Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 0100-1574versão On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.52 São Paulo 2022 Epub 30-Mar-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053148714

HIGHER EDUCATION, PROFESSIONS, WORK

LABOR REFORM AND TEACHING WORK IN PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION IN BRAZIL

IFundação Joaquim Nabuco (Fundaj), Recife (PE), Brasil; darcilene.gomes@fundaj.gov.br

IIUniversidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife (PE), Brasil; sidartha.soria@ufpe.br

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the potential impacts of the latest Labor Reform and specific measures taken by the sector, such as the progress in Distance Learning (EaD), on the labor universe of professors acting in private higher education in Brazil. Law n. 13,467/2017 was passed by the Temer Administration on the grounds of creating “legal certainty” and modernizing labor relations. In this regard, we intend to analyze the turnover of professors in the databases composed of administrative records of the Ministry of Economy in order to verify whether, beyond the news of specific cases, the sector as a whole is already experiencing noticeable changes in their employment levels, in the volume of dismissals and hiring, and whether specific provisions of the Labor Reform are already been complied with.

Key words: LABOUR MARKET; TEACHING PROFESSION; HIGHER EDUCATION; PRIVATE EDUCATION

O objetivo deste trabalho é investigar possíveis impactos, sobre o universo laboral dos docentes que atuam no ensino superior privado brasileiro, da mais recente reforma trabalhista e de medidas específicas da categoria, como o avanço da educação a distância (EaD). A Lei n. 13.467/2017 foi aprovada no governo de Michel Temer, sob a justificativa de gerar “segurança jurídica” e modernizar as relações trabalhistas. Nesse sentido, pretende-se analisar a movimentação de professores nas bases compostas por registros administrativos do Ministério da Economia, a fim de averiguar se, para além da notícia de casos particulares, a categoria como um todo já experimenta alterações sensíveis em seus níveis de emprego, no volume de demissões e admissões, e se há introdução de dispositivos próprios da Reforma Trabalhista.

Palavras-Chave: MERCADO DE TRABALHO; DOCENTE; ENSINO SUPERIOR; ENSINO PRIVADO

El objetivo de este trabajo es investigar los posibles impactos en el universo laboral de los docentes que trabajan en la educación superior privada brasileña, la reforma laboral más reciente y las medidas específicas de la categoría, como el avance de la educación a distancia (EaD). La Lei n. 13.467/2017 fue aprobada en el gobierno de Michel Temer, con el argumento de generar “seguridad jurídica” y modernizar las relaciones laborales. En este sentido, se pretende analizar el movimiento de docentes en las bases compuestas por registros administrativos del Ministerio de Economía, con el fin de verificar si, además de las noticias de casos particulares, la categoría en su conjunto ya experimenta cambios sensibles en sus niveles de empleo, en el volumen de despidos y admisiones, y si hay introducción de dispositivos propios de la Reforma Laboral.

Palabras-clave: MERCADO DE TRABAJO; PROFESIÓN DOCENTE; ENSEÑANZA SUPERIOR; ENSEÑANZA PRIVADA

Cet article cherche à évaluer les impacts que la réforme du travail la plus récente ainsi que certaines mesures spécifiques, telles que l’essor de l’enseignement à distance (EaD), ont pu avoir sur le travail des enseignants de l’enseignement supérieur privé au Brésil. La loi n. 13.467/2017 a été approuvée par le gouvernement de Michel Temer, sous la justification qu’elle contribuerait à une “sécurité juridique” et à moderniser les relations de travail. Ce que l’on propose donc ici est d’analyser les mouvements des enseignants à partir de données provenant des registres administratifs du Ministère de l’Economie, afin de vérifier si, au-delà des cas particuliers relevés, l’ensemble de la catégorie subit déjà des changements sensibles concernant ses niveaux d’emploi, le volume de licenciements et d’admissions, et si des dispositifs propres à la Réforme du Travail ont été introduits.

Key words: MARCHÉ DU TRAVAIL; PROFESSION D’ENSEIGNANT; ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR; ENSEIGNEMENT PRIVÉ

The contours of the current higher education system in Brazil were defined by the University Reform of 1968, which modernized and expanded public universities, based on the education-research-continuing education trio; and encouraged the expansion of private institutions, especially business ones, mostly dedicated to education. Since then, the private sector consolidated its position and is currently responsible for almost two out of three enrollments in higher education in Brazil.

This growth, however, was not linear. At some moments, the private sector even had a drop in enrollment, but since the second half of the ‘90s, the segment has been able to renew itself and succeed, initially amid the funding crisis experienced by public universities and then, already in the mid-2000s, in synchrony with the prosperity of federal public institutions.

The progress of the private business segment was never in line with the improvement in the quality of the education provided. We recognize that the debate on the quality of the educational systems is complex, but it is worth mentioning that if we take into account some indicators associated with quality (such as the score in the Exame Nacional de Desempenho dos Estudantes [National Student Performance Exam] (ENADE), the dropout rate, the student/year cost, and the student/professor relationship), as Bielschowsky (2020) did, the situation is at least disturbing (and more severe in institutions linked to the largest business groups and in EaD). Additionally, faculty hiring conditions, according to the 2018 Higher Education Census, generally on an hourly (30.1%) or part-time (42.4%) basis, and work conditions also differ from those deemed ideal (Leda, 2009; Siqueira, 2006; Sebim, 2014).

As it is known, the Labor Reform was passed in November 2017 amid a political and economic crisis and, in the first month of its effectiveness, the Brazilian press reported the dismissal of a number of professors who worked in private higher education. One of these institutions alone, Estácio de Sá, dismissed 1,200 professors at once. Also according to what was reported by newspapers and specialized websites, the dismissals occurred in other institutions or groups, such as Laureate (the press reported 470 dismissals), Universidade Metodista of São Paulo (60 dismissals), and Ser Educacional (78 professors dismissed). Moreover, many of these news articles established a direct relationship between the labor reform and the dismissals (Souza, 2017; Basílio, 2017; Mendonça, 2017; Alvarenga & Trevisan, 2017).

As the Reform is fairly recent, its impacts are still being observed and assessed. In this regard, this paper aims at verifying, based on the Administrative Records of the Ministry of Economy, the turnover (hiring and termination) of workers who taught in private higher education institutions from January 2014 to December 2019. To do that, we used the Cadastro Geral de Empregados e Desempregados [General Registry of Employed and Unemployed Persons] (Caged) and the Relação Anual de Informações Sociais [Annual Corporate Information Report] (Rais). The researched population was selected based on the occupation “professores do ensino superior” (“professors”), code 234 (sub-group), of the 2002 Código Brasileiro de Ocupações [Brazilian Classification of Occupations] (CBO). For the Rais, which encompasses the public (statutory contracts and others) and private sectors, two types of institutions were selected according to the legal nature: private companies and nonprofit entities, in addition to the abovementioned occupation.

This paper is organized into three items, plus the Introduction and Final Considerations. The first expatiates on the organization of the Brazilian higher education system, pointing out the characteristics of the private segment. The second shows the main changes in labor laws and regulations brought by the reform passed in September 2017. Finally, the third item presents data about the turnover of professors who work in private higher education.

Brief History of the Evolution of the Brazilian Higher Education System

Brazilian higher education began belatedly, also compared to other Latin American countries. The first higher education courses were created in Bahia and Rio de Janeiro, at the beginning of the 19th century, in the fields of Medicine, Law, and Engineering. It was only in 1920 that an authentic university was established, the University of Rio de Janeiro, as a result of the merger of the Medical, Polytechnic, and Law Schools (Cunha, 2007).

The Brazilian university was institutionalized after the Vargas Era, when, under the administration of the Minister of Education and Health, Francisco Campos, Decree 19,851/1931 was enacted, creating the Statute of Brazilian Universities. In the ‘30s, with the emergence of University of São Paulo (1934) and University of the Federal District (1935) - the latter will be absorbed by the University of Brazil in 1939 -, the process of reorganization of the Brazilian university field began, until then focused mainly on the pulverization of isolated courses and the professional ideal (Cunha, 2007). In the subsequent twenty years, the expansion of national higher education sped up, with a significant increase in the number of enrollments and universities, happening simultaneously with the growing federalization of universities (Arruda, 2011).

The most general lines of higher education in Brazil emerge with Law 5,540/1968, which, during the dictatorial regime, creates the University Reform. One of the key purposes of the reform was to fit the university in the effort for economic development and, therefore, to base it on the principles of rationalization, efficiency, and productivity. The Law, despite limiting the university through authoritarian instruments typical of a military regime, would bring some progress, which was already being discussed even before the Coup, among which the acknowledgment of the teaching-scientific, regulatory, financial, and administrative autonomy of universities (Arruda, 2011; Sampaio, 2000).

Weber (2000) identifies other positive aspects, such as the initiative to associate education, research, and continuing education, in addition to the creation of master’s and doctoral programs. Nonetheless, the military regime favored and encouraged the expansion of private higher education (Arruda, 2011; Martins, 2009), mostly with national capital and organized according to business molds, through the indirect transfer of funds and specific policies (Carvalho, 2002; Leher, 2013). According to Martins (2009), in 1980, enrollments in the private system already represented almost 65% of total enrollments in higher education. In the subsequent years, however, the growth of the private system slowed down and the number of enrollments even dropped in some years (Sampaio, 2011), probably, among other factors, due to the Brazilian economic crisis in the ‘80s (Martins, 2009).

With the re-democratization and, later, the enactment of the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988, private higher education was reaffirmed as a field subject to exploitation by the private initiative. Additionally, article 207 of the Constitution, which provided for the autonomy of universities, accelerated the conversion of private facilities into universities, dynamics that was already been observed since the mid-‘80s (Martins, 2009; Sampaio, 2011). By “escaping” the bureaucratic control of the Federal Board of Education, private universities could define their courses and reallocate places, which enabled the segment to adapt more quickly to the demand for higher education. But, as Martins (2009, p. 24) mentions, these institutions “are a simulacrum of real universities”, as both the consolidation of the academic career of their faculty and the promotion of research is absent in the extensive majority of these institutions.

In the ‘90s, with consecutive administrations imposing a liberalizing agenda for reforming the Government, public higher education ended up being included in the tax adjustment process. On the other hand, private higher education, especially in the second half of the decade, expanded significantly (new courses, new locations, etc.), while federal public universities, for example, faced miscellaneous problems. Data are clear, the number of enrollments in private higher education grew 88% between 1990 and 2000, enrollments in private universities grew 177.3%, the number of private institutions grew 44.3% (Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Education Studies and Research [INEP], 1999, 2001).

Sampaio (2011) points out that, in addition to the transformation into universities, there was a statutory change in private educational institutions, which gradually started to assume their business character after Decree No. 2,306/1997, which required a more “market-oriented” management. The creation of university centers is another measure adopted by the Ministry of Education and Culture - MEC in the same period and that reinforces the expansion of private institutions - between 1997 and 2001, 59 private centers were created (Cunha, 2003).

It can be noticed that there is a line of continuous growth in the private segment on a large scale, which will gain new contours in the next decade after the strong entry of international groups into the country and transactions mediated by the financial market (Almeida, 2012; Oliveira, 2009).

The exhaustion of the political forces that were then engaged in the liberalizing project in effect in the ‘90s will open a new chapter about the issue of higher education in Brazil, as well as the social, political, and economic context in which it is inserted.

The resuming of investment is noteworthy in the 2000s and, as a result, the significant growth of federal universities starting in 2005. In this period, eight new universities were created, as well as the University for All Program (ProUni) (2004), directed to the private sector; and the Program to Support the Restructuring and Expansion Plans of the Brazilian Federal Universities (Reuni) (2007), which drafted the expansion of the public system (Marques & Cepeda, 2012).

Regarding the private sector of Brazilian higher education, the ProUni emerged as a concept of policy prepared within the MEC bureaucracy (Almeida, 2012), reacting to the need to regulate the requirements for tax exemptions (Haddad, 2006), to the demands of private higher educational institutions (HEIs) to deal with unfilled places and the declining number of newly-admitted students (Almeida, 2012); and taking into account the social strata excluded from higher education (Haddad, 2006). The program aimed at granting low-income students, in the form of partial or full scholarships, 10% of the places offered by private institutions. It uses tax waiver - Imposto de Renda das Pessoas Jurídicas [Corporate Income Taxes] (IRPJ), Contribuição Social sobre o Lucro Líquido [Social Contribution on Net Profits] (CSLL), Contribuição Social para Financiamento da Seguridade Social [Social Security Financing Contribution] (COFINS), and Programa de Integração Social [Social Integration Program] (PIS) - to finance these scholarships, reinforcing the historical indirect type of subsidy to private institutions (Almeida, 2012; Carvalho, 2005). The Program was institutionalized by Law N. 11,096 of January 13, 2005. According to MEC, from its creation until the second semester of 2017, the number of ProUni scholarships grew by 222.3%.

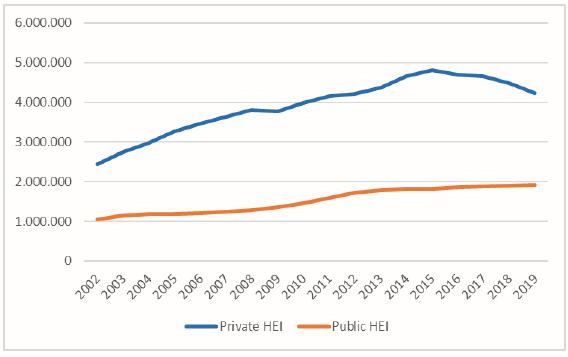

In addition to the ProUni, in 2010 the amendments to the rules for granting the Fundo de Financiamento Estudantil [Student Financing Fund] (FIES), reflected on the waiver of guarantors and on the creation of the Fundo de Garantiade Operações de Crédito Educativo [Educational Credit Guarantee Fund] (FGEDUC), boosted the growth of enrollments in the private higher education system, as shown in Table 1. Between 2002 and 2016, enrollments for classroom courses grew by 93% and the private sector was able to maintain its share of the total enrollments for classroom higher education courses, even with the expansion of the public system. From 2016 on, there has been a drop in enrollments for classroom courses in private institutions, which makes their share in the total enrollments for this type of class decline (see also Chart 1).

TABLE 1 Enrollments for classroom courses in Higher Educational Institutions, Brazil, 2002-2019

| YEAR | NO. OF ENROLLMENTS IN PRIVATE HEIS | % ENROLLMENTS IN PRIVATE INSTITUTIONS/TOTAL | NO. OF ENROLLMENTS IN PUBLIC HEIS | % ENROLLMENTS IN PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS/TOTAl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2.428.258 | 69,8 | 1.051.655 | 30,2 |

| 2003 | 2.750.652 | 70,8 | 1.136.370 | 29,2 |

| 2004 | 2.985.405 | 71,7 | 1.178.328 | 28,3 |

| 2005 | 3.260.967 | 73,2 | 1.192.189 | 26,8 |

| 2006 | 3.467.342 | 74,1 | 1.209.304 | 25,9 |

| 2007 | 3.639.413 | 74,6 | 1.240.968 | 25,4 |

| 2008 | 3.806.091 | 74,9 | 1.273.965 | 25,1 |

| 2009 | 3.764.728 | 73,6 | 1.351.168 | 26,4 |

| 2010 | 3.987.424 | 73,2 | 1.461.696 | 26,8 |

| 2011 | 4.151.371 | 72,2 | 1.595.391 | 27,8 |

| 2012 | 4.208.086 | 71,0 | 1.715.752 | 29,0 |

| 2013 | 4.374.431 | 71,1 | 1.777.974 | 28,9 |

| 2014 | 4.664.542 | 71,9 | 1.821.629 | 28,1 |

| 2015 | 4.809.793 | 72,5 | 1.823.752 | 27,5 |

| 2016 | 4.686.806 | 71,5 | 1.867.477 | 28,5 |

| 2017 | 4.649.897 | 71,2 | 1.879.784 | 28,8 |

| 2018 | 4.489.690 | 70,2 | 1.904.554 | 29,8 |

| 2019 | 4.231.071 | 68,8 | 1.922.489 | 31,2 |

Source: Inep (2020).

Source: Inep (2020).

CHART 1 Enrollments for classroom courses in Higher Educational Institutions, in-person learning only. Brazil. 2002-2019

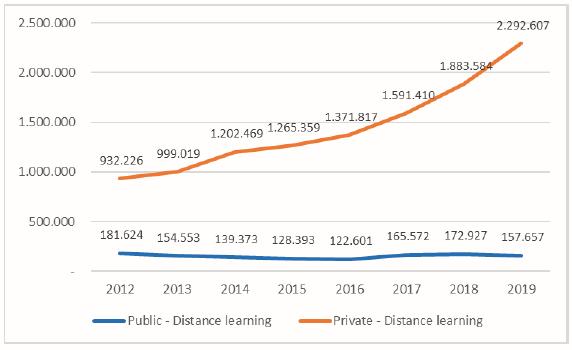

In addition to enrollments for classroom courses, the private sector also stood out with the offer of Distance Learning (EaD). Chart 2 shows that enrollments for EaD courses in private institutions continuously increased between 2012 and 2019, more than doubling this figure in less than a decade. If we add the enrollments for classroom and EaD courses, in 2019, the private segment accounted for 75.8% of the total enrollments in higher education in Brazil.

Source: Inep (2020).

CHART 2 Distance learning enrollments in higher educational institutions, Brazil, 2012-2019 (No.)

Increased competition in the private segment was also observed during the period. The mergers and acquisitions were intense as of 2007. In 2018, the ten major private groups started to account for 33,9% of the enrollments for classroom courses and 81,9% of the EaD enrollments in the sector (Bielchowsky, 2020). Bielchowsky (2020) shows that 49,1% of the students enrolled in the HEIs linked to the 10 major business groups of the sector attend courses with grades 1 and 2 in the ENADE, evidencing that the “cartelization” of private higher education does not favor quality, but the other way round. For EaD, the situation seems to be more dramatic. As an example, in 2018, 98% of the students enrolled in distance-learning courses in Kroton attended courses with grades 1 and 2 in ENADE. Additionally, dropout rates in the HEIs owned by these business groups are significant. In the same Kroton, 59,8% of the students enrolled abandoned the courses in up to two years after their admission (Bielchowsky, 2020).

According to Lavinas et al. (2017), the Student Finance Fund (FIES), when ensuring financing for about 40% of enrollments in private institutions, contributed to the appreciation of shares of the companies of the segment: “as the number of FIES students in these second-class private universities increased, the market value of the companies also increased.” According to Lavinas et al. (2017), the expenses with FIES increased from BRL1,3 billion to BRL15 billion between 2003 and 2015.

It has been recorded a significant expansion of federal public higher education during the period made feasible by the Presidential Decree 6,096/2007, which created the Reuni. Reuni was responsible for increased availability of places in federal HEIs in operation and creation of new universities. Between 2004 and 2010, 14 new federal universities were created and 123 new campus were built.1 It is also important to highlight the creation of 38 Federal Educational, Scientific, and Technological Institutes, which quickly expanded throughout the national territory and started to offer places in vocational, undergraduate, and postgraduate courses.

After this overview of the public and private university environment, we shall see now the changes in labor laws and regulations and, soon after, how they affect the teaching work relations.

Labor Reform of the Temer Administration: notes on Law 13,467/2017

On 07/13/2017 the Temer Administration approved the legal text passed by the Federal Senate - with no changes in the text approved by the Chamber of Deputies - transforming it into Law No. 13,467, which introduced significant modifications to the Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho [Consolidated Labor Laws] (CLT) of 1943. The purpose of this item is to outline the main changes brought by the reform.

According to Chahad (2017), the 2017 reform made changes to several items, namely: 1) employment contract; 2) collective bargaining agreements and union organization; 3) new types of work, and 4) Labor Court. For a preliminary overview of the changes at stake, it is enough to address the top three items.

Regarding the first item, the reform introduced modifications in the following provisions: time bank, dismissal, rest, vacation pay, pregnancy, workday, overtime work, positions and salaries plan, compensation, time at (or at the disposal of) the company, and transportation (Chahad, 2017). As it would be beyond the purpose of this paper to detail the changes in each of these provisions (which would also require describing how they existed before the law), the most significant changes will be highlighted in terms of their potential impacts on the redesign of labor and union relations (Chart 3).

CHART 3 Summary of the changes brought by Law 13,467/2017 to the employment contract

| Subject | Changes |

|---|---|

| Time bank | It is no longer negotiated only in the Collective Bargaining Agreement (ACT), and it may be agreed upon by individual agreement. |

| Dismissal | In addition to the voluntary, unfair, and fair dismissal categories, it is introduced dismissal by mutual agreement between employee and employer (payment of half notice and half of the 40% penalty on the Fundo de Garantia do Tempo de Serviço [Government Severance Indemnity Fund for Employees] (FGTS) contribution; the employee may also move up to 80% of the FGTS contribution, but loses right to unemployment benefits) |

| Vacation Pay | Through individual agreement, it will be possible to divide it into up to 3 periods, as long as one of them is at least14 calendar days. |

| Pregnancy | Pregnant and breastfeeding women are allowed to work in unhealthy environments, upon submission, by the company, of a medical certificate that ensures there is no risk to the baby or the mother. |

| Workday | It can be up to 12 daily hours (with 36 hours of rest), provided the limit of 44 weekly hours (48 hours including overtime work). |

| Overtime work | Is equivalent to 50% of the regular hour. |

| Positions and salaries plan | It can be negotiated between employers and employees without the need for ratification or registration in agreement, and it may be constantly changed. |

| Compensation | The payment of a base salary or minimum wage is no longer mandatory in cases of compensation for production, as long as provided for in the Collective Agreement. Cost allowances, meal allowance, prizes, and bonuses are compensation items but are no longer part of the salary. |

| Time at the company | Activities in the company such as resting, studying, eating, interaction among colleagues, personal hygiene, and change of uniform no longer count as working hours. |

| Transportation | The time spent to and from the workplace through any means of transportation is no longer accounted for in the workday. |

Source: Chahad (2017).

In general, what can be observed about the changes operated in the employment contract field is an expansion of the possibility for workers, individually, to negotiate devices directly with employers. Given that the legal changes seem to imply a loss of space for collective bargaining agreement mediated by the union, this would point toward a pulverization of contractual situations or bonds - what Krein et al. (2018, p. 111) call “de-standardization of the workday”.

Another observation of a more general type is that the changes listed above point out to a reduction in the costs of companies with respect to the employment bond. Changes in transportation devices, time in the company, and remuneration represent direct costs cuts for the companies - in the case of the latter, by no longer having a type of salary, such installments are removed from the basis for the calculation of labor funds, implying in loss or decrease of rights. (Cavalcante, 2017) On the other hand, overtime work can be kept at a minimum of 50% (previously, a minimum of 20% was so admitted), which would be offset by the potential and flexible enlargement of the working hours, thus serving as an indirect form of cost cutting for employers.

Regarding the second item - collective bargaining agreements and union organization -, for Chahad (2018) the changes brought by Law 13,467/2017 would follow two basic principles: the prevalence of negotiated over legislated and changes in union representation with the end of mandatory union dues. In addition, what is negotiated shall not be incorporated into the employment contract permanently - once the effective periods of rights negotiated in agreements and collective bargaining agreements expire, new negotiations shall be made.

About the third item - new types of work -, one should keep in mind that, hardly before the reform, in March 2017 Law 13,429 was sanctioned, which extended the temporary working arrangements (outsourcing) to the main activities of companies.

About the third item - new types of work -, one should keep in mind that, hardly before the reform, in March 2017 Law 13,429 was sanctioned, which extended the temporary working arrangements (outsourcing) to the main activities of companies. Law 13,467/2017, in its turn, brought the following innovations: it changed the part-time contract (it expanded from 25 to 30 hours weekly with no overtime work, or to 26 hours weekly plus 6 overtime work); it introduced the intermittent employment contract and the independent employment contract - which expressly removes its quality as of employee (art. 442-B of the CLT).

Between critics and advocates of the new labor laws and regulations, it seems to be little doubt as to its general meaning: increasing the degree of easing in labor relationships and decreasing in its costs for employers.

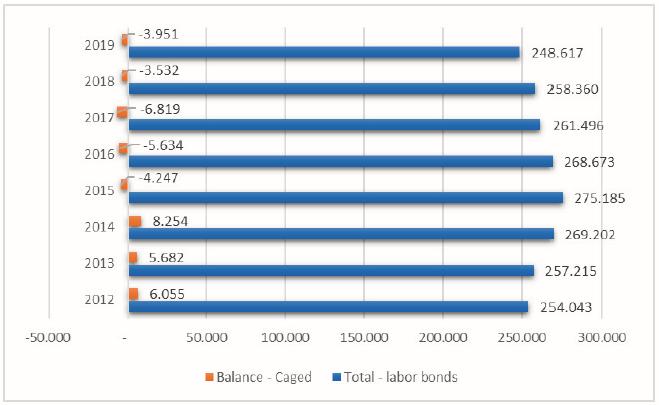

Impacts of the Labor Reform: the private higher education professors

According to the information contained in the Rais, the number of legal jobs of professors in private higher education was about 248,6 thousand2 (2019 data) and corresponded to 61,6% of the total legal jobs of professors of higher education. From this perspective, the main job market for professors in Brazil is the private sector of education, in contrast to early childhood, primary, and secondary education in which most teachers work in the public sector.

Over the last few years, data on Rais shows a drop in the number of professors working in private higher education after 2015. The Caged confirms this drop because it has been showing negative balances of positions creation year after year (Chart 4). Data on the Census of Higher Education show a similar tendency; between 2015 and 2019, the number of professors on duties drops 6% (INEP, 2015, 2019). It is relevant to mention that these numbers have a declaratory nature (the educational institutions are the informants) and the legal jobs may vary depending on the information provided. It is important, in this case, to observe the tendency indicated by data.

Source: MTP (2021).

CHART 4 Number of labor bonds on 31-Dez and annual balances, professors in private institutions, Brazil (2012 to 2019)

The Southeast, South, and Northeast regions concentrated the largest number of professors in all years analyzed, with gains in participation in the Northeast and, to a lesser extent, in the South and North and a loss in the participation of the Southeast and Midwest. In the Northeast region, the number of private higher education professors grew by 7.1% between 2014 and 2019. The North had the smallest positive variation (1.5%). The other regions lost positions, the Midwest fell by 16.2%, Southeast by 12.9%, and the South by 4.4%. The Southeast, however, even with a drop in participation, continues to focus on almost half of university professors in private higher education.

TABLE 3 Regional distribution of professors working in private higher education, 2014-2019 (%)

| NATURAL REGION | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NORTH | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| NORTHEAST | 16.3 | 16.9 | 17.5 | 17.9 | 18.9 | 18.9 |

| SOUTHEAST | 51.3 | 50.9 | 50.2 | 50.0 | 48.7 | 48.4 |

| SOUTH | 18.6 | 18.9 | 19.1 | 19.1 | 19.3 | 19.3 |

| MIDWEST | 9.1 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 8.3 |

| TOTAL | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Source: MTP (2021).

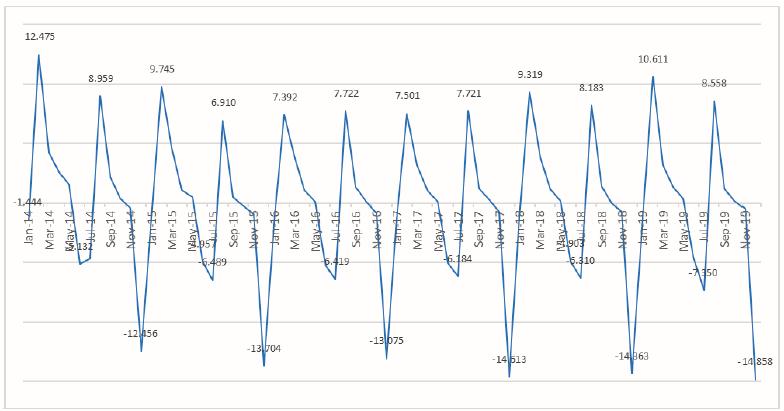

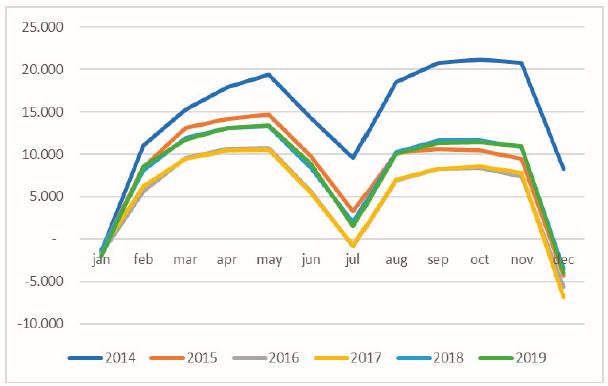

Chart 5 shows the balances arising from the hiring and termination per month, from January 2014 to December 2019. It can be noticed that the peaks of the positive balances, in which hiring significantly exceeds dismissals, are concentrated in two months, which coincide with the beginning of the school period: February and August. The valleys corresponding to negative balances, characterized by higher dismissals than hiring, are concentrated in three months, December, June, and July, corresponding to the end of the school semesters. Although the peaks in hiring and the valleys of dismissals are evident, the intense turnover of the workforce throughout the year, that is, during the period of classes, is noteworthy. At the peaks of positive balances (February and August), these vary in intensity, being not possible to establish a clear pattern in the period analyzed. Regarding negative balances, however, adjustments are more significant in December.

Source: MTP (2021).

CHART 5 Balances (hired; terminated) of higher education professor jobs in the private education system, Brazil - January 2014 to December 2019

It is worth to emphasize that December 2017, the first month after the reform, really had one of the worst dismissal balances of the last few years: 14,613 (exceeding the previous year by 1,505 dismissals). It is possible to note that this very same level is maintained in the subsequent years. In this sense, data presented herein confirm the news reports on the dismissal of private HEI professors broadcast in the press, they happened indeed.

However, it is possible to note that the dynamics of hirings and dismissals in the studied segment stands out from the overall Brazilian job market, in which the employment balance starts the year negative, but gradually recovers until it reaches its peak, usually in October and November, also decreasing in December. For professors working in private educational institutions, such a cycle is short and occurs twice in the same year, leading the employment balance accrued over the year to take the shape of a seagull (Chart 6). Nonetheless, it is a seagull that flies lower from 2015 on, evidencing a more moderate number of hirings and a higher number of terminations. The accrued employment bond balance for private professors presents negative figures since 2015, which resulted in a drop of 9,7% in bonds between 2015 and 2019.

Source: MTP (2021).

CHART 6 Evolution of the accrued employment bond balance for private higher education professors (2014-2019)

Data show that, apparently, the reform sanctions, and puts on a new level, practices that are common in the sector, which already worked with a significant turnover. In this regard, “massive” dismissals already occurred in the private higher educational institutions, usually by school vacations, but they seem to increase after the reform. Nonetheless, the economic crisis itself, by discouraging productive activities, also affects employment in the sector contributes to the adjustment of employment in the private higher educational institutions. From this perspective, it is very difficult to know for sure which is the influence of the reform on the dynamics of employment of such professors.

It is worth emphasizing that the turnover of the job market is acknowledgedly high in Brazil, but, usually, such an intense turnover of formal bonds affects especially the younger, less educated, and lower-income segments (Baltar & Proni, 1995; Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos [Inter Union Department of Statistics and Socioeconomic Studies] [DIEESE], 2016), which differs from the profile of university professors.

It is undeniable that the reform introduced new devices, such as the severance agreement and the non-obligation of approval by the union, which reduce costs and streamline the dismissal. For the severance agreement, the worker receives a fraction of the severance pay which he or she would be entitled to if the dismissal were without cause, the penalty is reduced to 20% of the FGTS deposits, and only half of the amount of the prior notice pay shall be paid. Therefore, the agreement may be beneficial to the worker in specific situations only; when he or she wishes to change jobs, for example, it is more beneficial to come to terms with the employer than resign.

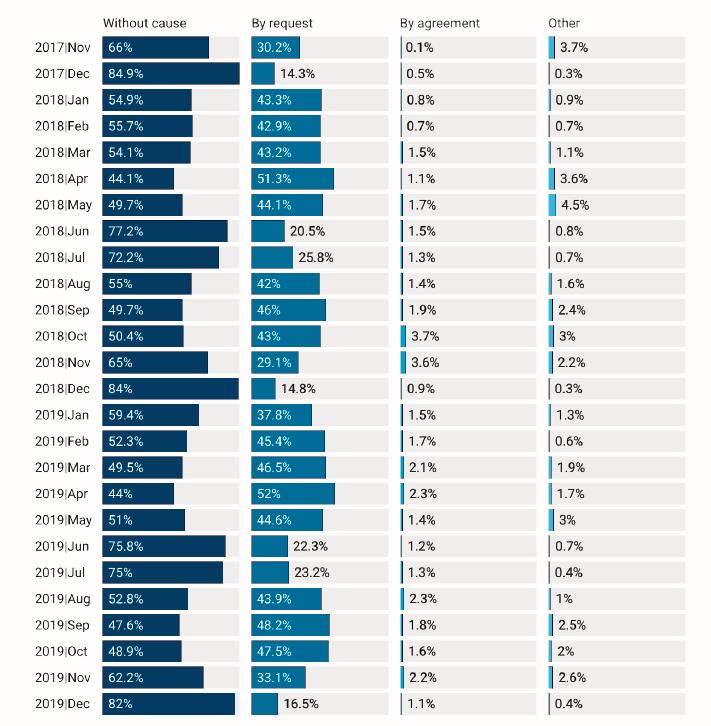

Figure 1 shows termination by type of turnover of professors, it can be noticed that, although termination by agreement has increased, this type of contract termination is still residual. Most dismissals continue to occur without cause or at the request of professors. It can be noticed that dismissals without cause are more significant, especially at the end of the two cycles previously identified, in the next months, or during university vacations. Dismissals at request occur more frequently in school months. This dynamic has not changed after the reform, however, the volume of termination has climbed some steps: in December 2017, the number of professors dismissed was 11,2% higher than the same period in 2016.

Source: MTP (2021).

FIGURE 1 Termination by type of turnover, professors working in private higher education, Brazil (%)

When the reform was passed, there was fear that employers might force workers to accept termination agreements, but data indicate that this does not appear to have occurred among university professors. Additionally, the new type of termination may not have inhibited the practice of known informal arrangements, which are more beneficial to employers and employees, even if they constitute fraud.

It is worth mentioning that dismissal, whether without cause or by agreement, does not always guarantee the worker the receipt of severance pay in its entirety. It is not uncommon for workers to resort to the Labor Courts, which results in the postponement of the amounts to be paid to the dismissed and attractive “discounts” to the businessmen (Campos, 2017).

However, the appeal to the Labor Court was not inexpensive for businessmen, who had to pay early attorney’s fees, in addition to not counting on the incentive of free legal services, even if they benefited from the delay in the court decision and enforcement of the lawsuit (Campos, 2017). It was often at the time of approval of the dismissal, made most of the time in the union of the category for contracts with an effective period of more than 12 months, that the union representative (or union lawyer) checked the termination form and guided the worker about their rights. By revoking this stage, the reform made it difficult and left the worker legally unassisted at the time of dismissal, not that the presence of the union representative or a lawyer is prohibited at the time of approval of the termination, but both have to travel to the company, which probably should result in less demand for labor court.

Another innovation of the reform, the intermittent employment contract, although shy, already appears among private professors. Caged data in relation to the intermittent contract for professors show positive balances in virtually every month between December 2017 and 2019. In August 2018 - a month, which, as seen, is traditionally one of hiring in the sector -, there was a positive balance of 51 intermittent contracts in the country, the highest monthly balance in the period analyzed. Altogether, 335 was the balance of intermittent contracts among private professors, contrasting with the negative balance of contracts in the segment in the period analyzed, pursuant to Chart 4.

The amendments to the part-time contract introduced by the Labor Reform encouraged the use of this type of contract in private higher education institutions. Between January 2018 and December 2019, the balance of partial contracts was 1,581.

What is noticeable is that some professor contracts were replaced by intermittent or partial contracts.

At this moment, it is difficult to isolate the effects of the reform, given the economic crisis, aggravated by characteristics of the segment, such as the excess of jobs offers in institutions, drop in enrollment, amendments to the FIES rules, and the growth of distance learning (EaD). About EaD it is worth a separate discussion. For now, it is important to mention that this is a bet of the segment, which should significantly affect the faculty of private HEIs. The press is also starting to report the expansion of EaD, see: Toledo (2016) and Oliveira (2017). Nonetheless, It is possible to say that that periodic dismissal should gain momentum among business adjustment strategies as a result of the Labor Reform, in addition to other strategies such as curriculum revision, a union of different classes, investment in EaD (Souza, 2011, 2017). Furthermore, that new hiring types may expand in an eventual recovery of the sector.

Final considerations

Higher education in Brazil, composed of public and private institutions, saw, in the ’90s, the portion-controlled by the private sector expanding significantly. In the following decade, despite the reinforcement given by the Lula and Rousseff governments to the FIES, the private sector kept its footprint and relevance, even relying on constant contribution from those governments.

Hence, private higher education, although at the same time subsidized by the Government, handed to the economic logic typical of the market, which involves relationships of competition between companies and class relations with their employees, the professors.

Typical consequences derive from the competitive logic, such as the intense mergers and acquisitions movement that has taken over the sector, which gave rise to several national and international business groups, among which are: Kroton, Ser Educacional, Sistema Educacional Brasileiro (SEB), Estácio de Sá, Laureate, DeVry and Unip. Oligopolization changed the form of management and financing of private HEIs, previously controlled by family sponsors and nowadays under the control of investment funds/banks. In this regard, higher education has become another space for the appreciation of financial capital.

On the internal plan, of the relationships between employers and employees, higher education companies naturally make use of management strategies that imply a necessary and chronic cost reduction movement, for which the Labor Reform is frankly welcome. In addition to periodic dismissals, other strategies to cost reduction were also used: curriculum revision, joining different classes, investment in EaD (Souza, 2011, 2017). A reform comes, therefore, to increase the already high degree of easing and cost reduction related to teaching work.

REFERENCES

Almeida, W. M. (2012). Ampliação do acesso ao ensino superior privado lucrativo brasileiro: Um estudo sociológico com bolsistas do ProUni na cidade de São Paulo [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Alvarenga, D., & Trevisan, K. (2017, dezembro 6). Estácio anuncia “demissão em massa” de professores, diz sindicato. Portal G1. https://g1.globo.com/economia/noticia/estacio-promove-demissao-em-massa-de-professores-diz-sindicato.ghtml [ Links ]

Arruda, A. L. B. (2011). Expansão da educação superior: Uma análise do programa de apoio a planos de reestruturação e expansão das universidades federais (Reuni) na Universidade Federal de Pernambuco [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. [ Links ]

Baltar, P. E., & Proni, M. W. (1995). Flexibilidade do trabalho, emprego e estrutura salarial no Brasil (Cadernos do Cesit e Texto para Discussão, 15). Unicamp. [ Links ]

Basílio, A. L. (2017, dezembro 6). Após reforma trabalhista, Estácio demite para chamar professor intermitente. Carta Capital. https://www.cartacapital.com.br/educacao/Apos-reforma-trabalhista-Estacio-demite-para-chamar-professor-intermitente [ Links ]

Bielschowsky, C. E. (2020). Tendências de precarização do ensino superior privado no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Política e Administração da Educação, 36(1), 241-271. [ Links ]

Campos, A. G. (2017). Justiça do trabalho e produtividade no Brasil: Checando hipóteses dos anos 1990 e 2000 (Texto para discussão n. 2.330). Ipea. [ Links ]

Carvalho, C. H. A. (2002). Reforma Universitária e os Mecanismos de Incentivo à Expansão do Ensino Superior Privado no Brasil (1964-1984) [Dissertação de Mestrado]. Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Economia. [ Links ]

Carvalho, C. H. A. (2005, novembro). Política de ensino superior e renúncia fiscal: Da Reforma Universitária de 1968 ao ProUni. Reunião Anual da Anped, 28, Caxambu, MG, Brasil. [ Links ]

Cavalcante, F. (2017). Reforma trabalhista: Salário e remuneração. https://jus.com.br/artigos/60740/reforma-trabalhista-salario-e-remuneracao [ Links ]

Chahad, J. P. Z. (2017). Reforma trabalhista de 2017: Principais alterações no Contrato de Trabalho. Informações Fipe. [ Links ]

Chahad, J. P. Z. (2018). Reforma trabalhista de 2017: Mudanças nas negociações coletivas e na organização sindical. Informações Fipe. [ Links ]

Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho (CLT), de 1º de maio de 1943. (1943). Aprova a consolidação das leis do trabalho. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/del5452.htm [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. (1988). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm [ Links ]

Cunha, L. A. (2007). A universidade temporã: O ensino superior, da colônia à Era Vargas. Edunesp. [ Links ]

Cunha, L. A. (2003). O ensino superior no octênio FHC. Educação & Sociedade, 24(82), 37-61. [ Links ]

Decreto n. 19.851, de 11 de abril de 1931. (1931). Dispõe que o ensino superior no Brasil obedecerá, de preferência, ao sistema universitário, podendo ainda ser ministrado em institutos isolados, e que a organização técnica e administrativa das universidades é instituída no presente Decreto, regendo-se os institutos isolados pelos respectivos regulamentos, observados os dispositivos do seguinte Estatuto das Universidades Brasileiras. https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1930-1939/decreto-19851-11-abril-1931-505837-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html [ Links ]

Decreto n. 2.306, de 19 de agosto de 1997. (1997). Regulamenta, para o Sistema Federal de Ensino, as disposições contidas no art. 10 da Medida Provisória n. 1.477-39, de 8 de agosto de 1997, e nos arts. 16, 19, 20, 45, 46 e § 1º, 52, parágrafo único, 54 e 88 da Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, e dá outras providências. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/D2306impressao.htm [ Links ]

Decreto n. 6.096, de 24 de abril de 2007. Institui o Programa de Apoio a Planos de Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais - Reuni. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2007/decreto/d6096.htm [ Links ]

Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos. (2016). Rotatividade no mercado de trabalho brasileiro: 2002 a 2014. Dieese. [ Links ]

Haddad, F. (2006). Entrevista: Educação: uma visão sistêmica. Teoria e Debate, 67. https://teoriaedebate.org.br/2006/09/26/educacao-uma-visao-sistemica/ [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. (1999). Evolução do Ensino Superior: 1980-1998. Inep. http://portal.inep.gov.br/informacao-da-publicacao/-/asset_publisher/6JYIsGMAMkW1/document/id/491251 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. (2001). Sinopse estatística da educação superior - 2000. Inep. https://download.inep.gov.br/download/censo/2000/Superior/sinopse_superior-2000.pdf [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. (2015). Sinopse estatística da educação superior. Inep. https://download.inep.gov.br/informacoes_estatisticas/sinopses_estatisticas/sinopses_educacao_superior/sinopse_educacao_superior_2015.zip [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. (2019). Sinopse estatística da educação superior. Inep. https://download.inep.gov.br/informacoes_estatisticas/sinopses_estatisticas/sinopses_educacao_superior/sinopse_educacao_superior_2019.zip [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. (2020). Sinopses estatísticas da educação superior - Graduação. 1995-2019. Inep. https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/dados-abertos/sinopses-estatisticas/educacao-superior-graduacao [ Links ]

Krein, J. D., Abílio, L., Freitas, P., Borsai, P., & Cruz, R. (2018). Flexibilização das relações de trabalho: Insegurança para os trabalhadores. In J. D. Krein, D. M. Gimenez, & A. L. Santos (Orgs.). Dimensões críticas da reforma trabalhista no Brasil. Curt Nimuendajú. [ Links ]

Lavinas, L., Araújo, E., & Bruno, M. (2017). Brasil: Vanguarda da financeirização entre os emergentes? (Texto para Discussão n. 32). Instituto de Economia/UFRJ. [ Links ]

Leda, D. B. (2009). Trabalho docente no ensino superior privado: Análise das condições de saúde e de trabalho em instituições privadas no estado do Maranhão [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia Social. [ Links ]

Leher, R. A. (2013). Universidade reformada: Atualidade para pensar tendências da educação superior 25 anos após sua publicação. Revista Contemporânea de Educação, 8(16), 305-329. [ Links ]

Lei n. 5.540, de 28 de novembro de1968. (1968). Fixa normas de organização e funcionamento do ensino superior e sua articulação com a escola média, e dá outras providências. https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/lei/1960-1969/lei-5540-28-novembro-1968-359201-publicacaooriginal-1-pl.html [ Links ]

Lei n. 11.096, de 13 de janeiro de 2005. (2005). Institui o Programa Universidade para Todos - Prouni, regula a atuação de entidades beneficentes de assistência social no ensino superior; altera a Lei n. 10.891, de 9 de julho de 2004, e dá outras providências. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/lei/l11096.htm [ Links ]

Lei n. 13.429, de 31 de março de 2017. (2017). Altera dispositivos da Lei n. 6.019, de 3 de janeiro de 1974, que dispõe sobre o trabalho temporário nas empresas urbanas e dá outras providências; e dispõe sobre as relações de trabalho na empresa de prestação de serviços a terceiros. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/lei/l13429.htm [ Links ]

Lei n. 13.467, de 13 de julho de 2017. (2017). Altera a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho (CLT), aprovada pelo Decreto-Lei n. 5.452, de 1º de maio de 1943, e as Leis n. 6.019, de 3 de janeiro de 1974, 8.036, de 11 de maio de 1990, e 8.212, de 24 de julho de 1991, a fim de adequar a legislação às novas relações de trabalho. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/lei/l13467.htm [ Links ]

Marques, A. C. H., & Cepêda, V. A. (2012). Um perfil sobre a expansão do ensino superior recente no Brasil: Aspectos democráticos e inclusivos. Perspectivas, 42, 161-192. [ Links ]

Martins, A. (2009). Reforma universitária de 1968 e a abertura para o ensino superior privado no Brasil. Educação & Sociedade, 30(106), 15-35. [ Links ]

Mendonça, H. (2017, 7 dezembro). Demissões na Estácio de Sá expõem temor em torno de reforma trabalhista. El País Brasil. https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/12/06/politica/1512591440_338894.html [ Links ]

Ministério do Trabalho e Previdência. (2021). Programa de Disseminação das Estatísticas do Trabalho (PDET). Cadastro Geral de Empregados e Desempregados (Caged) e Relação Anual de Informações Sociais (Rais). Brasília-DF, 2012-2019. MTP. https://bi.mte.gov.br/bgcaged/ [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. (2017, 1 setembro). Censo da Educação Superior aponta crescimento do ensino à distância. Jornal Estado de Minas. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/especiais/educacao/2017/09/01/internas_educacao,896936/censo-da-educacao-superior-aponta-crescimento-do-ensino-a-distancia.shtml [ Links ]

Oliveira, R. P. (2009). A transformação da educação em mercadoria no Brasil. Educação & Sociedade, 30(108), 739-760. [ Links ]

Sampaio, H. (2000). Ensino superior no Brasil: O setor privado. Hucitec/Fapesp. [ Links ]

Sampaio, H. (2011). O setor privado de ensino superior no Brasil: Continuidades e transformações. Revista Ensino Superior, 4, 28-43. [ Links ]

Sebim, C. C. (2014). A intensificação do trabalho docente no processo de financeirização da educação superior: O caso da Kroton no estado do Espírito Santo [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. [ Links ]

Siqueira, T. A. (2006). O trabalho docente nas instituições de ensino superior privado em Brasília [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade de Brasília, Programa de Pós-graduação em Sociologia. [ Links ]

Souza, A. H. (2011). Da educação mercadoria à certificação vazia. Le Monde Diplomatique, 53. http://diplomatique.org.br/da-educacao-mercadoria-a-certificacao-vazia/ [ Links ]

Souza, A. H. (2017). Ensino mercantil e demissão em massa de professores no ensino superior privado. Le Monde Diplomatique. https://diplomatique.org.br/ensino-mercantil-e-demissao-em-massa-de-professores-no-ensino-superior-privado/ [ Links ]

Toledo, L. F. (2016, 8 junho). Só 8 grupos concentram 27,8% das matrículas do ensino superior. Estado de São Paulo. http://educacao.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,apenas-8-grupos-privados-concentram-27-8-das-matriculas-do-ensino-superior,10000055857 [ Links ]

Weber, S. (2000). Políticas do ensino superior: Perspectivas para a próxima década. Revista Tempo e Presença, 22(312). [ Links ]

Received: May 27, 2021; Accepted: November 12, 2021

texto em

texto em