Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.53 São Paulo 2023 Epub 10-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980531410014

TEACHER EDUCATION AND TEACHING

VOICES IN THE TEACHER IDENTITY OF EXPERIENCED EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

IUniversidad Diego Portales, Facultad de Educación (UDP), Santiago, Chile;

IIUniversidad Católica Silva Henríquez (UCSH), Santiago, Chile;

The present study seeks to identify and understand the voices of four experienced Chilean early childhood educators who are in dealing with critical incidents in their professional experience. Semi-structured interviews of narrative orientation, focused interviews and biograms were applied, on which a thematic analysis was conducted using tools of the dialogical self-theory. The critical incidents collected are temporally located in the first stage of their professional trajectory and show ruptures in the caregiving function, provoking emotions of frustration, guilt and anger. Identity tensions between the detected voices are identified in the stories, showing the transition from an educator in training to a professional educator.

Key words: IDENTITY; TEACHING; EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION; LEARNING

La presente busca identificar y comprender las voces con las que se posicionan cuatro educadoras de párvulos chilenas experimentadas al abordar incidentes críticos en su experiencia profesional. Se aplicaron entrevistas semiestructuradas de orientación narrativa, entrevistas focalizadas y biogramas, sobre las que se realizó un análisis temático utilizando herramientas de la teoría del self dialógico. Los incidentes críticos recopilados se ubican temporalmente en la primera etapa de su trayectoria profesional y muestran rupturas en la función de cuidado, provocando emociones de frustración, culpa e ira. En los relatos se identifican tensiones identitarias entre las voces detectadas, dando cuenta de la transición entre una educadora en formación a una educadora profesional.

Palabras-clave: IDENTIDAD; ENSEÑANZA; EDUCACIÓN INFANTIL; APRENDIZAJE

Este artigo busca identificar e compreender as vozes com que se posicionam quatro experientes educadoras chilenas de escolas infantis ao abordar incidentes críticos em sua experiência profissional. Foram feitas entrevistas semiestruturadas de orientação narrativa, entrevistas focadas e biogramas, que serviram de base para uma análise temática utilizando ferramentas da teoria do self dialógico. Os incidentes críticos coletados situam-se temporalmente na primeira etapa de sua trajetória profissional e mostram rupturas na função do cuidado, provocando emoções de frustração, culpa e raiva. As histórias identificam tensões de identidade entre as vozes detectadas, mostrando a transição de uma educadora em formação para uma educadora profissional.

Palavras-Chave: IDENTIDADE; DOCÊNCIA; EDUCAÇÃO INFANTIL; APRENDIZAGEM

Cet article cherche à identifier et à comprendre les voix et le positionnement de quatre éducatrices chiliennes de garderie face à des incidents critiques vécus lors de leur expérience professionnelle. Des entretiens semi-structurés de type narratif, des entretiens ciblés et des biogrammes ont été réalisés et analysés thématiquement à l’aide d’outils issus de la théorie du soi dialogique. Les incidents critiques retenus se situent chronologiquement dans la première phase de leur parcours professionnel et font état de ruptures d’attention, provoquant des émotions de frustration, de culpabilité et de colère. Dans les récits ressortent des tensions identitaires qui signalent le passage d’éducatrice en formation à celui d’éducatrice professionnelle.

Key words: IDENTITÉ; ENSEIGNEMENT; ÉDUCATION DE LA PETITE ENFANCE; APPRENTISSAGE

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY OF TEACHERS IS A COMPLEX PROCESS that is under debate since it articulates objective and subjective elements in its construction. On the one hand, it incorporates the objectivity of a predefined set of competencies and tasks from the academic world and aspects of the world of work, in its initial teacher education and implementation. On the other hand, it considers the lived experience and subjectivities, with their emotional and practical dimension. These spheres, according to Dubar (2000), operate as an articulation between the biographical and the structural dimensions, giving rise to a construction of professional identity as a dialectic established within the socialization processes in which the individual and the institutional framework are framed. This dialectic has been understood by Gohier et al. (2001) from two processes that contribute to the construction of teacher identity: identification with the characteristics of teaching in their training and identization understood as a process of individualization and distinction from others.

Internationally, research indicates that professional identity in early childhood education is a controversial and problematic issue (Moloney, 2010). Mainly because it involves delving into the discourses and policies that are promoted in professional practice (Scherr & Johnson, 2017), as well as the subjectivities and experiences of educators and how they construct their teaching identity (Robinson et al., 2018). In this sense, the early childhood educator has fluctuated between the role of caregiver, culturally associated with a welfare practice, and a professional role associated with the pedagogical aspect (Guevara, 2019; Pardo, 2019; Scherr & Johnson, 2017; Vergara, 2014). This transition has occurred in a context of strengthening this educational level in Chile through new curricular bases (Chilean Ministry of Education [Mineduc], 2018), new teacher professional development policies, a framework for good teaching and the creation of a superintendence of education (Mineduc, 2019).

The above in a scenario in which enrollment at the level has expanded (Arteaga et al., 2018), but the quality of the educational processes that occur in the classroom has been questioned (Tornero et al., 2015; Treviño et al., 2013), with shortcomings observed to strengthen educational inclusion (López et al., 2021; Rubilar & Guzmán, 2021) and difficulties in interaction in based-play activities (Grau et al., 2019). This is added to a series of deprofessionalizing perceptions, such as poor working conditions (Arteaga et al., 2018), ambivalent professional recognition (Figueroa-Céspedes et al., 2022a) and a continuous transaction and dispute regarding early schooling (Pardo & Opazo, 2019).

This is reflected in the construction of teachers’ imaginaries that separate personal life from work performance, idealizing their role as a “happy educator”, always willing and cheerful (Muñoz-Zamora et al., 2022) or showing a sacrificial teaching identity that prescribes that a good early childhood educator must delay herself to rescue and care for the children, giving rise to a performative teaching profile (Poblete, 2018), which moves away from a pedagogical and transformative role.

Also, educators face daily a context that limits their pedagogical agency (Moloney et al., 2019; Scherr & Johnson, 2017), while at the same time, they are required to professionalize (Pardo, 2019). Therefore, it is relevant to train teachers capable of constructing relevant pedagogical knowledge that integrates experiential knowledge elaborated in their practice (Alliaud, 2017) and that endows them with greater pedagogical agency (Scherr & Johnson, 2017). This necessarily implies addressing the predominance of everyday discourse, based solely on their subjectivity (Badía & Becerril, 2016) or common sense (Pessoa et al., 2017), to move to pedagogical practices. That allows them to actively position themselves in the face of learning, transcending conceptions that limit the development of the hidden potential of children accessing early childhood education (Fernandes & Tonatto-Zibetti, 2022).

From a sociocultural approach, a person’s voice is considered to be a set of utterances elaborated by an individual and reflecting the subjective awareness of the speaking personality (Bakhtin, 2010), expressing a particular way of representing reality oriented to their actions in a social situation (Wertsch 1993). Thus, teacher identity is constructed dynamically and in a narrative context, by different experiences internalized as voices that dialogue with each other, in harmony or opposition, accounting for the appropriation or resistance of institutional discourses that emerge from public policy or common sense (Wertsch, 1993). For Monereo and Pozo (2014) identity acts as a filter of the information that reaches the mind, affecting the interpretation that each person has of reality and mobilizing different types of actions to address everyday problems.

Thus, the act of consciousness involved in reflecting on the voices that form the identity of early childhood educators implies knowing the subjective meanings of the professional world and its particularities in being a teacher (Hermans, 2001). What we seek to highlight here is the borderline nature of identity, implying the threshold between at least two worldviews, one’s own and that of others (Bakhtin, 1982), and the possibility of resolving these issues, at least partially, through the understanding of teachers’ narratives.

Thus, it is relevant to access the ways that early childhood educators have reasoning and position themselves in the face of certain pedagogical phenomena, particularly those that disturb their traditional habitus, such as critical incidents (Nail et al., 2012). Critical incidents are unexpected situations, difficult to oversee, that reveal the underlying beliefs and motives of the teacher (Joshi, 2018), configuring a kind of symptom that allows understanding of the teacher’s needs (Valdés & Monereo, 2012), an essential aspect for the construction of a strategic teaching identity (Monereo & Badía, 2011). The above implies, following Dubar (2000), addressing those transactions between what is prescribed by institutions and the daily reality experienced by the professional. Accessing ways of thinking implies the possibility of knowing how educators position themselves in the face of the demands of everyday life, establishing negotiations between their identification and identity processes (Gohier et al., 2001). The above is associated with the need to explore the processes of identity construction of early childhood educators in Chile (Poblete, 2018; Robinson et al., 2018), in a context in which there is still little research on experienced teachers considering their professional and labour trajectory (Figueroa-Céspedes et al., 2022a; 2022b; Figueroa-Céspedes & Guerra, 2023).

Thus, this article seeks to answer the following research questions:

With what voices does a group of Chilean and experienced female early childhood educators position themselves in the face of critical incidents in their work trajectory?

How are these voices articulated in the educators’ narratives?

Early childhood education in Chile

Early childhood education in Chile is a consolidated educational level and has legal recognition and a specialized institutional framework (Mineduc, 2019), and is governed by principles and guidelines framed in a national curriculum specific to the level (Mineduc, 2016). The objective of this educational level is to provide, in conjunction with the family, quality learning through various agencies and institutions, complementing family education (Mineduc, 2017). In this sense, a timely and relevant intervention by the teaching staff is essential to enhance child development, providing affective bonds and enriching experiences (Mineduc, 2017).

Early childhood education in Chile is organized into three distinct levels with specific sublevels (Mineduc, 2016). The first level is the Sala Cuna, divided into Sala Cuna Menor (85 days to one year old) and Sala Cuna Mayor (1 to 2 years). The second level is the Middle Level, which is subdivided into Minor Middle (2 to 3 years) and Major Middle (3 to 4 years). The third level is the Transition Level, which ranges from 4 to 6 years of age and is divided into the First Transition Level (4 years) and Second Transition Level (5 to 6 years). In addition, there is the possibility of forming heterogeneous groups, where children from different levels are grouped, either in the nursery or in the middle and transition levels (Mineduc, 2016). Since 2013, the Second Transition Level is mandatory to enter primary education (Mineduc, 2017).

In kindergarten education, educators have a 4 or 5 year-university degree and work in classroom teams with other educators, generally with technical level studies, and focus on curricular activities that can be conducted both in the classroom and outdoors, using play as a learning strategy (Mineduc, 2018). The didactic material and the playful role of tangible resources are fundamental for the learning process of children, encouraging exploration and experience of the world.

Professional identity in early childhood education

Following Arndt et al. (2018) the professional identities of early childhood teachers are shaped, influenced and (re)shaped by theories, systems and political agendas. The above implies that the lived experience of gender, pay and recognition, quality assurance, student success, and nation-state construction are linked to teacher identity construction (Arndt et al., 2018).

In the research by Fairchild and Mikuska (2021), it is realized that emotional labour and professionalism are aspects of tension when generating improvements in the pedagogical work in early childhood education. Emotional work in early childhood education is defined by Davis and Degotardi (2015) as those expectations that teachers have in building relationships based on affection with young children and how these bonds are articulated in their professional identities.

According to Pinzón (2016), women have been traditionally related to the role of caregiver, so their identity would be involved in all those situations that require a domestic, “private” space, where teaching is associated with motherhood. In this sense, Dalli (2002) showed in her study that early childhood educators in New Zealand conceived their occupation as a complement to the maternal role. According to her point of view, the knowledge base maintains a socially diffuse distinction with maternal knowledge, i.e., that which mothers rely on to care for their children. Thus, under a humanistic tradition, professionalism in early childhood education is a field under construction, with pedagogy being the backbone of its knowledge base (Dalli, 2008).

In this sense, for Davis and Degotardi (2015) care is understood as a multidimensional construct inextricably linked to the practices of early childhood educators, being linked to the dominant discourses in which this practice is situated. Her research accounts for the influence of political ideology (as evidenced in curricular documents, for example) on the way care in early childhood education is perceived and put into practice. Another element that contributes to this understanding is the ethics of care, which operates based on social responsibility, in the sense of achieving the well-being of people by making moral decisions that have consequences for the future of the following generations (Gilligan, 1985). This is relevant in early childhood education, where the labour force is predominantly female (99.9%, according to the Subsecretaría Educación Parvularia, 2021), replicating a social construction that exclusively associates women to care work due to a gender bias widely present in societies such as the Chilean one.

In the research conducted in Chile by Poblete (2018), it is observed that the vocation of female educators turns teaching work into a transcendent occupation, where there is a generalized self-perception of having the necessary skills to “save” and “rescue” children, based on education, care and personal sacrifice. Thus, the vocational discourse legitimizes the exploitation of professionals, to the point of risking their lives, turning them into martyrs. This kind of experience is identified by Fairchild and Mikuska (2021) as a “cruel optimism” since vocation is manifested in a context in which teaching work is neither valued nor adequately rewarded. This leads educators to perceive an ambivalent recognition of the role of early childhood education and, in particular, of their work (Figueroa-Céspedes et al., 2022a). This correlates with low salaries and a lack of optimal conditions for teaching performance in early childhood education (Arteaga et al., 2018).

In this sense, the neoliberal discourse emphasizes competition and individualism in teaching, which is highly contradictory to the priorities of early childhood education, where close bonds and activism in favour of children are prioritized (Kamenarac, 2019; Osgood, 2006). Thus, how educators reconcile the demand of the policy and account, at the same time, for overcoming the contextual conditions that affect their performance, becomes an object of interest for the educational improvement of the level. In this process emerges what Kelchtermans and Vanassche (2017) understand as micropolitical literacy, an essential skill that allows teachers to “read” situations in terms of competing interests, positions and goals in the educational institution. This skill, according to the authors, is not only limited to the local, as it is also connected to more global issues, such as power structures, discursive hegemonies, and social injustices that impact educational opportunities for children.

Professional identity and the dialogical self-theory

The construction of the professional teaching identity operates in contact with otherness, in a dialogic experience. As Monereo and Pozo (2014) point out, identity has its origin in interactions with others giving account of an interpretation of a transcendent self-entity in space and time that articulates the self and its contexts of production. Thus, the sociocultural and situated proposal of learning argues that this construction is produced by the interaction between people in the same social context or communities of practice where they develop as future professionals (Wenger, 2010). Thus, in the socialization processes, experiences, historicity and situations of otherness are articulated in discursive, contextualized and learning environments (Navarrete-Cazales, 2015).

A central concept introduced by Bakhtin is the notion of voice (Bakhtin, 2010; Wertsch, 1993). Bakhtin emphasized that words are neither neutral nor unitary in their meaning and metaphorically pointed out that words have a “particular flavor”, being the “hallmark” of a profession, a genre, or a person. Therefore, when an utterance is strongly intoned, it can be said to be produced by a certain voice (Akkerman & Van Eijck, 2013; Bakhtin, 2010). A voice can be defined as a speaking personality, which presents a particular perspective on the world as, for example, a positive or critical voice, but also a formal or maternal voice (Bakhtin, 2010). Thus, the representation of ideas in the mind is not shaped by only one voice, but by a plurality of voices that dialogue with each other and originate in the social sphere, in processes of sustained communicative exchanges (Wertsch, 1993).

The dialogic view of identity understands it as discontinuous and multiple, co-constructed in interaction with others and the world, from a process of elaboration of meanings. Linking the concepts of self and dialogue, Hermans’ (2014) theory of the “dialogical self” combines concepts that, traditionally, have been associated with the internal space of the individual mind with the external through relationships with others. The theory is presented as a theory of the “self”, but it addresses the notion of identity directly, with “self” referring to the self as “knower”, and “identity” to that which is known, the self.

It is at this point that dialogical self-theory (Hermans, 2001, 2014) extends Bakhtin’s theories to describe how the self can be understood as a dialogical self, composed of multiple I-positions in the micro-society of the human mind. The concept of I-positions links Bakhtin’s notion of voice to a person’s identity. Each I-position is driven by its own intentions, expressing a speaking personality with its specific point of view and historicity (Akkerman & Van Eijck, 2013). In this way, the movements of the different positions allow the construction of a personal voice, facilitating the dialogue and, therefore, its possibility of transformation, through processes of positioning, counter-positioning and re-positioning (Monereo & Hermans, 2023). Thus, interactions between voices do not necessarily reveal coherence but may denote contradictions, tensions and coalitions between them (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011; Hermans, 2001; Monereo & Hermans, 2023).

According to Salgado and Hermans (2005), dialogical self-theory understands that multiplicity does not necessarily deny the existence of a unitary self and that I-positions involve a reflexive process in which other perspectives are considered. For Akkerman and Van Eijck (2013) dialogical self-theory combines modern and postmodern views on identity, as it more fully captures the concept of identity in borderline contexts, such as those raised in this research by connecting the boundary of the personal and professional world.

Critical incidents

A critical incident (CI) is understood as an unexpected event that is produced by a surprising and challenging situation (Del Mastro & Monereo, 2014) where the professional and interpersonal competencies of the subjects are questioned by requiring effective and innovative responses (Nail et al., 2012). Critical incidents challenge and put those who experience them in crisis, destabilizing their own professional identity (Monereo, 2019).

Critical incidents configure a kind of symptom that allows understanding of teaching needs from the active reflection of such phenomena (Valdés et al., 2012). Following Adams and Rodríguez (2020), taking an experience as a critical incident implies making a value judgment about what we do, implying the attribution of meaning to that event.

For Joshi (2018), CIs reveal the teacher’s underlying beliefs and motives, reflecting professional dilemmas (Nail et al., 2012) and identity tensions (Pillen et al., 2012). Thus, according to Sisson (2016), CIs contribute to shaping professional identity and agency, allowing learning from these experiences to provide increasingly relevant and strategic responses.

Thus, when faced with situations described as critical incidents, the subject is in a position to elaborate and assume his/her strategic self (Monereo & Badía, 2011), transforming his/her teaching identity by rearticulating the internalized voices of experience, seeking the most relevant positions to address the challenges posed (Hermans, 2014; Monereo, 2019).

Methodology

The present study adopts a qualitative approach of descriptive-interpretative scope since its guideline is to understand the voices with which experienced early childhood educators position themselves in the face of episodes identified as critical incidents. This research is part of a broader doctoral research of a biographical-narrative nature (Riessman, 2008), since it explores the construction of the professional identity of teachers based on the approach of the memories and stories of early childhood educators.

Participants

The participants were selected through purposive sampling based on specific criteria (Flick, 2015), which include: having a degree as an early childhood educator, being an experienced educator (work experience of more than five years) and currently working in educational institutions.

These are 4 educators, between 31 and 43 years of age, with more than 8 years of work experience each, and who work in Chile. The educators work in kindergartens (3) and elementary schools (1). In terms of continuing education, two educators have specialized courses in specific pedagogies - Montessori and Waldorf -, one has a diploma and the remaining one has only taken short courses (Table 1).

Table 1 Characterization of the participants

| Age | Studies | Area | Modality | Type of Dependency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Francia | 30 | Diploma | Center | School | Private |

| Ivana | 42 | Waldorf | Center | Kindergarten | Private |

| María | 43 | Montessori | Center | Kindergarten | Private |

| Romina | 31 | Courses | South Center | Kindergarten | Public |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Information production tools

As an instrument for the production of information, a semi-structured interview of narrative orientation was first used, with a flexible and dynamic script that allows addressing the different stages of their life trajectory (Sarceda, 2017). Subsequently, focused interviews were conducted in which the educators identified relevant situations, qualified as biographical traces (Piani, 2019), which refer to those marks or traces that remain in the life of a person from their experiences and narratives. These narratives are condensed into a biogram to facilitate the organization of the information. The biogram is a delimited and co-constructed life story that collects “the spaces and times that, from the current perspective of the interviewee, have been shaping his life, with the current assessment of each of them” (Susinos & Parrilla, 2008, p. 159), to delve into the description of each event. From these accounts of biographical traces, those transforming experiences that the participants identified as critical incidents are rescued. The interviews were conducted remotely through the Zoom platform, in two sessions of one hour each.

Information analysis

The analysis was conducted in two stages, first a thematic analysis was conducted following the guidelines of Riessman (2008), considering the principles of the dialogical selftheory of Hermans (2014) and the methodological guidelines of Lara et al. (2020), Monereo (2019) and Santamaría et al. (2013). In this way, the aprioristic categories elaborated by Lara et al. (2020) are used: Problem-Situation (act), the Relational domain, Tension, Emotions, Thoughts/Beliefs, Voices and Agency (see Table 2).

Table 2 Adapted analytical categories

| N. | Dimensions | Guiding questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Problem-Situation (Act) | What is the problem/situation that affects you? |

| 2 | Relational | What is your position in front of? |

| 3 | Tension | What is causing you tension in this problem/situation? |

| 4 | Emotions | What emotions are involved? |

| 5 | Thinking-Belief | What do you think about the problem/situation? Why do you think this situation does not correspond to the standard of the teaching profession? |

| 6 | Voices | What voices are present in her narrative? What do these voices say? |

| 7 | Agency (awareness-raising actions) | How did you approach the problem/situation? How do you detect and become aware of it? |

Source: Lara et al. (2020).

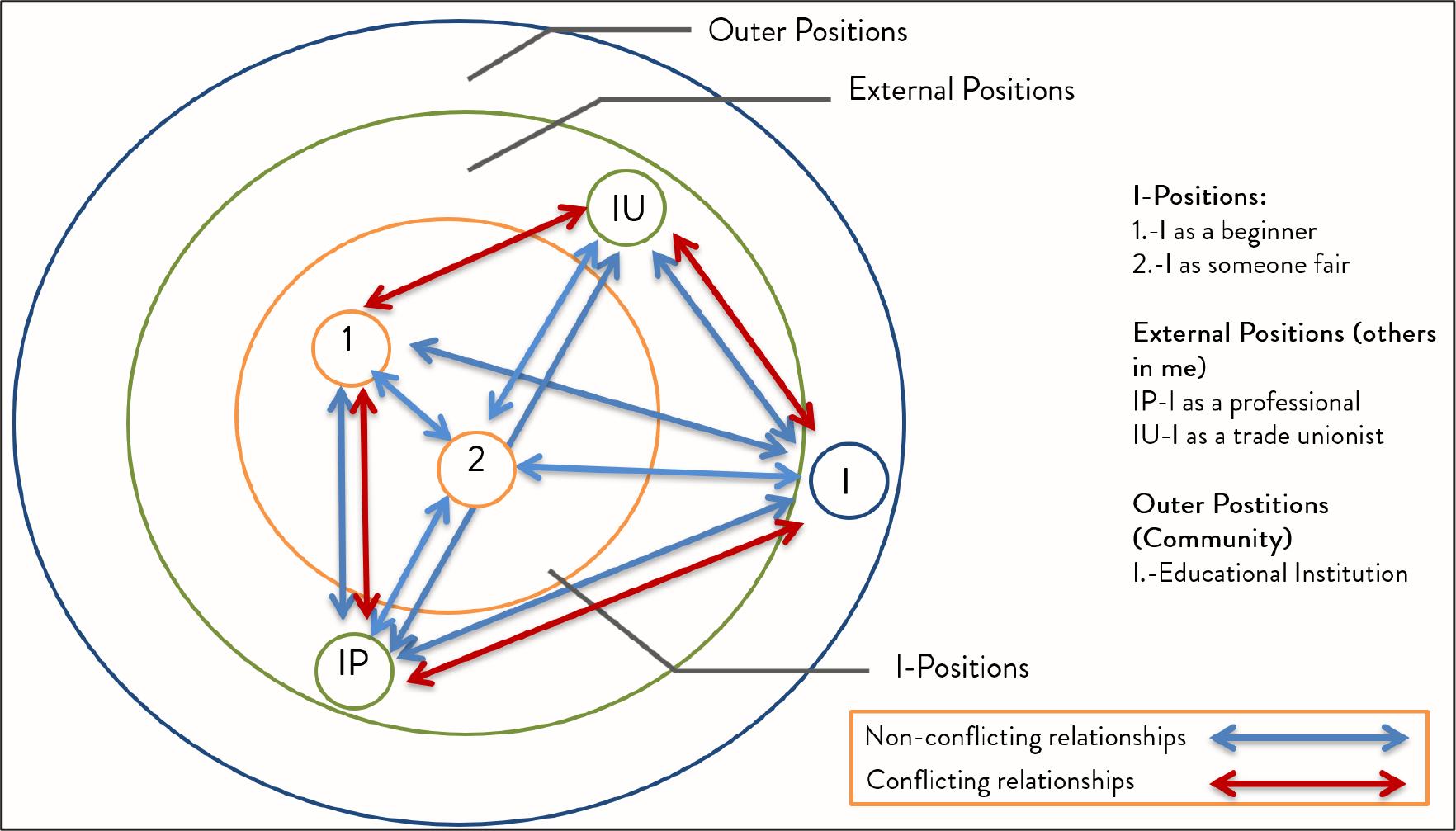

In the second stage of the analysis, relationships between dimensions were elaborated, identifying the positions of the self about other subjects, beliefs, emotions and voices that sustain them. The reading of the incidents allowed the identification of predominant and latent tensions in the narrative (Pillen et al., 2012). Finally, based on the response to the biogram question (What did you learn from this event about your teaching role and identity?), the positions that the educators occupied during the process were identified. Hermans’ (2014) categories are recognized in this analysis: internal positions (I - positions), external (voices of significant others in the story itself), and external or institutional (other voices in me), as well as the quality of the relationships between them, that is, whether they present tensions or conflicts between them or not. These voices constitute means or cultural tools that the (main) agent - the educator - has used to act. Finally, to graph the interaction between voices, the repertoire of personal positions is used (Hermans, 2001; Monereo, 2019).

Subsequently, the themes transversal to the cases are selected, evaluating the relevance of each code and category, guaranteeing the conceptual soundness of the themes raised. The qualitative data software Atlas Ti. 8 © is used for the analysis process.

Ethical aspects

The study follows the ethical guidelines of Noreña et al. (2012) focused on negotiation, collaboration, confidentiality and anonymity, equity, impartiality and commitment to knowledge. In addition, the principles of respect for the personal autonomy of the interviewees and the principle of justice are incorporated, given that it is fundamental for this study to develop attentive and unprejudiced listening in the interviews and for the interviewees to validate the information obtained (Fernández, 2012). It is worth mentioning that all participants were informed of the objectives of the research, signing a consent form previously validated by the ethics committee of the university.

Results

The following is the analysis of the critical incidents detected by the educators that constitute biographical traces in the construction of their professional identity (Figueroa-Céspedes & Guerra, 2023; Piani, 2019). Each one identifies a critical incident in her professional trajectory, understood as a complicated moment, difficult to manage. These incidents are temporally located in the first years of their professional trajectory (see Table 3).

Table 3 Critical incidents reported

| Educator | Critical incident | Brief description | Professional stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Francia | In the middle of the sea with Lucas | A second transition level child (5 to 6 years old) does not want to enter the classroom, France tries to calm him down and the child hits her and leaves her bleeding. | Second year of professional trajectory |

| Ivana | The bottle of bleach | A child of lower transition level (4 to 5 years old) takes a sip of bleach, which a person from the cleaning team left forgotten in the room. Ivana was supposed to take over at that level, as the educator in charge was not available. | First year of exercise |

| María | First disappointing professional experience | Shouting argument with the director of the kindergarten where she worked. The reason was the lack of minimum conditions for the functioning of the kindergarten. | First year in exercise |

| Romina | Conflicts of newcomer | Discussion with the director of the kindergarten, in the context of Romina’s entry to the institution and the dynamics created by the director and kindergarten education assistants. | Third year of professional exercise |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

In general terms, in the four situations analyzed, a rupture in the care system is observed in which the physical and/or psychological integrity of members of the educational community is put on risk, especially that of children and educators. The main domain of the situation is linked to the area of labour relations and how the educational institution provides a safe environment, and how the educators position themselves in the face of this requirement.

A cleaning person left a bottle of bleach, and a child drank a little bit. This was in a private kindergarten in Providencia. There were many children and few staff, so we had to make adjustments to cover that level and the risk is that this type of situation happens. (Ivana).

These situations lead educators to experience emotions of frustration and guilt, as they are unable to control contingencies or act promptly, as well as anger in the face of situations that are seen as unfair.

The frustration of not having the tools to be able to help the child prevails in me. I felt alone in the world, abandoned, without support in the case. (Francia).

I felt anger because I saw people being mistreated. (Maria).

In all cases, the educators position themselves against the institutional framework, be it the kindergarten or the school, or the figure of the school’s management. In this case, it is relevant to mention that the four situations occurred in the early stages of the professional life of the four participating educators, either in the first experience at work (Ivana and María) or in the second work experience (Romina and Francia). The above gives rise to tension between the identity of an educator in training and a professional educator.

Because I felt that things were not as I expected them to be, as if what I wanted to do did not work out, or because they were not interested either, that is, it is not that I did not want to do things, but that they did not have, they did not have the material resources, so I got frustrated because I had ideas that I could not carry out. (María).

The above implies that one of the main voices in these narratives is that of a beginner educator, inexperienced and still in the process of learning the keys involved in the relationship with work. In addition, the notion of a righteous self emerges, which implies a critique of the institution oriented by the principle of care and welfare of children, establishing limits in social interaction. The professional, external voice appears, a trace of their university learning and of what they have experienced in practical teaching situations, showing the need to act in a pedagogical sense. The trade union voice also emerges, which operates as an identification with the problems experienced by education workers, from a perspective of claiming labour rights. In addition, there is the external institutional position, which is represented by the vision of the kindergarten or school as a space for education and care, marked by an emphasis on safeguarding rights (see Table 4).

Tabla 4 Detected voices in the critical incidents

| Detected Voices | Position | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| I as a beginner | Internal | It was my first experience . . . (María) The frustration of not having the tools to be able to help Lucas prevails in me. . . . (Francia) |

| I as someone fair | Internal | . . . if they had no materials, we have nothing to do (María) It got to a point where it was uncomfortable to even see the people with whom this situation was happening (Romina) |

| I as a professional | External | . . . it allows me to realize certain rules to follow (Ivana) . . . to specialize in certain tools that one could acquire and that could help me (Francia) |

| I as a trade unionist | External | If we would unite... if no one would accept to be paid like this.... (María) This situation led me to learn not to accept being blamed for things you are not responsible for (Ivana) |

| Educational Institution | Outer | There were many children and few staff. We had to make adjustments to cover the group. (Ivana) …Maybe I expected the principal, being the principal, had to come and talk to me... (Romina) |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Going deeper into the polyphonic relationship of the voices present in the narration of the critical incidents, the internal voice of I as a beginner connects with insecurities and lack of knowledge in the situations experienced. This situation shows a self that is permeable to the inferiorization signals transferred by the environment, in this case, represented by the role of the institutionality.

Maybe I put up with many things because I said no, as I am an educator, I can’t, I don’t know, respond badly, for example, or say that this is like this or that, so... or I got very tangled up in words, not wanting to hurt the other person. (Romina).

On the other hand, the internal position of the I as someone fair articulates the needs of children with their own experiences of establishing limits in interactions, when observing situations that affect their sense of fairness. This approach based on social justice generates emotions of discomfort when the purposes of early childhood education are not achieved.

I was left with the feeling that I had not been able to help him, I was left with that feeling. (Francia).

I felt hopelessness, I thought that these bad practices and mistreatment were a generality in the kindergartens. (María).

In this way, the professional voice emerges from the externality, positioning itself through the recognition of those constitutive elements of the ethos of the early childhood educator, from an agential, responsible and active perspective. This position is in alliance with the institutional external voice, in charge of ensuring the correct functioning of the educational unit and, simultaneously, in opposition to abusive and mistreating behaviours towards the educators.

This experience was important for me since it allowed me to become aware of certain rules to follow, regardless of whether I am in charge or not .... I also learned the responsibilities of each position. (Ivana).

I learned to strengthen myself, to feel confident in the person I am, in what I know, in what I can do, and to take a stand from there and not let them take me away, I think that was the main thing. (María).

In this confrontation of positions, emerges, in coalition with the I as a professional, the voice of I as a trade unionist, marked by experiences before the university (for example, experiences of political socialization).

At that time when I was leaving, I said: -But how can we accept something like this, to be paid in this way? If we were united... nobody would accept to be paid like that, but that is complex, and I believe that the educator is one of the unions that has never been very united. (María).

. . . they had the same look of my father as a union leader, as well as social, they helped people, but basically, they accompanied their colleagues a lot. (Ivana).

This narrative construction shows a struggle for recognition on the part of women educators, which is a transversal aspect of the experiences reported. Thus, the coalition between the professional and union voices is associated with the position of the head as the visible face of the institutionality (Ivana, Romina and Marcela) or with colleagues from the special needs team (Francia). In all four cases, this relationship with the institutional framework generates dilemmas since the educators understand the professional purpose of the practice of care but establish work limits in situations of mistreatment or abandonment by their hierarchical superior or other colleagues. Francia, for example, experiences resignation due to a lack of collaboration in the face of a situation of risk. This reveals a decrease in her agency, in contrast to her professional self, being left without the capacity to solve or confront the challenging scenario posed by a child who presented behaviors that put the classroom community at risk.

I wanted that, at that moment, as I did for me, at that moment, there was a psychologist, social worker, special educator, neurologist and everything, to be able to help him. (Francia).

Finally, the outer position visualizes institutionalism as an organization that safeguards rights and is oriented to develop pedagogical and care processes in early childhood. The narratives as this institutional voice are coordinated with the voice I as someone fair, which is associated with the otherness of childhood, considering it as a stage of life that requires adequate environments and, therefore, of efforts to protect its integrity and right to education.

The first experience was when I entered a room where there were no materials for the children, there were only a few, there were children who were biting, and of course, if they had no materials, there was nothing to do. (María).

They had an organization that they had decided on, and I, of course, came to change the issue of planning, to see the issue of downtime, and how to renew procedures that were not being conducted as they should be... It was nothing beyond what was requested, but, of course, inside there the rumours were getting bigger and bigger, and that was what we later clarified with the director. It was nothing more than what was requested, but, of course, the rumours were growing a little more and that was what we later clarified with the director. (Romina).

By way of summary, the Personal position repertoire (Figure 1) shows coalition relationships between the I as a beginner and I as someone fair, within the framework of a perspective focused on justice, care and access to education for children. The union voice is allied with the I as someone fair (internal) and I as a professional (external) positions, while it opposes the I as a beginner position due to the perception of insecurity and personal procrastination assumed at the beginning of the professional career, in contrast to the progressive adoption of a notion of justice and human value that incorporates them as valid agents in its discourse. At the same time, the outer institutional position is simultaneously in conflict and coalition with the I as a trade unionist and the I as a professional positions, showing an alliance with the principles of care for children, but demanding recognition and valuation as workers.

Discussion and conclusions

In the four critical incidents identified by the educators, situations are collected in the context of entry into the labour field in which the educators show a still fragile identity, permeable to the inferiorization signals transferred by the environment, in this case, represented by the voices of the institutionality, director or support teams. In this sense, from the analysis developed from the Dialogical Self-theory (Hermans, 2014) we manage to configure various positions of the self that are found in a given work context and interact with each other (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011).

The voices of I as a beginner and I as someone fair, place a focus on the personal dimension, which is balanced with I as a professional and I as a trade unionist positions, predominantly used by the educators to understand the incidents reported. These voices manifest themselves as structuring, since they organize the other positions, seeking to keep the self-integrated and oriented to active agency. According to the analysis conducted, the professional voice would contribute to establishing dialogic counterpoints in the pedagogical practice, by facilitating the construction of strategies with an adequate level of agency and from a formative perspective, giving rise to identification processes with those constitutive elements of the ethos of early childhood education. In this sense, articulation is observed between identification processes with the professional role and identification processes in terms of the particular experience of each educator (Gohier et al., 2001). The above shows that the subjectivities and life worlds of the educators, associated with experiences in their family or community contexts, make them deploy positions that account for an ethic of care (Gilligan, 1985) and social justice (Kamenarac, 2019).

The incidents analyzed are associated with a rupture in the care system where the physical and/or psychological integrity of members of the educational community, especially children and educators, is put on risk. The ethics of care (Gilligan, 1985) provides a valuable framework for comprehending the development of the professional voice. This framework encompasses a social responsibility that prioritizes the well-being of children and their communities, reflecting the interests of future generations. It advocates for embracing differences and practicing benevolence as foundational elements of social connections and ethical judgment. This expectation is aligned with the conceptualization of the role as advocate activists (Kamenarac, 2019) revealed by educators in their narratives, from the desire to preserve good conditions for learning and development of childhoods. In this narrative process, educators reflect on their subjective experiences, assuming their responsibility as teachers (Moloney et al., 2019; Scherr & Johnson, 2017), at the same time, they exercise a position of resistance to the oppression they face in their institutions (Sisson, 2016).

The main domain of the situation is linked to the field of labour relations and how the educational institution is arranged to provide a safe environment, and how educators position themselves in the face of this requirement. From this place emerges the union voice, with a political and vindicative vision (Kamenarac, 2019; Osgood, 2006), based on the principle of nonviolence (Gilligan, 1985). The potential of the union voice as a tool to overcome the notion of abnegation and sacrifice as a vocational source is rescued, moving towards an approach of recognition and labour justice of the work of female educators (Poblete, 2018). Following Monereo and Hermans (2023), this voice assumes a “We-Position” by representing a collective position expressed in a choral voice used by the educators.

The critical incidents analyzed constitute biographical traces in the educators’ trajectory (Figueroa-Céspedes & Guerra, 2023; Piani, 2019), evidencing how they address a sense of helplessness in the face of collective pressure norms (internalized and represented by the other involved in the dispute), especially when considering the well-being of children (Melasalmi & Husu, 2018). Indeed, the emotions experienced are associated with frustration and guilt, giving rise to identity tensions (Pillen et al., 2012) linked to the transition between undergraduate students and education professionals, with a rupture of the idealized vision of being a teacher. In addition, a frustrated expectation is observed around the educational institution as a space of care and human development, in contrast to what they observe in these incidents. These tensions allow us to reflect on the conditions of teaching work (Arteaga et al., 2018), and the adoption of a sacrificial (Poblete, 2018), maternal (Dalli, 2008), and happy (Muñoz-Zamora et al., 2022) identity, and the experience of cruel optimism (Fairchild and Mikuska, 2021) as representations of work at the early childhood education level. From the analysis of the educators’ accounts, it is considered necessary to address the first work experiences from a formative perspective, given that they result in relevant moments in the construction of the teaching identity of early childhood educators (Robinson et al., 2018).

Thus, the institutional level emerged, and the educators established a position. This situation reflects the struggle for recognition faced by educators as a transversal element of their identity construction (Figueroa-Céspedes et al., 2022a; Poblete, 2018), retrospectively understanding the professional purpose of the practice of care and establishing, in parallel, labour limits in the face of mistreatment or abandonment by their hierarchical superior or the rest of the team. In this sense, the need arises to address micropolitical literacy processes (Kelchtermans & Vanassche, 2017; Silva-Peña et al., 2019) that allow educators to understand power dynamics and their relationship with institutional life from a practical perspective.

According to what has been reviewed, the analysis of the voices that participate in the construction of identity allows for identifying challenges for the initial training and continuous professional development of early childhood educators, while orienting new ways of conducting such processes (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011). For example, a relevant aspect to consider is the low connection with academic voices such as influential authors and teachers, observed in the present study. This issue can be linked to the preponderance of discourses based on personal experience (Badia & Becerril, 2016; Lara et al., 2020) or common sense (Pessoa et al., 2017). This is related to the findings of Alliaud (2002, 2017) regarding the limitations of teacher training to re-signify the knowledge constructed in school biography and the relevance of integrating experience and formalized knowledge in the construction of pedagogical knowledge.

Thus, the analysis conducted from the dialogical self-theory (Hermans, 2014) highlights the need to incorporate in teacher training and professional development a view of identity construction. This should be done from the incorporation of narrative and critical methodologies, which allow examining how personal experience and teacher training are intertwined, generating a link between the intrapsychological and interpsychological levels of this analysis of the educators’ self. Therefore, training based on contextualized and evidence-based inquiry practices (Lara et al., 2020), reflective and communitarian analysis devices of practices should be promoted, in order to build relevant pedagogical knowledge (Alliaud, 2017; Figueroa-Céspedes & Guerra, 2023; Guevara, 2019) and to facilitate the personal and collective agency of pedagogical teams (Melasalmi & Husu, 2018). In addition, action research-inspired pedagogical work needs to be revitalized as a resource to address the gap between theory and practice (Guerra & Figueroa-Céspedes, 2018).

In conclusion, the analysis of personal positions reveals itself as a useful method to explore the tensions that educators experience within educational institutions, which in turn provides tools to understand institutional micropolitics and its impact on the transformation of teaching practices. Future research could focus on the analysis of educators in training and beginning educators, to understand the dynamism of identity construction during this crucial stage of their training and professional development.

Furthermore, it is essential to assume the challenge posed by Santamaría et al. (2013) to articulate the “micro” dimension linked to experience and voices with the “macro” dimension, associated with production contexts, cultures and policies. This integration makes it possible to reach a situated perspective on the experiences of educators in their professional development, allowing for a more holistic understanding of their work. It should be noted that, although qualitative research delves into the complexity of the phenomena under study, it presents limitations in terms of the generalization of its results, a situation that can be counteracted by using mixed models and expanding the work samples in future studies.

Data availability statement

The data cannot be made available to the public because it is qualitative interviews with personal information of the interviewees and is protected by signed consent.

REFERENCES

Adams, M., & Rodriguez, S. (2020). Using critical incidents to investigate teacher preparation: A narrative inquiry. Teachers and Teaching, 26(5-6), 460-474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1863209 [ Links ]

Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. (2011) A dialogical approach towards conceptualizing teacher identity. Teachers and Teacher Education, 27(2), 208-319. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0742051X10001502. [ Links ]

Akkerman, S. F., & Van Eijck, M. (2013). Re-theorising the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities. British Educational Research Journal, 39(1), 60-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.613454 [ Links ]

Alliaud, A. (2002). La experiencia escolar de maestros “inexpertos”: Biografías, trayectorias y práctica profesional. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 34(3), 1-11. http://doi.org/10.35362/rie3412888 [ Links ]

Alliaud, A. (2017). Los artesanos de la enseñanza: Acerca de la formación de maestros con oficio. Paidós. [ Links ]

Arndt, S., Urban, M., Murray, C., Smith, K., Swadener, B., & Ellegaard, T. (2018). Contesting early childhood professional identities: A cross-national discussion. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 19(2), 97-116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949118768356 [ Links ]

Arteaga, P., Hermosilla-Ávila, A., Mena, C., & Contreras, S. (2018). Una mirada a la calidad de vida y salud de las educadoras de párvulos. Ciencia & Trabajo, 20(61), 42-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-24492018000100042 [ Links ]

Badia, A., & Becerril, L. (2016). Renaming teaching practice through teacher reflection using critical incidents on a virtual training course. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(2), 224-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1143146 [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. (1982). Estética de la creación verbal. Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. (2010). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Dalli, C. (2002). Constructing identities: Being a “Mother” and being a “Teacher” during the experience of starting childcare. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 10(2), 85-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930285208971 [ Links ]

Dalli, C. (2008). Pedagogy, knowledge and collaboration: Towards a ground-up perspective on professionalism. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 16(1), 171-185. [ Links ]

Davis, B., & Degotardi, S. (2015). Who cares? Infant educators’ responses to professional discourses of care. Early Child Development and Care, 185(11-12), 1733-1747. http://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1028385 [ Links ]

Del Mastro, C., & Monereo, C. (2014). Incidentes críticos en los profesores universitarios de la PUCP. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 5(13), 3-20. [ Links ]

Dubar, C. (2000). La socialisation: Construction des identités sociales et professionnelles. Armand Colinf [ Links ]

Fairchild, N., & Mikuska, E. (2021). Emotional labor, ordinary affects, and the early childhood education and care worker. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(3), 1177-1190. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12663 [ Links ]

Fernandes, V. L., & Tonatto-Zibetti, M. L. (2022). Concepções de docentes de Educação Infantil e suas implicações para a atividade de ensino. Revista Eletrônica Pesquiseduca, 14(34), 398-423. https://doi.org/10.58422/repesq.2022.e1246 [ Links ]

Fernández, M. (2012). Aportes de la aproximación biográfico-narrativa al desarrollo de la formación y la investigación sobre formación docente. Revista de Educación, (4), 11-36. https://fh.mdp.edu.ar/revistas/index.php/r_educ/article/view/82/145 [ Links ]

Figueroa-Céspedes, I., Guerra, P., & Madrid, A. (2022a). Construcción de la identidad docente de las educadoras de párvulos: Significados retrospectivos de su Formación Inicial Docente. Perspectiva Educacional, 61(2). https://dx.doi.org/10.4151/07189729-Vol.61-Iss.2-Art.1225 [ Links ]

Figueroa-Céspedes, I., Guerra, P., & Madrid, A. (2022b). Ser educadora de párvulos en tiempos de incertidumbre: Desafíos para su desarrollo profesional en contexto COVID-19. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2692 [ Links ]

Figueroa-Céspedes, I., & Guerra, P. (2023). Huellas biográficas de educadoras de párvulos en su formación inicial docente: Narrativas de la construcción de la identidad profesional. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 31(87). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.31.7657 [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2015). El diseño de investigación cualitativa. Morata. [ Links ]

Gilligan, C. (1985). La moral y la teoría: Psicología del desarrollo femenino. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Gohier, C., Anadón, M., Bouchard, Y., Charbonneau, B., & Chevrier, J. (2001). La construction identitaire de l’enseignant sur le plan professionnel: Un processus dynamique et interactif. Revue des Sciences de L’éducation, 27(1), 3-32. https://doi.org/10.7202/000304ar. [ Links ]

Grau, V., Preiss, D., Strasser, K., Jadue, D., Müller, M., & Lorca, A. (2019). Juego guiado y educación parvularia: Propuestas para una mejor calidad de la educación inicial (Propuestas para Chile, 251). Mineduc. [ Links ]

Guerra, P., & Figueroa-Céspedes, I. (2018). Action-research and early childhood teachers in Chile: analysis of a teacher professional development experience. Early Years, 38(4), 396-410. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2017.1288088 [ Links ]

Guevara, J. (2019). Transmitir el oficio de enseñar: La formación de docentes para el nivel inicial. TeseoPress. [ Links ]

Hermans, H. (2001). The dialogical self: Toward a theory of personal and cultural positioning, Culture & Psychology, (7), 243-281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X0173001 [ Links ]

Hermans, H. (2014). Self as a society of I-positions: A dialogical approach to counseling. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 53(2), 134-159. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2014.00054.x [ Links ]

Joshi, K. R. (2018). Critical incidents for teachers’ professional development. Journal of NELTA Surkhet, (5), 82-88. https://doi.org/10.3126/jns.v5i0.19493 [ Links ]

Kamenarac, O. (2019). Discursive constructions of teachers’ professional identities in early childhood policies and practice in Aotearoa New Zealand: Complexities and contradictions (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Waikato). [ Links ]

Kelchtermans, G., & Vanassche, E. (2017). Micropolitics in the education of teachers: Power, negotiation, and professional development. In J. Clandinin, & J. Husu, The Sage handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 441-456). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402042 [ Links ]

Lara, B., Henríquez, V., & Villarroel, Y. (2020). Voces en la identidad de estudiantes de profesorado. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias En Educación, 19(39), 213-223. https://doi.org/10.21703/rexe.20201939lara-subiabre12 [ Links ]

López, T., Castillo, C., Taruman, J. & Urzúa, A. (2021). Prácticas inclusivas centradas en el aprendizaje: Un estudio de casos múltiples en educación infantil. Revista Educación, 45(1), 1-15. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/440/44064134014/html [ Links ]

Melasalmi, A., & Husu, J. (2018). A narrative examination of early childhood teachers’ shared identities in teamwork. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 39(2), 90-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2017.1389786 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación (Mineduc). (2017). Hoja de ruta: Definiciones de política para una educación parvularia de calidad. Mineduc. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación (Mineduc). (2018). Bases Curriculares de la educación parvularia. Mineduc. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación (Mineduc). (2019). Información relevante Carrera Docente - Educación Parvularia. Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación (Mineduc). (2021). Informe de caracterización de la Educación Parvularia 2020. Cierre. Descripción estadística del sistema educativo asociado al nivel de educación parvularia en Chile. Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia. [ Links ]

Moloney, M. (2010). Professional identity in early childhood care and education: Perspectives of pre-school and infant teachers. Irish Educational Studies, 29(2), 167-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323311003779068 [ Links ]

Moloney, M., Sims, M., Rothe, A., Buettner, C., Sonter, L., Waniganayake, M., Opazo, M., Calder, P., & Girlich, S. (2019). Resisting neoliberalism: Professionalisation of early childhood education and care. Education, 8(1), 1-10. http://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijeedu.20190801.11 [ Links ]

Monereo, C. (2019). The role of critical incidents in the dialogical construction of teacher identity: Analysis of a professional transition case. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, (20), 4-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.10.002 [ Links ]

Monereo, C., & Badia, A. (2011). Los heterónimos del docente: Identidad, selfs y enseñanza. In C. Monereo, & J. I. Pozo (Eds.), La identidad en psicología de la educación: Necesidad, utilidad y límites (pp. 57-75). Narcea. [ Links ]

Monereo, C., & Hermans, H. (2023). Education and dialogical self: State of art (Educación y yo dialógico: estado de la cuestión). Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 43(3), 1-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2023.2201562 [ Links ]

Monereo, C., & Pozo, J. (2014). La identidad en Psicología de la Educación. Necesidad, utilidad y límites. Narcea. [ Links ]

Muñoz-Zamora, G., Silva-Peña, I., Martínez-Núñez, M. D., & Dobbs-Díaz, E. (2022). La educadora feliz: Imaginario en estudiantes de educación parvularia. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 52, Artículo e09303. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053149303 [ Links ]

Nail, O., Gajardo, J., & Muñoz, M. (2012). La técnica de análisis de incidentes críticos: Una herramienta para la reflexión sobre prácticas docentes en convivencia escolar. Psicoperspectivas, 11(2), 56-76. http://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol11-Issue2-fulltext-204 [ Links ]

Navarrete-Cazales, Z. (2015). ¿Otra vez la identidad? Un concepto necesario pero imposible. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 20(65), 461-479. [ Links ]

Noreña, A. L., Alcaraz-Moreno, N., Rojas, J. G., & Rebolledo-Malpica, D. (2012). Aplicabilidad de los criterios de rigor y éticos en la investigación cualitativa. Aquichan, 12(3), 263-274. [ Links ]

Osgood, J. (2006). Professionalism and performativity: The feminist challenge facing early years practitioners. Early Years, 26(2), 187-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575140600759997 [ Links ]

Pardo, M. (2019). Formación de educadoras de párvulos en Chile: Profesionalismo y saber identitario en la evolución de los planes de estudios, 1981-2015 (Tesis de Doctorado. Universiteit Leiden). [ Links ]

Pardo, M., & Opazo, M. J. (2019). Resisting schoolification from the classroom: Exploring the professional identity of early childhood teachers in Chile. Culture and Education, (31), 1-26. http://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2018.1559490 [ Links ]

Pessoa, C.T., Tessaro, N. S., Oliveira, C. C., & Vieira, A. (2017). Concepções de educadores infantis sobre aprendizagem e desenvolvimento: análise pela psicologia histórico-cultural. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, (21), 147-156. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3539201702121093 [ Links ]

Piani, M. (2019). Huellas biográficas de experiencias educativas en la conformación de subjetividades políticas. IE Revista de Investigación Educativa de la REDIECH, 10(18), 207-224. [ Links ]

Pillen, M., Beijaard, D., & den Brok, P. (2012). Professional identity tensions of beginning teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 19(6), 660-678. http://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.827455 [ Links ]

Pinzón, L. (2016). Romper estereotipos de género en la identidad profesional docente: Una propuesta de paz. Educación y Ciudad, (31), 71-81. https://doi.org/10.36737/01230425.v.n31.2016.1610 [ Links ]

Poblete, X. (2018). Performing the (religious) educator’s vocation: Becoming the “good” early childhood practitioner in Chile. Gender and Education, 32(8), 1072-1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1554180 [ Links ]

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage [ Links ]

Robinson, M., Tejeda, J., & Blanch, S. (2018). ¿Cómo construyen su identidad las educadoras de párvulos principiantes? Una mirada desde diferentes realidades educativas. Perspectiva Educacional, 57(3), 104-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.4151/07189729-Vol.57-Iss.3-Art.766 [ Links ]

Rubilar, F., & Guzmán, D. (2021). Procesos inclusivos de la educación parvularia desde la mirada de agentes educativas. Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 21(1), 1-28. https://dx.doi.org/10.15517/aie.v21i1.42517 [ Links ]

Salgado, J., & Hermans, H. (2005) The return of subjectivity: From a multiplicity of selves to the dialogical self. E-Journal of Applied Psychology: Clinical section, (1), 3-13. http://doi.org/10.7790/ejap.v1i1.3 [ Links ]

Santamaría, A., Cubero, M., del Mar Prados, M., & Manuel, L. (2013). Posiciones y voces ante el cambio coeducativo: La construcción de la identidad del profesorado en la aplicación de planes de igualdad. Profesorado, Revista de Curriculum y Formación del Profesorado, 17(1), 27-41. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/567/56726350003.pdf [ Links ]

Sarceda, C. (2017). La construcción de la identidad docente en educación infantil. Tendencias Pedagógicas, (30), 281-300. https://doi.org/10.15366/tp2017.30.016 [ Links ]

Scherr, M., & Johnson, T. (2017). The construction of preschool teacher identity in the public-school context. Early Child Development and Care, 189(7), 1-11. http://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1324435 [ Links ]

Silva-Peña, I., Kelchtermans, G., Valenzuela, J., Precht, A., Muñoz, C., & González-García, G. (2019). Alfabetización micropolítica: Un desafío para la formación inicial docente. Educação & Sociedade, 40, Artículo e0190331. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302019190331 [ Links ]

Sisson, J. H. (2016). The significance of critical incidents and voice to identity and agency. Teachers and Teaching, 22(6), 670-682.http://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1158956 [ Links ]

Susinos, T., & Parrilla, Á. (2008) Dar la voz en la investigación inclusiva. Debates sobre inclusión y exclusión desde un enfoque biográfico-narrativo. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio En Educación, 6(2), 157-171. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/551/55160212.pdf [ Links ]

Tornero, B., Ramaciotti, A., Truffello, A., & Valenzuela, F. (2015). Nivel cognitivo de las preguntas que formulan las educadoras de párvulos. Educación y Educadores, 18(2), 261-283. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/834/83441028005.pdf [ Links ]

Treviño, E., Toledo, G., & Gempp, R. (2013). Calidad de la educación parvularia: Las prácticas de clase y el camino a la mejora Pensamiento Educativo. Revista de Investigación Educacional Latinoamericana, 50, 40-62. https://doi.org/10.7764/PEL.50.1.2013.4 [ Links ]

Valdés, M., & Monereo, C. (2012). Desafíos a la formación del docente inclusivo: La identidad profesional y su relación con los incidentes críticos. Revista Latinoamericana de Inclusión Educativa, 6(2), 193-208. http://www.rinace.net/rlei/numeros/vol6-num2/art8.pdf [ Links ]

Vergara, M. (2014). La identidad de la educadora infantil: Elementos para su comprensión. Pedagogía y Saberes, 1(41), 111-120. https://doi.org/10.17227/01212494.41pys111.120 [ Links ]

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179-198). Springer. [ Links ]

Wertsch, J. (1993). Voces de la mente: Un enfoque sociocultural para el estudio de la acción Mediada. Visor. [ Links ]

Received: January 14, 2023; Accepted: August 11, 2023

texto en

texto en