Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educação e Realidade

Print version ISSN 0100-3143On-line version ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.48 Porto Alegre 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236124353vs01

OTHER THEMES

Vacant Seats: contradictions to the expansion of access to federal universities in Brazil

IUniversidade Federal do ABC (UFABC), Santo André/SP – Brazil

IIPesquisador independente, São Paulo/SP – Brazil

IIIUniversidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp), Guarulhos/SP – Brazil

The article analyzes the effects of changes in the minimum admission scores via SiSU in filling seats offered in Pedagogy courses at Brazilian federal universities, between 2010 and 2017. The results show that the mismatch between the level of demand in admission processes and the performance of registered applicants may prevent access to public universities when an expansion of around one million seats is still a promise of the Brazilian National Education Plan 2014-2024. Paradoxically, the almost univocal defense of the democratization of access to higher education in Brazil is not always accompanied in universities by an internal debate that considers the complexity of the admission processes and establishes criteria to minimize the generation of vacant seats.

Keywords Higher Education; Educational Inequalities; Access to Education; Public University; Enem (Brazil)

O artigo analisa os efeitos das alterações nas pontuações mínimas de ingresso via SiSU no preenchimento das vagas em cursos de Pedagogia das universidades federais brasileiras, entre 2010 e 2017. Os resultados mostram que o descompasso entre o nível de exigência nos processos seletivos e o desempenho dos candidatos inscritos pode impedir o acesso à universidade pública quando uma ampliação em torno de um milhão de vagas é ainda uma promessa do Plano Nacional de Educação 2014-2024. Paradoxalmente, a defesa quase unívoca da democratização do acesso à educação superior no Brasil nem sempre é acompanhada nas universidades por um debate interno que leve em conta a complexidade dos processos seletivos e estabeleça critérios para minimizar a produção de vagas ociosas.

Palavras-chave Educação Superior; Desigualdades Educacionais; Acesso à Educação; Universidade Pública; Enem

Introduction

Despite the Brazilian National High School Exam [Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio] (Enem) having been proposed as a mechanism for democratizing access to higher education and student mobility in Brazil, studies have shown that this is not actually happening. Regarding geographic mobility, Silveira, Barbosa and Silva (2015, p. 1101-1102) showed that “[…] the poorest states are unable to export their students to the six richest states in Brazil, with their seats being occupied by students from these same richer states”1. Research by Barros (2014) on ways of admission to higher education concluded that the fact that access to graduation via the Unified Selection System [Sistema de Seleção Unificada] (SiSU) is determined by the score obtained in the Enem implies that the exam operates in a similar logic to the traditional admission exam: “[…] students who did not have education aimed at this type of selection will continue in less favorable conditions to access higher education” (Barros, 2014, p. 1083). Although there are several ways of understanding the “democratization” of higher education and of designing research on the subject, Travitzki (2021) emphasizes that it is the integrated functioning between Enem, SiSU, policies of reservation of seats (quotas) and social support (student permanence) that produces the “democratizing effect” that, many times, in a simplistic way, the various research studies associate with isolated factors.

The phenomenon of dropout in the Brazilian Federal Higher Education Institutions (BFHEIs) is a topic that requires attention, in view of the demand for the expansion of higher education in the public sector established in the Brazilian National Education Plan 2014-2024 (PNE, Law No. 13,005/2014)2 and of the best possible use of public resources (Veloso et al., 2015). Although the criterion for allocating financial resources to BFHEIs depends, among other factors, on the number of students admitted each year, vacant seats always represent costs for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) – as all inputs must be present to offer the total of the seats. Thus, almost all the investment is made, regardless of whether all seats have been filled, with the exception of the Brazilian Student Assistance Plan resources (Pnaes), which are intended directly for students.

The academic debate on dropout in Brazilian public higher education, as pointed out by Coimbra, Silva and Costa (2021, p. 14), lacks a greater volume of empirical research and greater clarity regarding the definitions used, which could help determine the causalities of dropout and to distinguish what, within this broad phenomenon, “[…] can be called a social problem from what would not be so”3. In addition, several authors recognize that the consolidation of SiSU as the main route of admission into BFHEIs has brought new ingredients to the already intricate dropout debate (Flores, 2013; Czerniaski, 2014; Backes, 2015; Gilioli, 2016; Sousa, 2016; Nogueira et al., 2017; Ariovaldo; Nogueira, 2021; Cabello et al., 2021; Rosa; Santos, 2021).

SiSU was established in 2010 as a “[…] computerized system managed by the Ministry of Education (MEC), for admitting applicants for seats in undergraduate courses made available by the public higher education institutions participating in it” (Brasil, 2010). The previous system – that of university admission exams organized by the HEIs themselves – “[…] provided a tangle of overlapping test dates and costly travel for students who intended to apply for seats in more distant HEIs” (Gilioli, 2016, p. 36). Thus, in addition to reducing the costs of HEIs with the annual or biannual holding of their own admission exams, SiSU, by stimulating the geographical mobility of students, would in theory help increase the efficiency in filling the seats offered.

In practice, SiSU allows applicants to monitor, through constantly updated simulations, the cut-off scores of all courses, so that they can choose, at any time during the process, the two course options with the best chances of admission from their Enem score. Thus, the system induces applicants to make a strategic choice, in a kind of game (Abreu; Carvalho, 2016):

In the vestibular [the traditional admission exams in Brazil], the individual applies for a course and then takes an exam in which he needs to achieve a sufficient score to pass. SiSU reverses this dynamic: the individual already has a score and applies for two courses (first and second option) which he/she already knows much more confidently than in the exam, given the simulations made in the initial stage of SiSU, his/her real chances of being admitted

(Nogueira et al., 2017, p. 67).

The induction of this strategic behavior, as shown by Nogueira et al. (2017), imposes limits on the fulfillment of the promises associated with SiSU, among them the increase in students’ geographical mobility – since most of them are unable to stay in another city –, and the greater efficiency in filling the seats offered – since the choice for the “possible course” often leads to withdrawal of enrollment or dropout in the first semesters of the course. Along the same lines, Cabello et al. (2021, p. 458) observed that “[…] SiSU not only offers low attendance in enrollment, but also presents greater dropout in the first two years of university career”4. All these findings indicate that, therefore, there are many variables that influence the non-filling of new seats, which is not always well understood or sufficiently debated within the BFHEIs. Backes (2015, p. 94-95), for example, comments that SiSU implementation at Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso (UFMT)

[…] was a troubled process due to the lack of information about the norms and the consequences of their use. […] Even today, there is a lack of clarification on such numerous variables as incoming student’s profile, the follow-up of their trajectory within the institution, mobility between courses and institutions, in addition to the technical and administrative problems involved in the process, which lack information about how the filling of new seats in BFHEIs is influenced by factors such as: cancellations during the admission process of the Unified Selection System (SiSU), dropouts during the multiple calls in waiting lists or throughout the course, prolonged leave of absence (abandonment), relocations and transfers to other HEIs.

In some cases, seats are not filled due to the lack of applicants with the minimum score required by the institution in the Enem (or, when applicable, in the institution’s own admission exam). Considering that the applicant to seat ratio in BFHEIs is typically high, although differentiated between courses of greater and lesser prestige, the deliberate production of vacant seats in BFHEIs due to admission criteria incompatible with the applicants’ performance in the admission processes is a delicate topic, core of the problem that we propose to investigate.

In this article, we analyze the influence of changes in the minimum score for admission via SiSU on filling seats offered in Pedagogy courses at BFHEIs. The objective is to understand to what extent the speeches in defense of the democratization of access to higher education in Brazil and the expansion of the number of teachers trained in Brazilian public universities meet with concrete actions in the sense of establishing criteria that minimize the generation of vacant seats in courses of teacher training.

To this end, we carried out an extensive survey of the contracts of adhesion to SiSU of Brazilian federal universities that offered in-person Pedagogy courses between 2010 and 2017. The minimum admission scores adopted by the BFHEIs for these courses were crossed with data from SiSU on the number of vacant seats and annual competition in them, from the Brazilian Higher Education Census (conducted by Inep) for the same period. The data thus obtained were analyzed: 1) globally, with a view to investigate the effects of changes in the minimum admission scores on filling seats; and 2) locally and qualitatively, with a view to isolate effects such as university campus location, size of the minimum admission score, and the existence of concomitant mechanisms for admission into BFHEIs.

Methodology

Causal effects in time series are frequently investigated by the Granger method, which is based on two assumptions: 1) the cause precedes the consequence; 2) the cause has some unique information that justifies its inclusion in the consequence model. However, this method is not suitable for the investigated object, since the changes in the minimum admission scores are occasional and occur at different times for each course. In addition, the percentage of seats filled is influenced by other variables, such as the annual applicant to seat ratio.

Thus, given the particularity of the phenomenon studied, we developed scripts in R for data analysis on different levels. The basic unit (disaggregated) of the data is the Pedagogy courses of the Brazilian federal universities. In some analyses, aggregated data by institution were also selected. The database used includes all the higher education courses in Pedagogy offered at Brazilian federal universities, consisting of public data from the Brazilian Higher Education Census5 and data provided by the BFHEIs themselves, based on a request based on the Access to Information Law (LAI, Law No. 12,527/2011).

Course data were initially analyzed together, and, later, we confined the analysis only to the years in which there were changes in the minimum admission scores. Thus, for each course, changes in the minimum admission scores were identified and the two years (preceding and following) each change were selected. The choice of this data subset allows for a more focused analysis of the effects, assuming that a change in the minimum admission score – within the game mechanism induced by SiSU – should generate an instant effect on filling the seats offered in that same admission process. Any possible effects lasting longer than one year were disregarded in this study. We also carried out a linear modeling of seat filling, considering that each university produces its own public notices with admission rules for SiSU and, therefore, can be considered an elementary unit of “seat policy”.

Results

We present below the description of the variables, and, in sequence, we discuss the global and local effects of changes in the minimum admission scores via SiSU on filling seats in Pedagogy courses at 52 Brazilian federal universities.

Description of Variables

We analyzed data related to admission in 150 Pedagogy courses (including part-time options of the same course and multi-campus offers), covering the period from 2009 to 2017. Tables 1 and 2 describe the main variables used:

Table 1 Variables analyzed in this study (aggregated by year). In-person Pedagogy courses, Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

| YEAR | Filling of seats (%) | Competition (applicants/seat) | Minimum score (average) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 90.81 | 3.93 | – |

| 2010 | 90.79 | 6.99 | 33.42 |

| 2011 | 90.05 | 11.51 | 17.12 |

| 2012 | 94.87 | 15.80 | 16.25 |

| 2013 | 92.96 | 15.12 | 46.82 |

| 2014 | 90.35 | 21.60 | 70.26 |

| 2015 | 88.48 | 22.01 | 88.61 |

| 2016 | 92.42 | 21.64 | 111.28 |

| 2017 | 94.35 | 22.13 | 111.02 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009).

Table 2 Enem minimum admission scores by area (aggregated by year). In-person Pedagogy courses, Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

| YEAR | Essay | Math | Languages | Natural Sciences | Human Sciences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2010 | 32.89 | 32.89 | 34.21 | 32.89 | 34.21 |

| 2011 | 25.41 | 15.26 | 15.99 | 14.10 | 14.83 |

| 2012 | 19.90 | 14.75 | 16.37 | 14.46 | 16.37 |

| 2013 | 58.71 | 44.37 | 44.50 | 42.19 | 42.53 |

| 2014 | 92.87 | 63.40 | 66.22 | 62.32 | 65.73 |

| 2015 | 118.87 | 81.11 | 81.78 | 79.97 | 80.53 |

| 2016 | 148.95 | 101.07 | 102.24 | 101.17 | 102.93 |

| 2017 | 146.04 | 100.68 | 102.73 | 101.85 | 103.95 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

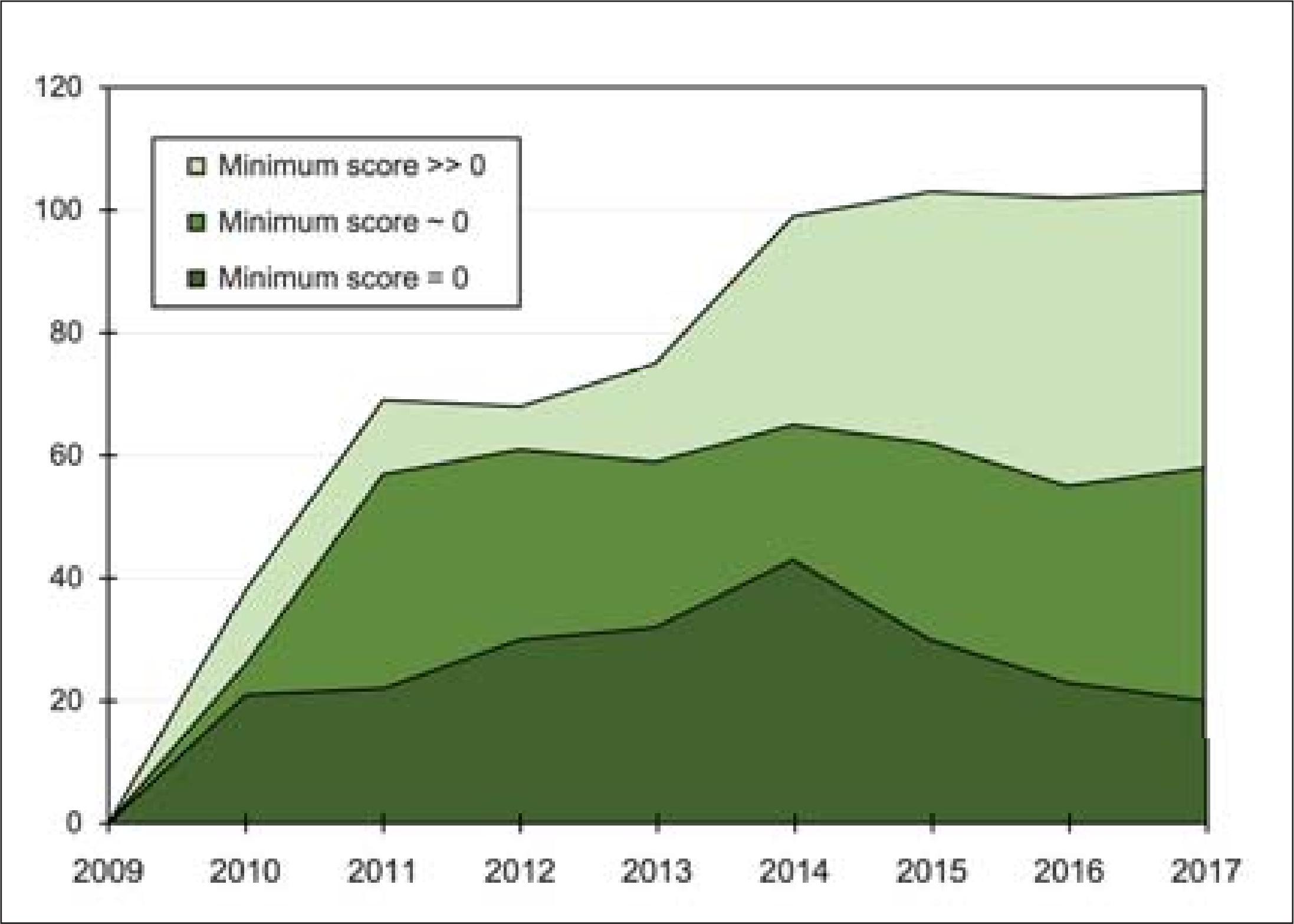

Figure 1 shows the cumulative minimum admission scores for Pedagogy courses at universities that joined SiSU between 2009 and 2017, differentiating between institutions that adopted minimum scores equal to zero, approximately equal to zero and greater than zero. The adoption of minimum scores higher (but close) to zero showed a growth trend in the analyzed period. In 2011, MEC began to require, as a minimum condition for participation in the SiSU, the achievement of a score greater than zero in the essay of the Enem – evoking the former MEC Ordinance No. 391/2002, which established such a condition for all higher education admission processes in Brazil. Hence, scores lower than 20.00 (on a scale of 1,000.00) have been adopted by the BFHEIs not only in the essay, but in all four areas of the Enem6.

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

Figure 1 Cumulative minimum (average) scores per year. In-person Pedagogy courses, Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

Figure 1 also shows that the number of Pedagogy courses in Brazilian federal universities that admit applicants via SiSU has stabilized around 100 since 2014. For most BFHEIs, therefore, the period between 2009 and 2017 was one of adaptation of its internal admission processes to SiSU. In many institutions – at least for Pedagogy courses –, this transition occurred with the maintenance of two concurrent admission systems (their own admission exams and SiSU) and with the gradual increase in the number of seats offered via SiSU. This, as we will see later, nuances the effect of the unified system’s game mechanism on filling new seats.

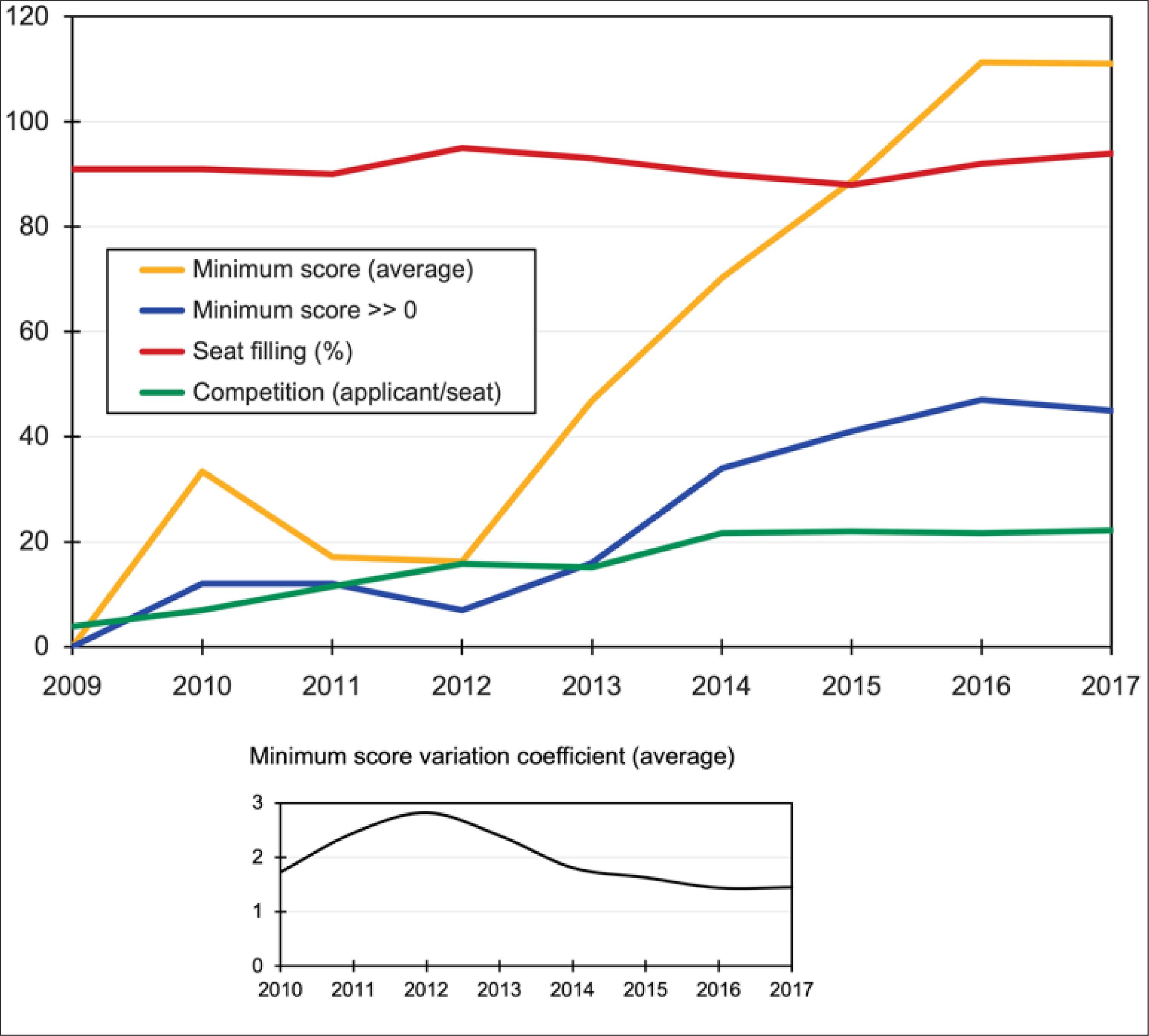

Figure 2 provides a representation of the general trends observed for the variables, considering the characteristics of the courses aggregated by year. The main graph shows a systematic increase in competition in Pedagogy courses until 2014, when it stabilized around a ratio of 20 applicants to seat. This is one of the trivial effects of the adhesion, by Brazilian federal universities, to a centralized admission system that induces strategic choices in applicants, corroborating the findings of Nogueira et al. (2017) and Cabello et al. (2021): the game mechanism that increases competition also decreases the filling of seats in BFHEIs.

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009) and the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

Figure 2 General trends for aggregated variables by year (top graph); and coefficient of variation of the minimum admission score (bottom graph). In-person Pedagogy courses, Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

At the same time, in Figure 2, it is observed that the minimum scores for admission in the Pedagogy courses investigated increased significantly between 2012 and 2016. Between 2012 and 2015, in turn, the percentage of filling seats decreased7. This relationship is in line with the initial hypothesis that the increase in minimum admission scores may be, in addition to the effects already described in the literature, reducing SiSU’s effectiveness, generating more vacant seats and, ultimately, preventing access to public higher education.

The coefficient of variation of the minimum average score (Figure 2, bottom) tells how much these scores are dispersed, ignoring the global average value. Thus, it allows comparing values that vary greatly from each other, as is the case of the minimum admission score in the investigated period. Analysis of the coefficient of variation shows that, between 2010 and 2012, the minimum admission scores became increasingly different from each other. In 2013, following the increase in the number of Brazilian federal universities that joined the SiSU for admission in Pedagogy courses, a reversal of the previous trend was observed: the minimum admission scores started to converge more across one another. In 2016, the variation between them stabilized at around 1.5 standard deviations.

Isolating the Effect of Changes in Minimum Admission Scores

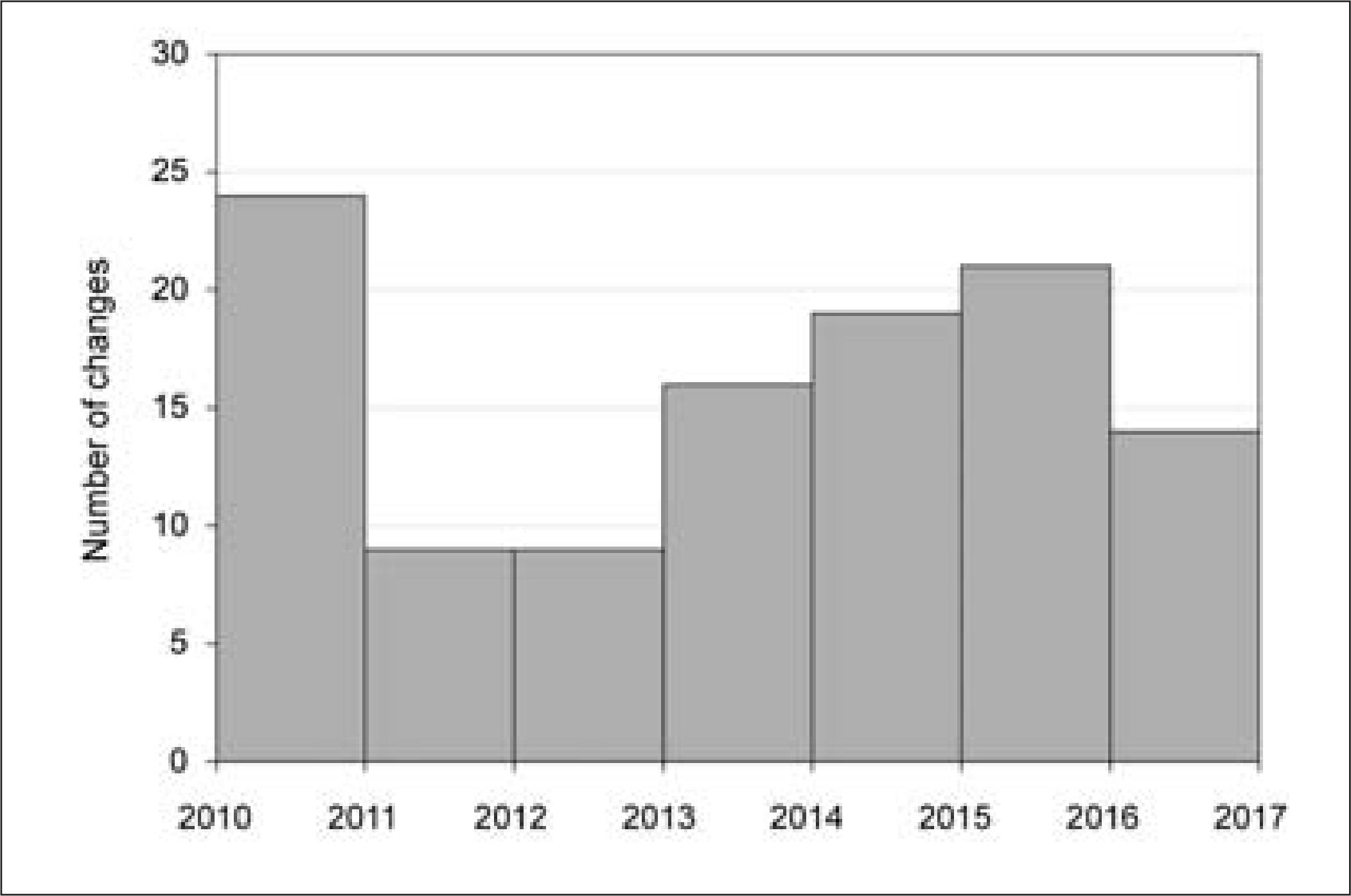

We have identified 112 changes in the minimum admission scores (essay and average of the four areas in the Enem) of the investigated Pedagogy courses. Each change was taken independently of the others in the analyses that follow. Figure 3 indicates that the most turbulent period in terms of the number of changes took place between 2010 and 2011, before the stabilization of the number of Brazilian federal universities that adopted SiSU in their admission processes. The variation accumulated by university between 2009 and 2017 is described in Table 7 (Annex).

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

Figure 3 Changes in minimum admission scores by biennium. In-person Pedagogy courses, Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

To test the hypothesis that the increase in the minimum admission score tends to generate a decrease in the percentage filling seats, we fitted a linear regression model on two data sets (Table 3). In the complete data set, variations in minimum scores had no significant effect on filling seats, while competition had a positive effect. Here, therefore, the effect of the SiSU game mechanism prevails, which increases competition and reduces the filling of new seats due to the disconnection between the applicants’ strategic choices and their real possibilities of filling the seats.

However, in the data subset that includes only the year before and the year after each change in the minimum admission score, an inverse pattern is observed: competition has no longer a significant effect on filling seats, possibly due to the most important effect of the change in the minimum score. In short, the linear regression analysis indicates that the increase in the minimum scores for admission in Pedagogy courses tends to generate a decrease in the percentage of filling seats – an additional effect, therefore, to those already observed in previous works. However, this general relation may vary across universities.

Table 3 Linear regression analysis. Change of minimum admission scores to in-person Pedagogy courses, Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

| Entire period 2009-2017 |

Only years with minimum admission score change |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficient | p-value | coefficient | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.919 | < 0.001 | 0.911 | < 0.001 |

| Minimum score (average)* | 0.000 | 0.90 | – 0.021 | < 0.05 |

| Competition* | 0.013 | < 0.01 | 0.010 | 0.23 |

*The explanatory variables were standardized for comparison purposes.

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009) and the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

Case Analysis

By means of an annual contract of adhesion to SiSU, the institutions define, for each admission process, the minimum scores for the essay and the four areas of the Enem, in addition to weights for each of them. These parameters are defined for each course, so that, within the same institution that offers Pedagogy courses in different university units or campuses, minimum admission scores and weights may vary. In the investigated period (2009-2017), most of the Brazilian federal universities were in the process of joining the SiSU, so that in many BFHEIs only part of the seats was available for admission via the unified system. We have selected below a series of cases that allow to identify the conditions in which the increase in minimum admission scores leads to an evident decrease in the filling of new seats.

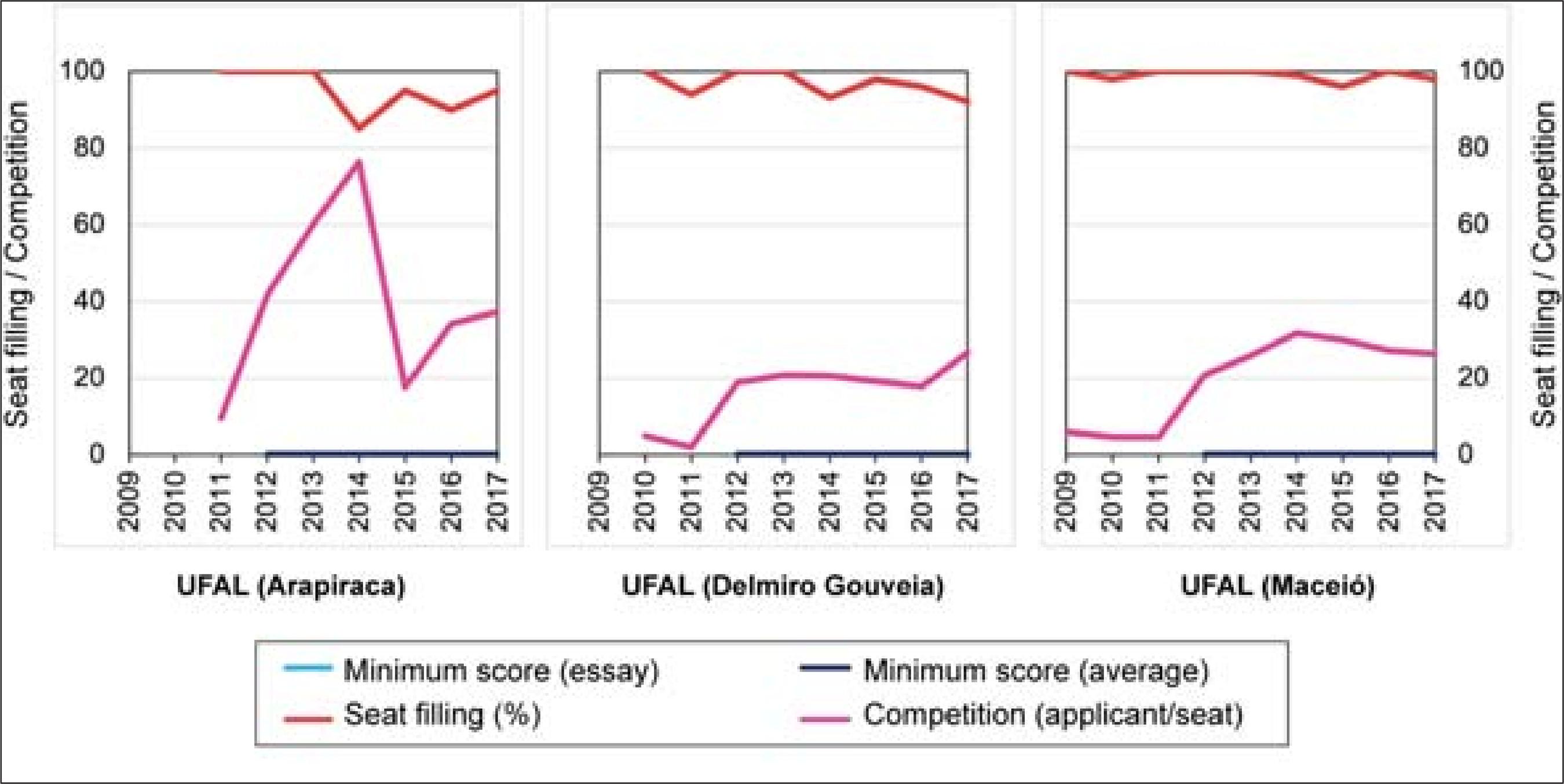

The trivial case, which exemplifies the exclusive effect of joining the SiSU in filling seats, is that of the Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL). Here, the minimum admission scores for Pedagogy courses remained the same throughout the period: 0.01 (essay) and 0.00 (average of areas), with constant weights. In addition, 100% of the seats were offered for admission via SiSU, so that the associated game mechanism – the real conditions for successful applicants to enroll – is what truly weighs on filling seats and on competition observed in the period (Figure 4).

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009) and the admission rules provided by UFAL.

Figure 4 Filling of new seats (%) and competition. SiSU, in-person Pedagogy courses, Universidade Federal de Alagoas, 2009-2017. The minimum admission scores were the same throughout the period: 0.01 (essay) and 0.00 (average of the areas), always with weight 1. The number of seats offered via SiSU was also constant in the period: 100%

The difference between the three UFAL campuses with Pedagogy courses – two in the interior of the State of Alagoas and one in the capital – is essentially the number of seats offered. In 2014, for example, 40 seats were offered on the Arapiraca campus, 80 on the Sertão campus (Delmiro Gouveia) and another 240 on the AC Simões campus (Maceió, the capital of the State). Specifically, on the Arapiraca campus there was a significant increase in competition until 2014, which fell in 2015 to levels compatible with the other campuses. Among the possible explanations for the phenomenon is, firstly, the lower number of seats offered (beginning of the classes in the second semester of the year) and then, from 2015, the entry into force – only at the Arapiraca and Sertão campuses – of a regional inclusion policy that established a 10% increase in the final score of the Enem for applicants who have attended high school in regular and in-person schools in the municipalities located in the countryside of the State of Alagoas (UFAL, 2015; Sousa, 2016).

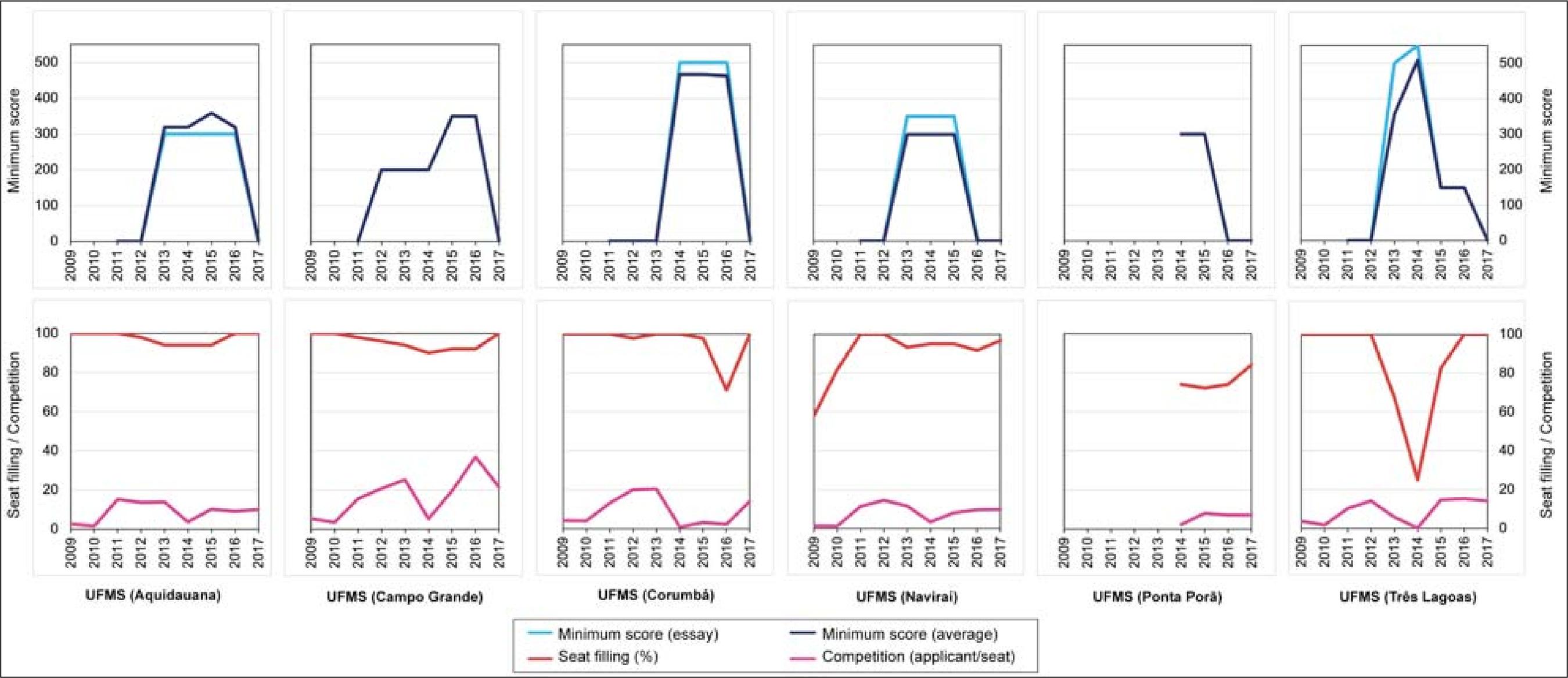

Let us now look at the case of the Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), which also offered 100% of the Pedagogy seats for admission via SiSU, but which, unlike UFAL, modified the minimum admission scores and their respective weights (for several times and differentially) at their six campuses between 2011 and 2017 (Table 8, Annex). Figure 5 shows that increases in minimum admission scores for values of about 300.00 are related to consistent (albeit subtle) decreases in the filling of seats, while increases for values of about 500.00 points significantly reduce the filling of seats, since only applicants with much higher scores can choose the Pedagogy course and many end up dropping out during the enrollment process, for reasons already discussed in previous works. High minimum admission scores reduce the size of waiting lists, making it inevitable to produce many vacant seats.

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009) and the admission rules provided by UFMS.

Figure 5 Minimum scores (average and essay), filling of new seats (%) and competition. SiSU, in-person Pedagogy courses, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, 2009-2017. The number of seats offered via SiSU was constant in the period: 100%. The low values of competition consistently recorded for the year 2014 are probably due to problems in filling in the data for the Brazilian Higher Education Census

The effect of the abrupt increase in minimum admission scores was particularly felt at the Três Lagoas campus, where the filling of new seats fell below 30% in 2014. Table 8 (Annex) indicates that admission parameters (minimum scores and weights) for Pedagogy seats in Três Lagoas varied five times between 2011 and 2017, with disastrous effects from the point of view of filling seats. The general picture in Figure 5, moreover, suggests that there was no internal debate at the UFMS units regarding the complexity of SiSU. In 2017, however, the minimum admission scores for Pedagogy courses dropped to 0.01 for all campuses (with different weights, however), reflecting the likely adoption of an internal policy at the university.

As at UFMS, the minimum admission scores and their respective weights varied at Universidade Federal do Tocantins (UFT), although here the variation was the same across the four campuses with Pedagogy courses. Nevertheless, the adhesion to SiSU by UFT was gradual between 2011 and 2017, so that the campuses made available different fractions of the seats for admission to the unified system and kept part of the seats for admission via their own exams. It was only in 2015 that the campuses of Arraias, Miracema do Tocantins and Tocantinópolis started to provide 100% of the seats for SiSU. In the capital Palmas, this only occurred in 2017 (Table 4).

Considering that the filling of seats is affected by adhesion to SiSU itself, the UFT and other Brazilian federal universities, by gradually adhering to the national unified system, were able to vary their admission parameters in a relatively controlled way to monitor their effects over time (Figure 6). The minimum score for the essay, for example, was raised for all Pedagogy courses at UFT in 2014 from 0.01 to 300.00, with the weights and the number of seats offered in the previous year and across campuses remaining unchanged. The result is that, in 2015, it was possible to identify the effect of the availability of the total number of admission seats for SiSU, which produced vacant seats, particularly on campuses in the countryside, less attractive to the geographic mobility desired by the unified system.

Table 4 Seats offered (%) for admission via SiSU. In-person Pedagogy courses, Fundação Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 2010-2017

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by UFT.

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009) and the admission rules provided by UFT.

Figure 6 Minimum scores (average and essay), filling of new seats (%) and competition. SiSU, in-person Pedagogy courses, Fundação Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 2009-2017

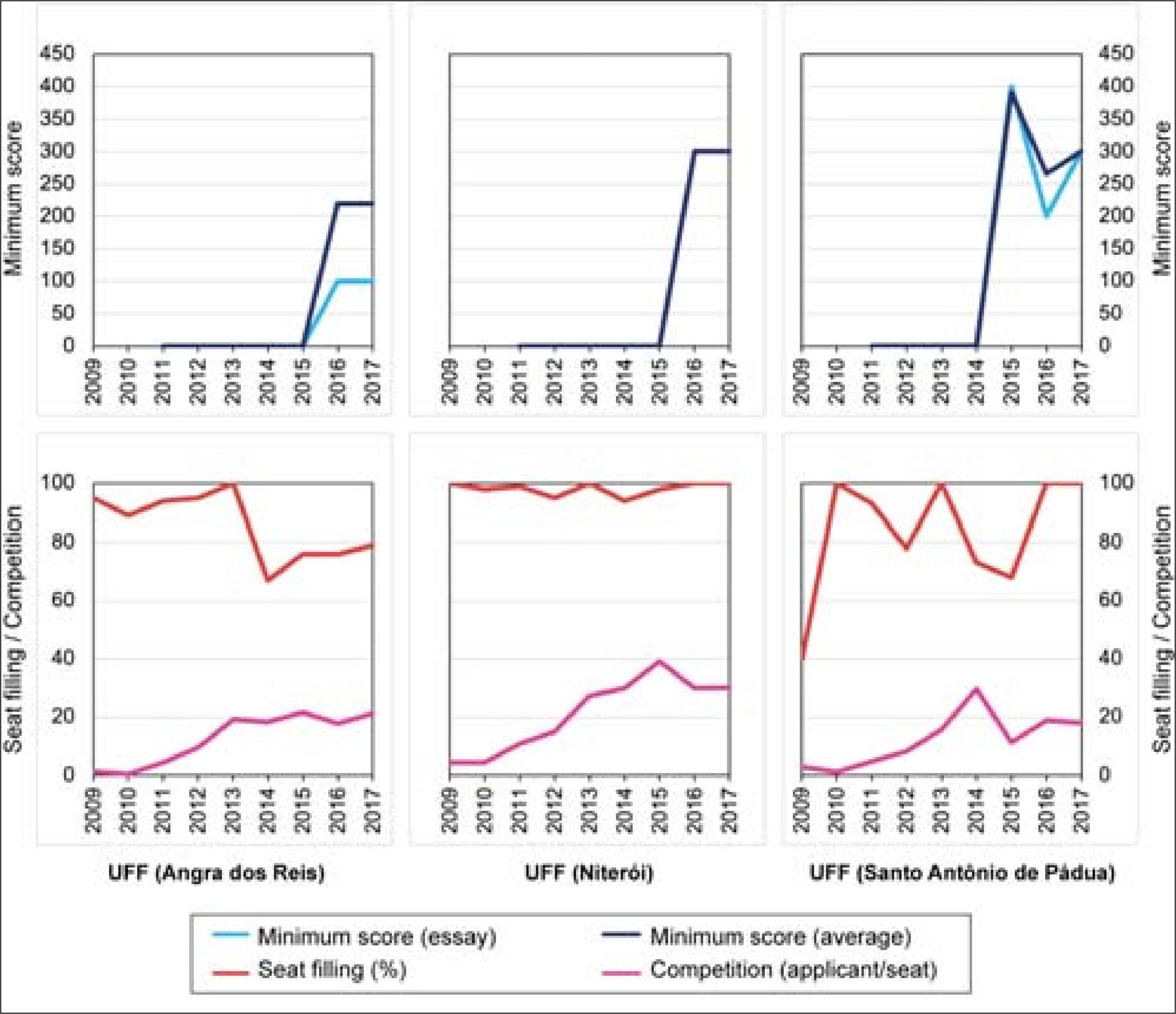

The case of Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), located in the state of Rio de Janeiro, combines the characteristics of the previous ones. Here, all the parameters varied in the investigated period and across campuses: the number of seats available for admission via SiSU (Table 5) and the minimum admission scores and respective weights (Table 9, Annex). At UFF, the Angra dos Reis and Santo Antônio de Pádua campuses started to make 100% of the seats available for admission via SiSU in 2013, while the Gragoatá campus (Niterói) kept this rate below 50% throughout the period – with the rest of the seats offered for admission via their own exam (Table 5). This is one of the variables that impact the filling of Pedagogy seats: by keeping a reduced number of seats for admission via SiSU, the institution maintained higher filling rates in Niterói (Figure 7), even though the minimum admission scores have increased from 2016 (Table 9, Annex). As it occurred at UFMS Três Lagoas, between 2011 and 2017 the minimum scores and weights varied three times in the Pedagogy course at UFF in Santo Antônio de Pádua, with evident impacts on seat filling (Figure 7).

Table 5 Seats offered (%) for admission via SiSU. In-person Pedagogy courses, Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2011-2017

| Campus | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angra dos Reis | 21.7% | 21.3% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Niterói | 16.3% | 20.0% | 48.8% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% |

| St. Antonio de Pádua | 20.0% | 33.8% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by UFF.

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009) and the admission rules provided by UFF.

Figure 7 Minimum scores (average and essay), filling of new seats (%) and competition. SiSU, in-person Pedagogy courses, Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2009-2017

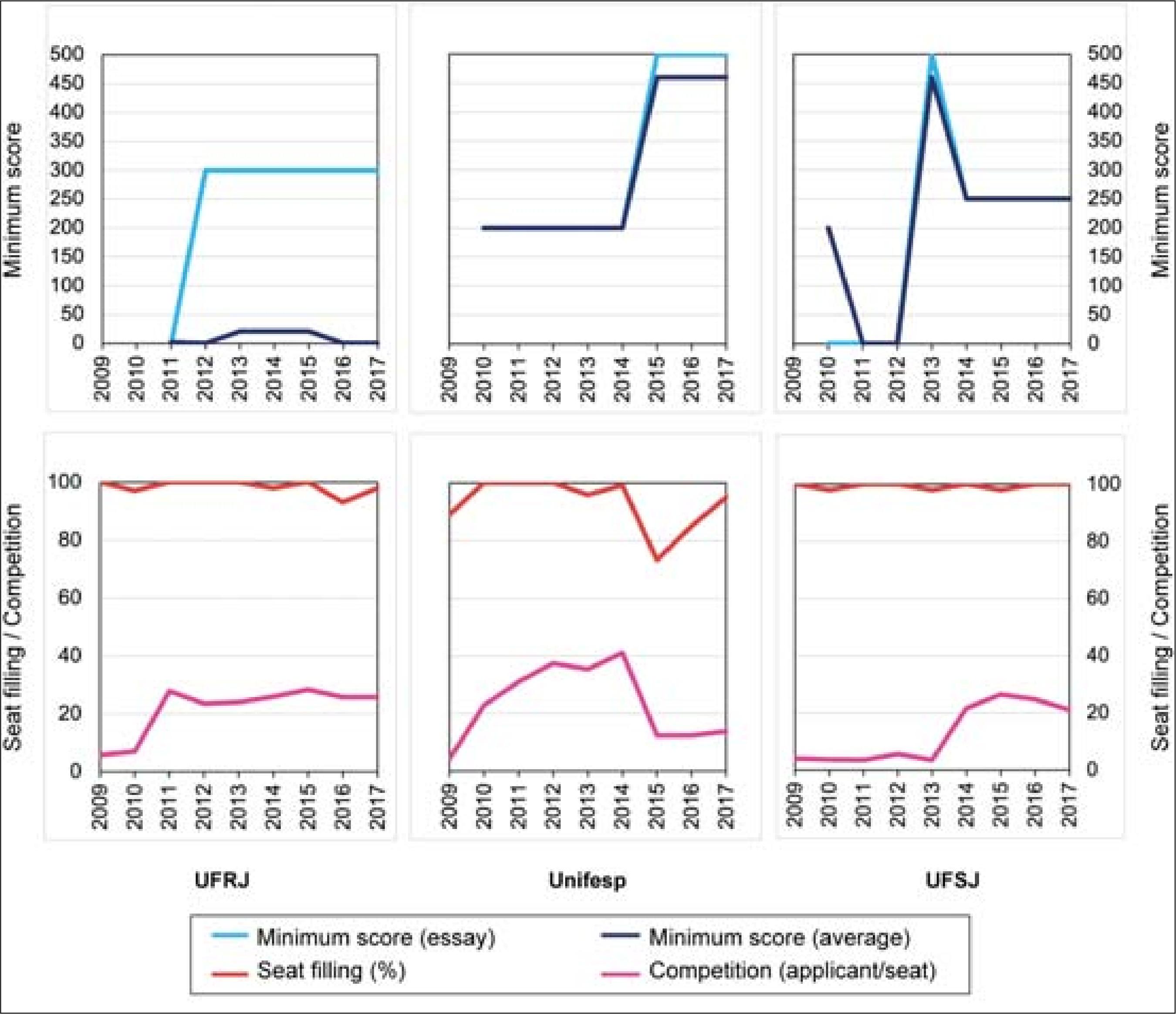

Figure 8 shows, in a more general picture, how variations in minimum admission scores impact the filling of new seats in Pedagogy courses at three Brazilian federal universities in the Southeast region. Considering the cases discussed above – in which we tried, as far as possible, to isolate some variables and effects – it is easier to identify situations in which increasing the minimum admission scores generates an additional effect on the production of vacant seats by disturbing the already intricate game mechanism associated with SiSU.

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the raw data from the 2009-2017 Brazilian Higher Education Census (Brasil, 2009) and the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

Figure 8 Minimum scores (average and essay), filling of new seats (%) and competition. SiSU, in-person Pedagogy courses, three Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

Comparing the numbers of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) with those of the Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei (UFSJ) (Figure 8), one has the impression that the variation of the minimum admission score in the investigated period does not affect the filling of new seats in these two institutions. Table 6, however, shows that UFSJ offered only 10% of its Pedagogy seats for admission via SiSU until 2013, raising this rate to 80% in 2014 and, finally, to 100% in 2016. In other words, the large variations in the minimum admission scores – which reached values above 400.00 in 2013 – had a very small effect on filling the course seats, of which only 10% were available to players on the SiSU board. Both UFRJ (since 2012) and UFSJ (since 2014) maintained minimum admission scores in the range of 250.00-300.00, which had little effect on filling seats.

Table 6 Seats offered (%) for admission via SiSU. In-person Pedagogy courses, three Brazilian Federal Universities, 2010-2017

| University | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFRJ | – | 60.0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Unifesp | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| UFSJ | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 80.0% | 80.0% | 100% | 100% |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

In general, the variation in admission parameters has a smaller impact on filling seats on campuses located in large cities, except when variations are very high. Consider the case of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp), which since 2010 has made available 100% of admissions for the Pedagogy course at the Guarulhos campus, located in the highly populated São Paulo metropolitan area. In 2015, the minimum admission scores were elevated from 200.00 to over 450.00. The direct consequence of this operation was a depletion in the number of filled seats (Figure 8). That year, of the 120 Pedagogy seats offered in Guarulhos – the second largest city in the state of São Paulo – only 88 were filled (73.3% of the total).

Concluding Remarks: the Dialectic of Expanding Access to Higher Education

Historically, the expansion of access to school education in Brazil, whether basic education – especially in the 20th century – or higher education – in the second half of the last century and in the first two decades of the 21st century –, has been accompanied by two movements that, safeguarding the specificities of each educational level, present similar elements: 1) expansion movements unaccompanied by the minimum conditions for the development of educational processes, producing a certain precariousness of the public supply; and 2) resistance movements to expansion when it is understood as a way of lowering the quality of teaching.

There is a large literature that analyzes the social struggles for basic education, for the process of expanding access to public schools and for the reconfiguration of education systems in Brazil (Sposito, 1992; Cunha, 1999; Beisiegel, 2006; Corti, 2015). In different ways, these authors discussed the importance of expanding access to basic education to the lower classes as a responsibility of the State, as well as analyzed forms and mechanisms of school exclusion. An example is the analysis by Azanha (1987, p. 112) on the unification of the admission exam in the state of São Paulo, which expanded access to secondary education, but provoked resistance from teachers: “[…] the great resistance to the policy of attendance expansion at the junior high school level took place within the secondary schools themselves”. When analyzing the reaction of teachers to the policy of unifying admission exams, the author considered that

Secondary school teachers did not understand that the massive enrollment of children in secondary school was a problem of educational policy, of democratization of education, in one of the only legitimate senses in which the term democratization of education can be used. I admit other meanings, but no democratization of education can be done for a few. No highly democratized teaching standard for a few represents a democratization policy for teaching

(Azanha, 1987, p. 113-114).

The author highlights two fundamental aspects to be considered when trying to democratize access to school education: 1) there is no democratization for a few; and 2) the pedagogical issues of the democratization of education must complement the political measure rather than oppose it. Despite the specificities of the problem investigated by Azanha, his analysis allows us to understand the expansion of access as the first and essential measure of a movement to democratize education. Nevertheless, one cannot lose sight of the contradictions of this democratization, which implies identifying the precariousness of the process of expanding access and the mechanisms of exclusion forged in the educational institutions themselves as reactions to the problem of “lowering the quality” of education.

In line with goal 12 of the PNE 2014-2024 and with the importance of universalizing Brazilian higher education according to international criteria – both with a view to realize the right to education and to expand national economic and social development –, it is important that all seats offered in undergraduate courses at public universities are filled. The demand exists.

We understand that the scores in university admission exams or in Enem, no matter how low they are, should not prevent admission to courses when there are available seats. Even if a low score is not desirable from a certain point of view, the objective of undergraduate courses is to train the students for the exercise of a profession, and this implies (as it has always implied, in fact) that HEIs must deal with possible deficiencies in the basic training of their students. If most of those who take the Enem annually perform below minimum standards, this is due to the poor quality of their training in basic education. The low performances are due, therefore, to problems that cannot be solved by elitist and arbitrary measures adopted by HEIs.

It is not new that corporate reformers of basic education advocate raising the cut-off scores for admission to teacher training courses as a way of improving the quality of basic education without substantially altering the working conditions in schools or valuing teachers’ salaries and careers8. Such an operation, far from modifying stratification patterns that concentrate people from the lower classes in less prestigious courses – such as teacher training courses (Carvalhaes; Ribeiro, 2019) –, hinder access to public higher education, as we have seen in the various cases of universities that promoted changes in their admission parameters without reflecting on their respective impacts on filling the seats offered.

If the argument of low proficiency indicators in large-scale assessments serves to denounce the deficit in the quality of public basic education – and thereby to justify the adoption of curricular centralization policies such as the Brazilian Curricular Common Core (BNCC) and the High School Reform (Cássio, 2019; Cássio; Goulart, 2022) – why would the performance of these same students in the Enem serve to exclude them from public higher education, given that in many universities, as we have shown for Pedagogy courses, there are classes with vacant seats?9 It is, above all, a matter of efficiency of public institutions.

Although we do not advocate that students enter the university without any conditions to attend this level of education, we draw attention to the fact that it is necessary to improve the quality of basic education at the same time that the BFHEIs must adopt measures that make it possible to fill in all their available seats, and to develop, when applicable, processes so that less prepared students can take full advantage of the undergraduate courses. The score required for admission to undergraduate courses, if it somehow informs what an applicant was able to answer in the admission test, it is not an absolute indicator of that applicant’s likelihood of having a good academic performance in the course, and even less about his/her possibility of becoming a good professional in technical and ethical terms.

A study carried out by the Dean of Graduation at Unifesp, with the objective of analyzing possible differences between the Grade Point Averages (GPA) of students admitted in the institution through the quota system and of those admitted via regular competition, as well as the relationship between performance in the admission exam and academic performance, indicated that on the Guarulhos campus, where the Pedagogy course is located, there was no statistically relevant correlation between GPA and the classification in the admission exam in the period between 2009 and 2012.

The correlation coefficient between GPA and the classification in the admission exam (from the first to the last one classified) for all students entering in 2012, at the Guarulhos campus, was – 0.11. It can be observed [...] that there is no association between the two variables, that is, the student’s academic performance is not related to his/her performance in the admission exam

(Unifesp, 2013, p. 14).

Despite the limitations of the study in terms of the period investigated and of comprising a single institution, it indicates that performance in the processes for admission to higher education should not be taken as a measure capable of indicating which students will be able to complete an undergraduate course. Due to the great demand, many of those who are unable to enter their chosen undergraduate course, especially in the most competitive ones, would probably be able to advance in the course with adequate performance and, once they graduate, to practice the chosen profession. Paradoxically, the same Unifesp that produced studies to inform its admission processes and to assess the impacts of its student permanence policies (Cespedes et al., 2021), also promoted abrupt variations in admission parameters that excluded people from public higher education. In the 2022 admission process, Unifesp kept the minimum score for the essay at 500.00, but from 2019 onwards it reduced the minimum scores for the other Enem areas (keeping the minimum average at 450.00).

If admission processes in Brazilian public higher education institutions exist due to the limitation of the available seats, they should never exist as mechanisms to prohibit the admission of those who, for different reasons, are unable to achieve the required scores. In this sense, this research, like others that have already investigated the national and regional impacts of SiSU, can help public higher education institutions to qualify their internal discussions and to establish admission criteria that lead to the filling of all their available seats.

Notes

1São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, Rio Grande do Sul, Paraná and Bahia, in decreasing order of state GDP (Silveira; Barbosa; Silva, 2015, p. 1101-1102).

2The PNE 2014-2024 established in its goal 12 that, during the Plan’s validity period, the country should “[…] raise the gross enrollment rate in Higher Education to 50% and the net rate to 33% of the population aged 18 to 24, ensuring the quality of the offer and expansion to at least 40% of new enrollments in the public segment”. A study by the Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (Inep) indicates that the gross enrollment rate in Brazil grew by 6.2% between 2012 and 2019, with a growth of 12.6% required by 2024 to meet goal 12 of the PNE. With a growth of 5.4% between 2012 and 2019, the net education rate needs to grow 7.5% to achieve the 33% target in net enrollment rate in higher education by 2024. The participation of the public segment in the expansion of enrollments was 9.9 % between 2012 and 2019, which is far from the 40% target established in the PNE (Brasil, 2020).

3 Lima and Machado (2014) analyze the problem of student dropout in undergraduate courses and point to aspects that transcend higher education policies themselves.

4 Sousa (2016) points out that several BFHEIs have implemented bonus mechanisms for local applicants, with the aim to combating the potentially perverse effects of geographic mobility; that is, that only privileged students from other regions would have access to the seats offered, harming the institutions’ mission of impacting higher education at the regional level.

5The annual raw data from the Brazilian Higher Education Census can be found at Brasil (2009).

6“0.01” and “1.00” are scores commonly adopted by the BFHEIs in SiSU, as can be seen in the contracts of adhesion analyzed in this study.

7Although the decrease seems mild, of the 7,260 seats offered at the Brazilian federal universities investigated in 2015, 647 seats remained vacant (8.9% of the total).

8See, as an example, the elitist position of Priscila Cruz, executive president of the corporate coalition Todos pela Educação, which evokes art. 62 (§ 6) of the Brazilian Education Law (LDB, Law No. 9,394/1996) to defend the increase in the minimum scores for admission into teacher training courses: “[…] 20% of students who enter Pedagogy and teaching courses have a score between 450 and 500 in the Enem, they could not even have a high school diploma. What is coming [this new wave of professionals] discourages me” (Passarelli, 2019).

9In addition to various mechanisms for filling seats in the period immediately after SiSU (Sousa, 2016, p. 69-70), with a view to correcting distortions in the admission system, many Brazilian federal universities publish internal or external transfer public notices throughout the year to reduce the number of vacant seats in their undergraduate courses. While serving to mitigate the problem of wasted resources, the reinforcement of university endogeny also implies a ban on access to people who are outside the public higher education system.

REFERENCES

ABREU, Luis; CARVALHO, José Raimundo. Análise do Jogo induzido pelo Mecanismo SiSU de Alocação de Estudantes em Universidades. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE ECONOMIA, 42., 2016, Niterói. Anais […]. Niterói: ANPEC, 2016. Disponível em: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:anp:en2014:125. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

ARIOVALDO, Thainara Cristina de Castro; NOGUEIRA, Cláudio Marques Martins. O SiSU e a Escolha pelas Licenciaturas da Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, São Paulo, v. 32, e06763, p. 1-26, 2021. [ Links ]

AZANHA, José Mario Pires. Educação: alguns escritos. São Paulo: Editora Nacional, 1987. [ Links ]

BACKES, Danieli Artuzi Pes. Análise sobre a Influência do Sistema de Seleção Unificada (SiSU) na Evasão do Curso de Administração da Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso. Revista de Administração do Sul do Pará, Redenção, FESAR, v. 2, n. 1, p. 79-105, 2015. [ Links ]

BARROS, Aparecida da Silva Xavier. Vestibular e Enem: um debate contemporâneo. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 22, n. 85, p. 1057-1090, 2014. [ Links ]

BEISIEGEL, Celso de Rui. A Qualidade do Ensino na Escola Pública. Brasília: Liber Livro, 2005. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Portaria Normativa nº 2, de 26 de janeiro de 2010. Institui e regulamenta o Sistema de Seleção Unificada, sistema informatizado gerenciado pelo Ministério da Educação, para seleção de candidatos a vagas em cursos de graduação disponibilizadas pelas instituições públicas de educação superior dele participantes. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, n. 18, 26 jan. 2010. [ Links ]

BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Relatório do 3º Ciclo de monitoramento das Metas do Plano Nacional de Educação – 2020. Brasília: INEP, 2020. Disponível em: https://download.inep.gov.br/publicacoes/institucionais/plano_nacional_de_educacao/relatorio_do_terceiro_ciclo_de_monitoramento_das_metas_do_plano_nacional_de_educacao.pdf. Acesso em: 23 dez. 2021. [ Links ]

CABELLO, Andrea et al. Formas de Ingresso em perspectiva Comparada: por que o SiSU aumenta a evasão? O caso da UnB. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior, Campinas, Sorocaba, v. 26, n. 2, p. 446-460, 2021. [ Links ]

CARVALHAES, Flavio; RIBEIRO, Carlos Antônio Costa. Estratificação Horizontal da Educação Superior no Brasil: desigualdades de classe, gênero e raça em um contexto de expansão educacional. Tempo Social, São Paulo, v. 31, n. 1, p. 195-233, 2019. [ Links ]

CÁSSIO, Fernando. Existe Vida fora da BNCC? In: CÁSSIO, Fernando; CATELLI JR., Roberto (Org.). Educação é a Base? 23 educadores discutem a BNCC. São Paulo: Ação Educativa, 2019. P. 13-39. [ Links ]

CÁSSIO, Fernando; GOULART, Débora Cristina. A Implantação do Novo Ensino Médio nos Estados: das promessas da reforma ao ensino médio nem-nem. Retratos da Escola, Brasília, v. 16, n. 35, p. 285-293, 2022. [ Links ]

CESPEDES, Juliana Garcia et al. Avaliação de Impacto do Programa de Permanência Estudantil da Universidade Federal de São Paulo. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 29, n. 113, p. 1067-1091, 2021. [ Links ]

COIMBRA, Camila Lima; SILVA, Leonardo Barbosa e; COSTA, Natália Cristina Dreossi. A Evasão na Educação Superior: definições e trajetórias. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 47, e228764, p. 1-19, 2021. [ Links ]

CORTI, Ana Paula de Oliveira. À Deriva: um estudo sobre a expansão do Ensino Médio no Estado de São Paulo (1991-2003). 2015. 300 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Educação, São Paulo, 2015. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Luiz Antonio. Educação, Estado e Democracia no Brasil. São Paulo, Niterói, Brasília: Cortez; EdUFF; Flacso, 1999. [ Links ]

CZERNIASKI, Lizandra Felippi. Políticas Públicas de Democratização do Ensino Superior: um estudo sobre a ocupação das vagas nos cursos de graduação na Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná – câmpus Francisco Beltrão. 2014. 111 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Políticas Públicas) – Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, 2014. [ Links ]

FLORES, Cezar Augusto da Silva. A Escolha do Curso Superior no Sistema de Seleção Unificada – SiSU: o caso do curso de Enfermagem da Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Campus Universitário de Sinop. 2013. 206 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Instituto de Educação, Cuiabá, 2013. [ Links ]

GILIOLI, Renato de Sousa Porto. Evasão em Instituições Federais de Ensino Superior no Brasil: expansão da rede, SiSU e desafios. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados, Consultoria Legislativa, 2016. (Estudo Técnico). Disponível em: https://bd.camara.leg.br/bd/handle/bdcamara/28239. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

LIMA, Edileusa; MACHADO, Lucília. A Evasão Discente nos Cursos de Licenciatura da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Educação Unisinos, São Leopoldo, v. 18, n. 2, p. 121-129, 2014. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, Cláudio Marques Martins et al. Promessas e Limites: o SiSU e sua implementação na Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 33, n. 2, p. 61-90, 2017. [ Links ]

PASSARELLI, Hugo. ‘Farra do ensino a distância em pedagogia preocupa’. Valor Econômico, São Paulo, 2 out. 2019. Disponível em: https://valor.globo.com/brasil/noticia/2019/10/02/farra-do-ensino-a-distancia-em-pedagogia-preocupa.ghtml. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

ROSA, Chaiane de Medeiros; SANTOS, Fabiano Fortunato Teixeira dos. Vagas Ociosas na Educação Superior Brasileira: limites e contradições das políticas de expansão e democratização do acesso. Quaestio, Sorocaba, v. 23, n. 2, p. 503-521, 2021. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, Fernando Lang da; BARBOSA, Marcia Cristina Bernardes; SILVA, Roberto da. Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (Enem): uma análise crítica. Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física, São Paulo, v. 37, n. 1, p. 1101-1105, 2015. [ Links ]

SOUSA, Marcela Regina Porta de. O Sistema de Seleção Unificada e o Preenchimento de Vagas na Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados. 2016. 97 f. Dissertação (Mestrado Profissional em Administração Pública em Rede Nacional) – Faculdade de Administração, Ciências Contábeis e Economia, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados, Dourados, 2016. [ Links ]

SPOSITO, Marília de Pontes. O Povo vai à Escola: a luta popular pela expansão do ensino público em São Paulo. São Paulo: Loyola, 1992. [ Links ]

TRAVITZKI, Rodrigo. Possíveis Contribuições do Enem para a Democratização do Acesso à Educação Superior no Brasil. Em Aberto, Brasília, v. 34, n. 112, p. 143-157, 2021. [ Links ]

UFAL. Universidade Federal de Alagoas. Resolução CONSUNI/UFAL n. 22, de 04 de maio de 2015. Estabelece o critério de inclusão regional de acesso aos candidatos dos cursos de graduação ofertados nos campi universitários da UFAL no interior do estado de Alagoas. Maceió: SECS, 4 maio 2015. Disponível em: https://ufal.br/resolucoes/2015/resolucao-no-22-2015-de-04-05-2015-1/resolucao-no-22-2015-de-04-05-2015. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

UNIFESP. Universidade Federal de São Paulo. Análise do Coeficiente de Rendimento dos estudantes da Unifesp. São Paulo: Prograd/Unifesp, 2013. Disponível em: www.unifesp.br/reitoria/prograd/pro-reitoria-de-graduacao/informacoes-institucionais/graduacao-em-numeros?download=454:analise-coeficiente-rendimento. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

VELOSO, Valquiria da Rocha Santos et al. Ocupação de Vagas Disponíveis nos Cursos de Graduação da Universidade Federal de Goiás de 2006 a 2013. In: COSTA, António Pedro et al. (Ed.). Livro de Atasdo “3º Congresso Ibero-Americano em Investigação Qualitativa”. Badajós: CIAIQ, 2015. P. 277-280. (Volume 1: Artigos de Educação). Disponível em: https://proceedings.ciaiq.org/index.php/CIAIQ/article/view/381/378. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

Annex

Table 7 Cumulative variation of the minimum admission score (essay and average of four knowledge areas). In-person Pedagogy courses, Brazilian Federal Universities, 2009-2017

| BFHEI | Variation (Average) |

Variation (Essay) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Universidade Federal do Pará | UFPA | + 420.00 | + 499.99 |

| Universidade Federal de Sergipe | UFS | + 400.00 | + 399.99 |

| Universidade Federal de Santa Maria | UFSM | + 300.00 | + 299.99 |

| Universidade Federal de São Paulo | Unifesp | + 260.00 | + 300.00 |

| Universidade Federal do Acre | UFAC | + 179.99 | + 100.00 |

| Universidade Federal Fluminense | UFF | + 164.00 | + 139.99 |

| Fundação Universidade Federal do Pampa | Unipampa | + 83.33 | + 83.33 |

| Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro | UFRJ | + 60.00 | + 299.99 |

| Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro | UFRRJ | + 50.00 | + 50.00 |

| Fundação Universidade Federal do Tocantins | UFT | + 46.00 | + 270.00 |

| Universidade Federal de Alfenas | Unifal-MG | + 30.00 | + 150.00 |

| Universidade Federal de São Joao del-Rei | UFSJ | + 16.67 | + 83.33 |

| Universidade Federal do Rio Grande | FURG | + 6.40 | + 50.00 |

| Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte | UFRN | + 5.00 | + 25.00 |

| Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina | UFSC | + 4.39 | 0 |

| Universidade Federal do Piauí | UFPI | + 3.20 | + 4.00 |

| Universidade Federal do Amazonas | UFAM | + 0.01 | + 0.01 |

| Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro | Unirio | + 0.01 | + 0.01 |

| Universidade Federal do Maranhão | UFMA | + 0.01 | + 0.01 |

| Universidade Federal do Paraná | UFPR | + 0.01 | 0 |

| Universidade Federal de Roraima | UFRR | – 0.67 | – 3.33 |

| Universidade Federal de Goiás | UFG | – 11.99 | – 60.00 |

| Fundação Universidade Federal de Rondônia | UNIR | – 25.00 | – 25.00 |

| Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul | UFMS | – 26.32 | – 26.31 |

| Fundação Universidade Federal de Viçosa | UFV | – 40.00 | – 199.99 |

| Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo | UFES | – 40.00 | – 199.99 |

| Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco | UFPE | – 60.00 | – 100.00 |

| Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará | Unifesspa | – 170.00 | – 50.00 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by the BFHEIs.

BFHEIs with in-person Pedagogy courses without variation of the minimum admission score in the period: Universidade de Brasília (UnB), Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul (UFFS), Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD), Universidade Federal da Paraíba (UFPB), Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL), Universidade Federal de Campina Grande (UFCG), Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF), Universidade Federal de Lavras (UFLA), Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso (UFMT), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto (UFOP), Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPel), Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (UFU), Universidade Federal do Amapá (Unifap), Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC), Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) and Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri (UFVJM)

BFHEIs with in-person Pedagogy courses that were created or that joined SiSU after 2017: Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira (Unilab), course created in 2017 (it did not participate in SiSU that year); Universidade Federal do Cariri (UFCA), course created in 2020; Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia (UFRA), course created in 2018; Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido (Ufersa), course created in 2017 (did not participate in SiSU that year).

BFHEIs with in-person Pedagogy courses and their own admission process throughout the period investigated: Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará (UFOPA).

BFHEIs with Pedagogy courses exclusively in distance education: Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM) and Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco (Univasf).

BFHEIs without Pedagogy courses: Fundação Universidade Federal do ABC (UFABC), Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana (Unila), Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), Universidade Federal de Itajubá (Unifei), Universidade Federal do Oeste da Bahia (UFOB), Universidade Federal do Sul da Bahia (UFSB) and Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (UTFPR).

Table 8 Weights and minimum scores for admission via SiSU. In-person Pedagogy courses, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, 2011-2017

| ESSAY | MATH | LANGUAGES | HUMAN SCIENCES | NATURE SCIENCES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight | |

| UFMS Aquidauana | ||||||||||

| 2011 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2012 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2013-2016 | 300.00 | 2 | 350.00 | 1 | 350.00 | 2 | 300.00 | 2 | 300.00 | 1 |

| 2017 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 |

| UFMS Campo Grande | ||||||||||

| 2011 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2012-2014 | 200.00 | 3 | 200.00 | 2 | 200.00 | 3 | 200.00 | 2 | 200.00 | 1 |

| 2015-2016 | 350.00 | 4 | 350.00 | 3 | 350.00 | 3 | 350.00 | 3 | 350.00 | 3 |

| 2017 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.01 | 3 | 0.01 | 3 | 0.01 | 3 |

| UFMS Corumbá | ||||||||||

| 2011 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2012-2013 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2014-2016 | 500.00 | 2 | 450.00 | 1 | 450.00 | 2 | 450.00 | 2 | 450.00 | 1 |

| 2017 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 |

| UFMS Naviraí | ||||||||||

| 2011 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2012 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2013-2015 | 350.00 | 2 | 322.00 | 1 | 302.00 | 2 | 253.00 | 2 | 265.00 | 1 |

| 2016 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 |

| 2017 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 |

| UFMS Ponta Porã | ||||||||||

| 2014 | 300.00 | 2 | 300.00 | 2 | 300.00 | 2 | 300.00 | 1 | 300.00 | 1 |

| 2015 | 300.00 | 3 | 300.00 | 1 | 300.00 | 3 | 300.00 | 3 | 300.00 | 1 |

| 2016 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 |

| 2017 | 0.01 | 3 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 3 | 0.01 | 3 | 0.01 | 1 |

| UFMS Três Lagoas | ||||||||||

| 2011-2012 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2013 | 500.00 | 3 | 321.60 | 1 | 301.20 | 2 | 252.60 | 2 | 265.00 | 1 |

| 2014 | 550.00 | 2 | 450.00 | 1 | 500.00 | 1 | 550.00 | 1 | 450.00 | 1 |

| 2015-2016 | 150.00 | 3 | 150.00 | 1 | 150.00 | 2 | 150.00 | 2 | 150.00 | 1 |

| 2017 | 0.01 | 3 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by UFMS.

Table 9 Weights and minimum scores for admission via SiSU. In-person Pedagogy courses, Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2011-2017

| ESSAY | MATH | LANGUAGES | HUMAN SCIENCES | NATURE SCIENCES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight |

minimum score |

weight | |

| UFF Angra dos Reis | ||||||||||

| 2011-2013 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2014 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2016-2017 | 100.00 | 1 | 250.00 | 1 | 250.00 | 1 | 250.00 | 2 | 250.00 | 1 |

| UFF Niterói | ||||||||||

| 2011-2015 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2016-2017 | 300.00 | 2 | 250.00 | 1 | 300.00 | 1 | 350.00 | 2 | 300.00 | 1 |

| UFF Santo Antonio de Pádua | ||||||||||

| 2011-2014 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015 | 400.00 | 3 | 368.00 | 1 | 387.00 | 2 | 417.00 | 3 | 378.00 | 1 |

| 2016 | 200.00 | 2 | 290.00 | 1 | 250.00 | 2 | 300.00 | 2 | 290.00 | 1 |

| 2017 | 300.00 | 3 | 250.00 | 1 | 300.00 | 3 | 300.00 | 2 | 290.00 | 1 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the admission rules provided by UFF.

Received: May 06, 2022; Accepted: September 23, 2022

text in

text in