Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educação e Realidade

Print version ISSN 0100-3143On-line version ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.48 Porto Alegre 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236124125vs01

THEMATIC SECTION: FAUNA, FLORA, OTHER LIVING BEINGS AND ENVIRONMENTS IN SCIENCE AND BIOLOGY EDUCATION

Minor Environmental Education, Decoloniality and Artistic Activism

IUniversidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM), Maringá/PR – Brazil

This article discusses a minor environmental education that avoids the contradictions of sustainable development based on neoliberal economic perspectives. Along with the idea of minority, based on post-critical thinking, decolonial and transdisciplinary propositions of education for environments are presented. To this end, the critique of the Anthropocene/Capitalocene and the artistic activism of representatives of indigenous communities, as ideas to postpone the end of the world, are mapped in the text and promote differentiated propositions that can be considered alongside Science Education.

Keywords Environmental Education; Decoloniality; Sustainable Development; Ecological Subject; Science Education

Discute-se uma educação ambiental menor que escapa das contradições do desenvolvimento sustentável pautado na ótica econômica neoliberal. Junto à ideia de minoridade, fundamentada no pensamento pós-crítico, apresentam-se proposições decoloniais e transdisciplinares de educação para os ambientes. Para tal, a crítica ao Antropoceno/Capitaloceno e o ativismo artístico de representantes das comunidades indígenas, como ideias para adiar o fim do mundo, são cartografadas no texto e agenciam proposições diferenciadas que podem ser pensadas junto ao Ensino de Ciências.

Palavras-chave Educação Ambiental; Decolonialidade; Desenvolvimento Sustentável; Sujeito Ecológico; Ensino de Ciências

Introduction

This academic work, writing-essay cartography aspiration, aims to problematize minor environmental education using a decolonial approach and present a proposal focused on the political resistance values of indigenous peoples. We begin by criticizing the utilitarian and consumerist view of neoliberal society, productivity, capital accumulation, natural resource exploitation, and expropriation through colonialist culture and the environmental-humanitarian crisis.

Since the 1980s, environmental education has been an epistemology and field of study for taking attitudes and values towards environments, oscillating between the technical-natural dimension and the historical-social dimension (Brugger, 1994). However, many approaches to environmental education, even from a critical perspective (Tozoni-Reis, 2008), avoid political debate and erase the inclusive ethnic-social vision of the perspective of native peoples in the composition of non-colonialist didactic discussions and interventions, thus disregarding the reciprocity and knowledge exchanges that include these socio-environmental minorities (Lima; Goldman, 2017).

Through epistemological erasures, that is, the disregard for situated knowledge and identity intersections beyond the environment category, many environmental education approaches and discourses, even though they claim to have a multiplicity of analyses on eco-social issues, end up being one-dimensional, naïve, uncritical, and disseminators of univocal relations and not environmental pluralities. In our view, it is necessary to problematize this discursive naivety, the term sustainability and its implications, especially to counter the ideas of sustainable development disseminated by common sense (Reigota, 2007), contesting the “[...] perpetuation of coloniality founded on racialization, subordination, exclusion, and domination” (Melo; Barzano, 2020, p. 148), and seek theoretical and Southern approximations for the repositioning of education directed towards environments.

Historically, the idea of sustainable development was consolidated in the 1970s through various international conferences and debates on the environment1, natural and environmental resource renewal, climate, pollution, technology, conservation/preservation, and the world economy, becoming well-known in the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED / ECO-92) or Earth Summit, held in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The conference produced the Agenda 21 and other documents that conduct the commitment of signatory countries and civil organizations to adopt socio-environmental strategies, solutions, and public policies at the local, regional, and global levels. The proposals of the Earth Summit, which encompass changes in attitudes towards climate change caused by the burning of fuels, poverty eradication, consumption reduction, and awareness, among other issues, embodied hopes for education (both formal and informal) aimed at sustaining and providing for the environmental needs of current and future generations, while considering biological, cultural, political, economic, and ethical aspects as modifiers of the modus operandi of post-industrial society.

Twenty years after the Earth Summit, the RIO+20 Conference bequeathed to the world documents considered fundamental for the promotion of sustainably managed development, namely: the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the Declaration of Principles on Forests, the Earth Charter, the restructuring of Agenda 21, and conventions on biological diversity and climate change. At the same time, the idea of sustainable development was captured by the neoliberal economic network, which brings with it directly perceptible contradictions in proposals, agreements, and recommendations of other conferences and norms that mix economy and nature, market, and the environment, the call for an ecological turn, on the one hand, and, the “[...] subscription to the need for economic growth, free trade, privatization, and deregulation (Misoczky; Böhm, 2012, p. 549).

According to Paula Brugger (1994), the term sustainable development encompasses two meanings: a more ethical and political one, with understandings of race, ethnicity, color, cultural belonging, gender, class, and labor as categories and ways to think - situatedly - the eco-environmental relationship; and a more technical one, involving the management of natural resources within the logic of global financial capital (Brugger, 1994). The first meaning has been overshadowed by the second in recent decades.

The notion of sustainable development, as exposed by the contradiction presented before, has been co-opted by capitalist hegemony and neoliberalism, which are the prevailing economic and social system/paradigm dictated by the global North to peripheral countries. Within the prevailing economic perspective, the pursuit of socio-environmental sustainability has lost its transformative significance, becoming a cliché or an empty phrase repeated excessively.

Antithetical expressions such as sustainable capitalism, green labeling, sustainable resource use, and green entrepreneurship (O’Connor2, 1994 apud Misoczky; Böhm, 2012) have effects on subjectivities and public policies. As a result, environmental individuals and agendas (both national and international) engage in or perform discourses on sustainability and ecology.

On the contrary, Marcos Reigota argues that the notion of sustainability, from a historical perspective, is radically opposed to that of sustainable development and macropolitics, which presupposes changes in the economic system at its capitalist foundations and implies “[...] a political, social, cultural, and biological dimension that demands an extensive production and dissemination of knowledge and ethical-political principles in the spaces of everyday social practices” (Reigota, 2007, p. 222). Sustainability also encloses the utopian, the transformation, and the transdisciplinary and situated knowledges, in other words, a bio-geopolitics of ethics and social change that embraces ways of life that are less harmful to the environment and that involve economic and relational exchanges not based on consumption and utilitarianism.

Although not consensual, the ideas of sustainability and development involve a notion of an ecological subject underlying ecological policies. According to Carvalho (2016), this would be a subject related to a lifestyle oriented towards discourses created within hegemonic power relations, which disregard the environmental possibilities of minority groups and the understanding of the oppression that operates in the structuring of our eco-environmental relationships. On the other hand, Inocêncio and Carvalho (2021) argue that the ecological subject emerges as a historical event and, as a discursive-event effect, can, on one hand, act according to standardized rules determined by a green agenda, being the universal subject of the West, Eurocentric, or US-centered, concerned with environmental issues as long as they do not disturb their accumulating comfort zone or their consumerist character. On the other hand, this subject does not need to be reduced

[...] to a crystallized identity figure, as it can be constructed through practices of freedom sought in contemporary thinking […] and negotiate its own policies and subjective environmental agendas by breaking with normative ecological reiterations

(Inocêncio; Carvalho, 2021, p. 512-513).

This way of conceptualizing the ethos that takes care of and questions itself, in a technology of the self, is an escape from the subjectivations operating in technologies of power – of the order of domination and objectification of individuals and environments (Foucault, 1990).

The deconstruction of the crystallized identity figure through the adoption of practices manufactured within the technologies of power, according to Guattari (2001), involves an ecosophy reinvention that is not univocal but rather indicative of lines of recomposition of human praxis in various individual and collective domains in everyday life. In our view, this process also takes place in struggles for democracy, in the fight against social and environmental poverty, in artistic and social creation, and in the search for alternative singularities that go beyond the realm of stereotypical, reductionist, racist, phallocentric, misogynistic, sexist, developmental, market-oriented, exploitative works or subjectivities.

This guidance can inspire multiple possibilities for environmental education driven by the lines of ecological environments, social relationships, and the resistant subjectivities of integrated global capitalism, decentralizing established power focuses, and economic-subjective productivity. Thus, ecosophy perspectives and praxes seek to integrate what Guattari (2001) broadly referred to as the three ecologies:

a) subjective or mental ecology, which calls for the reinvention of individuals in relation to corporeality, environmental consciousness, the deteriorative and hierarchizing nature of economic imperialism and globalization;

b) social ecology oriented towards collectivity and aimed at deposing predatory human relationships, economic, legal, technical-scientific semiotics, and capitalist subjectification, and overcoming punitive measures directed towards non-hegemonic ecological modes); and

c) environmental ecology aware of human interventions, and the unpredictability of environments, aimed at minimizing the impacts of industrial society and redefining human existence in an ecologically significant way.

From another analytical standpoint, authors focused on the Global South such as Quijano (2005), Santos and Meneses (2009), and Lugones (2008) question utilitarianism, abysmal inequalities, sexist domination, systemic racism, processes of hierarchization/classification of people, economic and ecological control projects, and subjectivities that disqualify populations and knowledge situated outside of Europe or the United States. According to this, the critique of coloniality and the decolonial perspective of environmental education aim to overcome the idea that (under)development born within the processes of colonization and imperialism would turn all peoples into a uniform progressive civility (also white and oppressive) that tames environments for its own benefit. Decolonial thought, therefore, seeks resistance against dominant thinking by reallocating socio-environmental and historical memory for the emergence of knowledge, geographic territories, aesthetics, ethics, politics, and subjectivities free from hierarchies that condemn peoples and places.

When we consider institutionalized environmental education, whether in basic education or higher education, it has often been something ideologically and discursively underlying hidden curricula (Brugger, 1994), guiding individuals as ecological subjects (Inocêncio; Carvalho, 2021). However, it frequently serves the purpose of fulfilling pre-established agendas and promoting homogenizing environmental discourses regarding behaviors, practices, and values.

Curricula and other ecological representations, in the fictionalization (invention) of environmental education, create narratives and identities for these individuals who promote ecologically acceptable but naive modes of behavior. These narratives often focus on individual performance: being efficient in management or planning (with a productive and developmental focus on environmental resource management) or engaging in activities such as planting trees on festive occasions, dressing up as indigenous people, reusing materials, saving energy and water, recycling organic waste, consuming products from the green, biodegradable, or sustainable agenda, and reproducing media discourses – with little or no political confrontation – about how good it is to be natural, to be agro, to be tech, to be pop, etc.

Such practices mask industrialized aspects, the indiscriminate use of fossil fuels or polluting energy sources, the exploitation of commodities, agribusiness (with its monocultures and mono-livestock, dynamics of agrochemicals, and encroachment on lands belonging to indigenous and traditional communities), structural racism, the expropriation of the labor of women and children, the massacre of indigenous peoples, the politics of death directed at Black and/or poor people, the devastation of Latin America, profitability, and the perpetuation of other social inequalities. These actions are approached from a non-ecosophy and abyssal perspective (which widens inequalities), disconnected from reality, and still tied to a hegemonic economic response regarding ecological practices.

Although the green scene can be seen as interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary practice, in a colonized curriculum, it compartmentalizes, alienates, and fragments diverse environmental knowledge and understanding. In our thinking, the counterpoint lies in the adoption of perspectives that bend, deterritorialize3, and decolonize what is established by large corporations or by the environmental education we refer to as the dominant/hegemonic one (the sustainable development advocated by capitalism/neoliberalism, disconnected from situated local knowledge and perpetuated in the school tradition).

Inspired by Deleuze and Guattari (1977), Gallo (2002), and Inocêncio and Oliveira (2021), we state that the breaking in alienating environmental education and technologies of subjectivation and domination would be provided by the adoption of practices of minor environmental education, that is, freer and more diverse practices within the educational realm, those distant from the protocols of macropolitics, untamed by larger official proposals and documents (curricula, laws, rules, precepts, uniformizing and massifying codes of conduct, etc.), but that highlight the political-poetic aspects of those who singularize their activism. This minor approach intersects with the task of decolonizing thinking and exposing the micropolitical production of those who re-exist.

The choice for minor approaches and for lines that abandon or displace established environmental interpretations - within education or in our practices - is signaled in our writing as a cartographic movement. Cartography is the process of absorbing materials from various sources (theoretical, visual, written, cinematic, philosophical, subjective) in order to activate desire, create flows, act politically, and generate counter-devices or counter-powers (Rolnik, 1989).

It is worth mentioning that the cartographic methodology, understood alongside other qualitative research or methodologies within post-critical perspectives in education (Passos; Kastrup; Escóssia, 2009), pertains to subjectivities, agency, multiplicity, and diversity. It does not operate through totalizations or objective arrangements, as if a single reality (or a single history) could extract all the realities (of research, education, history, and socio-environmental contexts). Cartography presupposes a multiple text-agency, composed of different affects, lines of direction or escape, speeds, entry points, and connections. The cartographic map (the research), in this context, aims to accompany open processes and minority actions (such as Black, feminist, LGBTQIA+, Roma, Palestinian, peasant, children’s, anarchic, etc.), considering the micropolitical sphere and the production of subjectivities (Passos; Kastrup; Escóssia, 2009), including those of the researchers themselves. However, this characteristic does not make it any less scientific or invalid.

Thus, cartography, without objecting to or hierarchizing fields of theoretical production or desire (Rolnik, 1989), is also a possibility to decolonize academic thinking, considering data and analyses as clues aggregated to a map that guides the research journey and critique by considering, for instance, multiple knowledges in the research process and connecting results to plural logics (Passos; Barros, 2009). It does not separate being from doing, academic thinking from subjective thinking; cartography is, therefore, a practice of accompanying processes in the agency between subject and object, theory and practice, constituted and open on the plane of experience.

Our interest here is to allow the thoughts to slide based on the clues (or sections written and arranged by the authorship), aiming at a non-hegemonic - minor and decolonial - environmental education. To achieve this, the work incorporates the artistic-activist expressions produced by minority artists and representatives of subalternized peoples within the context of the Anthropocene environmental crisis. Therefore, the first clue is the perception of a non-utilitarian life and minor education as a possibility for curricular agency towards other subjectivities. The map presents the personal aesthetic impressions of the authorship and the propositions of Ailton Krenak, Donna Haraway, Aníbal Quijano, and other authors who directly or indirectly address the situations of coloniality, particularly with the intention to escape a regulatory environmental education and discuss the implications of the Anthropocene and the coloniality of power.

The second section brings forth the works of indigenous artists such as Jaider Esbell, Denilson Baniwa, Daiara Hori, and Úyra Sodoma. Following the cartographic lines, the authorship echoes the voices of minor and decolonial environmental education, relying not on dominant science but on activism to propose the discussion of relational indigenous knowledge, as well as other environmental logics, with the aim of fostering reciprocal relationships with different social and cultural groups.

These clues do not function as a recipe or pre-established sequence of teaching, directed towards a specific series or audience within basic education. Instead, they serve as dismantlable and unfolding actions alongside other non-desiring cartographies of colonial logic, which we refer to as other discussions within Science Education and education for environments. The thought-writing, therefore, highlights the aesthetic power of works that do not claim the label of official environmental education, but operate through liberating and questioning educational practices linked to the knowledge of the Global South.

Thinking Non-Utilitarian Life: Decoloniality as a Minor Proposal in Science Education

Source: Created by Leonardo Bergamo.

Figure 1 Nature demands passage and potency (Digital scan of a photograph)

What kind of environmental education is practiced in science education?

This question, although not intended for an immediate ready-made answer, urges us to ponder the different realities that unfold under the sky. The reality of workers, people from the Global South, marginalized women and men positioned in the trenches of resistance (Maddox, 2021). The reality of students. The reality of banks and corporations. The standardization of all these realities into a single experience aimed at individuals.

Since the invention of Latin America as the subjugated ‘other’ of the Global North (Maddox, 2021), the modern project of imperialist financial institutions has promoted money and exploitable environments, neglecting recognition and support for indigenous peoples. The previous image, captured in the landscape of a university, evokes our thoughts on so many stories that survive the colonialisms of being, knowing, and environments (Quijano, 2005). Colonized projects have relied on tactics of domination to direct gains and profits expropriated from the popular classes, traditional communities, nature, or environments transformed by other, perhaps less totalitarian and profitable, interferences.

In current university spaces, alongside banks and profits, there is also colonization of thought embedded in the processes of education, curricula, or environmental policies, often labeled as clean or ecological. Behind the green facade, entrepreneurship, projects of domination, the formation of a single way of thinking, and a utilitarian mindset are territorialized, justifying any form of environmental exploitation.

In a reverse process, the force of life demands passage and potency. The tree that conceals the bank’s logo should not be seen as secondary. We connect this image to another one created by cartoonist Laerte Coutinho. Laerte’s cartoon (Figure 2) refers us to a mode of resistance against political forces that seek to domesticate bodies and environments, as well as a denial/disobedience to the political-environmental logic fostered in colonial processes that brought the understandings of the white culture to the forefront.

With the invention of America, Eurocentric forms of subjugation or naming of nature were invented. Modernity/coloniality4 brought about transformations in the way environments, plants and animals, and other beings are perceived, categorizing biological life based on productive conditions for the economy. According to Thomas (2010), human dominance is created through a teleological worldview and the subjugation of environments to human domination, the classification and inferiorization of beings. And more than religion, the emergence of private property and monetary economy led to the exploitation of natural and environmental resources.

The image-clues that open this section, in our view, can be interpreted as a non-homogenizing environmental education, one that does not desire the official status of education for itself, but destabilizes, brings the political field of life, provokes thinking, affects, and creates provocations that become environmental educations.

In the science education of traditional curricula, the vision of official environmental education is naturalizing and naive, often restricted to the precepts of textbooks and teaching manuals and to an official discourse of education that becomes a pedagogical device, mostly focused on practices such as recycling, conservation, waste collection, green fairs, and commemorative dates (Inocêncio; Carvalho, 2021). This conception disregards the knowledge of indigenous peoples and the reciprocity in the exchange of knowledge, as it needs, above all, a scientific appeal to be validated as well. It disregards the tree-image covering the economy-image precisely because the second hierarchized world-images and invented an order of importance of things.

In a decolonial approach, environmental education can help suspend the fragmented dimension of ecological understandings and hierarchized world-images where lives/bodies/species are ontologically weighed (Butler, 2001) to the detriment of other lives, especially when it includes different discussions about the environment and incorporates non-hegemonic ethnic, social, and cultural knowledges.

For Stortti and Pereira (2017, p. 16), the starting point of decolonial environmental education is

[...] the recognition of the preexistence of an environmental education practiced and conceived from the realities of the region by social movements, indigenous groups, rural communities, quilombola communities, Afro-Indigenous communities, favelas, urban peripheral movements, and other groups that produce a [counter-hegemonic] struggle for their own mode of production of their own existences. This aspect leads us to the need to expand attention and contextualization to the demands of these movements for socio-environmental justice, as well as the contribution of Latin American thought in political ecology and popular education.

In this recognition, it is necessary to situate that the environmental-humanitarian crisis is a crisis originated within Modernity, primitive accumulation of capital (Quijano, 2005; Ballestrin, 2017; Maddox, 2021), mercantilism, and the marginalization of non-white peoples in processes instituted since the 16th century, with European expansion and colonial advances into other territories around the world. Although it has been conventionally established to mark the history of the ecological crisis from the 1970s, with the perception of resource depletion in industrialized and consumer societies (Inocêncio; Carvalho, 2021), the ecological crisis and the crisis of the environmental subject are not crises of indigenous peoples5.

We do not mean to imply that indigenous peoples are exempt from their own environmental contradictions, but rather to endorse the fact that the socio-environmental relationships developed within these peoples’ contexts do not revolve around indiscriminate consumption. However, it is precisely the indigenous, autochthonous, or descendant populations with their unique ways of life and relational niches (in Africa, the Americas, and Asia) that end up being the biggest victims of environmental destruction and exploitative policies carried out by industries, agribusiness, deregulation of environmental laws, and the epistemic erasure of their knowledge perpetuated by the persistence of colonial logic.

Haraway (2016), on the other hand, identifies this environmental crisis as stemming from the Anthropocene or Capitalocene6. Resulting from imperialism and political-territorial conquests that led to the oppression and subjugation of people and environments, the Anthropocene began with developmentalism and the burning of fossil fuels on a global scale, starting from the Industrial Revolution and the phases of capitalism that unfolded from this event. This marked a juncture in which humanity was recognized as a potentially destructive environmental force. Haraway (2016) warns that we have reached a breakpoint, where the possibility of returning to ecologically healthy life is compromised in the current geological era due to the adverse relationship established between humanity and the environment. The Capitalocene is characterized by global climate, health (as seen in the recent Covid-19 pandemic), and economic changes that bring us closer to the end of the world as we know it, projecting human actions through determinations that generate extreme inequalities (among human species and other species) within the context of capitalist globalization.

The science of understanding and partially changing this end-of-times scenario, in Haraway’s (2016) words, lies in the biocultural-political-technological recomposition that must include empathy in the form of mourning (recognition) for losses and the ability to create kinship (biological, semiotic, social, cultural, and relational) among species. The idea of connections that bend and reshape mononuclear ideologies among human beings (conjugal family, hierarchical positions of authority, patriarchy, etc.), as well as between human beings and other living beings (domination of nature, environmental racism, animal subjectivation and speciesism, among others), is being proposed. Overcoming the Anthropocene aligns with the need to reestablish archetypal connections with environments, but through associations, cooperation, biological and technological evolution, embracing both human and non-human ancestry and otherness.

The indigenous environmentalist Ailton Krenak (2019) also presents ideas for postponing the end of the world, that is, for the restoration of a balanced and non-consumerist ecological relationship. This requires adopting attitudes that consider the ancestral knowledge of indigenous peoples and a logic of non-predatory and non-extractive environmental relations in terms of surplus accumulation. Krenak recommends abandoning capitalist modes of production.

In this sense, it is necessary to question a scientistic culture that disregards other paths of knowledge and labels non-mediated environmental relations by consumption, capitalist economy, and developmentalism as primitive or backward (Brugger, 1994). In this valorization of development and progress, the accumulation of wealth drastically interferes with biodiversity, imposing Western modes of life from the global North as oppressive ways of being incorporated by everyone. Thus, there is a predominance of the coloniality of peoples (Maddox; Carvalho; Maio, 2021) guided by power relations and the subjugation of beings, knowledge, nature, etc. These processes also lead to racialism, that is, the prejudiced classification of peoples who do not follow white or Eurocentric logic and binary ways of thinking about relations with the environment.

According to Krenak (2019), it is necessary to understand the alternative logics of societies that are organized in opposition to the concepts conceived by the State and hegemonic power. From this perspective, it is important to consider that other lives matter and that they adopt minor forms of environmental education, which are sometimes not recognized as positive relationships with the environment or as structured knowledge to guide ecological behaviors. These minor forms of education challenge the capitalist neoliberal model, necropolitics (the letting die as a tactic for population control and the elimination of minority groups), and the ignorance of the planet as a bio-semiotic organism.

In a minor context, Krenak (2020) also becomes a spokesperson for the perspectives of ancestral peoples and provides a counterpoint to the measures adopted by sustainable development discourses. The environmentalist draws our attention to the fact that humanity has become disconnected from the environment, unaware of the origin of food and breathable air, but knows how to go to the market to buy what it desires. On a national level, he warns about the deregulation of environmental legislation and the weakening of protection for indigenous and traditional lands promoted in recent governments, particularly during Jair Bolsonaro’s administration from 2019 to 2022.

The predatory-Western logic in the discourses generated within bolsonarism (environmental destruction, mineral exploitation, indigenous killings, epistemicide of knowledge) does not question whether its products stem from ancestral land theft, land grabbing, toxic soil, or modifications and processes that benefit the industry and other sectors of the economy.

The reversal of this reproductive utilitarian logic lies in evoking the memories of self-preservation of the environment, through procedures that involve other emotions. Building upon Krenak’s perspective, Segato (2018) reminds us that it is time to read the memory of who we are in order to cease being what we are not; it is time to emanate our expropriated and colonized geographic, aesthetic, and ethical territories and to reclaim the knowledge structured in ancestral heritage through the adoption of ecological policies that embrace pluriculturalism.

In acknowledging the colonial environmental contradictions, there is a proposal that short-circuits the economic notion of development or green entrepreneurship and invites us to the provocative potential of thought and creations that resist discourses invented as singular truths or homogeneous ways of practicing, living, and experiencing environmental education.

According to Krenak (2020), giving life and everything we do a utility is a fiction; life is not useful because life is enjoyment, a dance, or, poetically speaking, it is the tree that covers the facade of the bank and the resistance that persists in re-existing even when “the herd is passing”. Life is not useful because it cannot be quantified. And because it is not useful, life is the lesser education.

With the powerful force of the activism of the marginalized, minor environmental education is anchored in the concept of minor literature by Deleuze and Guattari (1977) and in Gallo’s proposition of minor education (2002). A minor literature/education presupposes the deterritorialization/breaking of dominant literature or understanding of the world (precepts, norms, status quo), but it also involves acknowledging non-hegemonic political-discursive powers and collective agencies that activate, mobilize, and value the knowledge of socially invisible groups. Minor environmental education does not mean abandoning legislative aspects or conservation/preservation tactics, nor does it dismiss environmental practices and discussions in schools and universities. Instead, it involves reframing them to encompass otherness, minority groups such as indigenous peoples, women, traditional communities, migrants, among others, subjectivity, the poetics of relationships, and “pedagogies in contexts of struggle and resistance” that can enable “other ways of being, existing, and relating to nature” (Melo; Barzano, 2020, p. 148) and to the environments.

Therefore, minor environmental education does not advocate for the economic/rationalized nature of life. Following Krenak (2020), we can understand it as anticolonialist, antiantropocentric, antiscientific, and antipatriarchal, while being centered on traditional, ancestral, popular, and resilient knowledge from communities that establish symbolic and everyday languages that respect ecosystems. It destabilizes the mode guided by the dominant ecological discourse of the standard ecological subject, which is considered universal and singular. In other words, it challenges the subject captured or influenced by environmental propositions that conform to a single way of living in environments - that of sustainable development governed by global capitalism.

It is worth reiterating that we do not intend to disregard the foundations of sustainability in larger institutional agreements, as they are important for ensuring governmental and non-governmental environmental practices. For example, regulations for environmental protection, land rights, and the establishment of codes of conduct. What we advocate for is the departure from practices dictated by economic, Western, colonized ways of life that do not challenge consumption dynamics and are guided by a superficial green label devoid of the real structures of domination and environmental issues.

Therefore, it is important to embrace a counter-hegemonic, non-cliché, and minor approach to environmental education that values different forms of knowledge. Above all, it should be imbued with an eventful logic – an interaction that escapes standardization but problematizes reality through diverse subjective, ethical, and aesthetic knowledges. In light of this, Inocêncio and Oliveira (2021) suggest the convergence of artistic and activist works that fulfill the role of critiquing predatory environmental relationships normalized in consumer society.

We believe that these guidelines are important for considering pedagogical interventions in Science Education. In addition to the notion of a minor education, a non-utilitarian life or environment, and ideas to postpone the transformations of the Capitalocene, we also rely on the insights of Quijano (2005) and Maddox, Carvalho, and Maio (2021) to advocate for decolonized environmental education practices. This means avoiding the reproduction of the coloniality of power (perpetuating the colonizer’s political logics), the coloniality of being (adopting colonized values at the expense of indigenous ways of being, expropriating the labor force of minority peoples, racialization), the coloniality of knowledge (erasing indigenous knowledges in favor of colonial science and aesthetics), the coloniality of nature (extractivist expropriation of the environment), and the coloniality of gender (subordinating bodies, sexualities, and genders to a classificatory and binary logic).

Therefore, we consider subjective knowledges in constructing pathways that incorporate and make visible indigenous knowledge, especially to foster an environmental education that promotes non-predatory and non-colonialist relationships with the environment.

Possible Eco-Provocations for a Minor and Decolonialist Environmental Education

As we have discussed, environmental education guided by normative policies of ecological conduct and tied to large productive corporations promotes the erasure of specific environmental needs, natural and cultural biodiversity, and the knowledge of minority peoples, including indigenous communities. Our intention is to escape from this larger character of the environmental subject, which corresponds to discourses created to capture it within a politically correct green agency that is nonetheless colonized.

With the idea of minor environmental education, we aim to reverberate other modes of experimentation that cross and shatter, in effects, subjectivity and critical agency, the reproductive mode of capitalism and its economic development relying on resource depletion, ecological and humanitarian crises. This minority, also known as molecular (Deleuze; Guattari, 1977; Gallo, 2002; Inocêncio; Oliveira, 2021), can be understood as a line of escape from hegemonic policies and powers that marginalize minority groups. Thus, from the minor perspective, what matters is the visibility and everyday life of indigenous groups, of the different, of other ways of relating to the environment, which are based on reciprocity and the visibility of other practices.

In contemporary times, we live surrounded by images, signs, representations, and other discourses that turn into visual appeals or pedagogical narratives that also teach/create ways of being. Within culture, these pedagogies either align with or deny the representativeness of differences. Through transgression and micropolitics, molecular revolts, they can materialize as pedagogical powers that facilitate identification and representation of groups that, in their majority, are disposable, erased, depicted in a caricatural manner, or transformed into fetishized commodities of consumption.

Taking advantage of the relationship between science and art, while considering non-dominant knowledge and alternative forms of environmental education, we think of the artistic-activist power of visual artists representing indigenous peoples. We are interested in activating the situated knowledge of these communities in the voice and art of their exponents to understand the aesthetic-political implications of the transformations promoted in the Capitalocene/Anthropocene era.

In order to postpone the ideas of an environmental education complicit in the end of the world or a hegemonic, larger science education that is exempt from critiquing colonial environmental contradictions, we propose image-clues based on history that reclaim the cosmologies of indigenous peoples. These image-clues denounce while presenting alternatives and possibilities for escape from the larger, institutionalized, and colonized approaches.

The eco-proposals presented here do not conform to the idea of fixed planning, nor to the knowledge objectives proposed in mainstream education curricula, such as the National Common Curricular Base (BNCC). The BNCC, based on technical competencies, challenges teaching, learning, and national education in terms of measurable goals and trainable skills, many of which are standardized and undermine ancestral or traditional knowledge. This standardization is specifically driven by economic logic and the reproducibility of that same logic within the school system. The eco-approach we bring intentionally disconnects from recipes and paths to success, but it is part of the exercise of thinking differently from a smaller cartographic position of authorship. The power of their creations or destabilizations of world systems can be glimpsed in the images proposed, or they can serve as provocations activated in different contexts or stages of schooling. They encourage us to contemplate an environmental education that takes place without promoting ecological agendas that are alienated from the multiple realities and histories of Brazil.

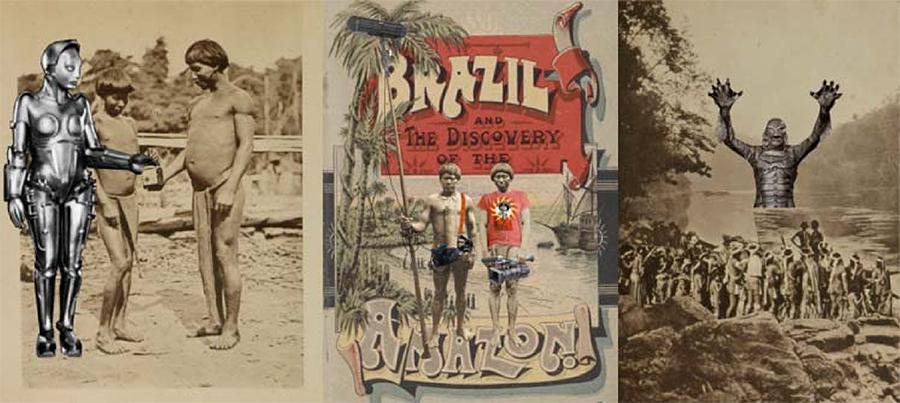

Bringing these realities to light, indigenous visual artist Denilson Baniwa has been creating works that transdisciplinary explore the uses and resources of Western tradition alongside the images and customs of his own people. Denilson’s artworks can be seen as proposals to discuss the rights of indigenous peoples, the impact of the colonial system on history, as well as the current conditions available to indigenous communities regarding acculturation (Figure 3). It is important to note that our colonizers appropriated almost everything, conditioning indigenous cultures to replicate patterns of religion, morality, art, and North-globalist aesthetics (Maddox, 2021).

Source: Baniwa (2022).

Figure 3 Collage featuring images from the series Colonial Fictions (or pretend I’m not here)

We can search for lines of escape from the usual discussion of Brazil’s history of colonization, from the narratives of bandeirantes (explorers) who traversed the interior territories, portrayed as heroes and pioneers, despite leaving traces of murders, feminicides, thefts, expropriations, and environmental devastation due to the extraction of raw materials and political-territorial expansion. These images also contribute to questioning the expeditions of European travelers who created the myth of a lost paradise and untamed nature, prompting us to examine the fauna, flora, and indigenous Amerindian groups scattered throughout Brazil.

The artwork Kahtiri Eõrõ (Mirror of Life) by Tucana indigenous artist Daiara Hori Tukano (Figure 4), presented at the 34th São Paulo Biennial in 2021, also denounces this expropriation by bringing to light the history of stolen Tupinambá mantles from Brazilian indigenous peoples, which were then traded in Europe and currently exhibited in international museum exhibitions as narratives of colonization or fetishizations of indigenous communities (Maddox, 2021).

Daiara’s mantle incorporates a mirror that reflects the audience and transports them to an immemorial space to contemplate themselves within the colonial contradictions and the environmental disintegration of our history, which typically remain hidden in the broader colonialist environmental education.

As we believe, it is through the affectation of our senses that the artistic narratives of Denilson and Daiara can be seen as counter-devices and as a possibility for destabilizing capitalist modes of subjectification regarding our ancestral memory, the idea of the “discovery” of Brazil, the disregard for indigenous tribes, and the forged notion of dependency of these peoples on white founders. They allow for the retelling of the myths of the foundation of “cordial races”, causing a sense of strangeness regarding the invasion of a culture with objects or fictions of the colonizer. It is not a question of a chronological idea of time that fixes coloniality in the past and does not address the imperial oppressions of our time, but rather the transformation of unilateral views disseminated in a traditional environmental education that may even omit our role in terms of usurpations, prejudices, erasures, and discrimination against different indigenous ethnicities, their ways of life, and their artifacts, whose significance is symbolic and connected to environmental cycles rather than monetary value.

Currently, as previously mentioned, the deregulation of indigenous rights takes shape in discourses, laws, campaigns, parliamentary fronts, and incentives for the extermination of indigenous peoples through the arming of militia groups, miners, and agribusiness interests in environmental resources found in conservation units, reserves, and lands inhabited by indigenous communities that contribute to the preservation of biological diversity and diverse knowledge.

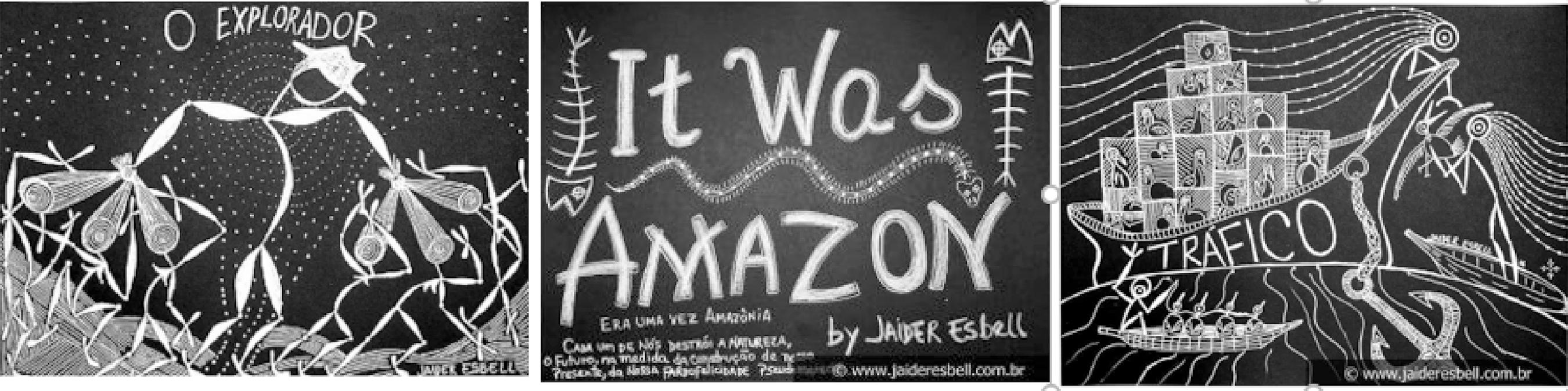

Turning to Jaider Esbell and his denunciation of the extermination that has taken place in Amazonian lands is to move away from naive appeals for the preservation of the tropical biome that do not take into account the histories of settlements, socio-environmental relationships, cultural clashes, and the problems brought by colonizers to indigenous communities. Exploitation, trafficking, alcoholism, rape, and other violations resulting from uncontrolled exploitation and the oppressions of power are denounced in the series Once Upon a Time Amazon (Figure 5).

Jaider brings testimonies of collective experiences with contemporary indigenous art carried out in Roraima. He exposes the communal practices developed with the Xirixana people, inhabitants of the Yanomami Indigenous Reserve in the Amazon rainforest region. Additionally, he showcases various activities with indigenous people from the savannah and mountains, as well as their confrontations with agribusiness sectors. All these elements compose the narrative of an Amazon that is no longer – and never was – the idyllic lost paradise invented by colonizers. Instead, it portrays an Amazon that suffers, as stated by the artist in the image, alongside the words: “Each one of us destroys nature, the Future, to the extent of building our Present, in our pseudo-deserved happiness” (Eisbell, 2016, s. p.).

We suggest that the activation of these images disrupts the Eurocentric and white logic of environmental discussions concerning the Brazilian environmental issue. In another context, when used in environmental education activities within science teaching, activities related to waste and ideas of recycling, reuse, and repurposing are frequently mentioned in textbooks or pedagogical interventions. However, these discussions are disconnected from consumption dynamics and environmental degradation contextualized in relation to poverty, hunger, social inequality, and the intersectional intersections of class, ethnicity, labor, gender, belonging, diverse identities, and identifications. They are more focused on individual and standardizable actions as expectations for changes in the imbalanced socio-environmental framework.

The indigenous biologist and performer Emerson Munduruku, drawing upon the representations of femininities and masculinities associated with the Drag Queen/King universe and the concept of gender as a dynamic of analysis and contestation, utilizes his transformative body to denounce environmental aggressions and the abandonment of forest peoples (Figure 6).

Source: Borges (2019).

Figura 6 Collage with images of performances by Uýra Sodoma (Emerson Munduruku)

Instead of engaging in a consensus-based environmental education, the character Uýra Sodoma transforms herself with organic and inorganic elements to denounce the overexploitation of nature, the impoverishment of her people, and environmental racism. She evokes an alert about the forgetting and devaluation of spaces and places due to the historical racialization of peoples. Furthermore, Uýra, moving her performative body through precarious spaces, exposes the technologies that undermine social and environmental rights, aiming to highlight systemic and endemic diseases, as well as governmental and aesthetic neglect of environments and nature. In these intersections, Uýra causes discomfort regarding our established ecological ways, but also creates kinship and capacity for associations (Haraway, 2016) with other species, gestating an empathetic brotherhood with botanical and zoological elements. She carries within her body the walking forest that denounces the interests of actions driven by capital projects.

Uýra Sodoma (or Emerson Munduruku) can be utilized in teaching and educational activities within environmental settings to problematize the impact of colonialities on genders, particularly in the construction of femininities and the dissonant differences beyond binary frameworks. In environments undermined by market-driven societies, consumerism, and the dominance of a capitalistic perspective, women and LGBTQIA+ individuals from all marginalized groups are often the ones who suffer the most from socio-environmental inequalities. They are bodies that are targeted and at risk of violence in processes of expropriation, requiring systematic attention within curricula and pedagogical proposals. This is necessary to encompass them within an environmental education that challenges gender binarism and the notion of affectivity restricted to heterosexuality, as critiqued by Carvalho and Gonçalves (2021, p. 3):

[...] whiteness, clarity, civilization, the binary order of genders, heterosexuality, sexual difference, conjugality, compartmentalization of organic structures, innatism, the artistic-mathematical perspective, Greco-Roman ideals of beauty, aesthetic schools, the human organicity scrutinized in hierarchies have become more than metaphors and historical contingencies. They have become devices that shape pedagogies to teach us, in a regime of knowledge colonization, how to behave, how to take anatomical-physiological aspects as the basis of our existences, how to establish norms to regulate, train, and standardize bodies, accepting them as civilized, beautiful, and well-educated while erasing dissidences, Blackness, ethnic-cultural groups, sex/gender fluidity, homo-lesbo-bi-sexual affective dynamics, transgender identities, and organic autopoiesis itself. Epistemes of the global North have predominantly determined erasures of the original aesthetics of the Americas, Africa, or Asia, as well as the scientific knowledge of these peoples.

These epistemes have also shaped our anthropocentric and biocentric environmental understanding, which needs to be discussed in schools in order to decolonize the curriculum. It is worth noting that the works and activism presented in our text do not have a utilitarian character. They are rather unfolding, entry points, and debates designed by us for alternative logics and to activate the molecular force of resistance articulations. Therefore, the mentioned guidelines for certain operations, which can be inspiring for science education or other areas of knowledge, are also dismantlable and can be engaged with the creative power of discussions, destabilizing monolithic thinking, and other forms of environmental education that decolonize the curriculum and highlight difference.

Final considerations

We chose to give visibility to artistic productions that, without the hegemonic intention of official environmental education, strive to address ecological and social issues within a non-colonialist framework. In our view, this perspective is important to counteract a broader and reductionist environmental education that excludes marginalized groups and projects itself in a productive and utilitarian manner.

We engage with authors who provide foundations and possibilities that intersect with, for example, science education and art produced in the Global South, mapping an environmental education of molecular order, with knowledge, experiences, and situated wisdom from marginalized groups, positioning them as ecological subjects who are not crystallized by hegemonic ecological discourses and the contradiction of sustainable development. Thus, we think with the echoes of the minority protagonists and proponents of other truths – those whom the normalized way of producing (value, capital, knowledge, environment, or ways of being) segregates to the margins, to the trenches of history.

These minor educations are the triggers that make us think – ecosophically – about societies worn out by market-driven entrepreneurship and productive labor, about necropolitics and governance through the death of marginalized individuals, about environments trapped in ever-increasing and imminent apocalypses. Ultimately, they make us ponder all these problems gestated in the Capitalocene and the sale of a supposed progression of humanity that calls into question the existence of futures for civilization and the planet.

In this context, other perceptions, ecologies, relationships, and sensibilities that postpone the end of the world – that generate empathic cooperation beyond the human – become critical but also poetic, positioning themselves as affectations and shifts in the face of ecological collapses generated by the West.

The presented thought-writing was not only meant to reflect on anthropocentric and Eurocentric ecological actions, that is, actions focused on whiteness as a world system, but to reflect on actions focused on a preservationist and biological idea that defocuses situated socio-environmental relationships. The intention, by bringing subjectivity into the presented criticisms, is to consider that other relationships with environments become visible when we suspend neoliberal truths and policies.

Therefore, we embark on an environmental perspective that values ancestral cosmovisions and the people who resist historical oppressions. In this context, the ideas presented can be connected to other ways of life and thought, in a plural ecosophy relationship that envisions the deterritorialization of the world order, science education, and the curricular order as fabricators of univocal environmental relations.

Notes

1Our goal is not to present a digression of UN conferences on environment problems. For further information on that we recommend reading Tozoni-Reis (2008).

2O’Connor, Martín. On the Misadventures of Capitalist Nature. In: O’Connor, Martín (Ed.). Is Capitalism Sustainable? Political economy and the politics of ecology. New York: The Guilford Press, 1994. P. 125-151.

3Although this text does not aim to discuss in detail the concepts of territory, deterritorialization, and reterritorialization in Deleuzian and Guattarian theorizations (Deleuze; Guattari, 2010), for the purpose of this writing, we can point out that territories (political, geographical, corporeal, conceptual) are established through enunciations and arrangements, many of which are totalitarian, linked to systems of control and subjugation. The movement of deterritorialization, understood as the disruption of discourses and arrangements, operates through the construction of subjectivities and (micro) politics that create lines of flight, diverging from disciplinary impositions and normative enunciations. With this understanding, the environmental discourse - a territory constituted by a hegemonic environmental order, as well as its tactics of control, selection, or exclusion of other ecologically or naturally oriented modes - is deterritorialized, for example, when environmental practices reposition the knowledge of indigenous peoples, traditional communities, peripheral communities, and counter-hegemonic social movements, simultaneously activating other environmental aesthetics and the visibility of discourses that do not require the status of a standardized, universalized, and normative environmental education. Other subjectivities, therefore, reshape the established territories of environmental discourses and reterritorialize themselves, moving within the correlation of forces with intensities, displacements, reinventions, poetics, aesthetics, minor uses, and expansions of environmental education.

4Coloniality refers to different oppressive expressions in politics, economics, the environment, race, gender and epistemology, which were established during Modernity and intensified Global Capitalism (marked by the expansion of mercantilism, bourgeois structuring, and European territorial advances into other continents in the 16th century up to the dominance of imperialism and neoliberalism from today). The coloniality of Eurocentric and U.S. power reaches different forms of control, such as economy, gender, etc. (Quijano, 2005; Ballestrin 2017). Latin activist groups and intellectuals are turning towards epistemologies and practices that decenter them and promote the dialogue of knowledge from local perspectives.

5According to Krenak I2020), the future of scarcity and crisis is not the future envisioned by these peoples.

6There is no consensus regarding the definitions of the Anthropocene and Capitalocene in the scientific literature; exploring all the definitions, which are not always convergent, goes beyond the scope of this article. However, we employ the term Anthropocene as a concept that encompasses human modifications in the biosphere within a very short scale of geological time. These interferences are currently legitimized by the logics of market, consumption, human and environmental expropriation, and contribute to framing global capitalism as an ecological world-system, that is, as a way of conceiving and organizing nature and environments as cheap raw materials exploited by imperialism/colonialism. In this view, environmental collapse (climate change, geomorphological alterations, perpetuation of social inequality and precariousness) should not be attributed to humanity as a whole, but rather to the affluent, socially privileged, and the global North (Moore, 2015). By reinforcing global hierarchies established by modernity projects (North-South, First-Third World, developed-underdeveloped), class (rich-poor), race (white-black), among others, the Capitalocene causes not only ecological extinctions but also geographical, linguistic, and epistemic extinctions, the most intense consequences of which are experienced by populations facing socio-environmental precarity.

REFERENCES

BALLESTRIN, Luciana Maria de Aragão. Modernidade/Colonialidade sem “Imperialidade”? O elo perdido do giro decolonial. Dados, Rio de Janeiro, v. 60, n. 2, p. 505–540, 2017. [ Links ]

BANIWA, Denilson. Ficções Coloniais (ou finjam que não estou aqui). 2022. 12 colagens. Disponível em: https://www.behance.net/gallery/114977861/Ficcoes-Coloniais-%28ou-finjam-que-nao-estou-aqui%29. Acesso em: 10 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

BORGES, Patrícia. Uýra Sodoma mostra ‘corpo e alma’ de Manaus em fotos e vídeos em exposição. Amazonas Atual, Manaus, 26 jul. 2019. Disponível em: https://amazonasatual.com.br/uyra-sodoma-mostra-corpo-e-alma-de-manaus-em-fotos-e-videos-no-largo/. Acesso em: 10 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

BRUGGER, Paula. Educação ou Adestramento Ambiental? Florianópolis: Letras Contemporâneas, 1994. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. Corpos que pesam: sobre os limites discursivos do sexo. In: LOURO, Guacira Lopes (Org.). O Corpo Educado. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2001. P. 151-172. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Isabel Cristina de Moura. Educação Ambiental: a formação do sujeito ecológico. São Paulo: Ed. Cortez, 2016. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Fabiana Aparecida de; GONÇALVES, Cleberson Diego. Subvertendo os Corpos Ensinados em Arte e Biologia: por uma pedagogia relacional. In: SIMPÓSIO INTERNACIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO SEXUAL, 7., 2021, Maringá. Anais […]. Maringá: UEM, 2021. Disponível em: https://bityli.com/rphLRr. Acesso em: 14 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

COUTINHO, Laerte. Sem título. 2022. 1 ilustração. Instagram: @laertegenial. Disponível em: https://www.instagram.com/p/CcfqYOerhWJ/. Acesso em: 10 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Félix. Kafka – por uma literatura menor. Rio de Janeiro: Imago, 1977. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Félix. O que é a Filosofia? São Paulo: Editora 34, 2010. [ Links ]

ESBELL, Jaider. It was Amazon. 2016. 17 ilustrações. Disponível em: http://www.jaideresbell.com.br/site/2016/07/01/it-was-amazon/. Acesso em: 10 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Tecnologias del yo – y otros textos afines. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica, 1990. [ Links ]

GALLO, Sílvio. Em Torno de uma Educação Menor. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, UFRGS, v. 27, n. 2, p. 169-176, jul./dez. 2002. [ Links ]

GUATTARI, Félix. As Três Ecologias. São Paulo: Tupykurimin, 2001. Disponível em: encurtador.com.br/cmrM5. Acesso em: 20 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

HARAWAY, Donna. Antropoceno, Capitaloceno, Plantatonoceno, Chthuluceno: fazendo parênteses. ClimaCom Cultura Científica – pesquisa, jornalismo e arte, São Paulo, Unicamp, n. 5, p. 139-141, 2016. [ Links ]

INOCÊNCIO, Adalberto Ferdnando; CARVALHO, Fabiana Aparecida de. A. O Sujeito Ecológico: objetivação e captura das subjetividades nos dispositivos acontecimentais ambientais. Revista Brasileira de Educação Ambiental, São Paulo, Unifesp, v. 16, n. 5, p. 94-114, 2021. [ Links ]

INOCÊNCIO, Adalberto Ferdnando; OLIVEIRA, Moises Alves. Cartografando uma Educação Ambiental Menor. Revista Eletrônica do Mestrado em Educação Ambiental, Rio Grande, FURG, v. 38, n. 2, p. 94-114, 2021. [ Links ]

KRENAK, Ailton. Ideias para Adiar o Fim do Mundo. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2019. [ Links ]

KRENAK, Ailton. A Vida não é Útil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2020. [ Links ]

LIMA, Tânia Stolze; GOLDMAN, Marcio. Prefácio. In: CLASTRES, Pierre. A Sociedade Contra o Estado. São Paulo: Ubu Editora, 2017. P. 7-20. [ Links ]

LUGONES, Mária. Colonialidad y Género. Tabula Rasa, Bogotá, n. 9, p. 73-101, jul./dez. 2008. [ Links ]

MADDOX, Cleberson Diego Gonçalves. Decolonização do Pensamento em Arte e Educação. 2021. 278 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Centro de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, 2021. [ Links ]

MADDOX, Cleberson Diego Gonçalves; CARVALHO, Fabiana Aparecida de; MAIO, Eliane Rose. Culturas, Artes e “Biologias”: pulverizar os pensares colonizados e marcas outros possíveis para as corpas, os gêneros e as sexualidades que não se dobram. In: ACCORSI, Fernanda; BALISCEI, João Paulo; TAKARA, Samilo. Como pode uma Pedagogia viver Fora da Escola? Estudos sobre pedagogias culturais. Londrina: Syntagma Editores, 2021. P. 237-260. [ Links ]

MELO, André Carneiro; BARZANO, Marco Antonio Leandro. Re-existências e Esperanças: perspectivas decoloniais para se pensar uma Educação Ambiental Quilombola. Ensino, Saúde e Ambiente, Número Especial, p. 147-162, jun. 2020. [ Links ]

MISOCZKY, Maria Ceci; BÖHM, Steffen. Do Desenvolvimento Sustentável à Economia Verde: a constante e acelerada investida do capital sobre a natureza. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, Rio de Janeiro, v. 10, n. 3, p. 546-568, 2012. [ Links ]

MOORE, Jason. Capitalism in the Web of Life: ecology and the accumulation of capital. New York; London: Verso, 2015. [ Links ]

PASSOS, Eduardo; BARROS, Regina Benevides de. A Cartografia como Método de Pesquisa-Intervenção. In: PASSOS, Eduardo; KASTRUP, Virginia; ESCÓSSIA; Liliana da. Pistas do Método da Cartografia: pesquisa-intervenção e produção de subjetividades. Porto Alegre: Solima, 2009. P. 17-31. [ Links ]

PASSOS, Eduardo; KASTRUP, Virginia; ESCÓSSIA; Liliana da. Pistas do Método da Cartografia: pesquisa-intervenção e produção de subjetividades. Porto Alegre: Solima, 2009. [ Links ]

QUIJANO, Aníbal. Colonialidade do Poder, Eurocentrismo e América Latina. In: LANDER, Edgardo. A Colonialidade do Saber: eurocentrismo e ciências sociais. Perspectivas latino-americanas. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2005. [ Links ]

REIGOTA, Marcos Antonio do Santos. Ciências e Sustentabilidade: a contribuição da educação ambiental. Avaliação: Revista de Avaliação da Educação Superior, São Paulo, Unicamp, v. 12, n. 2, p. 219-232, 2007. [ Links ]

ROLNIK, Suely. Cartografia Sentimental: transformações contemporâneas do desejo. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 1989. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa; MENESES, Maria Paula. Epistemologias do Sul. Coimbra: Edições Almedina, 2009. [ Links ]

SEGATO, Rita Laura. La Crítica de la Colonialidad em Ocho Ensayos – y uma antropologia por demanda. Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros, 2018. [ Links ]

STORTTI, Marcelo Aranda; PEREIRA, Celso Sanchez. Reflexões sobre a Educação Ambiental Crítica em um Grupo de Pesquisa: um estudo de caso do GEASUR. Acta Scientiae & Technicae, Rio de Janeiro, UEZO, v. 5, n. 1, p. 15-21, jun. 2017. [ Links ]

THOMAS, Keith. O Homem e o Mundo Natural: mudanças de atitude em relação às plantas e aos animais (1500 – 1800). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2010. [ Links ]

TOZONI-REIS, Marília de Freitas de Campos. Educação Ambiental: natureza, razão e história. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2008. [ Links ]

Received: April 29, 2022; Accepted: March 07, 2023

text in

text in