Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.51 São Paulo 2021 Epub 13-Oct-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147388

TEACHER EDUCATION AND TEACHING

MUSICAL EXPERIENCES THROUGH AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVES IN INITIAL TEACHER TRAINING

IUniversidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herrriko Unibertsitatea, Bilbao, Spain; baikune.dealba@ehu.eus

IIUniversidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herrriko Unibertsitatea, Bilbao, Spain; cristina.arriaga@ehu.eus

IIIUniversidad de Cantabria, Santander, Cantabria, Spain; elena.riano@unican.es

Music has proven to be a valuable tool for deepening self-knowledge and emotional development. This exploratory-descriptive study investigates the musical life experiences of a group of students on the Primary Education Teacher’s Degree at the University of Cantabria (Spain), describing the meanings they ascribe to musical experience and the links they see between music and their future teaching work, as well as possible lines of pedagogical action. Through an analysis of the autobiographical narratives and reflective discussion groups, the results show the relevance of music in prior experiences and in the identification of emotions and feelings, provide information on contexts and styles, and offer a perspective of music as an educational resource with strong emotional and creative potential.

Key words: TEACHER EDUCATION; MUSIC EDUCATION; PERSONAL NARRATIVES

La música ha demostrado ser un valioso instrumento para el autoconocimiento y el desarrollo emocional de la persona. Este estudio exploratorio-descriptivo indaga sobre las experiencias musicales vitales de un grupo de estudiantes del Grado de Maestro en Educación Primaria de la Universidad de Cantabria (España) y describe los significados y vínculos otorgados a la música en relación con su futura labor docente, así como posibles líneas de actuación pedagógica. Mediante la narración de relatos autobiográficos y la reflexión en grupos de discusión, los resultados muestran la relevancia de la música en las experiencias previas e identificación de emociones y sentimientos, proporcionan información sobre contextos y estilos y ofrecen una concepción de la música como recurso educativo con un fuerte potencial emocional y creativo.

Palabras-clave: FORMACIÓN DE PROFESORES; EDUCACIÓN MUSICAL; NARRATIVAS PERSONALES

A música tem se mostrado um instrumento valioso para o autoconhecimento e desenvolvimento emocional. Este estudo exploratório-descritivo investiga as experiências de vida musical de um grupo de estudantes de Formação de Professores do Ensino Fundamental [Grado de Maestro en Educación Primaria] da Universidad de Cantabria (Espanha), descrevendo os significados e vínculos dados à música em relação ao seu futuro trabalho docente, bem como as possíveis linhas de ação pedagógica. Através da narração de histórias autobiográficas e da reflexão em grupos de discussão, os resultados mostram a relevância da música em experiências anteriores e a identificação de emoções e sentimentos, fornecem informações sobre contextos e estilos, e oferecem uma concepção da música como um recurso educativo com forte potencial emocional e criativo.

Palavras-Chave: FORMAÇÃO DE PROFESSORES; EDUCAÇÃO MUSICAL; NARRATIVAS PESSOAIS

La musique s’est avérée être un instrument précieux pour la connaissance de soi et le développement émotionnel. Cette étude exploratoire-descriptive porte sur les expériences de vie musicale d’un groupe d’étudiants du Grado de Maestro en Educación Primaria de la Universidad de Cantabria (Espagne), en décrivant les significations et les liens attribués à la musique en rapport avec leur futur travail d’enseignement, ainsi que les lignes d’action pédagogique possibles. Par le biais de récits autobiographiques et de la réflexion en groupes de discussion, les résultats montrent la pertinence de la musique dans les expériences précédentes et l’identification des émotions et des sentiments, fournissent des informations sur les contextes et les styles et proposent une conception de la musique comme ressource éducative à fort potentiel émotionnel et créatif.

Key words: FORMATION DES ENSEIGNANTS; ÉDUCATION MUSICALE; RECITS AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUES

Despite music being included on initial teacher training programs (García & Lorente, 2017), it is not always approached with the emotional dimension (Campayo & Cabedo, 2016) or its potential to deepen a person's self-knowledge in mind (Colomo & Domínguez, 2015). In recent years, research into the use of critical incidents in further education has been growing (Sánchez-Sánchez & Jara-Amigo, 2015). Some studies focus on subjective experiences of high emotional impact that are able to transform a person, to change the way they view or understand themselves, and that lead them to face new opportunities for building meaning and perspective (Valdés et al., 2016).

This kind of experience encourages reflection, observation, and the identification of elements and events that can influence and favor a person’s learning, and that Burnard (2005) describes as “significant musical encounters”. These are prior musical experiences that have had a special effect on the life of a student, that can help visualize the personal musical journey, encouraging reflection on episodes that have marked each individual’s life experience.

Our study explores the meanings of music and the life experiences of a group of students on the Primary Education1 program at Universidad de Cantabria (Spain) with two key objectives: 1) to investigate the musical experiences of future teachers through a process of self-reflection 2) to describe the meanings students ascribe to these experiences and the impacts they believe music will have on their future work as teachers.

Theoretical framework Music as a transformative experience

The description of prior experiences and the evocation of memory and of actions taken in meaningful contexts strengthens a person’s connection to themselves and contributes to their personal development. Transformative experiences have been studied under a range of different approaches (Valdés et al., 2016), all centered on self-knowledge and personal development through subjective experience. Reflection on these events is a fundamental factor for valuable and meaningful learning built around personal experience.

Critical Incidents are perhaps one of the research proposals most closely linked to education, as their analysis explores the effect of transformative events and their potential for becoming vectors of improvement in the teaching-learning process. A critical incident is unexpected and, whether positive or negative, has a high emotional impact on a person’s life. Their use in the field of education favors transformative learning and critical reflection (Monereo et al., 2015). We are especially interested in critical incidents as they can bring about a change in the future teacher’s professional identity and the elements that it comprises, be they related to instruction or teaching strategies, or even the emotional interpretations that these strategies involve (Sockman & Sharma, 2008; Monereo & Badía, 2011). Moreover, critical incidents “may be useful as an intervention tool to encourage more self-awareness in the people involved, analyzing the actions taken, and to propose, or in some cases establish, alternate courses of action for similar future incidents”2 (Bilbao & Monereo, 2011, p. 138, own translation).

Nevertheless, the meaning of an incident is not found in the incident itself, but in the person's interpretation of the event. This allows critical incidents to work as a tool for personal reflection, facilitating learning processes (Tripp, 2012). Indeed, it is this kind of reflection that fosters a better understanding of the self, and that will provide foundations for the students’ future roles as teachers (Riaño, 2017).

The strong connection between music and the emotions, and the important role that emotions play in recalling, describing, and integrating lived experiences into our personal body of knowledge (Hebert, 2009), are factors that we must bear in mind not only in music education, but in education in general. Music can help people “use and construct valuable experiences for their own lives and education through musical artistic experience”3 (Touriñán & Longueira, 2010, p. 157, own translation).

Moreover, some studies highlight the need to establish music education as a means to encouraging the development of reflection skills, responsibility, work ethic, and reaction to criticism, which are all vital qualities in a society of active and engaged citizens (Regelski & Gates, 2009). The idea is that a person who has honed these qualities will be better placed to react confidently in the face of any given social context (Fernández-Jiménez & Jorquera-Jaramillo, 2017).

There are other studies that have hit upon the learning and reflective benefits of students expressing themselves about their experiences with music, music education, and school life in general (Burnard & Björk, 2010). The discovery of musical incidents and the search for connections induced reflection on the meanings of prior life experiences. The process leads to an improved understanding of one’s own identity (Burnard, 2005; Adler, 2012), and a more complete and highly contextualized self-knowledge based on experience.

Personal narratives

Building a personal narrative provides structure for the sense of self and identity. Telling stories based on personal experience also leads to the creation of a narrative identity (Sparkes & Devís, 2007) and provides space for reflection as to why we think, feel, and act in a specific way (Bolívar et al., 2001; Silvennoinen, 2001). Stories about how we feel, or about our opinions on certain ideas, are what define us to others, and as such carry a lot of weight in one's construction of self-identity (Baker, 2005, 2014).

When we are offered the chance to explore the presence of music at different moments in our lives, we are able to reconnect with those experiences in a process that can also be heard and valued by others, fostering empathy alongside an exchange of narratives (Richardson, 2012). Autobiographical storytelling becomes just one more tool in the process of building self-knowledge and creating a personal and professional identity (Carrillo & Vilar, 2016). The process puts music front and center, recognizing its presence in one form or another in the lives of students, future teachers (Adler, 2012), and musicians (Pitts, 2012). Teacher training that allows room for this kind of subjective experience encourages student identities to grow, rebuild, and transform (Castañeda, 2013; Philpott, 2016).

Furthermore, individual narratives also have a social character as they connect personal identities to the sociocultural environment in which they are developed, allowing for a three-dimensional understanding of the temporal and spatial context, as well as the interaction of person and society (Garvis & Pendergast, 2012). Sharing personal experiences with people who are in the same situation as oneself - in this case, the group all share the desire to become teachers - is a communicational, reflective, and dialogical practice that enriches the learning process as a whole (Bolívar & Domingo, 2006; Beineke, 2012; Castañeda, 2013). This is a democratic approach, where the participation and the voice of the students is seen as a tool for the construction of a new professional teaching culture (Ceballos & Susinos, 2014).

Methodology

Design

This was a qualitative study (Denzin & Lincoln, 2012) applied to the arts (Luque & Cruz, 2016) that adopted an exploratory-descriptive design through an approach of self-reflective narrative construction (Cornejo et al., 2008; Verd & Lozares, 2016).

Instruments

Two instruments were used to collect data. The first, autobiographical stories, related to the first research objective, allowed us to inquire into the musical experiences of future teachers. The second, the discussion groups, were related to the second research objective of describing participants' opinions on the meanings ascribed to music.

Participants

A group of 34 students (28 women and 6 men) took part, all of whom were on the Primary Education program at Universidad de Cantabria (Spain) and were aged between 18 and 20 years-old.

Procedure

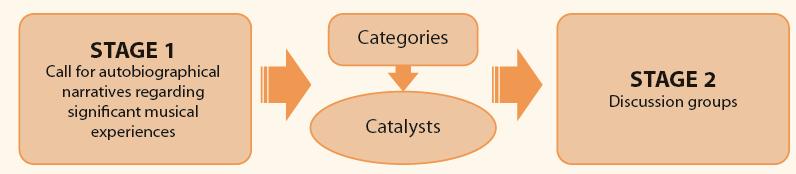

The exploratory study took place over 8 weeks, during normal class time. The study was split into two stages (Figure 1). In the first stage, students were asked to write stories narrating meaningful personal experiences where music played an important role. They were asked to use as much detail as possible in the descriptions. The information included in the students' stories was subjected to an inductive content analysis (Lorenzo, 2011; Andréu, 2001) and then built into an interpretive discourse. Using themed coding (Angrosino, 2012), we prioritized discourse elements that would allow for the extraction of common ideas or recurrent narratives from the different students’ stories. The same topic comprised groups of sentences with common elements. Each category contained several topics and served as a large conceptual group.

In the second stage, the results obtained in each category were presented as catalysts, in question form, to start group conversations lasting 60 minutes. There were three mixed groups in all, two with 12 members and one with 10. The main points of debate centered on: 1) the meaning of music in the students’ prior experiences, 2) its link with their future teaching work, 3) different teaching strategies.

Following Callejo (2001), the specifics that characterize discussion groups were respected, and participants' contributions were allowed to flow freely to help foster personal interaction. The physical space was set up to maximize visual contact and natural conversation between participants. Before we analyze the data collected, it is worth making a brief note of how it was collected and transcribed. The decision was made to take audio recordings of the conversations, with no video so as to preserve a greater degree of participant anonymity. Transcriptions were taken according to the artisan transcribing method described by Farías y Montero (2005), wherein prior to transcription the researchers familiarize themselves with the data and take stock of how its levels of complexity and nuance may be affected when moving to written format. The information gathered was then analyzed in a similar way to the information from stage 1.

Results

Results of story analysis

When recounting their experiences, the students for the most part associated music with moods like relaxed (13.2%), happy or carefree (10.5%), and enjoyment (7.9%), and to a lesser extent with safety, euphoria, surprise, and wellbeing. Similarly, emotions such as happiness, sadness, energy and joy, enthusiasm, and reminiscence were present in the stories (5.3%).

Participants related music with activities such as listening (30%), dancing (18.3%), singing and playing instruments (16.7%), rhythmic development and creation (5%), as well as body movements, exploration, and imagination.

The students identified a variety of styles of music in their significant experiences, among which classical (11.5%) was most prevalent, followed by rock, pop, traditional, musicals, and soundtracks (7.7%). Other genres named included electro-Latino, reggaeton, bachata, rap, and trap.

Following the textual analysis of the stories, other topics regarding the contexts in which these experiences took place emerged: in formal education (38.7%), with family (16.1%), with friends, socially, or through different media (12.9%), and in informal education (6.5%). It seems that in formal education, music was beneficial as a part of the students’ professional development and also culturally enriching (29.4%), but especially as a classroom tool (70.6%) in education for values, interpersonal relationships, teamwork, interdisciplinary learning, or even as a mnemonic resource.

Of the stories analyzed, 54.8% took place between the ages of 6 and 12 years, during primary school. The second most frequent age range, at 32.3%, was from 13 to 17 years, whereas the ranges of 3 to 5 years (9.7%) and over 18 years (3.2%) were less frequently cited.

TABLE 1 TOPICS AND CATEGORIES FROM STUDENT STORIES

| Categories | N.º of references to category | % | Topics | Subtotal n.º of references to topic | Subtotal % topics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions and moods | 38 | 18.8 | Relaxation | 5 | 13.2 |

| Reminiscence | 2 | 5.3 | |||

| Fun | 4 | 10.5 | |||

| Carefree | 4 | 10.5 | |||

| Safety | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Happiness | 2 | 5.3 | |||

| Euphoria | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Enthusiasm | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Surprise | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Wellbeing | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Rest | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Happiness | 2 | 5.3 | |||

| Energy | 2 | 5.3 | |||

| Adrenaline rush | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Sadness | 2 | 5.3 | |||

| Calm | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Enjoyment | 3 | 7.9 | |||

| Pleasure | 2 | 5.3 | |||

| Inhibition | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Solace | 1 | 2.6 | |||

| Music practice | 60 | 29.7 | Listening | 18 | 30 |

| Playing an instrument | 10 | 16.7 | |||

| Singing | 10 | 16.7 | |||

| Dancing | 11 | 18.3 | |||

| Creation | 3 | 5 | |||

| Coordination | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| Rhythmic development | 3 | 5 | |||

| Body movement | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| Exploration | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| Choreography | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| Imagination | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| Genres | 25 | 12.3 | Rock | 2 | 7.7 |

| Soundtracks | 2 | 7.7 | |||

| Pop | 2 | 7.7 | |||

| Reggaeton | 2 | 7.7 | |||

| Musicals | 2 | 7.7 | |||

| Jazz | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Traditional | 2 | 7.7 | |||

| Electro-Latino | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Bachata | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Rap | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Trap | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Hip-hop | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Punk | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Classical | 3 | 11.5 | |||

| Singer-songwriters | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Ballads | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Other | 1 | 3.8 | |||

| Categories | N.º of references to category | % | Topics | Subtotal n.º of references to topic | Subtotal % topics |

| Contexts | 31 | 15.4 | Family | 5 | 16.1 |

| Friends | 4 | 12.9 | |||

| Formal education | 12 | 38.7 | |||

| Media | 4 | 12.9 | |||

| Social environment | 4 | 12.9 | |||

| Informal education | 2 | 6.5 | |||

| Educational benefits | 17 | 8.4 | Personal and professional development | 5 | 29.4 |

| Classroom resource | 12 | 70.6 | |||

| Age | 31 | 15.4 | 3-5 years | 3 | 9.7 |

| 6-12 years | 17 | 54.8 | |||

| 13-17 years | 10 | 32.3 | |||

| >18 years | 1 | 3.2 | |||

| TOTAL | 202 | 100 |

Source: Created by the research group.

Group discussion results analysis

Objective 2 was to describe the meanings and links that participants, as future teachers, place on music. The following story touches on the main points debated in the three groups:

The majority of students agreed that music led to personal introspection. For example, Marta said: “Music gets you in touch with yourself and connects you with your interior” and Paula said: “Music helps you escape and helps you relax when you get home. You just forget the stress of the day. This is more positive than negative”. Lydia told the group that silence, as well as music, worked as a tool for introspection: “Silence is interesting for relaxing and meditating... It’s a moment for you to know yourself”.

There was some general agreement regarding the link between music and emotions. Ana stated: “It’s what I look for when I listen to music with a good beat. An adrenaline rush when I need an energy boost, and when I’m sad, something a bit slower”. In Juan’s opinion: “I have felt all kinds of emotions through music”. And Pedro and Álvaro both said that music was good for “identifying and managing emotions, understanding how you work, and why you like a particular genre of music”, “the vehicle for coming to terms with how we feel is dialogue. It helps us understand how we feel in a given moment and recognize the range of emotions that one music genre can produce”.

The participants also placed value on music as a classroom tool. In their opinion, emotional education is a fundamental part of their future work, and to that end music can be “a vehicle, not the only one, but a vital one” (Jesús). Likewise, “the teacher can use music to better understand their students’ personal profiles” (Carla).

It was broadly recognized that this kind of work has to begin with young students, and that these future teachers valued the Primary stage of education as “an important moment for building one’s personality, where the teacher is a meaningful figurehead for the children” (Rebeca). Each group agreed on the importance of encouraging musical activities at this stage of education. María believed that “Primary stage education is a great time for discovering oneself. Music can help us teach kids to be creative and express, through music, any feelings they may have”. Inés shared the same opinion, arguing that “it’s vital to encourage an interest in music in primary school. There isn’t much to teach, but just let the children and discover and explore music” highlighting, like Jesús, the introspective process, as he says, “it’s fundamental to allow children to explore music, and bring out what’s inside of them”.

The memories of several participants regarding their own musical education reveal the absence of a practical approach. Some statements claimed: “we had a classroom full of instruments but almost never played them” (Celia), “the classes were very repetitive and theoretical instead of playing the instruments” (Sole), “everything was so theoretical. We didn’t do activities or dance” (Nuria); and there was even one opinion that, besides the overly theoretical approach, touched on the lack of professional calling on the part of the teachers: “Our music teachers seemed to hate teaching, they wanted to cover only theory and never play instruments” (Ana).

In contrast, the most enjoyable music-related experiences were related to big events or school celebrations. Juan said that “at primary school, our recitals were quite creative, and we were very motivated to get in touch with music”. Sonia pointed out that her “musical experiences weren't in music class, but in extracurricular musical activities” and, likewise, Aitor said that “it was during the celebrations for Christmas and Easter that we all got to play instruments”.

All the participants agreed that age was a factor in determining the type of musical experience, with adolescence emerging as a stage where the influence of friends, perhaps having one’s own phone, or beginning to go out were things that would decide the type of musical experiences lived. Some statements to this effect included: “when you are young, you don’t have your own phone, but from 12 and up you can start to listen to whatever you like” (Javier) “because you listen to what your friends listen to” (Aitor) “you listen to music when you go out to parties” (Elsa).

Students also valued their family contexts as environments where they could begin to listen to music, learn to love it, and cultivate their own musical tastes. Rosa said: “my brother used to listen to what I listened to, but after he was about 8, he began to seek out his own stuff”. Lucía pointed out that in family gatherings “you listen to what your cousins are into, but then you get a feel for your own tastes”. Other students named their parents as musical influences. As Carmen said: “I always listened to music from my parents’ era. Now I go to bars and listen to other stuff”.

As future teachers, the participants energetically debated music’s potential in education, proposing ideas that covered the diversity that exists nowadays in the typical classroom, as well as the active participation of their future students. In this regard, Luisa said “the students can propose what music to use in class, as a means to discovering other musical styles and getting to know other cultures: It’s good because you aren’t always willing to listen to new things on your own. And the more you know, the more you know yourself. It gives you more opportunities”. For Maite: “Now that there is such a diversity of cultures, of other countries, I think it’s good that they bring music from home, so that their classmates can listen to something that they normally might not. From Africa, or traditional music from Spain” and in Gema’s opinion: “Them bringing in music that their families listen to is good, because some students will come from different countries… it's interesting and it helps you understand the environment”.

Some students were interested in using music to collaborate with other teachers (general education teachers and specialists from different subjects): “it’s about getting together, talking, and using your imagination to work together. Coordinating like that with other teachers would help us explore other possibilities” (Berta). Strengthening interdisciplinary work was something that several participants agreed was important, as they pointed out that all content and all subjects can be approached through music (mathematics, languages, science, technology...), to work through emotions and global themes such as education in values and morals. Music could also be used as a mnemonic device. María said: “You can use music to teach other subjects, with a song, for example. That way you learn without even realizing. What’s more, if you like the song, you might even just sing it because you enjoy it, regardless of the lyrics”.

There was a consensus across the three groups regarding the convenience of using a wide variety of musical styles in the Primary classroom, such as pop, rock, reggae, or classical music, among others, with the exception of reggaeton. All the participants considered the use of this genre inappropriate. “Not reggaeton. I think I would even ban it” (Emilia), “the lyrics aren't age appropriate. I don't think you can use it to the benefit of anything” (Fátima). Although there was a person who pointed out that, sometimes, and due to it being a widely popular musical genre among young people, you might be able to change the lyrics to make them more appropriate: “I think you could change the words. What [the students] like is the rhythm” (Claudia).

The students also said that there needed to be more creativity when it came to proposing musical activities in the classroom. Sofía said that “you can use all kinds of objects to make sounds, alongside traditional instruments, even things that the students themselves create, so that they can have fun making music and experimenting with sound”.

Finally, it was pointed out that music is not widely present, currently, in their university education. Miriam asked: “why are all the other subjects covered every year, totaling more than 40 credits each, whereas music only has 6 credits? It should have more space on the curriculum”.

Discussion and conclusions

This exploratory-descriptive study was focused on investigating the meanings placed on music by a group of future teachers in their own life experiences, and how these experiences could affect their future teaching practice.

The students touched on events that had an emotional impact on their lives and learning processes by telling stories where music had played an important role (Burnard & Björk, 2010). Collective reflection through group discussion led to collective expression (Monereo et al., 2015) wherein shared experiences led to a great opportunity for personal development through increased self-knowledge (Valdés et al., 2016). This is why the participants linked their stories to personal introspection and connections between music and emotions, feelings, memories, and moods (Burnard, 2005), most of which were positive and considered to be of importance to their life experience (Hebert, 2009).

The musical incidents touched on by the students were tied to both formal and informal contexts, and both these contexts were important contributors to the formation of personal identity (Baker, 2005, 2014), an identity built on life experiences linked to music (Touriñán & Longueira, 2010). Formal educational contexts were more often associated with a lack of practical musical experience, while non-formal and informal contexts were more frequently cited as fun experiences linked to family life and friendship. This leads us to reconsider the way in which music should be included in the classroom, using its full potential in education (Touriñán & Longueira, 2010) and bearing in mind that often experiences from outside the school context appear to be more meaningful and influential in personal growth than those that take place in a traditional classroom. That is to say, education should consider personal interaction, society, and context (Garvis & Pendergast, 2012).

As Burbules (2012) points out, there are currently blurred lines between the formal, non-formal, and informal contexts, and rather than in terms of educational potential, the clearest differences are merely physical ones; as such, each individual tailors their own educational experience, where the three contexts interact and intertwine. On the other hand, informal contexts play a significant role in our understanding of who we wanted to be and who we have become. According to the results of this study, musical references also come from situations external to the school context, such as in the company of family and friends.

The narrated experiences showed that the students were open to recalling emotions and introspection, but they also showed that these future teachers connected the same experiences to the construction of a future professional identity (Philpott, 2016; Gorzoni & Davis, 2017). Indeed, they all reflected on the didactic possibilities of music and its classroom potential (Burnard, 2005). Music was generally perceived as a valuable and necessary asset that can contribute to a person’s emotional development (Campayo & Cabedo, 2016). Some of the ideas that arose in this regard are related to introspection, identification and emotional management, expression, and creativity. Interest was also shown for the incorporation of a number of musical styles int he classroom, and students were open to experimental and exploratory musical activities (Brinkman, 2010). Likewise, the study highlights the importance placed on music as an interdisciplinary and participatory tool (Young, 2018), especially in terms of teacher collaboration.

These future teachers placed special emphasis on the need to encourage musical exploration from an early age, making a connection between the students’ own musical worlds and the classroom musical experience, which is frequently viewed as limited or unstimulating rather than a vital space where feelings and subjectivities converge (Vargas et al., 2017).

Lastly, the lack of musical exposure in schools and universities is also evident from these results, which is in line with Hennessy’s (2017) findings that there is little musical education on initial teacher training programs.

Future research in this field should focus on offering educational alternatives that invite student reflection through introspection and foster an understanding of the many meanings music can have. The research team would like to invite other teachers to replicate similar experiences in order to move towards an initial teacher training program where music is far more present.

REFERENCES

Adler, A. (2012). Rediscovering musical identity through narrative in pre-service teacher education. In M.S. Barret, & S. L. Stauffer (Ed.), Narrative sundings: An anthology of narrative inquiry in music education (pp. 161-178). Springer. [ Links ]

Andréu, J. (2001). Técnicas de análisis de contenido: Una revisión actualizada. Fundación Centro de Estudios Andaluces. http://mastor.cl/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Andreu.-analisis-de-contenido.-34-pags-pdf.pdf [ Links ]

Angrosino, M. (2012). Etnografía y observación participante en investigación cualitativa. Morata. [ Links ]

Baker, D. (2005). Music service teachers’ life histories in the United Kingdom with implications for practice. International Journal of Music Education, 23(3), 263-277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761405058243 [ Links ]

Baker, D. (2014). Visually impaired musicians’ insights: Narratives of childhood, lifelong learning and musical participation. British Journal of Music Education, 31(2), 113-135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051714000072 [ Links ]

Beineke, V. (2012). A reflexão sobre a prática na pesquisa e formação do professor de música. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 42(145), 180-202. http://publicacoes.fcc.org.br/index.php/cp/article/view/53/69 [ Links ]

Bilbao, G., & Monereo, C. (2011). Identificación de incidentes críticos en maestros en ejercicio: Propuestas para la formación permanente. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 13(1), 135-151. http://redie.uabc.mx/vol13no1/contenido-bilbaomonereo.html [ Links ]

Bolívar, A., & Domingo, J. (2006). La investigación biográfica y narrativa en Iberoamérica: Campos de desarrollo y estado actual. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4). http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/4-06/06-4-12-s.htm. [ Links ]

Bolívar, A., Domingo, J., & Fernández, M. (2001). La investigación biográfico-narrativa en educación: Enfoque y metodología. La Muralla. [ Links ]

Brinkman, D. J. (2010). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity. Arts Education Policy Review, 111(2), 48-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910903455785 [ Links ]

Burbules, N. C. (2012). El aprendizaje ubicuo y el futuro de la enseñanza. Encounters/Encuentros/Rencontres on Education, 13, 3-14. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4100463 [ Links ]

Burnard, P. (2005). El uso del mapa de incidentes críticos y la narración para reflexionar sobre el aprendizaje musical. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 2(2). http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/RECI/article/view/RECI0505110002A [ Links ]

Burnard, P., & Björk, C. (2010). Using student voice research to understand and improve musical learning. In J. Finney & Ch. Harrison (Ed.), Whose music education is it? The role of the student voice (pp. 24-32). National Association of Music Educators NAME. [ Links ]

Callejo, J. (2001). El grupo de discusión: Introducción a una práctica de investigación. Ariel Practicum. [ Links ]

Campayo, E., & Cabedo, A. (2016). Música y competencias emocionales: Posibles implicaciones para la mejora de la educación musical. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 13, 124-139. https://doi.org/10.5209/RECIEM.51864 [ Links ]

Carrillo, C., & Vilar, M. (2016). Percepciones del profesorado de música sobre competencias profesionales necesarias para la práctica. Opción, 32(n. especial 7), 358-382. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/457279 [ Links ]

Castañeda, M.A. (2013). Identidades en proceso de formación. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, (436), 14-17. http://www.cuadernosdepedagogia.com/content/Inicio.aspx [ Links ]

Ceballos, N., & Susinos, T. (2014). La participación del alumnado en los procesos de formación y mejora docente. Una mirada a través de los discursos de orientadores y asesores de formación. Profesorado. Revista de Curriculum y Formación del Profesorado, 18(2), 228-244. https://www.ugr.es/~recfpro/rev182COL5.pdf [ Links ]

Colomo, E., & Domínguez, R. (2015). Definiendo identidades: El “canciograma” como herramienta metodológica de autoconocimiento. Revista Electrónica Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 13(2), 131-146. https://revistas.uam.es/reice/article/view/2794 [ Links ]

Cornejo, M., Mendoza, F., & Rojas, R. C. (2008). La investigación con relatos de vida: Pistas y opciones del diseño metodológico. PSYKHE, 17(1), 29-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22282008000100004 [ Links ]

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2012). Manual de investigación cualitativa. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Farías, L., & Montero, M. (2005). De la transcripción y otros aspectos artesanales de la investigación cualitativa. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(1), 1-14. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/160940690500400104 [ Links ]

Fernández-Jiménez, A., & Jorquera-Jaramillo, M.-C. (2017). El sentido de la educación musical en una educación concebida como motor de la economía del conocimiento: Una propuesta de marco filosófico. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 14, 95-107. https://doi.org/10.5209/RECIEM.54834 [ Links ]

García, E., & Lorente, R. (2017). De receptor pasivo a protagonista activo del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje: Redefinición del rol del alumnado en la Educación Superior. Opción, 33(84), 120-153. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6402368 [ Links ]

Garvis, S., & Pendergast, D. (2012). Storying music and the arts education: The generalist teacher voice. British Journal of Music Education, 29(1), 107-123. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051711000386 [ Links ]

Gorzoni, S., & Davis, C. (2017). O conceito de profissionalidade docente nos estudos mais recentes. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 47(166), 1396-1413. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053144311 [ Links ]

Hebert, D.G. (2009). Musicianship, musical identity, and meaning as embodied practice. In Th. A. Regelski, & J. T. Gates (Eds.), Music Education for Changing Times (pp. 39-55). Springer. [ Links ]

Hennessy, S. (2017). Approaches to increasing the competence and confidence of student teachers to teach music in primary schools. Education 3-13, 45(6), 689-700. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2017.1347130 [ Links ]

Lorenzo, O. (2011). Análisis cualitativo de textos sobre multi e interculturalidad. DEDiCA. Revista de Educação e Humanidades, (1), 535-546. https://doi.org/10.30827/dreh.v0i1.7186 [ Links ]

Luque, P. J., & Cruz, C. M. (2016). Prácticas cualitativas para la investigación sobre las artes. In M. I. Moreno, & M. P. López-Peláez (Coords.), Reflexiones sobre investigación artística e investigación educativa basada en las artes (pp. 43-59). Síntesis. [ Links ]

Monereo, C., & Badía, A. (2011). Los heterónimos del docente: Identidad, selfs y enseñanza. In C. Monereo, & J. I. Pozo (Eds.), La identidad en psicología de la educación: Enfoques actuales, utilidad y límites (pp. 59-77). Narcea. [ Links ]

Monereo, C., Monte, M., & Andreucci, P. (2015). La gestión de incidentes críticos en la universidad. Narcea. [ Links ]

Philpott, C. (2016). Narratives as a vehicle for mentor and tutor knowledge during feedback in initial teacher education. Teacher Development, 20(1), 57-75. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13664530.2015.1108927?src=recsys [ Links ]

Pitts, S. (2012). Chances and choices: Exploring the impact of music education. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Regelski, Th. A., & Gates, J. T. (2009). Music education for changing times. Springer. [ Links ]

Riaño, M.E. (2017). Creación sonora a partir de las narrativas biográficas en el aula de música: narrativas sonoras. In A. Murillo, & M. Díaz (Coords.), La mecánica de la creación sonora (pp. 109-134). Institut de Creativitat i Innovacions Educatives de la Universitat de València. [ Links ]

Richardson, C. (2012). Narratives from Preservice Music Teachers: Hearing their voices while singing with the Choir. In M. S. Barret, & S. L. Stauffer (Eds.), Narrative soundings: An anthology of narrative inquiry in music education (pp. 179-200). Springer. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Sánchez, G. I., & Jara-Amigo, X. E. (2015). Visión del trabajo docente en el ámbito de la evaluación, que comienza a construir el profesorado en formación, a partir del uso de incidentes críticos en los procesos de formación práctica. Revista Electrónica Educare, 19(2), 231-255. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/ree.19-2.14 [ Links ]

Silvennoinen, M. (2001). Relatos sobre deporte e identidad en mujeres y hombres. In J. Devís (Ed.), La educación física, el deporte y la salud en el siglo XXI (pp. 203-212). Marfil. [ Links ]

Sockman, B. R., & Sharma, P. (2008). Struggling toward a transformative model of instruction: It’s not so easy!. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(4), 1070-1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.11.008 [ Links ]

Sparkes, A. C., & Devís, J. (2007). Investigación narrativa y sus formas de análisis: Una visión desde la educación física y el deporte. In W. Moreno, & S. Maryory (Eds.), Educación, cuerpo y ciudad. El cuerpo en las interacciones e instituciones sociales (pp. 43-68). Funámbulos Editores. [ Links ]

Touriñán, J. M., & Longueira, S. (2010). La música como ámbito de educación. Educación ‘por’ la música y educación ‘para’ la música. Teoría de la Educación, 22(2), 151-181. https://doi.org/10.14201/8300 [ Links ]

Tripp, D. (2012). Critical incidents in teaching: Developing professional judgement. Routledge. [ Links ]

Valdés, A., Coll, C., & Falsafi, L. (2016). Experiencias transformadoras que nos confieren identidad como aprendices: Las experiencias clave de aprendizaje. Perfiles Educativos, 38(153), 168-184. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2016.153.57643 [ Links ]

Vargas, C., Ledezma Delgado, L. J., & Castro, S. (2017). El Aula, espacio de sentido y significado [Tesis de Maestría, Universidad de Manizales]. RiDUM - Repositório Institucional Universidad de Manizales. https://ridum.umanizales.edu.co/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12746/3314/Sandra%20Milena%20Castro%20Plazas%2c%202017.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Verd, J. M., & Lozares, C. (2016). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa: Fases, métodos y técnicas. Síntesis. [ Links ]

Young, G. (2018). Creative interdisciplinary in the arts. In N. H. Hensel (Ed.), Exploring, experiencing, and envisioning integration in US Arts Education (pp. 15-26). Palgrave MacMillan. [ Links ]

1Initial teacher training for Infant (students aged up to 6) and Primary (students aged up to 12) teachers is taught at a university level over 4 years for a minimum of 240 ECT credits, and in Spain is offered on programs called BA in Teaching/BA in Education/BA in Infant Education or in Primary Education. http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/contenidos/estudiantes/portada.html; https://www.educacion.gob.es/notasdecorte/busquedaSimple.action

2In the original: “puede resultar de utilidad como instrumento de intervención para provocar la toma de conciencia de las personas implicadas en el incidente crítico, valorando las actuaciones desencadenadas, y para proponer, y en su caso instaurar, actuaciones alternativas frente a sucesos similares”.

3In the original: “usar y construir experiencias valiosas para su propia vida y formación integral, desde la experiencia artística musical”.

Received: May 17, 2020; Accepted: April 26, 2021

texto en

texto en