Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.51 São Paulo 2021 Epub 13-Oct-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147376

BASIC EDUCATION, CULTURE, CURRICULUM

EXTERNAL INFLUENCES SUCH AS ASSETS OR LIABILITIES IN STUDENTS’ EDUCATION

IUniversidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos (SP), Brasil; luanaca@ufscar.br

The article examines semi-structured interviews developed with subjects from different segments from four schools, elected by contrast, problematizing the influences outside as active or passive in the students’ school trajectory. It reveals that both the family’s and the neighborhood’s influence are perceived as potentiators, or not, of a greater use of the educational opportunity available. Going through the socialization models in the neighborhood, the material resources available at home, the exposure to the risk of violence and the possibility of experiencing extracurricular activities as elements that act as assets or liabilities, the interviewees indicate from the family organization, especially the school follow-up provided by it, to the infrastructure of the neighborhood as aspects to be considered.

Key words: SCHOOL; ACHIEVEMENT; SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

O artigo examina entrevistas semiestruturadas com sujeitos de diferentes segmentos de quatro escolas, eleitas por contraste, problematizando as influências externas como ativos ou passivos na trajetória escolar dos estudantes. Revela que tanto a influência da família quanto a do bairro são percebidas como potencializadoras ou não de um maior aproveitamento da oportunidade educacional disponível. Passando pelos modelos de socialização no bairro, recursos materiais disponíveis no lar, exposição ao risco de violência e possibilidade de vivência de atividades extraescolares como elementos que atuam como ativos ou passivos, os entrevistados indicam desde a organização familiar, especialmente o acompanhamento escolar provido por ela, até a infraestrutura do bairro como aspectos a serem considerados.

Palavras-Chave: ESCOLA; RENDIMENTO ESCOLAR; AMBIENTE SOCIAL

El artículo examina entrevistas semiestructuradas con sujetos de diferentes segmentos de cuatro escuelas, elegidas por contraste, problematizando las influencias externas como activos o pasivos en la trayectoria escolar de los estudiantes. Revela que tanto la influencia de la familia cuanto la del barrio son percibidas como potencializadoras o no de un mayor aprovechamiento de la oportunidad educacional disponible. Pasando por los modelos de socialización en el barrio, recursos materiales disponibles en el hogar, exposición al riesgo de violencia y posibilidad de vivencia de actividades extraescolares como elementos que actúan como activos o pasivos, los entrevistados indican desde la organización familiar, especialmente el acompañamiento escolar previsto por ella, hasta la infraestructura del barrio como aspectos a ser considerados.

Palabras-clave: ESCUELAS; RENDIMIENTO; AMBIENTE SOCIAL

Cet article présente des entretiens semi-structurés menés auprès de sujets provenant de segments différents de quatre écoles contrastées. Il problématise la question des influences externes dans la trajectoire scolaire des élèves pour savoir si celles-ci représentent des atouts ou des désavantages. La recherche révèle que l’influence de la famille aussi bien que celle du quartier sont perçues comme des facteurs potentiels de tirer (ou non) un plus grand profit des opportunités d’éducation disponibles. Les modèles de socialisation présents dans le quartier, les ressources matérielles dont disposent les foyers, l’exposition au risque de violence et la possibilité de s’engager dans des activités non scolaires agissent comme des actifs ou des passifs. Les personnes interrogées indiquent que l’organisation familiale, surtout le suivi scolaire à la maison, à l’infrastructure du quartier sont des aspects à considérer.

Key words: ÉCOLE; RENDEMENT; ENVIRONNEMENT SOCIAL

Distrust the most trivial, in the simple appearance. And examine, above all, what seems usual. We expressly beg: do not accept what is customary as something natural. For in times of bloody disorder, organized confusion, conscious arbitrariness, dehumanized humanity, nothing must seem natural. Nothing should seem impossible to change.1 (Brecht, 1982, p. 45, own translation)

In “Nothing is impossible to change”, we are invited by Bertold Brecht (1982, p. 45) to investigate conformity, not to resign ourselves to the evils of society, to inhumanity, to injustice. We are called to look at inequalities from their denaturalization.

Nothing should seem natural, says the poem, nothing is impossible to change... Distrusting what seems to be the most trivial on a daily basis, examining what comes covered as usual, allows us to become aware of reality in order to think about it and act on it. This is the path to be followed in the school environment as well.

As a social institution, the school cannot be seen as capable of acting independently of social conditions, nor is it incapable of making a difference in the lives of those who participate in it. Assuming your limits and possibilities in face of reality allows you to act in favor of change. A temporary change, because it is subordinate to the social order, but not less important, as it determines student trajectories.

Understanding the external influences on schoolwork, problematizing the objective conditions of life of the served population and examining the activities experienced outside of school, observing the social environment, family and territory as important assets in the students’ school trajectory, seems to be a promising path. More than understanding the resources used and available for the construction of children’s educational pathways, the analysis in this perspective enables professionals to rethink actions, demystifying prejudices and mobilizing what enhances positive effects in the process.

In an attempt to contribute to this task, this article discusses the perception of actors involved in the schooling process of elementary school students in a Public School System, analyzing the external conditions observed and presented by them as those that influence the school trajectory of children and young people. Extending the analytical unit “family”, without denying or ignoring its important influence on students, we seek to understand which aspects of the social environment are seen as influencing the school development of subjects.

Circumscribed to the debate on the mechanisms of production and reproduction of social inequalities, or, as Brecht mentions, “organized confusion, conscious arbitrariness, dehumanized humanity” (1982, p. 45), this work takes the territorial dimension as an important element of analysis. In dialogue with studies on social vulnerability, opportunity structures and the neighborhood effect, it is noticed that both the present social models and the geography of opportunities available in the territory are strong influencers on students’ school performance, being essential factors for examination.

Methodological design

To think about reality is to understand it as complex. The search for understanding the external constraints of students’ academic performance requires a research methodology that enables an attentive and rigorous approach, not with the illusion of embracing the entire phenomenon, but in order to capture evidence of its movement in the most comprehensive way possible.

The result of an investigation financed by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo [Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo] (Fapesp) on the school and its social environment (Almeida, 2014), this article aims to discuss the express association of aspects of the social environment to certain behaviors and students’ school performance. Therefore, it brings to debate data from four municipal schools in the city of Campinas (SP), whose election criterion was the contrast, based on location in social vulnerability zones and high or low performance in relation to the network average searched.2 The first pair was formed by schools located in different social vulnerability zones, but with the same school performance (E1, in a low relative social vulnerability zone, and E2, in an absolute social vulnerability zone, both with high performance3), and the second, formed by schools located in the same social vulnerability zone, but with different performances (E3, with high performance, and E4, with low performance, both in an absolute social vulnerability zone).

Product of a qualitative data collection involving participant observation, semi-structured interviews and focus groups, the data analyzed in this article focus on the examination of semi- -structured interviews developed with subjects from different segments of the school community. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, and, for their development, free informed consent forms were signed (in the case of students, the term was signed by their legal guardians). In the presentation of data, in order to honor the anonymity agreement, both schools and respondents will be identified in a coded form, by the segment they represent, followed by a random number, without the possibility of identifying the participants.

CHART 1 INTERVIEWED BY SEGMENT

| Segment | Total |

|---|---|

| Management Team | 12 |

| Teachers | 20 |

| Employees | 20 |

| Family | 40 |

| Students | 40 |

Source: Author’s elaboration, based on research data.

The methodological option is justified by its potential for gathering information about aspects of reality, including the subjects’ perception in relation to the factors of the social environment that influence students’ school performance. It is worth noting that the social environment is assumed both as a physical space (structure and available services) and as a socioeconomic and cultural space, embracing the families of students served by the school, as well as other subjects who live there and relate to them.

. . . result of a network of relationships between individual and collective subjects among themselves and between them and the environment, the biophysical space in which they are located temporally and geographically, a complex configuration that arises from numerous relationships and interferences of factors also resulting from these relationships. . .4 (Corbetta, 2009, p. 271, own translation).

The debate on external constraints on school performance

The concern with the low performance of students in school stage and its consequences is not recent and has given rise to different approaches in the search for the investigation of its causes and mapping of the actions necessary to face it. The analysis from specific aspects emerges as a way to better understand the reality of school institutions and the population served by them, seeking to understand how certain factors may or may not contribute to student performance.

Among the issues under analysis, the literature has long indicated factors outside the school as essential. Since the Coleman Report (1966), coordinated by the American James S. Coleman, it is impossible to think about the issue without embracing the strong influence of the socioeconomic level (SEL) of families on the students’ academic performance. In equal proportion, after the contributions of the French Pierre Bourdieu, approaching the theme involves examining the influence of the materialized sociocultural factor, in addition to other important analytical concepts, through the typification of different types of capital5 (Bourdieu, 1998).

However, even with the emphasis on external factors, these analytical perspectives distance themselves from the famous Theory of Cultural Need6 for not defending social groups culturally deficient in themselves, but disadvantaged in relation to what the school values. Essential aspect, as it moves away from the processes of blaming individuals themselves for poor school performance.

In addition to these contributions and covering other analytical strategies, not necessarily focused on the educational field, we have the production of authors such as Moser (1998), Kaztman (1999), Brooks-Gunn, Duncan and Aber (1997), Ellen and Turner (1997) and Small and Newman (2001), who started to look at the territorial issue as important for the investigation of social issues and at the relational category “social vulnerability” as an interesting analytical key. Among other pertinent approaches, we have seen studies on the neighborhood effect and the structure of opportunities emerge as promising for the field of education.

Specifically in relation to the educational apparatus, the social environment of the schools - territory, relations and forms of accessibility to the material, cultural and organizational goods of the families in the neighborhoods - came to be assumed in the examination of the phenomenon. An approach that allows us to understand how specificities of the inhabited territory can manifest themselves and influence the work of schools, the population served by them and the relationship they build with each other.

A relatively recent topic in Brazil, the investigation of the relationship between socio- -spatial conditions and aspects of schooling in different segments of the population has been proposed by researchers in the field (Torres et al., 2005; Cunha & Jiménez, 2006; Ribeiro & Kaztman, 2008; Ribeiro et al., 2010; Stoco & Almeida, 2011; Koslinski & Alves, 2012; Almeida, 2017). Therefore, the debate stresses the need to understand the external influences on schoolwork. An approach that assumes the territorial context both as a physical space (structure and available services) and as a space for relationships between subjects (belonging or not to the school community).

Social vulnerability and assets, vulnerability, and opportunity structures

Social vulnerability is a term that came to be used by the World Bank, with greater repercussion from the text by Caroline Moser (1998). With it, the notion of poverty was expanded, giving it a more dynamic character, not only linked to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the 1970s, or the Unsatisfied Basic Needs (UBN) of the 1980s. It is assumed the need to look at how individuals behave in certain situations.

. . . being in a situation of social vulnerability is broader than being in a situation of poverty, as it refers to the condition of not having or being unable to use material and immaterial assets that would allow the individual or social group to deal with the situation of poverty. Thus, vulnerable places are those in which individuals or social groups face risks and the impossibility of accessing services and basic citizenship rights, such as housing, sanitary, educational, working and participation conditions and differential access to information and to opportunities offered more widely to those who have these conditions.7 (Stoco & Almeida, 2011, p. 665, own translation).

According to Souza (2018, p. 3), his proposition is linked to the process of aggravation of urban poverty observed between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, linked to the “context of economic restructuring resulting from globalization and its social and space impacts”. Social vulnerability, according to the author, is a category developed based on the neoliberal perspective of social disadvantages and the “neo-Marxist perspective of the restriction of rights” (Souza, 2018, p. 3).

Although the definition of the concept is not unambiguous, from Kaztman (1999b, 2000) and Kaztman et al. (1999), the perspective of social vulnerability provides the possibility of understanding how being in certain conditions enables or prevents people from taking advantage of the available opportunities. These opportunities, understood as a structure of goods, services and activities, are unequally available in the city and also unequally accessible to individuals from the same location: “By vulnerability, we understand the ability of a person or a place to take advantage of the opportunities available in different socioeconomic spheres to improve their welfare situation or prevent their deterioration”8 (Kaztman, 2000, p. 281, own translation).

Opportunity structures are defined as probabilities of access to goods, services or the performance of activities. These opportunities influence the well-being of places, either because they allow or facilitate members of the place to use their own resources or because it provides them with new resources.9 (Kaztman, 1999, p. 21, own translation).

As Cunha (2006) clarifies well, the responsiveness of individuals as a result of various factors is an essential aspect of the concept of social vulnerability. It encompasses both the conditions to which individuals are exposed and their ability to respond to different situations.

One of the consensuses about the concept of social vulnerability is that it has a multifaceted character, covering several dimensions, from which it is possible to identify situations of vulnerability of individuals, families or communities. Such dimensions relate to elements linked both to the own characteristics of individuals or families, such as their assets and sociodemographic characteristics, as well as those related to the social environment in which they are inserted. What can be seen is that, for scholars who deal with the topic, there is an essential character of vulnerability, that is, it refers to an attribute related to the ability to respond to situations of risk or constraints.10 (Cunha, 2006, p. 145, own translation).

Considering the notion of assets, vulnerability and opportunity structures (Avos), we started to look at the inhabited space, uniting the structure of available opportunities with the capacity of individuals to respond. The main sources of opportunity come from the functioning of the State, the market, the community and civil society. Assets, on the other hand, comprise the set of resources that can be mobilized in pursuit of improving the well-being of the household, which leads to the finding that not every resource necessarily works as an asset, since, for this, it needs to be mobilized by the individual as such. The identification of assets is vast and refers to various forms, both material, in the case of property (financial capital), and immaterial, in the case of schooling (cultural capital) or friendship (social capital).

Strictly, assets can be almost infinite if we think of abstract possibilities. From the most obvious ones, such as property, savings, credit, to the less obvious ones, such as friendships, belonging to mutual aid organizations and elements that can be perceived and used, such as time and the capacity for geographic mobility, etc.11 (Kaztman et al., 1999, own translation).

A powerful analytical key, the assets perspective is a tool to understand what can help families (or individuals) to improve their living conditions and to access available opportunities. Kaztman and Filgueira (2006, p. 85, own translation), highlight that an important consequence of this approach is that “the microsocial analysis of the resources of households, people and their mobilization strategies cannot be done independently of the macrosocial analysis of the transformations of the opportunity structures”.12

It is important to highlight that the same “asset” can function as a “liability”, depending on the reality experienced by individuals. In the perspective of Flores (2008), liabilities would be those that would harm individuals to use certain resources in order to improve their living conditions and to access available opportunities. For example, the influence of peers can be positive for accessing school in one neighborhood (active), and negative in another, if, due to the characteristics of the population, school attendance is not a valued activity (passive).

Synthetically, the opportunity structures would be, then, the resources available to the population in a given territory/neighborhood; the asset, everything that can be used to access the opportunities at a given time and improve the well-being of the individual or group; its counterpoint, the passive, understood as the material and immaterial barriers to the use of available opportunities; and vulnerability, the entire configuration formed from them.

Thus, talking about vulnerable places means talking about places where one faces risks and/or impediments to take advantage of the available opportunity structures, giving the dimension of the relationship between individual agency and social structure. In the words of Bilac (2006, p. 54, own translation):

. . . social actors do not act in a vacuum, in which they depend only on their asset management capacity, but in a historical and social context made up of opportunities and constraints, since opportunity structures depend on macro-social factors.13

Returning to the literature on the subject, Souza (2018, p. 13) highlights that, as social capital is seen as an important asset in vulnerability, the neighborhood is analyzed with greater care. The importance of the structure and composition of the neighborhood is highlighted as relevant aspects for understanding the reproduction of inequalities, poverty and exclusion.

As Ribeiro et al. (2016, p. 189, own translation) point out, after mapping the work developed by the Metropolis Observatory, “the efficiency and equity of the school’s functioning depend, among other factors, on the quality and isonomy of the environment provided by the metropolis’ social space”.14 The residential segregation is taken as an important aspect for analysis.

In this context, the so-called neighborhood effect emerges as a dear aspect of educational analysis. Associated with the territorial distribution of the subjects, with the relationship with each other and with the inhabited space, this perspective allows us to better understand how aspects of the neighborhood affect the schooling processes of children and young people.

Neighborhood effect

Coming from research that observed how segregation in neighborhoods is related to some social phenomena, such as experience in the labor market, involvement with crime and school attendance, the neighborhood effect would be the understanding of how the effect of the socio-spatial context in which a certain group lives influences this group. In the words of Alves et al. (2008, p. 91, own translation):

. . . it fits the general category of explanatory models based on the hypothesis of a causal relationship between certain events and the social context in which they occur. . . . In other words, it is about capturing the effect of social relations developed within the place of residence on outcomes that occurred in the neighborhood.15

A review by Koslinski and Alves (2012) shows that we can think of at least three groups of studies on the neighborhood effect: the first is the epidemic models; the second, the models of collective socialization; and the third, the institutional models. In the first group, there would be the observation that children would tend to socialize and adopt behaviors that mirror those adopted by peers in a given neighborhood. In the second there would be the studies that realize that children who live in more segregated neighborhoods end up without positively different models. And, in the third, studies that analyze the influence of adults who work in neighborhood institutions on children and adolescents.

Other important models in the analysis of the neighborhood effect would be “the instrumental models”. In these models, according to Small and Newman (2001), the opportunity structures present in the neighborhood is also a factor that facilitates or inhibits individual decisions, an aspect that varies from neighborhood to neighborhood. Taking an educational example, Koslinski and Alves (2012, p. 814, own translation) point out that, “in the specific area of education, we can think that the opportunities and choices of individuals are affected by the quantity and quality of schools offered in their neighborhoods”.16

Although the neighborhood, the district is not decisive in the analysis of the outcomes experienced by people, not being possible to build a “cause-effect” line that explains different social phenomena based on certain characteristics of the neighborhood, the district, it allows the understanding of several aspects that, together and interacting with others of the individual experience, influence with greater or lesser impact on the subjects’ choices and possibilities. Particularly promising to highlight the social context in which the schooling process is circumscribed, empirical research, such as the one presented in Ribeiro and Kaztman (2008), shows the existence of important relationships between the neighborhood and the school universe.

Assuming the warning made by Small and Newman (2001) about the explanatory limitation of the neighborhood effect in relation to the social outcomes experienced by individuals, we assume external factors as important to compose, along with others, the understanding of reality. From a broader analysis, we will be able to understand the social conditions for learning that, according to Bernal (2009, p. 171, own translation), “are related to the initial resources and the social, cultural and economic context of students and their families”, which “allow us to analyze in a more complex way the problems of access, permanence and results of students, as well as to understand more precisely the origin of inequalities in education, not exclusively of an educational nature”.17

Activities experienced outside of school: the social environment as a source of assets and liabilities

Thinking about the conditions that students from different places have to develop their schooling trajectories is essential as it puts into critical analysis the idea of the school as a guarantor of equal opportunities for all children who enter it (equity). This is because, as Bernal well points out (2009, p. 173, own translation),

. . . the social conditions for learning are variable and different in each country, community and family. They work as concentric circles of the mentioned spheres of relationships and generate

both outside and inside assets or liabilities that enable or hinder the educational processes of boys, girls and adolescents.18

The experiences and activities experienced by children in the social environment in which they live will have greater or lesser impact on their performance at school depending on their configuration, as not everyone will have access to or enjoy the same opportunity structures available. Bernal (2009) highlights that both family and neighborhood, with material or symbolic means, can function as active or passive and influence the students’ learning process.

Our empirical data help us to think about this issue as they reveal the perception of the existence of a certain differentiation in the material and organizational contributions of families and neighborhoods in relation to children. The relationship established between the models, structures and dynamics of the social environment with the students’ academic performance became clear. The social environment can guarantee or not the provision of resources, strategies and instruments that collaborate with the schooling processes, transmitting patterns that will be more or less effective, depending on their adequacy to the model valued by the institution.

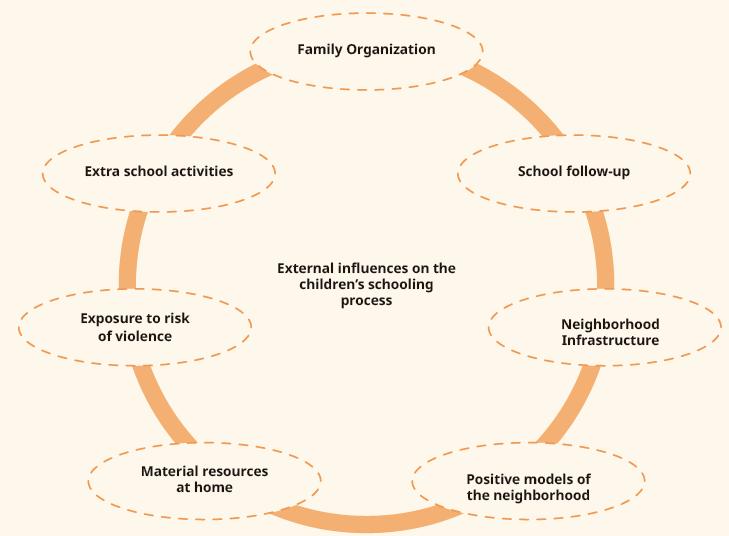

In our analysis, the association of the family aspects, the neighborhood and its organization as related to events experienced at school is remarkable. Different subjects associate behavior and school performance with certain conditions experienced by the child in the social environment. As highlighted in Figure 1, several aspects can be influential.

In relation to the family, as highlighted in the following excerpts, we observe that professionals see it as an important factor in understanding the development of students. Whether influencing behavior or influencing school performance itself, they are repeatedly mentioned. The appreciation given to cultural capital as an important asset in the school performance of children calls our attention, especially taken, in the Bourdieusian perspective, in the incorporated state.19

From the perspective of management, I have observed that some family issues are not resolved within the family sphere, and the student ends up bringing these anxieties to school and not participating, speaking, exposing, or exposing themselves too much, more aggressively, verbally or physically, and so when you go to get what it is, the trigger for this is not within the school, sometimes it arrived at school already pushing, hitting, throwing stones, kicking... (Interview, School 1 - Manager 3, own translation).

In fact, when the family participates together, when we call, and the family comes, we somehow manage to follow up and accompany the child, whatever the case. The difficulties we have in following up students are those that we call, and the family doesn’t come, doesn’t commit, doesn’t follow up. (Interview, School 2 - Manager 1, own translation).

All [students] who are in my Group 1,20I don’t know if the parents are in better financial condition, but you can see that they are always reading, they know news, go out on the weekend, talk about movies... [In Group 4 would it be the opposite?] We see that the students in Group 4 seem to be people who don’t know things, their parents are very lay people, everything is new for them. I have a student who asked me to show him the Shrek movie, it’s on three, but he didn’t even watch the first one. (Interview, School 3 - Teacher 7, own translation).

It is not always the issue of affectivity, but of knowledge itself, of getting out of ignorance (ignorance that I am talking about not only in the pejorative way, but of knowledge itself). A father who has a little more knowledge, who has a minimum contact with knowledge, I think he can help more, support his children more. (Interview, School 4 - Teacher 1, own translation).

Often, the relationship made between children’s performance and the form of family organization is linear. Similar to what Paixão (2006, p. 65) realized, in these cases, the perspective assumed is that of family arrangements, and it is possible to “hear justifications that appeal to arguments such as the family being unstructured, when the subject refers to school difficulties faced by students”.21

[When asked for an example of external influence on student performance] There is a family, the mother does not work, she is alone, she has a large number of children and she lives on a school/family grant, this kind of help - milk donation, she has an older son who is arrested, she has a very complicated history, and ends up reflecting on her children. The mother does not have a (family) structure. . . . (Interview, E3 - Teacher 5, own translation).

The most frequently mentioned aspect was school monitoring. There is, in all schools, the understanding that the more the family monitors their children’s school activities, the better their performance will be at school.

It is important to note that, when they consider school monitoring by families as something essential, schools demand from them a certain posture and organization. However, the expected model is not always natural to the families served.

So, one of the tips we give at the meeting is to look at the children’s notebooks, and when they say they come home tired, I say he had the baby, and that’s why it’s his responsibility. The school has a responsibility here, but a part of this school life is also done outside the school space, it is done at home, it is done in other spaces, but it contributes to life here, with school activities. (Interview, E1 - Manager 2).

I think the characteristic that can influence is when the father is concerned about accompanying the child at school. This is the fundamental characteristic you have to have, so it doesn’t matter if you are a mother who is a housekeeper and works all day, because at night she will ask and comment, she will talk to her son, see what he has done, read a story together... (Interview, E2 - Manager 3, own translation).

The father could be there picking up the child’s notebook, seeing if she is doing the activities, accompanying this child. There is a whole sociocultural process, but there is also the presence of the family. Regardless of all this, the family pays attention, if she lives with the grandmother, she will sit with the child, see if she has done it when she has a homework. (Interview, E3 - Manager 1, own translation).

Parents must accompany the children in their school development, just as they already follow in the organic one, to see how the child is doing, because this would make the teacher’s job easier. Not only are we talking about the parents’ meeting as the child has developed, the interesting thing is for the parents to follow along, otherwise the problems will become chronic until they arrive at the meeting. They must follow along, read the messages in the child’s diary, see the class notebook, ask the child what he has learned, follow up on his homework... This will all make the child see that the parents are interested, and thus appreciate the education. (Interview, E4 - Teacher 4, own translation).

In the analysis of “homework”, Resende (2008, p. 395) observes that families from different social backgrounds commit themselves differently to their children’s schooling. The material and symbolic resources available are unequal, and popular families are not always able to cope with the demands of the school. The author found that, based on the diversity of strategies that families use to monitor their homework, it is possible to observe differences and similarities between their socialization models and those of the school.

During the interviews, it was common for teachers to mention the guidance they give to families regarding the expected follow-up. From a given model, they make clear the contours of their expectations.

I’m going to talk about an experience that I do a lot. I do a job with the parents so that the parents know where we are, what I intend to work and where I want to get. So, practically at the parents’ meeting, I “teach the father to teach the child”, how they are going to do it, look at the margin, how it is a process of subtraction, how it is a process of multiplication. So it’s a class that they will develop with their children, and this has helped me a lot, a lot, I have very few learning problems. (Interview, E1 - Teacher 6, own translation)

[Best way for the community to participate in the school and help children’s learning] Being together with the teachers, being present because we guide parents even on how they can help. . . . (Interview, E4 - Teacher 5, own translation)

Even though it is not the most frequent, it is worth pointing out that, in addition to the monitoring exercised by family members, there is mention of the help given to children by people outside the family nucleus. Aspect in which the socioeconomic differential and the structure of available opportunities is latent, since, in the school that serves the population with less social vulnerability (E1), this monitoring would take place through the hiring of specialized services (psychopedagogue, speech therapist and course “Kumon”), while the school with greater social vulnerability (E4) mentions non-formal care institutions and neighbors.

In addition to the influence of the family, other aspects emerge in the interviews as inducers of the children’s chances of adopting certain behaviors, especially aimed at school experience. It is interesting to point out that the neighborhood is seen as a locus of opportunity and conviviality, which can be a generator of options that will be directly associated with choices or attitudes regarding issues related to the education of children and their performance, in particular the dedication to school activities, cultural baggage and perspective for the future, both because of the infrastructure conditions it has and the influence of peers (other children and adults in the neighborhood).

Among school professionals, there is a certain general understanding that neighborhoods with better infrastructure, in terms of public service and leisure, and with a greater number of people with a certain cultural pattern, are more positive for school trajectories. Living with certain values, especially the appreciation of the school, and more ambitious life perspectives are aspects seen as positive. On the other hand, neighborhoods with the worst infrastructure and the greatest concentration of people with low cultural capital, as well as the greater role of drug traffickers and criminals, are viewed negatively, including due to the greater risk of recruiting minors.

It is important to highlight the ways in which respondents from each school compose their analysis. Using the negative referent, the E1 school compares itself to other realities. School E2 admits this reality, but with the exception of the specific neighborhood of the school, which would be in a better condition than other neighborhoods served by the school. In schools E3 and E4, the analysis is made by taking the neighborhood itself as a reference, as they are understood as less favored in terms of culture, urban infrastructure and in relation to exposure to crime.

I’m saying this because I’ve already taught in much more distant, more peripheral neighborhoods, and the relationship with culture and health, you notice that it is more impaired, more truncated, and here this relationship occurs more easily, . . . (Interview, E1 - Manager 2, own translation).

I think that the neighborhood here is developed, it is economically well located, and the problems with some children are not always related to children here, there are children from another place. . . . (Interview, E1 - Employee 1, own translation).

There are few children, apart from the neighborhood here from school, who arrive from school and will have time to study at home. I often say at parent’s meetings that this is important. This is a very bad characteristic, as it passes, as everyone plays in the street, it becomes a culture. “I get home from school, throw my backpack and go out into the street”, and this does not favor learning, because there is also the problem of drug trafficking groups, and then they are together with these groups, they are interacting. (Interview, E2 - Manager 2, own translation).

There are three neighborhoods here, and you can see the difference between the students who live at the bottom of the neighborhood and those who live here in the school’s neighborhood, and even in the other one. They are completely different communities, you can see that they are more needy, have more difficulties, the family is a little more distant, the others are closer, and the purchasing power is greater. Of course, it depends on the family too, it may be that living in another neighborhood is not so different, but you see that the neighborhood is more needy. (Interview, E2 - Employee 5, own translation).

I think it’s the environment, friendships... So, if the neighborhood were more well cared, if there was the opportunity to live with projects, lectures, courses, I think it would be possible to change... I’m afraid, because, as I don’t know the people, and we know that there are problems with trafficking, drugs and theft, we are afraid to interfere in space, because it can be dangerous. (Interview, E3 - Teacher 5, own translation).

As explained in the following excerpts, a strategy evidenced by some families to face the situation of danger, violence and the influence of negative elements in the neighborhood on their children is to prevent them from playing in the street, except under the supervision of an adult.

I don’t play in the street. Only when someone is looking. When my grandmother is in the square and looks at me, I play. (Interview, E1 - Student 4, own translation).

My son doesn’t have a day that comes or comes home from school alone, because in the past (I was 6 or 7 years old) we used to go to school alone, today we don’t let that happen. (Interview, E1 - Family 8, own translation).

[Do you play in the street?] Yes, sometimes, when my mother is on the street, but I only play with my cousin on the sidewalk, by bicycle. (Interview, E2 - Student 9, own translation).

[Do you play in the street?] No, only when my mother is too, then I can go to my friend’s house. (Interview, E3 - Student 9, own translation).

[Is something happening in the neighborhood that hinders your child’s learning?] There are a lot of things that interfere, you can’t let them stay on the street because there are many kids with bad habits, that sometimes the mother works, she’s not at home and doesn’t see what the son does. [But what could happen?] Influence: marijuana, drugs, these things... In the daytime we see these things; so, as long as we can hold them at home, we do it. (Interview, E3 - Family 6, own translation).

[Do you play in the street?] My mom won’t let me. [Why?] Because there are a lot of bad guys here. (Interview, E4 - Student 4, own translation).

It is possible to affirm that schools differ in relation to material and immaterial assets made possible by families to children. The mention both of the existence of computers and books at home and of a more direct monitoring and with pedagogical specificities in schools E1 and E2 is consistently higher than in schools E3 and E4. In the latter, there are family members who declare that they see absolutely nothing in their home that could contribute to their children’s school learning, specifically citing the absence of material goods such as books and computers as a justification.

I’ve always preserved information a lot, so I monitor internet access, monitor video game time with the technology that we have. All the technologies that we have available within a middle-class standard or a little more, I have availability. My wife and I really value the concept of family; so, when we’re together, we’re really together. Saturday and Sunday we stay (me, wife and two kids) so we have these activities. We have the habit of reading, which unfortunately not everyone has, even using the dictionary he has a habit. (Interview, E1 - Family 2, own translation).

[Does anything at home help your child’s learning at school?] Yes, we are concerned about having his space, a desk, a chair, a right place for him to study, a right time to study, so that he can start to discipline himself for studies. We try to work on the routine idea so that he starts to incorporate the habit of studying. (Interview, E2 - Family 2, own translation).

Internet access and computer use at early ages. Access to reading, take to the bookstore to choose the book. Encourage reasoning, pay attention when they are calling to show something, tell a story, listen to what they have to say... All of this helps, whatever you are doing with them helps, encourages them, and that makes them develop further. (Interview, E2 - Family 8, own translation).

It’s no use getting home from school, and it’s over, just talk and play. Nagging helps, because he knows that if he doesn’t do it, it will be worse for him, and he will. [Do you have a book or a computer?] No, no. It’s difficult, and it’s expensive, I can’t afford to buy it now. (Interview, E3 - Family 1).

I try to help a lot, the little I know, because I haven’t finished my studies either, so I help with what I know. . . . (Interview, E4 - Family 1, own translation).

I don’t have a computer; I don’t have anything. (Interview, E4 - Family 5, own translation).

The references to educational games and the perception of certain forms of help as the most appropriate present in the statements of family members from schools E1 and E2 show the appropriation of specifically pedagogical activities as action. This places them closer to the knowledge valued by the school, configuring them as a possible strategy of distinction (Bourdieu, 1974), in which activities valued by schools and understood as such by certain families, when made possible for children, place them at a different level of the others to the school. A strategy that is not necessarily consciously orchestrated as a form of distinction, but perceived as important for the child’s development, and therefore closer to the school’s socialization model.

During the interviews with students and families, we asked about activities experienced outside of school (what children do when they are not at school, what activities they practice and which places they go to), the answers show that taking advantage of the neighborhood’s and city’s opportunity structure, as well as the nature of the activities mentioned by family members from different schools, is quite uneven. In schools E1 and E2, it was common for subjects to mention activities such as going to the mall, cinema, ranches, parks and woods, as well as paid courses in soccer, swimming, kung fu, piano, English and Kumon. In schools E3 and E4, the vast majority declared that the only activities outside of school were going to the homes of friends and relatives, playing in the street and attending church activities or non-formal institutions, though.

Taking away school? I do kung fu. [How many times do you go?] I think Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and I’m trying to go tomorrow. I go to catechism too. (Interview, E1 - Student 5, own translation).

We go to so many places... Ranches, farms, swimming pools, we travel a lot, we go to the beach... Theatre, cinema... I am married to a teacher; so, the cultural side, we preserve a lot and are very active. (Interview, E1 - Family 2, own translation).

We take them to the movies, the playground, the zoo. (Interview, E1 - Family 6).

To the mall, to the zoo, I go a lot with my family... My relatives’ house. . . . (Interview, E2 - Student 4, own translation).

Swimming class, English class... (Interview, E2 - Family 2, own translation).

We are Jehovah’s Witnesses, so we go to the kingdom hall and take them to places to have fun, such as restaurants, shopping malls, or parks. (Interview, E2 - Family 6, own translation).

No, course, no, I take classes. [From what?] Guitar, singing, keyboard. [When?] Saturday, every Saturday. [And where are the classes?] At church (Assembly of God), I go with my mother and sister. (Interview, E3 - Student 5, own translation).

From time to time, I go out to play at a friend’s house, from time to time I play in the street that there are a lot of friends of mine there. (Interview, E3 - Student 7, own translation).

When he’s not at school, he has swimming classes in this same place, in this NGO. He has computer classes. He goes three times a week. I take him. (Interview, E3 - Family 10, own translation).

I go to the field to play ball, go out to the street to play, fly a kite. [Do you stay at home with an adult?] When my mom doesn’t go to work, I stay with her there. [And when does she work?] She always goes. [So, are you all alone every day?] No, on weekends, I’m not. [What about your siblings?] The youngest one goes to the entity, and the second oldest one comes to the school, and when I leave, she goes too. (Interview, E4 - Student 8, own translation).

He goes to my brother’s house, he goes to the house of friends who also goes to my house and, on the street, just in front of my house and with the gate open. (Interview, E4 - Family 4, own translation).

They go to the entity, there they have lunch, have snacks, do activities... It’s very good there, they go there every day. (Interview, E4 - Family 10, own translation).

This differentiation in taking advantage of the opportunity structure of the neighborhood and the city is an important factor for analysis. Penna and Ferreira (2014, p. 27) note that there is a need to think about public policies assuming the “contradictory, unequal and conflicting socialization and appropriation of the city and the right to the city”. The authors defend that the reproduction of the urban space and the social relations of appropriation of the city by the different classes must be assumed as problems in the management of urban policy and planning.

Figueiredo et al. (2017), taking slums in Rio de Janeiro as locus, relate vulnerability to a situation of violence in different dimensions. The authors’ analysis helps us to understand that this lack of resources and spaces for cultural and symbolic development, observed in our data, can be understood as a type of violence present in vulnerable territories.

Another issue that is important to discuss is the relationship between vulnerability/exclusion and violence. . . . Violence was observed not only in what we call extreme/lethal vulnerability, but also in the fact of depriving goods and services (socioeconomic vulnerability), limiting political agency (juridical-legal vulnerability) and denying resources and spaces for cultural development and symbolic affirmation (ideological-cultural vulnerability).22 (Figueiredo et al., 2017, p. 814, own translation).

More specifically with regard to the educational process, Thin (2006, p. 28) observes that the consumption of extracurricular activities of a cultural or sporting nature, organized and directed by specialists, ends up influencing positively in the acquisition of behaviors valued by schools. The differentiation observed between schools reveals that the expansion of the sociocultural repertoire made possible by certain families or available in certain neighborhoods certainly favors the school process. This is because educational activity values certain sets of knowledge over others (Bourdieu, 1998).

The opportunity structures available and accessible to families from different schools is uneven. In the same way, both the family and the neighborhood influence are seen as potentiating (active) or inhibiting (passive) of taking advantage of opportunities and, in particular, of a more positive school performance. The difference between schools leads us to consider that coexistence in different spaces generates a form of involvement and “use” of the differentiated educational opportunity. However, as “nothing should seem impossible to change” (Brecht, 1982, p. 45), it is up to the school to know this reality and its limits of action to act in it and for social rights to engage: demystifying old actions and organizing new ones from of the reality of the population served.

Final considerations

Our empirical data reveal that there are several factors outside the school understood as influencing the educational trajectory of students, especially with regard to their performance. The weight of social relationships and the objective conditions of families to build students’ school itineraries is evident. The contrast between the two groups of schools surveyed reveals that both the present social models and the geography of opportunities available in different territories are strong influencers on the students’ schooling processes.

Respondents indicate from the family organization and the school monitoring provided by it (daily care and guidance and, mainly, help with school tasks) to the neighborhood infrastructure (public services and availability of leisure) as important aspects. Going through socialization models in the neighborhood (peer socialization), material resources available at home (books and computer), exposure to the risk of violence (especially drug trafficking) and the possibility of experiencing extracurricular activities (tours, courses, games), the interviewees allow us to identify important elements that act as assets or liabilities in the students’ schooling process.

It was evident, from the analyzed data, that the material and symbolic resources available among the families of the different schools are unequal and that the poorest ones are not always able to face the demands placed by the desired model in the institution. An aspect in which the socioeconomic and cultural differential, as well as the opportunity structures available in the social environment, proved to be remarkable, as observed in the two extremes of our sample: in the school that serves the population with less social vulnerability (E1), the offer of goods and services and the nature of monitoring families in relation to the process of schooling their children is more favorable and closer to the school model, on the other hand, in the school with greater social vulnerability (E4), in addition to the lack of a geography of favorable opportunities, school monitoring by families, due to their sociocultural and material characteristics, does not come close to the requirements and expectations of the institution.

Important examples were evidenced by the ownership of material goods and reference to educational games and qualified help in following up on tasks, in which schools with a more favored socio-spatial location stand out as those with families with better resources and that offer specifically educational activities as an action, approaching them to the model and knowledge valued by the school, while, in schools with less favored socio-spatial location, families have little material offer to help their children, and the activities provided outside the school are restricted to social interaction with family members and care activities, religious and non-governmental institutions. An aspect that can be analyzed in the typology proposed by Figueiredo et al. (2017), as one of the various forms of violence experienced by subjects in the most impoverished territories of cities, which they specifically mention as ideological-cultural vulnerability.

It is worth noting, however, that although the high-performing school E3, in general terms, does not deviate from its peer in our sample design, the low-performing school E4, it presents the choice of the school by the families as a remarkable aspect. Even approaching school E4 in the interviewees’ perception of extra-school factors, the fact that it is chosen by families over other schools in the region, a reality not observed for school E4, can be an important element of analysis to understand this reality. Unfortunately, this dimension cannot be deepened with the data from the present research, but it suggests a new investigative delimitation that is quite pertinent for a closer understanding of the issue, within the field of concerns with the process of school segregation.

In general, and turning specifically to the problem analyzed in this article, our data show that the experience in different spaces is pointed out by the interviewees as enhancing, or not, a greater “use” of the educational opportunity. And, in this sense, as Mészáros (2008, p. 25) points out, a significant reformulation of education requires the corresponding transformation of the social framework in which “society’s educational practices must fulfill the vital and historically important functions of change”.

Arroyo (2010) highlights that it is essential to resume the local and political debate on the relationship between education and inequality in the debate on school reality, especially because inequalities in the abstract do not have a face, color, gender or class, and, therefore, omit the historical and concrete subjects who experience them. “A relationship that is more complex with the increased access to school for sons and daughters of collectives made and maintained so unequal in our history”23 (Arroyo, 2010, p. 1384, own translation), a fact that corroborates the need for the school to know and recognize the population served and their social environment in order to organize their work and struggles.

In this sense, examining what Brecht well puts in his poem as that which comes “covered as usual” (1982, p. 45), can produce a necessary awareness of reality in the process of working on and for its improvement, in a perspective of change. As Freire (1979, p. 21, own translation) well points out, “as far as the commitment cannot be a passive act, but praxis - action and reflection on reality -, insertion in it, it undoubtedly implies a knowledge of reality”,24 and , thus, even not being able to act independently of social constraints, the school and its professionals are able to build a collective work that can make a difference in the lives of those who participate in it and, more specifically, in the schooling trajectories of its students, without losing sight of the broader struggles necessary for the structural improvement of the processes in which it operates and on which it depends as an organization.

Understand that the school cannot do everything regarding the living conditions of its students, at the same time that it should not accept, as Brecht invites us, “what is usually natural” (1982, p. 45), using this as a justification for immobility is a great challenge. Entering this contradiction places us in the situation of a double task: to fight for the improvement of conditions for the development of the school’s work (including the internal and external conditions of the educational establishment for the children schooling) and to fight for these institutions to assume with responsibility the role that we envision for them, not as mere reproducers of inequalities, but as agents in the construction of a fairer society.

We have no doubts about the importance and need for educational institutions to improve their actions by developing educational projects and processes that face the adverse social and economic conditions of the population they serve. As Brecht (1982, p. 45) invites us, we must not resign ourselves to the evils of society, nothing is impossible to change. As a social institution, as Freire has been inviting us for some time (1979), the school must act in favor of change, a temporary change, as it is subordinate to the social order, but not less important, since it is determinant in the student trajectories of its pupils.

REFERENCES

Almeida, L. C. (2014). Relação entre o desempenho e o entorno social em escolas municipais de Campinas: A voz dos sujeitos [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. [ Links ]

Almeida, L. C. (2017). As desigualdades e o trabalho das escolas: Problematizando a relação entre desempenho e localização socioespacial. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 22, 361-384. [ Links ]

Alves, F., Franco Jr., C., & Ribeiro, L. C. de Q. (2008). Segregação residencial e desigualdade escolar no Rio de Janeiro. In L. C. de Q. Ribeiro, & R. Kaztman (Orgs.), A cidade contra a escola? Segregação urbana e desigualdades educacionais em grandes cidades da América Latina (pp. 91-118). Letra Capital. [ Links ]

Arroyo, M. G. (2010). Políticas educacionais e desigualdades: À procura de novos significados. Educação & Sociedade, 31(113), 1381-1416. [ Links ]

Bernal, E. C. (2009). Las condiciones sociales para el aprendizaje en la relación equidad social y educación. In N. López. (Org.), De relaciones, actores y territorios: Hacia nuevas políticas para la educación en América Latina (pp. 171-201). IIPE-Unesco. [ Links ]

Bilac, E. D. (2006). Gênero, vulnerabilidade das famílias e capital social: Algumas reflexões. In J. M. P. da Cunha (Org.), Novas metrópoles paulistas: População, vulnerabilidade e segregação (pp. 51-65). Nepo/Unicamp. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1974). A economia das trocas simbólicas. Perspectiva. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1998). Escritos de educação. Vozes. [ Links ]

Brecht, B. (1982). Nada é impossível de mudar. Antologia poética. ELO Editora. [ Links ]

Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G. J., & Aber, J. L. (Orgs.). (1997). Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for children (Vol. 1). Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., & York, R. L. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington: Office of Education and Welfare. [ Links ]

Corbetta, S. (2009). Territorio y educación: La escuela desde un enfoque de territorio en políticas públicas. In N. López (Org.), De relaciones, actores y territorios: Hacia nuevas políticas para la educación en América Latina (pp. 263-303). IIPE-Unesco. [ Links ]

Cunha, J. M. P. da (Org.). (2006). Novas metrópoles paulistas: População, vulnerabilidade e segregação. Nepo/Unicamp. [ Links ]

Cunha, J. M. P. da, & Jiménez, M. A. (2006). Segregação e acúmulo de carências: Localização de pobreza e condições educacionais na Região Metropolitana de Campinas. In J. M. P. da Cunha (Org.), Novas metrópoles paulistas: População, vulnerabilidade e segregação (pp. 365-398). Nepo/Unicamp. [ Links ]

Ellen, I. G., & Turner, M. A. (1997). Does neighborhood matter? Assessing recent evidence. Housing Policy Debate, 8(4), 833-866. [ Links ]

Érnica, M., & Batista, A. A. G. (2012). A escola, a metrópole e a vizinhança vulnerável. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 42(146), 640-666. [ Links ]

Figueiredo, G. de O., Weihmüller, V. C., Vermelho, S. C., & Araya, J. B. (2017). Discusión y construcción de la categoría teórica de vulnerabilidad social. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 47(165), 796-818. [ Links ]

Flores, C. (2008). Segregação residencial e resultados educacionais na cidade de Santiago do Chile. In L. C. de Q. Ribeiro, & R. Kaztman, R. (Orgs.), A cidade contra a escola? Segregação urbana e desigualdades educacionais em grandes cidades da América Latina (pp. 145-179). Letra Capital. [ Links ]

Franco, C., Brooke, N., Alves, F. (2008). Estudo longitudinal sobre qualidade e equidade no ensino fundamental brasileiro: Geres 2005. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 16(61), 625-638. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (1979). Educação e mudança. Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Kaztman, R. (Org.). (1999). Activos y estructuras de oportunidades: Estudios sobre las raíces de la vulnerabilidad social en Uruguay. Pnud/Cepal. [ Links ]

Kaztman, R. (2000). Notas sobre la medición de la vulnerabilidad social. Borrador para discusión. 5 Taller regional, la medición de la pobreza, métodos e aplicaciones. México: BID-BIRF-CEPAL. http://www.eclac.cl/deype/mecovi/docs/TALLeR5/24.pdf [ Links ]

Kaztman, R., Beccaria, L., Filgueira, F., Golbert, L., & Kessler, G. (1999). Vulnerabilidad, activos y exclusión social en Argentina y Uruguay. Proyecto Fundación Ford. [ Links ]

Kaztman, R., & Filgueira, F. (2006). As normas como bem público e privado: reflexões nas fronteiras do enfoque “ativos, vulnerabilidade e estrutura de oportunidades” (Aveo). In J. M. P. da Cunha (Org.), Novas metrópoles paulistas: População, vulnerabilidade e segregação (pp. 68-94). Nepo/Unicamp. [ Links ]

Koslinski, M. C., & Alves, F. (2012). Novos olhares para as desigualdades de oportunidades educacionais: a segregação residencial e a relação favela-asfalto no contexto carioca. Educação & Sociedade, 33(120), 783-803. [ Links ]

Mészáros, I. (2008). A educação para além do capital. Boitempo. [ Links ]

Moser, C. O. N. (1998). The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Development, 26(1), 1-19. [ Links ]

Paixão, L. P. (2006). Compreendendo a escola na perspectiva das famílias. In M. L. R. Müller, & L. P. Paixão (Org.), Educação, diferenças e desigualdades (pp. 57-81). EdUFMT. [ Links ]

Patto, M. H. de S. (1990). A produção do fracasso escolar. T.A. Queiroz. [ Links ]

Penna, N. A., & Ferreira, I. B. (2014). Desigualdades socioespaciais e áreas de vulnerabilidades nas cidades. Mercator, 13(3), 25-36. [ Links ]

Resende, T. de F. (2008). Entre escolas e famílias: Revelações dos deveres de casa. Paidéia, 18(40), 385-398. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, L. C. de Q., & Kaztman, R. (Orgs.). (2008). A cidade contra a escola? Segregação urbana e desigualdades educacionais em grandes cidades da América Latina. Letra Capital. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, L. C. de Q., Koslinski, M. C., Alves, F., & Lasmar, C. (Orgs.). (2010). Desigualdades urbanas, desigualdades escolares. Letra Capital. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, L. C. de Q., Koslinski, M. C., Zuccarelli, C., & Christovão, A. C. (2016). Desafios urbanos à democratização do acesso às oportunidades educacionais nas metrópoles brasileiras. Educação & Sociedade, 37(134), 171-193. [ Links ]

Small, M. L., & Newman, K. (2001). Urban poverty after the truly disadvantaged: The rediscovery of the family, the neighborhood, and culture. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 23-45. [ Links ]

Souza, M. A. de A. (2018). Abordagens recentes da pobreza urbana. Mercator, 17, e17020. [ Links ]

Stoco, S., & Almeida, L. C. (2011). Escolas municipais de Campinas e vulnerabilidade sociodemográfica: Primeiras aproximações. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 16(48), 663-694. [ Links ]

Thin, D. (2006). Famílias de camadas populares e a escola: Confrontação desigual de modos de socialização. In M. L. R. Müller, & L. P. Paixão (Orgs.), Educação, diferenças e desigualdades (pp. 17-55). EdUFMT. [ Links ]

Torres, H. G., Ferreira, M. P., & Gomes, S. (2005). Educação e segregação social: Explorando as relações de vizinhança. In E. Marques, & H. G. Torres (Orgs.), São Paulo: Segregação, pobreza e desigualdade. Senac. [ Links ]

1In the original: “Desconfiai do mais trivial, na aparência singelo. E examinai, sobretudo, o que parece habitual. Suplicamos expressamente: não aceiteis o que é de hábito como coisa natural. Pois em tempo de desordem sangrenta, de confusão organizada, de arbitrariedade consciente, de humanidade desumanizada, nada deve parecer natural. Nada deve parecer impossível de mudar.”

2For the selection of schools, two databases were used: Geres Project - School Generation -, Campinas Polo (longitudinal study that measured the performance of students in the early years of elementary school - Franco, Brooke and Alves, 2008) and the Vulnerability Project of the Population Studies Center, of the State University of Campinas (Unicamp) (study on social vulnerability in the metropolitan regions of Campinas and Santos - Cunha, 2006).

3It is important to highlight that, after empirical research, we observed that the E2 school, although mapped in a zone of absolute vulnerability, differs from the others in that it serves a population with better socioeconomic status and is located in a neighborhood with better conditions of infrastructure and services that the rest of its scope. This is an understandable aspect from what Érnica and Batista (2012) indicate, who state that, even among families in the neighborhood of schools located in areas of greater vulnerability, those with higher educational expectations seek to enroll their children in better organized and situated schools, which normally means institutions located in less vulnerable areas.

4In the original: “. . . es el resultado de una red de relaciones entre los sujetos individuales y colectivos entre sí, y entre éstos y el ambiente o espacio biofísico en el que se localizan temporal y geográficamente; una configuración compleja que surge de múltiples interacciones e interferencias de factores también resultado de esas relaciones.”

5Although the economic aspect is essential for the analysis of school performance, it is also necessary to recognize the cultural dimension that transforms it into a type of capital that can be mobilized to promote school success: the cultural capital.

6 During the 1970s, school failure began to be explained by the Theory of Cultural Need, which saw the cultural environment f the popular classes as a deficiency that would impact children’s psychological development, causing learning difficulties. Patto (1990) addresses this issue from the discussion of construction of school failure, returning to the theory of cultural need and criticizing it in order to bring another paradigm of analysis.

7In the original: “. . . estar em situação de vulnerabilidade social é mais abrangente que estar em situação de pobreza, pois se refere à condição de não possuir ou não conseguir usar ativos materiais e imateriais que permitiriam ao indivíduo ou grupo social lidar com a situação de pobreza. Dessa forma, os lugares vulneráveis são aqueles nos quais os indivíduos ou grupos sociais enfrentam riscos e a impossibilidade de acesso a serviços e direitos básicos de cidadania, como condições habitacionais, sanitárias, educacionais, de trabalho e de participação e acesso diferencial à informação e às oportunidades oferecidas de forma mais ampla àqueles que possuem essas condições.”

8In the original: “Por vulnerabilidad social entendemos la incapacidad de una persona o de un hogar para aprovechar las oportunidades, disponibles en distintos ámbitos socioeconómicos, para mejorar su situación de bienestar o impedir su deterioro.”

9In the original: “Las estructuras de oportunidades se definen como probabilidades de acceso a bienes, a servicios o al desempeño de actividades. Estas oportunidades inciden sobre el bienestar de los hogares, ya sea porque permiten o facilitan a los miembros del hogar el uso de sus propios recursos o porque les proveen recursos nuevos.”

10In the original: “Um dos consensos sobre o conceito de vulnerabilidade social é que apresenta um caráter multifacetado, abrangendo várias dimensões, a partir das quais é possível identificar situações de vulnerabilidade dos indivíduos, famílias ou comunidades. Tais dimensões dizem respeito a elementos ligados tanto às características próprias dos indivíduos ou famílias, como seus bens e características sociodemográficas, quanto àquelas relativas ao meio social em que estão inseridos. O que se percebe é que, para os estudiosos que lidam com o tema, existe um caráter essencial da vulnerabilidade, ou seja, referir-se a um atributo relativo à capacidade de resposta diante de situações de risco ou constrangimentos.”

11In the original: “En rigor ellos pueden ser casi infinitos si pensamos en las posibilidades abstractas. Desde los más obvios como propriedades, ahorro, créditos, a otros menos obvios como amistades, pertenencia a organizaciones de ayuda mutua, hasta elementos que aunque lejanos pueden ser percibidos y utilizados en tanto recursos, tales como el tiempo y la capacidad de movilidad geográfica etc.”

12In the original: “. . . a análise microssocial dos recursos dos domicílios, das pessoas e de suas estratégias de mobilização não pode ser feita independentemente da análise macrossocial das transformações das estruturas de oportunidades”.

13In the original: “. . . os atores sociais não agem em um vazio, no qual dependem somente de sua capacidade de gestão de ativos, mas em um contexto histórico e social formado de oportunidades e de constrangimentos, uma vez que as estruturas de oportunidades dependem de fatores macrossociais.

14In the original: “a eficácia e a equidade do funcionamento da escola dependem, entre outros fatores, da qualidade e da isonomia do ambiente provido pelo espaço social da metrópole”.

15 In the original: “. . . enquadra-se na categoria geral de modelos explicativos fundados na hipótese da relação de causalidade entre certos acontecimentos e o contexto social no qual ocorrem. . . . Por outras palavras, trata-se de captar o efeito de relações sociais desenvolvidas no âmbito do lugar de moradia sobre desfechos ocorridos na vizinhança.

16In the original: “na área específica da educação, podemos pensar que as oportunidades e escolhas dos indivíduos são afetadas pela quantidade e qualidade de escolas oferecidas em suas vizinhanças”.

17In the original: “. . . están relacionadas con los recursos iniciales y el contexto social, cultural y económico de los estudiantes y sus familias. En tal sentido, permiten analizar de forma más compleja los problemas de acceso, permanencia y logros de los estudiantes, así como comprender con mayor precisión el origen de las desigualdades en la educación, por supuesto no exclusivamente de carácter educativo.”

18In the original: “. . . las condiciones sociales para el aprendizaje son variables y cambiantes en cada país, comunidad y familia. Funcionan como círculos concéntricos entre las esferas de relaciones mencionadas y engendran tanto hacia fuera como hacia dentro activos o pasivos que posibilitan o dificultan los procesos educativos de los niños las niñas y adolescentes.”

19In the incorporated state, cultural capital appears in the form of durable dispositions of the organism, being linked to the family heritage with cultural references and knowledge considered appropriate and legitimate, facilitating the learning of school contents and codes (Bourdieu, 1998).

20In the assessment proposed by the Public School System, teachers classify students into knowledge groups, with the group one being the most advanced.

21In the original: “ouvir justificativas que apelam para argumentos como o da família ser desestruturada, quando o assunto se refere às dificuldades escolares enfrentadas por alunos”.

22In the original: “Otra cuestión que es importante de colocar en debate es la relación entre vulnerabilidad/exclusión y violencia. . . . La violencia no sólo fue observada en lo que denominamos vulnerabilidad extrema/letal, sino también en el hecho de privar de bienes y servicios (vulnerabilidad socioeconómica), de limitar la agencia política (vulnerabilidad jurídico-legal) y de negar recursos y espacios para el desarrollo cultural y la afirmación simbólica (vulnerabilidad cultural-ideológica).”

23In the original: “Relação que se mostra mais complexa com o aumento do acesso à escola dos filhos e das filhas dos coletivos feitos e mantidos tão desiguais em nossa história”.

24In the original: “na medida em que o compromisso não pode ser um ato passivo, mas práxis - ação e reflexão sobre a realidade -, inserção nela, ele implica indubitavelmente um conhecimento da realidade”.

Received: May 13, 2020; Accepted: December 11, 2020

texto en

texto en