Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educação e Realidade

Print version ISSN 0100-3143On-line version ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.46 no.4 Porto Alegre 2021 Epub Nov 22, 2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236106890

OTHER THEMES

The Configuration of Exclusive Pedagogies in Secondary Education: analysis of critical processes in an educational center on the outskirts of Montevideo

IUniversidad de la República (UdelaR), Montevideo - Uruguay

This article studies the configuration of exclusive pedagogies in high school. The case of a peripheral high school in Montevideo is studied, carrying out an ethnography for two years. Through process-tracing, the process of educational exclusion of an adolescent in conflict with the institution is investigated, analyzing the specific mechanisms by which a series of incivilities are punished by the school institution, causing their expulsion and culminating in union, police and judicial actions. The case shows the practical forms of exclusion of poor adolescents in Uruguay and allows us to think about the relationships between inequality, punishment and recognition in the educational space.

Keywords: Highschool; Exclusive Pedagogies; Right to Education

El presente artículo estudia la configuración de una pedagogía excluyente en la enseñanza media secundaria. Se estudia el caso de un liceo periférico de Montevideo, realizando una etnografía durante dos años. Mediante process-tracing, se investiga el proceso de exclusión educativa de un adolescente en conflicto con la institución, analizando los mecanismos específicos por los cuales una serie de incivilidades son castigadas por la institución escolar, causando su expulsión y culminando en acciones sindicales, policiales y judiciales. El caso muestra las formas prácticas de exclusión de los adolescentes pobres en Uruguay y permite pensar las relaciones entre desigualdad, castigo y reconocimiento en el espacio educativo.

Palabras clave: Escuela; Pedagogías Excluyentes; Derecho a la Educación

Introduction

In the last two decades, Latin American countries have promoted legal advances seeking to ensure the right to education. Despite these efforts, limitations have been shown, particularly in relation to minorities due to economic, gender, race-ethnicity, territory, or disability. This process has been conceptualized by Gentili as an inclusive exclusion, by which:

[...] the mechanisms of educational exclusion are recreated and take on new features in the framework of dynamics of inclusion or institutional insertion, which are either insufficient or innocuous to reverse the isolation, marginalization and denial of rights involved in a social segregation scheme (Gentili, 2011, p. 78).

The Uruguayan case, with its specific characteristics, is no exception. The enactment of the General Education Law (Law 18,437 of 2008) enshrined the right and the obligation of education in the entire stretch between initial education (four years) to high school (eighteen years), without discrimination of any kind. However, and despite multiple advances, the reality of the last decade has shown that the aforementioned universalization of secondary education has not been fulfilled, and that educational exclusion continues to be a reality for the most vulnerable sectors. Thus, 66% of students do not complete secondary education as planned, especially adolescents and young people of low socioeconomic status (INEEd, 2019)

This process of educational exclusion is not only due to exogenous or out-of-school factors. Silencing, stigmatization, psychological intervention and even medicalization have shaped different forms of violence exerted by the school institution towards adolescents and young people, particularly the most vulnerable (Martinis; Viscardi; Cristóforo; Migues, 2017).

These differences between paper and practice highlight the gaps between the express curriculum and the hidden curriculum (Tadeu, 1992). In this sense, it is possible to think how, beyond the normative prescriptions, an exclusionary pedagogy is configured in everyday life, based on a series of systematic violence that hinders the equal enjoyment of education as a right.

Also, this situation renews the question of what the school produces and reproduces in relation to the social world and its inequalities. Addressing it implies opening the black box that allows knowing the concrete ways in which power is exerted in the school institution, determining the experiences and trajectories of its students. As Tadeu (1992, p. 59) pointed out:

[...] the history of critical theory in education in this period is also related to an attempt to refine the overly categorical statements that were initially made about the reproductive aspects of education. After all, it was said, in education everything contributes to reproducing what exists, thus playing its part in maintaining asymmetric and exploitative social relations. Education also generates the new, creates new elements and new relationships, generates resistance that will produce situations that are not a mere repetition of previous positions. In short, it was theorized that education not only reproduces - it also produces.

Re-asking ourselves what the school produces and reproduces is a permanent task, which currently combines a reflection on social inequality, pedagogical action and institutional violence. This implies reconceptualizing a look that emphasizes the processes of recognition in the school space, by all those who inhabit it (Viscardi; Alonso, 2013), the forms of coexistence and participation, or, in its negative form, the forms of contempt and exclusion.

This article presents a case study carried out throughout 2018 in a peripheral high school in Montevideo. The study allowed observing the institutional treatment given to resolve the situation of a student in conflict with the institution. What begins as a series of incivilities in the classroom, finishes with the paralysis of the educational center, the intervention of psychosocial teams, unions, educational authorities and, finally, the police, judicializing the situation and institutionalizing the adolescent. Tracing the discourses and micro-decisions of the actors throughout the situation seeks to reconstruct the processes by which the student is effectively excluded from the educational system, considering as well other institutional actions aimed at the inclusion of the adolescent that fail to prosper. In this sense, it seeks to understand in a pragmatic way (Corcuff, 2013) some causal mechanisms of exclusion in the school institution, based on the daily practices of its actors.

Methodology: school ethnographies

Educational centers are places of great activity, where various phenomena of relevance for the lives of adolescents and adults take place. It is, therefore, a space of meaning (Augé, 2000), where, in addition to learning, processes of socialization and subjectivation are configured (Dubet, 2006). For the adult world, the educational space is signified by a labor relationship, a field of demands, but also satisfactions. Hence, sharing the subjective gaze of the protagonists in the school experience has a particular relevance (Dubet; Martuccelli, 1996).

School ethnographies have consolidated a field in the social sciences, allowing a holistic view of school phenomena, and accounting for the relationship between what happens in schools and their environments (Bartlett; Triana, 2020; Bartlett; Vavrus, 2017; Levinson; Pollock, 2011). The ethnographic approach allows us to know the educational dynamics through which macro-processes are formed, but it is also a means of access to multiple social phenomena that escape statistics (Tadeu, 1992).

Ethnographies have nurtured the sociological research agenda, particularly in education, within which the issue of coexistence has aroused growing interest. As Perales Franco (2018, p. 3) points out: “[...] ethnography is especially suited to the task, as ethnographic accounts provide rich empirical data that could allow for theorizing about the ways in which actors engage with coexistence in relationships at different levels”. Thus, the issue of coexistence in school acquires special relevance as a phenomenon that, for its understanding, needs to reveal the gazes of the actors in a situated way.

To address these phenomena, the strategy of a single case study was chosen (Neiman; Quaranta, 2006), in its dual condition, as a paradigmatic case and a critical case (Yin, 2003). The educational center in which we worked was a medium-sized high school (400 students), located on Montevideo´s periphery, with students from housing cooperatives, urban areas and settlements. It has about forty teachers of different subjects, and an educational team, made up of a psychologist, two social educators, and three other teachers of pedagogical assistance (monitors).

In this framework, the institutional treatment of a student in conflict with the educational center was analyzed. For this, within the framework of ethnography, a methodology based on the process-tracing method was used (Bennett; Checkel, 2015). This implied that, during the year of study, not only the events that took place were surveyed (reflected in administrative instances, student sanctions, union meetings), but also the different views of actors at each moment, emphasizing their points of agreement and disagreement. The longitudinal dimension of the study allows us to understand why and how these processes took place, by which a punitive institutional response was consolidated instead of a conciliatory one, or, in other words, how an excluding rather than inclusive pedagogy is configured.

The ethnographic work was carried out during the years 2017 and, mostly, 2018, and involved making 30 participant observations, 10 interviews with teachers, principals and inspectors, 6 instances of participatory work with teachers, more than 20 workshops with students, and the analysis of various documents, such as observation notebooks, and WhatsApp conversations, provided by teachers. This article presents, fundamentally, the educational views of the conflict as institutional authorities24.

According to these guidelines, the events of the institutional conflict with the student here nicknamed Juan Corrales are chronologically narrated, seeking to analyze: 1) the repertoire of tools used by the institution to address these conflictive situations, 2) the motives of the educational authorities to use them, and 3) the way in which these tools are concatenated over time, such that they configure causal mechanisms, which determine the process of exclusion of Juan Corrales from the educational center.

Conflict Takes Place in the Center: Juan Corrales´case

During 2018, a conflict was set up that affected the entire educational community in the institution studied. This conflict, which became popular as the “case of Juan Corrales”, strongly shocked the daily lives of everyone in the educational center, was referred in the conversations in corridors, coordination and institutional spaces, and implied the action in various levels of decision: from the high school management team25, up to the Inspections and the Secondary Council26 authorities, involving unions, police and judicial actors.

From institutional sources, there is a detail of the situation of extreme vulnerability in which Juan finds himself. His family consists of his mother, who is unemployed and pregnant with her seventh child, and six younger siblings between 11 months and 16 years old. He lives in a settlement near the educational center, although he sometimes sleeps on the street. He has no relationship with his father who, after being released from prison, was reported for domestic violence and is banned from approaching the family. In this context, Juan has an intermittent link with the educational institution, having been interned in total institutions27 in previous years and found himself disconnected from the educational system the year prior to the investigation.

Juan’s case is established as a matter of discussion during the months of April to May of the studied year, due to his behavioral problems. Initially, the observations documented in the center’s Book of Discipline28 reveal minor incidents, which can be understood as “incivilities” (Debarbieux et al., 1999), such as disturbing, not being silent, insulting or not going to the principals´office when it is sent there.

As time goes by, Juan’s situation overflows the classroom and is discussed in other spaces. According to the teachers of the center, the adolescent stayed at the door of the high school, consuming marijuana; he threatened teachers and attacked other students; he stole belongings, threw stones and insulted those who entered the high school.

This prompted various actions from the educational center. On the one hand, Juan gets the record of ten observations in the Book of Discipline, which, when repeated, begin to be suspensions29. Despite this, Juan continues going to the high school´s entrance, even if he is prohibited from entering. On the other hand, the educational team makes multiple calls to his mother (Juan’s only adult reference), making agreements that, according to reports, she was not able to keep. Juan’s precarious family situation reaches such a point that his mother expresses that the adolescent is already grown up, that she does not know what to do with him, and even makes a police report for her son’s escape from their home, requesting assistance for his admission to the Institute for Children and Adolescents of Uruguay (INAU)30.

Due to this complex situation, the Educational Team tries to give a comprehensive response to Juan’s situation during the months in question. To do this, they make contact with educational support agencies of the institution, as well as with three community institutions in the area, in search of resources to support the student. However, no clear progress is made.

In this context, the teachers’ assessment of Juan begins to deteriorate, settling a negative view on him. While he has acceptable, and sometimes good, academic results, his overall evaluation is not approving due to his misconduct. Towards the end of May, most of the teachers share the opinion that Juan is a bad student, and that he disturbs the order of the institution. This configures a process of weakening of the pedagogical bond that triggers a spiral of tensions between the student and the teachers in the educational center. Thus, a stigmatization process is established (Goffman, 2008): Juan finds himself in conflict with the institution.

Beyond this consensus, the nature of this conflict and its possible solutions find, at this stage, different interpretations by two groups of teachers. This duality of the views on the conflict with Juan is clearly expressed by two teachers, in an interview conducted on May 15:

Teacher 1: there are two readings of the situation: one is why don’t we contain it… because it is the only place of reference? ... Teacher 2: You can’t contain it ... Teacher 1: And there is another reading, I endorse the second reading: there are certain minimum rules here that have to be maintained. I agree (Interview, May 15, 2018).

This first group of teachers understand that the adolescent does not accept the minimum rules, has shown bad intentions and little commitment. Although they admit that the adolescent shows interest in going to the educational center, they understand that the institution cannot contain the student, and that trying would be a waste of time or a self-deception. Within the framework of ethnography, it is also possible to identify that this group of teachers expresses a very negative perspective of students and their families:

Teacher 2: Drugs, family... it already gives me the impression that they come drugged from the womb. So, you can’t give them anything and you talk to the parents, in this case there are many single-parent homes, it seems to me that they do not take care of this problem at all. [...] parents do not show up, at best they show up and tell you that this is totally normal (Interview, May 15, 2018).

On the other hand, a second group, formed around the Educational Team, also recognizes the existence of these two views on the conflict with Juan Corrales, although they conceptualize it in the opposite way:

Teacher 3: the mother had sent him to the INAU, because the mother could not cope with him and it was complicated. Of course, sometime later we see here all that happens at the door, that is, he is all day there at the door, and here in the high school we do not receive him, on the contrary, we take him out. And look, at one point I also took that “let’s get him out” speech, because at one point I also saw that they were annoying31 and that they have to go, they have to go. Then I say: no, folks32 are here for something, they are at the door for something, why don’t we try to get them to come in and do something useful? The issue is, well, what resources are there, we thought there weren´t many. But now I realize we have a lot: we have chess, we have garden workshop, we have theater, we have choir, and I say, well, what can we do with all this, right? The issue is the same: for them to be here there has to be a change, because the attitude they have there is not the same that they will be able to maintain here, so that change cannot be now, it takes a while, and that tolerance ... times are not tolerated here (Interview, May 18, 2018).

As can be seen, Teacher 3 starts from understanding the student’s situation to later analyze the role that the institution should have. Likewise, she expresses a self-criticism about the action of the teaching group and the educational institution, she manages to recognize other educational tools existing in the institution and reflects on different actions to be taken. In them, she emphasizes the need for a personalized approach to the student, tending to dialogue, maintaining the search for dialogue with the family, and discussing the forms of inclusion of the adolescent in the center. It is along these lines that a key element is identified as part of this task: time.

In the month of June an event occurs that increases the conflict and that will be key in the process to be analyzed: Juan locks up one of the teachers with his class. She is Teacher 1 (cited above) who expresses the most severe position in relation to Juan’s continuity in the institution.

In this event no one was harmed. Essentially, the routine of the educational center was altered, and it was solved by requesting Juan to hand over the classroom key. Despite the ease of resolution, the event further stresses the already tense climate, generating greater discomfort around Juan Corrales’ problem: synthetically, teachers demand that something must be done with him.

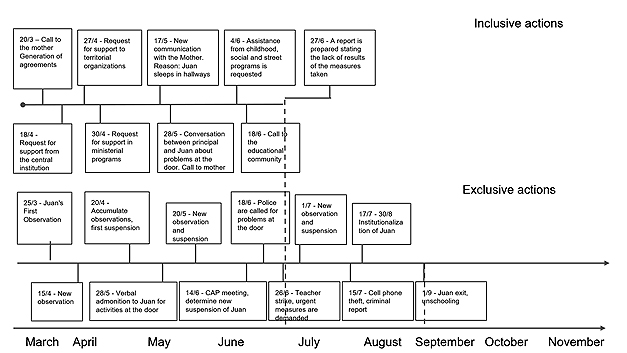

From the two positions previously mentioned, two simultaneous treatments of the problem are generated: on the one hand, the Educational Team continues trying to manage the conflict from an inclusive approach, seeking to contact family members, meeting with the adolescent, and exploring institutional support. On the other hand, simultaneously, the complaints of multiple teachers lead to Juan’s situation being addressed by the Pedagogical Advisory Council (CAP)33. The CAP resolves the suspension of the student, and, consequently, his removal from the center, and the impossibility of the other teachers continuing talking with him. In other words, the Educational Team’s negotiations are finished.

From an extemporaneous approach, it would seem that the institution fulfills its duty, using a wide repertoire of actions to resolve the situation at hand. However, based on a more detailed analysis of the process and the views of its participants, we evidence the tension between the demands of the different teaching groups regarding the processing of the conflict. Furthermore, it is clear how the promotion of some measures implies the obstruction of others.

In a synthetic way, the dichotomy is posed in terms of dialogue or punishment, which Viscardi (2014) expresses as a tension between a mobilizing side and a social defense side. In relation to the effects of these actions in the educational trajectories, here we conceive them as an inclusive side and an exclusive side.

The inclusive side, supported by the Educational Team, is based on the guarantee of the right to education in a universal way, puts the student at the center, and questions the ways in which the institution can be hospitable with him. This implies some challenges: adapting to unexpected problems, and developing non-prescribed institutional functions, such as providing food, playing, or working with the community.

On the contrary, the exclusive side, defended by other teachers, and institutionalized in the action of the CAP, has as its center the institution and its leaders, and emphasizes discipline and school rules. They recognize social problems outside their job skills, which are restricted to the task of teaching (Dubet, 2006). The discourses that are framed in this side do not express exclusion as an objective but, by emphasizing the rules and conditions of permanence, as well as the deficits of those who do not comply with them, the idea of ineducability of the subjects is stated (Baquero, 2001) and their impossibility of permanence in the educational system.

In terms of institutional resources, the differences between both sides are clear: on the one hand, the generation of spaces for dialogue, calls to family members, socio-educational activities, working with the community; on the other, the stigmatization, silencing, observation, suspension and transfer of institutions. The effects in terms of the exercise of the right to education are also clear: at the poles is the fact of staying inside or outside the educational system, but between these are the exclusive-inclusive relationships (Gentili, 2011), which imply weak bonds between students and institutions, as in the process here analyzed.

In Chart 1 we list some institutional tools that, in the light of this process, configure both pedagogies.

Chart 1: Institutional tools to work with the conflict

| Inclusive | Exclusive |

|---|---|

| Generation of spaces for dialogue | Stigmatization |

| Call to relatives | Silencing |

| Socio-educational activities | Observation |

| Meeting with community organizations | Suspension |

| Search for inter-institutional support | Transfer to another institution |

Source: Own elaboration.

Student Is Outside, Conflict Continues

The suspension decreed further stresses the atmosphere of coexistence in the center, understanding that the absence of the adolescent implies the impossibility of continuing working with him, and increases the distance between him and the institution. In the words of a teacher on the Educational Team: the high school closes the door on the adolescent.

Despite these measures, on the days in which the student is suspended, he continues to attend without being able to enter, simply hanging out at the door34. It is in this context that, in the third week of June, another decisive episode occurs with Juan, which is described in the field notes of June 26, 2018.

Field Notes - June 26, 2018. I go to the educational center. Classes are not being taught. Teachers have taken an active strike as a union measure and are in assembly. It is due to another problem with Juan Corrales, although the situation is not clear. I simultaneously relieve different versions of the problem. The teachers are not clear if Juan is still suspended. Some say that the problem is that Juan entered the center while suspended, others that he smoked marijuana in the bathroom, others that he hit a bird with a stick on the school grounds, and others that he had a fight with the stick with the monitor35. The different teachers gathered here inform me of different things simultaneously. This incongruity in what happened is relevant, since it motivates the union action that is taking place. A union delegate comes to organize the demands The version that is being agreed throughout the assembly is that the reason for the strike is due to the fact that Juan enters the high school without authorization, as he is suspended. Later, a quarrel is generated with the monitor, who takes him to the principal. There Juan threatens to scratch the principal’s car if he is removed from the educational center. Given this, the principal grants him permission to remain in the center. Meanwhile the teachers characterize Juan, although it is not clear what is the relationship with the event. It is emphasized that Juan uses drugs, and it is discussed what drugs he uses. They also talk about Juan’s past hospitalization in a health center for addictions. They comment on chemical drugs and medication in the health center. Below are some conversations that account for Juan’s conceptualization by some teachers: Teacher 6: Guys are medicated badly, they end worn out36 for a few days, and so they are all down... Teacher 7: After that he walks all like crazy. Teacher 6: yes, because of the abstinence. Teacher 8: Why doesn’t he want to take the pills if he smokes pot37 and does coke38? Teacher 7: He doesn’t even like legal drugs. Teacher 8: didn´t his father used to sell39? Juan has gone through the corresponding instances in the center40. The authorities are held responsible (from the Inspection to higher levels) for the lack of answers. The principal is also blamed for not supporting the teaching actions and giving in to the student pressure, disavowing the decisions taken by the teachers. Likewise, a new call to the mother is mentioned, who again expresses her inability to take action. Teacher 10 recounts the meeting with Juan in the morning I went out and he was smoking a joint at the door, he took my car key out and I had to take it from him. He tells me: -Did you see how fast I am? And I said - Ah! you take advantage of an old man (it’s a joke, since the teacher is young) and well, that was it. Teacher 11 tells a colleague about previous problems generated by Juan. Teacher 11: I feel sorry for student Andrés, who left us because they harassed him at the bus stop. Teacher 4: Yes, he told me that they told him “hey chubby butthead41”, do you remember that he didn’t went out on the breaks, he stayed with you? Teacher 10: I said to him: Why didn’t you tell us that this was happening to you? And he looked at me (Teacher 10 makes a skeptical gesture). “Yeah, sure, I’m going to tell you” (pointing ironically that he wouldn’t). Yes, that is a shame. Teacher 4: In the end, you end up worrying about Juan all the time and you don’t know what happens to other students who do work. Other teachers comment on Juan’s situation: The union representative expresses: Teacher 12: We don’t want him here. What’s the matter with him? Let the authorities take charge, we don’t want him here. Others complement this position: Teacher 14: He has already completed a cycle here. Teacher 13: We do not want to demonize him, he is an abandoned guy42, the issue is how far it is our responsibility and how much it is on the authorities, he is a boy who we do not know how to support, and there are other frightened classmates, a father took out his son [of the educational center]. Teacher 15: We are adults, he is in a state of fragility, we are not even doing him well. Another teacher comments in relation to the union action taken that day: Teacher 13: We go on strike to make the situation visible, because we are like this for months, he was already in Tribal43 and we don’t want him to go back there, but it is unsustainable. The idea that there are not adequate conditions for Juan to remain in the center adds more arguments and is gaining consensus: Teacher 10: I feel sorry for the guy44, because he is annoying, but deep down he does what he can and we give him contradictory messages. In contrast to what has been said so far, one of the social educators of the center, who has been expressing her disagreements with the treatment of the matter so far, speaks. In this regard, she says angrily: Educator 1: The problem here is in the adult world. If this student cannot stay here today, it is due to the responsibility of the institution [and she adds] - Such a power does this student have… he alone is stopping the entire institution. After saying this she leaves the assembly. Finally, it is possible to identify teachers who do not express an opinion because they are unaware of the problem. Teachers who do not have Juan as a student, or who have very few hours at the center and ignore the conflict. Some of them come to the teacher´s room and do not understand what is happening, they observe for a while and leave, it is unknown whether to go teaching or to abide the strike, they just leave the center. Towards the afternoon, the principal leaves. He has not spoken to the teachers. Regarding the subject, Teacher 12 expresses annoyed: Teacher 12: There is no authority here, there is a man who is the principal, but the center is headless, there is no authority. Teacher 10 adds: Above all he was running away. As the day progresses, teachers with less workload in the center, or with classes in other centers leave. In the night, only one of the teachers of the center remains, along with the union delegate. The day ends with a letter to the authorities and to the family, declaring the reasons for the active strike.

This field note is chosen to help understand the different assessments that exist about the situation and its subsequent outcome. This is the highest point of the conflict, when it goes beyond the center’s orbit of action and directly involves union actors and the Inspection of the Secondary Education Council.

A first element that draws attention to this event are the multiple versions that circulate around the problem with Juan, which motivates the strike. Different teachers explained different reasons as the cause of the problem. It appears that, more than a concrete demand, what gathers the teachers at that moment is a feeling of malaise. They are irritated. Juan’s theme has become known, taking on increasing importance in the daily life of the center, generating annoyance and collective impotence

This adds important elements to think about, in terms of how institutional actions are developed from a defined role play, where management is crucial. It is possible to think that, had it had an adequate institutional treatment, the conflict as has been narrated up to now, would not have taken place in the educational center. On the other hand, the conflict exposes a structural problem already addressed in previous works (Viscardi; Alonso, 2015) regarding the role of the principal in high schools’ centers and the existing tensions to exercise his authority. Usually in charge of large institutions, the Secondary Education principals are figures of great authority in institutional architecture. They are responsible for high schools that many times have more than 150 teachers and 300 students. The teaching body in Uruguay is a strong and organized group. Many times, to carry out management decisions, the weight of this authority contrasts with the specific mechanisms they have to implement a model of institutional development in the center.

Analyzing what was expressed by the teachers, the growing distance between the institution and Juan begins to make it clear that his continuity in the center is not viable, despite why this conclusion is reached for each person. The principals’s performance is not perceived as protection and care, but as a weakness in the face of pressure and violence. The principals’s own speech supports it: it is not pedagogical, in the sense outlined by Martinis and Falkin (2017), but authoritarian and at the same time ineffective. Different teachers, at different times, can speak both from an inclusive and exclusive perspective. Of course, some of them position themselves more clearly on one side or the other.

Beyond these positions, the tools of the exclusive side have greater institutional and factual effectiveness, are better known by the institution and are clearer in their effects (even if they do not solve the underlying problem): disruptive behaviors are observed and they are noted in their corresponding notebook, memory of the institution. Faced with reiteration, the CAP acts, suspending the student’s presence at the center for some time. What happens when he comes back? If the bond has not been restored (most likely given the distance marked by the suspension) the sanction is repeated, establishing another distance. Finally, the result is a shared diagnosis that, either because of the student’s attitude or because of the incapacity of the institution, Juan cannot remain in the educational center. However, analyzing the process in its stages, we can understand this situation as the obstruction of actions on the inclusive side by actions on the exclusive side. Thus, a conflict is established in the field of the institution between two sides that, finally, converge in the exclusion of the student.

None of the teachers expresses the willingness to exclude. In the collective discussion, different speeches coexist: those concerned for safety in the center and the bad actions carried out by Juan, and those worried about Juan´s situation, emphasizing his right to education. However, in practice, we find that this right has its limits when it is faced with these extreme situations.

A first limit is established by the abdication of the effective possibilities of educating. Mentioning the many difficulties and shortcomings of Juan and his family, his dangerousness, his drug use, his lack of support, emphasizing the rejection that he generates, it is assumed that the center’s teachers can no longer educate him. A second limit is built under the student-versus-student logic: guaranteeing Juan’s right may imply undermining the rights of other students who are harassed and threatened by him. But a third (and paradoxical) limit is expressed in terms of Juan’s own right to education. Being his bond with the institution eroded and being, in practice, the exclusive side winning over the inclusive side, the diagnoses find a common point: - in fact - there is no longer a place for Juan and he must leave the educational center... for his own good.

As part of the progressive expulsion of Juan, the result of this instance is his new suspension of attendance at the educational center, the culmination of the actions of the socio-educational team, and a union demand to the High School Inspection to intervene.

The Judicialization of Juan

During this new suspension, Juan entered the educational center again. This time he does it with a table knife, causing a shocking episode. According to the teachers, he would have carried the knife for fear of reprisals from neighborhood gangs with whom he had problems, although these interpretations are only probable.

In this tense situation, the vice principal of the center asks Juan to hand over the knife, a request that he rejects, and then she asks him to put it in his bag, to which he agrees. In the bustle of the discussion, Juan steals the vice principal’s cell phone and leaves the school. From there, Juan enters the teachers’ WhatsApp groups, reading the comments made about him, commenting on those groups and also making threats to some teachers and officials who had been particularly hard on him in the group’s comments.

Having configured a crime from the theft of the cell phone, the educational center proceeds to report the act of violence to the Uruguayan Adolescent Institute (INAU), which implies the rupture of the dialogue with the family in a definitive way, as well as certain loss of prestige and legitimacy of those who sought to dialogue with them. In practical terms, it is not possible to maintain a dialogue for the good of Juan, if in parallel the institution is in a process of reporting him with the police. Likewise, these events consolidate a rupture in the institutional bond between the educational team (especially the technicians, the non-teaching team) and the rest of the community, considering that his work has not been respected.

Since the episode of the teaching assembly mentioned in the field note, the Inspection has followed the situation. In an interview with the hierarch, it is pointed out that the decisions made are lived with great sadness, as they represent a pedagogical abdication. The Inspector defends a pedagogical line of hospitality. However, according to the outcome that occurred, as well as the demands generated, the report made is attached. Thus, at this stage of the process, the conflict is settled in court.

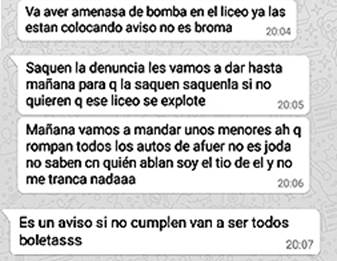

In parallel, the repercussions continue in the educational center. When Juan was notified of the police report, he used the stolen cell phone to write in the high school teachers´ WhatsApp group of, threatening them to remove the report:

The message gives rise to speculation. Most likely, Juan is lying and it is just a false alarm. However, in this context, these threats reinstate the fear of the increase in violence in the center and the anguish at the outcome. Simultaneously, the operators of the judicial system that had already been invoked take action, in the light of this new episode of theft that implies a violation of criminal law46. The adolescent, with no adult references to answer for him, and in direct conflict with the institutions and with the law, is admitted to an INAU center.

The process of judicialization and institutionalization of Juan occurs between the months of August and September. From this moment on, the educational center has no further institutional contact with him. Through personal contacts of teachers with other close people, it was possible to know that Juan spent a month in the INAU center, generated agreements with the institution that he breached and later committed new crimes, for which he was admitted to a youth detention center.

A final element that is relevant for the analysis proposed here refers to the conversations held with teachers on the last school day of the year. When asked about the educational challenges generated from situations like Juan’s, a teacher expresses: This is an issue that no longer reflects the situation of the high school, it has already been solved.

This calm situation is in direct contrast to the tension experienced during the year. It seems, however, that it has been absorbed, normalized, as part of the regular problems of the institution. This generates some perplexity. How is it possible that a group shocked by insecurity and violence has turned the page in such a short time? It seems that the notion of solution emerges from the perspective of the school as a system, which no longer has the conflict with Juan at its core. On the contrary, in terms of guaranteeing education as a right, for Juan’s case, it is quite clear that the problem was not solved.

In Chart 2 we present a timeline with the events analyzed:

Conclusions

In this chapter we describe the conflict that took place between the educational institution and a student, whom we have named Juan Corrales. We detail the social process of production of school exclusion, as it occurred in this case. This conflict grows during the year: at the beginning of it, a negative assessment of the institutional agents was evidenced, to this is added the observation of incivilities in the classroom (Debarbieux, 1999), the suspension of Juan and, later, his judicialization and confinement in total institutions.

The final outcome, already known, is the result of an interaction between student, family, and institution. However, process-tracing analysis allows us to understand in greater detail the outcome of the situation, the moments, the actions and reactions, and the consequences of each event. In this sense, it is of particular relevance to draw attention on the actions that the institution makes, not only because of the asymmetry of power in relation to the student (that establishes a pedagogical relationship) but because of its intrinsic responsibility to universally guarantee the exercise of the right to education. Thus, we reconstruct the pedagogical perspectives comprised between an inclusive and an exclusive side, confirming the prevalence of the exclusive side based on institutional mechanisms of greater symbolic and practical efficiency, which invalidate inclusive actions.

We understand that, from a broad perspective of education as a right and, additively, of the educational center as a space for the exercise of rights, the analyzed process allows us to understand the ways in which exclusive pedagogies are configured in practice. This statement, however, requires four clarifications about the way in which these exclusive pedagogies are constructed in the everyday school life.

First, a reflection on the context. As a result of the methodological approach through case studies, we can know the problems and responses in a situated way, that is, how they interact with a context (Bartlett; Vavrus, 2017). It is clear that the event studied represents an important educational challenge. The work of the high school is developed in a framework of vulnerabilities so great that it implies, in practice, the material, emotional and cultural lack of protection of the adolescent, without support of his family among other inexistent networks. Juan’s is not a habitual case, but a critical one and, from this condition, it allows us to reflect on the educational scope and limits of secondary institutions. This reflection is relevant given that the universalization of education implies the growing presence of students similar to Juan.

Second, a reflection on the way in which these exclusive pedagogies are manifested in the school space. From the ethnographic study it is possible to observe that, at various times, the excluding actions resist being enunciated, and therefore perceived by discourse analysis. Their identification is achieved only from the systematic contrast of the discourses with each other and with the events. And even in these processes, the enunciation of exclusion appears to be mediated by practical justifications, which place the responsibility on the disruptive student, on the lack of tools, on the family’s shortcomings. In other words, no teacher expresses the will to exclude, however, analyzing these processes, we find that the school institution collaborates in excluding, or at least, in these critical cases, it fails to include. As Tadeu (1992) pointed out, this again reminds us of the importance of going to the classroom, and putting the focus on the practices, and the experience of the subjects, to know the ways in which education is experienced. Ethnographies are very useful in this. By transcending the speeches, the process shows the power of the institution deployed to exercise mechanisms of coercion, denunciation and expulsion.

Third, a reflection on teaching work and the institutional logic of exclusion is relevant. In line with the previous point, these exclusive pedagogies are not the result of the actions of one teacher. The teaching role is characterized by unity in diversity: in their abilities, experiences, conceptions about the classroom, about students, conflicts, participation, and also in the vulnerabilities that teachers have. Juan´s case shows that the configuration of exclusive pedagogies is not the result of one observation of a teacher to a student in his class, but of the institutional response that the educational center provides to its students as a hole (Rivero, 2013). The logic of the center is the one that prevails, which is why the unit of analysis of this study is the educational center. The teacher contributes to this dynamic with what they do in their class, but the other institutional agents (Educational Team, teacher coordination, CAP, direction) refer to the center, and there lie the actions that can be configured as exclusive or inclusive mechanisms. This puts into focus the role of the principal as a leader of the pedagogical processes that take place in the center, including the promotion of a dialogue climate between all the people who inhabit the school space. Having emphasized the fundamental character of the center as a unit of meaning, it is possible to establish that individual actions collaborate pragmatically with what happens in the center (Corcuff, 2013): can captivate or repel its students, but must be analyzed in relation to what they contribute to the dynamics of the center.

In turn, these actions must be understood within the framework of an institutional architecture whose analysis shows contradictions between the authority that is formally deposited in some key actors, such as the principal, and the real source of their power. In this case, the dynamics and pressures exerted show the use of various mechanisms of coercion in collective situations of irritation, discomfort and fear that are not only typical of this institution, but of multiples secondary schools. The intervention of the CAP, the center’s psychologist, the teaching community, the union, and the inspection contrast with the absence of other groups that are important in the General Education Law: parents, the educational community and students. Thus, it is possible to understand the process that is exposed as a social production of school exclusion, highly linked to the lack of tolerance towards the challenging actions of the vulnerable student, by the activation of power mechanisms after an internal process of collective debate between teachers, in which neither parents, nor students, nor the community, have a voice.

Fourth, a reflection on the inter-institutional framework for the protection of children and adolescents is necessary. Considering the situation as a whole, the case of Juan refers us to an analysis of the educational center in a broader framework of institutions that guarantee the rights of children and adolescents. Along the way, Juan gave signs that something was wrong, in his family, in his networks, and in the territory. The educational institution studied favored, in practice, punitive responses over inclusive ones. It failed to establish itself as a space for listening and treating these problems, despite which Juan continued going over and over to the high school, even if it was just to hang out at the door. In short, it failed to be a space for the exercise of rights. By analyzing the process, however, we can know not only the result, but also those initiatives that did not last. Thus, at the same time that we verify these exclusive logics, we recognized the important inter-institutional efforts of the educational team, which contacted neighborhood organizations, as well as other areas of the institution itself. The prevalence of the exclusive side is also due to the lack of responses from the inclusive side, which ultimately needs an institutional network with much greater power.

Making these clarifications, we can visualize the conformation of an exclusive pedagogy, as part of exclusive-inclusive processes that, in short, links social inequalities with educational inequalities. For Gentili (2011), this inclusive exclusion is the result of three processes: 1) the combination of poverty and inequality, 2) the fragmented development in its quality of school systems, 3) a privatistic and economistic conception in the promotion of political culture of human rights. These three elements emerge in the analysis of Juan’s situation when 1) we verify that the system works adequately for many, but is very severe with those who cannot adapt to its dynamics, 2) the reasons for decoupling have socioeconomic links, 3) the containment capacities of the educational system in the face of these problems are less in the spaces of greatest need, 4) the speeches about problems such as Juan’s are read in the light of the student’s failure, and not the responsibility of the institution; 5) There is no voice or participation of vulnerable groups whose right to education is affected (students, their parents and the community).

To finish, from the analysis we show that this result, not stated as part of an express will to exclude, is not exclusively framed in the classroom, but is the result of a social process of production of exclusion that cannot be understood nor analyzed from the sole practice of one teacher. It must be studied taking the educational center and the set of actions of its agents that go from the attention of the door to the filling of the notebook, passing through the observation of the breaks, the disciplinary council, the management and the teaching room, the coordination space, the multidisciplinary team, the neighborhood associations and organizations, the police and the judicial system, among others. It is the result of the practice of the school institution as a system. In this sense, it is necessary to think of two school curricula that coexist. At the formal level, the educational system is open and universal, however, cases like Juan’s show us the operation of an exclusive hidden curriculum. Its understanding obliges us to focus on the set of institutional practices since, otherwise, the notion of hidden curriculum can be interpreted as an unexplained intentionality of a teacher. And school exclusion is not the result of the conception or practice of an individual, but of a system of actions that are articulated at a more complex level, which is the institutional one.

This becomes visible, in the first place, from the ways in which the educational subject of the institution is conceived and enunciated, its material possibilities and its social and cultural reality. Several of the adjectives outlined in this work show a pejorative and stigmatizing look (Goffman, 2008), which emphasizes their shortcomings, not in terms of an educational problem to be solved, but in terms of their inability to precisely participate in educational problems. This situation of inadequacy in the education of adolescents, particularly of the most vulnerable, is perceived by adolescents as their own shortcomings, and not as problems of the system. They bear the blame for their school failure (Rivero, 2015), thus achieving that they internalize and subject this social failure as personal failure (Bourdieu; Passeron, 1995).

Second, the case studied here emphasizes the mechanisms of an exclusionary pedagogy that is part of a culture of punishment (Viscardi, 2017) in the educational institution today and that operates as a reproducer of inequalities at the lower limit of the pyramid. Institutionally legitimate tools, such as observation or suspension, can have pedagogical results contrary to the objective sought, which is to generate positive attitudinal changes in the student.

Finally, from the case, the difficulties of sustaining the trajectories of students like Juan’s are evident. This implies attending to the diversity of situations in the classroom, and working on the integrality of the subject, in short, based on subjectivity policies (Tedesco, 2008), which implies a rethinking of the institution, its tasks and capacities. Likewise, multiple facets of school suffering are revealed, which translates into the weakening of the pedagogical bond, the stigmatization of problematic students and the daily suffering of teachers that consolidates the processes of job precariousness.

The studied elements bring great questions about the mechanisms to be developed so that the school is a space for the recognition of adolescents and their culture (Viscardi; Alonso, 2013), allowing more and more people like Juan to really have a place in the school place.

REFERENCES

AUGÉ, Marc. Los no Lugares. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2000. [ Links ]

BAQUERO, Ricardo. La Educabilidad Bajo Sospecha. 2001. Disponible en: <Disponible en: http://www.porlainclusionmercosur.educ.ar/documentos/educabilidadCuadernos-Baquero.pdf >. Acceso en: 25 Ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BARTLETT, Lesley; TRIANA, Claudia. Antropologia da Educação: introdução. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 45, n. 2, 2020. [ Links ]

BARTLETT, Lesley; VAVRUS, Frances. Rethinking Case Study Research a Comparative Approach. New York: Routledge, 2017. [ Links ]

BENNET, Andrew; CHECKEL, Jeffrey. Process Tracing. From metaphor to analytic tool. London: Cambridge University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre; PASSERON, Jean Claude. La Reproducción. México D.F: Fontanamara, 1995. [ Links ]

CORCUFF, Philippe. Las Nuevas Sociologías. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2013. [ Links ]

DEBARBIEUX, Eric et al. La Violence en Milieuscolaire. Tome 2. Le Désordre des Choses. Paris: ESF, 1999. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. El Declive de la Institución. Profesores, sujetos e individuos en la modernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa , 2006. [ Links ]

DUBET, François; MARTUCCELLI, Danilo. En la Escuela. Sociología de la experiencia escolar. Buenos Aires: Lozada, 1996. [ Links ]

GENTILI, Pablo. Pedagogía de la Igualdad. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI , 2011. [ Links ]

GOFFMAN, Erving. Estigma: la identidad deteriorada. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 2008. [ Links ]

INEED. Informe sobre el Estado de la Educación en Uruguay 2017-2018. Montevideo: INEEd, 2019. [ Links ]

LEVINSON, Brandley; POLLOCK, Mica (Ed.). A Companion to the Anthropology of Education. Chichester. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [ Links ]

MARTINIS, Pablo; FALKIN, Camila. Aspectos pedagógicos y de política educativa involucrados en los procesos de universalización del derecho a la educación. In: MARTINIS, Pablo; VISCARDI, Nilia; CRISTÓFORO, Adriana; MÍGUEZ, María. Derecho a la Educación y Mandato de Obligatoriedad en la Enseñanza Media: la igualdad en cuestión. Montevideo: CSIC-UR, 2017. [ Links ]

MARTINIS, Pablo; VISCARDI, Nilia; CRISTÓFORO, Adriana; MÍGUEZ, María. Derecho a la Educación y Mandato de Obligatoriedad en la Enseñanza Media: la igualdad en cuestión . Montevideo: CSIC-UR , 2017. [ Links ]

NEIMAN, German; QUARANTA, German. Los Estudios de Caso en la Investigación Sociológica. In: VASILACHIS, Irene (Coord.). Estrategias de Investigación Cualitativa. Barcelona: Gedisa , 2006. P. 213-237. [ Links ]

PERALES FRANCO, Cristina. Abordagem Etnográfica à Convivência na Escola. Educação & Realidade , Porto Alegre, v. 43, n. 3jul./set. 2018. [ Links ]

RIVERO, Leonel. Proyecto Pedagógico, Legitimidad & Control. Exploración de la violencia en dos liceos montevideanos. 2013. Tesis (grado de la Licenciatura en Sociología), FCS - UdelaR, Montevideo, 2013. [ Links ]

RIVERO, Leonel. ‘Trayectorias educativas tras el concepto ni-ni’. Cuadernos de CCSS & PPSS, Montevideo, Tomo I, MIDES-UR, 2015. [ Links ]

TADEU, Tomaz. O Que Produz e o Que Reproduz em Educação. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1992. [ Links ]

TEDESCO, Juan Carlos. ¿Son Posibles las Políticas de Subjetividad? In: TENTI FANFANI, Emili. Nuevos Temas en la Agenda de Política Educativa. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI , 2008. P. 53-64. [ Links ]

VISCARDI, Nilia. ‘Entre la defensa social y las vertientes movilizadoras’. In: BOADO, Marcelo. El Uruguay desde la Sociología XIII. Montevideo: DS-FCS-UdelaR, 2014. [ Links ]

VISCARDI, Nilia. ‘Adolescencia y Cultura Política en Cuestión. Vida cotidiana y convivencia en los centros educativos’. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, v. 30, n. 41, p. 127-158, julio-diciembre 2017. [ Links ]

VISCARDI, Nilia; ALONSO, Nicolás. Gramáticas de la Convivencia. Montevideo: ANEP, 2013. [ Links ]

VISCARDI, Nilia; ALONSO, Nicolás. Convivencia, Participación y Formación de Ciudadanía. Un análisis de sus soportes institucionales en la educación pública uruguaya. Montevideo: ANEP , Mosca, 2015. [ Links ]

YIN, Robert. Case Study Research, Design and Methods. London: Sage Publications, 2003. [ Links ]

1To facilitate reading, quotations of words expressed by teachers will be included in quotation marks and italics, only referring to the teacher when an entire sentence or dialogue is cited.

2From now on we call this secondary school a high school, as it is used in popular language. Sometimes we write “center” or “educational center” to emphasize its case based logic.

3The secondary education system in Uruguay has the following hierarchical spaces: management of the educational center (principal´s office), inspections, and the Council of Secondary Education.

4Some of them, despite being within the system of the Institution for Children and Adolescents of Uruguay (INAU), have been denounced for their degrading treatment and inhuman conditions.

5The Book of Discipline is the document where the observations of misconduct in the educational center are registered by teachers and other institutional actors.

6The observation implies a formal warning to the student, in cases of reiteration a suspension is applied, which, usually, implies the temporary withdrawal (a few days) of the student and his inability to attend the center.

7The INAU is in charge of managing the policies of children and adolescents in Uruguay. In this case, the adolescent’s application for admission to a shelter under its dependence is indicated.

10As established in the Student Statute, the Pedagogical Advisory Council considers student behaviors, acting as a consultative body for the principal´s office, and suggests actions to be taken in different situations.

12The monitor (in Spanish “adscripto”) has tasks of monitoring the classes and students in the educational center in Uruguay.

13In Spanish “planchados” colloquial expression that implies that adolescents cannot move due to psychiatric medication.

20A shelter of the Institute for Children and Adolescents of Uruguay (INAU) denounced for inhumane conditions. <https://www.elpais.com.uy/que-pasa/mal-dia-tribal.html>.

22Transcription (with spelling mistakes in the original, marked with*): There is going to be a bomb threat they are already placing them notice it is not a joke; Get the report out we are going to give you until tomorrow to take it out take it out if you don’t want this high school to explode; Tomorrow we are going to send some minors [under age adolescents] there tu* break all the cars outside it is not bullshit you don’t know who you are taking* to i’m his uncle and nothing blocks meee*; It is a warning if you do not comply they will all be whackeddd*.

Received: August 27, 2020; Accepted: August 11, 2021

text in

text in