THE PALESTRA OF DEAUVILLE: TRAINING CENTRE, RUSTIC VILLAGE OR HOLIDAY CAMP?

Films on the work of Georges Hébert are not easy to find. However in 1991, a documentary produced by the French Federation of Physical Education and Voluntary Gymnastics (FFEPGV) offers a compilation of several extracts: the naval fusiliers of Lorient (1908), the College of Athletes of Reims (1913), a demonstration of naval fusiliers at Blois (1922), the Palestra of Deauville (1925), an example of a natural method lesson (undated), a natural method work-out session (undated), and a swimming lesson (undated). These films show some of the communities in France that were influenced by the work of Georges Hébert during the first half of the twentieth century: the army (navy), and public and private schools. The documentary was conceived by the French Commission for Historical Studies composed of Guy Bonhomme, Raymond Dinety, Bertrand During, Alain Le Guiner, René Meunier and Sylvie Huvot (secretary). The film was made by Alain Le Guiner and edited by Saliou Diallo of the Audiovisual Office of the University of Poitiers. It is important to note that this is not a film made by the Hebertists themselves. The FFEPGV is a federation that was formed as a result of a physical education method developed by Philippe Tissié (1852-1935), called voluntary gymnastics, which is the historical opponent of the Hébert’s natural gymnastics. This is what the commentator in the documentary says about the Palestra:

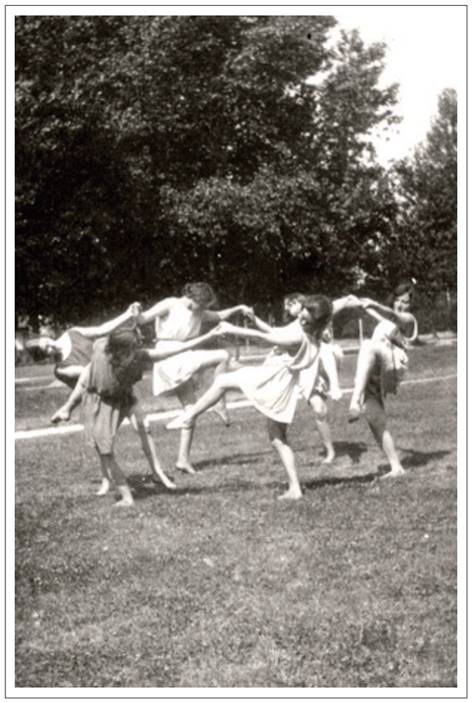

In 1925 Georges Hébert created the Palestra: an outdoor training centre for girls. Their short tunic outfits are inspired by antiquity and make it easier for the young girls to do the exercises. These exercises correspond to sports practice on an outdoors parcours. These physical exercises are by their nature and by the setting in which they take place an innovation for gymnastics for women that existed at the time. The session ends with rhythmic movements and dance. Referring to statues of women of the Antiquity, Hébert was of the view that the female body must have sufficient and balanced muscular development. (LE GUINIER, 1991)

Let us start with the factual date: the Palestra was not created in 1925, but in 1918. Also, although the exercises at the Palestra may have the appearance of sport exercises, they are not executed in that spirit. The Palestra, we will come back to this in more detail later, is simply not a sports center. What is more, Georges Hébert publicly condemned sport after the Olympic Games in Paris in 1924. His view was that sport is corrupted, not educational and immoral, because of issues such as professionalisation of sport, merchandising and - what he felt - unnecessary public exposure of the body of the athletes (Hebert, 1925). It is unfortunate that the documentary does not provide more information on the inspiration that Georges Hébert found in the Hellenic period, why the method of the Hebertists was so original, or what made the Hebertist “rhythmic movements and dance” so different from those of Isadora Duncan ( 1877-1927), Raymond Duncan (1874-1966), Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865-1950) by Georges Demenÿ (1850-1917) or Irène Popard (1884-1950).

Ten years after the documentary of the FFEPGV, Michel Rainis revisits the Palestra in his thesis on the rise of leisure activities on the Atlantic coast of France (1998). He recognises that the Palestra was created by Georges Hébert in 1919 at the seaside in Bénerville, near Deauville - for convenience we will call it the Palestra of Deauville - to continue the physical education of women and children that he had started at the Collège d’Athletes of Reims (FROISSART, SAINT-MARTIN, 2014) in 1913. Georges Hébert’s focus at the College had been on training female instructors of physical education to introduce his natural method in all schools and hospices of the city of Reims. But the destruction of the College by German bombings during the 1914-1918 war puts an end to the natural physical education of the children of Rheims. Nevertheless, while Georges Hébert focuses on the physical rehabilitation of soldiers during the war (PHILIPPE-MEDEN, 2018), the Hebertist female instructors remain in contact in Paris and join the Palestra project in 1918. Director of the Palestra is Yvonne Moreau, former student of Georges Demenÿ; then later instructor and head of the college for physical education for women and the future Mrs Hébert - Georges Hébert will marry her in 1924. According to Michel Rainis, there are currently no primary sources to confirm this, Georges Hébert would have based the Palestra on the model of US institutions of regimentation sports for girls:

This palestra is actually a training camp or rustic village, in a park located at the edge of the beach. It consists of a large stadium for athletic activities and a smaller stadium with a thinner pitch for dancing. The Palestra has a third stadium that includes tennis and basketball courts. This initiative is reserved for children from good families, the establishment is serious and charges fees [...]. (RAINIS, 2001, 90)

Still according to Michel Rainis, the winter activities of the Palestra de Deauville are moved to the south of France, near Hyère - he does not specify the exact location, but from our own research we know that the Palestra rented the Château des Bormettes at La Londe-les-Maures - a few hundred meters from the beach. Michel Rainis stresses that the Palestra is not a resort or a summer camp, as there are very strict regulations and time schedules, compulsory physical and artistic activities, and supervised entrance and exit areas. He quotes Georges Hébert: the Palestra is a school of physical, mental, aesthetic and moral education, with a programme consisting not only of outdoor exercises, instrumental music lessons, singing and dancing, but also gardening and other manual tasks. It is surprising that Michel Rainis uses the word “school” for the centre although he does not mention courses on intellectual culture. The description of the Palestra by Michel Rainis is an approximation, and as we will explain later, underestimating some aspects that will help us understand Georges Hébert’s work. For example, when he approaches the nautical extension of the Palestra:

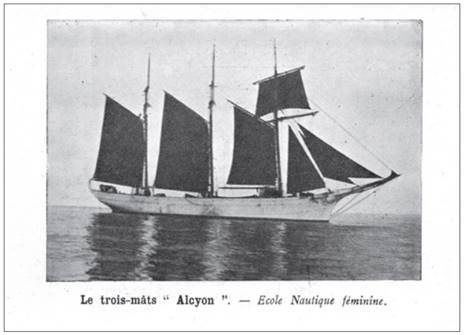

aboard the ship Alcyon [a three-masted schooner to be precise] the young girls receive education for physical, vigorous and moral abilities as well as seafaring skills. The Palestra paints an idyllic imageof a well-shaped and cultivated woman who loves dancing and singing, while the cruises on the Alcyon take her to exotic and unusual destinations. (RAINIS, 2001, 92)

Was the aim of the Hebertist physical education really to train women with a well-trained, beautiful body, able to entertain with charming dancing and singing skills, and who would have the financial means to go on exotic cruises? That would mean that Georges Hébert did not follow his own doctrine: “be strong, be useful”!

Note : In this representation of the Palestra, Georges Hébert seems to be « parading » surrounded by the female instructors which gives more the impression of a harem than a physical education training centre. It is likely that this illustration may have caused misunderstandings about the work of Georges Hébert.

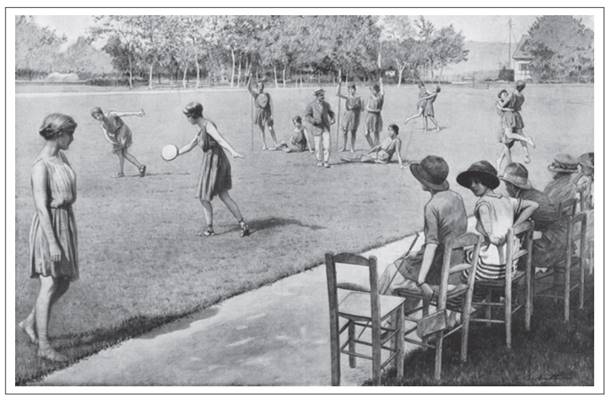

Image 1 « A lively fresco by Puvis de Chavannes that shows how only steps away from fancy Deauville, naval commander Hébert reintroduces the art of correct posture and harmonious movement. At the centre, Mr Georges Hébert is seen directing demonstration exercises by the female instructors of the Palestra ». Drawing by Louis Rémy Sabattier (1863-1935) published in the newspaper L’Illustration of 30 August 1919. Private collection.

In another study entitled Naturisme et Éducation Physique (2005), Sylvain Villaret correctly dates the creation of Palestra to 1918. He gives a more nuanced picture of the Palestra, which he says is initially “a holiday camp” to become later a physical education college for women and children. He notes that the commercial success of Palestra enables Georges Hébert to open a gymnasium in Paris, but provides no further details. We have not been able to find information that Georges Hébert would have bought a gymnasium with profits from the Palestra. According to Sylvain Villaret the Palestra’s “ primary function is to raise funds not only to finance its promotional actions but more trivially to ensure his subsistence [Georges Hébert]”. Even though he acknowledges that the Palestra’s role as “flagship” of Hebertist natural method” becomes stronger over time,” he believes that it only served as an “advertising display” for “mundane Deauville”. (VILLARET, 2005, 212). The visit of HE Alfonso XIII, King of Spain, to the Palestra would illustrate this. Georges Hébert’s development of a natural method initiative at the Palestra is seen by Villaret as “an advertising argument”:

sometimes strengthening the liberating aspect of the Palestra, sometimes their hedonistic function or their educational vocation. [...] Life at Palestra is a therapy in nature. [...] [Outdoor] training gives (…) a blast of fresh air because of the increase in oxygen supply. [...] Hydrotherapy activities can be summed up as bathing, performing ablutions after each training session and learning to swim in the sea (...). Every day, the swimming lesson is followed by sunbathing on the beach. Special attention is given to alimentation. Snacks are made from natural ingredients and dishes are cooked as little as possible, excluding any industrial ingredients. Vegetables and salads make up the basis of all meals and come from the kitchen gardens that are on the grounds of the Palestra. (Id., 2013-214).

Of course, Sylvain Villaret is right about the economic importance of the Palestre, but it is much more than that and he gives us a hint of this: “[T] he Palestrian is educated in the naturism of the” renovator of the Greco-Latin tradition”, which is the subject of a real teaching method.”(Id., 214). Unfortunately, he does not explore this further, so that the reader cannot understand the fundamentals of the Hebertist doctrine and practices. At best his study allows us to understand that the Palestra is an institution that is a precursor of the natural treatments of the 1930s: it “substitutes a natural therapy, reserved for sanatoriums, treatment and rest homes, with a natural application for leisure activities and physical education. (Id.). Jean-Michel Delaplace adds:

What was a mere training camp (...) in 1918, becomes (...), thanks to an economic climate that allowed the rise of leisure activities, a real luxury holiday centre. [...] Hedonism and natural lifestyle: these are the two pillars on which rests the success of the Palestra [...]. The Palestra and its physical education of women allowed Hébert to recover funds to finance the activities promoting his method. [...] To be a pupil in Deauville is (...) a vocation! [...] much of the time of each stay is devoted to public demonstrations and embellishing the place (...). [...] we can ask ourselves whether the Palestra was an instrument of social emancipation of women through physical activity or the very symbol of their alienation and the perpetuation of a phallocratic social order. (DELAPLACE, 2005, pp. 173-180)

According to Jean-Michel Delaplace, Georges Hébert’s Palestra aspired to being emancipatory in 1919, but would become reactionary in 1925: “it is really the alienation of the woman to the man that is being programmed by Mr and Mrs Hébert. The interiorisation of the woman’s inferiority from the earliest childhood, the subtle, unconscious inculcation of a system of unequal relations, this is the solution proposed by Yvonne Hébert, a position shared - inspired? - by her husband (...). “(Id., 183). Going so far as to say that Georges Hébert makes “his students pose naked”, “shamelessly”, “ Jean-Michel Delaplace is only one step away from describing Hébert as a pimp! The descriptive analysis that we conducted of the history of Palestra and more broadly of the work of Georges Hébert (PHILIPPE-MEDEN, 2017) is leading to different conclusions than those of the research above.

HEBERTIST SOCIETY, DANCE AND FEMINISM AT THE PALESTRA

The Palestra is mentioned for the first time in an article in the 15 July 1924 edition (number 23) of Physical Education, the journal that promotes Hebertism in France (PHILIPPE-MEDEN, 2014). The definition in the article helps us understand the Palestra better as a “college of exercise for women and children”. The founder of the college is Georges Hébert, but the director is Yvonne Hébert whose career has never been the subject of research. The history of physical education and sport has paid little attention to the involvement of women in physical education. Contrary to the other female Hebertist instructors who usually remain anonymous; Yvonne Hébert’s name is mentioned but otherwise very little is known about her. She attended Georges Demenÿ’s advanced physical education classes, and as a gymnast of the early 20th century she was aware of the growing interest in the physiology of movement as well as the hygienic, aesthetic, energetic and moral effects of exercise. From 1913 onwards, she leads physical education training at the College of Reims to girls of varying physical constitution, character and national origin with the aim to make them not only more robust but prepare them for every-day challenges. As the Chief Instructor at the College of Athletes of Reims, she led a train the trainers programme to ensure continuity of the physical education training method at several institutions during the 1914-1918 war: the asylum of Semoy (1914), the public schools and upper primary schools of Orleans (1914), the female teacher training school and the public schools of Aurillac (1916-1918), the public schools of Cherbourg and the Protestant sanatorium of Arcachon (1917- 1918).

Note : From 1922, the cover of the journal L’Éducation Physiquefrequently features pictures of exercising women. In the1920s-1930s, women have had access to sport leisure activities for quite a while now, and they are no longer restricted to playing tennis while wearing a lace corset and flowery sun hat. Violette Morris (1893-1944) for instance was a French athlete. The Hebertist female instructors, however, do not practice sport, but exercise outdoors with what is at hand in nature: here an example of throwing a log exercise on the island of Noirmoutier. The short tunics (they were orange) prompt images of ancient Hellas.

Image 2 Cover of an edition of the journal L’Éducation Physique. Private collection

The Palestra led by Yvonne Hébert is equipped with a variety of sports facilities. A map shows a center aisle within its enclosure that leads to a large training stadium equipped with climbing exercise structures, poles, bars and spaces for the shot put, the whole girdled by a 217-meter running track. This stadium is separated from another one for rhythmic dances, an 80-meter long straight track and further down two vegetable gardens. There is a third stadium: the sports games stadium, consisting of a tennis court, a basketball court and a 250-meter circular obstacle course. The total area, which was landscaped by Édouard Redont (1862-1942) covers 17,265 square meters.

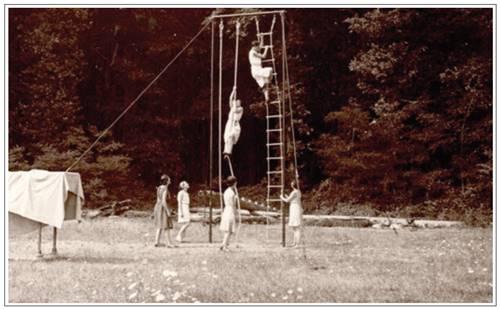

Note : Climbing a slack rope is a classic Hebertist exercise to develop stronger arms. As we can see on this photo, the Palestra was surrounded by green vegetation and trees

Image 3 Climbing exercise on the big training stadium. Undated. Private collection

The aim of the Palestra is originally to perfect the training of female instructors with knowledge on specific aspects of physical education: « [t] he teachers did an internship at the Palestra of Deauville, led by Master Hébert. (ARDENNE, 1924, p.6) However, by 1928, the Palestra directed by Yvonne Hébert becomes the only place in France where a young woman can be trained and exercise if she wants to prepare herself for the Certificate of Fitness to Teach Gymnastics (Elementary and Higher). The sports facilities, the time schedule of the training and the content of the Hebertist curriculum, show that the Palestra was not a sports camp or one of the holiday resorts that flourished with the emergence of leisure in France» (CORBIN, 1995).

The content of the Hebertist teaching as it is presented in the journal Éducation Physique demonstrates this. The curriculum is subdivided into six fundamental teachings that are interlinked and form a holistic model of physical education pedagogy:

A complete Natural Method training of the 10 groups of exercises that constitute the Hebertist body techniques, preferably in a specially arranged space in nature: walking, running, jumping, climbing, carrying, throwing, swimming, self-defence, quadrupedia and balace exercises.

Common manual work techniques: cleaning, cooking, gardening, levelling, building and maintaining appliances, etc.

Spiritual and moral development: mental gymnastics, reflective thinking and self-awareness, civic engagement, etc.

Intellectual development: study of the precursors of physical education (Rabelais, Tissot, Andry, Amoros, Demenÿ, etc.), knowledge of other existing body techniques (Swedish gymnastics, harmonic gymnastics, organic gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics, respiratory gymnastics, games: tennis and basketball, etc.), the sciences (anatomy, physiology, criticism of scientism).

An aesthetic culture: literature (travellers’ stories from ancient France: Jacques Cartier, Gabriel Sagard Theodat, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, etc., and contemporary explorers: Abel Faivre, Henry Lhote, Norbert Casteret, etc.); mythology and the body (Atlantean history); representation of physical movement and gestures in the history of art; circus exercises; dance (rhythmic) and music (instruments: harp, tambourines, flutes).

Health and nature: history of hygiene, camping, exercise as medicine (correct dose, choice of exercise), diet (vegetarianism) and natural elements (hydrotherapy, air therapy, heliotherapy).

The implementation of such a programme requires rigorous organisation as is shown from this day schedule at the Palestra below:

07 :00 - Wake-up call, getting washed and dressed, cleaning the rooms.

07 :50 - Roundup. A quick, short run through the forest.

08 :15 - Breakfast.

08 :30 - 09 :15 - Roundup. Small housekeeping and gardening tasks.

09 :15 - 10 :00 - Complete physical training class.

10 :00 - 10 :15 - Break.

10 :15 - 11 :30 - Completion of earlier manual tasks or starting new ones such as sewing, cooking, etc.

11 :30 - 12 :15 - Rest, except for the girls in charge of designated tasks.

12 :15 - 14 :15 - Lunch and rest.

14 :15 - 16 :00 - Classes on topics related to physical education, hygiene, art, ancient history, etc.

16 :00 - 16 :30 - Variety of games or in particular throwing games.

16 :30 - 16 :45 - Afternoon tea.

16 :45 - 18 :00 - Rhythmic dances and songs.

18 :00. - 19 :30 - Rest.

19 :30 - Dinner.

20 :30. - Meeting in the hall. Reading. Parlour games.

Once or twice a week : outdoor explorations. (STROHL, 1926)

The general idea of the programme is to prepare the girls for everyday life and to be independent in case they find themselves on their own one day.

Note: A short running exercise with swift pace through the forest. We can see Yvonne Hébert on the left

Image 4 : Running exercise. Undated. Private collection

Dance is only of secondary interest in this resilience-building programme. Yvonne Hébert does consider it important enough to promote the Palestra’s innovative teaching method. Every week, two demonstrations of - what are called - natural and non-rhythmic dances are held at the Palestra for an audience from Deauville potentially interested in physical education. Men are not allowed at the Palestra, apart from fathers of students and some prestigious visitors such as HE Alfonso XIII, King of Spain interested in the Hebertist teachings. The Hebertists are very critical of the Duncan’s Hellenic gymnastics, Demenÿ-Popard’s harmonic gymnastics and Jaques-Dalcroze’s rhythmic gymnastics.

For instance, the Hebertists see rhythmic gymnastics as composed of asymmetrical movements or complex associations, “poly-dexterity” as Georges Hébert calls it, that are not useful. A criticism voiced at a conference with the theme Our Movements. How we execute them, how we must learn them (Bulletin of the General Institute of Psychology), that these movements and associations can wear out the brain or overload the nervous system “to making an unusual effort, diluting efforts, or exceeding its normal potential “:

An example of these complicated associations can be found in certain exercises that transform music into gestures, a process that requires mental or nervous system operations to be performed almost simultaneously as follows: listening to the music, mentally translating the music into gestures, and coordinating and executing these gestures. The nervous system must remain alert the whole time to perform almost simultaneous tasks: on the one hand listening to and interpreting music, and on the other hand associating and executing. (Hebert, 1941, 403)

It is interesting to note that the experiments at the Palestra are based on empiricism but that they do not exclude scientific work, more particularly in this case, movement psychology.

Note : The natural dance movements at the Palestra look very similar to the movements of Duncan’s Hellenic dance or Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s rhythmic dance, but the music in natural dance follows the movements, not the other way around

Image 5 Natural dance at the Palestra. Undated. Private collection .

In contrast with rhythmic dance movements that usually consist of geometric movements, the natural dance of the Palestra transforms natural movements (walking, running, jumping, carrying, throwing, etc.) to stylised dance movements. Also, music in natural dance always accompanies the movements, and does not control them as is the case for rhythmic dance. Life in a community of women allowed Yvonne Hébert to study the behaviour of a rhythmic dancer who stayed at the Palestra for a short while:

In rhythm, [the rhythmic dancer] was taught to “liberate herself” and to be inhabited by the rhythm. Also indulge without restraint to all the extravagances of gestures and mime. This means that the nervous system will work intensively. We have personally observed that some rhythmic dancers beat all records in terms of manifesting nervous system overload. (Hebert, 1925, 12).

At the Palestra, and this is also valid for Hebertism in general, the purpose of dance classes is not to train dancers, but to provide female athletes with complementary awareness of aesthetics and movement and to teach them to build a relationship with an audience.

Earlier writings about the Palestra have referred to the pure and rustic lifestyle under Yvonne Hébert’s direction, but do not put enough emphasis on the importance of this almost mystical search for ascetiscim in Hebertism: “living in a community, at these Palestras, with teaching given all year round in the outdoors, in full nature, and in conditions that encourage these personalities to reveal their true nature and remove all masks and artifices. (Hebert, 1924, 7)

From 1919 to April 1925, nearly 2,000 girls attended the Palestra classes. Of those, 154 aged 15 to 33 stayed there for a period of about 6 weeks, sometimes up to 3 months and on occasion a full year. The price for one month of daily classes for an external pupil is 350 francs; a two-week stay at the Palestra 450 costs francs. The Palestra is an international community with young women and girls from Ireland, Norway, the United States, etc.

The Palestra receives support from feminists, including Doctor Jeanne Guyot who talks of the beneficial effects of a three-month camp that she has experienced first-hand and has witnessed also on girls that she has met while she was recovering. Those effects are correction of stooped postures, weight gain for skinny girls, weight loss for those who are obese, an increase in muscular definition and widened thorax. Heavy menstrual bleeding is diminished, the severity of dysmenorrhea (menstrual pain) reduced and even removed. In a short period of time, those in convalescence, suffering from anaemia, the overworked and the depressed find back their lost strength, resilience and enthusiasm and become cheerful again. (GUYOT, 1923) The feminist lawyer Suzanne Grinberg (1889-1972) also endorses the Palestra of female athletes of Hébert for the physical education of women, for the training in group, the training outfit and improving posture and graceful movement.

Some young female athletes of the Palestra will embark on bold adventures. After their training at the Palestra, Marthe Oulié (1901-1941) and Hermine de Saussure (1901-1984) decide in 1924 to board the Perlette, a small sailboat without an engine, and will cover more than 1700 nautical miles at the Aegean Sea! These twenty-year-old students from the École du Louvre who lead an anthropological and archaeological expedition put into practice the Hebertist slogan: “Be strong, be useful” and are an example of female emancipation in France in the 1920-30’s. They say that the Hebertist training has made them robust, vigorous, in full self-control and able to discard what is useless. (HOULIÉ, DE SAUSSURE, 1925).

Note : Nautical school for women founded by Georges Hébert in 1929.

Image 6 : Postcard of the Alcyon. Undated. Private collection.

This seafaring success encourages Georges Hébert to add to the Palestra of Deauville a nautical palestra, on board of the Alcyon, a three-masted 160-ton sailing vessel equipped with a motor that travels, depending on the time of the year, the Channel, the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Once again, in 1929, the Hebertist pedagogy will repeat the experiences of the Perlette in 1925 and the Palestra in 1919, and build both body and character. In the first year, this unique experience attracts about fifty girls for a training that is not a sports experience, but fundamentally Hebertist.

IMAGINARY AND SPIRITUALITY OF THE BODY OF THE ATHLETE OF PALESTRA

The French imaginery of the inter-war period very soon starts comparing the female athletes to the mythical Amazons who formed and ruled their own communities without men, and even fought against men and defeated them:

We know of women who confronted with natural life challenges can transform and become physically stronger for their survival, and in parallel, women in normal life too can develop vigorous and moral strengths; we believe that the achievements of the Amazons do not only exist in legends. (STROHL, 1925, 24)

The Amazons of the Parthenon Friezes, the Amazone of Epidaurus, and those of the Capitol ... were a source of inspiration for the Hebertists’ aesthetic ideal. The female athletes of the Palestra have a body that is an improved version of masculine characteristics: angularity and lack of grace, and feminine characteristics: softness and lack of strength.

This imageof the Amazons can undoubtedly be explained by the fact that starting with the war of 1914-1918, women take part in the battles and dangers that only the male combatants used to be exposed to before: examples are the English female ambulance drivers, the Russian female soldiers trained by former non-commissioned officers of the Imperial Guard (1917), the Polish Women’s Battalion of the Kulczyny Training Camp (1920), and the Palestinian Women’s Squadron against the abduction of women in Palestine (1925) (DENIS, 1925). The Hebertists believe that if women and men execute the same physical exercises on a regular basis, their bodies become equal in strength (VERDAL, 1934, 59).

In fact, the Hebertists refer to the ancient/classic ideal “muscular development and physical beauty” which represents women and men of almost identical physical built, as is demonstrated by the following description of Mycerinus and two goddesses (2548-2530 BC):

The torso, overall, is flat, with broad shoulders, the pectorals firmly attached, the abdominals well developed (...). The upper limbs, the flexibility of the deltoid, the biceps, and the triceps, clearly show the length of the Egyptian muscle. The anatomical areas of the lower limbs are always accurately defined with some exaggeration, however, in the projection of the inner edge of the soleus. These observations are valid also for the female nude and confirm that the measurements and muscular development are almost identical if the man and the woman, practice the same activities and exercises. The woman’s breasts are always perfect: small, hemispherical or slightly conical (...), well-shaped, firmly attached to the pectorals and seem to be part of these muscles. (STROHL, 1937, p. 131-132).

Ephebe of Volubilis (5th century BC) and the Venus of Milo (130-100 AD) are the embodiments of physical beauty in ancient Greece.

The Ephebe of Volubilis has a slender and well-developed musculature: well-shaped, broad chest and powerful but not inflated pectorals. The vertebral line is at the bottom of the groove formed by the dorsal and lumbar spines. The deltoid fully covers a fleshy shoulder, well placed and leaving the chest open. Ephebe has an elongated built but he knows how to move well in space (STROHL, 1929, 230). The Venus of Milo has an ideal body that is not deformed by a corset or lack of activity. The total width of the bust is larger than that of the pelvis. The muscles have slightly fleshy shape. Tiny fat folds soften the fascial insertion lines, a sign of a momentary rest period in training (STROHL, 1938).

The body of the female athletes of the Palestra resembles that of statues of ancient Greece. The lower limbs are impeccably defined, the toes are not deformed from wearing shoes; and the abdominal muscles are well-shaped. The muscular development of their upper limbs is more fleshy than in most Hebertist men, but distinctly visible. Finally, in correct standing position, the wide shoulders prevent the arms from being hindered by the hips. (Hebert, 1919). This Hebertist appreciation of the human body would be part of a tradition of Greco-Latin naturism by the attention paid to its aesthetics in the sense of the word: aesthesis. Greek word meaning: sense, faculty of feeling.

In line with the aesthetic theory of John Ruskin (1819-1900), and his religion of beauty (SIZERANNE, 1899), the Hebertist conception of the body of the female athlete of the Palestra is that it is a living mechanism that acts and moves, blushes and grows pale, shivers and thrives in the open air. This is not a body as you find it in anatomical studies of the human body, with the skin removed and exposed by dissection and vivisection (MANDRESSI, 2003). It is not trained with analytical gymnastics exercises, movements that are scientifically regulated and repeated for local effect, but it is able to move around in nature, executing manual tasks outdoors regardless whether it is rainy or sunny. (STROHL, 1937) The Hebertist teaching at the Palestra preaches a spirituality of the body and follows in the footsteps of William James(1842-1910), who believes that the spiritual realities contribute more to the happiness of man than scientific realities.

The Hebertist theory of the body recognises, however, that spiritual values cannot be restored without backup of scientific data (LE COUR, 1930).

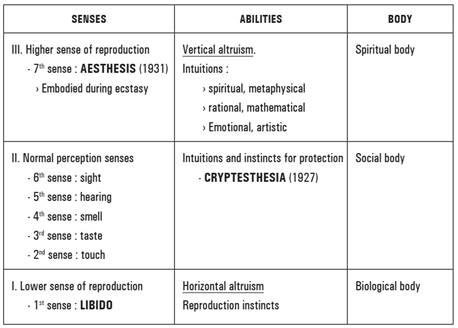

The spirituality of the body of the female athlete of Palestra is underpinned by a theory of sensibility, echoing the works of Charles Richet(1850-1935) who was physiologist, aviation pioneer and winner of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1913. In 1927, Charles Richet publishes the book Our Sixth Sense that studies metapsychic phenomena and in particular the involvement of a higher sense: cryptesthesia which includes the sense of direction, the sense of obstacles, autoscopy, rhabdomancy, dowsing, psychometry, lucidity, clairvoyance, telepathy, monition and premonition. Charles Richet’s approach is rational and fits into the field of parapsychology. The Hebertist approach is based on the works of mystical philosophy of the Hebertist Paul Le Cour (1871-1954) (PHILIPPE-MEDEN, 2014), and tends to join the world of the senses and the immaterial world. According to Le Cour, Hebertist spirituality revolves around the notion of aesthesis, which refers to the ability to perceive with all senses and the ability to create. (LE COUR, 1931, pp. 29-30)

The difference between aesthesis and cryptesthesia is that aesthesis is a global, central sense, using all the others (see Table 1).

Note: The table needs to be read from bottom to top

TABLE 1 Scale of the senses according to the Hebertist sensitivity theory

Let us revisit the Hebertist relationship with “the other” based on this theory of the sensitive body. We know that Georges Hébert oriented his work towards a dominant moral idea, altruism: “to be strong, to be useful [for others]”! This altruism in Hebertism is usually considered along a horizontal axis, towards another fellow being and in this sense Hebertist’s physical education creates altruism incentivised by evolutionary biology or social responsibility. But altruism can also be understood along a vertical axis, towards something greater than oneself (God, nature, homeland, etc.), in which case physical education creates spiritual altruism. Libido and aesthesis are the two reproductive senses on the opposite ends of the scale. The table above shows how starting from the libido, instinctive energies are mobilised to reach aesthesis, which is the centre of intuitive energies. This process transforms the lower energies to subtle energies.

The pursuit of the ideal body of the athlete of the Palestra has nothing to do with the pursuit of beauty because of a sensual, erotic or sexual drive. If sexuality is the only driving force of our behaviour, it may lead to selfish actions and violence. Sexuality allows creating life involving a human being to seek satisfaction by procreation without feeling concerned about potential pain caused. However, a human being can also mobilise aesthesis, either through aesthetics or eroticism, and seek something of a higher order! Ethologists have demonstrated such behaviour by birds during courtship: melodious songs, dances and elegant plumage. In the case of human beings, the difference between eroticism and sexuality is what gastronomy adds to food: an extra, seemingly futile quality but that characterises the high forms of beauty. Consequently, erotic pleasure that is transcended by faith to a state of spiritual voluptuousness is expressed by empathy for the pain of fellow beings and the joy of sacrifice for a greater cause.

Through a transmutation from aesthesis, the elements of physical life are transformed into elements of spiritual life. The psychology of the great Christian mystics is an example of this. (BINET, 1902) According to Jean-Marie Guyau (1854-1888), the mystic compensates “the insufficiency and emptiness of a positive and limited religion” by the superabundance of sentiment:

Mystics substituting a more or less personal sentiment and spontaneous outburst of emotion for a faith in authority, have always played the role in history of unconscious heretics. […] Nothing sentimental or meditative at the origin of religion, there was a stampede simply of a multitude of souls in mortal terror or hope, and no such thing as independence of thought; it is less of sentiment properly so-called, than of sensation and action. (GUYAU, 1887, 19).

The transmutation of physical pain at a spiritual level consists of « a transformation of the human being making him embrace joy and pain, and find more generosity, and more love. » (LE COUR, 1952, p. 129)

At the level of the spiritual body, aesthesis or the “embodied spirit” during ecstasy not only allows sensory, sentimental and intellectual perception, but also metaphysical knowledge or knowledge of vital phenomena. In the mental state of an ecstatic experience whereby the soul is absorbed in beauty, sensations of joy and pain fuse into one single sensation. The person in ecstasy experiences an expanded affective and spiritual awareness, and comes out transformed: “[o]ne would have found in certain mystics special phenomena such as levitation of the body, the incorruptibility of the body after death, the divine smell (odour of sanctity), etc. To enable this process, the theory on the Hebertist body insists on the necessity of a certain chastity which “fills the arteries with blood” and “inflates the soul with power”: “we know that sports champions must follow this strictly while training. (Id., 42)

*************

A survey of previous research done on the Palestra, makes it clear that it is not easy to define the Palestra. Was it a centre for outdoor training for young girls, a rustic village, a sports centre, a holiday resort, a school for physical education (mental, moral, esthetical, natural), an instrument of social emancipation for women through physical activity or rather the opposite, a symbol of their alienation? Apart from issues such as lacking primary sources and access to sources, it is perhaps time to conduct new research away from Georges Hébert and towards female Hebertists such as Yvonne Hébert or Suzanne Grinberg, starting with a study on their works, physical practice (techniques, perceptions, interests), and their articles. It will become clear then, that contrary to common belief, the Palestra was not a phallocratic institution preparing young and pretty girls for dependency on men but instead, providing them with an education experience that was really innovative for the inter-war period. From a practical and ideological perspective, this method that consisted of education, leisure activities and natural lifestyle was a real factor of female emancipation. It was, therefore, not surprising that the Hebertist Palestra was endorsed by feminists. If one looks at the community life at the Palestra, the rustic lifestyle, the daily chores and the education method that combined training in physical, mental, moral and spiritual capacities, one could conclude that the Palestra could be compared to a Hindu ashram. The barren aesthetics model that is similar to Jerzy Grotowski’s concept of “poor” (GROTOWSKI, 2002) or the frugality of mystics implies a style of life leading to a fundamental transformation of the person. In the end, and despite the sports infrastructure on its grounds, the Palestra is an institution of moral development that is diametrically opposed to the sports entertainment society. The women at the Palestra learn to see their bodies as the temple of mind and soul, while also receiving physical education training that will give them access to professional career opportunities in schools and gain independence.