1. Introduction

Cyberspace is based on three fundamental principles: production, distribution, and sharing (LEMOS; LEVY, 2010), which are also principles of web 2.0. The web 2.0 “is the network as platform, spanning all connected devices; Web 2.0 applications are those that make the most of the intrinsic advantages of that platform” (O’REILLY, 2005, online). According to O’Reilly (2005), these advantages involve “delivering software as a continually-updated service that gets better the more people use it, consuming and remixing data from multiple sources, including individual users, while providing their own data and services in a form that allows remixing by others, creating network effects through an architecture of participation” (O’Reilly (2005, online).The architecture of participation describes the nature of systems that are designed for user contribution (O’Reilly (2005).

Through this perspective, web 2.0 goes “beyond the page metaphor of web 1.0 to deliver rich user experiences” (O’REILLY, 2005, online). We can also understand this as an evolution of the usage perspective, which shifts from a passive consumption of content to an active participation, involving possibilities of creation, distribution, and sharing content.

The user active participation is possible through different web 2.0 applications such as blogs (e.g., Blogger, Wordpress), micro-blogs (e.g., Twitter), social networks (e.g., Facebook), social bookmarking (e.g., Diigo), wikis (e.g., Wikipedia), file sharing (e.g., Dropbox), and many more.

Studies point out that the use of web 2.0 applications in educational settings can enhance pedagogical innovations because they allow new forms of collective creation, sharing of content, and communication between students and teachers/professors. Besides, the use of different web applications in education allows the creation of Personal Learning Environments (PLE) (CONOLE, 2013; CASTAÑEDA; ADELL, 2013).

A review of the PLE concept conducted by Fiedler and Väljataga (2013) points out two perspectives involving the PLE research. One group focuses on the study of technical issues, addressing the research on networked tools and services that students can use. A second group focuses on the PLE concept from an educational approach. The findings of their research show us that the PLE concept “is best treated as an intermediated concept that allows systematic further development of learning activity and its digital instrumentation” (FIEDLER; VÄLJATAGA, 2013, p.8).

In the present study, we understand that it is possible to take advantage of both approaches aiming to organize a proposal for assisting teachers to foster educational practices with technologies in the context of the classroom from the perspective of the PLE. As the first research group, we understand the importance of providing a set of networked tools and services as a first step to the teachers in order to promote the use of web 2.0 in education. It is important that teachers have the opportunity to find and explore different web tools. However, the emphasis of this study is not on the tool, but in the relationship between the potential of the web 2.0 application and the learning project. Through this perspective, as the second research group, we understand that “PLE certainly goes beyond mere digital instrumentation of activity” (FIEDLER; VÄLJATAGA, 2013, p.7).

In this study, we assume that the PLE “can be seen as a pedagogical approach with many implications for the learning processes, underpinned by a ‘hard’ technological base” (ATTWELL; CASTAÑEDA; BUCHEM, 2013, p. iv). Furthermore, according to the researchers, “such a techno-pedagogical concept can benefit from the affordances of technologies, as well as from the emergent social dynamics of new pedagogic scenarios” (ATTWELL et al, 2013, p. iv).

Thus, what exactly do we understand a PLE includes? According to Castañeda and Adell (2013) a PLE is organized with tools, mechanisms, and activities that each student uses to read, produce/reflect about, and share in communities. These actions refer to the principles of producing, distributing, and sharing inherent to web 2.0.

From a reading perspective, the tools are characterized by sites, blogs, newsletters, video channels and others, and the information has different forms, such as text, audio and video. The activities involve reading, reviewing texts among others, exercising the use of search engines, curiosity and initiative. From a producing perspective, the tools are the spaces where the student can document his process of reflection based on collected information; these tools are spaces to write, to reflect and to publish. Blogs, conceptual maps, and online presentations are examples. Finally, tools for sharing and reflecting on communities are characterized as spaces where the student can talk and exchange ideas with other subjects with the purpose of forming social networks (CASTAÑEDA; ADELL, 2013).

Therefore, in a PLE the students integrate both the experiences in formal education and the new experiences with the use of web applications and services. This way the PLE potentializes the recording of the learning process and also the interaction and communication processes with different subjects and groups, as well as the access to different learning digital resources. Thus, the PLE is not a technology but an approach, a way through which we can use the digital technology to teach and to learn (CASTAÑEDA; ADELL, 2013).

Through this perspective, a PLE is composed by personal issues but also includes the social environment involving the interactions with other subjects. These interactions compose the Personal Learning Network (PLN). The PLN includes the subject-subject interactions mediated by the PLE, and characterizes the social part of the learning environment. (CASTAÑEDA; ADELL, 2013).

Williams, Karousou and Mackness (2011) distinguish between two modes of learning called prescriptive learning systems and emergent learning networks. They are associated with two domains of application for learning: predictable domains and complex-adaptive domains. In predictable domains, the learning is based on a prescriptive mode. Prescriptive learning is based on a proposal usually used in formal education, where the content is duplicated and distributed, based in a one-to-many perspective in a fixed and predictable context.

On the other hand, a complex-adaptive domain is based in emergent learning networks and characterizes a learning process, which is typically collaborative. This way, the emergent learning is characterized by unpredictability and to emerge from the interaction between students and their context. Examples include the use of social software and PLE.

This way, to boost the use of PLE in the context of formal education consists of validating the prescriptive learning as well as the emergent learning (WILLIAMS et al, 2011).

According to Williams et al (2011), web 2.0 provides condition for emergent learning, but does not necessarily lead to this. The authors point out that learning has always included prescriptive and emergent learning, but they highlight the importance of a “a shift from a monolithic learning environment in which everything must be controlled and predictable to a more pluralistic learning ecology in which both prescript and emergent application domains and modes of learning have their place” (WILLIAMS et al, 2011, p. 55).

Through this perspective, many web 2.0 tools are interesting for promoting an emergent process of learning. However, there are many applications and services in web 2.0. How to choose the most appropriate one of these applications to design educational practices to foster the PLE of the students?

This article aims to help teachers to foster educational practices with technologies in the context of the classroom from the perspective of the PLE.

It is important to state that this study focuses on the role of the teachers in promoting the use of web 2.0 in an educational context. However, if the PLE is related to the experiences of a particular subject, how can the teacher indicate tools and applications? In this study, we understand that the teacher can enhance the student’s learning process by promoting the use of digital learning tools.

Recent researches show that Brazilian students use the computer and the internet frequently, but the main activity related to learning is research support. On the other hand, teachers are using the internet for personal and professional activities, but they need to improve the use in their teaching (ICT Education 2012, 2013; ICT Kids online 2012, 2013). Thus, we understand that in one first moment the teachers can start using web 2.0 in education through a PLE perspective in order to show students how they can use web applications in their learning activities. After, in a second moment, students can start to select and use web tools and services according to their learning necessities.

The study presented here is part of a major research called “Teaching and learning on the web: the architecture of participation of web 2.0 in the context of face-to-face education” (BASSANI, 2012), which aims to investigate the potential of the web’s architecture of participation in the teaching and learning process in the final years of elementary school with the purpose of developing a proposal for the use of social software in education.

This article is organized as follows: in section 2 we present the research context, which describes the educational setting; presents a reflection on frameworks for building web 2.0 based PLE; and a study about web 2.0 tools. In section 3, we present the research path, which involves the presentation of our framework and its validation procedures in a school context. We finish the paper by presenting the findings and making recommendations for future research.

2. The research context

This section presents the research context, involving a description of the educational setting based on data about the use of information and communication technologies in Brazilian schools. We also present a study about frameworks for building web 2.0 based PLE and web 2.0 tools, which can be used in educational settings.

2.1. Educational context

In our context, in Brazil, the research called Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Brazilian Schools (ICT Education 2012, 2013), conducted by Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (CGI), shows that 92% of the teachers use the internet to prepare classes and download content (e-book, audio, video, etc.). However, the most frequent activities with the students are those that do not involve the use of computers and internet, such as practical exercises related to the content of the class, lectures, and reading comprehension. On the other hand, 94% of the teachers don’t have difficulty in using a search engine to look for information, 58% don’t have difficulty in taking part in online discussion forums, and 74% of them don’t have difficulty in taking part in social networking websites. So, we can understand that the teachers are using the internet for personal and professional activities, but they need to improve the use in their teaching.

Besides, the results of ICT Education 2012 (2013) show that the students use the computer and internet frequently, but the main activity related to learning is research support. This shows that the potential of communication and interaction of web 2.0 could be more explored in Brazilian educational context.

Another interesting research is the ICT Kids Online 2012 (2013), a survey called Internet Use by Children in Brazil, also conducted by Brazilian Internet Steering Committee. The survey, which involved children and teenagers between 9 and 16 years old, shows that 47% of them access internet every day. Related to their activities online (considering 1 month of use), 82% used the internet for school work, 68% visited a social networking profile/page, 66% watched video clips (e.g., on YouTube), 54% played games with other people on the internet, 54% used instant messaging with friends or contacts, 49% sent/received e-mail, 44% downloaded music or film, 42% read or watched the news on the internet, 40% posted photos, videos, or music, 17% spent time in a virtual world, 10% wrote a blog or online diary, and only 6% used a file-sharing site. The ICT Kids Online 2012 (2013) research shows that Brazilian students are using the internet for school research, but they also use it to communicate with friends. It’s interesting to see that they are mainly content consumer but there is a movement to content producing.

We consider, then, that this context fosters the use of internet tools in an educational proposal. Thus, for us, it is necessary to show students how they can use web applications in their learning activities.

It’s necessary to mention that we understand that the school is an important space for digital inclusion. This means that in the context of this work we recognize the importance of the teachers in showing different possibilities to the students on how they can improve their learning possibilities using the internet. This way, the teachers have an important role in promoting activities that explore the potential of cyberspace as a learning space that foster production, distribution, and sharing of content and knowledge. This is our research focus.

Bates (2011) says that web 2.0 tools are relatively new in education and the educators still need to find new proposals to teach and to learn using the potential of interaction and communication of these tools.

In this study we understand that it is possible to enlarge the student’s connectivity through web 2.0 tools once they can create their PLE, share content, and discuss with their group of colleagues. These elements are stated by several authors studying the characteristics of the users of the web. Pisani and Piotet (2010) indicate that current web users are no longer passive browsers, which only consume content provided by specialists. According to them, current users “propose services, share information, comment, engage, participate” (p.16). These new users, who are not satisfied with just browsing, but producing web content, are called web actors. Thus, we need to investigate how to use the potential of technology in the teaching and learning process of these subjects.

2.2. Frameworks for building web 2.0 based PLE

A number of studies have been conducted involving the development of conceptual frameworks for building web 2.0-based PLE (TORRES-KOMPEN; MOBBS, 2008; RAHIMI; VAN DEN BERG; VEEN, 2012, 2013).

The framework proposed by Torres-Kompen and Mobbs (2008) focuses in the use of a web 2.0 application as a hub. They understand it is necessary that the student chooses an application as a central component for the PLE. This, according to them, facilitates the access to the student’s collection of web 2.0 tools, facilitates the management of different logins and passwords, and allows the sharing of data between different tools that compose the PLE. In their study, they present four different approaches for building a PLE, and each approach is based in a web 2.0 tool as a central hub: wiki-based PLE (Google sites), social network-based PLE (Facebook), social aggregator-based PLE (Netvibes), and browser-based PLE (Flock).

Rahimi, Van den Berg, and Veen (2012) presented a framework to design and implement a PLE in a secondary school. The framework is based on constructivism as its theoretical foundation, and proposes a model to incorporate PLE building into teaching and learning processes. The model to integrate PLE building into teaching and learning processes based in a constructivist approach involves 8 elements: (a) selecting learning topic; (b) defining learning objectives; (c) defining pedagogical and/or technical tasks, guidelines and assignments based on the learning topic and objectives; (d) selecting organizational form and web tools for assigning to the tasks; (e) accomplishing tasks, developing PLE; (f) supporting learner pedagogically and/or technically; (g) assessment and evaluation; (h) reflection on process, learning experiences, learning outcomes, and learning values of tools (RAHIMI et al, 2012). Their research was conducted with a group of thirty 12-13-year-old students enrolled in a first-year class of a secondary school. The web 2.0 tools “were selected based on prior experience of the teacher with tools, appropriateness to the defined learning objectives, and technological affordances of the school (p. 7)”. During the research, teachers and students faced some technical problems to create an account in some web tools, and it caused some dissatisfaction. So, the researchers suggest that it is important not to “over estimate digital capabilities of students. They need preparation to be able to tailor web tools to their learning needs and activities” (p. 14).

In another paper Rahimi, Van den Berg, and Veen (2013) present a study that focuses in the student’s control as the core part of a PLE. They understand that web 2.0 has the potential to support students as knowledge producers, as socializers, and as decision makers. They proposed a roadmap to be used by educators to guide the design of technology-enhanced learning activities which can assist students in the development of their web 2.0-based PLE and to achieve control over their learning. Their framework is based on three aspects: the student’s control model (producer, socializer, and decision maker), the learning potential of web2.0 tools, and Bloom’s digital taxonomy map (thinking process includes remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating and creating sub-processes). According to them, “the roadmap can augment the decision-making role of students by allowing them to find, use, assess, and introduce relevant web tools and services” (RAHIMI et al, 2013, p. 11).

Thus, the framework proposed by Torres-Kompen and Mobbs (2008) focuses in a main tool as a hub to start the PLE, and the roadmap proposed by Rahimi et al (2012, 2013) is interesting because it focuses on learning activities which enhance the student’s control.

Based on Torres-Kompen and Mobbs (2008) proposal it is necessary that the student chooses an application as a central component for the PLE, because their framework uses a web 2.0 application as a hub. In this case, the teacher and the students need to learn an application and use it in deep. Rahimi et al (2012) proposed a framework, which integrated the development of the PLE into teaching and learning processes based in a constructivist approach. Although this framework proposes the use of a web application based on a pedagogical model, it does not indicate a way which the teacher can select the web 2.0 tools.

Considering the Brazilian educational context revealed in national researches, it is important to guide the teacher and show to him how an application can be selected according to the learning goals. Besides, it is also important to the students the development of competencies for the use of web 2.0 tools in their learning process. Based on this, we understand that the effective use of web applications in educational practices can enhance the use of web 2.0 tools by the students. Thus, the use of technology in educational practices, by the teachers, always involves the knowledge of this technology as well as a level of confidence with the resources to be used. Therefore, we understand that it is important to assist teachers in the selection of web applications and also in the identification of how these tools can support learning processes and to foster the PLE of the students. This is the aim of our framework proposal.

2.3. Web 2.0 tools

We assume, like Rahimi et al (2012), that the first experiences in the use of web 2.0 tools in education could involve tools in which the teacher has prior experience. However, sometimes the proposal for learning outcomes will explore mechanisms and activities that will ask for unknown tools. Where can the teachers find information about them?

The Centre for Learning and Performance Technologies,1 an independent website about learning trends, technologies, and tools, publishes studies about the use of technologies for learning. Every year it presents the results of a survey called Top 100 Tools for Learning.

According to Hart (2013, online) a learning tool “is defined as any software or online tool or service that you use either for your own personal or professional learning, for teaching or training, or for creating e-learning”.

The results of the 7th Annual Learning Tools Survey were presented in 2013. The data were compiled from the votes of 500+ learning professionals in around 48 countries (HART, 2013). The tools are organized into 13 (thirteen) categories,2 according the table 1.

Table 1 Categories of web 2.0 tools (HART, 2013)

| Category | Types |

|---|---|

| Instructional Tools | Course Authoring Tools; Testing, Quizzing and Other Interactive Tools; Course/Learning Management Systems & Learning Platforms |

| Social and Collaboration Spaces | Public social networks & micro-sharing platforms; Group, project, team, community and enterprise platforms; Tools for the Social Classroom (for ages 5-18) |

| Twitter apps | Twitter Apps |

| Web meeting, conferencing and virtual world tools | Web meeting, webinar & virtual classroom tools; Screen sharing tools; Webcasting tools; Virtual world tools |

| Document, Presentation and Spreadsheet Tools | Document creation & hosting tools; Presentation creation & hosting tools; PDF tools; 3D (page turning) tools; Spreadsheet tools |

| Blogging, Web and Wiki Tools | Blogging tools; Wiki tools; Web page/site tools; Form, polling and survey tools; RSS feed tools |

| Image, Audio & Video Tools | Image ; Image and photo editing; Screen capture; Image galleries & photo sharing sites; Audio/podcast ; Audio/podcast editing; Audio/podcast streaming; Audio/podcast hosting; Video ; Video creation & editing; Screencasting ; Video streaming; Video hosting |

| Communication Tools | Email tools; Newsletter tools ; SMS/text tools; Instant messaging tools; Live chat tools ; Voice and video groups ; Discussion forum tools; Audience response/Backchannel tools |

| Other Collaboration & Sharing Tools | Social bookmarking; Collaborative research; Content curation tools and services; Shareable notes/notebooks; Shareable/group organizers; Collaborative corkboards ; Collaborative whiteboards; Collaborative mindmapping; Social calendaring tools; Shareable mapping; Sharing files across computers |

| Personal Productivity Tools | Search engines and discovery tools; Research/Personal study tools; Personal organizers ; Personal mindmapping ; Content curation tools and services; Computing utilities ; Personal productivity tools; Personal notebook tools |

| Browsers, Players & Readers | Web browsers and Add-nos; RSS & News Readers; Desktop apps & players; Start pages |

| Public Learning Sites | Find out about anything and everything; Learn a language online; Learn about business |

The table 2 presents the first 25 tools most used for learning, according the research Top 100 Tools for Learning 2013.3

Table 2 Top 25 Tools for Learning

| Tool | Description | Category | Link | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social network and micro-blogging site | Social and Collaboration Spaces | http://twitter.com | |

| 2 | Google Drive/Docs | Office suite & file storage service | Document, Presentation and Spreadsheet Tools | http://drive.google.com/ |

| 3 | YouTube | Video-sharing site | Public Learning Sites | http://youtube.com |

| 4 | Google Search | Web search engine | Personal Productivity Tools | http://www.google.com.br |

| 5 | Power Point | Presentation software | Document, Presentation and Spreadsheet Tools | --- |

| 6 | Evernote | Productivity tool | Personal Productivity Tools | http://evernote.com |

| 7 | Dropbox | File storage & synchronization | Other Collaboration & Sharing Tools | http://dropbox.com |

| 8 | Wordpress | Blogging/website tool | Blogging, Web and Wiki Tools | http://wordpress.com |

| 9 | Social network | Social and Collaboration Spaces | http://www.facebook.com.br | |

| 10 | Google+ & Hangouts | Social networking & video meetings | Web meeting, conferencing and virtual world tools | http://plus.google.com |

| 11 | Moodle | Course management system | Instructional Tools | --- |

| 12 | Professional social network | Social and Collaboration Spaces | http://www.linkedin.com | |

| 13 | Skype | Text and voice chat tool | Communication Tools | http://skype.com |

| 14 | Wikipedia | Collaborative encyclopedia | Other Collaboration & Sharing Tools | http://wikipedia.com |

| 15 | Prezi | Presentation creation and hosting service | Document, Presentation and Spreadsheet Tools | http://www.prezi.com |

| 16 | Slideshare | Presentation hosting service | Document, Presentation and Spreadsheet Tools | http://slideshare.net |

| 17 | Word | Word processing software | Document, Presentation and Spreadsheet Tools | --- |

| 18 | Blogger/Blogspot | Blogging tool | Blogging, Web and Wiki Tools | http://www.blogger.com |

| 19 | Feedly | RSS reader/ aggregator | Browsers, Players & Readers | http:// feedly.com |

| 20 | Yammer | Enterprise social network | Social and Collaboration Spaces | http://yammer.com |

| 21 | Diigo | Social bookmarking/ annotation tool | Other Collaboration & Sharing Tools | http://diigo.com |

| 22 | Pinning tool | Other Collaboration & Sharing Tools | http://pinterest.com/ | |

| 23 | Scoopit | Curation tool | Other Collaboration & Sharing Tools | http://www.scoop.it/ |

| 24 | Articulate | E-learning authoring software | Instructional Tools | http://www.articulate.com |

| 25 | TED talks/Ed | Inspirational tools/ lessons | Public Learning Sites | http://ted.com |

The results of the Top 100 Tools for Learning research (HART, 2013) show that Twitter is in first place since 2009. GoogleDocs/Drive, which was in third place in the last three years, assumes the second position, and YouTube, which was in second place in the last three years, assumes the third place. According to the research, since 2010 Twitter, GoogleDocs/Drive, and YouTube share the first three positions in the ranking of the most used tools for learning (HART, 2013). Therefore, we can observe a tendency for the use of tools based on emergent learning networks, as stated by Williams et al (2011).

How to choose the most appropriate one of these web tools to design educational practices to foster the PLE of the students? The next section presents our research path involving the proposal of a framework to assist teachers in the selection of web tools for using in the school context to foster educational practices based on PLE and its validation procedure in a school context.

3. The research path

The research path was divided into two phases:

Phase 1: Involved an exploratory study about the use of information and communication technologies in Brazilian schools; existing frameworks for building web 2.0 based PLE; and web 2.0 tools which can be used in educational contexts. As a result, we proposed a framework to assist teachers in the selection of web tools for using in the school context to foster educational practices based on PLE.

Phase 2: Involved the validation procedures of the proposed framework, presenting the process of planning activities with technologies in the educational context. Our research,4 which had a qualitative approach, was conducted in four classes of the final years of elementary education, with 11-13-year-old students, in a private school in the south of Brazil. Data were collected from informal interviews and discussions with teachers and observation in loco during the activities in the classroom. The data were analyzed based on the proposed framework.

Each phase is explained below.

3.1. A framework for selecting web 2.0 tools in a PLE perspective

In his study, we consider that a PLE is organized with tools, mechanisms, and activities for reading, producing, and sharing (CASTAÑEDA; ADELL, 2013). However, researches show that the main activity using digital technologies proposed by teachers in school settings is research (ICT Education 2012, 2013), and this emphasizes only the reading aspect of a PLE. However, there are many interesting online web 2.0 tools that can be explored to promote mechanisms and activities for producing and sharing.

Through this perspective, we propose a framework that helps teachers in the selection of web tools to be used in school settings, based on a PLE perspective.

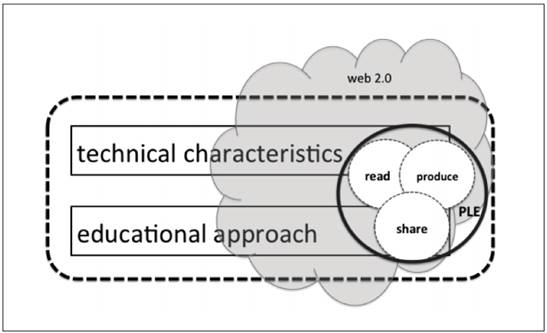

The framework is organized in two layers. The first layer of the framework is based on the educational approach, and the second layer focuses on the technical characteristics of the web tool. These two layers are interconnected on a PLE perspective (Figure 1).

3.1.1 First layer: educational approach

The PLE is not a technology but an approach that guides us on the use of technology to teach and above all to learn (ADELL; CASTAÑEDA, 2013). Adell and Castañeda (2013) assume that a PLE is an emergent pedagogy which is defined as a set of pedagogical approaches and ideas still not very systematized. This pedagogy emerges from the use of information and communication technologies in education and intends to use all communicational, informational, collaborative, interactive, creative, and innovative potential in the context of a new culture of learning.

According to Castañeda and Adell, (2013) a PLE is organized with tools, mechanisms, and activities that each student uses to read, to produce, and to share.

The first components of a PLE are the information sources and involve tools like web sites, blogs, video channels, newsletters, etc. The use of these tools, characterized as spaces and mechanisms for reading, enhances experiences associated with searching and organizing data. The second component of a PLE refers to tools, mechanisms, and activities for producing. There are many tools for producing texts, videos, presentations, conceptual maps, blogs and many more. The production involves reflection in order to organize ideas. Finally, the third component of a PLE involves sharing and this fosters the formation of personal learning networks (PLN) using social software (CASTAÑEDA; ADELL, 2013).

It is important to emphasize that there are no tools, activities or mechanisms that can be considered exclusive of a part of the PLE (CASTAÑEDA; ADELL, 2013). The different components of PLE are articulated. For example: a blog can be a tool for reading, a space to reflect and to produce. Another important characteristic of the PLE is that it changes progressively, being continuously reformulated based on the learning objectives of a subject and also on the social activities as part of the learning experiences (TORRES-KOMPEN; COSTA, 2013). Thus, a PLE is always “under construction”.

Through this perspective, we understand that the PLE concept proposed by Castañeda and Adell (2013) offers an interesting basis to our study.

In our framework, the educational approach guides the selection of the web tools. This way, it is important to identify the learning goals which involve making explicit the learning activities and their mechanisms (reading, reflecting, producing, discussing, among others).

3.1.2 Second layer: technical characteristics

We understand that the technical characteristics of a web tool are important because different web applications produce different kinds of interaction. Besides, each tool enables different activities for reading, producing, and sharing, this way fostering distinct mechanisms (e.g., searching, synthesis, discussions). Thus, it is important to know the potential of the tools for planning educational activities involving their use in education (BASSANI, 2012; CASQUERO, 2013, BASSANI; BARBOSA, 2015).

Our framework proposes six criteria for selecting a web 2.0 application based on its technical characteristics, as follows:

web tool: the main point of this paper is the use of web 2.0 in educational settings. Thus, the first selection criterion, in the context of our study, is that the tool should be a web tool;

gratuity: we understand that a free tool can be used in the classroom, but also in the student’s private life to improve his personal learning network;

age: it is important to consider the age criterion. Some tools are open to everyone and others have age restrictions. For example, Facebook and Google ask for 13-year-old;

hybrid access mode: the use of an application through different access devices (computer, mobile devices) is another important element to analyze. Different devices promote different experiences. Furthermore, there are web tools that don’t have applications available to mobile devices, and some don’t have all functions available to mobile. In this study, we understand that mobile devices, especially smartphones and tablets, allow the remote access to communication and information wherever the subject is. This context is building a new mixed space between the virtual (the cyberspace), and the physical space. These spaces are known as hybrid spaces because they “combine the physical and the digital in a social environment created by the mobility of users connected via mobile communication devices” (SANTAELLA, 2010). Therefore, a hybrid space must necessarily combine the physical and digital environments in social practices that build connections from various devices such as mobile phones, laptops and tablets. So, the Hybrid Access Mode criterion involves the possibility to access a web application in both tablets and desktops/laptops. This is an important criterion for our research because we use both computers and tablets in practices with teachers;

type of communication: some tools can be used in both synchronous and asynchronous mode. In some contexts, where the internet connection is a problem, synchronous tools should be avoided;

visibility: the use of web 2.0 tools in education can be analyzed through the visibility perspective. Our framework uses three possible online spaces: me, we, and see (HEPPELL, 2012). According to Heppell (2012), the first space, called me, is the private one, and it is characterized by tools where the subject can organize his own contents, annotations, and other personal and private information and materials. The second space is called we, and it involves tools that allow the subject to work in groups sharing the space with colleagues and friends. The third space is the public one where all web users can see the materials published by an author (HEPPELL, 2012). Through this perspective, the students develop their tasks in different web 2.0 applications, and each of them has a different kind of visibility (HEPPELL, 2012). Therefore, students can use some tools for personal use (me), for sharing with a group and practicing collaborative work (we), or even sharing on Internet (see). This way, the material produced by the student can only be used for private purposes, be shared with a group (teachers, colleague), or published on the public space of Internet.

Figure 2 shows the six criteria proposed for the second layer of the framework. These criteria are not explicit in the framework, but they guide the analysis and the selection of web 2.0 tools by the teachers. It is important to remember that the choice of some tools to be used in an educational context must be articulated with the learning goal. However, it’s relevant to consider that in a PLE perspective the selection of the tool is also a choice of the student.

3.2. Validation procedures of the framework

The validation procedures of the proposed framework were conducted in four classes of the final years of elementary education in a private school in the south of Brazil, involving 11-13-year-old students.

The activities comprised:

interviews and discussions with teachers in order to identify the learning goals (first layer: educational approach);

selection of web tools (second layer: technical characteristics)

observation in loco during the activities in the classroom.

3.2.1 Results

The first activity involved interviews and discussions with teachers in order to identify the learning goals, which are the basis of the proposed framework. Table 3 summarizes these four case studies.

Table 3 Case studies

| Case | Subject | Grade | Learning Goal | Visibility of the activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arts | 8o (±13 y) | Share the students photo production on the web, allowing them to see each other’s production | Public on the web |

| 2 | Portuguese | 7o (± 12y) | Produce a collective text | Work group |

| 3 | Spanish | 6o (± 11y) | Produce and share a video to exercise Spanish conversation | Pair work |

| 4 | Spanish | 7o (± 12y) | Produce and Share a mix of text, audio and photo to exercise grammar studies | Work group |

The identification of the educational approach (Table 3) was the basis for the selection of web 2.0 tools, the second layer of the proposed framework.

There are many web tools, but in this study we proposed to use the research Top 100 Tools for Learning as guide for this selection (Table 2). However, this is not the unique list. Teachers can select and analyze different web applications using this proposal.

Our framework proposes six criteria for selecting a web 2.0 application based on its technical characteristics, as follows: web tool, gratuity, age, hybrid access mode, type of communication, and visibility.

First, we analyze the tools listed on Table 2 based on three criteria: web tool, gratuity, and type of communication (focusing in asynchronous communication). This way, some tools, which did not fit into the established criteria, were withdrawn from the list (e.g. Skype, PowerPoint, etc.).

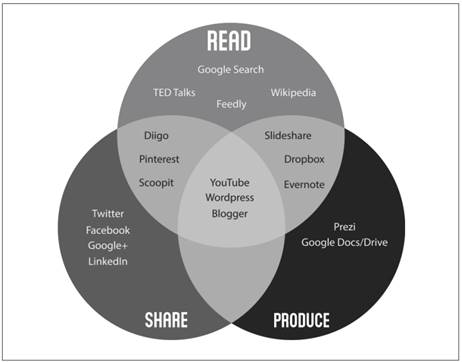

We also classify each tool based on its main function: tools for reading, for producing, and for sharing. However, the same tool can be used in different ways, according to the pedagogical approach. Therefore, the organization of table 4 was based on the characteristics of the tool and not in the various uses that we can make of it.

Table 4 Selected tools from the Top 25 Tools for Learning

| Category | Web tool | PLE |

|---|---|---|

| Social and Collaboration Spaces | Twitter; Facebook; Linkedin | Share |

| Web meeting, conferencing and virtual world tools | Google + | Share |

| Document, Presentation and Spreadsheet Tools | Google Docs/Drive; Prezi; Slideshare | Produce; Produce; Produce/read |

| Public Learning Sites | YouTube; TED Talks | Read/produce/share; Read |

| Personal Productivity Tools | Google Search; Evernote | Read; Read/produce |

| Blogging, Web and Wiki Tools | Wordpress; Blogger/Blogspot | Read/produce/share |

| Other Collaboration & Sharing Tools | Dropbox; Wikipedia; Diigo; Pinterest; Scoopit | Read/Produce; Read; Read/share; Read/share; Read/share |

| Browsers, Players & Readers | Feedly | Read |

Figure 3 presents the Table 4 in a visual form, highlighting the tools which can be used in a PLE.

There are three criteria that don’t appear in this first analysis: age, hybrid access mode and visibility. We understand these criteria are related to the group of students and the learning goals.

In the case of our study, we want to test mobile experiences with the use of tablets. The age and the visibility of the student’s production is another important issue, because the students are between 11 and 13 years old.

Articulating the educational approach (Table 3) and the analysis of the technical characteristics of web tools (Figure 3) we proposed one tool which is appropriate for an educational practice. Table 5 summarizes the cases and the selected web tool.

Table 5 Case studies with the selected tool

| Case | Subject | Grade | Learning Goal (mechanism and activity) | Visibility of the activity | Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arts | 8o (±13 y) | Share the students photo production on the web, allowing them to see each other’s production | Public on the web (see) | |

| 2 | Portuguese | 7o (± 12 y) | Produce a collective text | Work group(we) | GoogleDocs |

| 3 | Spanish | 6o (± 11 y) | Produce and share a video to exercise Spanish conversation | Pair work(we) | Dropbox |

| 4 | Spanish | 7o (± 12 y) | Produce and Share a mix of text, audio and photo to exercise grammar studies | Work Group(we) | Evernote |

After this definition, the research team observed the class to verify in loco the progress of the activity.

3.2.2 Discussion

The case 1 occurred in 8th grade Art classes. All students were 13 years old. First, we discussed with the teacher the aim of the proposal. The aim was to share the student’s work on the web - an artistic photo created by students - in order to enhance their confidence on their work. The teacher did not propose a specific tool.

So, considering the learning goal (to share the students’ photo productions on the web, allowing them to see each other’s production), and based on Figure 3, we proposed the use of Pinterest.

This tool is available through computers, tablets, and smartphones. So, it is suitable with the hybrid access mode criterion. The work published on Pinterest is public on the web (see visibility). In this case, Pinterest attended the three criteria: age, visibility, and hybrid access mode.

The students published their work on Pinterest and looked for the work of their colleagues. It was interesting to observe that only one student had used Pinterest before the practice. In this case, the students had the opportunity to known a new tool.

Another interesting fact we observe is that students don’t use email frequently. They had to make login in Pinterest using Facebook. Thus, the limitation of this practice was the fact that the students had difficulty to find the colleague’s work since it was necessary to know each other’s e-mail or username. We tried to use a private hashtag but even so we had problems to find the productions.

Case 2 involved a 7th grade Portuguese class. The aim was to produce a collective text in groups. So, considering Figure 3, the first idea was to use GoogleDocs. However, GoogleDocs is not well supported in tablets and, in this case, doesn’t fit on the hybrid access mode criterion. On the other hand, GoogleDocs allows the three kinds of visibility: me, we, and see. Another important issue is related to the age criterion, since a Google account is not allowed for children under 13-year-old.

As said before, we understand the teacher has an important role in promoting activities that explore the potential of cyberspace as a learning space introducing new tools to students which allow them to improve their learning activities. In this case, we decided to make an experience with GoogleDocs even though it doesn’t fit all three criteria. We created different accounts for each group and the students had the opportunity to explore the potential of this tool for collective writing. It’s possible to create a document, which can be accessed only by those who have the link without the necessity of using an account. Thus, it enabled the students to participate of a collective writing in GoogleDocs without a Google account.

We mixed the use of tablets and laptops. This practice was very interesting because the students had the opportunity to see that the tools behave in different ways according to the device used. The students had to finish their work on laptops.

Case 3 and Case 4 relate a practice developed in Spanish classes. Case 3 involved a 6th grade class and case 4 a 7th grade one.

In case 3, the aim of the task was to exercise Spanish conversation. The students had to produce a video in pairs. Afterwards, students had to see each other’s production. So, considering the aim (produce and share), we proposed Dropbox. Dropbox is not a tool to produce videos, but we can share our productions in it. In this case, the video was produced using the camera application available on tablets. Dropbox allows we visibility, as intended by the teacher for this learning task, and can be used with tablets (hybrid access mode). However, we had problems with the age of the students. Most students were 11 years old and some of them did not have e-mail. In this case, we decided to create an account for the class and everybody published the videos in the same folder. So, even though it was possible to create we visibility in Dropbox, we simulated it creating only one account. In this case, all students had access to the same account and we discussed about the rules of sharing a space (erase the colleague’s videos or change the password).

The last case presented here (case 4) involves grammar studies in Spanish. The task proposed by the teacher involved a mix of photo, text, and audio. The students had to produce in pairs/groups and see the colleague’s production in the perspective of we visibility. Thus, considering the aim of the task (produce and share) and based on Figure 3 we suggested the use of Evernote. The age and hybrid access mode criterion was not a problem. However, we had problems with visibility. In Evernote, to maintain the visibility into the we perspective involves that each student needs to connect (invite) his colleague using the colleague’s e-mail. We realized that it was a big effort. However, we understand it is important to promote the group formation and the sharing of productions in a PLE.

Based on these four cases presented here, we can see the importance of using some criteria to select the web tools in educational settings. The use of social software in education is possible but is also a challenge since there are many different tools that can be selected to certain educational practice.

Overall, it was interesting to realize that the students didn’t know the selected tools (Pinterest, Dropbox, Evernote, and GoogleDocs). Therefore, even considering that Brazilian students use the internet, they don’t know many tools and their possibilities as learning tools (ICT Education 2012, 2013). On the other hand, from the perspective of the teacher, we understand that the proposed framework can also guide the first experiences with the use of web 2.0 in education.

Thus, the analysis of the technical characteristics of a web tool based on the proposed criteria (web tool, gratuity, age, communication type, hybrid access mode, and visibility) was important for assisting the teacher in the choice of the tools to be used in the development of learning activities. In addition, students also perceived and became familiar with the establishment of criteria for choosing tools that would foster their PLE.

The case study also allowed the discussion about the tool and the access device, where students and teacher realized the possibilities of the tools considering the use of tablets and laptops.

An interesting aspect of the case studies is related to visibility criteria. As the activities were conducted in groups the visibility-we prevailed, but it was possible to discuss the possibilities and limitations of different types of visibility.

4. Final considerations

Our research aimed to foster educational practices using technologies in the context of the classroom from the perspective of the PLE. Through this perspective we proposed a framework to assist teachers in the selection of web tools for using in the school context to foster educational practices based on PLE, articulating an educational approach and the technical characteristics of a web tool.

Today’s students can be considered hard users of internet (ICT Education 2012, 2013; ICT Kids online 2012, 2013). However, the educational use of internet focuses on research. This way, the teachers have the important role of showing students how they can use web applications in their learning activities. We understand this can be done by promoting activities that explore the potential of cyberspace as a learning space that fosters production, distribution, and sharing of content and knowledge.

The proposed framework was tested in four case studies involving our experiences with mobility and web 2.0 in the final years of elementary school. Results point out that the proposed framework can be used to help the teacher in the design of learning activities through the use technologies, since it proposes a route for the selection of web tools that are appropriated for the pedagogical approach applied in the teaching and learning process under a PLE perspective. The main contribution of our framework is the proposal of an interconnection between the technical characteristics of an application and the learning goals proposed in an educational activity in a way that is easy to apply.

However, besides the 25 top tools for learning used in this study there are many other interesting tools available on the web. Future studies will analyze the potential of different web tools in emergent learning practices and the use of web tools and services by the students, according to their learning necessities, in a PLE perspective.