Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.52 São Paulo 2022 Epub 08-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053149122

THEORIES, METHODS, EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

ETHNOGRAPHY WITH CHILDREN IN TIMES OF PANDEMIC: AN ETHICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL REFLECTION

IUniversidade Federal do Maranhão (UFMA), Imperatriz (MA), Brazil;

This article is concerned with the ethical and methodological aspects of research carried out during 2020, which investigated the children’s representation of Covid-19 in the Brazilian state of Maranhão. It queries the fabrication of an ethnography at a distance (with the children’s parents as mediators), taking digital technologies as a means to access children and their narratives through short interviews, audio recordings, and drawings. Adhering to social distancing rules, without access to direct observation, it raises issues regarding the process of obtaining information and transforming it into data through systematization and analysis.

Key words: ETHNOGRAPHY; CHILDREN; PANDEMIC; DRAWINGS

Este artigo trata dos aspectos ético-metodológicos de uma pesquisa realizada em 2020, que investigou as representações de crianças maranhenses da covid-19. Busca-se problematizar a produção de uma etnografia a distância, tomando os pais das crianças como mediadores e fazendo uso das tecnologias digitais para ter acesso às crianças e às suas narrativas, por meio de pequenas entrevistas e áudios, além da elaboração de desenhos. Cumprindo as regras de distanciamento social, sem poder fazer uso da observação direta, problematiza-se o processo da obtenção das informações até a sua transformação em dados, por meio de sistematização e análise.

Palavras-Chave: ETNOGRAFIA; CRIANÇAS; PANDEMIA; DESENHOS

Este artículo trata de los aspectos éticos-metodológicos de una investigación realizada en 2020, cuyo objetivo era investigar las representaciones de niños marañonenses (en Brasil) sobre la covid-19. Se busca problematizar la producción de una etnografía a distancia, tomando a los padres de los niños como mediadores y utilizando las tecnologías digitales para tener acceso a los niños y a sus narrativas a través de pequeñas entrevistas por medio de audio, y la elaboración de dibujos. Cumpliendo con las reglas de distanciamiento social y sin posibilidad de utilizar la observación directa, problematizo el proceso de obtención de las informaciones hasta su transformación en datos, por medio de la sistematización y el análisis.

Palabras-clave: ETNOGRAFÍA; NIÑOS; PANDEMIA; DIBUJOS

Cet article traite des aspects éthico-méthodologiques d’une recherche menée en 2020 concernant les représentations d’enfants du Maranhão, Brésil, sur le covid-19. Il cherche à problématiser la production d’une ethnographie réalisée à distance, avec recours aux parents comme médiateurs et aux technologies numériques pour accéder aux enfants et à leurs récits, au moyen de courts entretiens, d’audios et de dessins. Dans le respect des règles de distanciation sociale, sans recourir à aucune observation directe, le processus de recueil d’informations a été problématisé à travers la systématisation et l’analyse jusqu’à sa transformation en données. Cet article se veut une contribution aux études sur l’enfance et à la méthodologie de la recherche avec les enfants.

Key words: ETHNOGRAPHIE; ENFANTS; PANDÉMIE; DESSINS

This article results from an analysis of the ethical and methodological trajectory of research investigating how children in the Brazilian state of Maranhão1 represent Covid-19. Research was carried out during the Coronavirus pandemic, which consumed the world, between the months of March and April 2020, while social distancing measures were in place, as imposed by the government of the state of Maranhão.

Data production thus occurred at a distance, and this article was written in solitude and social distancing, not only between the researcher and her child interlocutors, but also between the researcher and her peers: colleagues, supervisees, and members of her research team.

Nonetheless, while I was unable to have direct conversations with the children who are the main subjects of this research, I discovered other means of establishing dialogue - with the field, if not with the subjects themselves. What, after all, is data production but the creative encounter (Wagner, 2010) of researcher with her interlocuters? Might not this encounter and its conversations be carried out via digital technologies? Indeed, as Guber (2005) reminds us, the field does not provide us with data, but with information that we equivocally call data. This information is transformed into data during the reflexive process, after it has been collected. Or, as Magnani says:

. . . the nature of explanation via ethnography is based on an insight which allows us to reorganize data seen to be fragmentary, information which is yet dispersed, clues which remain disconnected, in a new arrangement that is no longer a native arrangement (but which starts from it, accounts for it, was instigated by it) nor is it that with which the researcher began research. (2002, p. 17, own translation).

The information provided by social actors thus only becomes data in the process of systematization and analysis, whether the information is obtained directly from interlocutors or at a distance - through technologies and social networks (a new way of carrying out armchair anthropology or of “being there”). Favret-Saada (2005, p. 160, own translation) rightly observes that we do not analyse while data is being produced: “the time for analysis will come later”.

If data is not given, but produced, then the ‘field’ does not necessarily have specific coordinates, nor is it synonymous with ethnography, as we tend to assume.

The field is not a geographical space, a patch of land self-defined by its natural limits (sea, jungle, streets, walls), but rather a decision made by the investigator which takes into account scopes and actors; it is a content for the raw material, the information which the researcher must turn into material that can be used for investigation (Guber, 2005, p. 83, own translation).

It is not the field that defines ethnography, but a personal experience with that field or those subjects. Fieldwork is not the prerogative of anthropology, nor does anthropology have a monopoly over it. Many researchers, from all disciplines, have been going to the field since the end of the 19th century. But the anthropological “field” is not just about going there and coming back, it is something else more complex: a prolonged coresidence, a systematic observation, an effective communication (in a native tongue), a mix of alliance, complicity, friendship, respect, coercion, and ironic tolerance (Clifford, 1995). Anthropological fieldwork is about establishing relations with people.

Doing ethnography2 with children for 18 years, the research I carried out before the pandemic was interrupted. Not least for involving children in care homes and Indigenous children, all of whom inhabit spaces that were restricted while social distancing measures were in place. With care homes and villages inaccessible, I began to ask how children in urban centres were dealing with the barrage of information about the pandemic that was being disseminated, and with the profound transformations that their daily life underwent.

Through this research I put together an ethnography of children’s conceptions of the Coronavirus - a term they adopted - including of how it is transmitted, of people affected by the virus, the notion of risk, its predictable and unpredictable consequences, thereby seeking to understand how Covid-19 affected children through their own interpretations of it all. Children’s representations and the information, interpretations and meanings they attributed to Covid-19 were studied through methods, techniques, and instruments that I present in this article by way of an affective-ethical itinerary.

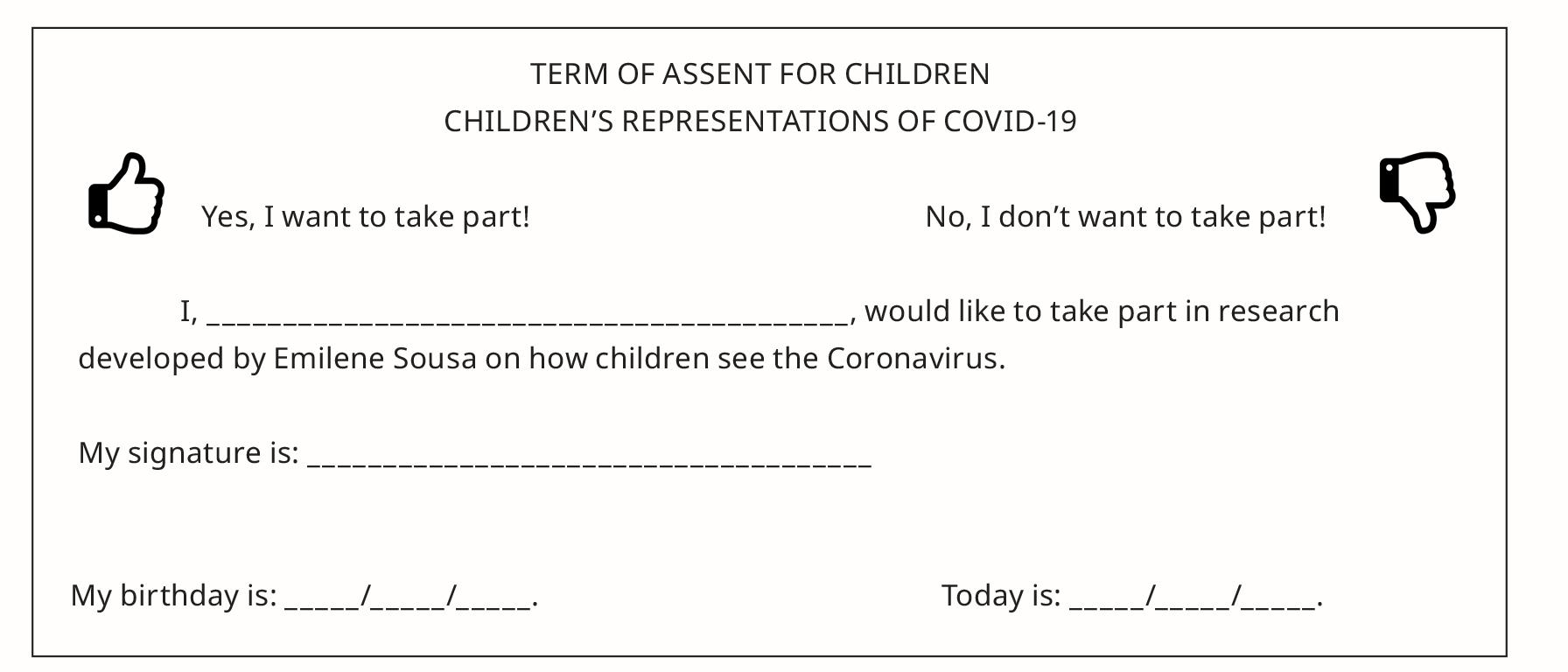

I will question the conditions for composing an ethnography in times of social distancing, without recourse to direct observation. The article is hence organized into two moments. The first is ethical, discussing the instruments used in research, such as the Free and Informed Term of Consent (FITC) and the terms of assent, as well as the exposure of children within the text. The second, methodological moment is divided into two sub-items: first, I enquire into the conversations parents had with their children in audio recordings, based on semi-structured scripts; second, I deal with the elaboration of drawings as an important research tool, to which children attribute meanings registered in audio recordings which we call explanations of drawings.

From ethnographic experience to an ethnography without experience

After so many experiences with children in the field - in villages, maroon settlements, extractive reserves, stilt houses, farmsteads - I was faced with an obvious challenge. In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, unable to access those places which were my field sites at the time, I felt exiled from the village and the care home, places which provide the conditions of existence for childhood and to which I had dedicated my participant observation in the last years.

In my own home, where I received news of the sanitary crisis, I wondered how this information was accessed by children, if they were being denied this information or if their parents were translating it for them, how they appropriated this information, resignified it, how they processed the prevention and care of the disease, and how they managed to transmit this knowledge to their peers - in a horizontal transmission of knowledge (Delalande, 2001).

With my own 4-year-old at home, I often heard the most varied representations of the Coronavirus, on the need to greet people with one’s elbow, the use of masks, the importance of washing hands, of using sanitizing alcohol many times in a day, as well as a number of understandings that were not transmitted to him by me, but through social networks. Children quickly found tailor-made information for them through their favourite characters - such as the Turma da Mônica - and kid’s videos on YouTube channels which included commercials on the Coronavirus for children.

Preparing my project, I wrote a short and objective text meant for parents or caretakers - my mediators - asking that they help me reach children. The text explained the aims of my research, the methods I would use, and clarified questions that might arise concerning the ethics of it all, asking parents to record audios based on a semi-structured script, which I provided. Using the same script that would set up conversations with children delivered to me as audio recordings, which I called short interviews, I also asked that children draw and record audios explaining the drawings.3

Using this raw material - short audio interviews and drawings - I produced my first ethnography without being there, as Geertz (2005) would say. For the first time, participant observation was not my main guide, and I did not have a qualified informant (Malinowski 1984). I missed the small guides in villages or farmsteads who took me everywhere and taught me about places and people. Children no longer surrounded me everywhere, nor did they fight over who got to hold my hand as we walked. They did not invade my privacy, did not mess up my research material. I missed all of this, but I learned a new way of conducting ethnographic research. I discovered that it is possible to feel the loneliness that surrounds the ethnographic endeavour, so perfectly described by Malinowski (1984) and DaMatta (1978), without watching the launch or dinghy that left you on a tropical beach in the Trobriands sail out of sight, or without dwelling in a makeshift hut among the Timbira people, scribbling by moonlight endless fieldnotes. At home - surrounded by cell phones, laptops, social networks, messaging apps, the beeps that notified incoming messages from all corners of the state of Maranhão, and which inaugurated my new conditions as a researcher - I felt I was in the field. And alone.

If there needs to be negotiations with and acceptance by the subjects of research for there to be ethnography, I take recourse to Geertz (1989, p. 212, own translation), for whom: “The culture of a people is a set of texts, . . . which the anthropologist strains to read over the shoulders of those to whom it belongs”. If the anthropologist allows herself to read something, even something over the shoulders of the natives, she only does so with the permission (apparently disinterested or incidental) of the native, whether adult or child. This permission is essential, alleviating the loneliness that the anthropologist experiences in the field. Being minimally accepted enables us to at least share in the melody of the anthropological blues (DaMatta, 1978), a sort of “being together” rather than “being alone”. I confess that I had never felt as accepted as when I became aware of the amount of material I was receiving without even being seen. Of course, a small part of these subjects was also part of a network of affects I wove together - children of colleagues, friends, acquaintances, neighbours - but most of them were not. The research extrapolated this network of affects.

When negotiations do not take place in the field: Ethical and methodological issues

Caught unaware by pandemic, even before I could process the amount of information that was arriving, I was quickly relieved of my duties. Overnight, I saw myself working in home office, with my son being home schooled, having no option but to suspend ongoing research. I began to ask how children were dealing with the fear, concerns and apprehension of adults. With risk and imminent danger, having to estrange themselves from their grandparents (important figures during infancy), ceasing to attend school and changing their routine and halting extracurricular activities.4

I decided to investigate Maranhense children’s representations of Covid-19, and how they construct their experiences, asking if it is possible to carry out ethnography at a distance. “The ethnographic method does not blur into, nor should it be confused with, a technique; a range of techniques can be adduced during research, according to circumstances; ethnography is first and foremost a method of enclosing and apprehending than it is a set of procedures” (Magnani, 2002, p. 17, own translation). Thus, to fabricate an ethnography, we must adapt to the most adverse conditions and make use of the means at hand to produce a thick description of the object under study. A thick description involves the capacity to follow a stratified hierarchy of meaningful structures in terms of which the object under stud can be interpreted and experienced (Geertz, 1989).

My initial idea was to research only children in Imperatriz, in Maranhão. As I stated above, I wrote a text that asked parents or caretakers to record short interviews with children, between 3 and 7 years of age, and to ask them to draw and record explanations of the drawings. Along with the text I sent questions meant to guide the short interviews and drawings, in addition to a term of assent and a FITC for the parents, and a term of assent for the children. In the text intended for children, there were two drawings: one that should be coloured in if the child wanted to take part in the research, another which was to be coloured in by children who did not wish to take part. This term specifically targeted children who could not read or write, so that they would feel involved in decisions regarding their participation in the research.

The choice of this type of term of assent, specifically targeting children, stems from the recognition that even ways of obtaining consent are conceived of as involving adults, in an adult-centred pattern: written down, requiring signatures, and, in some cases, an understanding of rights (Sousa & Pires, 2020). This is why I believe in the term of assent is an ongoing and creative process, which must factor in conversations with and trust in relations established with the subjects of research. Furthermore, and above all, these terms of consent must consider children’s decision-making capacities in what concerns their participation in research.

All of these documents were sent via the digital messaging app WhatsApp, including the accompanying text and the address to which drawings and recordings should be sent. They were sent to various contacts in Imperatriz, as well as schools, groups of mothers, work colleagues, groups of professors of the Universidade Federal do Maranhão (UFMA), and friends with children in the relevant age group. However, since social media knows no boundaries, I started to receive audio recordings and drawings from municipalities that neighbour Imperatriz. Within this wider pool of material, I decided to widen my research to include the whole of the state of Maranhão. I furthermore started to receive messages from mothers, fathers, uncles, and godmothers asking that children over the age of 7 take part in the research, since they showed an interest and asked to take part. With these appeals, I again redefined my parameters to include children from 3 to 11 years of age.

What can we learn from this? The boredom of isolation, parental desire for their children to take part, to do something, to distract them, to see them as participating subjects in scientific research, proud of their drawings and their knowledge. Furthermore, children’s desire to also take part and to reveal “their experience”, as Pedro, 4 years old said: “Are you ready?”, asked his mother as she starts recording the interview. He responds: “Yes! With my experience” (Pedro, 4, Imperatriz).

For anthropology, where ethnography, along with its closest ally, participant observation, is the method par excellence, it is difficult to think of research without the ethnographic encounter between researcher and the subjects of the research within a defined and circumscribed space that we call the field. It is a delicate matter to carry out research without ever having seen one’s interlocutors up close, in which data is produced through a relationship established at a distance, relying on the mediation of social technologies.

Yet, as argued by Toren (Regitano, 2019), what characterizes the ethnographic experience is the nature of analysis. In this research, contact and interactions with the subjects of the research were established at a distance, and negotiations carried out in the field - such as those which make decisions on delicate ethical matters - had to transform from the conventional position of “being accepted by the natives” into a range of documents, terms of consent and assent to safeguard researcher and interlocutors, since the meanders of research could not be negotiated by shaking hands, eye to eye, sharing cups of coffee, sincere smiles and hugs, the kindness and gifts which in loco experiences afford us. However, as I will show below, virtual relations can also generate gifts.

The impossibility of carrying out participant observation turned parents into researchers, and my disciplined gaze (Oliveira, 1998) was replaced with orientations from parents who managed phone devices and conducted short interviews with the children, digitalized the drawings and sent them to the address that I indicated. Thus, the parents responsible for the children became my mediators, my eyes in the field. At the end, I wondered who the interviewers in this research were: was it I, who produced the script, or parents, who, with this script in hand, in their own way conducted the interview?

However, as always in anthropology, mediators generate noise and interferences in communication. There they were: mimicking to children during interviews, passing on information as “cheat sheets”, with overt smiles after their children produced clever or naïve answers, correcting the pronunciation of their names, saying “that’s all isn’t it?”, if their imaginations started to waiver from the original script. They even produced short texts with children, to be read by them - perceptibly so - in the recordings. If intermediaries have always added complexity to research (Evans-Pritchard, 1972), imagine when these intermediaries are the parents of our interlocutors!

Mother: “. . . how does someone catch Coronavirus?”.

Vicente: “When you don’t wear masks and send it”.

Mother: “OK. And what can you do to not catch Coronavirus?”.

Vicente: “Wear a mask”.

Mother: “And what else? There’s something else I’m always telling you to do, what is it?”.

Vicente: “Chores?”.

Mother: “No!” [tone of disapproval].

[Silence].

Vicente: “To stay home”.

Mother: “Yes. And something else. Look...” [we hear a noise, probably rubbing her hands together].

Vicente: “Was hour hands”.

(Vicente, 4, Imperatriz)

Father: “What do we do to not catch Coronavirus?”.

Guilherme: “Rubbing alcohol”.

Father: “Rubbing alcohol and what else?”.

Guilherme: “Water”.

Father: “Water and what else?”.

Guilherme: “Oranges”.

Father: “Oranges?”.

Guilherme: “Yes, because you told us to eat oranges right?”.

[Recording interrupted].

(Guilherme, 4, Imperatriz)

Mother: “And that people can catch Coronavirus, which people? Do you know which people can catch Coronavirus?”.

Vicente: “Grannies... and... normal people…A rabbit...”.

Mother: “Ok, right?”.

(Vicente, 4, Imperatriz).

Now, it does not matter if the researcher is in the field or miles away, data are always fictitious, forged (Clifford, 2002) and third-hand, whether we have mediators or not. Reality is like a text that needs to be interpreted and understood. For Sahlins (2003), whatever one thinks, ethnographic reality cannot be replaced by its understanding. From the early days of ethnography we inherited from ethnographic realism claims that “I was there” as proof of the researcher’s faithfulness to the field and to reality, but also and above all as an obsessive means to seek out ethnographic authority (Clifford, 2002). Perhaps this is the lot of those who carry out fieldwork, not just of anthropologists, since it was enough to turn mothers into interviewers who solicit recordings to receive pictures of children producing or holding their drawings, as well as image recordings of interviews, as if to prove that they were all, in fact, there.

Ever since it was recognized that children are important social actors in their cultures, making them subjects in research whose point of view guides our activities, childhood studies began to debate a number of ethical and methodological impasses. This is because the documents that inform ethics in research6 take quantitative research as their standard, particularly research in the health sciences - the subjects of which are patients rather than interlocutors. Through their “ethics committees” they seek out projects with self-contained methodological outlines. The participation of children must hence be strictly laid out, which excludes the possibility of building research in the field, within the relationship between researcher and subject, a basic condition of ethnography.

Thus, negotiations between a researcher and the subjects of her research carried out in the field, and the right of the latter to take part in, and construct, data along with the former, vanish. These documents render children incapable, and fail to recognize their potential.

In a reflection on the ethical dilemmas of research with children via the tensions between their right to participate and their right to be protected, Cunha (2017) raises issue with the use of terms of consent and assent in the field, emphasizing the importance of time spent in the field for the construction of relations of trust, on the need to use language taken from children’s universe, and in defence of ethnography as the most adequate method for research with children. The author assesses how research with children cannot be planned in a closed way, established a priori, and must always count on the imponderables.

In what pertains to this research, in the absence of negotiations that could be carried out in the field, terms of assent for parents and children and the FITC were fundamental. In research I carried out with the Capuxu people (Sousa, 2017a, 2017b), children and their parents were offended when I suggested I might replace their names for fictitious ones. Every case should thus be evaluated with care, taking into account the particularities of research and the degree of vulnerability of the subjects involved, whether adults or children. There are research contexts that not only allow for the use of photographs, drawings and real names, but actually favour it.

In Brazil, where children are considered to be vulnerable, research must first be approved in ethics committees. Barbosa (2014) argues that this puts anthropological research projects and the legislation in conflict, since the latter is equivocal in three aspects: a) it considers children to be vulnerable, ignoring their participation and protagonism; b) opposes the ethnographic method, since it demands a defined methodology prior to the start of fieldwork; c) restricts the registration and publication of images of children and anything produced by them - while we, anthropologists, want to ensure the participation of children and give them the right to have their images, names, and intellectual contributions published.

One way out would be to demand that ethics committees adopt a more contemporary view of children as right-bearing subjects, protagonists with social agency. We must ensure that ethnographic or participative research with children be ethical, of course, but it cannot be impossible unless it excludes the citizenship of the research subjects or the protagonism of children.

Addressing the restricted conception of science assumed by ethics committees, Barbosa (2014) stresses that, by demanding methodologies defined prior to the start of fieldwork, the tools of which are evaluated beforehand, as are interview or observation scripts, not to mention the very limits of the population that can be studied, these committees are inattentive to the fact that data are fabricated and their fabrication must adapt to every field situation through constant negotiations between researcher and children.

Among other things, Resolução n. 196 (1996) emphasised the non-coercion of children in research. So what is the place of children in research in the human sciences? How do we consider that children are able to understand the aims of research, to take part in it, but that they cannot decide on their participation (Francisco & Bittencourt, 2014)? The contradiction inherent in the documents referred to above concerns the notion of autonomy, so dear to an anthropology for which the child is able to understand and answer for him- or herself.

Children are not subjects about which we produce research, but who produce research with us (Francisco & Bittencourt, 2014). The relationship is not, therefore, one in which we obtain data, but wherein we construct data and realities together. If ethics committees understood this, and produced the documents that regulate them accordingly, they might understand the difference between research on human beings, research with human beings, and research for human beings (Oliveira, 2004).

For Alderson (2005), there are two arguments that belie the participation of children in research: a) the belief that data obtained with children is untrustworthy; b) the idea that children should not take part in research, given their vulnerability and the possibility of them being exploited by researchers. The possibility that children might produce knowledge of themselves and their social action was hence denied. The author claims that “recognizing children as the subjects rather than objects of research requires accepting that they can ‘speak’ in their own names and report valid visions and experiences” (Alderson, 2005, p. 423, own translation).

In research-at-a-distance, in which negotiations in the field become impossible, instruments such as the term of assent and the FITC gain importance, since they serve as a guide for parents, children and researcher. In this case, along with these instruments, I made use of another signed by the parents authorizing the publication of only the first name and ages of their children.

Considering that I obtained information by children from all over the state of Maranhão, I chose to identify them only by their given name and age. The only exception is the Indigenous child, whose given name would make her easily identifiable, and I decided to call her Guajajara, which she uses as her surname.

I am critical of the terms referred to above, and even confess to having never used them in prior research, where the relationships I established seems to me to be sufficient for negotiating participation and deciding alongside my interlocutors how they were to appear in texts. In this case, however, in which research involved people I did not know, use of the terms seemed to me to be the right decision, despite sharing Fonseca’s opinion:

If the aim of the anthropologist is, precisely, to reveal the logic implicit in facts, to speak of the “imponderability” of the place, to somehow gain access to the “unconscious” in cultural practices, how can we predict how our informants imagine all of the consequences of their informed consent? (Fonseca, 2010, p. 214, own translation).

The short interviews: “Will it be on the news?”

Rhillary’s (8, Imperatriz) grandmother had sent a recording of the short interview conducted with her mother and an explanation of the drawings. Through her grandmother’s mobile phone, Rhillary sent me a recording asking: “will it be on the news? I won’t miss the news for anything today”. I explained Rhillary that the interview was not for the news, but for university research. In her recorded reply, she seemed disappointed, but soon started to talk of the Coronavirus and forgot.

I have elsewhere criticized the use of interviews with children (Sousa, 2015) and argued for informal conversations as an important tool for researchers who study children. The restlessness typical of children was one of the reasons I was wary of interviews. They stray far too much, although adults are liable to do so as well. Furthermore, interviews excluded those very young children from participating, those whose language is not yet established. While interview is an important ethnographic technique, it is not in general useful with children because of their difficulty in narrating the world with words (Faria et al., 2005; Kramer & Leite, 1996; Sousa, 2015). Thus, always doing research through participant observation, I never saw the interview as the most useful technique for gaining access to the child’s point of view.

During my career with children, I have always believed in the creative potential of informal conversations, wherever possible or alongside direct or participant observation, as a means for “being there”. At the same time, the impersonal nature of interviews, the very formality of the term, of the digital device intervening between us, the impossibility of moving away, of distancing from the device because of the reach of the microphone, ultimately transfixed children. Informal conversations, in contrast, allow for movement: free from the constraints of recording technology, we could talk while on the way to anywhere, or sitting down on the curb next to the house. In the present research, the fact that children were interviewed by their parents was fundamental, since the degree of intimacy between them left children at ease and conversations flowed naturally.

Being at home, in their comfort zone, children felt safe, unlike in interviews conducted in prisons (Ferreira, 2020), psychologists’ clinic (Mueller, 2019) and schools (Müller & Dutra, 2018).

For the first time, I trod the opposite path to that which I was familiar with in my research: this time, informal conversations were replaced by interviews with semi-structured scripts. Occasionally, a degree of informality came through in children’s recordings. Hugs and handshakes were replaced by terms of consent, assent, etc. At the end of an interview heard over the phone, much to the researcher’s surprise, an unexpected “Kisses, love you”. A gift in the times of research far from the warm hug of children.

The production of data that results from the encounter of researcher and subjects in the field is no less complex. The anthropologist is often called upon to mediate conflicts, witness insults, find solutions to ethical impasses. At a distance, problems are not of the same order, but they nonetheless exist. As I listened to the recordings, I overheard parents and siblings interfering in the interviews, with silent suggestions, mimicry, censuring tones of voice regarding something they deemed mistaken. I could infer previously prepared texts to be read by children, while children from the same family would copy their siblings’ speech, as they were interviewed in front of each other.

Further noises or impasses were created. I had to ask mothers to transcribe the speech of very young children, whose speech in recordings or videos I could not understand. Some mothers, attentive to their young child’s diction, would send the recordings and ask: “do you need subtitles?”, “do you want me to translate?”, “can you understand?”. Interviews and videos were unexpectedly interrupted when distracted parents pressed the wrong button, or because, unsuspecting, someone talked over the interview - or, even, when a child called out a trick or a ruse of their parents.

Thus, the complexity of listening (Oliveira, 1998) is not limited by being in the field. Interviews are always complex, even when we are not the ones conducting it. We always find subtle niceties in ways of making interlocutors return to the theme of the interview, as well as interruptions, silences, inaudible tracts due to a tearful voice, out of excessive emotion or fear - not to mention gaps in communication that occur whether we are face-to-face with subjects or miles away.

My ear, trained by a career in the social sciences, framed by an eye that observes everything, needed to be taught all over again, to be resignifed. Indeed, as Oliveira (1998) claims, seeing and listening must be in tune in order to ensure observation. At the end of our anthropological training, our eyes become disciplined by theory, and out ear becomes prepared to eliminate noise.

In this research, I listened to interviews whose scripts I had authored, and turned my gaze to children’s drawings. This is how my keen anthropological nature gave rise to an ethnography in the midst of quarantine, preventing social facts from being lost in the field in the absence of a person who could register and transform them into ethnographic facts.

Drawings about the Coronavirus

It’s very small, but I’m going to draw him.

(Robert, 3, Buriticupu)

Ever since Bateson and Mead (1942), drawing has been seen to be a legitimate research tool, particularly in anthropology. Research on children in Brazil has made use of it, aiming to reveal a form of expressing symbolic production in infancy, and it has often been described in various articles on the most varied themes and in different contexts. This plurality of contexts, situations, and objects of analyses have made evident the power of the use of drawings as a research tool, capable of being adapted to the most distinct contexts. The near-universal enthusiasm of children for drawings lends further support to its use by anthropology.

In contrast to other contexts, in the present research drawings were not used as a means to create a proximity between children and researcher, to weave new relations, eliciting socialization. Drawings were used to access the point of view of children, as something that can be produced and obtained without the physical presence of the researcher, with the aid of digital technology.

Important names in childhood studies all have used the production of drawing as a technique. In a wider context, we have Bateson and Mead (1942), Mead (1963, 1985), Toren (1993) and Sarmento (2011). In Brazil, Cohn (2006, 2008), Tassinari (2015, 2016), Pires (2007, 2009), Sousa (2017a, 2017b, 2019), Müller and Dutra (2018), and Gobbi (2012) have focused on drawings as an important research tool for accessing children’s narratives. Important data on social organization can be accessed through them, as can the experiences and representations of subjects, elements that refer to the depths of social life, and not only to the social life of children.

We are increasingly attentive to drawing as a technique, to its uses and the production of data through it, as well as of its limitations. We also seek to deconstruct certain ideas surrounding the use of drawings, such as: a) its reduction to mere artifice of interaction between researcher and interlocutors; b) the usual inability of social scientists to deal with drawings; c) the failure to recognize that the technique can be efficient in the production of data (Sousa & Pires, 2021).

I stress the efficacy of the technique of eliciting drawings as a primordial means for unveiling a given reality, or approaching a specific object, which would not have been otherwise attained. The use of drawings in the production of data furthermore concerns the recognition of the agency and autonomy of children in conceiving of themselves (Sousa, 2015).

In research on children in Manu, Mead (1985) made use of participant observation alongside the analysis of drawings produced by children, providing them with the means to draw without determining how they should draw - taking care that adults not interfere with them: “I understood that this system was the closest to normal teaching that I could apply, preventing adults from drawing, since this would have modified the terms of the investigation” (Mead, 1985, p. 211, own translation).

Toren (1993) used drawings as research tool to capture children’s perceptions of hierarchy in Fiji. During her research, she would set children apart so that one’s drawing would not have an influence on that of another. Thus, while Mead was concerned with the influence of adults over children’s drawings, Toren was concerned with one child influencing another. After their drawing was finished, children would provide a statement about them.

Toren recently described her experience with drawings:

I was not trying to discover, shall we say, the development of their perspective. I had no idea of what sort of end of development they’d achieve, I was using drawing absolutely to show which ideas children had of the way things are. (Regitano, 2019, p. 296, own translation).

Toren points to the advantages of using the technique of drawing as a way of making children at ease. As she says: “If you want a child to talk, it’s much easier to be able to say ‘wow, that’s a great drawing, who is this? Tell me about it’. And, naturally, they’ll tell you everything about all things” (Regitano, 2019, p. 296, own translation).

Toren (1993) argues that we should not interpret drawings in themselves, but use them as a means to access interlocutors and their narratives. I believe that, more than being a means to gain access to children, drawing provide a means toward point of view of children, their representations and readings of the world.

Analyses of drawing should take place according to what is said by children and the meanings they themselves attribute to it, which is why I asked children to explain their drawing by audio recording after completing them. After all, “drawings that are useful for anthropological research are, without doubt, those in which children take their time in commentary. Unlike psychologists, anthropologists are not trained to infer any conclusion from a drawing” (Pires, 2007, p. 52, own translation).

In general, there are three types of drawings: free, thematic, and controlled thematic. Free drawings are those without any a priori theme, in which children themselves decide what to draw, individually or collectively. Although we call this technique spontaneous or free drawing, I agree with Mèredieu (2017) that it is, first of all, we adults who provide the instruments for children to draw, and it is we who decide on the importance of drawing to our research. Mèredieu (2017) also accepts the undeniable influence of the adult world on that of children, so that there are no children’s drawings free of any influence, as Mead (1963, 1985) and Toren (1993) propose.

Conversations with children about what they have drawn are essential, and researchers should have recourse to orality wherever possible (Sousa & Pires, 2021; Pires, 2007; Toren, 1993; Gobbi, 2012; Regitano, 2019). James et al. (1998) agree that the efficacy of the technique of drawing is potentialized insofar as drawings are later discussed.

In a number of situations during this research, what children said in audios or even video recordings became evident through drawings. In this way, in contrast to what usually happens when drawings are used as a complement to other techniques, namely direct observation, drawings and audios complemented each other. There was no superimposition of one technique on another, both were equally important. We must, after all, recognize the productivity of drawings as a legitimate tool for anthropological research, and its empirical and theoretical yield cannot be denied.

Where the drawings are produced, and the circumstance in which they are made must also be considered (Sousa & Pires, 2021). In this way, the elaboration of drawings at home, in children’s zones of comfort, with the guidance of their parents or brothers, may have played a part in leaving children at ease to talk about the Coronavirus without concerns. Judging by the videos and photographs we received, children were usually at children’s chairs meant for schoolwork, coffee tables or their parents’ desks. One child made the Coronavirus in a balloon, the mother filming it all while talking to them. In video recording, children are casual, drawing and conversing, shedding light on the background to the relations in the household and on how the drawings were produced.

As I have mentioned previously, I was not able to follow closely the production of drawing, as favoured by childhood studies, despite being aware of the importance of accompanying how drawings are made and of speaking with children as they are making them. However, I believe that the absence of a researcher, replaced by parents, may have left children more at ease, and that it was actually an advantage in the research conditions available. To make up for my absence during the making of the drawings and the impossibility of speaking with children while they were being made, I asked for explanatory audio recording which children delivered with great skill, precisely, perhaps, because they were not face to face with their interviewer; they knew, after all, that their parents were the mediators.

Another factor to be taken into account is that images sent via WhatsApp lose some of their quality, and parents are not, in general, familiar with digitalizing documents and converting them into Portable Document Format (PDF). They hence sent me pictures of the drawings. I carefully asked them to digitalize the drawings, so that I could have them in better quality, often indicating the app they could use to this end. Parents always attended to my solicitations.

I would thus reiterate that the help of parents was essential, making this research possible. They functioned as research assistants of a sort, conducting the process on site as I proceeded at a distance, trying to minimize the impacts of the impossibility of using the most important anthropological research method: direct and participant observation.

I am aware that drawings may also have been influenced by parents, and spent time speaking to each one of them to explain the importance of allowing their children to speak for themselves, that they depict the Coronavirus in their own way, through their own perceptions and experiences, by means of interviews and drawings.

Yet, as Berreman (1998) observes, the field and its subjects have always held sway over our impressions. Despite my plea, when I asked a mother if she could ask 4-year-old Vicente what was the slightly out of place blue blotch in his drawing, which I was unable to make out, she answered me, through an embarrassed chuckle, not unlike that of a child who was caught joking with a friend: “it was his dad who made it!”. This is how I found out that, if we are unable to control the impressions of our interlocutors in the field (Sousa, 2015), the matter is much worse at a distance!

Of all of the methodological limitations of distance, I regret that I had to use the drawings and the explanations of them without having followed their fabrication, as defended by Pires (2007, 2009), Sousa and Pires (2021), Toren (1993), and Mead (1963, 1985). I am aware that these were not, by any means, ideal research conditions, but this is the route I chose to follow and to which I remained committed. I did not want the passage of time, the events and isolation, to distance children from the phenomenon of Covid-19. I did not want their representations of what was going on to remain unrecorded in the present, and hence unanalysed. In a sort of return to our origins, I felt like evolutionists accused of butterfly collecting who believed that they needed to record primitive societies quickly, before they became extinct, before they lost their object of study. Lacking any sentimental pessimism (Sahlins, 1997), I feared that, once social distancing was over and parents and children resumed their routine, the data I needed would no longer be available. The realization that it was urgent to register this moment took precedence over my inability to conduct research at a distance.

During this process I discovered that it is today possible to carry out armchair research without thereby being distant - in contrast to the early days of anthropology. Although I never left my house while conducting research, I became involved in it day and night, in dialogue with the field, sometimes settling doubts with parents, other times receiving material and systematizing, saving, classifying, and analysing it. The messaging app constantly beeped, from Sunday to Sunday, because when we do research at a distance, much as when we are in the field, phenomena and their repercussions, questionings and the participation of our subjects can occur anytime.

Along with Toren and Mead, I uphold the view that the elaboration of drawings should be accompanied by the researcher, and that short conversations about the drawings are always enlightening. I also agree that it would be important for children from the same family to draw at a distance from each other, to prevent one’s drawing from interfering in the other’s (Toren, 1993; Mead, 1963, 1985). The same could be said of the short interviews sent to me as audio recordings; since the questions are the same, when one child overhears the other’s answers, they tend to copy part of it, seeing it as correct or more appropriate, particularly if the first respondent is the elder and more articulate child. I could not control any of this in the exceptional conditions of a research in which researcher and interlocutors where isolated in their own homes.

Yet it brings me some relief to say that I have never believed there to be any sort of research with children in which the results do not suffer some sort of interference from the adult “universe”, considering that children and adults share in the same universe. This is why, during this research, I was able to assuage myself of any exaggerated concern over the influence of adults or other children in the participation of young children in research. These influences mattered little to me insofar as these influences are part of children’s realities, and that they function to ensure that information reaches them in a certain way. What interested me in all of this is how they appropriated it, what they chose to narrate, through drawings or recordings, and what meaning they conferred upon it.

This is how I was able to discover, in an amusing anecdote, some of the strategies used by parents, who had certain information, to mould them in a way that children would obey their orders:

Mother: “Right. What happens when someone catches Coronavirus?”.

Lina: “They get ill, and those who don’t eat their greens will die, those who eat them won’t”.

Mother: “What can we do to avoid catching Coronavirus?”.

Lina: “Eat a lot of greens”.

Mother: “What else?”.

Lina: “And all the food on our plates”.

(Lina, 4, São Luís).

Jayle [explaining the drawing]: “This one here is the Coronavirus. And, like, it can’t chew its nails, because it’s a Coronavirus, and it also can’t get rid of this here, look, the nails, this dirt that’s in it, because it’s also a Coronavirus”.

(Jayle, 6, Esperantinópolis).

I received all of the material in the time I set - including the terms of assent and FITC. After gathering, systematizing and analysing data, I began talking to parents so that they would decide if I could publish the names and ages of their children. As I mentioned above, I had elaborated a term of authorization for parents to sign so that the first name and age of their children could be published. Taking the state of Maranhão as my limits, the first name of the child and age would not be enough to identify them. By featuring only the first name of children, I dealt with two impasses: on the one hand, I ensured that children would not be identified, as demanded by ethics committees; on the other, I could ensure that children would see themselves in the texts, as protagonists, as upheld by the anthropology of children.

Final considerations

In this article I have dealt with the ethical and methodological questions that surround research on the representations of children from Maranhão about Covid-19. I raised questions concerning the conditions for composing an ethnography at a distance, without recourse to direct observation as a guide, relying on fathers and mothers as mediators.

To respond to the questions that emerged within the methodological itinerary of this experience, I organized the article along two axes. First, an ethical one, discussing the instruments used in research, such as the FITC and the terms of assent for adults and children, and raising issues around naming the children in the final text.

Second, an ethical one, divided into two sub-items. In the first I enquired into what I call short interviews, that is, conversations between parents and children recorded as audios, based on semi-structured scripts I sent to parents. In the second I focused on the elaboration of drawings as an important research tool, and on the meanings children attributed to these drawings, which were also recorded as audios that I call explanations of drawings.

This article, a detour from my reflections on the results obtained by research, hopes to contribute to a methodology of research with children, to childhood studies, and to means for writing ethnographies at a distance, or in moments of social isolation.

REFERENCES

Alderson, P. (2005). As crianças como pesquisadoras: Os efeitos dos direitos de participação sobre a metodologia de pesquisa. Educação & Sociedade, 26(91), 419-442. [ Links ]

Barbosa, M. C. S. (2014). A ética na pesquisa etnográfica com crianças: Primeiras problematizações. Práxis Educativa, 9(1), 235-245. [ Links ]

Bateson, G., & Mead, M. (1942). Balinese character: A photography analisys. New York Academy of Sciences. [ Links ]

Berreman, G. (1998). Etnografia e controle de impressões numa aldeia dos Himalaia. In A. Z. Guimarães (Org.), Desvendando máscaras sociais (2a ed., pp. 123-174). Francisco Alves. [ Links ]

Clifford, J. (1995). Dilemas de la cultura: Antropología, literatura y arte en la perspectiva posmoderna. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Clifford, J. (2002). A experiência etnográfica: Antropologia e literatura no século XX. Editora da UFRJ. [ Links ]

Código de Nuremberg. (1947). https://www.ghc.com.br/files/CODIGO%20DE%20NEURENBERG.pdf [ Links ]

Cohn, C. (2006). O desenho das crianças e o antropólogo: Reflexões a partir das crianças Mebengokré- -Xikrin. Anais da Reunião Brasileira de Antropologia. Goiânia, Brasil, 25. [ Links ]

Cohn, C. (2008). A tradução de cultura pelos Mebengokré-Xikrin da perspectiva de suas crianças. Anais da Reunião Brasileira de Antropologia. Belém, Brasil, 27. [ Links ]

Cunha, S. M. da. (2017). Pesquisa com crianças: Implicações teóricas, éticas e metodológicas. Anais do Congresso Ibero-Americano de Investigação Qualitativa de Ciências Sociais. Salamanca, Espanha, 6. [ Links ]

DaMatta, R. (1978). O ofício do etnólogo ou como ter “Anthropological Blues”. In E. de O. Nunes (Org.), A aventura sociológica: Objetividade, paixão, improviso e método na pesquisa social (pp. 23-35). Zahar. [ Links ]

Declaração de Helsinque. (1964). https://www.ufrgs.br/bioetica/helsin1.htm [ Links ]

Delalande, J. (2001). La cour de récréation: Contribution à une anthropologie de l’enfance (Collection Le Sens Social). Presses Universitaires de Rennes. [ Links ]

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1972). Trabalho de campo e tradição empírica. In Antropologia social (pp. 104-136). Edições 70. [ Links ]

Faria, A. L. G., Demartini, Z. B. F., & Prado, P. D. (Orgs.). (2005). Por uma cultura da infância: Metodologia de pesquisa com crianças. Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Favret-Saada, J. (2005). “Ser afetado”. Cadernos de Campo, 13(13), 155-161. [ Links ]

Ferreira, N. G. de B. (2020). Maternidade e crianças encarceradas: Etnografando o dia de domingo do Presídio Maria Júlia Maranhão (João Pessoa-PB) [Dissertação de Mestrado]. Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia. [ Links ]

Fonseca, C. (2010). O anonimato e o texto etnográfico: Dilemas éticos e políticos da etnografia “em casa”. In P. Schuch, M. S. Vieira, & R. Peters (Orgs.), Ética e regulamentação na pesquisa antropológica (pp. 205-226). Letras Livres/UnB. [ Links ]

Francisco, D. J., & Bittencourt, I. (2014). Ética em pesquisa com crianças: Problematizações sobre termo de assentimento. Anais do Simpósio Luso-Brasileiro em estudos da Criança - Pesquisa com crianças: Desafios éticos e metodológicos. Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2. [ Links ]

Geertz, C. (1989). A interpretação das culturas. Editora Aplicada. [ Links ]

Geertz, C. (2005). Estar lá: A antropologia no cenário da escrita. In Obras e vidas: O antropólogo como autor (pp. 11-39). Editora da UFRJ. [ Links ]

Gobbi, M. (2012). Desenhos e fotografias: Marcas sociais de infâncias. Educar em Revista, (43), 135-147. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/er/n43/n43a10.pdf [ Links ]

Guber, R. (2005). El salvaje metropolitano: Reconstrucción del conocimiento social en el trabajo de campo. Paidós. [ Links ]

James, A., Jenks, C., & Prout, A. (1998). Theorising childhood. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Kramer, S., & Leite, M. I. (Orgs.). (1996). Infância: Fios e desafios da pesquisa (Prática Pedagógica, 3a ed.). Papirus. [ Links ]

Magnani, J. G. C. (2002). De perto e de dentro: Notas para uma etnografia urbana. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 17(49), 11-29. [ Links ]

Malinowski, B. (1984). Argonautas do Pacífico Ocidental (Os Pensadores). Abril Cultural. [ Links ]

Mead, M. (1963). Growing up in New Guinea. Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Mead, M. (1985). Educación y cultura en Nueva Guinea. Paidós Studio. [ Links ]

Mèredieu, F. de. (2017). O desenho infantil (14a ed.). Cultrix. [ Links ]

Mueller, B. (2019). “Tiro de bola”: Uma etnografia de crianças, emoções e conflitos no Brasil e no México [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade Federal Fluminense, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia. [ Links ]

Müller, F., & Dutra, C. P. R. (2018). Percursos urbanos: (Im)possibilidades de crianças em Brasília e Florianópolis. Educação em Foco, 23(3), 799-818. https://periodicos.ufjf.br/index.php/edufoco/article/view/20103 [ Links ]

Oliveira, L. R. C. de. (2004). Pesquisa em versus pesquisa com seres humanos. In C. Victora, R. G. Oliven, M. E. Maciel, & A. P. Oro (Orgs.), Antropologia e ética: O debate atual no Brasil (pp. 2-16). Editora da UFF. [ Links ]

Oliveira, R. C. de. (1998). O trabalho do antropólogo. Unesp; Paralelo 15. [ Links ]

Pires, F. (2007). Ser adulta e pesquisar crianças: Explorando possibilidades metodológicas na pesquisa antropológica. Revista de Antropologia, 50(1), 225-270. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-77012007000100006 [ Links ]

Pires, F. (2009). Quem tem medo de mal-assombro? Etnográfica, 13(2), 291-312. https://journals.openedition.org/etnografica/ [ Links ]

Regitano, A. de P. & Toren, C. (2019). How we become who we are. Interview with Christina Toren. PROA - Revista de Antropologia e Arte, 9(1), 295-304. https://ojs.ifch.unicamp.br/index.php/proa/article/view/3594 [ Links ]

Resolução n. 196, de 10 de outubro de 1996. (1996). Aprova diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/1996/res0196_10_10_1996.html [ Links ]

Resolução n. 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. (2012). Aprova diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2012/Reso466.pdf [ Links ]

Sahlins, M. (1997). O “pessimismo sentimental” e a experiência etnográfica: Por que a cultura não é um “objeto” em via de extinção (Parte I). Revista Mana, 3(1), 41-73. [ Links ]

Sahlins, M. (2003). Cultura e razão prática. Jorge Zahar. [ Links ]

Sarmento, M. J. (2011). Conhecer a infância: Os desenhos das crianças como produções simbólicas. In A. J. Martins Filho, & P. D. Prado (Orgs.), Das pesquisas com crianças à complexidade da infância. Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Sousa, E. L. de. (2015). As crianças e a etnografia: Criatividade e imaginação na pesquisa de campo com crianças. Iluminuras, 16(38), 140-164. https://doi.org/10.22456/1984-1191.57434 [ Links ]

Sousa, E. L. de. (2017a). De passagem: Uma análise do fenômeno “os Meninos do Trem” da Estrada de Ferro Carajás. Relatório Final de Projeto de Pesquisa apresentado à Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico do Estado do Maranhão/Fapema, 65p. [ Links ]

Sousa, E. L. de. (2017b). Umbigos enterrados: Corpo, pessoa e identidade Capuxu através da infância (Coleção Brasil Plural/Instituto Brasil Plural). Edufsc. [ Links ]

Sousa, E. L. de. (2019). As crianças e as linhas de transmissão em São Luís: Perspectivas metodológicas de uma pesquisa sobre representações infantis. Revista Mediações, 24(2), 307-335. http://www.uel.br/revistas/uel/index.php/mediacoes/article/view/35291/pdf [ Links ]

Sousa, E. L. de, & Pires, F. F. (2020). “Vai entrar no livro?”: A participação das crianças das pesquisas de campo aos textos etnográficos. Humanidades & Inovação, 7(28), 141-158. https://revista.unitins.br/index.php/humanidadeseinovacao/article/view/2077 [ Links ]

Sousa, E. L. de, & Pires, F. F. (2021). “Entendeu ou quer que eu desenhe?”: Os desenhos na pesquisa com crianças e sua inserção nos textos antropológicos. Horizontes Antropológicos, 27(60), 61-93. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-71832021000200003 [ Links ]

Tassinari, A. M. I. (2015). Produzindo corpos ativos: A aprendizagem de crianças indígenas e agricultoras através da participação nas atividades produtivas familiares. Horizontes Antropológicos, 21(44), 141-172. https://www.scielo.br/j/ha/a/BpSTPLnKQSXmt3jJWt8LskB/?lang=pt&format=pdf [ Links ]

Tassinari, A. M. I. (2016). “A casa de farinha é a nossa escola”: Aprendizagem e cognição Galibi-Marworno. Revista de Ciências Sociais Política & Trabalho, 32(43), 65-96. https://periodicos.ufpb.br/ojs/index.php/politicaetrabalho/article/view/24748 [ Links ]

Toren, C. (1993). Making history: The significance of childhood cognition for a comparative anthropology of mind. Man, 28(3), 461-478. [ Links ]

Wagner, R. (2010). A invenção da cultura. Cosac Naify. [ Links ]

1 I heard 23 children between the ages of 3 and 11, interviewed by their fathers and/or mothers, from various municipalities in the state. All children are city-dwellers, including one Indigenous Tentehara-Guajajara child. All children interviewed attend school, though 9 do not yet know how to read and write.

2 For Geertz (1989, p. 20, own translation), “ethnography is thick description. What the ethnographer is in fact face with, . . . is a multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another, which are at once strange, irregular or inexplicit, and which he must contrive somehow to first grasp and then to render. . . . Doing ethnography is like trying to read (in the sense of ‘construct a reading of’) a manuscript - faded, full of ellipsis, suspicious emendations and tendentious commentaries”.

3 In this text I explained: “Orientations for children - for the drawings, the explanation of the drawings, or the short interviews which should be recorded by parents - can be based on the following questions: What is Coronavirus? Who do people catch Coronavirus? Who can catch it? What happens to someone who has caught it? What can we do to avoid catching Coronavirus?”.

4 In Maranhão, during the last two weeks of March 2020, schools and universities stopped having in-person events, switching to remote interactions. On April 1st school vacations were anticipated, which meant that students and staff in private schools were given collective holidays. State and municipal schools halted all activities indeterminately.

5 A similar version of this term of consent was first used by the Criança, Sociedade e Cultura [Children, Society and Culture] group from Universidade Federal da Paraíba (CRIAS/UFPB), coordinated by Professor Flávia Ferreira Pires during research in the city of Catinguera, Paraíba.

6 I am specifically referring to Resolução n. 196 (1996), Resolução n. 466 (2012), the Nuremberg Code (Código de Nuremberg, 1947), and the Declaration of Helsinki (Declaração de Helsinque, 1964).

Data availability statementThe data underlying the research text are reported in the article.

How to cite this article Sousa, E. L. de. (2022). Ethnography with children in times of pandemic: An ethical and methodological reflection. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 52, Artigo e09122. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053149122

Acknowledgments

The research which led to this article was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes), Funding Code 001, and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico do Maranhão (Fapema). I also thank Fernanda Müller for carefully reading this manuscript.

Received: November 01, 2021; Accepted: May 13, 2022

texto en

texto en