Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. Rev. vol.34 Belo Horizonte 2018 Epub 20-Set-2018

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698192251

DOSSIER

EDUCATION: BETWEEN THE POTENTIALITIES AND CHALLENGES OF THE PEDAGOGICAL PRACTICE

1Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, SC, Brazil.

2State University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, SC, Brazil.

If the school curriculum is observed, it becomes obvious that knowledge is still hegemonically euro-centric, contributing to the unequal treatment in the schooling of the black population by not taking their history into account. In this sense, the inclusion of knowledge about the education of ethnic-racial relations and about Afro-Brazilian and African history and culture, led by the black movement, represents a political and pedagogical advance in the history of Brazilian school and education. Studies already carried out on the subject are also discussed, highlighting the announcements made to overcome the challenges that arise from and for this educational modality. The field chosen as the locus of analysis is the youth and adult education developed in a capital of southern Brazil.

Keywords: Youth and adult education; Race relations; Pedagogical practice

Se observado o currículo escolar constata-se que os conhecimentos ainda são hegemonicamente de base eurocêntrica, contribuindo para o tratamento desigual na escolarização da população negra ao não levar em conta sua história. Neste sentido, a inclusão de conhecimentos sobre a educação das relações étnico-raciais e sobre a história e cultura afro-brasileira e africana, protagonizada pelo movimento negro representa um avanço político e pedagógico na história da educação e da escola brasileira. O presente artigo problematiza a prática pedagógica na educação de jovens e adultos a partir da pesquisa-ação, realizada entre coordenação pedagógica e professores, tendo como foco a educação das relações étnico-raciais. São também abordados estudos já realizados sobre o tema, evidenciando os anúncios que se fazem para a superação dos desafios que se colocam para essa modalidade educativa. O campo escolhido como lócus para a análise é a EJA desenvolvida em uma capital do sul do Brasil.

Palavras chave: Educação de jovens e adultos; Relações raciais; Prática pedagógica

INTRODUCTION

Racism structures social and economic inequalities in Brazil and perversely affects the black population, determining their conditions of existence for generations. When constituted as an element of social stratification, racism materializes in the culture, behavior and values of individuals and institutions, perpetuating an unequal structure of social opportunities for 53.6%1 of the Brazilian population2.

At the end of the 1970s, studies carried out by Hasenbalg and Silva (1979, 1988) proved that the economic and social inequalities between white and black people were not explained by heritage of the slavery past. They are a consequence of racism, in which “race” becomes an “effective criterion among the mechanisms that regulate the filling of positions in the class structure and in the social stratification system” (HASENBALG, 1979, p. 20), implying differences of opportunity in the most varied sectors of life and in the forms of specific treatment to the black population.

Likewise, when analyzing the evolution of inequality between white and black people, Henriques (2001) bluntly highlights the intense inequality of opportunity to which the black population is subject in Brazil. More recently, the research “A distância que nos une - Um retrato das Desigualdades Brasileiras”, carried out by the British non-governmental organization Oxfam (2017), projects that only in 2089, at least another 72 years from now, white and black people will have an equivalent income in Brazil.

Researcher in education, such as Gomes (2000, 2011), Silva (2004, 2005, 2007), Passos (2005, 2010, 2012), Henriques (2001), Cavalleiro (2000), Munanga (2000, 2005, 2011), have also seen prejudice and racial discrimination, whether in curriculum, pedagogical rituals, expectations related to students’ performance in the teacher-student relationships, percentage of failure, dropout, age-grade distortion and completion of primary and secondary education, in the greater presence of black people in the youth and adult education, in the repercussion of quotas for black students in higher education, in the few educational opportunities offered by the public system to young people and adults, in the reproduction of racism in textbooks, among others.

The discussions brought by these researchers, and others, have been pivotal for us to move forward in comprehending the structural and institutional racism in the Brazilian society, since their studies dialogue with the daily practices of prejudiced and racist manifestations and identify the impact of the idea of race in the schooling process of black students. They observe that educational institutions have historically passed on and reproduced racism. In this sense, Munanga (2000, p. 235) mentions that “even in the most peripheral and marginalized schools in the public system, where all students are poor, the students with the worst impact in terms of unsuccess, failure, repetition of the school year, and dropout are those of black ancestry, that is, black and mestizo students”. If the school curriculum is observed, it’s observed that knowledge is still hegemonically Eurocentric, contributing to the unequal treatment in the schooling of the black population by not considering the Afro-Brazilian and African histories and cultures.

Data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) show that in 2010 Brazil had 12,893,141 million illiterate people with 15 years or more, and 66.7% of these were black. In this population, based on household sampling survey by the Brazilian Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP) in 2015, only 3,738,852 million were enrolled in youth and adult education classes to finish primary school. These numbers show the inequalities in schooling, especially for the black population, in addition to pointing that the educational institutions do not solve the real demand of people focused on youth and adult education.

A consequence of colonialism, the Brazilian society in the 21st century carries the marks of a remarkably racialized country and with abysmal inequalities between black and white people. Fanon (2005, p. 56) in Condenados da Terra already called our attention to the fact that: “What fragments the world is first the fact of belonging or not to such a species, such a race. In the colonies, the economic infrastructure is also a superstructure. The cause is consequence - someone is rich because they are white, someone is white because they are rich”. In portraying the colonized world, he says that this is divided in two, the city of the colonist and the city of the colonized. In the latter, “one is born anywhere, one dies anywhere, anyhow, (...) a hungry city, hungry for bread, meat, charcoal shoes, light” (FANON, 2005, p. 56). We see in Fanon’s description much of Brazil today and thus we say with him and other scholars of decoloniality that the idea of race will constitute a structuring axis of social, economic and political relations in the countries that went through the process of colonization. Although the colonization process is concluded, coloniality remains in force as a thought scheme and actions legitimizing the differences among societies, individuals and knowledge. In this sense, we use race as a category for central analysis to understand the material and symbolic inequalities experienced in the 21st century by the indigenous and black population.

This brief exposition helps to identify that analyzes of racism and school disadvantages of the black population have expanded, and with them the possibilities of better understanding the phenomenon of racial inequalities in education and the mechanisms of discrimination existing in pedagogical practices. Here, we consider that the pedagogical practices for education of ethnic-racial relations gather not only theory and practice, or the reflection on a generic pedagogical practice, but overall it is the antiracist reflection and practice. In this sense, this paper problematizes the pedagogical practice in youth and adult education (EJA, in Portuguese)3 focusing on education of ethnic-racial relations and the locus of analysis is the EJA developed in a South Brazilian capital. For this, we used the research-action methodology, here understood as a “a type of social research that is conceived and carried out in close association with an action or with the resolution of a collective problem, and in which the researchers and the participants representing the situation of the reality to be investigated are involved in a cooperative and participative way” (THIOLLENT, 1985, p.14). Although we understand EJA as educational processes and practices developed throughout a lifetime, inside and outside of the school universe, youth and adults being the active subjects, in this paper, we consider only the schooling experiences, since these do not constitute yet a right for a significant part of the black population.

EDUCATION OF ETHNIC-RACIAL RELATIONS AND SUBJECTS OF YOUTH AND ADULT EDUCATION

The need to adapt the pedagogical projects and curricula of EJA to the subjects is presented in the main documents that regulate and guide this educational modality and has been much discussed by scholars,4 by the social actors involved in the youth and adult education5 fora, and by the government. There is consensus among them about the need for curricula that dialogue in the formative paths and pedagogical practices with specifics (color/race, gender, sexual orientation, class, generational, among others), expectations, needs and realities of the Brazilian society, especially of young and adult students.

The text of the Law on Brazilian Education Guidelines and Bases (LDB), Federal Law 9394/96, for example, points out that this modality must respect the characteristics, needs and peculiarities of students from age 15, valuing the non-school knowledge that they have. In CEB/CNE Opinion No. 11/2000 on the National Curricular Guidelines for Youth and Adult Education, EJA is considered a social debt that points out the needs of historical subjects, holders of the right of access to education beyond certification, thought out as a process throughout life and based on quality.

Thus, if the conception of EJA is guided by the recognition of youth and adults as full subjects by right, the educational practice will experience at some level the effort to move towards the attempt to overcome the perspective of students as people lacking knowledge and will recognize them as young people and adults in their particularities of social, gender, sexual orientation, ethnic-racial, generation, class conditions, and recognize them as capable of constructing interventions. Therefore, EJA begins to be thought of as and education aiming to support the subjects in the various aspects of life, punctuating the transience of thought and knowledge historically accumulated by humanity, to emancipate, show solidarity and respect the diversity experienced by people. Faced with this understanding, what curricula and pedagogical practices we need to reinvent to meet the peculiarities of the EJA subjects? Arroyo seeks for answers to this question, focusing on the collective subjects. He says we must:

Recognize young people and adults as members of the collective (...). Overcome the idea that we work in individual paths, to try to map which groups are attending EJA. The black collective, the poorest collective, the collective of workers, the collective of the unemployed, the collective of women. What are these collectives? It is something different to think of a curriculum for individuals, to correct individual tortuous paths. Thinking about knowledge for collectives, issues concerning the collective dimensions, thinking about the history of these collectives. Something that draws attention to these collectives is the struggle for their identity, the struggle for their culture: black culture, African memory, quilombola memory, memory of the countryside, memory of women, memory of those affected by dams. Those are the great questions that they pose. When it comes to school, no one remembers who were affected by dams, who are quilombola, who are from the countryside, who are from the landless movement, it does not matter. It is simply someone who is on stage A, stage B, in the first segment, in the second segment. (...) What could this mean for an EJA curriculum? (ARROYO, 2011, p. 15-16).

The questions presented by Arroyo refer to the necessity of knowing and valuing the collective trajectories of youth and adults who frequent EJA, so that these become the guiding basis for the curricular construction and pedagogical practices. His considerations attract attention to the need to create a dialogue between schooling practices and the educational practices that occur in other spaces, significantly pedagogical, when considering social participation, cultural groups, fights for recognition, social movements.

Regarding teachers’ formation, Arroyo (2006) points out that to know the specificities of the youth and adults in the popular layers of society who are in EJA should be the core of the education. The peculiarities of their “social, ethnic, racial, cultural and space conditions (of youth and adults from the countryside, towns, favelas) have to be the point of reference to construct an EJA and for a corresponding profile of the educator” (ARROYO, 2006, p. 23). Considering the youth and adult subjects as central in the formation, other questions can be included, such as the domain of the pedagogic theories, and even “to invent a Pedagogy of the adult life, of the youth” (p.24). The history of the human rights along with the movements for the right to education is another aspect suggested by the author, to whom “it is impossible to be an educator of youth and adults without being conscious of this trajectory, the bonds between EJA and fights for rights” (p.28). For Arroyo, educators must be enabled in the domain of the “lively knowledges”, which are the collective knowledges (of work, history, experience, culture and nature), that the youth and adults have “to learn to resignify and organize in the light of the historical knowledge” (p. 31). If the guidelines above were considered, the questions racial-ethnic would be contemplated.

However, although EJA has a strong black presence, that does not mean that the racial-ethnic belonging and the Afro-Brazilian and African histories and cultures integrate the curriculum and the pedagogic practices there developed. On the other side, the intention is not for racial questions to be approached only when there are black students, but instead that they become principles, knowledges, attitudes and values for all, regardless of color/race, forging new ethnic-racial relations in the Brazilian society.

As emphasizing by the Documento Base Nacional Preparatório à VI Conferência Internacional de Educação de Adultos (BRASIL, 2009), to recognize in EJA the diversity as substantial in the historical-cultural-social and racial-ethnic constitution of the Brazilian society means to surpass those aspects that are the mark of colonizing processes, proslavery, elitists represented by the superiority of physical standard, mentality, world perspective, authoritarian hegemony of the cultural matrix of European, white root. Surpassing discrimination and discriminatory social practices that reinforce inequalities. In this sense, it is necessary to highlight the historical claims and formulations of the black social movements regarding the legal landmarks for teaching of Afro-Brazilian and African Culture and History, mainly strengthened from the deliberations of I World-wide Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Forms of Intolerance that drive the introduction in the structure of the Brazilian State of the Secretariat for the Promotion of Racial Equality (SEPPIR) with Ministry status, and Secretariat for Continuing Education, Literacy and Diversity (SECAD) in the Ministry of Education.

But how education of ethnic-racial relations and the teaching of Afro-Brazilian and African history and culture have been approached in EJA?

Law 10639/03 altering LDB 9394/96 and making teaching of Afro-Brazilian and African history and culture compulsory has turned 15 years. It is the result of struggles, complaints and historical pressures of the black social movement for an education that makes the existence of racial-ethnical diversity and more democratic and plural relations possible in the school institution. It can also, in Gomes’ perspective (2012), be considered as an answer of the Brazilian State to the demands for a more democratic education and with the right for racial-ethnic diversity. However, “the effectiveness and the implementation of the legal devices, mainly related to the racial questions, depend greatly on a set of conditions that allow for their full realization” (GOMES, 2012, p. 24), such as teaching formation, up-to-date pedagogic projects, work conditions and arrangement to break with preconceived ideas and pedagogic practices that reiterate racism and the myth of racial democracy. In this scenery, researches problematizing and discussing the successful pedagogic practices on racial relations in the context of youth and adult education are infimal, as pointed by Carvalho and Valentim (2014).

YOUTH AND ADULT EDUCATION AND THE RESEARCH AS EDUCATIVE PRINCIPLE

The curricular proposal of the youth and adult education of the RME (Municipal Education Network) of Florianópolis since 2001 declares as philosophical and methodological conception the research as an educational principle. In the way this perspective is declared in documents and pedagogic discourses, it constitutes as the main guiding axis of the organization of the pedagogic work that is carried out. In this sense, the research understanding in the curricular proposal places it as a practice subject to being executed in the daily life, by all human beings, regardless of age, level of knowledge, or social conditions, and withdraws it from the exclusive locus of the academic experiences. Before focusing on this aspect, it is relevant to present although shortly the EJA structure in the city.

Youth and adult education of the Municipal Education Network (RME)6 has as target public people from 15 years of age who did not end the Elementary School. Youth and adults have the possibility to join in any school day, which can mean an understanding on the rights of the students of EJA. In other words, for young and adult black men and those of popular classes, unlike the other students of the basic education, the centrality, in this moment of their lives, is survival and not school. In this case, regular work, informal work, or the search for these become the main activity (PASSOS, 2010). With a proposal that longs to consider the peculiarities of the trajectories of the students and to contribute so that they do not give up studying, EJA of the RME proposes a course of 1600 hours based on the formulation of student research problems, a starting point for learning.

In legal terms, EJA is organized by the Resolution of the Municipal Council of Education (CME) 01/2008 that establishes the organization of EJA as a classroom course of Elementary School functioning in cores. These must have a physical structure adequate for the school activities, and the pedagogical team is composed by coordinator and teachers of all the disciplines set for Elementary School. It functions in cores and poles, in accordance with the students’ demand, being distributed by the regions of the city: Center, South, North and Continent.

The cores are created from a demand identified by the Department of Youth and Adult Education - DEJA, or through the request of communities of the city via different entities, as long as it reaches a minimum number of students. They can be installed in association with the communities or neighborhoods. In this sense, in each year the number of cores can vary, as well as the poles linked to them and the number of students. In other words, in the same way the cores are created, they also can be suspended depending on the number of students, producing certain tensioning between the recognition of the right to education for youth and adults and the political administrative strategies to compose its offer.

In 2017, EJA was distributed in seven cores, and the majority was functioning in schools of the Municipal Net at night time, but some were also functioning in partnership with communitarian entities and other places under responsibility of the town hall, such as libraries, for example. The core of EJA Center I - Morning is the only one that works with morning and afternoon groups. If a core functions in a space of an educational RME unit, “students, teachers and coordination will be able to access it and to use all spaces and existent resources in the Unities” (CME Resolution 01/2008, p.4).

In the exemplified year, the cores were working so distributed, in accordance with the website of the Municipal Secretary of Education (SME):7

TABLE 1 Distribution and location of EJA cores

| Core Name | Core head office (school and neighborhood of the core) | Advanced Poles |

|---|---|---|

| Center I | Escola Silveira de Souza (Center) | EJA Núcleo de Educação da Terceira Idade (NETI/UFSC) (Trindade) |

| ASGF (Ass. de Surdos da Grande Florianópolis) (Centro) | ||

| Center II | Escola Silveira de Souza (Center) | Escola Básica Municipal (E.B.M.) Donícia Maria da Costa (Saco Grande) |

| ASGF (Associação de Surdos da Grande Florianópolis) (Center) | ||

| EJA Continent I | E.B.M. Almirante Carvalhal (Coqueiros) | EJA Biblioteca Barreiros Filho (Estreito) |

| EJA Continent II | Centro de Educação Popular (CEDEP) (Monte Cristo) | Projeto “Geração da Chico” (Chico Mendes) |

| EJA North I | E.B.M. Herondina Medeiros Zeferino (Ingleses) | EJA E.B.M. Maria Conceição Nunes (Rio Vermelho) |

| EJA E.B.M. Henrique Veras (Círculo de Leitura e Escrita) (Lagoa da Conceição) | ||

| EJA North II | E.B.M. Osmar Cunha (Canasvieiras) | - |

| EJA South I | E.B.M. Professor Anísio Teixeira (Costeira do Pirajubaé) | EJA E.B.M. João Gonçalves Pinheiro (Rio Tavares) |

| EJA E.B.M. José Amaro Cordeiro (Morro das Pedras) |

Source: Prepared from the website of the City Hall of Florianópolis.

In 2017, the activities of EJA attended 1450 students in forty groups distributed by the city, with a total of 440 students between literacy and conclusion of the Elementary School. All the students were computed without generational and racial-ethnic cut of, since the managing system does not have this distinction in generating reports. It is also important to note that for the data collection of race/color of the subjects attended in the modality, it is necessary to access the physical enrollment records with the self-declaration question.8 The absence of these data in the system prevents an analysis in depth on the students’ profile to be carried out by investigators external to the municipal network, as well as makes the monitoring of policies specific for the black population in the city unfeasible, in particular in the modality that is the subject of this paper.

When EJA hold the trajectories of life of the people as a constitutive element of the pedagogical organization, the present time of Paulo Freire (1996) is realized, since for him to teach is to create the means for producing or constructing knowledge. In this dialectics between teacher and student, there is learning and teaching for both, where a process depends on the other, demanding criticality. In another text, Paulo Freire and Antônio Fagundez (1986), in a dialogue in the book Por uma pedagogia da pergunta, criticize the fact that the school pedagogical practices gradually discourage students to ask questions, including for withdrawing of the teaching subjects their place of comfort, as holders of knowledge. For the authors, questions are a starting point for any learning, especially because education should not be on the students, but with the students, with the imagery of a researcher teacher.

Several authors, such as Miguel Arroyo (2011), Nilma Lino Gomes (2011), Olga Celestino Durand (2011), punctuate that the EJA subjects present a tense relation with the schooling knowledge, permeated by disapproval, labeling, standards and exclusions. The cracks in the educational system forsake the students of the school, and in EJA it is suggested that new interactions are established, thus the research as an educational principle. Many of the schooling knowledges are not under domain of this population of students, however, they compose a group of subjects with other knowledges, acquired in different spaces and existences, loaded with wisdom and experiences, able to develop creative strategies to deal with the daily situations.

In this sense, Berger (2009, p. 28) says:

The difficulties of understanding the specificities of this modality have led to the search for regular education as a format to be applied in EJA in a configuration summarized in elementary or middle school, where the youth and adult are seen as children. That is, it is considered that since they had not completed the basic education at the appropriate time, EJA students, seen as “late”, should have access to the same contents, but compacted, disregarding their specific objectives.

The difficulties pointed out require criticism directed to the research as an educational principle adopted in EJA by the RME of Florianópolis, since it conceives learning only as classes divided by year, age group and curriculum dismembered in disciplines and contents previously defined by the teacher. By explaining how EJA is organized and develops its pedagogical practices through research, we highlight the choice for this path as a means to value and have as a starting point the knowledge of its subjects, not ignoring the school knowledge involved in this pedagogical process. Caderno de 2008 (p. 12-13), a document published by the RME, presenting EJA from its bureaucratic to pedagogical organization, including punctuating the steps on how doing research and the constituent elements of the evaluation, argues that it is wrong to think of EJA as absent from the curriculum due to researches:

This does not mean that all EJA’s work is summarized in orientating research. The collective planning carried out by the core twice weekly should propose interventions from several different strategies aimed at significant learning for students, such as workshops, lectures by teachers and the community, courses {...}.

From the research problems of the students and the periodic pedagogical meetings, teachers discuss the best paths for the activities related to each research developed in the core. In this sequence, the teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian culture and history is possible without the limiters: pre-established program contents and/or textbooks limiting class preparation. The possibility of a certain pedagogical autonomy in the EJA proposal of the RME, for Santos (2016), in many cases, runs into the absence of initiative of teachers, the whiteness and the lack of interest in seeking materials that are pertinent to the researches. However, it should also be considered that although CNE/CP Resolution n. 01/2004 stipulates that “Higher Education Institutions will include in the contents of disciplines and curricular activities in the courses for Ethnic-Racial Relations Education, as well as approaching issues and themes concerning Afro-descendants” (BRASIL, 2004, Art. 1, § 1), the initial formation in licentiate courses most of the time does not assume the education of ethnic-racial relations as valid and necessary knowledge to be taught, as already verified by Passos (2014) when analyzing the curricula of the courses of Pedagogy and History offered in Santa Catarina. Moreover, the understanding that inequalities in Brazil derive from class sets a hierarchy in which race relations, gender, sexualities occupy a secondary place in the curricular field.

Procedural and permanent evaluation of research is done through some instruments, such as: research notebooks, where the students record all the steps and the chain of research in progress; individual diary, where the “memory” of the day is written at the end of the period, as well as activities proposed in classes and/or workshops, feelings, experiences and demands; extra class activities of their own initiative or proposed by the teachers (called external production time - HPE); reports of field study; materials for the socialization of research (manual and computerized); Research Evaluation Form, elaborated by at least two teachers who witnessed the final socialization of research and final research text elaborated by the student, both socialized with the teachers in a core planning meeting.

During the development of the investigation, it is needed to consider the student in their multiple dimension when starting the research process, and realize forms of expression, as suggested by Zaballa (1998), beyond the written format. Orality, involvement and dedication throughout the research in EJA are important parameters when consolidating the evaluation process.

Research as an educational principle developed in EJA of the RME has been previously discussed by Nunes (2008), Magalhães (2009) and Passos (2010), and what is perceived is that the guidelines and principles, although guiding the educational practice, do not ensure that their development occurs as prescribed or in a homogeneous way in the pedagogical work of the different professionals and cores that integrate the EJA of RME. Therefore, for a broader analysis of this educational reality, one must go beyond the guiding documents that systematize the methodological proposal, since there are other factors which are independent of conceptions (ways of hiring professionals, working conditions, etc.), but also the modeling that undergoes any curricular proposal.

Nunes (2008) sees the curriculum in the EJA of RME of Florianópolis as stemming from four action groups: 1. research for issues; 2. workshops, lectures, film sessions and videos; 3. work in non-classroom hours; 4. pedagogical outings, social gatherings, recreational and sporting moments. These actions are defined in two weekly meetings of collective planning between teachers and coordinators, of EJA Cores; students do not take part in these decisions. The author states that decision-making is conflictive because groups of interest are at stake: interests of students, interests of professionals, interests of the proposal of EJA, and interests of the current logic (capitalism, certification, individualism, market).

For Magalhães (2009), the dynamics of this daily practice occurs according to the needs perceived by the work group. There are cores that prioritize offering workshops; others develop the works relating them to pedagogical outings; others encourage students to seek in the community, individuals or entities that hold the knowledge about the subject that the student is researching. Thus, the curricular pedagogical practice is also a result of the “choices” made by the professionals about what they see as priorities, and also includes the “choices” of what receives priority as teaching. This cannot occur without negotiations and tensions, both between the professionals themselves and with the students who question, which means that the curricular policies in the context of practices are influenced by institutional questions of different orders. This means that “the teacher does not decide his action in a vacuum, but in the context of the reality of a workplace, inside an institution with operating standards sometimes marked by the administration, curricular policy, by the governing body of a school, or by the simple tradition that is accepted without discussing.” (SACRISTÀN, 1998, p. 167).

TEACHING AFRICAN AND AFRO-BRAZILIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE IN EJA: A DIDACTIC ACTION PROPOSAL

Kabengele Munanga, in the presentation of the book Superando o Racismo na Escola (2005), exposes the challenge of intervening in the formation of subjects so that they are educated to know and positivize the diversity of the Brazilian ethnic-racial composition, warning that this process also occurs in school. The school environment and its professionals can contribute for the Brazilian society to admit the unequal treatment provided to its citizens, since the phenotype still constitutes a factor of disparity, less opportunities and implies privileges to those with white or lighter skin tones, and to admit this inequality does not mean a change in the current society framework, demanding specific public policies and actions capable of transforming reality.

To question the school education and its relation to racial inequalities becomes a necessary way to construct school spaces that respect the differences of their subjects. For such, we needed to dialogue with authors who have been dedicating their time to reflect about other possibilities of education and teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian history and culture.

The school is a space to rethink the curriculum and change it within the demands and legislations in force in the field of education and, as a result, tensions unfold and take shape when discussing, or not, a stereotyped historiographic bias and still based in little motivating glances beyond the thematic of the slavery of the people of African origin. Thus, teachers need to know different approaches and historiographical readings, in addition to the awareness that the composition of Brazilian society still camouflages, through the entrenched myth of racial democracy,9 a cruel system of social differentiation with origins in the phenotype, even surpassing the question of social class, hierarchizing the society and the school as an institution that shelters people with different experiences.

The school composes a field of tensions and dissemination of a history based on Eurocentric values, unrelated to the diversity as an element of population wealth, in addition to hierarchizing it. In this sense, Tânia Muller and Wilma Coelho (2013, p. 9) state that

the school starts being conceived as a priority place for the formation of identities and the Governments as responsible for the continued formation of Teachers. In addition, this requires a strict and systematic relation between Federal, State and Municipal Governments, since the regulation expresses actions and, therefore, public policies, that must be followed by the Municipal and State Councils and by the Secretariats of Education for the implantation and the implementation of Law no. 10639/03, thus LDB.

Telles (2003) discusses the complex Brazilian social composition, concerning its social structured, marked by “skin issues”, indicating the school role in this process, pointing out that the inequality between white people and Afro-descendants in Brazil goes beyond material aspects, being present in the disparate relations of power. In this sense, Afro-descendants find difficult to fully participate in the social life when having a sense of inferiority, or actually being treated as inferior. Thus, civil and political rights, right to access to quality housing and healthcare, work and educational relations, these are all impaired by an educational system with two weights and two measures for white people and for Afro-descendants.

In these spaces, including school, racist and prejudiced manifestations occur, and many teachers and managers still argue for the non-necessity for debating and teaching African and Afro-Brazilian History and Culture, as well as the debate on ethnic-racial relations. To admit and to think of the school as white, Eurocentric, and established racism as the norm allows us to be able to propose alternatives to this system.

To think the school as white, western and colonialist requires the debate of the conceptualization of whiteness, the implications of such study and perspective of analysis for the school environment, as a non-isolated social space, but also reproductive of the social structures. When approaching this theme, Lourenço Cardoso (2008) defines whiteness as above all a space of privilege, since when removing their race, the white person assumes a normative role, free from being placed in the condition of oppressor in a racist society like the Brazilian is. By becoming invisible in the debate of race relations since not defining themselves in the racialized space, they end up placing all who are not equal in the condition of “other”, or “minority”, especially concerning the spaces of power and wealth.

The matrix of colonial power in epistemic racism is shown, a racism that “disregards and delegitimizes the epistemic capacity of certain groups, with the purpose, sometimes explicit sometimes veiled, to “avoid recognizing others as fully human beings” (MALDONADO-TORRES, 2009, p. 345). One must (un)teach and (re)teach, (un)learn and (re)learn everything that was imposed and presumed by colonization.

When the idea of a school as a whiteness space is approached, institutionally racist, we refer to a school that does not question the status quo, or which perpetuates these archetypes, and certainly any of the two possibilities configure choices, paths with pedagogical intentionality that directly affect the learning conditions of the subjects. In this sense, the black subject should be considered beyond the aspect and condition of oppressed in social and racial relations, thus avoiding making the problem into the sole responsibility of this ethnic group, since in every relation of power there is the oppressor, whose face can no longer remain anonymous, under a blanket of “universal”.

To consider teaching African and Afro-Brazilian History and Culture irrelevant, ignoring the responsibilities as educators, concerning the compliance with the legislation and, in moments of formation, not criticizing the normative documents and answering questions about ways to implement them, significantly contributes to perpetuate an education that does not problematizes society and does not instrumentalize it for effective social transformations.

The statements above become more evident as several studies show the difficulties faced by populations from African origin in Brazil throughout our history, such as the historian Willian Robson Soares Lucindo (2008), who mapped the educational experiences of Afro-descendants in the First Republic in São Paulo, finding non-school spaces with the purpose of schooling/literacy, since the schools paid by the State had the purpose of maintaining the subalternity conditions of the black population in relation to the white people, crystallizing through education hierarchies and distinctions of the slave period in Brazil. Thus, the author ponders that the “Brazilian education is characterized as alienating, producing hegemonic values, and fulfilling the role of training the several social roles, with no reflection on their historical construct” (LUCINDO, 2008, p. 26).

In the beginning, populations with African origin fought for the right to have access to school spaces constituted as school units. Currently, the fight concerns what is taught and how this process occurs. The most recent studies have not been able to change the grim diagnosis above described, especially when EJA is the subject.

In this perspective, the research carried out by Luciano Oliveira and Maria José de Resende Ferreira (2012) linking EJA and the ethnic-racial approach, in the city of Cariacica/State of Espírito Santo (ES), calls our attention for the need to consider the gears of the racial prejudice in Brazil which turn education into an active agent in excluding Afro-descendants. The authors consider the local EJA privileged for the analysis, since in this modality a large part of the public is black, paying attention to the need and use of strategies to fight racism. However, they emphasize that this marked presence of the population with African origin in EJA does not assure pedagogical planning and constant training focused in changing this conjuncture.

To think experiences for teaching History that comprehend a plural perspective of subjects is pivotal, to trace paths for didactic mediation based on ERER, exchanging knowledge and thinking over similar realities in geographically distant regions.

Corroborating this reasoning, Crislane Barbosa Azevedo (2011) emphasizes that the association between education of ethnic-racial relations and teaching History constitutes an awareness of the importance of Afro-Brazilians “in the construction of Brazil, to the extent that their own specific contents and knowledge related to their specificities will take place in school activities” (AZEVEDO, 2011, p. 175).

Based on the discussions presented above, we emphasize that we stand for a critical and decolonial perspective of the curriculum, considering Africa from the perspective of the African people themselves, talking of women by African female authors, show experiences of ex-captives by the movements in the Brazilian cities, conscious that this choice is not simple-minded, in the extend that the academic training received in our Eurocentric and colonized universities does not collaborate with this proposal, because it still has to a large extent male authors and authors of European origin talking about themselves and their place and about other peoples and continents.

A very complex Brazilian social equation is set up, having in the school a relevant variable. The debate over education of ethnic-racial relations mobilizes passions and places of speech that must be mediated by reading, mobilization of parallel concepts and availability, so that mainly the white population recognizes its social privileges arising from the phenotype, from the ideal of beauty and universality, and also to commit to an anti-racism position.

The challenge of another epistemology to face inequalities implies knowledge about the racism embedded in theories emerged as biological, currently manifested in a sociological way in a complex system, already discussed. The proposed challenge implies to widen teaching this theme beyond the subject of slavery, thus realizing the different experiences of these populations in their survival strategies forged daily, and which nowadays are also daily noticeable and should be known by all students in school, regardless of their ethnic-racial belonging. The school space requires us to think of knowledge in a non-hierarchical way, but as different ways, but not unequal, of seeing and experiencing the world.

In this way, thinking about school means paying attention to broader, extramural social configurations. Thus, mobilizing teacher and student knowledge, as well as both meeting in teaching History in EJA, is pivotal to construct a proposal of didactic action that contributes for a quality teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian History and Culture.

Crislane Barbosa Azevedo (2011) brings our attention to the need of considering how to articulate ERER and teaching of History in Basic Education. Mentioning aspects concerning EJA, she ponders about the ascending juvenilizing of the modality. The multiplicity of languages turns bodies into communication vehicles that would make traffic between different levels of literacy easier, and would provide learning experiences, a reference to civilizational values of African origin. Therefore, students about to dropout could be better received when valuing their knowledge, getting a sense of respect, and being encouraged to collectively build the knowledge and consider the school space as theirs.

A DIDACTIC ACTION PROPOSAL IN EJA

The research methodology that inspired the didactic action related in this paper was research-action, since it presupposes a social-political engaging and is configured with the involvement of researchers and study subjects. In this case, we refer to the pedagogical coordination of EJA core Center I Morning with the help of the teachers, in order to allow the students to know the reality in which they live, and through a liberating education they can get to know other historical trends about the populations with African origin.

The narrow knowledge of the students’ reality made possible by daily contact, along with studies and researches in development of pedagogical practices and constant updating of the Political Pedagogical Project of the core, made the elaboration of the action plan able to meet the aspirations arising from the research problems of these.

Throughout 2017, several questions of students’ research related to the existence of racism in the Brazilian society and about places and monuments in the city center of Florianópolis, with a few examples: How did the racial prejudice emerged? Why is there racism in Brazil? What are refugees? How was the bridge Hercílio Luz built? What is the history of the Public Market? (SANTOS, 2017). Aware to the needs of the subjects, the EJA allows for each core to be autonomous in developing their own pedagogical practices according to the public it serves, provided that it respects the research as an educational principle. The practice developed in the EJA Center Morning prioritizes the skills developed while reading and instigates students to critically think through activities such as daily initial reading, proposed each week by a teacher of a different knowledge area, with varied readings and once a week, a more extended directed activity that directly converses with students’ researches.

With the research questions, in a planning meeting of the pedagogical team, the coordinator proposed an initial reading of texts conversing with the questions here mentioned, so that they could be in contact with historical documents dating back to the 19th century and the presence of African people and their descendants in Desterro, previous name of Florianópolis, carrying out the most varied activities, as captives and freedmen. The proposal aimed at leading them to realize that such a period also had the presence of black people, and that they lived the everyday life of the city, in economic and cultural activities, in addition to breaking with the common place of Santa Catarina considered as an exclusively white State, and Florianópolis as an exclusively Azorean-originated city.10 There was also the goal of providing to students contact with primary historical sources and developing the potential of text interpretation and debate. The evaluation was focused in participation in debates and in the collectively written text in the research notebook, with the results of the interpretations from the group. This way, the conversation in the pedagogical staff made this joint activity possible, pointing out to the strict relation between investigating research questions with practice, to generate actions that could change reality.

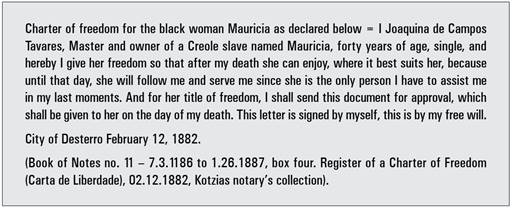

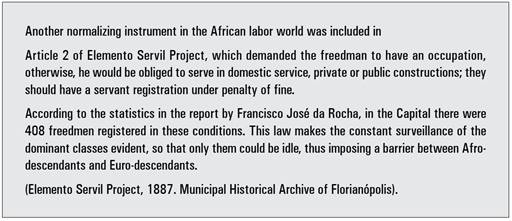

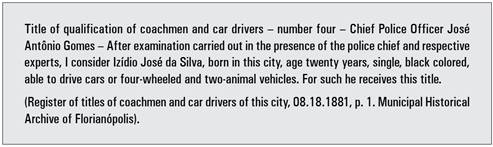

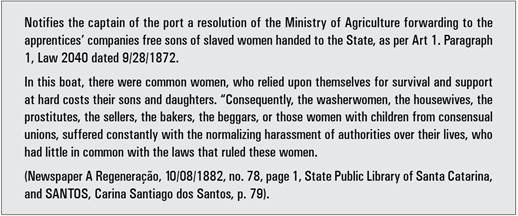

The documents used were extracted from Santos (2016), who noted, among other aspects, that the presence of African men and women and Afro-descendants in the neighborhoods performed routine functions in the city, and the street was their prominent place. The excerpts chosen included charter of freedom, contract of services, rules of conduct, regulation of the activity of coachmen, and the struggles and sufferings of Afro women:

The guidelines below were given to the students, so they could have contact with the excerpts of the documents:

Table 2 Guidelines to study the documents

| Study Guidelines |

|---|

| 1. Along with a colleague, read again carefully and analyze the above proposed documents from centers of documents of the city, such as registry offices and the Archive of Florianópolis. If you are not familiar with any word, take note so we talk in group. |

| 2. Document 1 registers a charter of freedom from 1882. What power relations can we notice in the text? When the woman mentioned in the text would have her freedom? |

| 3. Document 2 presents a standard of conduct of the time in debate. What would be the problem in allowing for freedmen to be idle? For which reasons did the police need to rule over the affairs of this group? What were the possible corrections given to those who did not comply with this rule? |

| 4. Document 3 presents a license to be coachman. Research what activity was this. How the recognition of a profession can influence a person’s life? |

| 5. Document 4 is a newspaper news, published in Desterro, year of 1882. It reports the notification that free children from slaved women were handed to the State. Discuss with your colleagues: what is the role of newspapers in dissemination of ideas of that time? What is place occupied by these Afro-descendants in the society at that time? Were their rights respected? Were they committing any crime? What is the current situation of black women in the Brazilian society? |

Source: Santos (2016)

The excerpts of the documents were presented in planning meeting so that all colleagues had contact with the material and could better guide the students in the classroom. On the day of the activity, the first reaction of the students was of astonishment for the presence of African people and Afro-descendants beyond the condition of enslaved in the city, performing so many diversified activities. This was important, so they do not disseminate the naturalization of the sole relation between a dark-skinned person and slavery, since this process dehumanizes and summarizes experiences and dreams of the enslaved subjects, in addition to negating the existence beyond this condition.

They could also be in contact with the struggles of African-originated women for their children not to be considered lazy and thus be forcefully recruited. The debate was articulated with contemporary questions of daily struggles of acquaintances and families of the students, and even police treatment of the youth from the periphery.

Initially, students presented some difficulty in reading texts with a language of the time in question, but after reading aloud by the teachers, the initial problems were overcome. It should be emphasized the use of primary sources in the classroom and the role of the teacher and/or researcher coordinator willing to articulate the research questions with differentiated shared actions from teachers and which provide students with differentiated learning experiences. Although small, this practice shows that it is possible to contribute with building a more egalitarian school concerning visibility of the cultural experiences and study of the pillars of African and Afro-Brazilian peoples. To know what multiple historical subjects have to say allows for us to grow as more respectful beings, avoiding idealized perspectives or an African essence.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The discussions presented in this paper aimed at questioning the challenges still posed, in the 21st century, for EJA, for the education of ethnic-racial relations and for the teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian History and Culture in curricula. Historical challenges that remain, despite the growing public debate about racism especially carried out by the black movements. After 15 years since passing, Law 10639 still does not have the institutionality level needed, in the academic curricula nor in the Basic Education curricula, including EJA. Although most of the time the pedagogical practices that contemplate it are carried out in an individual and militant effort, this paper presented a didactic action as a possibility for articulated conversation and planning in the routine of EJA.

In observing the difficulties pointed out by the teachers, in their mediations with the theme, and that these knowledges are constantly mobilized by students, by raising interests, we seek to dialogically build possibilities of activities and seek in literature the best understanding of this framework, contributing to broaden horizons and proposing qualified strategies for the timid discussions and insertions in the research questions oriented to the teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian History and Culture.

In our perspective, if the conception of EJA is guided by the right of youth and adults to education, the educational practice will experience at some level the effort towards the inclusion of other knowledges other than the hegemonic Eurocentric ones, in an attempt to overcome the epistemic hierarchy that makes the broadening of cultural repertoires and perspective of students, on the global reality, difficult.

We find support in NOGUERA (2014, p. 27), to whom “the colonization implied in the deconstruction of the social structure, reducing the knowledge of the colonized peoples to the category of beliefs or pseudo knowledge, always read from the Eurocentric perspective”. In this manner, we defend the discussion for the need to “restituting the speech and theorical and political production of subjects that have been so far considered destitute from the condition for speaking and the ability of producing theories and political projects” (BERNARDINO-COSTA; GROSFOGUEL, 2016, p. 21), in an attempt to question the place of education in the ethnic-racial relations and African and Afro-Brazilian history and culture as a perspective to understand the current society and the paths of subjects in EJA.

REFERENCES

ARROYO, M. G. Educação de Jovens e Adultos: um campo de direito e responsabilidade pública. In: SOARES, L. J. G.; GIOVANETTI, M. A.; GOMES, N. L. (org.). Diálogos na Educação de Jovens e Adultos. 4ª ed. São Paulo: Autêntica, 2011. [ Links ]

ARROYO, M. G. Formar educadoras e educadores de jovens e adultos. In: SOARES, L. Formação de Educadores de jovens e 292 adultos. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica; SECAD-MEC; UNESCO, 2006. [ Links ]

AZEVEDO, C. B. Educação para as Relações Étnico-Raciais e Ensino de História na Educação Básica. Saberes: Revista Interdisciplinar de Filosofia e Educação, Natal, RN, v. 2, n. esp., jun. 2011. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.periodicos.ufrn.br/saberes/index >. Acesso em: 06 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

BERNARDINO-COSTA, J.; GROSFOGUEL, R. Decolonialidade e perspectiva negra. Revista Sociedade e Estado. Brasília. v. 31, n. 1(jan./Abr), 2016. p. 15-24. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/se/v31n1/0102-6992-se-31-01-00015.pdf . Acesso em: 15 dez. 2017. [ Links ]

BERGER, D. G. Trajetórias Territoriais dos Jovens da EJA. 2009. 106 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC). Florianópolis. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/bitstream/handle/123456789/92852/269709.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y >. Acesso em: 05 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

BONETE, W. J. O ensino de História na concepção de alunos jovens e adultos: uma análise sobre objetivos e relações com a vida prática. Revista Historien. Petrolina, ano 4, n. 9., Jul/Dez 2013, p. 17-36. Disponível em <Disponível em http://www.revistahistorien.com.br >. Acesso em: 8 nov. 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Câmara dos Deputados. LDB: Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional: lei no 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados, Coordenação Edições Câmara, 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Documento Base Nacional Preparatório à VI Conferência Internacional de Educação de Adultos. Brasília: MEC; UNESCO, 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.forumeja.org.br/sc/files/docbrasil_0.pdf . Acesso em 12 dez. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Lei n° 10.639/03, de 09 de janeiro de 2003. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para incluir no currículo oficial da Rede de Ensino a obrigatoriedade da temática “História e Cultura Afro-Brasileira”. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.planalto. gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2003/L10.639.htm >. Acesso em: 27 fev. 2015. [ Links ]

CAVALLEIRO, E. Do silêncio do lar ao silêncio escolar: racismo, preconceito e discriminação na educação infantil. São Paulo. Editora Contexto, 2000. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, L. O branco “invisível”: um estudo sobre a emergência da branquitude nas pesquisas sobre as relações raciais no Brasil (Período: 1957-2007). Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências Sociais) - Faculdade de Economia e Centro de Estudos Sociais da Universidade de Coimbra Coimbra, 2008. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, F. A.; VALENTIM, S. dos S. Práticas Pedagógicas na EJA: Caminhos afirmativos na construção/ação de uma pedagogia multirracial. In: IVSeminário Nacional de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica - SENEPT, 2014, Belo Horizonte. Anais do IV SENEPT - 2014. [ Links ]

CME. Conselho Municipal de Educação de Florianópolis. Resolução n. 01, de 17 de dezembro de 2008. Florianópolis, 2008. [ Links ]

CME. Conselho Municipal de Educação de Florianópolis. Resolução n. 02, de 27 de dezembro de 2010. Florianópolis, 2010. [ Links ]

DURAND, O. C. da S. Formas associativas juvenis: o caso dos jovens da ilha de Santa Catarina. In: Reunião Anual da Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Educação, 24., 2011, Caxambu. Anais... Caxambu, MG: Anped, 2011. [ Links ]

FANNON, F. Os condenados da terra. Trad. Enilde Albergaria Rocha, Lucy Magalhães. Juiz de Fora: UFJF, 2006. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P.; FAUNDEZ, A. Por uma pedagogia da pergunta. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1986. [ Links ]

GOMES, N. L. Educação de Jovens e Adultos e questão racial: algumas reflexões iniciais. In: SOARES, L. J. G.; GIOVANETTI, M. A.; GOMES, N. L. (org.). Diálogos na Educação de Jovens e Adultos. 4ª ed. São Paulo: Autêntica, 2011. [ Links ]

GOMES, N. L. Relações Étnico-Raciais, Educação e Descolonização dos Currículos. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 12, p. 98-109, 2012. [ Links ]

GOMES, N. L. Currículo, corpo e identidade. In: II Congresso Nacional de Reorientação Curricular, 2000, Blumenau. Anais. Blumenau: Secretaria Municipal de Educação. p. 20-20. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, Antônio Sérgio Alfredo. Depois da democracia racial. Revista Tempo Social: Revista de Sociologia da USP, v. 18, n. 2, p. 269-287, 2006. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ts/v18n2/a14v18n2.pdf >. Acesso em: 27 nov. 2015. [ Links ]

HASENBALG, C. A. Discriminação e desigualdades raciais no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Graal, 1979. [ Links ]

HENRIQUES, R. Desigualdade Racial no Brasil: evolução das condições de vida na década de 90. Texto para discussão n. 807. Brasília: IPEA, 2001. Disponível em Disponível em http://www.ipea.gov.br . Acesso em 12 dez. 2017. [ Links ]

LUCINDO, W. R. S. A educação no processo abolicionista. Linhas, Florianópolis, v. 9, n. 1, p. 146-148, jan./jun. 2008. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.periodicos.udesc.br/index.php/linhas/article/viewFile/1398/1195 >. Acesso em: 20 maio. 2016. [ Links ]

MACHADO, M. M. A Educação de Jovens e Adultos no Brasil pós Lei 9394/96: a possibilidade de constituir-se como política pública. Em Aberto. Brasília: INEP, v.22, n. 82, p.17-39; nov. 2009. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, M. G. Jovens egressos da Educação de Jovens e Adultos. (Dissertação de Mestrado). PPGE/UFSC, 2009. [ Links ]

MALDONADO-TORRES, N. A topologia do ser e a geopolítica do conhecimento. Modernidade, império e decolonialidade. In: SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa; MENESES, Maria Paula (org.). Epistemologias do Sul. Coimbra -Portugal: Almedina, p. 337-382, 2009. [ Links ]

MULLER, T.; COELHO, W. A Lei n. 10.639/03 e a formação de professores: trajetórias e perspectivas. Revista da ABPN, v. 5, n. 11, p. 29-54, Jul./Out., 2013. [ Links ]

MUNANGA, K. (org.). Superando o racismo na escola. Brasília: Ministério da Educação, Secretaria de Educação Fundamental, 2005. [ Links ]

NOGUERA, R . O ensino de filosofia e a Lei 10639. Rio de Janeiro.: Pallas: Biblioteca Nacional, 2014. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, N. A. da S.; SILVA, L. N. Os desafios para a construção de uma história local - o caso de Leopoldina, Zona da Mata de Minas Gerais. Revista Polyphonía, v. 21, n. 1, p. 229-242, jan./jun. 2010. [ Links ]

NUNES, J. M. Currículo emergente e interesse dos alunos: os focos das pesquisas na Educação de Jovens e Adultos da Rede Municipal de Florianópolis, no período de 2001 a 2007. In: CD-Rom Anaisdo IVColóquio Luso-Brasileiro sobre questões curriculares, Florianópolis: UFSC: CED; NUP, 2008. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, L.; FERREIRA, M. J. de R. A questão étnico-racial e a Educação de Jovens e Adultos. Debates em Educação Científica e Tecnológica, v. 2, n. 2, p. 77-86, 2012. [ Links ]

OXFAM. A distância que nos une - Um retrato das Desigualdades Brasileiras”. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oxfam.org.br/sites/default/files/arquivos/Relatorio_A_distancia_que_nos_une.pdf Acesso em 10 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

PASSOS, J. C. Juventude negra na EJA: os desafios de uma política pública. Florianópolis: PPGE:UFSC (Tese de Doutorado), 2010. [ Links ]

PASSOS, J. C. As desigualdades na escolarização da população negra e a Educação de Jovens e Adultos. Revista em Debate. Florianópolis, v. 1, n. 1, p. 137-158, 2012. [ Links ]

PASSOS, J. C As relações étnico-raciais nas licenciaturas: o que dizem os currículos anunciados. Tubarão. Poiésis, (Unisul), v. 8, p. 179-196, 2014. [ Links ]

SANTOS, C. S. Um lugar chamado Figueira: experiências de africanos e afrodescendentes nas duas últimas décadas do século XIX. Florianópolis, 2005. TCC. (Graduação em História) - Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis. [ Links ]

SANTOS, C. S. A Educação das Relações Étnico-Raciais e o ensino de História na Educação de Jovens e Adultos da Rede Municipal de Florianópolis (2010 - 2015). 2016. 131 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ensino de História) - Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis. [ Links ]

SACRISTÁN, J.G. O currículo: uma reflexão sobre a prática. 3 ed.Porto Alegre, Artmed, 1998. (Trad. Ernani F da Rosa) [ Links ]

SILVA, P. B. G. e. História e Cultura Africana no Ensino Brasileiro e na Formação para Cidadania. In: BOLOMA, N. A. (org.). Redes de conhecimentos: Novos Horizontes para Cooperação do Brasil e África. 1ª ed.São Carlos: Pedro e João Editores, v. 1, p. 103-112, 2007. [ Links ]

SILVA, P. B. G. e. Pesquisa e luta por reconhecimento e cidadania. In: ABRAMOWICZ, A.; SILBÉRIO, V. R. (org.). Afirmando diferenças: Montando o quebra-cabeça da diversidade na escola. 1ed.Campinas: Papirus, 2005, v. 1, p. 27-53. [ Links ]

SILVA, P. B. G. e. Projeto Nacional de Educação na Perspectiva dos Negros Brasileiros. In: UNESCO; Conselho Nacional de Educação; Ministério da Educação. (org.). Conferências do Fórum Brasil de Educação. Brasília: UNESCO Brasil, v.1 , p. 385-395, 2004. [ Links ]

SOARES, L. J. G. As políticas de EJA e as necessidades de aprendizagem dos jovens e adultos. In: RIBEIRO, V. M. (org.). Educação de Jovens e Adultos: novos leitores, novas leituras. Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras: Associação de Leitura do Brasil: Ação Educativa, 2001. [ Links ]

SME. Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Florianópolis. Departamento da Educação de Jovens e Adultos. Diretrizes para a EJA. Florianópolis, 2012. [ Links ]

TELLES, E. E. Racismo à brasileira: uma nova perspectiva sociológica. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Ford, 2003. [ Links ]

THIOLLENT, M. Metodologia da pesquisa-ação. São Paulo: Cortez,1985. [ Links ]

ZABALA, A. A função social do ensino e a concepção sobre os processos de aprendizagem: instrumentos de análise. In: ZABALA, A. A Prática Educativa: como ensinar. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1998. [ Links ]

1According to IBGE, black people (black and brown) were the majority of the Brazilian population in 2014, accounting for 53.6% of the population. Brazilian individuals self-declared as white accounted for 45.5%. (IBGE/PNAD, 2014)

2At the moment this paper is written, Brazil is in another dark period of its history, a coup d’état (joint action by parliament, judiciary and economic power) is under way, which already shows signs of worsening racial inequalities, especially with the military intervention that has prioritized the peripheral places of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

3Although we understand that EJA is not limited to the schooling spaces, this paper focuses in the school pedagogical practices.

4Arroyo (2006, 2011), Gomes (2005, 2012), Soares (2005), Machado (2009), Passos (2010, 2012), among others.

5The EJA Forums are spaces for dialogue, proposition and social control of youth and adult education policies, civil society, educators, learners and universities. They also work in the continuing education of educators and managers, carrying out the Regional Meetings of EJA (EREJAs) and the National Meeting of EJA (ENEJA) on a biennial basis. Regarding racial issues in the EJA see mainly the Reports of ENEJAS 2005 and 2006 analysed by Passos (2010).

6The EJA in the RME of Florianópolis started in the year of 1970, in a partnership with the State government and the Foundation MOBRAL. The objective was to serve people above 12 years in groups of literacy. Previously, initiatives of education for adults were carried out in the format of punctual actions, in conventions with the Brazilian Legion of Presence (LBA), the Municipal Commission of the MOBRAL and the City Town Hall (PASSOS, 2010).

8In addition, it was found that the RME data storage system has an inadequate management mechanism for EJA registrations, since it was created only for students attended by Elementary School and below legal majority. One example can be seen when the student’s data is inserted in the system and it is not possible to advance without adding the name of a person responsible for the student, disregarding the public with over 18 years of age, thus, able to represent themselves. These gaps make data collection and quantitative and qualitative studies on EJA difficult, as well as subsequent analysis.

9According to Antônio Sérgio Alfredo Guimarães (2006), the racial democracy is the belief that Brazil was originated through the mix of three people - white, Afro-descendants and indigenous, and that they live harmonically, with no prejudice or hierarchy of cultures and social spaces of functioning.

10In the 2010 Census (IBGE, 2010), Santa Catarina had a black population of 960 thousand people, which was the country’s lowest black population. The publicity materials produced by the State Department of Tourism of Santa Catarina - Santur translate this imagery of a white state, configuring the “Brazilian Europe” and thus negating populations with other origins, especially African and indigenous origin in the state.

Received: February 27, 2018; Accepted: June 16, 2018

texto em

texto em