Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Realidade

versión impresa ISSN 0100-3143versión On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.46 no.2 Porto Alegre 2021 Epub 24-Mayo-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236105199

OTHER THEMES

Teaching Performance on Educação Básica in Pandemic Time

IUniversidade Católica de Petrópolis (UCP), Petrópolis/RJ - Brazil

This article considers teaching in Educação Básica, in the Brazilian context, during the Covid-19 pandemic and suspension of face-to-face classes. The survey was attended by 209 teachers from the city of Juiz de Fora, at Minas Gerais state, who answered the questionnaire used as an instrument. The objective was to analyze the thoughts, feelings, challenges, and perspectives of teachers in this period of calamity. Content analysis and descriptive statistics were performed. The findings point to emerging categorical sets that highlight the teachers’ concerns with the marked inequalities, the main difficulties in curricular educational practices and the expectations of education professionals with the return to schools.

Keywords: Covid-19; Social Distancing; Basic Education; Remote Teaching; Educational Practices

Este artigo considera a docência na Educação Básica, no contexto brasileiro, durante a pandemia da Covid-19 e suspensão das aulas presenciais. A pesquisa contou com a participação de 209 professores da cidade de Juiz de Fora, MG, que responderam ao questionário utilizado como instrumento. O objetivo foi analisar os pensamentos, sentimentos, desafios e perspectivas dos docentes nesse período de calamidade. Foi realizada a análise de conteúdo e a estatística descritiva dos dados. Os achados apontam conjuntos categoriais emergentes que destacam as preocupações docentes com as acentuadas desigualdades, as principais dificuldades nas práticas educativas curriculares e as expectativas dos profissionais da educação com o retorno às escolas.

Palavras-chave: Covid-19; Distanciamento Social; Educação Básica; Docência Remota; Práticas Educativas

Introduction

Since the end of 2019, the new coronavirus agent has spread rapidly around the world, affecting various segments of society, including the school education system. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Covid-19 is a disease whose clinical condition can vary from asymptomatic infections to severe respiratory conditions (WHO, 2020). In this sense, due to the increasing rates of new cases and deaths in several countries, in March 2020, the disease was characterized as a pandemic one and the countries had to involve the entire government and society in order to save lives and minimize the impacts of calamity (WHO, 2020).

In Brazil, the Educação Básica1 schools, due to the adoption of quarantine as a measure to contain the contagion of the virus, had their face-to-face classes suspended. Saraiva, Traversini and Lockmann (2020) point out that the paralysis of practices in schools caused the transposition of school activities through the use of digital tools, especially in private educational institutions. For Dussel (2020), the classroom is a particular environment that enables ways of working with knowledge, which organizes bodies and times in activities, which pose intellectual challenges not aligned to the improvised educational arrangements in the emergency. In this scenario, the challenge arises for the search for alternatives for maintaining school activities. Difficulties were tensioned in the school communities and mention should be made of some regulations prepared to deal with the outbreak, especially those that influenced the educational context in the city of Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais.

Law nº. 13,979, of February 6, 2020 (Brazil, 2020a), which has the possible measures aimed at protecting the community, establishes that social distance and quarantine are alternatives to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus. In view of the provisions, Decree no. 47,886, of March 15, 2020 (Minas Gerais, 2020b) instituted the Plano de Prevenção e Contingenciamento em Saúde da Covid-19 Committee, according to the Public Health emergency situation declared by Decree NE nº. 113, of March 12, 2020 (Minas Gerais, 2020a), for decisions on the implementation of measures in the state, according to the phase of containment and mitigation of the epidemic.

The growing number of cases, in Brazil and in Minas Gerais, led the Extraordinary Committee Covid-19 to formalize deliberation no. 18, of March 22, 2020, establishing that face-to-face activities in Educação Básica, in the state system, should be suspended indefinitely (Minas Gerais, 2020c). In addition, the Conselho Estadual de Educação (Minas Gerais, 2020d) published, on March 27, 2020, guidelines related to the reorganization of school activities, determining that, in Elementary and Middle Schools, and High School on an exceptional basis, any curricular components could be worked on remotely, observing the possibilities of online access for students and teachers. It should be stressed that the document did not provide any provision of the non-face-to-face modality for Kindergarten.

On April 28, 2020, the Conselho Nacional de Educação (CNE) approved the Guidelines to guide Educação Básica schools and Higher Education Institutions during the pandemic period (Brazil, 2020b). These suggested that states and cities look for alternatives to minimize the need for face-to-face replacement of school days, in order to maintain a flow of school activities to students, while the emergency situation persisted. Also, they authorized the education systems to compute non-face-to-face activities to fulfill the workload, listing a series of non-face-to-face activities that could be used during the pandemic situation. Video classes, virtual platforms, social networks, television or radio programs and printed teaching material were some of the possibilities suggested. In the search for efficient solutions to avoid an increase in inequality, evasion, and repetition, the CNE recommended that activities be offered from early childhood education.

It is noted that the school education system suffered instabilities and discrepancies due to the unpredictability caused by the worldwide spread of Covid-19. Morgado, Sousa and Pacheco (2020) affirm that the change in the way teachers work is a good example, given that the online teaching adopted accelerates, in an intense way, the predominance of digital subjectivity. Ferreira and Barbosa (2020) emphasize that the pandemic leads educational institutions, public and private, to raise the debate on the role of education in today’s society. In this premise, the present research is justified by the need to give voice to Educação Básica teachers, directly involved in the circumstances experienced by school institutions, so that thoughts, feelings, challenges, and perspectives can be recognized and analyzed, for the benefit of education and all those involved in the teaching-learning process.

Method

The present study used the questionnaire as a technique for collecting data. Descriptive statistics and qualitative analysis of the responses emerging from the 209 teachers of Kindergarten to High School in Educação Básica were adopted in the city of Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais. According to Chaer, Diniz and Ribeiro (2011), the questionnaire is a very viable and pertinent technique when it comes to problems whose research objects correspond to empirical issues, involving opinions, perceptions, positions, and preferences of the respondents.

The questionnaire was prepared by Google Forms, with multiple choice and discursive questions. According to Gil (1999), the instrument’s questions must be formulated in a clear, concrete, and precise manner, not suggesting answers, and addressing a single idea at a time, enabling a more assertive interpretation. Chaer, Diniz and Ribeiro (2011) argue that the researcher should formulate questions in sufficient numbers, considering the proposed theme and the order of the inquiries, so that there is a connection.

Regarding the structure of the form, sent to all participants via WhatsApp or Messenger, it initially presented the researchers and the subject of the study. Then it displayed the Informed Consent Document with the objective and justification of the research, as well as guarantees of the anonymity of the participants and the consolidation of the results. To proceed with the questionnaire, participants should first click on the acceptance option. Marconi and Lakatos (1999) emphasize the importance of being sent, along with the questionnaire, the nature of the research, its importance, and the need to obtain answers, seeking to arouse the interest of the guest in participating in the study. In the objective questions of the form, the participants indicated one or more options and wrote about other alternatives not included in the instrument. In the discursive questions, the participants freely wrote a paragraph for their respective answers. Chaer, Diniz and Ribeiro (2011) consider that open questions allow freedom of answers, in which the respondent’s own language can be used.

For data analysis, the Content Analysis technique proposed by Bardin (2011) was adopted. According to the author, the object, in this analysis, is the word, the practice of the language carried out by identifiable emitters in the search for realities through messages. The technique aims at the knowledge of psychological, sociological, historical variables, among others, through a deduction mechanism, based on indicators reconstituted from a sample of private messages.

The different phases of Content Analysis were considered, which are organized in: a) pre-analysis - phase of the organization to make operational and systematize the initial ideas in the scheme of the development of the successive operations of the analysis plan; b) exploration of the material, a long and tedious phase, which consists of coding, discounting or enumeration operations, according to previously formulated rules; and c) treatment of results, inference and interpretation - in this phase, the gross results are treated in a way that they are meaningful and valid (Bardin, 2011).

Results and discussion

The results of the closed format questions were organized in tables with graphics that analyze the profile of the participants and the technologies used in the practice of remote teaching, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

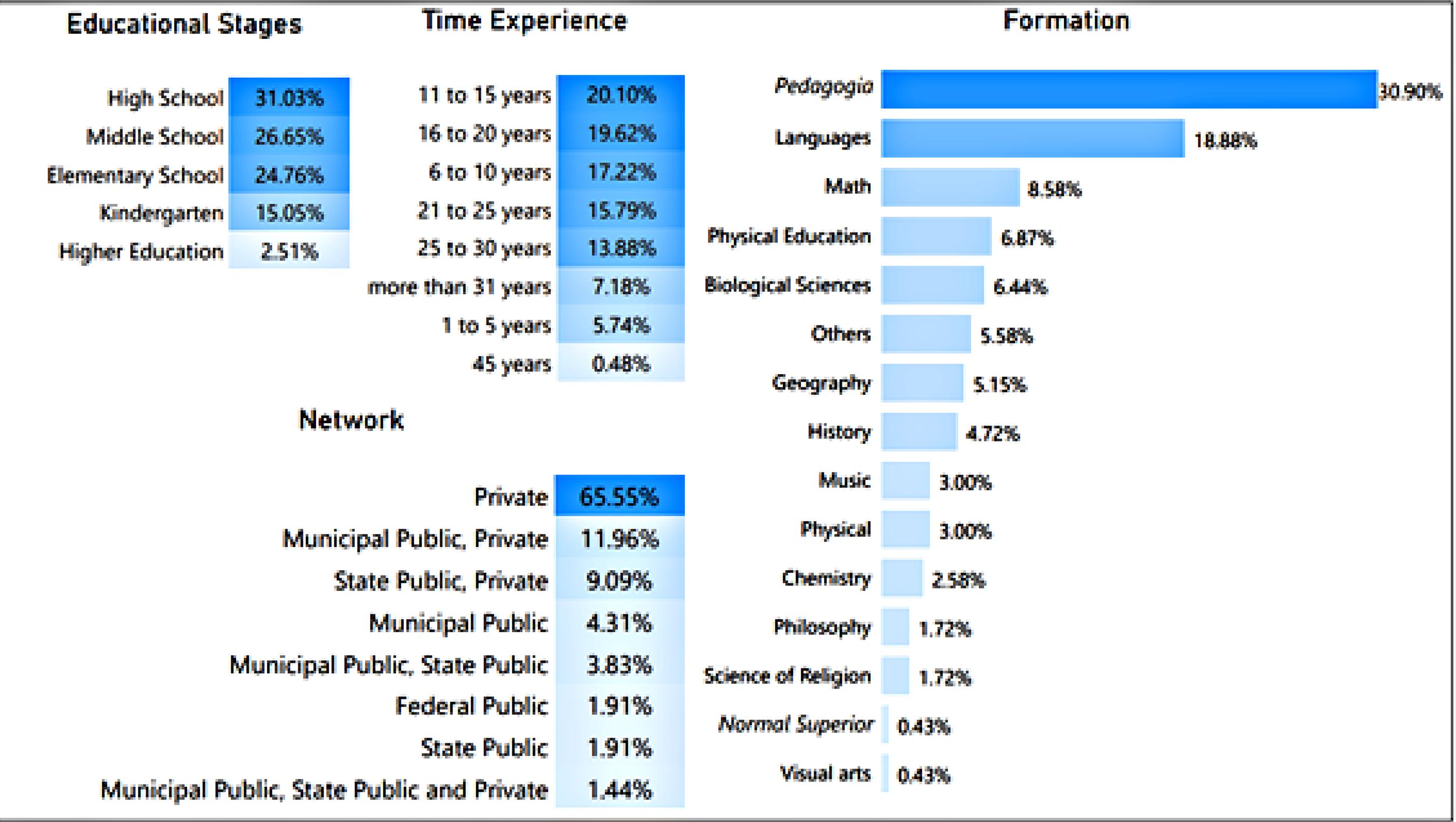

Chart 1 shows that the majority of participating teachers work in High School (31.03%). Respectively, the concentration of the sample indicates that teachers teach in Middle School (26,65%), Elementary School (24,76%), in Kindergarten (15,05%) and in Higher Education (2,51%). This last stage, although not part of the present research, emerged due to the fact that teachers who teach in High School also work in Higher Education. In this premise, it is added that the data revealed that 55.98% of these professionals teach exclusively in a teaching stage of Educação Básica, that 36.37% work in two and that 7.65% work in three or four educational stages, such as teachers with degrees in Music, Philosophy, Languages or Physical Education.

Regarding the time of experience, it is noted that the highest percentage (20.10%) is concentrated in the period of 11 to 15 years of teaching. Then, between 16 and 20 years old (19.62%), between 6 and 10 years old (17.22%), between 21 and 25 years old (15.79%), between 25 and 30 years old (13.88%) and for more than 31 years (7.18%). It is noteworthy that one of the participants stated that he had worked as a teacher for 45 years (0.48%). It is worth remembering that this research counted on the contribution of professionals with different performance periods, which corroborates the heterogeneity of this study sample.

It is observed that, when focusing on the training of the participants, the data point to a greater grouping of licensed teachers in the Pedagogia2 course. (30,90%). It is believed that it is due to the fact that this course is aimed at teachers who work mainly in the first two stages of Educação Básica: Kindergarten and Elementary School. Then, there is evidence of training in the Languages course (18.88%), which is justified, because, in addition to the Portuguese language being, generally, a discipline with a greater number of classes in the curriculum, this is a course which also licenses teachers of Portuguese and other languages, such as English and Spanish. It is noted, however, that, in the main degrees, there was representation of teachers, although the percentages are different. In addition, it should be noted that the percentage of 5.58% was included in the bar called Others due to the fact that the participants had taken, in addition to the degree, other bachelor’s courses such as Law, Psychology, Electrical Engineering, Communication and Social Service.

With regard to the performance network, the largest concentration of participating teachers is located in the private education network (65.55%). It is noticed that part of the participants works both in the private network and in the public network, in the municipal (11.96%), state (9.09%) or, still, in the private network and in the municipal and state public network (1.44%). There are those who teach only in public schools, whether in municipal education (4.31%), state education (1.91%) federal (1.91%) or in state and municipal public schools (3.83%).

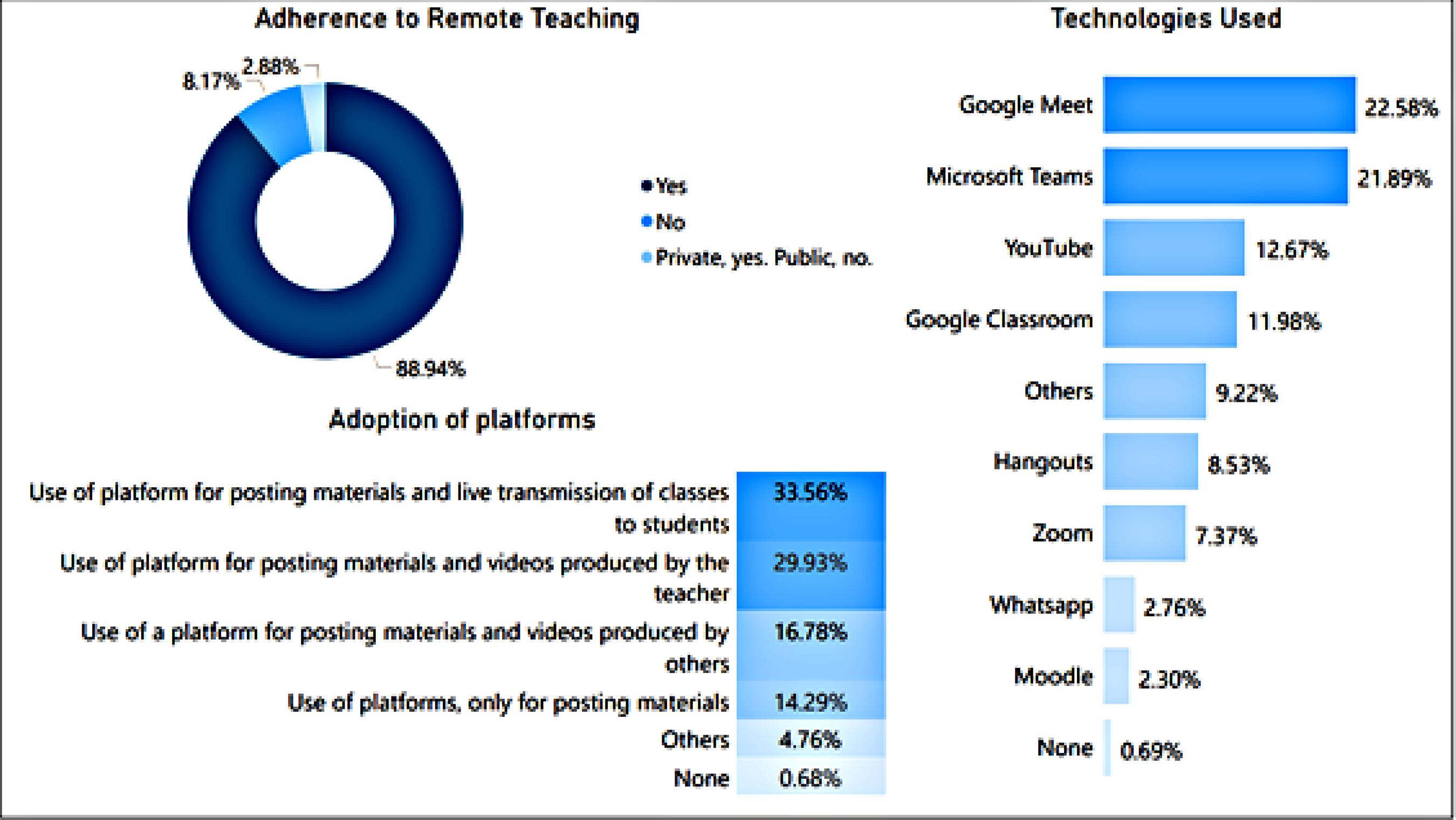

Chart 2 illustrates the organization of data related to adherence to remote teaching and the adoption of platforms and technologies in the educational system of Juiz de Fora, through the pandemic. It is considered that 88.95% of the participants were, in some way, teaching by digital means, which represents the vast majority of the sample in this study. The results show that 8.17% of the teachers stated that they were not working in Education remotely and that 2.88% informed that they were teaching remotely in the private network, while the public network in which they work had not yet adopted this system. It should be noted that the period of data collection for this research took place between the months of April and May 2020 and that, until now, the public school system had not carried out any educational practices after the suspension of face-to-face classes.

Source: Cipriani, Moreira e Carius (2020).

Table 2 Adherence to Remote Teaching and Adoption of Platforms and Technologies

The technologies most used by teachers, in the remote educational context, are associated with Google Meet (22.58%) and Microsoft Teams (21.89%). It is worth mentioning that, in a lower percentage, YouTube (12.67%), Google Classroom (11.98%), Hangouts (8.53%), Zoom (7.37%), WhatsApp (2.76%) and Moodle (2.30%). It was noticed that the words Others (9.22%) and None (0.69%) were also enunciated by the participants, when referring to the adoption of new digital technologies in their teaching practices.

Regarding the adoption of platforms, the highest percentages are concentrated on the use of these for posting materials and transmitting live classes to students (33.56%) followed by the use of the platform to post materials and videos produced by the teacher (29.93%). However, the use of platforms for posting material and videos produced by others (16.78%), or just for posting material (14.29%), appeared in the results. It was also noted that the option Others (4.76%) was present in the answers, and the option None (0.68%) was also pointed out, showing the lack of use of any type of platform by school institutions.

The results of the discursive questions were organized based on Content Analysis. Bardin (2011) asserts that the codification takes effect from precise rules when considering the raw data of the text, which, by clipping, aggregation, and enumeration, allow to achieve a representation of the content. In this perspective, the organization was considered through the choice of units, the enumeration in the word counting, the classification and the aggregation in the definition of the categories.

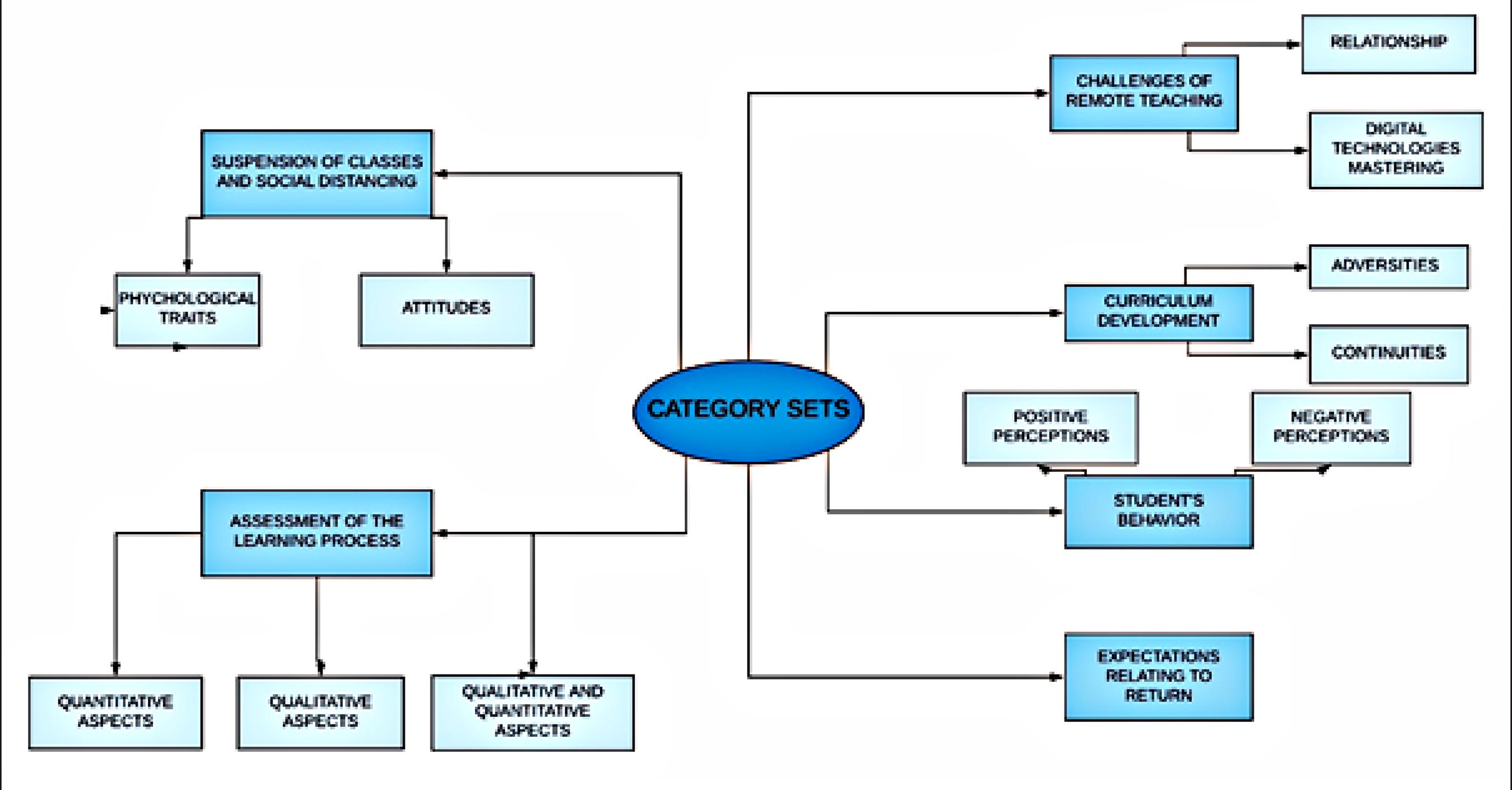

The information emerging from the answered questionnaires was grouped into category sets, as shown in the infographic (Figure 1):

The category sets that emerged from the initial definition of the analytical categories, by grouping the meaning of the content elements, were: Suspension of Classes and Social Distancing; Challenges of Remote Teaching, Curriculum Development, Assessment of the Learning Process; Student Behavior and Expectations Relating to the Return of Face-to-face Classes. In addition, in the last categorization, when a greater criterion and depth of the content clippings were estimated, categories that were linked to the initials were consolidated, as shown in Figure 1.

Some context units were selected to illustrate the discussion of results in each of the categories. However, due to the high number of participants, only a few examples of phrases that emerged from the explanations are presented and corroborated, among many others, with the saturation of the results. It should be noted that codes were assigned to each answer, organized according to the profile of each respondent, preserving the teachers’ identity. Thus, in addition to receiving a number, the stages in which the professionals work were specified: Kindergarten, Elementary School, Middle School, High School, and, also, the network: Public (Pub) and/or Private (Pri). In case of the teacher’s performance in more than one educational stage or teaching network, the abbreviations were added in a single code and separated by a hyphen.

Suspension of Face-to-face Classes and Social Distancing

It was observed that the suspension of face-to-face classes and social distance triggered a series of thoughts, feelings and attitudes in the teachers that deserve to be highlighted. In this approach, for a better organization of this categorical set, two categories were structured: a) psychological traits and b) attitudes.

Psychological Traits

The state of anxiety, worry and anguish were words that were repeated many times by most of the participants, as well as how they feel about missing the face-to-face contact with the students. In addition, terms that reveal fear, insecurity, fright, caution, discomfort, uncertainty, confusion, reflection, and impotence were also mentioned by the teachers. Attention is drawn to statements that teachers feel uncomfortable, that they are tired, burnt out, exhausted, stressed, pressured, overwhelmed, tense, depressed, irritated, feeling bad, frustrated, bored and sad, which points to the possibility of that the psychological and emotional health of the professionals have been affected by the situation experienced, therefore, they deserve attention and care. Faragher, Cass and Cooper (2005) state that there is an intense association between low levels of job satisfaction and mental and psychological problems, such as burnout, low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety. The following expressions represent some of the teachers’ responses:

Anxiety and concern take care of all preparation for classes, not all content we can work online, which also generates frustration (KindergartenPrivate5). I’m tense and anxious! Everything is new! Isolation, the way of working, living with imminent danger! (MiddlePrivate15). My feeling is that I miss the students, the classroom, and the school life. And, also of concern and fear in the face of the situation experienced by the country (KindergartenPrivate51). I feel exhausted and trying to maintain a less stressful routine as possible (ElementaryPrivate61). I feel distressed daily [...] (HighSchoolPrivate71). Emotionally tired and professionally drained (ElementaryPrivate131). Very afraid, insecure, and hard work (ElementaryPrivate150). It is a stressful and very tiring situation. [...] (ElementaryPublic153). There is a feeling of insecurity and concern about the situation and its possible consequences. Together, there is a physical and mental overload [...] (Middle-HighSchoolPrivate182). I am very afraid of everything that is happening. The pandemic brought fears, challenges, and uncertainties. I have a compulsive fear of returning to work, for people and cleanliness [...] (ElementaryPublic195).

Based on what was exposed by the vast majority of participants, in all educational stages of this study, it is observed that the results present thoughts and feelings that generate discomfort. When considering current issues in teacher training and performance, Moreira (2001) defends the articulation between interiority and exteriority, or, in other words, between the teacher’s relationship with his own self and his external relationship with the world. Saraiva, Traversini and Lockmann (2020, p. 2) emphasize that Covid-19 “[...] breaks out abruptly to remind us of human fragility”, which triggers fears such as unemployment, hunger, violence, of a becoming that opens without guarantee, of the certainty that we will not be what we used to be. Dussel (2020) clarifies that the particular affective climate is associated with surprise, anxiety and mixes variables of pessimism and optimism.

Attitudes

It was noticed that the teachers, despite the difficulties, were adapting to the situation of social detachment. The study revealed new learning with the suspension of face-to-face classes and the adoption of different means and working resources for online classes. In this direction, the different tools and methodologies emerged as challenges and discoveries. The need to reinvent itself, to re-signify practices and to encourage creativity were reinforced in the educational routine, in pandemic times. In this context, the teachers stated that the demands have increased and that they are working much more than usual, which caused the overload due to the greater effort and dedication. Gasparini, Barreto and Assunção (2005) mention the validity of studies aimed at understanding the inadequacy between the proposed and implemented educational changes, as well as the reality that workers face. The existing contradictions can be the source of the exposure to risk factors for illness in the category of education professionals. The following are examples of phrases selected by clipping the messages:It is quite complicated, because from night to day I became a YouTube teacher. On the other hand, I am learning new ways to teach, because I like challenges (HighSchoolPrivate32). It is a new situation, in which many mistakes and successes are made. But in a general panorama it has been a time of discovering tools and methodologies, as well as applying activities that would not be so successful in face-to-face classes (Middle-HighSchoolPrivate45). I confess that we are in difficult times, there were many charges initially. I had to adapt and use tools I was not used to. I think on the positive side, I was ‘forced’ to learn many things (Kindergarten-ElementaryPrivate-Public47). It is a totally innovative situation! I had to learn and adapt to this, if we can say so, New Age of World Education (HighSchoolPrivate66).

Attitudes related to beliefs were also noted in the content of the data and deserve to be highlighted. Terms such as hope, faith, perseverance, gratitude, and positive thinking are examples of greater recurrence. According to Pátaro (2007), it is possible to state that the subject has certain beliefs and tends to act according to them, starting to think and see the world through them. Here are some pronouncements:

Hopefully, as this period of isolation will pass (MiddlePrivate154). I have been trying to maintain tranquility through Faith (HighSchoolPublic147). Always putting God in front of everything to help us overcome this pandemic (ElementaryPublic-Private152). Every day, I have been looking for readings and prayers to calm my inner self. I have kept hope and faith. A feeling of gratitude for life too (Elementary-Middle-HighSchoolPrivate77).

The results of studies by Melo et al. (2015) showed that religiosity and spirituality correlate with quality of life and coping in adverse situations. In this panorama of uncertainties, the importance of support aimed at the psychological well-being of teachers is emphasized. Saraiva, Traversini and Lockmann (2020) state that insecurity, the need for quick adaptations, the invasion of the home by work, anxiety about the sanitary and economic conditions in the pandemic scenario are causing teachers a state of exhaustion.

Challenges in Remote Teaching

The statements of the teachers associated with the compromised relationships between those involved in the educational process were highlighted: teachers, students, and families. In this regard, the emphasis on communication and information technologies in education remotely triggered important provocations, linked to the categories: a) relationships and b) domains of digital technologies.

Relationships

Difficulties in mobilizing, achieving attention and motivation in coordinating the participation of all students in online classes have recurrently appeared in the analysis of the results. Then, there were also statements that show the lack of understanding and recognition of teachers by families, as well as their unpreparedness in supporting students. It is also considered that the restriction of eye contact, feedback from students to teachers and from teachers to students were reported as adversities in the context of the virtual classroom. Brait et al. (2010) state that the teacher-student relationship encompasses all dimensions of the teaching-learning process that takes place in the classroom. In this core, it was perceived, through the analyzed phrases, challenges and losses caused by physical distance, including the relationship with the families of the students:

It is difficult to reach all students, motivate them and maintain a good pace of content (HighSchoolPrivate02). Parental acceptance, in fact, prejudice. There are reports that we are only fulfilling the contract or that what is proposed is very bad ... And then, on the contrary, we are working hard so that the children have quality content (KindergartenPrivate05). Absence of visual connection on the monitoring of students (HighSchoolPrivate06). Not having feedback from students, as in face-to-face classes (HighSchoolPublic70). The big challenge is to provide students with an interactive, enjoyable, and attention-grabbing activity (KindergartenPrivate55). I like to see the eyes shine or even show disinterest! I like technology, but I love people! Not looking into my student’s eye, for me, is a challenge (Elementary-Middle-HighSchoolPrivate77). It does not bring a complete perception of the message I sent them. It bothers me (HighSchoolPrivate87). I love to observe my students’ reactions during classes, which makes online classes unfeasible (MiddlePublic-Private86).

It becomes evident that the teacher-student relationship was impacted by the change in the format of the face-to-face classes to the remote classes. Brait et al. (2010) point out that the teacher/student relationship, in the middle of the teaching-learning process, depends, fundamentally, on the environment, on the empathic relationship between the teacher and the students, on the ability to listen, reflect and discuss the students’ level of understanding. It is noteworthy that, although there is the possibility of interaction through digital technological means, it does not seem to be satisfactory in Educação Básica, due to the fact that it restricts the attentive eye of the teacher and limits practices that strengthen the participation and understanding of the subjects involved. Ferreira and Barbosa (2020) consider that, in the midst of the chaos, teachers and students who manage to work remotely expect the meeting, the hug, the looks.

Digital Technologies Domain

Learning to cope, to adapt to the dynamics of online classes was repeated by the participants as a challenging situation, as well as the lack of time for training, formation, and guidance in the preparation of materials and/or remote classes. In particular, the lack of equipment, an adequate environment for classes, the production of videos and the exposure of personal image emerged as related notes that were difficult for teachers, which seems to have corroborated the insecurity reported by some participants. The instability of the connections and the consequent difficulty in remote access were also mentioned:

First, having a good Internet and then working on the content in an attractive way to students. (Kindergarten-ElementaryPublic67). The difficulty of recording videos. (KindergartenPrivate162). Use the video tools (KindergartenPrivate59). Adequate space with light, silence and tranquility and Internet stability (Middle-HighSchoolPrivate145). Noises at home like TV on, parents talking, phone ringing, students with difficult access (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private03). It is still difficult to find intimacy with the practice of video classes (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private19). Adapt and learn in a timely manner the tools and their functions. The exposure of my image (KindergartenPrivate20). Understand the mechanism of each platform, as they have particularities that make the work tiring (HighSchoolPrivate38). Get in touch with new tools and learn quickly when needed (HighSchoolPublic-Private50). Learn in record time the use of different platforms (HighSchoolPrivate63).

Gadotti (2000), when discussing the current perspectives of education, affirms that the school is challenged to change the logic of knowledge construction and that, in this direction, young people tend to adapt more easily than adults to the use of the computer, because they were born in this new culture, the digital one. The author also stresses that new technologies have created spaces of knowledge and that the school needs to be a center of innovation. On the other hand, he points out that a future for humanity cannot be imagined without teachers. In this sense, the importance of training education professionals is underlined so that digital technologies can be used as effective resources, without the teaching mediation losing its real value in society and in face-to-face interactions with students. Morgado, Sousa and Pacheco (2020, p. 5) recognize “[...] the inestimable contribution that technologies have made, both as a life support and as a mainstay of relationships”, but do not discard the “[...] the possibility that all this phenomenon will slide into an even more technology-dependent future”.

Learning Process Assessment

The National Guidelines to guide schools in Covid-19 pandemic times (Brazil, 2020b) suggest that the evaluations consider the actions of reorganizing the calendars of each education system before the new schedules for large-scale evaluations are established. The document also stresses that it is important to ensure a balanced assessment of students according to the different situations that will be faced in each education system, ensuring the same opportunities for everyone who participates in assessments at the municipal, state, and national levels. The Guidelines propose that the evaluations and exams for the conclusion of the 2020 school year for schools consider the curricular content actually offered to students, considering the exceptional context of public calamity, in order to avoid an increase in failure and dropout rates in Elementary, Middle and High School.

It can be seen from the guidelines of the Guidelines that the quantitative aspect seems to preponderate the qualitative, no matter how much attention is paid to the period of social detachment and the assurance of the same opportunities for the participation of all students in the assessments. It should be noted that if difficulties were already noticeable in guaranteeing opportunities for all students, considering the social inequalities that are constant in Brazil, the more challenging it seems to be in pandemic and remote teaching times, students’ access to digital technologies and the Internet, which enable the possibility and the right to the effective participation of students in conducting assessments, is made feasible.

It is emphasized that, in the research results, three evaluative aspects were dimensioned as categories: a) qualitative; b) qualitative and quantitative; and c) quantitative.

Qualitative Aspects

The observation of commitment, participation by audio and/or chats, the doubts expressed by students in online classes and the answers to questions asked by teachers during these classes were listed, repeatedly, as qualitative indicators in the evaluation process. It is added that the return of the activities proposed to the students was also mentioned, such as: the works, the videos recorded by the students, the exercises, and the questions of the textbook. According to Barreto (2001), qualitative assessment values the learning process and focuses on the possibilities of creating conditions for the school to work, differently, with the diversity of students. It is also noteworthy that the teachers stated that it is important to consider, in the conduct of the evaluation process, the feelings and experiences of the students in the context of social distance and remote classes:

Jobs and activities that students do at home and forward by email (HighSchoolPrivate04). The most effective way at the moment, I believe it is the student’s participation during online classes, as well as the activities sent by the platform (Kindergarten-ElementaryPublic67). Through forums and chats (Elementary-Middle-HighSchoolPrivate77). Through participation, asking questions and carrying out proposed activities (HighSchoolPrivate21). They are moments of conversation, chat, and exchange of experiences. We are concerned not only with the contents worked on, but also with the children’s feelings and experiences during this period (ElementaryPrivate23).

Feedback from students and parents emerged as an important return to the qualitative assessment process. A group of teachers in early childhood education and early years of elementary school claimed that it is not possible to assess students in this age group from a distance. Another group of teachers, however, reported that records of photos and videos taken by the children, with the help of their parents, were considered in the evaluative observation:

Through video and photos of the students’ activities, they demonstrate that they really learned and did the proposed activity. I can comment on the mistakes and successes and the student corrects them if necessary (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private45). At the end of each day, we have feedback from each responsible person, through a message, video, or photo (KindergartenPrivate111). We have the support of those responsible for this process, since the students are very small (ElementaryPublic-Private157). In Kindergarten, the process is done through observation registration, since this interaction is not possible in this context, there is no learning assessment (KindergartenPrivate170).

The Base Nacional Comum Curricular guides, in relation to Kindergarten, that the educator’s work comprises the set of practices and interactions that guarantee the plurality of situations and promote the full development of children (Brazil, 2017). It can be seen, through the phrases written by the teachers participating in the research, that the evaluation process for Early Childhood Education is even more committed to the emerging situation experienced, because, despite the efforts that teachers and families make at a distance to achieve the desired objective, mediations and face-to-face experiences make all the difference in the integral development of children.

Qualitative and Quantitative Aspects

It was noted, according to the statements of the teachers, greater constancy in the evaluation of the students considering both the qualitative and the quantitative approach, according to the following excerpts:

I have been asking for papers to be sent by e-mail, I do activity in the online classes with them, of record or orally, which I score. We are also using Google Forms to assist with bimonthly assessments (Kindergarten-ElementaryPrivate47). The process has taken place based on the participation of students via audio and chat platforms in a continuous assessment. Also, according to guidelines from school institutions, evaluations have been used through activities, tests and studies conducted online (HighSchoolPrivate180). Oral questions, didactic material exercises and evaluation by Forms. Spontaneous feedback during classes and simulated assessments on the Moodle platform. We tried to evaluate the entire route, but the institution demanded a formal ‘evaluative activity’ made on Google Forms (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private169). At the end of each class, I propose small questions and a bimonthly assessment has already been carried out through Forms (HighSchoolPrivate142). Participation in class, work, activities, and exam through Google Forms (Middle-HighSchoolPrivate126).

Barretto (2001, p. 63) clarifies that “[...] the emphasis on the process and the general conditions in which teaching is offered becomes essential for educators, students and educational institutions themselves to take advantage of the potential redirector of evaluation”. The pandemic situation, in this premise, invites institutions and teachers, in the pandemic and post-pandemic, to reflect on the assessment and conditions for an effective mastery of knowledge by students, as well as for a training that extends to other spheres.

Quantitative Aspects

It should also be noted that the statements that the evaluations were or will be made strictly through digital forms with objective questions, which corroborates the purely quantitative evaluation aspect:

Objective evaluations posted on the platforms (HighSchoolPrivate38). For participation and quick tests by Forms (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private39). During this period, they do online simulations, assembled by me, and applied by the school platform (HighSchoolPrivate87). Through the forms of the platforms (HighSchoolPrivate63). Through Google Forms, we set up the assessment and students have a period of 15 days to respond (ElementaryPrivate196).

The appreciation of standardized results, according to Barretto (2001), values the learning product, largely uses quantitative resources and high technology in the evaluation of school performance. The author agrees that the exclusive appreciation of some cognitive aspects of the curriculum leaves aside important dimensions in the education of the student. It is noteworthy that, even with the national and world calamity scenario, the tradition of evaluating to quantify seems to be still present in school culture.

There was also a relevant group of teachers who stated that they had not started the evaluation process with the students, according to some examples below:

During the period of online classes, there will be no assessments (HighSchoolPublic209). We haven’t done specific evaluations yet (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private130). To date, we are not evaluating students (KindergartenPrivate55). There are no grade or participation assessments during this period (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Pri85).

Although the qualitative and quantitative postulations are recognized in the teaching and learning evaluation process, the practices presented by the teachers point to the need “[...] to resume the regulatory function and the emancipatory function of the evaluation from a new perspective” (Barretto, 2001, p. 63). Saraiva, Traversini and Lockmann (2020, p.17) emphasize that student evaluations, via remote activities, should be carried out by teachers without prioritizing only the competencies provided for in official documents, but increasing the visibility of what was experienced and learned in the time of a pandemic and social isolation. The authors also reinforce that the use of large-scale assessments, to verify the learning of students during the period of remote education, is connected to the “[...] culture of performativity that increasingly prevails in educational fields”.

Students’ Behavior

The Base Nacional Comum Curricular (Brasil, 2017) The base emphasizes training based on integral human development, which constitutes individuals capable of dealing with individual and collective challenges, valuing children and young people in all its dimensions: intellectual, physical, emotional, social, and cultural. The normative document emphasizes the importance of students being the protagonists in their learning and actively participating in the process of building, consolidating, and applying knowledge. In this sense, considering the behavior of students by the teachers’ insight is a relevant factor to be considered also in remote education. From the teachers’ presentations, two important categories of perceptions were considered: a) unfavorable and b) favorable.

Unfavorable Perceptions

The vast majority of teachers said they noticed students who were unmotivated, apathetic, and disinterested. The lack of commitment and/or immaturity were repeatedly mentioned, as well as the mention of the difficulty in focusing by students, due to distractions in the home environment. The little interaction/participation during the videoconference classes and the students’ anxiety also emerged from the content analysis:

Too much anxiety and too little concentration (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private03). A little apathy, discouragement, and a lot of tension (MiddlePrivate119). Some have been really interested, but most are not taking it seriously (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private105). Few interact, the impression that many are not participating (Middle-HighSchoolPrivate30). Students lack maturity to adhere to this new method (ElementaryPrivate93). Insecurity and disinterest in the face of uncertainties (ElementaryPublic-Private18).

It becomes evident that the school environment favors a greater focus on students and is more conducive to the organization and development of study habits. According to Moreira (2017), although we live in a moment of questioning the project of modernity and changes in the social, political, cultural, and epistemological contexts, considering the post-modern times, the school still plays an important social role, what justifies the valorization of the diverse subjectivities that cohabit inside, in the dissemination of school knowledge.

Favorable Perceptions

On the other hand, some teachers also reported positive perceptions and stated that students are participatory and committed to remote classes. They reported that, surprisingly, students have adapted well to the virtual environment:

Great acceptance of the model now offered (KindergartenPrivate111). They have adapted very satisfactorily (MiddlePrivate43). Most students and families are getting involved (Elementary-Middle-HighSchoolPrivate35). They show interest and try to participate in the best way possible (KindergartenPrivate51). They are very participative, connected, in general (HighSchoolPrivate32). I was surprised by their enthusiasm and participation (HighSchoolPrivate92). Surprisingly, I noticed that some students showed an increase in levels of proactivity (Kindergarten-ElementaryPublic-Private107).

Coelho (2012) reinforces the importance of the school, both in its physical structure and in relation to teaching practices, adapting to receive the new type of student, considered digital native. According to the author, these students, born from the 1980s, are endowed with a natural technological competence, which should be explored in the classroom. Therefore, it is up to the school education system to pay attention to this students’ potential, in order to optimize the learning in the institutions. After all, fundamental curricular crises of the previous century resulted from technological innovations (Morgado; Sousa; Pacheco, 2020).

Curriculum Development

The curriculum can be defined as “[...] a construction and selection of knowledge and practices produced in concrete contexts and in social, political and cultural, intellectual and pedagogical dynamics” (Fernandes; Freitas, 2007, p. 9). In this context, when reflecting on school, curriculum and teaching, Moreira and Kramer (2007) emphasize that we live in hypermodern times, in which we are witnessing not the death of modernity, but its conclusion.

According to Candau (2016), insurgent experiences that point to other forms of organization of curricula, spaces, times, teaching work, relationships with families and communities, as well as management and practice relationships, remain peripheral, are not adequately viewed, nor strongly supported. Morgado, Sousa and Pacheco (2020) emphasize that the curriculum, as an experience centered on the social individual, leads us to reflect on the role of curriculum decision makers in times of social confinement. In this sense, the pandemic context experienced underlines the necessary attention to the curriculum and its consequences. It is emphasized that two main categories were highlighted: a) adversities and b) continuities.

Adversities

Teachers stated that the emerging situation validates the need for flexibility and adaptations in the educational process. In this perspective, clarity and focus in relation to what is essential is important in restructuring the curriculum, which needs to be rethought, reflected, considering the present and the future, according to the study participants. The teachers also pointed out that the time and pace of classes, as well as the content, had to be reduced, which leads to the intricate questioning of which knowledge is most valuable in the dissemination of the curriculum (Pacheco, 2013), mainly in pandemic time (Dussel, 2020). For Macedo and Fragella (2016), the knowledge that would be most valid was, for a long time, one of the central issues in the curriculum field and, if some still defend this centrality, certainly, they do not do it with the same certainty that there is only one answer or that this response hovers above power relations. In this perspective, according to the reports of the participants of this research:

We had to adapt everything, from planning, activities, evaluations, school calendar, etc. (ElementaryPrivate14). It is necessary to adapt the curriculum to the new reality (MiddlePrivate15). The learning dynamics are totally different. The student’s need is not content. This he has on the Internet. What the student wants is to reflect on the existing content. Thus, the teacher has to change his class, making the student connect with new reasoning (Elementary-Middle-HighSchoolPrivate48). I believe that the pandemic forced us to relax the idea of a traditional contented education and with the sole objective of fulfilling programs (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private69). It required a complete redesign of the curriculum (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private39).

It is perceived that the reality experienced provoked important reflections and possible actions related to the development of the curriculum. According to Pacheco (2013), the centrality of the curriculum in educational activity is justified if it is synonymous with knowledge, with reference to a corpus of knowledge and values, socially and culturally recognized as valid. Morgado, Sousa and Pacheco (2020, p. 7) declare that the confinement caused by Covid-19 “[...] cannot create a state of isolation from the curriculum, because the curriculum is, in essence, a space for sharing”. Thus, the authors emphasize that a new curricular conceptualization will be essential, in which the domain of curricular studies should focus.

Continuities

For a representative number of teachers, there were no major changes in the curriculum with the suspension of face-to-face classes, only the adequacy of the means occurred. Also, they explained that only with a return to the classroom context will it be possible to have a better view. Silva (2010) states that the use of technologies in the teaching and learning processes corroborates the movement of integration into the curriculum of the repertoire of social practices of students and teachers typical of the digital culture experienced in everyday life. In this premise, Morgado, Sousa and Pacheco (2020) emphasize the need for a profound debate about the role of the curriculum and educational technologies for society. Here are some testimonials from the participants of this research:

I think that only after the pandemic can we have a real assessment of the influence of this process on the curriculum (Middle-HighSchoolPrivate126). We cannot yet measure the impact caused (HighSchoolPrivate21). There was no interference in the curriculum, only readjustments of planning and evaluative activities (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private82). There has not yet been any interference in the curriculum, we are following what was planned for 2020 (HighSchoolPrivate142). We will collectively think about curricular interferences after returning to school (ElementaryPublic148). I did not perceive interference, unfortunately (Middle-HighSchoolPublic190). Only at the end will we have this vision (ElementaryPublic-Private11).

Some participants declared nothing in relation to the curriculum, which can be reiterated by the fact that part of the sample works in the public school system, because, until the time of data collection, it had not yet adopted the remote education system, aggravating accentuated social asymmetries in the conditions of access to education. Moreira and Kramer (2007) highlight the tension that exists in the curricular process between two focuses: school knowledge and culture, emphasizing that the curriculum involves both understanding the everyday environment and committing to its transformation. In this direction, the pandemic scenario reinforces the importance of the reflection made by Ponce (2009) when questioning which world and which human being we want to have from now on. The authors Morgado, Sousa and Pacheco (2020, p. 2) add: “What curricular transformations occur before the need for social confinement?”

Expectations Related to Return to Face-to-face Classes

It was found a repetition of terms related to the fear in relation to safety and the difficulty to manage health issues in the prevention of the contagion of Covid-19, when returning to face-to-face classes. Most teachers expect this return to be as soon as possible, although it is difficult to imagine when and how it will occur. Professionals are convinced that it will be a moment marked by countless challenges and many said they believe it will not be soon:

Much longing and expectation to return as soon as possible, but, above all, with security for everyone. Very afraid to know how this time impacted children and family (KindergartenPrivate20). We will come back recognizing the new territory that was established with the arrival of the virus. I think that, effectively, the classes will only return in August or September. I believe it will be a very delicate situation (HighSchoolPrivate21). The possibility of physical contact, the discrimination of those who present some symptom of the disease, the number of students in the classroom. Anyway, it will be a time of great challenges for us, educators (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private37).

The teachers estimated that there is a greater appreciation of physical coexistence, human relations, and the teacher’s face-to-face work, on the part of the school community and society as a whole, when returning to classes at educational institutions:

This isolation may be responsible for a greater appreciation of the physical presence of the teacher, many parents are realizing the challenges that teachers face in a classroom (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private03). We had to learn to live away from people, we had to learn to look at the other, even at a distance, our attitudes directly affect the other, and that was never so clear at that moment (Kindergarten-Elementary-Middle-HighSchool13). The valorization of the human being as a fundamental point for learning (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private65). I believe that we are no longer the same, neither teachers nor students. We will arrive at a different school, which has experienced different proposals. We will be other people when we meet. Other children, other professionals, other parents (ElementaryPrivate14).

Participants stressed that some changes will remain and that these are necessary for innovation in teaching dynamics. However, they stated that it will take time for (re) adaptation, who are apprehensive about the emotional impacts, with the mental health of students and post-pandemic teachers. They are also concerned with welcoming back to school in schools. In this sense, they stressed the importance of listening and dialogue, even because they believe that there will be a big difference and lag between the levels of learning:

We will need an adaptation time and, mainly, listening to the students (HighSchoolPrivate04). Concerned with the emotional and health of everyone, especially us teachers, who are working under screens almost 12 hours a day (ElementaryPrivate12). I think that the normal, as we knew, will never exist again and, therefore, the technology applied to learning will be an effective reality in educational institutions (HighSchoolPrivate41). Concerned about the psychological state of the students (MiddlePrivate43). Children will need to understand the school routine again. They will need to feel welcomed and safe again in the school environment (KindergartenPrivate51). First, we do not know whether this return will be normal, I believe not. I believe that we will change a lot both in social life and in the use of new methodologies (HighSchoolPrivate63). I think everything is very lost, we do not know exactly what to expect, when and how it will all end (KindergartenPrivate72). If society does not understand that an adaptation period will be necessary to return to the classroom, this will be traumatic! (Middle-HighSchoolPublic-Private95).

It is noticed that new times, spaces, and school relations tend to be unveiled in the reorganization of classroom classes so that the subjects of the school community can (re)adapt in a safe and effective way. Dussel (2020) asserts that, in the face of the new world order or disorder, it is important to maintain balance and dream of another possible school, other ways of teaching, another link with knowledge and culture in school relations.

Final Considerations

This article sought to recognize and analyze thoughts, feelings, challenges, and perspectives experienced by teachers of Educação Básica in Juiz de Fora during the pandemic caused by Covid-19 and the consequent suspension of face-to-face classes in Educação Básica schools. The categories that emerged in this study converge with the questioning of Dussel (2020) when reflecting on the effects of the domestization of schools in intersection with pre-existing inequalities, with technologies and pedagogical practices.

The results of the present research pointed out that, while the institutions of the private education network were, in some way, offering education remotely, the schools of the public network had not yet initiated this action, which accentuates the scenario of educational inequalities in the city. Fears regarding the way the educational process will be developed in public schools were configured as problematic by the participating teachers. Ferreira and Barbosa (2020) point out that the precarious situation to practice remote teaching and access to this emerging teaching modality are added to the difficulties of students in the domestic environment, which further limits access to education.

The records made by the professionals showed a state of anxiety, concern, and anguish, culminating in the work overload in the situation experienced, which highlights the importance of support aimed at the psychological well-being of teachers. The difficulties in the adoption of new means, resources and methodologies by teachers reinforce the need for continuing education and greater support for professionals in the acquisition and use of information and communication technologies, without the mediation of teachers losing their real value in society. Saraiva, Traversini and Lockmann (2020) emphasize that the inclusion of technology in a technicist way tends to place teaching activity in the Era of 24/7 (twenty-four hours and seven days a week), without the separation between work and activity domestic. This premise points to the need to consider changes in the teaching profession and its meaning in the digital reality (Morgado; Sousa; Pacheco, 2020) to avoid the scrapping of teachers’ careers.

The limitation of the interaction between teachers and students was considered a major factor, including the absence of important feedbacks in the teaching-learning process. In this sense, physical presence in the school context was considered essential in Educação Básica. In addition, it is emphasized that school institutions will have to assess the impacts caused on the curriculum and its consequences. Morgado, Sousa and Pacheco (2020) emphasize that it is necessary to find meanings about the pandemic phenomenon experienced and analyze the consequences in the curriculum construction and in the personal and social development of human beings.

It is believed that, from now on, school education will undergo many transformations and reframings. In this direction, studies that consider Educação Básica in pandemic times, in other cities and states of the country, seem valid to think about the education of the future.

REFERENCES

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de Conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70, 2011. [ Links ]

BARRETTO, Elba Siqueira de Sá. A Avaliação na Educação Básica entre Dois Modelos. Educação & Sociedade, ano XXII, n. 75, ago. 2001. [ Links ]

BRAIT, Lílian et al. A Relação Professor/Aluno no Processo de Ensino e Aprendizagem. Itinerarius Reflectionis, Revista Eletrônica do Curso de Pedagogia do campus Jatái-UFG, v. 8, n. 1, jan./jul. 2010. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília: MEC, 2017. Disponível em: <http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_20dez_site.pdf>. Acesso em: 22 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº. 13.979, de 06 de fevereiro de 2020. Diário Oficial [da República Federativa do Brasil], Brasília, DF, Atos do Poder Legislativo, 2020a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Diretrizes Para Orientar Escolas da Educação Básica e Instituições de Ensino Superior. Aprovada no dia 28 de abril de 2020, pelo Conselho Nacional de Educação (CNE). Brasília: Ministério da Educação, 2020b. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão. Cotidiano Escolar e Práticas Interculturais. Cadernos de Pesquisa, Maranhão, v. 46, n. 161, p. 802-820, jul./set. 2016. [ Links ]

CHAER, Galdino; DINIZ, Rosa Pereira; RIBEIRO, Elisa Antônia. A Técnica do Questionário na Pesquisa Educacional. Evidência, Araxá, v. 7, n. 7, p. 251-266, 2011. [ Links ]

COELHO, Patrícia Maria Farias. Os Nativos Digitais e as Novas Competências Tecnológicas. Texto Livre Linguagem e Tecnologia, Belo Horizonte v. 5, n. 2, 2012. Disponível em: <http://periodicos.letras.ufmg.br/index.php/textolivre>. Acesso em: 21 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

DUSSEL, Inês. A Escola na Pandemia: Reflexões Sobre o Escolar em Tempos Deslocados. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 15, p. 1-16, jul. 2020. [ Links ]

FARAGHER, Brian; CASS, Monica; COOPER, Cary. The Relationship Between Job Satisfaction and Health: a meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Londres, v. 62, p. 105-112, 2005. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Cláudia de Oliveira; FREITAS, Luiz Carlos de. Indagações Sobre Currículo: currículo e avaliação. Organização do documento: Jeanete Beauchamp, Sandra Denise Pagel, Ariciléia Ribeiro do Nascimento. Brasília: MEC, Secretaria de Educação Básica, 2007. Disponível em: <http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/Ensfund/indag5.pdf>. Acesso em: 15 maio 2020. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Luciana Haddad; BARBOSA, Andreza. Lições de Quarentena: limites e possibilidades da atuação docente em época de isolamento social. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa v. 15, p. 1-24, jul. 2020. [ Links ]

GADOTTI, Moacir. Perspectivas Atuais da Educação. São Paulo em Perspectiva, São Paulo, v. 14, n. 2, 2000. [ Links ]

GASPARINI, Sandra Maria; BARRETO, Sandhi Maria; ASSUNÇÃO, Ada Ávila. O Professor, as Condições de Trabalho e os Efeitos Sobre sua Saúde. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 31, n. 2, p. 189-199, maio/ago. 2005. [ Links ]

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Métodos e Técnicas de Pesquisa Social. 5. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 1999. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth; FRAGELLA, Rita de Cássia Prazeres. Apresentação - Políticas de currículo ou Base Nacional Comum: debates e tensões. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 32, n. 2, p. 13-17, abr./jun. 2016. [ Links ]

MARCONI, Maria de Andrade; LAKATOS, Eva Maria. Técnicas de Pesquisa. 3. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 1999. [ Links ]

MELO, Cyntia de Freitas et al. Correlação entre Religiosidade, Espiritualidade e Qualidade de Vida: uma revisão de literatura. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, Rio de Janeiro, v. 15, n. 2, p. 447-464, 2015. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Decreto NE nº. 113, de 12 de março de 2020. Diário do Executivo, Belo Horizonte, Caderno 1, 2020a. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Decreto nº. 47.886, de 15 de março de 2020. Publicado pelo governador do estado de Minas Gerais. Diário do Executivo, Belo Horizonte, Caderno1, 2020b. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Deliberação nº. 18, de 22 de março de 2020. Belo Horizonte: Comitê Extraordinário COVID-19, 2020c. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Conselho Estadual de Educação, aos 27 dias de março de 2020. Orientações relacionadas à reorganização das atividades escolares. Belo Horizonte: Secretaria Estadual de Educação, 2020d. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Antonio Flavio Barbosa; KRAMER, Sonia. Contemporaneidade, Educação e Tecnologia. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 28, n. 100, p. 1037-1057, out. 2007. Edição Especial. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Antonio Flávio Barbosa; SILVA JUNIOR, Paulo Melgaço da. Conhecimento Escolar nos Currículos das Escolas Públicas: reflexões e apostas. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 17, n. 3, p. 489-500, set./dez. 2017. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Antonio Flávio Barbosa. Currículo, Cultura e Formação de Professores. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 17, p. 39-52, 2001. [ Links ]

MORGADO, José Carlos; SOUSA, Joana; PACHECO, José Augusto. Transformações Educativas em Tempos de Pandemia: do confinamento social ao isolamento curricular. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 15, p. 1-10, jul. 2020. [ Links ]

OMS. Organização Mundial da Saúde. Folha Informativa - COVID-19 (doença causada pelo novo coronavírus). Disponível em: <https://www.paho.org/bra/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6101:covid19&Itemid=875>. Acesso em: 7 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

PACHECO, José Augusto. Estudos Curriculares: desafios teóricos e metodológicos. Ensaio: avaliação e políticas públicas em educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 80, p. 449-472, jul./set. 2013. [ Links ]

PÁTARO, Cristina Satiê de Oliveira. Pensamento, Crenças e Complexidade Humana. Ciências & Cognição, Rio de Janeiro, v. 12, p. 134-149, dez. 2007. [ Links ]

PONCE, Branca Jurema. A Educação em Valores no Currículo Escolar. Revista E-Curriculum, São Paulo, v. 5, n. 1, dez. 2009. [ Links ]

SARAIVA, Karla; TRAVERSINI, Clarice; LOCKMANN, Kamila. A Educação em Tempos de Covid-19: ensino remoto e exaustão docente. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 15, p. 1-24, ago. 2020. [ Links ]

SILVA, Maria da Graça Moreira da. De Navegadores a Autores: a construção do currículo no mundo digital. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE DIDÁTICA E PRÁTICA DE ENSINO, 2010, Belo Horizonte. Anais... Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2010. [ Links ]

1In Brazil, in comparison with the American model, Educação Básica refers to: Educação Infantil (Kindergarten), to anos iniciais do Ensino Fundamental (Elementary School), to anos finais do Ensino Fundamental (Middle School) and Ensino Médio (High School). Therefore, we choose to translate Ensino Fundamental as Elementary and Middle Schools and we do not translate Educação Básica, keeping the use of the term in Portuguese.

2We do not translate Pedagogia as Pedagogy, keeping the term in Portuguese, considering that, in Brazil, the Pedagogia course allows the exercise of teaching in Educação Infantil and anos iniciais do Ensino Fundamental- in American system, the Bachelors or Master’s Degree in Early Childhood and Elementary Education is a formation requirement for working in Kindergarten and Elementary School levels.

Translated by Sabrina Mendonça Ferreira

Received: July 08, 2020; Accepted: January 27, 2021

texto en

texto en