Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.52 São Paulo 2022 Epub 27-Mar-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053149773

BASIC EDUCATION, CULTURE, CURRICULUM

QUILOMBOLA SCHOOL EDUCATION IN DEBATE

IUniversidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil;

IIUniversidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), Niterói (RJ), Brazil;

IIIUniversidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil;

IVFreelancer, São Paulo (SP), Brazil;

This article aims to map and analyze the academic output on quilombola school education from 2009 to 2019 by means of a systematic review. The debate’s centrality addresses three issues: differentiated education, identity, and challenges to the implementation of quilombola school education. We conclude that the analyzed output still presents a first wave of demands for quilombola school education as a form of education. It is necessary to launch a second wave, one that investigates and evaluates quilombola school experiences in different contexts and regions so as to inform solutions for concrete problems on the pedagogical and funding aspects of quilombola school education.

Key words: DIFFERENTIATED EDUCATION; QUILOMBOLA SCHOOL EDUCATION; QUILOMBOLA EDUCATION; DIFFERENTIATED PEDAGOGY

Este artigo tem como objetivo mapear e analisar a produção acadêmica sobre educação escolar quilombola, no período de 2009 a 2019. A metodologia utilizada foi a revisão sistemática, acionando a centralidade do debate em três questões: educação diferenciada, identidade e desafios para implementação da educação escolar quilombola. Concluímos que a produção analisada ainda apresenta uma primeira onda de reivindicação da educação escolar quilombola como modalidade de educação. Torna-se necessária a iniciação de uma segunda onda que busque investigar e avaliar as experiências quilombolas escolares em diferentes contextos e regiões na tentativa de subsidiar a resolução de problemas concretos sobre os aspectos pedagógicos e de financiamento da educação escolar quilombola.

Palavras-Chave: EDUCAÇÃO DIFERENCIADA; EDUCAÇÃO ESCOLAR QUILOMBOLA; EDUCAÇÃO QUILOMBOLA; PEDAGOGIA DIFERENCIADA

Este artículo tiene como objetivo mapear y analizar la producción académica sobre la educación escolar quilombola, de 2009 a 2019. La metodología utilizada fue una revisión sistemática. La centralidad del debate dispara tres interrogantes: educación diferenciada, identidade y desafíos para la implementación de la educación escolar quilombola. Concluimos que la producción analizada aún presenta una primera oleada de reclamos por la educación escolar quilombola como modalidad de educación. Es necesario iniciar una segunda que busque investigar y evaluar experiencias escolares quilombolas en diferentes contextos y regiones en un intento de subsidiar la resolución de problemas concretos sobre los aspectos pedagógicos y financieros de la educación escolar quilombola.

Palabras-clave: EDUCACIÓN DIFERENCIADA; EDUCACIÓN ESCOLAR QUILOMBOLA; EDUCACIÓN QUILOMBOLA; PEDAGOGÍA DIFERENCIADA

Cet article vise à cartographier et analyser la production académique sur l’enseignement scolaire quilombola, de 2009 à 2019. Une revue systématique de la litterature axée sur la centralité du débat qui déclenche trois questions: l’éducation différenciée, identité et les défis pour la mise en œuvre de l’enseignement scolaire quilombola. La production analysée présente encore une première vague de revendications pour l’éducation scolaire quilombola comme modalité d’enseignement. Il est nécessaire d’initier une deuxième qui cherche à enquêter et à évaluer les expériences des écoles quilombolas dans différents contextes et régions pour tenter de fournir des subsides à la résolution de problèmes concrets rélatifs à des aspects pédagogiques et budgétaires de l’éducation scolaire quilombola.

Key words: ÉDUCATION DIFFÉRENCIÉE; ÉDUCATION ÉCOLE QUILOMBOLA; ÉDUCATION QUILOMBOLA; PÉDAGOGIE DIFFÉRENCIÉE

THE EMERGENCE OF A “QUILOMBOLA QUESTION”, UNDERSTOOD AS A SET OF POLITICAL struggles between social actors and demands for rights that benefit these specific ethnic groups did not occur in the Brazilian political debate until the enactment of article 68 of the Atos das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias [Transitory Constitutional Provisions Act] (ADCT) of the 1988 Constituição Federal [Federal Constitution] (CF). According to this article of the Constituição Federal: “the remaining members of quilombo communities who currently occupy these communities’ lands are hereby granted definitive ownership over them, and the State shall issue them the respective titles” (1988, p. 160, own translation).

The imprecision of the notion of remaining members mobilized different actors and arenas of debate after the enactment of the Constituição Federal. The legal definition of “remaining members of quilombo communities” thus became the object of exegesis on the part of social movements, law and anthropology scholarship, government agencies, and members of the ranchers’ caucus in Brazilian Congress, these last interested in limiting rights on access to land (Arruti, 2006; Jorge, 2016).

In 2004, the ranchers’ caucus filed an Ação Direta de Insconstitucionalidade [Direct Action of Unconstitutionality] (ADI) with the Supremo Tribunal Federal [Federal Supreme Court] (STF) challenging Decreto [Decree] n. 4.887 (2003). The ADI argued that the decree distorted the notion of “remaining members of quilombo” by refusing to delimit the right to land temporally only to groups who remained in the lands after 1888, the year slavery was officially abolished in Brazil. The solution did not come until 2018, when the STF ruled for the dismissal of the action. Thus, a broader notion of remaining members prevailed which was set forth by Decreto n. 4.887 (2003) and founded on debates mainly originating from Brazilian anthropology scholarship (Jorge & Brandão, 2018).

Despite the disputes on the legal and anthropological meaning of the notion of remaining members of quilombos, the field of education assumed the demands of these groups of reference as legitimate. The demands for a educação escolar quilombola [quilombola school education] (EEQ) gained national weight with the I Encontro Nacional das Comunidades Negras Rurais Quilombolas [1st National Conference of Rural Quilombola Black Communities], in 1995 (Silva, 2012). This event marked the political organization and mobilization of the communities and brought visibility to the quilombola agenda in the Brazilian arena. In this movement the Comissão Nacional Provisória das Comunidades Rurais Negras Quilombolas [National Provisory Rural Quilombola Black Communities Commission] was created, and in the following year the Comissão Nacional Provisória das Comunidades Rurais Negras Quilombolas [National Coordination for the Organization of Rural Quilombola Black Communities] was instituted (Coordenação Nacional de Articulação de Quilombos [Conaq], 2021). We highlight that at this first national congress demonstrators handed a letter to the federal government calling for a differentiated education for quilombola communities.

In 2012 the Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Escolar Quilombola na Educação Básica [National Curriculum Guidelines for Quilombola School Education in Basic Education] (DCNEEQ) were established. According to the DCNEEQ, EEQ should be implemented as a public education policy, establishing an interface with existing education policies for rural and indigenous peoples (Resolução n. 8, 2012). The guidelines also recommend that the political pedagogical project] (PPP) and the school curriculum consider the specificities of the community in which the school is situated, and that school managers, teachers and support personnel are recruited preferably from members of the quilombola communities.

EEQ in the sphere of public education policy is an important object of academic research in terms of both analyzing this category of differentiated education experience and thinking about the limits of policy and legislation on this form of education. Education researchers and practitioners mobilized and multiplied experiences in schools and communities denominated quilombola. The accumulated literature constitutes rich material about EEQ experiences and reveals the limits, dilemmas and potential of such public policy. This article examines the state of the art in EEQ based on scientific journals, particularly journals related with education. Thus, our aim was to map and analyze the academic output on quilombola school education from 2009 to 2019 so as to offer a panorama of this debate.

Methodology

Our approach was founded on the methodological principles of systematic review. This type of review follows rigorous article selection criteria which allow reducing research bias in selecting and defining the study’s corpus. The question that guided our search was: what does the scientific output on quilombola school education in the 2009-2019 temporal arc say?

The database used was SciELO Brasil, since the debate of EEQ develops generally in the national sphere. The temporal arc defined to address the question was from 2009 to 2019 in order to cover years before and after the DCNEEQ were issued. In the survey we used the following combinations of search terms and operators: Quilombola OR Quilombolas AND Educação. We repeated the search replacing the last term (educação) with the words: currículo, escola, escolar, educação escolar, formação docente, ensino, educação básica, educação quilombola, pedagogia, saberes, saber, formação de professores, professor, professora [curriculum, school, school education, teacher education, teaching, basic education, quilombola education, pedagogy, education of teachers, teacher].1 Below we detail the number of works found in this first stage, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Keywords and the total of articles found

| Quilombola OR Quilombolas AND: | Total of articles found |

|---|---|

| Educação (Education) | 34 |

| Currículo | 2 |

| Escola | 10 |

| Escolar | 14 |

| Educação escolar | 12 |

| Formação docente | 1 |

| Ensino | 6 |

| Educação básica | 2 |

| Educação quilombola | 6 |

| Pedagogia | 2 |

| Saberes | 15 |

| Saber | 6 |

| Formação de professores | 0 |

| Professor | 0 |

| Professora | 0 |

| Total | 110 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Following the systematic review protocol, two researchers carried out the survey and selection of articles independently. The divergences in these stages were solved by a third researcher. As inclusion criteria, we used the articles which deal directly with EEQ in the delimited temporal arc. We excluded articles that: a) were outside the temporal arc; b) did not deal directly with EEQ; c) addressed quilombola health; and d) were reviews or summaries.

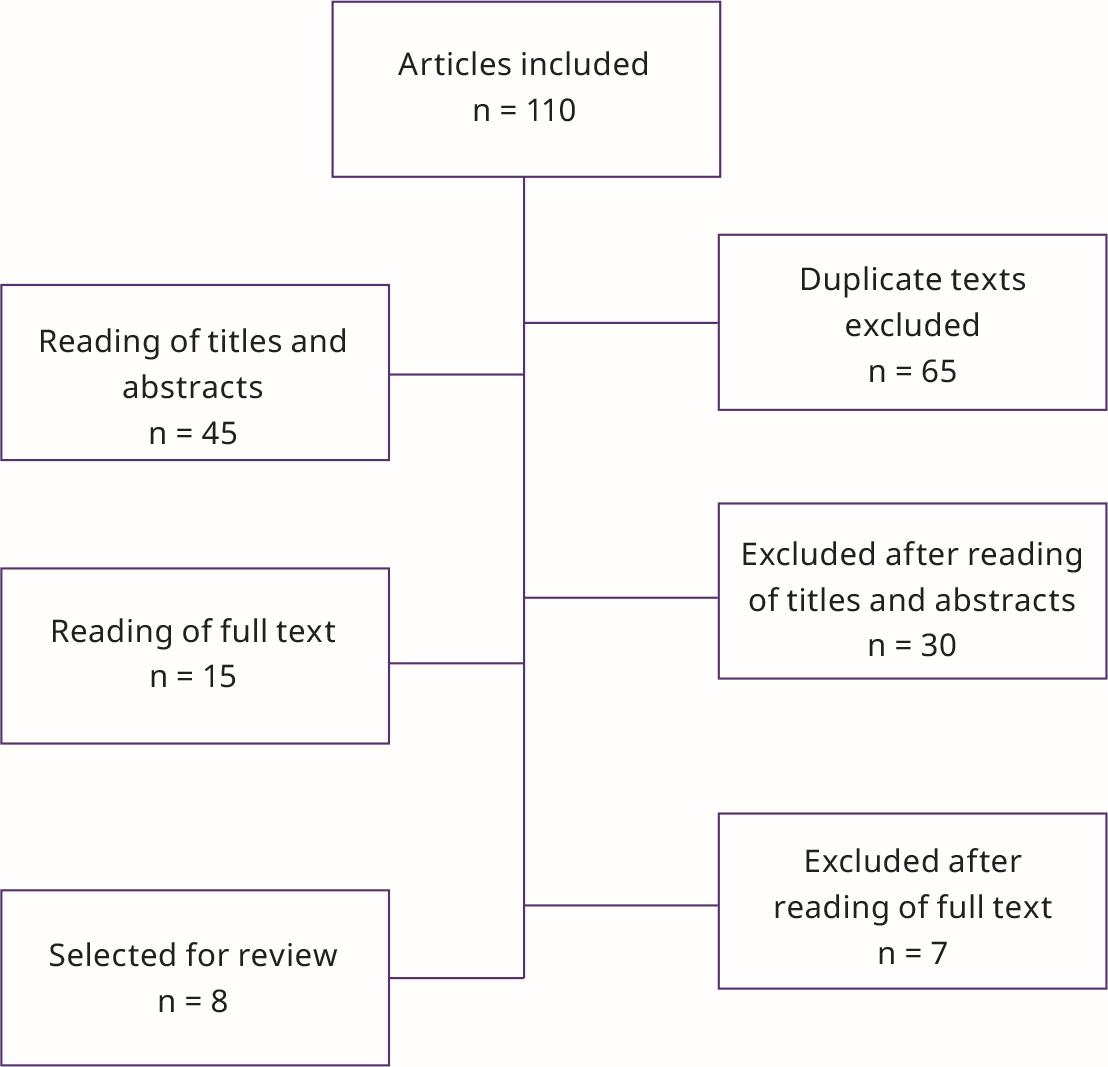

In the initial survey, we arrived at the total of 110 articles. In the second stage, we removed duplicate texts, thereby excluding 65 articles, and thus 45 remained. In the third stage, we read the abstracts of those 45 articles, observing the defined criteria. Thirty articles were thus excluded, and 15 remained for the fourth stage.

In the fourth stage, we read the full texts of the 15 articles and excluded another 7 as they were not directly aligned with EEQ. One of these excluded articles, which had passed through the previous filters, was a review of theses and dissertations. In the last stage we treated analytically the eight articles that fitted the inclusion criterion. This process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Results

The texts analyzed are shown in Table 2. To facilitate understanding the analysis process, we organized the articles into three categories, which were defined after reading their full texts: differentiated education; identity; and challenges to the implementation of EEQ. We highlight that some articles fitted more than one category.

Table 2 Articles analyzed after the selection process

| JOURNAL | YEAR | AUTHORS | TITLE | ARTICLE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educação & Realidade | 2019 | Monteiro & Reis | Patrimônio afro-brasileiro no contexto da educação escolar quilombola | 1 |

| 2019 | Santos et al. | Oferta de escolas de educação escolar quilombola no Nordeste brasileiro | 2 | |

| Educar em Revista | 2019 | Custódio & Foster | Educação escolar quilombola no Brasil: uma análise sobre os materiais didáticos produzidos pelos sistemas estaduais de ensino | 3 |

| 2015 | Arroyo | Os movimentos sociais e a construção de outros currículos | 4 | |

| Revista Brasileira de Educação | 2017 | Carril | Os desafios da educação quilombola no Brasil: o território como contexto e texto | 5 |

| 2012 | Miranda | Educação escolar quilombola em Minas Gerais: entre ausências e emergências | 6 | |

| Cadernos de Pesquisa | 2016 | Maroun | Jongo e educação escolar quilombola: diálogos no campo do currículo | 7 |

| Bolema | 2016 | Santos & Silva | A influência da cultura local no processo de ensino e aprendizagem de matemática numa comunidade quilombola | 8 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Differentiated education

This category comprises four articles, two of which are essays, and two are field studies discussing the relationship between EEQ and quilombola education in a broad sense. They view that quilombola education is conducted in all kinds of community organization and that a differentiated education considers the relationship of the community with the territory, the traditional forms of knowledge, the group’s memory of its origin, the cultural, political and economic production. The notion of differentiated education in the analyzed articles is similar to that of contextualized education, which involves adapting the curriculum to the local territory, culture and identity, based on students’ reality (Silva, 2002). According to Maroun (2016, p. 499, own translation), the subject of quilombola communities is addressed in academic research without “being founded on a concept common to such category”.

Monteiro and Reis (2019) - article 1 - present reflections about childhoods, jongo, quilombola education in communities and schools, and the DCNEEQ. One of the paper’s intents is to point out that childhood should be thought of in the plural and that there is no such thing as an abstract, decontextualized infant. These reflections are based on studies and projects the researchers conducted in quilombola communities in the state of Rio de Janeiro. The subjects that border on EEQ in their text are: the legal aspects underpinning the creation of the DCNEEQ; the legal framework and the slow titling process for quilombola territories; the evolution of the conception of quilombo; and jongo as an educational element.

In 2005, jongo, as an expression of black communities, became a Brazilian cultural heritage. In the Machadinha community, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, practicing jongo enabled young people to deconstruct feelings of shame arising from discrimination and prejudice against African-origin expressions and thus affirm group admiration, appreciation and pride. The authors argue that the educational potential of jongo as a social practice that confers pride on the quilombola identity for new generations, if incorporated into the school curriculum, can be a form of resistance to the Eurocentric education model and an ally in implementing the DCNEEQ.

Monteiro and Reis (2019) describe the initiative of the Machadinha community in that direction, which through a partnership with the local school, included “children’s jongo” as a school activity. The authors consider that this pedagogical work with jongo allows for appreciation of quilombo stories and contributes to “fighting and deconstructing racism at school” (Monteiro & Reis, 2019, p. 16, own translation).

Despite the educational and social-cohesion potential of jongo in the studied communities, Monteiro and Reis (2019 , p. 12, own translation) denounced that the “reality of quilombola schools, however, still seems far from what the guidelines set forth”. Thus, they point out the need for schools to build dialogue with quilombola communities by preserving local traditions and incorporating cultural expressions in their pedagogical practices.

Maroun (2016) analyzed the curriculum relationship between jongo and EEQ based on a case study in the Santa Rita do Bracuí quilombola community, in the municipality of Angra dos Reis, Rio de Janeiro - article 7. The text begins with a discussion on the main educational milestones related with EEQ, contextualizing the reader with the relevant events that furthered the creation of these guidelines on EEQ. Exegesis on the DCNEEQ is a feature of most of the selected articles.

Jongo is also in that article’s central argument. According to Maroun (2016), jongo remained dormant for many years, i.e., this cultural expression suffered religious constraints and lacked visibility in Bracuí’s local culture, which represented it in a derogatory manner, associating it with macumba. Invisibility, rejection, resistance, resignification and empowerment are terms which appear in the narratives and are reproduced in article 7, as well as in article 1. The narrative compellingly suggests that there was some kind of ban on children and young people participating in jongo circles due to religious beliefs and prejudices associated with that practice. However, here, too, the scenario begins to change in the mid-1990s, when the community itself restores jongo with old local jongueiros. Jongo, previously restricted to adults and those seasoned in the arts of drumming, singing pontos, dancing, and in traditional skills, is now shared with children, young people and women, who have become its main players and disseminators.

Maroun (2016) narrates how jongo progressively became a quilombola education practice in the community. In 2005, the community’s leaders built and implemented the “Pelos Caminhos do Jongo” project, funded by the NGO Brazil Foundation. As a result, jongo has been systematically taught in the community, making this experience a place of recognition of local memory, of African-descent culture, and of the Bracuí quilombola community’s identity. Thus, it was “through jongo that Bracuí launched its struggle for a differentiated education”, says Maroun (2016, p. 4, own translation). The author notes that jongo was, in that location, an expression of resistance of the community. While this notion of resistance is not consistently developed in the text, it may be said to relate (as with article 1) with the visibility and appreciation this practice has achieved in the region.

The timeline described in the text about the community-school relationship indicates communication difficulties between the social actors in that territory. The dialogue between community and school is presented as a process involving achievements, instances of progress and regression. The school, which was founded in 1970 in the territory, had not been classified as quilombola by the school census until 2015. Data about the numbers of quilombola and non- -quilombola students did not exist.2 Jongo was introduced in the school in 2003, according to local accounts, at a school event called Frutos da Terra. That was one of the first steps to ‘storming’ the school, with jongueiros performing their art in a folklorized fashion (Maroun, 2016). In 2005, for reasons internal to the school, the separation between it and the community increased again. The researcher observed, during the work field (2011-2012), that Bracuí leaders tried to deepen the relationship with the school. The intent was to approach jongo as an activity both theoretical and practical, with a view to combating the racism and prejudice generated by ignorance about the history and memory of the jongo community. This initiative took place even before the DCNEEQ were issued. During her field work, the community-school relationship made little progress.

Article 7 presents as information subsequent to the field work that a closer relationship was allegedly established on:

August 12, 2015, [when] at the local school a meeting was held, attended by political leaders, teachers, principals and coordinators of the Áurea Pires da Gama school and managers from the Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Angra dos Reis [Angra dos Reis Municipal Education Department] to establish a collective work agenda with a view to implementing a quilombola school education. (Maroun, 2016, p. 498, own translation).

Also, in Maroun (2016) a description emerges of a strong and organized community dealing with a school that treats students as abstract and resists allowing space for the local culture and community demands.

Carril (2017) - article 5 - analyzed the meaning and forms education can assume in the context of a quilombola territory. The author also refers to the invisibility of subjects related with quilombola knowledge in school curriculums and says that this is one of the concerns of the community’s leaders.

In the same vein as in texts 1 and 7, the author “proposes to conceive quilombola education based on contexts of territory use, ethnicity and memory” (Carril, 2017, p. 535, own translation). Here, jongo is also a central element for an account of the history of a community and its ancestry by means of poetic narratives, as with Cafundó, a quilombo in Salto de Pirapora, in the state of São Paulo (Carril, 2017).

The purpose of quilombola education, according to the author, is to break with a long history of ethnic and racial alienation and exclusion which began with the formation of Brazilian society. Thus, educational experiences based on the culture of these individuals can provide narratives that evoke the memory and life stories which can influence the formation of new subjectivities of students in these territories. Territory and territoriality should be the starting point to building a pedagogical process. Finally, Carril (2017) assigns ethnic and political value to the educational process, with a view to achieving transformations not only in school curriculums, but most of all, in the school culture.

Santos and Silva (2016) analyze aspects of mathematics teaching and learning in the context of quilombola education - article 8. They conducted a field research with a 7th grade class at a quilombola school in the city of Cachoeira, in the state of Bahia. A mathematics teacher and 19 students participated in the research. They point out as a result that the teacher recognizes the importance of contextualizing mathematics teaching with local experience, however, she admits difficulty making her teaching more dynamic because of gaps in her education and because she lacks pedagogical material. The researched teacher, in an effort to contextualize her teaching of the discipline, proposes as an assignment to survey prices in local stores, but she says this is not enough.

About students’ perception of the school, the text provides a few superficial impressions on the teaching-learning process. They say they consider mathematics a very important subject, but that classes should have more games, be more fun, and that they should leave the classroom to go out in the streets. The surveyed impressions are not problematized regarding what these accounts say about the school, the school culture and the curriculum beyond the discipline in question. Because Santos and Silva (2016) address EEQ, they also relate, though superficially, that the school works for the valuing of black culture by including samba-de-roda, dança afro, quadrilhas and other cultural practices in the curriculum; these facts, however, have no relation, whether direct or indirect, with the contextualized teaching of mathematics. Finally Santos and Silva (2016, p. 17, own translation) point out that “the need became clear for an effective approach to the forms of knowledge that students possess” and that the use of ethnomathematics can be an ally of the teacher in contextualizing such knowledge, however, ethnomathematics is reified in the article as a solution per se.

Identity

Monteiro and Reis (2019), as said earlier, point out that jongo represents a form of both resistance of black expression and protection of Brazilian cultural heritage in quilombola communities of the country’s Southeast region - article 1. Jongo, brought to Brazil by enslaved Africans, represents the preservation of black ancestry and, as a corollary, it is a path to affirming black and quilombola identity in the respective communities. According to the authors, the link between territory and identity composes a contemporary conception of quilombo. What characterizes a quilombola community, they say, is the relationship between territory, history, memory, tradition, sociability networks. It should be noted that the term “black identity” appears several times as an element which merges with the contemporary concept of quilombo. The authors describe that by entering the school curriculum, jongo has become a pedagogical device of identity affirmation as it speaks about the struggles and stories of quilombos in Brazil, besides deconstructing racism. In sum, they argue that there is still much unwillingness on schools’ part to value quilombola stories and knowledge and African-descent cultural expressions.

Maroun (2016) - article 7 - points out that the inclusion of quilombola children and youths in jongo in Santa Rita do Bracuí created possibilities for building and reaffirming quilombola identities through a community movement. Jongo enabled learning about, and appreciation of, quilombola ancestry, with stories of struggles of those who were enslaved, as well as the construction of identities as remaining members of quilombos and as an ethnic group. Self-identifying as a quilombola in the Santa Rita do Bracuí community is related with two issues: the positive recognition of the quilombola identity and the reaffirmation and appreciation of local cultural practices. Here it should be stressed that the author reaffirms, “the school did not contribute in any way to the identity formation process” (Maroun, 2016, p. 494, own translation).

Carril (2017) - article 5 - also points out the need for the quilombola school to protect and reinforce the quilombola and African-Brazilian identity, since racism and prejudice can also manifest in school environments: “The school cannot continue to act in relation to students, ideologically, as if they were all the same, reproducing an abstract ideal of individuals, and at the same time transmitting a neutrality in its curriculum contents” (Carril, 2017, p. 551, own translation). She stresses that “schools, teachers and educators are challenged to find paths that lead to multiple cultures within the school limits and beyond them” (Carril, 2017, p. 560, own translation). She concludes about this subject that quilombola territories represent the foundation for building quilombola subjects’ identities.

The construction, assemblage and reinforcement of quilombola identity is present in the analyzed output to a greater or lesser degree. The articles and the DCNEEQ bet on community power and the synergy relationship that schools and teachers can build in the territories they are part of.

Challenges to implementation

Monteiro and Reis (2019) - article 1 - point out the difficulty accessing data about quilombola schools. They also indicate as a challenge to the implementation of EEQ the significant number of recognized communities which still have not been granted title over their lands. While both issues are contained in a subsection of the text, we highlight that they were not problematized and work only as indication of “the lacks” in quilombola communities.

Discussing EEQ implementation difficulties, Carril (2017) highlights the poor conditions of the establishments, the lack of didactic resources and the absence of teacher education - article 5. Such information is based on data from Miranda’s (2012) study, which is also featured in our selection (article 6). About teacher education, some teachers, for example, have not themselves completed secondary (and in some cases primary) education. These facts demonstrate that there are lay teachers working at quilombola schools, which represents yet another difficulty and a kind of challenge to be overcome for implementing EEQ.

Some problems involve the lack of data to map the situation of schools serving the quilombola population. There are gaps in school census data about the residence of students from quilombola territories and about the existence of schools which were not identified with this form of education and are situated in quilombola territories (Carril, 2017). Another problem identified is that there are schools outside quilombola territories which serve quilombola students but do not use specific material for this form of education (Carril, 2017). While a school’s recognition as quilombola does not guarantee that the DCNEEQ are met, the fact that it is recognized makes it eligible for support from specific public policies for this form of education.

About infrastructure, the article relates that some schools have no more than two classrooms, others operate in temples or churches, and there are classrooms which are provided by other schools. This picture of deficiency is completed by cases where teachers teach classes at their own homes as some schools operate even in sheds and warehouses. Adding to this chaotic scenario, there is a lack of proper sewage and/or electricity, computers labs and sports courts (Miranda, 2012; Carril, 2017).

Carril’s (2017) argument is developed on these two planes. On one she indicates that there are many challenges to materializing the quilombola school in the education system, pointing out the deficiency in the functioning of this form of education. On the other, she suggests that creating a pedagogical approach that recognizes local knowledge and practices is the path to materializing a conception of differentiated education and construction of quilombola identities. Thus, Carril (2017) shows optimism about, and faith in, the DCNEEQ and the community potential for building a differentiated education that produces quilombola and black identities and fosters the combat of the racial democracy myth: despite all the deficiency and lacks which affect EEQ.

Arroyo (2015, p. 48) - article 4 - starts from the following question: what issues have been raised by the diversity of social movements, particularly in the countryside, for the construction of “another curriculum” in rural, indigenous and quilombola schools and in black peasant communities for building another teacher education curriculum? (Arroyo, 2015, p. 48, own translation). The author finds the answer in social movements. These, he says, are critical for materializing differentiated education curriculums, besides being a parameter for conceiving teacher education. Social movements have been “a pedagogist”, asserts Arroyo (2015). His argument is that the standard curriculum has become an instrument of regulation of knowledge and educational practices. Thus, social movements create inflection points for thinking about the particular knowledge, cultures and values which are brought into this universal model of school, since the official conception of universal education, an education with a curriculum for all, precludes thinking about the specificities of indigenous, quilombola and rural curriculums.

Arroyo’s article praises the strength of social movements because they evidence and rearrange politically the multiple forms of conflict in different social spheres. In sum, he argues that change in school might come from the potential he believes social movements have, as well as their possible influence over school curriculums to break with the reproduction of hegemonic conceptions which classify, rank and segregate popular knowledge and peoples. Despite his pedagogical optimism about social movements, he does not fail to point out the deficiency present in rural, indigenous and quilombola education. Criticism of such deficiency is featured in the articles selected here (articles 5 and 6).

Santos et al. (2019) present a panorama of the implementation of quilombola schools in Brazil’s Northeast region - article 2. The study analyzed EEQ offer based on records from the comunidades remanescente de quilombos [remaining quilombo communities] (CRQ) in municipalities and states. Education-related information was based on the Censo Escolar da Educação Básica [2013 School Census on Basic Education]. Data were collected from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics] (IBGE) and the Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira [National Institute for Educational Research and Studies Anísio Teixeira] (INEP) websites. The numbers about the quilombola communities certified until 2017 were provided by the Fundação Cultural Palmares [Palmares Cultural Foundation]. According to such data, until 2013 the Northeast region accounted for 64.42% of the EEQ offer and 67.69% of EEQ enrollments in Brazil. The study addresses the state’s responsibilities in the production of racial inequality and institutional racism, analyzing data about EEQ school offer, distribution and enrolments.

The discussion about institutional racism emerges from the state’s silences, omissions and instances of neglect, such as its failure to accurately diagnose and assess conditions in the CRQ and EEQ. According to the survey, the number of CRQ is far greater than the number of cities with CRQ; in the state of Bahia, for example, there are 139 cities with remaining quilombo communities and 607 quilombola communities. This fragmentation, according to the authors, decreases densification and hinders the implementation of EEQ (Santos et al., 2019).

The authors highlight that 85.54% of cities located in the Northeast have up to 50,000 inhabitants. For this reason, they have less autonomy to produce public policies and are more dependent on the federal government, making it harder for CRQ to benefit from specific public policies. More than one-third (34.91%) of cities with CRQ have no quilombola schools, and conversely, there are cities which have EEQ but no certified remaining communities. Such data mismatch may result from mistakes in school registration, a still ongoing certification process, or fraud intended to draw more funds from Fundeb (Santos et al., 2019, p. 14). Another hindrance to assessing the EEQ system refers to schools which are registered in more than one city, usually located on a border between municipalities.

The authors conclude that the discrepancies in EEQ and CRQ data compromise comprehension of their conditions, hindering the creation of strategies to improve education quality in the EEQ. Thus, they indicate that it is necessary to create a work group involving the INEP, the Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização, Diversidade e Inclusão [Secretariat of Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion] (Secadi), abolished by the Bolsonaro administration, the IBGE and the Fundação Cultural Palmares (managed under the Bolsonaro administration in a way that was contrary to its original goals) in order to adjust the necessary steps to ensure greater data reliability.

Custódio and Foster (2019) analyzed didactic materials of EEQ in basic education produced by different state education systems - article 3. One of their aims was to identify whether the topics quilombo, culture, traditions, work world, territory, orality and memory were approached by the didactic materials. They concluded that few materials exist and that existing materials are incipient and lacking in respect to the participation of the quilombola community in their making. They also criticized the homogenization found in didactic materials, which do not address the issue based on the ethnic variety and diversity of existing quilombos in our country. It is noteworthy that this kind of criticism, if taken to its limit, indicates that each community should have its specific didactic material, supposedly anchored in its local tradition.

Miranda (2012), in a paper of the same year as the issuance of the DCNEEQ, problematizes quilombola education in the sphere of education policies, considering the state of Minas Gerais - article 6. In the first two sections of the text the author presents historical reflections regarding quilombos, the process of resemantization of the term quilombola, and the legal framework that consolidated specific public policies. The third section is dedicated to debating the implementation of EEQ, with a focus on the context of deficiencies found in the state of Minas Gerais based on school census indicators included in the report of municipalities’ Plano de Ações Articuladas [Articulated Action Plan] (PAR), both published in 2010. In 2011 in the state of Minas Gerais there were 403 quilombola communities and 140 schools (state, municipal and private) in remaining quilombo areas.

The author denounces the problems facing EEQ regarding poor infrastructure, the concentration of schooling provision in the early years of primary education, the paucity and/or inexistence of schools in quilombola territories, deficient school transportation, and ignorance about the presence of quilombola communities in the same territories in which the system’s schools are located. This last factor can be associated with the confusion in the characterization of quilombos as rural communities, which certainly precludes the management of an EEQ policy. In addition, teacher education in EEQ is another challenge pointed out by the author at the time, and it persists in the more recent articles included in our selection. The author resorts to the I Seminário Nacional de Educação Quilombola [1st National Seminar on Quilombola Education] and says that “When the teacher does not belong to the community, they are seldom able to understand students’ differentiated world” (Miranda, 2012, pp. 376-377, own translation).

Discussion

The reiterative exegesis on the DCNEEQ

The literature consulted in the delimited temporal arc indicates primarily a broad zone of agreement between the analysts of EEQ. The studies value the legal achievements of quilombola communities, the recognition by the Constituição Federal (1988), and the creation of the DCNEEQ. They consider the DCNEEQ, rather uncritically, as a progress in education and deplore the fact hat schools and/or education systems are faced with difficulties, distances and opposition to the creation of curriculums that meet the guidelines and cultural demands of local communities.

They indicate the historical invisibility of and prejudice against African-descent culture but also show that jongo reemerged as an education practice in quilombola communities in the Southeast as a key factor in the constitution of local identities and as a promise of construction of a differentiated education for schools classified as quilombola. Jongo is considered normatively by the analysts as an experience to be incorporated into the curriculums of the quilombola schools of the respective jongo communities. As presented earlier, this cultural expression works as a contextualizing element for local forms of knowledge, the history of black resistance, and as an antiracist pedagogy. The empirical studies report that the schools observed in quilombola territories initially opposed or limited the entrance of this cultural experience. In general, jongo entered curriculums laterally when it was absorbed in school celebration occasions. This type of incorporation into the curriculum was considered by the researchers as superficial or folklorized.

Another common problem detected is the school’s difficulty establishing effective partnerships (dialogue) with the local community and social movements in designing the curriculum and implementing the DCNEEQ. According to the analysts, we are before the cultural power of quilombola communities in a relationship with schools that, in some cases, close themselves to local cultural experiences and treat their students as abstract, deterritorialized beings. It is worth noting that the idea of strong communities, with a high degree of cultural synergy and well-delimited identities (we-others), cannot be generalized for all quilombola communities (Soares et al., 2022).

We find in nearly all of the analyses the denouncement of poor school infrastructure, of schools working at different degrees of deficiency, lacking sanitation, properly trained, qualified faculty and teaching resources. This indicates that we are before public policies which recognize and give visibility and possibilities of affirmation to quilombola identities but have not created resource distribution mechanisms to materialize school and community plans for these populations (Fraser, 2002, 2007).

The school curriculum as the place of formation of identities, though a common feature in the grammar of education, deserves to be thought over as the totality of experiences in school life and as the sharing of specific knowledge treated in school activities and disciplines and, in the case of quilombola education, of cultural practices and knowledge of the community which should (or should not) be incorporated, where possible, into the regular disciplines and the school calendar. Indeed, normatively, the notion of curriculum in quilombola differentiated education requires that, according to the DCNEEQ, local knowledge and practices are ‘pedagogized’, in the sense of providing the necessary elements to form identities aware of the history of segregation and struggles of people of African descent in that social space and in Brazilian society. The struggle of black and quilombola movements against invisibility, segregation and inequality, and for ethnic pride, which does not tolerate racism. These are some of the elements that should be present in the curriculum of a quilombola school, according to the DCNEEQ and the analysts consulted here.

Here we pose a first question which should be problematized. In the articles consulted about EEQ we have the almost compulsory presence of exegesis on and repetition of the DCNEEQ. The empirical studies or essays treat their findings according to the “metrics” of the DCNEEQ. Thus, they arrive at a consensus that EEQ school practices are far from or not suitable according to DCNEEQ’s normative ideals from the perspective of pedagogical practices, discipline experiences, teacher education, didactic material, infrastructure, etc. While the studies present the positiveness of the attempts at building a differentiated education, it is worth highlighting that what predominates is a reiteration of the DCNEEQ as an unquestioned standard for comparison with the school experiences analyzed.

Besides representing an expression of ACDT rights and their alignment with Decreto n. 4.887 (2003), as pointed out by the selected articles, the DCNEEQ were inspired by a document called Princípios da Educação Escolar Quilombola de Pernambuco [Principles of the Quilombola School Education of Pernambuco]. Such document presents fourteen priority issues to be considered in the sphere of the quilombola school education of the state of Pernambuco (Nascimento, 2017). Thus, considering all these indications, we suggest that the good practices in education and schooling of quilombo Conceição das Crioulas, situated in Salgueiro, in the state of Pernambuco (Silva, 2012), were a central source for designing the DCNEEQ.

During the period when public hearings were being held to inform the creation of these guidelines, important debates took place about the education experience in the Conceição das Crioulas community. It is worth noting that two quilombola teachers from Conceição das Crioulas provided advice to the special committee of the Câmara de Educação Básica do Ministério da Educação e Cultura [Ministry of Education’s Basic Education Chamber] (MEC) during the creation of the guidelines. The public hearings’ theme was “The quilombola school education we have and the one we want”. It is worth noting that it was the same theme used in the diagnosis that informed the Princípios da Educação Escolar Quilombola de Pernambuco.

The differences from one quilombo to another comprehend dimensions: geographic, with urban and rural quilombos of different states of the country; political, regarding states and municipalities; identity-related, with a strong or weak recognition of the “we-other” delimitation (Barth, 2005); of community cohesion, with high, middle and low cohesion groups; of community interests, which can be centered in cultural and/or folkloric, rural and urban expressions (Mota, 2014), in practices related with work and/or handicraft, in religious solidarity, whether Christian (catholic or evangelical), of African descent, or syncretic (Schneider, 2015); among other differential dimensions that might be identified. These asymmetries are part of a set of questions that must be considered when analyzing EEQ implementation difficulties and potentials.

Indeed, the normative recognition (praised by the analysts in their papers) becomes ineffective when distribution of financial resources and other inputs is almost inexistent, if we consider the various “lacks” involved in this form of education (Fraser, 2002, 2007). Teixeira (2017) demonstrates that quilombola communities were symbolically included in government policies through the Programa Brasil Quilombola [Quilombola Brazil Program], but the same communities are for the most part scarcely benefited by specific social policies and were excluded by means of budget regulation.

Relationship between quilombolas’ community and school

The community-school relationship and interaction is a general question in the education field from the perspective of the construction of a democratic education, since school education is expected to be more effective if a minimum level of agreement and consensus exists between school, family and community. This challenge was posed by the Constituição Federal (1988) and assumed by Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação [National Education Guidelines and Framework Law] (LDB) (Lei n. 9.394, 1996) through the creation of school councils. That is one of the democratic management mechanisms set forth by the LDB, reaffirmed in national education plans, presupposing that the exercise of power is shared between the school community and the local community. However, this ideal of community participation is apparently not simple to implement in the Brazilian school system or elsewhere (Carvalho, 2000; Nogueira, 2006).

A closer relationship between school and community, if an EEQ is to be built and implemented, is a value and a strategy both in the articles and the DCNEEQ. The problems in this relationship between quilombola communities and their respective schools are not addressed in the analyzed articles.

It is necessary to observe that, each in its own way, the DCNEEQ and the selected articles support family/community participation mechanisms without the necessary critical view on this process and without thinking about the effects that these schools may be producing. In the case of quilombola education, three idealized bets are placed with belief in the power of community participation: on the community’s investment in the school, which should occur through families/local leaders; on the school and its teachers being an active part of the local community’s life; and on the local or popular culture as a producer of positive knowledge and values in the construction of a more egalitarian and democratic society.

We argue that the DCNEEQ and the analyses do not seem to consider: inequalities of cultural capital of families and communities; local deficits of cohesion, community identity and differential engagement of the various communities; families’ available time and students’ guardians’ employment situation and demands; the school culture, which in most cases allows community participation under the supervision of managers and teachers (Carvalho, 2000). Communities’ local culture is treated as positive and without questioning. It should be noted that local tradition, knowledge and popular culture can bear positive values, but they can also reproduce hierarchies, inequalities and other forms of conservatism and violence (Hall, 2003). Therefore, by itself, the bet on community positivity and on the community’s desire to participate in school life tends to overshadow tense power relations and a fragmentation in interdependent, mutually antagonistic groups within a particular community (Elias & Scotson, 2000).

We could not find in any of the papers accurate and dense descriptions of how this dialogue between community and school takes place. Likewise, we observed that the selected articles do not problematize communities in the sense of analyzing local hierarchies or practices which are non- -functional to the collective welfare. To the contrary, there seems to be in them a potential, normative and ideal harmonization of community life, without allusions to the constitutive tensions internal to each actor and existing between actors.

Adding to the naturalization of communities’ unreal participatory desires is the non- -problematization of specific constitution processes of these collectives as communities classified as quilombola. As argued by Amanda L. Jorge (2016), the constitution of old collectives, which were previously “not understood as quilombola”, into quilombola communities involves the constitution of “ethnic boundaries” which the group itself establishes with intersubjectively constructed criteria. If this process implies, on the one hand, a standard path of legal-bureaucratic steps from the initial work of external agents in mobilizing these groups, filing recognition procedures, making anthropological reports, until the desired end, i.e., titling of their land, on the other hand, it also has a practical, self-construction dimension related with the development and consolidation of the groups’ traits as quilombola to the outside and to itself.3 For example, Soares et al. (2022) presented a community with feelings of low cohesion and weak identity whose leaders projected on the public quilombola school a central role in building the community’s identity.

Problems and challenges in managing public differentiated schools

It is worth highlighting that one of DCNEEQ’s assumptions is a teacher engaged in the community in which the school is situated, preferably someone who is a member of the community and/or qualified to deal with the issues involved in differentiated education. However, the guidelines and authors examined here do not address the career of this type of idealized teacher or the school and work time required by this form of education in specific communities. If it is conceived as a differentiated education to repair diverse damages suffered by these populations (Castel, 2005, 2008; Arruti, 2009), then that requires focused treatment by public policies in budgeting the recruitment and training of qualified personnel, the expansion of teachers’ school and work time, and a career consistent with the type of link required by this form of education.

The literature indicates that a teacher education oriented to teaching at quilombola schools is necessary, since teachers who do not belong to the community find difficulty understanding students’ differentiated reality (Miranda, 2012). Miranda’s argument is in line with the DCNEEQ, which sets forth in its article 48 that EEQ is to be preferably conducted by teachers who belong to the quilombola communities, and in its article 47 that EEQ teachers are to be hired through competitive examination (Resolução n. 8, 2012).

These rules create various obstacles. The first is of an epistemological and pedagogical nature as it is normatively founded on the belief that a teacher’s being from the community will ensure better teaching for the quilombola children of their own community. It is important to note that experience can be a first key to access knowledge, but it may become an epistemological obstacle when people are stopped from advancing beyond it or have no opportunity to break with sensitive experience (Bourdieu, 2004). In pedagogical terms, the need for some degree of distance from localized social practice is in the basic conception of the republican school, which even in its less classic, more popular versions, such as Freirean education, does not dispense with the mediation provided by a scientific stance, particularly in cases where local belonging may reinforce apathy and an understanding of the world as hierarchy (Lovisolo, 1990).

The second obstacle does not consider the teacher culture in public service and in human resource management in the public sector, regardless of government level. Competitive examinations are usually oriented to a school system, not a particular school. Hiring teachers for particular schools can create management problems when education departments need to shift human resources due to change in student flow and numbers in schools and systems. But should education systems decide to move forward in the recruitment of qualified teachers from the community for particular schools, they must break with centralized recruitment. The systems must create specific careers, with work hours in line with the requirements of guidelines for this form of education. It is worth stressing that this approach must face public teachers organizations and unions and the difficult process of decentralization of school management in the public education system.

The analyses about quilombola schools’ faculty indicate that the symbolic recognition of these communities, materialized in the definition of this form of education and in the DCNEEQ, was not accompanied by effective public policies or a budget consistent with the challenges involved. Miranda (2012) and Carril (2017) point out that there are teachers in quilombola schools who have not completed primary education, i.e., when it comes to teacher education for quilombola schools, we run across a few dilemmas, such as the lack of academic education and teachers’ low education level. Indeed, legislators show mainly a desire to materialize a quilombola education with faith in the power of communities and schools, but do not build realistic policies with management mechanisms and budgeting in order for such policies’ goals to materialize. On the other hand, the analysts do not address in their papers the general tensions involved in the implementation of public education policies and how they are appropriated by actors at the practical end of the process, be they public managers or even teachers and principals (Lipsky, 2010).

Final considerations

The intent to select studies about EEQ was aimed at: enumerating and mapping some of the main elements listed by the researchers about this form of differentiated education; and underscoring the inconsistencies and confusions between normative and analytical dimensions. Such confusions end up obliterating the major challenges to the success of this education policy.

The analyzed output still presents a first wave of demands and legitimation of this subject and this form of education. It is necessary to launch a second wave of qualification of this output and of research that investigates and evaluates school experiences in the different communities, in an effort to inform the search for solutions for concrete problems about the pedagogical and funding aspects of quilombola school education.

Finally, one last challenge is to think about forms of conciliation in articulating and mediating the relationship of quilombola populations’ local knowledge and memory with common knowledge considered universal by what is generically understood as republican and democratic education (Castel, 2005, 2008).

REFERENCES

Arroyo, M. G. (2015). Os movimentos sociais e a construção de outros currículos. Educar em Revista, (55), 47-68. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.39832 [ Links ]

Arruti, J. M. (2006). Mocambo: Antropologia e história do processo de formação quilombola. Edusc. [ Links ]

Arruti, J. M. (2009). Políticas públicas para quilombos: Terra, educação e saúde. In M. de Paula, & R. Heringer (Orgs.), Caminhos convergentes: Estado e sociedade na superação das desigualdades raciais no Brasil (pp. 75-110). Fundação Heinrich Bollpp. [ Links ]

Barth, F. (2005). Etnicidade e o conceito de cultura. Antropolítica: Revista Contemporânea de Antropologia e Ciência Política, (19), 15-30. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (2004). O poder simbólico. Bertrand Brasil. [ Links ]

Carril, L. F. B. (2017). Os desafios da educação quilombola no Brasil: O território como contexto e texto. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 22(69), 539-564. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782017226927 [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. E. P. (2000). Relações entre família e escola e suas implicações de gênero. Cadernos de Pesquisa, (110), 143-155. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742000000200006 [ Links ]

Castel, R. (2005). A insegurança social: O que é ser protegido? Vozes. [ Links ]

Castel, R. (2008). A discriminação negativa: Cidadãos ou autóctones? Vozes. [ Links ]

Coordenação Nacional de Articulação de Quilombos (Conaq). (2021). Quem somos. http://conaq.org.br/nossa-historia/ [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. (2023). Supremo Tribunal Federal, Secretaria de Altos Estudos, Pesquisas e Gestão da Informação. (Atualizada até a EC n. 128/2022). Brasília, DF. https://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/legislacaoConstituicao/anexo/CF.pdf [ Links ]

Custódio, E. S., & Foster, E. L. S. (2019). Educação escolar quilombola no Brasil: Uma análise sobre os materiais didáticos produzidos pelos sistemas estaduais de ensino. Educar em Revista, 35(74), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.62715 [ Links ]

Decreto n. 4.887, de 20 de novembro de 2003. (2003). Regulamenta o procedimento para identificação, reconhecimento, delimitação, demarcação e titulação das terras ocupadas por remanescentes das comunidades dos quilombos de que trata o art. 68 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 4. https://legis.senado.leg.br/norma/406577/publicacao/15686405 [ Links ]

Elias, N., & Scotson, J. L. (2000). Os estabelecidos e os outsiders: Sociologia das relações de poder a partir de uma pequena comunidade. Revista de Antropologia, 1(2), 217-220. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. (2002). A justiça social na globalização: Redistribuição, reconhecimento e participação. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, (63), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.4000/rccs.1250 [ Links ]

Fraser, N. (2007). Reconhecimento sem ética? Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política, (70), 101-138. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-64452007000100006 [ Links ]

Hall, S. (2003). Da diáspora. Editora UFMG. [ Links ]

Jorge, A. L. (2016). O processo de construção da questão quilombola: Discursos em disputa. Gramma. [ Links ]

Jorge, A. L., & Brandão, A. A. P. (2018). A questão quilombola e o campo do direito. Estudos de Sociologia, 23(45), 123-138. https://doi.org/10.52780/res.10467 [ Links ]

Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. (1996). Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, DF. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/L9394.htm [ Links ]

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russel Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Lovisolo, H. (1990). Educação popular: Maioridade e conciliação. UFBA/Empresa Gráfica da Bahia. [ Links ]

Maroun, K. (2016). Jongo e educação escolar quilombola: Diálogos no campo do currículo. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 46(160), 484-502. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053143357 [ Links ]

Miranda, S. A. (2012). Educação escolar quilombola em Minas Gerais: Entre ausências e emergências. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 17(50), 369-383. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782012000200007 [ Links ]

Monteiro, E., & Reis, M. C. G. (2019). Patrimônio afro-brasileiro no contexto da educação escolar quilombola. Educação & Realidade, 44(2), Artigo e88369. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623688369 [ Links ]

Mota, F. R. (2014). Cidadãos em toda parte ou cidadãos à parte? Demandas por direitos e reconhecimento no Brasil e na França. Consequência. [ Links ]

Nascimento, M. J. (2017). Por uma pedagogia Crioula: Memória, identidade e resistência no quilombo de Conceição das Crioulas-PE [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade de Brasília]. Repositório Institucional da Universidade de Brasília. https://repositorio.unb.br/bitstream/10482/31319/1/2017_M%c3%a1rciaJucilenedoNascimento.pdf [ Links ]

Nogueira, M. A. (2006). Família e escola na contemporaneidade: Os meandros de uma relação. Educação & Realidade, 31(2), 155-169. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3172/317227044010.pdf [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. P. (Org.). (2011). A presença indígena no Nordeste: Processos de territorialização, modos de reconhecimento e regimes de memória. Contracapa. [ Links ]

Resolução n. 8, de 20 de novembro de 2012. (2012). Define diretrizes curriculares nacionais para educação escolar quilombola na educação básica. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF. http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=11963-rceb008-12-pdf&category_slug=novembro-2012-pdf&Itemid=30192 [ Links ]

Santos, E. S., Velloso, T. R., Nacif, P. G., & Silva, G. (2019). Oferta de escolas de educação escolar quilombola no Nordeste brasileiro. Educação & Realidade, 44(1), Artigo e81346. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623681346 [ Links ]

Santos, J. G., & Silva, J. N. D. (2016). A influência da cultura local no processo de ensino e aprendizagem de matemática numa comunidade quilombola. Boletim de Educação Matemática, 30(56), 972-991. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1980-4415v30n56a07 [ Links ]

Schneider, M. (2015). Identidades em rede: Um estudo etnográfico entre quilombolas e pomeranos na Serra dos Tapes [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal de Pelotas]. Guaiaca. http://guaiaca.ufpel.edu.br/handle/ri/2835 [ Links ]

Silva, A. P. G. da. (2002). O elogio da convivência e suas pedagogias subterrâneas no semi-árido brasileiro [Tese de Doutorado não publicada]. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. [ Links ]

Silva, G. M. (2012). Educação como processo de luta política: A experiência de “educação diferenciada” do território quilombola de conceição das crioulas [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade de Brasília]. Repositório Institucional da Universidade de Brasília. https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/12533 [ Links ]

Soares, D. G., Maroun, K., & Soares, A. J. G. (2022). A construção social de uma escola quilombola: A experiência da Comunidade Caveira, RJ. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 27. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782022270011 [ Links ]

Teixeira, T. G. (2017). O ocaso do Programa Brasil Quilombola no Brasil e no Maranhão: Uma análise orçamentária. Anais do 41. Encontro da Anpad, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. http://arquivo.anpad.org.br/abrir_pdf.php?e=MjI5MjE= [ Links ]

1 T.N.: There are less English terms between the brackets than in the Portuguese list preceding them because some Portuguese terms do not have an equivalent in English. These are: escolar - an adjective for things related to school; saberes - the plural form of saber, a noun that means a particular form of knowledge; and professora - the female form of professor, a male teacher.

3 The same problem occurred with the indigenous in the Northeast in the processes of recognition and self-assignment of their identities (Oliveira, 2011).

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior [Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel](Capes), Finance Code 001, the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico [National Council for Scientific and Technological Development] (CNPq), Bolsa PQ, and the Programa Cientista do Nosso Estado (CNE)/Faperj (proc. 281651).

Received: August 23, 2022; Accepted: December 12, 2022

texto en

texto en