Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educação e Realidade

Print version ISSN 0100-3143On-line version ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.48 Porto Alegre 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236123295vs01

OTHER THEMES

Leadership as Learning: a studentfocused training approach

IUniversidad Católica Silva Henríquez (UCSH), Santiago – Chile

IIUniversidad Católica de Temuco (UCT), Temuco – Chile

IIIUniversidad de Extremadura (UEX), Badajoz – Spain

The purpose of this study is to describe the development process of a student-centered leadership training model to guide school management practices that foster both student and teacher learning. To design this model, a methodological participatory research process was undertaken, in which the reflection on practices and professional dialogue among teacher trainers and school leaders was rooted in the analysis and questioning of educational activities. In essence, the training of school leaders should evolve into a process of learning to learn alongside teachers about the challenges within their own practice, all while keeping in mind the comprehensive development and learning of the student.

Keywords Leadership; Apprenticeship; Learning Process; Education Development

El estudio tiene como propósito describir el proceso de elaboración de un modelo formativo de liderazgo centrado en el estudiante para orientar las prácticas de gestión escolar que promuevan el aprendizaje del alumnado y del profesorado. Para diseñar el modelo, se llevó a cabo un proceso metodológico de investigación participativa, donde la reflexión de la práctica y el diálogo profesional entre formadores de formadores y líderes escolares, se sitúa desde la indagación y cuestionamiento del quehacer educativo. En definitiva, la formación de líderes escolares debería transformarse en aprender a aprender junto al profesorado sobre los problemas de su propia práctica teniendo presente el aprendizaje y desarrollo integral del estudiante.

Palabras-clave Liderazgo; Aprendizaje Profesional; Proceso de Aprendizaje; Desarrollo de la Educación

Introduction

In recent decades1, countries have made various efforts to create and enhance a school leadership policy, primarily focusing on the role of those assuming leadership positions in educational institutions, developing their capabilities and delineating their knowledge, practices, and personal resources. However, it appears that these policies may not suffice to transform the core of their pedagogical duties due to their exclusive focus on professional knowledge associated with administrative roles, often neglecting the issues that impact classroom learning, which results in a disconnect between leadership and learning.

This weak connection between leadership policies and the educational purpose of schools is the outcome of a decision that focuses on problem-solving rather than on understanding the issues related to what, how, and why students learn. This situation demonstrates a lack of concern about the aim of student learning and their comprehensive development in schools. In light of this, in order to impact the learning of children, adolescents, and adults, there is a need for policies grounded in a shared vision of what is essential learning in schools in order to educate individuals who are capable of leading fulfilling lives and contributing to the development of society. Unfortunately, in the context of the current educational system, the majority of school institutions maintain an administrative/bureaucratic focus, emphasizing fulfilling duties and complying with regulations, which consumes the regular time of school administrators and classroom teachers. Accordingly, school leadership adopts a hierarchical logic of supervision mediated by external inspection associated with mandates that tend to prioritize control instead of leadership for learning. As a result, leadership remains associated with a formal position of authority or position, without recognizing that it involves both individual and collective practices of influence.

This form of exercising leadership from a vertical perspective is reflected in hierarchical decisions that depersonalize the meaning of educational work, potentially impacting professional commitment and responsibilities. Moreover, in the quest to address this verticalized approach, practices emerge that are based on the delegation of duties, representing a misguided view of distributed leadership and failing to recognize the need to challenge the naturalness with which hierarchies and task organization are assumed in educational institutions. These everyday practices in the school culture prompt us to reconsider the focus of pedagogical leadership in order to understand how learning is constructed and to acknowledge that it is a democratic act that takes place in a context of symmetrical relationships among those who are learning.

On the other hand, the limited pedagogical autonomy assumed by school leaders reveals a lack of scrutiny of the practices and decisions related to the comprehensive development of students. This is demonstrated when the administration focuses on the development of the capabilities of teachers and technical aspects of teaching, without taking into account the role of the student in the learning process. Furthermore, the apparent professional development of teachers from more instrumental perspectives leaves us with a limited view of education that embraces pedagogical discourse without actually reshaping the practice of learning.

In this context, it is essential to guide school communities to move away from a fragmented view of educational policies to a more integrated and shared perspective on what and how to learn. It is therefore imperative to move beyond the intention of merely responding to measurable and quantifiable educational processes and outcomes and there is a consequent need to advance toward the development of a pedagogical mindset that fosters a new form of school leadership as an intentional process of influence that takes into account and promotes comprehensive learning and development.

To promote a leadership approach focused on students, a proposal has been designed for an educational leadership training model based on the individual in order to guide learning practices in schools. This model was constructed from a situated and dialogical perspective, fostering the development of collaborative professional learning within the context of shared leadership.

Leadership Approaches

In pursuit of promoting the improvement of educational systems, policies have been developed with top-down approaches, often overlooking the learning processes that teachers need to undergo in order to transform the school culture from within the schools themselves and considering the principles of teacher autonomy and collaboration (Blázquez, 2017). Situated approaches to school improvement emphasize processes that take into account contextual factors, as well as essential elements such as educational leadership, which plays a vital role in addressing both internal and external changes and challenges within an organization (Leithwood; Harris; Hopkins, 2019). As a result, when studying educational leadership, it is essential to continually review and question the pedagogical approach that underpins its influence.

Research on leadership and the development of educational processes highlights the need to recognize the close relationship between leadership and learning. This relationship should not be viewed in terms of a cause-and-effect logic, but rather as a mutual alignment (Fullan, 2019; Rincón-Gallardo, 2019). Rincón-Gallardo (2020) contends that leadership is akin to effective pedagogy in the sense that teachers and administrators collaboratively learn to foster a culture of learning within the school. Consequently, it is essential to study the leadership approach from the perspective and conception of learning.

It is considered important to distinguish between student-focused leadership and instructional leadership, given that the latter centers on improving teaching practices and the achievement of learning outcomes, thus manifesting as a widespread phenomenon in the form of pedagogical leadership, sometimes maintaining hierarchical and control-oriented approaches associated with authority, which have been perceived more as instructional leadership rather than leadership for learning (Hallinger, 2009; Rincón-Gallardo, 2020). Several authors argue that the instructional approach limits understanding of the complexity of education, as this clinical concept is more concerned with teachers’ actions in relation to instruction rather than the entirety of the pedagogical process and the school context (Leithwood; Jantzi; Steinbach, 1999 2, as cited in Bush, 2016; Macneill; Cavanagh; Silcox, 2005). Moreover, instructional leadership is evident in administrative practices characterized by excessive technical rationalism, which tends to focus management on teacher supervision or observation of classes from a superficial standpoint, such as the structure of classes or the moments they contain.

The conception of pedagogical leadership from a formative and constructive perspective takes into account the learning process of the student (Bolívar, 2019). This view of learning is driven by leadership as pedagogical influence in the school and is evident in the roles assumed by school leaders, teachers, and students in pursuit of the educational purpose (Elmore, 2010). However, it is important to ask what our vision of learning is, what dimensions it considers, and how it takes place in practice. In other words, it is essential to promote the development of school leadership practices that transform the pedagogical core, which enables the reinterpretation and awareness of how, what, and why learning occurs.

So, notwithstanding pedagogical leadership and the conception of learning it encompasses, many schools are led from a bureaucratic/administrative perspective that focuses on procedures, schedules, and resources, in addition to addressing emergent issues without a clear pedagogical purpose (Bolívar, 2019; Bush, 2016). Furthermore, since there are a range of beliefs within the school organization about pedagogy, leadership centered on learning becomes an imperative and continuous challenge for school leaders (Mellado; Chaucono; Villagra, 2017; Terosky, 2014). This educational challenge entails reshaping the mindset of teachers and transforming leadership practices to exert influence, through formal education, on how and what students learn as individuals in a stage of comprehensive development.

Development of the Training Model for Student-Centered Leadership

The model was developed in the context of a participatory research (PR) framework that shifts away from the traditional object-subject dichotomy, where the research topic is the object of study and the researcher is the subject, towards a more egalitarian subject-subject relationship (Francés et al., 2015). Within this framework, knowledge production is defined from a collaborative and learning-oriented perspective, which involves active discussion and reflection on the purposes and practices of educational leadership. This discussion takes place without prescriptive constraints and is deeply contextualized, connecting practical experiences and knowledge in the field of study (Buttimer, 2018; Fals-Borda; Rodríguez-Brandao, 1987; Kirchner, 2013 3, cited in Vélez-Caro, 2017). Guba and Lincoln (2012) position this type of research within the naturalistic-constructivist paradigms, as it prioritizes the consideration of the meanings that individuals construct and attribute to the everyday processes and experiences in which they are immersed.

The research team for this study was comprised of professionals from the school system and instructors from a university’s school leadership and management program in the La Araucanía region of southern Chile. The team consisted of 10 members, including five academics and five school leaders actively working in educational institutions in La Araucanía. Two inclusion criteria were applied: a) being an advanced student or graduate of the university’s school leadership and management training program, and b) having professional experience as a member of the administrative team of a state-subsidized school in Chile. The specific breakdown of the selection was as follows: five academics (three women and two men), one male and one female principal, one male and one female head of the Pedagogical Technical Unit (UTP), and one classroom teacher with support duties as part of the management team.

The validity of this participatory study is underpinned by the process undertaken by the research team, the members of which, collaborating as a collective, co-construct knowledge based on shared and discussed experiences (Ahumada; Antón; Peccinetti, 2012; Ferrada, 2017).

The research process took seven months and encompassed five phases, which were defined by the research team, taking into account the perspectives of various authors (Francés et al., 2015; Montenegro, 2004):

1) Discussion of ideas: In the first phase, initial discussions were held to consider the requirements of professional training and development of leadership in the school context. Reflective dialogues were used to facilitate the examination of training challenges and the critical assessment of the practices of both trainers and teachers. In this stage, ideas were openly discussed, shaping the collective direction of the process that would be carried out to create a training model for leadership development.

Some guiding questions for this phase included the following:

Based on our professional experience, what are students learning in schools? How do we know what they are learning?

In our current educational roles, what practices do we employ to facilitate learning?

Are we aware of the existence of practices that could hinder teachers’ scholastic and professional learning?

2) Problem identification and diagnosis: Requirements, problems, and challenges of interest to the team members were identified during this phase. As a result of these dialogues, it was agreed to address the development of student-centered school leadership through training in the field and its application in the school context. It should be noted that, during the process of problem identification and diagnosis, the participants engaged in individual and collective readings of relevant texts linking leadership, learning, and comprehensive student development. This literature review served to guide the analysis of leadership practices and prompted pedagogical reflection among the members of the research team. The fact that decisions in schools are often made without considering the students’ perspective was also explicitly addressed.

The following are some of the questions that prompted reflection on the practice:

How do we conceptualize the relationship between leadership and learning? What does the literature reveal about this relationship? What guidance does educational policy provide in this regard?

What do we understand by learning?

How is our conception of learning manifested in our daily practice?

If leadership is connected to learning, how does it relate to the comprehensive development of the student?

How can we demonstrate that individuals are engaged in their learning?

How do students participate in the school? What decisions do they make regarding their own training and that of the school?

3) Design and planning: A collaborative work plan was developed to guide the construction of the model. In the planning phase, questions were posed to help us recall our objectives and the changes we needed to make in order to cultivate student-centered leadership. The participants’ experiences and knowledge thus formed the bases for defining a plan that would facilitate the proposal.

The following are some of the questions that guided the design:

What is the purpose of formal education?

What educational challenges do we envision in both the school and society?

How can we align the relationship between student learning and development?

How can we make learning visible?

4) Development and assessment: The development of the research team’s proposal primarily involved seeking coherence between the objectives and among the various stakeholders involved in developing school leadership. In each session, a collaborative document was created, embodying the ideas that emerged through the exchange, the reflection on practice, and the collaborative knowledge-building process among educators and school leaders.

To develop the model, questions were employed to guide the process of creation and writing, the following being some examples:

What do we know from the literature about pedagogical leadership or student-centered leadership?

What guidance is offered by studies on the characteristics of pedagogical or student-centered leadership?

What evidence do we have about the improvement processes undertaken by Master’s students in their thesis work? What findings have been identified? What facilitators and barriers have been observed in the transformation processes in the context of thesis work?

Which elements would be common and pivotal in triggering student-centered leadership?

What pedagogical principles guide learning and the transformation of school culture?

How do we know that these principles form the foundation of student-centered leadership?

In this phase, the principles of the model were established that guide practice and are not intended to develop prescriptive actions. In this respect, the literature review was conducted with a focus on the variables or dimensions within leadership that impact student learning, including mediating variables such as: a) skills for teaching, b) teacher motivation, and c) working conditions.

Furthermore, the definition of the model’s principles was grounded in a literature review on learning and the continuous development of educational leaders, coupled with pertinent leadership experiences initiated by Master’s students to guide transformations in schools. The document analysis allowed for the preliminary identification of other principles, some of which were subsequently excluded after examining their implications. The principles that were not considered for the model include the following: shared vision, pedagogical core, deep learning, professional learning and development, data usage, shared decision-making, diversity and inclusion, and the reframing of pedagogical beliefs.

Finally, the five principles that were defined for the model (reflection, dialogue, collaboration, inquiry, and self-assessment) are, in some way, a result of the causal study of the principles initially proposed.

5) Self-management projections: In the last phase, which emerged as a result of the collective learning and construction process, discussions revolved around the future prospects of the work undertaken. For the participants, this phase represents both a conclusion and the beginning of a process, as they have expectations about how to further develop the research process. The most significant decision involved the idea of promoting the model within the training program and sharing it in other educational contexts. In this regard, the idea of guiding practice is emphasized rather than prescribing specific actions for implementation. Consequently, considerations are given as to how to facilitate a co-construction process that resonates with other educational stakeholders, enabling them to transform leadership and its educational aspects from a pedagogical standpoint.

Student-Centered Leadership Training Model

The student-centered leadership training model is rooted in the conviction of the team leading a management and leadership teaching program at a Chilean university. In this context, the aim is to foster a shared vision of the development of leadership in schools, which redefines processes, strategies, and actions inherent to in-service training for teachers and school leaders. This collective definition is based on advances in research on educational leadership and a critical analysis of the current purposes and strategies used in the ongoing training of teachers and school leaders, as well as evidence of the performance of students who have completed or are currently enrolled in the program and its impact on the transformation processes of educational institutions.

The model is founded on the need to focus on the study and reflection of educational practices in the school and their influence on the pedagogical core (Elmore, 2010; Rincón-Gallardo, 2019). Its objective is to guide educational action and reflection on practice so that school leaders can interpret the guidelines of educational policy, avoiding the logic of external instructions or mandates. Furthermore, it cultivates a critical perspective on managerial leadership by exclusively focusing on the functions and responsibilities associated with a position, potentially adopting a business-oriented approach over the values that underpin the processes and decision-making within the educational organization (Bush, 2016; Chile, 2015).

Although promoting reflective leadership is essential, it is crucial to recognize that reflection alone will not suffice if professionals do not influence the development of a reflective school culture (Huber; Skedsmo; Schwander, 2018). According to Robinson (2016, p. 46), “much of the work of a student-centered leader involves questioning and modifying ineffective school practices”. For this reason, a leader is expected to take on the role of a “critical friend” and trigger the questioning of practice from a formative and empathetic perspective based on the principle of professional trust (Escudero, 2009; Gurr; Huerta, 2013).

Developing reflective practice as an essential part of leadership is becoming increasingly necessary. Young, Anderson, and Nash (2017) argue that a leader must establish three fundamental conditions: critical reflection, critical awareness, and the ability to adopt multiple approaches. These more contemporary perspectives go beyond the traditional view of training focused on regulations, theoretical aspects, or the mere handling of information in the field. Furthermore, they make it clear that the responsibilities of teams leading processes in schools do not adhere to standard leadership models that could be arbitrarily applied in various contexts (Bush, 2016).

Lastly, the needs for development of leadership in schools translate into challenges for professional training. In this regard, Spillane and Ortiz (2019) encourage a reevaluation of traditional modes of training for school leaders, which focus more on individual roles in the school rather than the formation and practice of management teams. In this context, it is important to ascertain whether the training approaches and modalities for school leadership are aligned with the objectives and educational strategies of the training itself. In other words, if we want school leaders to promote dialogue, collaboration, reflection, inquiry, and self-assessment in schools, it is imperative that they receive training grounded in these principles (Lambert, 2016; Seashore, 2017).

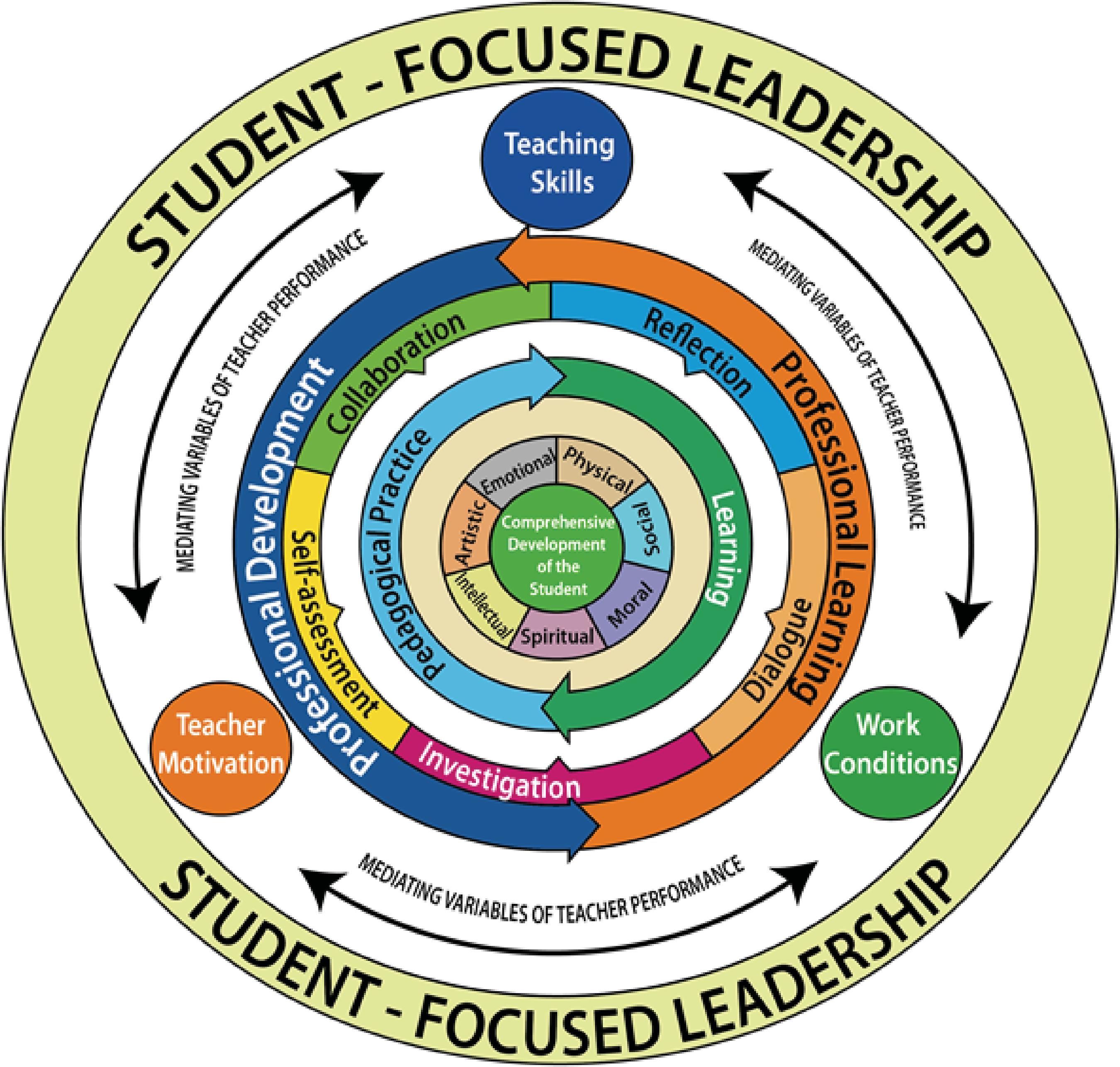

To summarize, promoting the development of student-centered leadership (Robinson, 2016) entails making a transition from a traditional perspective focused solely on teaching to one that emphasizes student learning and comprehensive development. This is why the model focuses on developing the student in seven dimensions: spiritual, ethical, moral, emotional, intellectual, artistic, and physical (Chile, 2009). This development is guided by pedagogical practices and the learning opportunities designed for students. Moreover, the enhancement of pedagogical practice takes place within a context of learning and professional development characterized by collaboration, reflection, dialogue, inquiry, and self-assessment as principles that guide student-centered educational processes.

To promote student development, one must consider the so-called mediating variables of teacher performance: instructional skills, teacher motivation, and working conditions. Each of these factors affects student learning and, in turn, can be influenced by school leadership (Bolívar, 2012; Cifuentes-Medina, González-Pulido, González-Pulido, 2020). It is important to note that all three variables should be fostered through practices that consistently establish their influence on the learning and comprehensive development of students.

In a certain way, the mediating variables demonstrate that professional development of teachers is not only linked to professional knowledge but also to their motivation. In this regard, Fink (2016) argues that even the most motivated teachers can experience burnout if they lack support, both in terms of working conditions and their ongoing professional learning process. It is also important to note that these conditions, in addition to referring to material aspects, encompass other elements such as schedules, operational methods, and the support available to teaching staff in a school to enable them to meet the educational objectives. In this context, there are different ways of creating adequate working conditions. Some of them are more oriented towards training and support, while others place greater emphasis on a prescriptive or supervisory approach.

In Figure 1 below, we present a depiction of the student-centered leadership model, the implementation of which in schools requires training processes for school leaders that are consistent with the principles underpinning the proposal.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on Villagra (2019).

Figure 1 Student-centered leadership model

Principles of the Training Model

The training model for student-centered leadership comprises five principles aimed at guiding the development of leadership in schools and the ongoing training of educational leaders.

Reflection on Practice

This principle is conceived as a process of dialogue, analysis, and questioning of both directive and pedagogical practices in light of their impact on the learning and comprehensive development of students. Therefore, it is a process that constantly evolves. Professional reflection is structured as a methodical, personal, and collective practice aimed at continuous improvement of professional performance and the transformation of traditional educational approaches (Mellado; Chaucono; Villagra, 2017). In this respect, critical reflection challenges the action theories that underpin practice and enables the exploration of new alternatives based on theoretical and empirical knowledge.

There is a need to promote reflective leadership because it is not enough for those who lead educational institutions to be reflective professionals if they do not influence the development of a reflective school culture (Huber; Skedsmo; Schwander, 2018; Young; Anderson; Nash, 2017). Pedagogical leadership would help foster the development of collective reflective practice linked to the ongoing objective of improving learning, resulting in questioning of the educational process and the development of pertinent and timely responses. As Domingo (2020) argues, the reflection that this involves is connected to professionals who work and learn based on real-world practice.

Professional Dialogue

We understand professional dialogue as a process of learning and building of collective knowledge based on purposeful professional conversations that guide pedagogical reflection. In this respect, dialogue is a fundamental principle of learning because it is acknowledged that we learn naturally through interaction with others, with whom we construct reality and give it meaning, leading us to decision-making and action. Professional dialogue is closely connected to collaborative learning, as it fosters the creation of new knowledge through the contributions of each individual.

Productive dialogue that facilitates reflection within and about action is characterized by equality between its participants, who can openly and empathically analyze practice from differing perspectives, while argumentation is based on empirical evidence and theoretical foundations (Urdaneta, 20144, as cited in Mérida-Serrano et al., 2020). According to Seashore (2017), conversations among educators about their practices may become irrelevant if the dialogue is not supported by information that stimulates discussion and reflection. Therefore, professional dialogue aimed at building knowledge through the interplay of theory and practice must be purposeful, involving challenging questions or issues that push the boundaries of our prior knowledge without becoming unpleasant.

Hargreaves and O’Connor (2020) regard mutual dialogue as one of the 10 principles of collaborative professionalism, underscoring that it is not merely any conversation among educators, but rather an interaction that can be challenging because there is honest feedback and genuine discussion about certain ideas. That said, dialogue is not just an exchange of information or opinions, as it involves participants, as learners, being open to uncertainty and engaging in an internal dialogue with themselves as they reframe their knowledge and perspectives through interpersonal dialogue, which encourages improvement. It is important to note that as purposeful and pedagogical professional dialogues develop, they promote shared leadership that is rooted in processes and relationships between people, rather than being centered on individuals holding formal positions within an organization or on individual actions (Lambert, 2016; Spillane; Ortiz, 2019).

Collaboration

We understand collaboration as a key competency of the 21st century. Therefore, it is also a strategy that school leaders and educators, as well as students in the classroom, must develop to progress toward a culture of collaboration. From this perspective, it becomes essential for leadership training and development to operate on the principle of collaboration, which in practice involves working with others to achieve a common purpose. This, in turn, requires adopting the stance of a learner-leader (Rincón-Gallardo; Fullan, 2015) who is willing to collaboratively learn with others, co-constructing diverse knowledge in a situated manner considering a dynamic perspective of knowledge, rather than viewing it as something static and unchanging.

Although collaboration leverages the skills and contributions of each individual to carry out collective projects, it also represents an opportunity to cultivate trust, a collaborative spirit, reciprocity, and shared responsibility in the task undertaken. In other words, values and attitudes related to collaboration are not prerequisites for the development of collaborative work, but they are instead fostered within the work itself. In this sense, collaboration is a social learning experience in which each person learns more than they would individually, thanks to intentional interaction for the shared construction of new practical knowledge.

The objective of training school leaders and promoting their development within the school is to foster a collaborative culture that, as Blázquez (2017, p. 23) puts it, does not arise from “the existence of meetings or bureaucratic arrangements, but from the presence of specific attitudes and behaviors that develop within the interactions of educators, moment by moment, day by day.” Therefore, the challenge goes far beyond defining collaborative structures, as these can evolve into hierarchical and bureaucratic proposals that ultimately do not promote deep learning (Rincón-Gallardo; Fullan, 2015). Intentionality is required for collaboration to become a habitual and pervasive practice, encompassing both dialogue and action from a reflective perspective (Hargreaves; O’Connor, 2020). It is important to note that although schools are organized into networks or groups of professionals, this structure alone is not sufficient to sustain authentic processes of collaboration.

Professional Inquiry

We define professional inquiry as an inquisitive attitude aimed at improving the educational processes in which we are involved. According to Currin (2019), a posture of inquisitiveness empowers educators to transform teaching for the benefit of all their students in an ever-evolving socio-educational context. In light of this, “Inquiry is the opposite of transmission” (Wolk, 2008, p. 118). Therefore, it should not be understood as a set of steps to follow or as exclusive processes of professional exchange. Its bases lie in the process of co-constructing knowledge in a situated manner, supported by the study and reflection of one’s own practice.

Inquiry is a form of participatory research that encourages professionals to engage in reflection and deep learning. It is aimed at enabling professionals to comprehend and reshape the classroom into a realm of continuous inquiry. This collaborative process involves identifying practice-related challenges that serve as shared objectives for deliberate collective efforts aimed at enhancing learning practices, all of which is in pursuit of fostering a mindset rooted in exploratory thinking.

Pino, González, and Ahumada (2018) contend that collaborative inquiry is an ongoing cyclical process driven by the educational agents themselves. In this sense, it is conducive to conduct inquiry as part of the daily work of teachers, who consistently and cyclically design, implement, assess, and reflect. It thus becomes possible to link inquiry with continuous professional development as a situated and collective process that evolves into organizational learning (Bolívar, 2019; Vaillant, 2017).

Self-Assessment as Practice

We conceive self-assessment as a practice inherent to the learner, as it enables self-regulation (Sanmartí, 2020) across various dimensions of personal development. Thus, self-assessment is not limited to a specific moment in the educational process, but rather represents a disposition to continuously scrutinize one’s own performance. This act of self-observation is crucial for enhancing the practices of a leader who takes responsibility without attributing the causes of educational issues to factors external to the school.

Self-assessment has an inherently individual nature, but typically takes place in a social context, as it occurs in relation to various benchmarks that create conflicts in one’s thinking and actions, fostering an awareness of our learning needs and challenges. In other words, educators who possess the skill of learning to learn can identify and regulate their difficulties, promptly seeking meaningful assistance to overcome them.

Promoting a culture of assessment as learning within schools necessitates encouraging the practice of self-assessment because it holds greater pedagogical value, granting learners the opportunity to reflect and become aware of their own process of development (Villagra; Fritz, 2017). Therefore, the learner-leader learns alongside the teaching staff, the teaching staff learns with their students, and the students learn from one another (Rincón-Gallardo, 2019), all within a culture that fosters integrated self-assessment as an essential part of school activities, with a focus on the learning and comprehensive development of the student.

Self-assessment is essentially aimed at understanding how and what is being learned. It entails moving away from a simplistic view of self-measurement as a mere comparison between actual performance and an ideal or expected standard, towards a more profound and complex understanding of education. This involves seeking answers to gain insights and make informed decisions regarding learning practices (Santos Guerra, 2017).

The Learning and Assessment Approach that Underpins the Model

The training model is based on the socio-constructivist paradigm, where learning is conceived as a process of social construction (Montanero; Guisado, 2017). Therefore, it explicitly recognizes and examines prior experiences and knowledge for the purpose of co-constructing and reconstructing situated practical knowledge. It is important to note that training takes place in the context of practice and is aimed at extending beyond the mere combination of theoretical and practical methodologies.

Just as leadership is expected to develop in the school, a training proposal is also made that is aligned with the principles of reflection, dialogue, collaboration, inquiry, and self-assessment. In this regard, training is not viewed as mere instruction in specific knowledge, but rather as an effort to cultivate a way of thinking that can transform the nature of everyday professional activities and rejuvenate the school culture. With this premise, the training proposal is intended to enhance school management practices in such a way that allows any professional to become a school leader, and particularly if we acknowledge that leadership is not confined to a specific position.

On the other hand, García, Díaz, and Ubago (2018) reflect on the objectives of continuous education, which are openly tailored distinctly for teachers and school principals, a practice that may not be consistent with the learning dynamics of the school community. Consequently, the authors argue that programs centered on pedagogical leadership, bringing together teachers and principals, can provide guidance for developing collaboration-based leadership practices and, in turn, foster systemic and sustainable improvement over time. From this same perspective, Seashore (2017) contends that when leaders have opportunities to grow within professional learning communities, there is a significantly increased likelihood of functioning as a learning community in the school they lead. In response to this challenge, it is essential to make every possible effort to achieve continuous and coherent professional development and training.

According to Fullan and Langworthy (2014, p. 4), the educational process is considered as new pedagogies where students and teachers collaborate together in learning. Thus, “the learning process becomes the focal point for the mutual discovery, creation and use of knowledge”. From this perspective, new pedagogies are not merely new strategies or techniques, but they involve a different conception of the learning process and the roles assumed by students and teachers, who deliberately play different roles during the process, sometimes as learners and at other times as instructors (Rincón-Gallardo, 2019). This viewpoint promotes situated learning and professional development, considering that teachers and school leaders share responsibility in these reciprocal learning processes. It is therefore essential to broaden the notion of learning as a means of developing thinking and individuals, rather than viewing it as static knowledge that accumulates and upon which many make prescriptive or established decisions.

According to Quinn et al. (2021), the concept of deep learning entails increased engagement on the part of the learner to design and assess their learning process. This responsibility is assumed with greater self-control when the purpose of learning is understood, providing an opportunity to trigger metacognitive processes that enable awareness of the learning process. As outlined by Marcelo and Vaillant (2018), learning from and within practice requires a foundation. Therefore, when undertaking learning projects to address everyday problems, the tension arising from local and global empirical evidence must be considered, encouraging reflection and informed decision-making. Building upon this understanding of the learning process, the aim is to foster the development of a shared vision among teachers and school leaders regarding what, how, and why we learn. This vision should also be extended within schools, as learning is a shared practice among all educational stakeholders.

Lastly, it is essential to emphasize the adoption of the approach of assessment as learning, where assessment is a practice that transcends the roles of educational agents. Connected to reflective inquiry, the goal is to facilitate self-assessment of practices, allowing school leaders to self-regulate their performance in relation to the meaning and purpose of their pedagogical influence in the school. In order to achieve this, leaders must engage in reflecting on their beliefs and collaborate effectively to transform traditional practices into ones that are participatory, co-constructive, and dialogical (Rojas-Drummond et al., 2016). It is also expected that those responsible for training school leaders will promote more contextually grounded, authentic, and relevant learning and professional development programs, continually subjecting their own training to discussion and examination.

Discussion and Conclusion

One of the key elements in fostering the development of student-centered leadership is the ongoing training of teachers who specialize in school management to lead educational institutions. In this regard, it is important for that training to be aligned with the needs of practice and the sustainability of future leadership and its development. To achieve this, institutions should engage in participatory assessments that enable them to plan training processes that are relevant (Hallinger, 2016; Huber; Skedsmo; Schwander, 2018).

In order to reconsider more relevant and collaborative training processes, it is crucial to validate new methods of generating situated knowledge that enable genuine involvement of the educational stakeholders. This is accomplished through teacher teams that conduct research into their own pedagogical practices. These collaborative studies promote real changes in practice because they involve discussion, reflection, and learning throughout the development process (Buttimer, 2018; Francés et al., 2015; Kirchner, 2013, as cited in Vélez-Caro, 2017).

The student-centered leadership training model explicitly outlines the purpose and approach to school management to guide educational practice. It avoids prescribing specific leadership actions that instrumentalize transformations and can vary according to the context (Hallinger, 2016). Therefore, there is a recognition of the need to challenge school leaders to focus on the comprehensive development of students. This entails rigorously examining the pedagogical principles of the learning process and the pedagogical practices that impact it (Elmore, 2010; Rincón-Gallardo, 2019; 2020).

In order to raise awareness about the need to center educational management and leadership on the student as an individual, it is imperative to continuously question entrenched practices in the school culture and examine their alignment with educational objectives to ensure the comprehensive development of students. This is a complex challenge because the structures and practices of the conventional school culture tend to be hierarchical and bureaucratic, thereby constraining the possibilities for deep learning in schools (Bolívar, 2012; Rincón-Gallardo; Fullan, 2015). It is therefore essential to reconsider the concept of pedagogical leadership, as its traditional understanding is confined to the management of teaching and academic outcomes. In this context, there are schools that focus on enhancing teaching capabilities from a traditional perspective of teaching, with a greater emphasis on certain subjects in the school curriculum, which, in turn, limits the potential for profound educational transformation.

The management undertaken by school leadership teams for teaching staff goes beyond the mere update of disciplinary knowledge (Marcelo; Vaillant, 2018), as it involves the development of a way of thinking and doing, essentially fostering a culture of “learning to learn”. In conclusion, it is evident that pedagogical principles guide the construction of learning and give meaning to the transformations in the practice of student-centered leadership. The proposed training program therefore incorporates the principles of collaboration, dialogue, professional inquiry, reflection, and self-assessment of educational practice.

The necessity to strengthen learner-centered leadership requires a review of overall educational policies and not merely those pertaining to the individuals who assume roles in school leadership. In this regard, there is evidence in Chile indicating an incongruity between policy principles and their coherent implementation in the system. Furthermore, there is “the overlapping of contradictory frameworks of pressure and support for school actors” (dos Santos, 2018, p. 10). This situation may not contribute to fostering a profound understanding of the educational purpose and the social nature of learning. Consequently, research processes could help to shed light on and understand the experiences of educational agents in school communities, in contrast to hegemonic views of the school’s purpose (Neut et al., 2019).

Finally, it is important to underscore that this model is not intended to prescribe a particular way of conceptualizing leadership and its development. Instead, it represents a participatory research proposal that encourages other training teams to engage in deliberate and shared reflection processes regarding the learning culture in educational organizations and continuous teacher education. Therefore, the use of the model on its own is limited, which is why it is advisable to explore leadership and training practices from a situated perspective that helps to address the educational challenges we encounter in the 21st century.

REFERENCES

AHUMADA, Marcelo; ANTÓN, Bibiana Mariela; PECCINETTI, María Verónica. El desarrollo de la Investigación Acción Participativa en Psicología. Enfoques, Libertador San Martín, v. 24, n. 2, p. 23-52, 2012. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1669-27212012000200003&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es. Acceso en: 3 ene. 2019. [ Links ]

BLÁZQUEZ, Florentin. La autonomía escolar para la mejora de la escuela. In: VALDEBENITO, Vanessa; MELLADO, María Elena (Ed.). Liderazgo Escolar y Gestión Pedagógica. Temuco: Universidad Católica de Temuco, 2017. [ Links ]

BOLÍVAR, Antonio. Políticas actuales de mejora y liderazgo educativo. Málaga: Aljibe, 2012. [ Links ]

BOLÍVAR, Antonio. Una dirección escolar con capacidad de liderazgo pedagógico. Madrid: La Muralla, 2019. [ Links ]

BUSH, Tony. Mejora escolar y modelos de liderazgo: hacia la comprensión de un liderazgo efectivo. In: WEINSTEIN, José (Ed.). Liderazgo educativo en la escuela. Nueve miradas. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Diego Portales, 2016. [ Links ]

BUTTIMER, Christopher. The challenges and possibilities of youth participatory action research for teachers and students in public school classrooms. Berkeley Review of Education. California, v. 8 n. 1, p. 39-81, 2018. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.5070/B88133830. Acceso en: 3 ene. 2019. [ Links ]

CHILE. Ley Nº 20.370, 12 de septiembre de 2009. Establece la Ley General de Educación (LGE). Biblioteca del Congresso Nacional de Chile, Chile, 2009. Disponible en: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1006043. Acceso en: 5 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

CHILE. Ministerio de Educación. Marco para la Buena Dirección y el Liderazgo Escolar. Santiago de Chile: Minieduc, 2015. Disponible en: https://liderazgoescolar.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/55/2016/04/MBDLE_2015.pdf. Acceso en: 5 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

CIFUENTES-MEDINA, José; GONZÁLEZ-PULIDO, José; GONZÁLEZ-PULIDO, Alexandra. Efectos del Liderazgo Escolar en el Aprendizaje. Panorama, Bogotá, v. 14, n. 26, p. 78-93, 2020. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.15765/pnrm.v14i26.1482. Acceso en: 20 feb. 2022. [ Links ]

CURRIN, Elizabeth. From Rigor to Vigor: The Past, Present, and Potential of Inquiry as Stance. Journal of Practitioner Research, Florida, v. 4, n. 1, p. 1-21, 2019. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.5038/2379-9951.4.1.1091. Acceso en: 20 feb. 2022. [ Links ]

DOMINGO, Ángels. Rasgos y habilidades del profesor-investigador. In: DOMINGO, Ángels (Ed.). Profesorado reflexivo e investigador. Propuestas y experiencias formativas. Madrid: Narcea, 2020. [ Links ]

DOS SANTOS, Cristina Aziz. Nota técnica No 2. Evolución e implementación de las políticas educativas en Chile. Valparaíso: Centro de Liderazgo para la Mejora Escolar, 2018. Disponible en: https://www.lidereseducativos.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NT2_L6_C.A_Evolucio%CC%81n-e-implementacio%CC%81n-de-las-poli%CC%81ticas-educativas-en-Chile.pdf. Acceso en: 15 ene. 2019. [ Links ]

ELMORE, Richard. Mejorando la escuela desde la sala de clases. Santiago de Chile: Área de Educación Fundación Chile, 2010. [ Links ]

ESCUDERO, Juan. El amigo crítico, una posibilidad para la formación del profesorado en los centros. Compartim: Revista de Formació del Professorat, Valencia, n. 4, p. 1-4, 2009. [ Links ]

FALS-BORDA, Orlando; RODRÍGUEZ-BRANDAO, Carlos. Investigación Participativa. Montevideo: La Banda Oriental, 1987. [ Links ]

FERRADA, Donatila. Investigación participativa dialógica. In: RASCO, José Félix Angulo; PANTOJA, Silvia Redon (Coord.). Investigación cualitativa en educación. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 2017. [ Links ]

FINK, Dean. Hacia un liderazgo sostenible, más profundo, más prolongado, más amplio. In: WEINSTEIN, José et al. Liderazgo educativo en la escuela: nueve miradas. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Diego Portales, 2016. [ Links ]

FRANCÉS, Francisco et al. La investigación participativa: métodos y técnicas. Cuenca: PYDLOS. 2015. [ Links ]

FULLAN, Michael. Liderar los aprendizajes: acciones concretas en pos de la mejora escolar. Revista Eletrônica de Educação, São Carlos, v. 13, n.1, p. 58-65, 2019. [ Links ]

FULLAN, Michael; LANGWORTHY, María. Una rica veta. Cómo las nuevas pedagogías logran el aprendizaje en profundidad. London: Pearson, 2014. Disponible en: https://www.pearson.com/content/dam/one-dot-com/one-dot-com/global/Files/about-pearson/innovation/open-ideas/ARichSeamSpanish.pdf. Acceso en: 18 mar. 2019. [ Links ]

GARCÍA, Inmaculada; DÍAZ, Miguel; UBAGO, José Luis. Educational Leadership Training, the Construction of Learning Communities. A Systematic Review. Social Sciences, Basel, v. 7, n. 267, p. 1-13, 2018. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7120267. Acceso en: 12 feb. 2019. [ Links ]

GUBA, Egon; LINCOLN, Yvonna. Controversias paradigmáticas, contradicciones y confluencias emergentes. In: DENZIN, Norman; LINCOLN, Yvonna (Coord.). Manual de metodología cualitativa v. II: Paradigmas y perspectivas en disputa. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2012. [ Links ]

GURR, David; HUERTA, Marcela. The role of the critical friend in leadership and school improvement. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Sakarya, v. 106, p. 3084-3090, 2013. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.356. Acceso en: 22 dic. 2018. [ Links ]

HALLINGER, Philip. Leadership for 21st century schools: from instructional leadership to leadership for learning. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Institute of Education, 2009. [ Links ]

HALLINGER, Philip. Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management, Administration and Leadership, v. 46, n. 1, p. 5-24, 2016. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216670652. Acceso en: 18 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

HARGREAVES, Andy; O’CONNOR, Michael. Profesionalismo Colaborativo. Cuando enseñar juntos supone el aprendizaje de todos. Madrid: Morata, 2020. [ Links ]

HUBER, Stephan; SKEDSMO, Guri; SCHWANDER, Marius. Cómo aprenden los directivos y fortalecen su reflexión profesional en tanto líderes pedagógicos. In: WEINSTEIN, José; MUÑOZ, Gonzalo (Ed.). Cómo cultivar el liderazgo educativo. Trece miradas. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Diego Portales, 2018. [ Links ]

KIRCHNER, Alicia. La investigación acción participativa. Foro Latinoamérica. 2013. [ Links ]

LAMBERT, Linda. Liderazgo constructivista: Forjar un camino propio en pos de la reforma escolar. In: WEINSTEIN, José et al. Liderazgo educativo en la escuela: nueve miradas. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Diego Portales, 2016. [ Links ]

LEITHWOOD, Kenneth; HARRIS, Alma; HOPKINS, David. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, Londres, v. 40, n. 4, p. 1-18, 2019. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077. Acceso en: 10 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

MACNEILL, Neil; CAVANAGH, Robert; SILCOX, Steffan. Pedagogic leadership: Refocusing on learning and teaching. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning, Edmonton, v. 9, n. 2. 2005. Disponible en: https://typeset.io/pdf/pedagogic-leadership-refocusing-on-learning-and-teaching-3x7j8hvj5r.pdf. Acceso en: 17 jul. 2018. [ Links ]

MARCELO, Carlos; VAILLANT, Denise. Hacia una formación disruptiva de docentes: 10 claves para el cambio. Madrid: Narcea, 2018. [ Links ]

MELLADO, María Elena; CHAUCONO, Juan Carlos; VILLAGRA, Carolina. Creencias de directivos escolares: implicancias en el liderazgo pedagógico. Revista Psicología Escolar e Educacional, São Paulo, v. 21, n. 3, p. 541-548, 2017. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-353920170213111102. Acceso en: 16 jul. 2018. [ Links ]

MÉRIDA-SERRANO, Rosario et al. El Prácticum, un Espacio para la Investigación Transformadora en los Contextos Educativos Infantiles. REICE – Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, Madrid, v. 18, n. 2, p. 17-34, 2020. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2020.18.2.001. Acceso en: 5 ene. 2022. [ Links ]

MONTANERO, Manuel; GUISADO, Pilar. Comunidades de aprendizaje: La gestión del aula mediante grupos interactivos. In: VALDEBENITO, Vanessa; MELLADO, María Elena (Ed.). Liderazgo Escolar y Gestión Pedagógica. Temuco: Universidad Católica de Temuco, 2017. [ Links ]

MONTENEGRO, Marisela. La investigación acción participativa. In: MUSITU, Gonzalo et al. (Ed.). Introducción a la Psicología Comunitaria. Barcelona: UOC, 2004. [ Links ]

NEUT, Pablo; RIVERA, Pablo; MINO, Raquel. El sentido de la escuela en Chile. La creación de paradigmas antagónicos a partir del discurso de política pública, el discurso académico y la investigación educativa. Estudios Pedagógicos, Valdivia, v. 45, n. 1, p. 151-168, 2019. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052019000100151. Acceso en: 11 oct. 2022. [ Links ]

PINO, Mauricio; GONZÁLEZ, Álvaro; AHUMADA, Luis. Indagación colaborativa: Elementos teóricos y prácticos para su uso en redes educativas (informe técnico n°4). Valparaíso: Centro de Liderazgo para la Mejora Escolar, 2018. Disponible en: https://www.lidereseducativos.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/IT4_L2_M.P.-A.G.-L.A._INDAGACION-COLABORATIVA-ELEMENTOS-TEORICOS-Y-PRACTICOS-PARA-USO-EN-REDES_27-11-18.pdf. Acceso en: 12 ene. 2019. [ Links ]

QUINN, Joanne et al. Sumergirse en el Aprendizaje Profundo. Herramientas atractivas. Madrid: Morata, 2021. [ Links ]

RINCÓN-GALLARDO, Santiago. Liberar el aprendizaje. Ciudad de México: Grano de Sal, 2019. [ Links ]

RINCÓN-GALLARDO, Santiago. De-schooling Well-being: Toward a Learning-Oriented Definition. ECNU Review of Education, Shanghái, v. 3, n. 3, p. 452-469, 2020. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120935472. Acceso en: 12 ene. 2021. [ Links ]

RINCÓN-GALLARDO, Santiago; FULLAN, Michael. Física Social del Cambio Educativo. Características Esenciales de la Colaboración Eficaz. In: SEMINARIO INTERNACIONAL EDUCACIÓN DE CALIDAD CONTRA LA POBREZA, 8., Santiago de Chile, 2015. Santiago de Chile: Santiago Rincón-Gallardo y Michael Fullan, 2015. [ Links ]

ROBINSON, Viviane. Hacia un fuerte liderazgo centrado en el estudiante: Afrontar el reto del cambio. In: WEINSTEIN, José et al. Liderazgo educativo en la escuela: nueve miradas. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Diego Portales, 2016. [ Links ]

ROJAS-DRUMMOND, Sylvia; MÁRQUEZ, Ana; PEDRAZA, Haydé. Innovando en el aula a través de un programa de formación docente en la práctica. In: MANZI, Jorge; GARCÍA, María Rosa (Ed.). Abriendo las puertas del aula. Transformación de las prácticas docentes. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones UC, 2016. [ Links ]

SANMARTÍ, Neus. Evaluar y aprender: un único proceso. Barcelona: Octaedro, 2020. [ Links ]

SANTOS GUERRA, Miguel. Evaluar con el Corazón: de los ríos de las teorías al mar de la práctica. Rosario: Homo Sapiens, 2017. [ Links ]

SEASHORE, Karen. Liderazgo y aprendizajes: implicancias para la efectividad de las escuelas. In: WEINSTEIN, José; MUÑOZ, Gonzalo (Ed.). Mejoramiento y Liderazgo en la Escuela. Once Miradas. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Diego Portales, 2017. [ Links ]

SPILLANE, James; ORTIZ, Melissa. Perspectiva distribuida del liderazgo y la gestión escolar: implicancias cruciales. Revista Eletrônica de Educação, São Carlos, v. 13, n. 1, p. 169-181, 2019. [ Links ]

TEROSKY, Aimee. From a managerial imperative to a learning imperative: experiences of urban, public school principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, Salt Lake City, v. 50, n. 1, p. 3-33, 2014. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X13488597. Acceso en: 16 ene. 2020. [ Links ]

VAILLANT, Denise. Directivos y comunidades de aprendizaje docente: un campo en construcción. In: WEINSTEIN, José; MUÑOZ, Gonzalo (Ed.). Mejoramiento y Liderazgo en la Escuela. Once Miradas. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Diego Portales, 2017. [ Links ]

VÉLEZ-CARO, Olga. El quehacer teológico y el método de investigación acción participativa, una reflexión metodológica. Theologica Xaveriana, Bogotá, v. 67, n. 183, p. 187-208, 2017. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx67-183.qtmiap. Acceso en: 2 ene. 2021. [ Links ]

VILLAGRA, Carolina. Diseño de un modelo formativo de liderazgo centrado en el estudiante desde el análisis de prácticas de gestión escolar y resultados educativos. 2019. 531 f. Tesis (Doctorado en Educación) – Programa de Doctorado Innovación Innovación en Formación del Profesorado, Asesoramiento, Análisis de la Práctica Educativa y TIC en Educación, Universidad de Extremadura, España, 2019. [ Links ]

VILLAGRA, Carolina; FRITZ, Rosemarie. La autoevaluación orientada al mejoramiento educativo: Una experiencia basada en la reflexión de la práctica docente. In: VALDEBENITO, Vanessa; MELLADO, María Elena (Ed.). Liderazgo Escolar y Gestión Pedagógica. Temuco: Universidad Católica de Temuco, 2017. [ Links ]

WOLK, Steven. School as inquiry. The Phi Delta Kappan, Bloomington, v. 90, n. 2, p. 115-122, 2008. Disponible en: http://www.pdkmembers.org/members_online/publications/Archive/pdf/k0810wol.pdf. Acceso en: 20 ene. 2021. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Michelle; ANDERSON, Erin; NASH, Angel. Preparing school leaders: Standards-based curriculum in the United States. Journal of Leadership Education, Londres, v. 10, n. 1, p. 3-10, 2017. [ Links ]

Received: March 30, 2023; Accepted: August 28, 2023

text in

text in