Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Realidade

versão impressa ISSN 0100-3143versão On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.48 Porto Alegre 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236124169vs01

THEMATIC SECTION: FAUNA, FLORA, OTHER LIVING BEINGS AND ENVIRONMENTS IN SCIENCE AND BIOLOGY EDUCATION

Encounters and Fictions: talking to plants

IInstituto Federal de Santa Catarina (IFSC), Florianópolis/SC – Brazil

Listening to what the plants say in order to talk to them is the proposal that mobilizes the writing of this article. It starts with a problematization about the utilitarian perspective that commonly characterizes the relationship between humans and plants. This relationship is also reproduced in the teaching of botany, when it is often thought from a technical and hierarchical point of view towards plants and other non-humans. Thus, based mainly on repertoires and notions coming from the arts, philosophy and literature, what is sought is to build possibilities for other encounters with plants. Less hierarchical encounters in which it is possible to hear the almost inaudible voice of the plants and talk to them.

Keywords Botany Teaching; Vegetable Turn; Fiction; Plants

Ouvir o que dizem as plantas para com elas conversar é a proposta que mobiliza a escrita deste artigo. Parte-se de uma problematização sobre a perspectiva utilitarista que comumente caracteriza a relação entre humanos e plantas. Relação que se reproduz, também, no ensino de botânica, quando frequentemente pensado a partir de um olhar formativo tecnicista e hierárquico para as plantas e outros não humanos. Assim, baseando-se principalmente em repertórios e noções provenientes das artes, da filosofia e da literatura, o que se busca é construir possibilidades de outros encontros com as plantas. Encontros menos hierárquicos nos quais seja possível escutar a voz quase inaudível das plantas e com elas conversar.

Palavras-chave Ensino de Botânica; Virada Vegetal; Ficção; Plantas

Introduction

It is the third strophe of the poem the flower and its protest, by Adriana Lisboa (2021, p. 31), that triggers the writing of this article: “[…] but what does the flower say / when we don’t borrow it/ for fights, griefs, loves /or metaphors”. The verse, breathed almost like a prophecy (what the flower says), provokes a disconcerting and uncomfortable shudder when we consider that the most common way in which we humans relate to plants is from a utilitarian perspective. However, trying to listen to what the plants say is one of the issues that have animated the proposals I have made to work with teaching botany in high school, in technical courses at a technological institution.

For some time now, the teaching of botany in Educação Básica has been problematized, mainly based on the concept of botanical blindness, proposed by Wandersee and Schussler (2001), which would be something like the inability to see or perceive plants in the environment and, therefore, to recognize their importance in the biosphere. In humans, it would have generated the inability to appreciate the aesthetic and unique characteristics of plants and the anthropocentric and mistaken classification of plants as inferior beings compared to animals. Based on the assumption of botanical blindness, most publications point to the difficulties in working with botany, highlighting the excesses of the scientistic approach (Towata; Ursi; Santos, 2010), the decontextualization (Ursi et al., 2018), the students’ lack of interest (Salatino; Buckeridge, 2016), among others. However, although there is this perception, alternative proposals for teaching botany are mostly still focused on a formative perspective, which mainly takes into account the cognitive, technical and informative dimension.

Thus, as alternatives, what is observed are propositions based on the elaboration of teaching materials, construction of practical classes (Silva; Cavallet; Alquini, 2006), emphasis on the use value (medicinal, cultural and economic) of plants or their ecological importance , usually with a focus on catastrophism1 (Salatino; Buckeridge, 2016). There are few initiatives that operate other references to think about the teaching of botany2. That is, in general, a colonizing, anthropocentric and hierarchical view is still taken in relation to plants.

And here I return to the opening verse: but what does the flower say? More than a poetic question, reflecting on what plants say points to other possible perspectives for teaching botany. Perspectives in which one does not seek to frame plants from references and human cognition, but to experiment with other possible relationships. Perhaps by kinship with them, as Donna Haraway suggests (2016, p. 142):

Making kin is to make persons, not necessarily as individuals or as human beings […] Becoming kin and becoming kind (such as category, care, kin without birth ties, parallel kin, and various other echoes) expands the imagination and can change history.

Kinship relationships in which plants become companions in research and creation, as proposed by Susana Dias, in the conversation circle Forest Breaths– thinking with the plants. (Bellini; Souza; Barbosa; Dias, 2021). Finally, relationships capable of making room for other formative dimensions in biology classes. These dimensions are related to ethical and aesthetic aspects, sensitivity, alterity, estrangement, silence and fiction.

However, being able to hear what plants say presupposes that we are available to trigger other conceptual repertoires when encountering them. Repertoires less imprisoned in the dictates of the biological sciences and more linked to the field of literature, literary studies, anthropology, visual arts, theater and philosophy. Finally, repertoires that propose a reflection capable of making the hierarchical logic in the relationship between humans and non-humans falter.

During biology classes in which plants are the protagonists, I usually invite the students3 to make their bodies available so that they can be crossed by other logics. That they exercise, for a few moments, curbing the incessant need to understand and are prone to feel, remember and risk new ways of entering into relationship with the plant world. In this process, they also allow themselves to explore other ways of narrating encounters and relationships with plants. And, finally, that these modes of narrating may take the form of fictional writing or another artistic medium of your choice (illustration, collage, photography, montage, etc.).

By sharing these examples of teaching action with the world of plants, I give some clues to the course that this text follows. In the next sections, using these repertoires coming from other areas of knowledge, I propose to try a conversation with plants in which they are not borrowed “for fights, griefs, loves /or metaphors” (Lisboa, 2021, p. 31). A conversation where plants can share their stories, echo their voices and where we humans are available to listen to them. A silent and, to some extent, impossible conversation.

Other Whispers: the vegetable turn

Making yourself available to listen to plants presupposes rethinking the way we have been meeting with them. As I have already suggested, risking new ways of relating to the plant world starts, initially, from the willingness to question the inferiority given to plants by western scientific and philosophical thought.

In this sense, although plants still do not have the same status as animals when considering the relationship between humans and non-humans4, an increasing number of researchers have dedicated themselves to rethinking the place of plants in different areas of knowledge. However, as Mancuso (2019 p. 36) suggests, “[…] it is not easy to convince anyone who has always looked at plants as organisms on the edge of inorganic, at best as being good for decorating gardens, that they have extraordinary capacities”. In this attempt, in the scientific field, works on plant cognition by Monica Gagliano (2016), research on neurobiology and plant communication by Stefano Mancuso (2019) and works on how plants sense the world by Daniel Chamovitz (2021) are important. However, although they bring important arguments to dignify the place of plants among living beings, many discussions still remain centered on functionalist and comparative logic. Thus, thinking about plants is finding categories in which research can collect data capable of comparing their biological activity, their relationships and the way in which they interact with the environment, with that of animals.

While the sciences are struggling to find a way to encounter plants without a comparative element, different areas of the humanities seem to be less afraid of risking other approaches to this relationship. A new and exciting field of knowledge about plants has emerged in recent years and has been called, in the field of arts and philosophy, the vegetal turn (Vianna, 2021).

Philosopher Michael Marder began studying the philosophy of plant life when he realized that the animal studies in vogue often began with highly individualized animals: “[…] when ‘interspecies ethics’ strove to create a community of living beings larger than the human one, it did not take into account hyenas, mosquitoes, or any variety of plants” (Marder, 2015, p. 2). Thus, her research is dedicated to reconceptualizing the place of plants in the history of Western philosophy and reconfigure an ontology of plant life that fits plant temporalities, freedom and way of relating to the world (Marder, 2015). In this proposal to rethink the place of plants and our relationship with them, one of the provocations posed by Marder, in a debate with the Chilean playwright Manuela Infante, is that recognizing plants as a valid other and, also, starting to recognize the another vegetable that exists in us (Infante; Marder, 2020).

In this sense, perhaps Emanuele Coccia is the one who brings a more radical contribution to the way of thinking about the presence of plants in contemporary philosophical thought. Much of his work is related to the cosmogonic power of plants. For him, the notion of the world and being-in-the-world is described through the continuous work of craftsmanship carried out by plants on the planet. Starting from physiological, structural aspects and the ways in which plants constituted and relate to the environment, Coccia (2018a, p. 5) proposes to rethink the way we look at them:

It is the plants that make a world out of the matter and space that surround us, that reorganize and rearrange reality, making it a habitable and livable place. The world, from this point of view, is above all a vegetable reality: it is a garden before being a zoo, and it is only because it is a garden that we can live there. […] Being in the world means for us humans to be condemned to nourish ourselves with what plant life has been able to do from the sun and soil, water and air that make up our world.

One of the central points of this being-in-the-world landscaped by plants is the experience of breath. Over the millions of years, the increase in the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere, as a result of the alchemy carried out by the process of photosynthesis in plants, was what allowed life to reproduce and share the same phenomenon of breathing: “[…] blowing, breathing, in fact means having this experience: what contains us, the air, becomes content in us, and, conversely, what was contained in us, becomes what contains us” (Coccia, 2018b, p. 17). In this sense, we do not inhabit the earth, but the atmosphere, that cosmic fluid that makes life possible. Thus, the atmosphere is a place of encounter, a mixture, precisely through breath: “[…] if things form a world, it’s because they mix without losing their identity. […] Mixing without merging means sharing the same breath” (Coccia, 2018b, p. 54).

The notion of breath, here, seems to be an important clue in the sense of listening to what the plants say. Sharing the same breath necessarily means being affected by the permanent changes that other forms of life have made in nature and participating, with plants, in the act of bricolage in the composition of the cultural product that is the world:

Thinking of the world as a garden where gardeners are the plants themselves means, above all, claiming its status as an artifact: the world itself has nothing purely natural, in the sense that nature would be a priori, given in advance; he finds himself, on the contrary, on the threshold of indistinction between nature and culture. It is a cultural product of living beings, and not just the condition for the possibility of life. […] Cosmology is a gardening treatise: a manual on the innumerable ways of managing the most disparate beings and harmonizing their rhythms and breaths

(Coccia, 2018a, p. 9).

Although science and contemporary philosophy are only now realizing the need to rethink the relationship with non-humans and especially with plants, in the narratives of different native indigenous peoples, this relationship is established based on sharing the world, without asymmetric positions.

This is what the indigenous philosopher Ailton Krenak (2019, p. 17) refers to, when he says: “[...] I don’t understand where there is anything that is not nature. Everything is nature. The cosmos is nature. All I can think about is nature”. He exemplifies this perspective of integration by citing the relationship that some indigenous peoples of the Andes establish with the mountains. For them, the mountains form couples: “[…] there is a father, mother, son, there is a mountain family that exchanges affection, makes exchanges. And the people who live in these valleys make feasts for these mountains, they give food, they give gifts, they receive gifts from the mountains” (Krenak, 2019, p. 19).

Bruce Albert, an anthropologist who has lived with and researched the Yanomami people for several decades, says that they: “[…] maintain a constant dialogue with the multiplicity of voices from the forest. Listening to the forest biophony is a matter of constant attention; they are always quick with sound mimicry in response to their non-human interlocutors” (Albert, 2018, s. p.).

This dialogue with the voices of the forest is also present in the reports of the Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa, in his book The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman (Kopenawa; Albert, 2015), when he talks about the corner trees, called amoa hi. These are very large trees, covered with shiny down. Its trunks are covered by innumerable lips that move constantly and from which beautiful songs emerge uninterruptedly. The words of these trees never repeat themselves. The xapiri, spirits that animate the shamans, “[…] listen to these amoa hi trees very carefully. The sound of your words penetrates them and becomes fixed in their thinking” (Kopenawa; Albert, 2015, p. 114). These sounds, learned by the xapiri from the trees, are sung by shamans during shamanic ceremonies and funeral parties where the abundance of ceremonial food from their plantations is celebrated (cassava cakes, banana stews, pupunha fruit juice) and animals hunted and smoked for the occasion.

This other logic in the relationship with plants and non-humans is what characterizes the way in which indigenous thought understands and experiences the world. However, it still comes to us as a distant, barely audible whisper. This is what Krenak (2019, p. 19) problematizes when he asks: “Why do these narratives not excite us? Why are they being forgotten and erased in favor of a globalizing, superficial narrative that wants to tell the same story to us?”.

Enthusiasm with other narratives that can teach us how to make us capable of listening to plants and, in the encounter with them, recognize what is vegetal in us. Here are some of the paths that the notion of the plant turn can bring to animate our way of perceiving plants and the way in which they are invited to compose the teaching of biology in Educação Básica5.

Pollinating Plant Encounters

The chords on the piano invade the room. They are intense sounds, similar to a traditional concert, but, little by little, they start to generate confusion. They don’t seem to follow a metric and rhythm that we are used to. It could be defined as experimental music. At the same time, printed images are scattered throughout the space. They are photographs showing bodies of women dressed in huge leaves of different plants, photomontages in which female faces overlap with plants, giving rise to a hybrid being: human, non-human and phytotypes in which illustrations and images are printed directly onto plant leaves. In the background on the wall, a video is projected and there are headphones with which to listen; the image is of a stage on which there is a table full of pots with plants. A green light invades the space, there is also a soft electronic sound. A woman walks in awkwardly. Her body has jerky movements, restrained steps. She groans, laughs, hugs the plants, rubs her body against them. They talk. There are other artifacts scattered around the space: clippings with literary passages, small sticks, dry leaves of different species of plants. The room becomes like an improvised art installation. Plants speak.

The scenario above describes the space of a classroom that was all twisted, disassembled and reconstituted. Chairs stacked in the middle, others pushed into the corner. The bodies, upon entering, feel confused: where am I going? This description exemplifies one of the several proposals made to start the pedagogical work with the teaching of botany in high school classes in which I work. Launching a proposal like this, which opens up like a tear in relation to what appears in the official curriculum, can be a risk. Mainly due to the fact that it does not only presuppose an introduction to the content, a passing moment in the pedagogical work, as it often happens when using an image, a poem or some artistic artifact to start the work with a certain content. The artifact functioning only as a distant echo. An introductory tool, disconnected from everything that will be presented, discussed and proposed in the sequence.

Building pedagogical practices that seek to listen to what the plants say means being available to open fissures that continue to erase and root in the terrain of traditional syllabuses and the usual methodologies of biology teaching. Mancuso (2019 p. 31) says that a fundamental characteristic of root apexes is “[…] their ability to find a way to grow even in very resistant materials. Despite their fragile appearance and delicate structure, they are capable of […] breaking through even the most solid rock”. The plant metaphor here is not just a pun, but is based on this incredible characteristic of the roots to think about the clash between pedagogical proposals like this one – which intend to trigger other encounters with non-humans, especially with plants – and the historically and culturally constructed school curriculum, in which the hardness of reason and cognition contaminates the study and encounter with non-humans, disregarding their mysteries and subjectivities so inapprehensible to us, human animals.

Fabíola Fonseca, in the powerful workshop Sexual Strategies of Plants6, speaks of pollination as a gesture in which plants and insects get together. For her, it is in the encounter that beings are constituted, build a universe. In this sense, in evolutionary history, the perspective of the encounter would be a revolutionary act, as it changes the individual history of each one. Thus, there is no existence in itself, only in the encounter, since it is the condition for the possibility of an insect to constitute itself as a pollinating being. The encounter as an extraordinary and infraordinary act that mobilizes changes, always a process and incompleteness: small happiness.

During the workshop, Fabiola suggests that the model of society we live in tries systematically to undo the power of encounters, consequently weakening their conditions of possibility. I associate this with the virtualization of relationships, the acceleration of time and the extinction of pauses, silences, the possibility of estrangement and listening. The weakening of the possibility of encounters happens in a similar way in the teaching of biology, and especially botany. When the perspective of the meeting presupposes order, precision of concepts and the power of classification, there is a need for a teaching gesture that is insistently explanatory and that controls the knowledge circulating in pedagogical practices, leaving few spaces for unusual encounters in the classroom. As a result, teaching focused on collective creation and narrative invention is demobilized. So, how to populate the space of relations between students and the contents and pedagogical practices that are so deserted? How to populate encounters?

For some time now, I have been investing in ways of thinking about education and the teaching of biology based on formative gestures that point to everyday life, to what comes from the [inevitably unpredictable] encounter with the other, be it human or plant. Echoing what Fabíola Fonseca suggests, in the performance-conference called Secalharidade (2012), the artist João Fiadeiro and the anthropologist Fernanda Eugênio say that “The encounter is a wound” (Fiadeiro; Eugenio, 2019). And, if we really want to build practices with the other, signaling other worlds and other ways of living together, this wound must remain open, porous.

Keeping the wound of encounters open is a great challenge and it means keeping ourselves – as well, teachers – porous and porous to the encounter. Available for what arrives from everyday life and prone and prone to promote encounters between this everyday life, sometimes unusual, and the scientific knowledge proposed as curriculum and content. That is, it means paying attention to the repertoires that we are operating in order to think about pedagogical practices. Allowing our repertoires to be infected and contaminated by simple encounters, sometimes banal and improbable, is perhaps an interesting whisper in the sense of propitiating other encounters in the teaching of biology. Plants speak...

In the classroom scenario that opened this section of the text, none of the artifacts described refer to any topic present in the curricular proposal regarding the teaching of botany. The sound that invades the classroom is the result of the Years project, by the German artist Bartholomäus Traubeck (2011). In it, Bartholomäus uses cross-sections of the trunk of different tree species to produce sounds. They are like vinyl records made from trees. Each tree’s growth rings are read by a sensor and analyzed for color, thickness and growth rate. This data serves as the basis for a generative process in which algorithms produce piano music. Each tree species produces a different song according to the information present in its growth rings.

The photographs dispersed throughout the space are Hoja Elegante, from 1998, and Corazón, from 20077, and show naked women who have parts of their bodies covered by huge leaves. They are works by Mexican photographer Flor Garduño. At the opening of his book Bestiarium, Garduño (1993) says: “[…] we all entered this world with an animal brother, a double creature, a twin in the forest”. Plants, water, wind and all the elements that formed the world are present in the aura of her images, which intertwine the body of the Earth and the women who inhabit it.

If in Flor Garduño’s photographs women are dressed in leaves, in the photomontages of the series Jardins (Gardens), by Brazilian artist Fran Favero (2017), women and plants mix, becoming a unique being. The series is based on appropriations of images found by the artist at antiques fairs in the city of São Paulo. In them, women can be seen posing in the gardens of their homes. The photomontages produced subvert the narratives of security and beauty of domesticity, inserting layers of estrangement into these representations and bringing contributions to think about the representation of the female body.

Phytotypes and anthotypes are impressions that use plant pigments from leaves so that images appear on the body of the leaves (phytotypes) or on sheets of paper previously sensitized with pigments extracted from leaves (anthotypes). The project Desfazendo Invisíveis: as mulheres naturalistas e suas obras em impressões fotográficas experimentais de fitotipia e antotipia, (Undoing Invisibles: naturalist women and their works in experimental photographic prints of phytotype and anthotype) for example, it was carried out with technical high school students and it produced numerous phytotype and anthotype experiences. As a result of the project, a book of the same name was published, edited by Silveira and Piovezan (2021).

The video projection is an excerpt from the theatrical show Estado Vegetal (Vegetal State) (2019), written and directed by Manuela Infante with the actress Marcela Salinas. The work’s conception revolves around the impossible dialogue between humans and plants. Inspired by the work of Michael Marder and Stefano Mancuso, the show seeks to investigate new concepts such as plant intelligence, vegetative soul or plant communication and their influence on creative processes. In addition to these materials, there are also some excerpts from literary works that will be presented in the next section, small sticks that made up the work Relicário de Pequenas Vidas (Little Lives Reliquary) (Silveira, 2020) and dry leaves: whispers of plants unintentionally collected during walks around the city. Let the plants speak…

In addition to providing unpredictable and unexpected encounters in the classroom, the presence of these artifacts composing the pedagogical practice points to another political dimension that has permeated my way of thinking about education and the teaching of biology: the constant presence of art. Not only art as a tool operating at the service of “teaching of”, but also as a conceptual, theoretical, compositional intercessor. Operating with art means having it on an equal footing in relation to any theoretical references that may support research and practices. Thus, the chosen artifacts described above do not function only as a place from which examples emerge that affirm scientific concepts, but rather as intercessors from which plants can be found in a fictional dimension, with their own narratives. In addition, they have the power to “tear up the clichés” (Didi-Huberman, 2017, p. 101) that are often crystallized in biology teaching due to the consistency and intensity of scientific concepts. Plants speak...

Talking to Plants: Composing Fictions

I believe that by now, the invitation and provocation to create an availability that allows listening to the plants is already evident. However, beyond listening, the possibility of entering into dialogue with them presupposes more ruptures in relation to the usual ways in which we encounter the plant world.

In an instigating article, Patricia Vieira (2015) suggests that the stories of plants that most fascinate humans are not those related to the pragmatics of survival. In fact, our desire has always been to know their most intimate and hermetic secrets, in order to penetrate into the core of the plant being. However hard we try, plant stories will always elude us, as our relationship with flora is necessarily mediated by human sensory perception, scientific knowledge, and an extensive cultural history (Vieira, 2015). This impossibility, however, does not explain the separation of plants and humans into different spheres of life. Finally, she raises a question that has accompanied this text: “[…] how to decipher the mute language of plants and delve into their stories?”8 (Vieira, 2015, p. 4).

This question seems to be a limit in the attempt to approach plants and find ways to establish a conversation with them. In other words, how can we listen to what the plants say in order to talk to them, without falling into the trap of dominating, possessing them? Manuela Infante also poses this challenge in conversation with the philosopher Michael Marder. Reflecting on her research in relation to non-humans and plants for the construction of the show Estado Vegetal (2019), she says that at a certain point she begins to question herself politically and methodologically about the idea of representing the other or speaking for the other. How to build a theatrical show in which the principle is to talk to the plants and not represent them (theatrically and politically)? Likewise, is it possible to question how to propose pedagogical practices in which the principle is to talk to plants and not represent, possess, dominate them?

In her essay Poéticas do Animal (Animal Poetics), Maria Esther Maciel (2011) suggests something that is a clue to reflect on how to overcome this limit in relation to plants. She says that “[…] thinking, imagining and writing the animal can only be understood as an experience that resides at the limits of language, where the approximation between the human and non-human worlds becomes viable” (Maciel, 2011, p. 94). This limit would be poetry, literature and art. Spaces that would allow us to establish less hierarchical encounters with non-humans. “Poetry always leaves a remainder, a trail of knowledge” (Maciel, 2011, p. 94) about that very other, the plant.

It is also thinking about ways of encountering and dialoguing with plants beyond representation and cognition that Patricia Vieira proposes the notion of phytographia. Based on the concept of inscription, by Jacques Derrida, it is suggested that all beings leave marks of themselves in the environment and in the existence of those around them (Vieira, 2015). The inscription of plants is mainly related to their physical characteristics and biological functions, which shape both the contours of a landscape, such as a tropical forest as opposed to a savannah, and their relationship with other beings, for example, photosynthesis that makes life on the planet possible or the color of a flower that invites a particular pollinator. However, in addition to these powerful inscriptions that refer to a biological dimension of the relationship between plants, the environment and other living beings, Vieira (2015, p. 208) puts in the foreground the “[...] specific ways in which the word vegetable is inserted in human cultural productions”9, something named by her as phytographia.

Reflecting on the literature produced about the Amazon, she discusses how plants leave marks, vestiges and traces of their presence in the literary texts themselves. Phytographia would be the encounter between writings about plants and writings by plants, which are inscribed in human texts. In its most basic form, throughout history this inscription was based on material substrates coming from plants that made their traces available in human texts: papyrus, pencil, vegetable inks, paper and countless other supports for writing. However, what Patrícia Vieira calls phytographia represents something more restricted. It would be “[…] the literary portrait of the plants that owes both to the ingenuity of the author who elaborates the text and to the inscription of the plants in that same process of creation”10 (Vieira, 2015, p. 215). Literature enabling communication: functioning as an aesthetic mediator in the encounter between human, body, authorship and plant world.

Thinking of literature and art as mediators capable of providing opportunities for encounter and conversation between humans and plants presupposes thinking about the role of fiction and creation as central elements that put into operation a narrative regime different from that operated by scientific discourse. In an article in which he discusses the power of fiction in the face of current knowledge and the dominant forms of rationality in explaining the world, Eduardo Pellejero (2016) considers that, far from opposing reality, fiction interferes with reality, serving a purpose that is not part of reality. In this sense, there would not be an opposition between fiction and what is considered true. That is, the principle of fiction would not be to expose fantasies, beliefs, illusions or ideologies, but to give a specific treatment to the world. Not an opposite treatment to that given by the narratives that seek the truth, but a differential treatment.

In his article, Pellejero dialogues with Argentine writer and essayist Juan José Saer. In a powerful essay in which he problematizes fiction in the face of what is considered truth and would be closer to the discourses of science, historical praxis and philosophical reflection, Saer (2014, p. 11) says that:

[…] fictions are not written to avoid, due to immaturity or irresponsibility, the rigors that the treatment of ‘truth’ demands, but precisely to highlight the complex character of the situation, a complex character that, when it appears limited to the verifiable, implies an abusive reduction and an impoverishment of reality. By taking a leap into the unverifiable, fiction infinitely multiplies the possibilities of treatment11.

Fiction (and fictional narrative) is perhaps the possible meeting place between human subjectivity and the elusive, elusive and almost evanescent subjectivities of plants. It is in this space that we become capable of, listening to the plants, entering into dialogue, conversation and exchange with them. This possibility is also due to the freedom that one has in the fictional terrain to occupy and expand the margins of what is conventionally accepted as “correct” acceptable explanations for the world. This is what Pellejero (2016, p. 27) refers to when he says that:

[…] fiction presupposes a differential attitude towards prevailing knowledge, towards instituted truths, towards the dominant forms of rationality. […] Making a series of possible worlds proliferate, that is, changing the representations of what we tend to call the real world, putting culture to the test, opening ourselves to the incandescent multiplicity of existence, without preconceived images of knowledge, truth or a reason to conquer.

Proliferating and inhabiting the countless possible worlds that fiction makes possible is also a transgressive gesture. Especially when it comes to occupy a space that is sometimes so averse to disorders, misconfigurations and changes, such as the classroom. When describing the realization of the seminar A Nau Incendiária da Ficção (The Fireship of Fiction.) Leandro Belinaso Guimarães (2019, p. 47) suggests that “[...] the movement of fiction as transgression frees, who knows, our existence from the scandalous, the subversive and all that that can be animated by the power of the negative. Life is affirmed in every beginning, in every perforated limit”. This is how literary texts where plants speak come to compose pedagogical practices, affirming new beginnings and continually perforating the limits that define the teaching of botany with the writing of fictional texts with plants.

Impatiens parviflora, for example, which occupies one of the pages of the Pequena Enciclopédia de Seres Comuns (Small Encyclopedia of Common Beings), by Maria Esther Maciel (2021, p. 31):

Some people call her ‘little kiss’. Despite its grace, it is considered a weed, for harming other species with its daring nature. It grows in flowerbeds, stretches of roads, pots and planters, without containing its impatient desire to be present in all paths. On certain nights, though, she likes to be alone.

Crossed by countless encounters with human culture, when talking to Impatiens parviflora it leaves countless vacuoles of silence where it is possible to enter into dialogue with its everyday and prosaic plant life. Silences that give rise to spaces for conversations. How could a fictional text evoke the daring nature of Impatiens parviflora be? What characteristics of yours could be used to build a daring narrative? Perhaps this desire to be present in all ways? Would she be a traveler with the dream of exploring the world? Or, what is behind this desire to be alone on certain nights?

In the beautiful novel by Alejandro Zambra (2013), The Private Life of Trees (A Vida Privada das Árvores), there is a moment when the conversation between the oak, the poplar and the baobab is told. The three trees discuss the misfortune of the oak tree, which had its skin broken by two people carving their names as proof of friendship: “[…] no one has the right to get a tattoo without their consent, opines the poplar, and the baobab is even more emphatic: the oak was the victim of a regrettable act of vandalism” (Zambra, 2013, p. 14).

In this part of the text, the trees talk and tell about their lives, their daily lives, their ways of thinking. Where could the conversation between the three of them follow?

Yeonghye is the protagonist of the disturbing novel The Vegetarian (A Vegetariana) by South Korean writer Han Kang (2018). The book tells the story of this ordinary woman, who at a certain point decides to stop eating meat. From there, the path of the protagonist begins, who goes on to carry out a somber vegetable metamorphosis. In a spiral of madness and loss, little by little she ends up in a psychiatric hospital with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. In this novel, plants demonstrate all their complexity and sphericity12 as characters. It’s like the creepy whisper of a tree that comes when the sister goes to visit Yeonghye in the hospital:

While waiting for the doctor, as usual he watches the zelcova in the middle of the hospital courtyard. It’s an old tree, must be at least four hundred years old. On clear days, that tree, stretching out its numerous branches and reflecting the sunlight, seems to want to say something to her. But today, on a rainy day, he’s like a taciturn person who doesn’t want to talk. The bark of its old trunk is sodden and dark as night; the leaves of the thinnest branches tremble in the rain. She contemplates this landscape, over which Yeonghye’s image is superimposed, like a ghost

(Kang, 2018, p. 128).

On that same visit, the sister finds Yeonghye at the height of her maddening metamorphosis process, upside down, arms resting on the ground and legs in the air. Her face was all red from the concentration of blood. The nurse says she has been in that position for over thirty minutes. With very lively eyes, she aims at some fixed point in the void. The tormented sister pushes Yeonghye who slowly falls. Only when she returns to her upright position does she begin to talk, as if awakening from a dream:

I thought the trees stood tall. But now I understand. All of them are upside down, with their hands on the ground. […] Do you know how I discovered this? It was during a dream: I was upside down and my body was growing leaves, and my hands were sprouting roots. The roots were piercing the earth, deeper and deeper… I felt that a flower was going to be born between my legs and I opened them, I opened my legs wide…

(Kang, 2018, p. 140).

To become another, to become a plant. Yeonghye’s fictional metamorphosis finds similarities with the biographical narrative of Listen to the Beasts (Escute as Feras) a book by French anthropologist Nastassja Martin (2021). In it, Nastassja narrates her trajectory after encountering a brown bear during a survey she carried out with some Even families13. It is there that Nastassja and the bear meet. Meeting between a bear and a woman. It is also there that the bear chews the anthropologist’s face, but leaves her alive, as she too, with an instrument for walking on ice, manages to defend herself and injure the animal. In the book, Nastassja narrates the unfolding of this limiting event. How to signify this experience? How to define your limits after looking into the eyes of the beast, having metamorphosed, bringing something of that animality inside? To have finally become a little bear and started to dream. There are resonances between becoming a bear and becoming a plant. Nastassja recounts details of her recovery, the inadequacy of returning to that former world, the city, the people who stare at her in amazement at the scar on her face and neck. At one point she says:

[…] the event is not: a bear attacks a French anthropologist […]. The event is: a bear and a woman meet and the boundaries between the worlds implode. Not just the physical limits between a human and an animal that, when confronted, open cracks in the body and head. It is also the time of myth that meets reality; the former that meets the current; the dream that finds the incarnate […]. What does it mean to leave the abyss where the indistinct reigns, to choose to rebuild other boundaries with the help of new materials found deep within the undifferentiated night of dreams? Deep inside the gaping mouth of someone other than you?

(Martin, 2021, p. 97-98).

Back to Yeonghye: what would the writing of this process look like? How would a human-plant hybrid or a human who becomes a plant write? The poetry Jardim Francês (French Garden) by Ana Martins Marques (2022, p. 8), published in the beautiful project Arvoressências, by Mauricio Vieira, gives a clue on how to sculpt a plant:

Sculpt me

like one

hedge

erect myself

severe and symmetrical

build me around

of a palace (empty)

or just sew me up

around

of the bull.

Another clue in the attempt to find a writing or record capable of hybridizing human-plant or talking to the plant world without dominating it and weakening its constitutive power would be the one shared by Manuela Infante. In the conversation with Michael Marder, narrating about the research for the constitution of the show Estado Vegetal (Vegetal State) (2019), she suggests that a methodological path found, instead of speaking for the plants, was to try to discover what was vegetal in them, in order to, with that, amplify this plant behavior in the theater (Infante; Marder, 2020). Thus, the show is built on the ability to report in a branched way, on the emulation of modular thinking, on the questioning of individuality, in an attempt not to perceive oneself as one, but as a being full of others. These are the plant’s own competences.

Finally, there is an element that runs through all the plant narratives presented here and is echoed in their almost transparent voices. That element is the detail. It is the detail that enhances and intensifies the vegetal voices. That allows you to see subtleties invisible to everyday inattention. It is the details that color the encounter with the plants and allow the writing and recording of these encounters with the density they request. In his book How Fiction Works, James Wood (2017) devotes a chapter to detail. At one point he says that “[…] in life and in literature, we sail through the star of details. We use detail to focus, to record an impression, to remember. We cling to it” (Wood, 2017, p. 70). However, Wood points out a difference between detail in life and in literature: “[…] literature is different from life because life is full of details, but in an amorphous way, and it rarely leads us to them, while literature teaches us to notice [the detail]” (Wood, 2017, p. 70). Find, in the details, possible paths in this listening and conversation with the plants, is perhaps fundamental in order not to fall into the trap of following an essentially human logic, domineering and distanced in the relationship with them.

Here it is already possible to rehearse an exit gesture. A final gesture, which can still leave a silence for the plants to speak (but what does the flower say?) and so that, once again, they can whisper all their power in generously suggesting other possibilities for the teaching of botany. Possibilities capable of bringing forth these formative dimensions related to authorship, creation, imagination, ethics and aesthetics, commonly so far from the classroom. The artifacts below are some of those produced by technical high school students, based on different pedagogical proposals, carried out in the period between 2014 and 2022, involving this availability of listening and conversation with plants. They are the result that it is possible to enter into relationship with plants and pollinate other encounters. It is possible to make kinship and indulge in other forms of narrating in the classroom. It is possible, finally, to talk to the plants. I hope that the readers of this text will be able to listen to these conversations.

First Conversation: backyard

As the morning wore on

She grew

White with yellow stalk

On the edge of a creek

At the back of my fortress

After lunch

Where I gave up grandmother’s cutlery

I finally found myself alone

Me and them

Masterpieces of my banquets

Colors of my backyard

‘Excuse me, Miss Nature,

can I have a Calla Lily?’

‘Of course, my daughter, take one too

some fresh moss!’

How kind, right?

She never denied

Third Conversation: iron balance and plant listening

[…] I once got an iron swing. He was really beautiful, an intense dark blue. But I had nowhere to put it, as the trees in my house would not support my weight and his together. In the neighboring land there was a beautiful and strong tree, and as my father took care of it, he asked the owner to let him put my swing on that tree. […] I always talked to the tree and even though it never answered me, I loved talking to it. I would tell him about my day, what I liked to do and even some secrets. He wrote with stones on his trunk and even made drawings on it. That, without a doubt, was my favorite place. One day, when I went there to play after lunch, my swing was no longer on the tree. I thought it was strange and went to find out from my father what had happened. That’s how I got the news that the land had been sold and the new owner didn’t want my swing or the tree there. That day I not only lost my favorite place in the world, but also my best listener. It was three years of friendship and today I am 17 years old and I still talk to flowers, trees and objects around me. I admit that to anyone who asks me, after all, trees are great for keeping secrets and also for making us think, after all, if we don’t get an answer, we have to look for it

(Student C, 2019).

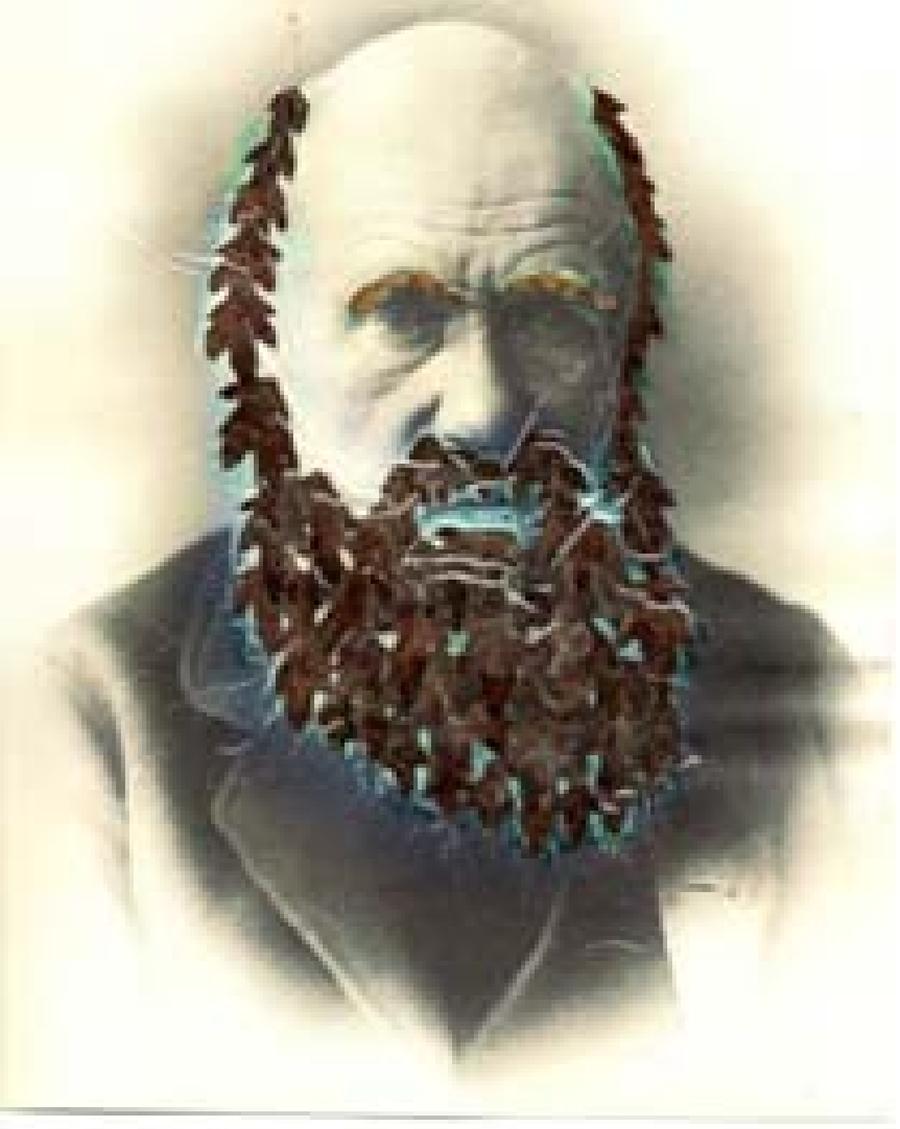

Fourth Conversation: composing botanical faces

Charles Darwin wrote at least five books about plants. In them, he cataloged many species and I believe that because of this we know a good part of what is currently known about plants. Therefore, his beard and eyebrows were decorated with plants

(Student D, 2019).

Joseph Bank was an English naturalist responsible for cataloging about 1300 species of plants in 110 genera. Therefore, he was related to plants having his hair and eyebrows decorated with petals and leaves (Student E, 2015).

Lineu was responsible for cataloging and even naming several plants, so I decided to relate him to them by decorating his eyebrows and hair with flower petals and leaves (Student E, 2015).

Fifth Conversation: metamorphosis

I dreamed. I wanted to become a plant. I picked the perfect spot, and there I stopped on my feet. I planted myself. My toes felt the ground, and seeking its immensity they grew, branched out. I couldn’t leave the place anymore. But she was satisfied. I stretched my arms looking for the sun. And just like the toes, the fingers of the hands stretched out. I became great. At the tip of my fingers sprouted leaves, I felt proud. I felt the chlorophyll in my veins. I didn’t breathe through my lungs anymore, but I didn’t miss that. Standing still, soaking up the sun’s rays. I felt accomplished. The sun went down and for a moment I worried. But then drops touched me. They ran down my leaves, my branches, my trunk. They reached the ground and he absorbed them. And my roots felt the water. The liquid of life. And just when I thought there was no way I could feel happier, I felt something different sprouting at the ends of my branches. Flowers. Beautiful and delicate flowers. And when the sun came back, it brought bees with it. They, of course, were instantly attracted to me. And in me, at that moment, a feeling was born. To be desired. Her paws touched me from flower to flower. Removing pollen. And birds chose me for their homes. I felt complete

(Student F, 2014).

Notes

1Catastrophism here is understood as a way of operating the discourse when working with the ecological importance of plants. In this approach, the focus is usually on crisis situations caused by human actions in relation to nature. Thus, when thinking about plants, these pedagogical initiatives focus on situations of deforestation, fires, climate change, etc. In this way, the subjects are questioned by the fear of catastrophe and invited to act based on fear. Garré e Henning (2015) and Henning (2019) make a great contribution in this regard by questioning media discourses on the environmental crisis related to work with environmental education.

2I highlight here some works in which other references are used to think about the teaching of botany. Marise Basso Amaral and Clara de Carvalho Machado (2014; 2015) depart from cultural studies to think about the teaching of botany. In both works, the authors present pedagogical proposals in which the focus is on the attempt to attribute to plants a role that overcomes the hegemony of scientific discourse. Thus, we seek to rescue personal stories and memories, as well as cultural narratives (films, drawings, poems, songs) in which plants are protagonists. According to the authors, these initiatives make possible the production of other meanings for plants, capable of giving them identities, particularities, singularities and individualization of their stories. In another work (Borja; Amaral, 2017), the proposal is to tell about the encounter of the authors with artistic works, whose themes involved plants. Here, they also start from the cultural studies of science, reflecting on how these artistic works can facilitate the construction of pedagogical practices for the teaching of botany, operating other relationships beyond the scientific dimension. The work by Moraes and Portugal (2021) proposes an interdisciplinary approach between art and botany. The authors use works by Brazilian modernist artists, especially participants in the Modern Art Week (Semana de Arte Moderna, in Brazil), as a starting point for thinking about teaching ethnobotany. To this end, they operate references of decoloniality and still use the anthropophagic manifesto as an articulating element to rethink the teaching of botany. Finally, Susana Dias’ research, articulating the philosophy of difference, literature and various contributions from indigenous thought, contribute immensely to opening up new possibilities for thinking about teaching botany using other references. I cite, as an example, the essay Perceiving-making Forest (Dias, 2020). There are certainly other proposals vibrating around, however, the intention is not to carry out an exhaustive survey, just to indicate the perception that, although they exist, they are still few.

3Rethinking the place of plants in teaching biology presupposes an ethical-political choice that can be considered as a gesture of inclusion. Thus, in the same way, considering that there is no neutrality in the text that is written and that the way in which it is written and inscribed also determines ethical and political positions, I assumed, throughout the text, the choice for a writing that also operates with this inclusion in the use of the articles, when necessary.

4In Brazil, animal studies have been more fruitful in the production of knowledge, mainly based on literary studies, anthropology and philosophy. In this sense, I highlight the work of Maria Esther Maciel (2011; 2021).

5Translation Note: In Brazil, in comparison with the American model, Educação Básica refers to: Educação Infantil (Kindergarten), to Anos Iniciais do Ensino Fundamental (Elementary School), to Anos Finais do Ensino Fundamental (Middle School) and Ensino Médio (High School). Therefore, we translate Ensino Fundamental as Elementary and Middle Schools and we do not translate Educação Básica, keeping the use of the term in Portuguese.

6The Sexual Strategies of Plants workshop was taught virtually by Fabiola Fonseca in March 2022. It is one of the initiatives of Liquen Educational Projects. Initiative led by Fabiola that promotes courses and workshops always articulating art, philosophy and biology. The project can be accessed at the following link: https://www.instagram.com/liquenprojeto/.

7Images can be viewed on the author’s website: https://www.florgarduno.com/.

8From the original: “[...] how can we decipher the mute language of plants and immerse ourselves in their stories?”.

9From the original: “[...] the specific modes in which the vegetal word is embedded in human cultural productions”.

10From the original: “[...] literary portrayal of plants that is indebted both to the ingenuity of the author who crafts the text and to the inscription of plants in that very process of creation”.

11From the original: “no se escriben ficciones para eludir, por inmadurez o irresponsabilidad, los rigores que exige el tratamiento de la “verdad”, sino justamente para poner en evidencia el carácter complejo de la situación, carácter complejo del que el tratamiento limitado a lo verificable implica una reducción abusiva y un empobrecimiento. Al dar un salto hacia lo inverificable, la ficción multiplica al infinito las posibilidades de tratamiento.”.

12In literary studies, the classic references of E.M. Foster (1974), denominate as spherical an unpredictable, complex character, of great psychological density. On the other hand, there are flat characters, those without major internal conflicts, who do not change with circumstances and have few nuances. There are numerous approaches to this discussion. Among them, we can mention Candido, Gomes, Prado and Rosenfeld (2009).

13The Evens are ethnic groups that distance themselves from life in post-Soviet Russia and make a return to their traditional way of life in the heart of the Siberian forests.

REFERENCES

ALBERT, Bruce. A Floresta Poliglota. Tradução de Vinícius Alves. Sub specie aeternitatis: experiências de antropologia especulativa, 2018. Disponível em: https://subspeciealteritatis.wordpress.com/2018/11/05/a-floresta-poliglota-bruce-albert/. Acesso em: 7 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

BELLINI, Larissa; SOUZA, Karolyne de; BARBOSA, Rayane; DIAS, Susana (Org.). Sopros da Mata – pensando com as plantas. Participação de Luã Apyká e Mariana Vilela. Campinas: ClimaCom, 2021. 1 vídeo (24 min.). Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MBhjNkMnp1Y. Acesso em: 31 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BORJA, Beatriz França; AMARAL, Marise Basso. “Lotes Vagos”: ensaios sobre arte e botânica. In: SEMINÁRIO BRASILEIRO DE ESTUDOS CULTURAIS E EDUCAÇÃO, 7.; SEMINÁRIO INTERNACIONAL DE ESTUDOS CULTURAIS E EDUCAÇÃO, 4., 2017, Canoas. Anais [...]. Canoas: ULBRA, 2017. Disponível em: http://www.2017.sbece.com.br/resources/anais/7/1495680873_ARQUIVO_LOTESVAGOS_ensaiossobrearteebotanica_trabalhocompletoSbece_FINAL.pdf. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2023. [ Links ]

CANDIDO, Antonio; GOMES, Paulo Emílio Salles; PRADO, Décio de Almeida; ROSENFELD, Anatol. A Personagem de Ficção. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2009. [ Links ]

CHAMOVITZ, Daniel. Daniel Chamovitz: Home. Be’er Sheva, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.danielchamovitz.com/. Acesso em: 28 mar.2022 [ Links ]

COCCIA, Emanuele. A Virada Vegetal. Tradução de Felipe Augusto Vicari de Carli. São Paulo: N-1edições, 2018a. [ Links ]

COCCIA, Emanuele. A Vida das Plantas: uma metafísica da mistura. Tradução de Fernando Scheibe. Florianópolis: Cultura e Barbárie, 2018b. [ Links ]

DIAS, Susana. Perceber-fazer Floresta: da aventura de entrar em comunicação com um mundo todo vivo. ClimaCom – Florestas, Campinas, ano 7, n. 17, jun. 2020. Disponível em: http://climacom.mudancasclimaticas.net.br/susana-dias-florestas/. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2023. [ Links ]

DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges. Cascas. Tradução de André Telles. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2017. [ Links ]

ESTADO Vegetal. Direção e roteiro: Manuela Infante. Intérprete: Marcela Salinas. New York: Jerome Robbins Theater, 2019. Disponível em: https://bacnyc.org/performances/performance/manuela-infante. Acesso em: 15 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

FAVERO, Fran. Jardins. Pigmento mineral sobre papel algodão, 45x30cm, série de 5 fotografias. São Paulo, 2017. Disponível em: http://franfavero.com/#jardins. Acesso em: 15 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

FIADEIRO, João; EUGENIO, Fernanda. Secalharidade como Ética e como Modo de Vida: o projeto AND_Lab e a investigação das práticas de encontro e de manuseamento coletivo do viver juntos. Urdimento – Revista de Estudos em Artes Cênicas, Florianópolis, v. 2, n. 19, p. 61-69, 2019. Disponível em: https://www.revistas.udesc.br/index.php/urdimento/article/view/3191. Acesso em: 4 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

FOSTER, Edward. Morgan. Aspectos do Romance. Tradução Sergio Alcides 2.ed. Porto Alegre: Globo, 1974 [ Links ]

GAGLIANO, Monica. Monica Gagliano: not all those who wander are lost. Lismore, 2016. (Blog). Disponível em: https://www.monicagagliano.com/. Acesso em: 30 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

GARDUÑO, Flor. Bestiarium. Zürich: U. Bär Verlag, 1993. [ Links ]

GARRÉ, Bárbara Hees; HENNING, Paula Corrêa. Visibilidades e Enunciabilidades do Dispositivo da Educação Ambiental: a revista Veja em Exame. Alexandria, Florianópolis, UFSC, v. 8, n. 2, p. 53-74, jun. 2015. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/alexandria/article/view/1982-5153.2015v8n2p53 Acesso em: 11 jan. 2023. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, Leandro Belinaso. A Nau Incendiária da Ficção. In: MARTINS, Miriam Celeste; FARIA, Alessandra Ancona; LOMBARDI, Lucia Maria Salgado dos Santos (Org.). Formação de Educadores: contaminações interdisciplinares com arte na pedagogia e na mediação cultural. São Paulo: Terracota Editora, 2019. [ Links ]

HARAWAY. Donna. Antropoceno, Capitaloceno, Plantationoceno, Chthuluceno: fazendo parentes. Tradução de Susana Dias, Mara Verônica e Ana Godoy. ClimaCom – Vulnerabilidade, Campinas, ano 3, n. 5, 2016. Disponível em: http://climacom.mudancasclimaticas.net.br/antropoceno-capitaloceno-plantationoceno-chthuluceno-fazendo-parentes/ Acesso em: 22 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

HENNING, Paula Corrêa. Estratégias Bio/Ecopolíticas na Educação Ambiental: a mídia e o aquecimento global. Educação Unisinos, v. 23, n. 2, p. 367-382, abr.-jun. 2019. Disponível em: https://revistas.unisinos.br/index.php/educacao/article/view/edu.2019.232.11/60746965 Acesso em: 11 jan. 2023. [ Links ]

INFANTE, Manuela; MARDER, Michel. Teatro Hoy 2020: Diálogo Sin Fronteras Manuela Infante y Michael Marder. Santiago de Chile: Fundación Teatro a Mil, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wxZTMkt45ck. Acesso em: 27 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

KANG, Han. A Vegetariana. Tradução de Jae Hyung Woo. São Paulo: Todavia, 2018. [ Links ]

KOPENAWA, Davi; ALBERT, Bruce. A Queda do Céu: palavras de um xamã Yanomami. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015. [ Links ]

KRENAK, Ailton. Ideias para adiar o Fim do Mundo. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2019. [ Links ]

LISBOA, Adriana. A Flor e o Seu Protesto. In: LISBOA, Adriana. O Vivo. Belo Horizonte: Relicário, 2021. P. 31. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Clara de Carvalho; AMARAL, Marise Basso. Um Pé de Cultura e de Milho, Angico, Mangaba e Baobá. Textura – Revista de Educação e Letras, Canoas, ULBRA, v. 16, n. 30, 2014. Disponível em: http://www.periodicos.ulbra.br/index.php/txra/article/view/1126/871. Acesso em: 17 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Clara de Carvalho; AMARAL, Marise Basso. Memórias Ilustradas: aproximações entre formação docente, imagens e personagens botânicos. Alexandria, Florianópolis, UFSC, v. 8, n. 2, p. 7-20, 2015. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/alexandria/article/view/1982-5153.2015v8n2p7. Acesso em: 17 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

MACIEL, Maria Esther. Poéticas do Animal. In: MACIEL, Maria Esther (Org.). Pensar/escrever o Animal: ensaios de zoopoética e biopolítica. Florianópolis: Editora UFSC, 2011. [ Links ]

MACIEL, Maria Esther. Pequena Enciclopédia de Seres Comuns. São Paulo: Todavia, 2021. [ Links ]

MANCUSO, Stefano. Revolução das Plantas: um novo modelo para o futuro. Tradução de Regina Silva. São Paulo: Ubu Editora, 2019. [ Links ]

MARDER, Michael. Sobre Plantas e Filosofia. Animalia Vegetalia Mineralia, ano 2, n. 6, 2015. Entrevista e tradução por Ilda Teresa Castro. Disponível em: https://animaliavegetaliamineralia.org/2015/11/29/year-ii-number-vi-autumn-ano-ii-numero-vi-outono-2015/. Acesso em: 2 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

MARQUES, Ana Martins. Jardim Francês. In: VIEIRA, Mauricio. Arvoressências: Jardins Imperfeitos, São Paulo, 2022. Disponível em: https://arvoressencias.format.com/6627205-2022#8. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

MARTIN, Nastassja. Escute as Feras. Tradução de Daniel Luhmann e Camila Vargas Boldrini. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2021. [ Links ]

MORAES, Vinícius dos Santos; PORTUGAL, Anderson dos Santos. Obras Modernistas e a Botânica: a construção de uma brasilidade e suas possibilidades de ensino decolonial. Vitruvian Cogitationes, Maringá, v. 2, n. 2, p. 74-87, 2021. Disponível em: https://periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/revisvitruscogitationes/article/view/63689/751375154240. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2023. [ Links ]

PELLEJERO, Eduardo. O Espaço da Ficção: linguagem, estética e política. Geografares, Vitória, UFES, v. 2, n. 22, p. 25-31, 2016. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufes.br/geografares/article/view/14826 Acesso em 21 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

SAER, Juan José. El Concepto de Ficción. Buenos Aires: Seix Barral, 2014. [ Links ]

SALATINO, Antonio; BUCKERIDGE, Marcos. “Mas de que te serve saber botânica?”. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo, v. 30, n. 87, p. 177-196, 2016. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/ea/a/z86xt6ksbQbZfnzvFNnYwZH/?lang=pt Acesso em: 15 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

SECALHARIDADE – MAYHAPNESS. Direção e roteiro: João Fiadeiro e Fernanda Eugénio. Produção: David dos Santos. Lisboa, 2010. 1 vídeo (54 min.). Disponível em: https://vimeo.com/47006267 Acesso em: 12 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

SILVA, Lenir Maristela; CAVALLET, Valdo José; ALQUINI, Yedo. O Professor, o Aluno e o Conteúdo no Ensino de Botânica. Educação, Santa Maria, v. 31, p. 67-80, jan.-jun. 2006. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufsm.br/reveducacao/article/view/1490. Acesso em: 17 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, Eduardo. Relicário de Pequenas Vidas. ClimaCom – Florestas, Campinas, ano 7, n. 17, maio 2020. Disponível em: http://climacom.mudancasclimaticas.net.br/eduardo-silveira-florestas/. Acesso em: 17 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, Eduardo; PIOVEZAN, Marcel (Org.). Desfazendo Invisíveis: um passeio pela antotipia e fitotipia. Florianópolis: Editora Caseira, 2021. Disponível em: https://editoracaseira.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Desfazendo-invisiveis_um-passeio-pela-antotipia-e-fitotipia-Silveira_Eduardo-Pionezan_Marcel-org-web_compressed.pdf. Acesso em: 17 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

TOWATA, Naomi; URSI, Suzana; SANTOS, Déborah Yara Alves Cursino dos. Análise da Percepção de Licenciandos Sobre o “Ensino de Botânica na Educação Básica”. Revista da SBenBio, v. 3, n. 1, p. 1603-1612, 2010. Disponível em: http://botanicaonline.com.br/geral/arquivos/Towataetal2010-20Bot%C3%A2nica.pdf. Acesso em: 17 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

TRAUBECK, Bartholomäus. Years. Bartholomäus Traubeck. Munich, 2011. (Blog). Disponível em: http://traubeck.com/works/years Acesso em: 14 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

URSI, Suzana et al. Ensino de Botânica: conhecimento e encantamento na educação científica. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo, v. 32, n. 94, p. 7-24, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/ea/a/fchzvBKgNvHRqZJbvK7CCHc/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 11 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

VIANNA, Hermano. Reconhecimento de Luiz Zerbini acompanha Virada Vegetal nas Artes e na Filosofia. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, maio 2021. Disponível em: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/colunas/hermano-vianna/2021/05/reconhecimento-de-luiz-zerbini-acompanha-virada-vegetal-nas-artes-e-na-filosofia.shtml. Acesso em: 25 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Patrícia. Phytographia: literature as plant writing. Environmental Philosophy, v. 12, n. 2, 2015. Disponível em: https://www.patriciavieira.net/app/download/6086917162/Phytographia.pdf?t=1635518962. Acesso em: 12 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

WANDERSEE, James; SCHUSSLER, Elisabeth. Toward a Theory of Plant Blindness. Plant Science Bulletin, Emporia, v. 47, n. 1 p. 2-9, jun.-ago. 2001. Disponível em: https://cms.botany.org/userdata/IssueArchive/issues/originalfile/PSB_2001_47_1.pdf. Acesso em: 7 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

WOOD, James. Como funciona a Ficção. Tradução de Denise Bottmann. São Paulo: SESI-SP Editora, 2017. [ Links ]

ZAMBRA, Alejandro. A Vida Privada das Árvores. Tradução de Josely Vianna Baptista. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2013. [ Links ]

Received: April 29, 2022; Accepted: January 23, 2023

texto em

texto em