Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.35 Belo Horizonte jan./dez 2019 Epub 21-Ago-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698219650

DOSSIER EDUCATION, HEALTH AND RECREATION

ARTICLE - OPEN-AIR SCHOOL OF SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE APLICAÇÃO AO AR LIVRE DE SÃO PAULO

IUniversity of São Paulo, Campus Baixada Santista, SP, Brasil

The paper discusses the history of the Open-Air School of São Paulo, a preschool institution created in 1939 inside the Água Branca Park in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Its classes were carried out with portables blackboards and school desks. International, national and local knowledge about open-air institutions that were in circulation in São Paulo in previous years was appropriated for its creation. The school was promoted as a model institution, being used as field of application and internships for students from the Higher School of Physical Education and the Normal School Caetano de Campos. In 1952 the school was transferred to a special building, which ensured the realization of open-air classes. The sources used in this research are newspaper articles from São Paulo’s press, decrees, laws, draft legislation, official reports, books, monographs and journals of education and physical education.

Keywords: Open-air schools; Outdoor education; Experimental teaching.Body education

O artigo aborda a história da Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre de São Paulo, instituição de ensino infantil instalada no interior do Parque da Água Branca em 1939. As suas aulas eram realizadas com emprego de lousas e carteiras portáteis. Conhecimentos internacionais, nacionais e locais sobre as instituições médico-educativas ao ar livre, que se encontravam em circulação em São Paulo nos anos anteriores, foram apropriados para a sua criação. A escola foi divulgada como uma instituição modelo de ensino, sendo empregada como campo de aplicação e estágios da Escola Superior de Educação Física e da Escola Normal Caetano de Campos. Em 1952 foi transferida para edifício especialmente construído para abrigá-la, o qual assegurava a realização de aulas ao ar livre. As fontes da pesquisa se constituem em matérias de jornais paulistas, decretos, leis, projetos de leis, relatórios oficiais, livros, monografias e periódicos de educação e de educação física.

Palavras-chave: Escolas ao ar livre; Educação ao ar livre; Ensino experimental; Educação do corpo.

INTRODUCTION

The object of analysis of this research is Open-Air Application School of São Paulo (OAAS), an educational institution established inside Água Branca Park, in the city of São Paulo, Brazil, in 1939. The school began its activities with two classes, one of pre-school and other of elementary school for children of both sexes. One of its main differentials was that it used lightweight transportable desks and blackboards, which allowed its classes to be held totally outdoors, in different places of the park. In 1952, the school was moved to a building specially designed to house it in the vicinity of the park. Nowadays it is denominated as Escola Estadual Dr. Edmundo de Carvalho. In recent years it has attracted the attention of some History researchers because it had been an experimental teaching institution that brought innovative pedagogical proposals.

According to Dalben (2009, 2014), OAAS was inaugurated by the Department of Physical Education (DPA), a division of the Secretariat of Education and Public Health of the State of São Paulo, and was under the jurisdiction of the Pedagogy and Methodology Section of the Superior School of Physical Education (ESEF) until 1955. It was established as a school of pedagogical applications and as a field of observations and internships for students of ESEF and the Normal School Caetano de Campos. It was regarded as a model school, with space, pedagogical proposals and school materials quite different from other São Paulo elementary schools of that time (DALBEN, 2015b). According to Bermond (2007), considering the peculiarities of OAAS which placed children in constant contact with nature in the Água Branca Park during their outdoor classes, it would be possible to approximate its pedagogical experiences to the old educational conceptions formulated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century. However, its most recent references were open-air schools designed by professionals from many countries since the early 20th century. In Brazil, open-air schools were the subject of several articles published in medical and education journals, congress communications, and books and monographs written by doctors and educators (DALBEN, 2014).

The construction of the building that housed OAAS from 1952 on was due to an agreement established between the São Paulo City Hall and the State Government for the construction of new school units, known as School Agreement (CALDEIRA, 2005; ABREU, 2007). Three years after the transfer to the new building, OAAS was dissociated from ESEF and DPA, but continued to follow its experimental teaching vocation (SÃO PAULO, 1955a, 1955b). The research conducted by Passos, Ferreira and Matte (2013) studied the history of the experimental schools curricula in São Paulo from the 1950s onwards and found in OAAS its main object of analysis. The authors narrated the series of legal restructuring undergone by the school throughout its history and sketched analyzes about the limitations of the role played by its pedagogical experiences in the renewal of the teaching of São Paulo. Bizzocchi (2016) showed that although the school followed the main educational movements of the 1960s and 1970s, it was able to establish its own innovative pedagogical identity. These two investigations concentrated in the period after its transfer to its new building and the interest in studying it stemmed from the singular experiences that the school undergone throughout its history.

The number of national researches focusing on open-air schools is still very small, while in other countries several studies have been conducted. For example, in 2003 the book L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et l’archécturale dans l’Europe du XXe siècle (CHATÊLET, LERCH, LUC, 2003) was published, gathering research on the history of open-air schools created in Germany, Belgium, Spain, France, Holland, England, Italy, Sweden and Switzerland. The investigations carried out by researchers were related to History, History of Education, History of Physical Education, History of Architecture and History of Medicine and Hygiene. In 2011, Chatélet published the work Le souffle du plein air. Histoire d’un projet pédagogique et architectural novateur (1904-1952) presenting a comparative study between open-air schools created in different European countries. It is also worth noting the research carried out on open-air schools created in Argentina (DI LISCIA, 2005, ARMUS, 2007, 2014, LIONETTI, 2014) in Uruguay (DALBEN, 2019) and the United States (GUTMAN, CONINCK- 2008; GREENE, 2011).

The research presented here has as justification to contribute both to the search of sources related to the memory of the OAAS of São Paulo and to encourage new approaches and investigations on the history of outdoor body education, conceived, in this specific case, from its more refined school form, the open-air school. It takes part in a set of researches carried out in recent years that analyze ideas responsible for conceiving nature as a space of healing, prevention, education and amusement, as well as inquiring about the importance of outdoor life in the configuration of educative processes of the body (SIROST, 2009; SOARES, 2015). And last but not least, the central ideas put into question by the open-air schools - of an education accomplished through concrete observation of nature, of an outdoor life in line with corporal practices performed in the shade of trees in forests and urban parks, as well of criticism of traditional teaching methods and school configurations - constitute a significant set of ideas for the field of education and touch subtly touch sensitivities of the present time.

In the impossibility of narrating a history that addresses all aspects of an object of study, it becomes necessary to select, organize and simplify, in order to adopt epistemological cuts that confer intelligibility to the research. Regarding the temporal cut, the period in which the school operated inside the Água Branca Park, from 1939 to 1952 was initially adopted, since its main objective was to analyze its functioning in that space. During the research, however, this period was gradually extended, going back in time, in order to get a better understanding of how the knowledge that allowed the creation of OAAS has circulated. It is important to highlight that its main idealizer was doctor Edmundo de Carvalho, who was responsible for the appropriation of the knowledge on the medical-educational open-air institutions that was in circulation in that period. Thus, the objective of the research was extended to analyze the actions performed by Carvalho, within the network of sociability that he built throughout his career for the creation of the OAAS and the process of planning, construction and transfer of the school to the building erected by the School Agreement of 1952. The data collection was carried out in sources such as the Digital Library of the National Library (Brazil); the website of the Legislative Assembly of the State of São Paulo; the library of the Rotary Club of São Paulo; the library of the Faculty of Physical Education of the University of Campinas; and the Memory of Education website of the Public Archive of the State of São Paulo. These sources are made up of articles from São Paulo newspapers of great circulation, decrees, laws, bills, official reports, books, monographs and journals of education and physical education journals.

THE CIRCULATION OF KNOWLEDGE ON OPEN-AIR SCHOOLS

According to Chatelet (2003), the first open-air schools were born in Germany and Belgium simultaneously in 1904, and Luc (2003) states that open-air schools arose from the idea of associating education with public health. As medical institution, open-air schools were part of policies to prevent tuberculosis, a disease that spread through many countries in the early 20th century. It is important to note that B.C.G. was developed in the 1920s, but its large-scale usage began only from the 1950s. Prior to 1950, tuberculosis control and prevention was undertaken by medical prescriptions that included natural therapies offered in sanatoria and other medical institutions that combined physical exercise in the open air with the systematic exposure of the body to sunlight and fresh air (BERTOLLI FILHO, 2001; ARMUS, 2007).

In general, open-air schools, sanatoria, and holiday colonies were institutions that shared the same medical idea, prioritizing nature and its elements for healing and disease prevention. The theoretical foundations for fighting tuberculosis stem mainly from the therapies formulated by natural medicine. Treatments developed by this medical branch, known as hydrotherapy, heliotherapy, climatotherapy, among others, began to be used in the late 19th century in healing establishments such as children’s sanatoria and children’s holiday colonies (BAUBÉROT, 2004, VILLARET, 2005, VILLARET & SAINTMARTIN, 2004, ARMUS, 2007, DALBEN, 2014, 2015a).

According to Ludwig (2003), at the end of the 19th century, German professionals began to question the effectiveness of sanatoria and children’s holiday colonies in controlling tuberculosis. The questioning referred mainly to the period in which children would remain in these institutions, which were considered insufficient to restore their state of health in a lasting way. In addition, if there was an extension in such period, children would have to stop attending school, which caused them to fall behind at school when they returned home. Conversely, open-air schools could allow the children under treatment to undergo natural therapies for months without interrupting or compromising the schooling process. As noted by Depaepe and Simon (2003), in the beginning, open-air schools were confused with permanent vacation colonies, school preventoria, among many other common denominations of that time. According to Thyssen (2018), open-air schools have long been interconnected and have even been indistinguishable from other projects in the fields of preventive health and school hygiene.

For Châtelet (2003), the first experiences of outdoor institutions put into practice in different countries in the early 20th century began to gain international recognition through tuberculosis and school hygiene congresses held in Europe. The circulation of knowledge promoted by these congresses made it possible, in 1922, to organize the 1st international congress of open-air schools in Paris. According to Jablonka (2003) and Villaret (2005), the objective of the event was to establish a theoretical consensus in order to differentiate open-air schools from other institutions that shared the same matrix of thought, conceiving nature as an ideal agent both for both education and prevention and cure of diseases. At the end of the congress, the open-air school was defined as a medical-pedagogical institution for school-age children who should reconcile their fragile organic needs with the need for instruction, adopting a categorization in four terms: outdoor classes, open-air boarding schools, open-air day schools and preventoria.

Emerging from the areas of medicine and education, open-air schools have in many cases sought to present pedagogical and hygienic alternatives to more traditional school models. By 1920 open-air schools gained support from the New School movements and were adopted in several countries as an innovation that could replace the existing traditional school models. The 1st international congress of open-air schools took place precisely at the time of the rise of New School movement, and among its participants were several social actors linked to it. They proposed that open-air schools should not be restricted to educational alternatives, remaining limited to the objective of strengthening physically weak children, thus being an exception in public primary education systems, but to serve as a model institution to be emulated by all elementary schooling. The originality of open-air schools was evident in their educational programs, characterized by the need to keep students mostly outdoors and the portable furniture used. Many open-air schools have turned into true fields of pedagogical experiences. In general, physical exercises, heliotherapy sessions, lectures on hygiene, and meals took up much of school time, reducing the duration of classes while favoring pedagogical exploration of the environment, multidisciplinary approaches, active teaching methods, autonomy learning and approximation between teachers and students (MARTINEZ, 2000, JABLONKA, 2003, RUCHAT, 2003, SAVOYE, 2003).

Jablonka (2003) stated that the 1st international congress of open-air schools represented a step forward in the establishment of guidelines for unifying a polysemous international movement that was already in full expansion. The organization of an international movement, however, should not be considered as a uniform effort, free from rivalry and ambiguities. According to Depaepe and Simon (2003), the four categories established at the end of the event (outdoor classes, open-air boarding schools, open-air day schools and preventoria) were conceptual schemes aimed at organizing an international movement. However, the interest in defining what professionals and institutions were (or not) part of this international movement did not fail to appear. Thyssen (2018) discusses the very establishment of a steady international movement for open-air schools, criticizing the diffusionist conception that based on early examples other open-air schools would have their models simply transferred to and disseminated in new territories. According to Jablonka (2003), the diversity of actors and knowledge at stake when thinking about the history of open-air schools imposes plural historical readings and analyzes. The creation of these institutions in different countries obliges us to consider the networks of organized sociability, the appropriations and singularities at national and local levels, as well as analyzing the limits of the encounters in each experience put in practice by different social actors.

These reflections bring to light the different characteristics that open-air schools have assumed and require analyzes of the historical particularities of each initiative put into practice around the world. In the Brazilian case, the pan American child congresses were an important way for circulating knowledge about open-air schools and natural medicine therapies. In the first edition of the congress, held in Buenos Aires in 1916, a Brazilian commission of doctors, presided over by pediatrician Carlos Arthur Moncorvo Filho, reported some heliotherapy trials conducted in Brazil a few years earlier. In São Paulo, tuberculosis doctor and president of the Paulista League Against Tuberculosis Clemente Ferreira had studied and applied sunbathing to fight tuberculosis since 1914 (MONCORVO FILHO, 1917). In addition to the congresses, the circulation of knowledge about heliotherapy in Brazil was also recorded in theses written by medical students and several articles in medical journals. In conjunction with heliotherapy, these works also disseminated in Brazil a series of medical-educational institutions specially focused on children’s care which commonly applied the precepts of natural medicine, such as preventoria, children’s vacation colonies and open-air schools. The reception and circulation of knowledge on natural therapies in Brazil during the first decades of the 20th century accompanied the increasing interest of the Brazilian medical class in open-air medical educational institutions.

In São Paulo, during the first decades of the 20th century the dissemination of knowledge about open-air schools was also present, Clemente Ferreira (a frequent participant of the international congresses of tuberculosis in Europe) being one of the main disseminators of these institutions (ROSENBERG, 2008; FERREIRA, 1906, 1913, 1929). The reform of the Sanitary Service of 1917 already foresaw that “Open-air schools, aimed mainly at children of weak constitution, will be installed according to modern precepts of pedagogical hygiene” (SÃO PAULO, 1917). In some interpretations, open-air schools went beyond the simple prevention of tuberculosis being also designed as normalization guidelines. This was the conception adopted by the physician Balthazar Vieira de Mello, head of the School Medical Inspection of São Paulo in his work entitled ‘Escolas ao ar livre e colônias de férias para débeis. Escolas especiais para tardos’ (Open-air schools and holiday colonies for the weak. Special schools for the abnormals), published in 1917. In this case, it is possible to verify a rather close approximation of his thought to the eugenic movement of São Paulo. Vieira de Mello recommended the creation of open-air schools in São Paulo especially designed to attend children classified as abnormal, either by their physical constitution or psychic aspects. The anthropometric and psychic evaluation sheets created by the physician were based on the polarization between children’s bodies considered as normal and pathological (ROCHA, 2015; ALMEIDA, 2015).

In 1932, Brazilian doctor João Ferraz do Amaral presented his monograph entitled “Open-air schools: contribution to the study of the problem of school hygiene in São Paulo” at the Faculty of Medicine of São Paulo, supervised by physician Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza. He affirmed that “As precursors, in S. Paulo we may perhaps present the extinct 7th of September Schools, which for some months, around 1920, took their children to the city parks where school the work was developed” (AMARAL, 1932, p. 20). The author also referred to the School of Health created by the local Sanitary Service at Jardim da Luz as well as to the playground inaugurated in 1930 in the Parque Dom Pedro II. These initiatives can be understood as a first movement to incorporate the precepts of open-air education in the state of São Paulo, these precepts assuming a more solid and consistent conformation, especially with the inauguration of the first school to adopt the term “open-air” in its names. Amaral’s work shows that, under the concept of “open-air”, the author grouped a great diversity of initiatives, including lessons realized outside the classrooms, schools for the mentally disabled, medical-preventive institutions and playgrounds.1 This plural mode of conceiving open-air schools meant that the concept of “open-air” was so dynamic that it was almost dispersed, so these schools could have several different formats, provided they used the general principle of “educating children with a view to their physical strengthening in contact with natural resources”(Amaral, 1932, p.24).

Amaral’s monograph compiled a large part of the Brazilian authors who were dedicated to the subject, as well as texts published by foreign authors from France, Argentina, Uruguay and USA. The references used demonstrate the great plurality of views about open-air schools circulating at that time in São Paulo. That dissemination of knowledge can also be traced back by texts published in medical and educational journals. In 1937, for example, the Revista de Educação published a note on the 3rd international congress of open-air schools, held in Bielefeld, Germany, July 1936. The note reveals that the issues debated in Europe reached Brazil, being announced in the official magazine of the Secretariat of Education and Public Health of the State of São Paulo, and provided the reader with the conclusions established at the closing event (3º CONGRESSO, 1937). This set of knowledge in circulation was certainly of great value to the idealization and creation of OAAS. However, it is difficult to establish direct links between the different conceptions of open-air schools available in São Paulo and the project for the creation of OAAS, because its idealizer left few written texts.

MEDICAL AND EDUCATIONAL OPEN AIR INSTITUTIONS IN SÃO PAULO

The OAAS was conceived and founded by Edmundo de Carvalho, a doctor who, despite having published few texts, played a significant role in the fields of education, physical education and child care, as can be seen from records left in São Paulo newspapers. He was born into an elite family in São Paulo, graduated from the Faculty of Medicine of Bahia in 1906 and defended a monograph in ophthalmology. In the following year started working at the Anti-Trachomatous Post in Rio Claro, but shortly after he resigned due to a government funding that enabled him to undertake a study trip in Europe (AVULSOS, 1907, HOSPEDES, 1908). He stayed for a year in the cities of Vienna and Rome, and when he returned to Brazil he started his own ophthalmological practice in São Paulo (OCULISTAS, 1909). In the early 1910s, he assumed the position of optician at the Health Corps of the Public Force of the State of São Paulo, where he worked until 1925 (FORÇA, 1914, O ENSINO, 1922; FOI EXONERADO, 1925).

His work in the field of child care began in 1922, when he started to raise funds for the foundation of an institution called Instituto de Cultura Physica da Infância (BAILE, 1922). It was a philanthropic institution aimed at offering natural medicine treatments and outdoor physical exercises for children of the orphanages of São Paulo city. The space for the installation of the institution was granted by the São Paulo City Hall on a land near the Água Branca Park (SÃO PAULO, 1922). He intended to construct three pavilions, a swimming pool, playgrounds and an athletics track, mechanotherapy and outdoor bodywork, all set in gardens and a leafy wood (INSTITUTO, 1923). Edmundo de Carvalho’s attempts to raise funds for these facilities lasted for at least two years, but despite having been able to obtain the land and assemble a group of professionals to manage it, the institute ended up not being constructed (INSTITUTO, 1924, PELA SAÚDE, 1924). Nevertheless, it is interesting to highlight that the concept that Edmundo de Carvalho intended to develop was based on the precepts of natural medicine, such as the contact with nature and its elements for the strengthening of the infant body.

Between 1928 and 1929, Edmundo de Carvalho took over the presidency of the Rotary Club of São Paulo, an organization that enabled him to extend his actions to the fields of physical education and childcare. One of the projects presented during his management time, in a meeting held in January 1929, was to use vacant lots in the city for the practice of physical education. The project resulted from a partnership involving individual citizens, the City Hall and State Government. The City Hall would exempt land owners from taxes to be paid, the State Government would be responsible for installation of water and electricity, and the Rotary Club would administer the site in partnership with the State Sanitary Service (UHLE, 1991; SALES, 1994).

For the proposal to be successful, new directions would have to be taken by the network of sociability articulated by Carvalho. Months after the presentation of the project, Mayor João Pires do Rio granted part of Dom Pedro II Park for the construction of a playground and engineer Luiz Ignácio de Anhaia Mello was invited to lecture at the Rotary Club about “active recreation in modern societies”2 (MOREIRA, 1955). At the meeting, the mayor revealed that it was a large project and stated that he was already taking care to “transform places like the Jardim da Luz, the Ipiranga river sources, the Ibiraquéra site and the Tamanduateí margins into playgrounds” (ROTARY, 1929, p. 5). Two months later, the municipality transferred public resources to the Instituto de Cultura Physica de Infância, so that it could begin the construction of the playgroud facilities in Parque Dom Pedro II (SÃO PAULO, 1929). Inaugurated in December 1930, its administration was transfered to the Pro-Childhood Crusade in March 1931, by the Mayor Anhaia Mello (INAUGURA-SE, 1930, MELHOR, 1931). Years later, the playground project would be restructured and would give rise to the playgrounds of São Paulo administered by Mário de Andrade (DALBEN, 2016, KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, 2017).

At the same time as Edmundo de Carvalho articulated the creation of the city’s first playground, he also tried to implement other open-air institutions in São Paulo. According to the talk given to Educadora Paulista radio by Amadeu Mendes, General Director of Public Instruction of the State of São Paulo in June 1929, the Rotary Club was dedicated at that time to creating playgrounds such as holiday colonies and open-air schools (MENDES, 1929). Shortly after the lecture, the inauguration of the School for the Weak in the playground of Elementary School Prudente de Moraes was announced as a joint initiative of Edmundo de Carvalho and the Board of Public Instruction (NOS DOMÍNIOS, 1929). The school attended 50 children from 9 to 12 years old, selected at the Elementary School Prudente de Moraes. The schoolyard and its location, in front of the Jardim da Luz, allowed all classes to be held outdoors (EM PROL, 1930). The School for the Weak, however, encountered a series of administrative obstacles and closed its activities a few months after its inauguration. Nevertheless we highlight that the outdoor environment had centrality in the institution, so that gym classes and heliotherapy sessions have been held at Jardim da Luz.

While serving as president of the Rotary Club, Edmundo de Carvalho sought to articulate a network of sociability with professionals related to physical education and sports in São Paulo. In the event of the local Young Men›s Christian Association, he spoke on “The value of practical education” and, together with the Tietê Regatta Club, organized a series of lectures on sports medicine, given by various experts (Na Ass., 1929, Conferencias, 1929). In April of 1929, he was invited by the General Direction of the Sanitary Service to compose the organizing committee of the Week of Demonstration of Physical Culture, a state sport tournament (A REALIZAÇÃO, 1929). His relationship with physical education would consolidate in 1935, when he was elected president of the Paulista Association of Physical Education3 (ASSOCIAÇÃO, 1935).

Throughout the 1930s, Edmundo de Carvalho sought to expand his netwotk of sociability in the field of philanthropy and continued to work for the creation of outdoor medical-educational institutions. At that time, he approached the League of Catholic Ladies, a charitable organization of assistance dedicated to abandoned minors, and the Paulista Flag of Literacy, responsible for the creation of the School of Life in 1935 (A QUESTÃO, 1933; A INAUGURAÇÃO, 1935). This educational institution operated at the headquarters of Cruz Azul, near Jardim da Luz. The pedagogical part was conducted by Sebastiana Teixeira de Carvalho, responsible for educational games, singing and drawing activities, while the medical part was in charge of Edmundo Carvalho, who was responsible for orienting the heliotherapy sessions (ESCOLA, 1935; PARA O SORRISO, 1935). For the realization of the sessions, the proposal was that part of the material previously used in the School for the Weak, such as sunbeds and covers for the sun, was transferred to the School of Life (PARA O SORRISO, 1935). The educational institution had served children aged 5 to 7 years that lived in poor sanitary conditions, or coming from poor families or with physical disabilities (BANDEIRA, 1935). The prioritized teaching method was that of the center of interests, and children participated in infant parties, such as those held in the Parque Dom Pedro II, and in agricultural fairs, such as those held at Água Branca Park (PARA FELICIDADE, 1935; UMA ENCANTADORA, 1935; FAZENDO, 1936). Great part of the resources for its operation used to come from donations from companies, philanthropic entities and individuals. In 1936 the institution was enrolled in the Department of Social Assistance under the name of Educational Assistance to the Poor Child and moved its headquarters to another building located in the vicinity of Jardim da Luz, which allowed the gym classes to continue to be performed outdoors.

Throughout his career, Dr. Edmundo de Carvalho has built a network of sociability linked to the fields of education, physical education and child care in São Paulo. As discussed earlier, his philanthropic activities became more significant when he assumed the presidency of the Rotary Club, and from that moment on, he divulged and fulfilled some of his intentions to create medical-educational institutions in the open air for needy children in São Paulo. The relations established between Carvalho and personalities linked to philanthropy and education accentuated in 1937, when he joined the Cooperating Council of the National Crusade of Education (A POSSE, 1937). On the other hand, his relationships with physical education professionals were further accentuated in 1938, when he was invited by the secretary of education, Álvaro Figueiredo Guião, who was also a physician, to direct the Department of Physical Education of the State of São Paulo (TOMOU, 1932).

Since the establishment of the political regime called Estado Novo, the Secretariat of Education and Public Health has undergone a series of restructuring led by Álvaro Guião and special attention was given to the DPA. The intention was to put into practice a new physical education project for the State of São Paulo, with Edmundo de Carvalho as its director. The restructurings carried out promoted changes in the legal attributions of DPA. Until then responsible mainly for the administration of sports, the division began to promote “physical education, as well as moral and civic education for all children and adolescents of the State of São Paulo” (SÃO PAULO, 1939a, p. .1). The invitation made to Carvalho to assume the direction of the DPA was accompanied by an expressive increase in the number of employees and in the budget of this public office, a situation that would finally allow him to put into action his plans to create an open-air school in the city of São Paulo (ACTOS, 1937, SAO PAULO, 1939b). It is interesting to note that the invitation was made by Álvaro Guião, a physician trained at the University of Geneva, Switzerland, where natural medicine and open-air medical and educational institutions have achieved great notoriety (HELLER, 2003).

THE OPEN-AIR APPLICATION SCHOOL OF SÃO PAULO

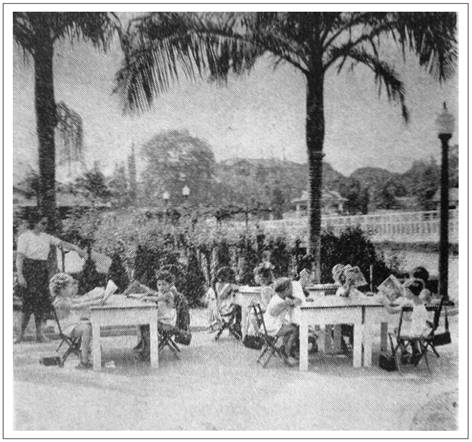

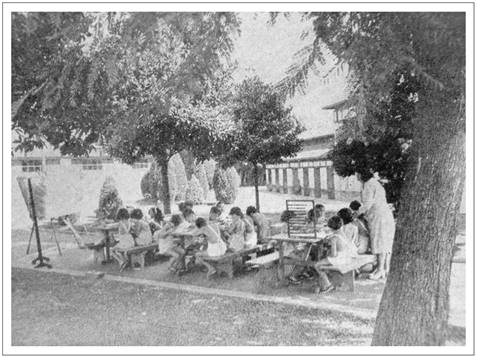

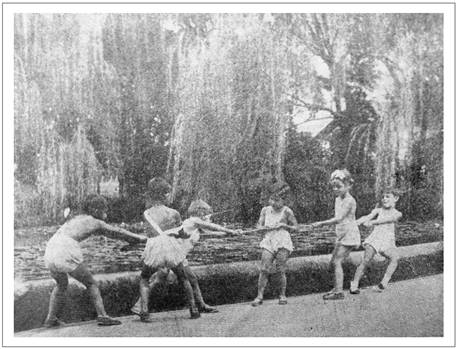

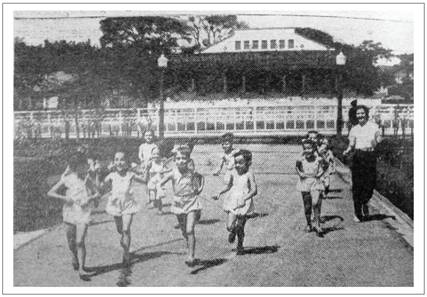

On June 13, 1939, the OAAS creation decree was published, justifying the need in São Paulo for a model child education center and an application school for the students of ESEF and the normal schools (SÃO PAULO, 1939b). The classes were taught by the normal teachers Jenny P. Lanzoni and Julieta Gallo (FORAM, 1942). Annex to the decree there were the guidelines for its organization, program and schedule. We assumed that this text was written by Edmundo de Carvalho. It contained the main medical and pedagogical foundations that used to be claimed in defense of open-air schools: staying outdoors, in contact with nature, with sunlight and fresh air, instead of in enclosed and unhygienic places existing in urban centers. “Under pure air and sunlight blood circulation are activated, assimilation and motility are stimulated and, as a result, the appetite redoubles, the vivacity and the energy of movement appear, accompanied by the sensation of well-being and joy” (SÃO. PAULO, 1939b, p.2). Physical education would gain prominence, being the basis of an integral education project, still composed of educational activities based on the interests of the children. The idea was that the school would be of great interest of the students. According to these words, open-air schools could be a solution to early childhood education, since “they give greater opportunities for physical development and favor the environment, free from traditional frameworks, highly educational activities” (SÃO PAULO, 1939b, p. 2).

The proposal was to provide an innovative educational environment, with many precepts coming from the New School movement. The pre-school teacher would have the role of guiding and stimulating children to obtain knowledge from observation, experience and projects developed according to their own interests. An art gallery was foreseen to expose the works developed by the children, besides the space for the cultivation of a vegetable garden. The stories told by the teachers could serve as a motive for dramatizations. In elementary school, the idea was that, because it is an open-air school, the intimate contact with the park’s structures could favor, from observation, the acquisition of scientific knowledge about nature, history and geography. The teaching of arithmetic and language would be interspersed with works of expression: drawing, painting, modeling, carpentry and embroidery. “In elementary school, what matters is the method, so that the subject becomes interesting and the children learns without realizing it, by playing without being attached to a routine that is against their nature” (SÃO PAULO, 1939b, p. 3). In both classes it would be the mixed teaching prioritized “Teaching girls and boys to collaborate together, without distinction of sexes, is to raise them up to the path that leads to the ideal of life” (SÃO PAULO, 1939b, p. 2).

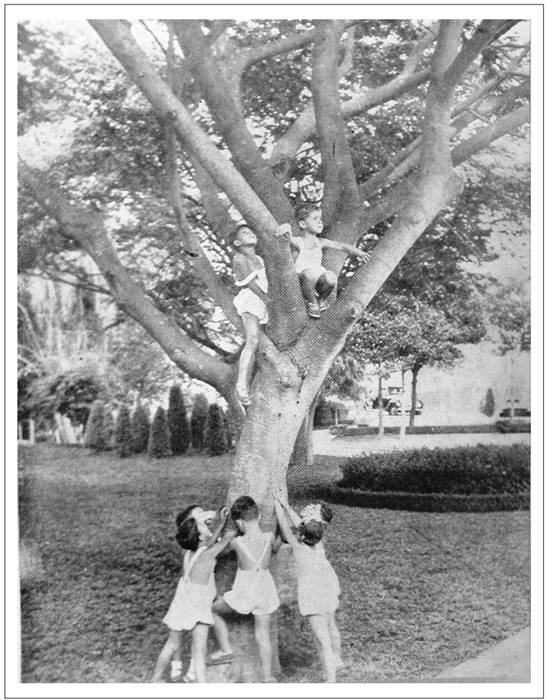

The Água Branca Park was given special attention in the decree, considered “excellent as an educational environment, for its beautiful and pleasant appearance, being spacious enough for outdoor activities, as well as having nurseries and other useful elements for the educator’s action” (SÃO PAULO, 1939b, p. 2). The furniture provided for the school, composed of light and portable blackboards and desks, would allow classes to be “given under the trees or in pleasant places to children” (SÃO PAULO, 1939b, p. 2). The Água Branca Park, administered by the Secretariat of Agriculture and where the Veterinary, Hunting and Fishing, Animal Production and other sections were located, had an area for agricultural exhibitions, fish tanks, stalls and even a small zoo. It was not a native reserve, but a park previously designed and fully implemented, from its constructions to its vegetation, also serving as public walk for those looking for an open-air redoubt amid industries and railroad tracks of the working district of Água Branca. Its Norman-style buildings made it quite picturesque and among the buildings in the park, none were specially designed to house a school. One of its buildings was adapted to receive the refectory, warehouse and classes on rainy days.

The use of the Água Branca Park by DPA, however, preceded the creation of OAAS. In 1937, the ESEF transferred its headquarters, as well as the school of infantile gymnastics that it managed, of the Park Dom Pedro II to the Água Branca Park (MENSAGEM, 1937). The school of gymnastics existed since 1934, that is, the initiative of an infantile school attached to ESEF was previous to OAAS (UMA ESCOLA, 1934). However, Edmundo de Carvalho granted it a new structure and organization in 1939, by adopting the precepts of outdoor education, a subject that he had been working on for years.

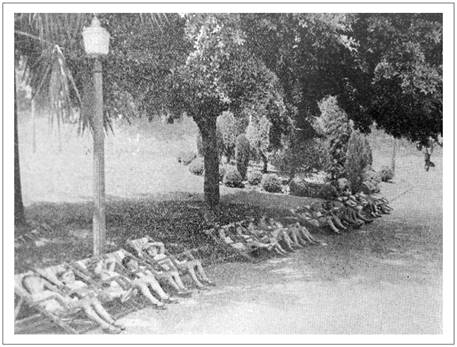

The inauguration of OAAS was specially planned to be held during the festivities of the Children’s Week. The solemnity was attended by authorities and was reported prominently by the newspaper Correio Paulistano, which transcribed in its pages part of the planned operation for the school in its creation decree (INICIARAM-SE, 1939). It seems that the same text also served as an inspiration for the propaganda brochure written by DPA later in 1942 and distributed to prefectures of the interior of the state of São Paulo (DEPARTAMENTO, 1943). The strategies adopted for the dissemination of the school were multiple. The plan of organization of the school, annexed to its creation decree, was also transcribed in the pages of the journal Revista de Educação Física and included a photograph taken from the daily life of the institution (ABADE, 1941). The photographs were also present in several editions of the Revista Brasileira de Educação Física, published between 1945 and 1949, some of which were chosen to compose three of their covers. In these magazines, OAAS was presented as a monument to the modernity of Brazilian physical education, as the great example and contribution of São Paulo, being announced as “the first of its kind created in Brazil” (ABADE, 1941, p. 24) or as a school “exemplary and unique of the kind in our country” (A ESCOLA, 1947, p. 27). It is thus noted that the DPA organized a real OAAS publicity campaign shortly after its inauguration. It used the text of his decree and the photographs taken from the school to affirm it as the great educational model of São Paulo in the field of physical and outdoor education. Most of its photographs made a point of presenting the children in outdoor environments, such as during meals, outdoor classes, games held during physical education, heliotherapy sessions and free time.

The school also achieved great success among the population of São Paulo, being popularly known by the affectionate nickname “Escolinha” (Little School). In the school year of 1942 the places for the enrollment of new students were drawn due to the great demand that existed and in 1944 already there was queue to obtain a vacancy (ESCOLA, 1942a, ESCOLA, 1942b, CRIANÇAS, 1944). The school began its activities in 1939 with about 50 students and ten years later the number was already at least 350 students (SÃO PAULO, 1949). Over the years, the São Paulo press continued to emphasize its functioning according to the text established in its creation decree and as a model school (A EDUCAÇÃO, 1946; AMEAÇADO, 1946). It is quite probable, however, that its daily school life has differed from that established by its official documents or even by what was disclosed in São Paulo press and in articles of specialized magazines. Unlike the medical and educational institutions that Edmundo de Carvalho helped inaugurate during the 1920s and 1930s, which served mainly the needy children, OAAS was not exclusively for the children of poor families. Apparently, shortly after its inauguration the profile of the public that went to attend school changed, favoring children of middle-class families of nearby neighborhoods. According to a report, the school served children who lived in “the (middle-class) neighborhoods of Perdizes, Lapa, Água Branca, Santa Cecilia, Barra Funda, Freguesia do Ó and others” (A PREFEITURA, 1949, p. 2). In 1952 it was already stated that it was only “a school with a large number of rich children” (ESCOLA, 1952, p. 5).

The parents of the students enrolled had great political articulation and were able to bring to the press and the legislative branches their protests at the times when the school was threatened with closure. The fact that OAAS was located in a space provided by the Department of Agriculture would bring some setbacks. For example, the school remained closed during the period of the agricultural and livestock exhibition which was in charge of the entire park (CRIANÇAS, 1944). Tighter winters also hampered its full operation, with the opening hours being reduced. At the end of 1946, parental protests against the closure of the institution began to appear in the press, more numerous, threatened by a request from the Department of Agriculture that sought to occupy the building in which the school was located. At the time, the mothers of the students went to Rio de Janeiro to plead to federal lawmakers to maintain the school (AMEAÇADO, 1946). Reopening requests for the school, which was closed for a few months, also reached the Legislative Assembly of the State of São Paulo, which allowed it to remain open inside the Água Branca Park (REABERTURA, 1947). Throughout the 1940s, there were other times when the school was in danger of being closed due to the plans of the Secretariat of Agriculture, but the political articulation of the students’ mothers prevented the closure of its activities, remaining open inside the park until 1952 (PERMANECERÁ, 1948, A ESCOLA, 1949, SÃO PAULO, 1949, INAUGURADA, 1952). From that date, it began to occupy a specially constructed school building in the vicinity of the park.

The location of the land for the construction of the school building was also controversial. The initial proposal was to use land in the Ipiranga neighborhood (PRIMEIRA, 1947, CONSTRUÇÃO, 1949). The protests were due to the fact that the place was very distant from the neighborhoods where the children who attended the school of the Água Branca Park lived (A PREFEITURA, 1949). In order to solve the impasses, a new land was chosen in the vicinity of the park. According to the mayor of the time, Asdrubal da Cunha, the intention was to construct not only a building to house OAAS, but a large center of recreation and culture, in which “a playground should be attached and, experimentally, [...] an agricultural learning field and a garden for a public walk. This public garden, as its installation is possible, may come with an ‘aquarium’ and an ‘aviary’ “(A PREFEITURA, 1949, p. 16). So, the ambitions looked great in 1949. In another project, referring to the creation of a Municipal Sports Commission, it was planned to construct 21 stadiums in the city of São Paulo, with an outdoor school attached to each, and that all private clubs should be “obliged to maintain playgrounds in the manner of the City Hall” (PRONTO, 1949, p. 12). It is possible that this idea was related to the open-air school, created in 1945 with the help of Edmundo de Carvalho, at the Pinheiros Sports Club, and, of course, the playgrounds run by the São Paulo City Hall (EDUCAÇÃO, 1945; MEMÓRIA, 2009). However, neither the education and culture center, nor the 21 stadiums with attached open-air schools and playgrounds were built. Nevertheless, controversies over the location of the new headquarters for OAAS, ended up with the definition of the land near Parque da Água Branca. The following year architect Roberto Goulart Tibau presented the project of the building to be constructed for OAAS.

The construction was part of an ambitious agreement between the City Hall and State Government, known as the School Agreement and whose purpose was to clear the deficit of classrooms in the city of São Paulo. The agreement was led by the architect Hélio de Queiroz Duarte, recently arrived from Bahia, where he had worked with the educator Anísio Teixeira on the projects of the park schools. The OAAS building was constructed in the second stage of the agreement (from 1948 to 1954), responsible for the construction of another 51 school buildings (ABREU, 2007). According to Caldeira (2005), the buildings constructed by the School Agreement in the city of São Paulo have unique characteristics, because the architects and engineers responsible for these projects have sought to materialize school buildings combining precepts of modern architecture produced in Rio de Janeiro with pedagogical concerns of Hélio Duarte, influenced by Anísio Teixeira, to create spaces closely related to new forms of education. As Faria Filho and Vidal (2000) pointed out while analyzing Brazilian school times and spaces, it was no longer the period marked by the model of the school-monument, but of a moment when the functional school model was in ascension. In general, the respective constructions broke up with the eclectic architectures of the majestic and austere school, giving way to a horizontal school, amid gardens and lawns and with large windows that allowed the entrance of sunlight. It was a modern architecture that reflected in concrete some ideas of pedagogical renewal of the period, with open, clean and simple traces, and that offered space propitious for the classes of physical education and for the moments of recreation.

Regarding the construction designed for OAAS by the architect Tibau, it counted with six classrooms open to private patios, specially designed for outdoor classes. According to Abreu (2007, p. 217), “his project was the only one of the agreement to apply the concept of ‘open-air classes’; in which all of the classrooms were integrated to patios of exclusive use through great frames”. In an interview given to researcher Caldeira (2005, p. 166), a colleague architect of Tibau describes the conceptions employed in the creation of the OAAS building project as follows:

Teachers sometimes, on beautiful days, taught outside. It was an innovation that only the School Agreement did, because it existed only in the United States and in Europe, France, and England. We saw all those books with nice buildings and fine plants, with glass down to the floor. We could never make them come to the floor here, for the engineer would not permit it. I had to stop at about 80, 90 cm or so of parapet. But we’ve got wide windows so there was no shade inside. [...] Ah, but this is the pre-school and, the kids play outside. They have classes out there.

Started up in the interior of the Água Branca Park, in a building adapted for its operation, OAAS offered its students the ideal of an education realized close to nature, in contact with sunlight, with open air and in the middle of gardens. However, it did not have a specific architecture for its outdoor education, something that was supplied by the building constructed in 1952. By appropriating foreign ideas, the School Agreement commission offered the possibility of pre-school classes continuing to have classes in the external environment and in all classrooms there were large windows allowing air circulation and abundant sunlight.

The ideas propagated about OAAS seem to have gained strength in the state of São Paulo in the early 1950s, since different deputies presented projects for the creation of open-air schools in the municipalities of Araraquara, São João da Boa Vista, Vera Cruz and Cotia (SÃO PAULO, 1952a, 1952b, 1953, 1954). It is possible that these actions were the result of the disclosure actions performed by the DPA. Apparently none of these projects were executed. As a result of changes in the Education Secretariat, OAAS ceased to be the responsibility of DPA and ESEF in 1955 and became known as the Experimental School Group. It continued to be a model school for a long time, but many of its spaces have been mischaracterized over the years, and its outdoor teaching was also restricted. Thus, a new period for the “Little School” has begone. In the words of Tibau:

Some small rooms have been built in connection to the outdoor rooms, and now it is all walled up, because it turned into a very busy area. Afterwards the Foundation for the Development of Education [FDE] built some strange blocks in the front, turning it into something... (CALDEIRA, 2005, p. 147)

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Open-air schools were born from a mixture between medicine and education, aimed at stopping the spread of tuberculosis and establishing pedagogical alternatives over more traditional school models. They have found fruitful ways of disseminating them in international congresses, and their knowledge has been diffused beside those of natural medicine, especially heliotherapy. They began to be debated by Brazilian professionals in the early 20th century, and the knowledge produced at international and national levels on open-air education were appropriated by doctors and educators in São Paulo, who were responsible for proposing and creating heterogeneous and diverse set of medical-educational institutions in the open air from the 1920s.

Throughout his career, Dr. Edmundo de Carvalho built a network of sociability linked to the fields of education, physical education and child care, which allowed him to propose and help create several medical and educational institutions in the open air in Sao Paulo city. The institutions he proposed and helped inaugurate were not mere copies of their counterparts abroad, but presented their own characteristics and were enriched from multiple voices. The longest project of Edmundo de Carvalho, was OAAS, which was put into operation as soon as he assumed the direction of DPA. It was a special moment to put into action its outdoor education projects, since the state of São Paulo and the Federal Government were investing heavily in the field of physical education.

Inaugurated in 1939, OAAS was announced as one of the main models of outdoor education in São Paulo, and its photographs and its creation decree were widely publicized in the São Paulo press, in specialized magazines and in publicity campaigns carried out by DPA. It served as an application and trainee field for ESEF and Normal School students from São Paulo. It achieved great success among the population, but, unlike the initiatives that Edmundo de Carvalho had undertaken in previous years, it did not exclusively serve underprivileged children. Its audience was formed mainly by children of families from the middle class of São Paulo, who had a great political articulation and managed to bring to the press and to the legislative powers their protests at the times when the school was threatened to be closed during the decade of 1940.

Created inside the Água Branca Park, in a building adapted for its operation, OAAS provided its students with all the ideals of an outdoor education, but did not have a specific architecture, something solved in 1952 with the building constructed by the School Agreement. It lasted as a model school for a long time, but its spaces had been gradually losing its characteristics, compromising its proposal of education in the open air.

Its history allows us to reflect on innovative outdoor education initiatives that are still little known in the history of Brazilian education. The recovery of such initiatives of the past help us to think about issues that touch the present time, especially regarding the possibilities of union of education with the outdoor life in the urban centers. The teachings offered by the history of OAAS tell us about innumerable possibilities of the school being a meeting place for children with nature (BARROS, 2018).

REFERENCES

ABREU, I. R. N. Convênio escolar: utopia construída. Dissertação (Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo), Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, A. M. de. Escolas ao ar livre e Colônias de férias: um corretivo para os débeis escolares. In: Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação, 8., 2015, Maringá. Anais do VIII Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação, Maringá: UEM, 2015, p. 1-11. [ Links ]

ARMUS, D. La ciudad impura: salud, tuberculosis y cultura en Buenos Aires 1870- 1950. Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2007. [ Links ]

ARMUS, D. Las colonias de vacaciones: de la higiene a la recreación. In.: SCHARAGRODSKY, P. (org.) Miradas médicas sobre la cultura física en Argentina (1880-1970). Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros, 2014. [ Links ]

BARROS, M. I. A. de. Desemparedamento da infância: a escola como lugar de encontro com a natureza. Rio de Janeiro: ALANA, 2018. [ Links ]

BAUBÉROT, A. Histoire du naturisme. Le mythe du retour à la nature. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2004. [ Links ]

BERMOND, M. T. A educação física escolar na Revista de Educação Física (1932- 1952): apropriações de Rousseau, Claparède e Dewey. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação Física), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2007. [ Links ]

BERTOLLI FILHO, C. História social da tuberculose e do tuberculoso: 1900-1950. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz, 2001. [ Links ]

BIZZOCCHI, C. E. Educação renovada no Estado de São Paulo: a experiência pioneira do ensino continuado e as práticas escolares do Experimental da Lapa (1961-1971). Cadernos de História da Educação, v.15, n. 2, p. 540-558, maio-ago. 2016. [ Links ]

CALDEIRA, M. H. de C. Arquitetura para educação: escolas públicas na cidade de São Paulo (1934-1962). Tese (Doutorado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo), Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2005. [ Links ]

CHÂTELET, A.-M. Le souffle du plein air. Histoire d’un projet pédagogique et architectural novateur (1904-1952). Genebra: Metis Presses, 2011. [ Links ]

CHÂTELET, A.-M. Le mouvement international des écoles de plein air. In: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXè siècle, Paris: Recherches, 2003. [ Links ]

CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXè siècle, Paris: Recherches, 2003. [ Links ]

DALBEN, A. Educação do corpo e vida ao ar livre: natureza e educação física em São Paulo (1930-1945). Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação Física), Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2009. [ Links ]

DALBEN, A. Mais do que energia, uma aventura do corpo: as colônias de férias escolares na América do Sul (1884-1950). Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2014. [ Links ]

DALBEN, A. Artes de curar: embates históricos entre as terapias naturais e os tratamentos alopáticos. In.: BARROS, R. C. de; MASINI, L. Sociedade e medicalização. Campinas: Pontes Editores, 2015a. [ Links ]

DALBEN, A. Inovações pedagógicas de uma educação do corpo ao ar livre: a Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre do Estado de São Paulo (1922-1956). In: Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação, 8, 2015, Maringá. Anais do VIII Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação, Maringá: UEM, 2015b, p.1-13. [ Links ]

DALBEN, A. Notas sobre a cidade de São Paulo e a natureza de seus parques urbanos. Urbana - Revista Eletrônica do Centro Interdisciplinar de Estudos da Cidade, v. 8, p. 3-27, 2016. [ Links ]

DALBEN, A. Las escuelas al aire libre en Uruguay: creación y circulación de saberes. Educación Física y Ciencia, 2019 (no prelo). [ Links ]

DEPAEPE, M. ; SIMON, F. Les écoles de plein air en Belgique. In.: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXè siècle, Paris: Recherches, 2003. [ Links ]

DI LISCIA, M. S. Colonias y escuelas de niños débiles: los instrumentos higiénicos para la eugenie. Argentina, 1910-1945. In.: DI LISCIA, M. S.; BOHOLAVSKY, E. (org.). Instituciones y formas de control social en América Latina, 1840-1940: una revisión. Buenos Aires: Prometeo, p.93-113, 2005. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, L.; VIDAL, D. G. Os tempos e os espaços escolares no processo de institucionalização da escola primária no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Educação, n.14, p.19-34, Mai./Ago. 2000. [ Links ]

GREENE, G. Nature, architecture, national regeneration: the airing out of French youth in open-air schools 1918-1939. Working Paper Series. Princeton, v.45, p.1-54, 2001. [ Links ]

GUTMAN, M.; CONINCK-SMITH, N. de. Designing modern childhoods: history, space, and the material culture of children. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2008. [ Links ]

HELLER, G. La cure intensive d’hygiène en Suisse. In: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXe siècle, Paris: Recherches , 2003. [ Links ]

JABLONKA, I. Les ambiguïtés du premier Congrès International des Écoles de plein air (1922). In: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXe siècle, Paris: Recherches , 2003. [ Links ]

KUHLMANN, M JÚNIOR . Processos de difusão do parque infantil e instituições congêneres no Brasil. In: Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação, 9., 2017, João Pessoa. Anais Eletrônicos do IX Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação. João Pessoa: UFPB, 2017, p. 165-176. [ Links ]

LIONETTI, L. Discursos y prácticas de docilización sobre las corporalidades anormales en Argentina en los albores del siglo XX. In.: SCHARAGRODSKY, P. (org.) Miradas médicas sobre la cultura física en Argentina (1880-1970). Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros, 2014. [ Links ]

LUC, J.-N. L’école de plein air : une histoire à découvrir. In.: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (rgs.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXè siècle, Paris: Recherches , 2003. [ Links ]

LUDWING, H. Les écoles de plein air en Allemagne, une forme de l’éducation nouvelle. In.: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXe siècle, Paris: Recherches , 2003. [ Links ]

MARTINEZ, J. M. B. De las escuelas al aire libre a las aulas de la naturaleza. AREAS: Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales, Murcia, n.20, 2000. [ Links ]

MASTROROSA, A. Departamento de Educação Física, Escola Superior de Educação Física e Associação dos Professores de Educação Física: o ordenamento da Educação Física no Estado de São Paulo no início da década de 1930. 2003. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2003. [ Links ]

MEMÓRIA MEMÓRIA Pinheirense. Pinheiros. v. 12, n.135, p.16, jun. 2009. [ Links ]

PASSOS, L. F.; FERREIRA, V. L.; MATTE, C. H. Escola Experimental da Lapa: a cultura material revelando uma experiência curricular renovadora. Anais do VII Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação. Cuiabá, 2013. [ Links ]

ROCHA, H. H. P. Entre o exame do corpo infantil e a conformação da norma racial: aspectos da atuação da Inspeção Médica Escolar em São Paulo. História, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 22, n. 2, p. 371-390, abr.-jun. 2015. [ Links ]

ROSENBERG, A. M. F. A. Guerra à peste branca: Clemente Ferreira e a “Liga Paulista contra a Tuberculose” 1899-1947. Dissertação (Mestrado em História Social) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2008. [ Links ]

RUCHAT, M. Jean Dupertuis (1886-1951). In.: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXè siècle, Paris: Recherches , 2003. [ Links ]

SALLES, M. P. de A. Servir São Paulo: 70 anos do Rotary Club de São Paulo. São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial do Estado, 1994. [ Links ]

SAVOYE, A. Écoles de plein air et éducation nouvelle en France (1920-1950). In.: CHÂTELET, A.-M.; LERCH, D.; LUC, J.-N. (org.). L’école de plein air: une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXe siècle, Paris: Recherches , 2003. [ Links ]

SIROST, O. La vie au grand air ou l’invention occidentale des milieux récréatifs. In.: SIROST, O. (org.). La vie au grand air. Aventures du corps et évasions vers la nature. Nancy: Presses Universitaires de Nancy, 2009. [ Links ]

SOARES, C. L. (org.). Uma educação pela natureza: a vida ao ar livre, o corpo e a ordem urbana. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2016. [ Links ]

THYSSEN, G. Boundlessly entangled: non-/human performances of education for health through open-air schools. Paedagogica Historica. v.54, n.5, pp. 659-676, 2018. [ Links ]

TIMÓTEO, J. P. A cidade de São Paulo em “escala humana”: Luiz de Anhaia Mello e sua proposta de recreio ativo e organizado. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2008. [ Links ]

UHLE, A. B. Comunhão leiga: o Rotary Club no Brasil. Tese (Doutorado em Educação), Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1991. [ Links ]

VILLARET, S. Naturisme et éducation corporelle. Des projets réformistes aux prises en compte politiques et éducatives (XIXe - milieu du XXe siècles). Paris: L’harmattan. 2005. [ Links ]

VILLARET, S. ; SAINT-MARTIN, J.-P. Écoles de plein air et naturisme: une innovation en milieu scolaire (1887-1935). Mouvement & Sport Sciences. v. 1, n. 51, p. 11-28, 2004. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

3º CONGRESSO 3º CONGRESSO de escolas ao ar livre. Revista de Educação. São Paulo, v. 17/18, p. 164-166, mar/jun. 1937. [ Links ]

A EDUCAÇÃO A EDUCAÇÃO da criança abandonada é um dos nossos maiores problemas. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 24 abr. 1946, p.1. [ Links ]

A ESCOLA A ESCOLA de Aplicação ao Ar Livre do Departamento de Educação Física do Estado de São Paulo. Revista Brasileira de Educação Física, Rio de Janeiro, p. 27, jan. 1947. [ Links ]

A ESCOLA A ESCOLA de Aplicação ao Ar Livre não será fechada e nem transferida. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 10 dez. 1949, p.12. [ Links ]

A INAUGURAÇÃO A INAUGURAÇÃO da primeira “Escola da Vida”. Correio Paulistano, São Paulo, 12 jun. 1935, p.11. [ Links ]

A QUESTÃO A QUESTÃO dos menores abandonados. Correio de São Paulo. São Paulo, 08 nov. 1933, p. 2. [ Links ]

A POSSE A POSSE solenne da Comissão Executiva e do Conselho Cooperador da Cruzada Nacional de Educação. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 16 dez. 1937, p.11. [ Links ]

A PREFEITURA A PREFEITURA instalará o Primeiro Centro de Aprendizagem Agrícola. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 28 ago. 1949, p. 16. [ Links ]

A REALIZAÇÃO A REALIZAÇÃO, em setembro, do grande certamen. Correio Paulistano São Paulo, 02 abr. 1929, p. 5. [ Links ]

ABADE, I. A. A Escola Superior de Educação Física de São Paulo e sua Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre. Revista de Educação Física, Rio de Janeiro, n.48, pp.24-27, set. 1941. [ Links ]

ACTOS ACTOS Officiais: Secretaria da Educação. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 15 jul. 1937, p.4. [ Links ]

AMARAL, J. F. do. Escolas ao ar livre: contribuição para o estudo do problema da higiene escolar em São Paulo. São Paulo: Est. Graphico Rossolillo, 1932. [ Links ]

AMEAÇADO AMEAÇADO de despejo um grande centro de educação infantil. A Noite, Rio de Janeiro, 11 dez 1946, p.1. [ Links ]

ASSOCIAÇÃO ASSOCIAÇÃO Paulista de Educação Physica. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 26 set. 1935, p.6. [ Links ]

AVULSOS AVULSOS: Posto Anti-Trachomatoso. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 24 mar. 1907. [ Links ]

BAILE BAILE á phantasia no Municipal. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 13 abr. 1922, p.3. [ Links ]

BANDEIRA BANDEIRA Paulista de Alphabetização. Correio de São Paulo. São Paulo, 25 jun. 1935, p.2. [ Links ]

CONFERENCIAS CONFERENCIAS médico sportivas. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 17 abr. 1929, p.6. [ Links ]

CONSTRUÇÃO CONSTRUÇÃO da ‘Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre’. Jornal de Notícias, São Paulo, 24 jun. 1949, p. 7. [ Links ]

CRIANÇAS CRIANÇAS infelizes. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 10 nov. 1944, p.2. [ Links ]

DEPARTAMENTO DEPARTAMENTO de Educação Física. Relatório de 1942. São Paulo: Secretaria da Educação e Saúde Pública do Estado de São Paulo, 1943. [ Links ]

DEPARTAMENTO DEPARTAMENTO de Educação Physica e suas actividades: uma aula de modelagem, dada as crianças da Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre, no Parque da Água Branca. Correio Paulistano São Paulo, 12 abr. 1940, p.4. [ Links ]

EDUCAÇÃO EDUCAÇÃO Física racional para a criança brasileira. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 27 jan. 1945, p.12. [ Links ]

EM PROL EM PROL de uma geração mais forte. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 30 mar. 1930, p.7. [ Links ]

ESCOLA ESCOLA da Vida. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 30 jun. 1935, p.4. [ Links ]

ESCOLA ESCOLA de Aplicação ao Ar Livre. Inscrição para sorteio. Correio Paulistano, São Paulo, 29 jan. 1942a, p.8. [ Links ]

ESCOLA ESCOLA de Aplicação ao Ar Livre. Correio Paulistano, São Paulo, 04 fev. 1942b, p.7. [ Links ]

ESCOLA ESCOLA de Aplicação ao Ar Livre. Correio Paulistano, São Paulo, 28 jun. 1952, p.5. [ Links ]

FAZENDO FAZENDO a felicidade dos desamparados da sorte. Correio de São Paulo. São Paulo, 13 jun. 1936, p.3. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, C. Congresso Internacional da Tuberculose (Paris - Outubro de 1905). São Paulo, Typografia do Diário Oficial, 1906. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, C. As escolas ao ar livre. Educação e Pediatria, Rio de Janeiro, v. 1, n. 5, p. 323-333, out. 1913. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, C. As escolas ao ar livre na luta contra a tuberculose na infância. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. Besnard Frères, 1929 [ Links ]

FOI EXONERADO FOI EXONERADO. Correio Paulistano São Paulo, 26 jun. 1925, p. 3. [ Links ]

FORAM FORAM contratados. Correio Paulistano São Paulo, 13 mar. 1942, p. 6. [ Links ]

FORÇA FORÇA Pública. Correio Paulistano São Paulo, 17 jul. 1914, p. 5. [ Links ]

HOSPEDES HOSPEDES e viajantes. Correio Paulistano.São Paulo, 21 abr. 1908. [ Links ]

INAUGURA-SE INAUGURA-SE hoje, ás 10 horas o « play-ground » do parque d. Pedro II. Diário Nacional, São Paulo, 23 dez. 1930, p. 7. [ Links ]

INAUGURADA INAUGURADA a primeira Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre do Brasil. Correio Paulistano, São Paulo, 23 nov. 1952, p.6. [ Links ]

INICIARAM INICIARAM-SE, hontem, em todo o Brasil, as commemorações da “Semana da Criança”. Correio Paulistano São Paulo, 12 out 1939, p.1. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO INSTITUTO de Cultura Physica da Infancia: uma obra patriotica. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 19 mar. 1923, capa. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO INSTITUTO de Cultura Physica da Infancia. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 10 fev. 1924, p. 2. [ Links ]

MELHOR MELHOR aproveitamento do “playground” do parque Pedro II. A grande praça de recreio infantil será confiada a Cruzada Pró-Infância. Diário Nacional, São Paulo, 19 mar. 1931 p. 5. [ Links ]

MELLO, B. V. de. Escolas ao ar livre e colônias de férias para débeis. Escolas especiais para tardos. São Paulo: Inspeção Médica Escolar do Estado de São Paulo, 1917. [ Links ]

MENDES, A. Palestras educativas. Educação. São Paulo, v. 8, n. 3, p. 291-293, set. 1929. [ Links ]

MENSAGEM MENSAGEM apresentada pelo governador J. J. Cardozo de Mello Neto á Assembléa Legislativa de São Paulo a 9 de julho de 1937. São Paulo: Empreza Graphica da Revista dos Tribunaes, 1937. [ Links ]

MONCORVO, A FILHO . Os primeiros ensaios de heliotherapia no Brazil. In.: CONGRESSO Americano da Criança: Comité Nacional Brazileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, v.1, p.293-301, 1917. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, H. G. Resumo histórico do Rotary Club de São Paulo (1924-1955). São Paulo: Oficinas Gráficas de Saraiva S. A., 1955. [ Links ]

UMA ENCANTADORANA ASS. Christã de Moços. Diário Nacional. São Paulo, 26 jan. 1929, p.6. [ Links ]

UMA ENCANTADORA NOS DOMÍNIOS da Instrucção Publica: por fóra bella vióla... Diário Nacional. São Paulo, 08 dez. 1929, p.8. [ Links ]

UMA ENCANTADORA O ENSINO da educação physica na Força Pública. Correio Paulistano São Paulo, 10 abr. 1922, p.3. [ Links ]

OCULISTAS . Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 24 dez. 1909. [ Links ]

PARA A FELICIDADE PARA A FELICIDADE dos dias de amanhã. Correio de São Paulo São Paulo, 26 jul. 1935, p.2. [ Links ]

PARA O SORRISO PARA O SORRISO da vida de amanhã. Correio de São Paulo São Paulo, 19 jul. 1935, capa. [ Links ]

PELA SAÚDE PELA SAÚDE e pela raça: Instituto de Cultura Physica da Infancia. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 11 abr. 1924, p. 4. [ Links ]

PRIMEIRA PRIMEIRA Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 31 jul. 1947, p. 8. [ Links ]

PRONTO PRONTO o substitutivo ao projeto sobre esportes. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 14 set. 1949, p. 12. [ Links ]

PERMANECERÁ PERMANECERÁ na Água Branca a Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 22 ago. 1948, p. 16. [ Links ]

REABERTURA REABERTURA da escolinha da Água Branca. Jornal de Notícias. São Paulo, 03 abr. 1947, p. 3. [ Links ]

ROTARY Club ROTARY Club. Diário Nacional. São Paulo, 08 jun. 1929, p. 5. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Lei no. 1.596, 29 de dezembro de 1917. Reorganiza o Serviço Sanitário do Estado, 1917. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Decreto no. 10.243, 30 de maio de 1939. Dispõe sobre a educação física no estado, 1939a. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Decreto no. 10.307, 13 de junho de 1939. Cria uma Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre, 1939b. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Projeto de Lei no. 1.121, de 1952. Cria uma escola de aplicação ao ar livre em Araraquara, 1952a. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Projeto de Lei no. 1.196, de 1952. Cria uma escola de aplicação ao ar livre em São João da Boa Vista e dá outras providências, 1952b. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Projeto de Lei no. 493, de 1953. Cria Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre em Vera Cruz, 1953. [ Links ]

UMA ENCANTADORA (Estado). Projeto de Lei no. 1.196, de 1952. Cria uma escola de aplicação ao ar livre no distrito de Itapevi, no município de Cotia, 1954. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Decreto no. 24.410, 16 de março de 1955. Dispõe sobre a subordinação da Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre à Secretaria de Estado da Educação, 1955a. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Decreto no. 24.430, 23 de março de 1955. Dispõe sobre a criação do Grupo Escolar Experimental, 1955b. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Município). Lei no. 2553, 21 de outubro de 1922. Auctoriza a prefeitura a ceder, a titulo gratuito, o uso e goso de um terreno do patrimonio municipal, á avenida agua branca, para a installação e funccionamento do “instituto de cultura physica da infancia”, 1922. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Município). Lei no. 3371, 21 de agosto de 1929. Autoriza o prefeito a subvencionar com a quantia de 120:000$000 o Instituto de Cultura Physica da Infancia, para a construcção de um “play ground”, no Parque D. Pedro II, e dá outras providências, 1929. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Município). Projeto de Lei no. 156, de 1949. Autoriza a construção de prédio para a instalação da Escola de Aplicação ao Ar Livre, 1949. [ Links ]

TOMOU TOMOU posse, hontem, o director interino do Departamento de Educação Physica. Correio Paulistano. São Paulo, 10 ago. 1938, p. 2. [ Links ]

UMA ENCANTADORA UMA ENCANTADORA festa infantil. Correio de São Paulo. São Paulo, 15 out. 1935, capa. [ Links ]

UMA ESCOLA UMA ESCOLA de gymnatica infantil: a nova iniciativa do Departamento de Educação Physica. Correio de São Paulo. São Paulo, 25 ago. 1934, p.1. [ Links ]

Received: February 07, 2019; Accepted: April 18, 2019

texto em

texto em