Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. Rev. vol.34 Belo Horizonte 2018 Epub 20-Set-2018

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698173843

Article

THE DEBATE ABOUT CURRICULUM POLICY AND THE MEANING OF SUPERVISED INTERNSHIPS (1996-2006): AN ANALYSIS BASED ON DISCOURSE THEORY

2Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE/PE), Recife - PE, Brasil

This article describes the results of a research study about Brazil’s debate on curriculum and the meaning of supervised internships (1996-2006), considering the concepts of demands, articulations, and hegemony. We have worked with Ernesto Laclau’s discourse theory arguing that such a debate represents a discursive articulation field. We formulated questions like “Which demands are hegemonized in curriculum policies?” and “How the meanings of supervised internships are built through this debate?” The field of study is the National Association for Education Professionals Training (ANFOPE) and the Ministry of Education/National Council of Education (MEC/CNE). We created a method of analysis based on discourse theory in order to examine the aforementioned debate through the perspective of questioning/deconstructing discourses to reveal how hegemony operates. We found that the meanings of supervised internship result from articulatory practices between different demands produced during it, under the influence of conflictual debate surrounding knowledge, training models and the curriculum.

Keywords: Curriculum policy; Supervised internship; Hegemony

Este artigo trata de uma pesquisa cujo objeto de estudo é o debate da política curricular e os sentidos do estágio supervisionado (1996-2006), considerando demandas, articulação, hegemonia. Formulamos indagações como: quais demandas se hegemonizam nas políticas de currículo? Como os sentidos do estágio são construídos ao longo desse debate? Trabalhamos com a teoria do discurso de Ernesto Laclau defendendo que tal debate é um campo de articulação discursiva. O campo de estudo é a Associação Nacional pela Formação dos Profissionais da Educação (ANFOPE) e o Ministério da Educação/ Conselho Nacional de Educação. Construímos um método de análise com base na teoria do discurso na perspectiva da desconstrução/problematização dos discursos, demonstrando como se opera a sua hegemonização. Os sentidos do estágio supervisionado resultam de práticas articulatórias entre as diferentes demandas produzidas, sob a influência do conflituoso debate em torno do conhecimento/modelos de formação e do currículo.

Palavras-chave: Política curricular; Estágio supervisionado; Hegemonia

1. Introduction

This article describes a broader research study, whose object was the debate on curriculum policy for teacher education programs and the meanings of supervised internships (1996-2006), considering the demands, articulations, antagonisms, and the concept of hegemony within this debate. The perspective adopted in this article is based on Ernesto Laclau’s discourse theory. This framework was used to analyze demands from educational entities related to the National Association for Educational Professionals’ Training (ANFOPE). To achieve this, questions were posed, such as: which demands in curriculum policies are hegemonic? How are the meanings of supervised internship programs constructed within this debate? It is argued that this debate is a field of discourse articulation with hegemonic disputes concerning meaning. Such disputes are based on policies linked to a national project of education in their levels and modalities, a social project, and of a curriculum project to train basic education teachers, carried out by the government sphere of the Ministry of Education/National Education Council (MEC/CNE) and the educational entities linked to ANFOPE.

Considering the scenario of curriculum policy reformulation, the debate on a curriculum policy for basic education teacher training programs is a subject that has provoked serious debate among several educational groups and the government. This is especially due to political disputes regarding social, educational, and curricular concepts and projects to train teachers who make meaning and shape the identities of subjects and objects. They also make changes within the institutional and curricular organization of higher education institutions (IES), which provide initial and continuous training at the university level.

Indeed, the period of this study (1996-2006) was one of extensive reforms to curriculum policies in Brazil. Thus, there were major debates and clashes in which teachers, students, managers, educational entities, and government actors were mobilized within the movement of curricular reform of basic education teacher training courses, mainly in pedagogy courses. In 1996, the National Basic Education Guideline Law (LDBN, Law no. 9394/1996) was a milestone in the definition and organization of Brazilian national education policy. After its approval, a series of regulations from the MEC/CNE regarding teacher training and pedagogy-related courses were established. Moreover, Resolutions CP no. 1/1999, CNE/CP no. 1/2002, CNE/CP no. 2/2002, and CNE/CP no. 1/2006 were implemented, which established the National Curriculum Guidelines for the undergraduate course in pedagogy.

During that 10-year period, many initiatives from MEC/CNE on curricular reform for teacher education courses led to the mobilization of several educational actors in the national academic debate, such as the ANFOPE national meetings, and meetings and public hearings of the National Council of Education (CNE) to discuss the positioning of educational entities regarding the National Curriculum Guidelines for basic education teacher training and pedagogy courses.

In the current scenario, the curricular reforms continue to mobilize the education community, considering the recent adoption of the CNE/CP no. 2 resolution by the MEC on July 1st, 2015, which defines the new curricular guidelines for initial and continuous training in higher education. It indicates the direction of the current curriculum policy debate. This resolution incorporates old demands from ANFOPE, revoking Resolutions CP no. 1/1999, CNE/CP no. 1/2002, and CNE/CP no. 2/2002, as all of them created conflicts and hegemonic disputes of meaning between the education community and the government. Therefore, it is in this context of serious disputes and the creation of new curriculum policies in which the present study was conducted, that is, the debate on curriculum policy for teacher education programs (1996-2006). As mentioned above, this debate analysis is based on the discourse theory of Ernesto Laclau. The debate is viewed as a field of discourse articulation with disputes over hegemonizing certain educational, social, and curricular projects concerning the training of basic education teachers.

Categories like discourse and hegemony, and other concepts of discourse theory such as articulation, contingency, nodal points, antagonism, demands, floating signifiers, logic of difference and equivalence, among others, will be covered. These concepts enable an understanding of the social aspect and the curriculum policy for teacher training as discourse relations that are based on hegemonic disputes of meaning.

In line with other studies on curriculum policies (LOPES; MACEDO, 2011a; LOPES, 2004; 2006; 2007; 2010), and taking a post-structural/discourse perspective on curriculum (LOPES; MATHEUS, 2014; LOPES, 2013; CORAZZA, 2004), it is believed that the debate on curriculum policy lies within a discursive materiality, in which control over the forms of meaning is never total, but is always partial and contingent. This is because within the unstructured structure, multiple decisions may be taken, and there is only difference. If there are strong hegemonies and seemingly essential, stable identities, there is always a meaning that escapes control, as noted by Lopes and Macedo (2011a). It must be pointed out that no discourse can be understood outside of the material relationships that constitute it. Moreover, the focus on hegemony in politics remains; what changes is the way that hegemony is regarded: “From a construction founded on the economic structure, with Antonio Gramsci, to an articulation that provides a framework for a provisional, contingent discourse” (LOPES; MACEDO, 2011a, p. 236). By incorporating a post-structural/discursive curricular stance, the essentialism in the meaning of curriculum, the metanarratives that largely penetrate the basic categories of critical curriculum discourses are questioned. In addition, the attempts at closure of meaning with a centered curriculum are examined. Furthermore, the “language games” of Wittgenstein (2013) and the practice of discourse articulation of Laclau and Mouffe (1987) are sources of inspiration, in which the meanings are defined by the language game rules, with no fixed structures, but only discursive structuring and restructuring.

2. The social is discursive

According to discourse theory, the social is discursive, that is, the social reality is discursive, which results from articulatory practices. Discourse is practice; it is an articulation of meanings that encompasses discursive and non-discursive dimensions. This question refers to the very nature of the concept of discourse, where the objects are found within a discursive condition. That is, they depend on the structuring of a discursive field, creating “language games,” which may produce new contingent meanings. In the sense proposed by Wittgenstein (analytical philosophy), “language games include a totality inseparable from language and actions” (LACLAU; MOUFFE, 1987, p. 183). These authors agree with Wittgenstein, since they say that the material properties of the objects form a language game, which is what they call speech. This means that the meanings “are not merely juxtaposed, but they constitute a differential, structured system of positions - that is, a discourse” (LACLAU; MOUFFE, 1987, p. 184).

The discourse category leads to the underlying conception of society, that is, it comprises all dimensions of social reality, not only writing, speaking, and communication practices (HOWARTH, 2008). Discourse is not understood as a set of texts, but as a category between words and actions of a material nature, not mental and/or ideal (MENDONÇA, 2009). According to Laclau (2011b), social relations are discursive; they are symbolic relationships made of processes of meaning. Emphasizing the ontological dimension of the social aspect, Laclau aims to affirm the meaning of all objects and practices, and to show that every social meaning is contingent, contextual, and relational. He argues that any system of meanings is based on a discursive exterior, which it partially constitutes.

In summary, every social setting is a significant configuration (LACLAU, 2000) in which the social aspect is discursively signified. It is an ontological field, a space for reflection of the being while being, making articulatory practices and social senses - a system of socially-constructed relations. This leads us to conclude that in an analysis based on Laclau’s discourse theory, “there is no way of previously making social meanings or considering identities or totally constructed social movements created with ever-present political projects” (MENDONÇA, 2007, p. 250).

To bring the theoretical discussion and curriculum policy closer together, “the discourse is a relational totality of signifiers that limit the meaning of certain practices and, when hegemonically articulated, they constitute a discursive formation” (LOPES; MACEDO, 2011a, p. 252). Discourse is regarded from multiple senses that articulate with endless possibilities of making a hegemonic, contingent discourse. Understanding the multiple determinations of a social phenomenon, this debate, and the social and historical conditions in which they are given, means understanding how all of this is signified. Such meaning is given by a discourse that establishes rules for the production of meanings.

In line with discourse theory, curriculum policies can be seen as the outcome of negotiations of meanings, and discursive articulation for the provisional closure of structures, since there is a discursive field that aims to establish meaning. This closure is performed by concrete subjects who decide within the undecidable space of a displaced structure. In other words, in the process of political struggle, certain educational groups articulate with each other in a provisional, contingent way to stand for their different demands and projects for society, education, teacher training, and curriculum. Hegemonic practices entail the displacement of a set of demands from one social place to another, or from one group to another (LACLAU; MOUFFE, 1987; HOWARTH, 2008), through a process marked by negotiation and disputes concerning different projects.

In this game of political decisions, various authorships are found with multiple discourses that evoke a process of the construction of meanings in disputes over hegemonic projects, such as in the context of teacher training curriculum reformulation. Therefore, there is a context in which there are several producers of texts and discourses - governments, academia, educators, the media, social groups, and their interpretations - with asymmetric powers, but their identities are formed through the process of political struggle, as highlighted by Lopes and Macedo (2011b).

3. Hegemony: A new logic of social constitution

It is in this context that discursive demands, antagonisms, and hegemonic identities are identified to demonstrate how discourse hegemony occurs. The concept of hegemony is important. Based on a deconstructive reading of Gramsci and, in general, the Marxist tradition, Laclau and Mouffe (1987) formulate the concept of hegemony as a new logic of social constitution. The authors recover the theoretical framework formulated by Gramsci, especially its conceptualization of hegemony, highlighting the limits of Marxism to reflect social configuration. They mention the theoretical contributions from post-structuralist trends like psychoanalysis with the Lacanian theory, the “deconstruction” of Jacques Derrida, as well as contributions from the analytical philosophy of Wittgenstein and Heidegger.

Laclau and Mouffe (1987) critique Marxism for its incapability of understanding contemporary social relationships. Marxism is attached to an essentialist conception of society, founded on the reductionist logic of social relationships linked to capital versus work antagonism (MENDONÇA, 2009). In contrast, the authors discuss the plural and multifaceted character of contemporary social struggles. Consequently, the same wealth and diversity of contemporary social struggles have been generating a theoretical crisis (LACLAU; MOUFFE, 1987).

There is a social complexity consisting of infinite identities originating from antagonistic discourse relations unlike mere class antagonisms. According to Laclau and Mouffe, they feature a particular locus but no universal a priori. Their analysis identifies the transformations in the concept of hegemony. They claim that behind the concept of hegemony, there is something more than a type of political relationship complementary to the basic categories of Marxist theory, which introduces a social logic incompatible with the latter (LACLAU; MOUFFE, 1987). In this study, the critique of the Marxist tradition by Laclau and Mouffe is assumed when they question the essentialist view of the role of economics in social relationships. They deconstruct Marxist categories (from the perspective of Derrida), such as hegemony and universal class, in light of the social relationships and historical processes of contemporary societies.

Since this study is situated within the politics of curriculum policy, it is necessary to discuss the concept of policy according to discourse theory. Laclau and Mouffe defend politics as a social ontology. They claim that the economic basis is politically constituted in a hegemonic way, and the constitution of political subjects does not directly occur through a liaison with production relationships, since those positions do not ensure these subjects’ antagonism toward capitalism. This antagonism can be produced by other positions, such as gender or race, which thus depends on contingent dynamics, as stated by Lopes (2006).

According to Laclau (2011a), such antagonism is like a constitutive exterior that blocks the identity of the inside. The denial comes from the exterior, that is, from another speech that denies and threatens the existence of all the elements of a specific discourse. The antagonism is constitutive; every discursive constitution is antagonistic. Furthermore, the constitution of a new hegemony occurs by articulation processes in which the hegemonic identity is not constituted a priori, from the outside of the process. In addition, a given peculiarity can take a certain level of temporary, reversible universality.

Curriculum policy represents a struggle to define the nature of training, curriculum, teaching practice, and even pedagogy courses themselves. It is a political game that produces meanings for teacher education courses. The contingent marks of its constitution must be shown. A way of understanding the incompleteness of the meanings or the non-closure of meaning, as well as the struggles and political arrangements (LACLAU, 2011a, 2008) within the discourses are adopted in the present study. The method of analysis based on discourse theory is presented in the following section.

4. Discourse theory and the method of analysis

As a theoretical and methodological approach, the discourse theory of Ernesto Laclau is the reference for analyzing the object of study, that is, the debate on curriculum policy and the meanings of supervised internships (1996-2006). Discourse, demands, articulation, antagonism, hegemony, logic of difference and equivalence, antagonistic borders, and other concepts of discourse theory (such as contingency, nodal points, and floating signifiers) were selected as analytical categories for the present study.

A method of analysis was built from the theoretical framework of discourse theory. This method is not to be confused with other varieties of discourse analysis such as French discourse analysis, Norman Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis, or Michel Foucault’s archaeology of discourse analysis. Similarly, our method of analysis is not based on Howarth’s (2005) articulatory practice method, the objective of which was to start the process of rectification of the methodological deficit by studying the way discourse theory is applied to empirical objects of investigation. Although this method was studied, and it was a source of inspiration in some parts of this research, it is not the central focus of the present study. Rather, discourse theory and its analytical categories applied to the object of study are the focus. Discourse theory is a foundation for elucidating the articulation among opposing discourses, and consequently, the transformation of identities and practices.

In this respect, it is believed that an innovation is presented herein pertaining to the method of analysis, since one was created from Laclau’s discourse theory and its system of ontological assumptions and theoretical concepts, which were applied to the present study’s analysis. At the first level of analysis, demands, antagonisms, and hegemonic disputes of meaning in documents of educational entities are identified. They are analyzed from the perspective of discourse problematization and deconstruction. At the second level, we analyze the hegemonic processes in documents of the MEC/CNE, from the logic of equivalence and the logic of difference.

The object of study is viewed as a peculiar field of meanings produced in a given historical situation: the context of teacher training curriculum reformulation, consisting of political forces and educational actors who dispute the hegemony of meaning. In accordance with Howarth (2005, p. 39), “all objects and practices have a meaning and the social meanings are contextual, relational, and contingent.” It is a symbolic object, defended as a discursive practice and a locale for a hegemonic dispute over signification. This evokes the conceptualization of curriculum as follows: “as a place of knowledge, the curriculum is the expression of our conceptions of what constitutes knowledge” (SILVA, 2010, p. 63). Like language, “as a place of knowledge, the curriculum is the expression of our conceptions of what constitutes knowledge” (SILVA, 2010, p. 64), but is conceptualized as a place of the production of meanings. The philosophers of language critique the metaphysics of language, and they conceive language as a contingent game. From this perspective, “one will never know what this world really is or how it works” (VEIGA-NETO, 2003, p. 13). There is an incompleteness in what is said, which does not stem from some alleged incompleteness of human understanding of what is said, but from the language in which what is said is housed (VEIGA-NETO, 2003).

To paraphrase Veiga-Neto (2003), this has consequences for the ways of conceiving knowledge and curriculum, since it is not our place to say what the world is; the most one can do is show that the world consists of ever-contingent language games, with multiple possibilities of meaning. In this sense, the linguistic turn “solved the problem of the incompleteness of languages, dissolved the impossibility of the sufficient translation, and posed new challenges to us” (VEIGA-NETO, 2003, p. 14).

Regarding the ways of conceiving curriculum, as stated by Lopes and Macedo (2011a), the curriculum is neither fixed nor is it a product of the struggle outside of school concerning what is legitimate knowledge. The curriculum is not a legitimate part of culture that is transposed to the school. The curriculum is part of the struggle for the production of meaning, the struggle for legitimacy. The theoretical device considered in the present study and the analytical categories applied herein lead to the apprehension of articulatory practices of meaning, practices that are found in the conflicting debate on curriculum policy. These are articulatory practices of meaning that seek hegemony, a result of the dialectical relationship between the logic of equivalence and difference. According to Laclau and Mouffe (1987), they can build meanings, identities, and practices. This debate is understood as discursive articulation. In the following item, the research corpus is presented.

As for the constitution of the corpus of analysis, according to discourse theory, all data are considered as internal components of a discourse (HOWARTH, 2005). The analytical corpus is as follows: a) curriculum documents from the MEC/CNE from the period of 2001-2006, totaling nine Opinions and Resolutions; b) documents of educational entities in the educational field such as ANFOPE, ANPED, ANPAE, CEDES, FORUMDIR, FORGRAD, the National Forum in Defense of Teacher Training, the Committees of Pedagogy Teaching Experts and Teacher Training Experts, and the Working Group of Teaching Degrees in the form of bulletins, letters, proposals, manifestos, and theoretical stances on undergraduate course reformulation for teacher training in the period of 1996-2006, totaling 17 documents.1

These documents contain definitions of teaching, curriculum demands, social projects, education, training, and curriculum, discussions on the locus of teacher training, antagonisms regarding the emergence of IESs as spaces for teacher training programs, the relationship between bachelor’s degrees and teaching degrees, the profile and identity of pedagogy courses, the qualifications for entry into pedagogy, teacher training, and other teaching degree programs, institutional and curricular organizations, and conceptions of teaching practicums and supervised internships for the training courses, among others.

The period from 1996 to 2006 was a time of significant curriculum reforms, debate, and the elaboration and approval of Law no. 9394/96 and two national curriculum guidelines: the National Curriculum Guidelines for Basic Education Teacher Training and the National Curriculum Guidelines for courses in pedagogy. Therefore, that was a period of substantial curriculum definitions, when the selected documents established guidelines, principles, and standards for teacher education programs.

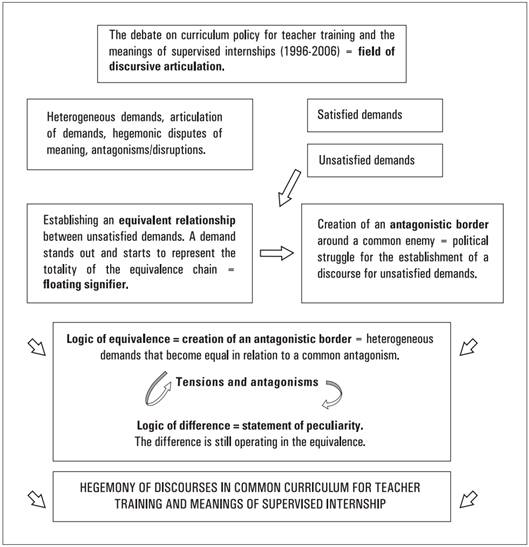

It may be said that discussions on methods in discourse theory are part of an ongoing, open-ended conversation. Consequently, ways continue to be paved, in the sense proposed by Duque-Estrada (2004, p. 33), “to go on the track, which is never done without risks, as the one where we are and always have been, whatever the area explored.” Figure 1 presents an illustration of the method of analysis used in the present study.

Source: Adapted from LACLAU, Ernesto. La razón populista. 6th reprint. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2011a.

Figure 1 Analysis graph

5. Demands of educational entities within the debate on curriculum policy (1996-2006)

To identify demands, antagonisms, and the hegemonic disputes of meaning in the debate on curriculum policy in the context analyzed in this study, the analytical categories of discourse theory were employed, including hegemony, articulation, demands, contingency, floating signifiers, universalism and particularism, the notions of policy and politics, and the logic of equivalence and difference. This was done to clarify the theoretical and curriculum disputes and the hegemonic identities within the teacher training debate. It is believed that this debate presented itself as a place of intense disputes and conflicts between the government (MEC/CNE) and education spheres. The disputes take place in relation to hegemonic projects of society, education, training, and curriculum, with the influences of the academic debate being felt at the national and international levels. This study was guided by the following questions: What are the curriculum approaches that dispute hegemony? How are they articulated? Which projects of society, education, training, and curriculum clash? Which political discourses are they based on? What are the concepts of teaching? What are concepts of pedagogical practice and supervised internship? How are the meanings of the internship constructed in this debate

From the perspective of discourse theory (LACLAU, 2011a, 2006), a variety of demands, or even a plurality of positions in discourses are found in the documents of educational entities. According to Laclau (2006, p. 22), “a unit is not given by only one subject position, but by a plurality of subject positions that begin to establish a certain degree of solidarity among themselves.” This is how the concept of demand and chain/relation of equivalence established among them is to be understood. According to discourse theory, if a specific demand is not satisfied, other demands that are also unsatisfied and different from each other get together and create a basic feeling of solidarity among themselves. From the standpoint of the peculiarity of these demands, they may be entirely different from each other. However, from the perspective of opposing the system - understood as the “enemy” that these demands are opposing - they end up establishing a relation of equivalence.

According to Laclau (2006), if the demands are individually met, there will be no equivalence among them. However, if the demands are not met, a relation of equivalence begins to form. If the chain of equivalence stretches far enough, it must be represented symbolically as a whole. This representation occurs through individual demands, that is, a certain demand takes the supplementary function of representing the totality of the chain of equivalences. Consequently, they will represent something more comprehensive. The particularity that a universal function takes is what Laclau calls hegemony. To organize the diversity of demands made by the educational entities related to ANFOPE, the themes were grouped and extracted. The themes consisting of the demands in the documents of educational entities are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Themes of the demands made by educational entities

| Curriculum: Educational principles and foundations of teacher training/Common National Core and Electives (BCN) |

|---|

| Teaching as a foundation of training and identity of the education practitioner |

| Training places for education practitioners |

| Pedagogical practice and supervised internships |

Source: Documents of educational entities.i

The curriculum theme was chosen for its complexity and its encompassing of the whole the teacher training/pedagogy course reformulation debate in the context analyzed in the present study. The themes extracted from the documents of educational entities are closely interrelated, and they add a range of diverse demands, which demonstrates the concepts relevant to the understanding of the curriculum policy debate and the meanings of the supervised internship. They were separated as a didactic way of organizing the data to facilitate analysis.

To begin, a theme that requires the Common National Core (BCN) for teacher training will be examined. It is a broad, complex concept that articulates various demands, being reaffirmed in all final documents of the national meetings of ANFOPE analyzed in the present study. The BCN is presented as a demand that disputes the hegemony of a national teacher training curriculum project. Furthermore, all topics listed in Table 1 are related to the BCN for the curricula of basic education teacher training. Subsequently, the meanings of the supervised internship constructed throughout this debate will be discussed.

6. The Common National Core (BCN): An analysis from the perspective of hegemony and the deconstruction of discourses

The concept of the BCN was originally linked to a historic demand of the educators’ movement, that is, the identity of the pedagogy course/conception of pedagogue/extinction of qualifications:

The Common National Core, a concept that has been collectively developed within the movement of teacher training curriculum reformulation {...} started out at the First National Meeting of Belo Horizonte in 1983, as an opposition to the concept of the teacher as a generalist, who did not consider ‘being a teacher’ during preparation for teaching (ANFOPE, 2000, p. 10).

The struggles fought by the movement within the pedagogy course - specialist vs. generalist, professor vs. specialist - brought to light the common questions related to training educators in pedagogy and teacher education courses. The BCN is closely linked to the thesis of teaching as a foundation for training and professional identity of every educator, and it requires unity in the process of training licensed teachers. The concept stands as a principle of basic training, a body of knowledge that expresses its antagonism to the model of minimum curriculum; it is in favor of an articulation between theory and practice and education-society relationships. Throughout the debate, ANFOPE deepened this concept so that the BCN was not restricted to training the pedagogy course practitioner, rather, so that is was common to all training courses and education practitioners:

Base: the foundations of vocational training, with teaching as a foundation for such training; common: because it is present in all the instances of professional training; national: because it unifies the struggle in defense of professionalization, respecting diversities of times and spaces of training at institutions (Bulletin of ANFOPE, Year IV, n. 8, 1998, p. 2, author’s emphasis).

Furthermore, the amplitude of the concept places it as a way of struggling against the degradation of the teaching profession, adding demands such as the fight for a global policy on teacher education programs, training conditions, teaching as a basis of training, and the defense of teaching training policies.

The content of the formulation of the Common National Core is an instrument of struggle and resistance against the degradation of the teaching profession, enabling the organization and claim for professionalization policies that guarantee equal training conditions (...) (ANFOPE, 2000, p. 9, author’s emphasis).

It is also linked to the demand for the professionalization of teaching, which enables teachers to “radically embody the proposals of the professionalization of teaching, providing them with the content that the educators’ movement has been building throughout its history, which seems to be the current challenge” (ANFOPE, 2000, p. 9). While it is expressed to be the core of all training courses, the BCN emphasizes the respect for the specificities of each course/training instance:

There will be a single Common National Core for all teacher training courses. This common core will be applied at each institution to respect the specificities of several training instances (Normal School, BA in Pedagogy, other in specific BAs) (ANFOPE, 1992, p. 14, apudANFOPE, 1998, p. 11).

Since the post-structuralist approach from the perspective of hegemony and the deconstruction of discourses was adopted in this study, symptoms of undecidability and fluctuations of meanings in discourses herein analyzed were identified. Thus, it was possible to identify a certain ambiguity in the BCN discourse. While it is expressed as the basis of all training courses, it emphasizes the obedience to the specificities of each course/training instance. Thus, the common national curriculum is considered a curriculum discourse that strives to be hegemonic. Moreover, it borrows the expression used by Lopes and Matheus (2014): it is a project that seeks to find a curricular centrality by mechanisms of articulation of different demands, antagonisms, and disputes within the teacher training debate in the period 1996-2006.

In addition, the BCN aggregates the demand in defense of the unified training of educators, contrary to the minimum curriculum. It supports a pedagogical project common to teacher training courses, and founded on the same basis:

The conception of a common national core {...} represents a break with the idea of a minimum curriculum that predominated in the organization of undergraduate courses until recently, when it was replaced with the concept of curriculum guidelines {...} (ANFOPE, 2006, p. 9).

Regarding the theoretical perspective of curriculum, the BCN owes to the sociohistorical education perspective and critical pedagogy developed by Saviani (2012). Being influenced by Marxist thought, the BCN presents itself as a guideline that is supposed to permeate the teacher training curriculum (ANFOPE, 1998), encompassing a sociohistorical concept of training, education, and educators.

From a perspective of a critical and transformative education, the construction of a sociohistorical concept of an educator must be restated. This is a concept of teacher training in a broad sense {...}, with a critical awareness that enables it to interfere and transform the conditions of school, education, and society (ANFOPE, 2000, p. 9, author’s emphasis).

Considering the context of discursive articulation, the multiple possibilities of meaning and various curriculum demands that are found in the contingent political game, the foundation of the critical conception of historic pedagogy or the sociohistorical concept of educator/education/curriculum must be questioned. Following this reasoning, one could question the project of centered curriculum, which aims to ensure an a priori training of identities as one among several. Moreover, one could question a curriculum that aims to ensure training in subjects capable of transforming society (as the interest of the majority of population) (LOPES, 2010) as one among several, which disputes the hegemony of discursive meaning in a differential context. This is a conception of curriculum within the contingent political game, with the articulation and negotiation of meanings.

Establishing the connection between theories of curriculum and curriculum policy, the perspective of curriculum defended by ANFOPE owes to more general critical theories on education and curriculum. Such a perspective is reaffirmed in all the documents analyzed, with the support of Marxist and critical-reproductivist education theories. It is known that until the mid-1990s, critical thinking was dominant in Brazil’s curriculum theory and policy, in an attempt to invert the basis of traditional curriculum theories. Regarding a political and social outlook on education, the BCN is engaged in a social/educational project linked to the transformation of school and society. “The position historically adopted by ANFOPE displays a project of teacher training that relates to the challenges of a wide and profound transformation of school and society” (ANFOPE, 2002, p. 12).

ANFOPE reinforces the political and social dimensions of education, emphasizing the close link among the school organization, capitalist society, and the class perspective. The struggle for curriculum reformulation is related to a project of transformation of society, as possibilities to influence democratic projects and social justice:

{...} the fight for reformulation of teacher training courses is constant, continuous; It is endless. It is part of a broader movement of Brazilian educators, which is part of the movement of workers for the construction of a fairer, more democratic, and egalitarian new society (ANFOPE, 1998, p. 8).

This leads us to assume the interpretation of politics and policy in the logic of hegemony, as posited by discourse theory, and to consider the political dimensions of curricula in the debate. According to Laclau, politics is constitutive of the social aspect, conceived as decision-making in an undecidable terrain where power is constitutive. The curriculum policy linked to a project of justice and democracy is an impossible project, since “it is impossible to assume fixed foundations - knowledge, values, practices, relationships, institutions - defining once and for all the political character, in any social context, in any constitution of the social aspect, for all social groups” (LOPES, 2014, p. 56). However, “impossible is not the simple opposite of possible, but the expression of an opening of multiple unforeseen possibilities” (LOPES, 2014, p. 56).

It is within politics as a process of signification where the meanings of social justice and democracy and so many other demands are created. The question is: “one does not act upon the present to achieve identification of curriculum and social values previously designed in the future, but a meaning that is not determined, and will produce unexpected effects is decided today” (LOPES, 2014, p. 59). The demand for a common national core is thought to be a political decision, which consists of a way of struggling for occupying spaces that are temporarily empty, that is, the struggle for the hegemony of a teacher training curriculum project that is always precarious and contingent. This study supports the view of the curriculum as a political act of signification amplified by the absence of predefined horizons and foundations. This understanding “contributes to the hindering of the possibility of a foundation such as the right, final reason to organize the curriculum in a certain way” (LOPES, 2014, p. 48, author’s emphasis).

The terms “hegemony” and “deconstruction” are restated as two sides of the same coin; that is, “deconstruction,” which displays contingent relationships of an identity inasmuch as other articulations - equally contingent - also demonstrates its possibility. This is deconstruction because it is possible to critically rethink propositions about knowledge, training, curriculum, teaching, and exercising critical thinking regarding the pretense of truth, autonomy, and essentialisms in discourses with which we are confronted.

As a political, contingent decision, the concept of a common national core is a demand whose body is divided, transforming its peculiarity to define a hegemonic project for the teacher training national curriculum. This stems from a series of articulations among different demands, given through clashing with competing forces, in a political game of production of (provisional) meanings concerning the curriculum. The BCN as a peculiarity takes the function of representing something greater, more comprehensive in the field of disputes discourse in the context of curriculum reform of teacher training, aggregating a plurality of meanings as shown in the documents of ANFOPE. The BCN represents the search for a hegemonic identity that is like a floating signifier, which divides its body into a dispersion/articulation of senses, transforming its own peculiarity into the embodiment of an unreachable totality.

As exposed in the present study, there are so many demands on the BCN that it lacks meaning.2 It is through this emptiness and non-completeness that the BCN becomes able to gather different demands and constitute different subjects that act in its name. In this perspective, the BCN is a mechanism for constituting the hegemony of a centralized curriculum policy. A sense of negativity is not to be associated with its emptiness, but this study aims to demonstrate how hegemony in the theory of discourse operates. The table below shows how the BCN is problematized in this study as a floating signifier.

Table 2: The Common National Core: A floating signifier

| Particularity/own content/meaning/name |

|---|

| Universal representation of totality; diversity of demands; it attempts to compensate for the lack of fullness in an incomplete way |

Source: Adapted from LACLAU, Ernesto. La razón populista. 6th reprint. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2011a.

The constitution of the BCN for the teacher training curriculum is impossible, as it is impossible for society to fully constitute itself from the standpoint of the completeness of its meanings. The completeness of meanings is impossible in the discursive field of training curriculum policy, marked by contingency and multiple possibilities of meaning. That is, the closure of significant totality in a relational system of differences is impossible. In conclusion, there is no space in the discursive logic of a centralized curriculum, inasmuch as there is no closure. Nevertheless, there is only a precarious, contingent closure, where there is an openness to multiple possibilities.

However, the BCN has an identity that aims to be hegemonic in the field of curriculum policy, from the perspective of relational logic. It is an incomplete identity, since it is penetrated by contingency. Even though the BCN stands out as a hegemonic curriculum identity, its full presence is impossible in the face of its structural incompleteness. Nonetheless, there is a tension or even paradox between the impossibility of the closure of meaning and the contingent need for this closure or fixation, since it is this apparent closure that will enable the hegemony of certain discourses in curriculum policies. Furthermore, in this apparent closure of the totality of meaning, there is a heterogeneity of demands in which the differences and antagonisms become present within a given hegemonic field, always making these fixations or restraints partial and precarious.

Problematizing the BCN does not necessarily entail the abandonment of its principles. However, this is a new way of problematizing/deconstructing its themes/contents, that is, displaying its hegemony from a different perspective, supported by a set of categories with possibilities of questioning.

7. The meanings of supervised internship in the curriculum policy debate

In this section, the demands linked to supervised internships in educational entity documents are identified to highlight the meanings constructed in the curriculum disputes that took place, especially with MEC/CNE. In addition, the influences of educational groups are examined. What are the demands placed on the supervised internship? How are the different demands articulated to produce meanings of the supervised internship? What are its theoretical foundations? What is the influence of the academic debate at the national and international levels on the production of meanings of supervised internships? What is the concept of knowledge upon which the meanings of the internship are founded?

The theme of supervised internship/pedagogical practice have been linked to different demands and curriculum disputes in the debate with MEC/CNE in the process of training course curriculum reformulation. The signifier internship appears in the articulator axis of the BCN, related to themes such as unity between theory and practice, work as an educational principle, and the relationship between university and school and education and research.

The unity between theory and practice implies taking a stance in relation to the production of knowledge. This pervades the course curriculum organization, and it is not to be restricted to a mere juxtaposition of theory and practice in a curriculum; theory and practice that permeate all the training courses, not only teaching practice {...}, reviewing the stages and its relationship with the public schools and the way the teachers’ work is organized in the school; and emphasis on research as a means of producing knowledge and intervening in social practice (ANFOPE, 1998, p. 12).

Moreover, the meanings of the internship are linked to the defense of new curricular experiences that facilitate the contact of students with the practice from the beginning of the course, having research as a formative principle, ways of democratic management, and others, as shown by the excerpt below:

{...} the creation of curricular experiences that enable the contact of students with the reality of the basic school from the beginning of the course; the incorporation of research as a training principle; the possibility of students’ experiencing ways of democratic management; the development of social and political commitment of teachers; a reflection upon teacher training and their work conditions; {...} (ANFOPE, 2000, p. 37, author’s emphasis).

The signifier supervised internship is also linked to a discourse of rupture with the current forms of curriculum organization, as shown by the excerpt below:

The rupture with the current forms of curriculum organization may create the necessary conditions for certain activities to be experienced together by all students of training courses/programs, including the formative content of the elementary areas and others - such as initiation into research, pedagogical practices, experiences and professional internships, management, and organization of the pedagogical and school work (ANFOPE, 2000, p. 35, author’s emphasis).

Such discourses were restated by ANFOPE (2000), and the internship was related to issues such as an articulation between the curriculum components of specific pedagogical training, a relationship between theory and practice, and university and education systems. Consequently, the meanings of the internship are constructed with demands like the relationship between theory and practice throughout the training course, teaching, research, and university and school, among others. They oppose “the current ways of organizing, especially teaching degrees whose current structure fragments and separates the subjects of specific content from courses of pedagogical, educational content, theory and practice, research and education, and work and study” (ANFOPE, 1998, p. 12).

A theoretical training that entails an articulation between theory and practice, curriculum components of pedagogical training and specific training, and places an emphasis on research are key demands of ANFOPE. This is reaffirmed throughout the debate as follows: “the training of education practitioners for all levels of education should be founded on the relationship between theory and practice, education and research, specific content and pedagogical content, to meet the nature and specificity of the educational work” (ANFOPE, 1998, p. 9).

However, it is in the guiding document for devising the curricular guidelines for the teacher training, GT Teaching Degrees, established by Secretaria de Educação Superior/Ministério da Educação (SESu/MEC), and forwarded to the CNE on September 15th, 1999, that a formulation of a more specific internship discourse is found. Concepts, purposes, and procedures in a curricular structure that articulates professional experience and practice in training are also found:

The integration between theory and practice is a request in the teacher training process. Hence the need for the curriculum to include a continuous, permanent process of teaching practice, which should be understood as a mediation of teaching and learning in which the core of making things concrete, guided by theoretical knowledge, may integrate and consolidate professional training (GT Degrees, 1999, p. 7).

The teacher training curricula “should be organized with a direct link to schools and other existing bodies. The courses must establish partnerships with these bodies within the education system and society, devising a pedagogical training project with them (...) (the curriculum) should be organized to ensure that students and teachers alternate their time in the training course and schools within the education system” (GT Degrees, 1999, p. 8). From the standpoint of a teacher training curriculum that is founded on the relationship between theory and practice, education and research, and specific content and pedagogical content (ANFOPE, 1998), the supervised internship is regarded as one of the curricular components of a training that provides knowledge about the professional reality of teaching. Thus, the internship is interpreted as a field of knowledge that involves reflection and questioning of the situations of teaching and learning, that is, it is reflection on the teaching practices and collective work taught in the course. Table 3 shows the demands on the internship and the meanings constructed by educational entities:

Table 3 Demands related to supervised internships in documents of educational entities

| Internship as a mandatory curriculum component of training courses/field of knowledge |

|---|

| Internship from the beginning of the training |

| Internship: a relationship between theory and practice, education and research, and university and school |

| Internship as a training space and reflection on pedagogical practices |

| Internship as a pedagogical practice modality |

| Internship as an interdisciplinary space and the collective work of teachers |

| Internship as a space for constructing the teaching profession and its professionality |

Source: Documents of educational entities.3

Regarding the theoretical-curricular perspective, on which the meanings of the pedagogical practice and supervised internship are based, they stem from the sociohistorical perspective of education presented by Saviani (2012), as does the BCN. They are grounded in the “dialectic/pedagogical or historical/critical concept” (SAVIANI, 2012, p. 69). This is an ideological perspective of education and pedagogical practice, grounded in critical curricular theory. Considering the concept of dialectic pedagogy, Saviani defines pedagogical practice as historical-critical. It is inspired by the Marxist tradition and the Gramscian sense “of superior development of the structure into superstructure in the consciousness of men” (GRAMSCI, 1978 apudSAVIANI, 2012, p. 113).

In addition, the influence of the academic debate at the national and international levels on the meaning-making of the supervised internship must be highlighted. The meanings expressed in Table 3 are widely developed in the academic debate, with authors such as Pepper (2011), Fiorentini (2004), Lüdke (2013), Silvestre (2011), Venturim (2009), Pimenta and Lima (2008), Diniz-Pereira (2008), among others. Their propositions discuss teacher training from the relationship between theory and practice, teaching and research, reflective pedagogical practice in training courses, the construction of professional identity and teachers’ knowledge, and training teachers as researchers in their own practice, in which the supervised internship emerges as a privileged space to enable such actions.

Consequently, new meanings will be assigned to the supervised internship, identifying it with a body of knowledge that is founded on the relationship between theory and practice, centered on research, developed from reflection contextualized in action, as action and knowledge in action, as an approximation of professional reality, as a critical reflection and intervention in school life, as a space for production of new knowledge about school and pedagogical processes, and as research, among other meanings. Such meanings are sheltered in the theoretical part presented by Donald Schön (1992) on the training of practical, reflective teachers, and the knowledge built in the action-reflection-action cycle.

Similarly, these meanings are found in the perspective developed by Lawrence Stenhouse (1975) on teacher-researcher training, that is, the possibility of research during training and teaching practice as an instrument of the construction of teacher autonomy expressed in the development of dispositions for production and reconstruction of knowledge and changes in the teaching practice (VENTURIM, 2005). On the other hand, the meanings of supervised internship find their theoretical foundations in authors that had a great influence in Brazil, such as Zeichner (1993), Pérez-Gómez (1992), Nóvoa (1992), and Contreras (2002). They critically review the pragmatic development of the model of teacher training as “practical-reflective.” To them, the discourse of teachers as “reflective practitioners” is innocuous when there is no critical reflection on the practice as socially and historically situated. The need to reflect upon teaching and the social conditions that surround it, with the teacher’s political vision of the work must be pointed out. The reflective practice must be transcended in an individual way for a reflection that includes social reconstruction.

Arguably, such theoretical aspects regarding the training of teachers inform the very conflictual debate on knowledge in the curriculum. As previously mentioned, this is a debate in which there is no consensus, only hegemonic disputes over meaning. In the case of the teacher training curriculum, the knowledge considered valid is practical, built within action-reflection-action; sometimes knowledge is critiqued as practical-reflective. It should be elevated to a political and social reflection upon the teachers’ practice; however, the different models sometimes blend, producing a certain hybridity of discourses.

Considering these issues, the meanings of the internship are constituted in the way of conceiving knowledge in the field of teacher training curricula. Since a post-structuralist reading of the curriculum as a discursive practice was considered, this is an endless political game of production of meanings and disputes for its own legitimacy. The theoretical aspects described above, upon which the supervised internship builds its foundations, aim to define knowledge that is valid and legitimate to the detriment of others; they classify/categorize different kinds of knowledge as if they were fixed. As we have argued, the curriculum is neither unique nor fixed. The rules are formulated in the political struggle for contingent meaning.

8. Conclusions

In this article, the curriculum policy debate and the meanings of supervised internship (1996-2006) were analyzed, considering demands made by educational entities linked to ANFOPE. The course of analysis that was built from the discourse theory of Ernesto Laclau was presented, which is applicable to the aims of the research. By adopting a post-structural, deconstruction/discourse hegemony perspective, some of the curriculum demands formulated by ANFOPE were questioned, such as those of the BCN and the meanings of the supervised internship. The BCN was identified as a floating signifier that divides its body between particularity and a wider representation. The BCN is a discourse/hegemonic curriculum project that searches for curriculum centrality by articulating different demands and considering antagonisms and disputes of meaning in the teacher training curriculum policy debate.

From a discursive perspective, the constitution of the BCN for the teacher training curriculum is impossible, because the completeness of meanings in the field of discursive articulation of teacher training curriculum policy is also impossible. However, we highlight the tension between the impossibility of closure of meaning and the contingent need of this closure. This apparent closure of meaning will enable the hegemony of discourses in the curriculum policy, albeit temporarily. To ANFOPE (2000), both the BCN and the teachers as a base are a starting point for devising new guidelines for all teacher training courses. That is, it is those demands that stand out and achieve the hegemony of discourses in the MEC/CNE curriculum policy, as expressed in the CNE/CP Resolution no. 2, July 1st, 2015 and CNE/CP Resolution no. 1, of May 15th, 2006.

Regarding the meanings of supervised internship, they result from articulatory practices among different curriculum demands produced throughout the teacher training curriculum policy debate and, in a broader sense, by the influence of the conflicting debate on knowledge/training models and curriculum. In conclusion, the curriculum policy debate has no end in sight. It is a discursive field of articulation of demands, negotiations, antagonisms, and disputes of hegemonic meaning that are always precarious and contingent. New projects are at stake, pointing out the possibility of clashing with a given fixation, because of the effects of equivalence.

REFERENCES

ANFOPE Associação Nacional pela Formação dos Profissionais da Educação. Documento Final. XEncontro Nacional. Brasília, DF, 2000. [ Links ]

ANFOPE. Boletim. Ano IV, n. 8, 1998. [ Links ]

ANFOPE. Documento Final. IXEncontro Nacional. Campinas, 1998. [ Links ]

ANFOPE. Documento Final. XIIIEncontro Nacional. Campinas, SP, 2006. [ Links ]

ANFOPE. Documento Final. XIEncontro Nacional. Florianópolis, SC, 2002. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Resolução CNE/CP n. 2, de 1 de julho de2015. Define Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação inicial em nível superior (cursos de licenciatura, Programas e cursos de formação pedagógica para graduados e cursos de segunda licenciatura) e para a formação continuada. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução CNE/CP nº 1, 15 de maio de 2006. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Curso de Graduação em Pedagogia, licenciatura. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de19 de fevereiro de 2002. Institui a duração e a carga horária dos cursos de licenciatura, de graduação plena, de formação de professores da Educação Básica em nível superior. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução CNE/CP, 1, de 18 de fevereiro de 2002. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação de Professores da Educação Básica, em nível superior, curso de licenciatura [ Links ]

BRASIL, Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Superior. Documento Norteador para elaboração das Diretrizes Curriculares para os cursos de formação de professores, GT Licenciaturas, 1999. [ Links ]

CONTRERAS, J. A autonomia dos professores. Tradução de Sandra Trabuco Valenzuela; revisão técnica, apresentação e notas à edição brasileira Selma Garrido Pimenta. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002. [ Links ]

CORAZZA, S. M. Pesquisas pós-críticas em educação no Brasil: esboço de um mapa. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 34, n. 122, p. 283-303, maio/ago. 2004. [ Links ]

DINIZ-PEREIRA, J. E. A formação acadêmico-profissional: compartilhando responsabilidades entre universidades e escolas. In: EGGERT, E. et al. (org.). Trajetórias e processos de ensinar e aprender: didática e formação de professores: livro 1. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2008. [ Links ]

DUQUE-ESTRADA, P. C. (org.). Desconstrução e Ética: Ecos de Jacques Derrida. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. PUC-RIO; São Paulo: Loyola, 2004. [ Links ]

FIORENTINI, D. A Didática e a Prática de Ensino mediadas pela investigação sobre a prática. In: ROMANOWSKI, J. P.; MARTINS, P. L.; JUNQUEIRA, S. R. A. (org.). Conhecimento local e conhecimento universal: pesquisa, didática e ação docente. Curitiba: Champagnat, 2004. [ Links ]

HOWARTH, D. Hegemonia, subjetividad política y democracia radical. In: CRITCHLEY, S.; MARCHART, O. (org.). Laclau: aproximaciones críticas a su obra. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2008. [ Links ]

HOWARTH, D. Aplicando la Teoría del Discurso: el Método de La Articulación. STUDIA POLITICAE, nº 05 - otoño 2005. Publicada por la Facultad de ciencia política y Relaciones Internacionales, de la Universidad Católica de Córdoba, Córdoba, república Argentina. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.bibdigital.uccor.edu.ar/ojs/index.php/Prueba2/article/view/585 >. Acesso em: 14 jun. 2014. [ Links ]

LACLAU, E.; MOUFFE, C. Hegemonia y Estratégia Socialista. Hacia una radicalización de la democracia. Madrid: Siglo XXI, 1987. [ Links ]

LACLAU, E. Nuevas reflexiones sobre la revolución de nuestro tiempo. 2ª ed. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ediciones Nueva Visón, 2000. [ Links ]

LACLAU, E. La razón populista. 6ª reimp. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica , 2011a. [ Links ]

LACLAU, E. Emancipação e diferença. Coordenação geral e revisão técnica geral, Alice Casimiro Lopes e Elizabeth Macedo. Rio de Janeiro: EdUEJ, 2011b. [ Links ]

LACLAU, E. Posfácio. In: MENDONÇA, D. de; RODRIGUES, L. P. (org.). Pós-Estruturalismo e teoria do discurso: em torno de Ernesto Laclau. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS , 2008. [ Links ]

LACLAU, E. Inclusão, exclusão e a construção de identidades. In: AMARAL, Jr., A.; BURITY, J. A. (org.). Inclusão social, identidade e diferença: perspectivas pós-estruturalistas de análise do social. São Paulo: Annablume, 2006. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C. Políticas curriculares: continuidade ou mudança de rumos? Revista Brasileira de Educação. Rio de Janeiro, n. 26, Maio/Jun/Jul/Ago. 2004. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C. Discursos nas políticas de currículo. Currículo sem Fronteiras, Porto Alegre, v. 6, n. 2, p. 33-52, jul/dez. 2006. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C. Currículo, política e cultura. In: SANTOS, L. L. de C. P. et al. (org.).Convergências e tensões no campo da formação e do trabalho docente. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2010- (Didática e prática de ensino). [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C. Teorias Pós-Críticas, Política e Currículo. Educação, Sociedade e Culturas. Cidade n. 39, 2013, 7-23. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C; MACEDO. Teorias de currículo. São Paulo: Cortez , 2011a. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C ; MACEDO. Contribuições de Stephen Ball para o estudo de política de currículo. In: BALL, Stephen J.; MAINARDES, Jefferson. (org.). Políticas educacionais: questões e dilemas. São Paulo: Cortez , 2011b. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C; MACEDO; MATHEUS, D. dos S. Sentidos de Qualidade na Política de Currículo. Educação & Realidade, Porto alegre, v. 39, n. 2, p. 337-357, abr./jun. 2014. [ Links ]

LÜDKE, M. Universidade, escola de educação básica e o problema do estágio na formação de professores. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa sobre Formação Docente. Belo Horizonte, v. 01, n. 01, p. 95-108, ago/dez, 2009. [ Links ]

MENDONÇA, D. A teoria da hegemonia de Ernesto Laclau e a análise política brasileira. Ciências Sociais Unisinos, set.dez, ano/v. 43, n. 3. Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, 2007. [ Links ]

MENDONÇA, D. Como olhar “o político” a partir da teoria do discurso. Revista Brasileira de Ciência política, nº 1, p. 153-169, Brasília, janeiro-junho de2009. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, A. Formação de professores e profissão docente. In: NÓVOA, A. Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa, Portugal: Publicações Dom Quixote, 1992. [ Links ]

PÉREZ-GÓMEZ, A. O pensamento prático do professor: a formação do professor como profissional reflexivo. In: NÓVOA, A. (org.). Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa, Portugal: Publicações Dom Quixote , 1992. [ Links ]

PIMENTA, S. G. O estágio na formação de professores: unidade teoria e prática? 10ª ed. São Paulo: Cortez , 2011. [ Links ]

PIMENTA, S. G.; LIMA, M. do S. L. Estágio e Docência. 3ª ed.São Paulo: Cortez , 2008. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. A pedagogia no Brasil: história e teoria. 2ª ed. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados, 2012. [ Links ]

SCHÖN, D. Formar professores como profissionais reflexivos. In: NÓVOA, A. Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa, Portugal: Publicações Dom Quixote, 1992. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. T. da. O currículo como fetiche: a poética e a política do texto curricular. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica , 2010. [ Links ]

SILVESTRE, M. A. Modelos de formação e estágios curriculares. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa sobre formação docente. v. 03, n. 05 ago.dez/2011. Disponível em: <Disponível em: htpp://www.formacaodocente.autenticaeditora.com.br/artigo/exibir/10/36/8 >. Acesso em: 14 jun. 2014. [ Links ]

STENHOUSE, L. An introduction to curriculum research and development. Londres: Heineman, 1975. [ Links ]

VENTURIM, S. O Estágio Supervisionado em Educação Física como contexto produtor de ações colaborativas entre a formação inicial e a formação continuada de professores. 2009. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.anpae.org.br/congressos_artigos/simposio2009/326.pdf >. Acesso em: 14 jun. 2014. [ Links ]

VEIGA-NETO, A. Cultura, culturas e educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação. Rio de Janeiro, Maio/Jun/Jul/Ago, n. 23, 2003. [ Links ]

WITTGENSTEIN, L. Investigações filosóficas. Tradução de Marcos G. Montagnoli. Revisão da tradução e apresentação Emmanuel Carneiro Leão. 8ª ed. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes; Bragança Paulista, SP: Editora Universitária São Francisco, 2013. [ Links ]

1Documents of educational entities: ANPED, ANPAE, ANFOPE, CEDES, and FORUMDIR. A speech by educational entities on the Undergraduate Course in Pedagogy, 2006; ANFOPE. Final Document XIII National Meeting. Campinas, SP, 2006; ANFOPE, ANPED, CEDES. Document by the entities on the Preliminary Draft of a CNE Resolution on the School of Pedagogy, 2005; ANFOPE. Final Document of the XII National Meeting. Brasília, DF, 2004; ANFOPE, ANPED, CEDES. Document sent to the CNE. National Curriculum Guidelines for courses in pedagogy, 2004; FORGRAD. Teacher training guidelines: concepts and implementation (preliminary version). Text based on the João Pessoa (PB) Workshop, performed on September 16-17, 2002; Proposal for the National Curriculum Guidelines for undergraduate courses in pedagogy, referred by: Commission of Pedagogy Teaching Experts and Commission of Teacher Training Experts, Brasília, 2002; ANFOPE. Final Document of the XI National Meeting. Florianópolis - SC, 2002; Joint statement of ANPED, ANFOPE, FORUMDIR, CEDES and the National Forum on the Defense of Teacher Training, at a consultation meeting with the academic department, within the special program “National mobilization for a new basic education,” established by the CNE, Brasília/ DF, 07/11/2001; ANPED, ANFOPE, Forum, FORUMDIR, Forum of the Deans of Undergraduate courses of Brazilian University, National Forum of Deans, UNDIME, CONSED, CNTE. Contributions of entities to support a discussion on the National Public Hearing/CNE on Teacher Training for Basic Education in Higher Education Courses, Brasília, April 23rd, 2004; ANPED, ANFOPE, ANPAE, FORUMDIR, Forum in Defense of Teacher Training. Contributions of entities to support a discussion at a National Public Hearing/CNE on Teacher Training for Basic Education in Higher Education Courses, RJ, April 3rd, 2001; ANFOPE. Final Document of the X National Meeting. Brasília, DF, 2000; Proposal for National Curriculum Guidelines for Courses in Pedagogy: Commission of Experts in Pedagogy Teaching, May 6th, 1999; Guiding Document for devising National Curriculum Guidelines for Teacher Training Courses: GT Teaching Degrees, composed of SESu/MEC, 1999; ANFOPE/ FORUMDIR, Letter of Recife, November 5th,1999; ANFOPE. Final Document of the IX National Meeting. Campinas, 1998; ANFOPE. Final Document VII National Meeting. Belo Horizonte, 1996.

2The Common National Core (BCN) articulates different demands in the debate analyzed: the pedagogy course identity - specialist vs generalist, teacher vs specialist (concept of teacher/extinction of qualifications); teaching as a foundation of training and the professional identity of every educator/unity in training between teaching degree holders and uncertified instructors; opposition to minimum curricula; professionalization of professional education/professionalization of teaching; global policy on training education professionals; instrument of struggle against the degradation of the profession; training the professor and specialist within the educator; the BCN is the only one of all training courses/pedagogical projects common to the training courses for education practitioners; unitary training of the educator/teaching degree and BA; curriculum organized by educational principles and guidelines; a guideline that must permeate the curricula of training/conception of education/educator; project of transformation of society/social commitment of the educator/historical struggles; political and social dimensions of education and the link between the form of organization of school in the capitalist society/class perspective.

3ANFOPE. Final Document of the XI National Meeting, 2002; FORGRAD - Forum of Deans of the Undergraduate courses of Brazilian Universities, João Pessoa/PB Workshop, 2002; Proposal for National Curriculum Guidelines for the Undergraduate Course in Pedagogy. Commission of Experts in Teaching Pedagogy and Commission of Experts in Teacher Training. Brasília, 2002; ANPED, ANFOPE, FORUMDIR, CEDES, National Forum in Defense of Teacher Training. Collective statement of entities in consultation with the education sector. Brasília, 2001; Guiding Document of Curriculum Guidelines. GT Teaching Degrees, 1999; Proposal for National Curriculum Guidelines for the undergraduate course in pedagogy. Commission of Experts in Pedagogy Teaching. Brasília, 1999; ANFOPE. Final Document of the IX National Meeting. Campinas, 1998.

Received: December 22, 2016; Accepted: September 01, 2017

texto em

texto em