Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Realidade

versão impressa ISSN 0100-3143versão On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.47 Porto Alegre 2022 Epub 25-Fev-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236108942

OTHER THEMES

Poverty and Resilience in the Narratives of Homeless EJA Students

ISecretaria de Educação do Distrito Federal, Brasília/DF – Brazil

IIUniversidade de Brasília (UnB), Brasília/DF – Brazil

Poverty and Resilience in the Narratives of Homeless EJA Students. This article shows the concepts of poverty and resilience of homeless students enrolled in the education program of the youth and adults (EJA). The study, shows the result of a master’s thesis, contextualizes the exclusion of this population in the Federal District, and presents the use of narratives as a way of giving voice and visibility to these people since they are invisible to society and to the census. As a result, the students’ narratives match the census data from the last census carried out in the Federal District, acknowledging, according to these students, people with rights capable of narrating, reflecting, and reframing their human and social condition, based on their life stories.

Keywords: Youth and Adult Education; Homeless People; Poverty and Resilience

Pobreza e Resiliência nas Narrativas de Educandos da EJA em Situação de Rua. O presente artigo relaciona os conceitos de pobreza e resiliência no estudo de educandos em situação de rua matriculados na Educação de Jovens e Adultos (EJA). O estudo, fruto de dissertação de mestrado, contextualiza a exclusão vivenciada por essa população no Distrito Federal e apresenta, na pesquisa qualitativa, as narrativas como forma de trazer as vozes e visibilizar esses sujeitos, uma vez que estes são invisibilizados socialmente e de forma censitária. Como resultado, as narrativas dos educandos dialogam com os dados do último Censo realizado no DF, reconhecendo, na palavra desses educandos, sujeitos de direito capazes de narrar, refletir e ressignificar a sua condição humana e social a partir de suas histórias de vida.

Palavras-chave: Educação de Jovens e Adultos; Pessoas em Situação de Rua; Pobreza e Resiliência

Introduction

Youth and adult education is an educational program that integrates basic education for young, adult, and elderly workers, who have stopped studying throughout their lives or who have not even started studying.

Despite dropping out of school, EJA students are people who have stories of knowledge, interpretation, values, struggle, resistance, and survival. The students who attend this program are mostly young and working adults, poor, black, underemployed, oppressed, and excluded. The term ‘excluded’ even has a greater dimension when referring to homeless people. According to Frangella (2009), homeless people are part of a specific social segment in the urban space. They are people who have a routine and relationships that are different from the social order, representing extreme social and economic marginalization.

These subjects have their lives marked by stories of inequality of opportunity. Deprived of any social recognition and victims of exclusion caused by poverty, they live in a situation of isolation, rejection, and invisibility, and their condition is usually associated with criminality and uselessness for social development. “It is only up to these invisible ones to remain invisible and not disturb the current social system” (Sousa, 2012, p. 53).

These people live the social phenomenon of naturalization of poverty. Leite (2002) warns that naturalizing is to see something as unquestionable, composing the natural order over which we have no control. In this sense, society attributes to these individuals the lack of personal effort as the cause for the condition in which they find themselves, which ends up contradicting the understanding of poverty as a violation of human rights. When poverty is naturalized, it disappears to our eyes. Wouldn’t that be a selfish behavior? It is easier to say that they are lost, so that we can hold them accountable for their condition. According to Saramago (1995, p. 131) who, in Blindness says: “I don’t think we did go blind, I think we are blind ... Blind but seeing, Blind people who can see, but do not see.” These individuals are, however, still present, and they disappear only to the extent that the spectator refuses to see them with all their maladies. The fact that they do not believe that they may be able to change their condition prevents them from seeking to restructure their identity, their existence. Thus, it is necessary to understand poverty as a transgression of human rights and as a social responsibility.

This article integrates a broader investigation and methodologically uses qualitative research through the narrative interview. The method shows the voices of twenty students from a special school in the Federal District that assists homeless people. According to their narratives, youth and adult education students develop their capacity for resilience and talk about issues such as their rights, poverty, inequality, and their human condition.

The article is organized as follows: initially, it problematizes the diversity found in EJA and discusses the concept of poverty and social and educational inequalities in the context of homeless individuals. Then, it shows the relationship between the students’ narratives and the data of the homeless individuals in the Federal District (DF) from the last census carried out in the capital. Finally, it discusses the use of narratives as a possibility of resilience through the voices of these individuals.

Youth and Adult Education and Homelessness in DF: challenging poverty and educational inequalities

The education of young people and adults in the Federal District is plural, characterized by a diversity of subjects in different times and spaces, with a history of social inequality, discrimination, and disrespect for differences. Given this diversity, the curriculum of youth and adult education of the State Department of Education of the Federal District (2014) points out the need to understand the students, to know their background, their story, and their future projects, since the decision to return to school is not easy to make, much less to stick to it.

The plurality of EJA extends to the homeless population, a phenomenon that raises many questions. According to Silva (2006), there is a recognition of multiple factors that generate this condition of life. Some enter this situation because of structural factors (lack of housing, lack of work and income, economic and institutional changes with a strong impact, etc.); others, motivated by their background (broken family ties, mental illness, alcohol and drug abuse, escape from the country of origin, personal misfortunes, etc.), in addition to natural disasters such as earthquakes and flooding, among others. What is certain is that this condition is not explained by a single determinant.

Given the diversity of motivations that can lead to homelessness, the National Policy for Social Inclusion of the Homeless Population (2008) attributes the following concept to these individuals:

Heterogeneous population group, characterized by its condition of extreme poverty, by the interruption or fragility of family ties, and by the lack of regular conventional housing. They are compelled to live in public places (streets, squares, cemeteries, etc.), degraded areas (sheds and abandoned buildings, ruins, etc.) and occasionally use shelters and hostels to stay overnight (Brasil, 2008, p. 8).

Homeless people feel poverty conditions more intensely than those who live in some type of housing. On the street, these subjects experience extreme poverty, and sometimes all they have is their body. It is a group of society devoid of fundamental, social rights, showing an undeniable violation of human dignity.

According to Quijano (2005), throughout history, these groups have been marked by the violent expropriation of their lands, territories, cultures, memories, origins, identities, languages, their vision of the world and of themselves. Even today these people are still kept outside the intellectual, cultural, and ethical production of humanity. Arroyo (2014) reinforces that, when these subjects are left at the margin, they become responsible for changing their condition of inequality. Individuals who manage to reverse this situation tend to move away from their collectives, which weakens the struggle and resistance of those who remain in that condition. The capitalist model creates a cruel situation: the victory of each of these subjects against poverty and marginalization becomes the weakening of the collective to which they belonged. When they leave and overcome poverty with success and effort, t hey become part of the other group, that of non-poverty. Some end up leaving behind their identity, their origins and their struggle. With the growth in the number of people on the margins, however, the gap between the margin of individual and educational success and that of marginality has become even greater. What do these margins represent? Escorel (1999, p. 44) points out that

The notion of marginality was subjected, over more than forty years, to an intense work of conceptual and methodological purification. However, as it is used by different approaches and with different concepts, it has assumed an extremely generic definition in the ‘sociology of urban marginality’ (Wacquant, 1996), which studies different aspects of different marginalized social groups. Fassin (1996) considers that marginality is not a concept, but an autochthonous notion that names Latin American urban poverty.

The notion of marginality belongs to the framework of social representations of poverty that came up in the 1960s. In the mid-1980s, with the decrease in jobs due to capitalist restructuring, there was an increase in inequalities and a change in the poverty profile. According to Escorel (1999), this fact began when, in 1976, the process of pauperization in France, which was previously restricted to groups of immigrants and residents of the periphery, also extended to those who were on the margins of the capitalist system, who enjoyed the benefits of economic development and social protection. Faced with this phenomenon, a new term to define the new poverty, oppression, and exploitation emerged in France. The term “excluded” (les exclus), created in this context, ended up being impossible to be conceptualized since exclusion represents and encompasses the multiplicity of ways in which social inequalities are manifested.

The concepts of inequality, poverty, and exclusion are discussed by Nascimento (1994). According to the author, common sense in Brazil confuses these concepts. When analyzing inequality and poverty, the author states that social inequality refers to the differentiated distribution of wealth produced or appropriated by a given society, among its participants. Poverty, in turn, represents a situation in which part of the members of a given society does not have enough resources to live with dignity, or does not have the minimum structure to meet their basic needs.

From the point of view of society, the concept of social exclusion is closer and in opposition to that of social cohesion or is a sign of rupture of social ties. In other words, social exclusion itself does not exist. What happens is that there are people who are victims of social, political, and economic processes that exclude capitalist logic. Exclusion, in fact, is a term that refers to control and social cohesion. It is stronger than being “on the margins”, as it intends to separate the collectives in a more radical way. The margins, which could be approached, give way to walls and great insurmountable walls. Unlike the margins and borders that are passable, the walls and great walls of exclusion prevent passage (Nascimento, 1994; Martins, 1997; Arroyo, 2017).

Escorel (1999) also mentions the relevance of looking at social exclusion from the perspective of primary sociability. According to the author, the family plays a central role in defining the place of individuals in society, and family disengagement removes social protection from individuals and becomes the main factor in the process of social exclusion. Regardless of the emphasis given to one or another dimension of social exclusion, the result from the point of view of the excluded individual is: loneliness, isolation and stigma.

As these individuals are set aside, do not belong to social groups, and do not participate in the social dimensions of human life, their condition of exclusion is defined as “[...] fragile and ephemeral and it does not constitute a social unit of belonging” (Escorel, 1999, p. 18).

That said, the economic vulnerability of poor families can lead their members to the threshold between poverty and misery. The lack of work leads to social exclusion. In the case of men who are the head of the household, unemployment can mean the loss of authority over the family and make them abandon or escape from their home and trigger alcoholism. This fact corroborates research that reveals that the majority of the homeless population in Brazil is made up of lonely men of working age, who are homeless, moving from one place to another, performing their daily activities and searching for survival (Escorel, 1999).

In the school context, there is a permanent debate about the relationship between poverty and education: while some expect that education can solve the problem of social inequality, others consider it a place of reproduction of this inequality, especially when we see that there is a more favorable space to socially and culturally privileged students. This point is reinforced by Dubet (2001, p. 13) when he states:

For a long time, we thought that equal supply could lead to equality. Today we realize that not only supply is not really equal, but that its equality can also produce non-egalitarian effects in addition to the effects it wants to reduce.

Therefore, when discussing education for people living in poverty, it is necessary to think of a critical and awareness-raising education that goes beyond the educational offer as a possibility of breaking with poverty.

The system does not fear the poor who are hungry. It fears the poor who know how to think. What mostly favors neoliberalism is not the material misery of the masses, but their ignorance. This ignorance leads them to expect a solution from the system itself, consolidating their status as a mass of maneuver. The main function of education with a political reconstructive content is to undo the condition of the mass maneuver, as Paulo Freire desired (Demo, 2001, p. 320).

Thus, it is of fundamental importance that teachers and students understand social exclusion to develop in the school space a critical discussion of the condition of poverty, in order to demand from the State greater attention to human dignity, to unveil rights still denied and to search for possibilities of overcoming them through an awareness-raising dialogue with the students.

Thus, I emphasize the importance of thinking about Paulo Freire’s ideas, especially the processes of humanization in education. This implies thinking about a dialogue with life stories that are fair and ethical, recognizing that we become human in the diversity of social processes beyond school. We are historical subjects, with stories of dehumanization that can be transformed in the relationships that are constituted, that can seek changes, that can be the change, that cannot be accommodated, that can free themselves, that can become aware in the relationship with another person and with the environment.

Homeless People and Education: their footprints in the capital

In the Federal District, the discussion on the homeless people was fostered through two national meetings in Brasília, one in 2005 and the other in 2009. It should be noted that the Federal District was the first entity of the Federation, in addition to the municipalities, to adhere to the National Policy for Homeless People. By means of Decree No. 33,779, of 2012, the Comitê Intersetorial de Acompanhamento e Monitoramento da Política para Inclusão da População em Situação de Rua (Inter-sectoral Committee for Follow-up and Monitoring of the Policy for the Inclusion of Homeless People was created within the Federal District).

In addition, two surveys were carried out with homeless people in the Federal District. The first was conducted nationwide, including the Federal District, in the period from August 2007 to March 2008. The second was published by Gatti and Pereira (2011), with the project called Renovando a Cidadania (Renewing Citizenship), developed by the Programa Providência de Elevação da Renda Familiar (Program for Family Income Increase). Conducted by researchers from the University of Brasília, this research allowed us to conduct a census of the homeless population in the Federal District.

This article discusses data produced in research that encompasses a broader study, carried out in the 2018-2019 period, at Escola Meninos e Meninas do Parque (EMMP), which assists homeless people. In this study, qualitative research was conducted with a narrative interview with twenty students. The interviews were explored, and the voices of the students could match the census data regarding the street population of the DF, which was carried out in 2010.

In the Census conducted in 2010, 2,512 people were identified: 319 children, 221 teenagers and 1,972 adults. Of the adults, the survey was carried out with 1,206 individuals, which represented 61.2% of this population.

The Census revealed that: 78.1% of the participants are male and 21.9% are female; in relation to skin color, 40.2% were identified as black, 39.9% were identified as brown, and 18.8% as white. The data reveal that most are men, black and brown, who were unemployed and ended up on the streets while looking for a job. The number of women was lower, since they searched for safer or busier places, such as shelters and hospitals, due to the violence and discrimination to which they were exposed on the streets.

Maria1, a student at EMMP school, who participated in the 2018-2019 study, confirms this fact when she states:

I think it’s bad for women to live on the street because, no matter how serious she is, she is disrespected, you know? As in my case... I sleep at the HRAN hospital2. In the waiting room. It’s bad, everyone’s watching. I go to sleep around midnight, when the benches are empty. They keep staring at me... it’s not good. It’s also not good to see women living on the streets. Only men!! Women are discriminated. At the hospital there was a woman who before meeting me, used to say: “I have already told you that I don’t want anyone in here. These beggars come here to piss off, they use the excuse to sleep to steal other people’s things. I would just listen and act like I didn’t care. Then, one day, I told the guard that I was studying. Then this creature was there writing on the counter. She raised her head and asked: “Does she study?” His opened his eyes wide. When he said that I studied, she changed completely. Because she thought that, as I was living on the streets, I was doing drugs and stuff... because she judged people without knowing them.

Maria’s narrative shows the complexity of the issue involving homeless women. Dell’aglio et al. (2018) point out that there is an articulation of the different ways of being in this condition, and there is no way of being a woman and always be connected with other social markers, such as race, social class, sexuality, among others. In this context, intersectionality is present in the multiple discrimination and inequalities that can occur:

[...] the association of multiple subordination systems has been described in several ways: compound discrimination, multiple burdens, or double or triple discrimination. Intersectionality is a conceptualization of the problem that seeks to capture the structural and dynamic consequences of the interaction between two or more axes of subordination. It specifically addresses the way in which racism, patriarchalism, class oppression, and other discriminatory systems create basic inequalities that structure the relative positions of women, races, ethnicities, classes, and others (Crenshaw, 2002, p. 177).

Intersectionality is evident because the other forms of violence that permeate the homeless population constantly end up hiding gender violence. Violence, however, exists and, many times, is the cause that leads women to live on the streets. They run away from their husbands or a family member who attacks them, they run away from abandonment, or they leave home because the family does not accept their gender identity or sexual orientation. Maria’s speech and the research data show the violence to which they are exposed, which lead them to a constant search for places where they can protect themselves. This fact shows the State’s omission, which is a type of violence against rights that are not guaranteed before and during the street situation.

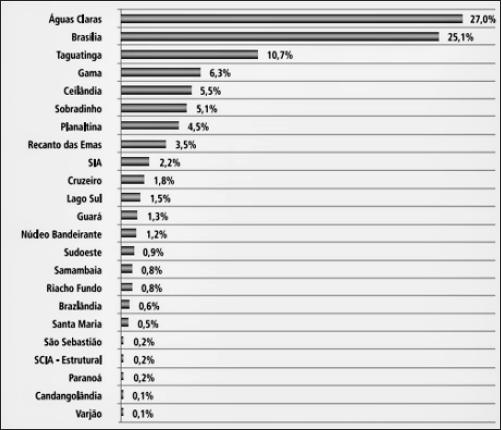

The Census also shows the distribution of homeless adults in the administrative regions (AR)3 of the Federal District. Graph 1 shows a greater concentration of homeless people in the AR of Águas Claras and Brasília4, which reveals a high frequency of these individuals in places with higher concentration of income, in search of better job opportunities.

Source: Renovando a Cidadania Project, 2011 – Federal District Homeless Population Census.

Graph 1 Distribution of homeless adults in the ARs, according to data from the Federal District Homeless Population Census (2010)

The research also reveals that, in that period, people living on the streets had informal jobs. This fact reinforces the importance of breaking with the stigma that these subjects are lazy, wanderers and delinquents. According to the data, only 10.6% lived on money given on the streets, and the rest were car keepers, collected recyclable material and worked in civil construction. The opportunities in civil construction reinforce the fact that the highest percentage is present in the AR of Águas Claras, which in the Census period had many buildings under construction. In addition, the existence of the Shelter Unit for Individuals and Families (Unidade de Acolhimento para Indivíduo e Famílias, UNAF), former Albergue Conviver, located in the AR of Águas Claras, contributed to that percentage.

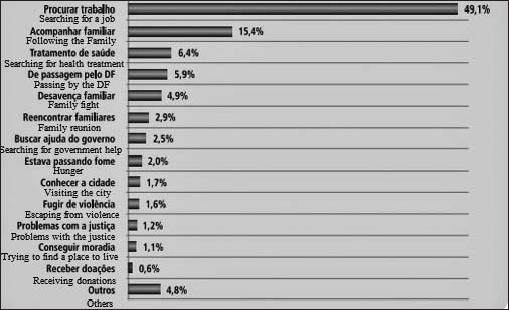

Graph 2 shows the main reasons that brought these adults to the Federal District. It reveals that 49.1% were looking for a job; 15.4% were following their family; 6.4% were searching for health treatment; 5.9% were in a transitory condition, just passing by, while 4.9% claimed family disagreements. The data indicate the search for a job as the main reason, which shows that work is a fundamental condition of human sociability. It is possible to identify interrupted work trajectories of individuals who have become superfluous and unnecessary to the productive system and taken to the street situation. According to Escorel (1999), the phenomenon of social exclusion transforms temporary unemployment into permanent and even creates categories of homeless people: homeless people with a contemporary profile (unemployed) and a traditional profile (beggar, alcoholic and mentally ill).

Source: Renovando a Cidadania Project, 2011 – Federal District Homeless Population Census5.

Graph 2 Reasons that led adults to live in the Federal District, according to data from the Census of Homeless People in the Federal District (2010)

As for place of birth, only 18.9% were from the Federal District. Most of the adults surveyed came from other units of the federation (80.5%) and 0.6% came from other countries. The analysis of Graph 2 shows that 49.1% came in search of work and only 0.6% were aimed at receiving donations. The search for a better life marks the migration to Brasília since the beginning, a city built and constituted by the migrants. The term “candangos” was created at that time and was used to designate these workers. Later, it was also used to name the first inhabitants of the city. The word, however, did not always have this meaning. The Aurélio dictionary says that the word came from kungundu, diminutive of kingundu, in Quimbundo, a language from Angola. For Africans, kungundu expressed the idea of bad, ordinary, villain. Thus, at first, its use was derogatory. Nowadays, the word candango makes up the city. Other derogatory nouns, however, arise for those who did not find a better life, according to the report of the student who participated in the current research:

Marcelo: I came here to be a candango like you. But I became a beggar.

When called beggars, homeless people consider that society places them in the most degrading situation on the streets. Beggars are people who are in a situation where they are no longer able to perform their work. After talking about this condition, another student argues:

Joaquim: No one here is a beggar! We take a shower, work to get some money and study. I am not homeless. I’m living on the streets now. It is different! And I can get off the streets whenever I want. [...] Nobody needs some changes. We need work, education, health and safety.

Regarding age, 60% of respondents are between 22 and 40 years old, reinforcing the challenge of including work as a fundamental dimension of the qualification of these individuals and the need for educational policies integrated to work. There is also a total of 6.80% of homeless people over 50 years old. They are subjects who start the aging process on the streets and begin to lose their work capacity and hope. This fact is perceived in the student’s narrative of this research:

Oswaldo: That was the time when I got sick and had a cancer in my spine. I spent all the money I had and ended up on the streets. After I ended up on the streets, the situation became more difficult. I don’t have a house. After this surgery, I could no longer work as I used to. If I was healthy, I wouldn’t be on the street. I was working. [...] I had already fulfilled my dreams... which was to walk with lots of gold necklaces, to have a car, that’s what mining gave me. It has come and gone. Now I don’t have it anymore. I’m old now... After we are fifty, we have to dream only about death.

Observing the data, it is possible to identify in these subjects the profile of young students and working adults who, at some point in their lives, interrupted their school career. In addition, they reinforce a paralyzed work journey of individuals who have become superfluous and unnecessary to the productive system, which led them to the condition of homelessness.

In this sense, Vieira, Bezzera and Rosa (2004) emphasize unemployment and the cycles of the capitalist system as generators of this condition.

The homeless population is the cruelest portrait of social misery, which is deepening with the growth of unemployment rates and the lowering of wages, as a consequence of the increasingly strong recession process that is happening in the Brazilian economy. [...] Living on the street is a visible reflection of the worsening of the social issue in big cities. On the streets, we see people who survive working on the streets, as is the case of those who collect paper for recycling, car washers and car keepers; we see unemployed people who look for casual work, whose income does not allow them to pay for housing, and those who live off begging and misdemeanor (Vieira; Bezerra; Rosa, 2004, p. 159).

The Census analyzed here completes a decade, reinforcing the absence of official data on homeless people, which makes it difficult to develop public policies aimed at this population. In 2019, the Single Registry for Social Programs of the Federal Government (Cadastro Único6) had registered a total of 3,004 homeless families in the Federal District. It should be noted that this total represents only the people or families who accessed this service. Despite not being a census data, this information points to a 52.3% increase in homeless adults in the DF when compared with data from the 2011 Census carried out in the Federal District.

The fact that the demographic census is carried out at people’s house makes it difficult to obtain current quantitative data on homeless people. In addition, another factor to be considered is the high circulation of these subjects, deprived of the right to the city, since there is even a denial of the space they occupy.

Given this, there are still questions and concerns about who these subjects are. Who are the invisible people that haven’t been considered for a decade? What are their footprints? The bare feet that try to leave footprints in the capital are also made up of students who, after a decade, show that the silence of data can be broken through their voices, which echo in the education of young people and adults.

Resilience: sensitive listening and resilience of homeless EJA students in DF

According to the educational policy of the Federal District, in the curriculum of youth and adult education of the State Department of Education of the Federal District [SEEDF] (2014), all subjects have the right to learn. In this sense, the EJA program must be concerned with the acquisition of new knowledge and with sharing experiences that enable continuous learning for subjects in different learning conditions. The diversity of individuals that attend EJA classes includes people who live on the streets, on the edge of survival and who face the challenge of being heard, since they are socially silenced and made invisible.

The offer of EJA for these subjects in the DF takes place at Escola Meninos e Meninas do Parque (EMMP), which presented, in the School Census of the 1st semester of 2019, a total of 159 students enrolled, of which 140 (88%) were male and 19 (12%) were female. Regarding the age group, 11 (7%) were between 15 and 21 years old, 40 were (25%) between 22 and 29 years old and 108 (68%) were over 30 years old. According to the data, 77 (48%) were in the 1st segment7 and 82 (52%) in the 2nd segment of the EJA program. These students have a story of life on the streets and mostly do not rely on family support, having the school as the only reference.

The education of young people and adults is a possibility for these subjects who are part of historically marginalized social groups. Therefore, EJA plays an important role in presenting to students the knowledge of their story of survival and work on the streets, in addition to the possibility of learning. The stories of struggle, resistance, and emancipation of these subjects must be part of the school course.

According to Arroyo (2017), EJA is the locus of these subjects with collective identities of segregation, oppression and abandonment. But, above all, of people who resist and fight for a change. The first step in this struggle is to return to school, to education. In the school context, the dialogue between students and educators enables transformations, strengthens the capacity for resilience from the exchange of knowledge, experiences, life experience and survival of students.

Given the above, this article proposes to think about the concept of resilience, to understand EJA students living on the streets through narratives. The subjects who live on the street can play a key role and present narratives that constitute their realities, their imagination and their dreams.

It is necessary to break with the social negligence that leaves homeless people in a condition of worthless subjects. These departures neutralize the resumption of a condition of resilience. Madariaga et al. (2014, p. 14) point out the importance of human resilience, because “[...] resilience implies, on the one hand, a confrontation, as well as what is most important, also a transformation, an apprenticeship, a growth, that goes beyond mere resistance to the difficulties”. Human resilience goes beyond the original meaning of resilience, which in physics is related to the property that some bodies have of returning to their original shape after being subjected to elastic deformation. When establishing a dialogue between the realities of homeless people with the two concepts, it is possible to see that the body does not only bring memories, but marks of moments of struggle, resistance and survival on the streets. Thus, students bring the narrative that reveals the space that the school represents in their reality:

Nilson: People are so mistreated, offended and humiliated that they don’t believe in anyone else. [...] Now here at school I’m changing. Here I am well received. [...]Here I listen to a friendly word. Then I feel better, and I also become a better person.

The voice of the student reveals the school as a fundamental space for growth, transformation and intellectual, emotional and social development of students. The school unit is constituted as a space for resilient subjects from the moment the team of educators understands that:

The pedagogical space is a text to be constantly ‘read’, interpreted, ‘written’ and ‘rewritten’. In this sense, the more solidarity there is between the educator and the students in dealing with this space, the more possibilities are open for democratic learning in the school (Freire, 1996, p. 109).

According to Maturana and Dávila (2009, p. 236), there must be a concern with the other, that is, it is necessary to look and listen, because “[...] talking becomes a dynamic dance between the game of listening-feeling-reflecting-being 100% there”. When this happens, collaborative relationships and mutual respect emerge. And in this direction, when you are welcomed by the others, people can listen to you, you have a voice, and the narrative arises. You lose the fear of being exposed. Thus, stories are individually and collectively constituted in a process of human resilience, in which individuals overcome adversity and transform difficult moments into opportunities to learn, grow and change.

Faced with the reality of exclusion in which these individuals are immersed, resilience is not just made up of stories of success. Individual representations and memories evoked by each moment are linked to the facts that occurred.

For Cyrulnik (2001, p. 225), resilience refers to a set of:

[...] harmonized phenomena in which the subject penetrates within an affective, social and cultural context. Resilience is the art of navigating the torrents. A trauma pushed the victim to a direction where he/she would like not to have gone, but since he/she fell into a wave that sweeps him/her and takes him/her to a cascade of mortifications, the resilient person has to appeal to the inner resources impregnated in his/her memory, he/she has to fight to not let himself/herself be dragged along by the natural slope of the traumas that make/her him tired of fighting, from aggression to aggression, until an outstretched hand offers him/her an external resource, a social or cultural institution that allows him/her to get out of the situation.

In the case of the participants of the research, Escola Meninos e Meninas do Parque is an institution that participates in this process of resilience through the education of young people and adults. For Benetti (2014), the school can be a space that promotes resilience when it triggers strategies that provide support, inclusion, sense of belonging, feelings of value and participation, as per the following statements:

Joaquim: Here at school, we have a bonding, we help each other. Rogério: I had difficult moments. Now I have this school that makes me grow.

Maria: I was left at Febem when I was a child. I stayed there until I turned 18. I was never prepared for the future. The memory I have from there are the bars. It was the world I knew. At the age of 18 I was put out of Febem. I received a tap on my shoulder saying that my freedom had arrived. That was the concept of freedom that I was told. Then I lived on the streets of São Paulo. Tired of the streets of São Paulo, I came to Brasília. I’ve had two marriages, but neither has worked out. My first husband was involved with drugs and the second, with alcohol abuse. With so many things going on, I could have given up, right? But, I won’t give up. A lot of people asked me when I went back to school: “Why are you going to study? You couldn’t do that when you were young. Just give up”. I would say: “Okay, never mind!” There was one who asked me: “What do you want to study for? To go down to the grave?” I said: “Yes, I will go to the grave with wisdom”. The other asked: “What’s the purpose of studying Spanish? This is illusion! Don’t you have a job? Won’t you go outside?” Do you think I am influenced by others? I’m not, I’ll continue! And it all started here, this school was like a mother to me.

The students’ reports show that, more than resilience, it is necessary to have hope. The type of hope explained by Freire (2014, p. 110) does not emphasize a mere wait:

It is necessary to have hope, one cannot only wait. And hoping is not synonym of waiting. Hoping is getting up, going after what you want, it is constructing and not giving up! Hoping is carrying on, hoping is to join the others and do something different.

When Freire (2014) says that hoping is not giving up, this matches Maria’s discourse: “Do you think I am influenced by others? I’m not, I’ll continue!” Not giving up, continuing, is keeping hope. Hope is a fundamental element to recover utopia. The utopia that, according to Freire, defines a way of being-in-the-world, which makes it possible to launch oneself, to seek, since we are unfinished and incomplete beings. Hope makes people capable of moving forward to unfold their story.

Therefore, the education of young people and adults can help in the recovery and increase of the self-esteem of these people, which will be able to reflect in their narratives about their identity, cultural background and problems, in order to re-signify their stories.

Ricoeur (1997) reminds us that life is lived and stories are told. The experience that can be offered to these EJA students living on the streets, of transforming into narratives what they have lived, will allow them to see themselves as characters of their own story. At this moment, those who were visible, but socially invisible, become narrators, characters, and protagonists of their own story and, despite being the subjects themselves, they are no longer the same person when they tell their story.

The story is not a return to the past, it is a reconciliation with their own story. An image is created, events are given coherence, as if we were healing an unfair wound. Making a self-report fills the void of origins that disturbed our identity (Cyrulnik, 2009, p. 12).

The narratives at that moment break the culture of stolen silence that strips off the identity and dignity of these subjects.

It is not in silence that men make themselves, but in words, in work, in action-reflection. [...] We are obviously not referring to the silence of deep meditations in which men apparently leave the world, ‘move away’ to ‘admire’ it in its entirety, and continue with it. Hence, these forms of recollection are only true when men are immersing in reality and not when they try to escape it, in a kind of ‘historical schizophrenia’, undervaluing the world (Freire, 1975, p. 92).

The word and silence are part of and constitute a democracy from the moment you have the option to choose one or the other. However, when society chooses not to listen to homeless people, and silence becomes an imposition, these subjects are silenced. Communication is a condition of recognition of the other. Sometimes, the lack of coexistence affects the exchange of experiences and the lack of life stories. People living on the streets would represent the void of individual experience. They are the wanderers, the dirty, the filthy ones, among many other adjectives that express the image of abjection. However, in addition to this image, Frangella (2009) shows that these subjects can also illustrate the example of redemption and social morality, since they are the ones who have had the extreme experiences of pain, isolation and suffering. Therefore, they would be carriers of wisdom about pain, about life and about the truthfulness of values and feelings. Thus, they become storytellers of stories never seen before, witnesses of crimes, of illicit situations and strange adventures in urban spaces. In this universe of stories, the narrative of the Student emerges.

Joaquim: I’ve traveled all over Brazil, I’ve been on the streets since I was 13 years old. On one of these trips, I went to the South region. There, I got a job on an apple orchard. They asked for the documents to pay for the job. Then the young man told me to talk the person in charge of the orchard. I became worried... When I arrived there, he asked my father’s name. I answered. He asked what my dad did for living. I told him he was a truck driver. Then he asked: “How did your mother meet your father?” I said that he was passing by Rio Grande do Norte and met my mother. Then he told me... “I’m your uncle!! Your father was my brother.” There I met my father’s family.

Finally, the narratives of these subjects can help us understand the individual and collective specificity of surviving and learning of people living on the streets. Because of its complexity, the context of homeless students of the young people and adults program presents itself as a fertile field for the study of the manifestations and narratives of the resilience construct. It is, therefore, relevant to understand and get to know these stories, in order to contribute to a more effective teaching and learning process for these subjects.

Final remarks

This work shows us the importance of thinking about expanding research and policies for homeless people in youth and adult education. Educational policies cannot ignore this reality, and EJA is the modality that includes the largest number of subjects who find themselves in this situation.

This study also encourages us to think about poverty in teacher training and in educational spaces. Poverty is a collective situation; however, in education, teachers are still not qualified to deal with situations of poverty and inequality. In teacher training and school spaces, it is necessary to broaden the discussions on this condition, in order to improve the service and understand the diversity of subjects within the EJA program.

Upon returning to the EJA program, people want to have in this space the possibility of being agents of their own history and of being able to recognize themselves as capable of learning, despite the limitations attributed to themselves, having their personal and collective narratives recognized and valued as part of the educational process.

The EJA program can be a space for types of pedagogy that affirm and dialogue with the realities of its students, so that they are not only beneficiaries, but participants in the process. Therefore, this work is not aimed at finding, through the narratives, a solution for the reality of students in the education of young people and adults in street situations but it is aimed at showing many concerns that may lead to taking actions to give new meaning to these subjects and their stories.

Notes

1The names of the interviewees were replaced by pseudonyms, in order to preserve them from possible embarrassment.

3The Federal District has a different territorial division from the rest of the country. Instead of municipalities, the DF is divided into administrative regions (AR). The basic difference is that the municipality has political, administrative and financial autonomy, while the ARs are linked to the Government of the Federal District.

4This AR has a high concentration of income due to the fact that directors of direct and indirect government administration bodies, qualified public employees, self-employed professionals, and merchants who earn higher incomes live in these locations.

5As t his image was ta ken f rom a n inst itutiona l docu ment a nd ca nnot be ed ited, the table includes the text in Portuguese and English.

6Cadastro Único is an important tool for the Federal Government’s social programs. It is an instrument that aims to socially include low-income Brazilian families. Its basic unit of reference is the family, but it also accepts single-person families.

7Youth and Adult Education in the Federal District is organized by segments and stages. Each segment corresponds to a stage in the Basic Education. The 1st segment corresponds to the initial years of elementary school and the 2nd segment corresponds to the final years of elementary school.

REFERENCES

ARROYO, Miguel González. Outros Sujeitos, Outras Pedagogias. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2014. [ Links ]

ARROYO, Miguel González. Passageiros da Noite do Trabalho para a EJA-Itinerários pelo Direito a uma Vida Justa. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2017. [ Links ]

BENETTI, Idonezia Collodel; GRISARD, Edla; FIGUEIREDO, Odair. Redes de Apoio: Estado, família e escola como contextos promotores de desenvolvimento. Roteiro, v. 39, n. 1, p. 240-260, 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Política Nacional para Inclusão Social da População em Situação de Rua. Brasília. 2008. Disponível em: <http://www.mpsp.mp.br/portal/page/portal/cao_civel/acoes_afirmativas/inclusaooutros/aa_diversos/Pol.Nacional-Morad.Rua.pdf>. Acesso em: 17 out. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto n. 33.779, de 6 de julho de 2012. Institui a Política para Inclusão Social da População em Situação de Rua do Distrito Federal e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 2012. Disponível em: <http://www.tc.df.gov.br/sinj/Norma/72258/Decreto_33779_06_07_2012.html>. Acesso em: 17 out. 2020. [ Links ]

CRENSHAW, Kimberlé. Documento para o encontro de especialistas em aspectos da discriminação racial relativos ao gênero. Revista Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 10, n. 1, p. 171, jan. 2002. ISSN 1806-9584. Disponível em: <https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/ref/article/view/S0104-026X2002000100011/8774>. Acesso em: 29 maio 2020. [ Links ]

CYRULNIK, Boris. Resiliência: essa inaudita capacidade de construção humana. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 2001. [ Links ]

CYRULNIK, Boris. Autobiografia de um Espantalho: histórias de resiliência – o retorno à vida. Tradução Claudia Berliner. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2009. [ Links ]

DELL’AGLIO, Daniela Dalbosco; RICHTER, Cecília Loureiro; MACEDO, Fernando dos Santos de; FERREIRA, Aurea Ferreira de; SILVA, Alessandra Alves da; SILVA, Valquíria Martins da. Mulheres em situação de rua e os paradoxos: quando a política pública mais “efetiva” de saúde e moradia é o encarceramento. In: NARDI, Henrique Caetano; ROSA, Marcus Vinícius de Freitas; MACHADO, Paula Sandrine; SILVEIRA, Raquel da Silva (Org.). Políticas Públicas, Relações de Gênero, Diversidade Sexual e Raça na Perspectiva Interseccional. 1 ed. Porto Alegre: Editora Secco, 2018. P. 73-80. [ Links ]

DEMO, Pedro. Conhecimento e Aprendizagem: atualidade de Paulo Freire. In: TORRES, Carlos (Org.) Paulo Freire e a Agenda da Educação Latino-Americana no Sec. XXI. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2001. [ Links ]

DISTRITO FEDERAL. Secretaria de Estado de Educação do Distrito Federal. Currículo em Movimento da Educação Básica. Educação de Jovens e Adultos. Caderno 6. Brasília: SEEDF, 2014. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. As Desigualdades Multiplicadas. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 17, p. 5-19, 2001. Disponível em: <https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/n17/n17a01>. Acesso em: 16 out. 2020. [ Links ]

ESCOREL, Sarah. Vidas ao Léu. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz, 1999. [ Links ]

FRANGELLA, Simone Miziara. Corpos Urbanos Errantes: uma etnografia da corporalidade de moradores de rua em São Paulo. São Paulo: Fapesp, 2009. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do Oprimido. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1975. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Esperança: um reencontro com a pedagogia do oprimido. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2014. [ Links ]

GATTI, Bruna Papaiz; PEREIRA, Camila Potyara (Org.). Projeto Renovando a Cidadania: pesquisa sobre a população em situação de rua do Distrito Federal. Brasília: Gráfica Executiva, 2011. [ Links ]

LEITE, Izildo Corrêa. Desconhecimento, Piedade e Distância: representações da miséria e dos miseráveis em segmentos sociais não atingidos pela pobreza. 2002. Tese (Doutorado em Sociologia) – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras (Campus de Araraquara). Universidade Estadual Paulista – ‘Júlio de Mesquita Filho’, Araraquara, 2002. [ Links ]

MADARIAGA, José Maria et al. La Construcción Social de la Resiliência. In: MA-DARIAGA, Jose Maria. Nuevas Miradas sobre la Resiliência: ampliando âmbitos e prácticas. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2014. P. 11-30. [ Links ]

MARTINS, José de Souza. Exclusão Social e a Nova Desigualdade. São Paulo: Paulus, 1997. [ Links ]

MATURANA, Humberto; DÁVILA, Ximena Yanes. Habitar Humano em Seis Ensaios de Biologia Cultural. São Paulo: Palas Athena, 2009. [ Links ]

NASCIMENTO, Elimar Pinheiro. A Exclusão Social na França e no Brasil: situações (aparentemente) invertidas, resultados (quase) similares. In: DINIZ, E. (Org.). O Brasil no Rastro da Crise. São Paulo: ANPOCS/IPEA/Hucitec, 1994. P. 289 - 303. [ Links ]

QUIJANO, Anibal. Colonialidade do Poder, Eurocentrismoe América Latina. In: LANDER, Edgardo (Org.). A Colonialidade do Saber: etnocentrismo e ciências sociais – Perspectivas Latinoamericanas. Buenos Aires: Clacso, 2005. P. 107-126. [ Links ]

RICOEUR, Paul. Tempo e Narrativa. (Tomo 3). Campinas, SP: Papirus, 1997. [ Links ]

SARAMAGO, José. Ensaio Sobre a Cegueira. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1995. [ Links ]

SILVA, Maria Lúcia Lopes da. Mudanças Recentes no Mundo do Trabalho e o Fenômeno População em Situação de Rua no Brasil 1995-2005. 2006. 220 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Política Social) – Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2006. [ Links ]

SOUSA, Anne Gabriele Lima. Eu Sou de Rua, mas Também Sou Gente: inter-subjetividade e construção de identidades dos indivíduos em situação de rua de João Pessoa - PB. 2012. 249 f. Tese (Doutorado em Sociologia) – Educação ambiental e Educação do campo, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 2012. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Kleyne Cristina Dornelas de. Nessa rua, nessa rua, têm educandos da EJA com narrativas fotográficas para nos contar. 2019. 163 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2019. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Maria Antonieta da Costa; BEZERRA, Eneida Maria Ramos; ROSA, Cleisa Moreno Maffei. População de Rua: quem é, como vive, como é vista. 3. ed. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2004. [ Links ]

Received: November 03, 2020; Accepted: June 21, 2021

texto em

texto em