Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.35 Belo Horizonte jan./dez 2019 Epub 25-Jul-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698210399

ARTICLE

FROM FACE-TO-FACE TEACHING TO ONLINE TEACHING: THE LEARNING OF UNIVERSITY TEACHERS IN DISTANCE EDUCATION

IFederal University of Uberlândia, Uberlândia, MG, Brasil

This study deals with how it has been occurring, to professors with experience in the face-to-face university teaching, the learning of the teaching practice in the online classroom in a distance education program of a higher education institution. It aims to investigate the learning of these professors to teach when, from the face-to-face modality, they started working as online tutors conducting the pedagogical mediation in the virtual environment of distance undergraduate courses. It uses as methodology the thematic oral history, for which semi-structured interviews were fulfilled with five university teachers with the profile defined by the study. It highlights that the learning of the teaching in distance undergraduate courses represents a new signification of what these university teachers commonly did in the face-to-face context due to the time and space specificities of the online classroom regarding the relationship with the student body, the knowledge construction and the teaching work.

Keywords: Distance Education; Online Teaching; Teaching Knowledge; Teaching Practice; Higher Education

Este estudo trata de como vem ocorrendo, para professores com experiência na docência universitária presencial, a aprendizagem da prática docente na sala de aula online em um programa de EAD de uma instituição de ensino superior. Seu objetivo é investigar as aprendizagens desses professores para ensinar quando, da modalidade presencial, passaram a atuar como professores-tutores online em cursos de graduação a distância. A metodologia usada foi a da história temática oral, para a qual foram realizadas entrevistas semiestruturadas com cinco professores com o perfil delimitado pelo estudo. Esta pesquisa evidencia que a aprendizagem do ensinar em cursos de graduação na modalidade a distância representa uma ressignificação daquilo que esses professores universitários comumente realizavam no contexto presencial devido às especificidades do tempo e do espaço da sala de aula online e ainda quanto ao relacionamento com o corpo discente, à construção do conhecimento e ao trabalho docente.

Palavras-chave: EAD; Tutoria Online; Saberes Docentes; Práticas Docentes; Ensino Superior

INTRODUCTION

The theme of this investigation is online teaching in undergraduate courses in the distance education (DE) mode within a higher education institution, being its main objective to investigate the learning of the teaching in the electronic classroom based on the experience of university teachers used to teach in the presential higher education and who, later, began to mediate long-distance teaching practices. In this study, the term ‘online’ was adopted in reference to the digital technologies used in the virtual learning environment (VLE) of the DE program of the university field of this research.

In that institution, the ‘online teacher-tutor’1 is the professor who accompanies, guides, motivates, and evaluates the students in their academic activities developed in the VLE. Thus, the space-time dynamics of that classroom began to demand teaching knowledge of these teachers in order to allow them to develop educational practices by means of digital resources, which added to the university teaching specific elements of the online education, such as the non-presential contact between teachers and students, the teaching shared with a multiprofessional team or the space-time flexibility to study and to teach.

The willingness to direct their teaching experience towards online teaching encompasses the transformation, the recriation or the reformulation of what these professors commonly do or used to do in the presential classroom in order to develop a teaching practice to the cyberspace classroom. Therefore, this study was conducted based on the following questioning: how has it been, to teachers experienced in the face-to-face university teaching, the learning of the teaching in the online classroom in undergraduate courses in the distance education mode?

The demand for such courses grows every year in Brazil, which means the need for university teachers qualified to educate in that mode. In DE teaching, the experience of the presential teaching should be considered in the knowledge construction to the non-presential teaching. On the other hand, the pedagogical use of the Digital Technologies of Information and Communication (DTIC) in DE could help to include these resources in the presential education in a more effective way. Thus, face-to-face teaching and online distance teaching should not be seen as antagonists, but as ways of teaching with their own characteristics and that, in their differences, can contribute to each other´s improvement.

PEDAGOGICAL MEDIATION IN THE CYBERSPACE: IN SEARCH OF WAYS

The technological revolution experienced in the passage from the 20th century to the present one has meant more than a simple modernization in the means of communication and production; digital technologies made possible another social space, but with the differential of an unprecedented physical-temporal dynamics that led to the formation of new cultural practices. This place was called cyberspace; according to Castells (1999), it is an integrated communication system based on the digital language, which allows the distribution of words, sounds and images on a global scale, causing cultural goods to circulate through its frames and to reach individuals who can assimilate and customize them according to their identity. In this respect, Lévy (1999) highlights as one of the distinguishing features of that interactive communication network the speed with which it and its contents are transformed, making it difficult to analyze the digital culture.

The technological interfaces can be converted into pedagogical resources that can be used in different contexts and educational levels. Their incorporation into educative practices must be done “[…] without neglecting the indispensable human mediation of access to knowledge” (LÉVY, 1999, p.173). Thus, Paniago (2016) argues that education mediated by networked technologies should aim at a pedagogy permeated by the marks of digital culture such as flexibility, openness, interlocution, interchange, complexity, creation, collaboration. More than results, it is an educative practice that should be interested in processes, relationships and exchanges established between and by the individuals participating in the educational act.

One mode of education that experienced significant expansion and diversification with the enhancement and accessibility to digital technologies was DE, since the DTIC became the pillars of most non-presential undergraduate courses at the present time. Easy access to the internet allows synchronous and asynchronous connections between individuals located in different spaces, and thus DE has incorporated that factor to create its “classroom”, the so-called virtual learning environment. Therefore, those who were unable to attend the conventional school or those in search of a more open form of education were allowed a formal opportunity to educate and to professionalize themselves, through educational practices that permit greater student autonomy to organize time and space of study.

DE also provokes reflection on what it is to be a teacher, since it opened the precedent for different teaching roles, such as the responsible-teacher, who is in charge of the planning of a discipline; the content-writer-teacher, who elaborates didactic materials; the trainer-teacher, who forms and accompanies the tutors; or the tutor-teacher, who mediates educator-undergraduates´ interactions. Such specific and interdependent teaching assignments instituted the polyteaching, a collaborative and fragmented form of teacher work (MILL, 2012).

Before that diversity, this study focused on the figure of the ‘tutor-teacher’ or ‘online teacher’, fundamental educator in DE. Despite the lack of definition of what constitutes virtual teaching (MILL, 2012), making their assignments vary from institution to institution, it can be observed as recurring actions in the practice of that teacher direct contact with students in the VLE to guide and motivate the interactive construction of specialized knowledge, clarify doubts and elaborate feedback on students’ performance in the academic activities towards the learning progression (SENO; BELHOT, 2009).

It is necessary to reflect the possible ways of learning before the new reality of the teaching work for experienced university teachers, beginning, subsequently, as online tutors in long-distance undergraduate courses. Finding trails for the (re)construction of their professional identity can make them more flexible to changes in an education mode in which the experience and the knowledge constituted in the face-to-face teaching may prove insufficient or inadequate for the development of the online teaching. In this sense, renewed teaching knowledge should prove useful in the organization of a tutorial work routine in undergraduate courses whose teaching and learning spaces integrate their participants in different times and spaces through digital interaction and communication technologies.

In this respect, according to Tardif (2000), teaching knowledge is temporal, plural, heterogeneous, personalized, and located. Teaching knowledge is temporary because it results from the memory and the experience of the teacher throughout his or her school life as a student and as a professional; from the experiences and feelings in relation to teaching that help in the organization of a work routine; from the lived moment in the career in a certain school community. Teaching knowledge is plural and heterogeneous because it results from their personal, academic, experiential and didactic-pedagogical culture, applied to guarantee the interaction and integration of students in an environment favorable to teaching and learning. Teaching knowledge is personalized and situated because the teacher is a person with physical and emotional characteristics that, from his or her body, mediates a formative process involving human beings with equally distinct personal characteristics - whether apprentices or co-workers.

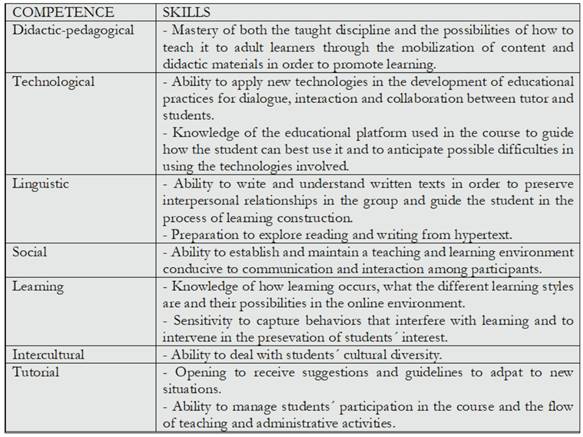

Researches developed in the scope of the Brazilian postgraduation have also contributed to design ways for the development of the online tutor, as a mediator of educational practices in undergraduate distance courses, due to the approach of diverse variables related to the experiences of teachers challenged to teach in the digital classroom. Based on a survey of skills and competences in online tutoring, it is presented the following synthesis in Table 1, according to Amaro (2015), Arruda (2011), Garcia (2013), Oliveira (2015), Santos (2012), and Spíndola (2010).

The monitoring of different experiences in educational practices developed in online tutoring can contribute to the systematization of the reflection of that educational mode, offering ways that can contribute to the online tutors not only to operate new technologies in undergraduate distance courses, but to qualify these educators to teach by means of these resources and to assess their relevance in the teaching and learning process. In addition, the peculiarity of the space-time dimension of the online classroom demands from that teacher skills and knowledge oriented to the development of the teaching work with organization, correctness, readiness, cordiality and sensitivity; factors necessary for the creation and the maintenance of a technological environment conducive to education.

It is expected that the revision of the concepts and the researches of this theoretical framework can help to understand how these competences have been developed by online tutors in off-campus undergraduate courses. The understanding of the teaching work in online tutoring, besides the raising of the DE quality by means of the teachers´ performance, can contribute to the professional recognition and the pedagogical appreciation of the actions conducted by those teachers.

THE METHODOLOGICAL PATH

This study had as its research field a private higher education institution located in the state of Minas Gerais and founded in the 1940s. Besides face-to-face courses offered from its foundation to the present, in areas such as health, engineering, business, technology, law and teacher education; its DE program began in the 2000s with a solo specialization course and a teacher training course in partnership with the state government. Between 2005 and 2006, the offer of its non-presential undergraduate courses in the areas of teacher education, bachelors and technologist began.

Over the years, there has been a diversification in the communication channels between students and pedagogical and administrative teams of the courses, didactic materials, evaluation system, pedagogical mediation, academic activities and general monitoring of the DE mode. This process was supported by the Information Technology (IT) sector of the institution, active since the 1990s, in relation to structuring and developing an VLE capable of meeting the administrative, didactic and pedagogical needs of those involved in the DE practices. The institution chose to create its own VLE, made available to its academic community in the early 2010s.

As a result, nomenclatures and professional assignments have also changed, and the figure of the online tutor-teacher, the educator targeted at this study, emerged in 2015. This professional is hired under the Brazilian legal labor system as a higher education professor at that institution and his or her work consists in the pedagogical mediation of educational practices in the VLE. In that DE program, it is possible for the professor to perform the functions of online teacher and responsible-teacher, besides teaching in the presential classroom, according to the workload for which he or she was hired - some hours per week, 20 hours per week or 40 hours per week. As for the online tutoring, the educator must be present on the main campus of the institution, on the days and times institutionally agreed in order to perform pedagogical duties, where there is a room with structure for the development of this kind of educational mediation. Thus, the delimited profile for the participants of this research was to have previous experience in the face-to-face university teaching with subsequent entry into the online teaching at long-distance teacher education courses.

Consequently, the proposal of this study was presented to the Research, Post-graduation and Extension Dean´s Office of the institution and, after obtaining the consent for its accomplishment, the teachers with a professional trajectory corresponding to the one to be investigated by the research were identified. The definition of possible participants for the study was initially made based on information provided on the institution´s website, which indicated a faculty composed of 66 teachers working in the online tutoring in the area of teacher education. Subsequent consultations with course managers and pedagogical staff indicated that 19 online tutors had started university teaching in the presential classroom with posterior teaching activities in DE. These teachers were contacted to be presented to the main information about the study and also to be invited to participate in the investigation. Thus, five online tutors were willing to collaborate on the study, after reading and signing an Informed Consent Form (ICF).

In order to investigate the learning of these teachers who, from face-to-face university teaching, began to teach in the DE mode at this level of education, the thematic oral history was chosen as methodology. The data collection procedure was the semi-structured interview2 conducted with each of the five teachers who started university teaching in the presential classroom and, later, began online teaching in long-distance teacher education courses. According to Fonseca (1997), this kind of investigation allowed the teachers participating in the research to expose their way of being, feeling, thinking, acting and teaching, being that the narratives built in the interviews made it possible to know the respondents´ process of training and acting in online teaching.

In addition, Meihy (1998) highlighted that the starting point of the thematic oral history is a specific and pre-established subject that refers to a definite event in the life of the interviewee. This was the case of the present study in which the online tutors participating in the research were informed that the nature of their report would be about their professional experience in a very particular form of teaching compared to what is usually meant to teach. Online teaching, developed in digital classrooms and supported by new technologies, implies the teacher’s willingness to learn new didactic-pedagogical actions and behaviors for the development of educational practices focused on this specific context.

Concerning the construction of the interview script, it followed the same author´s orientation, according to which that guide must be in agreement with the objectives intended to be achieved with the research, since it is a fundamental instrument for the search of the expected clarifications. Thus, the conduction of the interviews emphasized the opportunity to listen, in a spontaneous and welcoming way, the online tutors who accepted to narrate their story about the learning of teaching in the online classroom after the experience in the presential higher education. For this, care was taken to include broader questions, in a logical sequence, so that the interviewees could expose their memories, experiences and reflections about their educational history in online education (MEIHY, 1998).

Thus, the guide of the interviews with the participants of this study addressed the following aspects: the transition from face-to-face classroom to online classroom; the set of assignments as a tutor in the DE program; the organization of the workflow, according to its teaching time in the institution; the interviewee’s appreciation of the tools and resources of the institutional VLE; the pedagogical mediation of the disciplines, according to the interest and training of the interviewee; prior contact with teaching materials and academic activities; the use of teaching strategies for distance learning; the interaction of students in different times and spaces; the delimitation of the student’s profile, considering the DE mode; the feedback for student orientation; the exercise of the pedagogical authority of the online tutor.

The process of recording, transcribing and textualizing the interviews to collect the stories of teachers moving from face-to-face teaching to online teaching followed the recommendations of Meihy (1991). According to the author, care is required so that the reliability and intelligibility of the narratives are guaranteed. For that, a careful reading of the transcribed version of the interviews was made to highlight keywords that evidenced the singularity of the interviewees’ reports and, from that action, these terms guided the textualization of the discourse. At the end of the process, the research participant was assured the right to access the final version of the textualization to confirm his or her consent and, if necessary, for changes, subtractions or additions.

Data provided by the textualized narratives were analyzed based on the competences presented in 1 and the theoretical framework of the study in order to understand the learning of teaching in distance undergraduate courses by the experiences of university educators who, from face-to-face teaching, began to act in online teaching. It was, therefore, intended to clarify how the teaching experience of teachers, marked by the practice of the presential classroom, is transformed to meet the demands of the digital classroom, pointing out ways to the development and the recognition of the online teaching in the context of distance undergraduate courses.

FROM FACE-TO-FACE TEACHING TO ONLINE TEACHING: PRESENTATION AND DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

Being a teacher is to perform a professional activity that requires qualification for both the disciplinary knowledge and the pedagogical knowledge, since teaching, besides being a social and historical act, implies the formation of people to understand and to interpret information in a process for the construction of new knowledge. In the era of DTIC, teaching work has been faced with new paradigms that influence practices, processes, times and school spaces. These influences can become more sensitive when the teacher marked by face-to-face teaching starts acting in online teaching in DE. Conducted between June and August 2017, the narratives of the five university teachers participating in this study refer to their discoveries and confrontations experienced as online tutors of undergraduate courses. Each of the participants is presented below.

The online tutor 1 (T1), 49 years old, is graduated in Languages and Pedagogy and has a master´s in Education. With 26-year´s experience; since 2006, this educator was part of the faculty of the institution field of the research. At the time of the interview, T1 had nine hours for classes in the face-to-face courses of Pedagogy and Physical Education and 31 hours for teaching activities in the DE program. As an online tutor, T1 oriented disciplines of teacher education courses, especially Pedagogy. Tutoring had been performed for six years.

The online tutor 2 (T2), 44 years old, is graduated in Languages Portuguese/ Spanish and their respective literatures, besides having a master’s in Education. With 15-year´s experience in higher education, T2 started as an online tutor, in October 2015, in the institution field of the study. When this educator was interviewed, T2´s workload corresponded to 20 hours per week, with 15 hours for online tutoring in Languages Portuguese/ Spanish, as well as being the teacher responsible for the specific subjects of that foreign language. The remainder of that workload was intended for the presential university teaching as a teacher of reading and text production.

The online tutor 3 (T3), 64 years old, has been teaching for 45 years. In T3´s professional career, teaching and management are included in both basic and higher education. This educator is graduated in Languages Portuguese/ English and Pedagogy, besides holding a master´s and a doctorate in Linguistics. T3´s experience in online tutoring began in 2014, when the educator started working in the institution target of this research. With a workload of 15 hours a week, T3 dedicated 12 hours for online tutoring in Languages and Pedagogy, apart from being a teacher-responsible for some disciplines. Periodically, T3 was required as a proofreader of the written tests applied to candidates in the entrance exams of the institution.

The online tutor 4 (T4), 34 years old, holds a graduation, a bachelor and a master´s in Geography. With 10-year´s experience in teaching, T4 had been acting as an online tutor for seven years. Before, the educator had acted as a teacher in a presential undergraduate course in the institution field of the investigation in 2008 and in the final years of elementary school from 2008 to 2014. In the DE program under study, T4 is an online tutor in the courses of Geography, Biology, Pedagogy and History. T4´s workload was 20 hours a week, having activities as an online tutor and a responsible-teacher.

The online tutor 5 (T5), 36 years old, holds a degree in History with a doctorate in the same discipline. Teaching for 18 years, seven of them acting as an online tutor in the DE program under study. Prior to online teaching, T5 had already been a professor in higher education at a public higher education institution in the state of Minas Gerais. At the institution field of this research, T5´s total workload was 30 hours a week as an online tutor and a responsible-teacher in the History and Geography undergraduate courses.

These were the profiles of each interviewee, taking as reference their academic training and their teaching work fulfilled at the higher education institution at the time of the narratives’ concession. From the presential classroom experiences to expectations with the online classroom, the paths taken by these tutors in learning to teach distance-learning courses mediated by new technologies are presented.

THE CHALLENGES OF LEARNING HOW TO TEACH ONLINE

The access to digital technologies that allow interaction between subjects at different times and spaces has opened precedents for new ways of teaching and learning. One of them was the creation of the VLE, an electronic classroom, interactive, flexible and decentralized. In contrast to traditional educational practices, these particularities announce that, in online education, it is expected that teachers and students understand the need to develop attitudes that allow them to enjoy this experience. For this, the teacher should act as a mediator and a supporter of the learning process. In addition to disciplinary knowledge, other knowledge will be required of the online tutor in order to make the digital classroom a place where the student learns by participation, autonomy, dialogue and construction.

Thus, it was conducted an analysis of how the online tutors participating in this study have been developing competences, based on those ones presented in Table 1, that allow them to embrace online teaching specificities. The following subdivision was proposed for a better understanding of these competences; although, in the interviews, it is perceived that, in teaching practice, they are interconnected.

Social competence

Being an online teacher is to experience changes in the actions and relationships established between the subjects participating in the educational act in the digital classroom; especially for teachers accustomed to face-to-face teaching. As a social act, the teaching and learning process must be developed in an environment that fosters reception and interaction between those who teach and those who learn. Thus, T1´s narrative revealed how to be in the same time and space of the classroom is a reference for the teaching practice, since, without that, it is generated a strangeness in this educator´s acting in the online classroom:

In the common classroom, you plan the class, you enter, you are seeing your students. I really like to walk, to watch the environment. I do not know if it is because of my education, I was a teacher of basic school, a literacy teacher; then I feel the need to see, to look, to walk, to follow “body to body”, closer to my students. In distance education, that is my limitation, because the student is on the other side; I simply see the photo; but some of them do not even put a photo... (T1)

T1 indicated the physical absence of the student as an obstacle to be overcome in online teaching. According to this interviewee, the need to visualize the person who is the student could be supplied by a profile picture, which, according to Carneiro and Nascimento (2012), is a fundamental resource to establish the affective-social bond between the members of an online classroom; but, as T1 mentioned, not everyone inserts it.

In similar reports, T2 and T5 described how the body constitutes a reference for the development of pedagogical mediation from their experiences with the educational practice realized in the face-to-face classroom:

… you have the opportunity to look into the student’s eyes because the body speaks. The student says ... “Teacher, I get it.” But, you realize, through body language, that is not quite like that. By the image, by the face, you think... “No. Come here. Let me explain it to you again”. The student is more likely to have direct contact and you realize. (T2)

... the student may not say anything, but you see, by his face, whether he likes it or not, if he is assimilating. So, you have this ability to make the diagnosis of the proximal zone, where it is, where you can pull more, or have to go back. So, there’s all that there. In distance education, that’s harder. (T5)

The absence of the face-to-face contact with the student in the online classroom proved to be a factor of instability for these tutors, which is corroborated by Coelho and Tedesco (2017). The authors agree that the pedagogical mediation in the VLE is a challenge because of the loss of the body language elements in interaction mediated by technology and, since writing-based asynchronous communication tools predominate in most DE programs, distancing between interlocutors can be accentuated.

The reports showed that, from the experience of these teachers, oral and visual communication is the main means for teacher-student interaction in the face-to-face educational practice because of meanings expressed not only by verbal language, but also by non-verbal language. According to T2 and T5, the set represented by ‘said’ and ‘not said’ favors the teacher’s immediate perception of the student’s needs and reactions to what is presented in the pedagogical act, facilitating learning mediation.

However, when seeking new benchmarks for interpersonal relationship in the online classroom, the tutor-teacher must understand that the VLE is a space for the educational act in order to train professionals for the competent exercise of the chosen career and for the responsible citizenship in society. For that formative stage to represent not only a technical-scientific, but also a human growth, it is necessary to have affection, which welcomes and motivates the student to persist in a study mode that demands attitudes such as autonomy, discipline, punctuality and perseverance.

On the other hand, T4 pondered some difficulties regarding the expression of affectivity, despite the training received in the DE program so that the online tutors can be affectionate and spontaneous when dealing with the students:

... it is a big challenge; because if I send a ‘hug’ to the student, I do not know how he interprets it. If I write only ‘regards’, he may think I am being too cold. If I send a ‘hug’, he may think I’m being over affectionate ...[laughs] We try, but I, myself, end up being more formal. If I establish a dialogue, that is, not only the question - the student asks, I answer back and it ends there… If it becomes a dialogue, I end up having more tranquility in talking, even though it is written. Then, I feel more comfortable to send a ‘hug’ or a ‘good luck’ ... (T4)

This report exposed how the spatial-temporal gap in online written interactions, especially in asynchronous tools, could hinder relations and interactions in the VLE, either by the false impression of coldness or sympathy. According to T4´s perception, the approach between the online tutor and the student is facilitated with their “coexistence” in the electronic classroom. This is attested by Lima and Machado (2010), explaining that the contact between these actors narrows through dialogue, being the proximity evidenced by the use of more affective and informal language in written texts.

In turn, T5 expressed as follows his understanding of the exercise of the authority of the online tutor in educational practices in distance undergraduate courses:

Reflecting on this, I think it would be a question of proposing a reflection. Because the issue of our time is that you have access to a lot of information, but pieces of information do not necessarily become knowledge. A series of data, movies… but you don´t have the time to draw the consequences of that, in other words, the reflection. So, I guess ... That’s why I understand that to gain the respect of the student is not with a low mark, right? In the sense of the pedagogical authority, in the Freirean and dialogical sense... How do you achieve this? When you master the didactic material, when you propose more in-depth questions, so you get away from the common belief... And many students have the interest. So, you have to get out of the common belief, and for that you have to research. You do not have to stay in the magazine, or this or that, in the superficial, the talky-talk… So if this is your choice, I guess it does not add up at all. Or I´m wrong and I´d have to ask the students. But I believe it is with a problematization, deepening the reflection on a theme in the discipline. So I think it’s more in this reflective sense that you can get the student to listen to you and do not go searching the site on the side and listen to what you’re talking about. So it´s more like that. (T5)

This contradiction can reveal a learning process in the search for a path that allows this educator to teach in a dialogic way in the online classroom, which would correspond to the orientation of T5´s personal, academic, experiential and didactic-pedagogical culture (TARDIF, 2000). In this way, it is possible to assume the influence of the experiences of the face-to-face classroom in the online teaching practice. Nevertheless, the position of T5 is that the authority of the online tutor would be the result of his or her acting as a mediator of the knowledge construction, not as an arbiter of correct or wrong resolutions.

It can be admitted that online teaching has led these tutor-teachers to seek a framework that allows them to establish an authentic social bond with the students in mediating teaching and learning in the electronic classroom. Paths to the creation and the maintenance of such a link in an online academic community should be considered, since “[...] social interaction and sense of belonging in the VLE are considered essential factors for the construction of knowledge” (COELHO; TEDESCO, 2017, p. 613). It was evidenced by the analyzed statements that, instead of oral and visual communication, in the electronic classroom, the interaction between online tutors and students has been established through written text, as examined in the sequence.

Linguistic competence

In the search for new parameters of interpersonal relationship and knowledge construction in DE, students’ reading and writing skills appeared as the main reference used by these tutors in mediating the online pedagogical practice. In the impossibility of face-to-face contact, T3 answered that the means to know a student is:

By the textual production and by the answers. First, for the questions. I will use a thought of Rubem Alves, in which he made a paraphrase of the philosopher Wittgenstein. He said this: your questions reveal the lake where you went to quench your thirst. So, by the questions, by the doubts, you get to know your student. When he says... “How´s it going? Can you help me?” But there’s another one that says... “Good afternoon, teacher! How have you been? I have a question.” They are relationships with language, because language also defines you, creates your identity. (T3)

T3 relies on the expression of the students through verbal written language as a means of individualizing them. In pedagogical mediation, that practice can be corroborated by the conception of language as a place of interaction proposed by Koch (2002); according to which, the subject is a psychosocial being who imprints his identity to the acts of communication in which he participates. Thus, the perception of the world brought by the student when he enters a distance undergraduate course will be preponderant in the quality and depth of his academic reading and writing. For that, it is expected the student is be able to interact with the teaching materials in order to “[...] construct a coherent representation, activating previous knowledge and/ or drawing the possible conclusions for which the text points “(KOCH, 2002, p.18). When T3 alluded to the image created by the mentioned thinkers, the educator signaled that the complexity of the students’ questions in response to the study of the indicated texts can be used by the online tutor as a parameter for pedagogical intervention.

That report also referred to the linguistic competence to be demonstrated by the teacher, using it in the orientation of learning and promoting the understanding and production of written texts in order to mediate interpersonal relationships in the online classroom. In addition, according to Leite (2011), that intervention should contribute to the linguistic learning of the student so that he does not only explore the didactic materials being studied, but so that he can position himself before its contents, collaborating with the knowledge construction. In such a type of teacher/ student relationship, Koch (2010) reminds that the written text must be characterized, among others, as planned, elaborated and complete in order to avoid decontextualization before the time distance in the insertions made in the VLE, as punctuated by Saldanha (2012).

VLE language practices may be associated with another aspect to be considered by the tutor in online pedagogical mediation. The writing and reading skills have been parameters that reveal the referents of the student’s school culture. In addition to the diversity of previous school experiences, online tutors also reported on how they handle the needs of students who may be in different regions of a continental country, as shown below.

Intercultural competence

Presential education and online education represent specific school cultures. Whereas, in the first one, there are still traditional practices based on rigidity, homogenization and monologism; the second one is expected to be flexible, decentralized and interactive. Just as in the physical classroom, another variant to be considered in the online classroom concerns the cultural profile of the learners determined by age, gender, beliefs or territorial belonging, for example.

These issues were addressed in the teachers’ interviews, as it can be seen in T2´s testimony:

We must know that they are students from different regions of the country.3 Then, there is heterogeneity in every sense: culture, knowledge... There are some who have more knowledge than others. I have students who have lived in Spain; who have lived in Hispanic countries, who have a fluency in the language; and have others who can not speak Spanish. So it has to be a differentiated treatment because the students have a different degree of learning, different degrees of knowledge, culture, everything... We have to take care of the cultural issue in the way the pupil sees teaching-learning. Often, the learner is used the to face-to-face education; he does not know what DE is like.

The ways of relating to teaching and learning differ according to experiences related to regional context, cultural profile or educational modality. Thus, besides predicting distinct experiences in geographic and socioeconomic terms, the online tutor should consider that students can reach the digital education with different understandings of how it differs from the presential education. Another experience related to the cultural identities of students of DE courses was thus reported by T1:

When I had the opportunity to travel and teach at the different poles, I had the question of the student’s cultural identity with a little more precision. I could understand it in a more precise way. If I was in Juiz de Fora, I had a look that was different from when I was in Sergipe.[...] So, in the online classroom, I have an impression, but I do not have this data concretized as I had seeing and experiencing the reality of the students. Now, I see, I read, I understand the reading and writing of that student, the way he expresses... (T1)

In that DE program, there was a moment when the faculty went to the poles to accompany the students in face-to-face activities; which is no longer the case, especially after the inclusion of the VLE in their educational practices. According to the previous testimony, being with the students in their cultural reality represented the possibility of knowing them in their way of being, relating, living, expressing themselves. However, even if it is not foreseen to be physically present at the face-to-face poles with the students, it is necessary for the online tutor to find other ways to approach their cultural realities.

Thus, T1 has retaken the question of linguistic competence which, besides competing for the establishment of interpersonal ties and for the knowledge construction, can be a reference for the perception of the cultural identity of the students. Supporting the reading and writing practices for that purpose finds correspondence in Koch (2010), which points to human language as a way of revealing the constitution of identities and the representation of social roles.

The dimension of who their students are and what their needs are may relate to other competence required to conduct online teaching. In the fluidity of the digital classroom, it is necessary that the online tutor develops means of organizing and managing both the teaching and the administrative activities so that the tutorial work is conducted with due correction, punctuality and organization. In this regard, the participants of this study discussed their routines and workflows in the online classroom.

Tutorial competence

In the DE program under study, the tutorial competence of these teachers was manifested by the need to establish priorities and routines in the performance of their work. It was highlighted the attention that the interviewees give to the return of doubts or difficulties presented by the students in the study of the disciplines. In addition, it is part of the tutorial work the dispatch of messages with alerts about activity deadlines or the maintenance of a welcoming environment. Another action that proved to be important was the correction of the evaluation activities, whose results should be made available by the online tutor, according to the institutional term. Thus, the administration of the tutorial workflow has proved to be a measure to avoid the accumulation of activities that can delay the responses expected by the students.

Feedback elaboration has shown to be a significant and important part of the actions performed in the daily work of these online tutors. In the process of evaluating the activities of the students posted in the online classroom, the statement of T2 brought to the discussion aspects related to correction procedures and the time available for feedback and the result obtained by the undergradute student:

I take my time to correct the activities because I like to correct them. I like to use that yellow marker. Generally, I use the yellow marker when the word is wrong; and I also cross the wrong word out… Maybe, you will criticize me, but I do it. I put aside what is right, because sometimes there is no time to rewrite it. I try to show the mistakes that the student made, but also, trying to show that what he wrote is considered. What he built, I will consider. The point is: the level of knowledge; what the student is able to do... We need to have this; take this into account. I can´t want a pattern of response.[...] You need to consider what the student did, how he did it and score what you think is convenient, what is relevant, what you think you should score. But the student needs to feel that at least what he has built is important. (T2)

Another issue is the reference that the DE student has. That student thinks that you are there to serve him, that there are no other colleagues ... “I posted the question and, up to the moment, the teacher has not corrected it? How come?” He complains immediately. But I can´t tell him either ... “It is not just you!” I can´t say that. So, I have to find a solution... “Your question will be corrected by that date. Please, wait. Do not worry.” You have this dimension; the student does not. This is a big difference because, in the classroom, you can look at the student and say ... “I am assessing tests of five groups. Wait for the result of your test.” It is much easier to persuade the student. In distance education, you do not have that possibility. (T2)

When affirming “I like to correct the students´ activities,” it is possible to admit that T2 recognizes the need to indicate to the undergraduate what has been achieved and what should be reviewed in the presented answer. Despite the criticism apprehension, that online tutor demonstrated using the tools of text editors as teaching resources for intervention and guidance in student writing. In addition to the technological competence that allows to incorporate graphic resources of the VLE, such as colored highlights or griffins on words, aiding in the understanding regarding performance in a written activity; it is also necessary to pay attention to the didactic-pedagogical competence when defining what each of them indicates - correction already made by the online tutor or reformulation to be made by the student, for example.

As for the factor ‘time’, Abreu-e-Lima and Alves (2011) attest its importance in the elaboration and availability of the feedback for distance learning activities. Although the authors consider it crucial for the student to feel “heard”, they admit the difficulty in delimiting ideal time frames for the return of such evaluation. In the online classroom time, one of the obstacles faced by T2 is to deal with the undergraduates´ anxiety regarding the disclosure of academic performance. In addition, investigations conducted by Abreu-e-Lima and Alves (2011) indicated that from 60% to 70% of the work time of the online tutor is spent with feedback elaboration.

In the DE tutorial work, the evaluation of the academic activities done by the students is a pedagogical action that requires attention and care. Besides learning implications, it can influence the interpersonal relationship among the students´ group, as addressed by T1:

… I try to read the student´s text to have the vision of the whole. Then I return to that production. When I come back, if the text is good, I say that the text is coherent, very well-elaborated, very well organized; so I congratulate the student and highlight the positive points I perceived; the clear language... I already have my own “script” to avoid forgetting. Sometimes the feedback I give to a student is not the same as that one I give to another; this avoids the comparison between them... They can live in the same city or sometimes have a study group at the pole... (T1)

In order to be able to objectively position before questions related to the evaluation of the performance of the students, T1 revealed having a support instrument, of own creation, that assists in the elaboration of feedback to be sent to the undergraduates. What the interviewee called “script” can be understood as the set of criteria definition to be examined in the activity under evaluation. For Baldovinotti and Carlini (2010), another benefit of establishing parameters for correction is that they facilitate the review of the actions undertaken by the student when accomplishing the task, giving a more definite dimension of the ownership of his work.

Although they recognize the relevance of organizing a routine for online tutoring, it was reported that the workload might be insufficient to reach what the online tutor sets as a goal, being the continuity of work at home the alternative for the realization of what was intended. Another occurrence that may justify online tutoring outside the educational institution is the fact that, due to the workload contracted, some tutors fulfill the teaching hours in only a few days, and that distance can also lead to accumulation or waiting in the demands to be answered.

The habit or need to extend work beyond institutionalized time could be assessed, since, taking the tutoring context at the Open University of Brasil (UAB), Abreu-e-Lima and Alves (2011) argue that productivity increases when the tutor accesses the VLE daily, even for a short time. In research with teachers working in face-to-face teaching and distance teaching from an educational institution, Mill (2012) found that only 5.33% of them said they did not do online teacher work at home and 20% of those who worked in online teaching at home said doing it not to accumulate work. On these issues, the tutors declared:

Before the written questions, the undergraduate theses and the projects, which are many, I think it is a little easier to keep up with. But written questions, projects, theses and several doubts, I need to act more, I feel like it seems that I have to work the weekend to get it. (T1)

I see that distance education also makes you take things home. So, I access the computer at my house pretty much every day to keep an eye out for work. What I seek is not to accumulate; so every day I have a number of tasks that I propose myself to do. (T3)

With the support of the teaching institution, the tutor should develop tutorial competence so that the routine in online teaching allows attending the pedagogical and administrative issues, but also that the teacher can study the didactic materials to be mediated in the teaching and learning process in the VLE. The previous action will be fundamental for the development of the didactic-pedagogical competence in online teaching.

Didactic-pedagogical competence

The planning for activities related to online tutoring should foresee the knowledge and study of didactic materials to be mediated in a discipline. In the program under study, the presentation of the contents is based on required readings, commonly elaborated by the institution faculty; complementary readings, indicated by the responsible-teacher, usually electronic texts available in the VLE library or on the web; video lessons, usually produced by institution teams - teachers, audiovisual professionals, proofreaders etc. In addition to these, it is possible that the teacher responsible for the discipline indicates or elaborates complementary sources, such as films, songs, study schemes, abstracts, etc. In that regard, the teacher-tutors expressed themselves in the following way:

It is possible to have access to the teaching materials of a discipline, but not too early, because there is a period for the tutoring links to be released. When it happens, I go in the disciplines and start, at least, a general reading to have a notion... (T1)

As the reading materials are online, we have a virtual library and the books to support the students are there or I also have access to the physical book, which, if it is available, I can take home; if not, you have the library in the coordinator’s room. So, yes, we do have access to the materials. (T3)

About the possibility to access the teaching materials in advance... No. I am informed that I will be a tutor when the system is opened for me and the student. Usually, I access with the student. Unless you have worked with discipline before. (T4)

You ask a very good question, because this contact with the materials is fundamental - it´s necessary to know the material to give a good orientation, a good direction of the doubts. So I always try to talk to my colleagues, in the discussions, how important it is that this role of the teacher preparing the material is the online tutor, right? Because sometimes you take the tutoring of a material that you have not prepared; there is always this mismatch between the mastery of the material because you have to... look at the material to remove the doubt. While if you’re going to prepare the week, you lean over the material. (T5)

These tutors have shown that they are aware of the importance of interacting in advance with the teaching materials with which they will work. However, they also highlighted weaknesses in the organization of the DE system of their institution because it is not possible to study the material in advance, since they can be informed that they will orientate a specific discipline when it is already being made available to the students. In addition, there was no mention of the teacher-author’s role in the online tutor training in order to mediate the study of the elaborated material.

Additionally, the predominance of written texts as the main source of information was evidenced, since there was no mention of access to other materials, such as audiovisual texts. Mill (2009) emphasizes that DE courses can be based on print and/ or digital media, but the audiovisual text is still used as support for the written text, as well as in conventional on-campus educational practices. Thus, the linguistic competence of the tutor is restricted to the written language, when it could explore other languages supported by the VLE, such as the audiovisual text and hypermedia, aiming at pedagogical mediation.

The assessment of the student learning is another action related to the pedagogical mediation conducted by the online tutor, because it deals with the appropriation of the topics studied by the students. Thus, T3 stated how important is to intervene in the application of the content and in the use of the language. However, the interviewee revealed a marked difference in doing didactic-pedagogical mediation of content in the online classroom:

As you do not have a whiteboard, or black or green, to say ... “This construction is inadequate, because, in the standard language, there are some norms you will need when entering the labor market.” So, you have to write. I always try to make this game of working with the content, clarifying the question or returning to the student´s answer, but also alerting him to the matter of lexical choices, cohesion and coherence... “You repeated that word three times. You can replace the word “student” by the pronoun “he” or by the word “pupil”, writing a lighter text, easier to be read and more cohesive.” (T3)

The previous testimony revealed the search of that online tutor for new ways and means to mediate learning, because, now, it is not possible to rely on the support of chalk and blackboard to demonstrate to the student what to do or how to improve. T3´s strategy is to get the undergraduate to understand the question asked and then offer the evaluation of the answer presented. By saying “you have to write,” the tutor mentioned the competence of feedback elaboration.

In exemplifying how it would be the establishment of the dialogue with the student in the act of evaluation, that Portuguese language teacher revealed possible roles that pedagogical mediation can assume in online teaching. Instead of pointing out mistakes and right answers, T3 proposes to act as a reflexive guide, highlighting parts of the response to provoke reflection (the repetition of words); facilitator, by provoking the mobilization of studied concepts (pronoun / synonym / cohesion); and mediator, by demonstrating better alternatives for the student´s writing (ABREU-E-LIMA; ALVES, 2011).

Pedagogical mediation in distance university education requires specific teaching knowledge in terms of language, didactics, content or organization, for example; but it also depends on an elementary domain: the knowledge of the online platform where the teaching and learning process happens. The VLE, electronic classroom, demands an educator able to navigate through its tools, resources, tabs, icons, tutorials. The technological competence of the online tutor is, therefore, fundamental so that new technologies are used aiming at the educational act.

Technological competence

In a DE program, the digital technologies chosen to mediate its didactic-pedagogical proposal must be mastered from the technical perspective so that they are integrated into the teaching and learning process characteristic of the online education. Thus, among the experiences with the electronic classroom of the DE program under study, the tutors interviewed highlighted the following:

I find it easy to navigate the online classroom, because I have been following it from the beginning for many years.[...] As I am curious, I access and want to test. If I do not understand, I ask some teacher: “I did not understand, did you understand what it is necessary to do?”[...] the tools make it much easier. At first, because we do not know them, we make some mistakes. From the moment you perceive them, they help a lot, they collaborate with us. (T1)

In the beginning, it was not easy. Until you identify these tools and know how to use them, it is not easy. With the day to day, we are learning and we have these tools ... I evaluate them, at the moment, as good ones; I like them. (T2)

I had already had the experience at the FI, at the Federal Institute, when I arrived. Here, it is a classroom, the VLE. I think it is very well done because I did not find it difficult to navigate. I do not know if it is because I counted on the help of the whole team. You do not have many obstacles; even because we are close to the people who create it. So, you have this technical support. Whenever I need, I am near the room where they know all the modifications of the VLE. (T3)

I think the VLE is good, yeah… In terms of navigation, you´re talking about, right? Not content, right? I think it’s good. I think the current navigation is very clear; the disciplines within each classroom, it is well specified that distribution, the activities; I think that, in that sense, it got much better as time passed by. That part of the navigation, the design, that part has evolved. Because there is a counter-trend that we have to follow, but we can´t deal with it… That´s the hurry, right? The more you become didactic and self-intelligible, people are so accelerated and don´t have a minute to look right there. (T5)

Previous reports have shown the adaptation of each tutor to the online classroom. There were those who followed the institutional VLE since its construction, passing by those who experienced online teaching in the electronic classroom of another DE program, until who is starting in this mode of teaching. Between unfamiliarity and learning, the interviewees positively evaluated the VLE with which they work. It was also highlighted the need for autonomy to explore the possibilities of the new classroom and, in that action, the support of the online tutoring colleagues and the IT staff proved to be valid, which, according to Mill (2012), illustrates DE mediated by new technologies as a mode of collective teaching.

The competences for teaching in the digital classroom discussed from the experiences of the teachers participating in this study point to the need for diverse skills that allow them to deal with pedagogical mediation in the VLE for the students’ learning. For that reason, the online tutor should develop competence so that the undergraduate pupil studying via web can learn.

Learning competence

As in other formal education experiences, the online tutor is primarily responsible for leading the student to learning. But, in DE, being pedagogical mediation conducted with teachers and students in different times and spaces, that raises a worrying issue for undergraduate courses in that mode of education: high levels of evasion, since solitude can accompany students throughout their studies (SILVA, BRITO, 2013).

In order to deal with such an obstacle in pedagogical mediation, besides social knowledge for the reception and the affectivity, it must be associated knowledge that allow the online tutor to intervene in the difficulties that interfere with the students’ learning. In that sense, T3 signaled how social and learning competence can be demanded in the online classroom orientation: “You will realize who is in need of more resources, more support. Intellectual and emotional support. “

By accompanying the interactions and the manifestations of the students in the VLE, that interviewee showed how the online tutor´s sensitivity could direct to a teaching intervention that allows the undergraduate to overcome fragilities that hinder academic and personal formation. T4, in turn, reported how to pose before learners with difficulty to organize their time to devote themselves to distance learning:

I try to put myself in his place no matter how much he says ... “I have full-time job. I do not have time to study.” I do not think... “Wow! It is an absurd that the student wants to take a distance learning course if he does not have time to study.” I do not think like that. I think... “That student needs to be better informed. How can I talk to him without offending him?” I really do not know his reality. (T4)

The position of that online tutor is related to Tardif (2000), because, according to the author, before the incomprehension about dedication required to learn at a distance, T4 seeks to understand the personal characteristics of the students for their integration into the process of teaching and learning in online education.

It is a challenge for these teachers to develop their competence to identify and intervene, even at a distance, in the difficulties of the students that refer to reconciling personal and professional life to academic life, which may compromise the learning process in DE. In that sense, the pedagogical mediation of the tutor should enable students to develop their language, socio-cultural interaction, university study and technological mastery in accordance with characteristics desired by online education - flexibility, discipline, initiative, dialogue, collaboration.

CONCLUSION

The narratives of the five university teachers who moved from face-to-face teaching to online teaching revealed their experiences in the constitution of knowledge for the educational practice in undergraduate distance courses. Their testimonies allowed the reflection how time and space references of the electronic classroom demand specific postures and procedures for online pedagogical mediation.

For the participants of this study, one of the challenges in teaching via web is the lack of student corporeality, a factor that influences the teaching work both from the point of view of knowledge construction and interpersonal relationship. In pursuit of a university education for professional and human formation, the reading and the writing of the undergraduates proved to be the means by which these teachers are oriented to understand who these students are, what their learning needs are and what teaching strategies to address them.

From these interviewees´ experiences, online pedagogical mediation that promotes knowledge construction and learning is the one in which the online tutor masters the taught discipline, the educational technology used, the written language, the work organization and the approach to distance learning. In relation to the technological competence, none of them is a digital native, but it was not observed the interference of the teachers’ age regarding the incorporation of the new technologies to teaching. As a caveat, it was highlighted the concern about how to establish a dialogical online education in which the interaction and collaboration between teachers and students evidence quality learning. It was also possible to observe the need to create working conditions and remuneration that consider the need of the online tutor to access and interact in the VLE every day of the week, including Saturday and Sunday, to clarify students’ doubts.

The experience of these teachers in online pedagogical mediation leads them to exercise their leading role in making decisions regarding the undergraduates’ learning, such as the elaboration of evaluation guides or the initiative to seek peer support. That can be related to the process of building their professional identity in online education; although they act in a teaching group, they do not place themselves as repeaters or mere executors of a planning developed by another educator, but as teachers who have to contribute with the DE project from their personal, academic and professional history.

REFERENCES

ABREU-E-LIMA, D. M.; ALVES, M. N. O feedback e sua importância no processo de tutoria a distância. Pro-Posições, Campinas, v. 22, n. 2 (65), p. 189-205, maio/ago. 2011. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pp/v22n2/v22n2a13.pdf >. Acesso em:17 dez. 2017. [ Links ]

AMARO, R. Docência online na educação superior. 2015. 267 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2015. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/20664 >. Acesso em:16 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

ARRUDA, D. E. P. Dimensões da aula e das práticas pedagógicas na educação superior presencial e a distância. 2011. 147 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, 2011. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufu.br/bitstream/123456789/13863/1/d.pdf >. Acesso em:23 ago. 2016. [ Links ]

BALDOVINOTTI, N. J.; CARLINI, A. L. WebQuest. In: CARLINI, A. L.; TARCIA, R. M. L. 20% a distância: e agora?: orientações práticas para o uso de tecnologia de educação a distância no ensino presencial. São Paulo: Pearson Education do Brasil, 2010. p.142-160. [ Links ]

BELUCE, A. C.; OLIVEIRA, K. L. Escala de estratégias e motivação para aprendizagem em ambientes virtuais. Rev. Bras. Educ., Rio de Janeiro, v.21, n.66, p.593-610, jul./set. 2016. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-24782016000300593&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt >. Acesso em:04 set. 2016. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO, M. L. F.; NASCIMENTO, R. G. Dinâmicas de apresentação e integração do aluno virtual em cursos a distância. In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR A DISTÂNCIA, 9., 2012, Recife. Anais eletrônicos... Recife: ESUD, 2012. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://professor.ufrgs.br/sites/default/files/mara/files/viiiesud_dinamicasapresentacao_anais.pdf >. Acesso em: 21 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

CASTELLS, M. A sociedade em rede. 8. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1999. v.1. [ Links ]

COELHO, W. G.; TEDESCO, P. C. A. R. A percepção do outro no ambiente virtual de aprendizagem: presença social e suas implicações para Educação a Distância. Rev. Bras. Educ., Rio de Janeiro, v. 22, n. 70, p.609-624, jul./set. 2017. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/v22n70/1809-449X-rbedu-22-70-00609.pdf >. Acesso em: 05 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

FONSECA, S. G. Ser professor no Brasil: história oral de vida. Campinas: Papirus, 1997. [ Links ]

GARCIA, M. F. Prática do professor tutor na formação superior de professores a distância: criação e validação de um instrumento de pesquisa. 2013. 106 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2013. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.bibliotecadigital.unicamp.br/document/?code=000915250&fd=y >. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

KENSKI, V. M. Tecnologias e ensino presencial e a distância. 5. ed. Campinas: Papirus , 2008. [ Links ]

KOCH, I. G. V. A inter-ação pela linguagem. 11.ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2010. [ Links ]

KOCH, I. G. V. Desvendando os segredos do texto. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002. [ Links ]

LEITE, M. Q. Interação pela linguagem: o discurso do professor. In: ELIAS, V. M. (Org.). Ensino de língua portuguesa: oralidade, escrita, leitura. São Paulo: Contexto, 2011. p.55-66. [ Links ]

LÉVY, P. Cibercultura. São Paulo: Editora 34, 1999. [ Links ]

LIMA, C. S.; MACHADO, M. J. As letras falam: afetividade e escrita em cursos de Educação a Distância. In: SIMPÓSIO HIPERTEXTO E TECNOLOGIAS DA EDUCAÇÃO: redes sociais e aprendizagem, 3., 2010, Recife,2010. Anais eletrônicos... Recife: NEHTE, UFPE, Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://www.ufpe.br/nehte/simposio/anais/Anais-Hipertexto-2010/Catley-Santos&Michelle-Jordao.pdf >. Acesso em: 21 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

MEIHY, J. C. S. B. Manual de história oral. São Paulo: Loyola, 1998. [ Links ]

MEIHY, J. C. S. B. Canto de morte Kaiowá: história oral de vida. São Paulo: Loyola, 1991. [ Links ]

MILL, D. Docência virtual: uma visão crítica. Campinas: Papirus, 2012. [ Links ]

MILL, D Educação virtual e virtualidade digital: trabalho pedagógico na educação a distância na Idade Mídia. In: SOTO, U.; MAYRINK, M. F.; GREGOLIN, I. V. (Org.). Linguagem, educação e virtualidade [online]. São Paulo: Editora UNESP; São Paulo: Cultura Acadêmica, 2009. p.29-51. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://books.scielo.org/id/px29p/pdf/soto-9788579830174-03.pdf >. Acesso em:20 out. 2016. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, B. T. Do presencial-atual ao presencial-virtual: transposições do projeto ler e pensar. 2015. 328 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2015. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/158779 >. Acesso em:16 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

PANIAGO, M. C. L. Narrativas eclipsadas e ressignificadas de docentes e discentes sobre/na cibercultura. R. Educ. Públ., Cuiabá, v.25, n.59, p.382-395, maio/ago. 2016. [ Links ]

SALDANHA, L. Tutoria, linguagem e diálogo pedagógico na educação a distância. In: SIED, EnPED, 2012, São Carlos. Anais eletrônicos... São Carlos: UFSCAR, 2012. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://sistemas3.sead.ufscar.br/ojs1/index.php/sied/article/view/260/132 >. Acesso em:21 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

SANTOS, S. M. Saberes docentes na educação a distância no ensino superior. 2012. 197 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - PUCRS, Porto Alegre, 2012. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://tede2.pucrs.br/tede2/bitstream/tede/3724/1/438892.pdf >. Acesso em:16 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

SENO, W. P.; BELHOT, R. V. Delimitando a fronteira para a delimitação de competências para a capacitação de professores de engenharia para o ensino a distância. Gestão & Produção, São Carlos, v. 16, n. 3, p. 502-514, jul./set. 2009. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.scielo.br/pdf/gp/v16n3/v16n3a15.pdf >. Acesso em:09 abr. 2014. [ Links ]

SILVA, M.; BRITO, S. Docência online no ensino superior: saberes docentes e formação continuada. Educ. Foco, Juiz de Fora, v.18, n.1, p.105-126, mar./ jun. 2013. Disponível em:<http://www.ufjf.br/revistaedufoco/files/2014/06/texto-4.pdf>. Acesso em:08 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

SPÍNDOLA, M. C. P. Docência em educação a distância: o professor por um fio. 2010. 122 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2010. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.bdtd.uerj.br/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=2947 >. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

TARDIF, M. Saberes profissionais dos professores e conhecimentos universitários: elementos para uma epistemologia da prática profissional dos professores e suas consequências em relação à formação para o magistério. Rev. Bras. Educ., Rio de Janeiro, n.13, p.5-24, jan./abr.2000. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://anped.tempsite.ws/novo_portal/rbe/rbedigital/RBDE13/RBDE13_05_MAURICE_TARDIF.pdf >. Acesso em:14 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

1The teacher target of this study is the online teacher-tutor, according to the name adopted in the DE program of the institution field of research; although, throughout the text, variants of the term may be used for writing adequacy.

2The narratives were collected between June and August 2017, after approval of the research project by the Committee on Ethics in Research of the institutions involved.

Received: August 02, 2018; Accepted: November 22, 2018

texto em

texto em