Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Realidade

versão impressa ISSN 0100-3143versão On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.44 no.4 Porto Alegre 2019 Epub 14-Nov-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623686743

OTHER THEMES

Research with Art: ethics and aesthetics of the existence

IUniversidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), Florianópolis/SC - Brazil

The objective of this paper is to affirm the potential of art as a means for academic research capable of propitiating broad modes of thinking and of action, conceiving creation and experience as central elements of the investigative process. The paper revisits the work of some authors of the methodology known as Arts-Based Research, emphasizing the contribution of the challenges raised by Jan Jagodzinski and Jason Wallin. It understands research with art as a dispositif for ontological actions: the composition of an aesthetic of the existence (Foucault) and of a become-art (Deleuze). The paper presents the strength of the poetic act to make possible an enlarged conception of research, an education as educere and a humanity to come.

Keywords: Research; Art; Education; Aesthetics of Existence

O presente artigo visa a afirmar o potencial da arte enquanto uma via de pesquisa acadêmica capaz de propiciar modos alargados de pensamento e de ação, concebendo a criação e a experiência como elementos centrais do processo investigativo. O artigo revisita a obra de alguns autores da metodologia conhecida como Pesquisa Baseada em Arte, enfatizando a contribuição dos desafios colocados por Jan Jagodzinski e Jason Wallin. Entende a pesquisa com a arte como um dispositivo de ações ontológicas: a composição de uma estética da existência (Foucault) e de um devir-arte (Deleuze). O artigo apresenta a força do ato poético de possibilitar uma compreensão alargada de pesquisa, uma educação enquanto educere e uma humanidade por-vir.

Palavras-chave: Pesquisa; Arte; Educação; Estética da Existência

Arrival: the power of art in the research

The present article intends to signal and affirm the potential of art as a way for academic research. It rises from the demands which have appeared in the academic and educational contexts in the last decades; demands for production, for deepening and legitimation of forms of research that, by using artistic languages, provide to reach potentialities which would remain invisible with other forms of investigation. The artistic procedures of research, by conceiving creation and experience as central elements of the investigative process, can provide multiple ways to perspective, since their complexity, the subjects, actions and the researched fields, considering their subtleties and specificities, providing a cross of horizons and a wider comprehension of what research may mean.

Further than trying to confer epistemological legitimacy to the research with art, I aim in this article to present it as an event of ontological immanence, which, by producing alternative manners of being in this world, inaugurates powers of life and creation. I bet on the construction of investigative paths that can problematize the manner with which we see, think, and live; and that can surpass the ordinary and institutional ways of addressing the world, unleashing poetical experiences, aesthetics of the existence (Foucault, 1995) and processes of becoming-art.

We find already in Friedrich Nietzsche´s work the invitation to make our lives our artwork. For this philosopher, art is a practice imbued with an ethical sense, which allows us to construe ourselves as an artwork, because “[…] we want to be the poets-authors of our lives, especially in the smallest and daily things” (Nietzsche, 2012, p. 179), creating meanings for our existence.

As an æsthetic phenomenon existence is still endurable to us; and by Art, eye and hand and above all the good conscience are given to us, to be able to make such a phenomenon out of ourselves. We must rest from ourselves occasionally by contemplating and looking down upon ourselves, and by laughing or weeping over ourselves from an artistic remoteness: [...] we need all arrogant, soaring, dancing, mocking, childish and blessed Art, in order not to lose the free dominion over things which our ideal demands of us [...] (Nietzsche, 2012, p. 179).

Michel Foucault takes further the Nitzschean conception of life as artwork, proposing an aesthetics of existence:

What surprises me, in our society, is that art relates only to objects and not to individuals or to life; and also, that is a specialized dominion, a dominion of experts, which are the artists. But couldn´t be the life of every individual a work of art? Why is a table or a chair an art object, but our lives are not? (Foucault, 1995, p. 261).

The aesthetics of existence consists in the development of practices that have life itself as an object, in the creation of a wisdom of living life in the most beautiful and ethical way possible, and to therefore transform the world. They are practices of transforming ourselves in the architects of our conduct, in a political exercise of creation of non-subjectified or subjectifying subjectivation processes. They are non-dogmatic ways of thinking that, playing with possible liberties, invent new senses.

I bet on the challenge of bringing to research and education, the potency that art has to cross the boundaries which curtail thought, feeling and creation, of dislodging perspectives conditioned by hegemonic discourse and “liberate life, wherever it is prisoner” (Deleuze, 1992). There are experiences that can only be sighted, experienced, initiated and shared by the poetic act. The poetic gesture is of a nature other than the ordinary and the scientific. What differentiates poetic language from the ordinary may be the fact that “the first, more than being a metaphorical language, has the power to metaphorically create language” (Cometti, 2000, p. 12).

Poetry is one of the destinies of speech, [...] where we touch the man of the new word, a word that it is not limited to expressing ideas or sensations, but tries to have a future. One would say that the poetic image, in its newness, opens a future to language (Bachelard, 2009, p. 3).

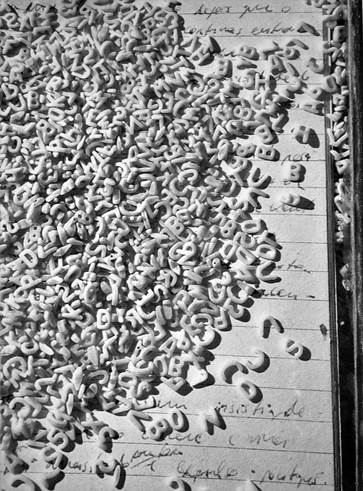

Source: Photo by Paulo Gaiad (2002), published in Lima e Gaiad (2010)

Figure 1: Receptacle of the memory of Renato Tapado

In the artistic experience, the relation established with language is of another nature. It does not happen when we traverse the symbol to reach directly what it refers to, as when we read a scientific text.

Unlike the scientific method, in which the epistemological priori exerts control over the object and the validity of the experiment, the artist plays with chance and imagination when apprehending his/her objects. By being nourished by the playful actions suggested by the experiment, the inflections of meaning take on a great significance to the creative process. Rather than aiming at conclusions, the artist’s process sticks to the experience itself (Vinhosa, 2011, p. 43).

Art also thinks, and the artistic thought escapes doxa, it takes place by paradoxes, by leaps; it is not located between oppositions, but speaks from these very places - it inhabits simultaneously, and in a singular manner, our infinite dimension as well as our historical dimension. Art creates other possibilities of thinking, of perception, of sensibility, of life. It creates a becoming, a people-to-come. For Deleuze (Deleuze; Parnet, 2004 p.41) “in the becoming there is no past nor future, not even present, there is no History”. The becoming is not a time, it is a between-times. An intensity that coexists with the instant, “an immensity where nothing happens, but everything becomes” (Deleuze; Guattari, 1992, p 204). In the Deleuzian conception, art thinking happens as an event.

The event is not the state of affairs. It is actualized in a state of affairs, in a body, in a lived, but it has a shadowy and secret part that is continually subtracted from or added to its actualization: in contrast with the state of affairs, it neither begins nor ends but has gained or kept the infinite movement to which it gives consistency. (Deleuze; Guattari, 1992, p. 202).

The artistic investigation methodologies, in this sense, try to propitiate expanded modes of touching, imagining, thinking and signifying the research, in the many fields of academic knowledge. They try to establish dances among researchers and their respective fields, inventive relations, unforeseeable movements, approaching and distancing subjects and objects, creating opportunities for different views, back and reverse which poeticize the research process, coloring with many hues and Matisses13 the construction and deconstruction of knowledge, updating possibilities of perception and acting, invisible to the ordinary eye. Their practices, empirical as well as theoretical, visit and recreate through the artistic act the dimensions of the human, of the inhuman, of the incompleteness and of the incertitude. To the researcher-artist, this investigation is inherent to the tension and incompleteness which constitute art, for he attempts to impregnate these poetic and plural experiments with the power of life rather than solve, answer or complete. The artistic languages also make possible to visit the relevant dimensions of the unconscious, the landscapes of the imagination and some of the most significant questions about human existence, contributing, therefore to a widening of the concept of what may be the activity of researching.

The use of artistic procedures as a way of creating, thinking, knowing and accessing worlds is not something new, and it happens throughout history, as we know, following, permeating and producing the construction of knowledge and of humanity itself. However, art as an instrument, respected, accepted and appreciated by academic research (in many fields of knowledge) is something still rather recent; this is a question which has been debated, refined and strengthened by many scholars since the last decades of the XXth. century.

A long movement of philosophers and artists has converged in order that art may perform today a relevant role in contemporary thinking. Art today is acknowledged as a field of knowledge, a ground of experimentation and problematization of the present, and of the transformation of the human. Among other spheres of human activity, art:

[…] in their distinctive manifestations, is neither colluding with the present state of things, nor accepts being a mere companion, superfluous and disposable, though enjoyable, of the decisive events of the crisis of the urban and industrial civilization. Working with languages which span the entire social field, art may be, nowadays, the most powerful inscribing gesture in the initiating of another time and another historical space in the body of relations between human beings, beyond national boundaries and all sorts of prejudices (Basbaum, 2007, p. 9).

The research with art, in the academic context, appears among several attempts to update these other times and spaces, of these other regards and modes of research in the human field. The potentialities of art may bring innovations to the investigative methodologies, for the symbolic language of art suggests, not affirms. If scientific thinking, in the positivistic concept, searches for definitive and final answers, if it tries to know the truth, the artistic research, by not orienting itself on a quest for truth, propitiates the necessary modesty needed for the opening of other perspectives which escape the control and the reproduction of an univocal and dominant way of thinking.

The question of truth has been discussed by many thinkers and problematized, especially from Nietzsche onward. This philosopher severely criticized the notion of an absolute truth formulated by Plato, he upheld the relativity of knowledge, its historical character, its anthropomorphism and its power of illusion. According to Nietzsche (2005, p.16) “[...] everything has become: there are no eternal facts, just as there are no eternal truths”. Nietzsche (1974) proposed a “transvaluation” of rational precepts and platonic ideals, and of the concept of truth as a superior metaphysical value, as an essence. The platonic truth would have a moralistic, excluding, imprisoning character. What was considered true could not be questioned, refuted or transformed, creating a dogmatic position, stifling thought as a creation process. Such truth would be, in the Nietzschean perspective, illusory, for knowledge is always a human construction, too human; the conditions that allow for knowledge are circumstantial, social and political. For Nietzsche (2005), the illusion of a metaphysical truth is naïve, on the other hand the artistic illusion is a critical illusion, for, not presenting any commitment to truth, it assumes itself as illusion, phantasy, imagination.

Knowledge constructed by art is acutely aware of its own openness, to its own susceptibility to be affected by the ripples of the terrain on which it builds its paths, its passages, its intervals. The concept of cognition is expanded by creation (Kastrup, 2007), which confers it dynamism, problematizes what is already established, enlarges, surprises, folds, refolds and unfolds realities.

It is true that, also in contemporary science, we find knowledge fertilized by creation. The importance of the role of creation in cognition was researched in the Physics studies by Ilya Prigogine who, while investigating certain dimensions of reality ignored by modern science, found a Nature able to create active and proliferating structures (Kastrup, 2007). The boundaries between art, philosophy and science are flexible and porous. They can differ relative to the kinds of phenomena, which each one is capable of bringing to light, since the different perspectives, languages, methods and paths that they create and build.

Maurice Blanchot (2010) highlights the fact that the objective of art is not to know the truth or represent reality. Art and poetry establish their own reality, their own world, their own space. Poetic language is different from ordinary language. Ordinary language is utilitarian, an instrument that refers to the external world, aiming to establish a relationship between the receptor and the evoked object by means of the word or the image. Poetic language, in the Blanchotian conception, constitutes its own universe as fiction. It does not represent something existent, but creates, presents an object. It is precisely by its poetic usage that language reveals its essence: the power to create, to establish a world.

Artistic creation can thus be one of the “[…] most powerful critical instruments at our disposal today to see beyond boundaries, to think and transform the way in which contemporary societies constitute themselves, reproduce themselves and keep themselves” (Machado, 2004, p. 6). In this sense, poetical experimentation has a strong political character: it metamorphoses that which did not fit in the places of culture, it opens cracks in the closed field of common sense as well as in education itself, enabling us to create unprecedented views and play with the events to turn them into opportunities.

For Michel de Certeau, the political character of art makes itself evident in its potential to create deviationist perspectives, that although they may be within a context of domination, they do not obey the local laws, for they are not defined by that context. An action which “[…] without leaving the place where it has to live, and which imposes a law, establishes plurality and creativity there. By an art of intermediation, derives the unexpected from it” (Certeau, 2013, p. 87). A necessary action for an education understood as educere, which leads us outside from the standardized discourses and the limitations that reduce our power of thinking and acting. A necessary action to face the constriction instilled by the monosyllabic technical discourse of the globalized neoliberalism.

The power of creating other ways of living and other possibilities of worlds is extremely important, given the contemporary context where, dragged by the globalized capitalism we are approaching the possibility of the collapse of humanity. Among other things, we are destroying natural resources that are indispensable to our survival; there is a considerable increase in social inequality; the consumerist way of life is homogenizing the individualities, capturing he proliferation of possible worlds and turning them into merchandise, manipulating the aspirations of populations, dismantling the cooperation between subjectivities, creating in this manner a network of surveillance, control and discipline (Foucault, 1987), spreading nihilism and conformism. In face of the disenchantment and the disgust (Perniola, 2010), which often contaminates part of the academic and school environments, fading their colors and painting many life perspectives of present and future generations in bleak apocalyptic colors, which other ways of living together, of producing solidarities and affections, what qualities of experience, attention and presence, what educational and investigative practices can we make effective, in the sense of fostering a belief in the possibility of a world?

Taking inspiration in Deleuze (2013, p. 207) I consider that, if “the link between man and the world is broken, restore this link is an ethical question par excellence” and a pressing need for education and research.

Arts-Based Research

From the last decades of the XXth century onward, some researchers, with the intent of appreciating, validating and deepening the comprehension of art as an instrument of academic research, have worked on the conception of the methodology known as Arts-Based Research, (ABR). This methodology proposes research paths that constitute themselves through artistic processes, from the approach to the investigated fields until the presentation form and the writing of the final versions. They are proposals that shift the established ways of researching, with the purpose of transforming what is prosaic in poetical, emphasizing vivification instead of infallibility and singularity instead of universality (Lather, 2009). The ABR, according to its authors, could be accomplished both in the education, arts and human sciences areas and in other areas of knowledge.

Some of the authors who have created, thought, systematized and developed modes of Art Based Research are: Elliot Eisner, Tom Barone, Lawrence-Lightfoot, J.H. Davis, Graeme Sullivan, Richard Siegesmond, the group of researchers A/r/tografy, Ricardo Viadel, Fernando Hernández, Jason Wallin and Jan Jagodzinski, whom I especially highlight in this article.

In Brazil, the discussions and debates about ABR are still in the initial phase. From the academic works already available, I point out the interesting and consistent PhD thesis by Dr. Sonia Tramujas Vasconcellos (2015), titled Entre (dobras): lugares da pesquisa na formação de professores de artes visuais e as contribuições da pesquisa baseada em arte na educação (Between foldings: places of research in the education of visual arts teachers and the contributions of arts-based research in education) and the book Pesquisa Educacional Baseada em Arte: A/r/tografia (Art-Based Educational Research: A/ r/tografy) (Dias; Irwin, 2013), organized by Belidson Dias and Rita Irwin, and which includes articles by Brazilian authors and by authors of many other nationalities. There are few published articles about artistic research methodologies, among them: two by Marilda Oliveira de Oliveira, Contribuições da perspectiva metodológica ‘Investigação Baseada nas Artes’ e da A/r/tografia para as pesquisas em Educação(Contributions to the methodological perspective ‘Arts Based Investigation’ and of A/r/tography to the research in Education) and Como ‘produzir clarões’ nas pesquisas em educação(How to ‘produce flashes’ in Education research) presented respectively in the 2013 and 2015 ANPEDs; the essay by Sonia Tramujas Vasconcellos and Tania Baibich A Pesquisa Baseada em Artes Visuais na Educação: novos modos de investigar e conhecer (Visual Arts Based Research in Education: new ways of investigating and knowing); another article by Belidson Dias Preliminares: A/r/tografia como metodologia e pedagogia em artes (2009) (Preliminaries: A/r/tography as methodology and pedagogy in art); and essays by Luciana Gruppelli Loponte (2008, 2018), Cristian Mossi (2015), Irene Tourinho (2013), Sandra Rey (1995, 2010), Maria Cristina Pessi (2009), Miriam Celeste Martins (2011), among others.

The 24th Encontro Nacional da ANPAP, Associação Nacional de Pesquisadores em Artes Plásticas, held in Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, em 2015, had one symposium (number 8) called Pesquisa em Educação e Metodologias Artísticas: Entre fronteiras, conexões e compartilhamentos (Research in Education and Artistic Methodologies: Between boundaries, connections and sharing). This symposium, coordinated by Professors Miriam Celeste Martins, Sonia Tramujas Vasconcellos and Marilda Oliveira de Oliveira, and with participation of 16 attendees, brought important contributions to the deepening and discussion about this subject14.

But let us go back to Jagodzinski. This professor and researcher from the University of Alberta in Canada, author of an extensive body of work about art, education, research and media, wrote, in partnership with Jason Wallin, the beautiful book Arts-Based Research: A Critical and a Proposal (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013). I found this book on the virtual pages of the Internet, when carrying out my theoretical-bibliographical research about the subject. I had already read, then, some articles by Eisner, Hernandez, Belidson Dias, Marilda de Oliveira, Irwin, Springgay e Viadel. I was questioning some of the assumptions in the theories of Eisner and others who based their thought on his work, such as: of an a priori existing subject, the conception of art as representation, the epistemological character of the ABR, assumptions which seemed naturalized, not called into question, assumptions taken as a “not thought-out truth, but which operate as a principle of thought” (Kohan, 2007, p.20). I found then, in the works by Jagodzinski e Wallin, elements of analysis, criticism and even incision in these questions, which allowed an expansion of my reflections, and the creation of deviant perspectives of thinking the diverse modes of artistic research.

Contributions by Eisner and Barone

Elliot Eisner is regarded by some authors as the researcher who has initially systematized the investigative methods through artistic language. The designation Arts-Based Research, according to Eisner e Barone (2012), would have been created by Eisner himself in 1993, while teaching a course on forms of education and research based on aesthetic concepts at the University of Stanford, where he was a professor. In the 1970s, Eisner perceived the investigative potential of art in the academic environment and supported it in some of his books, such as The Educational Imagination (Eisner, 1979) and in articles as What education can learn from the arts about the practice of education de 2002, published in Brazil in 2008 (Eisner, 2008, p. 5-17).

Eisner was an important theorist in the Art-Education field. His thought contributed during decades to the improvement of the Teaching of Art, to the achievement and maintenance of the place of art in the school curricula, and to the appreciation of the role of art in the development of aesthetic skills and of critical thought, both in the American context and in several countries around the world, including Brazil. We worked enthusiastically on this until his death in 2014.

Eisner and Barone wrote the book Arts Based Research (Barone; Eisner, 2012), the result of decades of research and experimentation about what might be an Art Based Research (ABR) and about the several possibilities of working with it. In the aforementioned book Eisner and Barone raise, problematize and discuss several questions pertinent to ABR, demonstrating how and why this kind of research can be in fact reliable. The main goal that generates all these reflections is essentially the attempt to confer epistemological legitimacy to the Arts Based Research, especially in the academic environment, where a consensus that scientific thought is the only valid instrument of research and knowledge building still prevails. It is not an aspiration of the authors that the diverse forms of ABR replace the conventional methods of empiric research, nor that they are conceived only as a supplement, something to be added to scientific research (Barone; Eisner, 2012, p. 4). Inspired by John Dewey (2010) these authors advocate that knowledge derives from experience, taking as an examplary experience, the artistic one.

Eisner and Barone regard ABR as a qualitative research which, through artistic procedure - literary, visual, musical and performing - aims to enable the investigator, the reader, the collaborator, experiences and ways to interpret these experiences, which unveil aspects that would not be visible in other kinds of research. For these authors, ABR draws closer to Participating Research and Action Research, in the sense that it has an interventionist character, in which both the investigative profile and the researcher himself construct themselves during the process of research. The authors understand the ethical role of the ABR as a potential for elaboration of processes that promote the transformation of the researcher himself, of a problematization of institutional assumptions and of the transformation of public policies that systematize them.

For Eisner and Barone, ABR is “[…] an effort to utilize the forms of thinking and representation that art provides as means through which the world can be better understood and trough such understanding comes the enlargement of mind”. (Barone; Eisner, 2012, p. xi). ABR may provide a greater diversity of perspectives about the investigated fields. For these researchers, one of the essential qualities of ABR is the use of varied forms of representation to promote an increased depth and complexity in the understanding of the human being. Some representations may be discursive and digital, others analogic; others figurative, musical, of gesture. These forms, which are never redundant, would allow different modes of comprehension for the diverse aspects of the study fields. “It is the plurality of view that we seek in a long run, rather than a monotheistic approach to the conduct of research” (Barone; Eisner, 2012, p. 10).

According to Eisner and Baron, we confer sense to the world, working with forms of representation. The different languages delineate different modes of expression, merge the world in different manners, and merge different worlds. This suggests that the concept of literacy may have to be expanded. For the authors, poetry and literature are clear examples of how we may work with the languages in order to produce senses that in any other way would be inexpressible, thus promoting powerful perspectives about our world. Artistic/poetic language cannot be measure, scrutinized or framed, just as life itself, which does not happen in this manner.

To execute an ABR, according to Eisner and Barone, although a researcher may not need to be an art professional, he must at least demonstrate familiarity with the artistic language of choice, propitiating the creation of an aesthetic sense from the chosen subject. The authors suggest that academic research programs in the many social and human research fields could be designed to make feasible art-based research projects, offering opportunities for future researchers to develop skills in many artistic languages, such as drawing, painting, sculpture, music, theater, performance, as well as in the making of videos, films, photography, animations, relational art, installations etc.

In the wake of Maxine Greene (1995) and Herbert Read (2001), Eisner and Barone emphasize that the aesthetic experience makes possible a “high level of conscience” about what one sees and what one experiences. It is this amplified quality of perception and fruition, this fullness of attention and of empathy that educators and researchers can learn from art (Barone; Eisner, 2012).

In an ABR, it is the artistic content that structures and leads all research. The artistic language in this context is not used as an ornament of a scientifically produced work, but is the essential form of construction, and it will detemine what and how it will communicate, and the manner how it affects the work’s reception. Truly effective methods in ABR are recognized by the questions they raise, that is, not by delivering and answer or a correct solution to a problem, but by creating questions which stimulate new formulations and attitudes.

For the authors, the political character of a ABR may be built in two basic forms: the first would be the development of themes which suggest the manner in which power and privilege are distributed, or badly distributed, in specific cultural niches (Barone; Eisner, 2012); the second, in the construction of the democratic character of the research, in order to allow diverse points of view to be adequately considered.

Eisner e Barone highlight that ABRs can revisit the world with a fresh outlook, establishing ways of researching which cater to a basic human necessity, “a need for surprise, for the kind of re-creation that follows from openness to the possibilities of alternative perspectives on the world” (Barone; Eisner, 2012, p.124). The researcher tries to position himself not as the owner of the research, but creating a polyphonic text, in the Bakhtinian sense of the word, which weaves together a multiplicity of perspectives, and which belongs simultaneously to all of them.

Taking Eisner’s and Barone’s proposal further

Eisner’s and Barone’s contribution to the ABR is quite valuable, and it is up to us researchers who are interested in this subject to take further the journey proposed by them. It seems to me important to abandon postures tied to modern epistemological representations and to concepts of subject founded on a transcendence and inwardness already separated from the world considered external. Although Eisner and Barone assert that the ABR perspective questions the “great modern narratives” (Lyotard, 2011)15, when they propose a conception of art as representation, of an epistemological and subjective character - modern precepts - ultimately they let escape, in my opinion, the deviant force of the ABR of creating new worlds, which I consider its main contribution to the present contemporary moment.

We find the unfoldings of these questionings in the work of Jagodzinski and Wallin, as we’ll see next. The latter comment that Eisner’s proposals are important and pertinent, but his theoretical and philosophical bases are not radical enough to take them far enough up to where they propose to go. They underline that, to further the creative power that supports this investigative type in a more effective manner, it is necessary to destabilize our usual perceptions and assumptions, in a profound work of questioning of ourselves and of established truths, as the micropolitics of becoming proposed by Deleuze. For Jagodzinski and Wallin it is exactly this stance - be open to what still is not, to what we still do not know, to what we still are not, enabling the potential of a poetic creation of a future - that constitutes the power of the ABR. Otherwise, they alert, instead of “liberating life where it is a prisoner”, ABR will end up “repeating a subjectivity that serves current neo-liberalism and capitalist ends” (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013, p.3).

The Ethics of Betrayal in Jagodzinski and Wallin

The book Arts-Based Research, a critique and a proposal (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013) is a work of great philosophical density, where the authors, aside from expressing criticism about some of the references that support Arts Based Research, bring proposals and provocations, trying to contribute to an expansion of its potentialities. The authors pose the question: what is after all the relationship between art and research? They work out in this sense a crossover of ABR and the philosophical perspectives of Deleuze and Guattari (1992), for whom an ethical and political commitment requires a conception of art in a lesser degree as an object and greater as an event. For Deleuze and Guattari (1992), art is much more than an object to be read, it is a composition of affects and percepts, a pre-subjective liberating force that overflows both the artist and the spectator. The researcher as well as the reader.

Jagodzinski and Wallin conceive an Arts-Based Research of a prevalent political character. They analyze some of the ways in which they understand that some of the forms of ABR are being co-opted by capitalist interests and assert the necessity to think it and constitute it as a practice of destabilizing the common sense and the prevailing discourses. Artistic research would be rather an invention than a discovery.

The authors understand ABR as a device able to potentialize an Ethics of Betrayal (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013) - the creation of deviant and perturbing actions which resist, problematize, destabilize and displace the standardizing mentality of the contemporary hegemonic cultural assumptions. A “performative/machinic” action which creates other realities that may escape the productivist logic of the modern power which the designer capitalism16 brings into play. (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013, p. 3). Their central focus is not about what art is, but what it can do: deviate the path of thought of the representational sameness, from consumerism and from hegemonic mediatic appeals of the neoliberalism. This hegemony, according to Deleuze and Guattari (1995), is exerted by the control society, where the movements and space are choreographed in ways specifically known beforehand, oriented by capitalistic ends. In the same manner, according to Jagodzinski and Wallin, creativity would now be theorized as a mix of art, science and ingenuity determining education rationalities tied to entrepreneurship and to the formation of flexible and creative workers for the industries. These are the forms, according to the authors, that must be betrayed.

For them, it is not surprising that ABR and Visual Culture have had such an increase in popularity in the last decades, since we presently live in a culture of the image and consumption´s standardizing discourse rests upon the image, our outlook having been substantially rooted by the publicity industry’s aesthetics. Jagodzinski and Wallin emphasize the importance of the creation of signs which defy the images of thought. In Deleuzian terms, the image of thought refers to a dogmatic form of thought, a singular form of territorialisation, which effectively makes people stop thinking. Art has, for Deleuze, a secret pressure that shakes thought:

What forces us to think is the sign. The sign is the object of an encounter, but it is precisely the contingency of the encounter that guarantees the necessity of what it leads us to think. The act of thinking does not proceed from a simple natural possibility; on the contrary, it is the only true creation. Creation is the genesis of the act of thinking within thought itself. This genesis implicates something that does violence to thought, which wrests it from its natural stupor and its merely abstract possibilities. [...]. The signs of art force us to think, [...] mobilize, constrain a faculty: intelligence, memory or imagination. [...]. The sensuous sign does us violence [...] excites thought, transmits to it the constraint of sensibility [...] (Deleuze, 2010, p. 91-94).

An approach to sign different from the classical approach: not as a guardian of meaning, “a guardian of the place belonging to a momentarily absent proprietor” (Silva, 2002, p. 50), but as something that represents nothing nor nobody. The poetic sign is launched by the other - something that was not thought out yet - is always a sign that comes from the outside, as Maurice Blanchot suggested. According to Blanchot, poetry escapes the “primacy of the I-Subject”, for, living poetically “is necessarily living ahead of oneself” (Blanchot, 2010, p. 34), is being open to the encounter, when the “Other, emerging unexpectedly, compels thought to come out of itself, as well as compels the I do confront the fault that constitutes it and from which it protects itself” (Blanchot, 2010, p. 39). The outside is this other in the world who is unfolded by art. Poetry, for the French author “appears as a means to a discovery and to an effort, not to express what we know, but to feel what we don’t know” (Blanchot, 2010, p. 39). To live poetically is to live in the face of the unknown:

[...] it is entering this responsibility of speech that speaks without exerting any form of power, including this power which takes place when we look, since by looking we keep under our horizon and inside our circle of vision -in the visible-invisible dimension - what and whom which is before us (Blanchot, 2010, p. 35).

Art, reasserts Blanchot, is not mere phantasy; it is real, because it is effective. “Art is real in the work. The work is real in the world, because it is done there, because it helps its realization and it will only make sense in the world where man will be par excellence” (Blanchot, 1987, p. 212- 213). The artwork is where the human being is free to begin anew, to the possibility of being open and naked before the abyss of the world, able to build another world.

Once the images and signs of common sense have become at present a domain of marketing, and are disseminated both in the cognitive models of a great part of the people, and in the educational practices, it is imperative that we question the representational fidelity with which they operate. Jagodzinski and Wallin assume that a sign must be defined in opposition to common sense and to accommodation of thought, destabilizing the model of recognition and its stable correspondences which numb creation. The authors emphasize the necessity of a research and an education that force us

[…] to assault a kind of lethargy through which the signs are already distributed in a semiotic field. Nevertheless, this representative fidelity does not realize an encounter with the thinking, even less a form of education (educere) able to ‘bring out’; neither it propitiates the creation of a pedagogical encounter with a thought of the outside, which could force us to think again. Maybe this is themost singular contribution of art to education, in so far as it demands from teaching and learning something radically different from the voluntary movement of memory (reflection), from the application of representational matrixes (transcendence) or from the deployment of laws known prior to the object to which they apply (morality). […]. This is the beginning of an ethics of betrayal (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013, p. 5).

The neoliberal globalization demands a technicist ordination of the educational curriculum in order to implement the formation of obedient, non-questioning consumers and laborers. For Jagodzinski and Wallin, the capitalist marketing strategies have also captured our protests and demands for a difference, adopting an approach of super-individualized colonizing of the eye, which appeals to an extreme narcissism. The information speed adds to the image speed, establishing new hieroglyphs and an aesthetics of the glance, the advertising industry captures, “in the blink of and eye” the consumer’s attention. Everything becomes merchandise in the sphere of designer capitalism. The marketing strategies have allied themselves to the biopower’s (Foucault, 1988), capturing the imagination and desire, and coupling them to the status conferred by consumerism. That is what is perceived by Jagodzinski and Wallin in movements like green capitalism or green consumerism, which absorbed a good part of the ecological discourses and protests turning them into merchandise.

For Jagodzinski and Wallin, Art Based Research is also a product of this zeitgeist (spirit of the times) of the image, at the risk of riding this wave of formatting the imagination and the cognitive brain of the people, turning them into the working masses which sustain the neoliberal empire. We live in an inverted form of a panopticon, that is, the authors suggest that we live in a synopticon, where the few are viewed by the many, who aspire to imitate them. Pornography is the leader of this genre of video, installing a perverse voyeurism. The avalanche of melodramatic or zombie- or vampire-based movies mesmerize the spectacle entertainment, which could suggest that we are going through a pos-emotional time, when “media and the screen relieve the subjects from their emotional projections” (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013, p. 21).

The video technologies create ambiguous messages affecting the spectator, bringing him/her some satisfaction, but leaving him/her somehow powerless. It is the power of a soft totalitarianism, where the technologies offer a sense of numbing and, in exchange capture our attention and our desires. The designer capitalism

[...] knows full well the game of affect. The pre-individuated realm of the unconscious raises all sorts of problematics for arts-based research that wishes to free itself of the capitalist lure. Perhaps it can’t. [...]. Capitalism in this sense is machinic, an alien monstrosity that sustains itself indefinitely through continuous cycles of deterritorialization and reterritorialization. Its animist agency is manifested through ecophagic practices, which harbour a freudian death drive to the point where everything will be used up, as our species is liquidated by its own narcissism (Jagodzinski; Wallin, 2013, p. 40).

Jagodzinski and Wallin propose Art Based Research as an event of ontological immanence, detonator of a process which enables seeing and thinking in a singular manner, which resists normalization and subordination to instituted modes of addressing the world. They propose forms of ABR which comprise tactics of de-sedimentation of the habits of reconnaissance, which Deleuze and Guattari call territory. Jagodzinski and Wallin bet on the deviant potency of simulacra, on the power of the false (Deleuze, 2013), which are immanent to the artistic process, to create vanishing point lines, escaping from the productivity logic of modern power, and propitiating new experiences and new forms of narrative.

It is a power of the false which replaces and supersedes the form of the true, because it poses the simultaneity of incompossible presents, or the coexistence of not-necessarily true pasts. […] every model of truth collapses in favour of the new narration (Deleuze, 2013, p. 160-161).

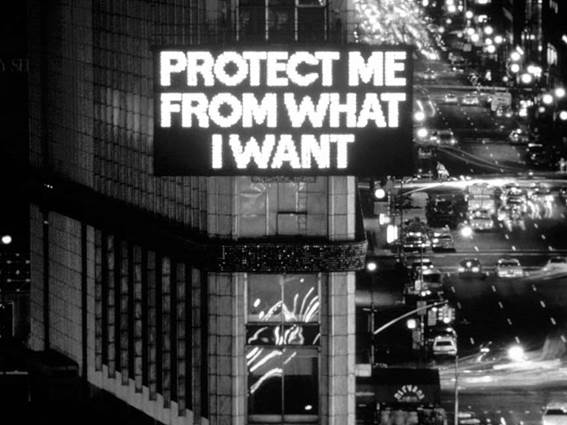

Source: Photo by Jenny Holzer. Installation in Times Square, NY (1985)18

Figure 4: Protect me from what I want

The authors suggest that as we progress in breaking the perceptive habits of common sense, we can work with the freedom and the power of art. The importance of art does not reside any longer in its form, but in its power. And its power is that of creation of an ethics of become that engenders a believing in a possibility of world, which uncouples, impregnates and liberates the potentialities of life. This believing assumes the shake-off of thought conventions, the creation of cracks, strangeness, an imperfect coincidence with our time. For, as Giorgio Agamben (2009, p. 73) alerts us, the possibility of establishing a singular relationship with our own time requires that we, on one hand draw nearer to it, on the other hand distance ourselves through dissociation and anachronism. “Those who coincide too well with the epoch, those who are perfectly tied to it in every aspect are not contemporaries, precisely because they do not manage to see it.” And much less to transform it... It is necessary not to allow ourselves to “be blinded by the lights of the century, and so manage to get a glimpse of the shadows in those lights, of their intimate obscurity” (Agamben, 2009, p. 64).

In order that life, research and education may be reconnected with their power of becoming, the dogmatic images of thought, preconceived by common sense must be doubly traversed. The first crossing would be made when we create strangeness, when we make the thought conventions stammer; the second when we make art assume its non-representational power, its monumental power as Deleuze and Guattari assert:

It is true that every work of art is a monument, but here the monument is not something commemorating a past, it is a block of present sensations that owe their preservation only to themselves and that provide the event with the compound that celebrates it. The monument’s action is not memory but fabulation (Deleuze; Guattari, 1992, p. 218).

Art based research can become a fabulation space of a yet-to-come people. Art mobilizes an irrational sparkle in time, establishing relationships between unseen powers and visible rhythms, untying the bounds of sensation and of what has not yet been thought and lived. Art operates therefore paradoxes, distancing itself from the doxa, from the templates, establishing new powers of believing in the possibility of a becoming of the world. We might say that art does not represent the world, but it becomes world. Just like it happens, as Jagodzinski and Wallin (2013) suggest, in Van Gogh’s art, who does not simply paint sunflowers, but becomes a sunflower.

Art creates the possibility of producing connections with what we still are not. And it is in this sense that it is rhizomatic. Jagodzinski and Wallin remind us though that acting in a rhizomatic way does not guarantee a libertarian movement. Concepts such as rhizome may be also misused to support new tyrannies. It is necessary that the new tools employed by artistic research disarticulate the reactivity of representational thought in order that they become political instruments able to prevent their cooptation by neoliberal logic.

It is in opposition to this model that Deleuze (2013) proposes a will-to-art. This Deleuzian concept does not refer to a personal desire of the artist but implies the emergence of something pre-personal and singular which requires from us the invention of ourselves as others, inaugurating forms of existence, creating the fundament of an impersonal theory of subjectivity. An encounter that implies a joint action of heterogeneous flows, composing an immanence plan that maintains the difference and the multiplicity.

Jagodzinski and Wallin (2013) assert that, to prevent education and research of falling into an alienated pattern, it is necessary to effect different processes of subjectivation, where artistic creation and pedagogical practice would be understood as an event. It is necessary that both subject and object are formed in the becoming of the event; an encounter where learning emphasizes more transformation than knowledge, something new is brought to the world, a new cluster of desires is formed. In the sense of getting rid of neoliberal lifestyles and creating ways of life that escape biopower’s clutches, arts-based research must be thought of not as a practice originated from personal creativity and individual expression, but as a power originated from a desiring production which is always already social.

To conceive other outlooks and a to-become-people, it is necessary that the researcher loses its face. The notion of face, in this meaning, is associated to the signs of social class, gender, ethnicity etc. The subject is not prior to the face, it is the face that produces the subject, just like a screen of significance. The face-like features would be an abstract-machine, organizing and controlling body and life, implemented by the expansionist, imperialist and colonizing movement which subtly institutes delimited faces. According to Deleuze and Guattari (1995), the creative thought depends on the dismantling of the face, a political act that involves a clandestine-to-become and propitiates other processes of subjectivation and investigation. Which would be the faces proposed by neoliberalism? Perceive them, face them and betray them is an important challenge for education. This is what Baudrillard also suggests when he comments: “Young people will find it increasingly difficult to disassociate themselves, to search, not their identities but, as they have been constantly demanded to do, but their distance and foreignness” (Baudrillard, 1997).

Jagodzinski and Wallin invite us to create forms of research that shake the self-indulgence of thought, forcing us to think. We might be inspired for it by the strangeness articulated by contemporary artists. After all, if we can learn to do research with the present art, it is because it places us before an impasse, before the absolute other, a learning by non-learning, if we wish to compare everything we already know about what learning is. “Apprehending, in the common view, is holding, grabbing. But here it is just seeing all possibility of grabbing slip from our hands. Is Being before the openness. A challenge” (Koneski, 2009, p. 76).

Before we say farewell

Researching with art may be, after all, to weave a fable on education and research, a space “that unblocks the contingencies in favor of flight lines, […] in favor of an eccentricity potency capable of leading to the discovery of one’s own power” (Garcia, 2002, p. 65). The researching artist, in his/her aesthetic fabling, can surpass the landscapes of the living experience, the frames of memory, the personal narrowing and the cultural determinations. And his/her research may touch the eventual reader, contaminating him/her with its aesthetic intensity. Maybe the quality of a research “[…] is evaluated by the movements that it plots and by the intensities that it creates […] There is never any other criterion but the content of existence, the intensifying of life” (Deleuze; Guattari, 1992, p. 98-99).

Maybe the research with art encourages us to move about in the uncertain contemporary landscapes, in spaces that are not determined a priori, spaces created within the investigative process, opening other possibilities of educating and researching. Possibilities of escaping the double political coercion invented by modernity: “on the one hand, the increasing individuation; on the other, and simultaneously, the totalization and the saturation of coercions imposed by power” (Veiga-Neto, 2011, p. 40). Possibilities of creating a research and an education that perform an ethics of betrayal, establishing forms of dismantling the ordinations, both socio-political and personal, of a fascist nature. This quality of betrayal is an act of love, an act of ultimate fidelity, not to a person, but to the power of art and education of liberating the potency of life. This is the beginning of what may be living life as a work of art.

Source: Photo by Guto Lacaz. Floating installation. 1989. Ibirapuera Park, SP. A Metrópole e a arte. SP, Editora Prêmio (1992)

Figure 6: Auditorium for delicate questions

We can experiment forms of research and education where our question may not be so much about what we can know, or get to know, learn, or show to the other. Our main question should be, how to be responsible, how will we answer for our lives, for our investigations, for the worlds we create?

Researching with art can show us that the vital question in research is not about developing methodically a preexistent thought, but about fostering the birth of something that does not yet exist. “There is no other work, all the rest is arbitrary and ornament” (Deleuze, 2006, p. 213). After all, creating poetic perspectives is also a possibility of establishing other forms of politics, as was suggested by Walter Kohan: “in the first place in thought, a politics of experience and not of truth, a politics of permanent interrogation about the possibility and the forms of politics itself, which uninstalls it from the place of impossibility” (Kohan, 2007, p. 52). Politics that question who we are, in order that we may be in other manners, in our ways of living, researching and, maybe, in our forms of educating.

REFERENCES

AGAMBEN, Giorgio. Infância e História. Destruição da experiência e origem da história. Tradução: Henrique Burigo. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2005. [ Links ]

AGAMBEN, Giorgio. O Que É o Contemporâneo e Outros Ensaios. Tradução: Vinicius Honesko. Chapecó: Argos, 2009. [ Links ]

BACHELARD, Gaston. A Poética do Devaneio. Tradução: Pádua Danesi. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2009. [ Links ]

BAIBICH, Tania Maria; VASCONCELLOS, Sonia Tramujas. A Pesquisa Baseada em Artes Visuais na Educação: novos modos de investigar e conhecer. In: REUNIÃO NACIONAL DA ANPED, 37., 2015, Florianópolis. Anais... Florianópolis, 2015. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/trabalho-gt24-3666.pdf >. Acesso em: 15 set. 2018. [ Links ]

BARONE, Tom; EISNER, Elliot. Arts Based Research. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2012. [ Links ]

BASBAUM, Ricardo. Além da Pureza Visual. Porto Alegre: Editora Zouk, 2007. [ Links ]

BAUDRILLARD, Jean. A Arte da Desaparição. Rio de Janeiro: Editora da UERJ, 1997. [ Links ]

BLANCHOT, Maurice. O Espaço Literário. Tradução: Álvaro Cabral. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1987. [ Links ]

BLANCHOT, Maurice. A Parte do Fogo. Tradução: Ana Maria Scherer. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco , 1997. [ Links ]

BLANCHOT, Maurice. A Conversa Infinita, a Ausência do Livro. v. 3. Tradução: João Moura Jr. São Paulo: Escuta, 2010. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel de. A Invenção do Cotidiano: artes do fazer. Tradução: Ephraim Ferreira Alves. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2013. [ Links ]

COMETTI, Jean-Pierre. Art, Modes Démploi: esquises d’une philosofie de lúsag. Bruxelle: La Lettre Volée, 2000. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles. Conversações. Tradução: Peter Paul Pelbart. São Paulo: Editora 34, 1992. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles. Diferença e Repetição. Tradução: Luis Orlandi; Roberto Machado. São Paulo: Graal, 2006. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles. Proust e os Signos. Tradução: Antonio Piquet; Roberto Machado. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2010. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles. A Imagem Tempo. Tradução: Eloisa A. Ribeiro. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 2013. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Felix. O que é Filosofia. Tradução: Bento Prado Jr.; Alberto Muñoz. Rio de Janeiro: Editora 34, 1992. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Felix. Mil Platôs. Capitalismo e esquizofrenia. v. 1. Tradução: Aurélio Guerra Neto; Celia Costa. Rio de Janeiro: Editora 34 , 1995. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; PARNET, Claire. Diálogos. Tradução: José Gabriel Cunha. Lisboa: Relógio D’Água Editores, 2004. [ Links ]

DEWEY, John. Arte como Experiência. Tradução: Vera Ribeiro. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2010. [ Links ]

DIAS, Belidson. Preliminares: A/r/tografia como metodologia e pedagogia em Artes. In: NEGRIEIROS, Maria das Vitórias; SILVA, Maria Betânia e (Org.). Conferências em Arte/Educação: Narrativas Plurais. 1. ed. v. 1. Recife: FAEB, 2014. P. 249-257. [ Links ]

DIAS, Belidson; IRWIN, Rita. A/r/tografia como metodologia e pedagogia em artes: uma introdução. Santa Maria: Edufsm, 2013. [ Links ]

EISNER, Elliot. The Educatinal Imagination: on the design and evaluation of school programs. New York: Macmillan, 1979. [ Links ]

EISNER, Elliot. O que pode a educação aprender das artes sobre a prática da educação? Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 8, n. 2, p. 5-17. jul./dez. 2008. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Vigiar e Punir: nascimento da prisão. Tradução: Raquel Ramalhete. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes, 1987. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. A Vontade de Saber. história da sexualidade. Tradução: M. T. Albuquerque; A. G. Albuquerque. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Graal, 1988. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Sobre a Genealogia da Ética: uma revisão do trabalho. In: DREYFUS, Hubert; RABINOW, Paul. Michel Foucault, uma trajetória filosófica. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária , 1995. P. 253-278. [ Links ]

GARCIA, Wladimir Antonio; SOUZA, Ana Claudia. A produção de Sentidos e o Leitor: os caminhos da memória. Florianópolis: NUP/ CED/ UFSC, 2012. [ Links ]

GREENE, Maxine. Releasing the Imagination. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publischers, 1995. [ Links ]

HERNANDEZ, Fernando. La investigación basada em las artes. Propuestas para repensar La investigación em educación. Barcelona: Educatio Siglo XXI, n. 26. 2008. [ Links ]

JAGODZINSKI, Jan; WALLIN, Jason. Arts-Based Research, a Critique and a Proposal. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2013. [ Links ]

KASTRUP, Virgínia. A Invenção de Si e do Mundo. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2007. [ Links ]

KOHAN, Walter O. Infância, estrangeiridade e ignorância. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica , 2007. [ Links ]

KONESKI, Anita. A estranha fala da arte contemporânea e o ensino da arte. Palíndromo, Florianópolis: UDESC, n. 1, p. 64-77, jun. 2009. [ Links ]

LATHER, Patty. Method meets art: arts based research practice. New York: The Guilford Press, 2009. [ Links ]

LIMA, Fifo; GAIAD, Paulo. Coleção Vida e Arte. v. 4. Florianópolis: Tempo Editorial, 2010. [ Links ]

LOPONTE, Luciana Gruppelli. Pedagogias visuais do feminino: arte, imagens e docência. Currículo sem Fronteiras , v. 8, n. 2, p. 148-164, jul./dez. 2008. [ Links ]

LOPONTE, Luciana Gruppelli. Arte e Docência: pesquisa e percursos metodológicos. Criar Educação, Criciúma, v. 7, n. 1, jan./jul. 2018. [ Links ]

LYOTARD, Jean-Francois. A Condição Pós-Moderna. Tradução: Ricardo Barbosa. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 2011. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Arlindo. Arte e Mídia: aproximações e distinções. E-Compós, Brasília, v.1, jun. 2004. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Mirian Celeste Ferreira Dias. Arte, Só na Aula de Arte? Revista Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 34, n. 3, p. 311-316, set./dez. 2011. [ Links ]

MOSSI, Cristian Poletti. Notas sobre a Aula (ou a Docência) como Zona de Pesquisa - povoamentos entre escritas, leituras e visualidades. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DA ANPAP, 25., 2016, Porto Alegre. Anais... Porto Alegre, 2016. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://anpap.org.br/anais/2016/simposios/s8/cristian_poletti_mossi.pdf >. Acesso em: 15 set. 2018. [ Links ]

NIETZSCHE, Friedrich Wilhelm. Obras Incompletas. Seleção de textos de Gerárd Lebrun; Tradução: Rubens Rodrigues Torres Filho. São Paulo: Nova cultural, 1974. [ Links ]

NIETZSCHE, Friedrich Wilhelm. Humano, Demasiado Humano. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2005. [ Links ]

NIETZSCHE, Friedrich Wilhelm. A Gaia Ciência. Tradução: Paulo César de Souza. São Paulo: Cia das Letras, 2012. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Marilda Oliveira de. Contribuições da Perspectiva Metodológica ‘Investigação Baseada nas Artes’ e da A/r/tografia para as Pesquisas em Educação. In: REUNIÃO NACIONAL DA ANPED, 36., 2013, Goiânia. Anais... Goiânia, 2013. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/gt24_2792_texto.pdf >. Acesso em: 15 set. 2018. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Marilda Oliveira de. Como ‘Produzir Clarões’ nas Pesquisas em Educação. In: REUNIÃO NACIONAL DA ANPED, 37., 2015, Florianópolis. Anais... Florianópolis, 2015. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/trabalho-gt24-3482.pdf >. Acesso em: 15 set. 2018. [ Links ]

PERNIOLA, Mario. Desgostos, Novas Tendências Estéticas. Tradução: Davi Pessoa Carneiro. Florianópolis: Editora da UFSC, 2010. [ Links ]

PESSI, Maria Cristina Alves dos Santos. Illustro Imago: professoras de arte e seus universos de imagens. 2010. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2010. [ Links ]

READ, Herbert. A Educação pela Arte. Tradução: Valter Siqueira. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2001. [ Links ]

REY, Sandra. A Produção Plástica e a Instauração de um Campo de Conhecimento. Revista Porto Arte, Porto Alegre, UFRGS, n. 9, 1995. [ Links ]

REY, Sandra. Caminhar: experiência estética, desdobramento virtual. Revista Porto Arte , Porto Alegre, UFRGS, v. 17, n. 29, p. 107- 121, nov. 2010. [ Links ]

SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. A arte do encontro e da composição: Spinoza + Currículo + Deleuze. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 27, n. 2, p. 47-57 jul./dez. 2002. [ Links ]

TOURINHO, Irene. Metodologia(s) de pesquisa em Arte/Educação: o que está (como vejo) em jogo? In: DIAS, Belidson; IRWIN, Rita (Org.). Pesquisa Educacional Baseada em Arte: a/r/tografia. Santa Maria: UFSM, 2013. P. 63-70. [ Links ]

VASCONCELLOS, Sonia Tramujas. Entre(dobras) Lugares da Pesquisa na Formação de Professores de Artes Visuais e as Contribuições da Pesquisa Baseada em Arte na Educação. 2015. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2015. [ Links ]

VEIGA-NETO, Alfredo. Foucault e a Educação. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica , 2011. [ Links ]

VINHOSA, Luciano. Obra de Arte e Experiência Estética: arte contemporânea em questões. Rio de Janeiro: Apicuri, 2011. [ Links ]

3The great modern narratives are understood by Lyotard as explanations which lead to final meanings, fabricating the comfort of certainties, excluding theorizations and diverging perspectives.

4Designer capitalism is a term created by Jagodzinski, referring to the control society as described in Deleuze and Guattari’s in Thousand Plateaus (1995).

Received: September 17, 2018; Accepted: May 20, 2019

texto em

texto em