Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.53 São Paulo 2023 Epub 13-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980531410255

HIGHER EDUCATION, PROFESSIONS, WORK

GENDER INEQUALITIES IN LEGAL OCCUPATIONS

IFundação Getulio Vargas (FGV), Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil;

The present article seeks to analyze empirically how the educational effect of women in higher education Law courses affects their insertion into the formal labor market. To achieve this goal, we used data from the Relação Anual de Informações Sociais [Annual Social Information Report] (RAIS) to analyze all occupational fields that require legal training. The data show that women were already the majority as court clerks and the like, and became the majority in private law from 2010 onwards. As for the income received, controlled by other variables, women tend to earn less than men in the same occupations, with higher incomes only among public prosecutors and lawyers.

Key words: LEGAL LABOR MARKET; GENDER RELATIONS; PROFESSIONALISM

Este artigo busca analisar empiricamente como o efeito educacional de mulheres nos cursos superiores de Direito afeta sua inserção no mercado de trabalho formal. Para dar conta desse objetivo, utilizamos dados da Relação Anual de Informações Sociais (Rais) para analisar todas as famílias ocupacionais que exigem formação jurídica. Os dados demonstram que mulheres já eram maioria como serventuárias de justiça e afins e tornaram-se maioria na advocacia privada a partir de 2010. Quanto à renda recebida, controlada por outras variáveis, mulheres tendem a receber menos do que homens nas mesmas ocupações, tendo rendimentos maiores apenas entre procuradoras e advogadas públicas.

Palavras-Chave: MERCADO DE TRABALHO JURÍDICO; RELAÇÕES DE GÊNERO; PROFISSIONALISMO

Este artículo busca analizar empíricamente cómo el efecto educativo de las mujeres en los cursos superiores de Derecho afecta su inserción en el mercado de trabajo formal. Para lograr este objetivo, utilizamos datos de la Relação Anual de Informações Sociais [Relación Anual de Informaciones Sociales] (Rais) para analizar todas las familias ocupacionales que exigen formación jurídica. Los datos muestran que las mujeres ya eran mayoría como secretarias judiciales y afines, y pasaron a ser mayoría en el derecho privado a partir de 2010. En cuanto a los ingresos recibidos, controlados por otras variables, las mujeres tienden a recibir menos que los hombres en las mismas ocupaciones, teniendo mayores ingresos sólo entre fiscales y abogadas públicas.

Palabras-clave: MERCADO LABORAL LEGAL; RELACIONES DE GÉNERO; PROFESIONALIDAD

Cet article cherche à analyser empiriquement comment l’effet de l’éducation des femmes étudiant le droit à l’université affecte leur insertion dans le marché du travail formel. A ce fin, nous avons utilisé des données provenant du Relação Anual de Informações Sociais [Rapport Annuel d’Informations Sociales] (Rais) afin d’analyser les groupes professionnels pour lesquels une formation juridique est requise. Les données montrent que les femmes représentaient déjà la majorité au ministère public de justice et autres postes de même niveau et qu’elles sont aussi devenues majoritaires dans les cabinets privés depuis 2010. En ce qui concerne les revenus, contrôlés par d’autres variables, les résultats montrent que les femmes ont tendance à recevoir moins que les hommes occupant les mêmes postes. Des revenus plus élevés chez les femmes ne concernent que les procureures et les défenseures publiques.

Key words: MARCHÉ; DE L’EMPLOI JURIDIQUE; RELATIONS DE GENRE; PROFESSIONNALISME

WITH THE STRONG EXPANSION OF BRAZILIAN HIGHER EDUCATION IN THE 2000S, Law courses, which were offered by just over 589 institutions in 20021 saw this number jump to 1,624 in 2020, reaching around 14% of total enrollment alone2 and surpassing courses that had more entrants, such as Business Administration and Pedagogy. This was largely due to the process of institutionalization of legal fields, especially since the 1988 Federal Constitution, when legal actors were able to regulate various state careers as belonging to professionals with a law degree, as well as due to the expansion of the private legal services market.

However, although both training and the market for legal professions have expanded, how do the dynamics between training and the job market work? How does the job market absorb Law graduates? Are women, who have become the majority in these courses, gaining more space and income in this market? These are some of the central questions that we will try to answer throughout this work.

Studies on professions/occupations in general seek to understand how professions in capitalist societies structure and command the actions of individuals (Barbosa, 1993). The sociology of the legal professions, in particular, is a field that has been widely explored in Brazil (Almeida, 2014; Bonelli et al., 2017; Bonelli & Oliveira, 2003), and has to some extent taken into account many of the concerns we raise here. However, most of these analyses focus on case studies of private sectors of the legal profession or specific courts, leaving a gap in empirical research that mainly seeks to understand the impact of legal occupations more generally.

Our aim here is to take a longer-term approach, seeking to assess how the population of this occupational sector is distributed in the formal market. To do this, we will use data from the Relação Anual de Informações Sociais [Annual Social Information Report] (RAIS) from 2002 to 2020 to try to capture the effect of the expansion of legal education on the dynamics of the labor market in this field.

In order to meet our objectives, in the next section we try to provide an overview of the literature dealing with the legal professions and inequalities in access to careers in the field. We then explain the methods, variables and data used to achieve our objectives. Finally, we conclude with some considerations and future directions for study in the field.

Legal professions and gender inequalities

Many studies have pointed to the trend, since the mid-2000s, of the predominance of women in higher education in Law and in the legal labor market (mainly in the field of private practice) in Brazil (Barbalho, 2008; Bertolin, 2017; Bonelli et al., 2008; Kahwage & Severi, 2019). In general, these studies seek to analyze how the transformations of a career, which until the mid-twentieth century was fundamentally male, tend to generate or maintain patterns of behavior based on the attitudes of the “founders” of the profession.

These discussions question aspects of the world of work based on a certain idea of meritocracy, which is based on a neutral “value”, when in fact it is a factor that tends to favor certain types of behavior, generally male. A meritocratic system, understood as one that rewards individuals for their individual performance, regardless of other factors such as class, race, gender, etc., although it is the most desirable, needs very clear rules and accountability to avoid choice bias. Empirical studies, however, have shown that even when performance reward policies are adopted, gender, race and nationality inequalities persist (Castilla, 2008) and that generational cohorts and employee mobility must be observed to explain these inequalities (Philips, 2005), which shows that the arrival of new players in the professions alone cannot change the status quo in the short and medium term.

In Brazil, empirical research has focused more on case studies of state courts and the market prospects of lawyers trained by specific states. An important study in this regard is that by Bonelli et al. (2008), which evaluates gender-related differences in perceptions of professionalism among young lawyers in the state of São Paulo. The authors assess that, in the state of São Paulo, “the impact of the professional ethos on gender is more pronounced than the effects of women on professionalism, mainly because the participation of female lawyers is repressed in the less prestigious and powerful positions in the career” (Bonelli et al., 2008, p. 282, own translation). The observed numerical expansion would be an important factor in reducing hostility in the professional sphere.

On the other hand, Bertolin (2017), also in a study of law firms in the state of São Paulo, says that there is a so-called “glass ceiling” that prevents women from reaching the highest positions in law firms, since they hold associate or employee positions in almost 49% of the firms, while at the top of their careers (partners) they don’t even reach 30%. In the author’s opinion, there has been no adaptation between the massive influx of women into this market and the fact that most of them are still responsible for taking care of domestic matters.

In research that focuses on legal careers in the public sector, there is also a trend towards case studies of state courts, also paying attention to the problem of inequalities in this sector which, in theory, should be guided by well-defined merit principles, since civil servants take part in public examinations and career advancement depends on length of service and merit. The idea is that, in a “normal” distribution, gender and race should not influence career advancement and bonuses.

In relation to the public sector, the careers of the Judiciary are the ones that have received the most attention, mainly because they are considered the elite occupations. Many of these studies seek to assess whether the growing number of women graduates is transformed into more representation in the judiciary (quantitative aspects) and what the impacts of this representation are, i.e. whether a greater number of women in important positions tends to generate decisions based on gender (qualitative aspects).

Fragale et al. (2015), analyzing the quantitative impacts of the arrival of women at the top of the Judiciary, assess that, within the institutional rules of the judicial organization, it would only be a matter of time before more women entered these summits. However, even if this quantitative leap were practically “certain”, the judiciary would not necessarily have a tendency towards qualitative gains with women’s interests being represented there. What would actually happen is that, in order to remain in key positions, women would have to adopt the male modus operandi.

Still in relation to the intrinsic inequality of a male-dominated environment, changes that tend to improve representation can cause distortions. In a study using data from the Conselho Nacional de Justiça [National Council of Justice] (CNJ), Bonelli and Oliveira (2023) show that quota policies have led to a slight increase in male representation, as Black and brown men are more likely to enter reserved vacancies than Black and brown women. This, in turn, leads to the problem of looking more closely at the need for intersectional policies in relation to these markers.

Although the number of women in the judiciary has been getting closer to the number of men, there is a negative correlation between hierarchy and gender: the higher the position, the fewer women there are (Severi, 2016, p. 85). On the side of studies into the possible qualitative change in the Judiciary with more women magistrates, Severi (2016) points to the fact that the more heterogeneous the functional composition of the judiciary, the greater the likelihood of a justice system that is more sensitive to the human rights agenda. Achieving this heterogeneity would require a more direct policy from the courts to adopt gender parity in higher bodies and racial quotas for access to the judiciary.

The only work to our knowledge that has empirical pretensions and addresses the legal labor market in a more general way is that of Campos and Benedetto (2021). The authors analyze, through the Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua [Continuous National Household Sample Survey] (Continuous PNAD) of the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics] (IBGE), data on legal occupations between the first quarters of 2015 and 2020, selecting professionals whose main occupation is: i) lawyers (generalists or specialists, working in any field); ii) legal advisors (ditto); iii) members of the judiciary (judges, justices and ministers); iv) members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office (prosecutors and attorneys); v) members of the Public Defender’s Office (public defenders); vi) members of the public attorney’s offices (federal, state, municipal attorneys - of all kinds); and vii) judicial police delegates (state or federal). The study indicates the high relevance of this job market, even though the number of graduates is much higher than the number of people working, as well as the great differences in earnings in the sector, depending on variables such as urbanization, working in the public or private sector, gender and race. The study also shows that a large proportion of these professionals (59%) are not salaried, due to the specific nature of the legal professions as a liberal sector.3

However, despite representing a substantial gain, the study deals with labor market data in aggregate form, failing to show the differences between occupational sectors, income inequality between these sectors and the different impacts of sociodemographic variables on occupations.

Our intention here is precisely to broaden the occupational sectors (also including legal servants and the like) and assess how socio-demographic differences are distributed within these sectors, evaluating their impact on income by variables such as gender, age and region of the country.

Below we will briefly discuss the methodological option of using the RAIS in this first part of the investigation into the legal labor market.

Methodological discussion

Brazil currently has excellent data sources for analyzing the labor market, such as IBGE data (mainly censuses and sample surveys) and data from the Ministério da Economia [Ministry of Economy] - RAIS and Cadastro Geral de Empregados e Desempregados [General Register of Employed and Unemployed] (CAGED). All of these bases have important contributions and certain limitations.

The Continuous PNAD has the advantage of being comprehensive in its analysis, since it defines formal workers as all those who are: employees in the private sector with a formal contract; employees in the public sector with a formal contract; employers with a CNPJ; and self-employed workers with a CNPJ. For the purposes of analyzing a market as fluid as the legal market, the Continuous PNAD is undoubtedly an excellent option. However, the survey has an initial limitation, which is that it is still a recent series (it began in 2012), and that only from the 4th quarter of 2015 did it begin to differentiate self-employed workers between those who had or did not have a CNPJ, which is crucial for understanding the formality of work. In the future, we will try to build a classification to specifically evaluate the private legal market based on the Continuous PNAD in order to assess its distinction from the RAIS data.

The advantage of the RAIS is that it aggregates data on the population stock of the formal labor market, collecting mainly information on employers every year since 1985. For our analysis, we will consider legal careers from 2002 to 2020 and address a gap in gender inequalities in this field by assessing how the various legal occupations include graduates and their income differences in both the private and public sectors. The main limitation of the RAIS for assessing the legal labor market is that this database specifically assesses legal entities or individuals who have at least one registered employee. As the private legal labor, market is often marked by lawyers who are self-employed and do not have a formal contract, analyzing only the formal sector certainly underestimates the sector’s data to a certain extent. In other words, the RAIS data does not capture the “informality” of the sector or its total formality, since it does not include self-employed workers who have a CNPJ. Another point is that the RAIS, despite being a good “portrait” of the formal sector, is a stock base, showing little of the flow (job losses and gains) that occurs with occupations over the course of a given year.

As already mentioned, any methodological choice implies losses and gains. As our aim is to look at a broader historical series, we understand that the RAIS data can be an important starting point for future studies that seek to evaluate and build comparative measures between these and the Continuous PNAD sample data.

Data and methods

Changes in higher education in Law

As indicated above, the 2000s were accompanied by an expansion in the education system, which was very representative in the area of Law, which arrived in 2020 as the course with the highest number of enrolments (759,328, representing 13.6% of total enrolments), entrants (221,611, or 12.6% of entrants) and graduates (124,438, or 14.1% of total graduates).4

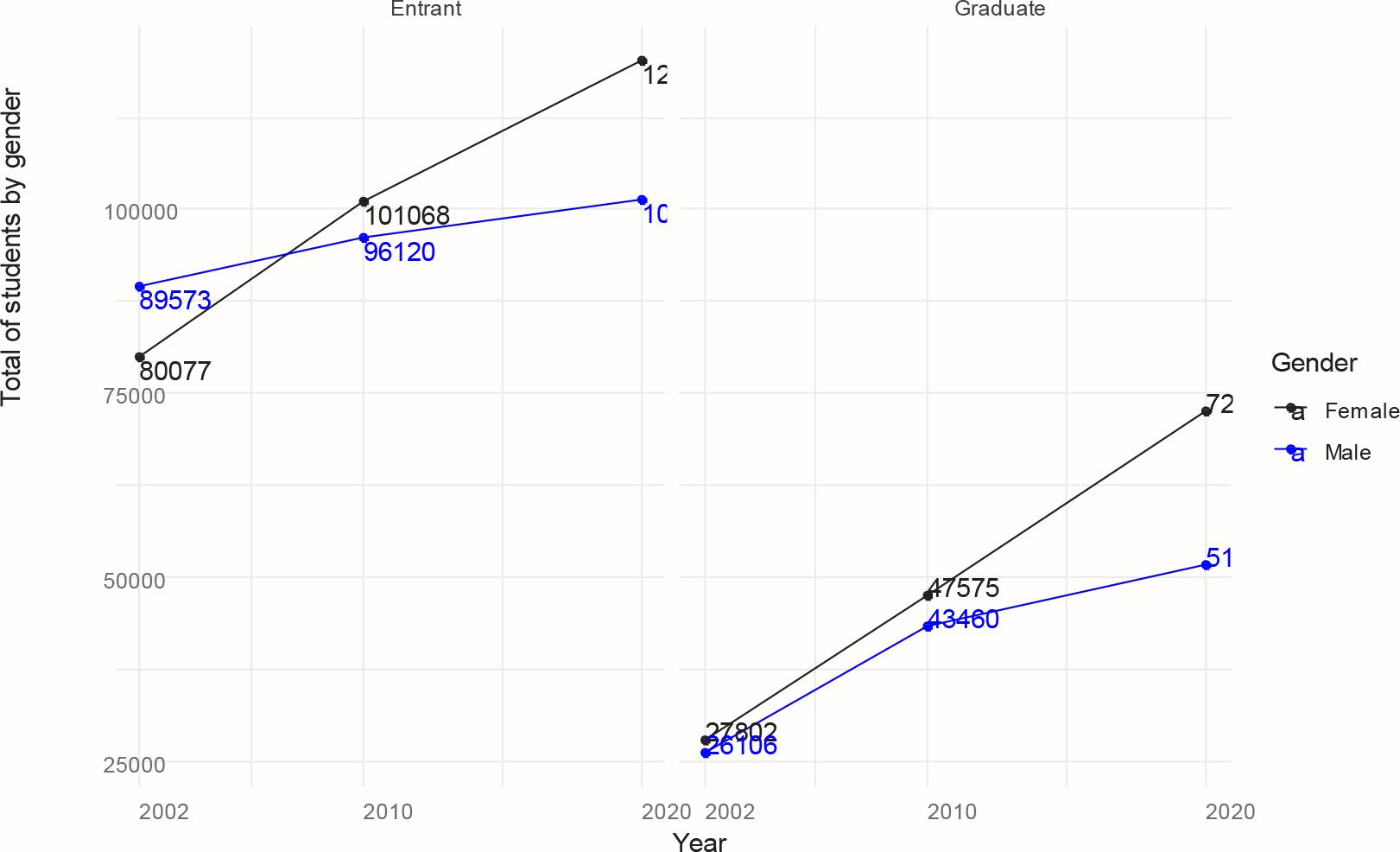

This substantial increase in the number of students on Law courses has led to a massive influx of women into the field, making them the biggest entrants and the biggest leavers. Figure 1 shows how this has happened.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on data from Censo da Educação Superior.

Figure 1 Law course entrants and graduates by gender (2002/2010/2020)

In 2002, men were still in the majority among entrants (52.8%), although women were already outnumbered among graduates5 (51.5%). This gap has widened substantially over time, with women accounting for 54% of entrants and 58.4% of completers in 2020, while men accounted for 45.7% and 41.6% respectively. The data indicates that women tend to dominate this field more and more.

How does this dynamic of a reversal in the number of more women on these courses reflect on the job market in the legal professions? As already mentioned, the point we’re trying to understand is whether the quantitative leap demonstrates qualitative gender gains in this market, with greater salary and occupational equality for the professionals who are now in greater numbers.

These are some of the points we will try to address in the next topic.

The formal job market in the legal sector

To work with the data on legal occupations, we selected from the RAIS, based on the occupational families in the Classificação Brasileira de Ocupações [Brazilian Classification of Occupations] (CBO/2002),6 all the occupations that require higher education in Law: lawyers working in the private sector; public prosecutors and lawyers; police officers (district, regional and federal); members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office; magistrates and court clerks and the like. Only those with active employment on December 31st of each year and who had completed higher education were included in the analysis.7

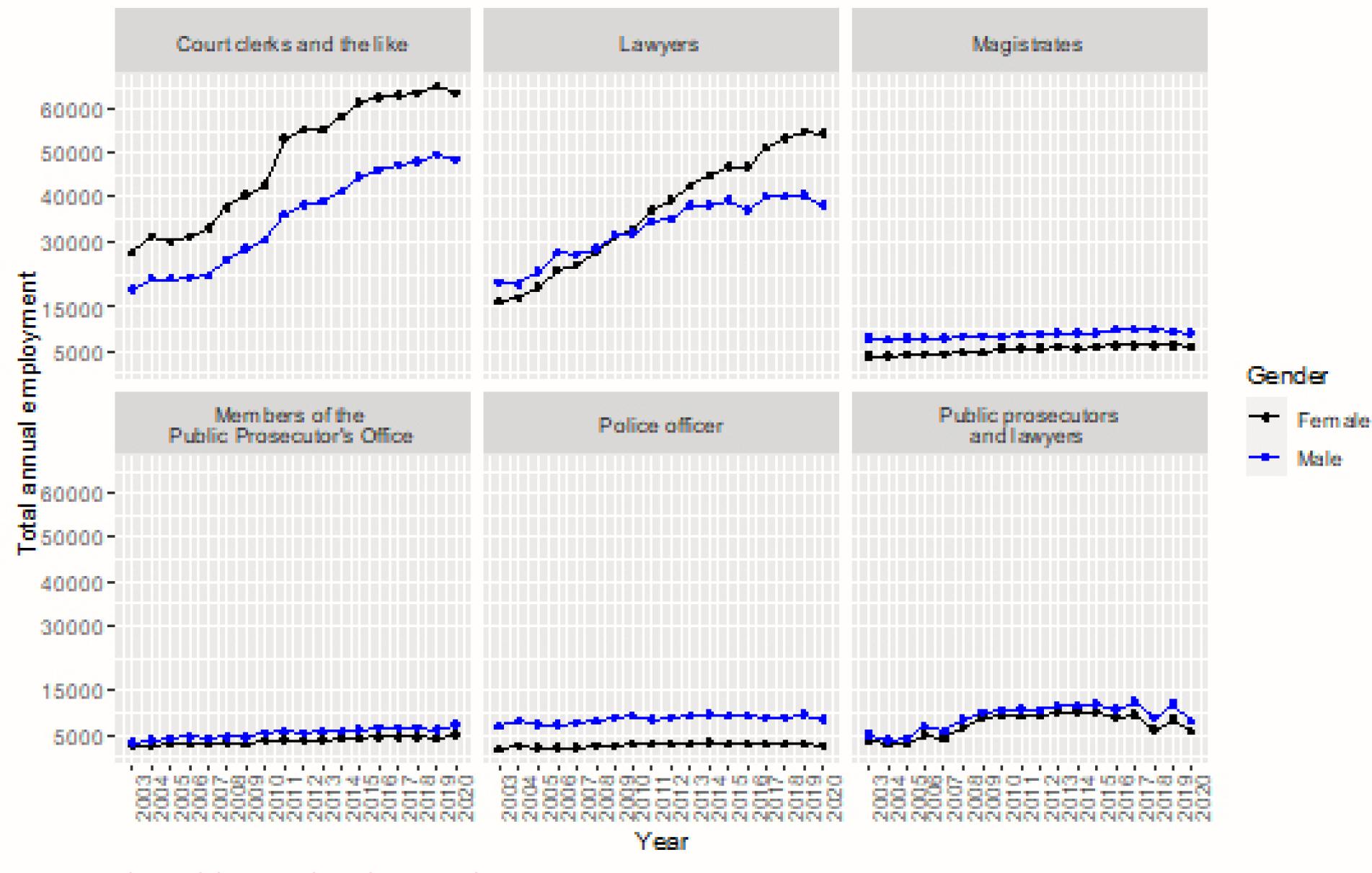

As can be seen in Figure 2, the legal job market is quite broad and has continued to grow steadily, with a few downturns mainly in 2016, in the private lawyer market, and from 2017 onwards, especially among public prosecutors and lawyers. But even so, in relation to the labor market as a whole, where job losses averaged over 10% between 2014 and 2020, job losses in specific legal positions were not as significant. Small retractions at times were followed by relative increases.

Another important point to note is the gender differences in this market. With regard to lawyers, women began to almost match men in jobs from 2008, overtaking them from 2010 and becoming a massive presence in private sector careers. The number of lawyers in the private sector reached 93,000/94,000 in the formal sector in 2020. Once again, it is important to emphasize that these figures refer exclusively to jobs with a formal contract, and there is certainly an underestimation of the total number of professionals in the private sector who work with a CNPJ or not. According to data from the Ordem dos Advogados do Brasil [Order of Attorneys of Brazil] (OAB) data, there are currently 1,303,016 lawyers registered8 with the Order, which shows to some extent that a large part of the professionals in this field are not in the formal labor market with a formal contract, but rather in the formal market with their own CNPJ or in the informal market as classified by the IBGE.9

Source: Author’s elaboration based on RAIS data.

Figure 2 Total annual employment by occupational family and gender (2003-2020)

Among court clerks, women were already in the majority in 2003 and have continued to grow in relation to men. This is something that needs to be looked at more closely because, as these are public sector occupations, there is a tendency to maintain a certain stability, although the occupation of court clerks had the largest total increase. The stability in the public sector by gender is also true for the other occupations, although to a lesser extent; there was a slight increase in the total number of jobs among all occupational families, while the difference between men and women remained stable. The most notable difference is among police officers, whose male workforce is much larger than their female counterparts.

It is interesting to note that the internal movement of disputes between actors in the justice system mentioned by Arantes and Moreira (2019) can be assessed within this framework. According to the authors, state pluralism “therefore portrays the institutional development resulting from the struggle of state actors for institutional affirmation, which results in the pluralization of the intra-state structure” (p. 104, own translation). In other words, the internal dispute between state actors for institutional self-affirmation within certain specific “fits”, in which these actors managed to insert themselves as fundamental agents, was fundamental for legal actors to gain a foothold in state careers. These frameworks are generally related to the expansion of access to justice, with each branch of the judicial system struggling to establish and expand its own boundaries. The data points to a certain efficiency on the part of these actors in inserting their careers as key points in state careers, which calls for further studies to assess whether the expansion of these careers has translated into more effective access to justice.

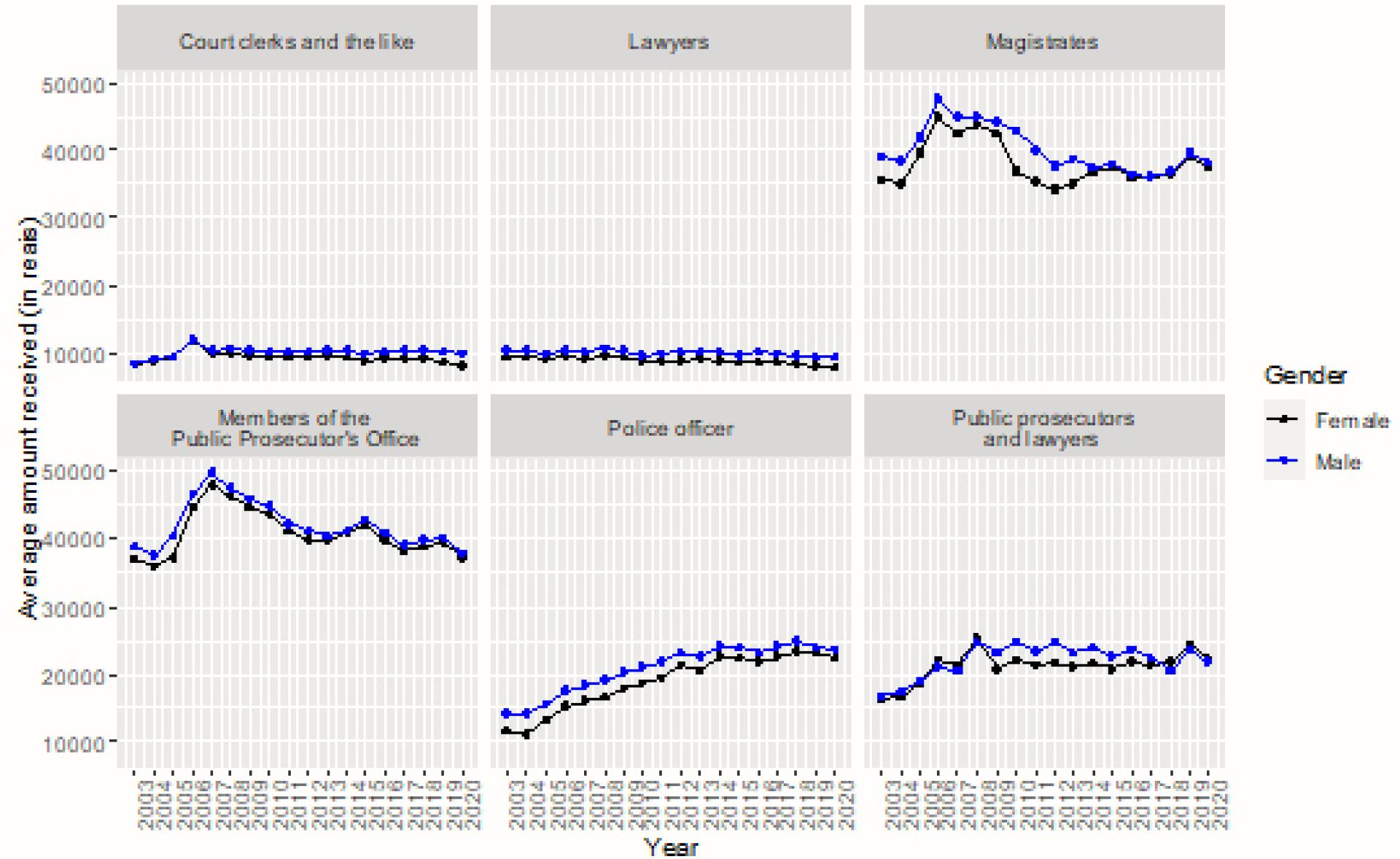

Another fundamental point for analyzing the data on legal careers is related to the amounts received in these occupations and how they differ by gender. Figure 3 details the average income by occupational family and gender.

In general, there was a slight reduction in the averages received mainly by lawyers, members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and judges. Among the latter two, the figures have stabilized. Police chiefs had the best gains in average income over time, while there was some stability for public prosecutors and lawyers and court clerks. In this last occupation, it is worth noting that the average losses were greater among women than men, with salaries almost identical at the start of the series and then diverging to some extent over time. The relationship in this field is reversed: women are in the majority among civil servants, but earn less over time.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on RAIS data.

Figure 3 Average amount received,10 by occupational category and gender (deflated by the INPC of December 2020)

It’s interesting to note that when we look at earnings, the figures in the graph practically reverse in relation to gender, although over time they tend to become more equal. Even in public careers where greater gender pay equality is assumed, there are certain differences that we will test later to see if they are statistically significant.

First, however, it is important to assess how income is distributed across occupational families, since average values tend to include extreme values, showing very little about overall inequality within careers. In Table 1 we list the main income deciles by occupational family and gender to try to visualize how intra-career income distribution occurs.

Table 1 Income decisions by occupational family and gender

| Ocupation | Gender | decile_1 | decile_2 | decile_3 | decile_4 | decile_5 | decile_6 | decile_7 | deciel_8 | decile_9 | decile_10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawyers | female | 2046,2 | 3003 | 3957,2 | 4977,5 | 6254,1 | 7749 | 9803,8 | 13156,9 | 18815,2 | 156293,4 |

| male | 2072,5 | 3168 | 4225,8 | 5464,7 | 6898,2 | 8765,3 | 11384,1 | 15186,2 | 21672,2 | 156641 | |

| Police officer | female | 9263,2 | 11765,2 | 13956,3 | 16333,5 | 18619,2 | 20866,2 | 23421,9 | 26497,1 | 31158,2 | 75264,6 |

| male | 10586,2 | 13279,5 | 15740 | 18006,8 | 20265,4 | 22519,8 | 25017,1 | 28215,7 | 33435,7 | 87638,7 | |

| Magistrates | female | 29588,8 | 32560,1 | 33876,7 | 35441,4 | 36947,8 | 38959,4 | 40989,9 | 43831,4 | 49530,1 | 159974,4 |

| male | 30983,6 | 33669,3 | 35252,3 | 36678,7 | 38545,8 | 40661,1 | 43105,3 | 46968,8 | 53929 | 159776,2 | |

| Members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office | female | 30671,3 | 33576 | 35142,5 | 36678,7 | 38742,5 | 40919,9 | 43673,9 | 47922,2 | 54976,9 | 148276,8 |

| male | 31338,1 | 33689,1 | 35504,2 | 37576,4 | 39672,5 | 41890,5 | 45418,2 | 50200,6 | 57605,5 | 148968,2 | |

| Public prosecutors and lawyers |

female | 4014 | 5599,4 | 9656 | 16158,5 | 23157,5 | 27138 | 29970,1 | 33895,5 | 38388 | 130826,7 |

| male | 4128,9 | 6773,9 | 11177,3 | 19060,9 | 24871,5 | 27913,1 | 30932,8 | 35236,4 | 39345,7 | 126369,7 | |

| Court clerks and the like | female | 1469,5 | 2636,2 | 4730,1 | 6333,6 | 7782,2 | 9382,5 | 11456,8 | 14339,5 | 19415,1 | 155011 |

| male | 1695,9 | 3432,9 | 5492,3 | 6883,4 | 8456,7 | 10277,6 | 12599,7 | 15616,7 | 20692,2 | 149985,7 |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on RAIS data.

In all occupations, the median income (5th decile) is higher for men than for women. The median income for lawyers was around six minimum wages,11 which shows that the formal legal sector guarantees a much higher income than the majority of the economically active population.12 This shows a very interesting scenario for professionals in this field, although, as should be noted, we are only evaluating professionals who work formally with a formal contract, and there may be a lot of variation among those who are self-employed.13

Overall, however, we believe that the market is quite solid; while much of the labor market has suffered from job losses, especially since the economic crisis of 2015 and the deepening of the economic crisis as a result of the health crisis caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus in 2020, the private legal market has not been affected as strongly as the service sector over time.

In terms of public sector occupations, police chiefs, magistrates and members of the public prosecutor’s office occupy elite positions in the sector. The first income decile of all these occupations exceeds ten minimum wages, which, in current 2020 values, places them in the group of the richest 5%, and for magistrates and members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office they are among the richest 1% of the population.14

Public prosecutors and lawyers also have incomes above the population average, with the median (5th decile) exceeding twenty minimum wages. It is interesting to note that this occupational family has a higher income for women than for men in the highest decile, with a substantial difference compared to all other occupations, as can be seen in the model in Table 2. There is greater interquartile dynamics among court clerks and the like, with the first two deciles (bottom 20%) earning between 2.5 and 3 minimum wages, with a significant increase in the third decile, but, like the class of private lawyers, more than 90% have incomes of up to 21 minimum wages, the median value for all other occupations.

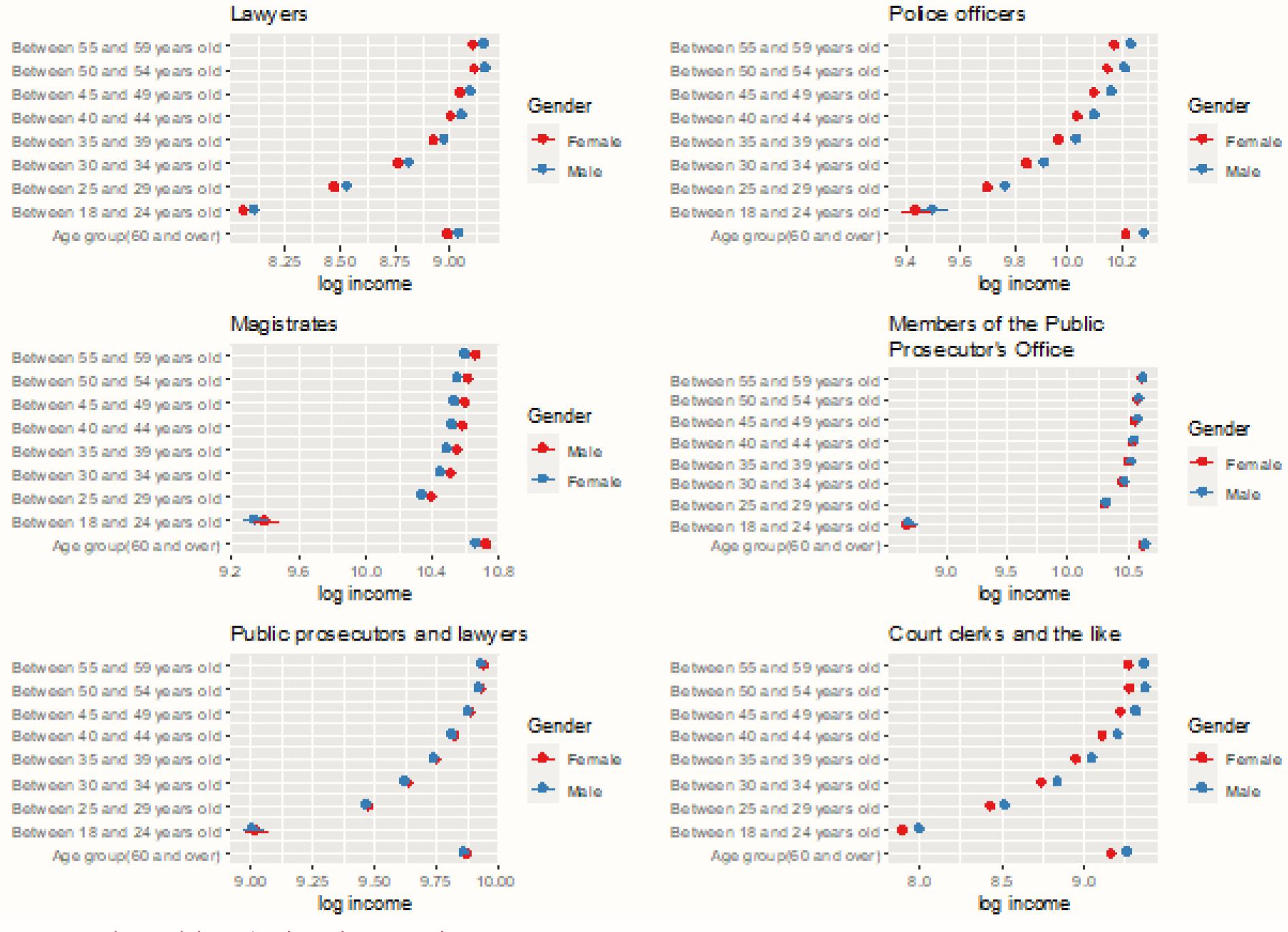

As is clear, in all occupations the amounts received by women are lower than those received by men (except in the last decile highlighted in red in Table 1). Our intention is to evaluate, using linear regression models, the variables that affect the income received (dependent variable), in order to understand whether the differences in the amounts received by occupational class are statistically significant, controlling for other variables such as age and region of the country, in addition to gender.

Table 2 Results of linear regression models by occupational family

| Dependent variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_income | ||||||

| Lawyers | Police officers | Magistrates | Members of the PPO | Public prosec. and lawyers | Court clerks and the like | |

| Gender (female) | ||||||

| Male | 0,050*** | 0,064*** | 0,063*** | 0,013*** | -0,012*** | 0,095*** |

| (0,001) | (0,002) | (0,002) | (0,002) | (0,003) | (0,001) | |

| Age group (60 and over) |

||||||

| Between 18 and 24 years old | -0,927*** | -0,787*** | -1,323*** | -1,952*** | -0,855*** | -1,266*** |

| (0,005) | (0,026) | (0,037) | (0,026) | (0,022) | (0,006) | |

| Between 25 and 29 years old | -0,512*** | -0,518*** | -0,321*** | -0,323*** | -0,396*** | -0,740*** |

| (0,004) | (0,006) | (0,005) | (0,005) | (0,007) | (0,003) | |

| Between 30 and 34 years old | -0,228*** | -0,369*** | -0,212*** | -0,171*** | -0,237*** | -0,427*** |

| (0,004) | (0,004) | (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,007) | (0,003) | |

| Between 35 and 39 years old | -0,063*** | -0,253*** | -0,170*** | -0,120*** | -0,123*** | -0,217*** |

| (0,004) | (0,004) | (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,007) | (0,003) | |

| Between 40 and 44 years old | 0,013*** | -0,182*** | -0,138*** | -0,091*** | -0,048*** | -0,055*** |

| (0,004) | (0,004) | (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,007) | (0,003) | |

| Between 45 and 49 years old | 0,056*** | -0,121*** | -0,127*** | -0,067*** | 0,018*** | 0,055*** |

| (0,004) | (0,004) | (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,007) | (0,003) | |

| Between 50 and 54 years old | 0,122*** | -0,069*** | -0,108*** | -0,050*** | 0,059*** | 0,111*** |

| (0,005) | (0,004) | (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,007) | (0,003) | |

| Between 55 and 59 years old | 0,117*** | -0,046*** | -0,059*** | -0,016*** | 0,068*** | 0,106*** |

| (0,005) | (0,005) | (0,004) | (0,005) | (0,008) | (0,003) | |

| Region (South) | ||||||

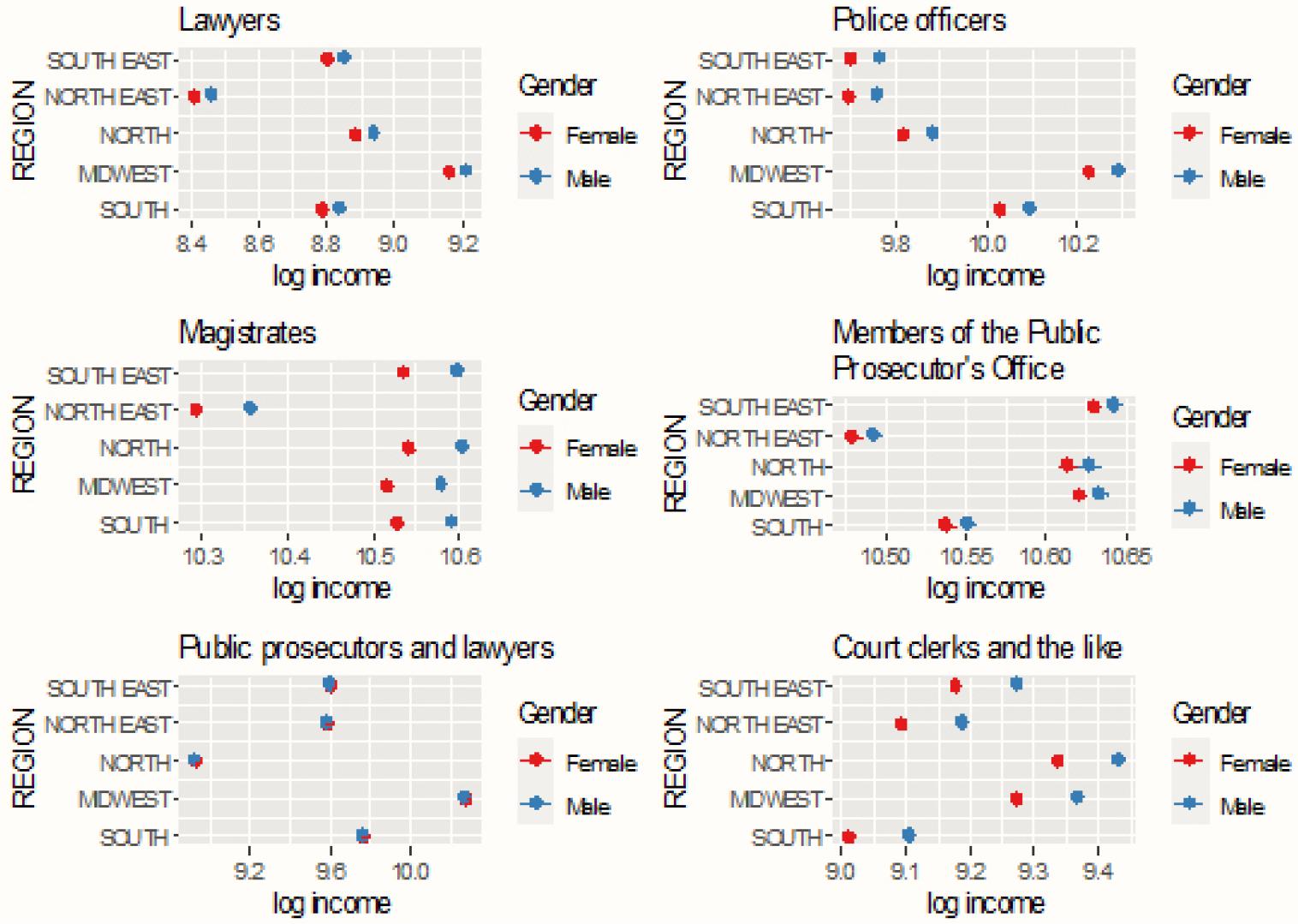

| North | 0,371*** | 0,194*** | -0,012*** | 0,082*** | 0,513*** | 0,263*** |

| (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,003) | (0,003) | (0,005) | (0,002) | |

| Midwest | -0,376*** | -0,336*** | -0,236*** | -0,058*** | -0,181*** | 0,082*** |

| (0,003) | (0,003) | (0,003) | (0,003) | (0,006) | (0,002) | |

| North East | 0,100*** | -0,213*** | 0,013*** | 0,076*** | -0,840*** | 0,325*** |

| (0,004) | (0,004) | (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,006) | (0,003) | |

| South East | 0,016*** | -0,330*** | 0,008*** | 0,092*** | -0,163*** | 0,167*** |

| (0,002) | (0,003) | (0,002) | (0,003) | (0,005) | (0,002) | |

| Constant | 8,991*** | 10,221*** | 10,662*** | 10,637*** | 9,876*** | 9,168*** |

| (0,004) | (0,005) | (0,003) | (0,004) | (0,007) | (0,003) | |

| Observations | 1.225.997 | 196.108 | 247.968 | 156.025 | 286.758 | 1.477.437 |

| R2 | 0,145 | 0,204 | 0,081 | 0,088 | 0,262 | 0,163 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0,145 | 0,204 | 0,081 | 0,088 | 0,262 | 0,163 |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on RAIS data.

Note:

*p < 0,1;

**p < 0,05;

***p < 0,01. Reference categories in parentheses.

The model data confirms that gender is an important and statistically significant predictive variable in all occupations. Being a man increases the likelihood of having higher incomes in all occupations, except among public prosecutors and lawyers, the only occupational family in which the wage gap for women is greater. In general, being a man increases income by 0.05 compared to women. As for the profession of public prosecutors and lawyers, women increase their earnings by 0.01 compared to men. Although the differences are not so great, gender is an important predictor of income.

To analyze the effect of age, we divided the groups into age groups (established by the RAIS) to assess possible differences between the different age strata. We used this feature mainly because considering only age as a continuous number tends to generate a bias, since, in general, age is highly correlated with income. By analyzing the age groups, we can see if there are important intra-age group differences. In relation to the reference category, the age groups between 18 and 39 in the group of lawyers are negatively affected; the younger they are, the lower their income. Among those aged 40 to 59, the opposite is true; the income received increases as the age group advances. Among delegates, magistrates and members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, all age groups tend to earn less than the group aged 60 or over. For prosecutors and civil servants, something similar occurs to the group of lawyers, but from an older age group, among those aged 45 to 59, income levels tend to increase in relation to the group aged 60 or over.

This is a variable that, when considered in conjunction with gender, can answer to some extent why the averages received by men are higher in most occupations; although women are in the majority in the market today, this “turnaround” has taken place over the last 10 years. Therefore, the cohort of men who were already entering the market in the 1980s and 1990s tends to benefit the most. This means that most women are younger than men. Women tend to be in the majority in the 18-49 age brackets, while in the 50 and over age brackets men are in the majority, which explains to some extent the higher relative gains than those of women.

With the massive entry of women into the legal job market in the 2000s, the tendency is that, with more experience, these women will gain ground in occupational fields over time, reducing the impact of wage inequalities in relation to men.

Finally, private lawyers, magistrates, members of the public prosecutor’s office and court clerks in the North have higher incomes compared to the same occupations in the South, while delegates and public prosecutors go in the opposite direction. In the Midwest region, with the sole exception of magistrates, all occupations have higher earnings than in the South. In the Northeast, only court clerks have higher earnings compared to their counterparts in the South. All other occupations tend to earn less than in the South. In the Southeast, police chiefs and public prosecutors earn less when compared to the South, while in the other occupations the opposite is true.

As you can see, the diversity that exists in terms of gender, age and region directly affects the dynamics of this market and, above all, the earnings obtained by the profession, demonstrating that, although in the medium term there will be a greater inclusion of women in legal occupations, the formal labor market is still marked by variables that tend to change more slowly in the long term.

Final considerations

This work focused, in an initial effort, on the formal legal labor market, trying to add to the empirical efforts already mentioned above in order to provide a broader account of the legal labor market, its distribution of vacancies in the formal market and its internal inequalities related not only to gender, but also to the region of the country and the age of the professionals. Because a substantial part of this formal sector is more included in state careers, especially in the sector’s elite occupations, its dynamics are very important for assessing how the growth of these segments in the public sector actually impacts on greater access to justice and accountability on the part of these professionals. What’s more, it’s important to assess in the future whether this dynamic is due to society’s need for more justice services or just the corporate demand of legal sectors that are heavily embedded in state dynamics.

The changes that have taken place in legal professions/occupations have been quite significant in recent years. More and more women have become the majority in higher education courses and have consequently gained positions in this job market. As the legal professions, especially those linked to the career of the State, are generally the most prestigious for university graduates, greater heterogeneity in their careers tends to reduce gender inequalities in the labor market in general.

Although the market is unable to absorb all law graduates, we can adopt the perspectives put forward by Campos and Benedetto (2021) who summarize that, from a pessimistic point of view, the mismatch between graduates and employees could be the result of both an “overproduction” of law graduates and a mismatch between the content taught and what the market expects. From the optimistic viewpoint, the authors point to the fact that the curriculum for law graduates would be broad enough for graduates in this field to be absorbed by other areas of activity than specifically legal ones (Campos & Benedetto, 2021, p. 22).

There has been a certain stability in formal jobs in the legal field over time, which shows a certain solidity in this market. Over time, careers in general have seen significant annual growth, especially in the occupations of lawyers in the private sector, police officers and court clerks. Interestingly, among the former and the latter, women have gained or remained in greater numbers over time, with only the group of police officers maintaining a certain greater stability of men over time.

As in general most of these professions correspond to state careers and maintain the salaries of the elite of the public administration, what we see is that the legal sector manages to sustain itself over time as an important actor in the state structure, expanding its range of activities to professions that became more institutionalized after the 1988 Federal Constitution (among them mainly the members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and public prosecutors and lawyers). Nevertheless, interestingly, as Arantes and Moreira (2019) show, this “pluralization” of state-legal agents was due more to corporate reasons within the careers than to a specific constitutional order of real need for access to justice.

However, although career advancement and better earnings should be more associated with aspects of the merits of the professionals’ work, we see that inequalities of gender, age and the region in which professionals work are still important variables that act as markers in maintaining inequalities.

Our proposal for a future research agenda is to assess how this job market fluctuates, to analyze the level of average earnings also among informal sectors and among those who do not have a formal contract, and to observe how new technologies have impacted this sector (software for building and managing cases, online offices and cases, use of big data to assess the likelihood of a court decision, etc.). All these issues are points that are already increasingly on the daily agenda in professions in general and consequently in the lives of legal professionals, but the point is still to know how much of the lives of these professionals tend to take on the contours of “uberization” that is already occurring in various occupational sectors, especially those that require less technique and consequently fewer years of study.

From the point of view of the formal market, the sector remains firm in the face of possible flexibilization in other economic sectors. However, once again it is important to point out that, as a liberal profession, this is a very heterogeneous sector that needs an even closer look to understand possible changes and continuities in its dynamics.

REFERENCES

Almeida, F. de. (2014). As elites da justiça: Instituições, profissões e poder na política da justiça brasileira. Revista de Sociologia e Política, 22(52), 77-95. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-987314225206 [ Links ]

Arantes, R. B., & Moreira, T. M. Q. (2019). Democracia, instituições de controle e justiça sob a ótica do pluralismo estatal. Revista Opinião Pública, 25(1), 97-135. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-0191201925197 [ Links ]

Barbalho, R. M. (2008). A feminização das carreiras jurídicas e seus reflexos no profissionalismo [Tese de doutorado, Universidade Federal de São Carlos]. Repositório Institucional da UFSCar. https://repositorio.ufscar.br/bitstream/handle/ufscar/6663/2026.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

Barbosa, M. L. (1993). A Sociologia das profissões: Em torno da legitimidade de um objeto. BIB - Revista Brasileira de Informação Bibliográfica em Ciências Sociais, 36(1), 3-30. [ Links ]

Bertolin, P. T. M. (2017). Feminização da advocacia e ascensão das mulheres nas sociedades de advogados. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 47(163), 16-42. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053143656 [ Links ]

Bonelli, M. da G., Cunha, L. G., Oliveira, F. L. de, & Silveira, M. N. B. (2008). Profissionalização por gênero em escritórios paulistas de advocacia. Tempo Social, 20(1), 265-290. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-20702008000100013 [ Links ]

Bonelli, M. da G., Nunes, J. H., & Mick, J. (2017). Ocupações e profissões na Sociedade Brasileira de Sociologia: Balanço da produção (2003-2017). Revista Brasileira de Sociologia, 5(11), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.20336/rbs.219 [ Links ]

Bonelli, M. da G., & Oliveira, F. L. de. (2003). A política das profissões jurídicas: Autonomia em relação ao mercado, ao Estado e ao cliente. Revista de Ciências Sociais, 34(1), 99-114. [ Links ]

Bonelli, M. da G., & Oliveira, F. L. de. (2023). Changes in gender and race composition of the Brazilian Judiciary. Oñati Socio-Legal Series, 13(4), 1351-1375. https://doi.org/10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1394 [ Links ]

Campos, A. G., & Benedetto, R. di. (2021). Mercado de trabalho jurídico no Brasil: Qual é a situação atual? [Texto para Discussão, 2714]. Ipea. https://doi.org/10.38116/td2714 [ Links ]

Castilla, E. J. (2008). Gender, race, and meritocracy in organizational careers. American Journal of Sociology, 113(6), 1479-1526. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c [ Links ]

Fragale, R., Moreira, R. S., Fo., & Sciammarella, A. P. de O. (2015). Magistratura e gênero: Um olhar sobre as mulheres nas cúpulas do Judiciário brasileiro. E-Cadernos CES, (24), 57-77. https://doi.org/10.4000/eces.1968 [ Links ]

Kahwage, T. L., & Severi, F. C. (2019). Para além de números: Uma análise dos estudos sobre a feminização da magistratura. Revista de Informação Legislativa: RIL, 56(222), 51-73. [ Links ]

Philips, D. J. (2005). Organizational genealogies and the persistence of gender inequality: The case of Silicon Valley law firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 440-472. [ Links ]

Severi, F. C. (2016). O gênero da justiça e a problemática da efetivação dos direitos humanos das mulheres. Revista Direito e Práxis, 7(13), 81-115. https://doi.org/10.12957/dep.2016.16716 [ Links ]

1 Based on microdata from Censo da Educação Superior [Brazilian Higher Education Census]: https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/dados-abertos/microdados/censo-da-educacao-superior

3 In the next section, we present our methodological choice of data from the Rais rather than the Continuous PNAD.

4 It should be remembered that we are only considering face-to-face courses. By way of comparison, the second-placed course in terms of enrollment, Business Administration, accounted for only 5.7% of the total. The second-placed course among entrants, Psychology, accounted for 6% of the total and, among graduates, Business Administration was in second place with 6.8%. As you can see, in 2020 Law courses had more than twice as many students as the second-placed course in all possible stages.

5 It would be interesting to assess why women tend to graduate more than men. We have some hypotheses that are difficult to test because, unfortunately, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira [National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira] (INEP) removed the Census microdata from its website on the grounds that it violated the new General Personal Data Protection Law.

7 Although this information may seem trivial, it is important to make the cut in the database since many court clerks did not have higher education due to the dynamics of notaries, which used to be granted by state governments and passed down from father to son.

8 Data obtained from: https://www.oab.org.br/institucionalconselhofederal/quadroadvogados. The OAB data doesn’t show flows over time, so we don’t know exactly how many applicants there were in 2020 and in previous years.

9 The IBGE classifies as formal work those who are: employed in the private sector, excluding domestic workers - with a signed work permit; employed in the public sector, excluding military personnel and statutory civil servants - with a signed work permit; employed in the public sector - military personnel and statutory civil servants; employers with a CNPJ; and self-employed with a CNPJ. Informal workers are those who do not fall into these categories, such as: employees in the private sector, excluding domestic workers - without a signed work permit; employers without a CNPJ; and self-employed without a CNPJ.

10 To calculate the average amount received, we take into account the income declared in December of each year and deflate it by the Índice Nacional de Preços ao Consumidor [National Consumer Price Index] (INPC) for December 2020. The amount received includes salaries, wages, fees, advantages, bonuses, etc., except for the 13th salary. In public careers, it is true that salary differentiation occurs through extra earnings. Unfortunately, the RAIS data is aggregated and does not make it possible to analyze income other than salaries, which would be important to know more precisely how salary differentiation occurs.

12 According to data from PNAD Contínua, in the 4th quarter of 2020, the real average income from the main job, usually received per month by people aged 14 and over, corresponded to BRL 2,885.00. Source: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/home/pnadct/brasil

Data availability statement

The data used in this article, as well as the R code for possible replication, will be publicly available through the author’s GitHub (https://github.com/deciovrocha/rais_advgados/blob/main/codigo_rais) and can also be requested via the e-mail provided on the first page.

Appendix

Source: Author’s elaboration based on RAIS data.

Figure A1 Predicted income probabilities by region and gender

Source: Author’s elaboration based on RAIS data.

Figure A2 Predicted probabilities of income by age group and gender

Table A1 Selected legal occupations, according to Classificação Brasileira de Ocupações (CBO/2002)

| Family | Family | Code | Occupation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magistrates | 1113 | 111305 | Minister of the Federal Supreme Court | They decide individual and collective disputes on behalf of the state, applying the law to concrete cases. To do this, they direct court sessions and hearings, establish criteria to promote equality between the parties, assess the need for evidence for a safe trial, decree convictions or acquittals in criminal cases, among other things; conciliate interests, listening to and summoning the parties and proposing alternative agreements; enforce compliance with decisions; approve non-conflictual situations; manage the judiciary’s administrative activities; coordinate electoral processes; carry out activities related to the judicial function and organize case law. |

| 111310 | Minister of the Superior Court of Justice | |||

| 111315 | Minister of the Superior Military Court | |||

| 111320 | Minister of the Superior Labor Court | |||

| 111325 | Judge | |||

| 111330 | Federal Judge | |||

| 111335 | Federal Auditor Judge - Military Justice | |||

| 111340 | State Auditor Judge - Military Justice | |||

| 111345 | Labor Judge | |||

| Lawyers | 2410 | 241005 241010 241015 241020 241025 241030 |

Lawyers Company lawyer Lawyer (Civil Law) Lawyer (Public Law) Lawyer (Criminal Law) Lawyer (special areas) |

They advocate on behalf of their clients in court, proposing or contesting lawsuits, requesting measures from the magistrate or the Public Prosecutor’s Office, evaluating documentary and oral evidence, holding labor, common criminal and civil hearings, instructing the party and acting in the jury court, and, extrajudicially, mediating issues, contributing to the drafting of bills, analyzing legislation for updating and implementation, assisting companies, individuals and entities, advising on international and national negotiations; look after the client’s interests in the maintenance and integrity of their assets, facilitating business, preserving individual and collective interests, within ethical principles and in order to strengthen the democratic rule of law. |

| Public prosecutors and lawyers | 2412 | 241205 | Union lawyer | They represent the public administration in the judicial sphere; they provide legal advice and counsel to the public administration; they exercise internal control over the legality of the administration’s acts; they look after public assets and interests, such as the environment, consumers and others; they are part of prosecuting commissions; they manage the human and material resources of the prosecutor’s office. |

| 241210 | Local Prosecutor | |||

| 241215 | National Treasury Prosecutor | |||

| 241220 | State Prosecutor | |||

| 241225 | Municipal Prosecutor | |||

| 241230 | Federal Prosecutor | |||

| 241235 | Foundation Prosecutor | |||

| Members of the PPO | 2422 | 242205 | Public Prosecutor | They act in favor of society and citizenship, defending the legal order, the democratic regime, diffuse and collective interests and individual interests, promoting, privately, public criminal action and public civil actions. They exercise their functions at federal and state level, before the civil, criminal, military, labor and electoral courts. To this end, they suppress crime, bring public civil actions in defense of unavailable individual, diffuse and collective rights; exercise ownership of constitutional and civil actions; monitor compliance with legislation and perform judicial and extrajudicial duties. |

| 242210 | Justice Prosecutor | |||

| 242215 | Military Prosecutor | |||

| 242220 | Labor Prosecutor | |||

| 242225 | Regional Public Prosecutor | |||

| 242230 | Regional Labor Prosecutor | |||

| 242235 | Prosecutor | |||

| 242240 | Deputy Prosecutor for Military Justice | |||

| 242245 | Deputy Prosecutor General of the Republic | |||

| 242250 | Deputy Prosecutor General of Labor | |||

| Police officers | 2423 | 242305 | Police officer | They preside exclusively over judicial police activities; they direct and coordinate activities to repress criminal offenses in order to restore order and individual and collective security. They manage activities in the interest of public security. They issue public documents and manage human and material resources. |

| Court clerks and the like | 3514 | 351405 | Clerk | They carry out the legal and judicial determinations assigned to official and extrajudicial registry offices, police stations and mediation and arbitration chambers, drawing up acts, filing cases, making registrations; they issue warrants, transfers, letters precatory, rogatory and arbitration, as well as certificates; they register documents; they carry out diligence, such as: summonses, subpoenas, arrests and seizures; provide assistance to the public, drafting powers of attorney, authenticating documents and drawing up police reports; assist in hearings; operate out-of-court dispute resolution procedures. |

| 351410 | Court Clerk | |||

| 351415 | Extrajudicial Clerk | |||

| 351420 | Police Clerk | |||

| 351425 | Bailiff | |||

| 351430 | Legal Services Assistant | |||

| 351435 | Conflict Mediator | |||

| 351440 | Out-of-Court Arbitrator |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on RAIS data.

Received: May 03, 2023; Accepted: September 12, 2023

texto en

texto en