Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.53 São Paulo 2023 Epub 07-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980531410076

BASIC EDUCATION, CULTURE, CURRICULUM

CREATIVE PRACTICES AND AFFECTIVE BONDS IN THE CLASSROOM: A NARRATIVE STUDY

IUniversidad de Almería (UAL), Almería, Spain; gabbers1983@hotmail.com

IIUniversidad de Almería (UAL), Almería, Spain; eprados@ual.es

The life stories of two female teachers delve into the type of teaching practices during the democratic transition in Spain. The narrative biographical research, through the use of biographical accounts, investigates the decision-making and practices that made the classroom an emancipatory space. The analysis focuses on the type of creative practices, the basis of educational, collaborative and democratic action. Literary creation and theatrical works, together with the students, fostered autonomy, confidence and a love of learning. These innovative practices, for the time, can be considered today as disruptive practices which, together with the importance of affective relationships and the revaluation of artistic spaces, constitute the basis of pedagogical action.

Key words: TEACHER; LIFE STORIES; BIOGRAPHY; CREATIVITY

Las historias de vida de dos maestras profundizan en el tipo de prácticas docentes durante la transición democrática en España. La investigación biográfica narrativa, a través del uso de relatos biográficos, indaga en la toma de decisiones y prácticas que hicieron del aula un espacio emancipador. El análisis presenta el tipo de prácticas creativas, base de una acción educativa colaborativa y democrática. La creación literaria y de obras teatrales, junto al alumnado, propiciaron autonomía, confianza y amor por el aprendizaje. Estas prácticas innovadoras, para la época, pueden ser consideradas hoy en día prácticas disruptivas que, junto a la importancia de las relaciones afectivas y la revalorización de espacios artísticos, se constituyen como base de la acción pedagógica.

Palabras-clave: MAESTRA; HISTORIAS DE VIDA; BIOGRAFÍA; CREATIVIDAD

As histórias de vida de duas professoras permitem estudar o tipo de práticas de ensino desenvolvidas durante a transição democrática na Espanha. A pesquisa narrativa biográfica, através da utilização de relatos biográficos, investiga a tomada de decisões e as práticas educativas que fizeram da sala de aula um espaço emancipatório. A análise apresenta o tipo de práticas criativas, base da ação educativa colaborativa e democrática. A criação de obras literárias e teatrais, juntamente com os estudantes, fomentou a autonomia, a confiança e o amor pela aprendizagem. Essas práticas inovadoras, para a época, podem ser consideradas hoje práticas disruptivas, que, aliadas à importância das relações afetivas e à revalorização dos espaços artísticos, constituem a base da ação pedagógica.

Palavras-Chave: PROFESSOR; HISTÓRIAS DE VIDA; BIOGRAFIA; CRIATIVIDADE

Les récits de vie de deux enseignantes permettent de s’interroger sur le type de pratiques pédago- giques pendant la transition démocratique en Espagne. La recherche biographique narrative, par le biais de récits biographiques, étudie les prises de décision et les pratiques qui ont fait de la salle de classe un espace émancipateur. L’analyse présente le type de pratiques créatives, base de l’action éducative collaborative et démocratique. La création d’œuvres littéraires et théâtrales, avec les élèves, a favorisé l’autonomie, la confiance et le goût de l’apprentissage. Ces pratiques innovantes, pour l’époque, peuvent être considérées aujourd’hui comme des pratiques perturbatrices qui, ensemble avec l’importance des relations affectives et la revalorisation des espaces artistiques, constituent la base de l’action pédagogique.

Key words: ENSEIGNANT; HISTOIRES DE VIE; BIOGRAPHIE; CRÉATIVITÉ

Situating the educational experience: Creative practices and affective relationships

The period of democratic transition in Spain brought with it a political and social movement driven by women who laid the foundations of an education based on counter-hegemonic models of teaching-learning (Robles et al., 2018). To deepen the practices that took place during that time and understand the ways of doing an “other” school (Carrasco-Segovia & Hernández-Hernández, 2020; Torrego-Treviño et al., 2013), it is important to access the experience, the memories, and the meaning that people give to it (Delgado-Gómez et al., 2019; Leite-Méndez et al., 2019). Rescuing memory implies recounting the lived experience and that is why biographical stories contain the feelings of people and the ways in which relationships and bonds are woven in the classroom (Rivera-Garretas, 2012). At the same time, the stories express those difficulties, obstacles and resistances with which people face the educational task in complex socio-political contexts, such as the democratic transition in Spain. Research with life stories in education makes evident the importance of retrieving experiences through a critical-reflective process (Hernández-Hernández & Sancho-Gil, 2020; Rivas-Flores et al., 2014) to give the classroom a new meaning as a transformative space.

The franco era left an inheritance towards the figure of the woman overdetermined by the vocation of being a mother and attributes such as religiosity, protection, and proficiency in domestic functions, characteristics that were transferred to the role that as teachers they had to maintain in the profession (Noblet, 2022). Uprooting these roles in the profession meant, at the time of the Spanish democratic transition, an opening towards innovative or transgressive practices that would lead some educational sectors to incorporate or recover ideas from the pedagogical renewal movement of the second republic period, strongly censored by the Francoist regime, and that at the beginning of democracy in the 1980s began to recover with certain resistances (Feu & Torrent, 2021). At present, we call disruptive pedagogies those that combine a series of principles and strategies that favor transformation processes in the classroom, based on democratization, flexibility and creativity in the learning processes, providing more autonomy and critical thinking to students (Christensen et al., 2008; Giroux, 2015; Montes-Rodríguez et al., 2021).

On the other hand, the narrative values the gaze and voice of the subjects by recognizing the educational experience from subjectivity, that is, the changing dimension of experiences, of people’s lives and their narratives (Contreras & Manrique, 2021). From this perspective, the understanding of the narrated experience becomes knowledge, as it helps to understand the context where educational practice takes place and the ways of acting and exercising in teaching (Leite-Méndez & Rivas-Flores, 2021).

Considering the value of the experience of female teachers implies signifying the school from feminist positions (Braidotti, 2004), in the sense of questioning the hegemonic patriarchal dynamics, practices and policies (Rivas, 2022) and delving into the knowledge, practices and sensitivities of another way of doing school. This feminine knowledge, Arnaus (2013) relates it to the creative processes undertaken by women in their educational professional development and links it to the personal and pedagogical commitment that brings into play ways of thinking and communicating with the body in its multiple expressive and artistic manifestations, despite being conditioned by the socio-political situation of the moment. Addressing everyday teaching practice in the classroom starting from the creation of own languages at the time of the democratic transition in Spain implied questioning the traditional, repetitive, learnt by rote, and banking mode inherited and installed in the teaching of the time. Addressing everyday teaching practice in the classroom from the creation of own languages at the time of the democratic transition in Spain implied questioning the traditional, repetitive, learnt by rote, and banking mode inherited and installed in the teaching of the time.

This study is based on the different body languages involved in teaching practices or on an education based on the knowledge and taste of the body (Planella-Ribera, 2017). The body of education considering as a sociocultural construct (Carrasco-Segovia & Hernández-Hernández, 2020; Prados-Megías, 2020b), will be key to understand the meanings that women teachers give to their expressive, creative, and communicative experience inside and outside the classroom.

The relationship between body, action, and representation in the classroom acquires important ethical considerations. We speak of the ethics of care as a form of universal relationship in the classroom, redefining relationships with oneself, with others, and with the world-planet (Correa-Gorospe et al., 2021). Hence, affection and care in pedagogical relationships extend to everything involved in educational practice as an “experiential force that always circulates through human and non-human bodies” (De Riba Mayoral, 2020, p. 327, own translation).

The ethics of care is distinguished by the fact that it breaks with the traditional logic of hierarchical relationships in the classroom and in school (Quiles-Fernández & Forés, 2013), stimulating horizontal pedagogical relationships that give rise to disruptive, participatory, and collaborative practices (Giroux, 2015). Affection and care in the classroom are related to the ability to “listen to the voices, silences, gestures, and discomforts that the educational encounter generates” (Orozco et al., 2021, p. 739, own translation), thereby favouring dynamics that involve the body in the educational space or, in other words, a poetic education of the body of aesthetic pedagogical languages (Gómez et al., 2017).

In this sense, the disruptive, the participatory, and the collaborative are imbricated with the human, with the body-to-body relationship, breaking the verticality and hierarchy of the educational system (Paredes-Labra, 2013). These two teachers began a path of search for other new forms of learning by placing the focus on practices that involved a bodily and creative commitment (Galak & Almeida, 2020), to themselves and to the students, inspired by practices of the so-called pedagogical renewal (Torrego-Egidio & Martínez-Scott, 2018).

From this perspective, the creative conception of relational practices involves understanding this research as an investigative process that analyzes and interprets the elements that are participating in the construction of the teaching practices of two teachers. The positioning and concerns of both teachers invites us to understand them as transgressive, and therefore, disruptive teachers at a time in history when the General Education Law enacted more democratic and participatory changes in which a strong tradition of hierarchical relationships and practices persisted in the educational institution (Parra-Ortiz, 2009). Therefore, the fact of investigating the way in which these teachers understood and brought to action participatory educational processes based on expressive and creative dynamics acquires relevance, with theater, reading, and writing as central axes. These processes, today, could resemble what is commonly called educational innovation (Montes-Rodríguez et al., 2020; Prendes-Espinoza & Cerdán, 2021). These authors understand educational innovation as those transformative and disruptive actions that occur in the classroom, beyond mere methodological or instrumental strategies, which allow reflection on onto-epistemological issues (Rivas-Flores, 2022), as well as ethical issues (Cortés-González et al., 2020).

Methodological contextualization of the research

This research has been approached from the narrative biographical method. By using narrative in the research, we are prioritizing the story told and contextualized in a specific time and place (Prados-Megías & Rivas-Flores, 2017). Narratives also offer spaces for dialogue that help to make visible difficulties, concerns, and emotions, ignored issues in strongly hierarchical spaces and from other research perspectives (Rivas-Flores, 2021).

The people participating in this research are two teachers - who, by their express desire, want to be called by their proper names -, Concha and Paqui. Much of their teaching activity took place during the last period of the Franco dictatorship in Spain, the transition to democracy and its consolidation (period between 1965 and 2011).

Their teaching practices, based on participatory action and assembly proposals, are based on real situations experienced by the students. Their pedagogical and didactic approaches question the traditional way of doing school and, in this sense, it can be said that they were a transgressive revulsive for the time, in the schools and classrooms where they practiced their teaching.

Narrative biographical studies have the singularity of being narrated in the participants’ own voice (Clandinin, 2018) which allows to deepen the emotions, thoughts, conceptions, and socio-political contexts in which the participants are inserted and, in this way, to understand the complexity and construction of identities (Tadeu & Lopes, 2021).

Concha is a teacher and writer, with numerous publications and literary awards. Her story of 40 years of teaching profession as a Language and Literature teacher questions the immobility present in the school she has experienced and the importance of creative thinking in the classroom.

Paqui is a teacher with a long activist career in movements of pedagogical renewal and she is linked to the world of theater. As a teacher, she participated in research on the role of female teachers in the democratic transition (Robles-Sanjuán et al., 2018). The theater, together with the principles of Freinet pedagogy, in which she is trained, are the instrument that since the early 1970s allowed her to understand and transmit the school as a space for collective, democratic, supportive, and creative learning.

The collection of information was carried out through in-depth interviews (Fontana & Frey, 2015), however, for this study we must refer to these as narrative encounters (Leite-Méndez et al., 2019), defined as spaces in which an egalitarian and horizontal relationship between researcher and participants stands out. The meetings took place between 2015 and 2018. 14 interviews (8 with Concha and 6 with Paqui) were carried out. Each interview lasted approximately two hours. The interviews addressed issues related to the socio-political, family, and educational context they lived, decision-making regarding their academic training, educational conceptions and practices, knowledge of legislation and educational institution, professional teacher development and their role as female teachers.

During 2018, four individual in-depth interviews were also conducted with three female and one male of Concha’s students and a group interview with five female of Paqui’s students (Table 1).

Table 1 Instruments for information collection

| In-depth interviews: Narrative encounters (Leite-Méndez et al., 2019) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Age | Profession | Interview | |

| Concha | 76 | Retired teacher | 8e/2h | |

| Paqui | 62 | Early retired teacher | 6e/2h | |

| Concha’s students | Helena (H) | 40 | Elementary school teacher | 1e/1h |

| Alicia (A) | 41 | Employee | 1e/1h | |

| Marco (M) | 42 | Employee | 1e/1h | |

| Monica (Mo) | 42 | University professor | 1e/1h | |

| In-depth interviews: Narrative encounters (Leite-Méndez et al., 2019) | ||||

| Participants | Age | Profession | Interview | |

| Paqui’s students | Olga (O) | 46 | Employees | 1 group interview (2 hours) |

| Yolanda (Y) | 45 | |||

| Herminia (He) | 45 | |||

| Sonia (S) | 46 | |||

| Lali (L) | 46 | |||

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Various materials that were shared during the meetings have been analyzed, such as: memories of the students, letters, drawings, photos, books, and texts. This fact allows us to evoke memories of the past in present time, to look at details and other interpretations giving depth to the experience and the emotional imprint (Sancho-Gil & Correa-Gorospe, 2016).

The process of returning the information collected took place once the different transcripts were made. The continuous exchange of information between researcher and participants has led to a process of co-construction with two voices (Cortés-González, 2012), generating two biographical stories in which the life trajectories of each teacher can be read, interwoven with the educational experience.

The stories are analyzed from sense cores that facilitate the process of categorization in an emergent way. These sense cores have been categorized with the help of the Nvivo11 program, based on the information collected. The categories constitute the basis for the re-construction, re-meaning and interpretation of their experiences and life stories (Suárez & Dávila, 2018). Based on the proposal of Rivas-Flores and Prados-Megías (2014), Table 2 shows the distinct phases conducted in the analysis procedure of this research.

Table 2 Phases of the analysis

| Phases | Process |

|---|---|

| Transcripts | The information gathered in the meetings is literally written down in a document. It is given to participants for review, modification, and discussion |

| Sense cores | Through careful and slow reading, the set of topics that appear in the narratives of each of the participants is extracted, organizing them into a single list |

| Categories of analysis | Topics are grouped by analytical categories |

| Categories of interpretation | The categories of analysis are explored in order to establish what they tell us and to investigate the contexts and experiences of the participants who construct their trajectories |

| Construction of the interpretative story | The construction of the story is shared between the participants and the researcher |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Rivas-Flores and Prados-Megías (2014).

The categorization process starts from the experiences of each subject. This allows these two women to bring different meanings to the events they experience, thus creating unique worlds. Their voices refer to the uniqueness of social, cultural, historical, political, and educational contexts of the times they have lived through. For this reason, the use of grounded theory allows us to study these unique worlds in depth, as it considers the interpretation that subjects have of their contexts. We refer to the meaning that Charmaz (2012) raises on grounded theory, offering a model that allows categorizing and systematizing information by undertaking a process of construction and deconstruction of this information based on emerging themes and in close relation to processes of reflexivity, a substantial element in the process of analysis. This process assumes, according to García-Huidobro (2016), that the “data are co-constructed between the researcher and the participants, since the researcher’s gaze and interest are never left out” (p. 110, own translation). This implies an open coding process in the treatment of information, which means that both thematization and categorization of data do not start from previous theoretical frameworks but are generated in the research process itself and in close relation to the constant dialogue and questions that the researcher asks to the research (Miranda & Silva, 2022).

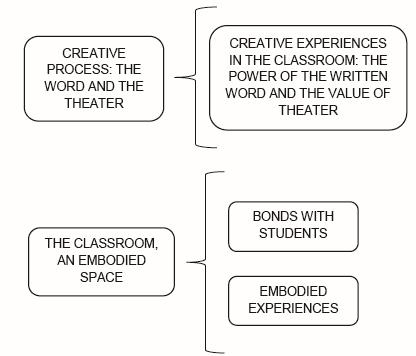

Following the model of Leite-Méndez (2011) on the categorization of teachers’ professional trajectories, this analysis is based on three categories: personal identities, social identities, and professional identities and which, in turn, are explained based on different themes. These thematic axes help to give solidity to the interpretation of the stories as they explain the way in which each participant understands and contributes meanings to aspects related to the socio-political context, to family relationships and ties, to creative experiences in the classroom, to the type of relationships with teachers in the different educational scenarios, to institutional power relations, to bonds with students, to those memories in the form of resilient educational traces, and to experiences that have been engraved in the bodies and that somehow constitute embodied experiences. These aspects constitute the themes around which categorical families or interpretative categories have been constituted. The categorization process is understood as a rhizomatic process (Leite-Méndez & Rivas-Flores, 2021), in which some categories intertwine and relate to others, providing correlational senses and meanings to the educational experience. The analysis process has resulted in the following categories: the creative process: the value of the word and the value of theater; and the classroom, an embodied space.

Each of these interpretative categories is nurtured by themes emerging from the readings and analysis of the stories of the teachers:

In the category “creative process: the word and the theater” innovative and creative experiences that are part of pedagogical knowledge are analyzed. These experiences depict a classroom in which the daily reality that students experience acquires a creative dimension, the result of improvisation processes, based on two elements: writing and dramatized movement. In the category “the classroom, an embodied space” the classroom is re-identified as a space in which educational relations - the relations between the group, the teacher, and each subject - allow themselves to be “touched-affected” by what happens in the classroom. Both dimensions provide elements to reflect on how teachers build and give sense to their professional practice, in an era of political and educational changes in which innovation was still incipient and in which opting for such approaches meant assuming certain pedagogical, methodological, organizational, and institutional resistances.

These practices challenge the “normality” of the educational processes of the time by transforming the typically feminine stereotypes (care, sensitivity, protection, among others) into tools to educate in values such as critical thinking, respect, and empathy (Serra, 2018). Their practices move away from the classic traditional role of the teacher who designs and to grade content, having the textbook as a reference. These female teachers generate living knowledge that moves away from encyclopedic knowledge (Veltri, 2017).

The creative process

In the narrative that both teachers make about educational practice the dynamic conception of the classroom as a reality connected to what the students live and bring with them stands out. The classroom is conceived as a “text”, as a stage, where each movement invites to explore, to create, to improvise, to participate, and to transform (Díez-Palomar & Flecha-García, 2010). A continuous dialogue between what they experience outside and inside the classroom. The pedagogy of the situation of Barret (1991), explains how knowledge and daily life are interrelated and nurtured to develop creative situational dynamics. In Concha’s case, this pedagogy of the situation can be understood through literature and creation of stories that narrate anecdotes, concerns, or themes of the daily life of the students. In Paqui’s case, theater and body expression are used as situational elements that serve to establish the bases from which she develops her teaching, “making a theater like the one we did in which we talk about the body and we comment on what is lived, what is felt and thought, makes critical and knowledgeable people, the basis of what it is to educate” (Paqui’s story, 2017).

In both didactic dynamics or strategies, the focus of action pivots on three fundamental issues: respecting the students’ learning processes, promoting each subject’s own qualities, and seeking critical thinking towards learning. The type of practices and affective relationships generated by the teaching action of both teachers questions the strong roots of a basic banking education of the time (Freire, 1993), in which students were conceived as recipients of repetitive learnt by rote concepts (Crespo-Cordovez, 2021).

However, this type of daily practices for the two teachers generated tensions and difficulties among their educational community, “sometimes I played with the children at recess to get closer to them and I remember how some teachers reproached me, they told me that my way of acting was not appropriate” (Concha’s story, 2015). As Estalayo-Biesa et al. (2022) point out, generating affective bonds with students reinforces the possibility of alleviating the tensions that persist due to structural inequalities and that are reproduced in the educational institution. On the other hand, in this creative process affective relationships are especially linked to the spaces that are inhabited. Breaking with the organizational institutionality of the classroom means tensing and questioning traditional places of learning in order to transform them into creatively embodied spaces; today we could call them learning ecologies and multisensory participation (Villena-Higueras et al., 2018),

. . . I asked for a space in the gym, it was wonderful to link classes and theater. We were all delighted. But soon this generated envy in the faculty and they began to reduce my schedule and to bring in more groups while I was teaching my classes. I had to go back to the classroom because that generated a lot of tension. They did not understand what I was doing. (Paqui’s story, 2017).

The power of the written word

The word is the center of learning and educational work in the classroom. Each child brings uniqueness to the process to the extent that he or she expresses his or her way of knowing, feeling, and living the world through the written or theatrical word. The word as an action to “seek ideals through the value, beauty, and importance of dialogue” (Concha’s story, 2016), through the power granted by free writing. In this way, Concha turned classrooms into hotbeds of ideas and reflections on controversial matters such as

. . . the Civil War, such a taboo subject at the time. A classmate and I each played a role. We debated with our little awareness because what we knew was scarce. She, Concha, was dedicated to arbitrating. She used to bring two extreme confrontations together through dialogue and arguments. (Student M.’s story, 2017).

The symbolic value of the word has defined the teacher-student relationship as a meeting place between learning and dialogue (Freire, 2002). The classroom becomes a space that invites to feel, more than to memorize,

Paqui reasoned things out and made us talk and value our environment. Everything was consensual in order to solve problems among the classmates. She was a moderator and the conflict had to be resolved between the two people by talking. This encouraged us to help each other in class and that was our main task, to help those behind. (Group’s story Y, He, 2018).

In the classrooms of these two teachers, the word is conceived not as an academic task (Santaella-Rodríguez & Martínez-Heredia, 2018), but as a motor and reason for creation and dialogical development in the classroom. Elaborating a free text, dramatizing or staging a text, creating drawings or murals, inventing stories, and looking for performances broke with the typical and traditional school tasks,

She encouraged the children to write about whatever they wanted. Those free texts changed the class. The best text, which was chosen by democratic procedure, was worked on and from there the classroom was transformed into a theatrical space. (Paqui’s story, 2017).

The creation of stories, poems, or books that Concha wrote under pseudonyms helped to create participatory learning spaces in the classroom, in which the protagonists of her stories were the students themselves. The dialogues held with girls and boys in the classroom become the inspiration for the works that Concha wrote and that she later used as basic tools in the classroom as the way textbooks are used: “as I was writing a chapter, I read it to the children in class and they told me whether they liked it or not” (Concha’s story, 2015). In her works, she recreated a universe of real experiences, through which the bond that these stories had with the students’ lives was revealed or even how the reality they lived was represented by stories that were real or relatable to them (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2018). In this sense it is worth highlighting, for example, the experience about death that a child tells one day in class. Concha approaches it with the creation and publication of a short humorous story that she called Adventurous Skeleton, “I didn’t want to talk to them about death from the traditional point of view of blackness, but from a fact that is going to happen, that hurts us, that is painful, but that is something natural” (Concha’s story, 2015). The teacher narrates that this story gave the opportunity to listen to other experiences of death that the students lived, to share them and to be able to talk about death as a substantial and natural issue during life: “we could talk about pain, emotions, questions, and adversities that death causes in children and their environment” (Concha’s story, 2015).

On other occasions, events surrounding the course of each day became an opportunity to learn to write from the emotion. It was common for a day in class to start by writing about a current topic or an event of interest that they brought in “their backpacks”. The writing was free, and the written texts were used to establish a relationship between current affairs, the narration, and the contents of the subject,

The Gulf War had begun, and we wrote to Interviú magazine a letter addressed to the soldiers, giving them our support, and asking for peace in the world. We believed that we could really change the world. We thought that it could reach many people and so the world could see that children didn’t like wars. (Student H.’s story, 2017).

The value of theater

Although theater has always been an educational resource, using it as a creative resource in the classroom implies not only a process of elaboration, collaboration, and participation, but also a space to generate relational bonds so that learning is meaningful and transformative (Poveda, 2018). Paqui wanted the techniques used in theater, such as body expression, psychomotor skills, mime, etc. to be not only theatrical techniques to be used in an isolated moment in the classroom, but to be the methodology that structured learning, as a means for “interpellation, assault on the sleeping soul and, above all, dialogue. A dialogue from person to person . . . from look to look, from vibration to vibration” (Poveda, 2018, p. 100, own translation).

The theater was a place of relationship between boys and girls, it created a lot of companionship. It is well known that theater brings people together! Doing things in a group unites and fosters trust and breaks individualism or who was first. (Group’s story O, S, 2018).

The theater has been the way of teaching, a place of living presence of the body in the classroom, even though, both in the 1970s and today, the body remains being pulled apart from the various academic spaces (Penac, 2017). Freinet pedagogy, rooted in the training of this teacher, gives meaning to her daily theatrical practice, and opens paths of resilience and transformation to students (Cortés-González & Jiménez, 2016),

. . . it is not only about techniques, but about an attitude towards life . . . I firmly believed that I could transform reality, because doing theater like the one we did in which we talked about the body, commented on what is lived, what is felt and thought, makes critical and creative people. (Paqui’s story, 2017).

“Encounters with art have a unique power to free the imagination” (Greene, 2005, p. 50, own translation), while art also goes beyond the walls of the classroom to project itself outside it (Cortés et al., 2018),

We went out onto the streets during Cultural Week, and we felt super important dancing, with our body expression and theater . . . . We created a story, presented it to Coca-Cola and won. She would encourage you to let your imagination fly and to write, so that your ideas flow and so that you know how to express yourself. (Group’s story L, He, 2018).

Theater, as a daily educational resource in the classroom, is a source of expression of emotions, feelings, conflicts, tensions (Fernández & Montero, 2012), while it is an integrating space of differences and peculiarities (Recasen-Belenguer et al., 2022). These experiences leave its mark on learning for life,

. . . I was super shy, got tongue-tied a lot and had a horrible fear of reading. She made me do a monologue at an end-of-term party. She was with me the whole time; I’ll never forget that. After that, my fear went away a bit and that’s when I started to read books. Today, as a mother, I participate in the school’s Reading Club and every week I bring books for the children and read to them. (Student A.’s story, 2017).

Rescuing activities such as theater or creative writing in educational classrooms today would not have to be revulsive or synonymous with innovation or transformation, even more so knowing that both have always been, to a large extent, examples, and countercultural expressions. Despite this, in the educational field these practices have been confined to occasional or exceptional moments, since, as Rivera-Vargas et al. (2022) point out, cultural domination in this neoliberal society,

. . . could not have been possible without educational institutions becoming one of the main places of discursive and material dispute. This fact has conditioned the existence of a school model that educates “from fear” and that, based on this, has ensured the non-expansion of emancipatory and solidary subjectivities. (p. 119, own translation).

The emancipatory positioning that the use of creative writing and theatrical dynamics implied for these teachers - in the historical time they lived in - brought with it questioning the punitive educational culture of fear, as well as certain academic and institutional disputes to the extent that their practices involved shared time, reorganization and conceptualization of more flexible spaces and contents, debates with colleagues and families, conflict knowledge and predetermined ways of doing things and building relationships and ties that transcend the walls of the classroom and the very act of educating. These tensions make us think of pedagogical plots that are sustained between fear and hope (Santos, 2019).

The classroom, an embodied space

The two teachers of this study have made their profession a creative experience in which they consciously and reflexively incorporate the corporal and affective dimensions into the learning process. These are embodied learnings (Rogowska-Stangret, 2017), because what happens in the classroom is corporeal and provides a new sense of emotional education. The creative process developed in the classroom, both through writing and theater, involves two principal issues in the teachers’ pedagogical relationship with the students: personal relationships based on the creation of affective bonds and the sense of authority.

Speaking about affective bonds, Bisquerra and López (2021) argue that they improve the attitude towards oneself and others, generate a classroom climate that encourages care, assertiveness, resilience, and desire to learn. Ruiz and Pisano-Casala (2020), propose that knowledge is an act of relationship, as far as it materializes a body-to-body encounter between teacher and students, since all learning implies a personal relationship and, therefore, an embodied pedagogical process. The teacher-student affective bond is not only a relational act - which implies a way of adopting an ethical attitude in front of the students - but is also closely related to the way of listening and, therefore, to the bodily meaning that listening implies, that is, how, for what, and from which position do we listen to children and in what way children listen.

I understand that it is a relationship between people, people who each have their task, their work. We have to speak, we have to understand each other in all situations of life. (Concha’s story, 2015).

Paqui treated us as if we were adults. She reasoned things to us and made us appreciate our environment, made us realize things that went unnoticed. (Group’s story Y, S, 2018).

Embodied learning in the classroom implies a recognition of one’s own experiences in order to offer an “other” view (Carrasco-Segovia & Hernández-Hernández, 2020), that is, it is not about other views, but about questioning some of the hegemonic and unquestionable approaches about teaching work. In this sense, the “other” view maintains a constant concern about how to direct attention to the uniqueness of the students including the embodied experience in their bodies. This is, as Freire (2002) would say, to read the classroom-body as a “text” (as context and pretext) to understand the world, like an epistemological curiosity. When we consider the body-experience-singularity relationship, a space of mutual understanding and relationship is opened, that is, “affection as an invisible force that changes bodies in their relationship and changes the ability to act” (De Riba Mayoral, 2020, pp. 323-324, own translation).

The body as a construct that becomes embodiment - cultural, historical, and pedagogical space - (Planella-Ribera, 2017), gives meaning to the multiplicity of relational languages in the classroom. Rescuing the body as experience is the only possible way to demand the classroom as a relational space. Bodies in the classroom are also the “instruments with which we touch life” (Pisano, 2010, p. 70, own translation), “children suffer a lot when they feel unfairly treated, I have had to console many children completely helpless, sad and overwhelmed. Childhood is not so easy” (Paqui’s story, 2017).

I have the best possible concept of childhood. For me, they are the most endearing thing in the world, at any age, but I also feel a bit sad because I think that childhood is very undervalued by parents and teachers. Children should be counted on for everything too. They have so many capabilities! And they grow up so fast that sometimes we miss very important things (Concha’s story, 2015).

On the other hand, the affective relationship in the classroom implies authority, understood in terms of “recognition as a freely accepted referent” (López, 2013, p. 214, own translation), a necessary condition to generate lasting and responsible bonds (Arendt, 1996). In the classrooms of these two teachers, authority is expressed as mediation, as an encounter, rather than as a hierarchical relationship of who has knowledge, wisdom, and control. Authority in this sense is adopted as “a position of openness, of letting things flow, of thinking about how relationships within the classroom can be transformed” (López, 2002, p. 159, own translation). In her early days as a teacher, Paqui narrates that,

. . . she was concerned about how she could exercise control in the classroom and how students could respect her. I learned and reflected that the principles of Freinet pedagogy invited me to see that authority emanates from the person, from the example you set. (Paqui’s story, 2017).

The lasting and responsible bonds that Hannah Arendt talks about will be the driving force to understand that authority is synonymous with recognition of the work of the teachers and the example they show, “I was not more important, I was just one more, they had a job, and I had a different one. The technique I have always followed has been based on collaboration, help and tolerance” (Concha’s story, 2015). In this sense, authority is also expressed through their bodies, to the extent that they are concerned that their teaching relationship is a loving relationship (Mañeru-Méndez, 2006), close to and respectful with bodies. This also implies understanding the body in movement - in its ontological sense -, that is, a body that moves in the classroom not to do things with it but to become a humanized body that questions itself and that is sensitized by the events of the educational experience (Contreras, 2021) in which emotionality and feelings emerge, that are so hidden in the classroom or so expressed in the bodies as failures, shame, shyness, sense of ridicule, devaluation, or low self-esteem (Prados-Megías, 2020a). An embodied body is to attend not to what we do with the body, but to who we are and who we are being as we do with the body (Prados-Megías, 2020b). Dramatizing, theatricalizing, or writing freely refers to the body-experience as an expression of the multiplicity of subjectivities of the reality in any classroom and of a type of relationships that promote authority. An authority that, etymologically, refers to arousing, increasing, promoting, advancing, and fostering creative qualities, both in the daily doing of any classroom and in the relationships and educational bonds that this entails.

In conclusion

Narrative research, through biographical stories of teachers, configures a network of experiences that help to reconstruct the knowledge about experience and, with it, to (re)identify the constant construction and becoming of the teaching profession. The stories offer a kaleidoscopic view, in continuous itinerancy in the ways of exercising a teaching marked by a socio-political context adverse to any type of transformative, creative, and horizontal educational practices. These questions help us to think that pedagogically, classroom practice becomes an act of resilient militancy (Cortés-Gonzáles & Jiménez, 2016). These teachers challenge the traditional teaching models of the time, one with creative and free writing, and the other with the principles of Freinetian pedagogy applied to theater. They create other ways of educating in which students are active co-participants in their own learning. The research highlights the dialogical interaction between teachers, students, and the context in which they relate, on a cognitive, emotional, social, and moral level, as an emancipatory act, as well as constituting a real expression of how to generate in the educational institution the importance of the strength of the collective, of creative-participatory action and of solidarity between equals, in the face of the demolishing principles of neoliberalism. These creative practices are constituted as educational cultural expressions that transform the body-school-society relationship (Galak & Almeida, 2020). As Rivas-Flores (2022) proposes, this way of being a teacher implies a paradigm shift by breaking the inertia in understanding the professional trajectories of future teachers that originate in school, then in practices in initial training and finally the return to the school institution. All these trajectories occurring under the umbrella of a prevailing neoliberal morality without the teacher in training having had transformative experiences and alternative practices. Hence the importance of knowledge situated in accordance with practices that bring into play the social, cultural, and political needs and tensions that characterize the school institution. In this sense, both theater and creative writing, used as transformative practices by these two teachers, have been and continue to be ways to continually rethink and question throughout their profession what kind of teachers they wanted to be, how to face difficulties in the school institution and the critical sense they wanted to awaken in the students.

The forms of pedagogical knowledge narrated by Paqui and Concha reveal that the way of understanding school is linked to processes of creativity, especially connected to the way of generating affective bonds with students, based on respect and recognition of authority as a form of educational relationship. These processes of relational creativity are associated with the experience of embodied bodies (Planella-Ribera & Jiménez, 2019), as teachers and students feel challenged by what they do and how they do it. The living traces in the teaching work, as reflected in the testimonies, offer an “other” story of school (Hernández-Hernández & Sancho-Gil, 2019), a story that draws the senses and learning in the lives of teachers and the consequences that this may have to transform teacher training today.

The creative processes are constituted as a personal and pedagogical commitment to rethink the educational institution. The narratives of these two teachers show that a democratic and emancipatory school (Freire, 2002) needs instruments of culture and art, such as writing and theater, to generate knowledge that embodies the subjectivities present in a collaborative and diverse knowledge (Pallarès-Piquer & Planella-Ribera, 2019). In this sense, their professional trajectories point to the use of disruptive and transformative practices both space and times that make up today’s school classrooms. Hence the importance of incorporating into the school elements to reflect on the meaning of collaborative, horizontal, creative, and emancipatory work with students and the educational community.

Finally, narrating (oneself) is part of the own learning that they have lived as teachers and gives meaning to the affections that have been put into play in the exercise of teaching. Affections that bring understanding, not only to feelings, but to the great questions that link the practical work, the educational experience, and the political commitment that school must promote. Hence, the exercise of the teaching profession must be a continuous process of reflection on one’s own practice (Giddens, 1995), on the construction of knowledge in the classroom and in the institution, and on the various ways of promoting commitment to social transformation (Santos, 2018). The stories of these two teachers can be a legacy to rethink today’s school.

Given the narrative nature of the research, it would be interesting in the following approaches to develop studies in the current sociocultural context that consider, through narratives, the consequences of the use of technologies and the virtual on the affective relationships in the classroom and the type of practices that are carried out, paying attention to the sense of embodiment versus the predominance of information. As Byung-Chul (2021, pp. 17-18, own translation) states “the world becomes emptied of things and filled with disturbing information like disembodied voices. Digitalization dematerializes and disembodies the world, the digital, i.e., numerical order lacks history, and consequently fragments life”. The classroom, lived and constructed from the reality of each student, becomes through the artistic and expressive a multiplicity of stories, of voices with bodies, which deserve to be told and listened to as a form of living knowledge, that is, small narratives will act as challenges to large narratives (Berry, 2008) and as key elements that allow us to reconsider the multiplicity of subjectivities.

REFERENCES

Arendt, H. (1996). Entre el pasado y el futuro: Ocho ejercicios sobre la reflexión política. Ediciones Península. [ Links ]

Arnaus, R. (2013). El sentido libre de la diferencia sexual en la investigación educativa. In J. Contreras, & N. Pérez (Comps.), Investigar la experiencia educativa (pp. 153-174). Ediciones Morata. [ Links ]

Barret, G. (1991). Pedagogía de la situación en la expresión dramática y en educación. Recherche en Expression. [ Links ]

Berry, K. (2008). Lugares (o no) de la pedagogía crítica en les petites et les grandes histories. In P. McLaren, & J. Kincheloe (Eds.), Pedagogía crítica: De qué hablamos, dónde estamos. Grao. [ Links ]

Bisquerra, R., & López, E. (2021). La evaluación en la educación emocional: Instrumentos y recursos. Aula Abierta, 50(4), 757-766. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.50.4.2021.757-766 [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. (2004). Feminismo, diferencia sexual y subjetividad nómade. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Byung Chul, H. (2021). No-cosas. Quiebras del mundo de hoy. Taurus. [ Links ]

Carrasco-Segovia, S., & Hernández-Hernández, F. (2020). Cartografiar los afectos y los movimientos en el aprender corporeizado de los docentes. Movimento: Revista de Educaçao Física da UFRGS, 26, Artigo e26012. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.94792 [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. (2012). The power and potential of grounded. Medical Sociology Online, 6(3), 1-15. https://www.britsoc.co.uk/files/MSo-Volume-6-Issue-3.pdf [ Links ]

Christensen, C. M., Johnson, C. W., & Horn, M. B. (2008). Disrupting class: How disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns. McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Clandinin, D. J. (2018). Reflections from a narrative inquiry researcher. Learning Landscapes, 11(2), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v11i2.941 [ Links ]

Contreras, J. (2021). Presentación del Monográfico: El currículum como un proceso de creación: Indagaciones narrativas. Aula Abierta, 50(3), 663-664. https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/AA/article/view/16720 [ Links ]

Contreras, J., & Manrique, G. (2021). Abrir caminos, emprender viajes: El currículum como experiencia de apertura. Aula Abierta, 50(3), 665-672. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.50.3.2021.665-672 [ Links ]

Correa-Gorospe, J. M., Aberastury-Apraiz, E., & Gutiérrez-Cabello, A. (2021, diciembre 1-3). El cuidado y la relación pedagógica en una investigación sobre cómo aprenden los jóvenes estudiantes universitarios. Cuarta rueda de conversación en torno a las comunicaciones: Ámbito 2. Estrategias ante la falta de cuidados en la Universidad de la VII Jornadas sobre la Relación Pedagógica en la Universidad. El lugar de los cuidados en las relaciones pedagógicas en la Universidad. Centre de Recursos Específics de Suport a la Innovació i a la Recerca Educativa, Barcelo, Spaña, 7. https://www.dropbox.com/s/ca10vbfuslcghkm/Correa-Aberasturi-Gutierrez.doc?dl=0 [ Links ]

Cortés-González, P. (2012). El proceso de devolución, discusión e interpretación en la investigación socio educativa con Historias de Vida. In J. L. Rivas, F. Hernández, J. M. Sancho, & C. Núñez, Historias de vida en educación: Sujeto, diálogo, experiencia (pp. 67-72). Dipòsit Digital UB. https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/32345/7/reunid_rivas%20et%20al%202012.pdf [ Links ]

Cortés-González, P., & Jiménez, A. (2016). Identidades resilientes. Identidades creativas. ¿Acaso la botella es siempre verde? In P. Cortés-Gonzáles, & M. J. Márquez-García, Creatividad, Comunicación y Educación: Más allá de las fronteras del saber establecido (pp. 35-49). UMA Editorial. [ Links ]

Cortés-González, P., Leite-Méndez, A. E., & Rivas-Flores, J. I. (2018). Relatos con corazón. Aprendizaje con estudiantes universitarios a través de sus autobiografías. In M. E. Prados-Megías, M. J. Márquez-García & D. Padua-Arcos (Coords.), Otra pedagogía en movimiento. Dialogando con la experiencia en la formación inicial (pp. 33-61). Edual. [ Links ]

Cortés-González, P., Leite-Méndez, A. E., Prados-Megías, M. E., & González-Alba, B. (2020). Trayectorias y prospectivas metodológicas para la investigación narrativa y biográfica en el ámbito social y educativo. In J. M. Sancho-Gil, F. Hernández, L. Montero-Mesa, J. P. Pons, I. J. Rivas-Flores, & A. Ocaña-Fernández (Coords.), Caminos y derivas para otra investigación educativa y social (pp. 209-222). Octaedro. [ Links ]

Crespo-Cordovez, A. L. (2021). Nuevos desafíos en la enseñanza y la pedagogía. Revista Scientific, 6(22), 346-358. https://doi.org/10.29394/Scientific.issn.2542-2987.2021.6.22.18.346-358 [ Links ]

Delgado-Gómez, A. M., Núñez-León, J., & Leite-Méndez, A. E. (2019). Historias de vida docentes: Nuevas miradas en el tiempo. In M. J. Márquez-García, P. Cortés-González, A. E. Leite-Méndez, & I. J. Espinosa-Torres (Coords.), Narrativas de vida en educación: Diálogos para el cambio social (pp. 173-201). Octaedro. [ Links ]

De Riba Mayoral, S. (2020). (Seguir) teorizando los afectos y las emociones en la investigación educativa desde enfoques feministas. Feminismos, (35), 321-338. https://doi.org/10.14198/fem.2020.35.12 [ Links ]

Díez-Palomar, J., & Flecha-García, R. (2010). Comunidades de aprendizaje: Un proyecto de transformación social y educativa. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 67(24), 19-30. https://www.comunidadedeaprendizagem.com/uploads/materials/207/db4536339d4a36b793cf1be99cc8815d.pdf [ Links ]

Estalayo Bielsa, P., Hernández-Hernández, F., Lozano-Mulet, P., & Sancho, J. M. (2022). Ética y pedagogías de los cuidados en las escuelas de Barcelona: Posibilidades, cuestionamientos y resistencias. Revista Izquierdas, (51), 1-23. [ Links ]

Fernández, L., & Montero, I. (2012). El teatro como oportunidad. Rigden Edit. [ Links ]

Feu, J., & Torrent, A. (2021). Renovación pedagógica, innovación y cambio en educación: ¿de qué estamos hablando? In J. Feu, X. Besalú, & J. M. Palaudàrias (Coords.), La renovación pedagógica en España: Una mirada crítica y actual (pp. 19-54). Ediciones Morata. [ Links ]

Fontana, A. C., & Frey, J. H. (2015). La entrevista. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. Lincoln (Coords.), Manual de investigación cualitativa (vol. 4, pp. 140-202). Gedisa. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogia do oprimido. Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (2002). Cartas a quien pretende enseñar. Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Galak, E., & Almeida, F. Q. de. (2020). Perspectivas epistemológicas para pensar a educação física e a educação do corpo. In E. Galak, P. Athayde, & L. Lara (Orgs.), Por uma epistemologia da educação dos corpos e da educação física (Coleção Ciências do esporte, educação física e produção do conhecimento em 40 anos de CBCE, 3) (pp. 7-13). EDUFRN. https://repositorio.ufrn.br/handle/123456789/29064 [ Links ]

García-Huidobro, R. (2016). Diálogos, desplazamientos y experiencias del saber pedagógico: Una investigación biográfica narrativa con mujeres artistas-docentes [Tesis de doctorado]. Universitat de Barcelona. http://hdl.handle.net/10803/396195 [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1995). Modernidad e identidad del yo: El yo y la sociedad en la época contemporánea. Península. [ Links ]

Giroux, H. A. (2015). Pedagogías disruptivas y el desafío de la justicia social bajo regímenes neoliberales. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social (RIEJS), 4(2), 13-27. https://revistas.uam.es/riejs/article/view/2368 [ Links ]

Gómez, S. N., Gallo, L. E., & Planella-Ribera, J. (2017). Una educación poética del cuerpo de lenguajes estético pedagógicos. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad, 30(1), 179-194. https://doi.org/10.5209/ ARIS.57351 [ Links ]

Greene, M. (2005). Liberar la imaginación: Ensayos sobre educación, arte y cambio social. Editorial GRAÓ. [ Links ]

Hernández-Hernández, F., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2019). Sobre los sentidos y lugares del aprender en la vida de los docentes y sus consecuencias para la formación del profesorado. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 23(4), 68-87. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v23i4.11510 [ Links ]

Hernández-Hernández, F., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2020). La investigación sobre historias de vida: De la identidad humanista a la subjetividad nómada. Márgenes: Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Málaga, 1(3), 34-45. https://doi.org/10.24310/mgnmar.v1i3.9609 [ Links ]

Leite-Méndez, A. E. (2011). Historias de vida de maestros y maestras: La interminable construcción de las identidades: Vida Personal, Trabajo y Desarrollo Profesional [Tesis de doctorado, Universidad de Málaga]. Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad de Málaga. http://hdl.handle.net/10630/4678 [ Links ]

Leite-Méndez, A. E., & Rivas-Flores, J. I. (2021). Una mirada rizomática de las narrativas. Rutas de Formación: Prácticas y Experiencias, (12), 14-26. https://doi.org/10.23850/24631388.n12.2021.3804 [ Links ]

Leite-Méndez, A. E., Rivas-Flores, J. I., & Cortés-González, P. (2019). Narrativas, enseñanza y universidad. In M. C. Rinaudo, P. V. Paoloni, & E. B. Martín, Comunidades: Estudios y experiencias sobre contextos y comunidades de aprendizaje (pp. 63-73). Eduvim. [ Links ]

López, A. (2002). La disolución del patriarcado. In M. M. Montoya (Ed.), Escuela y educación, ¿hacia dónde va la libertad femenina? (pp. 159-170). Horas y Horas. [ Links ]

López, A. (2013). Un movimiento interior de vida. In J. Contreras, & N. Pérez de Lara (Comps.), Investigar la experiencia educativa (2a ed., pp. 211-224). Morata. [ Links ]

Mañeru-Méndez, A. (2006). Sosiego y placer en la educación. In A. M. Piussi, & A. Mañeru-Méndez (Coords.), Educación, nombre común femenino (pp. 66-76). Octaedro. [ Links ]

Miranda e Silva, N. (2022). Grounded theory para iniciantes: Contributo para a investigação em educação. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 52, Artigo e08563. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053148563 [ Links ]

Montes-Rodríguez, R., Fernández-Martín, A. & Massó-Guijarro, B. (2020). Disrupción pedagógica en educación secundaria a través del uso analógico de Instagram: #Instamitos, un estudio de caso. Revista Complutense de Educación, 32(3), 427-438. https://doi.org/10.5209/rced.70399 [ Links ]

Noblet, B. (2022). Historia de una construcción social: La mujer en los manuales de la dictadura franquista. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 52, Artículo e08781. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053148781 [ Links ]

Orozco, S., Pañagua, L., & Martos, M. V. (2021). La creación curricular en la formación de educadores. Una exploración sobre las relaciones educativas. Aula Abierta, 50(3), 737-744. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.50.3.2021.737-744 [ Links ]

Pallarès-Piquer, M., & Planella-Ribera, J. (2019). Narrare necesse est: Por una pedagogía del relato. Revista Cadmo, 2, 76-99. https://doi.org/10.3280/CAD2019-002011 [ Links ]

Paredes-Labra, J. (2013). Las emociones de nuestro proyecto en nuestra clase. Un caso de formación de docentes en la universidad. In J. Paredes Labra, F. Hernández-Hernández, & J. M. Correa-Gorospe (Eds.), La relación pedagógica en la universidad, lo transdisciplinar y los estudiantes: Desdibujando fronteras, buscando puntos de encuentro (pp. 211-222). Depósito Digital UAM. http://hdl.handle.net/10486/13152 [ Links ]

Parra-Ortíz, J. M. (2009). La evolución de la enseñanza primaria y del trabajo escolar en nuestro pasado histórico reciente. Tendencias Pedagógicas, (14), 145-157. [ Links ]

Penac, D. (2017). Mal de escuela (2a ed.). Debolsillo. [ Links ]

Pisano, M. (2010). No seguir en la misma. Epistemología Feminista (pp. 68-72). Alianza. [ Links ]

Planella-Ribera, J. (2017). Pedagogías sensibles: Sabores y saberes del cuerpo y la educación. Pedagogies UB. [ Links ]

Planella-Ribera, J., & Jiménez, J. (2019). Gramáticas de un mundo sensible. De corpógrafos y corpografías. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana: Revista Internacional de Filosofía y Teoría Social, (87), 16-26. [ Links ]

Prados-Megías, M. E. (2020a). Los lenguajes del cuerpo: Escenarios para interpretar la institución educativa. Revista Infancia, Educación y Aprendizaje, 6(1), 37-56. https://revistas.uv.cl/index.php/IEYA/article/view/1934 [ Links ]

Prados-Megías, M. E. (2020b). Pensar el cuerpo: De la expresión corporal a la conciencia expresivocorporal, un camino creativo narrativo en la formación inicial del profesorado. Revista Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 37, 703-711. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v37i37.74256 [ Links ]

Prados-Megías, M. E., & Rivas-Flores, J. I. (2017). Investigar narrativamente en educación física con relatos corporales. Revista del Instituto de Investigaciones en Educación, 8(10), 82-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.30972/riie.8103654 [ Links ]

Prendes-Espinosa, M. P. E., & Cerdán, F. C. (2021). Tecnologías avanzadas para afrontar el reto de la innovación educativa. RIED: Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 24(1), 35-53. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.24.1.28415 [ Links ]

Poveda, D. (2018). Teatro con corazón. In M. E. Prados-Megías, M. J. Marquéz-García, & D. Padua-Arcos (Coords.), Otra pedagogía en movimiento: Dialogando con la experiencia en la formación inicial (pp. 99-110). Edual. [ Links ]

Quiles-Fernández, E., & Forés, A. (2013). Voces en la educación: (Des)conocidas, (des)encontradas, compartidas. In J. Paredes-Labra, F. Hernández-Hernández, & J. M. Correa-Gorospe, La relación pedagógica en la universidad, lo transdisciplinar y los estudiantes: Desdibujando fronteras, buscando puntos de encuentro (pp. 223-232). Depósito Digital UAM. http://hdl.handle.net/10486/13152 [ Links ]

Recasens-Belenguer, L., Marín-Suelves, D., & Gabarda-Méndez, V. (2022). El teatro como herramienta para el desarrollo de las habilidades sociales y la inclusión educativa. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 33(1), 128-147. https://doi.org/10.5944/reop.vol.33.num.1.2022.33770 [ Links ]

Rivas-Flores, J. I. (2021). Cambiando de paradigma. Otra investigación necesaria, para otra educación necesaria. In L. Alvarez, O. Azmitia, A. Casali, P. Castillo, R. Castillo, F. Correa, M. Chokler, A. Dotres, A. Elizalde, J. M. Flores, L. Gaitán, J. P. Garrido, G. Guevara, W. Kohan, M. Kuperman, J. Larrosa, S. López de Maturana, M. López Melero, I. Lo Priore, & L. M. Yáñez (Comp.; Ed.), Círculos pedagógicos, espacios y tiempos de emancipación (pp. 177-182). Nueva Mirada Ediciones. [ Links ]

Rivas-Flores, J. I. (2022). Construir identidades docentes transformadoras: La necesidad de otra formación del profesorado. In M. S. Saavedra (Coord.), Horizóntica 2021. La Utopía posible (pp. 42-57). Editorial Escuela Normal Superior de Michoacán. [ Links ]

Rivas-Flores, J. I., Leite-Méndez, A., & Cortés-Gonzáles, P. (2014). Formación del profesorado y experiencia escolar: Las historias de vida como práctica educativa. Praxis Educativa, 18(2), 13-23. [ Links ]

Rivas-Flores, J. I., Leite-Méndez, A., & Prados-Megías, M. E. (2014). Algunas reflexiones para abrir caminos. In J. I. Rivas-Flores, A. E. Leite-Méndez, & M. E. Prados-Megías (Coords.), Profesorado, escuela y diversidade: La realidad educativa desde una mirada narrativa (pp. 15-19). Aljibe. [ Links ]

Rivera-Garretas, M. M. (2012). El amor es el signo: Educar como educan las madres. Sabina Editorial. [ Links ]

Rivera-Vargas, P., Ferrante, L., & Herrera-Urizar, G. (2022). Pedagogías del conflicto para la emancipación: Tensionando los conocimientos regulados y el sentido común en la escuela. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 11(2), 119-134. https://doi.org/10.15366/riejs2022.11.2.007 [ Links ]

Robles-Sajuán, V. (Ed.), García-Gomez, T., Martínez-Rebolledo, A., Rabazas-Romero, T., Reyes-Ruiz, N., & Villamor-Moreno, P. (2018). Educadoras en tiempos de transición. Catarata. [ Links ]

Rogowska-Stangret, M. (2017). Corpor(e)al cartographies of new materialism: Meeting the elsewhere halfway. The Minnesota Review, 88(1), 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1215/00265667-3787390 [ Links ]

Ruiz, M., & Pisano-Casala, P. (2020). Los cuerpos en los procesos de formación docente inicial en Educación Física. ¿Cómo se observan y comprenden? Revista Albuquerque, 12(23), 131-152. https://doi.org/10.46401/ajh.2020.v12.9781 [ Links ]

Sánchez-Sánchez, M., Prados-Megías, M. E., Maldonado-Mora, B. A., Marqués-García, M. J., & Padua- -Arcos, D. (2018). Cuentos y poemas infantiles como estrategias para profundizar en la entrevista narrativa. In B. González, M. Mañas, P. Cortés, & A. De la Morena (Coords.), 3rd international summerworkshop on alternative methods in social research Transformative and Inclusive Social and Educational Research (pp. 22-27). Universidad de Málaga. https://hdl.handle.net/10630/15290 [ Links ]

Sancho-Gil, J. M., & Correa-Gorospe, J. M. (2016). Aprender a enseñar: La constitución de la identidad del profesor en la educación infantil y primaria. Movimento, 22(2), 471-484. [ Links ]

Santaella-Rodriguéz, E., & Martínez-Heredia, N. (2018). El texto libre, una herramienta para el aprendizaje creativo. Revista Complutense de Educación, 29(2), 613-625. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.53527 [ Links ]

Santos, B. D. S. (2018). Justicia entre saberes: Epistemologías del sur contra el epistemicidio. Morata. [ Links ]

Santos, B. D. S. (2019, 4 de noviembre). Educar entre la por il’esperanza. Conferencia Internacional de Investigación en Educación. Instituto de Investigación en Educación, Universitat de Barcelona. Barcelona, España, 1. [vídeo]. UBTV - La televisió de la Universitat de Barcelona. https://www.ub.edu/ubtv/video/conferencia-boaventura-de-sousa-ired-2019 [ Links ]

Serra, C. (2018). Leonas y zorras: Estrategias políticas feministas. Catarata. [ Links ]

Suárez. D. H., & Dávila V. (2018). Documentar la experiencia biográfica y pedagógica: La investigación narrativa y (auto)biográfica en educación en Argentina. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa (Auto)Biográfica, 3(8), 350-373. https://doi.org/10.31892/rbpab2525-426X.2018.v3.n8.p350-373 [ Links ]

Tadeu, B., & Lopes, A. (2021). Early years educators in baby rooms: an exploratory study on professional identities. Early Years an International Journal of Research and Development Follow Journal, 43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2021.1905614 [ Links ]

Torrego-Egido, L., & Martínez-Scott, S. (2018). Sentido del método de proyectos en una maestra militante en los Movimientos de Renovación Pedagógica. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 21(2), 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/reifop.21.2.323181 [ Links ]

Torrego-Treviño, Y., Alcaide-Arnedillo, J. D., Chica-Diaz, M., & Pacheco-Pavón, E. (2013). Primer día de escuela. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, (436), 92-95. https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/handle/11162/97865 [ Links ]

Veltri, O. (2017). El método de la Ecología de Recursos (Ecology of Resources Method) y su aplicación para el desarrollo del conocimiento colectivo a través de las TICs. Ideas, 3(3), 149-160. https://p3.usal.edu.ar/index.php/ideas/article/view/4286 [ Links ]

Villena-Higueras, L., Sánchez-Fernández, S., & Robles-Vilchez, M. C. (2018). Expandir saberes de la infancia: El aula como espacio de participación multisensorial. In J. B. Martínez-Rodríguez, & E. Fernández-Rodriguéz (Comps.), Ecologías del aprendizaje expandida en contextos múltiples (pp. 89-106). Morata. https://issuu.com/ediciones_morata/docs/issuecologia [ Links ]

Received: February 09, 2023; Accepted: March 07, 2023

texto en

texto en