Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.35 Belo Horizonte jan./dez 2019 Epub 08-Nov-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698193459

ARTICLE

CENTER X PERIPHERY RELATIONS: THE UNIVERSITY IN DEBATE

IUniversidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, Pato Branco, PR, Brasil.

IIUniversidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Ciências da Educação, Florianópolis, SC, Brasil.

This paper aims to approach the complexity of the center-periphery relationship within the context of the Latin American university, of the internationalization of Higher Education and of scientific knowledge. Approaching the issue is grounded on the concepts of science capital by Bourdieu; of center-periphery relationship, by Kreimer and of hegemonic rationality in Sousa Santos. The university is discussed as a space of reproduction and/or tensioning of rationality, facing new contexts, such as the internationalization / mercantilization of Higher Education and the international rankings dominated by institutions of mainstream countries. In this scenario, the knowledge/science produced in the periphery needs to restore the university as a counter-hegemonic space. Education, understood as a public good - in universities in Latin America - can be potent and strengthen counter-hegemonic policies and actions, seeking for a propositive insertion in the global reality.

Keywords: Center-Periphery; University; Latin America

Este artigo objetiva problematizar a complexidade da relação centro-periferia no contexto da universidade latino-americana, da internacionalização da Educação Superior e do conhecimento científico. A problemática busca sustentação nos conceitos de capital científico de Bourdieu; de relação centro-periferia, em Kreimer e de racionalidade hegemônica em Sousa Santos. Discute-se a universidade enquanto espaço de reprodução e/ou tensionamento da racionalidade, frente a novos contextos, como a internacionalização/mercantilização da Educação Superior e as classificações de rankings internacionais dominados por instituições de países centrais. Neste cenário, o conhecimento/ciência produzido na periferia precisa recuperar a universidade como espaço contra-hegemônico. A educação, compreendida como bem público - em universidades da América Latina - pode potencializar e fortalecer políticas e ações contra-hegemônicas, buscando uma inserção propositiva na realidade global.

Palavras-chave: Centro-Periferia; Universidade; América Latina

INTRODUCTION

This paper results from a broader and more comprehensive research effort named “Desafios da Internacionalização da Educação Superior Brasileira: universidades de classe mundial»3(Challenges for the Internationalization of Brazilian Higher Education: world-class universities). The focus and purpose intended here is to approach the issue of center-periphery relationship, bringing the university - both in relation to general aspects and in relation to some specific spaces built between and among Latin American universities - into the debate, taking into account the complexity and the new contours of this relationship, in relation to the process of internationalization of higher education and to scientific knowledge, as well as to the reproduction of this rationality as a way of maintaining well established hegemonic powers.

The debate and studies involving hegemonic and peripheral centers gained greater visibility in the context of the twentieth century, around the so-called globalized and developed world. The knowledge and the science that - starting from the modernity - integrate the mode of production, have become legitimized in the XX century as a field of dispute and power. On the other hand, the university as a millenary institution was inserted into different movements within this process and hence, has been assumed as a privileged locus to legitimize the hegemonic rationality and / or to tension it.

Universities - towards and within the hegemonic context of the relationships established by the capital - are privileged spaces of (intellectual) production and science. In the XXI century, the university rankings echo as another instrument of legitimation of the well established model that seeks to consolidate the hegemonic centers posed, therefore, as centers of reference. The rankings created international classifications and the denomination of Word Class University (WCU) to integrate the debate about the university.

What one can observe from the creation of rankings, is the exposure of the gap between the so-called hegemonic centers of knowledge and science (the North) and the so-called peripheral ones (the South). At the top of the rankings there are universities located in the countries of the North, while the presence of some universities of the South, such as the University of São Paulo (USP), can just be observed at intervals considerably below international visibility.

Based on that scenario, the discussion proposed by this paper sought for theoretical support in the concepts of science capital, by Bourdieu (1983); of science, by Kreimer (2009, 2011), especially as far as the reflections that the author establishes between what he called science produced in the periphery and peripheral science are concerned. The concepts of modern rationality and university were discussed based on Sousa Santos (1997, 2006and 2011). The documents supporting the discussion were: Conferência Regional sobre a Educação Superior na América Latina e no Caribe (Regional Conference on Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean) (CRES, 2008), Fórum Latino-Americano de Educação Superior (Latin American Forum on Higher Education) (FLAES, 2014), Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU, 2015) and Times Higher Education (THE, 2017), and Panorama de la educación 2015: Indicadores de la OCDE (Education Outlook 2015: OECD Indicators) (2015).

Finally, we made an effort to perceive, in some Latin American university movements, legitimate spaces of construction of reflecting upon and tensioning of the hegemonic model of unequal disputes. In this context, we understand that the university, in the process of production of knowledge and science, has been responsible for maintaining unequal and subordinate relations. It is, however, also a privileged locus for the universality established through the dialogue of knowledge.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF SCIENTIFIC AUTHORITY

The different knowledges that make up human rationality were forged in the relationship that the human kind established between itself and nature, in a deeply social and historically constituted process. The biological capacity of the human being to discern, think and make decisions develops in intense social interaction and history. In this process, among the different knowledge produced by mankind, scientific knowledge has been imposed since modernity as the one and only valid and officially accepted knowledge. “Science is today the officially privileged form of knowledge and its importance for the life of contemporary societies offers no contestation” (SOUSA SANTOS, 2006, p. 137).

Even assuming that knowledge does not necessarily have a hierarchy, the author points out that those who hold them to a greater extent also have social, political and cultural privileges. In this context, the power that this knowledge attracts leads its holders to the search for hegemony in relation to it, as well as to develop it more and more with the intention of remaining in such hegemonic domination. Hence Sousa Santos’s (2006, p. 137) statement that “knowledge, in its multiple forms, is not distributed evenly in society and tends to be less so the greater its epistemological privilege is.”

From the seventeenth century on, with the emergence of the values and concepts of modernity, scientific knowledge becomes central to the debate. From that moment on, it became a universally accepted and true knowledge, proposing itself beyond the comprehension of nature and society, becoming a privileged form of power. “The epistemological privilege claimed by modern science assumes that science is made in the world, but it is not made of the world” (SOUSA SANTOS, 2006, p. 138) Thus, in seeking to bring knowledge to a central position, Modern Science inaugurated a rationality in which (scientific) knowledge began to integrate the mode of production and, within this context, the disputes over that field. Like other social fields, it tends towards monopolization, hierarchization, class struggle, and disputes. For Bourdieu (1983, p. 1), “science is a social field like any other, with its relations of force and monopolies, its struggles and strategies, its interests and profits”.4 In this field, the struggle is for the social power brought about by the technical capacity and scientific competence, in order to put itself, and to maintain, as “scientific authority”. For that author, because it is a social field, it cannot be dissociated from the political dimension. In other words, social power comes from the authority acquired within a given group, in this case, a select group of scientists, in which investments are made to meet political, state, market, or group interests. This investment, in its turn, allows the scientist to gain in recognition among peers, a phenomenon treated by the author as “scientific profit”. In this way, epistemological conflicts are inseparable from political conflicts (BOURDIEU, 1983).

In this context, when one thinks of the contemporary dimensions of of debates and conflicts involving the internationalization of Higher Education, the theoretical constructs developed by Bourdieu - science capital and power - are fundamental and help establish some lenses of analysis. Thus, it is necessary to establish a critical reflection that moves away from the look of the “judgment of taste”, and is guided by the critical surveillance of understanding on what bases these intertwined sets of relations get constituted, structured and reproduced. Therefore, the first timely theoretical construct for the analysis about the internationalization of Higher Education, concerns capital and its species of power. For Bourdieu, getting involved in the arenas of the scientific field imply the understanding of sustained arrangements both in material and symbolic form linked to temporal or political power and to scientific power. Temporal political power assumes institutional and institutionalized power, linked to the relevant positions of scientific institutions, laboratories or strategic departments, privileged decision-making spaces, powers related to the means of production, such as financing, contracts, and careers. In an inter-relational way, the importance of the so-called scientific power is evidenced, evidenced mainly by the so-called “academic prestige”, which is based on representations of recognition with peers or segments and collegiate already recognized by the academy (BOURDIEU, 2003). As a result, understanding aspects of the hegemonic rationality of internationalization - especially when oriented by criteria of classification, recognition and reputation, materially and symbolically established by the rankings - allow to consider the bricolage of the performances in institutional dimensions, but also on individual grounds that consubstantiate university capital. Such capital is obtained and maintained by occupying positions that have repercussions in the domain of other positions and of their occupants, by institutional processes of control such as the reproduction of the teaching staff and of those who have authority, the political implications about the movements around the student body, ruled by relationships of diffuse and prolonged dependence (BOURDIEU, 2008).

As the main repercussion for the construction of scientific knowledge, what comes to integrate the agenda, is the imposition of a definition of science that is in alignment with the interests of those who try to impose it. So this definition, not only happens to be, but is also integral part of the game. “The dominant ones are those who are able to impose a definition of science according to which the most perfect achievement consists in having, being and doing what they have, are and do”5 (BOURDIEU, 1983, p. 7). Once the domain is obtained, it is up to the dominators to maintain it, since they dictate the rules of the game, including as far as the hierarchization of the knowledge as well is concerned.

Hegemony is also established among researchers, since scientific authority is not a cumulative, transferable capital and can generate further capital. The more reputation the researcher has, the more funds he or she will earn, the better students he or she will attract, the easier access to grants, scholarships, awards, invitations, publications he or she will have (BOURDIEU, 1983). This hegemonic logic, both among researchers, sometimes within the same institution, and between and among institutions and even countries, tends to perpetuate itself, making it difficult to compete between dominant and dominated, tending to a typical relationship between center (North) vs. periphery (South).6 Therefore, two options are left for the dominated, or novices. One is the succession strategy, in which one chooses the security of the established system, having limited career and innovations. The other is the strategy of subversion, submitting to risks and difficulties to obtain financing, and seeking for innovation that can subvert the dominant legitimacy. In this case, in addition to having the whole logic of the system against them, profits are only assured to the holders of the monopoly of legitimacy.

The tensions in the contexts of science, from within a local institution, extending to the global spheres, show that the search for recognition and notoriety goes hand in hand with the disputes and interests of the (capitalist) mode of production. To put it another way, scientific authority, as reported by Bourdieu (1983), is sought by researchers, proportionally to the political and economic interests demonstrated by institutions and governments of central countries, while the peripheral countries remain with the role of coadjuvants in the development model of contemporary science.

In this context, one can perceive that science has become central to the maintenance of hegemonic rationality. A rationality that privileges exclusions, inequalities, to the detriment of political and financial support. However, if we understand this rationality as “one” (among others) it is possible to recognize the space of contradiction, tension, and multiple possibilities that the human capacity for production is capable of. The simplification, the single thought, the absence of contradiction, do not characterize what is meant by human, which is, in essence, complex, diverse and singular. These, then, are characteristics that we must seek to construct when we claim for scientific authority. To exclude such characteristics out of the process of making science is, of course, to de-characterize it, to dehumanize it.

THE RELATIONSHIP CENTER (NORTH) X PERIPHERY (SOUTH): THE ROLE OF THE UNIVERSITY

The dispute and the maintenance of scientific and technological hegemony by so-called central countries, or the North, especially between Europe and the United States, on the one hand, stir up tensions between these countries and on the other, seem to define the strategic role of peripheral centers. At the center of the hegemonic disputes of capital, science has a privileged place, and in this process technical and technological advances in all fields of knowledge are conceived and developed in a supposedly neutral and universal scientific field.

It is necessary to tension this hegemonic field, understanding it as non-neutral and universal. On the contrary, it is a knowledge that carries from its genesis, disputes of power of every nature and in that supposedly established order, is the knowledge produced in the periphery (South).

Kreimer (2009; 2011) brings to the discussion the idea of science from the periphery and peripheral science and helps us understand the stages of science development in Latin America. This concept allows us to perceive that the distance to be covered is still great, so as to get closer to central countries.

The extreme differences between central and peripheral countries are fueled by a supposedly universalizing and neutral knowledge model. And the so-called global society seeks to build the idea of a global citizenship in which it seems to exclude the human, ignoring concepts such as solidarity and inclusion. What we perceive in that respect, is the construction of extreme ditches between hegemonic and peripheral centers.

It is necessary to tension these concepts of knowledge and science to break with the idea of universalism. Kreimer (2009, p. 18) claims that “If we assume that science is something universal, and that it is indifferent to the social spaces where it is generated, it would not make any sense to think that in each country, in each context, science is different”.7 Likewise, Sousa Santos (2006) understands universalism as abstract, in denial of differences and prioritizing a supposedly valid knowledge. For the author, this context could be valid in the early twentieth century, when Europe was the center of knowledge in the world. Nowadays, however, there is a confrontation with an epistemological, ontological and cultural diversity. Nevertheless, although there is no longer the exclusion of the colonies of that time, what one observes nowadays is a domination characterized by hegemonic rationality that limits access to knowledge and, consequently, the development of peripheral countries.

Contrary to universalism, globalization is the expression of a hierarchy between the center and periphery of the world system in a context in which the invisibility of the colonies to be “taken care of” by the center gave rise to the proliferation of state and non-state actors, constituted in the context of unequal relations between the center and the periphery, between the global North and the global South, between included and excluded. (SOUSA SANTOS, 2006, p 144).8

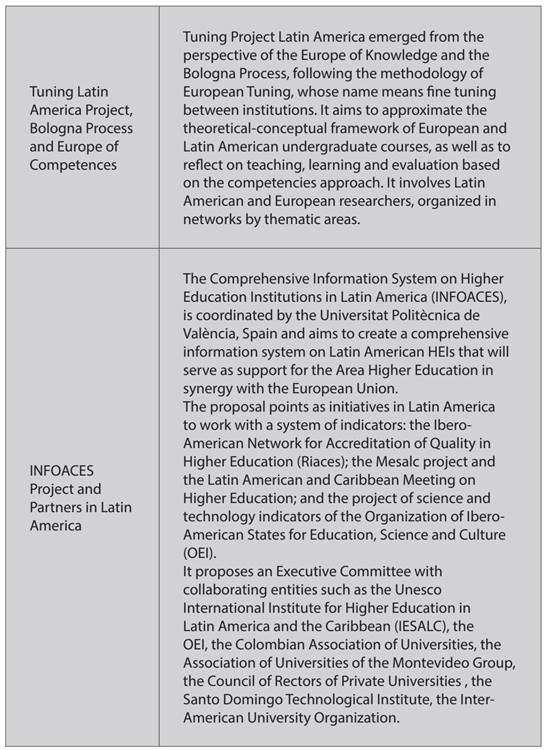

The box below seeks to synthesize Kreimer’s (2011) description of the institutionalization and development of Modern Science in Latin America, which happens, according to the author, in principle, in three stages.

Source: Adapted from Kreimer (2011).

BOX 1 Stages of internationalization of Science in Latin America

For the author, it is after these three stages, however, that one sees the most radical change in the relations between and among researchers from Latin America and Europe. The “fourth stage” is characterized by a new international division of scientific work, in which the formalization of negotiations reflects a “trend of collaborative relations” with the emergence of “mega-networks”. These are established with the participation of up to 500 researchers in “broad research regions” at the international level, but hold to Latin American researchers solely a subordinate integration.

We could see a paradox here: elite researchers from “non-hegemonic” countries are increasingly invited to participate in international consortia, but their access conditions are increasingly restricted and negotiation margins tend to be minimal (KREIMER, 2011, p. 56).9

While it may seem that there is a “democratization” of research, it is clear, according to the author, the dispute for global hegemony of science and technology between Europe and the United States. In order to conquer and maintain such hegemony, in addition to concentrating resources on a limited number of “knowledge blocks” that fit their interest, hegemonic countries have the participation of researchers located in peripheral countries, who are responsible for routine activities, although of high complexity, but without effective participation in the formulation of research agendas. The incentive for these researchers comes not only due to research funding, but also for participation in international publications and for leadership and prestige acquired locally. Hence, the relevance of these research initiatives for the local community is questioned, since local issues are not the subject of the agendas previously formulated by the hegemonic countries (KREIMER, 2011). The author also presents two approaches to science in Latin America: science in the periphery and peripheral science. The first is generated by local reasons, causes and cultures, showing that there is scientific excellence in the periphery, although it is relatively less common when compared to the central countries; while the second one refers to the specific characteristics of science in these countries, with their difficulties in creating new knowledge, with a focus on rather social issues, besides the difficulty of cohesion of their institutions (KREIMER, 2009). It is, therefore, from another point of view, which refers to “concrete traditions” which, more than abstract rules or values, govern science as “laws of life”, in which science defines rationalities. These traditions cause rationality to be maintained through new generations of scientists joining it. However, it is neither independent of the context in which it develops, nor of the sociocultural dimensions, of other significant actors, of resources, of politics, and so on. Many peripheral countries follow traditions that are not theirs, which belong to others.

There is a great distance to be covered before the periphery constitutes itself as a central and singular space. However, besides the distance per se, there are the difficulties encountered along the way, such as the lack of structure in the peripheral countries, as well as political and bureaucratic issues that collaborate even more to maintain it (KREIMER, 2009). On the other hand, the central countries are working on a process of feedback of their hegemony. As an intersection, the difficulties encountered in the relations involving science and technology between the central and peripheral countries and which extend to their universities, within which research is inserted as one of their pillars, alongside education and outreach. In this context, there are tensions, crises, competitiveness, commodification of science, but it is also the space for contradiction, for constructing different perspectives and possibilities of tensioning the established model.

Throughout the construction of its history, the university has been facing crises and challenges. However, according to Sousa Santos (2011), in this scenario the university may not be prepared to face them. For the author, the university is situated among the most varied social demands and the increasing restrictions imposed by the State itself. This situation is due to the three crises faced by the universities - crisis of hegemony, crisis of legitimacy and institutional crisis. It is important to point out that the emergence of these crises occurs from the 1960s on, when the main functions of universities become “research, teaching and outreach,” thus changing its assumed purposes previously described by Ortega y Gasset (1999, p.70) as: “1st) transmission of culture. 2nd) teaching of the professions. 3rd) scientific research and training of new men of science “. In 1987, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) assigned new functions to universities, many of which were incompatible or contradictory, according to Sousa Santos (2011), making it even more difficult to manage these tensions.

My analysis focused on public universities. It showed that the university, far from being able to solve its crises, had been managing them in such a way as to prevent them from deepening uncontrollably [...]. It was a reactive action, with an acritical incorporation of external social and institutional logics (dependent) and with no perspectives in the medium or long term (immediatist)10 (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011, p. 14).

In peripheral countries, the financial crisis induced by the neoliberal model, not only influenced the university’s loss of priority as a public good, but also led to the loss of priority of social policies, such as education, health and social security. In this context, the moment of institutional weaknesses could be convenient to debate and implement reforms in the political-pedagogical programs of public universities. Instead, these weaknesses “were declared insurmountable and used to justify the widespread opening of the university public good to commercial exploitation” (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011, p.18).

The process of “commoditization of the university”, at first with the expansion and consolidation of the national university marketplace, followed by the emergence of the “transnational market for higher and university education” was seen by the World Bank and the World Trade Organization as “the global solution of the problems of education “(SOUSA SANTOS, 2011, pp. 19-20). In this scenario, the public university is induced to at least contribute for the promotion of its self-maintenance with the generation of its own revenues.

In Europe where the university system is almost entirely public, the public university has generally been able to reduce the scope of decapitalization while developing the capacity to generate its own revenues through the market. The success of this strategy depends to a large extent on the power of the public university and its political allies to prevent the significant emergence of the private university market. [...] In the United States, where private universities are at the top of the hierarchy, public universities have been led to seek for alternative sources of funding from foundations, from the market and by raising tuition costs. (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011, p.23).11

In peripheral or semi-peripheral countries, the reality is much more difficult when it comes to raising non-public funding sources. Brazil is a typical example, following the logic defended by the World Bank with limitations of public investments in universities and expansion of the university market. At the same time, the implantation of “business” models such as cost reduction per student, pressure on teachers’ salaries and the end of free public education is sought. In the World Bank’s view, opening up education to the global market would solve the “problems” of the area in these countries. The Bank also foresees an increase in the use of online pedagogical technologies, which would reduce the teaching role in the classroom (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011).

Another significant factor, especially with regard to Brazilian federal universities, concerns the orientations around a new typology of knowledge produced. Silva Junior (2017, p. 35), when considering the influences of the movements of the American university towards Brazilian universities, also mediated by internationalization, alerts to an assumption of the production of alienated scientific knowledge, conceived as “raw material to become products, public or private services, trademarks, patents and licenses for university foundations.“

In addition, one point that seems to have great destabilizing power in universities is the fact that the public university and the educational system itself have ceased to be part of a national project in their countries. These projects aimed at the development and modernization of the nation, seeking to unite the society around them. “In the best moments, academic freedom and university autonomy were an integral part of such projects” (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011, 45). The country project, as described by Sousa Santos, with broad social participation, contemplating educational and university reforms, focusing on the national and social interest, directed to the thoughtfully planned insertion in the global process, is a great obstacle to the interests of the neoliberal globalization. In the Brazilian context, this perspective is supported by the construction of a social imaginary of inefficiency of the federal public university, which would be healed by economic demand as a motto and research guideline. Thus, the university is not linked to a project of nation, but to an institutional identity that ends up commoditizing the public space. It is interesting to note in this panorama how the very idea of internationalization referred to transnational organizations and at home modalities contribute to the idea that national sovereignty and State are not only endangered but also reconfigured. On the other hand, the modus operandi also of the public policy would be in a convergence of the academic-scientific, technical and pedagogical organization with a view to the insertion of Brazil in a world system and competitive by markets (SILVA JUNIOR, 2017). These movements are evidenced in the analyzes of Sousa Santos, (2011, p. 48):

The university will not leave the tunnel between the past and the future it is in until project the country is rebuilt. In fact, this is precisely what is happening in the central countries. The global universities of the USA, Australia and New Zealand are acting within the framework of national projects that have the world as a space for action.12

The author also poses that universities need to adapt to the emergence of a new model of knowledge. For Sousa Santos (2011), during the 20th century, university knowledge was disciplinary, relatively decontextualized, the researchers determined the scientific problems to be studied, their relevance and methodology. It was a homogeneous and hierarchical knowledge that was isolated from every other knowledge and could or could not have applicability to society. This “university” model gives rise to a new model, the “multidisciplinary knowledge” which, in turn, is contextual and transdisciplinary, having as principle its practical application, since the initiative for the formulation of the problem arises from shared interests among researchers and users. Thus, “society ceases to be an object of the interpellations of science to become a subject of interpellations to science (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011, p. 42).

This new model has occurred more frequently in central countries and in a few semi-peripheral ones, more consistently in university-industry partnerships, becoming commoditized knowledge. But there have also been cases of cooperative and supportive implementation through partnerships with trade unions, non-governmental organizations, social movements and vulnerable social groups, as well as popular and other critical and active citizen groups (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011).

Either inserted or trying to get inserted in this new globalized reality, in which “analysts agree in pointing out that globalization is a consequence of the opening and deregulation of markets, the diffusion of information technologies, electronic communication and the financial integration of markets” (RODRIGUEZ e MARTINS; 2007, p. 66), the Latin American countries seek to adapt to the global capitalist demands, placing on the universities a great expectation of contribution to this endeavor.

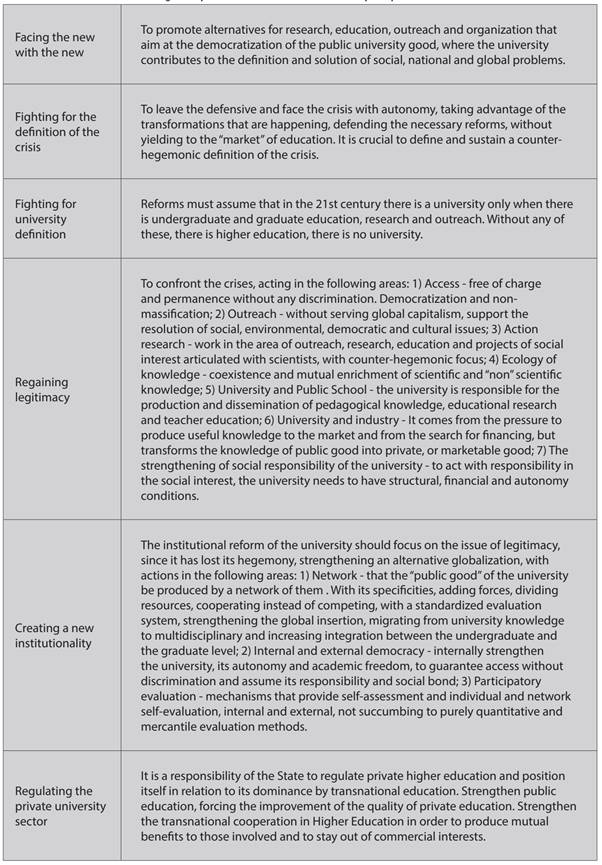

For Sousa Santos (2011), globalization, as of its current situation, enhances the impact of crises upon the university. “The only effective and emancipatory way to confront neoliberal globalization is to counteract an alternative globalization, a counter-hegemonic globalization” (SOUSA SANTOS, 2011, p.50). The university has to face the pressures of this global rationality as a public good that it indeed is, based on and grounding a national project, whose protagonists are the politically organized society, the public university itself and the State. In this context, the author indicates six guiding principles for the success of such an attempt and the box below seeks to synthesize the principles listed by Sousa Santos (2011).

Source: Adapted from Sousa Santos (2011).

BOX 2 Guiding Principles of the Democratic and Emancipatory Reform of the University

Leite e Genro (2012) point out that the XXI Century has brought a new epistemology that has taken universities to follow the track of global and international patrhs. The reforms of the Latin American higher education systems, according to the authors, have been key to determine those new paths in the 1990s. Those reforms stress terms such as quality, evaluation and accreditation within the university life, with impacts in terms of consequences in improving access and enrollment in the private HEI network; tuition fees, payroll differentiation among faculty; merit pay oriented systems; and submission of public policies to the recommendations of international funding organisms.

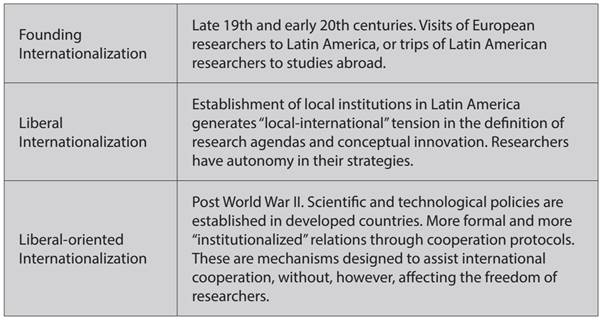

Education then becomes a market niche exploited with high financial returns at the global level, where peripheral and semi-peripheral countries are seen as potential markets. In this sense, the authors propose the denunciation of a post-neoliberalism, in which a new imperialism is constituted, having the Europe of knowledge as hegemonic center. The European community has used, in particular, the Bologna Process to implement an international education policy on an European standard. Latin America and the Caribbean, despite attempts by Latin American institutions and higher education institutions to resist them, are at the center of this project, for example, in the Common Higher Education Area formed by Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union (ALCUE). It aims to generate lasting links between Latin America and the Caribbean and the European Union, although it seems to be more focused on emerging economies such as Brazil, Chile and Mexico (LEITE and GENRO, 2012).

In addition to the ALCUE, built with Tuning Latin America, and aiming to resemble Latin American curricula to Europeans, which would facilitate student exchange and mobility, other signs are presented by the authors, such as the introduction of curricular competencies that aim to facilitate standardization quality, training and evaluation, as well as the standardization of indicators. “The standards would be suggested by Infoaces studies, which is associated with the Map of Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (Mesalc), IESALC / Unesco’s program to ‘map’ the reality of Latin American HEIs” (LEITE and GENRO, 2012, 31). Mesalc was intended to challenge the world rankings, but in practice it should collect and disseminate data from Latin American HEIs that could be useful to European intentions.

Within the relationship between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean, Leite and Genro (2012), argue that, besides the Eorupean Union itself, the main global players are ALCUE, UNESCO, IESALC/UNESCO and the World Bank. UNESCO has the role of guiding and disseminating educational standards, but has demonstrated “close links with the diffusion of the Bologna Process and Tuning”, by chancelling European standards of higher education as the ideals to be followed in all countries (LEITE and GENRO, 2012, p. 43). In turn, the World Bank is responsible for the initiative of the Global Initiative for Quality Assurance Capacity (GIQAC), which funds HEIs quality assurance practices (QA). UNESCO is part of the board of directors of GIQAC, therefore participates in the decisions on funding for higher education evaluation actions. GIQAC also provides support and technical assistance in the development of evaluation systems, personnel training, analysis and reporting of quality systems (LEITE and GENRO, 2012).

It can be inferred that there are connections between those actors, even with the acknowledgement of a certain hierarchy. On the foreground are the global science, culture and education agencies (Unesco, Iesalc), followed by agencies of the global political world (European Union, OECD) and their partners. On the background one finds agency accreditation agencies, such as the International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education, with agencies or institutions producing prestigious international rankings at their side. At a lower level, there are accreditation agencies that bring together other Latin American accreditors, such as Riaces and the Network of National Agencies for Accreditation. Down below, the national evaluation agencies of the different countries - the National Commission for the Evaluation of Higher Education, the National Commission for University Evaluation (Capes and Inep) and others. And absorbed by this whole structure, there are the universities (LEITE and GENRO, 2012). For Silva Junior (2017), the actions of such organizations, especially in the case of CAPES in Brazil, through their central role in the construction of criteria of excellence and the assignment of quality seals end up producing institutional stratification forms aligned with the idea of the commercial impact of knowledge as an applicable and profitable raw material, even having repercussions on the educational trajectories of learners (education length, technical education courses, evaluation mechanisms), for example.

Within this context, not only Latin America but also countries from other continents, especially the peripheral and semiperipheral ones, to the detriment of their culture, roots, values and history, adopt the European norms, based on liberal principles, with a utilitarian strand, as a standard model of evaluation and accreditation for their HEIs, with the consent of UNESCO. For Leite and Genro (2012, p.55) this situation constitutes “the gateway to the new imperialism”.

In the same way, within this global competitive trend, the international evaluation rankings of higher education institutions are becoming increasingly important in the international higher education agenda. By intensifying the competition between HEIs, they intensify the commodification of education and highlight a central and centralized hegemony in central countries. Their measurement goes beyond the HEIs programs, “they deal with a commodity called knowledge, the knowledge economy, its production and dissemination ... they measure the knowledge that a country produces” (LEITE and GENRO, 2012, p. 74).

The authors present three HEI models that emerge from the traditional model and reproduce the evaluations, accreditations and positioning before the rankings.

Source: Adapted from Leite e Genro (2012)

QUADRO 4 Principal models of HEIS according to generalist quality assurance (QA) indicators

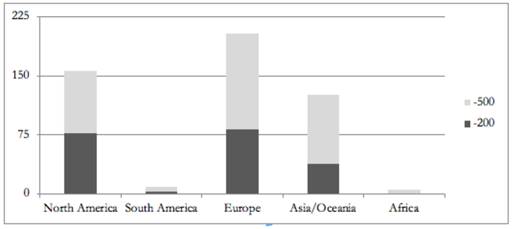

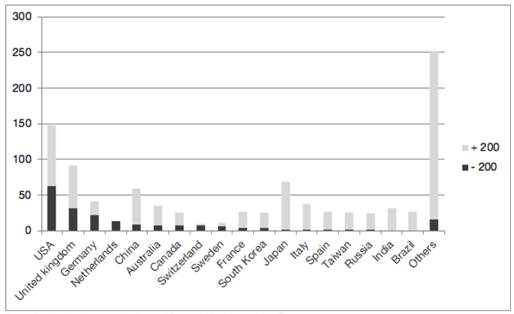

The three models describe the current reality experienced by the universities and converge to the hegemonic global tendency, characterized by a capitalist mercantile process. The public university must get inserted in such a context, seeking to recover its legitimacy and autonomy. In this context, rankings are a global reality. Its graphics highlight the so-called world-class universities and help reflect upon the issue. The Times Higher Education -World University Ranking - THE, one of the most prestigious worldwide is presented (graphs 1 and 2).

Source:Adapted from THE - World University Ranking 2016-2017 (2017).

CHART 1 Principal countries in the THE 2016-2017 ranking

The hegemony of the institutions of central countries is shown in the figures, making it clear how difficult it is for Latin American HEIs to be part of the so-called World-Class Universities. The THE ranking lists the 980 “best” universities in the world. The judgment is made based on what THE considers as fundamental missions of the university: teaching, research, transfer of knowledge and international perspectives. The calculations are audited by an independent specialist company. There are 79 countries, but the institutions listed represent only 5% of the world’s HEIs. The best ranked university was Oxford - United Kingdom, followed by the California Institute of Technology - USA. These two countries maintain - as a rule - the hegemony in the ranking. The US has 148 IES in the ranking, 63 of which among the best two hundred ranked. The UK has 91 HEIs, with 32 out of the 200 best ranked. European countries such as France, Italy and Spain have lost ground, while Asian HEIs have risen with 289 universities included, with 19 of them among the top 200 (THE, 2017).

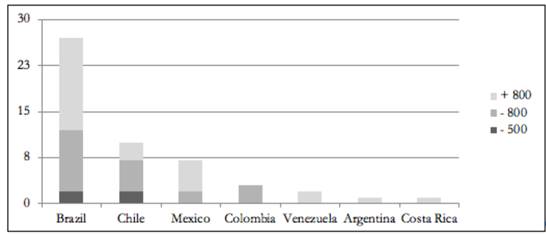

Source: Adapted from THE - World University Ranking 2016-2017 (2017).

CHART 2 Latin American Universities - Ranking Times - THE

Latin America continues to have very few significant results regarding the criteria established by the international rankings, with only 51 institutions represented in Graph 2, of which only four are among the top 500: the University of São Paulo (USP) and the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), both Brazilian universities and Federico Santa María Technical University and Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, both from Chile; there are 20 Latin American HEIs placed between the five hundred and eight hundred positions, and another 27 that rank higher than eight hundred.

Another well known and highly reputed ranking worldwide is the Academic Ranking of World Universities - ARWU, organized by Shanghai Jiao Tong University. ARWU brings the five hundred “best” universities in the world.

Although its methodology uses different indicators, this ranking does not present significant differences in relation to THE. European and North American hegemony remains with 137 US HEIs, of which 71 are among the 200 best, followed by the United Kingdom with 37 HEIs, 21 of which are among the 200 best. Asia and Oceania are favorably portrayed, but Africa and Latin America still show very few significant numbers. The Latin American HEIs are only nine, six of which are in Brazil. Out of those nine, three are among the two hundred best: University of São Paulo, National Autonomous University of Mexico and University of Buenos Aires (ARWU, 2015).

The rankings have been serving as the basis for choosing the destination of many students from around the world in search of an international background. Central countries and their HEI institutions have realized this trend since the end of the Cold War and have been investing on it, opening their doors to international students and “exporting” educational services, including through distance education.

According to Keeley (2013), the US alone generated revenues of $ 14.5 billion in 2006 and 2007 in this “market.” Like other core countries, the US focuses on attracting and retaining foreign students. An example of this is the annual reserve of 20,000 visas for immigrants considered to be highly qualified. This trend is confirmed by OECD information that many countries are relaxing their policies to encourage the coming and stay of these students. This is the case in Canada and Australia, that allow foreign students to stay in the country for a few years after completing their studies to seek employment in the area in which they have qualified.

The report “Panorama de la educación 2015: Indicadores de la OCDE [OECD Education Outlook 2015: OECD Indicators”] (OECD, 2015) informs that in 2013 more than four million students enrolled in higher education outside their countries. These are called “international students”, that is, they leave their countries for the specific purpose of studying in another country. In 2013, the United States received 19% of these, followed by the United Kingdom, which received 10%, Australia and France, 6% each, Germany, 5%, Canada and Japan, 3%, while Latin America, as a whole, received only 2%. More than half of these international students come from Asia, followed by Europe with 25%, Africa with 8%, Latin America/Caribbean with 5%, North America with 3% and Oceania with 1%. OECD member countries receive 73% of all international students, with seven out of ten of these students coming from non-OECD countries.

In relation to the preferred destinations of Latin American students, preference was shown for Spain (48.9%), followed by Portugal (36%). In relation to the Brazilian students mentioned in the report, 31.9% were in the USA, 14.6% in Portugal and 11.7% in France (OECD, 2015).

The report points out, among other information on education, that the average investment in the entire period of their higher education program in OECD countries is US $ 15,028 per student, while in Latin American countries, members or affiliated with OECD, the average values are: Brazil - US $ 10,455; Chile - US $ 7,960; Colombia - US $ 5,183; and in Mexico - US $ 8,115.

The number of publications is another widely used way to rank a HEI. Central countries take advantage because the most renowned journals usually publish in English. The Nature Index (2016), one of the most respected scientific publications in the world, lists the countries that published most articles in the year 2015. The United States, as in previous years, leads with 26,677 articles, followed by China with 9,673, Germany, with 9,157, UK, with 8,395 and other core countries following. Brazil, the first Latin American country to appear on the list, ranks 24th with 993 articles, with Chile in 31st place, with 1,030, Argentina in 33rd, with 409, Mexico in 34th, with Colombia 504, in 48th, with 221 articles. It is important to clarify that it is not the absolute amount of articles that determines the classification but rather the weighted counting fraction (WFC), which considers the percentage of authors and institutions of the countries and also makes some corrections in the weights of articles of astronomy and astrophysics, due to the large number of publications.

Bearing this panorama in mind, it is necessary to highlight the productivist perspective that transversally reinforces the relationship of political, institutional capital and academic prestige. In this context, publications have become “marketable” products in a material and symbolic sense relevant to scientific fields, as Silva Junior (2017: 87) points out:

The publications have become goods produced by an editorial industry that is configured as a monopoly on the sale of copyrights. Worldwide, many universities sell their teachers’ productions in this market. Universities sell copyrights of productions by their professional researchers. Researchers receive additional wages by selling their copyrights for reasonable amounts to the universities in which they work. On the other hand, publications run in many areas of knowledge, such as pharmaceuticals, technology areas, and mathematics, only after they become a patent or after a mathematical equation has become a financial product on Wall Street.13

However, the data presented are an evidence of the quantitative growth of higher education in Latin America. Parallel to this growth we also observe actions that we consider counter-hegemonic movements. This is the case, for example, of the Regional Conference on Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (CRES 2008), held in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, which pointed out that it is essential to maintain high-quality tertiary education as a social public good, allowing for equal access to all, besides condemning the policies of commodification and privatization of education and defend cultural diversity and interculturality as central premises in the pedagogical project of higher education institutions.

Another action that we identified in this same direction was the Latin American Forum of Higher Education (FLAES), held in Foz do Iguaçu in 2014. The objective of the event was to discuss Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, especially with regard to the accomplishment of the demands for changes and for personal and social development of the region, from some fundamental axes in particular:

the quality of higher education associated with relevance, equity and universality; higher education as a social public good; the inseparability between acquisition, construction and application of knowledge and the construction of ethical values; autonomy and inclusion in institutions of higher education; and institutional and social integration in national, regional and international contexts (FLAES, 2014, p. 1).14

Among the conclusions of the meeting, it is important to highlight the importance of regional integration as an alternative to the Latin American and Caribbean countries to face the asymmetries of global economic competitiveness, through scientific and technological development and the sum of forces of these countries, prioritizing education as public good and preserving cultural diversity (FLAES, 2014).

In this context, the construction of the Latin American and Caribbean Area of Higher Education (ENLACES) is another space that deserves attention.

ENLACES should be understood as a regional platform for knowledge and information and integration in higher education for Latin America and the Caribbean. The platform includes actions for articulation, regulation, mobility and capacity building in institutions for the development and strengthening of HE systems with academic excellence and relevance that foster social inclusion (FLAES, 2014, p. 8).15

According to García-Guadilla (2013), whenever the quality of international exchanges is concerned, it is important to highlight : the Map of Higher Education for Latin America and the Caribbean [Mapa de Educación Superior para América Latina y el Caribe], which is a free access system, with statistical information about Latin American and Caribbean higher education institutions , and aims to allow for knowing about the behavior, characteristics, strengths and weaknesses of HE in the region; as well as the Comprehensive Information System on HEIs in Latin America, which aims to collaborate with the development of higher education institutions in the region and with academic cooperation among them, also serving as a support for the Common Area of Higher Education in synergy with the European Union. Some Latin countries have created programs to encourage the return of their researchers working abroad, such as: Red de Argentinos Investigadores y Científicos del Exterior, ChileGlobal, Red Caldas, Colombia nos Une, Circulación de Uruguayos Altamente Capacitados, Red de Talentos Mexicanos en el Exterior, Iniciativa Identificación de Talentos en el Exterior del Vice Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores para los Salvadoreños en el Extranjero (GARCÍA-GUADILLA, 2013).

Even so, the author states that only in Mexico the “brain drain” affects about 24% of the masters and 35% of the doctors, or about 20,000 researchers per year. A total exodus of 575,000 professionals is estimated at a cost to the country of over 100 billion pesos (GARCÍA-GUADILLA, 2013).

Another example, related to Brazil, was the creation of universities focused on issues of South-South cooperation, as a strategy of counter-hegemonic action to dominate the higher education market by the central countries. In 2009, the Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul [Federal University of Southern Frontier] (UFFS) was created, with a focus on addressing social issues and integrating regional development of Mercosur. In 2010 the Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana [Federal University of Latin American Integration] (UNILA) and the Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira [University of International Integration of Afro-Brazilian Lusophony] (UNILAB) were created. The first focused on integration, human resources education and the cultural, scientific and educational exchange of Latin America, especially Mercosur. The second, focused on the integration of Brazilian Higher Education with countries members of the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP), especially in Africa (MEC, 2014).

For Sousa Santos (2011), even with a somewhat lost hegemony, the 21st Century university will continue to connect the present and the future through the production and dissemination of knowledge. To do so, it must remain open to debate, discussion, as well to facing differences, changes, and knowledge. Restoring legitimacy to society will bring the strength needed to combat external and internal threats. To insert the university as a public good rooted into the idea of a nation, will strengthen not only the university itself, but also the country itself in the global context.

In this scenario, the university can not settle for a supporting role and passively watch the globalized commodification of Higher Education. It is up to it to find the means to emancipate itself, to legitimize itself and to become autonomous in relation to economic, mercantile, political or any other interests that intend to use it as a tool for social manipulation, positioning itself and fighting against such interests. Keeping up-to-date and adapting to the new technological realities without submitting to the interests that are in force today is needed, as well as improving quality without being subject to evaluative criteria that guide the world-class models that interest the market, institutions and central countries. Europe united their countries to preserve their own interests. It is up to Latin America to be able to unite its countries, not against, but in favor of the development of a Higher Education grounded in the concept of education as a public, equitable, democratic and solidary good.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The objective of this paper was related to critically approach the relationship center - periphery, bringing to the core of the debate the university, in general, and movements of Latin American universities, in particular.

The construction of contemporary scientific authority finds its bases grounded on the assumptions of modernity. Modern rationality divided, fragmented, and sought to exclude complexity from the process of making science. The construction and consolidation of science in this model, engendered in a dialectical movement within the model of capitalist production, became central to the social model that is now under way. The scientific field and scientific authority have become a field as social, privileging the maintenance of unequal relations of power and social dispute. Science depends on financial capital, consolidating the model of hegemonic disputes.

In the contemporary context, the university loses its hegemony as a center of knowledge, at the same time that the so-called crises settle in its bosom. The losses of identity, hegemony and legitimacy have been, in a dialectical movement, consolidated in movements of market disputes and hegemonic power. The rankings came to strengthen and consolidate this field of dispute, by resorting to methodologies that privilege the hegemonic centers. The so-called world-class universities now appear as models to be followed and gain yet another instrument for their legitimation. In addition, the limits established around such a model can not be denied, especially by the ideology of excellence that supports it, considering the following premises: the nation-state’s commitment to capital expansion, the economic potential promoted by internationalization, the centrality of research, the proletarianization of intellectual work, the reduction of academic training and the deepening of institutional differentiation (THIENGO, 2018).

In this model in dispute, the universities of Latin America are outside the hegemonic center, although it is possible to perceive numerical and scholarly growth. Thus they begin to appear in the rankings, however the gap between the so-called world-class universities and the Latin American universities is visible, as far as the current methodological criteria are used.

Hegemonic rationality in the university field, by privileging exclusion and inequality to the detriment of political and financial empowerment (re)produces the hegemonic forms of capital. The dyad self-feeds: scientific rationality and market ambition. In both, the hegemony of central countries and institutions, provided with physical, financial and political structure, is in place. In this scenario, they attract and retain the best minds in the world, giving back to the hegemonic centers and relegating to peripheral countries submission or scientific subordination. In an internationalized context of Higher Education, globalization imposes competitiveness. Rankings and other indicators not only confirm the centralized hegemony in some centers, but seem to have been created with the intention of maintaining this rationality.

However, if we assume that this rationality is one among other, it is possible to recognize the space of contradiction, of tension, of the multiple possibilities that human capacity for production is capable of. The “counter-hegemonic” actions undertaken by Latin America are still insufficient and timid. But it’s a start. Latin American countries, institutions and researchers need to follow up and expand these actions, seeking to strengthen forces in cooperation between them, with or without the participation of central countries, seeking insertion in a global way without subjecting their cultures, values and their characteristics to the risk of being erased from their history.

Far from attempting to completely exploring the topic, this article sought to contribute to the discussion, being aware that there is much to be discussed and innumerable research possibilities with conditions, not only to demonstrate the distance between the peripheral and central realities in the academic world, but in the sense of fostering counter-hegemonic actions that aim to contribute more to an equitable and egalitarian insertion in the global reality than to create other forms of division. In this sense, it is necessary to question whether the institutions of higher education that are in the periphery can be inserted globally tensioning hegemonic models? What actions and strategies of internationalization at home are being implemented in Latin American universities bearing in mind the perspective of underscoring hegemonic models? Such questions are complex, albeit necessary, so as to broaden the debate of the center-periphery relationship in the context of Latin American universities.

REFERENCES

BOURDIEU, P. O Campo Científico. In: ORTIZ, R.; FERNANDES, F. Pierre Bourdieu: Sociologia. São Paulo: Ática, 1983. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. Homo Academicus. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Siglo XXI, 2008. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. Os usos sociais da ciência: por uma sociologia clínica do campo científico. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2003. [ Links ]

CENTRO DE UNIVERSIDADES DE CLASSE MUNDIAL - CWCU, Academic Ranking of World Universities - ARWU. 2015Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.shanghairanking.com/pt/ >. Acesso em: 01 ago. 2016. [ Links ]

CRES. Declaração da Conferência Regional de Educação Superior da América Latina e do Caribe. Cartagenas de Índias, 2008. Avaliação (Campinas), Sorocaba , v. 14, n. 1, p. 235-246, Mar. 2009. [ Links ]

FÓRUM LATINO-AMERICANO DE EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR - FLAES Pertinência E Equidade Na Educação Superior Na América Latina E Caribe. Declaração De Foz Do Iguaçu, 2014. Disponível em:< Disponível em:https://unila.edu.br/sites/default/files/files/FLAES%20final%2018_11%20-%20tarde-Formatado.pdf >. Acesso em: 05 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

GARCÍA-GUADILLA, Ca. (2013), “Universidad, desarrollo y cooperación en la perspectiva de América Latina”, en Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior (ries), México, unam-iisue/Universia, vol. IV, núm. 9, pp. 21-33, < 21-33, https://ries.universia.net/article/view/98/universidad-desarrollo-cooperacion-perspectiva-america-latina >. Acesso em: 15 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

KEELEY, B. Migración Internacional - El lado humano de la globalización. Esenciales OCDE, OECD Publishing-Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas, UNAM. 2012. Disponível em: : <Disponível em: : http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/0109114e.pdf?expires=1469650313&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=5D57DBD0DDC7C215DA5CD157BE8DDC98 >. Acesso em: 25 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

KREIMER, P. Cap 5 - Ciencia y periferia. In: El científico es también un ser humano. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI. 2009. [ Links ]

KREIMER, P. Internacionalização e tensões da ciência latino-americana. Cienc. Cult. 2011, vol.63, n.2, pp. 56-59. ISSN 0009-6725. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://cienciaecultura.bvs.br/scielo.php?pid=S0009-67252011000200018&script=sci_arttext >.Acesso em: 20 out. 2016. [ Links ]

LEITE, D. e GENRO, M. E. H. Quo Vadis? Avaliação E Internacionalização Da Educação Superior Na América Latina. In: LEITE, D . et.al. Políticas de evaluación universitaria en América Latina : perspectivas críticas. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: CLACSO; Instituto de investigaciones Gino Germani, 2012. [ Links ]

Nature Index. 2016 tables: Countries. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.natureindex.com/annual-tables/2016/country/all >. Acesso em 25 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

OCDE - Panorama de la educación 2015: Indicadores de la OCDE. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/panorama-de-la-educacion_20795793 >. Acessado em: 25 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

ORTEGA Y GASSET, J. Missão da Universidade. Rio de Janeiro: EdUERJ, 1999. [ Links ]

RODRIGUEZ, M. V. e MARTINS; L. G. de A. Ensino Superior na América Latina e a Globalização da Racionalidade Capitalista. In: ALMEIDA, Maria. de L.P. de e PEREIRA, Elisabete M. de A.(org.) Políticas Educacionais de Ensino Superior no Século XXI. Um olhar transnacional. Campinas, SP: Mercado das Letras, 2011. [ Links ]

SILVAJUNIOR, J. dos R. The new brazilian university: a busca por resultados comercilializáveis: para quem? Bauru: Canal 6 2017. [ Links ]

SOUSA SANTOS, B. de. Da Ideia de Universidade a Universidade de Ideias. In: SOUSA SANTOS, B. de. Pela Mão de Alice: o social e o político na pós-modernidade. 4ª ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 1997. [ Links ]

SOUSA SANTOS, B. de. A ecologia de saberes. In: SOUSA SANTOS, B. de. A Gramática do Tempo: para uma nova cultura política. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006. (Coleção para um novo senso comum; v. 4). [ Links ]

SOUSA SANTOS, B. de. A universidade do Século XXI: para uma reforma democrática e emancipatória da Universidade. 3ª ed. São Paulo: Cortez , 2011. [ Links ]

TIMES - World University Rankings 2016-2017 - THE. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2017/world-ranking#!/page/0/length/25/locations/AR+BR+CL+CO+CR+MX+VE/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats >. Acesso em: 15 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

THIENGO, L. C. Universidades de classe mundial e o consenso pela excelência: : tendências globais e locais. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Ciências da Educação, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Florianópolis, 2018. [ Links ]

4In the original in Portuguese “ciência é um campo social como outro qualquer, com suas relações de força e monopólios, suas lutas e estratégias, seus interesses e lucros”. Translated by the the authors.

5In the original “Os dominantes são aqueles que conseguem impor uma definição da ciência segundo a qual a realização mais perfeita consiste em ter, ser e fazer aquilo que eles têm, são e fazem”. Translated by the authors.

6The term South (Sul) is employed in the perspective of Sousa Santos (2006), when the author uses the concept of epistemologies of the South.

7In the original “Si supusiéramos que la ciencia es algo universal a secas, y que es indiferente a los espacios sociales donde se genera, no tendría ningún sentido pensar que en cada país, en cada contexto, la ciencia es distinta”. Translated by the authors.

8In the original “Ao contrário do universalismo, a globalização é a expressão de uma hierarquia entre o centro e a periferia do sistema mundial num contexto em que a invisibilidade das colônias entregues “à guarda” do centro deu lugar à proliferação de actores estatais e não-estatais, constituídos no âmbito das relações desiguais entre o centro e a periferia, entre o Norte global e o Sul global, entre incluídos e excluídos”. Translated by the authors.

9In the original “Poderíamos observar ali um paradoxo: os pesquisadores de elite dos países “não hegemônicos” são crescentemente convidados a participar de consórcios internacionais, mas suas condições de acesso são cada vez mais restritas e as margens de negociação tendem a ser mínimas”. Translated by the authors.

10In the original “A minha análise centrava-se nas universidades públicas. Mostrava que a universidade, longe de poder resolver as suas crises, tinha vindo a geri-las de molde a evitar que elas se aprofundassem descontroladamente [...] Tratava-se de uma actuação ao sabor das pressões (reactiva), com incorporação acrítica de lógicas sociais e institucionais exteriores (dependente) e sem perspectivas de médio ou longo prazo (imediatista)”. Translated by the authors.

11In the original “Na Europa onde o sistema universitário é quase totalmente público, a universidade pública tem tido, em geral, poder para reduzir o âmbito da descapitalização ao mesmo tempo que tem desenvolvido a capacidade para gerar receitas próprias através do mercado. O êxito desta estratégia depende em boa medida do poder da universidade pública e seus aliados políticos para impedir a emergência significativa do mercado das universidades privadas. [...] Nos EUA, onde as universidades privadas ocupam o topo da hierarquia, as universidades públicas foram induzidas a buscar fontes alternativas de financiamento junto de fundações, no mercado e através do aumento dos preços das matrículas”. Translated by the authors.

12In the original “A universidade não sairá do túnel entre o passado e o futuro em que se encontra enquanto não for reconstruído o projecto de país. Aliás, é isso precisamente o que está acontecer nos países centrais. As universidades globais dos EUA, da Austrália e da Nova Zelândia actuam no quadro de projectos nacionais que têm o mundo como espaço de acção.”. Translated by the author.

13In the original “As publicações se tornaram mercadorias produzidas por uma indústria editorial que se configura como monopólio da venda dos direitos autorais. Mundo afora, muitas universidades vendem as produções de seus professores nesse mercado. As universidades vendem os direitos autorais de produções de seus pesquisadores profissionais. Os pesquisadores recebem adicionais em seus salários ao venderem seus direitos autorais por quantias razoável para as universidades em que trabalham. Por outro lado, as publicações correm , em muita áreas do conhecimento, como a farmacêutica, as áreas tecnológicas e a matemática, somente depois que se tornaram patentes ou depois que uma equação matemática tornou-se um produto financeiro em Wall Street.”. Translated by the authors.

14In the original “a qualidade da educação superior associada à pertinência, à equidade e à universalidade; a educação superior como bem público social; a indissociabilidade entre aquisição, construção e aplicação de conhecimento e a construção de valores éticos; a autonomia e a inclusão nas instituições de educação superior; e a integração institucional e social nos contextos nacionais, regionais e internacionais”. Translation by the authors.

15In the original “O ENLACES deve ser entendido como uma plataforma regional do conhecimento e informação e da integração em educação superior para a América Latina e Caribe. A plataforma contempla ações de articulação, regulação, mobilidade e construção de capacidades nas instituições para o desenvolvimento e fortalecimento dos sistemas de ES com excelência acadêmica e pertinência que fomentem a inclusão social”. Translation by the authors.

Received: March 26, 2018; Accepted: March 14, 2019

texto em

texto em