Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.53 São Paulo 2023 Epub 02-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053149934

BASIC EDUCATION, CULTURE, CURRICULUM

“NOT A BOX!”: TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE SENSES ASSIGNED TO A CARDBOARD BOX

IUniversidade do Estado de Minas Gerais (UEMG), Belo Horizonte (MG), Brazil;

IIUniversidade do Estado da Bahia (UNEB), Guanambi (BA), Brazil;

III, VUniversidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte (MG), Brazil;

This article argues that play is an activity that produces subjectivities, meanings, narratives, and, therefore, human consciousness in historically and culturally situated conditions. From the historical-cultural theory and ethnography in education, we argue that play is an act of creating possibilities, both for participation in the social group and for the production of meanings for what happens in collective life, through the analysis of creation meanings for a cardboard box in the event “Não é uma caixa!” [“Not a box!”]. We conclude that play creates contradictions between the perceptive, narrative, and imaginary fields, expanding the possibilities of action, language, and social relations, which drives the cultural development of children.

Key words: PLAY; IMAGINATION; HISTORICAL-CULTURAL THEORY; ETHNOGRAPHY

Este artigo tem como objetivo argumentar que a brincadeira é uma atividade de produção de subjetividades, significações, narrativas e, portanto, de consciência humana em condições histórica e culturalmente situadas. A partir da teoria histórico-cultural e da etnografia em educação, discutimos que a brincadeira é um ato de criação de possibilidades, tanto de participação no grupo social como de produção de sentidos para o que acontece na vida coletiva, por meio da análise de criação de sentidos para uma caixa de papelão no evento “Não é uma caixa!”. Concluímos que a brincadeira cria contradições entre os campos perceptivo, narrativo e imaginário, ampliando as possibilidades de ação, linguagem e relações sociais, o que impulsiona o desenvolvimento cultural das crianças.

Palavras-Chave: BRINCADEIRA; IMAGINAÇÃO; TEORIA HISTÓRICO-CULTURAL; ETNOGRAFIA

Este artículo tiene como objetivo argumentar que el juego es una actividad de producción de subjetividades, significados, narrativas y, por tanto, conciencia humana en condiciones histórica y culturalmente situadas. A partir de la teoría histórico-cultural y de la etnografía en educación, discutimos que el juego es un acto de creación de posibilidades, tanto de participación en el grupo social como de producción de significados para lo que sucede en la vida colectiva, a través del análisis de la creación de significados para un caja de cartón en el evento “¡Não é uma caixa!” [“¡No es una caja!”]. Concluimos que el juego crea contradicciones entre los campos perceptivo, narrativo e imaginario, ampliando las posibilidades de acción, lenguaje y relaciones sociales, lo que impulsa el desarrollo cultural de los niños.

Palabras-clave: JUEGO; IMAGINACIÓN; TEORÍA HISTÓRICA Y CULTURAL; ETNOGRAFÍA

L’objectif de cet article est de démontrer que, dans des conditions historiques et culturelles données, les jeux produisent des subjectivités, des significations, des récits et, par conséquent, une conscience humaine. À partir de la théorie historico-culturelle et de l’ethnographie de l’éducation, nous considérons que les jeux sont un acte de création de possibilités, non seulement de participation dans le groupe social mais aussi de production des significations pour tout ce qui se passe dans la vie collective. En partant de l’événement intitulé «Não é uma caixa!» [«Ceci n’est pas une boîte!»], la recherche vise à analyser la création de significations pour une boîte en carton. Nous concluons que les jeux créent des contradictions dans les domaines perceptif, narratif et imaginaire qui élargissent les possibilités d’action, de langage et de relations sociales, favorisant ainsi le développement culturel des enfants.

Key words: JEUX; IMAGINATION; THÉORIE HISTORIQUE ET CULTURELLE; ETHNOGRAPHIE

On a warm afternoon in February, teacher Rita and her students wrapped UP a class discussion at the Escola Municipal de Educação Infantil de Belo Horizonte [Municipal Ealy Childhood Center in Belo Horizonte] (EMEI Tupi). After the teacher gave several large cardboard boxes, two children, Larissa (2y 8m)1 and Simone (2y 9m), took one of the boxes to a corner of the room.2 During the next 18 minutes, they played with the box and assigned it various meanings such as a bathtub, basket, drum, protection from the big bad wolf, and ball pit. They also created a narrative involving acts of caring, wherein they took on roles of mother and daughter, washed each other’s hair, hugged, and protected each other.pitWhat prompted the two girls to engage in this game for a long period of time? How did the game unfold? What meanings did the children attribute to the box? Where do such meanings come from? These issues are addressed in this article, shedding light on [action/imagination] as a unit of analysis of the activity of playing (Silva, 2021) in children’s cultural development (Vigotski, 2021).

Just like in the book Não é uma caixa3 (Portis, 2006), the cardboard box became a pivotal object for the play activity (Vigotski, 2021), separating the meaning of the object and allowing new meanings to be created by the two girls. Furthemore, the different meanings attributed to the box allowed the creation, through [action/imagination], of a narrative whose theme relates to care in the relationship between mother and daughter, as one may see in the next sections of this article.

In the field of the sociology of childhood, play constitutes peer cultures and is understood as the child’s privileged way of appropriating, (re)interpreting, and (re)producing new/old versions of the world (Corsaro, 2003; Borba, 2009). From this theoretical perspective, the child is seen as a social actor who acts and participates in their own socialization. Additionally, the children’s remarkable ability to interpret and transform their cultural heritage is noteworthy. Based on the ethnographic approach, the study of childhood cultures, with an emphasis on play, makes it possible to understand the processes of interpretative reproduction and the ways of inserting oneself into the world. Sarmento (2005, p. 26, own translation) warns that “childhood cultures only make sense if we effectively consider the social construction of childhood, that is, if we analyze the social conditions in which children live and interact”.

In contemporary scientific production, there are studies that regard play as a child’s way of acting in the world (Bragagnolo et al., 2013; Rivero & Rocha, 2017), as an activity rich in possibilities for children’s development (Marcolino & Mello, 2015) in the relationship with other people and materiality. Thus, through these actions, there would be the possibility of creating ways of being in the world (Góes, 2000; Rivero & Rocha, 2017) and sharing social meanings (Teixeira, 2013). In other words, it is a two-step process by which a child is introduced to and becomes a part of their cultural community (Brougére, 2010). The activity of playing is constituted by imagination, and children, when engaging in make-believe activities, create new and complex imaginary situations (Marcolino, 2013).

We also identified studies that focus on children’s learning processes during playtime, emphasizing when and how the relationship between playing and learning takes place in early childhood education curricula (Fleer, 2019; Inhelder et al., 1972; Lillard, 2007). Other studies emphasize, in a processual and dialogical way, how play evolves throughout child development (Oliveira, 1996; Carvalho & Pedrosa, 2002; Carvalho & Rubiano, 2004). Furthermore, there is a line of research that highlights the relationship between play and narrative, seeking to understand the acts of meaning in imaginary production and what children experience in this production (Ratner & Bruner, 1978; Bruner & Sherwood, 1976; Bruner, 1983, 1990; Kishimoto, 2007). By establishing an interconnection between play and narrativity, these studies argue that play can be considered as a depiction of children’s actions in imaginary situations (Reys, 2010; López, 2018; Montes, 2020), establishing a close relationship with the appropriation of languages in a culture.

In general, the literature review shows emphasis on the play of children over the age of three and, above all, focuses on the relationship between play and school learning. However, there is some room left for studies that demonstrate the historicity of play, that is, its genesis, transformations and, above all, its concreteness in the social practices in which children are inserted (Silva, 2021). It is essential that we delve into the argument that play is an activity that enhances subjectivities, meanings, narratives, and, therefore, human consciousness in historically and culturally situated conditions. This is the aim of the present paper.

We analyze play as a human activity (Vigostki, 2021) that drives children’s development, as a complex and dialectical process, a “path along which the social becomes the individual” (Veresov & Fleer, 2016, p. 327). Therefore, children’s experiences in social situations of development can lead to the transformation of elementary and higher psychological functions, as well as the transformation of the very context in which they live. Experiences involve contradictions and tensions in the process of human development, since “they exist in a form of drama, dramatic events, collisions, and confrontations between people” (Veresov & Fleer, 2016, p. 327).

In this sense, we argue that play is a process of permanent (re)construction of the meaning of the activity of playing by children (Silva, 2021). In other words, playing is an activity that produces meaning and, therefore, human consciousness, and is a source of human cultural development (Vigotski, 1933/2009). Play activities establish action in the social environment and the creation of meanings for what happens. Based on this assumption, our contention is that play is constituted by the unity [action/imagination] and makes it possible to create ways for children to participate in a social group through the languages in use in imaginary situations (Silva, 2021).

By treating [action/imagination] as the unit of analysis of play, we consider that this activity creates an indivisible whole between the child and the social environment. Hence, there is a web of affects that pervades the interactional sequences and languages in use, integrating the complex system of higher psychological functions, such as perception, speech, thought, memory, and imagination. In the next section, we will highlight the processes of imagination and creation in this inter-functional system of human cultural development.

Imagination and creation

The concept of imagination is based on our brain’s capacity for combination, i.e., imagination is the basis of all creative activity and manifests itself in all fields of cultural life. As Vigotski (2018, p. 16, own translation) argues, “everything around us that was created by the hand of man, the entire world of human culture, as distinct from the world of nature, all this is the product of human imagination and of creation based on this imagination”. In this sense, Pino (2006, p. 48, own translation) argues that imaginary production reaffirms the “creative capacity of human beings, acquired in the evolutionary process, which allows them to take charge of their own evolution. It is one of the pillars of the humanization process”.

An essential dimension in this process might be the relationship between the construction of new situations in the imaginary field, the development of speech, and emotions. Vigotski claims that:

The process of development of the child’s imagination, as well as other higher psychic functions, is seriously linked to the child’s speech,4 the main psychological form of his communication with those around him, that is, the fundamental form of the social collective activity of the child’s consciousness. . . . The main driver of imagination is affect. (Vigotski, 1932/1999, pp. 123-124, own translation).

In this way, imagination is a complex psychic activity, a specific human trait, intrinsically related to creative activity and interconnected with the other higher psychological functions. For Vigotski (1933/2009), imagination is a human activity affected by culture, speech, affect, and thought.

According to Cruz (2011), imagination is the ability to produce mental images and argues that, for Vigotski, the imaginary processes involved in the activity of playing demonstrate how children can experience situations that would not be possible in reality, freeing themselves from “situational bonds” (Vigotski, 2021, p. 222). When playing, children put their imagination into action, and action drives the imagination. In this activity, the child has the chance to creatively re-elaborate experienced impressions, producing imaginary realities that meet their desires (Vigotski, 2018).

We argue that play is an act of creating possibilities for participation in the social group and meanings for what happens in collective life (Silva, 2021). Such a perspective requires research approaches that grasp the historicity and the crossings between children’s [action/imagination] and the social contexts and practices in which they participate, as will be discussed in the next section.

Theoretical-methodological approach

This study is part of a research program5 that draws on an ethnographic approach to track the development of a specific group of 12 babies for a period of six years at EMEI Tupi in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. At the beginning of 2017, the first year of the study, the babies were between seven and ten months old. Throughout the first three years when the data was produced, the children were looked after full-time, between 7am and 5pm, with a group of 13 teachers and 2 assistants who were responsible for the care and education of this group. Out of the two hundred school days of each year, we observed on 42% of those days in 2017, 35% in 2018 and 45% in 2019. The data base consists of 897 hours of video recordings, photographs, and written notes.

The research team is composed of professors, and undergraduate and graduate students of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Our general objective is to understand the process of cultural development of babies in a collective context of care and education. Research members are investigating different dimensions of this process, such as imitation, play, literacy, insertion process, the issue of time and friendship relationships. These research themes are interconnected, as the production of the data originates from the same database, discussions in the research group and the interest of each researcher. However, some of the group’s researchers, due to the pandemic, were not in the field making the video recordings and field diaries. In this paper, we focus on the processes of imagination and creation in children’s play activities from 2017 to 2019, building on previous doctoral research that aimed to analyze play as acts of creation in 2017 and 2018 with the same children (Silva, 2021).

During the production of the data, four researchers were responsible for monitoring the children each year. On some days, there were two researchers together at EMEI Tupi (one was taking notes while the other was filming). Thus, it is possible for a researcher to analyze the data produced by the research group, and not just by herself. The research team held regular meetings in order to discuss the fieldwork and analyze video records that caught our attention and addressed research questions.

The production of the data, which today constitutes the research database, followed the principles of ethnography in education in dialog with historical-cultural psychology. These principles have been widely discussed (Corsaro, 1985; Green et al., 2005; Zanella et al., 2007) and will only be mentioned here. They are as follows: (i) a long, continuous, and committed stay in the field; (ii) the relationship between the parts and the whole; (iii) the relationship between the local and the global; (iv) the search for the perspective of the people being researched; (v) microgenetic analysis; (vi) abductive research logic. One may note that ethics in the research process was based on an unconditional respect for the otherness and wholeness of the babies and their teachers (Silva & Neves, 2023), considering the acceptance of the children and teachers, according to their gestures and expressions, respecting their desire/gesture/expression to participate or not in the filming.

The selected event is related to the history of play in the class in 2017 and 2018. Such history, as analyzed by Silva (2021), depicts acts of creation divided between cultural routines (circle game, birthdays, hide and seek) and collective care practices (mother-daughter, feeding, breastfeeding). In 2019, we noticed the presence of unstructured material in Rita’s teaching practice.

The event mentioned at the beginning of this paper became an anchor event (Agar, 1994, 2006), that is, an event in which the researcher who was filming the class that day was surprised and wondered about what was happening to those two girls and how that event was related to all the social practices of the group. It is worth highlighting that the video recordings were made before the pandemic. Starting from this anchor event, there was a process of immersion in the database with the aim of answering the following questions: What drove the two girls’ engagement in this game for a long period of time? How did the game unfold? What meanings did the children attribute to the box? What are the origins of these meanings? Immersion in the database encompassed five steps: i) watching the footage from the three years of field research; ii) mapping the events involving boxes and baskets in those years; iii) selecting the events; iv) transcribing the events; v) microgenetic analysis of the selected events. The microgenetic analysis sought to highlight the interactive sequences, the indicative details, the process of historical construction (Góes, 2000) as well as the semantic analysis, i.e., the meaning making process (Góes & Cruz, 2006) in this children’s activity.

“Não é uma caixa!” event

The “Não é uma caixa!” [“Not a box!”] event took place in February 2019. In that particular year, the class was composed of 16 children who were all at least 2 years of age. The classroom was large and included a blue tatami mat on the floor, a whiteboard hanging on the wall, and two tables. The teacher, Rita, and her assistant, Fabiana, were in the room with the children. In the conversation circle, Rita brought a “surprise bag” for the children to discover what was inside - paper balls. She then asked the children to make more paper balls and throw them into a cardboard box. The children and the teacher smiled and enjoyed the activity. As it was a hot day, the children were barefoot.

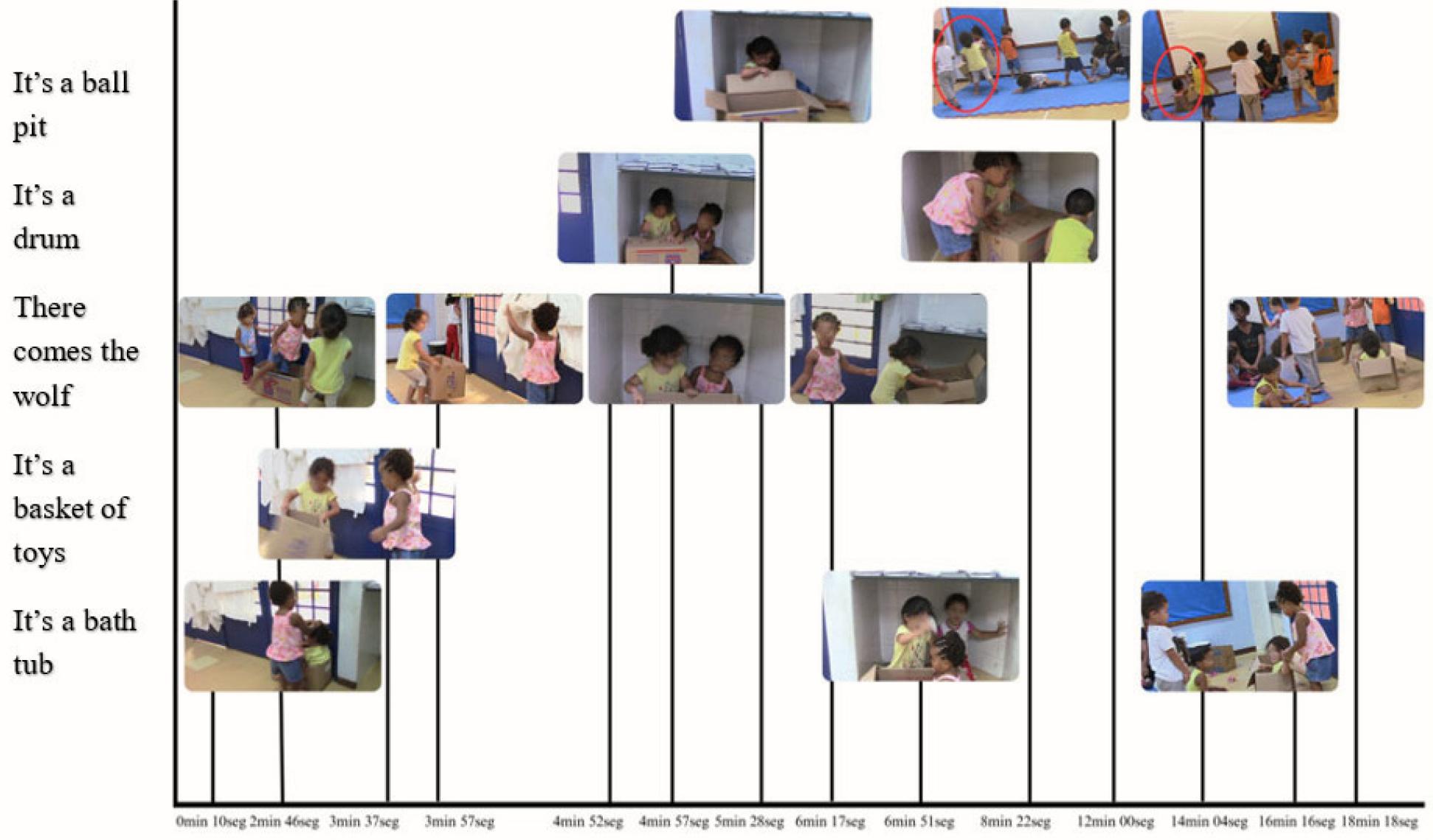

After this activity, Rita made several cardboard boxes available to the children, along with the paper balls, and played a CD of children’s songs on the stereo while the assistant took one child at a time to take a shower. Larissa, a white child aged 2 years and 8 months, and Simone, a Black child aged 2 years and 9 months, transformed the box through their actions and speech, attributing different meanings to this cultural artifact, as summarized in Figure 1.

Source: Authors' elaboration based on the research data (2019).

Figure 1 Meaning processes during play

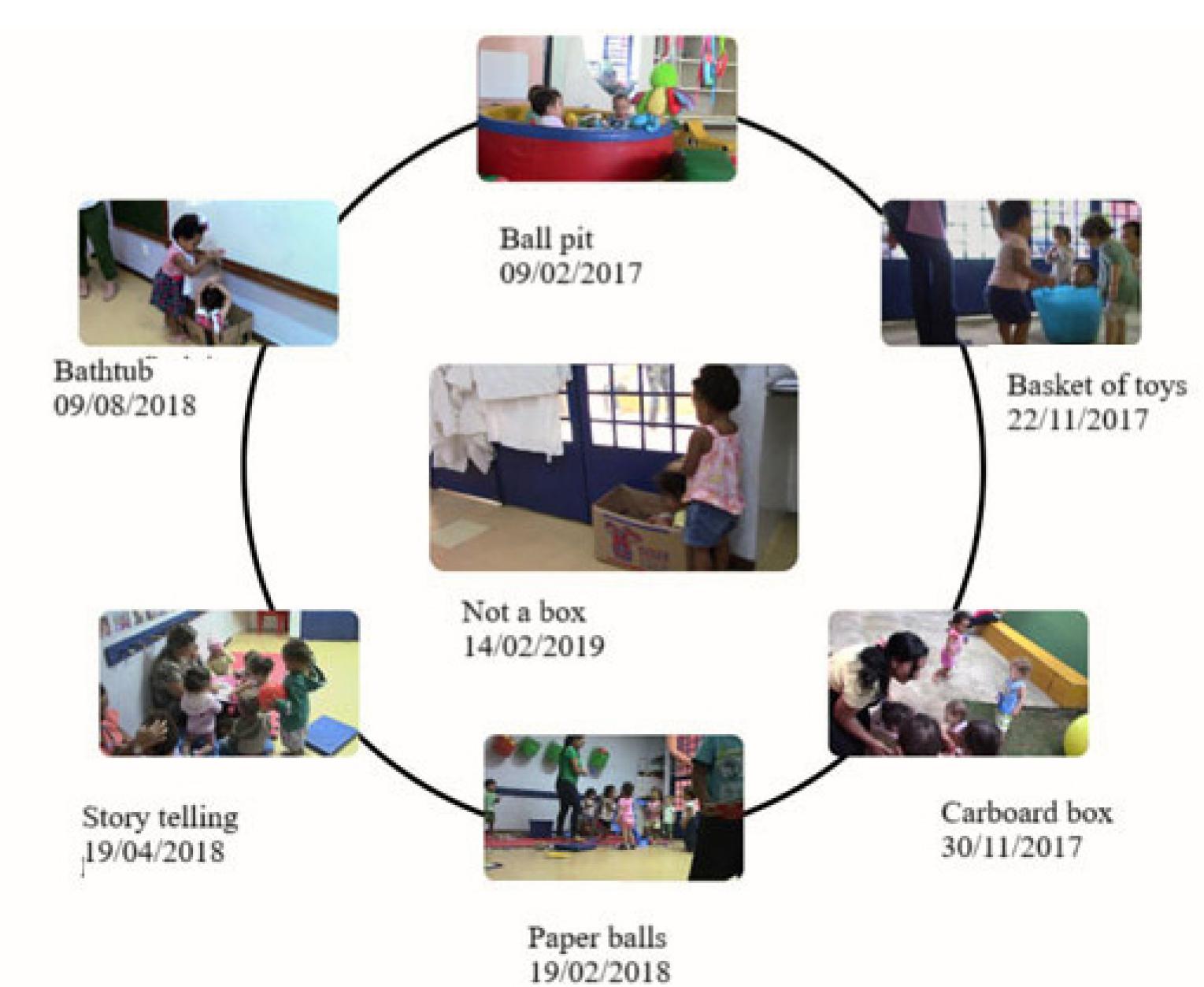

Over the course of 18 minutes, the children assigned different meanings to the box: bathtub, basket, drum, protection from the wolf, and ball pit. The transformation of this cultural artifact was possible through [action/imagination], encompassing affects, situated social cognition, languages in use, and cultures (Silva, 2021). We interpret these meanings based on the social meanings we have constructed for the children’s actions and languages, associated with the functional uses of these artifacts in the group’s social practices, since 2017. The transformation process was both supported and sustained by a narrative related to care in the mother-daughter relationship. The different meanings had been constructed over the years when these children were in the same class at EMEI Tupi, as shown in Figure 2 below. This figure locates the “Não é uma caixa!” event in the history of the class and supports our argument that play is an activity constructed in the specific historical and cultural conditions of each context.

Source: Authors' elaboration based on the research data (2019).

Figure 2 Planning of the “Não é uma caixa!” event over three years

The group’s cultural routines, which involved the use of the ball pit, paper balls, literature and avoidance routines with the wolf, the basket of toys, and collective social care practices, were experienced by the children in the class’s play activities between 2017 and 2019. These experiences are intensified by other individual cultural contents of family dynamics, such as the social roles of mother and daughter and the mother’s profession. In other words, play in collective contexts operates dialectical transitions between institutional contexts, social practices, between individual and collective imagination, between perceived action and the meanings of actions and roles, through semiotic function.

For Vigotski (2021), in the structure of play, there are rules that must be followed since, in this way, satisfaction is greater than children’s immediate impulses. The argument is based on Spinoza’s philosophy, according to which “an affect cannot be restrained or annulled except by an opposite affect that is stronger than the affect to be restrained” (as cited by Vigotski, 2021, p. 229, own translation). Additionally, it is noteworthy that play operates on a two-fold affective level. For instance, Simone cries because she is afraid of the wolf, but she happily plays with the box.

Play is the creation of an imaginary situation that emerges from the real, built with the emotions that come from these situations through a plot (Leandro, 2017), a script (Garvey, 2015), or a drama with great catharsis. The pivotal objects chosen by the children arouse emotions and support the creation of narratives that are typical of these children’s affects. As this narrative was constructed over the course of this 18-minute event, there was the possibility of experiencing affects related to the actions of mother and daughter, as they washed their hair, wrapped each other in a hug with the (imaginary) towel, protected each other from the wolf, and moved closer and further apart as they played. The synchronization of the two children shows how the narrative was being formed and how the roles of the two children were being presented.

In the following sections, we will analyze the different meanings attributed to the box, the narrative constructed, and its relationship with EMEI Tupi, a historical and cultural context built up over the years by these children and their teachers.

Not a box: It’s a bathtub!

Larissa and Simone took the box to a corner of the room. Simone was inside the box and Larissa came in saying: “It’s my bathtub”. Simone got out of the bath and said: “I’m going to wash your head”. Actions and gestures to wash her classmate’s hair began. An imaginary shower was opened with a twist of Simone’s hand on the door of the room and a ball of paper turned into shampoo when Larissa said “get here, get it for us!” and handed the ball to Simone. After 56 seconds, Larissa said “mom”, introducing the theme of the narrative that would run throughout the event. At the same time, Simone and Larissa watched Rita, their teacher, help Lúcia and Ivan share a box. Ivan tried to sit on the box where Lúcia was hiding. The teacher said: “Watch out/be careful/not to get hurt”.

The bath continued and, after wiping Larissa down with an imaginary towel, it was Simone’s turn to get into the tub and have her hair washed by her friend. After 30 seconds, Laís approached and looked at the two girls. The bath continued and Simone said “mom/towel/towel”. In this first moment, the actions, facial expressions, and speech of the two girls demonstrated that the box had become a bathtub. Moreover, it was a bathtub that supported a mother washing her daughter’s hair.

Then, the two girls smiled, put their flip-flop sandals into the box and shook it. The gesture of shaking to move something inside the box was reminiscent of the meanings of the toy baskets in the classrooms over those three years (Figure 2). It can be seen that the languages that are created and used have the ability to convey different meanings for the social actions that ensured the involvement of the two girls in the activity of playing.

Larissa’s mother explained, in an interview, that she is a hairdresser and works in a beauty salon. In 2017 and 2018, we identified that hair care, as a cultural content in Larissa’s family life, affected and drove many interactions with other children and cultural artifacts at EMEI Tupi, as well as being a content she inserted into imaginary situations. Constructing the meanings of comb, brush, shampoo and hairdryer with building blocks and empty bottles, as well as pretending to brush, wash and dry the hair of dolls, children and teachers, were some of the situations Larissa constructed through [action/imagination]. Several times, in 2018, Simone was her partner in these situations.

Over the course of those three years, it was also noticeable that Simone’s mother used various accessories in her hair, such as laces, turbans, bows and various clips. These ornaments highlighted Simone’s racial and cultural belonging in relation to the class, instigating the other children’s interests in such artifacts. In addition, we were informed that, in her family context, Simone’s older sister (aged 15) used to spend a lot of time doing her own hair.

In the institutional context, the social practices of grooming have been part of the group’s imagination since 2017, as a collective routine. In that year, there was a clothesline on the wall to store hair accessories and we video recorded moments of combing and pinning up the girls’ hair, especially in the classroom itself. In 2018, there were empty shampoo bottles in the toy baskets as well as a pink bathtub which, at various events, made up imaginary plots about bathing dolls and hygiene and beauty care in the classroom or in the solarium. There were events in which the teachers named the action of the children inside the boxes as a bathtub.

Therefore, throughout three years, there was a materiality present that supported experiences with cultural content associated with this practice. In this way, the collective imagination supports the children’s imaginary activity (Fleer & Peers, 2012), in line with the cultural experiences of the two girls’ families. There is a process of sharing social practices, such as care, cultural routines, artefacts, and relationships with adults and between the children themselves that bring out cultural contents that are perceived, experienced, and recreated in play. On the other hand, children’s experiences in other social contexts diversify and broaden the content of their play in a new collective context. In the children’s relationship with the box, for example, one may understand how the social roles of mother and daughter, the collective care routines, and the material and symbolic sources present in the room (i.e. stories with the wolf as a character) are recombined by the children’s [action/imagination]. It is this unity that creates a set of symbols for actions, a shared language, the need to communicate intentions, and a singular narrative that sustains relationships in the play activity.

Not a box, look at the wolf!

Larissa and Simone continued playing with the cardboard box. After a bath in the tub, Larissa helped Simone out of the box. Simone said “wolf/the wolf” to Larissa, looking at the glass door. Larissa and Simone carried the box across the room and returned to the same spot where they were before, next to the glass door. Simone looked out of the room again and repeated: “Look at the wolf!”, to which Larissa replied: “Let’s go/kill him/then?”. She bent down, picked up the pink flip-flop sandal from the box, and slammed it against the glass door. Simone moved away from the door, with expressions of fear of the wolf, Larissa threw the pink flip-flop sandal into the box, looked at Simone and they both smiled.

The fear of the wolf emerged in Larissa and Simone’s play, as well as the protection of the mother/Larissa in relation to her daughter/Simone, giving visibility to the affects that underpinned the whole imagination. In this sense, Vigotski (2003, p. 155, own translation) argues that “in play, in lies or in stories, the child finds an inexhaustible source of experiences and, in this way, fantasy opens new doors for our needs and aspirations to come to life”.

Sharing symbolic sources through literature is something that deserves to be highlighted here, as it represents a narrative way of organizing social experiences in which there is a plot, the agents of the action, the actions, and their outcomes. Other scholars have analyzed the relationship between narrative thinking and play (Bruner, 1990; Kishimoto, 2007), as well as between the literary plot and the origin and transformation of children’s imagination in play (Fleer, 2017). In the play with the box, we saw that the insertion of a character, the wolf, present in the stories told by the teachers in 2017 and 2018, in the materiality of the literature books and singing games (such as the singing game “let’s go for a walk in the woods, while the big bad wolf doesn’t come”) creates a symbolic field of defense and persecution of the wolf already present in the collective imagination of the group. Therefore, play is not about the perception of isolated characteristics, but a way of generalizing the meaning of the actions that produce meaning to the artifact (Vigotski, 1933/2009).

At this point, the box was used as a basket to store the “kill the wolf” tool, which changed the girls’ perception, leading them to shake the box, and transforming the meaning of the bathtub-box into a basket-box. Thus, the [action/imagination] creates a form of relationship with the box formed by its meaning and characteristics. The [action/imagination] is supported both by the meanings attributed and by the materiality of the artifact itself: it wouldn’t be possible to keep the flip-flop sandal and the balls if they were playing with something else, i.e., a building block. The concreteness of the artifact being played with is also important, as is the social significance of the box as a storage medium. The children’s [action/imagination] brings about drama between the perceived material properties of the box, the social meanings and the shared narratives, establishing a dramatic act of meaning-making. It is this action in the symbolic field that makes it possible to create a narrative of the mother caring for her daughter (the mother who bathes her, washes her hair, and protects her from the wolf) that reconfigures the girls’ relationships with the artifact itself as a symbol in a cultural group, with the context of the play and with the people present.

Not a box, it’s a basket!

As they shook the box containing the paper balls and flip-flop sandals, Simone and Larissa made a similar movement as if they were shaking the baskets of toys that were present in the classroom throughout 2017 and 2018. The look on the two children’s faces as they rocked the basket together shows their enthusiasm for the movement and the sound the objects made when they were moved around in the box. The movement is also reminiscent of the experiences with the nursery teachers who, throughout 2017, placed the children in these baskets and swung them around.

In the classroom, in 2018, there were four green baskets with toys that were placed on the wall and which, after being emptied daily, the children used as trolleys. By acting with the box as if it were a basket for storing things, moving it around the room, and swinging it from side to side, the two girls broadened the meaning of the artifact itself, creating other forms of relationship with this artifact and with the social context at that moment. Box and basket have close social meanings (storing things) and, with the action of swinging, imagination and memory recreated events in which children entered the basket and were swung by the teachers.

Vigotski (1933/2009) considered creation, through the activity of playing, as one of the forms of transition from perceptual thinking to ideational thinking, that is, a form of thinking through the ideas and constructed meanings about objects, which, in this case, is possible through [action/imagination]. Such an assumption might lead us to note that creative activity, in other words, imagination, constitutes children’s cultural development in play by enabling them to master their actions and intentions. In this case, it’s not just perception, but [action/imagination] that guides the activity of producing meaning, mental images, and social symbols that represent objects.

Not a box: Look at the wolf, Mom!

After the play, Simone pointed at the glass door again, telling Larissa that the wolf was still outside. Larissa picked up the pink flip-flop sandal and repeated the action of knocking on the glass door in order to scare the wolf away, asking “what’s/up/darling?”, and dragging the box towards Simone. Simone called out to Larissa (“mom/mom”) and walked to the other side of the room, taking a seat under a shelf. Larissa walked towards her and also sat down under the shelf.

At this point, Larissa and Simone took up again the “mother and daughter” narrative, intertwining it with the fear of the wolf outside the room. Through the [action/imagination] that there is a wolf present in the imagined narrative, the children established a field of protective meanings through the box under the shelf. The location of the box in front of the body leads to an association with the meaning of protection and also an approach and avoidance cultural routine (Corsaro, 2009) that we have seen established at other events throughout 2018. Through the use of a little house, a room in the cupboard, baskets, mats, and the table in the classroom, or even by moving their bodies away in catch-up play routines (Silva, 2021), the children shared various routines, with the teachers and among themselves, to escape from the wolf, played by other children.

We argue that, through [action/imagination], children recover experiences and re-elaborate them in other contexts and with other artefacts, in a process of recombination and new acts of signification. Therefore, the activity of playing integrates other cultural functions such as memory, thought, perception, speech, and imagination into a functional system. The activity of playing guides the process of signification and symbolic production and, therefore, the development of human consciousness and subjectivity.

Not a box, it’s a drum!

Larissa and Simone turned the box upside down, causing the flip-flop sandals and paper balls to fall out. The two girls hit the bottom of the box, turning it into a drum. At this point in the event, the gesture of beating the drum with one’s hands and producing sounds is representative of the meanings of the drum built up in collective practices over time. Since 2017, the teachers have used different media to produce sounds and accompany songs and other cultural routines, including the toy drum itself (Figure 2). In the event, there was an appropriation of the meaning of hitting a surface with both palms as the production of sound and music in the group and, at the same time, meanings for each other’s actions with that artifact. The turning of the box and the gesture of tapping on its bottom made it possible to continue the imaginary situation in other semantic fields - like the drum that produces sound.

The two girls’ gestures and mimetic expressions are symbolic actions that represent and explain something to someone, specific to humans (Vigotski, 2021). Gesture, as a semiotic medium, is the foundation of our human capacity to share intentions, address each other as interaction partners, and build intersubjectivities (Fichtner, 2010). In the “Não é uma caixa!” event, it becomes apparent that the girls’ mimetic expressions were constructed by a concrete situation and were also interpreted by them in order to be incorporated, through imitation, into the situation that is being transformed by the acts of produce meaning that made common action possible. In other words, when playing with a cultural artifact (the box), the children’s gestures and expressions have sign structures, since they have the box as a symbolic referent, but integrate each other’s actions in an act of collaboration and reciprocity.

Children’s [actions/imagination] make it possible to create meaning and dialogic interactive fields (Rossetti-Ferreira et al. 2004), in which Larissa and Simone’s actions were shared and interdependent. In other words, meanings are renegotiated and redefined dialogically, for example, when one begins to hit the box with her hands after the other. The dialogical interactive field thus reorganizes each other’s actions and the entire system of psychological functions, since the [action/imagination] opens up other possibilities for the box, now re-signified as a drum. At the same time, the game of producing drum sounds makes it possible to maintain and transform the group’s cultural routines, such as a musical band, which has brought about sound materiality since 2017 (Figure 2), demonstrating, through [action/imagination], a memory that is built over time.

Not a box, it’s a ball pit, it’s a bathtub! What about the wolf?

Continuing the play activity, Larissa said to Simone: “Look/at/the/pit/of/polka/dots/that/mommy/gave/you!”, to which Simone replied: “The/big/bad/wolf!”. Larissa pushed the box forward, throwing the objects out again. As soon as all the objects had fallen, Larissa asked Simone: “Pick them up/with me!”. Simone helped her pick up the objects and put them back into the box. Larissa dragged the box back under the shelf. Simone accompanied Larissa repeating “The/wolf/the/big/bad/wolf!”. Two other children, Maria (2y 10m) and Carlos (2y 8m), approached. Maria put two flip-flops inside the cardboard box and, together with Larissa, climbed into the box. Simone rubbed their heads. The three children grinned.

After getting out of the box, Larissa helped Simone into the bathtub, who said: “Now/I’m/going/to/take/a/bath”. Larissa took a small paper ball and tapped Simone on the head twice. Simone pointed across the room and said: “The/wolf!”. Maria continued to watch Larissa and Simone sitting under the shelf. Larissa said to Simone: “Let’s/get out/of/the/bathroom!”, to which Simone repeated: “The/wolf/mom!”. Larissa, Simone, and Maria carried the box, walked around the room, and returned to under the shelf. Maria picked up some paper balls from the floor and put them in the box.

At this point, Larissa introduced the meaning of the box as a ball pit, a gift from a mother to her daughter. After Maria’s action and speech, the girls took back the box as a bathtub, but also as protection from the wolf. It is noticeable that the “mother and daughter” narrative sustains the play activity of the two girls.

As the play continued, Larissa repeated: “Ball/pit!” Simone and Larissa went into the ball-pit box. Maria said “I/want/to/go/into/the/bathroom!”, but got no response from the other children. Larissa and Simone looked up and Larissa said “it’s raining!”, to which Simone echoed “it’s raining”. They put both hands on their heads, seeming to protect themselves from the rain.

The continuity of the event shows that Larissa and Simone’s actions of pushing the box, and knocking over the objects inside, as well as Maria’s action of putting paper balls inside the box, produced meanings of a ball pit. However, Maria didn’t seem to share the meaning of the ball pit and took up the semantic field related to the bathroom.

The ball pit, an artifact present in 2017, had a fundamental story in the constitution of experiences in the curriculum of this group (Cortezzi et al., 2020). Thus, the memory of these experiences in the ball pit made it possible for Larissa and Simone to propose this play.

Not a box: The wolf is back!

At the end of the event, Larissa and Simone continued playing with the box. Larissa turned the box over again, letting all the objects fall to the floor. Henrique approached and then Larissa said: “It’s the wolf!”. Henrique continued to stare at her. Larissa carried the box to the other side of the room, sat down inside the box, and called out to Simone, who was dancing to the music put on by the teacher Rita. Simone returned to her colleague and, seeing Carlos, pointed at him saying “That’s the wolf!”. Carlos made movements with his hands, simulating grabbing Simone. The stereo played the Brazilian nursery rhyme “Carneirinho, carneirão” [Big, little sheep] and Simone started dancing again. Larissa got out of the box and, with Henrique (2y 10m) and Carlos, jumped in with Simone.

The [action/imagination], in this cultural routine established by Simone and Larissa in relation to Carlos and Henrique, to whom they assigned the role of the wolf, establishes the dialectic between child and environment, languages, and cultures. The cultural context of the classroom, with its corners, artifacts, sounds (doll, box, people, music), and the affects that amplify or reduce the capacity to act (Spinoza, 1677/2017, p. 177) are imbricated in the actions and languages that make the cultural content of play visible. We consider the movements of coming together and moving away as a cultural routine, since being together collectively in a context of care and education made it possible to share symbolic sources (especially children’s songs and literature) about fear and danger that constituted the affects to act as if they were avoiding something.

The presence of wolf stories and popular folklore jokes involving the avoidance-approach routines of animals, such as the wolf, during the years 2017 and 2018, establishes the collective imagination that enabled the creation of imaginary situations materialized in actions such as approaching and moving away. Thus, one may note the dimension in this routine related to a process of building a common understanding of the gestures of moving away and moving closer, such as the body position that moves away and the gaze that summons, which act as semiotic mediators and support the actions of other children.

Therefore, cultural routines in a group that shares the collective context of care and education are re-signified in play in a process of permanence and appropriation. In our research with babies and children up to three years old, we observed that the structural dimensions, such as contextualization, embellishment, and the framing of material elements (Corsaro, 2011), although relevant to maintaining the imaginary situation, do not by themselves sustain the dialogic interactive field. [Action/imagination] is the unit of analysis of cultural development in the group, since they create syntheses between social structures, cultures, languages that express meanings of distance and closeness, and artifacts that amplify other cultural contents of routines, social and family practices. In other words, play may reorganize the affects in the narrative. The feelings of fear and distance from the wolf, for example, are tensioned by the care and protection of the mother, the idea of going home, as well as the strategies of hitting the wolf with the gesture of using the flip-flop sandal forcefully on the surface.

Approximations and distancing in the construction of play

In this section, we will analyze an important dimension of this event that has not yet been explored. Throughout 20 minutes of play, there were moments when Simone distanced herself from Larissa. This distancing happened for various reasons. At first, when she heard a child in the class crying, Simone ran under a shelf and called out to Larissa, “mom/mom”, to which Larissa promptly responded by bringing her daughter a “ball pit”. Listening to the songs put on by Rita, Simone moved away from Larissa again to dance. From inside the box, Larissa called out to her colleague: “Si/mo/ne, Si/mo/ne/come/here!”. Larissa wobbled on the box, throwing her body backwards and losing her balance. Simone rushed over to help Larissa and then went back to dancing. A minute later, Simone approached Larissa again, and together, they pointed out Carlos and Henrique as the wolf. Then the two girls, along with Henrique and Carlos, jumped around the room to the sound of the songs. Simone found a black doll in one of the boxes and cradled it, looking for the box she and Larissa were playing with. Simone gently placed the doll inside the box, which would then become a cradle. However, the teacher, Rita, called the class out to the playground.

It is noticeable that the movements of distance and closeness between the two girls did not prevent the imaginary situation from continuing. On the contrary, the distancing led Larissa and Simone to build a rapprochement. Simone called Larissa her mother, which led her to bring her daughter a present. Larissa called Simone and her colleague rushed to help her, maintaining the narrative of caring for each other. In a third approach movement, the two children named their classmates as the wolf, supporting the narrative of protection from danger.

We argue that the sharing of meanings created by the [action/imagination] in playing with the box was made possible by the languages in use in social practices that establish a dialogic interactive field. The narrative, as a way of sharing the meanings of experiences, helped to support the actions of the two girls and their participation in the event.

Finally, we argue that imagination is part of the psychological functional system and, as an activity that allows us to create meanings, it leads children’s cultural development, since it establishes the unity of affect-languages (narratives) and cultural practices, and creates semiosis, forms of human communication and fields of dialogic interaction that make social relationships possible.

Some final remarks

Fantasy and reality are two nuances of human possibility, in which we find the experiences that constitute us as subjects. By means of [action/imagination], Larissa and Simone gave new meanings to the cardboard box: i) bathtub (as part of the educational institution’s routine and the family context); ii) basket (or the baskets in which the toys were kept in the classroom); iii) drum (always present in the songs and musical activities in the class); iv) ball pit (constituting the experiences in the nursery curriculum in 2017). A narrative of care and protection was produced through these meanings.

Our contention is that the “Não é uma caixa!” event was sustained by the history of the group over the three years they were together. The meanings attributed to the box and the narrative produced are rooted in processes of creation for what happened in collective life, intertwined with the individual and affective dimensions of the children. What drove the children to act in the imaginary field was the cultural content that affected them and, at the same time, the relationships and partnerships established over the time they spent together in the group. That is why this event lasted 20 minutes, even with the distancing movements between the two girls. In other words, it was possible for the two children to get closer again in a process supported by the cultural routines of the class over three years together.

It is noteworthy that the processes of creating languages communicate intentions and sustain imaginary situations, as well as narrative creation intertwined with acts of care. The meanings attributed to the box are summarized in the narrative of protection, care, and social relations between mother and daughter. The centrality of care in children’s play has already been observed in other works (Silva, 2021), which indicates that play is an activity for creating dialogical human relationships, searching for the other, and producing actions delimited by the position, role and understanding of this other. In this way, it is not simply an exploration of the physical and material world, but a cultural and symbolic production mediated semiotically by the collective imagination.

It is essential to analyze the transformation of the meanings of a cultural artifact by children and how this evokes narratives that circulate about boxes, mother-daughter roles, and care practices. At the same time, such transformations trigger an understanding of the relationship between play and narrative. Transforming the meaning of the box requires a cultural framing of symbolic action through language (Bruner, 2008). At the event, we observed how the children needed to situate themselves and each other in the symbolic field of actions using speech and other gestural and expressive languages to invite, name, insist, introduce the narrative content of the action, and assign a role. In this sense, play is the act and drama of entering cultures; a narrative activity that turns children’s experiences into an instrument for producing meanings and giving them historicity (Bruner, 2008). With each transformation of the cultural artifact, there were specific forms of communication, orientation, and action expected from the other. The narrative allowed the children to manage the imaginary situation in the play activity, making it possible for other people to interpret what was happening there. Playing with the box reveals how very young children appropriate the contents of the social practices in which they participate, forming narratives and ways of referring to their actions, understanding the actions and intentions of others on the basis of social referents, and adjusting their desires and actions to those of other people.

The concept of experience (Perezhivanie) helps understanding the importance of the subjective relationship between the child and the social environment, giving visibility to the particular circumstances and models of education. The group’s collective cultural routines, such as the use of the ball pit, drums and boxes, as well as the care routines at the EMEI, such as bathing, constitute cultural content for which the children seek to construct meanings in play.

In this event, there is a synthesis in the act of playing between previous experiences and the concrete situation established with the artifacts and people present in contexts of play. This ratifies the notion of the theoretical and methodological unit of analysis of the activity of playing that we have argued as being the [action/imagination]. Thus, the analysis of the event “Não é uma caixa!” shows us children’s imaginary situations, with the languages in use and the meanings attributed to the cardboard box, in a social situation of development.

If play is a way of entering into social meanings, as other scholars argue (Bruner, 2008), the play of children aged 0 to 3 sheds light on the meaning of ethics in human relationships, on actions between people as well as on the effects of these actions, as our research in collective care and education contexts has shown (Silva, 2021; Cortezzi, 2020; Oliveira, 2018). This has ethical, political, aesthetic, and pedagogical implications for the organization of social development environments based on an ethic of care that makes it possible to expand the experiences of care that children have in family environments. This expansion of cultural content in a collective context implies building, maintaining, and redesigning play contexts (space, time, artifacts, transitions, and relationships) that make it possible to share material and symbolic sources over time. It also implies the position of the adults in the group as organizers of these contexts and, at the same time, as attentive observers and active interlocutors who support the imaginary activity, offering materials and symbolic resources.

What we analyze in the “Não é uma caixa!” event are the possibilities of [action/imagination] of children in a social situation of development. All the transformations described, i.e., bathtub, basket, drum, ball pit, and protection from the wolf, are meanings attributed by the children - Larissa and Simone.

We conclude that play is the foundation for children’s social interactions, dialogic fields, and reciprocity that constitute intersubjectivity and the newness of each person in the world. Play is the place where lies the unexpected, the unforeseen, and, therefore, the possibility of opening up diverse social experiences into singular experiences. The contradictions that children deal with in the imaginary situation, including the syntheses between the histories of their social groups, their families and their own, tip the balance towards our defense of the right of all children to share collective contexts of care, education, and social practices with others, against any attempt to close off and designate the space where childhood is produced.

REFERENCES

Agar, M. (1994). Language shock: Understanding the culture of conversation. William Morrow. [ Links ]

Agar, M. (2006). An ethnography by any other name. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-7.4.177 [ Links ]

Borba, A. (2009). Quando as crianças brincam de ser adultos: Vir-a-ser ou experiência da infância? In J. J. M. Lopes, & M. B. Mello (Orgs.), O jeito de que nós crianças pensamos sobre certas coisas: Dialogando com lógicas infantis (pp. 97-117). Rovelle. [ Links ]

Bragagnolo, R. I., Rivero, A. S., & Wagner, Z. T. (2013, 29 setembro-2 outubro). Entre meninos e meninas, lobos, carrinhos e bonecas: A brincadeira em um contexto da educação infantil. 36ª Reunião Anual da Anped, Goiânia, GO, Brasil. https://www.anped.org.br/biblioteca/item/entre-meninos-e-meninas-lobos-carrinhos-e-bonecas-brincadeira-em-um-contexto-da [ Links ]

Brougère, G. (2010). Brinquedo e cultura (Coleção Questões da Nossa Época, 43) (G. Wajskop, Rev. & Trad.). Cortez. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (1983). El habla del niño: Cognición y desarrollo humano. Paidós. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (2008). Actos de significado (V. Prazeres, Trad.). Edições 70. [ Links ]

Bruner, J., & Sherwood, V. (1976). Early rule structure: The case of peekaboo. In J. Bruner, J. A. Jolly, & K. Sylva (Orgs.), Play: Its role in evolution and development. Penguin. [ Links ]

Carvalho, A. M. A., & Pedrosa, M. I. (2002). Cultura no grupo de brinquedo. Estudos de Psicologia, 7(1), 181-188. [ Links ]

Carvalho, A. M. A., & Rubiano, M. R. (2004). Vínculo e compartilhamento na brincadeira de crianças. In M. C. Rossetti-Ferreira, K. de S. Amorim, A. P. Silva, & A. M. A. Carvalho (Orgs.), Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano (pp. 208-233). Artmed. [ Links ]

Corsaro, W. A. (1985). Friendship and peer culture in the early years. Ablex. [ Links ]

Corsaro, W. A. (2003). We’re friends, right? Inside kids’ cultures. Joseph Henry Press. [ Links ]

Corsaro, W. A. (2009). Reprodução interpretativa e cultura de pares. In F. Müller, & A. M. A. Carvalho (Orgs.), Teoria e prática na pesquisa com crianças: Diálogos com William Corsaro (pp. 31-50). Cortez. [ Links ]

Corsaro, W. A. (2011). Sociologia da infância (L. G. R. Reis, Trad.). Artmed. [ Links ]

Cortezzi, L. P. (2020). As vivências no currículo do berçário: As possibilidades de autonomia e proteção entre bolinhas e almofadas [Dissertação de mestrado não publicada]. Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. [ Links ]

Cortezzi, L. P., Neves, V. F. A., & Sales, S. R. (2020). “Quem quer brincar na piscina de bolinhas?”: Vivenciando o currículo com bebês na Educação Infantil. In C. B. Michel, G. M. Nogueira, & S. da R. V. Gonçalves (Orgs.), Práticas educativas em espaços escolares e não escolares: Compartilhando experiências (pp. 5-52, 1a ed., vol. 1). Appris. [ Links ]

Cruz, M. N. (2011). Imaginação, linguagem e elaboração de conhecimento na perspectiva da psicologia histórico-cultural de Vigotski. In A. L. B. Smolka, & A. L. H. Nogueira (Orgs.), Emoção, memória e imaginação: A constituição do desenvolvimento humano na história e na cultura (pp. 85-103) (Série Desenvolvimento Humano e Práticas Culturais). Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

Fichtner, B. (2010). O surgimento do novo no gesto das crianças: Um diálogo impossível entre Benjamim e Vigotski. Poíesis Pedagógica, 8(2), 18-32. [ Links ]

Fleer, M. (2017). Play in the early years. Monash University. [ Links ]

Fleer, M. (2019). Conceptual playworlds as a pedagogical intervention: Supporting the learning and development of the preschool child in playbased setting. Obutchénie: Revista de Didática e Psicologia Pedagógica, 3(3), 1-22. [ Links ]

Fleer, M., & Peers, C. (2012). Beyond cognitivisation: Creating collectively constructed imaginary situations for supporting learning and development. Australian Educational Research, 39(4), 414-430. [ Links ]

Garvey, C. (2015). A brincadeira: A criança em desenvolvimento (Coleção Clássicos do Jogo). Vozes. [ Links ]

Góes, M. C. R. (2000). A abordagem microgenética na matriz histórico-cultural: Uma perspectiva para o estudo da constituição da subjetividade. Cadernos Cedes, 20(50), 9-25. [ Links ]

Góes, M. C. R., & Cruz, M. N. (2006). Sentido, significado e conceito: Notas sobre a contribuição de Lev Vigotski. Pro-Posições, 17(50), 31-45. [ Links ]

Green, J. L., Dixon, C. N., & Zaharlick, A. (2005). A etnografia como uma lógica de investigação. Educação em Revista, (42), 13-79. http://educa.fcc.org.br/pdf/edur/n42/n42a02.pdf [ Links ]

Inhelder, B., Lézine, I., Sinclair, H. Y., & Stambak, M. (1972). Les debuts de la function symbolique. Archives de Psychologie, 41(163), 187-243. [ Links ]

Kishimoto, T. (2007). Brincadeiras e narrativas infantis: Contribuições de J. Bruner para a pedagogia da infância. In J. Oliveira-Formosinho, T. Kishimoto, & M. A. Pinazza (Orgs.), Pedagogia(s) da infância: Dialogando com o passado, construindo o futuro (pp. 249-275). Artmed. [ Links ]

Leandro, F. C. de B. (2017, 1-5 outubro). O jogo protagonizado infantil como um ato artístico em sala de aula uma abordagem vigotskiana. 38ª Reunião Anual da Anped, São Luís, MA, Brasil. http://anais.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/arquivos/trabalho_38anped_2017_GT07_351.pdf [ Links ]

Lillard, A. S. (2007). Pretend play in toddlers. In C. A. Brownell, & C. B. Kopp (Eds.), Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations (pp. 149-176). The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

López, M. E. (2018). Um mundo aberto: Cultura e primeira infância (C. Oliveira, Trad.) Selo Emília. [ Links ]

Marcolino, S. (2013). A mediação pedagógica na educação infantil para o desenvolvimento da brincadeira de papéis sociais [Tese de doutorado, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”]. Repositório Institucional Unesp. https://repositorio.unesp.br/handle/11449/106628 [ Links ]

Marcolino, S., & Mello, S. A. (2015). Temas das brincadeiras de papéis na educação infantil. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 35(2), 457-472. [ Links ]

Montes, G. (2020). Buscar indícios, construir sentidos (C. Oliveira, Trad.). Selo Emília; Solisluna. [ Links ]

Oliveira, V. S. (2018). O processo de inserção de bebês em uma escola municipal de educação infantil de Belo Horizonte [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais]. Repositório Institucional da UFMG. https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/31840 [ Links ]

Oliveira, Z. de M. R. de. (1996). A brincadeira e o desenvolvimento infantil: Implicações para a educação em creches e pré-escolas. Motrivivência, (9). https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/motrivivencia/article/view/5663 [ Links ]

Pino, A. (2006). A produção imaginária e a formação do sentido estético: Reflexões úteis para uma educação humana. Pro-Posições, 17(50), 47-69. [ Links ]

Portis, A. (2006). Não é uma caixa (C. E. Machado, Trad.). Cosac Naify. [ Links ]

Prestes, Z. R. (2010). Quando não é quase a mesma coisa: Traduções de Lev Semionovitch Vigotski no Brasil - Repercussões no campo educacional [Tese de doutorado, Universidade de Brasília]. Repositório Institucional da UnB. https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/9123 [ Links ]

Ratner, N., & Bruner, J. (1978). Games, social exchange and the acquisition of language. Journal of Child Language, 5(3), 391-401. [ Links ]

Reys, Y. (2010). A casa imaginária: Leitura e literatura na primeira infância. Global Editora. [ Links ]

Rivero, A. S., & Rocha, E. A. C. (2017, 1-5 outubro). O brincar e a constituição das crianças em um contexto de educação infantil. 38ª Reunião Anual da Anped, São Luís, MA, Brasil. http://anais.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/arquivos/trabalho_38anped_2017_GT07_1024.pdf [ Links ]

Rossetti-Ferreira, M. C., Amorim, K. de S., Silva, A. P. S. de, & Carvalho, A. M. A. (Orgs.). (2004). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. Artmed. [ Links ]

Sarmento, M. J. (2005). Crianças, educação, culturas e cidadania ativa: Refletindo em torno de uma proposta de trabalho. Perspectiva, 23(1), 17-40. [ Links ]

Silva, E. de B. T. (2021). Atos de criação: As origens culturais da brincadeira dos bebês [Tese de doutorado, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais]. Repositório Institucional da UFMG. https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/35500 [ Links ]

Silva, E. de B. T., & Neves, V. F. A. (2023). A construção de uma lógica na pesquisa com bebês. Revista Diálogo Educacional, 23(76), 93-122. https://doi.org/10.7213/1981-416x.23.076.ds04 [ Links ]

Spinoza, B. (2017). Ética (T. Tadeu, Trad.). Autêntica. (Obra original publicada em 1677). [ Links ]

Teixeira, S. R. S. (2013). A relação cultura e subjetividade nas brincadeiras de faz de conta de crianças ribeirinhas da Amazônia. 36ª Reunião Anual da Anped, Goiânia, GO, Brasil. https://www.anped.org.br/biblioteca/item/relacao-cultura-e-subjetividade-nas-brincadeiras-de-faz-de-conta-de-criancas [ Links ]

Veresov, N., & Fleer, M. (2016). Perezhivanie as a theoretical concept for researching young children’s development. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 23(4), 325-335. [ Links ]

Vigotski, L. S. (1999). O desenvolvimento psicológico na infância (C. Berliner, Trad.). Martins Fontes. (Obra original publicada em 1932). [ Links ]

Vigotski, L. S. (2003). Psicologia pedagógica. Artmed. [ Links ]

Vigotski, L. S. (2009). Imaginação e criação na infância: Ensaio psicológico (Z. Prestes, Trad.). Ática. (Obra original publicada em 1933). [ Links ]

Vigotski, L. S. (2018). Imaginação e criação na infância (Z. Prestes, & E. Tunes, Trads.). Expressão Popular. [ Links ]

Vigotski, L. S. (2021). A brincadeira e o seu papel no desenvolvimento psíquico da criança. In L. S. Vigotski, Psicologia, educação e desenvolvimento: Escritos de L. S. Vigotski (Z. Prestes, & E. Tunes, Orgs. & Trads.) (pp. 209-239). Expressão Popular. [ Links ]

Zanella, A. V., Reis, A. C, Titon, A. P., Urnau, L. C., & Dassoler, T. R. (2007). Questões de método em textos de Vygotski: Contribuições à pesquisa em psicologia. Psicologia e Sociologia, 19(2), 25-33. [ Links ]

Data availability statement

The data from the research text is available in the article for readers, as well as in the research database under the responsibility of the research group coordination.

1 The age of children is indicated by “y” (years) and “m” (months) relative to the date of the event.

3 The book Não é uma caixa (Portis, 2006) draws on the possibilities of playing with an artifact present in various cultures: the cardboard box. The narrative is pervaded by a number of imaginative possibilities for readers, as the box turns into a car, a house, and a rocket, among others.

4 We agree with Prestes (2010) that, in this case, the best translation of the Russian term retch is speech, not language.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to EMEI Tupi, its directors, coordinators, teachers, children and families. We would also like to thank groups Estudos em Cultura, Educação e Infância [Studies in Culture, Education and Childhood] - EnlaCEI (https://enlacei.com.br) - and Grupo de Estudos e Pesquisa em Psicologia Histórico-Cultural na Sala de Aula [Group of Studies and Research in Historical-Cultural Psychology in the Classroom] - GEPSA (https://gepsa.com.br). Finally, we would like to thank Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico [National Council for Scientific and Technological Development] (CNPq) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais [Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation] (FAPEMIG) for their financial support.

Received: November 29, 2022; Accepted: August 09, 2023

texto en

texto en