Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educação e Realidade

Print version ISSN 0100-3143On-line version ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.48 Porto Alegre 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236124563vs01

OTHER THEMES

The Voice of Students of an Education Action Zone School

IInstituto Politécnico de Lisboa (IPL), Escola Superior de Educação de Lisboa (ESELx), Lisboa – Portugal

This study sought to give voice to the students of a Education Action Zone (EAZ) school about the processes of participation and the factors that hinder or promote their learning. Through this participation, students have the opportunity to express their opinions, a fundamental process for improving the pedagogical process. Following a mixed methodology, this work aimed at applying a questionnaire per class (33 classes) and carrying out 5 focus groups in which 34 class delegates participated. The participation of students in school life seems to be, mostly, at a simple level, since students only follow indications and respond to stimuli. The difficulties felt in the learning process, on the other hand, seem to result from internal characteristics of the student and his/her family environment, but also from external factors, related to the teaching processes and curriculum management.

Keywords Education Action Zone (EAZ); Children’s Participation; Teaching; Learning

Este estudo procurou dar voz aos/às alunos/as de um agrupamento de escolas abrangidas pelo Programa Territórios Educativos de Intervenção Prioritária (TEIP) sobre os processos de participação vivenciados e sobre os fatores que dificultam ou promovem as suas aprendizagens. Através desta participação, os/as alunos/as têm a possibilidade de exprimirem as suas opiniões, processo fundamental para a melhoria do processo pedagógico. Seguindo uma metodologia de caráter misto, este trabalho visou a aplicação de um questionário por turma (33 turmas) e a realização de 5 focus group em que participaram 34 delegados/as de turma. A participação dos/as alunos/as na vida escolar parece ser, maioritariamente, de nível simples, uma vez que os/as alunos/as apenas seguem indicações e respondem a estímulos. Já as dificuldades sentidas no processo de aprendizagem parecem resultar de caraterísticas internas ao/à próprio/a aluno/a e ao seu ambiente familiar, mas também a fatores externos, relativos aos processos de ensino e à gestão do currículo.

Palavras-chave Programa Territórios Educativos de Intervenção Prioritá- ria (TEIP); Participação das Crianças; Ensino; Aprendizagem

Introduction

The Educational Territories of Priority Intervention Programme (TEIP) is a government initiative in Portugal that aims to prevent and reduce early school leaving and absenteeism, reduce indiscipline, and promote educational success for all students. Currently, the programme is implemented in 136 school groupings or non-grouped schools located in economically and socially disadvantaged areas.

As part of the programme, schools must develop and implement an improvement plan (Portugal, 2012b) that addresses the needs of all students. To achieve this, a diagnosis of the main problems and priority intervention areas is essential.

Student participation in the school environment and the teaching and learning process is critical for improving the pedagogical process (Amorim; Azevedo, 2017; Freire, 1996; Portugal, 2021) and for promoting democratic practices as mentioned in the Basic Law of the Portuguese Educational System (Portugal, 1986).

Therefore, this study aimed to give a voice to the students in a school cluster integrated into the TEIP programme by administering a questionnaire and holding a focus group to understand their perceptions of participation processes and the factors that hinder or promote their learning. This goal is particulary relevante because the voice of students is rarely heard within the processes of self-assessment and development of TEIP school improvement plans (Canário; Alves; Rolo, 2000; Tomás; Gama, 2011; 2014). The problematization of issues related to participation and learning is essential in any school, but it gains even more relevance in these territories given their unique challenges. Understanding the conditions that promote or hinder participation and learning, according to the students, will be a vital contribution to renewing organizational and didactic-pedagogical practices and ultimately promoting school success. Studies like this will help to ensure that the voices of students are heard, and their experiences are taken into account in the development of effective educational policies and programmes.

The article is divided into five sections. The first section defines child participation and the different types of participation. The second section provides context on the TEIP 3 programme and our role in monitoring the improvement plan. The third section describes the methodology used in the study. The fourth section presents the data analysis and discussion. Finally, the fifth section offers some concluding remarks.

What is Participation?

The concept of participation, like many other concepts, has a variety of definitions and uses. Etymologically, participation originates from the Latin word participatio, -onis, which means “1. an act or effect of participating; 2. notice, part, communication” (Política, 2022). It is clear from these two definitions that participation involves an action that affects the person participating and that taking part and communication are essential to this process.

In addition to having multiple meanings, the term participation is often associated with other concepts, such as democracy and citizenship, which highlights its inherent complexity.

According to Paulo Freire, democratic learning and the democratization of democracy are only possible through the practice of critical and citizen participation (Freire, 1994). As a proponent of a participatory democracy that is inevitably social and cultural, Freire sees the democratization of public schools as a crucial element of change. For this author, participation is not only an end goal of education but also an element of educational practice because “only by deciding can one learn to decide, and only by deciding can one achieve autonomy” (Freire, 1996, p. 119).

Roger Hart (1993) argues that participation is a fundamental right of citizenship and how democracy is built and evaluated. It includes all processes in which decisions are made that affect the lives of individuals and communities.

Trilla and Novella (2001, p. 141) suggest that participating can mean “being present, making decisions, being informed about something, giving opinions, managing and executing; from simply being nominated, or being a member of, to being involved in something body and soul.” These authors view participation as having different forms, types, degrees, levels, and scopes.

The participation ladder (Hart, 1993) is a well-known model for reflecting on children’s participation. In this ladder, the first three rungs correspond to situations of non-participation or apparent participation, and the remaining five rungs correspond to different types of genuine participation.

Trilla and Novella (2001) present a new typology, composed of four major types of participation, that are qualitatively and phenomenologically different: simple participation, consultative participation, projective participation, and meta participation. Simple participation occurs when subjects only follow indications and respond to stimuli. Consultative participation involves listening to the subjects. In projective participation, the subject is not limited to being the recipient of an action but becomes an agent. The last type, meta participation, arises when subjects ask for, demand, or generate new spaces and mechanisms for participation.

Harry Shier (2001) has developed a model called the paths of participation, which is also based on Hart’s proposal (1993) and is composed of five levels of participation: children are listened to, children are supported in expressing their opinions, children’s opinions are taken into account, children are involved in the decision-making process, and children share power and responsibility in decision-making. In each of the five levels of participation, three differentiated levels of engagement in the process of children’s empowerment are described: openness, opportunity, and obligation.

Other authors have in common that they consider the maximum level of participation to be “student researchers” and, in the levels immediately before that, students as co-investigators, as active participants and as data sources, respectively (Fielding, 2001; Fielding; Bragg, 2003). Later, Fielding (2011) augments and reorganises the previous categories by proposing six levels culminating in a new level called participatory democracy, in which adults and learners take on a shared commitment and responsibility for managing the common good.

The analysis of pupil participation can take into account, in addition to the intensity of participation, the purpose of pupil participation (Rada; López, 2012). Once again, it is interesting to note that various authors have proposed different classifications which essentially differ in the level of detail adopted. Fielding and Bragg (2003) propose only three objectives: the teaching and learning process, the school and the curriculum policy; and finally, the school organization and environment. According to Rada and López (2012), student participation can be aimed at improving educational organization and management, negotiating the school curriculum, changing physical and social aspects of the school, improving teachers, and intervening in the community. Trilla and Novella (2001) do not focus on objectives but start from the right to participation, from the need to fulfil three conditions: recognition of the right of children to participate; development of the necessary capacities to exercise this right; and the existence of adequate means and spaces for participation.

But do Portuguese public schools work towards ensuring these three conditions for children’s participation?

If we start from what is in force in the Basic Law of the Educational System1, more specifically in article 3 (Organisational Principles), the Portuguese educational system should:

To contribute to developing the democratic spirit and practice, through the adoption of participatory structures and processes in the definition of educational policy, in the administration and management of the school system and in the daily teaching experience, in which all those involved in the educational process are integrated, especially pupils, teachers and families

(Portugal, 1986, p. 3068).

It is in this sense that schools should create spaces and times that enable the participation of children in participatory structures and processes. Also, in the Pupil Statute (Portugal, 2012a), it is evident that students have the right to participate, through representatives elected by them, in the school bodies, in the creation and implementation of the educational project, and the preparation of regulations (paragraphs m and n of article 7). Furthermore, according to the same article, all students have the right to present criticisms and suggestions regarding the functioning of the school to the teachers and other administrative and management bodies of the school in matters that are of interest to them (paragraph o).

The Portuguese educational context also presents, at least from the perspective of curricular policies, a strong commitment and alignment with pedagogy for participation. Among the various policies and instruments that reflect this commitment, the Profile of the Students Leaving Compulsory Schooling (Martins et al., 2017) stands out. This document constitutes the guiding ideology of the whole curriculum and all the work to be carried out in each school, seeking to respond to the social and economic challenges of the current world and the development of 21st-century skills. The Portuguese curriculum also includes essential learning, as well as the assumption of school autonomy extended to the curricular plan and its flexibility. Moreover, the Citizenship and Development component was recently implemented in the curriculum, as an area of work present in the different educational and training offers, with a view to the exercise of active citizenship and democratic participation. Based on the legislation in force, schools should develop their strategy for citizenship education with a philosophy of autonomy and flexibility (Portugal, 2018).

However, several studies have pointed out that students’ participation in school life is mostly limited to simple participation (Tomás; Gama, 2011, 2014). They participate only as spectators of certain processes or activities, which is a very limited type of participation that does not allow children and young people to express themselves and exercise their right to effective participation in school life. Therefore, it is essential to consider not only power relations but also the struggle for equal rights since children and young people are the ones who have the least power and the most difficulty in exercising their rights (Hart, 1993).

The TEIP 3 Programme: the Improvement Plan and the External Expert

Since the 1990s, some educational policy measures have been created and implemented in Portugal to address the problems of school failure and dropout. The Educational Territories of Priority Intervention programme is one of these examples. Created in 1996 by the Normative Dispatch no. 147-B/ME/96, of 1st August (Portugal, 1996), this programme was reintroduced in 2006 for the schools/groupings of schools in the metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Porto and was extended to the entire national territory two years later. In this second generation of the programme, each TEIP school cluster, according to article 16 of the Normative Dispatch no. 55/2008, of 23rd October (Portugal, 2008), should have a multidisciplinary team that coordinates various interventions and enables network articulation. This team, composed of teachers, technicians, and community representatives, was also integrated with external experts who had functions of follow-up, monitoring, and evaluation of the educational project.

Inspired by similar programmes developed in France - Zones Educatives Priorities- and England - Education Action Zones - the programme is currently in its third generation, having been created by the Normative Order No. 20/2012 of 3rd October 2012 (Portugal, 2012b). This generation of the TEIP programme aims to improve the quality of learning, prevent and reduce early school leaving and absenteeism, create conditions that promote the transition from school to active life, and increase the articulation with partners in the educational territories of priority intervention.

To operationalize the programme objectives, and according to Article 3 of the Normative Order no. 20/2012, of 3rd October 2012 (Portugal, 2012b), schools must define and implement an Improvement Plan that includes a diverse set of measures and intervention actions in the school and community. In the preparation of this document, it is necessary to “consider the specific circumstances and interests of the community and contemplate the interventions of the various partners” (Portugal, 2012b, p. 33345). In this process, diagnosis is one of the crucial steps, since it is based on it that the potentialities and weaknesses of the context and the school are identified, which will then be the basis for the formulation of the objectives and actions of the plan. In the construction of this diagnosis, it is necessary to involve all the school and community players, including the students. However, they should have effective participation, not only in the identification of needs but also in the development of the improvement plan. However, over the several generations of the programme, some studies have shown that the participation of children and young people in TEIP schools is still low (Canário; Alves; Rolo, 2000; Gama; Tomás, 2011).

It is in the context of the work we developed with a TEIP school cluster as external experts, assuming the role of “critical friends” (MacBeath et al., 2005), and taking into account the assumptions mentioned above, that we decided to give voice to the students of the school cluster. Because, as Lodge (2005) argues, we consider that it is the students who have more authority to speak about their own experience at school.

Methodology

The main objectives of this study were: to characterise what the students from a TEIP grouping of schools in the municipality of Sintra think about their participation in school and the origin of teaching and learning difficulties; to collect suggestions from the students to improve their participation and the teaching and learning process.

Two data collection techniques were used. Firstly, a questionnaire primarily containing open-ended questions was applied to the 2nd and 3rd Cycle Basic Education (CEB) classes. The response rate was 91.6% (Table 1).

Table 1 Study Participants

| Grade | Nº classes | Nº of completed questionnaires | Nº de delegates in the focus group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 36 | 33 | 34 |

| Grade 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

| Grade 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Grade 7 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Grade 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Grade 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Subsequently, and with the aim of exploring the answers provided in the questionnaires, five focus groups were held with the class representatives, one for each year of schooling. In total, 34 delegates participated. The data collection took place at the end of the school year 2020/2021.

After transcription of the focus groups, categorical content analysis was performed (Bardin, 2004), using content analysis software. The ethical issues of the research were taken into account, namely the informed consent, and the coding of participants was done to ensure anonymity.

Results

In this section, the analysis and discussion of the results is structured along two axes. Firstly, we describe how the students’ perspective on their participation at school is described, and secondly, the students’ perspective on teaching and learning difficulties and the origin of these difficulties.

Students’ participation in school

Of the 33 classes that answered the questionnaire, 29 consider that they participate in school. However, the forms of participation described reveal a very superficial perspective of the concept of participation. For most of the classes, participation is equated with the mere presence of the students in the activities proposed by the teachers. The following example from a sixth-grade class illustrates this view: “We participate with interest in the different activities proposed by the teachers inside and outside the classroom”. Only four classes describe participation processes that already involve listening to the students, namely, the class assemblies and the completion of surveys within the Eco-Schools programme.

The great majority of the class representatives consider that the school does not listen to the students and reveal difficulties in giving examples of spaces and moments of listening during the school year in which they were interviewed. The Family Support Office, the meetings for the school’s participatory budget (aimed only at students of the 3rd cycle of basic education and an initiative of the Ministry of Education), some class assemblies, and the process developed by the “critical friends” are the few examples mentioned by the delegates.

Even among the delegates who gave a more positive assessment, all considered it necessary to improve the number and quality of the participation processes. The focus group analysis also revealed that the delegates were aware that it was not always easy to implement their suggestions:

Class representative - [...] sometimes they don’t listen to what we want, but sometimes what we want can’t always be. For example, there are things that people ask for that can’t be done because there isn’t enough money for that [...] I’ll give you an example, the students would like to have another goal in the field, but the school management says they can’t put it, because I think they don’t have money, and the students use it, but it’s the students’ fault for not having a goal. But the school in general could listen more

(FG, 8th grade).

Moreover, they are aware that some suggestions require time to be implemented and that sometimes changes are not visible and/or enjoyed by those who propose them. This is particularly evident in the speech of the Year 6 delegates reporting changes that took place in their school in 1º CEB when they were already attending the 2º CEB:

Class delegate - I only saw evolution, evolution after I left, that is, last year, now there is a park, they have already fenced the part of the flowerbeds, so that there aren’t so many accidents, so as not to damage the flowerbeds, they also changed the field, several evolutions on things that, when I was there I said I want this because I think it looks better at school

(FG, 6th grade).

To minimize the negative effect resulting from the time lag between suggestions and their implementation, the school delegates consider it important that the school invests in quick, transparent, and clarifying communication with the school community, as evidenced in the following excerpt: ‘The teachers or the management could give us the certainty that something we say or suggest is going to happen because many times we say we want this, and then we don’t know if it is really going to happen’ (FG, 6th grade).

The data also points to differences between delegates from the 2nd cycle and the 3rd cycle. The former consider that in the 1º CEB, the participation processes were more frequent and, consequently, consider that they have more say:

Class delegate - Since I was at the school down there, there have always been these meetings of class delegates, and sub-delegates, the teachers asked several times what we thought needed to change at the school, in the grouping, the teachers, the staff, the whole school.

Moderator - Do you mean when you were in primary school?

Class delegate - Yes, last year there were only two meetings, if I’m not mistaken

(FG, 6th grade).

It should be noted that the pandemic may have influenced these opinions, as the 2nd cycle delegates have not yet experienced a full school year in face-to-face mode. In contrast, the delegates from the 3rd cycle, particularly those who have been attending the school grouping for longer, cite several references to a positive evolution in student participation - “I have been studying here since the 5th grade and I believe it has evolved” (FG, 8th grade).

All the delegates appreciated the class assemblies as a valuable space for student participation. However, due to the pandemic, these assemblies were not held systematically in all classes, as was customary in previous years. According to a 6th-grade delegate, “[...] the school doesn’t have spaces or moments for students to participate. Last year we had a class with the DT, but now with the corona, we don’t.”

The class representatives believe that to improve the participation processes in the school, it is crucial to have meetings not only with the class directors but also with the management. Additionally, some classes suggest that the class assemblies should be resumed, but not limited to solving problems of the class. Instead, they should assume a more proactive role, and the creation of school events by the students is another proposal that was pointed out by some of those interviewed. In this case, their participation would involve them in the entire process of organizing these events, including decision-making. Finally, a different proposal concerns the Student and Family Support Office, which could have “more space and time” to listen to the students.

Student’s Perspective on Teaching and Learning Difficulties

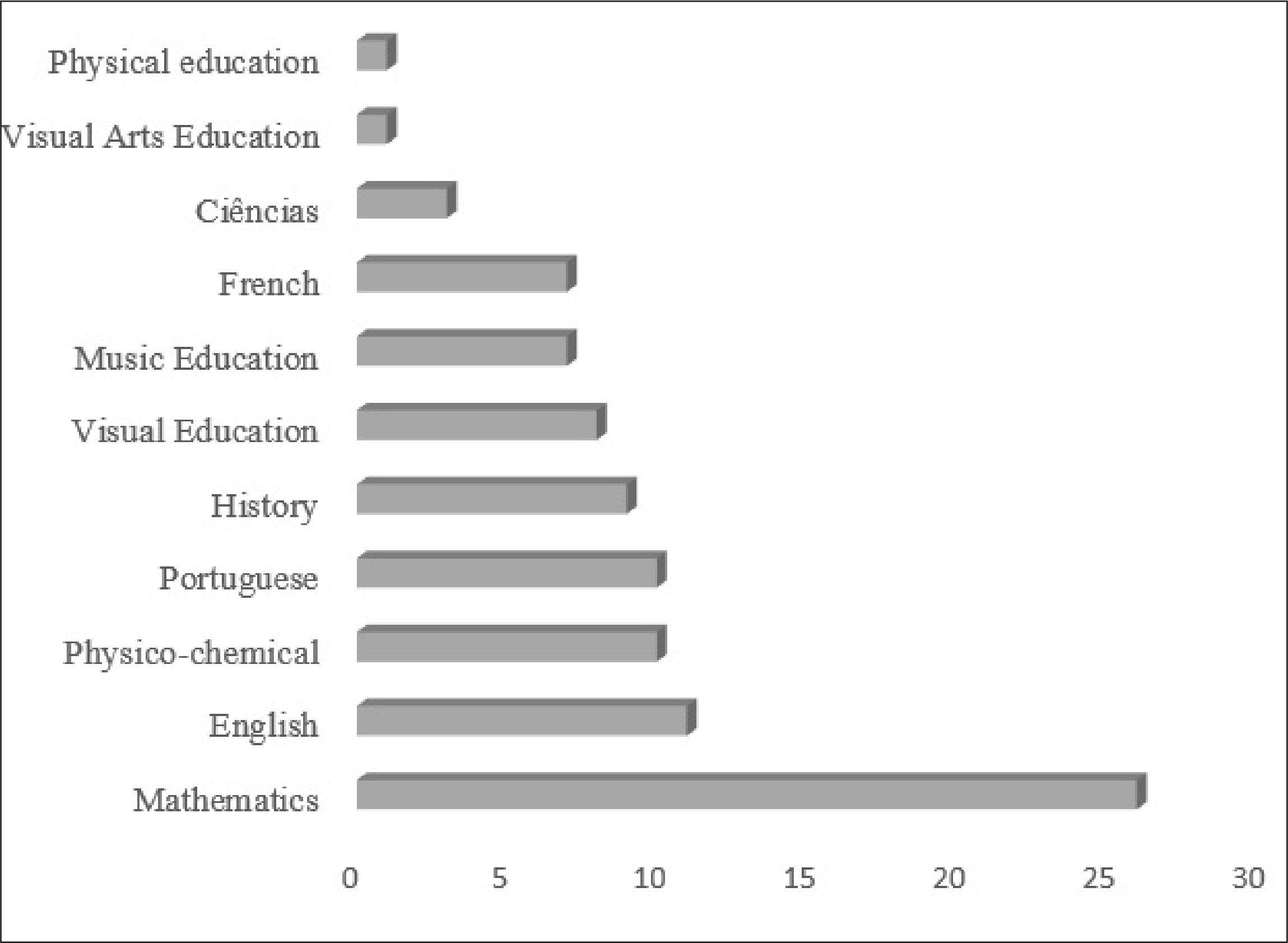

When asked about the subjects in which they felt the most difficulty, 26 classes indicated Mathematics, 11 English, and 10 Physical Chemistry and Portuguese Language (Figure 1).

In the interviews, class representatives cited various reasons to explain the difficulties their classmates experience in certain subjects. These reasons can be grouped into three categories: teaching processes, students’ characteristics, and organization/curricular management (Table 2).

Table 2 Categories and Sub-Categories Associated with Difficulties Felt in Some Subjects

| Categories | Sub-categories |

|---|---|

| Students’ Characteristics | Inappropriate behaviour |

| Lack of commitment and studying | |

| Learning difficulties | |

| Teaching processes | Non-identification with ways of teaching |

| Quality of the student-teacher relationship | |

| Behaviour management difficulties | |

| Curriculum organisation and management | Extensive programmes |

| Short lesson time | |

| Shortage of teachers | |

| Abstraction of some programmatic contents |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

The bad behaviour that some classes show and the fact that several students do not pay attention in class were the main learning difficulties associated with the dimension “characteristics of the students themselves”:

In my class the problem is not the teachers, they explain very well. The problem is the students [...] my class is very noisy and badly behaved and sometimes they don’t pay attention in class, they keep talking, they stay there with each other and rarely pay attention

(FG, 6th grade).

Moreover, the class representatives recognize that the difficulties also result from the students’ lack of commitment and motivation, since they do not always study regularly. According to a female class representative, her class “[...] gets a ‘No’ in almost every subject and it’s because of their lack of interest because they don’t study, or they study the day before or the day of” (FG, 6th grade).

There are also references to learning difficulties, usually associated with contents considered more abstract or that require unconsolidated previous knowledge. According to a class delegate “[...] the teachers usually say that we lack a lot of bases, we don’t have many bases in mathematics, so we have to go back there, and then come back as if we were going back to everything from the beginning” (FG, 9th grade). In the case of the Portuguese language, the difficulties are also attributed to the high number of students who do not have Portuguese nationality and/or do not communicate in Portuguese in their family environment:

We have the case of Portuguese, because my class has many students who have problems with the language because of the places we come from, in my class there are some foreigners and we have many difficulties in Portuguese

(FG, 8th grade).

The aspect most frequently mentioned in the scope of the teaching processes corresponded to the students’ non-identification with some teachers’ “ways of explaining”. For these students, the teaching is less effective when: the teaching strategies are not diversified; relationships between the contents and the students’ daily life are not established; spaces and times are not created for the clarification of doubts; and the lessons are essentially expository.

I had a maths teacher when he explained, he always explained with fruit, you have 5 bananas, but my teacher always explains in mathematical language and sometimes I don’t understand. For example, the value of π, she talks about π and I don’t understand. It’s far from my reality

(FG, 5th grade).

[...]

But the teacher sometimes doesn’t help either, it seems that she doesn’t teach the subject well, she is copying something and tells us not to copy it, that she’ll explain, and then she’ll give us time, but then when she finishes she starts erasing, you can’t copy anything, then we don’t understand the subject and she moves on to another one, then it gets very complicated

(FG, 5th grade).

The lack of empathy, the lack of motivation and the tiredness that some teachers show was another aspect mentioned, as this has consequences for the quality of the pedagogical relationship between students and teachers and, consequently, for learning.

As I said our class is difficult to deal with and the teacher can seem tired at times (FG, 8th grade).

(FG, 8th grade).

[...]

The teacher is professional, but showing more empathy towards students would be helpful. Our previous teacher would give serious lessons but also had moments of joking around, which helped us feel more connected to them

(FG, 8th grade).

Difficulties in managing classroom behaviour was also an issue mentioned by some delegates. To illustrate these difficulties, the class representatives either made comparisons between the behaviour of the same class with different teachers or described situations that deserved a more assertive attitude from the teacher.

In science class, I feel that sometimes it is a bit of the teacher’s fault. For example, the students make jokes with the teacher and behave badly, and the teacher literally does nothing. Obviously, a teacher who is always marking absences and picking on us is not good. But the science teacher is a good person, she explains well, but she doesn’t enforce proper discipline in class. So, many times, the lessons go very badly, and the teacher doesn’t even make a little occurrence

(FG, 6th grade).

[...]

With the CD [Class Director] class, they [my colleagues] all behave well, but when the HGP [Geography and History] class arrives, they seem to turn into other people. So, the teacher scolds them, and then they make a lot of noise, change places, and we lose a lot of class time

(FG, 5th grade).

With regard to the reasons associated with the dimension “curricular organisation and management”, the class representatives referred to a harmful triad, composed of the following factors: extensive programmes, too little lesson time and a lack of teachers.

My class has a lot of difficulties with maths. The maths programme is very big and the time is not enough. This year, for example, we don’t have a maths teacher, she is pregnant and they didn’t get us anyone

(FG, 8th grade).

In addition to this triad, there is the perception that in some subjects, mainly Mathematics and Physical Chemistry, the syllabus is difficult and abstract, as is evident in the following explanation of a 9th-grade delegate: “[...] in my class they chose Mathematics and Physical Chemistry, and I think it’s for the same reasons, the subject is a little more complex than in the other subjects” (FG, 9th grade).

When asked to give suggestions for the improvement of teaching and learning, the class representatives gave several. They consider that teachers should invest in more appealing resources and fewer theoretical lessons. The use of more PowerPoint, films, games, research, presentations by the students, outdoor classes and large group discussions were some of the examples mentioned:

Maybe, for example, we could play more games in mathematics. My teacher plays the game of 24 and it’s very fun - everyone participates. In science, our teacher passes PowerPoint presentations and sometimes we play games related to the topics we learn. In Portuguese, maybe we could play word games.

(FG, 5th grade)

[...]

I would like to do more experimental activities in class, both practical and theoretical because I think students pay more attention in practical classes than in theoretical ones. Also, there’s a teacher who allows us to ask questions during class with consultation materials, but in tests, we can’t use them. I think it would be fair to have the same rule in both situations

(FG, 7th grade).

Despite considering these strategies important, the interviewees repeatedly indicated that the most important thing was to improve the “ways of explaining”. To this end, it was fundamental for the teachers to explain the syllabus more calmly and with more examples from the real world.

In maths class we talk about money because it’s an everyday thing, it’s easier. Sora is doing the math and she was giving negative and positive numbers. She was giving the example with the lift because we have -1, -2, and this is very interesting because now I used to get confused with the lift, I didn’t know why -3 is here, is it down or up, but after the class with sora, I understood. Now I don’t have any difficulty with the lift. I find it very interesting to play games like this with our daily life, with our everyday life

(FG, 7th grade).

Finally, the regulation of the students’ behaviour, through the establishment of clear rules and their fulfilment, was also a recommendation aiming at the success of the teaching and learning process. According to a class delegate, if he were a teacher “[...] he would be more demanding, even because teachers who are less demanding end up just playing, the students end up playing a lot in those teachers’ classes (FG, 7th grade).

Final Considerations

This study aimed to understand the perceptions of students from a TEIP grouping regarding the participation processes experienced at school and the factors that hinder or promote their learning. The data obtained allows us to make some observations.

Firstly, it can be concluded that students’ participation in school life appears to be mostly at a simple level. The students have very superficial conceptions of the concept of participation itself and difficulty in giving examples of formal and informal spaces of participation in school life (Tomás; Gama, 2011; 2014).

Secondly, and as in other studies, the students show a high level of criticism regarding their evaluation of the teaching and learning process (Rudduck; McIntyre, 2007; Alves et al., 2014). The participants attribute internal causes to the students themselves and their family environment to explain their success or failure at school, but also external factors related to the teaching processes and the organization and management of the curriculum.

Inadequate behaviour, lack of commitment and study, and learning difficulties are the characteristics of the students that contribute to school failure. In several lessons and due to students’ bad behaviour, the classroom climate does not seem conducive to learning. The importance of the classroom climate in learning is also evident in the study developed by Alves et al. (2014) in TEIP schools. In turn, bad behaviour and lack of commitment and study seem to result from students’ attitudes and dispositions, but also from characteristics associated with the teachers and the methodologies adopted in the classroom.

The teaching processes include categories that are closely associated with the teacher’s effect, namely teaching methods, the type of pedagogical relationship that the teacher favours, and his/her ability to manage behaviour. This centrality assigned to the teacher’s effect, which was also identified in other studies (Marzano, 2005; Alves et al., 2014; Baptista; Alves, 2017), highlights the difference that, according to the students, this educational actor can play in improving learning.

The organization and management of the curriculum also play an important role in explaining learning difficulties. Here, the participants refer to a harmful triad that includes extensive programmes, too little class time, and a lack of teachers.

Although we have collected the students’ views, which suggest possible paths for a renewal of the organizational and didactic-pedagogical practices, we consider that this step is a necessary condition, but not sufficient for the development of a culture of effective participation and improvement of learning. In this way, and in order to continue the dialogue with the students, the data were presented to all the classes. To make their voices heard in the school structures, the data was also presented to the Pedagogical Council and the TEIP team. This sharing will feed the reflection on which are the best strategies to introduce in the improvement plan to be developed in the next school year. In this way, the plan will not be made for the students, but with the students, who will be seen as partners.

Note

REFERENCES

ALVES, José et al. A Aprendizagem em Territórios Educativos de Intervenção Prioritária: a visão dos alunos. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Educacional, Lisboa, n. 14, p. 173-208, 2014. [ Links ]

AMORIM, José; AZEVEDO, Joaquim. Lições dos Alunos: o futuro da educação antecipado por vozes de crianças e jovens. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Educacional, Lisboa, n. 17, p. 61-97, 2017. [ Links ]

BAPTISTA, Carla; ALVES, José. O Mal-Estar Discente numa Escola do Outro Século: olhares de alunos. Revista Portuguesa De Investigação Educacional, Lisboa, n. 17, p. 98-123, 2017. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2004. [ Links ]

CANÁRIO, Rui; ALVES, Natália; ROLO, Clara. Territórios Educativos de Intervenção Prioritária: entre a “igualdade de oportunidades” e a “luta contra a exclusão”. In: BETTENCOURT, Ana Maria et al. (Org.). Territórios Educativos de Intervenção Prioritária: construção ecológica da acção educativa. Lisboa: Instituto de Inovação Educacional, 2000. P. 139-170. [ Links ]

FIELDING, Michael. Students as Radical Agents of Change. Journal of Educational Change, New York, n. 2, p. 123-141, 2001. [ Links ]

FIELDING, Michael. La Voz del Alumnado y la Inclusión Educativa: una aproximación democrática radical para el aprendizaje intergeneracional. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Murcia, n. 70, p. 31-61, 2011. [ Links ]

FIELDING, Michael; BRAGG, Sara. Students as Researchers: making a difference. Cambridge: Pearson, 2003. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Cartas a Cristina. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1994. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

GAMA, Ana; TOMÁS, Catarina. Os TEIP e a Infância: desocultação das vozes das crianças no contexto educativo. In: CONGRESSO IBERO-BRASILEIRO DE POLÍTICA E ADMINISTRAÇÃO DA EDUCAÇÃO, 1., 2011, Elvas, Mérida e Cáceres. Atas […]. Lisboa: Fórum Português de Administração Educacional, 2011. [ Links ]

HART, Roger. Children’s Participation: from tokenism to citizenship. Florence: UNICEF, 1993. [ Links ]

LODGE, Caroline. From Hearing Voices to Engaging Dialogue: problematising student participation in school improvement. Journal of Educational Change, New York, v. 6, p. 125-146, 2005. [ Links ]

MACBEATH, John et al. A História de Serena: viajando rumo a uma escola melhor. Porto: Edições Asa, 2005. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Guilherme et al. Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação; Direção-Geral de Educação, 2017. [ Links ]

MARZANO, Robert. Como organizar as Escolas para o Sucesso Educativo: da investigação às práticas. Porto: Edições Asa, 2005. [ Links ]

POLÍTICA. In: Dicionário Priberam da Língua Portuguesa. Lisboa: Priberam Informática, 2022. Disponível em: https://dicionario.priberam.org/sobre.aspx. Acesso em: 15 set. 2022. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Ministério da Educação. Lei de Bases do Sistema Educativo nº 46/86, de 14 de outubro. Estabelece o quadro geral do Sistema Educativo Português. Diário da República: série I, Lisboa, n. 207, p. 3067-3081, 1986. Disponível em: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/46-1986-222418. Acesso em: 15 out. 2022. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Ministério da Educação. Despacho normativo nº 147-B/ME/96, de 1 de agosto. Definição de territórios educativos de intervenção prioritária. Define procedimentos a adotar pelas escolas integrantes dos referidos territórios, bem como as prioridades de desenvolvimento pedagógico do projeto educativo em causa. Diário da República: série II, Lisboa, n. 177, p. 10719, 1996. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Ministério da Educação. Gabinete da Ministra. Despacho normativo nº 55/2008, de 23 de outubro. Define as normas orientadoras para a constituição de territórios educativos de intervenção prioritária de segunda geração, bem como as regras de elaboração dos contratos -programa a outorgar entre os estabelecimentos de educação ou de ensino e o Ministério da Educação para a promoção e apoio ao desenvolvimento de projectos educativos que, neste contexto, visem a melhoria da qualidade educativa, a promoção do sucesso escolar, da transição para a vida activa, bem como a integração comunitária. Diário da República: série II, Lisboa, n. 206, p. 43128-43130, 2008. Disponível em: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/despacho-normativo/55-2008-3228943. Acesso em: 15 dez. 2021. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Assembleia da República. Lei nº 51/2012, de 5 de setembro. Aprova o Estatuto do Aluno e Ética Escolar. Diário da República: série I, Lisboa, n. 172, p. 5103-5119, 2012a. Disponível em: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/51-2012-174840. Acesso em: 15 out. 2022. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Gabinetes do Secretário de Estado do Ensino e da Administração Escolar e da Secretária de Estado do Ensino Básico e Secundário. Despacho normativo nº 20/2012, de 3 de outubro. Estabelece as condições para a promoção do sucesso educativo de todos os alunos e, em particular, das crianças e dos jovens que se encontram em territórios marcados pela pobreza e exclusão social. Diário da República: série II, Lisboa, n. 192, p. 33344-33346, 2012b. Disponível em: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/EPIPSE/despacho_normativo_20_2012.pdf. Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Presidência do Conselho de Ministros. Decreto-Lei nº 55/2018, de 6 de julho. Estabelece o currículo dos ensinos básico e secundário e os princípios orientadores da avaliação das aprendizagens. Diário da República: série I, Lisboa, n. 129, p. 2928-2943, 2018. Disponível em: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/55-2018-115652962. Acesso em: 15 out. 2022. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Recomendação nº 2/2021, de 14 de julho. Recomendação sobre “A voz das crianças e dos jovens na educação escolar”. Diário da República: série II, Lisboa, n. 153, p. 75-84, 2021. Disponível em: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/recomendacao/2-2021-167281062. Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

RADA, Teresa; LÓPEZ, Noelia. Voz del Alumnado y Presencia Participativa en la Vida Escolar. Apuntes para una cartografia de la voz del alumnado en la mejora educativa. Revista de Educación, Madrid, n. 359, p. 24-44, 2012. [ Links ]

RUDDUCK, Jean; MCINTYRE, Donald. Improving Learning through Consulting Pupils. New York: Routledge, 2007. [ Links ]

SHIER, Harry. Pathways to Participation: openings, opportunities and obligations. Children and Society, London, v. 15, n. 2, p. 107-111, 2001. [ Links ]

TOMÁS, Catarina; GAMA, Ana. Cultura de (não) Participação das Crianças em Contexto Escolar. In: ENCONTRO DE SOCIOLOGIA DA EDUCAÇÃO, 2., 2011, Porto. Atas [...]. Porto: Departamento Sociologia da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, 2011. P. 609-629. [ Links ]

TOMÁS, Catarina; GAMA, Ana. Entre Possibilidades e Constrangimentos: a participação das crianças na escola. In: CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL ENVOLVIMENTO DOS ALUNOS NA ESCOLA: PERSPETIVAS DA PSICOLOGIA E EDUCAÇÃO, 1., 2014, Lisboa. Atas [...]. Lisboa: Instituto de Educação da Universidade de Lisboa, 2014. P. 31-44. [ Links ]

TRILLA, Jaume; NOVELLA, Ana. Educación y Participación Social de la Infancia. Revista Iberoamericana De Educación, Madrid, v. 26, p. 137-164, 2001. [ Links ]

Received: May 16, 2022; Accepted: October 28, 2022

text in

text in