Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.35 Belo Horizonte jan./dez 2019 Epub 26-Jul-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698204207

ARTICLE

GIRLS AND MARRIAGEABLE YOUNG WOMEN ON THE STAGES OF SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI, MG: EDUCATION OF THE SENSIBILITIES IN THEATER PERFORMANCES OF THE CLUB DRAMÁTICO ARTHUR AZEVEDO (1915-1916)1

IFederal Rural University of Pernambuco, Garanhuns Academic Unit, Pernambuco, Brazil.

II Federal University of Minas Gerais, Faculty of Education, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

ABSTRACT: In São João del Rei / MG, between 1915 and 1916, girls and women, local elites daughters, acted in the performances of an amateur theater group, although the presence of women on stage was not favorably seen by most people belonging to these social groups. In order to understand the education of sensibilities that occurred during these presentations, we analyze the motivations of the amateur group in choosing the operettas presented and distributing the roles to the actors. The sources used were newspaper clippings, concert programs, operetta manuscripts, and books that belonged to the Clube Teatral Arthur Azevedo and to the amateur Antonio Guerra. We observed that girls and marriageable young women showed their skills during the performances, which can be understood as an extension of school and salons. They reinforced hegemonic sensibilities, ways of qualifying the world, to understand and experience gender relations.

Key Words : History of Education of the sensitivities; Gender; history of spectacles

Em São João del-Rei/MG, entre 1915 e 1916, meninas e moças, filhas das elites locais, atuaram nas apresentações de um grupo de teatro amador, apesar de a presença das mulheres nos palcos não ser vista com bons olhos por grande parte das pessoas pertencentes a esses grupos sociais. Com o objetivo de compreender a educação das sensibilidades que se deu durante essas apresentações, analisamos as motivações do grupo amador ao escolher as operetas apresentadas e ao distribuir os papéis às amadoras e aos amadores. As fontes utilizadas foram recortes de jornais, programas de espetáculos, manuscritos de operetas, livros que pertenceram ao Clube Teatral Arthur Azevedo e ao amador Antônio Guerra. Observamos que as meninas e moças casadouras exibiam seus dotes durante as apresentações, que se configuravam como uma extensão da escola e dos salões. Reforçavam-se sensibilidades hegemônicas, maneiras de qualificar o mundo, de compreender e de experimentar as relações de gênero.

Palavras-chave: História da Educação das Sensibilidades; Gênero; História dos Espetáculos

Between the years of 1915 and 1916, in São João del-Rei, MG, an amateur theatre group led by the local elite men, senior military, men of letters and of the government, in addition to a few connoisseurs of dramatic art, conducted performances that were covered in the town newspapers. Girls and young women, daughters of the local elite, performed at the Municipal Theatre, staging operettas which, although criticized by the literati of the period, were applauded in cities such as Paris, London, Rio de Janeiro and São João del-Rei.

In order to investigate the education of the sensibilities that took place during the presentations of the most popular operettas in the period - O Periquito (The Parakeet) and A mulher soldado (The Soldier Woman) - performed by Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, we analyzed the motivations that led club members to choose and perform such texts, as well as the reasons for the public to go to the theater. This analysis has provided evidence of the set of hegemonic and collective sensibilities of that social group. These data have enabled a closer look at what would have been the feelings and sensibilities produced or provoked during such shows.

Although interest in the theme of senses and sensibilities is not something new, according to Oliveira (2018), among historians,2 the author points out that, in the last 20 years, the History of Education has experienced “a change in direction towards the senses and sensibilities”. This has been led “by the renewing of studies on the History of Education and its intense proximity to the field of History in Latin America” (OLIVEIRA, 2018, p. 120). This work falls within the set of studies that, according to Oliveira (2018), recognizing the limits of the stories of general character, tries to understand the materiality of life, the answers that people give to different situations experienced in spite of any rationality. It also aims to identify, in addition to the discourses, how one responded to them, namely “to understand the emotional responses of different individuals to social imperatives” (OLIVEIRA, 2018, p. 121).3

To do so, we were inspired by the definition of sensibility coined by Sandra Pesavento (2007). According to the author, sensibilities are the “imaginary operations of sense and representation of the world, which can make an absence present and can produce, by the power of thought, a sensitive experience of the event” (PESAVENTO, 2007, p. 14-15). In order to understand the education of sensibilities at a particular historic moment, it was necessary to understand in which sensibilities the producers of the shows and the public were immersed, distinguishing the hegemonic sensibilities from the collective and the individual ones. We define the individual sensitivities as those imaginary operations of sense and representation of the world, originating from the unique experiences of the subjects; we define the collective sensitivities as imaginary operations of sense and representation of the world related to common experiences lived by distinct social groups; and, we define the hegemonic sensibilities as imaginary operations of sense and representation of the world that dominant groups aim to impose on other social subjects.

Paul Zumthor’s (2007) definition of performance contributed to adjusting the lens of analysis for theatrical performances as educational phenomena. As stated by Zumthor, performance is the situation in which poetry occurs, where the listener and the performer are physically present, a “full presence, loaded with sensory powers, simultaneously, on a vigil” (ZUMTHOR, 2007, p. 68). The author adds that this presence not only communicates, but modifies and marks the knowledge transmitted. From this definition, we can say that performance is an educational phenomenon in which listeners and performers, interacting with each other at the same time that they perform, constitute a poetic.

Zumthor’s study (2007) also corroborated some methodological choices. The poetic that is constituted during the performance is an indication of sensibilities taught and learned during theatrical shows and, therefore, is the subject of analysis of this study. According to Zumthor (2007), a poetic text is one that produces effects of pleasure; therefore, the study of the poetics of setting, that is, the elements that pleased the public in São João del-Rei, allowed analysis of the education of the sensibilities. These reflections led to the selection of the most successful theatrical performances of the group studied, in addition to the analysis, in the reviews published about them in town newspapers, of the elements that pleased the public, seen as evidence of the phenomenon studied.

The main set of sources used for this study is kept by the Research Group in Performing Arts at the Federal University of São João del-Rei. The collection consists of two sets: the first belonged to the Clube Teatral Arthur Azevedo, an association of amateurs of the town which would have performed from 1905 until 1985; the second is the private collection of Antonio Guerra, an amateur actor from São João del-Rei. Among the sources, we used some of the albums made by the amateur, comprising newspaper clippings, show programs, flyers and photographs of Clube productions, in addition to the union statutes and some publications of the period that constituted the dramatic society library. The book written by Antonio Guerra, published in 1968, was also central to this investigation.

São João del-Rei, at the turn from the 19th to the 20th centuries, went through intense transformations at all levels of social experience. According to Guilarduci (2009), in 1881, the opening of the Oeste de Minas railroad brought the town closer to the capital of the Empire and, consequently, to Europe. Innovations such as electric lighting, the telegraph, the installation of several typography factories, photography workshops and a very active and diverse press, changed life in the town. The times and spaces of work, leisure and conviviality were also changing, in addition to the traditional religiosity: in addition to the Catholic cults and traditional religious festivals,4 in São João del-Rei there were several spaces of sociability and various forms of leisure.5

The Constitution of the Republic opened new ways to deal with space and with public power, new ways of thinking appeared regarding the nation and relations with other countries. The elites of the city wanted novelties, and sought to distinguish themselves by investing in artistic activities, such as the theater. The members of the board of directors of the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo were wealthy military, intellectuals and government men, occupying positions of power in the são-joanense society. However, among the union members, there were those who did not have many assets, prestige and were not distinguished by their artistic skills.6 In this new and changing environment, amateurs wished to present “world class”7 plays that demanded financial resources to invest in scenarios, elaborate costumes and competent amateurs who knew the secrets of the art.

Garraio (1911)8 stated that any group of amateurs should be very careful in choosing the plays to be performed. For the Portuguese acting coach, a common mistake among amateurs was to choose famous plays, led by the desire to play a certain role, without considering the show as a whole. The result, in these cases, was the failure of the performance, since a single role, although well played, couldn’t save a play.

The choice of a play, in a company of amateurs, is thus a very difficult task, but it can be carried out successfully, putting aside the desire of the performers to shine on their own, to be applauded together. (...) A mediocre performance, but well-tuned, said a critic, pleases us more than seeing a leading artist play a scene with the aid of nullities (GARRAIO, 1911, p. 6).

The statutes of the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo defined that the “stage director” would be responsible for choosing the plays to be staged by the association, and would rehearse them. He was responsible for keeping “unharmed the principle of his authority in the theater box, watching carefully to maintain the order, respect and discipline of all amateurs, being at the same time accountable for the artistic results of the shows.”9 These rules tell us that there was a need for a person skilled in dramatic arts and able to watch over the order. That is, someone who could deal with the desires of amateurs and fine-tune the group according to individual skills, and be responsible for the artistic results of the plays. Alberto Gomes, an actor who enjoyed prestige with the public of São João del-Rei for his performances on the stages of the town, was the stage director of the Club and certainly needed to take into account all these elements, along with the interests of the directors of the dramatic association, to reach his decisions.

The choice of Alberto Gomes10 to stage the operettas is related to a historical context in which light plays and musical plays11 had great success in Rio de Janeiro and in some Brazilian cities, in addition to being suitable for a theatrical group called Arthur Azevedo, named after the renowned man of letters of the Brazilian society of the time, writer and advocate of light plays.12 Judging by the success of the two operettas analyzed, we believe that Alberto Gomes chose the plays well, considering the elements that the association had, its abilities and the requirements demanded by the chosen plays. The similarities between them are also justified by the need to match them to the amateur group profile. It was common in Brazil, at the turn of the 19th to the 20th centuries, that actors and actresses dedicated themselves to play a specific type of character. This facilitated the staging of a variety of plays by the same troupe in a short space of time. In addition, according to Pavis (2011), some playwrights, like those of farce and comedies of characters, could not deprive themselves of the types. For Neyde Veneziano (1991, p. 120-121), “all the popular theatre, and in particular the revues, work mainly with types”. The type, or character-type, is the

conventional character that has common physical, physiological or moral characteristics known beforehand by the public and that remain constant throughout the play: these characteristics were set by the literary tradition (the good-hearted outlaw, the good prostitute, the buck and all characters of Commedia dell’arte. (PAVIS, 2011, p. 410)

The roles were generally assigned to actors and actresses according to emploi.13 That is, each artist would be assigned a role that matched their body type, voice, personality and style of interpretation.

Garraio recommended that, given the “scenic requirements”, amateurs should look for “hoods for our people. Not everyone can play every role is the maxim that all dramatic amateurs must keep in mind” (GARRAIO, 1911, p. 7, emphasis added). The acting coach had to consider the voice, age and height of each interpreter according to the requirements of the play. The physical characteristics of the amateurs should match the features of the characters that they would represent on stage. Therefore, a “natural performance” could be ensured.

Naturalness in a performance is a valued talent for any artist, it also requires propriety in the place of action and all the accessories that are needed to complete it. The eye delights in the resemblance of reality, as well as the ears, and it is to satisfy viewers of more refined taste that we will seek to introduce a play with all the local color and truth, in the style of the time. (Emphasis added) (GARRAIO, 1911, p. 8)

Amateurs should feel familiar with the place of the action, with the accessories on the scene, to satisfy the public who wished to see a setting similar to reality.

The operetta O Periquito tells the story of a young man who was raised as a girl and his strangeness and transformations in making contact with the world outside the walls of the convent in which he lived, under the care of nuns and his aunt, the Abbess. The operetta A Mulher Soldado tells of the tensions and confusions experienced by a lady, the wife of a soldier who, in order to avenge her husband’s betrayal, decides to disguise herself as a soldier and serve in the barracks where he was a sergeant.14 The main character types of the two operettas were the same:

. The transvestite, the kind of characters played by the amateur Margarida Pimentel: the Periquito of the operetta of the same name and Clarinha disguised as Ventura of the operetta A Mulher Soldado.

. The stupid peasant, similar to the type described by Garraio as the “criado-lorpa” (moron-servant) (1911, p. 52), played by the amateur Francisco Velloso: Liborio of the operetta O Periquito and Thomé of A Mulher Soldado.

. The seductive soldier, similar to the heartthrob in the Garraio (1911, p. 30) classification, played by the amateur Alberto Gomes: Captain Carlos of O Periquito, and Sergeant Villar of A Mulher Soldado.

We observed that the acting coach Alberto Gomes was able, in order to meet “the scene requirements”, to find “hoods” for some amateurs (GARRAIO, 1911, p. 7), at least for the main roles of the operettas. In relation to the amateur group as a whole, we need to ask ourselves: what would have been the group characteristics that corresponded to those necessary for the staging of the operettas selected?

Initially, we observed that the number of actors and actresses needed was important in selecting the plays. The operetta O Periquito, in the way it was staged in São João del-Rei,15 was composed of eleven male16 and six female17 characters, staged by ten amateur actors18 and six amateur actresses.19 The operetta A Mulher Soldado had eight male20 and four female21 characters, played by amateurs: eight amateur actors22 and four amateur actresses.23

The Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo counted on a good number of amateurs, making it possible to stage operettas, but few women were willing (or did not dare) to act on the stages of São João del-Rei. Although some literati argued that there were virtuous women in the theater, possibly the image of the actress, linked to that of the prostitute,24 prevented the actresses of São João del-Rei to act in the plays, even in an amateur group consisting of the “honorable” families of the town elites. However, girls and young unmarried women were present on stage, as we will see below. The belief that the exposure and the public space were inappropriate for women, and the notion that they should take care of the education of their children and do the household chores, can explain the absence of ladies in the plays.25

At the conference held by the poet Franklin Magalhães, in gratitude for the homage paid by another amateur group from São João del-Rei, the Club D. 15 de Novembro, on the evening of 1 October, 1914, the issues involved when a young girl who was engaged, about to be married, performed on the stage of São João del-Rei became evident. At some point in his speech, the poet thanks the “dazzling presence” of the “fair sex” in the show:

(...) Poet- how weak is my estrus! How the pace and cadence of my verses are powerless to express all the harmony that I feel inside me now and chant verses worthy of you.

But I say in gibberish verses:

- My soul isn’t mine,

It belongs to the fair sex

of São Jõao-del-Rei.

***

(...)

I do not forget, gentlemen;

Every day I remember

Of the members and directors

of this ‘November 15’.

The Muse, in a nice demeanor

Full of glory and joy,

Shows her gratitude to Carmen Mello,

Marcondes and Velloso.

Let the bride and groom not be jealous;

flirtatious muse come;

And courteously address Carmen

Expressing thanks to Pereira.

And of life in the desert,

In the chest like a nest,

I keep the tribute of Alberto,

Annita and of Passarinho!

But, if I hold them in great esteem,

More grateful my soul feels

For the great tributes,

Nico Guerra bestows upon me.

(Flyer of November 13 1914, pasted in the album 1, p. 28)

The poet defined the appropriate place for women in the theater: in the audience and not on the stage. After thanking the people of São João del-Rei who were watching the show, saying that he felt “all bathed and illuminated” by the smiles and gazes of his women compatriots, “with his soul in a sea of happiness” under the influence of the gracefulness, charm and seduction of those women from the audience, Franklin Magalhães thanks the homage of the theatrical group, on behalf of his poetic soul, a muse inspired by the amateurs. The soul of the poet, “muse full of glory and pleasure”, “flirtatious muse”, asked permission of the amateur Carmen Mello to address Pereira, her fiancé. Magalhães was ironic, flipping the dominant social hierarchy that attributed to men the role of guardian of women. Making the audience laugh, the poet reduced Carmen’s fiancé, implying that, in the relationship of the young couple, the social roles were inverted. At the same time, the poet, as if to repair the offense, thanked Pereira, probably for having allowed that Carmen, his fiancée, had acted that evening in his honor.

This episode indicates the unease that the presence on stage, of a fiancée or wife, could cause in their fiancés or husbands. Carmen, as well as Franklin Magalhães, were bathed and lit by the smiles and gazes from the audience that was also masculine. If this were already a reason for jealousy, and made grooms and husbands lose sleep, how would it be if they could imagine the possibility of their women feeling happy, under the influence of the gracefulness, charm and seduction of the men in the audience?

Carmen Mello and Nathalia Costa comprised the set of girls and young, unmarried women of the elite who acted as amateurs of the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo. Belonging to a generation who were used to acting from a very young age in the amateur theatrical groups of the city, it is possible that these “ladies” continued staging plays while they were under the care of their parents. It is possible that marriage would mark their departure from the stage.

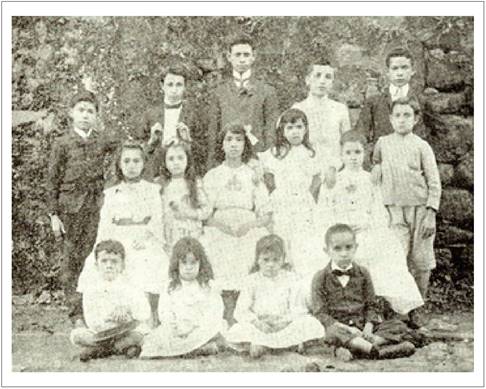

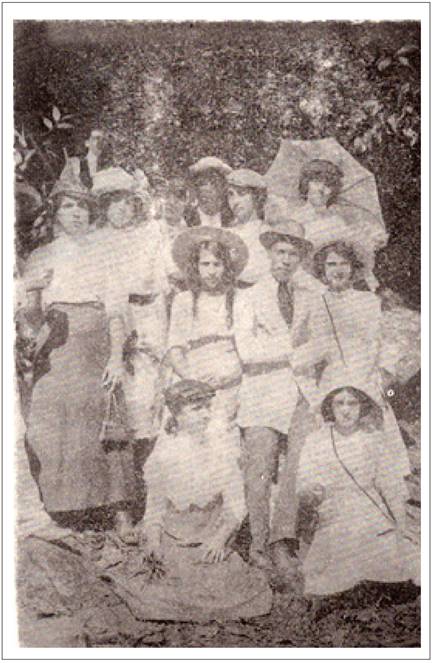

Figure 1, a photo taken from the book of Guerra (1968, p. 101), depicts the Grupo Dramático Infantil 15 de Novembro (November 15 Children’s Drama Group) on 24 June, 1906. At that time, Guerra, the first boy standing on the left, was between 13 and 14 years old. Carmen Mello, the first girl to the left in the middle row, seemed to be 10 to 12 years old. Figure 2, also taken from the book of Guerra (1968, p. 125), shows a “group of amateurs” in 1912. The boy, who is more in evidence, is Antonio Guerra at the age of 20. According to the author, Nathalia Costa would be the girl at his right, with long hair, and Carmen Mello would be the last one kneeling to his left. The two seemed to be almost the same age, possibly between 16 and 18 years. From these images, we assume that on the occasion of the presentation of the operetta O Periquito, Nathalia and Carmen were around 20 to 22 years old.

Figure 1 shows that, in the 15 de Novembro children’s group, in 1906, the number of boys and girls was balanced. However, the 1912 photo shows a group composed mostly of young ladies.

We have no information about married women who acted as amateurs in the Arthur Azevedo club (1915-1916). However, girls and young, single women vied for the limelight. They sang, danced and/or acted. The Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, in staging the operetta O Periquito, in addition to the amateur actors and actresses who performed the main roles, counted on the participation of six girls who made up the “chorus of the convent students”: Cecilia Costa, Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, Nenê Pimentel, Diquinha and Lucilia Ribeiro, and Hilda Miranda.

The editor of the newspaper O Zuavo referred to the girls as follows: “Six cute faces played these roles. We were so jealous of Liborio!!!”28 The exclamation of the writer (with the intensity of three exclamation points) intrigues us, as it exposes, without any discomfort, the desire to be surrounded by “cute faces”, that is, to be surrounded by the girls, the daughters of the prestigious families of which he wrote. What was that desire, supposedly shared by the men who attended the operetta (the author used the first-person plural)?

According to Silvia Favero Arend (2013), during the 19th century, marriages were made for convenience and girls who had just entered puberty, sometimes even before that, were married to older men. However, at the turn of the century there was a notion of an ideal age for marriage, around 20 years, at which time the body of the woman would be more prepared to raise children.29 Nevertheless, we can assume that, even though the requirements had changed, the sensibilities were still in the process of transformation. Further, the editor of O Zuavo exposed the desire of some of the men in the audience that would derive huge pleasure from being surrounded by beautiful, marriageable girls, who were or would be soon, ready/prepared for marriage. Men, therefore, saw those girls as “good wives” in preparation.

An important piece of information that should be taken into account is the roles and functions that such girls played in the shows. In the case of the operetta O Periquito, as we have already said, the girls composed the choir of convent students. Therefore, on stage, the girls were possibly representing themselves, or what the parents and sao-joanense society wanted them to be, and they were, thus, raised to achieve this ideal. By 1916, the Colégio Nossa Senhora das Dores had been in São João del-Rei for 18 years, and it aimed exclusively at the education of girls and women. As stated by Maria Aparecida Arruda (2011), the institution functioned as a boarding, semi-boarding, and day-school, and offered primary education, junior high, high school and the Teacher training course.30 It is possible that some of the girls, who sang in the operetta choir, studied or had finished their studies at the school. The research that originated this article could not find documentary evidence about the amateurs’ attendance at the Colégio Nossa Senhora das Dores. However, even if none of them had attended the school, it can be argued that the way they were seen and saw themselves, acting on the stage of a convent students’ choir, was produced by hegemonic and collective sensibilities.

The são-joanense elite, as well as the Brazilian elite from other cities, sought an education for their daughters similar to the “European female model of civilized women, in that the knowledge of literate culture was one of the signs of civility” (GOUVEIA, 2004, p. 198). In addition, they desired what Maria Cristina Soares de Gouveia calls “an education for the exercise of urban sociability, a feature of the dominant classes” (2004, p. 198). Colégio Nossa Senhora das Dores addressed some concerns of these families offering, according to Arruda (2011), extracurricular courses such as painting, flowers, needlework, embroidery, music, singing, piano and violin classes, at an additional cost.31

The shows organized by amateurs were seen as an extension of the school and the salons. These were occasions for the local elite to present their daughters (girls and marriageable young women) to society. In this way, these “honored” families exhibited, on stage, the education they were able to offer their daughters, recognized through the girls’ ability to sing, dance, behave properly, and in the careful and luxurious way they dressed. The families also exhibited their purchasing power and distinguished themselves according to the skills displayed by the amateurs, because only the families that could pay for the extra courses offered by the school had access to the teaching of some of these skills (such as singing), or for private classes that, we assume, were given by the town’s teachers, such as Balbininha Santhiago.32

The confession of the editor of O Zuavo about his desire to be in Liborio’s place, surrounded by those girls, could be taken as a compliment to the girls and their parents, as it attested to the success of the education offered to them, which resulted in raising “beautiful girls” who were, or would be, ready to be good mothers and wives. The editor’s comment, as well as the applause of the audience, welcoming the show presented by the girls, made the mothers and fathers, who were certainly seated in the audience, proud.

However, in the two operettas studied, not all the amateurs of the Arthur Azevedo club presented themselves as students. In 1916, Nathalia Costa and Carmen Mello played the parts of actresses at the São João del-Rei theatre. For the inauguration of the club, the former played the role of the actress Tosca, in Vitorien Sardou’s play, and she played both the student Branca and the actress Amelia in O Periquito. Carmen Mello replaced Nathalia in June, 1916 (at the sixth performance of the operetta), playing both Amelia and Branca. Had Nathalia got married? The question remains. Acting on the stages of São João del-Rei was not something simple for women, but it became even more complicated when they played actresses, as they would embody the characteristics of free and seductive women that the collective imaginary associated with actresses.

On July 13th, 1916, the O Theatro newspaper recorded the entry of the amateur actress Carmen in the Arthur Azevedo amateur troupe. According to the editor,

in the show performed by the Arthur Azevedo troupe for the benefit of the Portuguese Red Cross, those who came to watch this delightful artistic feast saw how much life Miss Carmen Mello breathed into the role of the Actress, a role that, as a courtesy to the Portuguese colony, she agreed to interpret (…). (O Theatro, nº 8, 13 July, 1916. Album 13, p. 28).

In 1916, Carmen was still considered a daring “Miss”, willing to play roles that very few women from the São João del-Rei elite would play. The news reproduced above is good evidence of this, in which the editor justified the young lady’s boldness by characterizing her behaviour as charitable, a “courtesy to the Portuguese colony”.

In March of that year, Germany had declared war on Portugal, and the Portuguese colony of Rio de Janeiro organized itself and spurred other Portuguese clubs in Brazil to join forces and send help to the Portuguese Red Cross, also to contribute with works to protect orphans, etc. Subscriptions were organised among all the Portuguese living in Brazil, to raise donations to send to Portugal.33 Other countries, like Belgium, also received help from the Brazilians. According to McCann (2009, p. 215), during the First World War, the “matrons of the Carioca society” considered it “good form” to send aid to the “unfortunates” of the war.

Therefore, Carmen’s acting was justified because it complied with what the elite ladies were doing. Her attitude was also “cleansed” because it was associated with charity, a characteristic of the Christian model of women that São João del-Rei people possibly cheered. Further evidence of this was the presence of the Daughters of Charity who, since 1880, had played an important role in educating girls in São João del-Rei, as mentioned above. For the students of the Daughters of Charity College, Louise de Marillac was probably considered a model and symbol of charity, as Eliane Lopes (1991) observed concerning the female students of a similar college in Mariana, Minas Gerais.34 For the Sisters of this congregation, charity was one of the ways of loving God. When she analysed the context in which the Company of the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul was created in France, in 1633, Eliane Lopes stated (1991) that “charity was mainly a female activity, even though it was directed by men” (p. 30). According to the author, one of those responsible for the creation of this institution, St. Vincent de Paul guided the “daughters of charity in 1653”:

The spirit of the daughters of charity is Our Lord’s love. You must know that it is exercised in two different ways, one affective, the other effective. Because the first one is not enough, my sisters, we need both. We must pass from affective love to effective love, that is, to perform acts of charity and serve the poor, with joy, courage, constancy and love. (apud.LOPES, 1991, p. 30).

In that way, by playing the actress in the operetta, Carmen was also passing from the affective love for God to effective love, courageously serving the Portuguese underprivileged. The piece of news written about the amateur club showed that, for most of the elite of São João del-Rei, it was not appropriate for a woman, or a young lady, to have her image associated with that of an actress. However, it noticed at the same time that these ideas were not to be taken too seriously, because the local people found ways to reconcile their wishes with the dominant social rules and religious tradition.

In A Mulher Soldado, Luiza Pereira played Alice, Gabriel’s alleged mistress. Luiza, like Nathalia Costa,35 must not have occupied a privileged social position among the members of the Club d. Arthur Azevedo. Some evidence allows us to say so. It was reported that Luiza’s family was going through financial difficulties to the point that the amateur troupe dedicated the proceeds of November 23, 1921 “to benefit Miss Luiza Pereira’s family” (A Tribuna, 27 November, 1921. Album 13, p. 65). Therefore, the female amateur was not financially more privileged than the other members of the Arthur Azevedo Club.

Luiza also did not stand out, either on stage or socially: the “omission” of the O Zuavo editor, who forgot to mention both Luiza Pereira and Georgina Buccholz in his critique of the operetta O Periquito is a proof of it.36 The comments on her performance are fairly succinct. According to Theóphilo Silveira (about A Mulher Soldado), “though Miss Luiza Pereira played a lesser role, she acted well and contributed to the success of the performance, adorning the scenes in which she took part with her elegant slenderness” (O Theatro, n.8, 13 July, 1916. Album 13, p. 28). However, the anonymous author, whose text was published in O Zuavo, said about the same operetta, that: “all others, except Mademoiselle Luiza Pereira, whose natural shyness showed her to be a debutante, lived up to the reputation of their company that is confirmed day after day” (O Zuavo, 25 September, 1916, Album 13, p. 34).37 The girls who did not distinguish themselves socially among the members of the amateur group, nor who stood out on stage for their skills, were given roles “of little responsibility”, roles that could stain the reputation of the daughters of privileged families.

Conceição Pimentel, the daughter of the President of the Club, Captain José Pimentel, interpreted the Mother Superior of the convent in O Periquito. The role, somehow, protected the amateur from the prejudices against the presence of women on stage, because the Mother Superior’s habit and behavior bestowed virtues upon whoever performed the part. The girl was between 12 and 13 years old at the time. Of course, she did not meet the “requirements for the part”, according to the role distribution of the period. The comments on the amateur’s interpretation were at the same time succinct and complimentary,38 except for the anonymous author’s remark published by O Zuavo newspaper. For him,

Conceição Pimentel confirmed the evidence that having her perform, dressed in the austere habit of a sister of Charity, was a bad idea. Her style is different and yesterday’s performance proved it. She has feelings for cheerful, bouncy and bustling things that do not befit a sister’s mysticism. (O Zuavo, 25 September, 1916, album 13, p. 34).

The group acting coach most likely gave the role of the Abbess to Miss Conceição because she was the daughter of the Captain, José Pimentel. The press praised the amateur for the same reason, omitting her role inadequacy. Criticism only surfaced in a single anonymous text. The President of the Club’s daughter was given a small part in the operetta, most likely to be in line with her skills, but one which showcased the amateur, due to the social role an Abbess played in that society. It was as if, on stage, Miss Conceição was portrayed as having the character’s virtues: for the public, the amateur and the character merged into one, as was always the case.

In the operetta A Mulher Soldado, Conceição played Rosie, a character who appears only in the first scene of the third act, singing a “song or tango” along with Helena (the inn’s maid) and a choir. We did not have access to other versions of this operetta, thus our assumption cannot be categorically proved correct, but we have the impression this scene was added to the play in order to enable Conceição Pimentel to participate because the scene has nothing to do with the plot. Rocha Junior states that, in that genre of musical plays, especially in the revues, “some songs had no other function than their own presentation” (2002, p. 91). However, in relation to the other ten songs of the operetta, that one stands out as the only one of its kind.

In the last scene of the second act, preceding the characters’ (Rosie’s and Helena’s) musical presentation, Clarinha (disguised as Ventura) is arrested for assaulting Sergeant Gabriel at the inn. The scene, played by Conceição Pimentel and Nininha Rodrigues, opening the third act, has no connection with the previous one. It begins in the barracks and, inexplicably, the inn maid Helena is there, celebrating with the soldiers. This is when Rosinha is summoned to sing. In the next scene, Thomé comments that, while some are happy, others (like him and Ventura, the prisoner he watches) are not. Thenceforth, the plot resumes.

Rosinha’s part seems to have been a musical presentation, added at the beginning of the third act. Although the scene does exist in the operetta’s original booklets, the character of Rosinha seems to have been created to allow the daughter of the President of the amateur club to perform. According to Theophilo Silveira, the presentation greatly pleased the public:

Miss Conceição Pimentel played the role of Rosinha magnificently. She succeeded in giving the 3rd act song or tango special emphasis, thanks to the juvenile charm with which she enhanced it and to the graceful movements with which her beautiful figure kept up with the pace of Music: this excerpt fully deserved the encores the audience honoured her with (O Theatro, paragraph 8, 13 July, 1916. Album 13, p. 28).

This time, the amateur wore a hood that really suited her, consistent with the “charm” of a 12- or 13-year-old girl. Therefore, Alberto Gomes created a strategy to give the amateur a role that was more appropriate, without compromising the operetta. The tango Conceição sang produced a certain incongruity due to its erotic content.

Third Act

Scene I

(Thomé, Helena, Rosinha and soldiers)

Chorus

Dance, sing

Nice songs

Wiggle, lassies

The leg gives

Without rest

Without rest

Continue, turn

Ride and pass

With hurry

Merry, the soldier

No sleep

Only fun.

All

Bravo! Bravo! Very good!

Helena: Come, Rosinha, sing a song

All: Yes, Yes, a song

Rosinha: No need to ask.

Music

Rosinha

When a party is in the village

Who wiggles (bis)

is the quaint girl (bis)

Nice stockings she wears

The lassie (bis)

Tied with a ribbon(bis)

Rosinha

One day, out went

A soldier (bis)

With the beautiful lassie (bis)

Tempted by a look

Fascinated (bis)

Asked her to see the garter (bis)

And tender was she (etc.)

All

Bravo, bravo, well done!

Helena: If you are thirsty and wish to get drunk, the lady has sent a barrel of wine to you soldiers in the courtyard.

All

Long live the homeland! (they leave at the sound of music)

(Handwritten copy of the operetta A Mulher Soldado, p. 39-40, GPAC collection-UFSJ).

How could the daughter of the captain, the president of the dramatic group, sing such a “spicy” song (given the moral precepts of that society) on the stages of São João del-Rei? As we saw in Theophilo Silveira’s quote, above, the scene highlighted the teasing and playful personality of the amateur, her “graceful movements” or the delicate and elegant fashion with which she (a “beautiful figure”) followed the music. We could say that her performance emphasized more the coquettish girl than the daring girl who showed her full leg up to the garter. Maybe the power of gestures, choreography, costumes, and of the girl’s presence in the scene reduced the erotic content of the song. This assumption becomes stronger if we consider that the song must have long been known by the audience and, therefore, no longer caused a great shock.39

Nininha Rodrigues played the main character of Sebastiana, O Periquito. This role also protected, somehow, the amateur from the prejudices related to the presence of women on stage. Nininha was kept immaculate by representing a distinguished Lady, who worked in the convent and was married with the blessing of the Holy Catholic Church.

In the operetta A Mulher Soldado, Nininha Rodrigues played Helena, the inn maid who, charmed by the soldiers, would not accept their money but their kisses as a tip. She would faint after every kiss, for shortness of breath. The anonymous author, who sent O Zuavo his written appraisal “au currente calamo” on A Mulher Soldado, emphasized the fainting episodes staged by the amateur: “Nininha Rodrigues, as Helena, behaved properly in the scene which greatly pleased the audience. She had clear pronunciation, very timely gestures and remarkable presence of mind. Her fainting episodes were admirable... natural” (O Zuavo, 25 September, 1916, Album 13, p. 34).

The source enables us to analyse the performance of the amateur actress who, through her physical presence, her gestures, constituted a poetic capable of pleasing the audience “immensely”. Thus, the analysis of Nininha’s performance enables us to understand the sensibilities that were in play during that moment of the show. Theophilo Silveira said, about the performance of the amateur:

Miss Nininha Rodrigues gave a performance of exceptional merit to the part of the hotel maid, having once again shown the rare qualities of her extraordinary comic vein, provoking the hilarity by the grace that, with the utmost naturalness, she emphasized situations in her role, especially the ones of fainting for lack of air (Theatro, n.8, 13 July, 1916. Album 13, p.28).

The emphasis given to the fainting episodes of the character and the fact that they caused “extraordinary” effects, causing laughter, leads us to assume that the humor of the scene freed the amateur from the judgments of the public seeing her playing the role of Helena (a woman who could be judged by her inappropriate behavior, as she would rather be kissed by servicemen than receive their tips). The definition of Henri Bergson about laughter helps us reflect on this hypothesis.

For Bergson, there are two essential conditions for comedy: the unsociability of the character and the insensitivity of the spectator. The unsociability concerns the rigid personality, therefore unsociable, of the character. For the author, “at the theater, the pleasure of laughing is not a pure pleasure, I mean, an exclusively aesthetic pleasure, absolutely disinterested. There is a second intention mixed in it (...) the unconfessed intent to humiliate, therefore, it is true, to correct at least outwardly” (2001, p. 102). In this way, we laugh at each other’s defects, while we fear the other’s laughter about our shortcomings. The virtues can also become laughable. We ridicule a virtue when it is presented in a rigid, unsociable way. For Bergson, “the comic character can, strictly speaking, conform with strict morals. It lacks only conformity with society” (2001, p. 102). A perfectly honest character is unsociable and, therefore, comical. Bergson (2001) adds that a flexible addiction would be more difficult to ridicule than an inflexible, rigid virtue.

The rigid and unsociable personality of Helena’s character speaks of the values of the são-joanense society in the period. Her unsociability is probably related to her fascination with the soldiers, a fascination that prevents her from distinguishing between a sergeant and a soldier, seeing an endless sympathy in all. This fascination makes her refuse gratuities, and accept the kisses of all without distinction. Such behavior was in agreement neither with the customs of a society where the elite always sought to distinguish itself, nor with the army, an institution marked by hierarchy. This rigidity of character mocked and humiliated women who craved soldiers indiscriminately.

The spectators are insensitive to this addiction of the character and that is why, we think, the amateur actress would be forgiven for playing that role. For Bergson, “laughter is incompatible with emotion” (2001, p. 104). An addiction in itself is not comical; it becomes comical if it doesn’t move the viewer. If the scene causes sympathy, pity or fear in the public, it will no longer be able to make them laugh. The rigidity of the vicious emotion in itself (the indiscriminating fascination of Helena with the soldiers) would prevent the viewer from entering into a relationship with the rest of the soul in which the emotion settles.

Another mechanism to prevent the viewer from getting emotionally involved with Helena’s addiction was the distraction. According to Bergson, to prevent the viewer from taking the scene seriously, it is necessary to prevent them from focusing on the actions and focus more on the gestures. The author distinguishes gestures from actions. Gestures would be “attitudes, movements and even speeches by means of which a state of soul manifests itself without a purpose, without gain, only through a kind of internal itching”. Yet, “the action is desired, in any conscious event” (2001, p. 107).

In the case of the scenes involving Helena’s character, the distraction in A Mulher Soldado that made the audience insensitive to her addiction was the fainting. Bergson says that a scene is comic from the moment that the public’s attention is drawn to the gesture and not to the act. Helena’s fainting was identified by critics as the funniest moment of her interpretation. Therefore, we can say that the fainting was the gesture that distracted the são-joanense audience from the character’s addiction and, thus, she would have been forgiven for playing a vicious character. The comic personality of the character is what allowed a respectable miss of são-joanense society to play it.

Through these theatrical games, the amateur actress met the expectations of the são-joanense public, eager for moments of laughter. She also contributed to the group in helping them renew the theatrical repertoire of the city, leaving behind the “old dramas” and acting “happy plays”. Arthur Azevedo put São João del-Rei in the theatrical scene of Rio de Janeiro and the cities of Europe that, at that time, cheered operettas, revues and zarzuelas.40

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

We can say that the acting coach of the Club Arthur Azevedo, Alberto Gomes, followed the advice of Garraio (1911), the author of the manual for amateurs, up to the limit of the interests of the association board and the moral precepts of são-joanense society. To that extent, the choice of the operettas O Periquito and A Mulher Soldado was quite right because it took into consideration the number of male and female amateurs needed for the play, and made possible the public exposure of the daughters of the são-joanense elite, protecting them from public judgment through the roles they played. The social position of the amateurs was also an element considered in the distribution of characters among the members of the Club.

From the analysis of the performances that took place during the presentations of the operettas, we see that some hegemonic sensibilities were reinforced by these presentations. Such sensibilities include the feelings of shame and inappropriateness of married women on the stage, the desire of the parents of the sao-joanense elite, and their pride in displaying their brave, virtuous and charitable daughters, ready to fulfill their roles of good wives and mothers. In addition, acting on the stage certainly provoked, in the girls and women of those early years of the twentieth century, the feeling that they were situated between a past that condemned them to the private sphere, and an ambiguous and tense present that allowed them certain participation in the public sphere.

The plays also reinforced the social and economic distinctions, and the differences between the learned and the mediocre, generating a kind of conformism and feelings of superiority and inferiority in some others, which contributed to justifying the different types of hierarchization and inequalities that characterized the period. Therefore, through the sensations caused by the physical presence, gestures and actions of the female and male amateurs, that is, through their performances during the presentations put on by the group, learned and taught themselves sensitivities related to the social roles and power relations established in that society.

REFERENCES

ADÃO, Kleber do Sacramento. SADI, Renato Sampaio (orgs.). Lazer em São João del-Rei: aspectos históricos, conceituais e políticos. São João del-Rei, ed. UFSJ, 2011. [ Links ]

ADÃO, Kleber do Sacramento . LIMA, Alex Witney; CAMPOS, Áurea Ester Dornelas; SILVA, Thiago Barbosa Júnior . O futebol em São João Del-Rei: apontamentos acerca de sua história (1907 a 1944). In: XI Congresso Nacional de História do Esporte, Educação Física, Lazer e Dança. Viçosa - MG, 2009. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Marcelo Crisafuli Nascimento. “Folguedos do Povo” e “Partida Familiar”: a música e suas manifestações populares em São João del-Rei (1870-1920). Dissertação de Mestrado, Sociologia, Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei, 2010. [ Links ]

AREND, Silvia Fávero. Meninas: trabalho, escola e lazer. In: PINSKY, Carla Bassanezi; PEDRO, Joana Maria. Nova história das mulheres no Brasil. São Paulo: Contexto, 2013. p.65-83 . [ Links ]

ARRUDA, Maria Aparecida. Formar almas, plasmar corações, dirigir vontades: o projeto educacional das Filhas da Caridade da Sociedade São Vicente de Paulo (1898-1905). Tese de Doutorado, Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2011. [ Links ]

BASTOS, Sousa. Diccionário do Theatro Portuguez. Lisboa: Imprensa Libanio da Silva, 1908. [ Links ]

BERGSON, Henri. O riso: ensaio sobre a significação da comicidade. Trad. Ivone Castilho Benedetti. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2001. [ Links ]

COSTA, Alexandre J. Gonçalves. Os Frades na Cidade de Papel. A Ação Católica em São João del-Rei 1905-1924. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2000. [ Links ]

COSTA, Luís Manuel Neves. A Assistência da Colónia Portuguesa do Brasil, 1918-1973. História, Ciências, Saúde (21) - Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, 2014, p.727-748. [ Links ]

COUTO, Euclides de Freitas; BARROS, Aluízio Antônio de. Futebol e Modernidade em São João del-Rei/MG: o caso do Athletic Club (1909-1916). In: Anais do XXVISimpósio Nacional de História - ANPUH. São Paulo, julho 2011. [ Links ]

D’INCAO, Maria Ângela. Mulher e família burguesa. In: DEL PRIORE, Mary (org.). História das mulheres no Brasil. São Paulo: Contexto , 2006. [ Links ]

GARRAIO, Augusto (ensaiador nos theatros de Lisboa e Porto). Manual do Amador dramático: guia prático da arte de representar. 2. ed., Lisboa, 1911.Acervo da Bibliothèque lusophone Fondation Calouste Gulbenkian. Paris. Código: FCG CCP. [ Links ]

GUILARDUCI, Cláudio José. A cidade de São João del-Rei nas entrelinhas dos manuscritos do teatro de revista na Belle Époque: um testemunho da história cultural são-joanense. 2009. 269 f. Tese. (Doutorado em Teatro). Centro de Letras e Artes da Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2009. [ Links ]

GOUVEA, Maria Cristina Soares de. Meninas nas salas de aula: dilemas da escolarização feminina no século XIX. In: FARIA F FILHO , Luciano Mendes de (org.). A infância e sua educação: materiais, práticas e representações (Portugal e Brasil). Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2004. [ Links ]

GUERRA, Antônio. Pequena história de teatro, circo, música e variedades em São João del-Rei (1717-1967). Juiz de Fora: Esdeva, 1968. [ Links ]

LOPES, Eliane Marta Teixeira. Educadores de mulheres: as filhas da caridade de São Vicente de Paulo: servas de pobres e doentes, espirituais, professoras. Educ. Rev., Belo Horizonte (14), 1991. [ Links ]

MENEZES, Lená Medeiros de. (Re)inventando a noite: o Alcazar Lyrique e a cocote comédiénne no Rio de Janeiro oitocentista. Revista Rio de Janeiro: dossiê temático Literatura e Experiência Urbana (20-21), Rio de Janeiro, 2007, p. 73-91. [ Links ]

MENEZES, Lená Medeiros de. Aimée, a Cocotte Comedienne e o toque feminino francês na noite carioca. (s.l.) (s.d). http://www.labimi.uerj.br/artigos/1306519276.pdf - acesso em 17 de dezembro de 2014. [ Links ]

MCCANN, Frank D. Soldados da Pátria: história do Exército Brasileiro. Trad. Laura Teixeira Motta. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército, 2009. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Marcus Aurelio T. De. Educação dos sentidos e das sensibilidades: entre a moda acadêmica e a possibilidade de renovação no âmbito das pesquisas em História da Educação. História da Educação, v. 22, n. 55, p. 116-133, 12 ago. 2018. [ Links ]

OSTOS, Natascha Stefania Carvalho de. A questão feminina: importância estratégica das mulheres para a regulação da população brasileira (1930-1945). Cadernos Pagu (39), Campinas/SP, 2012, p.313-343. [ Links ]

PAVIS, Patrice. Dicionário de teatro. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2011. [ Links ]

PESAVENTO, Sandra Jatahy. Sensibilidades: escrita e leitura da alma. In: PESAVENTO, Sandra Jatahy; LANGUE, Frédérique (org.). Sensibilidades na história: memórias singulares e identidades sociais. Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, 2007. [ Links ]

REIS, Ângela de Castro. Cinira Polonio, a divette carioca: estudo da imagem pública e do trabalho de uma atriz no teatro brasileiro da virada do século XIX. Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Nacional, 1999. [ Links ]

ROCHA J JUNIOR, Alberto Ferreira da. Teatro brasileiro de revista: de Artur Azevedo a São João del-Rei. Tese de Doutorado, Artes Cênicas, USP, 2002. [ Links ]

SA, Carolina Mafra de. Do convento ao quartel: a educação das sensibilidades nos espetáculos teatrais realizados pelo Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, em São João Del Rei MG (1915-1916). Belo Horizonte, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2015. [ Links ]

TAVEIRA, Leonardo de Mesquita. A mulata e o malandro: a caracterização vocal do personagem-tipo na música do teatro de revista brasileiro, entre as décadas de 1880 e 1930. In: Anais do XVII Congresso da ANPPOM, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música - Instituto de Artes da UNESP. São Paulo, 2007. [ Links ]

VENEZIANO, Neyde. O Teatro de Revista no Brasil-Dramaturgia e Convenções. Campinas/SP: UNICAMP, 1991. [ Links ]

ZUMTHOR, Paul. Performance, recepção, leitura. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2007. [ Links ]

1 This article presents some of the results from Carolina Mafra de Sá’s thesis, advised by Professor Ana Maria de Oliveira Galvão, entitled: “From the convent to the barracks: education of the sensibilities in theater performances of the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, in São João del-Rei - MG (1915-1916)” (SÁ, 2015)..

4 As important examples, Oliveira (2018) cites the works of Johan Huizinga (1919), Paul Zumthor (1993, 2005), Werner Jaeger (1986), Norbert Elias (1991), Mikhail Bakhtin (1999), Walter Benjamin (2008, 2009, 2012, 2013), Edward Thompson (1989, 1998) and Carlo Ginzburg (1989, 2010), Lucien Febvre (1985), Alain Corbin (2005), Peter Gay (1989), Gilberto Freyre (1936) and Willian Ospina (1999, 2008).

5 Professor Marcus Aurelio Taborda de Oliveira, author of the article quoted, coordinates the Center for Research on the Education of the Senses and Sensibilities (NUPE), which is part of the Research Center in History of Education-(GEPHE). The group has been investigating the history of education of the senses and sensibilities, establishing exchanges and partnerships with several Brazilian and foreign researchers.

7 The people of São João del-Rei watched and participated in football championships (see ADÃO et al. 2009 and COUTO et al. 2011), went to cafes and the cinematograph (GUERRA, 1968, p. 115), saw the circus and theater performances performed by itinerant companies, and amateur and professional groups in the city. The streets were for meetings, parties, commercial trade and soccer games. For more information, see Adão; Sadi (2011).

8 For detailed information on the subjects investigated, see chapter 2 of the thesis mentioned in this paper (SÁ, 2015).

9 For more information on what “world class” plays are, from the point of view of the members of the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, see chapters 3 and 4 in Sá (2015).

10 The Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo produced a free newspaper that was distributed during their shows. In the sixth edition, the editor published the article Mise-en-scène taken from the Portuguese acting coach, Garraio. Garraio intended his book to serve as a guide to the scenic works of amateur groups and the curious. The manual presented techniques and ways to do theater that circulated and were known by the Portuguese and Brazilians. If the members of the club reproduced excerpts of this book in their newspaper, they possibly also used it as a guide for its activities.

11 Article 21, page 2 of the Estatutos do Clube Teatral Arthur Azevedo. A photocopy of the typed document can be found in the collection of the GPAC, UFSJ.

12 As for the operetta genre, according to Sousa Bastos (1908), author of the Diccionário do Theatro Portuguez, “you might say it’s an Opera-Comique of minor importance”. A “truly happy” genre. Operettas may be understood as “the burlesque opera, although some of them have greater musical demands” (p. 102).

13 In addition to the operettas, or comic operas, revues and zarzuelas are also considered light plays.

14 For more information on the repertoire of the club, its relationship with Arthur Azevedo and the context in which such performances took place, see chapters 3 and 4 of Sá (2015).

15 According to the translators of the Pavis dictionary (2011), J. Guinsburg and Maria Lúcia Pereira, there is no corresponding term in Portuguese. According to Pavis (2011), during the 19th century, theatrical creation was obsessed with emplois. This is a word that, according to the author, means the “type of role that corresponds to the actor’s age, appearance and style of interpretation. (...) The emploi depends on the age, morphology, voice and personality of the actor” (p.121). Michel Corvin, in Dictionnaire encyclopédique du théâtre, defines emploi as “ensemble des rôles d’une même catégorie requérant, du point de vue de l’apparence physique, de la voix, du tempérament, de la sensibilité, des caractéristiques analogues et donc susceptibles d’être joués par un même acteur. On dit : avoir le physique de l’emploi” (CORVIN, 1998, Apud DUBEY, 2010). Translation under our responsibility: a set of roles of the same category that demand, in terms of physical appearance, voice, temperament and sensitivity, similar characteristics and, therefore, are likely to be interpreted by the same actor. They say: to have the physique of the emploi.

16 It is not possible, within the limits of this publication, to describe the plot of two operettas in detail. See Sá (2015) for that.

17 We believe that every theatre group made changes, adding or removing characters, to make acting feasible. In the case of O Periquito, the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo added two soldiers, possibly so that all the members could participate in the operetta and also to complete the choirs.

18 The male characters are: Periquito; Liborio, convent gardener; Lucas, dance master; Carlos de Mello, army officer; Antonio de Vasconcellos, ditto; Luiz de Sá, ditto; Tiburcio, inn servant; four other officers. (Flyer for the opening of the operetta attached on page 14 of album 13).

19 The female characters are: Mother Superior of the convent; Dona Sebastiana, director of the convent; Ritinha, student; Branca de Athayde; Camilla de Athayde; Amelia, actress. (Flyer for the opening of the operetta attached on page 14 of album 13).

20 Francisco Velloso; Altamiro Neves; Alberto Gomes; Alberto Nogueira; Luiz Ribeiro; Marcondes Neves; Euclydes Rocha; Humberto Preda; Joaquim Rossito; Luiz Valle. (Flyer for the opening of the operetta attached on page 14 of album 13).

21 Francisco Velloso; Altamiro Neves; Alberto Gomes; Alberto Nogueira; Luiz Ribeiro; Marcondes Neves; Euclydes Rocha; Humberto Preda; Joaquim Rossito; Luiz Valle. (Flyer for the opening of the operetta attached on page 14 of album 13).

22 Captain, Lieutenant, Villar, Gabriel, Thomé, Ventura, Viscount and Corporal João. (O Theatro, number 4, May 12, 1916, p. 3. Álbum13, p. 21).

24 Marcordes Neves, Carlos Neves, Alberto Gomes, Antônio Guerra, Francisco Velloso, Humberto Preda, Luiz Ribeiro and José Miranda. (O Theatro, nº 4, 12 May, 1916, p.3. Album 13, p. 21).

25 Margarida Pimentel, Luisa Pereira, Conceição Pimentel and Nininnha Rodrigues. (O Theatro, nº 4, 12 May, 1916, p.3. Album 13, p. 21).

26 This Association between the image of the actress and the image of the prostitute was analyzed by Lená Medeiros de Menezes in her studies in 2007, 2014 and by Angela de Castro Reis in a 1999 publication.

27 Maria Angela D’Incao, analyzing the woman and the bourgeois family through the work of Machado de Assis from the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth centuries, notes that “social cycles expand, women of the elite take to the streets and salons displayed and coquettes, ambitious boys embrace liberal professions and enter the salons of the best families, expanding the marital market and the possibilities of choice among the more affluent groups. The norms of behavior become more tolerant, as long as the appearances and the prestige of the good families are maintained, and not undermined” (D’INCAO, 2006, p. 238). Natascha Stefania Ostos (2012) adds that “the urban environment offered women the possibility of knowing other forms of coexistence, beyond those experienced in the domestic space and in family relationships” (OSTOS, 2012, p. 315). However, the author adds that “regardless of their social status, all women found legal limits to the exercise of their freedom. Under the Civil Code of 1916, the husband was the ‘head of the conjugal society’ in charge of administering the property of the couple, establishing the family home and providing for the maintenance thereof. (...) The married woman was considered relatively incapable of exercising certain legal acts, being able to work outside the house without previous authorization of the husband, exercising the role of guardian or curator, litigating in civil or criminal court and contracting obligations; only in case of the absence or impediment of the spouse, did she have the right to exercise power over her children (Civil Code, 1916: articles 6, 233 to 380)” (OSTOS, 2012, p. 316). We note, therefore, that the freedoms won by urban women and bourgeois families in the early twentieth century were again limited at the time when these women were married.

28 According to Guerra the children in the photo are: “Antônio Guerra; Antônio Barreto; Altamiro Neves; Alberto Nogueira and Marcondes Neves; Carmen Mello; Anita Mello; Manoelita Guerra; Ofélia Velloso; Maria da Glória Barreto and Antônio da Costa Mello; José Velloso; Maria de Lourdes Barreto; Margarida Barreto and Telêmaco Neves” (1968, p. 101).

29 According to Guerra, from left to right: Guiomar Macêdo; Isolina Gallo; Ritinha Nogueira; João Chagas; Manoelita Guerra; Natália Costa; Antônio Guerra; Anita Mello; Lolola Osório; Carmen Mello” (1968, p. 125).

30 According to O Zuavo, 20 February, 1916 (Album13, p. 14v), at the premiere of the operetta O Periquito the “chorus of the convent students was sung whimsically. Six pretty faces played these roles. We were so jealous of Liborio! Mademoiselles Conceição Pimentel, Nathalia Costa, Nininha Rodrigues, Cecilia Costa, Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, Nenê Pimentel, Diquinha and Lucilia Ribeiro, Hilda Miranda, cooperated enormously towards the final result” (emphasis added).

31 From the second half of the 19th century, according to Silvia Fávero Arend (2013), physicians, lawyers, educators and rulers began to think and to create a new understanding about childhood. In order to promote demographic growth that would meet the demands for workers in the increasing factories, for consumers of the products manufactured on a large scale, and for men to compose the army battalions, it was necessary to decrease the rates of under-five mortality. “According to this new assessment of human life, people between 0 and 18 years came to be regarded as ‘growing beings’, both from the physical and from the psychological point of view. During this ‘phase of life’, now well-defined, practices that could put the health of future men and women at risk, namely, sexual activities and certain types of occupations, would be forbidden. Childhood would be the key moment of the socialization processes for entering the adult world and it would be marked, above all, by school knowledge” (AREND, 2013, p. 70).

32 Such an institution was an initiative of the religious congregation of the Filhas de Caridade da sociedade São Vicente de Paulo, which came to town in the 1880s, working always with assistance and educational institutions like the Santa Casa de Misericórdia and the Asilo de órfãs which was associated with it. For more information, see Arruda (2011).

33 According to Marcelo Crisafuli Nascimento Almeida (2010), on 12 July, 1884, the newspaper Arauto de Minas advertised instrumental music and piano lessons at Collegio Conceição.

34 Balbininha Santhiago was a pianist and a piano teacher. She was responsible for the rehearsal of the musical parts of some plays of the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo. In addition, she was the mother-in-law of the Club’s President, Captain José Pimentel, and the grandmother of the amateurs Conceição, Luiza and Margarida Pimentel. According to Almeida (2010), there were private music tutors in São João del-Rei, such as the priest José Maria Xavier and Martiniano Ribeiro Bastos.

36 According to Eliane Lopes (1991), Louise de Marillac had an important role when the Companhia de Filhas de Caridade São Vicente de Paulo was established in France in 1633, as she became a role model, even for the Brazilian women 300 years later. According to the author, students from a school run by the Filhas da Caridade in Brazil wanted to be Luisas, or Luisinhas: as the students who followed the sisters in the charity works in Mariana were called (account of a former student in 1988).

37 Nathalia Costa played two actresses (Tosca and Amelia) and, unlike what happened with Carmen Mello, no justification or explanation was given on behalf of her honor in the newspapers of the amateur club.

38 “A regrettable omission in its last issue caused O Zuavo to make a mistake that we were quick to mend and apologize for. When praising all the components of the perfect group of the Arthur Azevedo, we did not include the names of the dear and lovely demoiselles, Georgina Buccholz and Luiza Pereira. They did not need any compliments to grow in the esteem of their sincere admirers, but O Zuavo, adhering to its reputation of being fair, could do nothing but praise their good performance, and today it is very pleased to applaud both interesting amateurs, to whom O Periquito owes so much. (O Zuavo, 27 February, 1916. Album 13, p. 15v).

39 According to the editor of the newspaper, the text would have been written on 18 September, 1916.

40 According to Theophilo Silveira, “Mademoiselles Conceição Pimentel, who played Abadessa, and Nininha, who played Sebastiana, did an excellent job”. (O Theatro, number 3, 4 April, 1916, Album 1, p. 38); O Zuavo, 20 February, 1916, published: “Mademoiselles Conceição Pimentel, Nathalia Costa, Nininha Rodriguez, Cecilia Costa, Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, Nenê Pimentel, Diquinha and Lucilia Ribeiro, Hilda Miranda, cooperated enormously for the result achieved”. (Emphasis added. Album 13, p. 14v).

41 At that time, the popular music was well known by the elite of São João del-Rei. According to Marcelo Crisafuli Nascimento Almeida, genres like the maxixe, cateretê, lundo, Brazilian tango, among others, coexisted with the classical music production. “It was the stage of the theatre or the orchestra pit that allowed the meeting of the popular musical genres with classical music” (2010, p. 18). The author, referring to the play staged in 1917, written by Durval Lacerda from São João del-Rei, O Número Um, makes the following observation: “(...) the local elite, following a trend that extended to the entire country, aided by the revue, must have learned to respect the ‘national dances’ and ‘the popular festivities’ since, in the words of one of the characters from ‘Número Um’, the maxixe, in this case, ‘terror of the old family, is today worshipped in the ball rooms’”. (ALMEIDA, 2010, p. 20).

42 When staging light plays, according to the newspaper A Tribuna, 14 May, 1916, the Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo showed “the degree of progress that the local theatre has reached: the repertoire was completely modified going from the tedious drama to the joyful and musical plays” (Album 1, p. 39v, GPAC collection). For more details on the repertoire of the group, see Chapter 3 and 4 in Sá (2015).

Received: June 18, 2018; Accepted: October 22, 2018

texto em

texto em