Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. Rev. vol.34 Belo Horizonte 2018 Epub 20-Set-2018

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698200391

Article

MEDIA EDUCATION, EDUCOMMUNICATION AND TEACHER TRAINING: PARAMETERS OF THE LAST 20 YEARS OF RESEARCH ON SCIELO AND SCOPUS DATABASES

1State University of Northern Rio de Janeiro, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, Brazil.

The goal of this study is to investigate the researches that explore the relationship between Educommunication and Teacher Training, Media Education and Teacher Training, on a national and international scale. The search for documents was made on SciELO and Scopus databases, from the period between 1997-2017, with the specific purposes of mapping the data through graphs and refining the results for a profitable analysis of the publications. From the results obtained, it was possible to confirm the lack of studies that contribute with reflections for a teacher training in the scope of a digital culture. Despite interesting initiatives in the study of the media, there is a prevalence, in the courses, of notions directed to the use of technologies in teaching, with a disciplinary emphasis. Critical and creative perspectives of reading and production in media are poorly explored. Thus, Media Education is defended as a fundamental formative field for the exercise of active citizenship.

Keywords: Media Education; Educommunication; Teacher training; Digital culture

O trabalho tem como objetivo investigar as pesquisas que exploram a relação entre Educomunicação e Formação docente, Educação midiática e Formação docente, nacional e internacionalmente. As buscas foram realizadas nas bases SciELO e Scopus, do período de 1997 a 2017, tendo as finalidades específicas de mapear os dados, por meio de gráficos, além de refinar os resultados para uma análise profícua das publicações. A partir dos resultados, foi possível confirmar a escassez de trabalhos nacionais e internacionais que contribuam com reflexões para uma formação docente no âmbito de uma cultura digital. Apesar de iniciativas interessantes de estudo das mídias, há a prevalência, nos cursos, de noções direcionadas ao uso das tecnologias no ensino, com ênfase disciplinar. As perspectivas críticas e criativas de leitura e produção em mídias são pouco exploradas. Assim, defende-se a Midiaeducação como um âmbito formativo fundamental para o exercício de uma cidadania ativa.

Palavras chave: Educação midiática; Educomunicação; Formação docente; Cultura digital

INTRODUCTION

Although it seems consensual the understanding that the cultural perceptions of the society in its digital phase are organized more and more from the media and that they fulfill the function of mediators between the social actors and the culture, (re)configuring the possibilities of collective interactions, the urgent need for education to emphasize the importance of sociocultural transformations promoted by technologies is not discarded.

The processes engendered by communicational technological updates, especially digital ones, integrate (re)configurations that comprise not only technical aspects, but social and cultural contexts that structure the discursive formations of the subjects. Some of these changes have repercussions in the ways of interaction, access to information, production, reception and circulation of content, extending the forms of construction of the subject and relationship with the other, with technical devices. Conditions that request another look at the communicational processes and their interference in the socio-cultural, symbolic dynamics.

Understanding media as a process of mediation calls for recognizing the tension among technological, industrial and social (SILVERSTONE, 2005). With the assumption that the educational principles reflect the society that one wishes to construct and considering that the demand of the society is not always the same of the education, one cannot ignore the role of the media in the formation of teachers. It is also a structure for everyday life driven by information, even with fragmented and unequal access. This mode of living determines the interactions between the individual and information, the construction of knowledge.

Educational formations in different modalities, as well as social institutions, are marked by historical, cultural and social scenarios in which the communicational processes and their systems are an important factor, which makes it insufficient to consider only the formal cells that make up the educational framework: teacher , student, didactic materials, training, teaching-learning, etc., without analyzing the context that goes beyond the school.

In this sense, the media education1 turns to reflections of teaching and analysis on, to and with the media and composes theoretical framework that takes the communicative actions in diverse scopes in the attempt to consider this process that is so fundamental in the life of the individual and to stimulate democratic practices in which citizenship is exercised. Among the various aspects and impasses about their actions, there is a consensus among experts (Marques-Barbero, 2000, 2002, BELLONI, BÉVORT, 2009, FANTIN and RIVOLTELLA, 2010; FANTIN, 2012) on the need to give attention to education and communication.

In the intersection between Education and Communication, these researchers advocate that in the teacher education the communicative process (media, technologies and languages) is studied, practiced and improved by the prism of an emancipating relationship with the media. What requires education for, about the media, with the media and through the media, from a critical (object of study), instrumental and expressive-productive approach.

With this, there is the interest in knowing what research has been developed in the areas of media education, Educommunication and Teacher training at the national and international level, for a parameter of what has been developed. As a hypothesis, it is argued that the relatively recent thematic is little explored, in spite of the fundamental importance of inserting the processes driven by the digital culture in the scientific and educational discussions. What would make it possible to understand media, especially in initial teacher training (main phase for other transformations), as important elements for the production, reproduction and transmission of culture is that the stimulation of its critical and creative appropriation is consistent with the effective exercise of citizenship.

The paper presents the general objective of investigating the research that explores the relationship among Educommunication and Teacher Training, Media Education and Teacher Training, nationally and internationally in the last twenty (20) years - 1997 to 2017, on the SciELO and Scopus databases. Having the specific purposes of mapping, through graphs, the data generated by the search broken down by year of publication, type of document, source, authors, institution, country and area of knowledge. In addition to refining the results for a fruitful analysis of the publications and their contributions to the field.

The methodology, regarding the objectives, is defined by the descriptive research, using as technical procedure the bibliographic research (literature review). Due to the bibliometric survey, developed from databases, work is also recognized as a “state-of-the-art” or “state-of-the-knowledge” research for discussing a particular academic production in different fields of knowledge, finding out what forms, aspects and dimensions the work is highlighted (FERREIRA, 2002).

The study was supported by contributions from researchers Soares (2002, 2014); Martín-Barbero (2000, 2002); Belloni and Bévort (2009); Fantin (2012), among others, presented in parts that comprise Media education in historical perspective and its aspects summarized in the Moral, Cultural and Mediatic protocols, with emphasis on the Educommunication approach. The teacher training was also approached by the relationship with the communicative and technological processes. The analysis of bibliometrics data was increased. This survey contributes substantially to the knowledge of the research developed in the areas in the last 20 years in national and international spheres, besides contributing with the understanding that education needs to consider communication as a strategic and necessary means for the production and circulation of information and knowledge and socio-cultural constructions, including teaching-learning.

THE MEDIA EDUCATION IN HISTORICAL AND CONCEPTUAL PERSPECTIVES

The theme of Education about and with the media has been recurring in some congresses and official documents that assume the inevitable necessity of approach between the areas: Education and Communication. Notably technical advances and social and cultural changes drive this dialectic towards an inter/transdisciplinary vision that addresses the challenges of digital culture.

The expression Education for medias or Midia education emerged in 1960 in international organizations, particularly UNESCO, referring to two aspects: the capacity of mass media as a means of distance education and the concern of teachers and intellectuals with media influences, the risks of ideological manipulation, politics, consumption and the need for critical approaches (BÉVORT and BELLONI, 2009).

In 1973, UNESCO presented a first definition that explained the double dimension of Media Education, emphasizing the media as an object of study of critical reading and intervention action to alert and minimize the effects of the media, and as a pedagogical tool of educational function.

UNESCO’s attempt to bring together the areas of Communication and Education in the sphere of public policies began in the debate on the development of Latin America, rather than in the specific reflection of the influence of the media in society - a relevant point to think about the importance of this agenda for the reach of a more citizen society. As a result, the organization directed its efforts to promote a meeting in Mexico in December of 1979, receiving the Ministers of Education and Planning from Latin countries to investigate the fundamental problems of education in the context of the overall development of the region. The result of this event was the Major Project on Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (SOARES, 2014b).

Of wider international scope, the Grünwald Declaration, following a meeting in West Germany in 1982, was another significant step towards the formation of this field of educational action. The document, organized by representatives of 19 countries, presented the common idea on the importance of the media and the duty of education systems to help citizens understand these phenomena. The term “media education” was approved in it.

The Paris Agenda (2007) revealed, with the balance of Grünwald’s 25 years, that Midiaeducation is not included in school, nor has it become a priority in society, despite interesting initiatives by militant educators. It reaffirms the conviction that media education is part of training for citizenship and that it is indispensable for the constitution of a plural, inclusive and participative society (BÉVORT and BELLONI, 2009).

According to Soares (2014b), it was found that the few educators for Latin American media, belonging to ONGs or Research Centers, now integrated into the Master Project, abandoned both the manipulative and ideological theories (strands explained in subsection a follow). For these decision-makers:

They were no longer served by systemic scientism, much less exaggerated moralism. They sought, in another direction, the formulation of a synthesis that would give coherent support to an effective struggle for the democratization of communication policies in the continent, based on the proposal to implement a new world order of information and communication (under the acronym Nomic). Strategic path was, therefore, the bridge built between the references on the planning of participatory action in development projects {BORDENAVE; Carvalho, 1979}, on the one hand, and the practices of negotiation of meanings recognized by the theory of cultural mediations {MARTÍN-BARBERO, 2000} on the other (SOARES, 2014b, 21).

This has alienated a significant group of Latin American activists from the traditional view of the media phenomenon (denouncing acts of violence, sensual appeal or manipulation of information). Challenge put on a quest for another sense of making education for communication.

An example was the Communication Critical Reading Project of the Brazilian Christian Communication Union (UCBC) in 1980 and 1990. The methodology adopted allowed people and groups (leaders of the popular movement and teachers) to discover the “nature of their relations with the media, from their social place and their own interests (dialectical perspective, as opposed to a positivist and cognitivist perspective), to which was summoned the invitation to take over the languages and the production processes” (SOARES, 2014b, p.21). Thus the alternative/popular communication was constituted in 1970/1980 in the continent.

In another important action, at the end of the 90’s (May, 1998), the First International Congress on Communication and Education took place in São Paulo. Effective opportunity for conceptual exchanges between the specialists in “communication education” and “educators for the media”, as well as classroom teachers. There were 1.500 participants, 170 keynote speakers from 30 countries.

The impact was so relevant that the First International Congress was the object of academic studies in Brazil and abroad. The conclusion reached by the Indian researcher, Joseph S. Devadoss, in his doctoral thesis at the Università Pontificia Salesiana (Rome), was that the meeting represents one of the five most important world events on media education in the 1990s2 , guaranteeing the circulation of exchanged ideas from both Europe and Latin America and highlighting Buckingham’s proposal to extinguish the protectionist approach towards children by valuing studies accompanied by practices.

Another idea that prevailed was the one of Roberto Ferguson that defends the Media Education under the approach of a methodology that makes possible the collective and solidary construction of knowledge in function of the critical analysis of the media. Professor Ismar Soares was also quoted by the defense that concerns should be centered on the communicative process and not specifically on the analysis of the media themselves. In short, the debates contributed to the fact that Media Education ceased to be regarded as a merely educational problem in order to become a cultural issue. Another novelty was the presentation of a concept still unknown: Educommunication (SOARES, 2014b).

Some approaches to Media Education

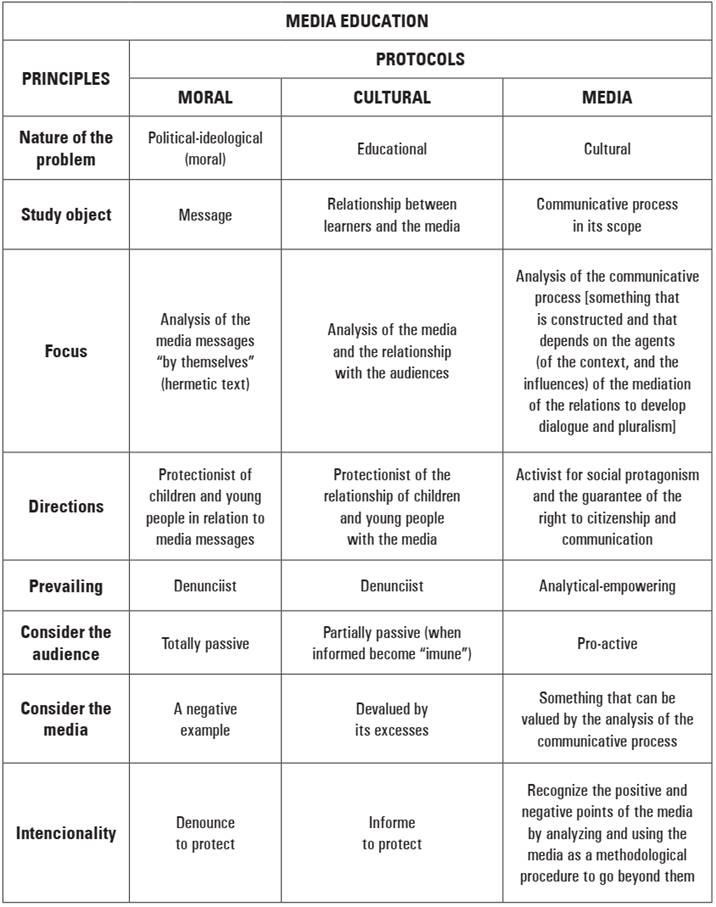

The area of intervention between Education and Communication makes possible different practices, although some manuals indicate a unique model of practicing Media Education. In analyzing the established programs historically, Soares (2014b) concludes that there are three basic protocols, among other possible, comprised by the set of concepts and norms that guarantee the identity of actions, their coherence and public acceptance: moral, cultural and the mediatic (or educommunicative)” (SOARES, 2014b, p. 17).

The Moral Protocol, still hegemonic and the oldest (1930), was developed by religious of different denominations (Jews, Protestants, Catholics) who maintain educational activities, some systematic, against the dangers represented by the cinematographic productions and, later, the media that invaded the homes, from 1950 on. The understanding that the right of children and young people to have a quality media production cannot be suppressed by freedom of expression comes from this orientation. Therefore the need to adopt rules of conduct to prevent the excesses of the media, such as the indicative classification of the shows, requiring productions based on social responsibility. On a more extreme level, some advocate a ban on advertisements targeting children.

The Cultural Protocol recognizes that communication and the media are integral parts of the culture, so they need to be known and studied. By accessing information about the media, children and young people can be immune to their excesses, especially those who exert psychological effects on their training. The focus of this perspective is the relation of students with the media and technologies. Thus the activities that follow this protocol are titled as: Educación para lós Medios, Spain, Education for the Medias, Portugal, and Media Education, Brazil.

The Media Protocol is delineated by a somewhat systematized stream, although it has been established since 1980 in Latin America. From the social movements, this principle strives for the universalization of the right to communication to guarantee to all social subjects, through education, “access to the word”, denied to the poorest and most excluded and curtailed by hegemonic media conglomerates. The focus of this strand is not in the medium itself, but in the communicative process as a whole, concerned with strengthening the capacity of expression of children and young people. For this, all forms of communication (interpersonal, family, school, mass media, among others) are objects of analysis. The Theory of Cultural Mediation by Martín-Barbero is responsible for the use of media expression. It is based on the fact that everyone is inserted and involved in different communicative ecosystems3, transitioning into the functions of transmitters and receivers. Soares (2014b) explains that:

At school, what is proposed is the revision of communicative dysfunctions arising from power relations, seeking democratic and participative forms of school management, with the involvement of the new generations. What distinguishes this protocol is its intentionality: it values the media and includes its analysis and use as a methodological procedure, but goes beyond it in its purposes and goals. It operates by projects, valuing all forms of expression, especially the artistic one, aiming to increase the communicative potential of the educational community and each of its members. In this case, teachers and students are also apprentices and educommunicators (SOARES, 2014b, p. 18).

In order to contribute to an understanding of these different approaches, a comparative table was created (Box 1), based on the explanations of Soares (2014b) and some reflections of Zanchetta (2007).

In Latin America, in the 1970s, intellectuals and educators expressed a strong reaction to the possible influence of the media, especially television on children and young people. The reaction had two theoretical opposites. By “political-ideological theory”, the intellectuals were concerned with studies of the economic and political structures that underpinned forms of communication (criticism of corporations and governments favoring information vehicles). They denounced the explicit dependence of the Southern Hemisphere on the Northern Hemisphere on the production and distribution of cultural and communicational goods. This pole was sustained by the “Marxist theory of the imposition of the ideology of the dominant classes (holder of the media) on the dominated classes (consumer of the media)” (SOARES, 2014b, p. 19).

The Media Education activists adopted the “manipulative theory”, under the precepts of liberal American (Laswell and Scharamm) researchers. For them, the effectiveness of communicative action was guaranteed by the theory of effects, that is, by the duality and prevalence of the sender on the receiver (powerful media commanded the imagery of a passive audience). In this sense, the children learned from the media that needed to be watched. The object of study in classroom programs was the messages of the media and their impacts (stereotypes), leaving behind the processes of production and the structure of power aimed at in the chain of ideological perspective (SOARES, 2014b).

Both theories, in diferente ways, were denuncist and did not take into account the responsiveness and response of the public, consumer. The pessimistic view of the media precluded any dialogue between communication (uncompromising and promiscuous space for leisure and entertainment) and education (formal and serious training space), to the point of generating resistance from educational systems to Media Education programs. It was in this scenario that UNESCO decided to invest with training proposals from a third possibility: cultural development of the population of the continent (SOARES, 2014b), as previously mentioned by the actions and events supported by the sector.

EDUCOMMUNICATION: AN EXPANDING AREA

In the 1990s, also driven by reception studies with a focus on communication processes (relationship between producers, the production process and the reception of messages, for example), the area of Educommunication was reaffirmed by researchers. In addition to a few events in Latin America, the Forum on Media and Education, promoted in Brazil - November 1999, consolidated the definition of parameters that approximate the areas, according to their conclusions:

We recognize the interrelation between Communication and Education as a new field of social intervention and professional action, considering that information is a fundamental factor for Education. Technological development has created new fields of action and areas of convergence of knowledge (BRASIL, 2000, p. 25).

Between 1997 and 1998, ECA/USP’s Communication and Education Center (NCE), under the coordination of researcher professor Ismar de Oliveira Soares, carried out one of the most important researches under the title “Inter-relations between communication and education in Latin American culture”, with the participation of 178 specialists (cultural producers, art educators, technologists, teachers, researchers and communication and education professionals) from 12 Latin American countries, by questionnaire.

The confirmed hypotheses of the research found that Educommunication is an area of social intervention in consolidation, not understood only as a discipline for school curricula, but a transverse discursive paradigm instituted by transdisciplinary concepts with other analytical categories. The second confirmation was that the field of relational nature “structures itself in a mediatic, transdisciplinary and interdiscursive process, {polyphonic} being experienced in the practice of social actors through concrete areas of social intervention” (SOARES, s.n.t.). The third, delimited four concrete areas of professional activity that are not exclusive and unique.

The area of information literacy is related to technological innovations in the daily life of people, with the use of information technologies in education (face-to-face or distance learning). However, it seeks to overcome the instrumentalist approach of technologies, recognizing the social influences of the media, promoting debates about mediations and the restricted appropriation of the educational community as a performance tool only for teachers. In this way, it considers that the displacement of a model of linear communication to one in networks (distributed communication) destabilizes the traditional forms of education:

Learning takes place insofar as the individual feels touched, involved, connected. In this way, the environment mediated by technologies can help to produce meanings, becoming mediation. It is the sense that causes learning, not technology, and that is why the field is for communication or education (SOARES, 2002, p. 20).

“Education for communication” or “media literacy” is based on reception studies focusing on the elements of communication processes (relationship between producers, production process and example) and for the pedagogical field - autonomous and critical receptor training programs, involving universities, popular education centers and non-governmental organizations. Soares (2002) reports that a study on the programs developed in the continent (1971-2001) points to three trends (already addressed): the “moralistic side” - articulates against the negative impact of the media; the “culturalist strand” - seeks to instruct learners for a “proper” reading of media messages; and the “dialectical side” - part of the study of the process of communication, of relations between recipients, producers and the media, considering the social, political and cultural place in which they are.

This area of study can be defined by the ability to access, analyze, evaluate and communicate messages in a variety of ways, which broadens the dimension of programs by inserting the perspective of the use of information resources, as well as aiming to implement regular, integrated actions to curricula (when in school), which allow students to understand how the communication and the commitments of the media system with society are processed. For the Ministry of Education (2010, p.16) the way to promote communication education is in the collective media production itself at the school with its self-analysis.

The area of communicative management includes the planning and execution of educational communication policies, seeking to unite communicative actions to expand the spaces of expression. Through this management, Educommunication intends to effect “technological mediation in education” and “education for communication”, integrated into the daily school routine to expand the possibilities of communicative actions of teachers, students, the school community.

The fourth area of epistemological reflection is in the field of academia and understands the interrelation between communication and education as an emerging cultural phenomenon. In this area, it is considered that academic research will guarantee unity of Educommunication practices, whether developed in projects that seek to understand and legitimize the field or research programs on each aspect of the intersection (SOARES, s.nt.).

Among the definitions to designate Educommunication, we mention “all communicative action in the educational space, carried out with the aim of producing and developing communicative ecosystems” (SOARES, s.n.t.). In a detailed way, this corresponds to the set of actions that requires planning, implementation and evaluation of processes, programs and products aimed at creating and strengthening communicative ecosystems in presential and virtual educational spaces to improve communication in educational actions, including the use of resources in the learning process (SOARES, 2002). For this,

{...} supposes a theory of communicative action that privileges the concept of dialogical communication; an ethics of social responsibility for cultural producers; an active and creative reception from audiences; a policy of using information resources according to the interests of the poles involved in the communication process (producers, mediating institutions and consumers of information), which culminates in the expansion of the spaces of expression (SOARES, 2002, p. 25).

From the focus on communicative management, the concept presents itself as a paradigm in the communication and education interface, a political and pedagogical movement that aspires to the development of solidarity in interactions. It is a broad field that goes beyond a “new” methodological, didactic proposal. The management of communication brings to the communicative act the idea of a process in which the agent is responsible for the activities, the mediation of relations to develop dialogue and pluralism (SOARES, 2014a).

MEC (BRASIL, 2010) recognizes Educommunication as a field that happens through joint actions in different areas and that has the dimension of a movement that defends: “{...} to enable the knowledge about the media society, through the exercise of the use of its resources, always participatory and integrating the interests of community life {by the democratic management of communication}” (BRASIL, 2010, p. 16).

The Educommunication perspective summons the cultural issue embedded in the communication process, reallocating the discussion agenda to more complex aspects than merely the messages, the means. With collaboratively organized projects, Educommunication defends the importance of reviewing the theoretical and practical standards by which communication takes place.

It seeks, in this way, social transformations that prioritize, from the literacy process, the exercise of expression, making such a solidarity practice a learning factor that broadens the number of social and political subjects concerned with the practical recognition in the daily life of social life, universal right to expression and communication (SOARES, 2014b, p. 24).

Thus, the analysis of the interrelation between education and communication may be one way. According to Ismar Soares (2014b), some articles argue that “technologies must be placed at the service of education” (SOARES, 2014b, p.28). Contrary to this proposal, the researcher suggests that education retakes the communicative ecosystem dominated by the closed and excluding model of the information society. In order to do so, it bases the “inversion of route”: “{...} besides placing the apparatuses in the service of education, it becomes imperative that education be placed in the service of the understanding of what technologies represent for society itself. This is, precisely, the ‘action’ (Galimberti) taken by Educommunication” (SOARES, 2014b, p. 28).

APPROXIMATION OF TEACHER FORMATION AND TECHNOLOGICAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PROCESSES

With a language, a possibility of information arises. Knowledge and skills can be shared. Non-formal education is transmitted from adults to young people through graphic, gestural and then oral language. With the text of the writing (there are about 4,000 BC - cuneiform writing. GIOVANNINI, 1987), has the task of creating an information frame for the formation of different spaces, depending on the local situation. Interpersonal communication is to be carried out at a distance and through time. Registration allows information to be perpetuated (BRASIL, 2010).

The portable media, book, inaugurates another context in the transmission of knowledge, in which one does not depend so much on orality (a “flawed” feature of oblivion). The press also makes possible basic education with the availability of copies of books (massive dissemination of content) and is an important instrument for the revolutions of science, through newspapers, magazines, mass communications, and religion, from the Bible, first book printed in 1456 (GIOVANNINI, 1987).

It is noted that communication has become even more intense in the information society (or post-industrial). Thus, in the educational context of the twentieth century, information has no longer had exclusive sources such as books, newspapers, magazines and the teacher in the classroom to be disseminated also by the electronic media - radio, TV, internet. Mediations have also been updated and leveraged with the internet for the possibilities of communication and interconnection. In addition to access and excessive information, the cloud inaugurated another stage, until then limited to the small portion of the population: communication production (BRASIL, 2010).

In this regard, MEC, in the section Communication and the use of media in Cadernos Pedagógicos of the Program Mais Educação (BRASIL, 2010), highlights the influence of the media in the production of meanings and in social representations. It also highlights that the internet has made the process more complex. However, the digital environment (the environment and devices) has opened spaces for the exercise of the right to communicate, that is, “the possibility for each {individuals, groups, social sectors, countries} to express their ideas and disseminate information they deem relevant, with real chances of being heard” (BRASIL, 2010, p. 9).

With the characteristics of mobility, portability and connectivity, digital media allowed greater autonomy for media consumption and interactivity allowed other types and practices of consumption. Therefore, if before with traditional media the issue imposed on education was to instruct to avoid passive consumption, now the challenge is to teach not only responsible consumption, but responsible production (RIVOLTELLA e FANTIN, 2010).

In this scenario, the school, in the context of intense influence of the media, had its role questioned. For the anthropologist Martín-Barbero (2002),

the school is no longer the only place to legitimize knowledge, because there is a multiplicity of knowledges that circulate through other channels and do not ask the school’s permission to expand socially. This diversification and diffusion of knowledge outside the school is one of the strongest challenges that the world of communication places on the educational system (MARTÍN-BARBERO, 2002, n.p., translated by the authors).

The school institution seems to maintain a traditional posture of a vertical relationship between teacher-student and closed to the reality of the student, the community, and society. Would the insertion of technologies without the change of this model solve the problem? Martín-Barbero (2000)argues that this is not the way. For the researcher, the inclusion of the means and technologies in this school model raises the more obstacles for the school if it inserts itself into the “complex and confusing” reality of the society:

By taking as a starting point the changes that are necessary to the school so that it can interact with parents and not simply for the use of the media, I am facing a misunderstanding that the school system does not seem interested in undoing: the obstinate belief that the problems of the school can be solved without transforming its communicative-pedagogical model, that is, with a simple aid of a technological type. And that’s a self-deception. While remaining upright in the teaching relationship and sequential in the pedagogical model, there will be no technology capable of taking the school out of the autism in which it lives. It is therefore essential to start from the problems of communication before talking about the means (MARTÍN-BARBERO, 2000, p. 52-53).

When considering some of these changes, the Ministry of Education (2010) emphasizes the need for the school to take back its social function through also a critical reading of the media. “The recovery of the role of the school is related to its capacity to become a privileged space to guarantee the new generations the knowledge and the indispensable skills, so that they communicate with autonomy and authenticity” (BRASIL, 2010, p.15).

It is from the perspective of Educommunication, as a new area of study, that the organ indicates the way to “recognize the breadth of media influence” and “strengthen and update the role of the school as an institutional mediator” (BRASIL, 2010, pp. 12, 13), and is also fundamental for stimulating more knowledgeable audiences of mediation processes and more reflective of their actions.

In this sense, the teacher has a fundamental role for the “critical formation” of the student in a context in which the forms of communication and their mediating functions are more present in their daily life, because students have access to tools and channels for production and content placement. For Soares (2014a), although scholars of the competencies of the teaching profession contribute with some developments, they are limited to didactic-pedagogical, even when they value socioemotional competences.

For the teacher training, it is necessary to address the political-technological perspective of the communicative ecosystem that limits and conditions the ways of being in the world. “In this sense, the new teacher, in order to attend to the new student, would need to add to the pedagogical competences and to the valuation of the subjectivity of the students a vision of the world that will fulfill their traditional formation” (SOARES, 2014a, 28), and develop skills that contribute not only to the use of technologies in the classroom and in their daily activities, but also to think about the context and what socio-cultural effects that this broad access to new forms of movement promote in their intra and extracurricular routines.

In terms of teacher training, a research carried out in 2010 by Professor Mônica Fantin (2012a), demarcates the use of ICT in the classroom only as a resource, without recognizing its cultural perspective. In this way, she considers:

{...} within this positive view of ICTs, teachers still regard technology as just a “resource” that can facilitate their work, not culture. When they understand it only in its dimension of resource that can or can not be used in the classroom, teachers do not see the media and technologies as sociocultural objects. With this, the media and ICTs are not perceived as a culture that mediates relationships, which is part of our life and that determines to some extent the production and the socialization of knowledge. This is an interesting fact that may point to an indication of work for the formation, since we hope that the point of arrival is a new representation of technology as a culture and space of collaboration (FANTIN, 2012a, p. 106).

The teaching performance, at least in legal terms, recognizes the importance of technologies and media. The curricular parameters for elementary school point to the need of approximation with the communication system. The reform of high school plans that almost a third of the content of the curricula to be elaborated consider the technologies and the means of communication present in the society and the education. However, Soares (2002) denounces:

Despite the goodwill of the law, there remains the difficulty arising from the lack of preparation of the teachers, taking into account that the Faculties of Education still do not know the subject, which causes the educational planners to disregard the subject. Hence the realization that the projects in vogue remain, most often as extra-curricular activities or depend on the isolated action of activists, usually within the framework of non-governmental organizations (SOARES, 2002, p. 24).

There is a mismatch among university and school, public policies of inclusion of ICTs in schools and policies of teacher training, according to Fantin (2012b), who argues:

{...} it is evident that the curricular insertion of the education media in the initial formation does not account for the necessary learning regarding the uses of the media and technologies in formative contexts. However, its absence further aggravates this situation and with this, the teacher seeks to fill this gap in different ways: personal effort with family and friends, extension courses, specialization courses and continuing or ongoing training in the places of performance, as demonstrated the research of Fantin and Rivoltella (2010a). However, {...} the use of consolidated technologies in the personal context contrasts with the little use in the professional scope.

These considerations show that the curricular insertion of the education media in Brazil still leaves something to be desired, and the fact that it does not exist “officially”, either as a compulsory subject or as a cross-cutting theme, makes it, for the most part, only seen as a pedagogical resource and not as an object of study articulated with other areas of knowledge. This not only reflects a certain mismatch in relation to the international context, but also reveals the tensions and contradictions between the current curricular content and the emerging issues of contemporary culture. (FANTIN, 2012b, p.446).

The researcher in Communication and Education, Juvenal Zanchetta (2007), supports this finding when confirming that in the formation of teacher the preparation to handle the media is still an “essayistic object”. Among the pedagogical tendencies in the degree courses, there is no defined space to deal with the media. In addition, few studies address the insertion of media in school, even though there are significant incursions.

In this sense, the importance of a technology approach in initial teacher education based on Educommunication is reaffirmed. Its foundations can increase the critical capacity of the teacher, something that can also be passed on to the students, to understand the importance and influence of information and communication technologies, paying attention not only to the character of an instrument that can facilitate the educational process, such as the cultural, social, economic, “power-object” perspective that needs to be known.

Attending to the educational process, the essence of the teaching-learning act is in the dialogue, communication. Thus, it is important to rethink education in the aspect of managing the communication processes, proper to the action of teaching and learning. This attention does not only include, in teaching pedagogical practices, an exchange of one-all communicative model for all, but the understanding of the process (its languages and technologies) that takes place in the communicative ecosystem.

In this way, the initial teacher training must provide conditions for the future teacher to be a mediator of contents and also a “developer of questionings” (SOARES, 2014a). The use of technologies requires the teacher to learn to dialogue with his students in order to be able to mediate a deeper exchange of arguments and procedures directed to the development of critical attitudes.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The methodological course was based, in relation to the objectives, in the descriptive research because it aims at approaching the relationships between Educommunication and Teacher training, Media education and Teacher training, based on theories and, mainly, to describe the works that correlate these themes with research in the SciELO and Scopus databases. “Research of this type has as main objective the description of the characteristics of a certain population or phenomenon or the establishment of relations between variables” (GIL, 2008, p.28).

Thus, what was developed in this study was based on the technical procedure that is classified as a bibliographical research, based on already published materials (books, scientific articles, digital materials). The research was divided in two phases: 1st stage - literature review - that was configured by the brief theoretical approach to delineate, in historical and conceptual terms, the field of Media Education, as well as to present some perspectives in the areas of Educommunication and Teacher Formation; and 2nd stage - bibliometric survey - moment that comprised the research in the SciELO and Scopus databases to verify the studies carried out on the researched topics.

In regard to this second moment, and considering the general objective of investigating the researches that explore the relationship between Educommunication and Teacher Formation, Media Education and Teacher Formation, nationally and internationally in the last twenty (20) years, in the SciELO and Scopus databases, the research is denominated as “state of the art” or “state of knowledge”. According to UNICAMP’s teaching methodology teacher, Norma Ferreira (2002), this type of research had a significant volume since the end of the 1980’s in Brazil, being a bibliographical character that meets the challenge of mapping and discussing academic productions in different fields of knowledge, presenting under which forms, conditions and dimensions the works are highlighted in different times and places. In this sense, they are also recognized by the inventive and descriptive bias methodology with specificities in each work.

In this direction, starting from the construction of the theoretical framework and with the hypothesis that the relatively recent thematic in the discussions on Media education, Educommunication and Teacher training is little explored, the research began in the database Scientific Electronic Library Online Citation Index - SciELO Citation Index (SciELO CI) of access restricted by the journal portal of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

The integrated platform base Web of Science (WoS) of Thomson Reuters, available since January 2014, shares interface and functions similar to other databases4, which streamlines the treatment of search data. As a curiosity, the research round in this version was also performed in SciELO.ORG, free access, but the options for analysis and archiving of bibliometric indexes are better in the private version. The results were the same in both versions.

Due to the results, it was decided to also search the Elsevier Scopus base. For the possibility of crossing the data of the two platforms, the time cut was from 1997 to 2018 in both, in order to draw a broad panorama of studies: the last 20 years (will be considered until the year 2017, due to the lack of results in 2018, perhaps because it is at the beginning of this). The year of 1997 served as initial demarcation, since the academic literature is available in SciELO from that year.

The research had as objective to investigate works that present relations between the Educommunication and the teacher formation; as well as media education and teacher training, so the terms were not considered separately. In the searches the words were used in English, Portuguese and Spanish, in variations according to the sense that is used in each language. To consider this translation, some articles served as a basis for finding the most assertive terminology.

In this work, the number of papers from different countries was presented, indicating the number of publications per year. Another highlight was the distribution of the works by type of publication vehicles, considering the main sources of the subject. The authors who have produced mosto of the works on the subject, as well as the affiliated institutions, the graphical indexes by country and by area of knowledge were also identified. In order to understand the thematic aspects, we also presented the analyzes of the documents found.

By analyzing the numerical data, we sought to cross-reference information among the graphs to indicate possible indications regarding the scenario of publications on Media Education, Educommunication and Teacher Training in the last 20 (twenty) years of research, both in Brazil and in others countries. Knowledge of the studies developed with these correlations was also relevant to express the lack of work in the area.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The research in the databases was carried out on January 17, 2018. The first inves- tigations were in SciELO CI, which offers access to references with abstracts, complete texts and statistical data. Since 1997, the platform has gathered academic documents in several areas of study: Sciences, Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities, published in the main open access journals in Latin America, Portugal, Spain and South Africa. There are approximately 650 journal titles and more than 4 million cited references.

Among the search options by SciELO CI, we opted for basic research, using terms such as: educommunication and “teacher formantion”, dentre outros (todos apresentados nas Tabelas 1 e 2), among others (all presented in Tables 1 and 2), with the topic option that includes search of the phrases in the titles of articles, abstracts, keywords of the author, keywords created (keyword plus). The expressions were used in quotation marks for the exact search of the inserted term. Otherwise, as indicated in the search guidelines on the website, the selections are given for each separate word (teacher and formation). Another indication followed was the use of the expressions also in Portuguese and Spanish. The period was from 1997 to 2018.

TABLE 1 Research results on SciELO CI database

| DATABASE: SciELO CI | ||

|---|---|---|

| YEAR INTERVAL: 1997 to 2018 | ||

| LANGUAGES: English, Portuguese and Spanish | ||

| CONCERNING CONCEPTS: Educommunication and Teacher Training | ||

| SEARCH | TERM | RESULT |

| 1 | educommunication and “teacher formation” | 0 |

| 2 | educommunication and “teacher education” | 0 |

| 3 | educommunication and “teac her training” | 0 |

| 4 | educomunicação and “formação de professor” | 0 |

| 5 | educomunicação and “formação docente” | 0 |

| 6 | educomunicación and “la formación del profesorado” | 0 |

| 7 | educomunicación and “formación del profesorado” | 0 |

| 8 | educomunicación and “formación docente” | 0 |

Table 1 presents the data collection in 8 (eight) attempts by the terms: educommunication and “teacher formation”; educommunication and “teacher education”; educommunication and “teacher training”; educomunicação and “formação de professor”; educomunicação and “formação docente”; educomunicación and “la formación del profesorado”; educomunicación and “formación del profesorado”; educomunicación and “formación docente”. Note that despite several attempts at terminology combinations, no document was found.

TABLE 2 Research results on SciELO CI database

| DATABASE: SciELO CI | ||

|---|---|---|

| YEAR INTERVAL: 1997 to 2018 | ||

| LANGUAGES: English, Portuguese and Spanish | ||

| CONCERNING CONCEPTS: Educommunication and Teacher Training | ||

| SEARCH | SEARCH | RESULT |

| 1 | “media education” and “teacher formation” | 0 |

| 2 | “media education” and “teacher education” | 0 |

| 3 | “media education” and “teacher training” | 0 |

| 4 | midiaeducação and “formação de professor” | 0 |

| 5 | midiaeducação and “formação docente” | 0 |

| 6 | “educação para as mídias” and “formação de professor” | 0 |

| 7 | “educação para as mídias” and “formação docente” | 0 |

| 8 | “educación para los médios” and “formación docente” | 0 |

| 9 | “educación para los médios” and “la formación del profesorado” | 0 |

| 10 | “educación para los médios” and “formación del profesorado” | 0 |

Given the results, it was decided to expand the field of research, considering media education and teacher training. In 10 other rounds (Table 2), the terms used were: “media education” and “teacher formation”; “media education” and “teacher education”; “media education” and “teacher training”; midiaeducação and “formação de professor”; midiaeducação and “formação docente”; “educação para as mídias” and “formação de professor”; “educação para as mídias” and “formação docente”; “educación para los médios” and “formación docente”; “educación para los médios” and “la formación del profesorado”; “educación para los médios” and “formación del profesorado”.. But no publication was found, which draws our attention.

Further research was carried out on the same day (01/17/2018) at Scopus, the largest database5 containing abstracts, citations and statistics, indexed in more than 21.000 journals of 5.000 international publishers, with 24 million patents, in addition to other documents. The academic literature available for consultation is from the year 1960. The base has worldwide research coverage in the fields of Science, Technology, Medicine, Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities.

According to the search options in Scopus, the document search was chosen, using the same expressions of the researches in SciELO CI as: educommunication and “teacher formantion”, among others (presented in Tables 3 and 4), with the selection of research in article title, abstract and keywords. The terms were also used in quotation marks for the exact search of what was inserted, preventing separate selection (teacher and formation). To follow the pattern, in addition to English, Portuguese and Spanish were used. The year range of publications was from 1997 to 2018. It still had the type of document to be considered: the “all” option was chosen (review article, article, review, article in print, chapter of book or book, book, chapter of book, article or conference document, conference document, conference review, letter, editorial, note, brief survey, commercial or printed article, errata).

In Table 3 the eight (8) attempts to search for the phrases are shown: educommunication and “teacher formation”; educommunication and “teacher education”; educommunication and “teacher training”; educomunicação and “formação de professor”; educomunicação and “formação docente”; educomunicación and “la formación del profesorado”; educomunicación and “formación del profesorado”; educomunicación and “formación docente”. But no document was found.

TABLE 3 Research results on Scopus database

| DATABASE: Scopus | ||

|---|---|---|

| YEAR INTERVAL: 1997 to 2018 | ||

| LANGUAGES: English, Portuguese and Spanish | ||

| CONCERNING CONCEPTS: Educommunication and Teacher Training | ||

| SEARCH | SEARCH | RESULT |

| 1 | educommunication and “teacher formation” | 0 |

| 2 | educommunication and “teacher education” | 0 |

| 3 | educommunication and “teacher training” | 0 |

| 4 | educomunicação and “formação de professor” | 0 |

| 5 | educomunicação and “formação docente” | 0 |

| 6 | educomunicación and “la formación del profesorado” | 0 |

| 7 | educomunicación and “formación del profesorado” | 0 |

| 8 | educomunicación and “formación docente” | 0 |

Following the rationale used in the other database, the research continued with 11 other surveys, according to Table 4, the words used were: “media education” and “teacher formation”; “media education” and “teacher education”; “media education” and “teacher training”; “media education” and “teacher education” or “teacher training”; midiaeducação and “formação de professor”; midiaeducação and “formação docente”; “educação para as mídias” and “formação de professor”; “educação para as mídias” and “formação docente”; “educación para los médios” and “formación docente”; “educación para los médios” and “la formación del profesorado”; “educación para los médios” and “formación del profesorado”. Searches 2 and 3, “media education” and “teacher education” and “media education” and “teacher training”, found 22 and 33 documents, respectively. To refine the results and find the documents that compiled the universe of the two surveys, without repetitions of publications, the research 4 was generated: “media education” and “teacher education” or “teacher training”, with 48 references found.

TABLE 4 Research results on Scopus database

| DATABASE: Scopus | ||

|---|---|---|

| YEAR INTERVAL: 1997 to 2018 | ||

| LANGUAGES: English, Portuguese and Spanish | ||

| CONCERNING CONCEPTS: Educommunication and Teacher Training | ||

| SEARCH | SEARCH | RESULT |

| 1 | “media education” and “teacher formation” | 0 |

| 2 | “media education” and “teacher education” | 22 |

| 3 | “media education” and “teacher training” | 33 |

| 4 | “media education” and “teacher education” or “teacher training” | 48 |

| 5 | midiaeducação and “formação de professor” | 0 |

| 6 | midiaeducação and “formação docente” | 0 |

| 7 | “educação para as mídias” and “formação de professor” | 0 |

| 8 | “educação para as mídias” and “formação docente” | 0 |

| 9 | “educación para los medios” and “formación docente” | 0 |

| 10 | “educación para los medios” and “la formación del profesorado” | 0 |

| 11 | “educación para los medios” and “formación del profesorado” | 0 |

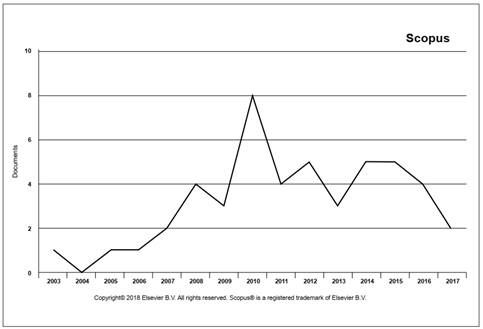

From these results, it was possible to analyze the publications by graphs generated by the Scopus database. Graph 1 shows the data broken down by year, with the first record of 1 (one) document in 2003, although the survey was done from 1997 to 2018. In the year after, 2004, no publication was made. The highest point with 8 (eight) publications was in 2010, after that there were fluctuations (2011 - 4, 2012 - 5, 2013 - 1, 2006 - 1, 3, 2014 - 5, 2015 - 5, 2016 - 4) until reaching 2 (two) works in 2017.

In an analysis of the last three years (2015, 2016, 2017), it becomes possible to indicate a decrease in the already scarce number of publications (5, 4, 2). This data is relevant to point out the need to broaden the studies correlating Media education, Educommunication and Teacher training, since the literature reaffirms the necessary updating of teacher education, including the cultural, social and political aspects of the digital society. Ismar Soares (2002) denounces that, despite the legal recognition for the teaching of the importance of studying the technologies and communication processes, as well as their languages, the lack of teacher preparation remains. Mónica Fantin (2012a) confirms that teachers turn to ICT only as a resource, however what is wanted is a “new” representation of technology as a culture and space of collaboration, also considering the processes that occur from it.

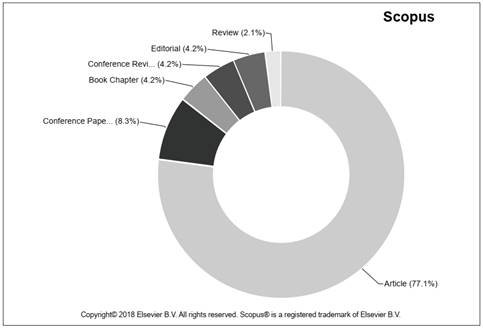

Figure 2 comprises the documents by types of publications. A significant data is that 37 are articles (77.1%). Another 4 (8.3%) are defined as a conference document, but are also articles published in this modality. In total, 48, 2 (4.2%) were book chapters, 2 (4.2%) conference proceedings, 2 (4.2%) editorial and 1 (2.1%) review (paper).

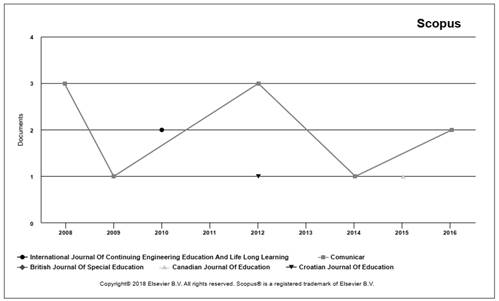

Regarding the sources, there is the occurrence of 28 means of publication. Figure 3, generated by Scopus, considers the first five (5) publications, considering the number of documents per vehicle. Although there is the option to select the sources you want to show on the site, this function has no effect on the graph. It was included, for example, the source of the first publication in the area made in 2003, but the chart was not changed.

The journal with the highest number of publications - 10 (ten) articles between 2008-2016, including a Brazilian one, was Comunicar, classified A1 in the Communication and Information, and Education areas, according to CAPES - WEBQUALIS Integrated System (quadrennium 2013- 2016). It is one of the most important and influential international journals in the areas of Education and Communication of quarterly and bilingual publication (Spanish and English), indexed in the Journal Citation Reports: JCR (WoS) - with Q1 evaluation in all areas; Scopus - by CiteScore and SJR is Q1 in Education, Communication and Cultural Studies; RECyT - is an excellence journal (2016/19), and in more than 270 international databases, catalogs and directories worldwide.

The International Journal of Continuing Engineering Education and Life-Long Learning had two (2) publications in 2010. It targets more specific studies related to education, engineering, technology, management, curriculum and design in engineering, virtual laboratories. It is available at Scopus database (Elsevier); The Compendex, former Ei (Elsevier); Academic OneFile (Gale); British Education Index (EBSCO); cnpLINKer (CNPIEC) and is recognized as an authorized source of engineering and management, training and career development. All other sources computed only one publication.

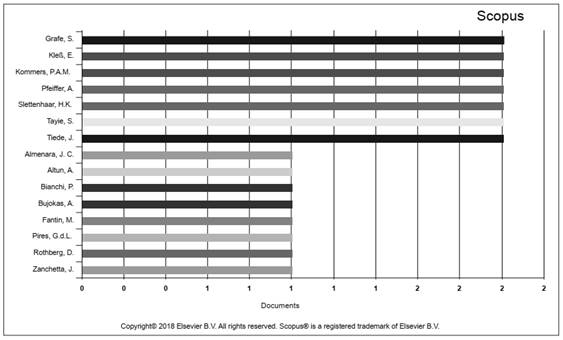

In the data representation by authors, the database selected (from 85 authors and coauthors) 9 researchers of works for the statistical data (7 with 2 documents and 2 authors with 1 work, chosen in alphabetical order). Since all the others (76) have 1 work and for the interest of knowing the representativeness of our country, Brazilians (6) were added to Chart 4, option allowed in Scopus. Among those who published the most were: Grafe, Silke (Julius-Maximilians-Universitat Wurzburg - Germany, published in 2015 and 2016); Kleß, Eva (Universitat Koblenz-Landau - Germany, 2011 and 2013); Kommers, Piet A.M. (University of Twente - Holanda, 2010); Pfeiffer, Anke (Universitat Koblenz-Landau - Germany, 2011 and 2013); Slettenhaar, H.K. (University of Twente - The Netherlands, 2010); Tayie, Samy (Cairo University - Egypt, 2012); Tiede, Jennifer (Julius-Maximilians-Universitat Wurzburg - Germany, 2015 and 2016). Another two that appeared were Almenara, Julio C. (Universidad de Sevilla - Espanha, 2011) and Altun, Adnan (Abant Izzet Baysal Universitesi - Turkey, 2011).

The national authors were: Bianchi, Paula (Universidade Federal do Pampa, 2015); Bujokas, Alexandra (Universidade Federal do Triangulo Mineiro, 2014); Fantin, Mônica (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, 2012); Pires, Giovani L. L. (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, 2015); Rothberg, Danilo (UNESP-Universidade Estadual Paulista, 2014); Zanchetta, Juvenal (UNESP-Universidade Estadual Paulista, 2009). Two of them are cited in the theoretical framework of this study: Fantin who researches in the areas of media-education, digital school culture and teacher training; and Zanchetta, who emphasizes practices of Portuguese language teaching, relations between media and education and educational policies, and teacher training.

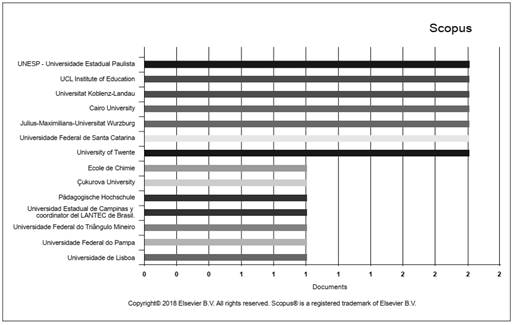

Figure 5 correlates the affiliated institutions (59) and the number of publications. The universities that indexed 2 (two) documents were UNESP-Universidade Estadual Paulista (Brazil); Institute of Education - UCL (London); Universitat Koblenz-Landau (Germany); Cairo University (Egypt); Julius-Maximilians-Universitat Wurzburg (Germany); Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (Brazil); University of Twente (The Netherlands). Two Brazilians stand out in this parameter. Other national that also appeared were: Universidade Estadual de Campinas and coordenator of LANTEC in Brazil (her article is as from Spain, so the authors did not appear in the previous chart); Universidade Federal do Triangulo Mineiro; Universidade Federal do Pampa. The Lisbon University (Portugal) was also listed, along with Ecole de Chimie (Switzerland); Çukurova University (USA); Pädagogische Hochschule (Germany).

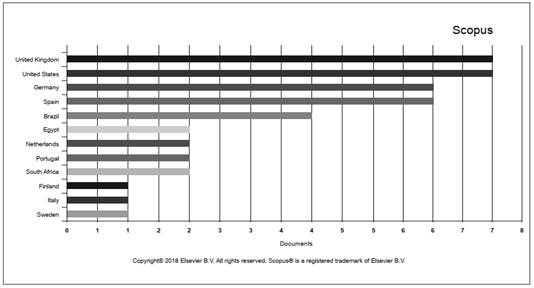

The distribution of publications by country (out of 23), according to Figure 6 generated by the base, presents the United Kingdom and the United States as the ones that produced the most, with 7 (seven) documents, followed by Germany and Spain, 6 (six) contributions. Brazil remained in fifth with 4 (four) productions. Other countries tied, with 2 (two) publications: Egypt, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa. While Finland, Italy and Sweden had 1 (one).

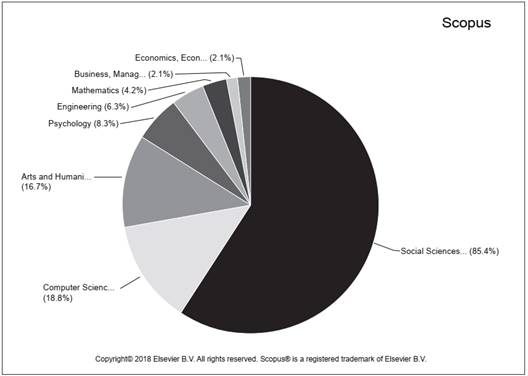

The last one, figure 7, shows the areas of knowledge that cover the publications. It was observed that the Social Sciences contain the largest percentage share of 85.4%, which represents 41 documents. This data confirms that the subject has been studied by an interdisciplinary bias in which the issues are found in the interface of Sciences, like: Education, Communication, Sociology, Linguistics, Philosophy, among others, according to the other data presented (Computer science - 18.8%, 9 works; Arts and Humanities - 16.7%, 8; Psychology - 8.3%, 4; Engineering - 6.3%, 3; Mathematics - 4.2%, 2; Business, Management and Accounting - 2.1%, 1; and Economics, Econometrics and Finance - 2.1%, 1 document).

In the total of 48 publications, two were repeated: 1 - An adaptive teacher in an ever-changing ICT society - Slettenhaar, H.K., Kommers, P.A.M., 2010; 2 - IMSCI 2010 - 4th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and Informatics, Proceedings, 2010. Therefore, the amount for 46 documents is confirmed.

In the analysis of these publications, a number of studies that dealt only with teacher education were carried out (examples of topics: 1 - the need for a unified language (English) in the training of mathematics teachers in South Africa; 2 - political, legislative change and their effects on inclusive and special education in Wales; 3 - the profiles of candidates and participants in the initial teacher training program - Ireland DGO;).

There were those who came closer to the media, reporting experiences: 1 - MindRap project that explores concepts of mathematics and science through hip-hop and multimedia culture in Arizona (USA); 2 - Media Protect program of counseling to primary school parents to prevent children’s problematic use of “screen media”; 3 - HyFlex model for blended learning, the text elucidates positive aspects and obstacles for implementation in teacher training.

Other studies were mainly concerned with the resource, with the operationalization of the environment: 1 - TV advocacy as an educational tool for children; 2 - research carried out in primary schools in Brazil that intends to show the pedagogical possibilities of television when using digital video. In addition to some who have turned to critical analysis, the reading of the media messages: 1 - teaching to watch television with “critical sense”; 2 - education in the Spanish classroom using cinema.

Among other such specific issues as: 1 - historical, political and sociological explanations for media education in the USA be delayed compared to other English speaking countries; 2 - “Prefácio: ‘Tudo o que você pode fazer’: propostas para educação artística lésbica e gay”; 3 - “Origens do ensino médio Irlandês: o núcleo dinâmico da revitalização da língua na Irlanda do Norte”; that it was necessary to list parameters for the analysis of what could in fact contribute to reflect the issue in an associated way.

Thus, in an attempt to refine the data so that the analytical dimension of the documents was also contemplated, some criteria were defined for the selection of the 46 documents, namely: - teacher training / teacher training and media education / education for the medias / media education in the title, abstract, or keywords (despite quoting in quotes, some cases presented only one of the terms); - that the center of the issue was related themes, without tangential appropriation of teacher training; - the document would also have to have open access so that it was possible to understand its approach beyond the abstract.

Thus, a total of 8 (eight) papers were included, being thus listed and commented with the following information: title, authors, country, type of document, publication source, year and synthesis of the approach.

Media pedagogy in German and U.S. teacher education. Tiede, J., Grafe, S. Germany. Article. Comunicar, 2016 - the article made a comparative, theoretical and empirical study on pedagogical media skills in teacher training in Germany and the USA. It considered media pedagogy as the interaction of 3 (three) fields: teaching with the media, teaching about media (media education), and school-related media reform. Among the results, he showed that in the USA, teacher training focuses on teaching with the media, neglecting other areas, and in Germany there is the same trend, but media education and school reform are more emphasized than in the United States. In short, it found that despite the recognition of teachers and research on the importance of studying media in training, current curricula do not reflect this need.

Digital competence for the improvement of special education teaching. Cappuccio, G., Compagno, G., Pedone, F. Italy. Review (article). Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 2016 - the review described an experience report of a qualification course dedicated to teachers (91 - 79% trainees and 21% graduates) to develop media skills. Through the use of ICTs were structured educational activities in a specific learning environment (e-portfolio) with the objective of developing the media competence in the technological, cognitive and ethical dimensions. The improvements observed in all teachers were: - selective capacity to extract correct information needed to solve a problem; - ability to use hypertext structures efficiently; - ability to read and understand texts; - ethical competence for media activities. Finally, they reinforced that media competence enhances teachers’ ability to creatively modify learning spaces and design a variety of stimulating activities to promote independent and conscious student work.

Digital culture and th e training of physical education teachers: A case study at Unipampa. Bianchi, P., Pires, G.L. Brazil. Article. Movimento, 2015 - the study presented a case study that investigated the inclusion of ICT curricula in teacher training in the Physical Education course of Universidade Federal do Pampa (Unipampa). The analysis of proposals related to ICT was based on the three dimensions of media-education: instrumental, critical and expressive-productive. From the analysis of the Pedagogical Project of the Course, of curricular components and of interview with teachers that had relation with the subject, it was concluded that there is a limited use of the ICTs in the curriculum, with emphasis in the disciplinary approach. This complicates the curricular integration of the subject with educational dialogic and interdisciplinary proposals. The activities in critical and/or productive media-education perspective are even scarcer.

Pedagogical Media Compete ncies of Preservice Teachers in Germany and the United States: A Comparative Analysis of Theory and Practice. Tiede, J., Grafe, S., Hobbs, R. Germany and USA. Article. Peabody Journal of Education, 2015 - the research correlated, in comparative analysis, the pedagogical media competency models of Germany and the USA. Based on literature and teacher training programs in both countries, it was defined that there are basically three ways of acquiring media pedagogical knowledge in both countries: - as an optional and elective course during basic teacher training; - as an additional certification course for trainees or newly graduates; - postgraduation focused on some aspect of media pedagogy. In Germany, most courses focus on media education, technology skills, and media education. In the USA there are more courses to train qualified specialists for the integration of media in schools and specializations focused on technological competence and teaching with media. Another difference is the greater offer of courses on media pedagogy in the United States, 52% of universities. While in Germany only 19% of institutions offer these types of courses. The article concludes that in the two nations there is still no satisfactory national inclusion in teacher training in teaching with and on the media, despite the recognition of the importance of media pedagogy and its respective prescriptions published in official documents.

Teacher training in media education: Curriculum and international experiences. Pérez-Tornero, J.M., Tayie, S. Spain and Egypt. Editorial. Comunicar, 2012 - the editorial first established a historical and conceptual presentation of UNESCO’s media and information literacy curriculum for teachers (2008 was the beginning of its development, dissemination and testing) and then to show some expert approaches (Canada, Spain, South Africa, USA, Egypt, Finland, Portugal and Venezuela) on the manual and the reality in its compiled in articles published in this issue of the journal. It highlighted the constitution, in the year of publication of the UNITWIN platform manual (2011), a cooperation program for media literacy and intercultural dialogue, between UNESCO, the Alliance of Civilizations of the United Nations and eight universities (University of São Paulo - Latin America; Temple - North America; Autonomous University of Barcelona - Europe; Cairo - Africa; University of the West Indies - Caribbean; Tsinghua University - Asia; Queensland University of Technology - Oceania; Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University - Morocco). Its objective is to promote curriculum development, as well as academic research and intercultural dialogue.

Media education in schools and curriculum as a cultural practice. Fantin, M. Brazil. Article. Currículo sem fronteiras, 2012 - the study pointed out that to reflect the media education in education it becomes necessary to discuss curricular aspects, due to the possibility of diverse forms of realization, such as: autonomous discipline, transversal curriculum, thematic nuclei and others linked to cultural media practices. Thus, it reflected the dissonance between the presence of the media in the daily life and in the culture of the children and young people and their almost absence in the formation of teachers and in the school curriculum. The researcher concluded that, in addition to the various modes of curriculum insertion, mediation in initial formation should articulate its form and content to the theoretical-practical dimension, being a condition of belonging and of instrumental and cultural citizenship, and that the issue of media-education in teacher training presents only one aspect of the problem. In addition to the democratization of access to technology and training that goes beyond the instrumental aspect, a digital inclusion of teachers that is also social, political and cultural must be on the agenda.

Media literacy in the initial teacher education. Almenara, J.C., Liaño, S.G. Spain. Article. Educacion XX1, 2011 - the authors verified the media literacy in the initial formation of the teacher of several stages (pre-school, primary, secondary) at the Faculty of Education of the University of Cantabria. They argued that teacher training in media literacy can ensure a critical attitude towards the media by better understanding the messages, techniques, tools, strategies, being less vulnerable and easily influenced, and recognizing and valuing the environment in which they live for a participatory and responsible citizenship. Two questionnaires were applied, one before and one after the media training, with a total of 137 respondents. After the course, some differences were observed for more critical and reflexive attitudes with improvements in skills, such as: selecting information, comparing the same information, identifying stereotypes and prejudices, questioning the veracity of information, etc. Another change was the confirmation of the obligatoriness of the theme in the curriculum in formation. Finally, they also detected the lack of content and learning practices in media literacy, which could be expanded and improved.

Attitudes of a sample of English, Maltese and German teachers towards media education. Lauri, M.A., Borg, J., Günnel, T., Gillum, R. Malta and Germany. Article. European Journal of Teacher Education, 2010 - the research investigated the attitudes of a sample of teachers trained in England, Malta and Germany on the perceived importance of media education and teacher preparation to teach the subject. Although media education is part of the minimum curriculum of these countries, and after three decades of its introduction, initial teacher education differs greatly. By questionnaire, a sample of 132 teachers (33 - England, 47 - Germany, and 52 - Malta) reported that they were not sufficiently trained on the subject and therefore did not feel able to teach media education. The production of television, radio and website design were the areas where Maltese, English and German participants felt less qualified. Therefore, they suggest that media education becomes a mandatory component in initial training and also an advanced course for teachers.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In this work, we sought to consider the media as socialization institutions that work in parallel to the school. They are social, political and ideological spheres that fulfill functions of social control, generating other ways of perceiving reality, of learning, producing and disseminating information and knowledge. It was also emphasized the understanding of the cultural products of the media as a privileged process of exchange of knowledge, of the possibility of constructions critical, creative and reflective. For all this interference in social life, the communicational processes must be studied in an inter/transdisciplinary perspective.

Thus, it was reaffirmed that Media education, from the Educommunicative point of view, can contribute to a re-evaluation of the relationship between education and communication by the formation of more aware audiences of mediation processes and by a plural, inclusive and participative society, since it gives prominence to the communicative process as a primarily “cultural” problem, subordinating the issues of the media. Thus, communication through this direction is no longer seen merely as a code, a language to be decoded, to be assumed as an essentially human and political phenomenon in which the interactive agents exercise practices of negotiation of meanings that directly interfere with the forms of self-construction and their practices in the world.

The bibliometric research has demonstrated the scarcity of national and international work that has developed fruitful perspectives for a teacher training that is consistent with an inevitably digital culture. This ratifies an academic niche that is still little explored by researchers, despite the urgent needs for solutions to the challenges that require updating of educational contexts.

Among the studies selected for analysis, comparative studies of countries in search of the “level” of media competence were seen. This reflects a series of uncertainties, because the comparison calls for the equalization of conditions: but how is it possible to approach such diverse (cultural, economic, social, educational) realities? How to “equalize” such specificities and determine criteria that can be considered in both realities? Despite this, it is recognized that some possibilities of answers may arise from these surveys. Above all, the examples of actions developed in each country, with projects that can be readapted to other realities. But, by the path taken for the researches, some issues were appearing in the analysis.

Despite some interesting initiatives in the study of the media, training courses were predominant in the notions related to the operation of ICTs, to instrumental use, with an emphasis on the disciplinary approach. Those who went a little further were confined to a denunciist, a protectionist reading of the messages of the mass media, being few activities in a critical perspective to show positive and negative aspects and to stimulate productions in media education.

This finding denounces difficulties or resistance in integrating into the curriculum and the pedagogical project of the course the theme with dialogic and interdisciplinary educational proposals. The grateful surprise was the recognition by teachers (in the process of formation and those who already work) of the indispensability of media education to become a mandatory component in initial teacher formation, and also advanced courses for teachers.