Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 0100-1574versão On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.53 São Paulo 2023 Epub 13-Set-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980531410087

BASIC EDUCATION, CULTURE, CURRICULUM

AFFECTIVE-SEXUAL EDUCATION AS A CROSSROAD IN THE RELATIONSHIP WITH FAMILY AND SCHOOL

IUniversidad de Málaga (UMA), Málaga (MA), Spain; moises@uma.es

IIUniversidad de Málaga (UMA), Málaga (MA), Spain; blas@uma.es

IIIUniversidad de Málaga (UMA), Málaga (MA), Spain; pcortes@uma.es

With the aim of understanding the existing relationship between families and schools in relation to affective-sexual education (ASE), and using a mixed methodology, we conducted in a first phase a survey with 55 parents and 43 teachers in training of the Master’s program in Secondary Education and the Bachelor’s in Early Childhood Education. Subsequently, we developed two discussion groups with 10 family members and 12 teachers. The results show what we have identified as points of convergence and agreement regarding the need for students, family members and teacher trainees to receive training in ASE, as well as divergences on how and by whom this training should be carried out. In conclusion, we proposed several final dimensions that we believe should be taken into account, and we encourage further research on this topic that is still relatively under-studied.

Key words: AFFECTIVE BEHAVIOR; GENDER RELATIONS; FAMILY EDUCATION; SCHOOL

Con el propósito de conocer la relación entre familias y escuela en relación a la educación afectivo-sexual (EAS) y desde una metodología mixta hemos desarrollado en una primera fase una encuesta a 55 padres y madres y 43 docentes en formación del Máster de Profesorado de Secundaria y del grado de Educación Infantil y posteriormente desarrollamos dos grupos de discusión con 10 familiares y 12 docentes. Los resultados muestran lo que hemos denominado puntos de encuentro y convergencia en torno a la necesidad de que el alumnado que asiste a los centros educativos, los familiares y el profesorado en formación se formen en EAS y divergencias sobre la forma y las personas que deben llevarla a cabo. Concluimos proponiendo varias dimensiones finales que consideramos que debemos tener en cuenta e instando a seguir investigando sobre esta temática que todavía sigue poco estudiada.

Palabras-clave: CONDUCTA AFECTIVA; RELACIONES DE GÉNERO; EDUCACIÓN FAMILIAR; CENTRO EDUCATIVO

Com o objetivo de conhecer a relação entre as famílias e a escola no que diz respeito à educação afetivo-sexual (EAS) e a partir de uma metodologia mista, desenvolvemos em uma primeira fase um inquérito a 55 pais e 43 professores do Mestrado em Formação de Professores em Ensino Médio e Infantil e posteriormente desenvolvemos dois grupos de discussão com 10 familiares e 12 professores. Os resultados mostram o que temos chamado de pontos de encontro e convergência em torno da necessidade de alunos que frequentam centros educativos, familiares e professores em formação para se capacitarem em EAS e divergências sobre a forma e quem deve realizá-la. Concluímos propondo algumas dimensões finais que devem ser consideradas e instando a uma maior investigação sobre essa temática ainda pouco estudada.

Palavras-Chave: COMPORTAMENTO AFETIVO; RELAÇÕES DE GÊNERO; EDUCAÇÃO FAMILIAR; CENTRO EDUCACIONAL

Afin de mieux connaître la relation entre les familles et l’école concernant l’éducation sexuelle affective (ESA), nous avons, à partir d’une méthodologie mixte, réalisé dans une première phase une enquête auprès de 55 parents et de 43 professeur.es de Master en Formation des Enseignants du Secondaire et de l’Éducation Infantile. Puis, deux groupes de discussion avec 10 parents et 12 professeur.e.s ont été mis en place. Les résultats mettent en évidence les points de rencontre et de convergence sur le besoin non seulement des élèves des centres éducatifs, mais aussi des membres de la famille et des enseignants en formation de se former à l’ESA. Ils indiquent aussi les points de divergence sur la manière de le faire, ainsi que sur les personnes devant s’en charger. La conclusion propose des considérations qui mériteraient d’être prises en compte et encourager la poursuite de la recherche sur ce sujet encore peu étudié.

Key words: COMPORTEMENTS AFFECTIFS; RELATIONS DE GENRE; ÉDUCATION FAMILIALE; CENTRE ÉDUCATIF

Sexuality is a social construct shaped by a series of social, cultural, and political dimensions (Collignon-Goribar, 2011), and it is constructed within a specific political and historical context (Granero-Andújar, 2021). As a social construct, sexuality is an inherent dimension of human beings (Bortolozzi et al., 2020), and as such, it influences personal development and has an impact on socio-affective aspects (López, 2005). Therefore, educating in sexuality becomes more than necessary (Bejarano-Franco & García-Fernández, 2016; Organización Mundial de la Salud - OMS, 2018), especially when we witness “new affirmative forms of embodying the body, gender, and sexuality” (Puche, 2021, p. 18, own translation), which are overlooked and/or rejected by various social groups and sectors of society.

Sexuality education provides opportunities to understand values and attitudes related to human sexuality (Calvo-González, 2021a) from a realistic standpoint, without value judgments, and based on scientific and rigorous information (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura - Unesco, 2014). However, despite the importance of addressing sexuality within the school and educational context, it continues to be a taboo topic (Vivas-García et al., 2017), and when affective-sexual education (ASE) is addressed in educational institutions, it is often done in a partial and inadequate manner (Martínez-Martín & Bejarano-Franco, 2021).

Therefore, despite the contributions introduced by the Ley Orgánica de Modificación de la LOE [Organic Law for the Modification of the Organic Law of Education] (LOMLOE) (Spanish education law) regarding ASE, we encounter moral, ethical, and axiological dimensions regarding who, when, what, and how ASE should be approached. In order to understand the perspectives, sensitivities, and discourse of future teachers and families, we have engaged with pre-service teachers and parents of students enrolled in different public primary and secondary schools in the province of Málaga.

Approaches, legislation, and statistics

The World Health Organization (OMS, 2018) states that affective-sexual education (ASE) is “a central aspect of being human that is present throughout life. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy, and reproduction” (p. 3, own translation). In this regard, the theoretical framework that has been developed around the concept of ASE is based on scientific evidence and aims to provide socio-educational attention to sexualities, considering a perspective of sexual diversity (Calvo-González, 2021b). This issue, which is also addressed by the 2030 Agenda, is reflected in two Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) that emphasize universal access to sexual health (Goal 5) and the need for equitable and inclusive affective-sexual education (Goal 4).

As shown in Table 1, prior to the enactment of the Ley Orgánica para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa [Organic Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality] n. 8 (LOMCE) (2013), ASE was not addressed in any previous legal provisions. The fact is evident in the findings of the National Study on sexuality and contraception in Spanish youth (Sociedad Española de Contracepción [Spanish Contraception Society] [SEC], 2019) and the study conducted by the Liga Española de La Educación [Spanish League of Education] (LEE) in 2020.

Table 1 Historical-normative overview of ASE and family involvement in schools

| Educational law | Treatment of ASE | Relationship with families |

|---|---|---|

| LOGSE (Ley Orgánica n. 1/1990) |

Does not mention Sexual Education, but includes aspects such as respect, tolerance, and discrimination. | Not mentioned. |

| LOCE (Ley Orgánica n. 10/2002) |

Includes Education for Equality, but does not mention the development of sexuality or affectivity. | Not mentioned. |

| LOE (Ley Orgánica n. 2/2006) |

“Basic competencies” are introduced, and some autonomous communities introduce the competency of “emotional education”. The preamble states: “to know and value the human dimension of sexuality in all its diversity” (Article 23, k, own translation). | Brief mention of family participation. |

| LOMCE (Ley Orgánica n. 8/2013) |

Emotional competency is removed. | Brief mention of family participation. |

| LOMLOE | ASE is included as a transversal and non-evaluable topic in Chapter I, Article 19, Section 2, under the principles and goals of education, within the framework of Health Education. Affective, sexual, emotional, and values education will be addressed transversally in all subjects. For the first time, a) ASE is mentioned as a cross-cutting theme to be addressed in all subjects, b) it is included among the pedagogical principles of Primary Education (Article 19.2), and among the objectives of Secondary Education and Baccalaureate (Article 23, k). | Recognizes parents as primary responsible agents. |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The National Study on Sexuality and Contraception in Spanish Youth (SEC, 2019) highlights the alarming current situation. In a study involving 1,200 young people aged 25 to 26, it was found that the majority of them sought information about sexuality on the internet and forums (45.5%). Other findings indicated that some participants had not engaged in sexual relationships due to fear and insecurity (15%), while others reported experiencing forced sexual encounters and even considered the morning-after pill as a regular contraceptive method (0.7%).

In accordance with these findings, a study conducted by the LEE in collaboration with the Ministry of Health (2020) surveyed 1,500 young people between the ages of 14 and 22. The study revealed that 14% of participants had attended informative talks, 21% believed that women have less desire for sex than men, 19% considered penetration as the defining factor of a sexual relationship, and 18% believed that men always experience more pleasure. Additionally, the study found that young people preferred discussing sexuality with their friends.

Families, affective-sexual education, and schools

Families are the primary agents of socialization and promoters of social relationships (De León, 2011; Parodi et al., 2019). The family, along with the internet and television, serves as the main source of information for students regarding sexuality (Bortolozzi et al., 2020). Therefore, educational approaches should consider the shared responsibility between families and educational institutions (Gubbins, 2012) as a key factor.

In this regard, we share the perspective of Parodi et al. (2019) that Epstein’s proposal (2001, 2007) contributes to improving the active participation of families by a) promoting dialogue between families, schools, and the community, b) facilitating family involvement, and c) encouraging family decision-making and its impact on the school context. This model has also served as a catalyst for authors like De León (2011) to propose new ways of improving the relationship between families and schools, advocating a) raising awareness among teachers about their role in engaging fa- milies, and b) breaking the notion of family intrusion.

Notably, the works of Epstein (2001, 2007), Epstein et al. (2019), and Blasco (2018) highlight the positive impact that family involvement has on student motivation, academic achievements, adaptation, and problem-solving. Furthermore, research studies such as those conducted by Romagnoli and Gallardo (2010) and Valenzuela Miralles and Sales Ciges (2016) demonstrate how family participation promotes positive self-esteem, reduces school absenteeism, improves grades and relationships inside and outside the classroom, collaboration, tolerance, and respect for diversity.

Despite the benefits that family involvement has on students’ development and learning, research by Parodi et al. (2019) and Valenzuela Miralles and Sales Ciges (2016) indicates that families perceive their participation as limited due to work schedules and the challenges of work-life balance. Collaboration between families and educational institutions becomes more complex when addressing affective-sexual education. In this regard, different educational models - moral, risk-based, revolutionary, biographical, and professional - (López, 2005) considering diverse sensitivities and perspectives have been proposed. Families may not fully grasp the importance of sexuality education, which suggests that any intervention that fails to consider the contributions of both contexts is likely to be unsuccessful (Orcasita-Pineda et al., 2018). Cooperation between families and schools would foster greater trust between students and their families (LEE, 2020).

Method and focus

The research is grounded within the critical paradigm (Grundy, 1987), and for this purpose, we have employed a mixed methodology with a strong qualitative orientation (Sandín-Esteban, 2003). The main objective is to explore the perspectives and positions held by pre-service teachers from the University of Malaga (Master’s in Secondary Education and 1st-year students of Early Childhood Education) and families with school-aged children regarding ASE.

Phases, instruments, and participants

With the intention of addressing the stated objectives, we decided to plan this research based on the phases proposed by Latorre et al. (1996), which are as follows:

Phase 1: Exploration. Setting the study focus and reviewing similar research.

Phase 2: Research planning, considering accessibility to schools, families, and potential areas of study.

Phase 3: Entry. Contacting pre-service teachers and families and obtaining consent from educational institutions.

Phase 4: Data collection and analysis. Utilizing intentional (non-probabilistic) or con- venience sampling methods (Otzen & Manterola, 2017), initially administering an ad-hoc questionnaire (C) to collect general information (see Table 2), sociodemographic variables (gender, age, number of children), and participants’ perceptions of affective-sexual education (Table 2).

Table 2 Initial questions from the ad-hoc questionnaire on ASE

| Questions proposed |

|---|

| Do you value it positively when the topic of ASE is addressed in the school? |

| Do you believe that families should be involved in this education? |

| Do you think parents should talk to their children about topics related to ASE? |

| At what age do you think it is appropriate to discuss topics related to ASE? |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The research involved 55 parents (PM) of students enrolled in three public schools in the province of Malaga, and 43 teacher trainees (DF), including 24 Master’s students in Secondary Education (MP) and 19 students in the first year of Early Childhood Education (GI) at the University of Malaga. The responses from the questionnaire were subsequently used to address in-depth issues with the families in the following phase.

In this second stage, after analyzing the results of the ad hoc questionnaire and with the aim of gaining a deeper understanding of the opinions and perspectives of the families and teacher trainees, two focus groups (GD) were conducted. Three questions were proposed to stimulate participation: 1) How can families participate in their children’s ASE?; 2) What importance does ASE have in student education?; 3) What is the current and desired relationship between the family and school to contribute to ASE? The first focus group lasted approximately 75 minutes and included 10 family members (GD1: 4 men and 6 women), while the second focus group lasted 83 minutes and involved 12 teacher trainees (7 MP students and 5 GI students).

The selection of participants followed three criteria proposed by Scharager and Reyes (2001): accessibility, convenience, and voluntariness. In the second phase, the selection was made by informing the 98 participants who composed the initial sample. Additionally, following the good practice guidelines of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas [Superior Council of Scientific Investigations] (CSIC) (2021), participants were informed about anonymity, the possibility of reviewing the information, and the purpose of the research.

The data analysis

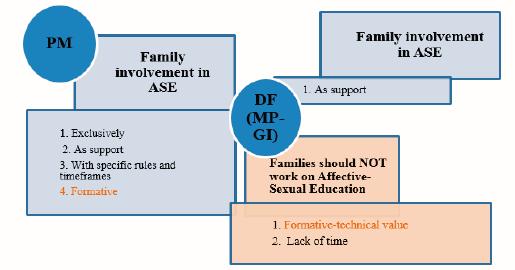

To analyze the information provided in the questionnaires, we utilized the IBM SPSS V.22 software. Subsequently, for the transcribed data from the focus group discussions, we used the qualitative analysis software Atlas.ti, version 9, to perform the process of inductive axial coding (Gibbs, 2012) (Figure 1). The information obtained from the questionnaires and focus group discussions was identified with the letters C and GD, respectively. Additionally, the codes PM and DF were used to differentiate the participation of parents and teachers in training, and within the DF group, the initials MP were used to identify students from the Master’s in Teaching program and GI for those in the Bachelor’s degree in Early Childhood Education. The analysis revealed two polarized perspectives. On one hand, in the PM focus group, families expressed their support for participating in ASE. However, in the DF focus group (MP-GI), both the support and opposition to family involvement in ASE were observed.

The analysis reveals two general categories: 1) Points of convergence and agreement from the perspective of education, and 2) Detected needs and divergences in the family-school relationship and in approaches to addressing ASE.

Results and analysis

Following the chronological process of the research development, we present in Table 3 the descriptive results of the questionnaire [Phase 4]. The findings demonstrate the significance that families attribute to ASE and how the teacher trainees positively value the involvement of families in ASE education.

Table 3 Results of the ad-hoc questionnaire

| Questions raised | Results PM | Results GI-MP |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 78.8% 37-47 years 15.2% > 48 years 3% 18-25 years 3% 26-36 years |

12.3% 37-47 years 2% > 48 years 71.2% 18-25 years 14% 26-36 years |

| Do you value the discussion of ASE at school? | 79% YES 21% NO |

91% YES 9% NO |

| Do you believe that families should be involved in this education? | 75% YES 25% NO |

25% YES 75% NO |

| Do you think parents should talk to their children about topics related to ASE? | 91% YES 9% NO |

85% YES 15% NO |

| At what age do you think it is appropriate to address topics related to ASE? | 65% Secondary Education 15% Primary Education 10% High School 10% Early Childhood |

82% Secondary Education 10% Primary Education 2% High School 6% Early Childhood |

| Participants | 55 | 43 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Points of convergence and agreement

Both families and trainee teachers agree that there is a need to improve family training in ASE. In this regard, some teachers indicate that - families should have information from qualified individuals regarding the topic - (C-DF-GI. F13:4, 55:55), because - most of the time families have a great lack of knowledge about these topics (C-DF-GI. F12:4, 55:50) -, as they believe that families are not adequately trained in ASE. Families confirm their lack of knowledge in ASE by stating that - it is a complicated issue, and I must say that the training I have regarding this topic is what I have learned through searching or from my own experience (GD-PM F13:5, 43-43) -, and - I think when they are in the last year of primary school is a good age, but I’m not sure if I will know how to address this topic with my children when the time comes (C-PM F10:3, 23-22).

All participants acknowledge the complexity of the matter and recognize that they need to be trained by professionals, as they believe that social situations, terms, socio-affective relationships, group behavior, and individual behavior have changed over time. Therefore, both groups require guidance and specialized training to address ASE.

We need to educate ourselves to understand issues that are challenging for us due to a lack of knowledge about topics such as gender, transgender, homosexuality, sex, etc., in order to help and respond to our children. (GD-PM, F24:12, 12:9).

We need to educate ourselves because there are things that escape me when I talk to my child. Moreover, it’s not like in our time when what was seen in books was enough; they need more because times change. (GD, PM, F22:10, 8:10).

It is important for families to participate, but we must be clear about which concepts and ideas should be conveyed. Not everything is acceptable or valid just because they see it that way. (GD-DF-GI, F14:3, 26-22).

Currently, I don’t feel capable of providing education in ASE to students or families. We should receive more specific training because it’s not the same working on this with young children as it is with older ones. (GD-DF-MP, F4:2, 13:5).

Both groups agree on the importance of receiving training in ASE to acquire knowledge that enables them to use information, concepts, and terms that meet the needs and concerns of the students they work with, and that are appropriate for their developmental level. This helps to avoid contradictions, the use of derogatory or xenophobic terms, and dogmatic, personal, or subjective comments. As the participants indicate, training in ASE within school settings is a valued option.

If possible, parents should participate in the training provided to teachers and be educated to address this topic at home. (GD-MP, F22:4, 20:20).

Parents have the right to know what is being taught to our children, and what better way to get involved in their education than by attending these beneficial training sessions for everyone. (GD-PM, F14:2, 23:23).

In particular, a portion of the teacher trainees believe that family training alone is not enough. They suggest that for it to be effective, coordination between educational institutions and families should be improved in order to address the same topics from different perspectives and unify the message being conveyed, as ASE is a shared responsibility.

If we want students to understand the importance of this topic, close family members and the surrounding environment must correspond with a similar message. To achieve this impact, coordination is necessary. (GD-DF-MP, F18:5, 17:17).

Families should be part of this training by sharing their knowledge and experience. It would also be very beneficial for both students and the institution, as well as the teaching staff in general, to discuss the same ideas. (GD-DF-MP, F10:2, 16:15).

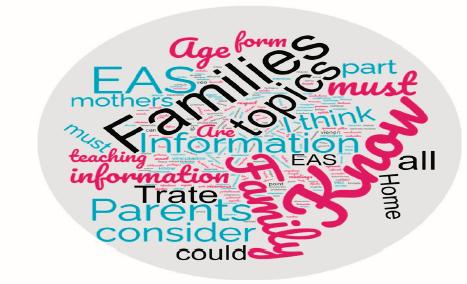

As evidenced, families and teachers emphasize the importance of training and the participation, involvement, and collaboration of both groups as key factors in improving ASE for primary and secondary school students. In this regard, Figure 2 highlights terms such as “knowledge”, “family”, “information”, “more”, or “should”, which allude to the topic of training and increasing families’ knowledge in ASE.

Detected needs or divergences of training

The complexity of addressing ASE from a shared perspective is evident in the discourses of the teacher training participants, as some of them are opposed to the involvement of families. They argue that the lack of training among families is a key reason for ASE to be exclusively addressed within educational institutions. Thus, these teachers display an inflexible and power-oriented discourse and stance towards families.

We, or rather qualified individuals, should be the ones participating in this. Families, I believe, can confuse things even more. (C-DF-MP, F58:58, 14:12).

Many families are not prepared or interested in addressing these topics, so it’s better to work on them directly from the school. (C-DF-MP, F28:7, 8:8).

I’m not sure if families should also be familiar with the content being taught or not. Many families lack the training to address these topics and provide confidence to their children. (GD-DF-MP, F36:3, 17:17).

Similarly, some teacher training participants believe that allowing families to partici- pate in their children’s ASE could be detrimental. They argue that it is better to exclusively address ASE within educational institutions because families may convey contradictory and subjective messages.

I doubt that families will be able to provide the necessary approach to address this freely and without taboos. It’s better to leave this task to educational institutions. (GD-DF-GI, F36:8, 17:17).

Their [families’] conversations at home will likely discuss other things using language that aligns with their own way of thinking and understanding sexual education, sending messages contrary to what is taught in school. (GD-DF-MP, F31:4, 20:10).

On the other hand, some families express a traditional discourse, believing that ASE should be addressed from both the school and the family perspectives. They argue that certain topics and content should be addressed by families.

We [families] should teach all of this alongside the school. There are topics that I believe will be difficult to explain in the same way in class, so it’s better for each side to handle their own part. (GD-PM, F34:4, 12:12).

I don’t understand why we need to merge perspectives because the school should not interfere with how I educate my children about sexuality. (GD-PM, F25:25, 1:3).

When teacher training participants were asked about the relationship between families and schools in contributing to ASE, many expressed an attitude and discourse opposing the participation and collaboration of families in joint activities or workshops in educational institutions, and for that reason they indicate:

I doubt I would call parents to come and participate. It could lead to trouble, with parents saying this or that... If it’s not mentioned anywhere, I don’t think I would do it. (GD-DF-MP, F41:2, 14:14).

I wouldn’t feel comfortable if some parents started expressing different opinions and sharing things that are different from what we [teachers] intend. They are not prepared for that, and I also think it would undermine the respect of the class. (GD-DF-MP, F24:2, 10:10).

In the schools I have been to, no one has mentioned that we should involve families when addressing these topics. Besides, these topics are rarely discussed, and no one has brought in family members. I’m not sure if it’s mentioned anywhere. (GD-DF-MP, F31:6, 13:13).

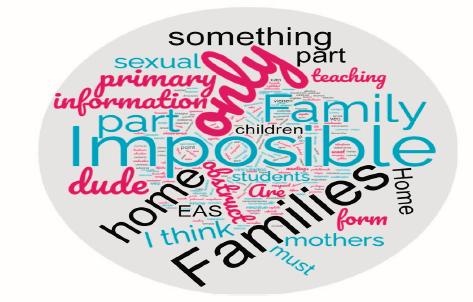

As evident from the findings, many families and teachers, especially those in teacher training programs of the Teaching master’s Degree, hold perspectives that are opposed to collaborative approaches and unified positions and terminology in addressing ASE. Both perspectives express the divergences and discrepancies surrounding such a complex and controversial topic as ESD for primary and secondary education students (Figure 3).

Discussion and conclusions

Based on the evidence presented, there are both convergences and divergences regarding how pre-service teachers and parents perceive and approach ASE. Both groups agree on the need for improved training in ASE for both families and teachers. However, there are differing opinions on who should take responsibility for ASE and how it should be addressed.

Regarding the first dimension, and as evidenced by other research, it is observed that pre-service teachers demonstrate limited knowledge in ASE due to a lack of initial university training (Martínez et al., 2013). Similarly, the work conducted by Martínez et al. (2011) indicates the scarcity of continuing education programs in ASE, factors that largely contribute to either the omission of ASE in educational institutions due to lack of teacher training or the integration of ASE with subjective teaching discourses. Furthermore, ASE training should align with specific curricular elements, as the few ASE-related topics covered in educational institutions have historically focused on moralistic and biologistic perspectives through subjects such as Religion and Biology (Calvo-González, 2021a; Martínez-Martin & Bejarano-Franco, 2021; Mañas Olmo & González Alba, 2022) or through cross-cutting elements like Health Education, Peace Education, or Gender Equality (Garzón-Fernández, 2016). It is noteworthy that families express their limitations in addressing ESE with their children and demand training from professionals. The limited ESE training for families is a reality also highlighted in studies conducted by Shin et al. (2019) and Jin (2011).

The divergence arises when discussing who should be responsible for ASE. While a majority of participants believe that parents should be responsible for sexual education, there is also a lack of trust between schools and families. This may be due to discomfort or embarrassment that parents experience in discussing these topics outside the family environment (Lee & Kweon, 2013). Recognizing the need for training in this area is crucial for creating openness, overcoming fears and prejudices, and building trust between families, educational institutions, and children (Jerman & Constantine, 2010; Jin, 2011).

ASE is influenced by factors such as school culture, country ideology, morality, and religion, it is also acknowledged in scholarly literature that comprehensive sexual education is a collaborative and constructive process that necessitates the involvement of both educational institutions and families (Movilla-Ricaurte, 2022). However, it is a constructive process that should involve both schools and families. Many families and teachers adhere to a moralistic view of sexual education (Fallas-Vargas et al., 2012), which is associated with different approaches to ASE, such as the moral model, the risk model, the revolutionary model, and the biographical and professional model (López, 2005). The latter model emphasizes information, critical attitudes, and the joint participation of families, students, school counselors, and teachers across all educational stages.

In conclusion, both pre-service teachers and families recognize the importance of training in ASE for their respective roles. It is important to reflect on these findings and consider several final dimensions.

Considering ASE in the initial training of teachers from an inclusive-critical paradigm of social and democratic reconstruction (Bejarano-Franco & Mateos-Jiménez, 2015).

Including ASE formally in the school curriculum, rather than just as a transversal element, and addressing it as a subject built on scientific evidence with a perspective of improving public health and contributing to social justice (Calvo-González, 2021a). This involves reviewing the curriculum to incorporate ASE content (Gómara & De Irala, 2006; Martínez-Martín & Bejarano-Franco, 2021).

Facilitating the training and involvement of families in students’ ASE (Mañas Olmo & González Alba, 2022).

ASE is a topic that has received limited research due to its complexity and controversy. On one hand, it is an important aspect of students’ education. On the other hand, there are differing opinions on what, when, how, and by whom it should be addressed. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the knowledge and perspectives of the educational community in order to develop a school project that takes into account their differences and provides evidence-based training. Although this study has some limitations, its results indicate the need to reconsider certain aspects and encourage other researchers to expand this field of study.

REFERENCES

Bejarano-Franco, M., & García-Fernández, B. (2016). La educación afectivo-sexual en España. Análisis de las leyes educativas en el periodo 1990-2016. Opción, 32(13), 756-789. [ Links ]

Bejarano-Franco, M., & Mateos-Jiménez, A. (2015). La educación afectivo-sexual en el sistema educativo español: Análisis normativo y posibilidades de investigación. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, 10(2), 1507-1522. https://doi.org/10.21723/riaee.v10i6.8334 [ Links ]

Blasco, J. (2018). ¿Los programas para fomentar la implicación parental en la educación sirven para mejorar el rendimiento escolar? Fundación Jaume Bofill e Institut Catalá d’Avaluació de Polítiques Públiques. https://fundaciobofill.cat/uploads/docs/i/q/w/2/j/a/b/k/7/que_funciona_11_implicacionparental021018.pdf [ Links ]

Bortolozzi, C., Spadotto, L., & Vilaca, T. (2020). Educação sexual inclusiva na perspectiva de professores(as): Análise do contexto português e brasileiro. Humanidades e Innovación, 7(27), 33-46. [ Links ]

Calvo-González, S. (2021a). Educación sexual con enfoque de género en el currículo de la educación obligatoria en España: Avances y situación actual. Educatio Siglo XXI, 39(1), 281-304. https://doi.org/10.6018/educatio.469281 [ Links ]

Calvo-González, S. (2021b). Educación sexual. Magister, 33(1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.17811/msg.33.1.2021.1-2 [ Links ]

Collignon-Goribar, M. M. (2011). Discursos sociales sobre la sexualidad: narrativas sobre la diversidad sexual y prácticas de resistencia. Comunicación y Sociedad, 8(16), 133-160. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v0i16.1118 [ Links ]

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC). (2021). Código de Buenas Prácticas Científicas del CSIC. Ministerio de Ciencias y Educación. [ Links ]

De León, B. (2011). La relación familia-escuela y su repercusión en la autonomía y responsabilidad de los niños/as. In Anales, 12 Congreso Internacional de Teoría de la Educación (pp. 1-20). Universidad de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Epstein, J. L. (2001). Building bridges of home, school, and community: The importance of design. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 6(1), 161-168. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327671ESPR0601-2_10 [ Links ]

Epstein, J. L. (2007). Improving family and community involvement in secondary schools. Principal Leadership, 73(6), 9-12. [ Links ]

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., Van Voorhis, F. L., Martin, C. S., Thomas, B. G., Greenfeld, M. D., Hutchins, D. J., & Williams, K. J. (2019). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Fallas-Vargas, M. A., Artavia-Aguiar, C., & Gamboa-Jiménez, A. (2012). Educación sexual: Orientadores y orientadoras desde el modelo biográfico y profesional. Revista Electrónica Educare, 16, 53-71. [ Links ]

Garzón-Fernández, A. (2016). La educación sexual, una asignatura pendiente en España. Biografía, 9(16), 195-203. https://doi.org/10.17227/20271034.vol.9num.16bio-grafia195.203 [ Links ]

Gibbs, G. (2012). Axial coding: An approach to the analysis of qualitative data. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (pp. 327-355). Sage. [ Links ]

Gómara, U., & De Irala, J. (2006). La educación sexual a examen: Análisis de textos escolares sobre educación sexual. Informe de proyecto de investigación del Instituto de Ciencias para la Familia. Universidad de Navarra. http://www.unav.es/icf/main/investigacion7.htm [ Links ]

Granero-Andújar, A. (2021). Exclusiones y discriminaciones hacia las identidades trans en educación afectivo-sexual. Aula Abierta, 50(4), 833-840. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.50.4.2021.833-840 [ Links ]

Grundy, S. (1987). Producto o praxis del currículo. Morata. [ Links ]

Gubbins, V. (2012). Familia y escuela: Tensiones, reflexiones y propuestas. Reflexiones Pedagógicas, (46), 64-73. [ Links ]

Jerman, P., & Constantine, N. A. (2010). Demographic and psychological predictors of parent-adolescent communication about sex: A representative statewide analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1164-1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9546-1 [ Links ]

Jin, H. S. (2011). Sexual knowledge and perception and current status of sex education among parents of first and second grade elementary schoolers [Master’s thesis]. The Catholic University of Korea. [ Links ]

Latorre, A., Rincon, D, & Arnal, J. (1996). Bases metodológicas de la investigación educativa. Experiencia. [ Links ]

Lee, E. M., & Kweon, Y. R. (2013). Effects of a maternal sexuality education program for mothers of preschoolers. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 43(3), 370-378. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2013.43.3.370 [ Links ]

Ley Orgánica n. 1, de 3 de octubre de 1990. (1990). Ordenación General del Sistema Educativo. Boletín Oficial del Estado, (286), 32032-32059. https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1990-23152 [ Links ]

Ley Orgánica n. 2, de 3 de mayo de 2000. (2000). Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, (170), 1-51. https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2006-9072 [ Links ]

Ley Orgánica n. 10, de 23 de diciembre de 2002. (2002). Calidad de la Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, (310). https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2002-25355 [ Links ]

Ley Orgánica n. 8, de 9 de diciembre de 2013. (2013). Para la mejora de la calidad educativa. Boletín Oficial del Estado, (295). [ Links ]

Liga Española de la Educación y la Cultura Popular (LEE). (2020). La salud integral de adolescentes y jóvenes. Educando la sexualidad. Imaginarios, nuevas prácticas sexuales y sus consecuencias. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. [ Links ]

López, F. (2005). La educación sexual. Biblioteca Nueva. [ Links ]

Mañas Olmo, M., & González Alba, B. (2022). La educación afectivo sexual en los centros educativos: A propósito de un estudio con profesorado en formación. ReiDoCrea, 11(30), 355-367. https://www.ugr.es/~reidocrea/11-30.pdf [ Links ]

Martínez, J. L., González, E., Vicario-Molina, I., Fernández-Fuertes, A. A., Carcedo, R. J., Fuertes, A., & Orgaz, B. (2013). Formación del profesorado en educación sexual: Pasado, presente y futuro. Magister, 25(1), 35-42. [ Links ]

Martínez, J. L., Orgaz, B., Vicario-Molina, I., González, E., Carcedo, R., Fernández-Fuertes, A. A., & Fuertes, A. (2011). Educación sexual y formación del profesorado en España: Diferencias por sexo, edad, etapa educativa y comunidad autónoma. Magister, (24), 37-47. [ Links ]

Martínez-Martín, I., & Bejarano-Franco, M. T. (2021). Educación en sexualidad e igualdad: Conocimientos y desafíos en la formación docente. Revista Humanidades e Innovação, 7(27), 134-148. [ Links ]

Movilla-Ricaurte, N. (2022). Educación integral de la sexualidad: Un desafío curricular inaplazable para las instituciones educativas. Revista arbitrada del CIEG - Centro de Investigación y Estudios Gerenciales, (53), 310-321. [ Links ]

Orcasita-Pineda, L. T., Cuenca, J., Montenegro-Cespedes, J. L., Garrido-Rios, D., & Haderlein, A. (2018). Diálogos y saberes sobre sexualidad de padres con hijos e hijas adolescentes escolarizados. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 27(1), 41-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v27n1.62148 [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (Unesco). (2014). Educación integral de la sexualidad: Conceptos, enfoques y competencias. Unesco. [ Links ]

Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). (2018). La salud sexual y su relación con la salud reproductiva: Un enfoque operativo. OMS. [ Links ]

Otzen, T., & Manterola, C. (2017). Técnicas de Muestreo sobre una Población a Estudio. International Journal of Morphology, 35(1), 227-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022017000100037 [ Links ]

Parodi, L., Santos-Villalba, M. J., Olmo-Fernández, M. J. A. del, & Isequilla-Alarcón, E. (2019). El desafío educativo del siglo XXI: Relevancia de la cooperación entre familia y escuela. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 12(24), 19-29. [ Links ]

Puche, L. (2021). Hacia una (co)educación sexual inclusiva. Aportes desde la investigación sobre infancia y juventud trans. Magister, 33, 17-23. [ Links ]

Romagnoli, C., & Gallardo, G. (2010). Alianza Efectiva Familia Escuela: Para promover el desarrollo intelectual, emocional, social y ético de los estudiantes. Valore UC. https://centroderecursos.educarchile.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12246/53167/23%20si%20Alianza%20Familia%20Escuela.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Sandín-Esteban, M. P. (2003). Investigación cualitativa en educación: Fundamentos y tradiciones. McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Scharager, J., & Reyes, P. (2001). Muestreo no probabilístico. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Escuela de Psicología, 1, 1-3. [ Links ]

Shin, H., Lee, J. M., & Min, J. Y. (2019). Sexual knowledge, sexual attitudes, and perceptions and actualities of sex education among elementary school parents. Child Health Nursing Research, 25(3), 312. [ Links ]

Sociedad Española de Contracepción (SEC). (2019). Estudio sobre sexualidad y anticoncepción: Jóvenes españoles. Sigmados. [ Links ]

Valenzuela Miralles, C., & Sales Ciges, M. A. (2016). Los efectos de la participación familiar dentro del aula ordinaria. Revista nacional e internacional de educación inclusiva, 9(2), 71-86. https://revistaeducacioninclusiva.es/index.php/REI/article/view/288 [ Links ]

Vivas-García, M., Cuberos, M. A., Albornoz-Arias, N., Mazuera-Arias, R., & Carreño-Paredes, M. T. (2017). Escuela y familia, vínculo indisoluble en la educación sexual de los niños y adolescentes. In N. Albornoz-Arias, R. Mazuera-Arias, & J. F. Espinosa-Castro (Eds.), Adolescencia: Su relación con la familia, educación y sexualidad (pp. 103-134). Universidad Simón Bolívar. https://bonga.unisimon.edu.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.12442/2817/Cap_3%20Escuela%20y%20familia.pdf?sequence=7&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Received: February 17, 2023; Accepted: June 05, 2023

texto em

texto em