the tutee and I felt like an important person.” |

T2 |

|

“I think it makes a lot of sense because, when you want to teach, you dedicate your best effort not to teach anything wrong and try to teach in the best way to resolve it. Thus, helping the tutee, the tutor helps himself.” “Cheered up! Each day I wanted to teach him something he would use to solve questions or read. I wanted to help him in some way.” |

T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the final interviews.

But, when asked about what they liked least, the tutors reported feeling frustrated. In this sense, it is important to demonstrate to tutors, throughout the program, that there is a special concern for them. Table 19 below presents the aspects with which tutors felt most uncomfortable when performing their role.

TABLE 19 TUTORS’ STATEMENTS ON WHAT THEY LIKED LEAST ABOUT BEING A TUTOR

| Tutors’ answers | TUTORS |

|---|---|

| ““Just the fact that he didn’t know how to read got in the way a little.” | T1 |

| “Having to keep spelling, repeating again and again and not knowing how to teach issues I didn’t know myself.” | T2 |

| “Having to prioritize him and forget about me for a while.” | T3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the final interviews.

The tenth category, Evaluation of the Peer Tutoring program after the end of the research in the perception of teachers and tutees, was important, as it allowed us to really understand the impact that the program had on the participants’ lives. When asked if he thought other students deserved this same opportunity, the TT replied: “Yes, because becomes a friend and learn” (TT). And, when asked if he would like to continue receiving this incentive after the end of the research, the TT said: “Yes, of course”. These statements are in line with what Arguis et al. (2002) state about the PT strategy: it can give rise to improvement from academic performance to interpersonal relationships (p. 79) and the notes of Duran and Vidal (2007) when they state that PT creates an environment in fundamental classroom for good affective and interpersonal results (p. 17). Teachers were asked if they would continue using this strategy in their classes or if it only served to collaborate with the research. The PLT replied that they were already using the strategy in other classes and that they realized that the student with ID felt more supported to carry out the work and that, for sure, they would continue to adopt that strategy. The MT also said he would continue to use it in his classes.

The data analysis is concluded with the teachers’ statements in the final interview, when the motivation that the tutee and tutors had to carry out the activities using PT was questioned (Table 20).

TABLE 20 TEACHERS’ STATEMENTS ON THE MOTIVATION THAT THE PROGRAM PROVIDED TO THE TUTEE AND TO THE TUTORS

| Teachers’ answers | TEACHERS |

|---|---|

| “For the tutors it was an excellent moment to demonstrate collegiality; for the tutee, it was the opportunity to see themselves as a person, to be remembered and helped by others.” | PLT |

| “The tutee is much more confident, participative and happy. It was also a rewarding experience for the tutors for having the opportunity to learn and live with diversity.” | MT |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the final interview.

Final considerations

Ensuring the participation of the SEN learner is a right earned by law, but the support services centered on Resource Rooms often become ineffective for this purpose. Thus, it is the school’s duty to identify and work as best as possible the different possible strategies and designs that meet the needs of students, adapting to the specificities of each one, promoting academic skills and social interaction between them through strategies that enable the acquisition of such skills. In this sense, the analysis of the data in this study indicated that the PT strategy can be associated with other educational support services provided for SEN learners in the regular educational system.

The results, however, indicate five issues that deserve attention and better planning for their conduct. The first issue refers to the number of tutors. It is important that this amount is sufficient for the demand required in the tutoring sessions, in order not to overload them. A second issue is the dependence that is established between tutees and tutors. To avoid it, a solution would be to reduce the frequency of intervention by the tutors. In this program, they sat next to each other during all tutoring sessions. One could think of a situation in which the tutees established the moment when they would no longer need this continuous assistance, making it clear that they could seek help from the tutors whenever they felt the need.

The third issue is the affinity of the tutees with the teachers who will use the strategy in their classes. It is necessary for them to have good interaction with the teachers. The fourth question refers to the time of implementation of the program. It is noteworthy that this study was carried out in a short period of two months and in only two disciplines of the school curriculum. There is a need to consider aspects of maintaining strategies throughout a school year. Thus, it is considered that further investigations are needed, addressing other populations, different demands in the schooling process, a larger sample of participants, and different classes. It is also necessary to assess the impact of tutoring on the academic performance of tutors and not only those being tutored, improve the partnership between teachers in the regular classroom and those from Special Education and reformulate the aspects mentioned as points that deserve better elaboration, so that they can improve and learn more about the possibilities that PT offers and whether it applies to all SEN learners in the regular Brazilian educational system. The fifth issue refers to the limits of the comparative analysis of the pre and post- -test proposed for evaluating the program. In this research, the semi-structured interviews generated a qualitative analysis of the reports, which, due to their subjectivity, may have limited the measurement of improvement indexes or not of the implemented program. In this sense, it is suggested that, in future studies, instruments that can more objectively assess the results produced are used.

Although the focus of the research is tutoring, the results of the data analysis found showed that tutors took on the simultaneous role of stimulating the participation of the SEN learner in the performance of Portuguese Language and Mathematics activities in the classroom, as well as their socialization, which contributed to the improvement of social interactions. It was revealed that the academic and emotional availability of the tutors were relevant factors for the success of this strategy, which translated into an increase in the interactive quality and quantity of the tutee’s participation in the activities proposed by the teachers and with their classmates.

Thus, even after the brief period of intervention, the role of the tutors contributed to the process of including the tutee in classes, indicating, in some way, that PT is a strategy that, if well implemented, can help SEN learners to overcome their challenges and difficulties. Evidently, this study did not exhaust the possibilities for researching the strategy; therefore, it is believed to be important to carry out new research with different populations and contexts, as well as their dissemination, presenting them as an additional resource for schools that are committed to improving the school environment. Everyone involved in the PT process can benefit in some way. For students, there is the possibility of exercising interaction, companionship, attention and new knowledge; for the teacher, the possibility of changing the planning of their classes, involving students in the teaching process. In addition, the possibility of support/assistance to the SEN learner being provided not only by the teachers, but also by the students, can collaborate with the change in the paradigm that the teacher should be solely responsible for the inclusion and development of the SEN learner. There is a change in perspective when it is proposed that students themselves can assist the teacher in mediating academic and social skills in the classroom.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (Capes) - Finance Code 001.

REFERENCES

Almeida, M. A. (org.). (2012). Deficiência intelectual: Realidade e ação. Secretaria da Educação do Estado de São Paulo. http://cape.edunet.sp.gov.br/textos/textos/Livro%20DI.pdf [ Links ]

Arguis, R., Arnaiz, P., Báez, C., Ben, M. Á. de, Diaz, F. D., Diez, M. C., Ulzurrun, A. D. de, Dorio, I., Escardíbul, S., Ferrero, J., Soler, R. G., Navarro, M. G., Rica, T. L. de L., Lorenzo, M. L., Martinez, E., Perdiguero, I. M., Masegosa, A., Medina, Â., Montesinos, C., Moncayo, A. N., Notó, F., Novella, A., Puig, J. M., Ricart, C., Senent, M. L., & Vicente, A. (2002). Tutoria: Com a palavra, o aluno (Inovação Pedagógica, Vol. 6). F. Murad, Trad. Artmed. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2010). Análise de conteúdo (4a ed.). Edições 70. [ Links ]

Baudrit, A. (2009). A tutoria: Riqueza de um método pedagógico. Porto Editora. [ Links ]

Bowmann-Perrott, L., Davis, H., Vannest, K., Williams, L., Greenwood, C. R., & Parker, R. (2013). Academic benefits of peer tutoring: A meta-analytic review of single-case research. School Psychology Review, 42(1), 39-55. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1007216 [ Links ]

Decreto n. 7.611, de 17 de novembro de 2011. (2011). Dispõe sobre a educação especial, o atendimento educacional especializado e dá outras providências. Casa Civil. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/decreto/d7611.htm [ Links ]

Duran, D., & Vidal, V. (2007). Tutoria: Aprendizagem entre iguais. E. Rosa, Trad. Artmed. [ Links ]

Fernandes, W. L., & Costa, C. S. L. da. (2015). Possibilidades da tutoria de pares para estudantes com deficiência visual no ensino técnico e superior. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 21(1), 39-56. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbee/v21n1/1413-6538-rbee-21-01-00039.pdf [ Links ]

Firmiano, E. P. (2011). Aprendizagem cooperativa na sala de aula. Programa de Educação em Células Cooperativas - Prece, 47 p. [ Links ]

Fulk, B. M., & King, K. (2001). Classwide Peer Tutoring at Work. Teaching Exceptional Children, 34, 49-53. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/004005990103400207 [ Links ]

Gil, A. C. (2008). Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social (6a ed.). Atlas. [ Links ]

Hoot, B., Walker, J., & Sahni, J. (2012). Peer tutoring. Council for Learning Disabilities. https://council-for-learning-disabilities.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Peer-Tutoring.pdf [ Links ]

Jannuzzi, G. M. (2012). A educação do deficiente no Brasil: Dos primórdios ao início do século XXI (3a ed.). Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Lei n. 13.146, de 6 de julho de 2015. (2015). Lei Brasileira de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência (Estatuto da Pessoa com Deficiência). Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil. Presidência da República. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2015/lei/l13146.htm [ Links ]

Marconi, M. de A., & Lakatos, E. M. (2003). Fundamentos da metodologia científica (5a ed.). Atlas. [ Links ]

Mosca, A., & Santiviago, C. (2013). Tutorías de estudiantes: Tutorías entre pares. Universidad de la República Uruguay. Comisión Sectorial de Enseñanza. http://www2.compromisoeducativo.edu.uy/sitio/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/libro_tutorias.pdf [ Links ]

Orlando, P. d’A. (2010). O colega tutor de alunos com deficiência visual nas aulas de educação física [Dissertação de mestrado]. Universidade Federal de São Carlos. [ Links ]

Pereira, H. M. C. (2018). O impacto da tutoria de pares nas competências de leitura de uma aluna com paralisia cerebral [Dissertação de mestrado]. Escola Superior de Educação, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra. https://comum.rcaap.pt/bitstream/10400.26/23160/2/HERMINIA_PEREIRA.pdf [ Links ]

Ramos, F. S., Bittencourt, D. F. C. D., Camargo, S. P. H., & Schmidt, C. (2018). Intervenção mediada por pares: Implicações para a pesquisa e as práticas pedagógicas de professores com alunos com autismo. Arquivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 26(23), 1-24. [ Links ]

Resolução SE-30, de 10 de julho de 2017. (2017). Conselho Nacional de Educação. Diário Oficial do Estado de São Paulo. http://siau.edunet.sp.gov.br/ItemLise/arquivos/30_17.HTM?Time=23/08/2017%2008:58:26 [ Links ]

Souza, J. V., Munster, M. V., Leiberman, L., & Costa, M.P. R. (2017). Programa de formação de colegas tutores: A tutoria no processo de inclusão escolar nas aulas de educação física. Práxis Educativa, 12(2), 373-394. [ Links ]

Topping, K. J. (2005). Trends in peer learning. Educational Psychology, 25(6), 631-645. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01443410500345172 [ Links ]

1In Brazil, the term “público-alvo da educação especial”, represented by the acronym PAEE, has been used in research in line with Decree no 7,611, of November 12, 2011, which provides for Special Education and Specialized Educational Service. The target group of learners with special educational needs is composed of students with disabilities, pervasive developmental disorders and giftedness. In this text, the term “SEN learner” will be used according to the National Policies Platform of the European Comission. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/special-education-needs-provision-within-mainstream-education-40_en

2The statements of the tutors and the tutee, throughout the work, were transcribed exactly as expressed, in Portuguese, without any spelling and/or textual correction. In this paper, they were translated trying to keep the way the subjects expressed themselves.

Received: March 21, 2020; Accepted: December 23, 2020

texto en

texto en