Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Realidade

versión impresa ISSN 0100-3143versión On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.44 no.3 Porto Alegre 2019 Epub 06-Ago-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623684073

OTHER THEMES

The Diffusion Network of the School without Party project on Facebook and Instagram: conservatism and reactionarism in the Brazilian conjuncture

IUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande (FURG), Rio Grande/RS - Brazil

IIUniversidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPEL), Pelotas/RS - Brazil

This article discusses how conservative thought has been widespread through social networks from supporters of the Movement "Escola sem Partido" (ESP, School Without Party). We start with the analysis of the social medias Facebook and Instagram, seeking to verify who are the supporters of the ESP and the way in which their discourse is structured in social networks. The analysis carried out indicates who the proponents and supporters of ESP are, and states that this proposal is not non-partisan because it has strong links with reactionary groups who seeks to gain power. In addition to that, we find that ESP supporters act militantly in social media, openly disseminating conservative values, especially against debates on gender issues.

Keywords: School Without Party; Social Movement; Conservatism; Social Media

O artigo discute o modo como o pensamento conservador vem sendo difundido por meio das redes sociais a partir dos apoiadores do Movimento Escola Sem Partido. Partimos da análise das mídias sociais Facebook e Instagram, procurando verificar quem são os apoiadores do ESP e o modo como seu discurso se estrutura nas mídias sociais. Apontamos quem são os proponentes e defensores do ESP, bem como que esta proposta não é apartidária, pois possui fortes vínculos com grupos reacionários com projeto de poder. Além disso, verificamos que os apoiadores do ESP atuam de maneira militante nas mídias sociais, difundindo abertamente valores conservadores, em especial contra o debate de gênero.

Palavras-chave: Escola Sem Partido; Conservadorismo; Mídias Sociais

Introduction

Scholarship on the "Escola sem Partido" (School without Party, herein ESP) movement has characterized its proponents as conservatives, starting from the observation of group composition, its modes of actions and advocated proposals (Frigotto 2017; Penna, 2018); the vigilance and criminalization of educators alongside actions to approve legislative bills in cities and states (Carvalho, Polizel and Maio, 2016); as well as its presence in debates and the pressure exerted in the elaboration of the Common Curricular National Basis, which had already been working on an agenda with a typically neoliberal fashion (Macedo, 2017).

ESP proponents are defined by a vindication of a reactionary agenda, in particular relating to issues of diversity and the persecution of leftist political parties. They focus specifically on the gender agenda, demonizing projects seeking to bring into schools the role of tolerance and diversity, and dismissing materials designed to fight off homophobia, transphobia and lesbophobia as "LGBT propaganda" or as a "gay kit", and creating, besides this, a narrative that teachers are "doctrinarians" (César and Duarte, 2017; Moura and Salles, 2018). In general, they seek to control that which is "transmitted" in schools and considering any type of knowledge that is not instrumental - in the capitalist sense of workforce formation - as merely a type of indoctrination.

Considering that we live in a context of propagation of digital culture where there is abundant information available which alters the social and educational role of memory, the adoption of a perspective considered "neutral" is, in fact, a-historical. It generates prejudicial forms of interpretation which are actually contextual and moral to a group. Therefore, the imposition of a role of bureaucrats to teachers as merely "transmitters" of information is both backward and infeasible, besides introducing, at the heart of modern democracy, elements of political of totalitarianism (Guilherme and Picoli, 2018). This produces a stereotypical understanding of reality, which is facilitated, in part, due to an alienated and non-contextual view of the educational process, grounded on a formation mediated by diverse, contextual and emancipatory experiences (Zuin and Zuin, 2016). Such worldviews are potentiated by social media, which then becomes used as a means to propagate different conceptions and, often, biased understandings, which in turn parts from social networks in support of the project and acts (following our hypothesis in this work) in a form of militancy, disseminating materials which are produced by reference groups and particularly those who are perceived as representing the movement's values.

In this article we seek to contribute in the debate on the ESP movement by approaching the contour of its supporters in social media, with the aim of verifying if in fact they are partisans of a reactionary ideology. Thus, the research analyzes the publications of the movement's supporters on Instagram and Facebook and identifies the main characteristics of this network. We understand that the analysis of support networks, of the supporters' profile and content will allow to empirically identify groups sustaining a conservative worldview, which can be done by investigating the content of such publications, specifically, the way in which these messages are aired, their main agendas, against whom they are addressed and the format of the social network sustaining such messages, in particular the references of the group's symbols and its antagonists.

In the first section, the article brings a methodological discussion about social network research, and then it approaches the understanding of what conservative thought is, how it articulates within specific contexts and its relationship to groups, as well as its constitution as a worldview. Then, it presents the ESP proposal alongside their main proponents and contemporary means of action. In the last section, we present the methodology of social media analysis, considering both Facebook and Instagram1, the format of the networks and the main content and agendas. In the conclusion, we resume the argument developed throughout the article with some final remarks, and propose new directions for research.

Paths for Research in Social Networks

We start from the analysis of social networks with a structural approach, which seeks to find existing connections in a given social system grounded in an array of variables (in this case, the ideological self-identification, or yet, the rejection of the "left") and that generates, in turn, a system of interdependence (Lazega and Higgins, 2014) which is also variable, in terms of the network's composition. Such approach understands that it is possible, in virtue of the constitution of these connections, to observe social processes and behaviors which are typical of the group under investigation.

In this sense, it is fundamental to point out that the internet is a diversified space which, in principle, used to be understood as a tool that would necessarily consolidate a democratic ethos due to the possibility of access and sharing of messages by common citizens. However, one perceives, in varied circumstances, the mere reproduction of values rooted in society, in which the possibility of exchange of information cannot be enough for establishing a democratic spirit. As stated by Silveira:

The idea that the internet would encourage participation, and that participation itself is advanced and favorable to the causes of justice, freedom and equality, cannot be sustained empirically. What one observes in networks is the prevalence of common-sense, which often bears with it the force of capitalist ideas and the doctrine of extreme commodification (Silveira, 2015, p. 218).

Thus, social media gives opportunity to the diffusion of many groups' agendas, but this does not necessarily result in the adoption of values related to freedom, plurality and, specially, respect towards alterity. For instance, a research conducted in late November 20172 by the Datafolha Institute, found that the supporters of the then presidential candidate, Jair Bolsonaro, were the most active in social medias. From those who have accounts either in Facebook or Whatsapp (87% and 93%, respectively), 40% and 43% are used to sharing news about the candidate in their networks.

This research was firstly conducted through a literature review around the meaning of conservatism as a social phenomenon, specially from the definition given by Karl Mannheim (1986), and then we moved to consider the ESP movement as bearers of the values of this ideology, presented in the vocabulary and signs introduced by people who came to be representatives of such worldview (Mills, 1963; Pilcher, 1994). With the possibility of visualizing the networks which are structured in social medias and, in particular, considering the reference profiles, we are able to "locate a thinker among political and social coordinates by ascertaining what words their vocabulary contain and what nuances of meaning and values they incorporate" (Mills, 1963, p. 434).

Starting with the analysis of the supporting networks to this project on Facebook and Instagram, we identify what values are transmitted and what adversaries are defined in the defense of such values. For Facebook, we analyze the pages that support ESP3 and with which other pages are intertwined (mentions to other pages), considering for the presentation of the graph size the degree entry and observing, furthermore, the number of likes of each publication (from December 2017).

Next, we analyze the formation of the support networks on Instagram, observing particularly the profile of its main actors. We measure data considering, likewise, the degree of entry for the identification of who they are, in virtue of mentions, comments and shares, which is in turn verifiable due to the size of the node, the representations on ESP and, consequently, as noted, the conservative "intellectuals". In this network, in a somewhat different fashion to Facebook, it was possible to analyze the network from profiles instead of pages.

The Applications Programming Interface (API4) of the social media Facebook presents a series of restrictions to the analysis of network formation (Recuero, Bastos and Zago, 2015), besides recent changes in sharing policy restricting the propagation of some publications, which hinders the analysis of the diffusion of political agendas. Therefore, in this platform we proceeded with the exclusive analysis of the existence of pages (verified in a sum of 104 pages) about ESP and its networks. For this media, we carried out research with netvizz5, a tool that allows to identify within spreadsheets the existing pages on the desired subject, among other data.

For the analysis of Instagram, we defined the search for the hashtag #escolasempartido as a structural element to the identification of the network's configuration:

In order to obtain network data, first it is needed to identify at least one relational or 'structural' variable [...] Once ascertained the existence of this structural variable, we become interested in the more classical variables on the individual level which describes the attributes or properties of actors, for example age, or dependent variables: behavior, performance or yet its representations (Lazega; Higgins, 2014, p. 17).

The analysis of the individual attributes of nodes (individuals) surely would be central to this enterprise, but it is not feasible due to the size of the network in terms of the possible data to be extracted from the available means of information. Thus, we go on to observe the behaviors and representations of the individuals within the network, which are possible to identify due to the logic introduced in publications and comments, particularly of the more central actors of the network. From this we will be able to better grasp what values are shared by the ESP's support network.

One of the measures used is of centrality, considering that "the actor occupying the more central position within a graph is the one which has the most number of direct connections with other actors" (Lemieux; Ouimet, 2008, p. 26).

The network studied in Instagram is constituted, in the majority of cases, by asymmetrical relationships, in which one node is directed towards another one without correspondence. This connection is generated when a comment is made on the publication of one of the nodes. In the case studied, the network generates groups (clusters) related to profiles which are central to its constitution for representing the values which are expressed in the posts through the use of hashtags. Moreover, it is possible to observe the creation of clusters which relate to specific profiles. In our case, we considered the node's degree, which treats the amount of connections that are produced, being either the entry degree (connections that this node receives), which served as our main metric for analysis, and the exit degree (connections produced by the node) (Recuero, 2014, p. 71-72). We also introduce a graph about the Instagram network measuring modularity (set of clusters), which can be understood as communities defined as "groups of nodes densely interrelated and feebly connected to the rest of the network" (Recuero, Bastos e Zago, 2015, p. 84) and as how the latter are constituted around specific profiles, measured by the entry degree.

As such, in order to analyze the ESP support social network, we proceeded to the search of data in the website netlytic6, which allows to visualize comments, the most utilized words and the network's design. The research in Instagram was conducted with a monthly selection of comments, due to the limit of 10.000 registries (considering posts, comments, etc.) in each archive for free website usage. The monthly collection (from October 2017 to January 20187) allowed us to exceed the total number of registries by search without loss of data, and later to aggregate them for the generation of the graph in the Gephi8 program.

Conservative thought in recent Brazilian development

We use in this research the concept of style of thinking as developed by Karl Mannheim (1986) to define the ways in which particular groups act socially. Such styles are created through the participation in certain social spaces which are marked by social, economic, political and other differences that lead to the introjection of specific ways to understand reality, thereby generating a worldview, which in turn is transmitted from childhood and reproduced to a range of social spaces which are dynamic in virtue of clashes among such worldviews (Mannheim, 1986, p. 104).

Thus, such styles of thinking are related to social groups9 sustaining and forming worldviews that have in their root a basic intention, meaning the motivation for social action and which expresses the desires of groups as defined by a certain style and that can be characterized by the ways in which their ideas and forms of actions are transmitted. In this sense,

In our point of view, all philosophy is nothing more than a deeper elaboration of a type of action. In order to understand this philosophy one must understand the nature of action which lies in its roots. This "action", to which we refer, is a special path, peculiar to each group, for penetrating reality, and it takes on a more tangible format in politics. Political conflict gives expression to the aims and purposes operating more unconsciously, yet coherently, in the conscious and semi-conscious interpretations of the world characteristic to the group (Mannheim, 1986, p. 89).

It is necessary, therefore, in order to understand the conservative style of thinking, to identify the supporting groups, the values which are communicated and their forms of action, as well as its basic intention. For Mannheim, conservatism arises from traditionalism. They are, however, separate phenomena.

Traditionalism is essentially one of those hidden traditions that each individual bears in himself unconsciously. Conservatism, on the other hand, is conscious and reflexive since the beginning, to the extend that it arises as a counter-movement opposing the highly organized, coherent and systematic, progressive movement (Mannheim, 1986, p. 107).

In general, we can see traditionalism as a pulsion, a desire to go back into the past, considered as an ideal and which serves as a mobilizing force for conservative movements. Such a vision of valorizing the past leads to the exclusive acceptance of concrete actions, that is, the exercise of projecting social actions that seek to alter the future, as a project, are rejected. Its actions are always oriented towards:

[...] Reaction, when it is forced to develop a system to oppose progressivists or when the march of events deprives it to exert any influence on the immediate present to such an extent that it is obliged to turn the wheel of history backwards in order to reconquer its influence (Mannheim, 1986, p. 112).

Following Nisbet (1986), we also consider the principle of hierarchy and status as a crucial component to conservative thought, which resides in the exercise of authority and has in its root values arising from the past celebrated as ideal. Such an understanding parts from the idea that society is built by relations of interdependence which rests in differences of power, varying from one context to another (economic, cultural, political, etc.). In brief, the latter defines the transmission of values and, consequently, generates stability. As a rule, this difference of status derives from the past.

Authority is legitimate when it derives from customs and traditions of a people, when it is formed by a series of bonds in a current that starts with the family, follows through the community and class, culminating more broadly in society (Nisbet, 1986, p. 71).

This understanding about the distinction between left and right is also present in Norberto Bobbio (2011). To him, the right has as its main values the search for distinction, that is, something which is given and desirable, expressed in maxims such as the exaltation of merit and of social position (Bobbio, 2011, p. 24). In summary, for the right, inequality is immanent to an alleged human nature.

In Brazil, this view was diffused through a social thinking that, from the half of the 20th century onwards, attributes failure in the adoption of meritocratic values to patrimonialism (Holanda, 2004), a phenomenon that contaminates public relations, preventing the free market from performing its civilizing role. On top of this liberal-conservative view arises a public-private binary opposition as a self-evident, holistic category for understanding Brazilian social reality where, on the one hand, the public sphere is confused as inherently corrupt and unqualified, and, on the other, the private sector is seen as a sphere of rationality featuring the virtues of the market, although suffocated by the former (Souza, 2015). This interpretation became adopted as a general model either by academia or by media oligopolies, integrating the common sense jargon (Souza, 2017).

Added to this interpretation is a composition of class structure in the country constituted by a stratum that Jessé Souza (2016) characterizes as the mob10, whose main features are very low wage and exclusion from continuous education (crucial element for the access to better paid activities) and which leads to the undertaking of informal work activities, servile and without labor rights.

This stratum constitutes the majority of the population in Brazil. According to the same author, another class division is composed of the property elites, the middle class and its fractions and the semi-qualified working class (Souza, 2017, p. 107). Such characterization of class composition in the country belongs to the production dynamics locally established and which brings with it, and is sustained by, a series of arrangements whose foundations is the distinction revolving the ownership of cultural, economic, social (among other) capitals (Bourdieu, 2011). These are, however, relationships constituted in society as a whole, and therefore demands a better comprehension, besides the description of strata distinction, of the logic of the societal model in order to define it:

There are authors who use this more restrictively, designating social strata characterized by the existence of a community of interests more or less socially perceived, and usually associated with relations of dominance, of political power and of superposition (also based in differences of social prestige and of lifestyle). Finally, there are authors who apply it as a maxim of historical specificity in order to designate a social arrangement which is inherent to capitalist production. In this sense, social class only appears in places where capitalism advanced sufficiently in order to associate, structurally and dynamically, the capitalist mode of production to the market as an agency of social classification and to the legal order that both required, founded on the universalization of private property, in the [formal] rationalization of law and in the formation of a national state formally representative (Fernandes, 1977, p. 173).

Now that we have understood the relationship between social classes in the local capitalist dynamic, it is necessary to make explicit its transformations, even conjunctural ones, as one of the plausible hypotheses for the development of conservative thought. Therefore, this composition, constituted in a pyramidal format through the 20th century and beginning of the 21st, momentarily sees its base reduced during the offices of the Labor Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT), with a decrease in the number of people in situation of misery, either due to labor market warming or to policies of income transfer which greatly impacted the excluded stratum, or yet to income increase and access to education. Likewise, a significant part of the semi-qualified working class also had improvements in their life quality.

Although insufficient to grasp dynamics of social class mobility, the understanding of income expressed in the division among segments A, B, C, D and E, aids in the perception of change in stratum composition. As noted by Marilena Chauí (2016, p. 15-16):

Through this criterion, a conclusion was reached that, between 2003 and 2011, the classes D and E decreased considerably, from 96,2 million to 63,5 million. In the top of the pyramid, classes A and B increased from 13,3 million to 22,5 million people. But the truly spectacular expansion occurred in class C, from 65,8 million to 105,4 million people.

These transformations, defined by Singer (2012) as weak reformism or as Lulist political economy (reference to former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva) in the liberal social sense, are characterized by the maintenance of structural socioeconomic relationships under capitalism, focusing via state in conjunctural redistributive policies and which, in the Brazilian case, acquires most of its resources from taxation affecting middle class strata, given the absence of big fortune taxation.

Through the agenda that, on the one hand, maintained the lines of action of neoliberal prescription, and, on the other, made decisions on the contrary, that is, from a progressivist platform, a sui generis combination of change and order was forged, provoking the electoral shifting of the subproletariat (Singer, 2012, pos. 2897 [ebook]).

Even considering those limitations, the PT period in government resulted in significative conjunctural change in income redistribution via state and, consequently, in an improvement in consumption capacity, generating, according to Marilena Chauí, the adoption of ideological values by the middle class, usually individualist ones, sustaining a position of distinction precisely in its consumption capacity, an understanding also shared by Reich (2012), who views that it is natural to the middle class to bear a conservative worldview, which is exacerbated in moments of economic crisis.

To the author, there are two ideological variations, the first being a "theology of prosperity" drawn from neo-Pentecostalism, usually traditionalist, and second an "ideology of entrepreneurship" with neoliberal traces, which tends to address its criticisms to "state interventionism" for negatively interfering in individual freedom (Chauí, 2016, p. 20). Both views, even when considering variations in reference groups, are part of the same basic intention which parts from immediate relationships and a valorization of the past.

Both forms can be manifested in distinct groups, but these can also, under certain circumstances, unite. For instance, the Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL) movement11, which initially disseminated an emphatic "liberal" discourse against the state and in favor of entrepreneurship, started to defend more strongly conservative agendas in 2017, as was the case with the persecution of the Queermuseum exhibition12 at the Santander Cultural, in the city of Porto Alegre (capital of the Rio Grande do Sul state). This case revealed, to our understanding, a strategy to seek help from conservative groups along with a demonization of the left. Conversely, former congressman Jar Bolsonaro (today president of Brazil), notoriously known for the backing of conservative proposals, started to disseminate that he was a "liberal" in economics, as an electoral strategy for his candidacy. Apple (2002, p. 56), when analyzing the conservative alliance which is redirecting educational policies worldwide, claims that

It would be too simplistic to interpret that what is currently going on in the educational system merely translates into an effort made by the dominant economic elite to impose their belief and desires to education. Much of these attacks represent an attempt to reintegrate education in the economic agenda. However, these attacks cannot be reduced to this or revolve on economic issues alone. Cultural and polemical conflicts about race and gender coincide with class alliances and with class power.

It is important to stress that, as pointed by André Kayssel (2015), the union between economic liberalism and conservatism is not new in Brazil, constituting conjunctural deals set to attack progressive forces since the Empire (1822-1889), the First Republic (1889-1930) and the political blocs that attacked former presidents Getúlio Vargas and João Goulart. Therefore, what we perceive regarding the characteristics of conservative thought is the existence of an institutional attack to the conjunctural victories achieved during the PT cycle, specially concerning income distribution, labor and human rights. As noted by Boito Jr. (2016, p. 27), even with its limitations, the Lula and Dilma governments "[...] implemented a cultural policy more favorable to the feminist, LGBT and black movements", which ultimately represented, to conservative groups, an affront to their worldview based on status quo.

In the aftermath of the 2016 civic-business-media-parliamentary coup, the evangelical bench in congress, the most expressive representative of conservative thought, started attacking more firmly the agendas put forth by progressive movements, and gained considerable influence during the Temer office (2016-2018) in exchange for support in the voting of the new neoliberal labor legislation. This is the group which popularized the term "gender ideology" and has as its main focus for action the creation of legislative bills opposing diversity and LGBT rights, besides being the main responsible behind the exclusion of the term "gender", "sexual education", and "sexual orientation" from the National Education Plan (NEP) debated in 2014 (DIP, 2018). This is the current context where conservative thought has advanced in Brazil, and in which the School without Party movement gains visibility and emerges as an educational proposal in different spheres of the Brazilian congress.

The School without Party Movement

The ESP movement was founded in 2004, led by Miguel Narciso Urbano Nagib, a state prosecutor from the state of São Paulo. The ESP defenders claim that the project emerged from the need to protect students in school, for the majority of teachers allegedly preached an ideology deemed harmful in class. In the movement's website13, it is declared that in Brazil there is currently a widespread practice of "harassment from political and ideological strands and groups with clearly hegemonic pretensions" attempting to indoctrinate students, and which is, according to the project's authors, supported by schools and authorities. Those engaged in such a project of "social engineering" would be acting analogous to kidnappers by causing a "Stockholm syndrome" in students. In other words, students who don't share the values of the ESP project, in particular those taking part in student unions (having as main target academic directories, student's central directory and especially members from the Brazilian Communist Party, PCdoB), suffer from a "psychological problem".

It is noteworthy that the ESP was inspired by a movement which arouse in the United States named No Indoctrination and founded by Luann Wright, when he "perceived a critical bias in the text of his son's literature teacher who oriented reading articles which were qualified, according to her, as 'biased' about racism from white people against blacks" (Espinoza and Queiroz, 2017, p. 50). Just as with No Indoctrination, ESP uses a false neutrality and apolitical stance in order to question schools and its teachers, besides disseminating conservative conceptions. It should be highlighted that the movement's coordinator, Miguel Nagib, was an articulator from the Millennium institute, a conservative organization formed by businessmen, journalists and liberal professionals. Nagib authored articles and donated to the institute14.

Nagib also declared admiration to the Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL) movement and to Jair Bolsonaro, apart from being a frequent participant of groups and debates which are self-declared conservatives or right-wing, as stressed by Espinoza and Queiroz (2017, p. 55):

Some of the events of which Nagib participated: lecturer at the I Foundation Congress of the Conservative Party, held in Curitiba on June 2015; lecturer at the I Congress of Evangelical Political Agents from Brazil (Capeb), event organized by the Evangelical Legislative Front (FPE), which would be held in October 2015 but was canceled (among the lecturers were Congressman Eduardo Cunha from PMDB/RJ party and the preacher Silas Malafaia); interviewed in the 'Conexão Conservadora' program, a podcast without periodicity which discloses interviews and program series on conservatism and which is hosted by Alex Brum Machado; interviewed in the virtual program 'Papo que Bate', hosted by Bia Kicis; interviewed in the program "Terça Live", hosted by Allan dos Santos, part of a project that emerged in 2014 as a reaction to what he calls election 'fraud' in 2014. The founders consider themselves followers of Olavo de Carvalho.

There is, therefore, in Nagib's interpretation, "indoctrination" when the values of the groups he is part of are not disseminated.

The narrative construction of the ESP is the one observed by Mannheim (1952) aiming to deconstruct the participation of an adversary by presenting him or her as ideological to the common sense, as something which distorts reality, and, consequently, to present one's very own worldview as reality. This occurs especially with the advance of conservative expressions in daily life and that start to treat this worldview as a normality:

The [ESP] uses language 'which is near common sense, recurring to simplistic dichotomies which reduce complex issues to false alternatives', and expands itself through the use of memes, 'images that accompany brief sayings', through four main elements: first, a conception of schooling; second, a disqualification of the teacher; third, fascist discursive strategies; and lastly, the backing of the total power of the parents over their children'. It contains fascist discursive strategies through the use of 'analogies addressed to teachers, dehumanizing the teacher' by treating him or her as a 'monster, a parasite, a vampire' with the use of offensive memes. Including of Gramsci and Paulo Freire. It instates an 'environment of denunciation' and of 'hate speech' (Ciavatta, 2017, p. 9).

With this agenda, political organizations with a reactionary imprint articulate, using the ESP project as electoral platform and promoting themselves with distorted constructions about debates that are made in schools, besides presenting themselves as defenders of traditional values of Brazilian society and acting with violent and by defamatory means (Ciavatta, 2017, p. 11-12).

Although the movement emerged in 2004, it was only in 2014, from a request by the then Rio de Janeiro state congressman, Flávio Bolsonaro, that Nagib elaborated a bill project enabling the suppositions of the ESP. The bill n. 2974/2014, proposing the creation of the School without Party program, was then presented in May at the Legislative Assembly of the Rio de Janeiro state. In the same year, Flávio Bolsonaro's brother, the Rio de Janeiro city councilor Carlos Bolsonaro, presented in the Rio de janeiro City Council a project with the same content. With these two initiatives, Nagib made available on the ESP website the legislative bill models, to be consulted and copied by any legislator that wanted to present it to their respective legislative chambers.

In 2014 and 2015, the ESP gained large visibility. In 2015, the legislative bill n. 867/2015 was presented to the Federal Congress by congressman Izalci Lucas Ferreira (PSDB-DF party), who also defended ESP propositions. This project brings among its proposals the end of the quota system for admission in universities and reduction of high school duration years, from nine to six. It is also common to refer to subjects such as History, Sociology and Philosophy as the main responsible for alleged "indoctrination", suggesting that they be substituted with religious teaching and that the module of Morality and Civics returns to the curriculum (Neto and Santos, 2017, p. 169). Congressman Izalci, just like the absolute majority of legislators who defends ESP (including the Bolsonaro family), maintains direct relation to neo-Pentecostal organizations (Espinoza and Queiroz, 2017, p. 60), which is the foothold of the project both in the Federal Congress and in states. ESP arrived in the Senate in 2016 with the bill n. 183/2016, singed by former senator Magno Malta (PR-ES).

Its defenders, as noted by Penna (2017), part from a view that schooling is synonymous to training/instruction, whereas education should be left to families and church. With this, they defend strategies of demoralization of education professionals by making use of fascist discourses (visible in "apolitical" discourses, but with pragmatic relationships, without exceptions, to right-wing parties and neo-Pentecostal organizations, besides the aggressive and defamatory tone to opponents, always tied to progressive proposals), and, finally, postulate a vision about the family institution based on the absolute possession or power over children. This discourse has had acceptance even among teachers, to whom the adoption of neutrality and their dissociation to education are merely seen as political instruction. However, Saviani (2017, p. 231) highlights that:

By proclaiming the neutrality of education in relation to politics, the targeted aim is to stimulate an idealism of teachers by making them believe in the autonomy of education in relation to politics, what will ultimately lead them to reach an inverse result: instead of, as is believed by them, preparing their students to act autonomously and critically in society, they will be acting to better adjust students to the existing order and to accept the conditions of domination to which they are submitted. This is why the ESP proposal originates from political parties situated at the right of the political spectrum, especially the PSL (Social Christian Party) and the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democracy Party), seconded by DEM (Democrats), PP (Popular Party), PR (Republic Party), PRB (Republican Brazilian Party), and the more conservative segments of the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party).

In the wake of this thinking which reduces the social role of education and the teacher's role under an ideology of knowledge neutrality, Frigotto (2017) claims that what is actually hidden is the privatization of thought. For the ESP movement, besides the act of educating being dissociated from the act of teaching, school education assumes a role of a commodity, in which the teacher provides a service to the student who in turn is a seen as a consumer. Nagib (2013) has already stated that he designed the ESP project from the Brazilian Consumer's Defense Code.

The ESP movement, in a wordplay, tries to hide its ideological and political orientation - which is also authoritarian -, seeks to criminalize teachers, threatening the role of public school towards a more humane formation grounded in the values of freedom, rights and respect to diversity.

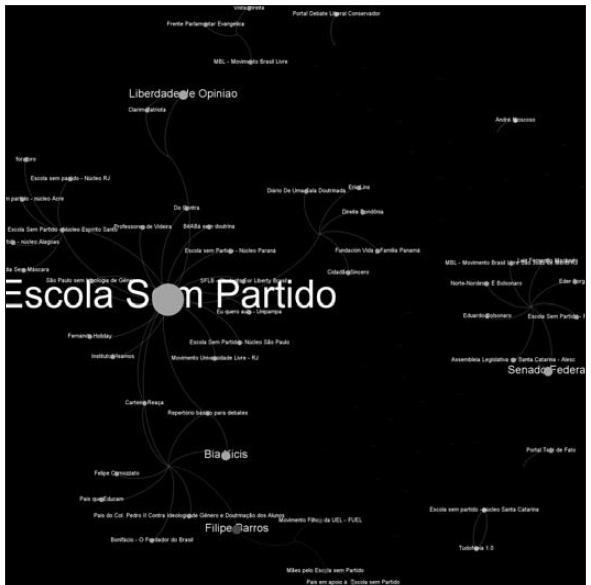

ESP Support Pages in Facebook

The following network brings the modularity and entrance degree of the ESP support pages in Facebook, as well as its relationship according to the amount of likes made in other pages, which builds up the network:

In Facebook, the most relevant network (considering the number of likes) is the Escola sem Partido (School without Party) page, managed by the project's very creator, Miguel Nagib, together with another administrator. The page counted, in November 2017, with 158,121 likes. Its publications revolve on the dissemination of Nagib's discourses in defense of ESP and of "denouncements" against "indoctrination" in schools, especially against public universities. It is common to the page to expose teachers and research groups dealing with issues such as gender (which they label as "gender ideology") and Marxism, promoting the persecution against them. This is evidenced in the post reproduced below:

Source: Escola sem Partido Facebook page (2018).

Image 1 post from the Escola sem Partido page on Facebook* The post translates as: "Brazilian university: ideological tumor inside the state. #chemotherapynow".

The page mentions related pages, representing the movement's regional cores and which also mentions São Paulo city councilor Fernando Holiday, who was elected by the Democrats party (DEM) and is a militant of the Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL). This councilman is known for making videos attempting to "inspect" schools in favor of the ESP project.

We can also note the existence of another network created by evangelical groups in support of the project and which constructed a network with support pages to Jair Bolsonaro and the MBL movement. Other personalities are also present, such as Beatriz Kicis16, state prosecutor in the Federal District, member of the Foro de Brasília (Brasília Forum)17 and ESP supporter who holds openly conservative views.

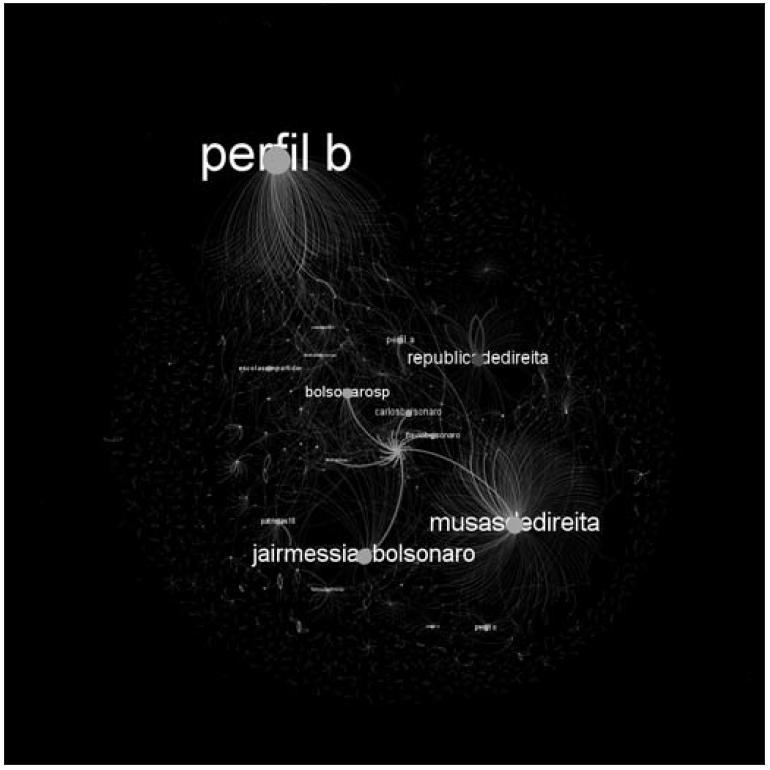

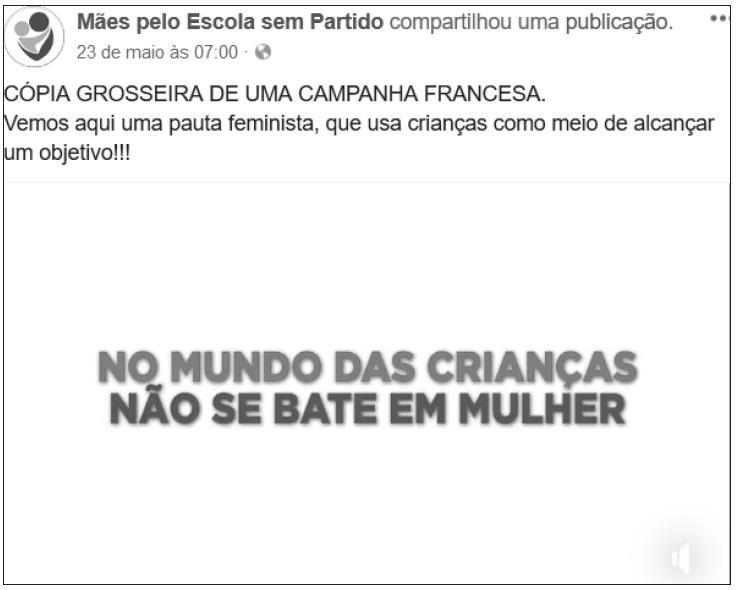

The second project's support page in terms of number of likes is the Mães pelo Escola sem Partido (mothers in favor of ESP), which counted in December 2017 with 21.142 likes. This page reproduces publications from Miguel Nagib's page, and comments especially on the issue of gender "indoctrination". One of the "denouncements" is about a campaign against gender violence, which uses children in a video to explain the theme:

Source: Mães pelo Escola sem Partido page on Facebook (2018).

Image 2 Post from the Mães pelo Escola sem Partido page on Facebook

The network, which is constituted around the ESP, brings forth a conservative discourse, presenting an agenda of traditional values which is expressed in the definition of an antagonist, as for instance, the issue of gender, which is then redetermined in a way to distort the aims of the actual debate. While the debate seeks, among other things, to promote the acceptance of diversity as a way to avoid violence, or yet, to promote sexual education, the ESP proponents disseminate that it tries to deny biology, to convince children that sexual orientation does not exist (what they term as "sexual option") and that the latter would serve to stimulate sex.

By doing that, they also incite persecution18 to teachers treating issues regarded as "indoctrination", and promote the use of books addressing teachers as instructors instead of educators19. In this discursive production they do not present themselves directly as conservatives, but use conservative agendas (usually of Christian religion, based on an idealized family with "traditional" values and the demonstration of legitimacy in the use of national symbols related to such values) as instrument of constituting a "normality" which should be correct and desired for the behavior of nationals, especially in relation to customs, and also focusing on children and the youth, taken to be victims of an alleged "indoctrination" of what is generally considered progressive agendas (human rights, gender, religious diversity, Marxism, sexual education).

ESP Support Networks in Instagram

After the quantitative analysis of the Facebook pages and its relationships, we set out to the study of Instagram.

In the temporal analysis of the emergence of the #escolasempartido hashtag in Instagram, made from march 2017 onwards, we perceive that the hashtag starts to be broadly deployed by a network bringing a set of other terms as ideological markers, not being reduced only to the agenda of defending the ESP project, but revolving on values which are presented by its authors as characteristic of the right.

Between March and April, there was only one publication about ESP, made by a professor who brings out an image criticizing alleged "indoctrination" in universities, besides other hashtags which carry similar agendas: #universidadelivre (free university), # faculdadesempartido (university without party), #escolasempartido (school without party), #bolsonaro 2018, #pensamentolivre (free thinking). In the period from April to September there were no entries.

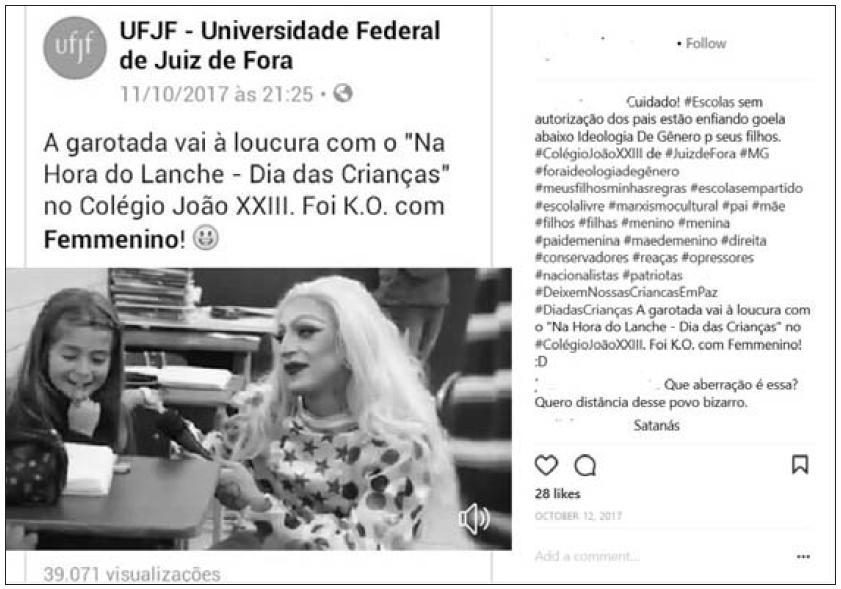

The analysis of the ESP support network was made between 1st of April 2017 and 31 January 2018. The hashtag starts to be broadly used from 12 October 2017 onwards by a user (perfil A, or profile A in English) favoring the project. This user shared an image from the Instagram profile of the Federal University of Juíz de Fora, which aimed at raising awareness over diversity, and this user understood this image to be an "example" of "gender ideology", as follows:

Source: Instagram (2017). Republished by profile A.

Image 3 Profile A post in Instagram* The post translates as: "Careful! #Schools are forcefully disseminating Gender Ideology to children. #SchoolJoãoXXIII from #JuizdeFora #MG #goawaygenderideology #mychildrenmyrules #schoolwithoutparty #freeschool #culturalMarxism #father #Mother #Sons #Daughters #boy #girl #right #conservatives #reactionaries #opressors #nationalsits #patriots #LeaveOurChildrenInPeace ##Children'sDay # [reproduces original post:] Kids go crazy with 'Lunch time - Kids day' at #SchoolJoãoXXIII. It was K.O. with Femmenino! :D. What an aberration is this? I want distance from this bizarre people. Satan".

This image was shared by perfil A (profile A) and it triggered its dissemination to the ESP support network. It is possible to observe in the hashtags list the identification markers of the group, such as: #right, #conservatives, #reactionary, #opressors, #nationalists, #patriots, #goawaygenderideology, #mychildrenmyrules, #schoolswithoutparty, #freeschool, #CulturalMarxism, #father, #mother, #sons, #daughters, #boy, #girl, #fatherofagirl, #motherofaboy, #prayer, #OurFather, #civism.

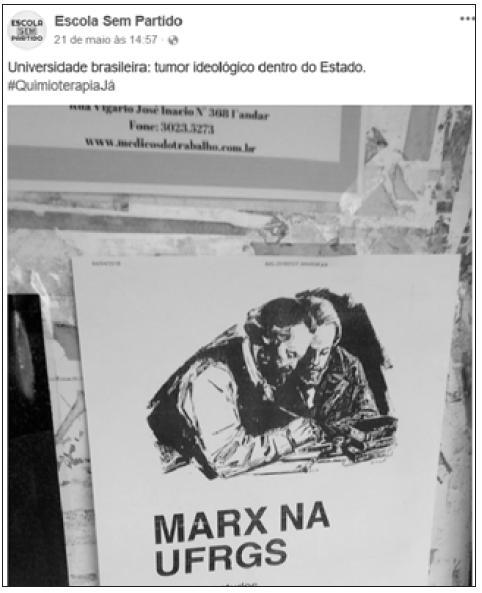

The network mentioning the #escolasempartido hashtag has 3.260 nodes and 4.759 edges, and presents the configuration according to Graph 2, which takes in account the analysis of modularity and entrance degree of the nodes. In this sense, the most visible nodes are the ones which receive greater number of mentions and likes, becoming central to the ESP support network. Again, we part from the analysis of the hashtag #escolasempartido (school without party) as shown in the graph20 below:

Considering the period of analysis and the entrance degree, the most relevant profiles in the ESP support network on Instagram are the following:

Table 1 ESP support profiles in Instagram

| User | Publications22 | Followers | Profile’s self-description |

|---|---|---|---|

| perfil B | 2.731 | 3.179 | Declares himself/herself as a con servative, patriot, Christian, in favor of rearmament and supporter of Bolsonaro23 |

| musasdedireita | 761 | 18.300 | “Nobody is forced to support Bolso naro, but learn to respect this page in order to avoid being sued!” |

| jairmessiasbolso- naro |

1252 | 1 million followers | “Parachutist Capitain of the Brazil ian Army, Federal Congressman elected from Rio de Janeiro” |

| republicadedi- reita |

531 | 8.563 | “Members of the @AdmsDeDireita CD #BolsonaroPresident” |

| bolsonarosp | 4.220 | 488 mil | “Eduardo Bolsonaro Federal Police officer, lawyer (Law UFRJ), son of Jair Bolsonaro. Fed eral Congressman elected from São Paulo (82.224 votes). Twitter: Bolso- naroSP #eduardobolsonaro” |

| perfil A | 13.391 | 7.536 | No description24 |

| carlosbolsonaro | 1.244 | 177 mil | “Son of Federal Congressman @ jairmessiasbolsonaro, most voted City Counselor in the city of Rio de Janeiro for his fifth mandate (106.657 votes)” |

| flaviobolsonaro | 1.566 | 223 mil | “Flávio Bolsonaro #Bolsonaro #Bolsonaro 2018 Pa triot, conservative, lawyer, busi nessman and reactionary, I react to everything which isn't right” |

| escolasempar- tido |

6 | 1.621 | No description |

| patriotas18 | 515 | 5.090 | “Patriot, Rearmamentist, Anti drugs, Pro-life, Right-Wing Ad- ministators with Bolsonaro” |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Upon analyzing the entrance degree, we note that the most relevant users are perfil B (profile B) (with publications against the left and in favor of Bolsonaro), musasdedireita (with publications of women wearing t-shirts in favor of Bolsonaro), jairmessiasbolsonaro, republicadedireita, bolsonarosp and profile A (user who started disseminating the hashtag against "gender ideology"). Some profiles become a reference point, especially the ones from the Bolsonaro family, not only by treating the issue of ESP, but because the hashtag #escolasempartido, as stated before, started being marked in publications promoting his candidacy for president, and Bolsonaro, in turn, is mentioned in any publication which has a conservative content. The participation of the Bolsonaro family in the defense of the project is also relevant for it became an agenda to their political platform which consequently gave visibility along with his constituency, as expressed in the image below:

Source: ESP Facebook page, published on 22 May 2017.

Image 4 Advertising poster for a public hearing* The poster translates as: "School without Party Public Hearing. Rio de Janeiro City Council, 18:00". Speakers: Carlos Bolsonaro (City Counselor), Carlos Jordy (City Counselor), Beatriz Kicis (state prosecutor) and Eduardo Bolsonaro (Federal Congressman).

The presence of the "School without Party" term in social media is only one of the ideological markers for the identification the network and which gives relevance to those who espouse general conservative values. In the example below, one sees a recurrent method for when ESP is treated on Instagram publications, which are usually contrary to gender debates:

Source: Profile B Instagram post, published on 12 October 2017.

Image 5 Perfil B (profile B) post in Instagram* The image readapts a widely circulated magazine in Brazil, changing the original headline "My son is Trans" to "My car is a Transformer".

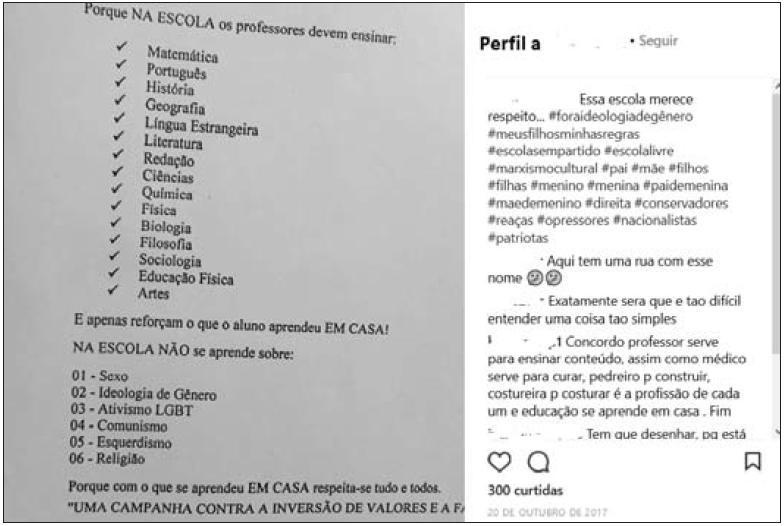

Profile A treats more about ESP in its publications, also rejecting gender issues and stressing that the school should be responsible for instructing, delimiting subjects by content and inferring on the existence or not of indoctrination. Here it is central the understanding that both values and education are a strictly family matter:

Source: Profile A Instagram post, published on 20 October 2017.

Image 6 perfil A (profile A) post on Instagram*The post allegedly shows a conservative campaign addressing the subjects that should be taught in school, leaving out issues such as "Sex", "Gender ideology", "LGBT activism", "Communism", "Leftism" and "Religion". The start of the post translates as: This school deserves respect... #goawaygenderideology #mychildrenmyrules, #schoolwithoutparty, #freeschool #culturalmarxism #father #mother #sons #daughters #boys #girls #fatherofagirl #motherofaboy #right #conservatives #reactionaries #opressors #nationalists #patriots [...]

In this section, we sought to show evidence to how conservative discourse is being disseminated on Instagram social media with ties to the ESP movement, and that there are some public figures with typically conservative political agendas, like the Bolsonaro family.

Final Remarks

The review of material produced by the ESP movement and the profile analysis of its proponents, as well as its social networks, allowed us to identify both the agenda and its support network, especially against whom it is designed to address. It is correct to affirm that this group is composed by individuals with conservative, Christian beliefs (especially the neo-Pentecostal strand, although not exclusively) and with direct links to right-wing parliamentary members to whom the ESP constitutes only but one agenda seeking to be implemented as a project of institutional power, and being directly referenced to the then candidate and now President of the Republic, Jair Bolsonaro.

Discursively, the movement aims to demoralize its opponents through a strategy of agenda disqualification, sometimes taken as indoctrination, at other times as a "project of family destruction" (such as the case of gender debates), and treating leftists (often regarded as "terrorist" organizations) as enemies of the country. By relating progressivist agendas to specific groups (Marxists, gays, feminists, teachers, etc.), they consolidate the ESP agenda via social media, which, as stated before, does not usually favor open dialogue.

Thus, when verifying who the ESP proponents are, we consider important to express that this proposal is deceitfully advertised as non-partisan, but actually emerging from reactionary groups linked to far-right political parties and liberal and conservative organizations, having thus a well-articulated power project. Neo-Pentecostal organizations and part of the Catholic Church take part in this group, as well as conservative parties and non-governmental organizations such as MBL, Revoltados Online, among others. Jair Bolsonaro stands out as their exponent, member of the evangelical bench in Congress and outright apologist of the military dictatorship, acting along with his sons.

After analyzing the ESP support network, we perceived that its defenders act in a militant way in social medias, attempting to disseminate - without there being a need to reveal this aspect, for they put it openly - conservative values, especially the neo-Pentecostal agenda, against gender debates as well as other issues treated as components of these values and whose action ended propelling Bolsonaro's presidential candidacy. Therefore, we understand that the project's name is a fallacy, for it derives from previously articulated groups with a reactionary power project and seeking to make invisible any type of agenda dealing with diversity, even in the school environment, and also considering that the latter should not envisage any sort of political experience from the values which are not defended by these groups. Starting from a discourse grounded on common sense and with easy accession, we note in the ESP movement a strongly conservative perspective which is disseminated via digital social medias and reaching out to civil society, religious organizations and right-wing political parties.

In conclusion, we understand that the ESP, with its complex network of articulation, both in terms of political power, civil society organizations and the dissemination of values through social medias, demands an opposition at the height of the challenge it imposes on education and the threat it represents to Brazil's democracy (Penna 2016; Guilherme and Picoli, 2018; Macedo, 2018). Presently, the correlations of forces in the Brazilian political conjuncture does not allow one to presume a balanced debate and political dispute, considering the new phase of neoliberal attacks on welfare and its alliance with the far-right, both in Brazil and elsewhere.

At this point in time, we consider important to sustain a broad national front, just like the Professores Contra o Escola sem Partido (Teachers against ESP) movement25 and the Frente nacional Escola sem Mordaça (School without Muzzle National Front)26, aggregating academic, political and civil society segments currently engaged in raising awareness to a more plural, democratic and emancipatory education. This front has been fundamental to obstruct the legislative bill project, both at the federal, regional and city levels, and also in the dissemination of daily modes of defense against ESP27, which gives information on teacher's basic rights so that they do not feel constrained in performing their role as educators as currently prescribed in the country's law and also in international treaties to which Brazil is part of. Therefore, teachers should not give in to the temptation of self-censorship, which is a result of the politics of fear currently being disseminated by social media, for it privatizes the debate to such an extent that families feel empowered to impose their conservative worldview against the pedagogical work of teachers in school. Although it is understandable cases of self-censorship due to financial issues (when teachers work in private schools, for instance), it is important that teachers integrate strong collectives such as educational associations and unions linked to education28.

Finally, as the empirical case of social media here demonstrates, the dispute revolving educational curriculum in Brazil has boiled over specialized pedagogical and juridical means, transforming itself in a commonsensical, populist electoral platform. Thus, it is reasonable to suppose that any resistance to ESP should go beyond universities and specialized academic circles, seeking to reach the minds and hearts of both the population and relevant groups. Although clearly not sufficient, engagement in social media is a necessary element of combat. Just to give one example from our own experience, in December 2018, the authors of this article released on Youtube the feature version of the documentary School without Censorship, a film which seeks to raise awareness on the perils of ESP29. Within a couple of months, the documentary had reached an audience much larger than it would have in specialized academic publications for years. This reveals the need of more accessible narratives for the dissemination and democratization of knowledge, which is not equivalent to giving up on scientific production but to give proper attention to the transformation in the means of appropriating knowledge in times of post-truth and fake news. In fact, this claim ends up demanding much more from researchers, who for years have been spectators of the scrapping of science in Brazil, in the sense of thinking about alternatives to popularize their respective contributions to knowledge. Before new demagogues kidnap once again qualified debates in society, and, with populist tactics grown in social media, ultimately end up winning yet more elections, next time maybe even appealing to the flat Earth conspiracy!

1We recommend Romancini's (2018) article on the news coverage of ESP and the use of the #escolasempartido hashtag on Twitter. In the news media, one notes that the issue is treated either neutrally or unfavorably towards the project, while on Twitter there is a much more favorable engagement, where the profile of its supporters are mostly made of conservatives, a finding which is similar to ours.

2"Eleitor de Bolsonaro é o mais ativo nas redes, diz Datafolha [Bolsonaro's voters are the most active in social media, says Datafolha]". Available at: <http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2018/01/1947267-eleitor-de-bolsonaro-e-o-mais-ativonas-redes-diz-datafolha.shtml>. Access on: 05/20/2018.

3The chart with the total of pages, considering likes and comments at the time is available at: <https://docs.google.com/spreadsheetsd/1PnlweghKu3YRd4CDi9jpDIP4_gy_D3aW3VCoK2rTS_M/edit#gid=1037977098>.

5Available at: <https://apps.facebook.com/netvizz/>. Acesso em: 10/10/2018. This application allows to analyze, among other information, the pages and open groups about a given subject.

6Available at: <https://netlytic.org>. Access on: 10/10/2018. The website allows to access networks in a range of different social medias (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Youtube, etc.), considering the restrictions of the APIs of each one of them.

7Registries per month: October/2017 had 3.385 registries (333 posts with loops, 868 loops and 2.215 profiles mentioned); November/2017 had 4.908 registries (376 posts with loops, 1.206 loops and 2.812 profiles mentioned); December/2017 had 3.178 registries (354 posts with loops, 1.155 loops and 2.088 profiles mentioned). January/2018 had 6.861 registries (525 posts with loops, 1.525 loops and 2.744 profiles mentioned). In total, there were 18.322 registries.

8Available at: <http://gephi.com/>. Access on: 09/10/2018. The program allows to generate graphics from networks extracted from various sources. In the case of this research, they were extracted from netvizz (for Facebook) and from netlytic (para Instagram).

9The same style of thinking can be identified in a series of different groups, which sustain common values but do not necessarily constitute organizational unity. For instance, the group Revoltados Online (Online Revolts, disseminator of reactionary agendas on social medias. More information available at: <https://twitter.com/revoltadoonline>. Access on: 19/04/2019) is conservative, as well as the Christian Social Party (PSL), which agglutinates a range of parliamentarians who put forth agendas in Congress at odds with Human Rights protection (more information available at: <http://www.psc.org.br/deputadosdo-psc-defendem-o-projeto-escola-sem-partido/>. Access on 19/04/2019).

10Following our interpretation, it is possible to also define as under-proletariat part of the working-class population which is hyper-poor (Singer, 2012). This strata, according to Singer, gave support to the Labor party governments from 2002 onwards.

11A movement which, after investigation, was found that had been financed by North American business groups, usually from right-wing foundations, specially the Koch brothers (Amaral, 2016, p. 50-51). More information available at: http://mbl.org.br/ Access on 19/04/2019. On the MBL proposals in the area of education, which includes the defense of ESP and the legalization of homeschooling, see: <http://mbl.org.br/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/propostas-mbl.pdf>. Access on 19/04/2019.

12"Queermuseum - Cartographies of difference in Brazilian art" is a Brazilian art exhibition reuniting a series of works dealing with expression and gender identity, diversity and difference.

13Available at: <http://www.escolasempartido.org>. Access on 15/10/2018.

14On the Millennium Institute, see: cf. <https://www.institutomillenium.org.br/>. Access on 19/04/2019. For articles written by Miguel Nagib in the same institute, see: <https://www.institutomillenium.org.br/etiqueta/miguel-nagib/>. Access on 19/04/2019.

15The graph may be visualized in colors in the following link: <https://drive.google.com/file/d/1n_sZqssgCvry54Jw3ns6AkGbODTrK8JU/view?usp=sharing>.

16Kicis has a Youtube channel with approximately 64 thousand subscribers, producing content which varies from denouncements of "leftist" people to the defense of the military dictatorship. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeCm6AiQfKamRlBHOGPNVOg>. Access on 10/11/2018.

17The Brazilian Forum is a non-party organization bearing the slogan "force and honor" and having as its main objectives an opposition to the São Paulo Forum. Among their projects, there is a revocation plea of the Resolution n. 11 from 18 December 2014, issued from the Human Rights Office, which establishes parameters for the inclusion of the items "sexual education", "gender identity" and "social name" in bulletins issued by police authorities. More information available at: <www.forobsb.com>. Access on 10/10/2018.

18It is common to the cited pages to advertise class videos with "persecution denouncement", or yet, the disclosure of photos and links of the personal profiles of those who oppose ESP.

19Such as the book "Teachers are not educators", from a link made available in the page Mothers in favor of ESP": <https://shoutout.wix.com/so/4MDzZ7gU#/main>. Access on 10/11/2018. The book highlights that the role of teachers is solely the instruction of contents.

20Link for the archive in the gephi format: <https://drive.google.com/file/d/12q9dbGf2p85TNa9r65fOkNDWSmOcAUmt/view>.

21The graph may be visualized in color in the following link: <https://drive.google.com/file/d/1n_sZqssgCvry54Jw3ns6AkGbODTrK8JU/view?usp=sharing>.

23We do not present the self-description of personal profiles, even if they keep publications public, in order to preserve the privacy of these users.

24The publications from this profile are usually in favor of the military dictatorship, the candidacy of Jair Bolsonaro and against the left in general, especially against the Worker's Party (PT).

25More information available at: <https://profscontraoesp.org/>. Access on 19/04/2019.

26More information available at: <http://escolasemmordaca.org.br/>. Access on 19/04/2019.

27See the "Defense manual against Censorship in Schools", organized by a range of social movements opposing ESP. Available at: <http://www.manualdedefesadasescolas.org/manualdedefesa.pdf>. Access on 19/04/2019.

28Here we refer to associations such as the National Association of Post-Graduate and Research in Education (ANPED), the National Association for the Formation of Education Professionals (ANFOPE), the National Association of Educational Policy and Management (ANPAE), the Center for Studies on Education and Society (CEDES), among others engaged in a historical struggle for the valorization of teachers, of public, lay, gratuitous, democratic and plural schools.

29Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vejqvQyppnI&t=201s>. Access on 19/04/2019.

REFERENCES

AMARAL, Marina. Jabuti Não Sobe em Árvore: como o MBL se tornou líder das manifestações pelo impeachment. In: SINGER, André [et al.]. Por Que Gritamos Golpe?: para entender o impeachment e a crise política no Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2016. [ Links ]

APPLE, Michel. "Endireitar" a Educação: as escolas e a nova aliança conservadora. In: Currículo sem Fronteiras, online, v. 2, n. 1, p. 55-78, jan.-jun., 2002. Disponível em: <http://www.curriculosemfronteiras.org/vol2iss1articles/apple.pdf>. Acesso em: 16 de junho de 2018. [ Links ]

BOBBIO, Norberto. Direita e Esquerda: razões e significados de uma distinção política. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 2011. [ Links ]

BOITO Jr., Armando. Os Atores e o Enredo da Crise Política. In: SINGER, André [et al.]. Por Que Gritamos Golpe?: para entender o impeachment e a crise política no Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2016. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. O Senso Prático. Rio de janeiro: Vozes, 2011. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Fabiana Aparecida de; POLIZEL, Alexandre Luiz; MAIO, Eliane Rose. Uma Escola Sem Partido: discursividade, currículos e movimentos sociais. Semina: ciências humanas e sociais, Londrina, v. 37, n. 2, p. 193-210, jul.-dez. 2016. [ Links ]

CÉSAR, Maria Rita de Assis; DUARTE, André de Macedo. Governamento e pânico moral: corpo, gênero e diversidade sexual em tempos sombrios. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 66, p. 141-155, out.-dez. 2017. [ Links ]

CHAUÍ, Marilena. A Nova Classe Trabalhadora Brasileira e a Ascensão do Conservadorismo. In: SINGER, André [et al.]. Por que Gritamos Golpe?: para entender o impeachment e a crise política no Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2016. [ Links ]

CIAVATTA, Maria. Apresentação: resistindo aos dogmas do autoritarismo. IN: FRIGOTTO, Gaudêncio (Org.). Escola "Sem" Partido: Esfinge que ameaça a educação e a sociedade brasileira. Rio de janeiro: UERJ; LPP, 2017. [ Links ]

DIP, Andrea. Em Nome de Quem?: a bancada evangélica e seu projeto de poder. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2018. [ Links ]

ESPINOZA, Betty Solano; QUEIROZ, Felipe Campanuci. Breve Análise Sobre as Redes do Escola Sem Partido. IN: FRIGOTTO, Gaudêncio (Org.). Escola "Sem" Partido: esfinge que ameaça a educação e a sociedade brasileira. Rio de janeiro: UERJ; LPP, 2017. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Florestan. Problemas de Conceituação das Classes Sociais na América Latina. IN: ZENTENO, Raúl. As Classes Sociais na América Latina: problemas de conceituação. Rio de janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1977. [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, Gaudêncio (Org.). Escola "Sem" Partido: esfinge que ameaça a educação e a sociedade brasileira. Rio de janeiro: UERJ; LPP, 2017. [ Links ]

GUILHERME, Alexandre; PICOLI, Bruno. Escola Sem Partido - elementos totalitários em uma democracia moderna: uma reflexão a partir de Arendt. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 23, p. 01-23, 2018. [ Links ]

HOLANDA, Sérgio Buarque de. Raízes do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2004. [ Links ]

KAYSEL, André. Regressando ao Regresso Elementos Para Uma Genealogia das Direitas Brasileiras. In: CRUZ, Sebastião Velasco; KAYSEL, André; CODAS, Gustavo (Org.). Direita, Volver!: o retorno da direita e o ciclo político brasileiro. São Paulo: Fundação Perseu Abramo, 2015. [ Links ]

LAZEGA, Emmanuel; HIGGINS, Silvio Salej. Redes Sociais e Estruturas Relacionais. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2014. [ Links ]

LEMIEUX, Vincent; OUIMET, Mathieu. Análise Estrutural das Redes Sociais. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 2008. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. As Demandas Conservadoras do Movimento Escola Sem Partido e a Base Nacional Curricular Comum. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 507-524, abr.-jun., 2017. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. Repolitizar o Social e Tomar de Volta a Liberdade. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 34, p. 01-15, 2018. [ Links ]

MANNHEIM, Karl. O Pensamento Conservador. In: MARTINS, José de Souza (Org.). Introdução Crítica à Sociologia Rural. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1986. [ Links ]

MANNHEIM, Karl. Ideologia e Utopia: introdução à sociologia do conhecimento. Porto Alegre: Globo, 1952. [ Links ]

MILLS, Wright. Power, Politics & People: the collected essays of C. Wright Mills. Nova York: Oxford University, 1963. [ Links ]

MOURA, Fernanda Pereira de; SALLES, Diogo da Costa. O Escola Sem Partido e o Ódio aos Professores Que Formam Crianças (Des)Viadas. Periódicus, Salvador, n. 9, v. 1, p. 136-160, maio-out., 2018. [ Links ]

NAGIB, Miguel. Professor Não Tem Direito de 'Fazer A Cabeça' de Aluno. Consultor Jurídico, São Paulo, 03 de outubro de 2013. Disponível em: <https://www.conjur.com.br/2013-out-03/miguel-nagib-professor-nao-direito-cabeca-aluno> Acesso em: 19 jun. 2018. [ Links ]

NETO, Luiz Bezerra; SANTOS, Flávio Reis dos. Agosto de 2016: a verdadeira face do golpe de Estado no Brasil. In: LUCENA, Carlos; PREVITALI, Fabiane Santana; LUCENA, Lurdes. A Crise da Democracia Brasileira. Uberlândia: Navegando Publicações, 2017. [ Links ]

NISBET, Robert. Conservadorismo e Sociologia. In: MARTINS, José de Souza (Org.) Introdução Crítica à Sociologia Rural. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1986. [ Links ]

PENNA, Fernando Araujo. O Escola Sem Partido Como Chave de Leitura do Fenômeno Educacional. In: FRIGOTTO, Gaudêncio (Org.). Escola "Sem" Partido: esfinge que ameaça a educação e a sociedade brasileira. Rio de janeiro: UERJ; LPP, 2017. [ Links ]

PENNA, Fernando Araujo. O Discurso Reacionário de Defesa de Uma "Escola Sem Partido". In: SOLANO, Esther (Org.)., O Ódio Como Política: a reinvenção das direitas no Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2018. P. 109-113. [ Links ]

PENNA, Fernando Araujo. Programa "Escola sem Partido": uma ameaça à educação emancipadora. In: GABRIEL, Carmen; MONTEIRO, Ana; MARTINS, Marcus (Org.)., Narrativas do Rio de Janeiro nas Aulas de História. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad, 2016. P. 43-58. [ Links ]

PILCHER, Jane. Mannheim's Sociology of Generations: an undervalued legacy. The British Journal of Sociology, Londres, v. 45, n. 3, p. 481-495, 1994. [ Links ]

RECUERO, Raquel. Redes Sociais na Internet. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2014. [ Links ]

RECUERO, Raquel; BASTOS, Marcos; ZAGO, Gabriela. Análise de Redes para Mídia Social. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2015. [ Links ]

ROMANCINI, Richard. "Vamos Tirar a Educação do Vermelho": o Escola Sem Partido nas redes digitais. Revista da Associação Nacional dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação/E-compós, Brasília, v. 21, n. 1, jan.-abr. 2018. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Demerval. A Crise Política no Brasil, o Golpe e o Papel da Educação na Resistência e na Transformação. In: LUCENA, Carlos; PREVITALI, Fabiane Santana; LUCENA, Lurdes. A Crise da Democracia Brasileira. Uberlândia: Navegando Publicações, 2017. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, Sergio Amadeu. Direita nas Redes Sociais Online. In: CRUZ, Sebastião Velasco; KAYSEL, André; CODAS, Gustavo (Org.). Direita, Volver!: o retorno da direita e o ciclo político brasileiro. S.l.: FPA, 2015. [ Links ]

SINGER, André. Os Sentidos do Lulismo: reforma gradual e pacto conservador. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2012. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Jessé. A Tolice da Inteligência Brasileira: como o país se deixa manipular pela elite. São Paulo: Leya, 2015. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Jessé. A Ralé Brasileira: quem é e como vive. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2016. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Jessé. A Elite do Atraso: da escravidão à Lava Jato. Rio de Janeiro: Leya, 2017. [ Links ]

ZUIN, Vânia Gomes; ZUIN, Antônio Álvaro Soares. A formação no tempo e no espaço na internet das coisas. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 37, n. 136, p. 757-773, jul.-set., 2016. [ Links ]

Received: June 20, 2018; Accepted: April 25, 2019

texto en

texto en