Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Realidade

versão impressa ISSN 0100-3143versão On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.46 no.3 Porto Alegre 2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236116975

THEMATIC SECTION: CAPITALISM, STATE, AND EDUCATION: THE LIMITS OF THE CAPITAL

Class, Race and Gender Relations in the Constitution of Intellectual Disability

IPontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP), São Paulo/SP – Brasil

IIUniversidade Pitágoras (UNOPAR), São Paulo/SP – Brasil

The aim of this article is to analyze the relationship between intellectual disability and class, race and gender. For this purpose, we used data from the Brazilian demographic census (IBGE, 2010), organized into three categories: a) people without disabilities; b) people with other disabilities; and c) people with intellectual disabilities. The most expressive result pointed out that there is a close relationship between income levels and the proximity the curves of the three categories showed. The higher the income level, the closer the curves are, demonstrating how decisive the impact of race and gender is on the living conditions of people with intellectual disability.

Keywords Intellectual Disability; Social Class; Race; Gender; Social Indicators

O objetivo deste artigo é analisar a relação entre deficiência intelectual e classe, raça e gênero. Para tanto, utilizamos dados do censo demográfico brasileiro (IBGE, 2010), organizados em três categorias: a) pessoas sem deficiência; b) pessoas com outras deficiências; e c) pessoas com deficiência intelectual. O resultado mais expressivo apontou que existe uma estreita relação entre os níveis de renda e a proximidade que as curvas das três categorias apresentam. Quanto maior o nível de renda, mais próximas são as curvas, demonstrando o quão decisivo é o impacto da raça e do gênero nas condições de vida das pessoas com deficiência intelectual.

Palavras-chave Deficiência Intelectual; Classe Social; Raça; Gênero; Indicadores Sociais

Introduction

This article aims to analyze the relationship between intellectual disability and class, race and gender through Brazilian social indicators (IBGE, 2010). We are aligned with the theoretical perspective that the identity of individuals is constituted by their social trajectories and class origins, their ethnic-racial belonging and gender (Ferraro, 2010).

The choice of a specific disability – intellectual – is because, in an increasingly complex modern industrial society like ours, which is also increasingly based on intellectual capacities rather than on physical strength, intellectual disability, among all other disabilities, is the one in which the medical-psychological perspective, still hegemonic in special education, reduces the totality of the subject to their disability only (Skrtic, 1996). This is because, although the social consequences affect everyone, with the technological resources we have available today, there is a high probability of more accurate diagnoses in relation to sensory, motor and even serious intellectual impairments.

However, disabilities somehow linked to cognitive and psychic aspects, but not subject to such objective determination, and those which deviate little from normality, such as mild intellectual disability, show the enormous possibility of medicalization of unappreciated social patterns, which end up justifying the problems of the educational and social systems themselves (Bueno, 1993, p. 50-51).

A comprehensive and detailed study by The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2015, topic 15) on mental disorders in low-income children considers that the cause for the discrepancy in the incidence rates of intellectual disability (ID) in studies based on statistics (8.7-36.8 per 1000 inhabitants) is due to

[…] variation in the inclusion of mild ID (often defined to include individuals with IQs in the range of 50-70 and deficits in adaptive behavior). While the prevalence of serious ID (IQ <50 with deficits in adaptive behavior) in the United States and other developed countries is consistently found to be in the range of 2.5 to 5 per 1,000 children, that of mild ID ranges from as low as 2 to more than 30 per 1,000. The risk of mild ID is highest among children of low socioeconomic status.

However, it cannot be said that the relationship between disability and social environment has not been addressed in studies on special education. Since the time when American studies on this issue were hegemonic in Brazil, there have been one or more chapters dedicated to the social consequences of disability, as it can be seen in the handbooks of Dunn (1971), Telford and Sawrey (1978), Kirk and Gallagher (1979) and Cruickshank and Johnson (1979), translated into Portuguese and widespread in the professional and academic fields of special education, in the 1970s and 1980s1.

However, these works analyzed the social consequences of disability, in relation to socialization and education processes. These works involved essential but not sufficient issues, since they did not address the construction of the social identities of these individuals. This led Skrtic (1996) to carry out a dense and detailed critical review of what he called theoretical knowledge of special education.

In his article, the author contested the criticisms, made until then, about the theoretical knowledge of special education, which characterized this production under three major keys of analysis: atheoretical theory, which had no scientific basis; confounded theory, which considered this production confused biological bases (measured by symptoms) with psychological bases (measured by deviation from the normal pattern); and a third, wrong theory, which considered the knowledge produced to be inaccurate because the medical and psychological bases on which it was based were inadequate to support qualified practices of social deviation.

For him, however, none of these criticisms were sustained, because the bases of medicine and psychology are absolutely necessary to produce knowledge. Alone, they’re insufficient, insofar as the limitations posed by disabilities demand, in addition to these bases, a sociological one.

Therefore, even if not consciously, the scientific production of special education was based exclusively on the first two theoretical bases, in accordance with the positivist theory of knowledge: a professional performance with the use of instruments and skills that were based on postulates and procedures of applied theory (medical and psychological diagnoses), which, in turn, were the result of unquestionable findings of the theoretical knowledge produced by medicine and psychology (Skrtic, 1996, p. 35).

It is interesting to point out that three years earlier, in our country, Bueno (1993, p. 46) agrees that there is a dominance of medicine and psychology in the scientific production on special education. He also considers that there was, indeed, a sociological basis, although unconscious: that of the relationship between normality and social pathology created by Durkheim (1983), in his rules of the sociological method. This is because disability was characterized by the deviation from abstract individuality: a) determined by the departure from the standard of biological normality (based on medicine) or the average of the population (based on psychology); b) that, according to these findings, defined the possibilities of socialization and education; and c) that is accomplished by the practical decisions adopted by the professionals of special education.

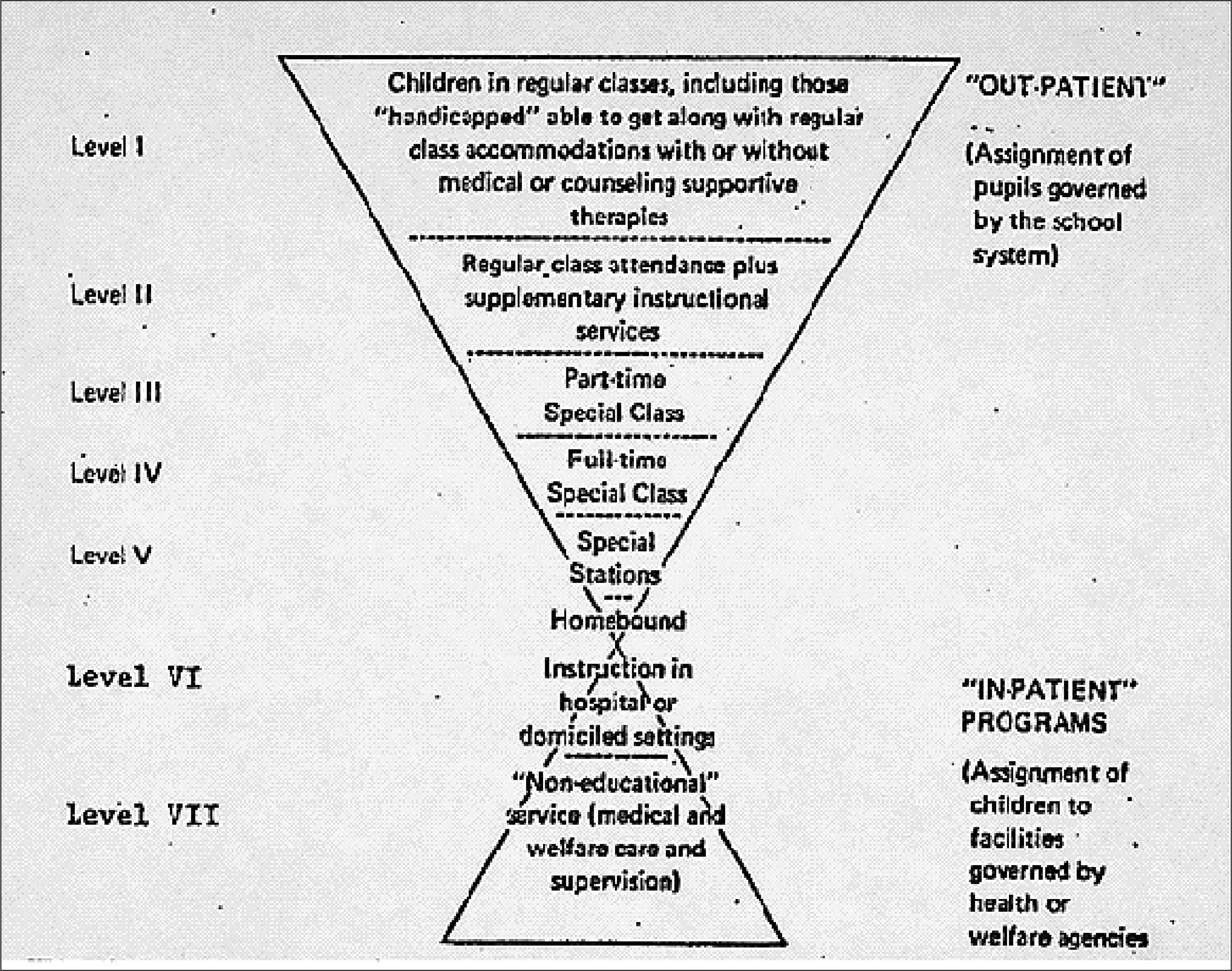

This standard was adopted in most countries and resulted in an educational service model named Cascade System, based exclusively on the standard deviation from normality index, as seen in Figure 1.

Source: Reprinted from Evelyn Deno, Exceptional Children, 1970, v. 37, p. 229-237. Copyright by the Council for Exceptional Children.

Figure 1 Cascade System of Special Education Service

Within this model, the more severe the disability, the greater the chance of being sent to segregated systems; and the milder the disability, the higher the chance of going to the common class.

Regarding intellectual disability, it is a fact that this system allowed the distinction of students with very distant degrees of cognitive impairment, favoring a more adequate service. However, regarding mild intellectual disabilities diagnosed by traditional standardized procedures, it produced paradoxical results:

on the one hand, in more qualified education systems and institutions, it is possible to verify, more and more, learning potentials that were not very evident when there was no pattern of differentiation;

on the other hand, it favored the spread of diagnoses of mild intellectual disability in students who had low school performance. Collares and Moysés (1996) called it medicalization of school failure, and this has contributed decisively to exempt schools and governments from the evils of elitist and selective educational policies.

This perspective, although subject to criticism, offered contributions to the development of special education, in particular to the improvement of some crystallized and even inhuman service procedures, which are still practiced today. However, it lacked the perspective of class, race and gender as constituents of the social identity of people with disabilities2. As stated by Skrtic (1996, p. 42), the criticism of the practical knowledge of special education has managed to produce some advances in the ways of serving students, but since “[...] it did not resort to a criticism of the theoretical knowledge of special education [...] it did not exert any influence on unconscious assumptions in the field”.

If a high-quality work, as Gonçalves’ thesis (2014)3, which, due to its own scope, is among those that focus on class (expressed by the relationship between schooling and students with disabilities in rural settlements), did not envision the possibility of exploring racial belonging, this lack of a racial perspective is even more evident in works focusing on issues of schooling at higher levels of education, whose selectivity is not only limited to students with disabilities4.

If the absence of class, race and gender relations has been a constant in much of the research on special education in our country, from the final years of the last century on, critical theoretical perspectives have emerged, based on the social sciences, and have been gradually exerting an increasing influence on the academic production of the area.

The first was based on studies of Oliver (1990; 1999) 5, who sought to develop what he called the Social Model of Disability as opposed to the individual model, based on Marxist political economy. According to him, his model would offer “[…] a much more adequate basis for describing and explaining experience than does normalization theory which is based upon interactionist and functionalist sociology” (Oliver, 1999, p. 1).

To this end, he established a critical argument about the power of medicine in characterizing what he called medicalization of disability, which placed the entire possibility of overcoming social limitations in the individual and disregarded the social barriers imposed by a political system based on capitalist productivity.

Based on statistical data that showed the majority of the world’s 500 million inhabitants with disabilities lived in precarious conditions6, social oppression was extended to all subjects with disabilities:

Therefore, the oppression that people with disabilities face is rooted in the economic and social structures of capitalism. This oppression is structured by racism, sexism, homophobia, ageism. It is endemic to all capitalist societies and cannot be explained as a universal cognitive process

(Oliver, 1999, p. 4).

In this sense, by including all people with disabilities in the list of the socially oppressed, subsuming the conditions of class, race and gender to the hierarchically superior category of disability, this theoretical perspective precisely subverts the Marxist political economy perspective claimed to be based on7.

Contradicting this view, Skrtic (2014, p. 173) carries out a critical analysis of the educational reality of people with disabilities in the United States after the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)8, in 1990. According to him, this act would aim, on the one hand, to ensure the right “[…] to an appropriate education in the least restrictive environment” and, on the other, to reinforce the procedural possibilities of students and their families so that the responsible schools would comply with the above maxim.

However, the high rates of black and poor people diagnosed with disabilities and sent to segregated spaces in American public schools show the failures of this system, which “[…] oppresses students of economically disadvantaged and ethnic and racial minorities” (Skrtic, 2014, p. 176) – a situation for which he coined the term institutionalized injustice.

Regarding this aspect, Skrtic (2014, p. 185) contributes to the analysis of the relationship disability-social living conditions, as he demonstrates that those sent to segregated systems (schools and special classes) are predominantly “[…] poor, working class students, from ethnic and racial minorities”. This shows that the way in which special education was arranged in the United States, based on IDEA, did not enable a democratic reform in schools, but left “[…] the institutional sources of injustice intact” (Skrtic, 2014, p. 179).

In the Brazilian reality, there is also a field of similar tension about disability, which can be made explicit, for example, by the contrast between the theoretical perspectives of Skliar (1998) and that of Bueno (1993) and Bueno; Ferrari (2013).

Skliar (1998, p. 48) advocates against audism, that is, the oppression of the listening community over those with hearing loss. Audism operates through the historical imposition of the oral language as the basic form of communication in a society that includes the deaf community, whose natural form of communication would be the sign language9. In that way, he inaugurates in Brazil the perspective that was called socio-anthropological perspective of deafness.

Without getting into the linguistic argument of the defense of oral language versus sign language, since there is concrete evidence of the existence of a significant number of deaf people who make use of sign language, as well as deaf people who use and defend the oral language. What deserves to be critically analyzed here is the perspective of the oppression listener-deaf:

The fact of being a listener means having a chance of dominating and making deaf people subordinate in schools and education. Being a listener can begin with a reference to a hypothetical hearing normality, but it actually means being a speaker and being white, male, professional, healthy, normal, literate, civilized, etc. Being deaf, therefore, means being stigmatized by the hearing loss as not speaking and thus not being a man, being illiterate, abnormal, unemployed, dangerous, etc.

(Skliar, 1998, p. 48).

Although this author refers to the fact that hearing normality implies being a speaker, white, male, professional, healthy, normal, literate, civilized, when establishing the relationship of these marks with deafness, he shows that they are subsumed to it, since being deaf (regardless of the social position) “[…] is being stigmatized as not speaking, not being a man, being illiterate, abnormal, unemployed, dangerous”.

In contrast to the perspectives of both Oliver and Skliar, Bueno (1998) has long been pointing out the importance of overcoming the abstract way in which disability has been treated in the academic field. They are limited to the specificity inherent to it from an individual perspective, that restricted the possibility of analyzing socialization and schooling processes, expressed by the relationship between disability and social living conditions:

However, as a concept, like any knowledge about social phenomena, exceptionality is not a predetermined fact nor it is above social relations because, as a social phenomenon, it was built through the very action of men, always and necessarily being charged with an ideological sense

(Bueno, 1993, p. 31)10.

In that sense, Bueno and Ferrari (2013) argue that considering any deaf user of sign language as a member of the same community

[…] is to disregard the existence of a diversity of social and economic conditions, places of origin, racial belongings, sex, family and neighborhood environments, as well as schooling, professional activities and social trajectories. In other words, centralizing the entire argument in the visual-manual appropriation of meanings has the unquestionable consequence of putting in second place all these elements that constitute the identities of deaf people.

From there, they conclude that deafness constitutes the founding characteristic of the social identity of these subjects since they are all included in the same community, whether they are black, poor, poorly educated or white, rich, with a high degree of education. The community is composed by those who are characterized by the visual-manual appropriation of meanings, since they use sign language, regardless of their class, race and gender.

Finally, this article is aligned with the perspective that considers issues of class, race and gender mandatory in investigations about the socialization and education processes of students with disabilities because, as stated by Skrtic (2014), the prevalence of low-income students in this group shows class discrimination of current policies.

This discrimination, in the case of intellectual disability, is even more evident because, if we compare statistical data available in Brazil with studies of prevalence of this disability, we see its disproportionate representation. According to our last Demographic Census (IBGE 2010), in 2010 in Brazil, there was a population of 12,748,663 people with disabilities, out of a total population of 190,732,694. That corresponds to 6.7% of Brazilian population.

About ID, Pastoriza (2020) shows that about 10.7% of the people with disabilities would be diagnosed with intellectual disabilities, and a quarter of them would be placed within the age group corresponding to basic education. If we apply this line of reasoning to current data, we will find the following situation, in 2019, in Brazil:

total population: 210,147,125 people

population with disabilities (6.7% of the total): 14,079,857 people

population with ID (10.7% of the population with disabilities): 1,506,544 people

a quarter at school age: 376,136 people

Comparing these findings with those of the School Census (INEP, 2019), we can see that there were 645,849 enrollments of students with ID in basic education, which corresponds to 42% more than the most generous estimate.

Finally, if data about other types of disabilities are compatible with these estimates, the discrepancies presented above clearly show the disproportionate representation of students with ID, both in relation to the general population and to the total number of students with disabilities.

If we combine the disproportionate representation of enrollments and criticisms about the diagnostic processes these students go through (Patto, 1990; Collares; Moysés, 1996; Moysés; Collares, 2011), it becomes evident that ID diagnoses and low school performance overlap, which fundamentally befalls students from the lower classes11.

In view of these alarming percentages, the relevance of using statistical sources is verified, as they offer comprehensive data of a reality that unveils a problem about the identification and even about the social production of intellectual disability, which impacts all spheres of the lives of these subjects.

The Use of Statistical Data

To understand the relationship between class, race and gender in the constitution of the subject with intellectual disability, we used statistical data, since they enable a comprehensive analysis of the social situation and ways to measure it. For this purpose, we used data from the demographic census (IBGE, 2010), since, according to Jannuzzi (2012), this is a fundamental instrument for defining and implementing public policies, as well as absolutely necessary for their assessment by academic circles12.

Another aspect that justifies its use is the fact that the demographic census is the only public statistical source that presents socioeconomic data on Brazilians with disabilities. According to Santos (2020), information about the living conditions of these people is scarce, since the main statistical bases, such as the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD), do not explicitly present information about it.

Therefore, to obtain data on people with disabilities, we needed to build social indicators and elaborate graphs that would allow the comparison and analyses intended13. The initial difficulty in building the indicators for establishing relationships between disability, living conditions, race and gender, took into account Bueno and Meletti’s considerations (2011). According to them, we must be cautious regarding the use of data obtained through self-declaration, given that, except for ID, all other questions are not restricted to people with disabilities, as information was collected and organized according to the level of difficulty to see, hear and move around (cannot do at all, very difficult to do, somehow difficult to do or not at all difficult).

This collection procedure meant that, in the field of special education, regarding sensory and physical disabilities, only people who answered cannot do at all and very difficult to do were considered as having disabilities.

Among the studies that adopted these categories to build the disability indicators through the demographic census, we find the research conducted by Gonçalves (2014), who used this grouping to characterize the population with disabilities who live in the countryside, and that conducted by Santos (2020), who adopted this procedure to collect information on the living conditions of Brazilians with disabilities. Pastoriza (2020) also made use of this criterion to investigate the profile of students with disabilities that got into private universities through scholarships offered by University for All Program (PROUNI), implemented by the federal government.Due to the complexity in data organization, in the present study, we needed to use microdata from the 2010 Demographic Census, since they present raw data of the information collected, enabling the most diverse and complex crossings between variables, which would not be the case had we used only the synopses and other summary documents released by the Institute.

In this context, the present study gathered raw data into three categories - (i) people without disabilities; (ii) people with other disabilities’14; and (iii) people with intellectual disabilities - to cross them with (a) race15, (b) gender16 and (c) average monthly income17.

Intellectual Disability, Income, Gender and Race Relations

Our last demographic census registered a population of 190,755,478. Following the selection procedures indicated by special education researchers mentioned above, 15,751,259 Brazilians (8.3%) can be considered as having disabilities and 2,611,533 (16.6%) as having intellectual disabilities (73 people with ID out of 1,000 people).

While the total percentage of students with any disability in relation to the general population is quite compatible with the most reliable estimates, the incidence of intellectual disability (73 out of 1,000 people) far exceeds even the highest rates found in the study by National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2015). This means we must carefully analyze this incidence.

If, in the case of other disabilities, it may be questionable to include, for example, all those who find seeing very difficult to do in the list of the visual impaired, the situation is different in the case of intellectual disabilities, whose questions are explicit. It seems unlikely that family members would have affirmed there is a person with intellectual disability in their household because they consider them so. More likely, this is official information, provided by health or education services. That is, it seems to approach, in a much more precise way than other disabilities, the population diagnosed with ID by health and education professionals and services18.

Based on these data, we verified the need to analyze the indicators that present the crossing of social marks of race, gender and income with the categories of people without disabilities, people with other disabilities19 and people with intellectual disabilities. Therefore, the analysis of the social living conditions of the population with intellectual disabilities, as we propose here, based on data from the Demographic Census, should significantly approach the actual number of diagnosed people.

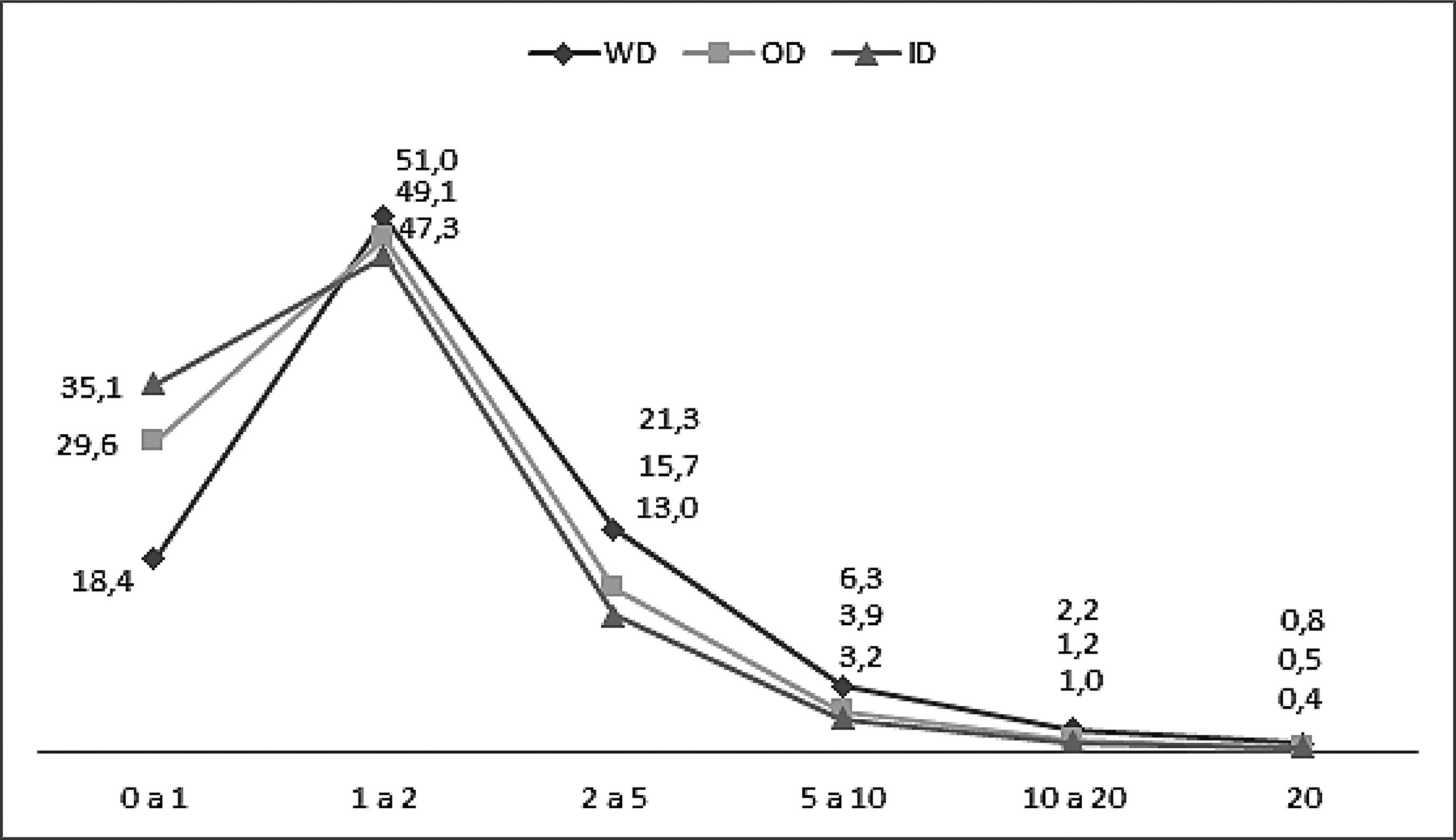

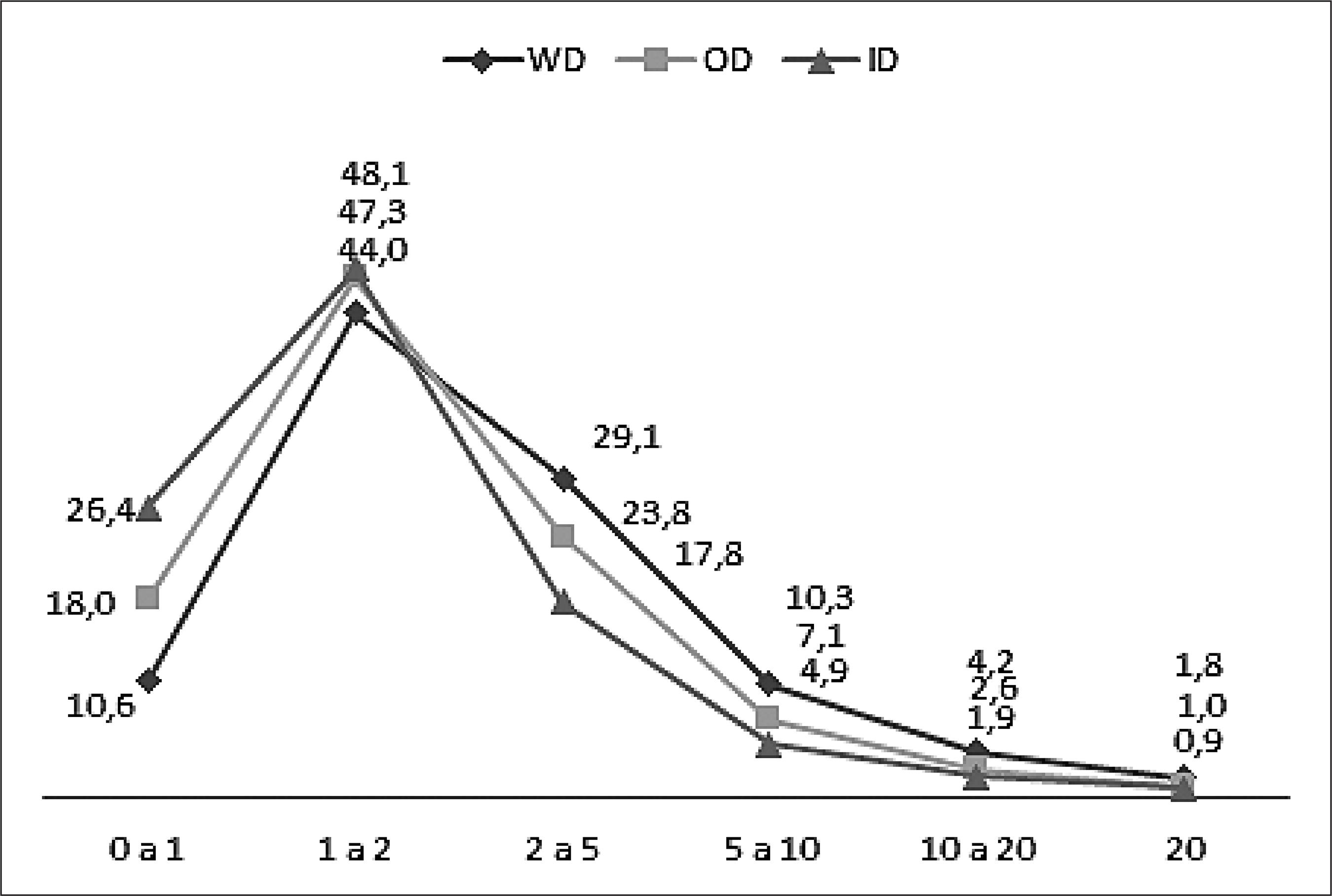

Graph 1 presents data on the monthly income indices of the population without disabilities (WD), with other disabilities (OD) and with intellectual disabilities (ID).

Notes: WD: People without disabilities; OD: people with other disabilities; ID: people with intellectual disabilities. 0-1: up to a minimum wage; 1-2: one to two minimum wages; 2-5: two to five minimum wages; 5-10: five to ten minimum wages; 10-20: ten to twenty minimum wages; 20: twenty minimum wages or more. Source: Based on IBGE (2010) microdata.

Graph 1 Monthly income of the general population: population without disabilities, population with other disabilities and population with intellectual disabilities (2010)

The first finding is that the curves of the three categories (without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities) are very similar. That is, the fact of having a disability does not seem to be a striking mark that falls more intensely among those who have, in particular, intellectual disability.

Even more interesting is the fact that the biggest discrepancy is found among the population with a monthly income up to one minimum wage, since only 18.4% of the population without disabilities falls into this range, against 29.6% of the population with other disabilities. The difference between the population in general and that with intellectual disabilities is even more striking: we find twice as many people with intellectual disabilities in this income bracket than people without disabilities.

The majority of the population falling into the bracket of one to two minimum wages per month is a true picture of social inequality in Brazil. These figures show that practically 70% of the population without disabilities survives on a monthly income of up to two minimum wages, and this percentage is around 10% higher among people with other disabilities and 13% higher among those with intellectual disabilities.

However, even though these data indicate that people with disabilities are more affected by poverty in Brazil (a country whose population in general is already vastly affected by it), it is evident that there is no way to deal with the issues of economic consequences on this population without including it in the broader scope of income inequalities in general.

From then on, as the curve moves up to a higher monthly income, there is a similar trend, which is the prevalence of better income levels within the population without disabilities, always closely followed by the population with other disabilities and a little behind is the population with intellectual disabilities.

Finally, data on the population with monthly income above twenty minimum wages defeat, in our opinion, any argument that states all people with disabilities can be considered oppressed or dominated. This is because, even among the population diagnosed with cognitive deficits, in a complex society that demands the development of cognitive capacities for the computerized society, the high monthly income rates of 0.5% of the population with disabilities compared to 0.8% of the general population once again shows that, on the one hand, the possibility of falling into this income bracket is greater among people without disabilities. On the other hand, the small difference between them proves the close and constant overlap between cognitive deficit and social position.

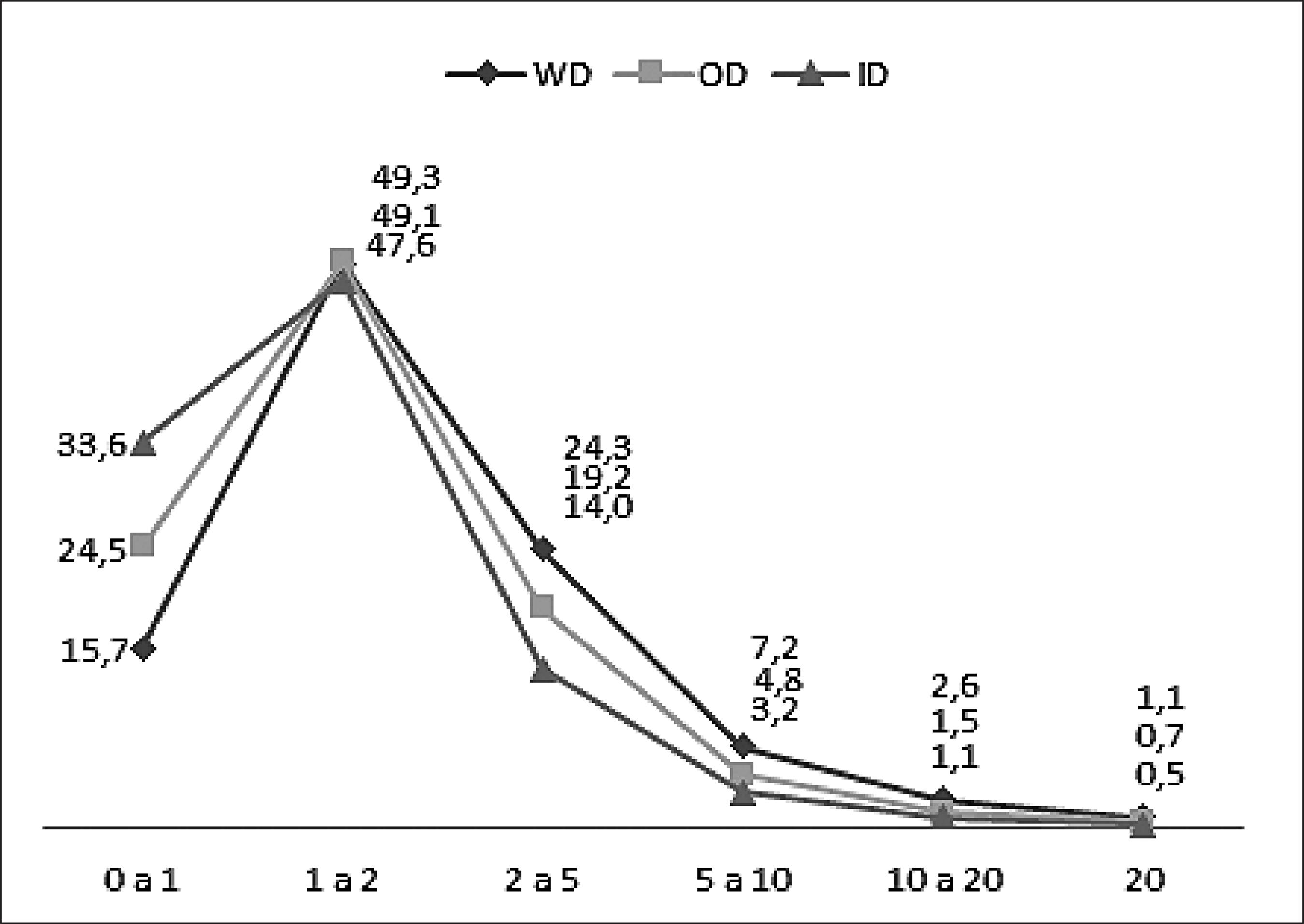

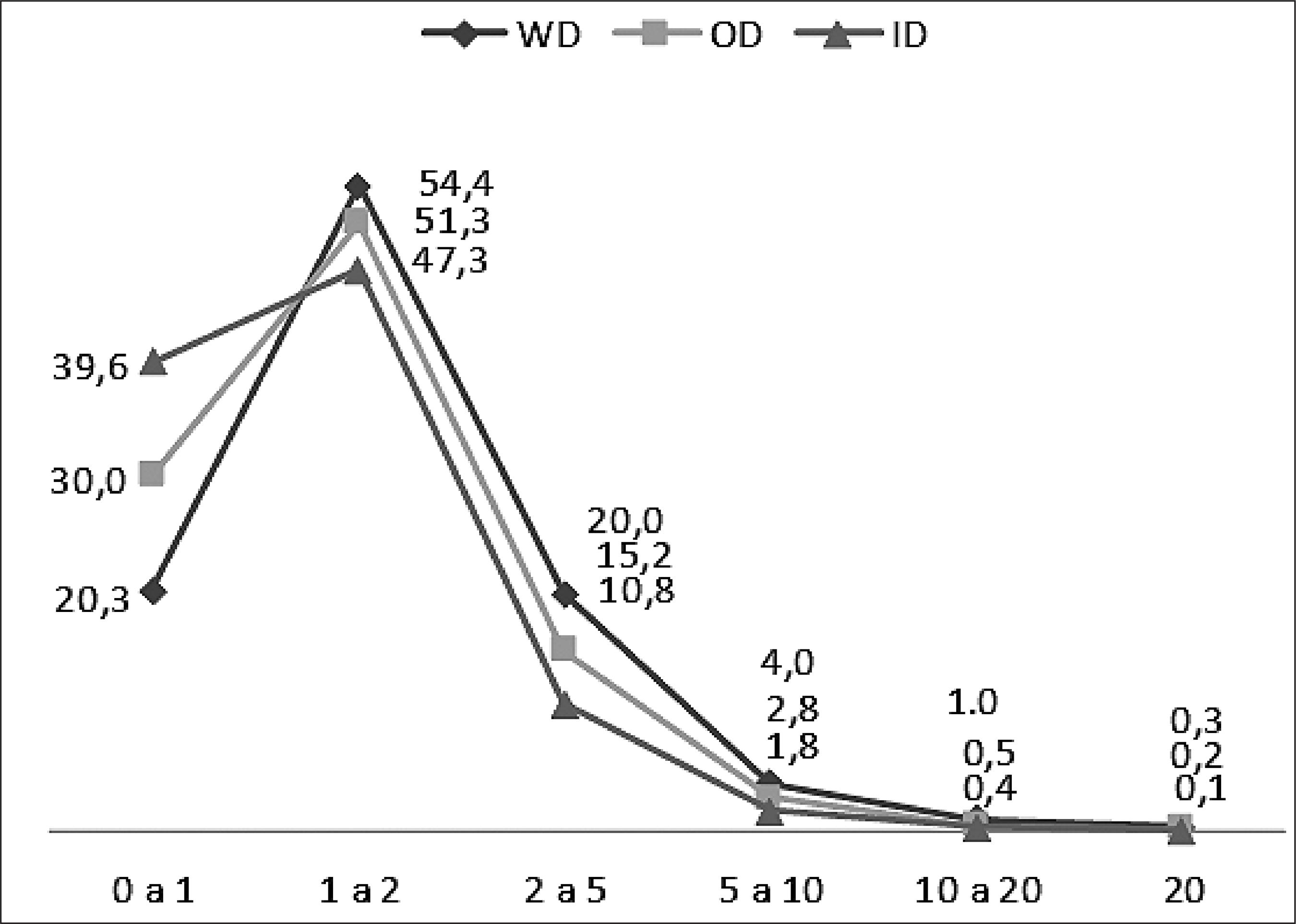

Graphs 2.1 and 2.2 present data on the monthly income indices of men and women without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities.

Notes: WD: People without disabilities; OD: people with other disabilities; ID: people with intellectual disabilities. 0-1: up to a minimum wage; 1-2: one to two minimum wages; 2-5: two to five minimum wages; 5-10: five to ten minimum wages; 10-20: ten to twenty minimum wages; 20: twenty minimum wages or more. Source: Based on IBGE (2010) microdata.

Graph 2.1 Monthly income of men without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities (2010)

Notes: WD: People without disabilities; OD: people with other disabilities; ID: people with intellectual disabilities. 0-1: up to a minimum wage; 1-2: one to two minimum wages; 2-5: two to five minimum wages; 5-10: five to ten minimum wages; 10-20: ten to twenty minimum wages; 20: twenty minimum wages or more. Source: Based on IBGE (2010) microdata.

Graph 2.2 Monthly income of women without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities (2010)

For all categories, there is a prevalence of women in the monthly income bracket up to one minimum wage, showing that all women (WD, OD and ID) have much greater chances to be forced to live on a low income than men.

However, it is also evident the discrepancy regarding the indices for women with intellectual disabilities in relation to the other two categories (OD and WD) is higher than that of men. That is, the mark of intellectual disability among women is more significant than that of men who have the same income.

In the immediately upper bracket (1-2 minimum wages) there is a balanced percentage distribution among men in the three categories (WD, OD and ID), like that observed in Graph 1. This proximity does not apply to data on female population, insofar as there is a significant difference of 6.3% between the percentages of women without disabilities (53.3%) and those with intellectual disabilities (47%).

In the total sum of the two income groups with smallest purchasing power (0-1 and 1-2), it appears that, although not very marked, the percentage of women in all three categories (81.7%) is higher than that of men in the same income range (73.3%).

However, compared to the percentages of the other income brackets, data for this one clearly shows that the mark of intellectual disability is stronger in the constitution of the female condition within the lower income population, both in comparison with men and with other categories (WD and OD).

The curves of income brackets above two minimum wages are like those shown in Graph 1. However, in all these brackets, women with intellectual disabilities are at a disadvantage both in relation to other women and to men in all three categories. Even considering the worse condition of women in these income brackets, it is evident that the higher the income bracket, the smaller the differences among the three categories and between men and women.

This data shows an overlap between the conditions of disability and gender in the possibilities of access to activities consistent with these monthly incomes, which are basic, yet not unique, elements for the quality of life within modern capitalist societies.

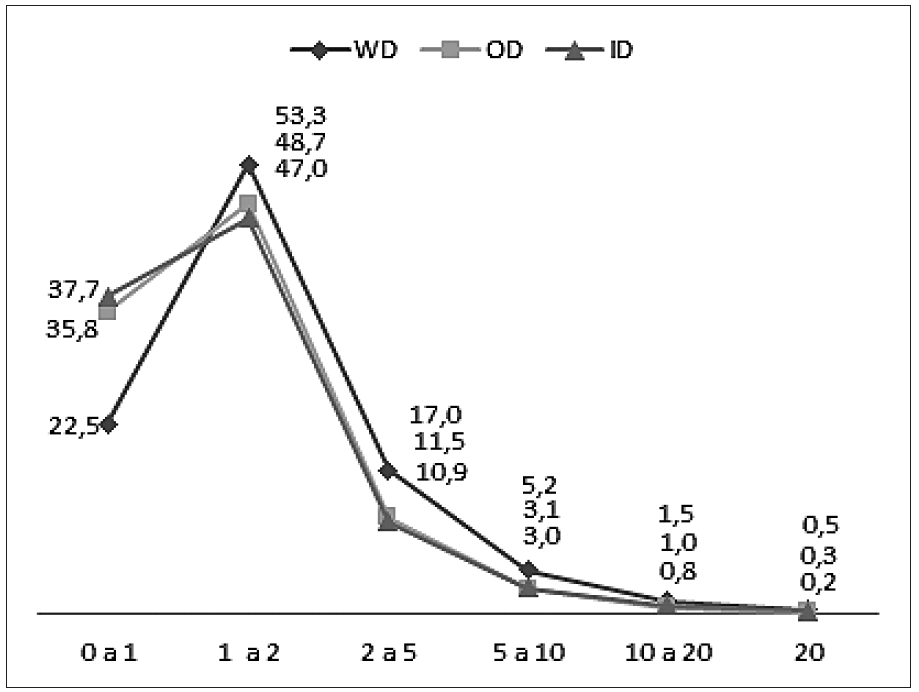

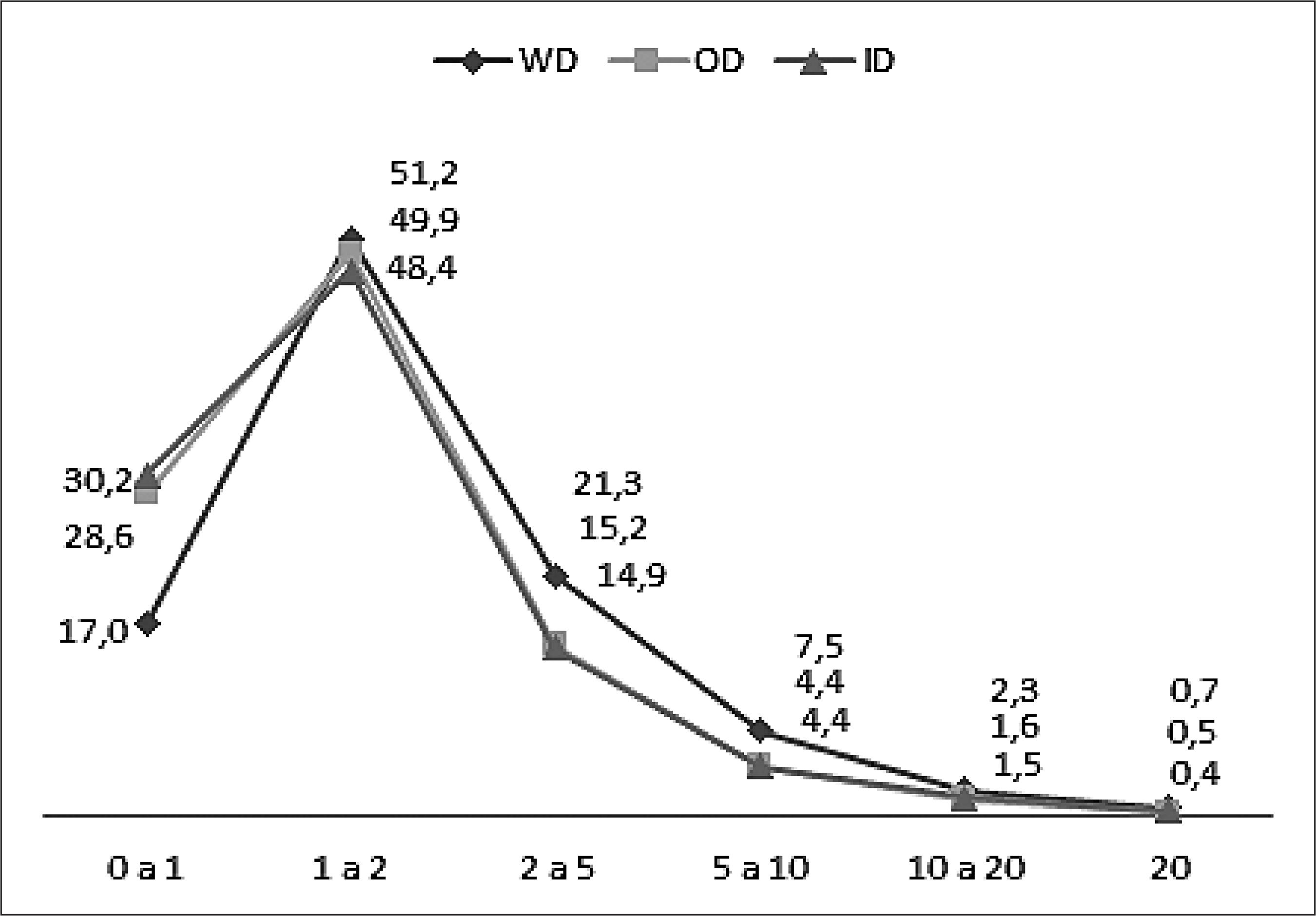

Graphs 3.1 and 3.2 present data on the monthly income indices of white and black men without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities.

Notes: WD: People without disabilities; OD: people with other disabilities; ID: people with intellectual disabilities. 0-1: up to a minimum wage; 1-2: one to two minimum wages; 2-5: two to five minimum wages; 5-10: five to ten minimum wages; 10-20: ten to twenty minimum wages; 20: twenty minimum wages or more. Source: Based on IBGE (2010) microdata.

Graph 3.1 Monthly income of white men without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities (2010)

Notes: WD: People without disabilities; OD: people with other disabilities; ID: people with intellectual disabilities. 0-1: up to a minimum wage; 1-2: one to two minimum wages; 2-5: two to five minimum wages; 5-10: five to ten minimum wages; 10-20: ten to twenty minimum wages; 20: twenty minimum wages or more. Source: Based on IBGE (2010) microdata.

Graph 3.2 Monthly income of black men without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities (2010)

The comparison between the curves of the graphs indicates the presence of significant differences in the living conditions between white and black men in all categories. Data on the monthly income bracket up to one minimum wage show an increasing disadvantage of black men in relation to white men: a 9.7% difference between white (10.6%) and black (20.3%) men without disabilities; a greater 12% difference between white (18%) and black (30%) men with other disabilities; and an even greater difference, of 13.2%, between white (26.4%) and black (39.6%) men with intellectual disabilities, demonstrating the influence race has on these indices.

Regarding the range of a monthly income up to two minimum wages, two significant distinctions can be seen:

the first refers to the relative position of the three categories in the two brackets because, while in the first (0-1 MW) intellectual disability has the highest incidence, followed by men with other disabilities and by those without disabilities, the order is completely reversed in the next bracket, for both white and black men; and

the second is that, although the difference in the three categories among black men follows the same order as that of white men, they are always greater among the former.

These two situations show that it only takes a small increase in the income bracket (from 0-1 to 1-2 MW) for the disability mark to be attenuated. However, even with a smaller difference, white men have a slight advantage in relation to their black peers.

In addition to that, if we add the indices of the two lowest monthly income brackets, we will find the same relative position among the three categories, but all of them with evident loss for Afro-descendants: 74.4% of blacks against 54.6% of whites without disabilities; 81.3% of blacks against 63.3% of whites with other disabilities; and 86.9% of blacks against 74.5% of whites with intellectual disabilities.

In other words, if these data show that both within the white and black male population the marks of disability add disadvantage to the monthly income, they also reveal the importance race has, since in the three categories the differences between blacks and whites are all around 20%, to the disadvantage of black men.

The shapes of the curves from the brackets of two to five minimum wages, although similar, clearly show that in all these brackets, the percentage levels of white men are higher than those of black men, showing that, although they have close income possibilities, race does have an influence on this distribution.

Regarding intellectual disability, the discrepancy of income possibilities of black men with intellectual disabilities is evident not only in relation to their white peers, but to black men in the other categories, much more forcefully in the lower brackets, that is, predominantly on poor black men.

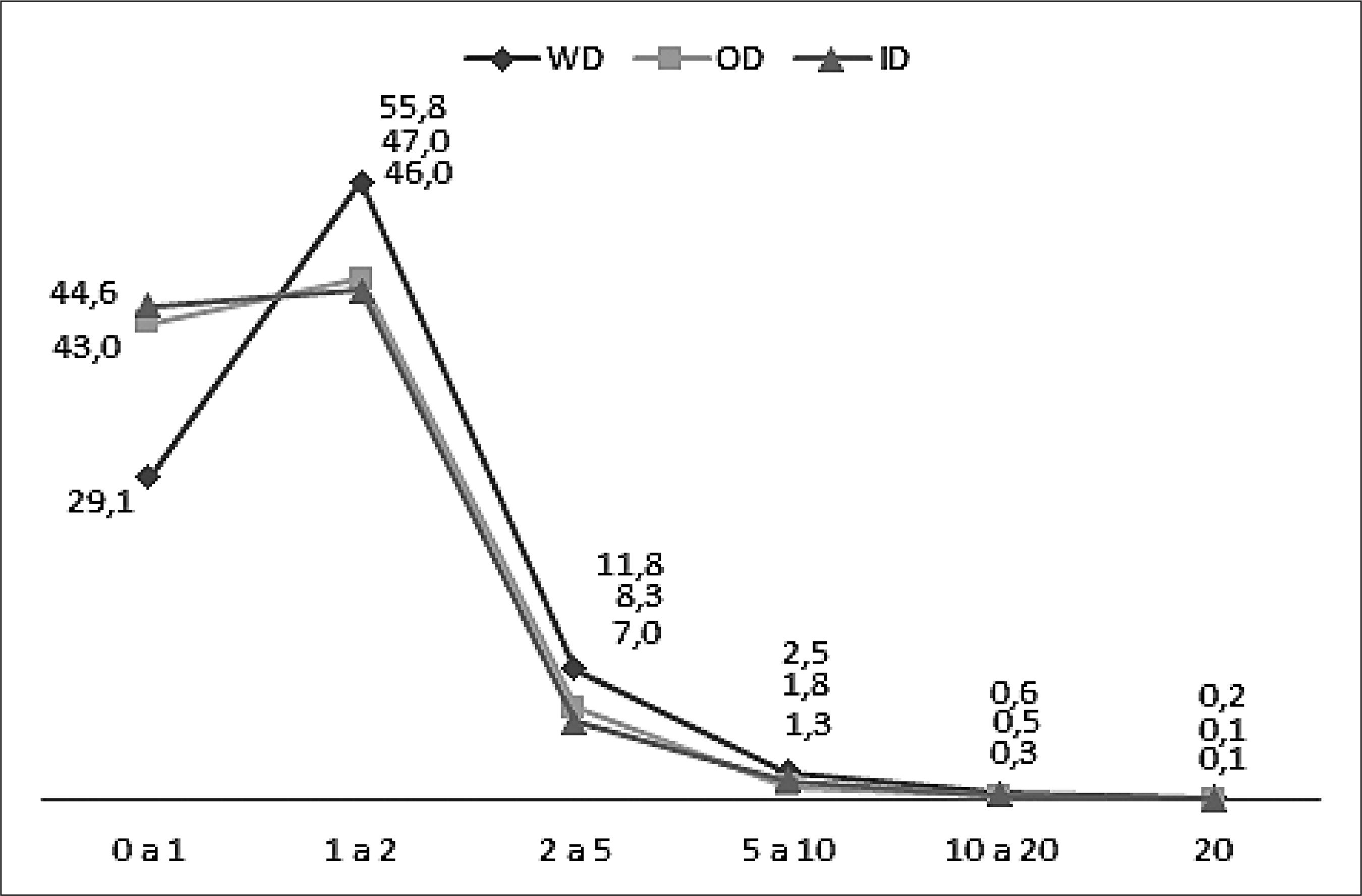

Graphs 4.1 and 4.2 present data on the monthly income indices of white and black women without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities.

Notes: WD: People without disabilities; OD: people with other disabilities; ID: people with intellectual disabilities. 0-1: up to a minimum wage; 1-2: one to two minimum wages; 2-5: two to five minimum wages; 5-10: five to ten minimum wages; 10-20: ten to twenty minimum wages; 20: twenty minimum wages or more. Source: Based on IBGE (2010) microdata.

Graph 4.1 Monthly income of white women without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities (2010)

Notes: WD: People without disabilities; OD: people with other disabilities; ID: people with intellectual disabilities. 0-1: up to a minimum wage; 1-2: one to two minimum wages; 2-5: two to five minimum wages; 5-10: five to ten minimum wages; 10-20: ten to twenty minimum wages; 20: twenty minimum wages or more. Source: Based on IBGE (2010) microdata.

Graph 4.2 Monthly income of black women without disabilities, with other disabilities and with intellectual disabilities (2010)

Data in these graphs reveal, first, that the percentage indices of black women are the worst so far, in any of the three categories and in any income bracket.

For the purposes of this article, it is enough to compare the monthly income situation of the population with intellectual disability, in the income bracket of up to one minimum wage:

Men with intellectual disabilities - 33.6% (Graph 2.1);

Women with intellectual disabilities - 37.7% (Graph 2.2);

White men with intellectual disabilities - 26.4% (Graph 3.1);

Black men with intellectual disabilities - 39.6% (Graph 3.2);

White women with intellectual disabilities - 30,2% (Graph 4.1); and

Black women with intellectual disabilities - 44.6% (Graph 4.2).

These data reveal that at the intersection of race and gender, the differences in monthly income are accentuated, since the smallest is between men and women. A discrepancy that widens when comparing black and white men, culminating in an even more expressive difference when comparing the monthly incomes between white and black women. It is evident, therefore, that the intersection of race, gender and intellectual disability has a decisive influence on placing this population at the bottom in terms of monthly income.

Regarding the second income bracket (1 to 2 MW), the following situation is observed: very small difference in the percentages of the three categories among white women, 1.5% difference between those with intellectual and other disabilities and 2.8% difference between women with intellectual disabilities and those without disabilities. Among black women, this difference is slightly reduced (1.0%) between women with intellectual disabilities and those with other disabilities, but significantly increases (9.8%) in relation to women without disabilities.

Likewise, the total female population with intellectual disabilities in these two income brackets highlights the inferior position of black women in relation to white women (78.6% against 90.6%). This can also be observed in the other income brackets.

The distribution curve of women with monthly income superior to 2 minimum wages highlights even further the position of social inferiority of black women, whatever their condition is (with or without disabilities): from 2 to 5 MW, 27.1% of black against 51.4% of white women; from 5 to 10 MW: 5.6% of black against 16.3% of white women; from 10 to 20 MW: 1.4% black against 5.4% of white women; and from 20 MW or more: 0.4% of black versus 1.6% of white women.

These analyses sought to portray the living conditions of the population with intellectual disabilities, by comparing that with race and gender, through the distribution of monthly income, which allows us to elaborate our closing arguments.

Final Considerations

With this study on the relationship between intellectual disability and class, race and gender, based on Brazilian social indicators of 2010, we intend to highlight what the literature in the field has already pointed out since the 1990s: the need to overcome the abstract way of considering disability as the preponderant factor in determining the subject’s living conditions, regardless of class, race and gender. So far, there have been few and restricted investigations that analyze the real living conditions through data that expose the political and social macrostructure involved.

In this sense, the analyses we conducted in this study constitute our effort to offer a contribution based on official statistical data which, although limited to this population’s income indices, offers a first overview of this relationship. Such overview indicates the possibility and the need for further studies, both based on other indicators (education level, professional education levels, places of residence, etc.) and on regional studies, within states and cities, etc., in this country of continental dimensions and significant social differences.

Data and comparisons presented here show that the fact of having an intellectual disability, in general, places this population in a condition of social disadvantage. That is, it incorporates the perspective that this mark produces negative effects on the possibilities of qualified socialization, insofar as, in our society20, the purchasing power is fundamental for the population’s quality of life.

However, they also show the close relationship between income levels and race and gender. Although intellectual disabilities produce evident deleterious effects when compared to the population with other disabilities and, even further, without disabilities, the gradual reduction of these differences, as the monthly income increases, evidences the imbrication of living conditions between this population and the population in general.

In this sense, the analyses conducted here present unquestionable elements that show the influence race and gender exert in the possibilities of qualified social insertion of the population with intellectual disability, characterized, in general, by the following order of prevalence: white men, black men, white women and black women. That is, at the top of the pyramid are the 16.3% white men without disabilities, who hold an income of over 5 minimum wages, while, at its bottom, the 90.6% of black women with intellectual disabilities, which live on a monthly income of 0-2 minimum wages.

Finally, it should be noted that these data refer to a decade ago when the situation in Brazil reached social indices never seen before, to the point of a respected journalist, in a television channel news that today demonizes the popular government of that time, present the following comparisons between the economic situation in Brazil from 2002 to 2010: annual growth in inflation, from 12.5% to 5.1%; dollar exchange rate, from R$ 3.94 to R$ 1.70; annual GDP growth, from 2.7% to over 7.0%; and unemployment level from 12.7% to 6.2%, only to conclude that these were the best indices in forty years, which placed Brazil in the best possible scenario (Betting, 2010).From then on, with the replacement of internationally acknowledged President Lula (about whom President Obama said, “[…] this is my man right there, I love this guy!” and “[…] he is the most popular politician on Earth”), by President Dilma Rousseff, reactionary forces started articulating a coup d’état, since they couldn’t be elected through popular vote. This culminated in the farce of her impeachment, personally conducted by President of the Federal Chamber who, right after the coup, was impeached and sent to prison for corruption, where he still serves his sentence.

The coup d’état was even more evident with the illegal impediment for Lula to be a candidate in 2018 elections, due to his conviction in the Car Wash operation. Today, this operation is completely discredited because of countless evidences of illegalities and political use to render him ineligible. On 8th March 2021, Lula’s conviction was annulled by the Supreme Court of Justice (STF).

Mainstream media tried to campaign for more palatable candidates for the international economic market and Brazilian ruling class but failed miserably. A sordid campaign against the candidate of the Workers’ Party ended up co-opting discontent voters to change their vote and endorse an obscure and violent deputy, with a history of repeated pronouncements and actions against human rights. Twenty-two months before the election, his voting intentions reached only 7% of the national electorate but he managed to win the runoff.

However, even with this unexpected growth, the media continue to insist on a polarization between two extremes (the corrupt populist radicals versus the far-right candidate) as if it were difficult to choose between the latter and a university professor, former Minister of Education, with an enviable democratic history. For the media, what mattered was pleasing international interests and Brazilian ruling class.

In this way, with the approval of the main Brazilian press organs, the great danger assumed the presidency and his calamitous performance has resulted in the following current economic indicators: inflation, 0.27%; dollar quotation, R$ 5.85; GDP growth, -4.1%; unemployment rate of 14.6%. These figures show the dimension of the catastrophe in which the country currently finds itself in.

Not to mention the total health calamity caused by the covid-19 pandemic. Due to an absolute lack of national coordination, at the present time, our country is the world’s epicenter of the pandemic, given the increasing rates of contamination and deaths that foreshadow an unimaginable health catastrophe if no immediate drastic measures are taken to control and reduce it.

Comparing the country’s economic and political situation in 2010 and nowadays was necessary because, if in the best possible scenario, the relationship between intellectual disability, class, race and gender overlapped, the deterioration of living conditions after the 2016 coup is surely producing even more dramatic effects on the entire population, fundamentally on the poor and, among these, those with intellectual disabilities. These people deserve the attention of researchers on special education policies underway in Brazil.

Notas

1The dates indicated here correspond to the first edition in Portuguese. Still to exemplify how widely it spread, the third edition of Cruickshank & Johnson was published in 1988, that is, only nine years after the first edition, an average of one edition every three years.

2To illustrate, in his excellent doctoral thesis (2014), to analyze the situation of students with disabilities in schools of rural settlements, Gonçalves restricts data to different types of disabilities, and does not include, for example, these students’ racial distribution. With this, it is not our intention to diminish the high quality of this exemplary thesis, but only to point out the failure to exploit the possibility of looking at issues of race in schools run by counter-hegemonic social movements – concrete expression of class struggle in our country – in comparison with that of schools created and maintained by the constituted powers.

4As an example, see Almeida; Ferreira (2018), there is no reference to sex and color/race of students with disabilities who ascended to higher education, demonstrating how overwhelming disability can be in the constitution of their identities.

5Mike Oliver (1946/2019), disability rights activist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Greenwich, has had significant influence in the field of policies for people with disabilities.

6 Oliver (1999, p. 10), with data collected from New Internationalist magazine, vol. 233, 1992, describes: “Of the 500 million people with disabilities in the world, 300 million live in developing countries, 140 million of which are children and 160 million, women. One out of five, that is, one hundred million people are disabled due to malnutrition. In developing countries, only one out of a hundred people with disabilities has access to any form of rehabilitation and 80% of all people with disabilities live in Asia and the Pacific but receive only 2% of the total resources allocated to people with disabilities”.

7Noronha’s doctoral thesis (2014) highlights the high standard of living of adults with serious intellectual disabilities who, despite living in a segregated institution, maintain a very high standard (obviously supported by their wealthy families), distinguishing social segregation from social oppression. Within this author’s perspective, we should consider former American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as oppressed due to his physical disability.

8The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a law that makes available a free appropriate public education to eligible children with disabilities throughout the nation and ensures special education and related services to those children. Available at: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/about-idea/.

9Although Skliar’s work focuses exclusively on the deaf population, it is being analyzed exactly because of the subsumption of issues of class, race and gender into the central category of disability.

10The term exceptionality to define the universe of students included in special education was, at the time of this publication, the most accepted term by the academic community.

12If, in the past, we were critical of the use that different governments, including during the military regime, made of these data, in the current, eminently fascist government, the scandal is even greater: denial of unquestionable empirical data, such as, for example, those produced by INPE on deforestation in the Amazon.

13The construction of a social indicator occurs, initially, by extracting raw data from the selected source (IBGE demographic census). Then, these data are processed and organized in the way they were collected, so that, through a research question, researchers can select and decide which crossings should be performed to answer their question.

14Including information of people with visual, physical and hearing disabilities, to distinguish data of total disability from intellectual disability.

15Based on the contributions of Munanga and Gomes (2006), data on the self-declared black and brown were grouped, because, due to their color/race, they are concrete expressions of the historical disadvantages caused by the inequalities of a society that was based on the institution of slavery.

16Similarly, gender relations based on statistical data about sex are based on the argument established by Ferraro (2010), that of differentiation between the biological character of sex and the historical oppression of male over women (sexism).

17Although the concept of social class is not restricted solely to the economic aspect, there is no doubt that significant differences in monthly income are fundamental and basic indicators (even if not the only ones) to analyze the social position of individuals within the social structures of modern capitalist societies. In this regard, see Ferraro (2010).

18 Santos (2006) shows that, regardless of the correctness of the diagnosis of mild intellectual disability, once diagnosed, it indelibly marks the lives of these subjects, whether due to the decisive influence on their self-image, or the impact it causes among their family members and close social environment: in short, the subject incorporates and is treated as an intellectually disabled person.

20“One of the essential assumptions of the so-called knowledge society or economy is, far beyond the capacity for industrial production and reproduction, the ability to generate technological knowledge and, through it, constantly innovate for an avid and nervous market in the demands of consumption” (Vogt, 2005).

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, José Guilherme de Andrade; FERREIRA, Eliana Lucia. Sentidos da Inclusão de Alunos Com Deficiência na Educação Superior: olhares a partir da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, ABRAPEE, São Paulo, v. 22, n. especial, 2018. [ Links ]

BETTING, Joelmir. Jornal Band News, São Paulo, 2010. Disponível em: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lB48qoG5CDk>. Acesso em: 09 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira. Educação Especial Brasileira: integração/segregação do aluno diferente. São Paulo: EDUC, 1993. [ Links ]

BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira; FERRARI, Carla Cazelato. Contrapontos Sócio-Educacionais da Surdez: para além da marca da deficiência. In: CEARÁ. ASSEMBLEIA LEGISLATIVA, 2013, Fortaleza. Anais... Cadernos Tramas da Memória. Fortaleza, Memorial da Assembleia Legislativa do Ceará – MALCE, 2013. [ Links ]

COLLARES, Cecília Azevedo Lima; MOYSÉS, Maria Aparecida Affonso. Preconceitos no Cotidiano Escolar: ensino e medicalização. São Paulo: Cortez, 1996. [ Links ]

CRUICKSHANK, William; JOHNSON, Orville. A Educação da Criança e do Jovem Excepcional. Rio de Janeiro: Globo, 1979. [ Links ]

DUNN, Lloyd. Crianças Excepcionais: seus problemas, sua educação. Rio de Janeiro: Ao Livro Técnico, 1971. [ Links ]

DURKHEIM, Émile. As Regras do Método Sociológico. São Paulo: Abril, 1983. [ Links ]

FERRARO, Alceu Ravanello. Escolarização no Brasil: articulando as perspectivas de gênero, raça e classe social. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 36, n. 2, 2010. [ Links ]

GONÇALVES, Taísa Grasiela Liduenha Gomes. Alunos com Deficiência na Educação de Jovens e Adultos em Assentamentos Paulistas: experiências do PRONERA. 2014, 199 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Especial) – PPG em Educação Especial, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2014. [ Links ]

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico 2010. Rio de Janeiro, IBGE, 2010. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Educacionais ‘Anísio Teixeira’. Sinopse Estatística da Educação Básica 2019. Brasília, INEP, 2019. [ Links ]

KIRK, Samuel; GALLAGHER, James. Educação da Criança Excepcional. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1979. [ Links ]

MAZZOTTA, Marcos José da Silveira. Fundamentos da Educação Especial. São Paulo: Pioneira, 1982. [ Links ]

MOYSÉS, Maria Aparecida Affonso; COLLARES, Cecilia Azevedo Lima. Revendo Questões Sobre a Produção e a Medicalização do Fracasso Escolar. In: VICTOR, Sônia Lopes; DRAGO, Rogério; CHICON, José Francisco (Org.) Educação Especial e Educação Inclusiva: conhecimentos, experiências e formação. Araraquara: Junqueira & Marin, 2011. [ Links ]

MUNANGA, Kabengele; GOMES, Nilma Lino. O Negro no Brasil de Hoje. São Paulo: Global, 2006. [ Links ]

NORONHA, Lucélia Fagundes Fernandes. Educação de Adultos com Deficiência Intelectual Grave: entre a exclusão social e o acesso aos direitos de cidadania. 2014. 138 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – PEPG em Educação: História, Política, Sociedade, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014. [ Links ]

OLIVER, Mike. The Individual and Social Models of Disability. In: JOINT WORKSHOP OF THE LIVING OPTIONS GROUP AND THE RESEARCH UNIT OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS, 1990, London. Anais… London: Royal College of Physicians, 1990. Disponível em: <https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/Oliver-in-soc-dis.pdf>. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

OLIVER, Michael. Capitalism, Disability and Ideology: a materialist critique of the normalization principle. In: FLYNN, Robert; LEMAY, Raymond. A Quarter-Century of Normalization and Social Role: evolution and impact. Ottawa: University Ottawa Press, 1999. [ Links ]

PASTORIZA, Taís Buch. Estudantes com Deficiência na Educação Superior: estudo do perfil e do ingresso via Prouni. 2020. 220 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – PPG em Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2020. [ Links ]

PATTO, Maria Helena Souza. A Produção do Fracasso Escolar: histórias de submissão e rebeldia. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 1990. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Roseli Albino dos. Processos de Escolarização e Deficiência: trajetórias escolares singulares de ex-alunos de classe especial para deficientes mentais. 2006. 196 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – PEPG em Educação: História, Política, Sociedade, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2006. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Natália Gomes dos. Desigualdade e Pobreza: análise da condição de vida da pessoa com deficiência a partir dos indicadores sociais brasileiros. 2020. 141 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – PPG em Educação. Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, 2020. [ Links ]

SKLIAR, Carlos. Uma Perspectiva Sócio-Histórica Sobre a Psicologia e a Educação dos Surdos. In: SKLIAR, Carlos (Org.). Educação e Exclusão. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 1998. [ Links ]

SKRTIC, Thomas. A Injustiça Institucionalizada: constituição e uso da deficiência na escola. In: BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira; MUNAKATA, Kazumi; CHIOZZINI, Daniel Ferraz. A Escola Como Objeto de Estudo: escola, desigualdades, diversidades. Araraquara: Junqueira & Marin, 2014. [ Links ]

SKRTIC, Thomas. La Crisis en el Conocimiento de la Educación Especial: una perspectiva sobre la perspectiva. In: FRANLKLIN, Barry. Interpretación de la Discapacidad. Barcelona: Pomares-Corredor, 1996. [ Links ]

TELFORD, Charles; SAWREY, James. O Indivíduo Excepcional. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1978. [ Links ]

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES OF SCIENCES, ENGINEERING, AND MEDICINE. Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children. Washington (D.C.): National Academies Press, 2015. Disponível em: <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK332894/>. Acesso em: 10 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

VOGT, Carlos. A Sociedade do Conhecimento. Disponível em: <https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/a-sociedade-do-conhecimento/>. Acesso em: 12 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

Received: May 15, 2021; Accepted: July 20, 2021

texto em

texto em