Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educação e Realidade

Print version ISSN 0100-3143On-line version ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.46 no.4 Porto Alegre 2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236117553

THEMATIC SECTION: EXPERIENCES OF ALTERNATIVE HIGHER EDUCATION

Teacher Training in the Context of Rural Socioterritorial Diversity

IUniversidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), Curitiba/PR – Brazil

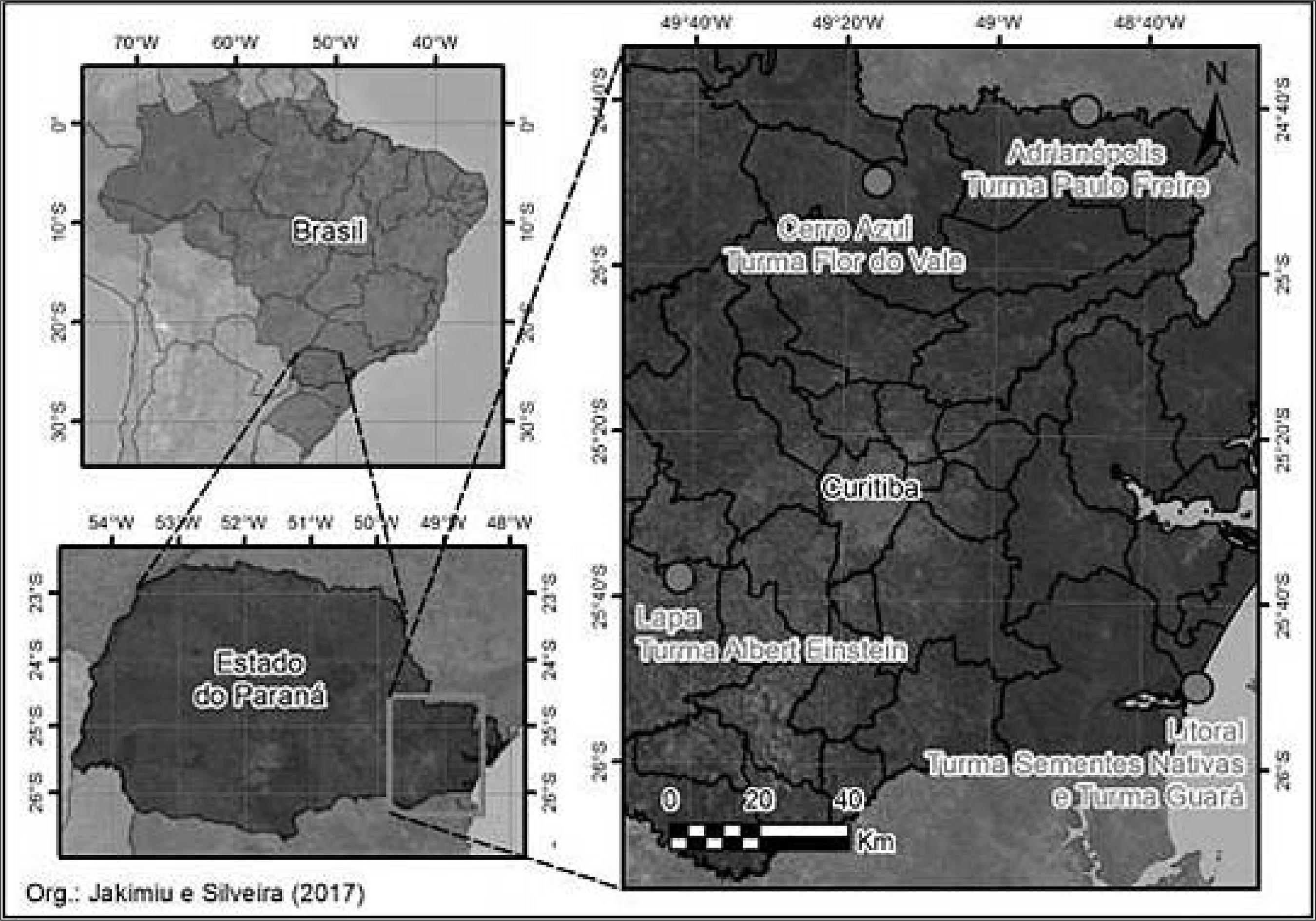

Educação do Campo (Education of the Countryside) has provided some spaces for the recognition of epistemic diversity and for decoloniality in teacher training for rural schools. The analysis is based on the development of an original curricular proposal – the Licentiate in Educação do Campo(LECAMPO), from the Federal University of Paraná, Seaside Sector, which is organized in different territories/classes to enable the access of settled, quilombola, indigenous, riverine, and family farmer communities to higher education. The empirical research involved observations and interviews with teachers and students using the methodology of oral story/life story in four LECAMPO classes, in the municipalities of Lapa, Cerro Azul, Adrianópolis, and Matinhos. The study infers that the introduction of the University in the context of rural socioterritorial diversity, through the pedagogy of alternation and itinerancy, has provided new meaning to the logic and epistemology of teacher training.

Keywords Educação do Campo; Teacher Training; Higher Education; Decoloniality

A Educação do Campo tem aberto algumas fissuras para o reconhecimento da diversidade epistêmica e a decolonialidade da formação de educadoras/es para as escolas do campo. A análise toma por base o desenvolvimento de uma proposta curricular original – a Licenciatura em Educação do Campo (LECAMPO), da Universidade Federal do Paraná, Setor Litoral, que é organizada em diferentes territórios/turmas para viabilizar o acesso das comunidades assentadas, quilombolas, indígenas, ribeirinhas, de agricultores familiares à educação superior. A pesquisa empírica envolveu observações e entrevistas com educadoras/es e estudantes, por meio da metodologia da história oral/história de vida, em quatro turmas da LECAMPO, nos municípios da Lapa, Cerro Azul, Adrianópolis e Matinhos. O estudo infere que a inserção da Universidade no contexto da diversidade socioterritorial do campo, a partir da pedagogia da alternância e da itinerância, tem ressignificado a lógica e a epistemologia da formação docente.

Palavras-chave Educação do Campo; Formação Docente; Educação Superior; Decolonialidade

Introduction

Initial teacher training at a higher education level for rural schools is part of the agenda of the Educação do Campo (Education of the Countryside) public policy, which emerges from the social movement of re-existence in the country, of struggle for land and for the right to education. The forma movimento [movement form] (Rosa, 2009) present in the struggle for land, in addition to its educational dimension, produced a specific mode of organizing pedagogical work in the space of social struggles and rural schools (Schwendler, 2017). This Pedagogy of Movement (Caldart, 2000), which is made and remade in the Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 1987), is the groundwork of the education form that produced the foundation for the Educação do Campo Policy (Schwendler, 2017) and, specifically, for the rural teacher training policy. One of the main characteristics of this policy refers to the participation and protagonism of social and union movements in its conception and development (Molina; Antunes-Rocha, 2014).

In this article, it is argued that Educação do Campo has provided some spaces so higher education opens itself to epistemic diversity and to decoloniality in teacher training, in the sense of “[…] challenging and overthrowing social structures, policies and epistemes of coloniality – structures that have been permanent until now – that maintain patterns of power rooted in racialization, in Eurocentric knowledge and in the inferiorization of some beings as less human” (Walsh, 2009, p. 24). Colonial power led to the stripping of the historical identities and social place of rural peoples, especially indigenous and black people, in the history of human cultural production (Quijano, 2005). It is based on the assumption that it is necessary to decolonize education so it embraces other educations, other ways of thinking and living, in addition to a pedagogy of movement, of the oppressed, of resistance, of decoloniality, built in movement by subjects who reinvent their existence so as to re-exist and assert themselves as collective subjects, in struggle, for the transformation of social circumstances and all forms of oppression, of dehumanization. In this context, the social movement, as collective organic intellectuals (Gramsci, 1967), collective, with a pedagogy of resistance and insurgency, has constituted the foundation for reinventing the form and content for teacher training, where knowledge, the way of life and the context of rural peoples in their socioterritorial diversity constitute central axes of the training process and of the structuring of higher education programs.

The process of constitution of teacher training for rural schools will be analyzed through the National Program for Education in Agrarian Reform (Pronera), in particular through the Support Program for Higher Education in Licentiate in Educação do Campo (Procampo). We will also address the challenges to decolonize teacher training, from the theoretical and methodological perspectives of the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Movement Pedagogy and Decolonial Pedagogy. The study involves the analysis of the development of an original curricular proposal: the Licentiate in Educação do Campo – Nature Sciences (LECAMPO), from the Federal University of Paraná – Seaside Sector, aimed at training teachers for rural schools (final grades of Elementary School, High School and Youth and Adult Education). To enable the access of settled, quilombola, indigenous, riverside dweller, fishermen, and family farmer communities, among others, to higher education, this Program is organized into different classes based on itinerancy and pedagogy of alternation. This article examines the extent to which these two components of the organization of the Program’s Political-Pedagogical Project have enhanced the decoloniality of teacher training. Pedagogy of alternation – organized through Tempo Universidade and Tempo Comunidade – is part of the Educação do Campo project, as it constitutes a theoretical-practical process that keeps students rooted in their community during their training process, which also contributes to decrease the university dropout/expulsion rate. The itinerancy regime, in turn, enables the extension of the University to the territories and, due to this factor, the Program serves a great socioterritorial diversity of rural populations, which also contributes to maintaining the identity of an Education program of the/with the/in the Countryside. The hypothesis is that this organizational form has enabled the introduction of higher education in the context of rural diversity, and with this, it has contributed to reconstruct the logic and epistemology of teacher training.

For the empirical study, observations and interviews were conducted, from 2018 to 2019, with 16 students in four classes at LECAMPO, operating between 2015 and 2019, in the different territories in which the Program is materialized, namely: Albert Einstein class, located in the Contestado Settlement, in the municipality of Lapa; Flor do Vale class, located in the municipality of Cerro Azul; Paulo Freire class, located in the city of Adrianópolis; and Guará class, located in the Seaside Sector, in the municipality of Matinhos, location of the UFPR Campus. Additionally, interviews were carried out with 6 teachers and the Program’s pedagogical/managerial team, using the methodology of oral story (Thompson, 2002; Portelli, 1997), specifically of life story (Marre, 1991)1. These respondents, according to the sample diversification criterion, having as reference age, gender, link with the Program, with social movements, relation with rural areas and place of residence, expressed “[…] in a diverse but interrelated way the socioeconomic history of the researched social group” (Marre, 1991, p. 111).

The Process of Construction of Licentiates in Educação do Campo

Teacher training for rural schools constitutes a challenge for public policies as to ensuring the necessary qualification for teaching. According to data from the School Census (Brasil, 2017), Brazil has 55,258 rural schools and 376,850 teachers working in classrooms. However, approximately 46% of these education workers have no higher education training. For many, the only way to obtain qualification is through Distance Education, which, in recent decades, has taken the form of precarious massification of teacher training; a historical reality in the Brazilian rural areas that reflects the absence of the State, as well as an urban-centered education model, the precariousness of education for rural subjects and the working conditions and qualification of education workers. This model, known as Rural Education, which “[…] is at the base of business landowners’ thinking, welfare, political control over the land and the people who live on it” (Fernandes; Molina, 2004, p. 62), disguised in contemporary times as agribusiness, is updated by the new demands for capital reproduction in the country. As part of the very contradiction of the capitalist system, according to the analysis of the National Forum for Educação do Campo (Fonec, 2012), it is possible to affirm that in the transition of models (adjustments to the Brazilian macroeconomic model, capitalist, neoliberal), between the agricultural estate crisis and the emergence of agribusiness, there was a vacuum that was occupied by social movements fighting for land and for Agrarian Reform, which were strengthened. In this process, there was the achievement of Pronera and the constitution of Educação do Campo.

The Movement for an Education in the/of the Countryside was through the 1st National Meeting of Agrarian Reform Educators – the 1st ENERA, in 1997, promoted by the Education Sector of the Landless Rural Workers Movement – MST (Munarim, 2008 ), where it is defined the construction of the 1st National Conference on Elementary Educação do Campo (1998) and the Pronera, instituted by the Federal Government in 1998. Educação do Campo, which originates in territories of resistance and existence of the struggle for land, promoted by the MST and expands through the social practice of various rural movements and organizations, comes to be assumed, in its Seminar celebrating the 20-year anniversary of Educação do Campo and Pronera (2018), as Education of Rural areas, waters, forests, riverine people, quilombolas, extraction workers, fishermen, Fundos de Pasto communities, açaí collectors, coconut processing workers, geraizeiros…, which reflects the socioterritorial diversity of the Brazilian country (Molina, 2019).

Consisting today of a wide diversity of collective subjects from different social movements in the country, unions, non-governmental organizations and universities, this Movement has been fundamental for Educação do Campo to constitute a public policy. Decree No. 7,352/2010, which provides the National Policy for Educação do Campo and the National Program for Education in Agrarian Reform (Pronera), in its article 1, assigns to the State the responsibility for “[…] expansion and qualification of the provision of elementary and higher education to rural populations.” Teacher training at a higher education level to work in rural schools is one of the action axes of the National Educação do Campo Program (Pronacampo), introduced to implement Decree No. 7,352/2010. The constitution of a specific public policy to enable teacher training in the country, guided since the conception of the Educação do Campo Movement, was consolidated as one of its priorities through the 2nd National Conference for Educação do Campo, held in 2004 (Molina; Antunes-Rocha, 2014). This process resumes the role of the public university, which contributes so the country is on its teaching and research agendas.

The experiences of rural teacher training of agrarian reform territories, through the Pedagogy of the Land and Licentiate Programs, supported by Pronera and carried out by public universities in partnership with social movements, have constituted a foundation for the rural teacher training policy, in a broader way. Pronera, linked to the Ministry of Agrarian Development, which came to integrate, as of 2010 (Brasil, 2010b), the Educação do Campo policy, has entered universities with the content and form of the educational project of social movements, generating tensions, but also learnings, which constitute historical accumulations in the production of Educação do Campo (Schwendler, 2017). Despite the resistance of the universities providing the programs, in relation to the training matrices proposed by the rural movements, the collective subjects of the country, through the occupation of academic spaces, have been building the rural teacher profile and teaching the very universities a new concept of teacher training (Molina; Antunes-Rocha, 2014).

This is the basis for the constitution of a “[…] new mode of higher education program in Brazilian public universities” (Molina; Sá, 2012, p. 466), the Licentiate in Educação do Campo, which is implemented with the introduction of Procampo, in 20072, linked to the Ministry of Education. Licentiates in Educação do Campo are found in all regions of Brazil, and in 19 states, competing for the territory of knowledge production. According to the 2017 Census, there are currently 44 programs in 31 higher education institutions. According to Molina (2019), there are 227 classes in progress, with 7,342 enrolled students, 585 higher education-level professors and 117 technical-level teachers. Of these classes, 25% are in the Northeast; 24% in the northern region; 21% in the southern region; 17% in the Southeast and 13% in the Midwest.

The Licentiate Program in Educação do Campo is structured by field of knowledge. It provides training for multidisciplinary teaching in one of the following fields: Languages, Arts and Literature; Humanities and Social Sciences; Natural Sciences and Mathematics; Agricultural Sciences. Its object is the Elementary Education school, with a focus on building the School Organization and Pedagogical Work for the final grades of elementary and high school. It aims to prepare teachers to – in addition to teaching – act in the organization/management of educational processes in formal and non-formal education, in particular in pedagogical work with rural communities, which implies “[…] a specific preparation for pedagogical work with the students’ families and/or social groups of origin, for team leadership and for the (technical and organizational) implementation of sustainable community development projects” (Brasil, 2006, p. 4).

One of the major challenges of the Licentiate in Educação do Campo is the institutionalization/regulation of a higher education program that maintains the link with its materiality of origin: the struggle for agrarian reform, for Educação do Campo and for the permanence/construction of rural schools (Caldart , 2007). As a specific teacher training, the Licentiate in Educação do Campo meets the demand for training educators who already work in rural schools and enables access to education as a right of rural populations to higher education. This specific teacher training has the potential to build a faculty in rural schools that it belongs to, critically understand the reality of the country and engage in the construction of collective projects that dialogue with the demands of rural communities. Similarly, it has the potential to question and rebuild the relation between universities and social movements and to decolonize teacher training, so higher education becomes open to the epistemic diversity provided by the socioterritorial diversity of rural peoples.

The Challenges to Decolonize Teacher Training for Rural Schools

The development of rural territory implies “[…] an educational policy that addresses their diversity and breadth and understands rural populations as proactive protagonists that propose policies and not as beneficiaries or users” (Fernandes, 2006, p. 30). While commodities are characteristic of agribusiness, which appropriates the concept of Educação do Campo to compete for public policies aimed at the country, “[…] the rural population organizes its territory so as to carry out its existence” (p. 29) as to material and symbolic aspects. The territory of the rural population expresses a diversity of ways of working, living and feeling the relation with nature, with the community, with ancestry. This rural diversity is interwoven with the concrete situations of social, political and economic inequality to which rural populations have been historically subjected, characterized by the deep contradictions of the capitalist mode of production (Ghedini; Janata; Schwendler, 2010). These territories, which constitute “[…] geographic and political spaces, where social subjects carry out their life projects for development” (Fernandes, 2006, p. 29), are also pedagogical. Within them, amidst the contradictions and re-existences of rural, water and forest peoples, there is production and apprehension of knowledge of social practice. Recognizing it and incorporating it into teacher training is fundamental for the preservation of rural, indigenous, quilombola, riverside identities and for the reconstruction of the logic of production and appropriation of knowledge in the academic sphere.

The discussion on teacher training involves both the rural populations’ right of access to historically produced knowledge and the need to question the social place and the method of production and appropriation of this knowledge (Schwendler, 2017). By entering universities – territories legitimized in the production of knowledge – as collective subjects, rural social movements, conceived as others, question the invisibility and devaluation of knowledge and culture produced in the social practice of rural subjects in their socioterritorial diversity. Conceiving the rural populations, women, indigenous and black peoples, and workers in general, as “[…] inferior in knowledge, in rationality, in culture, in values have led to the legitimization of the economic, social, and class segregation” (Arroyo, 2015, p. 62). Boaventura de Souza Santos (2007) emphasizes the cognitive injustice, where only one type of knowledge is recognized as legitimate. According to the author, this abyssal thought of modern science is supported by the affirmation of invisibility and of the inexistence of other forms of knowledge, science and rationality. The author points out the need to confront the monoculture of modern science with an ecology of knowledge, which implies the recognition of the plurality of heterogeneous sorts types of knowledge that interact with one another, without compromising their autonomy. In addition to questioning the absences, Santos (2005, p. 172) proposes working based on the emergencies that are revealed “[…] through the symbolic expansion of clues or signs” of the very constructed experience, specifically, that of social movements.

In recent decades, by means of affirmative policies, social movements have employed pressure to break down the fences of knowledge, and assert their role as producers of valid, legitimate knowledge to be incorporated into the curriculum of schools and universities. In this process, Miguel Arroyo (2015) points out a contradiction; which is the fact that social movements fight for schools, for universities, although they have been produced as inferior, as subordinate by hegemonic knowledge. “Let’s occupy the estate of knowledge,” affirm the social movements in their struggle for the right to education. “Let’s occupy the university territory of production, accumulation of hegemonic knowledge to which we are entitled and which has been denied to us because it was fenced and appropriated by the elites as was appropriated and fenced the land which we fought for and occupied” (Arroyo, 2015, p. 54). These rural resistances, producers of political and epistemic disobedience (Mignolo, 2008), are essential to build “[…] new epistemological frameworks that pluralize, problematize and challenge the notion of a totalitarian, single and universal thinking and knowledge” (Walsh, 2009, p. 25). In this dialogue of knowledge, there is one of the possibilities to decolonize the hegemonic teacher training and build other ways of educating, learning, unlearning and relearning, which will be analyzed here from the theoretical-methodological perspectives of the Pedagogy of Movement, of the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and Decolonial Pedagogy.

The Pedagogy of the Movement3, as stated by Roseli Caldart (2011, p. 69), is not a new theoretical current in pedagogy. It consists in “[…] a way of working with different educational practices and theories built historically according to the social and political interests of workers.” This way of working is founded on the “[…] dynamics of the Movement (its questions, contradictions, educational demands of struggle and work) as a reference to build their own syntheses of conception (equally historical, in movement).” Caldart (2000) understands that there is a pedagogy of movement, a praxis of human education, which is constituted from the history of pedagogical reflections and actions of social movements. The Social Movement is understood as a pedagogical subject, “[…] as a collective in movement that is educational, and that intentionally acts in the process of educating the people who constitute it” (Caldart, 2000, p. 1999). Accordingly, one of the major challenges is to transform the Pedagogy of the Movement, the educational intention that social movements produced in the dynamics of their social struggles and collective organizations, into a human education project in the school/university space.

One of the major lessons for this process comes from the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which “[…] re-educates us in the pedagogical sensitivity to perceive the oppressed and excluded as subjects of education, construction of wisdom, knowledge, values and culture. Social, cultural, pedagogical subjects in learning, in training/education” (Arroyo, 2003, p. 34). Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed does not propose to us how to educate them, but to understand how they educate themselves, how they learn, how they teach, how they humanize and reinvent themselves in the struggle against the dehumanization to which they were subjected. It is a pedagogy of the oppressed, which is forged with them, as subjects, collective, in the struggle to recover their stolen humanity. “Pedagogy that makes oppression and its causes an object of reflection by the oppressed, which will result in their necessary engagement in the struggle for their liberation, in which this pedagogy will be made and remade” (Freire, 1987, p. 32). The principle of the pedagogy of the oppressed seeks to find, in the dialectic of the dehumanization-humanization process, the elements for the transformation of the subjects and conditions that dehumanize them, and of the dehumanizing, colonizing conceptions that are perpetuated in the mentality of the subjects, even if the conditions that generated them may have changed.

In this sense, Catherine Walsh, based on the thought of Paulo Freire and Frantz Fanon, points out the need for pedagogical perspectives that “[…] interweave with the projects and perspectives of critical interculturality4 and decoloniality. Pedagogies that dialogue with the critical-political background, while being founded on the struggles and praxis of a decolonial orientation” and, therefore, confront the racist myth, and the modern-western rationality. They are decolonial pedagogy(ies),5 which seek to “[…] transgress, displace and affect the ontological, epistemic and cosmogonic-spiritual negation that was – and is – strategy, end and result of the power of coloniality.” They are “[…] pedagogies that integrate questioning and critical analysis, transforming social action, but also insurgency and intervention in the fields of power, knowing and being, and in life; those that foster an insurgent, decolonial and rebellious attitude” (Walsh, 2009, p. 27).

Based on the Pedagogy of the Movement, the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and on Decolonial Pedagogy, it is understood that, in the process of training rural teachers, it is not enough to “[…] incorporate those traditionally excluded into the existing (educational, disciplinary or thought) structures,” but it is necessary “[…] to provide visibility, confront and transform the structures and institutions that differentially position groups, practices and thoughts within an order and logic that, at the same time and still, is racial, modern-western and colonial” (Walsh, 2009, p. 24), also based on heteropatriarchal and classist bases.

In the process of transforming academic logic, Mônica Molina (2019) emphasizes the importance of recognizing that rural subjects, upon entering universities, bring to mind a socioterritorial diversity of their contexts of origin and, therefore, the different forms of struggle and material production of life occurring in their territories. They also bring a cultural heritage, loaded with wisdom of social practice, linked to the traditions that their collectives have constituted in the processes of existence and resistance in their lands and territories. Understanding these lessons and incorporating them as “[…] central input in teacher training processes is a major challenge for Licentiate Programs in Educação do Campo” (Molina, 2019, p. 8).

In addition to the process of recognition and production of knowledge, social movements also question the organizational structures of programs at universities and reinvent methods of construction and socialization of knowledge. One of the lessons from the relationship between social movements and the university in the process of constituting the policy for training teachers for rural schools has been the way in which Licentiate Programs in Educação do Campo are organized to meet the demand for socioterritorial diversity of rural populations. Itinerancy and pedagogy of alternation are understood here as important components of the organization of the political-pedagogical project of the Program in the access of rural subjects to higher education and in the decoloniality of teacher training.

Itinerancy and Pedagogy of Alternation in the Process of Decoloniality of Teacher Training – the Experience of LECAMPO – UFPR, Seaside Sector

To examine the potential of itinerancy and of the pedagogy of alternation in the introduction of higher education in the context of rural diversity, and in the restructuring of the logic and epistemology of teacher training, the Licentiate Program in Educação do Campo (LECAMPO) is taken as a reference, with emphasis on training in Nature Sciences, at the Federal University of Paraná – Seaside Sector. The Program encompasses municipalities on the coast of Paraná, also covering the region of Vale do Ribeira, also in the state of Paraná. Although it does not cover the Seaside Sector, due to the demand from the settlements, the Program also involved the municipality of Lapa.

LECAMPO was implemented through the Public Call Notice No. 02, of September 2012 - SESU/SECADI/SETEC, which creates the Licentiate Programs in Educação do Campo, in the in-person mode. Since 2016, the Program has been institutionalized at UFPR, Seaside Sector, with a regular provision of 40 places per year. Its Political Pedagogical Project (PPC, 2012) is founded on the legal framework of Educação do Campo (Education of the Countryside), and on the principles of Pronacampo. Admission to LECAMPO is organized through a special selection process and a differentiated calendar. The Program, which is conducted in the in-person mode, in an itinerancy and alternation regime, is aimed at rural teachers who do not have a licentiate degree, as per decree no. 7,352/2010, which also favors family farmers, settlers, campers, fishermen, riverside dwellers, islanders, quilombolas, indigenous peoples and forest peoples.

The principles of Educação do Campo from the perspective of social movements were fundamental in the constitution of the Program. “Seeing studies of other LECAMPOs in Brazil, the idea of itinerancy and alternation was exactly to take the university to the communities” (Entrevista Margarete, 2018)6. It was precisely the itinerancy regime that enabled LECAMPO to meet this diversity of rural subjects, which constituted a challenge for the teachers and the pedagogical team. “We have been fighting to keep this Program within the principles of Educação do Campo, but it is not always easy. Here, this is one of the few programs that manage to achieve this diversity of subjects: quilombolas, indigenous people, campers, settlers, fishermen” (Entrevista Patrícia, 2019).

Itinerancy, which consists in the teachers/pedagogical and managerial teams moving to the places where the classes are held, enabled the creation of several classes in different territories. The Program’s first classes7, with 120 places, in the 1st semester of 2015, involved rural subjects who were members of social movements, especially those in the struggle for land – Albert Einstein Class – with classes at the Contestado Settlement, based on a partnership with the Latin American School of Agroecology – ELAA, in the municipality of Lapa/PR; and the Flor do Vale Class, with rural persons and teachers from the Vale do Ribeira region, with classes held at the Universidade Aberta do Brasil Hub, in Cerro Azul/PR. The Program’s second classes, in the 2nd semester of 2015, with 120 places, met the demand of Vale do Ribeira, which encompasses quilombola communities, family farmers and rural school teachers – Paulo Freire Class – with classes held at Diogo Ramos Quilombola State Secondary School, in the João Surá Quilombola Community, in the municipality of Adrianópolis; and the Guará Class, at the headquarters of Seaside Sector, with students from different municipalities and communities on the coast of Paraná (Gonçalves, 2016). The following classes (regular provision): Sementes Nativas (2017), Sepé Tiaraju (2018), Chico Mendes (2019) and the 2020 ones have their classes held at the Seaside Sector, in the municipality of Matinhos.

Source: Jakimiu and Silveira (2018).

Figure 1 Location of the Classes of the Licentiate Program in Educação do Campo at UFPR – Seaside Sector

The first class of the LECAMPO Program, the Albert Einstein Class, with students from the struggle for land, was established in the Contestado Settlement, an area remaining from the sesmarias regime in Colonial and Imperial Brazil, occupied in 1999 by families associated with the MST. The vast majority, more than 50% of the 150 families that live in the area, produce agroecologically. This class, being a precursor, had a fundamental role in the Program’s link with the materiality of origin of Educação do Campo and the learning resulting from the Pronera Programs, in particular, from the praxis of the Pedagogy of the Movement. The training/educational activities are also associated with the “[…] principles of Agroecology and Work, understanding them as educational in the rural teacher training processes within the scope of the program” (Jakimiu, 2018, p. 32). During the Tempo Universidade (TU), whose stages are long (usually forty-five days), the class is organized into basic nuclei and develops different educational times. This dynamics provides the education of the subject, combined with the conduct of cognitive, affective and political work, interconnected with the educational perspective of the social movement (Santos, 2020), which involves a collective ethics, as expressed in an interview: “I was born in an MST camp […]. The pursuit of knowledge is the feedback to this movement. Not for a single person, there are thousands within the MST movement” (Energia, 2018).

This connection between students and rural social movements is different, especially in the Flor do Vale class, since the movements have no strength in the municipality of Cerro Azul, “[…] a territory occupied by various traditional communities and with different cultural identities, a characteristic that defines the profile of the students’ class” (Silva et al., 2019, p. 54). Even without direct influence from the Pedagogy of the Movement, after joining the Program, the students report that many questions arose about their living conditions, and, beyond that, the meanings of being a rural subject and a future rural teacher were unveiled. “I did not recognize myself as a rural subject” (Entrevista Jaboticaba, 2018). “The program made us put on glasses, see things that we, who lived in the country, could not see. A lot of things went ‘over our heads’ and we didn’t pay attention. Now everything I see seems to be related” (Entrevista Pitanga, 2018). They realize the importance of training in Educação do Campo, even because “[…] the municipality has 71.6% of the population in rural areas and few teachers. It was always that situation of the teacher who lives in the city or who comes from somewhere else, and who does not know the reality” (Entrevista Jaboticaba, 2018).

The Paulo Freire Class, which has its class activities on weekends, at the João Surá Quilombo, has its own characteristics arising from the historical conditions of the formation of the territory and of the constitution of students’ identities, permeated by the tensions that quilombola communities face to make viable the existence and regularization of their territories. The presence of a LECAMPO class sought to meet the demand for preferential training of quilombola teachers and managers in schools that receive students from quilombola territories, and the guarantee of initial and continuing training for teachers to work in Quilombola School Education, guaranteed by the Resolution no. 8, of November 20, 2012 (Brasil, 2012), which defines the National Curricular Guidelines for Quilombola School Education in Elementary Education. The Adrianópolis municipal government wanted the Program to be in the urban area, teacher João Carlos discloses (Entrevista, 2019). “We said: ‘No, if we are going to do it here, it will be in João Surá, because we want the quilombola people to register.’ Otherwise, we will repeat what education normally does, which is to be in the urban center and, consequently, they will give up.” The importance of this Program through itinerancy is expressed in the report of one of the students.

We didn’t understand well: ‘A university here in the region?’ The program gave us what we had the most difficulty in doing […], because in the Pedagogy program I attended there was nothing even about diversity, even less when it comes to rural, indigenous or quilombola education

(Entrevista Educação, 2019).

The Guará Class, whose class activities are held in the UFPR Seaside Sector, in Matinhos, is composed of subjects from various territories on the coast of Paraná (Guaratuba, Guaraqueçaba, Antonina, Morretes, Matinhos, Paranaguá, and Pontal do Paraná). Diversity is inherent in the very class – they are quilombolas, faxinalenses, islanders, riverside dwellers, fishermen and rural subjects –, which motivated the implementation of itinerant stages – this time, not only with the teachers but together with the students. “We instituted itinerancy in the class itself! The class had six meetings in six different territories […]. It was very interesting. This made the group realize a lot of things” (Entrevista Luciano, 2019), in other words, that there is time and effort invested by those who live far away from the University. It also enabled us to learn about the context of each community served by the class. “We use the boat, because that is the only way to make it across to Paranaguá. Then, we take the bus and come every weekend […]. In order to come here, I faced high waves, rain, wind, I would get here completely soaked through” (Entrevista Talha-mar, 2019). Providing itinerancy between the territories served was essential so students could have contact with other modes of existence and recognize them as part of their rural identity (Santos, 2020).

The students’ perception as to their multiple identities occurred through field visits to the four classes under analysis, during the Tempo Universidade. In loco observations enabled perceiving the socioterritorial dimension served by the program, and how each teacher worked to meet the specificities of each territory, enabling the appreciation and exchange of knowledge based on the experience and context of each student/class.

Teacher itinerancy has been crucial for the implementation of these classes, so as to make the rural peoples’ right to higher education viable. During the interviews, the students emphasized how favorable the presence of schools/universities in the territories is for education from elementary school to university, with the aim of training professionals to meet the needs of the communities. “I dropped out of school because there was no school on the island anymore, and I couldn’t go anywhere else. Now there’s my children, now there’s this opportunity” (Entrevista Talha-mar, 2019). Itinerancy has also contributed so the university leaves its academic walls and immerse itself in the rural reality, loaded with systemic contradictions, and with flavors and knowledge of the socioterritorial diversity of rural subjects, which were constituted in social practice and struggles of resistance against the negation of their existence. With itinerancy, in a way, the public university manages to maintain a more organic relationship with social movements and a commitment to the fundamentals of Educação do Campo, because, “[…] if we lose sight of this origin, we distort the training process” (Entrevista Patrícia, 2019). However, some challenges were pointed out by the teachers/pedagogical team, such as the demand for financial resources for traveling, availability and overload of teachers who spend hours traveling and often work without time off. “Adrianópolis, for example, we spent a day traveling. The time in the classroom still increases a lot, right, which is more tiring for the student. In this case, the long stage would be better, which would make better use of their time” (Entrevista João Carlos, 2019).

Although it is recognized that itinerancy in the territories is essential to maintain the identity of this LECAMPO, the opening of new classes, in the period from 2017 to 2020, has only occurred on the premises of the Seaside Sector. The new public process opened for the 2021 school year8, with 40 places, however, once again includes the territory of the Contestado Settlement, and the ELAA, as the location for holding the University Time (UT). What is evident in the teachers’ accounts, both in the interviews and in the observations made during activities and meetings, is that those who are related to rural issues assume their belonging to the working class, or conduct an organic work with the communities served and/or with the social movements are the ones that fight the most for the maintenance of the itinerancy regime (Santos, 2020).

LECAMPO’s Political Pedagogical Project is also structured on the pedagogy of alternation9, in line with the Operational Guidelines for Elementary Education of Rural Schools and Decree No. 7,352/2010, which explains, in Article 5, the legitimacy and need for specific policies for training teachers for Educação do Campo, recognizing the use of “[…] appropriate methodologies, including the pedagogy of alternation, and without prejudice to others that meet the specificities of Educação do Campo” (Brasil, 2010a). Education by alternation consists in a methodology for organizing formal education, which originated in Europe, associated with collective processes involving family farmers, Church participation and relationship with the State. This method combines practice and theory in a praxis, in which times and places of learning alternate, being a general and technical training in a boarding school regime, concentrated in a training center, and a practical/reflective work in the rural community/family (Ribeiro, 2008).

In Brazil, although alternation was more common in the provision of Elementary education, due to the experiences of Agricultural Family Schools (EFAs) and Rural Family Houses (CFRs), it has enabled the expansion of higher education to rural subjects. The accumulation for this type of provision in higher education can be attributed to the experiences conducted in programs linked to Pronera, in different areas of knowledge (Earth Pedagogy, History, Agricultural Sciences, Geography, Arts, Law, Agronomy, Communication, Nursing, among others) (Molina, 2012). The alternation in Pronera, unlike the experiences of the EFAs and CFRs, is based on the experiences of education of the MST and presents a strong relation with Socialist Pedagogy, in the relation between school and work, proposing an omnilateral human education, based on a project of emancipation (Janata; Anhaia, 2018). This organizational methodology ensures that the educational/training times and spaces are properly adapted to the reality of rural areas, and enables flexibility for the school calendar in relation to rural life and work. In other words, a program with a curriculum organized by alternation enables “[…] integrating the performance of the students in the construction of the knowledge necessary for their training as educators, not only in school training spaces, but also in the life production times in the communities where the Rural Schools are located” (Molina; Sá, 2012, p. 470).

At LECAMPO, students divide their time between periods of activities, classes and mentorship at the university, and periods of training activities in their community/school. This organization of the Program, which alternates the University Time (UT) and the Community Time (CT), in addition to bringing education closer to the students’ reality, also seeks to “[…] prevent that the entry of young people and adults into higher education reinforces the alternative of moving from the rural area, and aims to facilitate access and permanence in the program for practicing teachers” (Molina; Sá, 2012, p. 468). To organize the UT, the Program’s teachers seek to understand the context of each class. Only the Albert Einstein Class had an adequate structure for housing and organizing the UT in long stages, since the students were staying at ELLA. In the other classes, the stages were short, usually concentrated on weekends. “The short [stage] works very well, regardless of space. But in the territory, the long one is still the best […]. Students are discharged from their duties and can commit. Thus, they don’t give up. (Entrevista João Carlos, 2019). The demand for the Program’s teachers to move required that the classes were concentrated and organized in short stages. With the new classes, located in the Seaside Sector, there was the option for fifteen-day stages.

In the context of LECAMPO, although occurring differently, alternation provides the university with a specific method for appropriation and construction of knowledge through the methodology of Popular Education, with an emphasis on action, reflection and action from the perspective of social transformation. The knowledge that results from this methodology “[…] resignifies reality based on theories and on the relation with other spaces and subjects, therefore, it contributes to breaking with the conventional structure of education that trains for domestication” (Santos, 2012, p. 83). Alternation enables “[…] experiencing and building a continuous process of education, wherein social reality is the central input for the training” of teachers, without considering, however, “[…] just being in reality the issues that these students have the right to learn.” In this sense, alternation has become a “[…] fundamental methodological tool, as it enables bringing the University closer to the processes for production of knowledge of these real contradictions in which rural subjects are situated during the continuous process of materialization and construction of their life” (Molina, 2015, p. 158).

The hegemonic logic does not conceive the social practice, the ground of the rural, quilombola, indigenous people as a space for construction of legitimate knowledge to be learned. The alternation presents the pedagogical intention of establishing a dialogue between the experience knowledge made (Freire, 1996) and the existing academic knowledge, and resignifies the possibility of its production. This new way of organizing the academic curriculum surpasses the conception of scientific knowledge as the only way of knowing, or as the only method of comprehending a given object, and contributes to decolonizing teacher training.

With the university going to the territories, through the pedagogy of alternation and teacher itinerancy, it can be observed the implementation of teaching, research and extension projects based on the reality of the classes, which has contributed to strengthening the communities. Similarly, it was observed the integration of knowledge related to the Sciences of Nature with the way of life of the communities.

People used to say that the darkest soil is the one that has fertilizer, it’s called red massapê, dark massapê […]. Then, suddenly, the teacher comes to teach! The tool, instead of being a book, a pen, was a hoe… a shovel, and a pickaxe (laughs). I thought: ‘Wait, it can’t be. A doctor?’ He explained the formation of limestone, what happens to the darkest part of the soil, related to oxygen and photosynthesis. He used our everyday life and related it to chemistry, biology and physics. This is just one of the times

(Entrevista Educação, 2019).

This organizational methodology contributes so the Licentiate Program in Educação do Campo prepares students for an omnilateral training, which, in addition to technical-vocational training for the organization of pedagogical work at school, for teaching by area of knowledge, and for management of educational and development processes in rural communities, families, and different social groups present in reality, educates an organic intellectual in the Gramscian sense, who becomes part of the community as an agent of counter-hegemonic actions.

The activities carried out in each class at LECAMPO are based on diagnoses of their territories, called Reality Inventory, which link the two training stages of alternation. “This inventory provides orientation to what we are going to work on, so they can learn about other territories, dialogue with one another and build knowledge based on the reality of the subjects, which is the foundation of Educação do Campo” (Entrevista Luciano, 2019). Furthermore, it enables students to redevelop their conception of themselves and their territory. “The program led me to open my eyes and look with great affection at everything around me” (Entrevista Quero-quero, 2019).

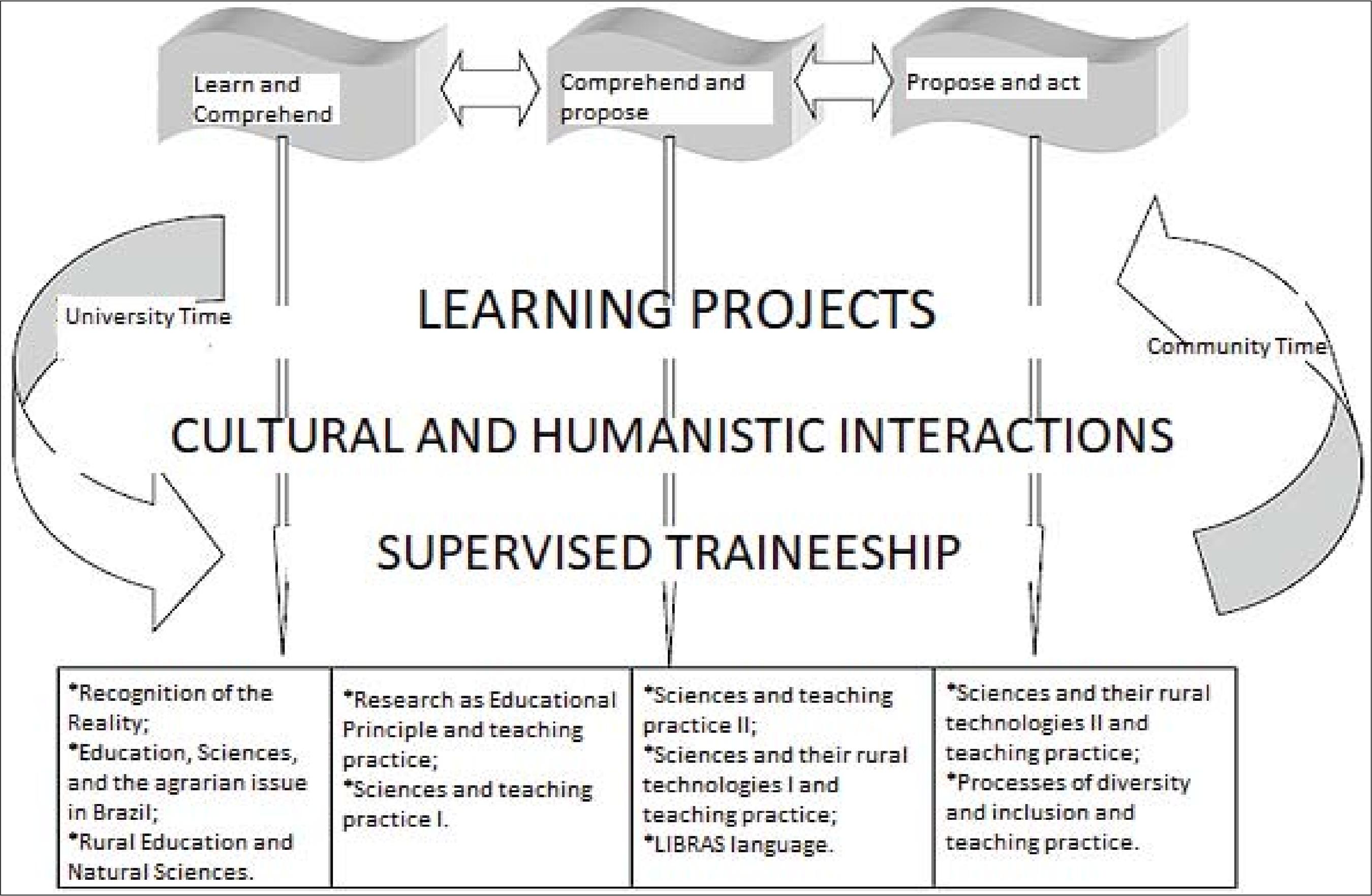

This educational perspective is expressed in LECAMPO’s curricular matrix, which also reflects the Political Pedagogical Project of the UFPR Seaside Sector, which encompasses three learning spaces: the Theoretical-Practical Foundations; Learning Projects10; and Cultural and Humanistic Interactions11. This organization contributes to the construction of knowledge in the dialogue between the different areas and in the relation with the dynamics of the reality of which students are part.

Source: PPC (2012, p. 51).

Figure 2 Relation of the Curricular Matrix with the Institutional Political Pedagogical Project

Learning Projects ensure that all students have access to undergraduate research, regardless of projects and resources from departments and advisor teachers. This undergraduate research, which occurs within the reality of each one, systematizes the four years of training, originating the themes for the course completion papers. These works can contribute to changing the reality of each territory, as they combine teaching, research and extension within the pedagogical axis. The Cultural and Humanistic Interactions module promotes the understanding of the historical processes that constitute the conflicts existing in the territories, which often allows the development of an action with the community, as reported by student Araçá, in the action conducted in Cerro Azul against the closure of rural schools, a problem that affects Educação do Campo in the national territory12.

But before starting the Program I didn’t really understand this relation. They [Department of Education] said: ‘We are going to close it because we need to save, there is no structure.’ When we started studying, we started to understand what Educação do Campo was and why that was happening […]. So, at this time of Cultural and Humanistic Interactions, we started going to the communities, started telling them what we were learning here, and we started a strong movement, you know. Some schools were not closed, there was even friction with the Department of Education. We held several meetings, several times, we read denunciation letters

(Entrevista Araçá, 2018).

This is the greatest potential of the itinerancy and alternation regime: the University, when it reaches rural communities, provides academic and political training for the subjects, and a critical-transforming intervention in reality. That is is the importance of the school of and for the people. This is one of the CT actions that contributes so students can be agents of transformation of reality. With pedagogical intention, they “[…] are divided into working collectives […]. Obligatorily, they need to meet. There are other individual ones, which involve a lot of research” (Entrevista Patrícia, 2019). It is a high workload, but the teachers are not always able to follow it, due to the reasons mentioned above.

In addition to the importance of the pedagogy of alternation and of the access of rural populations to higher education, the specificity of teacher training in Educação do Campo, with emphasis on agroecology, has contributed to questioning and breaking with the hegemonic models of agricultural production based on monoculture and on the intensive use of chemical products. The LECAMPO Program has provided reflections that strengthened or enabled the agroecological transition in the communities or families of the students.

My parents have always worked with conventional agriculture. Even today, when planting, they apply poison. Then I engaged in the Movement, I started studying. Then we started to produce, we also saw that this conventional production was not solving our situation, our way of life, […] then we started to produce without pesticides. We started taking care of things, because we had to use the material from the property, and then we produce today, without poison, without pesticides, without any chemicals, and we have a production for diversified food

(Entrevista Relatividade, 2018).

Another dimension observed in the process of decoloniality in rural teacher training is the experience of shared teaching developed at LECAMPO, in accordance with the UFPR/SL PPP, in which teachers of different disciplines work together in the development of classes (UT). “We have shared classes with biology, chemistry and physics teachers […]. We always try to look for rural practices to work with this knowledge of natural sciences” (Entrevista Luciano, 2019). “Look, from my point of view, it [the content] was covered. As I said, I didn’t have, like, chemistry, physics and biology classes, you know. […] In high school, we learn everything separately; here, everything is interconnected” (Entrevista Pitanga, 2018). The reports and the observation in loco enabled us to recognize the meaning that the knowledge of the Sciences of Nature acquires when worked in an integrated manner, in large modules and based on rural practices. In shared teaching, it can be seen that the positions and interventions of teachers “[…] emerge procedurally in the interactions between members of the collective” (Silva et al., 2019, p. 59).

Shared teaching enables the redevelopment of knowledge, as it coordinates the knowledge of social practice with knowledge by field of knowledge, generally taught in a fragmented way, by the disciplinary model and by the logic of a single method of learning and producing knowledge. It fosters an interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary and, at times, non-disciplinary – without disciplines – training, the dialogue of types of knowledge and epistemological disobedience. Despite the importance of this methodology and conception of teaching work, there is a recognition by those involved in the Program that the PPP reformulation considers that the school records should include the description of the contents worked in the Sciences of Nature, since the students, after graduation, are submitted to competitive public selection exams and private sector selection processes for job positions according to a disciplinary logic.

Final Considerations

Seeking to train teachers based on the perspective of socioterritorial diversity, LECAMPO – UFPR/SL has been built through dialogue between the participants of the entire educational process: teachers, students and pedagogical staff, considering the histories of life and previous social constructions of all persons involved. This was crucial for the program to reach the different territories where it is present. The itinerancy regime, in which the University goes to the territories, enabled access to higher education for a great diversity of rural, riverside and traditional people communities, thus contributing to decolonize teacher training and maintain the identity of an education program of/with/in rural areas.

The pedagogy of alternation, a structuring element of Educação do Campo, has been crucial in this dynamics, precisely because it functions as a theoretical-practical process that values the knowledge of social practice and the culture of the community of the student. Similarly, it has provided dialogue between different types of knowledge, and the development of actions of transformation, of resistance, with rural communities, schools and social movements. In addition to keeping students rooted in these educational spaces during the CT, pedagogical alternation has also contributed to reduce the university’s dropout/expulsion rate. In the UT, students bring the experience knowledge made and the diagnoses of reality of the stage with the community for problematization and theoretical deepening, in particular, with knowledge about the Natural Sciences, the agrarian issue, Educação do Campo, pedagogical practice, which are discussed in dialogue, generally, in an interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary and non-disciplinary way, through shared teaching and epistemic disobedience. It is the alternation that achieves the synthesis of the theoretical-practical knowledge production process.

Because it deals with the ways of existing and re-existing of rural subjects and assists in the identity process of the groups that are part of the classes, LECAMPO has the potential to train teachers who are qualified to build an education movement that considers the human education/training, whether in the school, in the family, in the community, in the social movement. The pedagogies of alternation and itinerancy reaffirm the knowledge acquired throughout the lives of students and teachers and have the capacity to resignify that which they already experience. These practices represent an instrument for scientific reading of realities, so they can intervene and contribute so all rural subjects act in the construction of knowledge, as collective learning assists in this process. Thus, there is a constant movement between realities and systematized knowledge. This changes the logic and epistemology of teacher training.

Several of the program’s advances are due to the fact that LECAMPO has its PPC based on methodologies already previously adopted in the UFPR/SL Political-Pedagogical Project, and this is evident in the Learning Projects, pedagogical axis that transforms undergraduate research into a curricular axis. This is also corroborated by the previous experiences of the Licentiate and Pedagogy of the Earth Programs in other universities and the organic linkage of some teachers with the pedagogy of social movements.

The organic relationship of the University with social movements has been substantial in changing the form and content of rural teacher training, as it is from their epistemic, social and political places of re-existence that rural subjects – as a collective in movement – announce the epistemic disobedience, of an emancipatory character. In their pedagogy of the movement, of the oppressed, decolonial, they provide other ways of learning and teaching that (re)create “[…] ancestral pedagogies, in the strength that emanates from the pedagogical circle, from doing with, from sharing, from experiencing (with), from the mystique, from the conversation round, from deep listening, from the authentic presence, and from care” (Zeferino; Passos; Paim, 2019, p. 39)13.

Notes

1For more details, see Santos (2020).

2Procampo began as a pilot experiment in four universities: the Federal University of Minas Gerais, the Federal University of Bahia, the Federal University of Sergipe and the University of Brasília.

4 Walsh (2009) mentions the issue of critical interculturality as a pedagogical tool to question racialization, subalternization and inferiorization and the power models in which they are manifested, and also to provide visibility to and legitimately constitute other ways of being, living, thinking, knowing, learning, and teaching.

5Its roots are found in the struggles and praxis of the Afro and indigenous communities, which are currently conceived as part of a political posture and project (Walsh, 2009).

6The names of the interviewed teachers are fictitious. The students were identified with symbols that name their class.

7With entrance exam in 2014. For more information: <http://www.litoral.ufpr.br/portal/lecampo/curso/turmas/>. Accessed on: April 2, 2021.

8Available at: <http://portal.nc.ufpr.br/PortalNC/PublicacaoDocumento?pub=2846>. Accessed on: April 2, 2021.

9The Pedagogy of Alternation is regulated, within the scope of the Ministry of Education, by CNE/CEB Opinion no. 1/2006.

10A pedagogical axis wherein students conduct their studies based on their life experiences and the demands of their community, through research and actions.

11In this space of learning and integration of different areas of knowledge, Seminars and Local Workshops are held, providing discussions, reflections, exchange of knowledge, bringing teachers closer to different communities (PPC, 2012).

12According to INEP data, between 1997 and 2018 nearly 80,000 schools were closed in the Brazilian rural areas.

REFERENCES

ARROYO, Miguel. Pedagogias em Movimento – o que temos a aprender dos Movimentos Sociais? Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 3, n. 1, p. 28-49, jan./jun. 2003. [ Links ]

ARROYO, Miguel. Os Movimentos Sociais e a Construção de Outros Currículos. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 55, p. 47-68, jan./mar. 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Alfabetização e Diversidade. Coordenação Geral de Educação do Campo. Licenciatura (plena) em Educação do Campo. Brasília, 2006. (texto não publicado). [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Diretrizes Operacionais para a Educação Básica nas Escolas do Campo. Brasília: MEC, 2010a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto Nº 7.352, de 4 de novembro de 2010. Dispõe sobre a política de educação do campo e o Programa Nacional de Educação na Reforma Agrária - PRONERA. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 4 nov. 2010b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução Nº 8, de 20 de novembro de 2012. Define Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Escolar Quilombola na Educação Básica. Brasília: Conselho Nacional de Educação, 20 nov. 2012. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (Inep). Censo Escolar 2017. Brasília, 2017. Disponível em: <http://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/censo-escolar>. Acesso em: 21 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

CALDART, Roseli. Pedagogia do Movimento Sem Terra. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2000. [ Links ]

CALDART, Roseli. Sobre Educação do Campo. In: SEMINÁRIO DO PROGRAMA NACIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO NA REFORMA AGRÁRIA, 3, 2007, Luziânia. Anais... Luziânia, 2007. [ Links ]

CALDART, Roseli. O MST e a Escola: concepção da educação e matriz formativa. In: CALDART, Roseli (Org.). Caminhos para a Transformação da Escola: reflexões desde práticas da licenciatura em Educação do Campo. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2011. P. 63-83. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Bernardo Mançano. Os Campos da Pesquisa em Educação do Campo. Espaço e território como categorias essenciais. In: MOLINA, Mônica (Org.). Educação do Campo e Pesquisa: questões para reflexão. Brasília: MDA, 2006. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Bernardo Mançano; MOLINA, Mônica. O Campo da Educação do Campo. In: MOLINA, Mônica; JESUS, Sônia Meire (Org). Contribuições para a Construção de um Projeto de Educação do Campo. Brasília: Articulação Nacional Por Uma Educação do Campo, 2004. [ Links ]

FONEC. Notas para Análise do Momento Atual da Educação do Campo. In: SEMINÁRIO NACIONAL, 2012, Brasília. Anais... Brasília, 2012. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do Oprimido. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1987. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

GHEDINI, Cecília; JANATA, Natacha; SCHWENDLER, Sônia Fátima. A Educação do Campo e a Diversidade Sociocultural do Campesinato. In: MIRANDA, Sônia Guariza; SCHWENDLER, Sônia Fátima (Org.). Educação do Campo em Movimento: teoria e prática cotidiana: volume I. Curitiba: Ed. UFPR, 2010. P. 177-199. [ Links ]

GONÇALVES, Michelle. Performance, Discurso e Educação: (re)construindo sentidos de escola com professores em formação na Licenciatura em Educação do Campo – Ciências da Natureza. 2016. 143 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2016. [ Links ]

GRAMSCI, Antonio. The Modern Prince and Other Writings. London: Lawrence and Wishart Ltd, 1967. [ Links ]

JAKIMIU, Camila. A Formação de Educadores(as) do Campo como Ferramenta para o Fortalecimento da R-Existência Camponesa: tecendo interpretações da realidade com a turma Albert Einstein da Lecampo da UFPR-Setor Litoral. 2018. 193 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Geografia) - Setor de Ciências da Terra, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2018. [ Links ]

JANATA, Natacha; ANHAIA, Edson. As Bases Teóricas da Educação do Campo e suas Contribuições para a Licenciatura em Educação do Campo. Cadernos de Pesquisa Pensamento Educacional, Curitiba, v. 13, n. 34, UTP, 2018. Disponível em: <https://seer.utp.br/index.php/a/article/view/1402>. Acesso em: 20 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

MARRE, Jacques. História de Vida e Método Biográfico. Cadernos de Sociologia, Porto Alegre, v. 3, n. 3, p. 89-141, jan./jul. 1991. [ Links ]

MIGNOLO, Walter. Desobediência Epistêmica: a opção descolonial e o significado de identidade em política. Cadernos de Letras da UFF – Dossiê Literatura, língua e identidade, Niterói, n. 34, p. 287-324, 2008. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Mônica. Expansão das Licenciaturas em Educação do Campo: desafios e potencialidades. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 55, p. 145-166, mar. 2015. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Mônica. Panorama das Licenciaturas em Educação do Campo nas IES no Brasil. In: RUAS, José; SILVA, Cícero; BRASIL, Anderson (Org.). Educação do Campo: diversidade cultural, socioterritorial, lutas e práticas. São Paulo: Vozes, 2019. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Mônica; ANTUNES-ROCHA, Maria Isabel. Educação do Campo: história, práticas e desafios no âmbito das políticas de formação de educadores – reflexões sobre o Pronera e o Procampo. Revista Reflexão e Ação, Santa Cruz do Sul, v. 22, n. 2, p. 220-253, jul./dez. 2014. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Mônica; SÁ, Laís. Licenciatura em Educação do Campo. In: CALDART, Roseli et al. (Org.). Dicionário da Educação do Campo. Rio de Janeiro: IESJV, Fiocruz, Expressão Popular, 2012. P. 295-301. [ Links ]

MUNARIM, Antônio. Movimento Nacional de Educação do Campo: uma trajetória em construção. REUNIÃO ANUAL DA ANPED, 31., 2008, Caxambu. Anais... Caxambu, 2008. [ Links ]

PORTELLI, Alessandro. Tentando Aprender um Pouquinho: algumas reflexões sobre ética na história oral. Projeto História, São Paulo, v. 15, p. 13-49, abr. 1997. [ Links ]

QUIJANO, Aníbal. Colonialidade do Poder, Eurocentrismo e América Latina. In: LANDER, Edgardo (Org.). A Colonialidade do Saber: eurocentrismo e ciências sociais. Perspectivas latinoamericanas. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina: CLACSO, 2005. Colección Sur Sur. P. 227-278. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Marlene. Pedagogia da Alternância na Educação Rural/do Campo: projetos em disputa. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 34, n. 1, p. 27-45, 2008. [ Links ]

ROSA, Marcelo. A ‘Forma Movimento’ como Modelo Contemporâneo de Ação Coletiva Rural no Brasil. In: FERNANDES, Bernardo Mançano; MEDEIROS, Leonilde de; PAULILO, Maria Ignez (Org.). Lutas Camponesas Contemporâneas: condições, dilemas e conquistas,.v. 2: a diversidade das formas das lutas no campo. São Paulo: UNESP, Brasília, DF: NEAD, 2009. P. 95-111. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Aline Nunes dos. A Diversidade Socioterritorial dos Sujeitos do Campo no Curso de Licenciatura em Educação do Campo – Ciências da Natureza da Universidade Federal do Paraná – Setor Litoral. 2020. 135 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2020. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. El Milenio Huérfano. Ensayos para una Nueva Cultura Política. Madrid: Editorial Trotta, 2005. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. Para Além do Pensamento Abissal: das linhas globais a uma ecologia de saberes. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, Coimbra, v. 78, p. 3-46, out. 2007. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Silvanete. A Concepção de Alternância da Licenciatura em Educação do Campo da Universidade de Brasília. 2012. 163 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2012. [ Links ]

SCHWENDLER, Sônia Fátima. Políticas Públicas da Educação do Campo na Atualidade: avanços e contradições. In.: SAPELLI, Marlene; SILVA, Jefferson da (Org.).Uma Face da Hidra Capitalista: crítica às políticas educacionais para a classe trabalhadora. Curitiba: Prismas, 2017. P. 66-99. [ Links ]

SILVA, Valentim et al. Formação de Professores em Educação do Campo: pedagogia do movimento no paradigma emancipatório. Revista de Educação, Ciência e Cultura, Canoas, v. 24, n. 1, p. 53-70, mar. 2019. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, Paul. História Oral e Contemporaneidade. História Oral, São Paulo, v. 5, p. 9-28, 2002. [ Links ]

UFPR. Projeto Político Pedagógico (PPP) do Curso de Licenciatura em Educação do Campo – UFPR Litoral. Matinhos, 2012. Disponível em: <www.litoral.ufpr.br/portal/lecampo>. Acesso em: 13 jan. 2020. [ Links ]

WALSH, Catherine. Interculturalidade Crítica e Pedagogia Decolonial: in-surgir, re-existir e re-viver. In: CANDAU, Vera Maria (Org.). Educação Intercultural na América Latina: entre concepções, tensões e propostas. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2009. P. 12-43. [ Links ]

ZEFERINO, Jaqueline; PASSOS, Joana; PAIM, Elison. Decolonialidade e Educação do Campo: diálogos em construção. Momento: diálogos em educação, Porto alegre, v. 28, n. 2, p. 28-41, maio/ago. 2019. [ Links ]

Received: June 01, 2021; Accepted: August 09, 2021

text in

text in