Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Realidade

versão impressa ISSN 0100-3143versão On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.47 Porto Alegre 2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236117203vs01

OTHER THEMES

The Philosophy of Education in the Gradiva Step

IUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria/RS – Brasil

The text consists of reflecting on the relationship between philosophy of education and teacher education, inspired by the metaphor of Gradiva’s step, taken from Wilhelm Jensen’s novel Gradiva, a Pompeian fantasy. The focus of the discussion is established from the appropriation made by Freud about this novel, in confrontation with the interpretation of Jacques Derrida. The need to take a step that redimensions its performance in this context is realized, imprisoned, at times, in the files of undergraduate courses’ curricula, to a metaphysical position in the order of knowledge. The article ends up encouraging the review of the archaeological search for knowledge, as it maintains contact with the enchantment of Gradiva’s pass, although it recognizes its fate in archive fever.

Keywords Philosophy of Education; Psychoanalysis; Archive Fever; Teacher Education

O texto consiste em pensar a relação da filosofia da educação com a formação de professores, inspirada na metáfora do passo de Gradiva, extraída do romance Gradiva, uma fantasia pompeiana, de Wilhelm Jensen. O foco da discussão se estabelece a partir da apropriação realizada por Freud deste romance, em confronto com a interpretação de Jacques Derrida. Percebe-se a necessidade de dar um passo que redimensiona a sua atuação neste contexto, aprisionada, por vezes, nos arquivos dos currículos dos cursos de licenciatura, a uma posição metafísica na ordem do saber. O artigo termina por incentivar a revisão da busca arqueológica de saberes, pois, assim, mantém contato com o encanto do passo de Gradiva, embora reconheça a sua sina no mal de arquivo.

Palavras-chave Filosofia da Educação; Psicanálise; Mal de Arquivo; Formação de Professores

Introduction

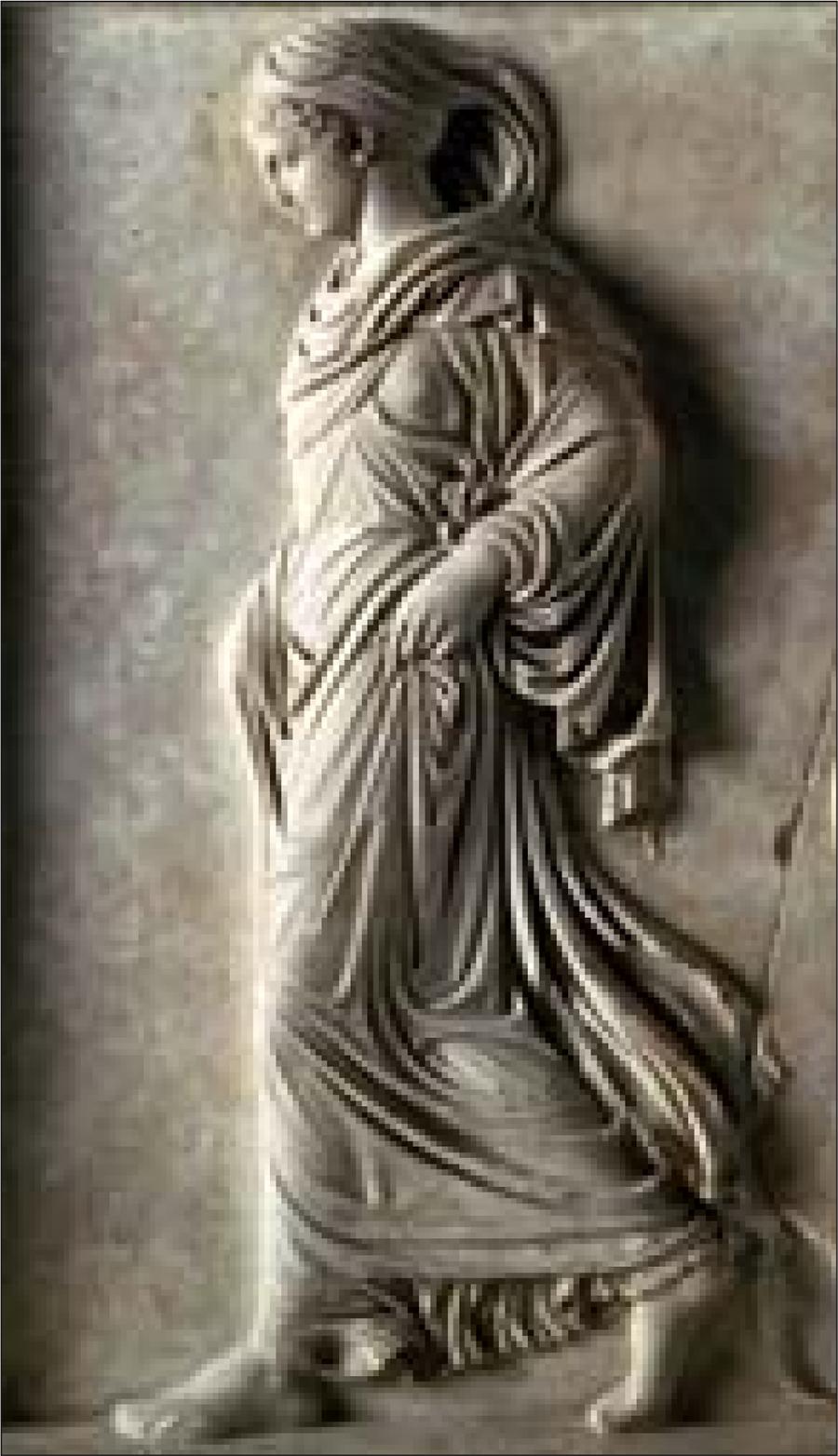

Psychoanalysis emerges in the model of the interpretation of dreams, by Freud (1856 – 1939), willing to decipher their enigmas and disguises. He realized that the unconscious manifests itself in the edges, in the cracks or in the moments when the mind loosens the controls over the conscious, with dreams being one of those privileged moments. Therefore, he begins to analyze the various dreams reported by his patients as a raw material of mental archeology. In the book Delusions and dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva (Freud, 2003), he seeks to advance this experiment, willing to also analyze the similar manifestations that occur in the creation of a novel. It is the book suggested to him by Jung, called Gradiva, a Pompeian fantasy (Jensen, 1993), by German novelist Wilhelm Jensen (1837-1911). The author tells a story that has its starting point as the finding of a piece of marble from the golden age of ancient Greece. According to Freud (2003, p. 101), the bas-relief is in the Vatican’s Chiaramonti Museum (nº 644), having been restored and interpreted by Hauser. Together with other fragments that are in the museum of Florence and Munich, they would give 2 reliefs identifying 3 figures that represent the Hours: the goddesses of fertility and of dew.

The main character of the novel, Norbert Hanold, an archeologist from northern Germany, while making one of his trips to Rome, finds a small piece of marble that leaves him enchanted with the image of the woman represented there and immediately names her Gradiva, which, in the Latin translation, means the one who advances. He obtains a plaster copy and keeps it as a fetish in his office, in a university town in Germany, to periodically contemplate it. In it, the scene of a young woman appears, walking and dressed in a long tunic, in which her feet adorned by sandals are exposed and with one of the steps gracefully in the vertical position. Seduced by the shape of Gradiva’s step illustrated in the bas-relief, Hanold desperately seeks to locate the person who fascinated him, developing dreams and delusions that lead him to the ruins of Pompeii, a city located 22 km from Naples, Italy, which was buried by the Vesuvius volcano in 79 AD.

It is a story that narrates the character’s encounters and disagreements until he reaches the real figure that represents Gradiva, in his imagination, called Zoé Bertgang. There is in the novel a process of description of a repression of amorous libido directed at women and its subsequent cure. Perhaps this aspect drew Freud’s attention due to the similarity with the analytic-therapeutic treatment, as well as the relationship with the “archaeology” of the ruins of Pompeii, a metaphor that permeates the Freudian explanations given to the unconscious by psychoanalysis and that led him several times to Italy. Furthermore, Freud would have seen in this metaphor the growth step of psychoanalysis in relation to the methods and techniques previously adopted in the treatment of patients. We are well aware that such therapeutic methods were extremely invasive, causing a lot of discomfort in the consultations, so little by little he replaced hypnosis and suggestion with free association, as a fundamental rule of psychoanalysis.

The influence of psychoanalytic discourse on the most diverse practices of knowledge is notorious. Always attentive to the displacements created by the discourse of psychoanalysis, the extent of the impact of the case reported in the novel was such that the Surrealists turned Gradiva into their inspiring muse. Salvador Dalí even nicknamed his wife Gala de Gradiva (Brasil, 2020, p. 51) and painted a picture in her honor, as we can see below.

Source: Carvalho (2016).

Figure 1 Gradiva finds the ruins of Anthropomorphos, painting by Salvador Dali

This situation is also made possible to the philosophy of education by several “coincidences”, such as those that occur from the assimilation of the original work, by Jensen (1993), in the interpretations offered by Freud and Derrida. After all, as Mendes (2005, p. 53) well points out: “Psychoanalysis goes beyond the boundaries of the office, focusing and trying to interfere in the most diverse fields of knowledge”. First, it is necessary to agree that the transport of fiction from the literary field to the territory of philosophy and education is not something foreign to its tradition. Many philosophers and educators were also novelists, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Albert Camus or Jean-Paul Sartre. However, the challenge is how to take this step in an interdisciplinary way, bringing together literature, psychoanalysis, philosophy and education?

To better enhance understanding, it is certainly necessary to find a gateway to reflect on such a controversial topic. We see this possibility when Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) analyzes Freud’s appropriation of Jensen’s book through the prism of his quasi-concept of “archive evil”. After noting that Gradiva’s step speaks of itself, he warns that “Hanold suffers from archival evil” (Derrida, 2001, p. 126). In other words, the main character goes through the same dreams, delusions and (mis)encounters of the archival evil of psychoanalysis and other areas of knowledge that need history to understand themselves. Therefore, we believe that his search contains similar tastes and unpleasantness to those faced by philosophy and education even today. After all, it is also challenged in modernity by the dictates of positive science, to obey a technical-methodical rule that is understood as the only form of bond and access to reality, on the one hand, or to fall back into the pure fantasy of spectral delirium, for another.

Now, if philosophy had not historically tried to get out of this dilemma, it would not have been awakened from its “dogmatic slumber”, as Kant (1980) suggests, for example. Such transcendent sleep led it to believe in the “metaphysics of presence”, as Derrida (2004; 2017) criticizes, in the empire of unity inhabited by essences, substances, needs and eternities. But what step can the relationship between philosophy and education take inspired by this book?

Guided by the metaphor of Gradiva’s step, we intend in the article to address some of the current challenges for the philosophy of education in teacher training, also trying to decipher its enigmas as it is inserted in the files of licensure courses. We will initially try to insert the theme from the conflict of the two interpretations of the novel, by Freud and Derrida. The objective is to uncover what Derrida proposes to the Freudian interpretation, by the desire for memory provoked in the archival evil. Finally, as a passage from the dream-delusion to the real, but also as a way of not losing the charm, to find out what step philosophy of education can take in the wake of Gradiva.

Freud and Derrida’s Gradiva

Freud’s (2003) analysis in his book Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva starts from the verification of Hanold’s exclusive dedication to the world of science, in this case archaeology. It focuses on the aspect of how the archaeologist relates to his libido, because at the beginning of the novel “[…] in a somewhat different way from an ordinary human being: he was not interested in living women” (Freud, 2003, p. 50).

Due to this commitment to science, he does not perceive the relationship between Gradiva’s delusion and the real woman, who was actually his neighbor and that is why Freud (2003, p. 45) considers “Gradiva as a psychiatric study”. His first initiative was to turn to practice, looking for similarities with the way women go about their daily lives in their city. He even had a positive impression in one case, but as he couldn’t prove the scene, he eventually gave up. A dream provoked a delirium in him, motivating him to visit Pompeii. In this aspect, there is a proximity between dreams and delusions, as they “[…] arise from the same source – from what is repressed” (Freud, 2003, p. 67). Of course, the trip was in the service of this hallucination, but Hanold still had the feeling that this was going to be a business trip. No doubt the unconscious motive was that in Pompeii he could continue his obsession with finding Gradiva.

The central character of the novel would have suffered, therefore, a process of repression of his emotions when dedicating himself totally to the universe of science, which makes it impossible for him to have a healthy relationship with women. Freud realizes that the exclusive interest in his profession made him see everything through an archaeological prism, that is, he was little interested in life. That’s why it’s difficult for him the acceptance and almost disgust of the German couples who come to spend their wedding next to the ruins of Pompeii. Gradually, however, he distances himself from being imprisoned in the prosaic world of science and begins to establish less idealized relationships with Gradiva. This change of course provokes a new relationship with his profession and, consequently, with the science that is tributary to him, because “In this state of mind, his fury turned even against the science of which he was a faithful servant”, says Freud (2003, p. 70). And, further on, he notes that: “Inhibited the internal understanding (insight) of the reasons for the journey undertaken under the command of delusion, his scientific interests, which should be stimulated by the new environment, were also hampered” (Freud, 2003, p. 74).

Gradiva participates to some extent in Hanold’s delusions, both appearing and disappearing in front of him in a mysterious way, sometimes making allusions to meals she would have had with Hanold two thousand years ago in Pompeii (time of the eruption of Vesuvius that buried her), etc. Freud’s comment is pertinent to understand this strategy adopted by the muse, similar to that of the analyst in psychoanalysis: “Thus, in her words, the young woman, on the one hand, remains faithful to the role given to her by Hanold’s delusions and, on the other hand, it alludes to real circumstances in order to awaken in Hanold’s unconscious an understanding of them” (Freud, 2003, p. 90). This game continues until Gradiva reveals to him that, in fact, she was not the reincarnation of the marble piece, but its childhood neighbor. However, this return is loaded not only with love, as is the case with a passion, but also with revelations, such as the fact that she accuses him of being an “arqueópterix”, a species of flying reptile from the time of the dinosaurs. In translation, we could say that Norbert is a dinosaur seduced by archeology and that, therefore, he only saw Gradiva through the dead piece.

Source: Carvalho (2016).

Figure 2 Gradiva, ‘the girl who advances’, bas-relief from the Chiaramonti Museum, Vatican

His investigation, however, led him back to life, since his delirium went from the dead (the bas-relief) to the quest to revive something dead, but without dialoguing with life. And so, Freud concludes:

The healing process is carried out in a relapse in love, if in the term ‘ove’ we combine all the different components of the sexual instinct; Such a recurrence is indispensable, since the symptoms that provoked the search for a treatment are nothing more than precipitates of previous conflicts related to the repression or the return of the repressed, and they can only be eliminated by a new ascent of the same passions

(Freud, 2003, p. 95).

Freud realized the exclusive subservience with which Hanold dedicated himself to the science of archaeology, which caused him to repress his emotions, a fact that took him to Pompeii to search for the origin of the figure found in the bas-relief. Differently, the Gradiva, which is Derrida’s (2001), is analyzed under the specter of archival evil, a reflection that appears in the Post-Scriptum of his book Archival evil: a freudian impression. At this point, Derrida is concerned with the scope of the archive’s promise, with its openness to constant becoming, since there is a gap to be filled in its historical impression. This allows the file to open up to the future and promise.

Derrida is aware of the crisis of metaphysics, but he perceives the presence of its remnants in Freud’s work. When he had contact with the Freudian work, Derrida (2017) had already published his Gramatology, which led him to perceive the contributions of philosophy through the prism of the trace, in which ghosts inhabit the spaces of writing: “Writing it would basically be spacing, inscribing and arranging traces in a space produced by the very process of differing” (Birman, 2007, p. 291). And this was allowed to him insofar as he seeks to show, from an analysis of his work, that writing is part of the structure of the psyche, as Freud came to compare the unconscious with several metaphors, the most important of which were that of typewriter and magic pad. Therefore, he saw in psychoanalysis the materialization of his philosophy, in which “[…] the narratives would be productions of his ghosts and these would regulate the process of interpretation they undertook” (Birman, 2007, p. 293-294). Spectral logic allows us to go beyond metaphysics, thus breaking the dichotomy that there is an inside and an outside, since the ghost is an entity that is not limited to the intelligible or the sensible. In this sense, he even suggests a revision of logocentrism, since philosophy was consolidated, with Socrates, as a record grounded in phonocentrism, that is, in speech and not in writing, given that Socrates wrote nothing.

According to Derrida (2001), it is necessary to go beyond the Freudian analysis of the novel, since his notion of the archive is still marked by metaphysical remnants, in order to find a first, literal impression, which, in the Kantian view, would be like finding “the thing in itself” of the phenomenon (Kant, 1980). Therefore, “Freud still intends to bring to light a more original origin than that of the spectrum” (Derrida, 2001, p. 125), that is, to transcend the representation of the ghost towards what generated it. And this represents an initiative linked to a broader project by Derrida, to rethink the foundations of psychoanalysis, as he himself comments in an interview given to Elisabeth Roudinesco:

‘The friend of psychoanalysis’, in me, distrusts not positive knowledge, but positivism and the substantiation of metaphysical or metapsychological instances. The great entities (I, it, superego, etc.), but also the great conceptual ‘oppositions’, too solid, and therefore so precarious, that followed those of Freud, such as the real, the imaginary and the symbolic, etc, ‘introjection’ and ‘incorporation’ seem to me to be loaded (and I have tried to demonstrate this more than once) by the ineluctable need for some ‘difference’ that erases or displaces their borders. In any case, deprive them of all rigor. I am therefore never ready to follow Freud and his colleagues in the workings of their great theoretical machines, in their functionalization

(Derrida; Roudinesco, 2004, p. 208-209).

Freud’s quest in this sense would be to go ahead even in relation to the novelist, as well as in relation to the objective science of archeology itself, in short, it is an investigation in search of the archive in its original form, that is: “An archive without an archive, there where, totally indiscernible from the impression of her brand, Gradiva’s step speaks of itself” (Derrida, 2001, p. 126). It is at this point that Hanold becomes disenchanted with his science, as he understands that “[…] he taught a lifeless archaeological intuition” (Derrida, 2001, p. 126).

Hanold was well versed in deciphering enigmas, from the most indecipherable to the most enigmatic, and he travels to Pompeii willing to “[…] rediscover his traces, the traces of the Gradiva step” (Derrida, 2001, p. 126-127). It is at the moment when he finds the piece that he also understands how Pompeii can have life again, through his memory, that a “drive” or “intimate drive” awakens in him. It is a search, underlined by Freud, of the literal, of the primitive impression, the arkhê, in short: “He dreams of reviving” (Derrida, 2001, p. 127) the step that Gradiva would have left in the ashes of Pompeii, as if it were a signature.

However, Derrida (2001, p. 127) argues against the metaphysical quest for uniqueness that “its price is infinite”. Furthermore, it is “incommensurable where it is unfindable” (Derrida, 2001, p. 127). And that all this obsession can only be dreamed a posteriori, so he infers: “The faithful memory of such a singularity can only be handed over to the phantom” (Derrida, 2001, p. 128). There is, therefore, a debt in the archive, a “lack of knowledge”, an archival evil at the origin and this is the secret that literature, emancipated from the Holy Scriptures, wants to reveal: “the inviolable secret of Gradiva”, which is common to the feelings of Hanold, Jensen and Freud, among others, as concludes Derrida (Derrida, 2001, p. 128).

When he reflects on the function of the death drive on the archive, he will also infer that: “It works to destroy the archive: with the condition of erasing, but also with a view to erasing its ‘own’ traces - which can no longer be called ‘own’” (Derrida, 2001, p. 21). The death drive acts at the heart of the archive, leaving room for memorization, repetition, reprinting and, in this sense, it concludes that repetition itself, the logic of repetition and even “[…] the compulsion to repeat is, according to Freud, inseparable from the death drive” (Derrida, 2001, p. 23). It is the death drive (Thanatos) that causes the archival evil, as it destroys its presence, its being, leaving as an inheritance the future, its constant becoming, with several gaps to be filled by those who interpret. Now, while discussing the archives of psychoanalysis in his book, Derrida realizes that “[…] the moment psychoanalysis formalizes the conditions of archival evil and the archive itself, it repeats the same thing it resists or makes of an object” (2001, p. 119). That is, when returning to the origin of the repressed, Freud repeats with his (therapeutic) gesture the same motive that led to the Jewish diaspora (trauma), a desire to return to the origin, to the primitive arkhê, something metaphysical, which would transcend the here and now2.

Thus, the archeologist or historian does not relate to the sources of the past in an untouched way, but from the findings, the remains or the pieces of history, caused by the archival evil. Derrida thus transfers the notion of death drive, typical of psychoanalysis, to understand the notion of archive in order to show that it acts in the field of eros, in what has been constructed and documented throughout history. As Trevisan, Azevedo and Rosa (2021, p. 5) well point out: “The compulsion to repeat is tied to the necrophilic drive and, therefore, to the destruction of the archive, which institutionalizes the archival evil at the heart of the monument”. This is the basic distinction between the notion of the archive, as bequeathed to us by tradition (as a place of power and command, but also as the environment where the archons were) and the concept of archival evil, introduced by Derrida (2001). In fact, according to him, they are not separate forces, eros and thanatos are intertwined and this affects the understanding we have in the field of social and human sciences, as we do not have full access to data from the past. The archive of history that has been bequeathed to us leaves many edges, many cracks and that is why the interpretation will, then, always be permeated by ghosts, impressions, representations of the evil of the archive. A typical example is the destruction of archives carried out by the Nazis during the Second World War, which still reminds us of the problems of holocaust denialism3.

The comparison with the history of Hanold-Gradiva reflects on an “archive disease” that would also be present in the philosophy of education, since it also needs history for its self-understanding. We believe that these aspects, which present a possible flaw or lack, a void that leads to the possibility of transformation, but also to the adoption of repetitive outputs. These can be essential life maintenance routines and, at the same time, alien to the life-creating drive. And this deserves a reflection because, if such routine situations, in the pathological sense, persist, they should be fought in the field of education in general and in the philosophy of education in a special way.

Gradiva in the Philosophy of Education

The philosophy of education is not prescriptive but guides the teaching and learning process. While educational policies and curriculum are concerned with “what to teach” and methodologies and techniques seek the best alternatives of “how to teach”, the philosophy of education asks itself about the “for what” ends, goals or horizons are we wanting to educate. The ends focus on the other components of the educational process, allowing education to have intentionality as a characteristic of the educational act, leaving behind the ghosts of voluntarism, indoctrination, spontaneity and its own instrumentalization. That is why the philosophy of education acts in a disruptive sense, in relation to merely instrumental or naive precepts in dealing with pedagogical knowledge, to assist in the (pedagogical) self-clarification of students and educators. Thus, among the possible contributions of the philosophy of education is that of reviewing pedagogical thinking in its relationship with the past, criticizing the idea of the archive as something outdated or fossilized in its happening. And yes, understanding it as something alive, which needs to be contextualized in its historical becoming.

Such is the confrontation that we propose to make in relation to the compulsion to repeat that we refer to, which can occur due to the institutionalization of the philosophy of education itself in the syllabi of the disciplines and in the archive of the curricula of the licentiate degrees, which reinforce outdated dichotomies between theory and practice. Although there has been great progress in theoretical debates, unfortunately its incorporation into the curricula of the licentiate degrees is still sometimes imprisoned in repetitive, abstract and lifeless formulas. This is exactly what happens with education in general, described by António Nóvoa (1999, p. 13) as a victim of the theory and practice dichotomy, that is, “[…] from the excess of the languages of international specialists to the poverty of teacher training programs”, or else captive “[…] of the excess of scientific-educational discourse to the poverty of pedagogical practices”.

It is not uncommon for the philosophy of education, as well as the fundamentals in general, to be among the first subjects that students have contact with in the curricular structures of licenciate courses. And this is because, confused with the linear and historicist view of knowledge, the philosophy of education is no longer alive and active in the various interfaces and exchanges that it can establish with the knowledge of other educational sciences.

An example is found in the study carried out by Bernadete Gatti, in Brazil, between the years 2008-2009, in the curricula and syllabi of degrees in pedagogy, Portuguese language, mathematics and biological sciences. There, Gatti (2010) notes that the area of fundamentals of education is responsible for about 43% of the workload of these courses, along with the varied and general subjects, called “other knowledge” and “complementary activities”. In addition, this article presents some tables (Tables 8, 9, 10 and 11) in which the fundamentals of education appear in the foreground, dichotomizing theory and practice in teacher training, which leads the author to suggest that:

The training of professional teachers for basic education has to start from their field of practice and add to it the necessary knowledge selected as valuable, in its foundations and with the necessary didactic mediations, especially because it is training for educational work with children and adolescents

(Gatti, 2010, p. 1375).

This is a specter to be fought, since, because it is located in the foundations, it does not mean that the philosophy of education should move from the primacy of theory to that of simply practice, which repeats the theory and practice dichotomy without offering a solution. At this point, one cannot forget Heidegger’s objection to the famous statement of Karl Marx’s 11th thesis on Feuerbach, that philosophers until now have only interpreted and not changed the world. Heidegger will respond that philosophy is essential in any concept of sociopolitical change, including Marx’s concept of a classless society. And for the transformation to take place, it would be necessary to develop a new interpretation, as Heidegger states when he speakes in opposition to this thesis of Karl Marx (Martin Heidegger..., 2007).

Furthermore, since philosophy is the experience of thinking about thinking itself, how will this occur at the expense of contact with other dimensions of pedagogical knowledge? Therefore, it would be interesting if it could occupy a space in the movement of courses curricula, understood as action-interpretation at the same time. And not located right at the beginning of the courses, as if there was a “secret” to be revealed. Such a position still breathes the remnants of metaphysics, linked to the search for the arkhê, of the prevailing principle that elevates it, as Habermas (1989) already mentioned, to the category of “judge of culture” and not of hermeneutic and dialoguing interpreter standing on equal footing with the other sciences.

Thus, it would be necessary to review the position occupied by the philosophy of education in the curriculum of undergraduate courses, which already predisposes it to be a discipline interpreted close to an “archeological vestige”. Because it is a misunderstanding of the archive, insofar as it is inserted in the historical and philosophical foundations of education, it does not mean that the philosophy of education should be confused with fossilized knowledge. On the contrary, it is in this field that it can be justified as a living discourse for the present time, as it is always being updated with the renewal of concepts that give new meaning to its relationship with tradition. Even less, to be a corollary item only of the curricular practice, renouncing its interpretive function in the constant coming-to-be of the real. The silencing of the debate in this sense has contributed to the emergence of discourses that are refractory to reflection on the foundations of education, when they are only focused on doing and not on the theory that structures and informs practice. In the case of philosophy of education, the vacuum of reflection on its place in the theoretical-practical discussion of education in general, and in the insertion of the curriculum in a special way, has given rise to proposals for its shortening in the field of teaching degrees to postgraduate courses.

This has certainly contributed, among other factors, to the low level of completion of these courses and, in addition, to the negative numbers of growth in these same courses in the country (Gatti, 2010, p. 1361). This panorama requires a new interaction between theory and practice, which translates into a different understanding regarding the position occupied by the philosophy of education in the archeology of the knowledge of training for teaching. And this generates the need to go further, to advance their goals, a feeling shared by Charlot (2020, p. 11) in relation to the field of education as a whole, when he comments:

If we are not able to go beyond the current ‘study for a good job later’ and educate our children as members of a species responsible for the current and future state of the world, it will be very difficult to escape these outbreaks of barbarism that we are already seeing and whose new forms are proudly announced to us by posthumanism.

In this debate, we glimpse potent challenges for philosophy of education and the humanist tradition present in various fields of teaching degrees that require some questions: what step can philosophy of education advance on inspired by the context of archival evil? Considering that Gradiva’s step corresponds to the passage from the dream-delusion to the real and, as we saw from Derrida, this only occurs mediated by ghosts, that ghosts need to be faced in the relationship between philosophy of education and their insertion in the curricula of teaching degrees? And more, how to take this step without losing its charm?

The philosophy of education among archival evil ghosts

Regarding its shortening or exclusion from the curricula, we can mention that, even in the 90s of the last century, when the theories of education divided educators in Brazil and in the world, they were much debated and had a privileged space in the curricula of the courses of teacher training, from undergraduate to graduate courses. However, the criticism that followed proposed that rivalry be left aside, after all “[…] education is no longer thought of from ‘currents’ and ‘trends’ that limit and divide, but according to horizons and perspectives that they add up and include” (Trevisan, 2006, p. 24). Thus, instead of dividing and opposing, rather the theories of education should unite us, understanding the strength of the great paradigms of knowledge and the evolution of world images. However, since certain consensuses were reached – such as the commitment of education to democracy, for example, as already advised by great educators such as John Dewey, Anísio Teixeira and Paulo Freire ‒, they began to be discredited, enjoying little prestige and space in the curricula from undergraduate to graduate courses. Therefore, philosophy of education should complement this step, which implies moving away from ossified and lifeless formulas, which tie it to trends and currents that clash, but without being able to overcome the real towards the opening to new tasks and experiences of thought.

Furthermore, the change in the relationship from traditional pedagogy to new pedagogy, that is, one that maintained a strong concept of authority and another that opens up to a concept that incorporates democracy in decisions, posed a challenge from now on to systems of teaching, which implies combining participatory and inclusive methods without the loss of coordination of pedagogical actions. In other words, as Charlot (2019, p. 167) puts it well, equating the relationship between “desire” and “norm”; however, what we have today in education theories is a “pedagogical bricolage and hybrid practices”.

In order not to get caught in the traps of this crisis, in addition to recovering this debate, it would be necessary to complete the step to be taken by the philosophy of education, in which it should not lend itself to producing only diagnoses of the social and political conjuncture. The philosophy of education has historically been confused with the critical role of period analysis in the social sciences, which has given it a unique critical capacity. However, only the criticism of culture is not enough today, in the hypersomber world we live in, ravaged by catastrophes and tragedies at all times. It is necessary that philosophy intervenes in the debate in a more consistent way, activating its descriptive, comprehensive and normative instance at the same time. Therefore, it could make sense to develop a prospective view of the whole from an ethical and social point of view at the same time. Thus, it would not be content to catalog social pathologies, their symptoms and mutations exclusively, which in itself is very important. But, going further, it could suggest new ways of encouraging a hopeless world, that is, not sticking to diagnoses of the time only, but also proposing alternatives for living well.

One of the proposed solutions is to recover the discussion about themes and problems of the common human world that involve the totality, exploring its ethical-social function, as is the case of the discussion about catastrophes and tragedies. After all, as Paviani (2016, p. 18) refers from Eric Weill: “The history of philosophy is the history of the refusal of violence by reason”. This is not a strange situation to what we have been addressing, given that it is the backdrop that mirrors Hanold and Gradiva’s novel – the ruins of the Pompeii catastrophe.

Philosophy of education as an archaeological search for knowledge

The proposal outlined so far leads the reflection to developing an internal look at its traditions, even if contaminated by the death drive of the archival evil. In this dive many pearls can be found, as Hannah Arendt (2008, p. 222) testifies about the work of the narrator in the work of Walter Benjamin,

Like a pearl fisherman who goes down to the bottom of the sea, not to dig it up and bring it to light, but to extract the rich and the strange, the pearls and the coral from the depths, and bring them to the surface, this thinking probes the depths of the past – but not to resurrect it as it was and contribute to the renewal of extinct eras.

Benjamin will say that the process of destruction and decay that leads to ruin can also be a process of crystallization in corals and pearls. So it is with thought, when it produces itself in the gaps of time, carried out by catastrophes and tragedies, allowing, in the hermeneutic plunge of the past, “fragments of thought” to resurface. At this point, it would be interesting to take a new archaeological dive into the history of philosophy, seeking contributions that allow the philosophy of education to contribute to rethinking our relationship with catastrophes and tragedies, and also, with the elaboration of trauma, present in the notion of archival evil, as Solis (2014, p. 375) interprets it:

Archival evil establishes as a name a game with the contemporary historical context, the context of the ‘disasters that marked the end of the millennium’, in which the Archives of Evil are under discussion, archives for so long interdicted, diverted, concealed, if not destroyed. For example, proof of the horrors practiced by Nazi domination and the holocaust; the current genocides (they are reported daily) constantly promoted by the intense wars in various parts of the world, generally encouraged by the hidden interests of the powers interested in oil, arms sales, etc.; the persecution of outlaw states, with the American interventionist policy, the institution of globalization, etc.

Catastrophe is a threat that today hangs over all humanity due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the effects of global warming, among other reasons, and, in this way, the philosophy of education reflects on why to educate, in what direction could walk mankind.

Although the elaboration of trauma is of the order of the singular, which requires the cultivation of resilience, we can reflect on the fact that the catastrophe, being a breaking point in the natural course of events, is also a new beginning, a turning point in our troubled lives. The loss of references and measuring instruments, which we usually had, which generated the trauma, draws attention to elements that we were not seeing or even sizing properly before. Therefore, it is urgent to think of catastrophe not as a sign of closure, but as a possibility of learning and cultural elevation – and this illustrates Gradiva’s step –, perhaps as a turning point to provide a new landscape. If we understand the calamity in this sense, we can be better prepared and not be surprised as if it were the first time. In this way, the philosophy of education can contribute to the creation of a training model that is sensitive to the prevention of catastrophes and tragedies, as well as to the elaboration of trauma, having as a parameter of understanding the narratives of the testimonial literature and the initiatives referring to the experiences of architecture of destruction – the holocaust.

To handle such Herculean tasks, we have the interdisciplinary knowledge that literature and psychoanalysis, philosophy and education indicate on the subject, betting on knowledge of prevention – such as knowing how to prevent and knowing how to express –, so as not to fall into the trivialization of the pain of other. In general, the knowledge in vogue in the field of education refers little to these topics, and the academic training of teachers is largely based on know-how (pedagogy of competences), revealing important gaps and challenges for the pedagogical process from now on. In other words, it is necessary to rethink the knowledge of teaching, in view of “knowing how to express” the catastrophe and “knowing how to prevent it”, or “knowing how to avoid it”, under the interpretative, expressive and normative contribution of the philosophy of education.

And also, to think about the need for a new modernity, less concerned with the relationship of technical and conceptual domination of nature and, yes, with the development of values dear to democratic life, socio-emotional or relational values, such as sensitivity, acceptance, empathy, resilience, cooperation and training; the latter understood, in one of its best definitions, as the constant work of self-training. After all, if life is not just made up of obligations, we still have the right to enjoy leisure, culture, access to goods and the cultural legacy of humanity, as well as to fight for democratically constructed consensus in public life.

Conclusion

The article sought to rethink the contribution of the philosophy of education inspired by the book Gradiva, by Jensen, according to the interpretation of Freud-Derrida. Freud’s analysis warns of the risk of getting lost in the dictates of positive science, simply obeying a technical-methodical rule. It was this that led Hanold to fall into the pure fantasy of the spectral delirium that led him to search for Gradiva in the city of Pompeii, even though she was always living within a few meters of his house. With Derrida, we realize that it is necessary to take Gradiva’s step, but without falling into the enchantment of the search for his first impression, desired by Freud, since such an initiative is contaminated by a metaphysical vision of knowledge. Differently, as the archival evil is at the heart of the archive, the philosopher infers that the narratives are permeated by productions of their ghosts, which regulate the process of interpretation.

From these reflections, we realize that such issues still impact philosophy of education, insofar as its position, in the archive of teacher training courses, is still tied to metaphysical positions of the order of knowledge, as an arkhê and not as a movement of constant action-interpretation. In order to contribute to the debate, inspired by Gradiva’s step, we then suggest a broader horizon to face, that is, rethinking the position that the philosophy of education occupies in the curricula of undergraduate courses. In order for it to be able to situate itself in this new context, that is, in the movement of the curriculum in a more productive way, this step should be complemented with some more additions, such as resisting the tendency to serve only as a diagnosis of the epoch and venturing into new themes and problems emerging from the contemporary context, such as the theme of tragedies and catastrophes. In this way, we indicate the need to make a new dip in its tradition in search of new pearls, which will reinscribe its participation in the order of writing of the teaching degree courses. Such initiatives could assure to philosophy of education, as endorsed by Dalbosco and Mühl (2020, p. 266), “[…] the role of contributing to educational research to make an investigative immersion in the past cultural and pedagogical tradition”.

Since, due to the archive evil, the areas that need history to understand themselves present spaces in the writing of pedagogical discourse – absences, ghosts, repetitions –, it would be better if they could also be traits that signal new horizons of pedagogical reflection. In view of this, the step we propose suggests the possibility of liberation from the state in which philosophy of education is sometimes placed in the curricula of teacher training courses. Furthermore, it aims to outline possibilities or promises to face the evil ghosts of the archive, without losing its characteristic potency and grace.

If we are not going to find answers to such complex challenges, we believe that linking the themes and problems at hand with the humanistic tradition already means a certain advance in the discussion. We believe in this way to collaborate in the ethical and aesthetic training of current and future educators and in their valorization as a professional category, which is very outdated, reflecting on the position that philosophy of education occupies in the curricula of undergraduate to graduate courses realizing, as Derrida (2017, p. 17) suggests, “the glow of the beyond”.

1I appreciate the review and suggestions to qualify the text given by prof. Dr. Maurício Cristiano de Azevedo, from the Instituto Federal de Ciência, Educação e Tecnologia Farroupilha (IFFar-campus Santo Augusto).

2In the article Mal de arquivo – desafio para a filosofia da educação?, Trevisan, Azevedo and Rosa (2021) address the issue of Jewish culture linked to the foundation of psychoanalysis in more depth.

3The film Denial addresses this issue well, showing that the issue of denialism is also very strong in rich countries, involved in the issue of whether or not the holocaust exists.

REFERENCES

ARENDT, Hannah. Homens em tempos sombrios. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2008. [ Links ]

BIRMAN, Joel. Escritura e psicanálise: Derrida, leitor de Freud. Natureza Humana, São Paulo, v. 9, n. 2, p. 275-298, jul./dez. 2007. [ Links ]

BRASIL, Maria Cláudia Maia. A escrita do desejo: ressonâncias fantasmáticas em Gradiva. In: NUÑEZ, Carlinda Fragale Pate; SILVA, Egle Pereira da (Org.). O monstruoso em obras da literatura-mundo. Rio de Janeiro: Dialogarts, 2020. P. 50-63. Disponível em: http://www.dialogarts.uerj.br/admin/arquivos_tfc_literatura/O_Monstruoso_em_obras_da_Literatura-mundo.pdf#page=51. Acesso em: 03 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Fernanda. Gradiva de Dalí aquela que avança na arte. Coluna: Das travessias limiar em profundidade. Psicologia, Filosofia e Arte. Obvious, online, 2016. Disponível em: http://obviousmag.org/das_travessias_limiar_em_profundidade/2016/gradiva-de-dali-aquela-que-avanca-na-arte.html. Acesso em: 09 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

CHARLOT, Bernard. A questão antropológica na Educação quando o tempo da barbárie está de volta. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, v. 35, n. 73, p. 161-180, jan./fev. 2019. [ Links ]

CHARLOT, Bernard. Educação ou barbárie? Uma escolha para a sociedade contemporânea. São Paulo: Cortez, 2020. [ Links ]

DALBOSCO, Cláudio Almir; MÜHL, Eldon. Filosofia da educação e pesquisa educacional: fragilidade teórica na investigação educacional. Educação e Filosofia, Uberlândia, v. 34, n. 70, p. 253-279, jan./abr. 2020. [ Links ]

DERRIDA, Jacques. Mal de arquivo: uma impressão freudiana. Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará, 2001. [ Links ]

DERRIDA, Jacques. Gramatologia. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2017. [ Links ]

DERRIDA, Jacques; ROUDINESCO, Elisabeth. De que amanhã… diálogo. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editor, 2004. [ Links ]

FREUD, Sigmund. Delírios e sonhos na Gradiva de Jensen. Rio de Janeiro: Imago Editor, 2003. [ Links ]

GATTI, Bernardete. Formação de professores no Brasil: características e problemas. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 31, n. 113, p. 1355-1379, out./dez. 2010. [ Links ]

HABERMAS, Jürgen. Consciência moral e agir comunicativo. Trad. de Guido Antônio de Almeida. Rio de Janeiro: Tempo Brasileiro, 1989. [ Links ]

JENSEN, Wilhelm. Gradiva, uma fantasia pompeiana. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editor, 1993. [ Links ]

KANT, Immanuel. Crítica da razão pura. Trad. Valério Rohden e Udo B. Moosburger. São Paulo: Abril Cultural, 1980. [ Links ]

MARTIN HEIDEGGER Critiques Karl Marx - 1969. Publicado por hiperf289. 2007. 1 vídeo (1min34s). Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jQsQOqa0UVc. Acesso em: 08 de mar. 2021. [ Links ]

MENDES, Eliana Rodrigues Pereira. No passo da Gradiva. Estudos de Psicanálise. Rio de Janeiro, n. 28, p. 51-60, set. 2005. [ Links ]

NEGAÇÃO. Direção: Mick Jackson. Produção: Garry Foster; Russ Krasnoff. Intérpretes: Rachel Weisz; Tom Wilkinson; Timothy Spall. Inglaterra, 9 mar. 2017. (1h50min). [ Links ]

NÓVOA, António. Os Professores na Virada do Milênio: do excesso dos discursos à pobreza das práticas. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 25, n. 1, p. 11-20, jan./jun. 1999. [ Links ]

PAVIANI, Jaime. Conceitos e formas de violência. In: MODENA, Maura Regina (Org.). Conceitos e formas de violência. Caxias do Sul: EDUCS, 2016. P. 8-20, Disponível em: https://www.ucs.br/site/midia/arquivos/ebook-conceitos-formas_3.pdf. Acesso em: 08 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

SOLIS, Dirce Eleonora Nigro. Tela desconstrucionista: arquivo e mal de arquivo a partir de Jacques Derrida. Rev de Filosofia Aurora, Curitiba, v. 26, n. 38, p. 373-389, jan./jun. 2014. [ Links ]

TREVISAN, Amarildo Luiz. Paradigmas da filosofia e teorias educacionais: novas perspectivas a partir do conceito de cultura. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 31, n. 1, p. 26-36, jan-jun. 2006. [ Links ]

TREVISAN, Amarildo Luiz; AZEVEDO, Maurício Cristiano de; ROSA, Geraldo Antonio da. Mal de arquivo – Um desafio para a filosofia da educação? Educar em Revista, Curitiba, v. 37, p. 1-17, 2021. [ Links ]

Received: July 29, 2021; Accepted: February 23, 2022

texto em

texto em