Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Realidade

versão impressa ISSN 0100-3143versão On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.45 no.4 Porto Alegre 2020 Epub 24-Nov-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236105412

OTHER THEMES

The Portrait of Exclusion in Brazilian Universities: the limits of inclusion

IUniversidade Estadual de Londrina (UEL), Londrina/PR - Brazil

IIUniversidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCAR), São Carlos/SP - Brazil

The article aims to present a panorama of the access of disabled people to higher education in Brazil. For decades, public policies have promoted and advocated in favour of inclusive educational practices, but, despite some improvements, the educational system still seems to struggle to accommodate disabled students. Data were drawn from the databases of The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) and of the National Institute for Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP). As evidence shows, governmental measures have prioritised the expansion of private organisations, while the representation of disabled students in Brazilian universities remains a scenario of exclusion.

Keywords: Education; Disabled students; Higher Education; Educational Indicators; Inclusion

O artigo objetiva apresentar um panorama do acesso de pessoas com deficiência ao ensino superior no Brasil. Durante décadas, as políticas públicas têm promovido e defendido práticas educacionais inclusivas, mas, apesar de algumas melhorias, o sistema educacional ainda parece ter dificuldades para acomodar alunos com deficiência. Os dados foram extraídos das bases de dados do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) e do Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (INEP). Os resultados apontam que as medidas governamentais priorizaram a expansão de instituições privadas, enquanto a representação de estudantes com deficiência nas universidades brasileiras continua sendo um cenário de exclusão.

Palavras-chave: Educação Especial; Alunos com deficiência; Educação Superior; Indicadores Educacionais; Inclusão

Introduction

The following article aims to discuss the politics of Special Education (SE) in Higher Education, as a more specific area within the Politics of Inclusion. To clarify, in Brazil, the area of SE legally focuses on disabled people, developmental disorders, and intellectual giftedness (Brasil, 1996; 1999; 2015).Our main objective is to present an analysis of the enrolments of disabled students in higher education institutions in Brazil. The data are drawn from the official governmental Higher Education Census, which is carried out by theNational Institute for Educational Studies and Research “Anísio Teixeira”(INEP), and from the latest Population Census conducted by The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

Specifically, we aim to present what the micro data provided by INEP reveal about the enrolments of the students targeted by the area of Special Education in the Brazilian universities. We begin by reflecting upon the ideological foundations and structural problems of the Politics of Inclusion, identified by intellectuals in the fields of Special Education and Sociology Studies since the early 1990s, and, thereafter, we discuss the advancements and limitations of inclusive practices in Brazilian public policies. Finally, we move from a critical discussion of the dialectics of inclusion and exclusion in the capitalist system to construct an analysis of the space that has been conquered by disabled students in Brazilian universities.

Literature Review

It has been a common agreement amongst researchers that the structural and socio-political changes demanded by the education of disabled people face sociocultural and historical challenges (Bueno, 2013; Goodley, 2011; Kassar, 2013; Oliver; Barnes 2012). In Brazil, despite the attempts of the last 30 or 40 years to restructure the educational system in order to accommodate disabled students, SE still seems to struggle against exclusion, segregation, and philanthropy (Jannuzzi, 2006;Mazzotta, 1996, Santos, 2016; 2020). The 1990s global movement in favour of the inclusion of disabled students was adopted by both the Brazilian government and by many Brazilian scholars as a definite solution to all problems of exclusion. The Brazilian State, however, has implemented policies that do not conform to a universal and equitable education for all, so social responsibility for disabled people remain under the thrall of charity (Mestriner, 2005).

One of the problems seems to be the fact that public policies and researchers rarely consider the dialectics of inclusionandexclusion - which understands one as a fundamental part of the other (Martins, 2012; Marx, 2013;Avis, 2018). That we take this dialectic movement into account does not mean that we overlook the improvements made possible, actually, this is a way of investigating the limits engendered in the core of our socio-political and historical relations in an attempt to promote even more equalitarian practices.

The concepts ofequality, inclusion,andglobalisation have been co-opted by the neoliberal discourse and turned into strategies to fix structural problems of capitalism without providing real change. According to Mészáros (2001, p. 11),

Whatever claims are made for the ongoing process of globalization (sic), there can be no universality in the social world without substantive equality. Evidently, therefore, the capital system, in all of its historically known or conceivable forms, is totally inimical even to its own - stunted and crippled - projections of globalizing (sic) universality.

To Martins (1997), the capitalist society excludes to include, and in doing so, does it in an inhuman and precarious way. The promises of equality and inclusion are reified and part of a long dehumanising process of alienation (Mészáros, 1970; 2001). In SE, Neri (2003) highlights that despite policies that apparently support the education of disabled people, these people in reality have less access to it and, in general, face far more struggles in the schooling process when compared to a non-disabled person. The process is even more complex when disability is associated with other individual characteristics that may place people in social disadvantage, such as race, gender, and social class (Santos, 2020).

The increase in the number of enrolments of students may appear to be a positive side effect of such policies; however, the numbers indicating a discrepancy between age and the level of education point out the structural problems in the quality of the education offered, something which is apparently true in Basic and Higher Education (Almeida; Ferreira, 2018, Bueno, 2013; Ferreira, 1995; Gonçalves, 2012; Oliveira, 2015).

The Brazilian Higher Education sector was, in the 19thcentury, initially designed to fulfil the demands of an elite which aimed to rule economically, culturally, and politically. Throughout the years, Brazilian universities have been the sites of conflicts and political debates in the ongoing battle to make them accessible to the lower classes. They have become socially recognised as the space for debates, production of knowledge, and social intervention, in an attempt to challenge social inequality and the structure of thestatus quo(Chauí, 2003). Although access has been expanded, they remain attended in the main by a small portion of the population (Cunha, 2003).

Despite the literature available, research focusing on disabled students in higher education in Brazil is still restricted. This limitation reveals itself as the result of both the complexities of the matter and the fact that this is yet a recent topic of interest in the field of Education (Almeida; Ferreira, 2018; Ansay, 2015; Cabral; Melo, 2017; Ferreira; Sekkel, 2007; Oliveira, 2013).

Ferrari and Sekkel (2007), back in the last decade when inclusive projects for SE were in their early stages in Brazil, pointed towards three levels of action to accommodate and include disabled students in Brazilian universities. First, in an institutional level, universities had to re-evaluate the way they selected and approved students. Secondly, since teaching qualifications were not - and still are not - a requirement in the career of a university professor, inclusive education poses the need for courses focusing on the improvement of teaching skills. Lastly, old and obsolete teaching practices were to be overcome and professors should seek teaching qualifications that would help them design their classes in order to accommodate differences. These would certainly benefit all (Vygotsky, 1997).

Similar conclusions were drawn by Oliveira, six years later (2013). When analysing the difficulties faced by disabled students at the State University of Rio de Janeiro, the author identified the lack of support and indifference from professors and classmates, the absence of adapted spaces, lack of information and qualification of university staff around campus and professors during classes. In a more recent study, Almeida and Ferreira (2018) refer still to many of those same problems faced by disabled students in the beginning of the decade.

We shall consider here two of the most important elements of the Brazilian legislation for Education, which shape policies in this area, the Federal Constitution (Brasil,1988) and the Law of Directives and Bases for National Education (Brasil, 1996).

The Federal Constitution was conceived at a time of confluence in the Brazilian political forces, after the engagement of a variety of social and political movements fighting in favour of political freedom, social and educational rights, and the support of the State to aid and provide for those in the lower classes. It reiterated human rights as constitutional and ensured the responsibility to provide equal treatment to all without discrimination (Bueno, 2013; Kassar, 2013).

The Law of Directives and Bases for National Education and its supporting documents (Brasil, 2015) ensures in Art. 3º that the schooling process should respect differences and promote equality, providing conditions of access and long-term placements of students in school. It acknowledges Higher Education as a part of the educational system to prepare professionals for different sections of the market and contribute to the development of the Brazilian society. It also designates free special educational assistance at all levels of education to students who are part of the Special Education community, preferably in the regular system.

In addition to these two, further documents have been published to scaffold the schooling process and academic education of disabled students. These students are part of the responsibility of the Brazilian educational system and must receive assistance and aid required to facilitate and mediate their learning processes (Brasil, 1999;2003;2008a; 2008b; 2009; 2011a; 2011b; 2015;2016a; 2016b).

In the face of the challenges imposed upon the schooling processes of disabled students in Basic Education and considering the previously discussed socio-historical struggles to democratise Higher Education in Brazil, we approach the the access, permanence, and completion of studies of students under the focus of Special Education in the Brazilian universities.

Materials and Methods

In Brazil, the Higher Education Census is the most comprehensive instrument for collecting data about the Brazilian Higher Education sector. The results are published on and provided in the website of INEP in the form of a Technical Summary, Statistical Synopsis, and Micro Data. This census is carried out annually and covers all undergraduate and graduate courses in Brazil, presenting an overview of

[…] enrolment and graduates, candidates to university entrance; information on faculty - by qualifications and contract nature - as well as on administrative and support staff; financial data and infrastructure, this initiative provides valuable information about an educational level that is perceived to be in a process of expanding and diversifying (INEP, online).

The collected data, termed Social Indicators, directly impact future policy-making processes for education, including funding, transportation, distribution of books, construction of new schools, universities and libraries, maintenance of schools and to assist in the formulation, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of educational policies in all governmental spheres (Jannuzzi 2006).

Despite their apparent quantitative aspect, both the reality portrayed by Social Indicators and the impact they have on society are qualitative ones. We work from a perspective that understands quality and quantity as a dialectic unit, in which there is noqualitywithoutquantityand noquantitywithoutquality, they “[…] are as inseparable as they are opposed, and that despite all their opposition, they mutually interpenetrate.’ (Engels, 2008 [1892], p. 47).

That they express important aspects of the process of operation of various sectors of our society, social indicators have increased their influence on educational research. In Special Education, their use may serve as evaluative tools of the schooling processes of the students targeted.

Disabled people are part of the educational system from basic to higher education. Hence, quantitative data portraying their presence in or absence from the educational system is a qualitative approach to describe, analyse, and critically understand their reality, mainly when contrasting them to social, educational, and political phenomena.

As the unit of analysis, we consider the number of enrolments of disabled people in Higher Education and their demographic incidence rates. Respectively, data were drawn from the official governmental Higher Education Census carried out by INEP and the latest Population Census conducted by IBGE.

Both are in the public domain and available on the internet to be downloaded, extracted, and processed by a statistical software. We have used IBM SPSS Statistics® (Statistical Package for the Social Science) to access the micro data from INEP. It is important to indicate that out of all categories from the micro-data provided by INEP, we have selected those that characterise students in 2018, which is the last year available (Table 1).

Table 1: Categories considered for analysis in the micro data provided by INEP in 2018

| GOVERNMENTAL AGENCY | CATEGORIES CONSIDERED |

|---|---|

| INEP | TP_CATEGORIA_ADMINISTRATIVA; IN_CONCLUINTE; IN_INGRESSO_TOTAL; IN_DEFICIENCIA_AUDITIVA; IN_DEFICIENCIA_FISICA; IN_DEFICIENCIA_INTELECTUAL; IN_DEFICIENCIA_MULTIPLA; IN_DEFICIENCIA_SURDEZ; IN_DEFICIENCIA_SURDOCEGUEIRA; IN_DEFICIENCIA_BAIXA_VISAO; IN_DEFICIENCIA_CEGUEIRA. |

Source: Designed by the authors based on the categories of INEP.

In 2010, IBGE pointed out the incidence of the different types of disability and the characteristics that constitute this segment of the population. The Census investigated visual and hearing impairments and disabilities, and physical and intellectual disabilities, according to the degree of severity of disability (yes, cannot do in any way; yes, with great difficulty;yes, with some difficulty); the data are collected as stated by the people interviewed. For this paper, we have considered those who responded that they had a disability and all the associated variables. The data extracted from both platforms were organised in tables using Microsoft Excel®.

In the next section, we aim to present an analysis of the data collected from the perspective of historical materialism.

Results and Discussion

Before we present the specific data collected from the Census of Education (INEP), it is crucial to refer to the Census of the Brazilian Population. The last census was conducted in 2010 by the The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) and indicated a population of 45,606,048 million of people with some kind of disability or 23,9% of the population of the country.

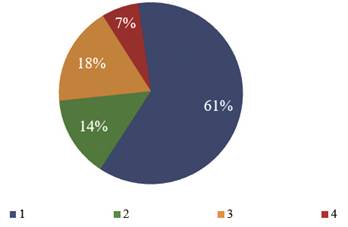

In order to refer to the enrolments of disabled students in higher education, we adopt the reference strata from IBGE which corresponds to the population that could potentially be at university and/or have a university degree. Hence, within the population with some kind of disability, 24,9% (11,355,906) were those between 15 and 64 years of age (Chart 1).

Source: IBGE (2010)

Chart 1: Distribution of the population with 15 years of age or more, according to level of education and with at least one of the disabilities investigated (2010)

In 2010, the Brazilian population with 15 years or more with at least one of the disabilities investigated by the IBGE, according to their level of education, corresponded to 61.1% (6,938,458) of people with no education or incomplete secondary school (Ensino Fundamental); 14.2% (1,612,539) of people with complete secondary school or incomplete high school (Ensino Médio); 17.7% (2,009,995) of people with complete high school and incomplete higher education; and 6.7% (794,914) with complete higher education.

The numbers already indicate that in terms of level of instruction, the Brazilian educational system seems to have failed at providing the disabled population a successful educational journey - mainly considering that 61.1% of the population 15 years of age or more had no education or had not yet completed secondary school. In addition, only 6.7% of the targeted population had completed higher education. One may argue that the strata of data considers even those who are not in higher education age (-17 years-old), however, the category also goes up to 64 years of age, which should be enough to compensate for that. Hence, we may not ignore that the disabled population in Brazil has been largely denied access to a successful educational journey, including higher education

According to the 2010 census of the population, the strata of data we have drawn upon to compare and contrast with the data provided by the educational census is of those between 15 and 64 years of age who completed high school but were unable to complete higher education, that is, 2,009,995 million people.

The first strata of data to be discussed presents the comparison between the enrolments of disabled students, the percentage of the total of enrolments and the total number of enrolments in Brazilian universities (Table 2).

Table 2: Number of enrolments of disabled students and total number of enrolments in Brazilian higher education (2009-2018)

| Year | Enrolments of disabled students | Percentage of the total | Total number of enrolments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 23 135 | 0.33% | 6 982 018 |

| 2010 | 25 205 | 0.30% | 8 337 219 |

| 2011 | 29 033 | 0.32% | 8 961 724 |

| 2012 | 34 656 | 0.36% | 9 565 483 |

| 2013 | 37 796 | 0.38% | 9 929 289 |

| 2014 | 45 088 | 0.41% | 10 793 935 |

| 2015 | 51 685 | 0.46% | 11 187 296 |

| 2016 | 49 813 | 0.43% | 11 449 222 |

| 2017 | 52 542 | 0.45% | 11 589 194 |

| 2018 | 59 496 | 0.49% | 12 043 993 |

Source: designed by the authors based on data collected from the INEP.

The number of enrolments of disabled students in Brazilian universities has grown from 23,135 to 59,496 between 2009 and 2018, which represents an increase of about 257%, whereas the total number of enrolments represents an increase of 172.5%. If we consider the total number of enrolments and contrast these to the number of enrolments of disabled students, we find that the representation of disabled students in universities ranges only between 0.33% and 0.49%, in the period analysed. Furthermore, considering the total number of disabled people 15 years of age or more in 2010 (11,355,906), their representation in the universities falls to 0.2% and 0.5%, in 2009 and 2018, respectively. Similarly, the level of instruction targeted (2,009,995) in comparison to the enrolments indicates a range between 1.15% and 2.96%.

Let us consider ideal numbers to better illustrate our arguments. If all disabled people withcomplete high school and incomplete higher education(2,009,995) were enrolled in 2018, the representation of disabled students in universities would be expected reach the mark of 16.6%. Please note that even ignoring, in this comparison, the rest of the disabled population, the contrast between the ideal and the real percentage of representation is demonstrated by a huge gap. Considering that not all students who finish high school go to university, of course, this percentage serves only as an illustration, but even so, it does not lose its validation as an argument.

There have been a number of public policies, mainly in the in the last two decades, which aim to increase the access of the Brazilian population to higher education, such as ProUni (Program University for All), laws of affirmative action (for African and indigenous descendants, disabled people, and students from public schools), ReUni (a program for the support, restructuring, and expansion of Brazilian Federal universities), and others. Hence, the number of disabled students in the universities have increased following these attempts to democratise access to higher education, which had been restricted mainly to the white upper-middle-class and Brazilian elites. As evidence demonstrates, such public policies have indeed had an impact on the access to higher education; at the same time, they are still very much limited when we consider the percentages in comparison to the total population. In another illustration, if the growth rate increases 257% every nine years and we could freeze the population growth, it would still take more than 30 years to all of the 800,000 disabled students to have access to university education (around 1,000,000 in 2045).

In fact, evidence in the number of enrolments demonstrates that such recent public policies have had a larger impact on the growth of private universities rather than on the public institutions in Brazil (Table 3).

Table 3: Number of enrolments of students in Public and Private Brazilian universities (2009-2018)

| Year | Public | Private | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disabled students | Total | Disabled students | Total | ||

| 2009 | 6 904 (0.40%) | 1 685 860 | 16 231 (0.30%) | 5 296 158 | |

| 2010 | 7 776 (0.39%) | 1 985 985 | 17 429 (0.27%) | 6 351 234 | |

| 2011 | 7 837 (0.36%) | 2 132 207 | 20 956 (0.30%) | 6 829 517 | |

| 2012 | 10 030 (0.43%) | 2 332 357 | 23 804 (0.32%) | 7 233 126 | |

| 2013 | 11 694 (0.48%) | 2 398 365 | 25 361 (0.33%) | 7 530 924 | |

| 2014 | 13 095 (0.53%) | 2 455 319 | 26 221 (0.31%) | 8 338 616 | |

| 2015 | 14 844 (0.60%) | 2 438 477 | 31 539 (0.36%) | 8 748 819 | |

| 2016 | 17 574 (0.70%) | 2 489 292 | 31 035 (0.34%) | 8 959 930 | |

| 2017 | 17 143 (0.66%) | 2 562 709 | 33 601 (0.37%) | 9 026 485 | |

| 2018 | 20 280 (0.77%) | 2 616 583 | 38 379 (0.40%) | 9 427 410 | |

Source: designed by the authors based on data collected from the INEP.

The expansion of private universities in Brazil is emphasised by the growth rate in enrolments, represented by 155.2% in public universities and 178% in the private ones. At first glance, the presence of disabled students in private universities seems to overshadow public institutions - a deeper look at the numbers and percentages, however, may indicate otherwise. In 2009, there were 6,904 disabled students enrolled in public universities, a number that grew to 20,280 in 2018, or an increase of a bit more than 193%. On the other hand, the numbers in private universities grew 137%, from 16,231 to 38,379. At the same time, public university disabled students represented only 29,84% in 2009 and 34,6% in 2018, highlighting the dominance of private higher institutions in the country.

Of equal importance is to deal with the percentages in contrast to the total enrolments. In public institutions, despite the constant ups and downs, the enrolment of disabled students represented 0.40% in 2009, only falling below that in 2010 and 2011, and in 2018 reaching 0.77%. In contrast, the students in private universities represent 0.30% in 2009 and 0.40% in 2018, which means that the representation of disabled students in private universities only reaches the same percentage as public universities in 2018. As noted, public universities, albeit still limited, indicate a higher percentage of disabled students in comparison to private institutions when considering both their total number of enrolments. In enrolments, however, private universities still appeared to attract a larger number of students.

Another aspect that has been under discussion both in our research group, and which has also been the focus of other studies for some years, is the importance to consider not only the access but also to provide students with tools and opportunities to guarantee that they will be enabled to successfully complete their schooling process, in basic and higher education. Hence, it is of paramount importance to discuss the percentage of students who completed or came close to completing their undergraduate courses. In order to do so, we contrasted the number of students enrolled (number of enrolments) with the number of graduates (according to the census, those who successfully completed at least 80% of the course), from 2009 to 2018 (Table 4).

Table 4: Number of enrolments in comparison to the number of graduate students in Brazilian higher education in comparison to an index number (2009-2018)

| Year | Number of Enrolments | Graduates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disabled Students | Total | Disabled students | Index number | Total | ||

| 2009 | 23 135 | 6 982 018 | 2 037 | 100% | 967 558 | |

| 2010 | 25 205 | 8 337 219 | 2 769 | 135.9% | 980 662 | |

| 2011 | 29 033 | 8 961 724 | 2 858 | 140.3% | 1 022 711 | |

| 2012 | 34 656 | 9 565 483 | 3 518 | 172.7% | 1 056 069 | |

| 2013 | 37 796 | 9 929 289 | 3 540 | 173.7% | 994 812 | |

| 2014 | 45 088 | 10 793 935 | 3 569 | 175.2% | 1 030 520 | |

| 2015 | 51 685 | 11 187 296 | 5 048 | 247.8% | 1 152 458 | |

| 2016 | 49 813 | 11 449 222 | 4 663 | 228.9% | 1 170 960 | |

| 2017 | 52 542 | 11 589 194 | 5 152 | 252.9% | 1 201 145 | |

| 2018 | 59 496 | 12 043 993 | 5 475 | 268.7% | 1 264 778 | |

Source: designed by the authors based on data collected from the INEP

Adopting 2009 as a reference (Indexnumber), in the period analysed, there was a growth of 268.7% of graduates. Despite the apparent improvement, the gap between those who enrolled and those who managed to graduate is somewhat problematic. The percentage of students who graduated ranged between 9.5% (2014) and 13.8% (2009). When we consider only disabled students, the numbers fell to a range between 7.9% (2014) and 10.9% (2010). The numbers, therefore, indicate 2014 as the lowest percentage of graduate students and 2009 as the highest in the totality of students and 2010 when the disability was isolated. Data indicate that when contrasted with the total number of enrolments and graduates, disabled students were less likely to complete 80% of the course required to be a graduate. Only in 2012 (11% and 10.1%) were the percentages closer to being equal.

We may infer that, despite the politics of inclusion and assessment and the small differences in percentage between disabled and non-disabled students, there have been very few changes that could promote the completion of the courses attended by disabled students. In this case, we indicate the importance of studies which analyse the schooling process of disabled students in higher education, as we see this as a limitation of the research developed here.

Final Remarks

We have presented a discussion of the representation and participation of disabled students in Brazilian universities from 2009 to 2018. Data indicates that the politics of inclusion have indeed had an impact on the expansion of access to higher education in Brazil in the period analysed. However, governmental policies, despite the influence and importance of public universities, apparently contributed in a larger scale to the expansion of private universities rather than focusing investments in the public sector.

When considering the growth rate of the total number of disabled students from 2009 to 2018, politics of inclusion seem to be a success. Hence, in submitting those numbers to a simple statistical analysis, we conclude that (1) representation of disabled students in Brazilian universities is still limited; (2) most disabled students are in private universities, but their representation in public institutions is almost two times higher; (3) studies that analyse the schooling process of disabled students from the first to the last year are fundamental as an indicator of the effectiveness of internal inclusive practices; finally, (4) perhaps, as indicated by Calderón-Almendros (2018) andBerghs et al. (2019), the politics of inclusion require revision. We can no longer be satisfied with the current scenario of access to education; it is a portrait of exclusion not inclusion.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, José Guilherme de Andrade; FERREIRA, Eliana Lucia. Sentidos da Inclusão de Alunos com Deficiência na Educação Superior: olhares a partir da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, São Paulo. Número Especial, p. 67-75, 2018. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2175-3539/2018/047 >. Acesso em: 02 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

AVIS, James. A Note on Class, Dispositions and Radical Politics. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, v. 16, n. 3, p. 166-184, 2018. [ Links ]

BERGHS, Maria; ATKIN, Karl; HATTON, Chris; THOMAS, Carol. Do Disabled People Need a Stronger Social Model: a social model of human rights?, Disability & Society, v. 34, n. 7-8, p. 1034-1039, 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil: promulgada em 5 de outubro de 1988. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 1988. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Câmara dos Deputados. Lei Federal nº 9394 de 20 de dezembro de 1996 e suas atualizações 2013; 2015; 2018. Estabelece as diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 3298, de 20 de dezembro de 1999. Regulamenta a Lei nº 7.853, de 24 de outubro de 1989, dispõe sobre a Política Nacional para a Integração da Pessoa Portadora de Deficiência, consolida as normas de proteção, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 1999. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.andi.org.br/file/51328/download?token=RDL1NJoK >. Acesso em: 02 set. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Portaria Federal 3284, de 07 de novembro de 2003. Dispõe sobre requisitos de acessibilidade de pessoas portadoras de deficiências, para instruir os processos de autorização e de reconhecimento de cursos, e de credenciamento de instituições. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 2003. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Especial. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. Brasília, DF, 2008a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Edital nº 04, de 05 maio de 2008. Edital seleção de propostas. Programa Incluir: Acessibilidade na Educação Superior. Brasília, DF, 2008b. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/programa-incluir/191-secretarias-112877938/sesu-478593899/13380-programa-incluir-edital-e-resultados >. Acesso em: 02 maio 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 6949, de 25 de agosto de 2009. Dispõe sobre a Convenção Internacional sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência e seu Protocolo Facultativo, assinados em Nova York, em 30 de março de 2007. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 2009. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/decreto/d6949.html >. Acesso em: 04 abr. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 7611, de 17 de novembro de 2011. Dispõe sobre a educação especial, o atendimento educacional especializado e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 2011a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_basica/censo_escolar/legislacao/2012/decreto_n_7611_17112011.pdf >. Acesso em: 03 maio 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 7612, de 17 de novembro de 2011. Institui o Plano Nacional dos Direitos da Pessoa com Deficiência - Plano Viver sem Limite. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 2011b. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/decreto/d7612.htm >. Acesso em: 02 set. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13146, de 6 de Julho de 2015. Institui a Lei Brasileira de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência (Estatuto da Pessoa com Deficiência). Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 2015. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2015/Lei/L13146.htm >. Acesso em: 05 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13409, de 28 de dezembro de 2016. Altera a Lei nº 12.711, de 29 de agosto de 2012, para dispor sobre a reserva de vagas para pessoas com deficiência nos cursos técnico de nível médio e superior das instituições federais de ensino. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 2016a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/lei/2016/lei-13409-28-dezembro-2016-784149-publicacaooriginal-151756-pl.html >. Acesso em: 03 ago. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Portaria Normativa nº 13 de 11 de maio de 2016. Dispõe sobre a Indução de Ações Afirmativas na Pós-Graduação, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, 2016b. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.faders.rs.gov.br/legislacao/4/517 >. Acesso em: 02 maio 2019. [ Links ]

BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira. Políticas de Escolarização de Alunos com Deficiência. In: MELETTI, Silvia Márcia Ferreira; BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira. Políticas Públicas, Escolarização de Alunos com Deficiência e a Pesquisa Educacional. Araraquara: Junqueira&Marin, 2013. P. 25-38. [ Links ]

CABRAL, Leonardo Santos Amâncio; MELO, Francisco Ricardo Lins Vieira de. Entre a Normatização e a Legitimação do Acesso, Participação e Formação do Público-Alvo da Educação Especial em Instituições de Ensino Superior Brasileiras. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 3, p. 55-70, 2017. [ Links ]

CALDERÓN-ALMENDROS, Ignácio. Deprived of Human Rights. Disability & Society , v. 33, n. 10, p. 1666-1671, 2018. DOI: 10.1080/09687599.2018.1529260. [ Links ]

CHAUÍ, Marilena. A Universidade Pública sob Nova Perspectiva. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 24, 2003. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Luiz Antônio. Ensino Superior e Universidade no Brasil. In: Lopes, Eliana Marta Teixeira (Org.). 500 Anos de Educação no Brasil. 3. Ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2003. P. 151-204. [ Links ]

ENGELS, Friedrich. Socialism: Utopian and scientific. London: Allen and Unwin, 2008. [ Links ]

ENGELS, Friedrich. Anti-Dühring. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2015. [ Links ]

FERRARI, Marian Dias; SEKKEL, Marie Claire. Educação Inclusiva no Ensino Superior: um novo desafio. Psicologia Ciência e Profissão, v. 27, n. 4, p. 636-647, 2007. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Julio Romero. A Exclusão da Diferença: a educação do portador de deficiência. 3a ed. Piracicaba: Unimep, 1995. [ Links ]

GONÇALVES, Taísa Gabriela Liduenha. Escolarização de Alunos com Deficiência na Educação de Jovens e Adultos: uma análise dos indicadores educacionais brasileiros. 2012. Thesis (MA in Education) - Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, PR, 2012. [ Links ]

GOODLEY, Dan. Disability Studies: an interdisciplinary introduction. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2011. [ Links ]

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico 2010. Brasília: 2010. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/ >. Acesso em: dezembro de 2019. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Anísio Teixeira. Microdados da Educação Superior. 2017. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/censo-da-educacao-superior >. Acesso em: 03 jun. 2019. [ Links ]

JANNUZZI, Gilberta. A Educação do Deficiente no Brasil: dos primórdios ao início do século XXI. 2. ed. Campinas: Autores associados, 2006. [ Links ]

KASSAR, Mônica de Carvalho Magalhães. Uma Breve História da Educação de Pessoas com Deficiências no Brasil. In: MELETTI, Silvia Ferreira; KASSAR, Mônica de Carvalho Magalhães (Org.). Escolarização de Alunos com Deficiências: desafios e possibilidades. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2013. [ Links ]

MARTINS, José de Souza. A Exclusão Social e a Nova Desigualdade. São Paulo: Editora Vozes, 1997. [ Links ]

MARTINS, José de Souza. A Sociedade Vista do Abismo: novos estudos sobre exclusão, pobreza e classes sociais. 4. ed. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes, 2012. [ Links ]

MARX, Karl. O Capital: crítica da Economia Política: Livro I: o processo de produção do capital. São Paulo: Boitempo , 2013. [ Links ]

MAZZOTTA, Marcos. Educação Especial no Brasil: história e políticas públicas. São Paulo: Cortez, 1996. [ Links ]

MESTRINER, Maria Luiza. O Estado entre a Filantropia e a Assistência Social. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2005. [ Links ]

MÉSZÁROS, Ístvan. Marx’s Theory of Alienation. London: Merlin Press, 1970. [ Links ]

MÉSZÁROS, Ístvan. Socialism or Barbarism: From the ‘American Century’ to the Crossroads. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001. [ Links ]

MÉSZÁROS, Ístvan. The power of Ideology. London: ZED BOOKS LTD, 2005. [ Links ]

MÉSZÁROS, Ístvan. O Século XXI: socialismo ou barbárie? São Paulo: Boitempo , 2012. [ Links ]

NERI, Marcelo. Retratos da Deficiência no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: FGV/IBRE, CPS, 2003. [ Links ]

OLIVER, Michael; BARNES, Colin. The New Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Cristina Borges de. Jovens Deficientes na Universidade: experiências de acessibilidade? Revista Brasileira de Educação , v. 18, n. 55, p. 961-1065, out./dez. 2013. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Vítor Hugo. Escolarização de Alunos com Necessidades Educacionais Especiais no Paraná: predominância da segregação e da filantropia. 2015. Thesis (MA in Education) - Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, PR, 2015. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Natália Gomes. Os Indicadores Educacionais das Instituições Especiais no Brasil: a manutenção dos serviços segregados na educação especial. 2016. Thesis (MA in Education) - Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, PR, 2016. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Natália Gomes. Desigualdade e Pobreza: análise da condição de vida da pessoa com deficiência a partir dos indicadores sociais brasileiros. 2020. Doctoral Dissertation - Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, 2020. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKI, Lev Semionovich. Obras Escogidas V: Fundamentos de Defectología. Madrid, 1997. [ Links ]

Received: July 15, 2020; Accepted: October 07, 2020

texto em

texto em