Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.35 Belo Horizonte jan./dez 2019 Epub 21-Ago-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698217636

DOSSIER EDUCATION, HEALTH AND RECREATION

ARTICLE - FROM THE GYMNASTICS CENTRAL INSTITUTE (GCI) IN STOCKHOLM TO BRAZIL: CULTIVATION AND SPREADING OF AN EDUCATION OF THE BODY1

IFederal University of Minas Gerais, School of Education, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

IIFederal University of Viçosa, Viçosa, MG, Brazil.

This paper presents the results of a research on the Stockholm Gymnastics Central Institute and how the Swedish Gymnastics method was disseminated and cultivated. It shows how the GCI, with its training policies and strategies of action, collaborated to disseminate gymnastics in several countries. It focuses on Brazil, mainly on the different ways by which the method gained visibility: in the pedagogical thinking, in school textbooks and in the presence of Fritjof Detthow, a professor who graduated from the Institute in São Paulo. The study shows that the lingian gymnastics that arrived in Brazil must be taken as a cultural object, as a practice that does not remain pure and that, in its circulation, carries a transformative dimension. The gymnastics that Detthow brought to Brazil has deep relations with the one learned in the Institute, although it became different when in contact with a new cultural and political scenario.

Keywords: Gymnastics; Body education; Swedish method

O artigo traz os resultados de pesquisa onde se estudou o Instituto Central de Ginástica de Estocolmo e como foi se constituindo lugar de cultivo e de divulgação do método sueco de ginástica. Mostra como o GCI, com suas políticas de formação e estratégias de ação, colaborou para o espraiamento da ginástica em diversos países. No Brasil, foca nos diversos modos em que o método ganha visibilidade: no pensamento pedagógico, nos manuais escolares e na presença de Fritjof Detthow, professor formado no Instituto, em São Paulo. O estudo mostra que a ginástica lingiana que chega ao Brasil precisa ser tomada como objeto cultural, como uma prática que não permanece pura e que, em sua circulação, carrega uma dimensão transformativa. A ginástica que Detthow traz ao Brasil guarda profundas relações com aquela aprendida no Instituto, ao mesmo tempo que, no contato com um novo caldo cultural e político, se transforma.

Palavras-chave: Ginástica; Educação do corpo; Método sueco

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of the text is to understand the place of the Central Gymnastics Institute of Stockholm (GCI)4 in the cultivation and dissemination of a gymnastics method - the Swedish gymnastics or the gymnastics of Ling.5 It also intends to show, from the Institute, how it travels to Brazil and how, in the Brazilian land, it begins its appearance and transformation.

Understanding the construction, transformation, and circulation of Ling’s gymnastics through an institution, GCI, fits into a historiographical perspective that changes the gaze towards the object, observing it “from within.” Inspired by Revel (1998), we could say, “adjusting the analysis scale”. The zoom is activated to look for the singular trajectory, attempting to perceive, in the gymnastic methods, the subjects and the peculiarities that marked its construction and transformation. Leaving a position of looking “from above”, to a position that allows us to look “inside”. Revel (1998) states that choosing a scale of observation, varying the objective, does not only mean increasing or decreasing the size of the object, but modifying its shape and its pattern. In Brazil, the microanalytical approach in Brazilian studies has been a relatively recent investment in the historiography of Physical Education, for only about two decades. Even more so if we think about the subject of gymnastics and its history.

According to Melo (1999), we can observe different phases through which passed the storytelling of Physical Education in Brazil. The first phases are characterized by the absence of specific object outlines, being linked to broad political periodizations and inscribed in distant time marks, by restriction in the use of sources, by the concern in collecting dates, names and facts and based on the experience of large exponents. Historians as Fernando de Azevedo (1920), Inezil Penna Marinho (1958) and Jair Jordão Ramos (1982), are the main names of these first phases.

With regard to gymnastics, they were concerned with the presentation of European systems, aiming at defining which one would be considered more appropriate to Brazil. They addressed it from the generalization of methods, without concern for the different subjects and the singularities that marked the history of gymnastics in different places, including Brazil.6 In general, they were for the practice of Swedish gymnastics in schools, considering its educational value. It is what we can tell, for instance, in the passage by Fernando de Azevedo:

Among all schools, which aim to attain the goal of all school-based physical education, surely none of them surpasses Ling’s method of observing the physiological laws, in the scientific trap of the entire system, and in immediate results. [...] This method, undoubtedly the best from the pedagogical point of view, is called to supply in the education system a serious gap which, before the nineteenth century, were left open by governments and individuals [...]. (AZEVEDO, 1920, p. 149-150)

It is true that, with time, “telling” in Physical Education has been refining and mobilizing methodologies from the field of history. Non-linear and tantalizing movement, where it is possible to notice advances regarding the historiographic aspects, but still signalize problems of methodological sort, like the exemption of facts, dates and names in opposition to the centrality that these aspects presented in previous periods.7

It is important to highlight the works of Carmem Lúcia Soares (1990) and Silvana Vilodre Goellner (1992), which advance the narrative of and about Physical Education, and especially of gymnastics, by plotting it from problems well outlined in the past, by mobilizing documentary sources and talking with the theoretical framework of the field of History.

After two decades from the writings of Melo (1999), we notice a reconfiguration of the historiographic field. Taborda de Oliveira (2007) indicates that if on one hand this movement of historiographical renewal of Physical Education presented significant advances in both qualitative and quantitative aspects, on the other hand it is necessary that this renewal be continually attentive and reflexive to the chosen themes, object outlinings, definitions of problems, use of sources and theoretical dialogues.

It can be observed that the dialogue with the so-called Cultural History that has flourished so much in the field of History, in a broad way and in the History of Education, more specifically, has also impacted the studies on the History of Physical Education. The research works that study gymnastics begin to consider it as a cultural object, and, from the methodological point of view, to operate with a temporal cut internally defined to the problem / object, prioritizing the subjects and their practices, not disregarding dates, names and facts and inserting them organically in the study proposal. We can cite the studies of Góis Junior (2013; 2015); Melo and Peres (2014, 2016); Puchta (2015); Soares (2000, 2015), Gleyse, Dalben and Soares (2013); Quitzau (2016); Quitzau and Soares (2016); Jubé (2017); Moreno (2001, 2015); Soares and Moreno (2015); Romão and Moreno (2018); Baía, Bonifácio and Moreno (2017); and Avelar (2018).8

These studies, when choosing trajectories of subjects, of institutions, when choosing certain books, manuals, newspapers or magazines - not only as source, but also as research objects - reveal the movement of “objective lens adjustment”, giving a more sophisticated look at those targets, making the look more “inside” and less “over”.9

When we look for research about gymnastics, beyond the frontiers of Brazil, this movement is also felt in different countries. We can cite, in Portugal, Carvalho and Correia (2015); in France, Sarremejane (2006), Andrieu (1988, 1999), Bui-xuân and Gleyse (2001); in Sweden, Ljunggren (2011), Lundvall (2015); in Argentina, Scharagrodsky (2011); and in Uruguay, Giménez (2011), among others.10 In the set of efforts undertaken by the international academic community, these researches carry out a movement of thinking about gymnastics, connecting micro and macro, so as to perceive it as an element of a body education required in different places, by different subjects and with different motivations. As we said, new frames are possible starting from the focus adjustment.

In the research carried out by the Group of Study and Research in History of Gymnastics (GEPHGI),11 of which this paper’s authors are members, we have made the effort of “closing the objective lens” to study gymnastics, electing subjects, manuals and institutions, which had a unique role in building this practice in different countries. We can cite the studies of Moreno (2016), Baia (2018), Romão (2018), Martini (2018), Cabral (2017), Avelar (2018), Bonifácio (2018), Faria (2016) and Santana (2017).

It is in this collective research movement that it was possible to construct the hypothesis, already announced in other works,12 that the GCI becomes the epicenter of Ling’s gymnastics in the world, disseminating the method and making it travel beyond the Swedish frontiers. Therefore, to study this institution, which took care so well of the “sacred” legacy of its precursor, who should be defended of any threat, building, for years, actions in this direction, seemed to us indispensable.13 To trace and understand the Institute as a place of cultivation of the body education, as a place of protection and preservation of the Ling method, as a place of dissemination of this practice in the world, and particularly in Brazil, proved to be a powerful research route.

THE CENTRAL INSTITUTE OF GYMNASTICS: A REFERENCE PLACE FOR TEACHER EDUCATION

An important character in the creation of the Central Institute of Gymnastics, in Stockholm, was Pehr Henrik Ling.14 Born on November 15, 1776, in Sweden, he had his work with gymnastics marked by his passage through Denmark where he lived for five years.15 In Copenhagen, he attended classes with Nachtegall (1777-1847), who would later mark his return to Sweden and his dedication to gymnastics until 1839, the year of his death.16 Nachtegall had already begun training gymnastics teachers for the army and for schools (PEREIRA, s / d). Ling, inspired by the work of the Danish, planned to open in Stockholm a gym teacher training school for the whole Sweden.

In 1813 Ling settled in Stockholm to act as fencing teacher at the Military Academy in Karlberg, northern region of Stockholm.17 Parallel to this work, the Swedish instructor proposes to the Education Commission of the government a project of physical training for young people, through gymnastics. With the formal support of Esaias Tegnér of the University of Lund,18 the State approved Ling’s proposal, so he began to seek the necessary conditions for the creation of the Central Gymnastics Institute of Stockholm.19

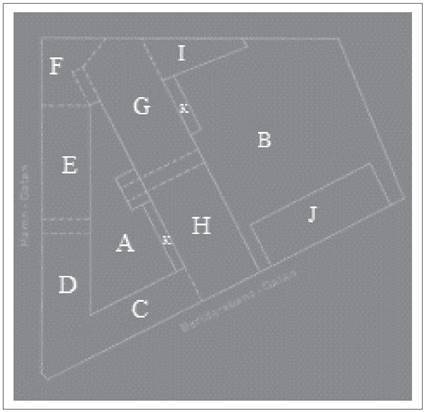

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Gymnastiska_Centralinstitutet

IMAGE 1 Stockholm Gymnastics Central Institute, in 1900

The Institute was inaugurated in 1814, initially occupying rooms adapted from old buildings that had housed a cannon foundry. It remained in this space all his trajectory, receiving subsidies from the royal government over the years, which made it possible to expand the spaces and its activities.20 It was built in the central area of the city.21 Its denomination, Central, referred to the function of centralizing the education of the gym teacher in the whole country, and in the period when it was called Royal, it also marked the state character of the institute. It is worth to remember that to become a gym teacher in public schools in Sweden, it was mandatory to have been trained at the Institute. The same was true to act as a gymnast doctor: the license granted by the Health Council depended on studies accomplished at the GCI22 (POSSE, 1891).

In the open air, the Institute’s structure contained a paved triangular court (section A) and a gravel patio at the back (section B). Sections C and D had three floors of construction, housed the director’s house, some teachers and staff, and downstairs, the dressing rooms. Section E was intended for medical gymnastics, having a second floor occupied by a library, a reading room, two classrooms, a room for student use, and a room for the storage of anatomy collections. Section F housed the men’s dressing rooms. Sections G and H, built on two floors, had ample space for school gymnastics and fencing in the lower part. The upper part had two rooms for medical gymnastics (activity for those who paid for the treatment), school gymnasium space and classrooms. Section I was intended for practical anatomy exercises. Opposite to it, section J, which was intended for gymnastics apparatus. The sections referring to the letter K were destined for keeping the belongings of people who attended the Institute (LEONARD, 1923).

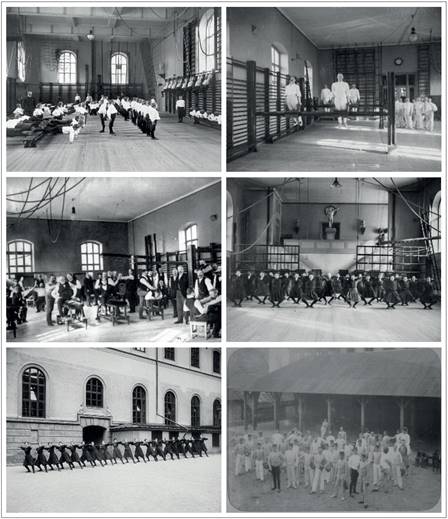

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Gymnastiska_Centralinstitutet

IMAGE 3 Gymnastics space at the Stockholm GymnasticsCentral Institute, in 1900

The organization of the Institute was carried out by a council composed of a director and three other members, one of whom should be a military officer, another one, a teacher, and a doctor23 (LEONARD, 1923). This composition is related to Ling’s belief that gymnastics should have a place in education, in medicine (prevention and healing) and in the national defense. Ling was the first director, remaining in the position from 1813 to 1839, moment of his death (HOLMSTRÖM, 1949). Other directors have been indicated in the sequence and almost always, occupied the position for a long time.

TABLE 1 Directors at the Gymnastics Central Institute in the first century

| Directors | Education/function | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Pehr Henrik Ling | Professor | 1813-1839 |

| Lars Gabriel Branting | Physician | 1839-1862 |

| Gustav Nyblaeus | Colonel | 1862-1887 |

| Lars Mauritz Torngren | Captain | 1887-1907 |

| Viktor Gustav Balck | Colonel | 1907-1909 |

| Nils Fredrik Sellén | Major | 1909-1924 |

Source: Holmström (1949).

Ling acted alone until 1818, when he received Gabriel Branting, a physician, to act as the institution’s second teacher. Branting had studied at Sweden’s largest Medical School at the time, the Karolinska Mediko-Kirurgiska Institut. He had been Ling’s student at the Institute in his first year of service, being his assistant at the Karlberg Military Academy. Throughout his career, he dedicated himself to improving the medical fundamentals of gymnastics.25 Ling put a great deal of confidence in Branting, gradually transferring responsibility for theoretical and practical instruction, making him a central figure in the continuation of the work of the idealizer (LEONARD, 1923; PEREIRA, S/d).

In 1829, Carl August Georgii began his trajectory as a teacher at the Institute. Like Branting, Georgii was very respected by Ling and was one of those responsible for continuing his work. One of his main contributions was the finalization and publication of the main work of Ling, Gymnastikens allmänna grunder,26 in partnership with P. J. Liedbeck27 (PEREIRA, S/d, 309-310; HAGELIN, 1995).

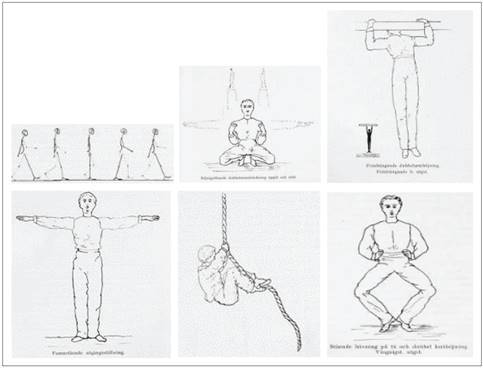

Hjalmar Fredrik Ling, son of P. H Ling, who had studied at the Institute, started in 1843 his performance as a teacher and responsible for the development of the educational gymnastics. His work made possible the adaptation of Ling’s gymnastics in Swedish schools. Inspired by his father’s work, Hjalmar created new sorts of apparatus adapted to the needs of the school and expanded the possibilities of exercises, allowing a large number of students to exercise at the same time. He also systematized the most appropriate exercises in groups - according to specificities and the progression. This achievement was fundamental for the organization of lessons for girls and boys of school age, of different ages and with distinct degrees of abilities (LEONARD, 1923; PEREIRA, S / d). Thus, he earnestly devoted himself to the subject of educational gymnastics. He is the author of the several drawings of educational gymnastics forms and movements - a collection of figures according to the exercise effect in the organism, in different classes, as were his father’s plans.

Branting, Georgii and Hjalmar not only reproduced knowledge and practices, but worked on their method’s updating. Lindroth (1979) states that the followers’ task was not easy - Ling left no writings on gymnastics to assist in the continuation of his work. For the author, the strong philosophical mark in Gymanastikens allmanna grunder, makes it not very clear.28 So, much of what is attributed to Ling has the mediation, mark of the experiences, which Branting and Georgii established with the precursor, a result of decades working together in the same institution.29

TABLE 2: First succeeding educators at GCI

| Name | Educational Gymn. | Medical Gymn. | Military Gymn. |

| Lars Gabriel Branting | Worked from 1818 to 1881. | ||

| Carl August Georgii30 | Worked from 1829 to 1849. | Worked from 1829 to 1849. | Worked from 1829 to 1849. |

| Hjalmar Fredrik Ling | Worked from 1843 to 1882. | ||

| Lars Mauritz Torngren | Worked from 1882 to 1907. | ||

| Gustav Nyblaeus | Worked from 1838 to 1887. | ||

| Viktor Gustav Balck | Worked from 1887 to 1909. | ||

| Carl Silow | Worked from 1883 to 1909. (second teacher) | ||

| Truls Johan Hartelius | Worked from 1852 to 1887. |

Source: Adapted from Pereira (S/d) and Leonard (1923).

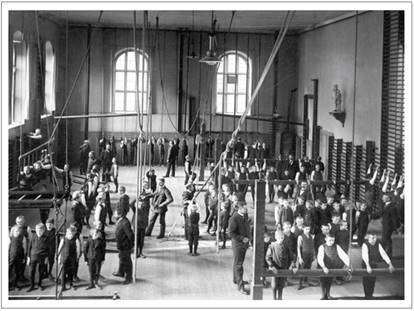

In 1900 and 1901, the Institute’s training faculty included a principal teacher and a second teacher in each of the three departments; two women teachers, one in Hygiene and another one in medical-gymnastics; extra teachers, men and women, making a total of fifteen people.31 These teachers were responsible for offering three courses for the masculine gender, to form army instructors, gymnastics teachers and gymnast-physicians. For the women, there was only one course with the duration of two years.32 The Institute was functioning all day long, with teacher training and the presence of school pupils and patients who needed medical gymnastics. Around 500 children attended GCI daily. Classes for this audience served as training for students in training. In each room, students were subdivided in small groups, under the supervision of GCI students. For several authors, this was one of the qualities of the Institute’s work: the possibility of experiencing with real practice the gymnastics teaching (LEONARD, 1923; POSSE, 1891).

Source: https://www.gih.se/Bibliotek/Om-biblioteket/Foton-ur-arkivet/Barngymnastik/Barngymnastik-1/

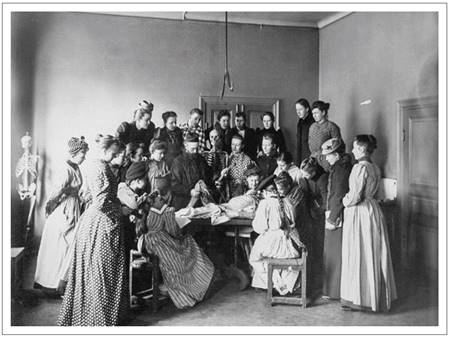

IMAGE 5 Likely class with students of Klara elementary school, in the GCI, in 1893

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Gymnastiska_Centralinstitutet#/media/File:Lektion _i_anatomi_vid_Gymnastiska_Centralinstitutet_Stockholm_kvinnliga_kursen_1891-1893_gih0124.jpg

IMAGE 6 Anatomy class with women students at the GCI (1891-1893)

During the first year, no matter the course, students had common classes of (1) anatomy; (2) physiology of the circulation and of the organs of nutrition and respiration; (3) educational gymnastics theory, including positions, movements, commands, lessons and progressions; (4) military gymnastics and (5) fencing theory. Besides the theoretical classes, since the first year of the course, there was practical instruction of educational gymnastics and fencing (PEREIRA, S / d; LEONARD, 1923; POSSE, 1891).

In the second year, the students, besides the theoretical subjects mentioned (now broader and deeper), still had (1) kinesiology and (2) theory of medical gymnastics. In the third year, the students had the opportunity to assist in the treatment of the large number of patients who visited the Institute (PEREIRA, S/d, LEONARD, 1923, POSSE, 1891).

Once trained, teachers were still under the supervision of the Institute. All the Swedish gymnastics taught in schools was carefully controlled by the GCI. According to Posse (1891), one of the GCI director’s duties was to supervise the instruction of gymnastics all over the country, traveling from city to city. Teachers could be removed from schools if they were considered unfit for teaching the method. For the author, this supervision ensured the excellence in teaching gymnastics and the uniformity of the method.33

This is how the Institute kept slowly, along the years, through extensive assertive actions, getting more organized and stronger. It had its physical space structured so as to put into practice the proposal to make gymnastics a transversal subject for all children and young people in Sweden. Moreover, it was offered as the place of reference for the body education proposal for the Swedish people. Believing in the training of gymnastics teachers was one of the fundamental strategies to succeed in such an undertaking, which included investment in courses, specialization and theoretical-practical training.

FROM STOCKHOLM: SWEDISH GYMNASTICS DIFFUSION STRATEGIES

As we have seen, the GCI played a fundamental role in the process of circulating Ling’s ideas and gradually became the radiating center of the method. In Sweden the institute made the method expand and then made it “travel” in different ways, and at different times, throughout the world. On this journey, rational gymnastics went through some changes over time, but always under strict observation of its principles.

The Institute became, as already said, the epicenter of Swedish gymnastics in the world. It took the responsibility for the study, the continuation and the dissemination of Ling’s method. A strong missionary trait marked the partisans of Swedish gymnastics, who traveled abroad to spread it, and propagate the precursor’s sacred ideas (LJUNGGREN, 2011; MORENO, 2015). Among the actions that contributed the most to its dissemination, was, undoubtedly, its “exchange” policy. In 1913 it had 142 foreigners (GRUT, 1913).34 The Institute sent representatives to other countries and received missions from scholars and foreign researchers who went there and returned to their countries, publishing reports and treatises that served as reference throughout the world. We should point out here the works of Demeny (1901) and Lefebure (1903, 1905).

Accessing the gymnastics yearbooks of the GCI, it is possible to notice how the record of the diffusion of lingian gymnastics around the world was a concern. The United States, France, England, Portugal, Belgium, Japan, India, and many countries of South America at different times, had received teachers trained at the Institute, or else, sent missions there to take courses.35

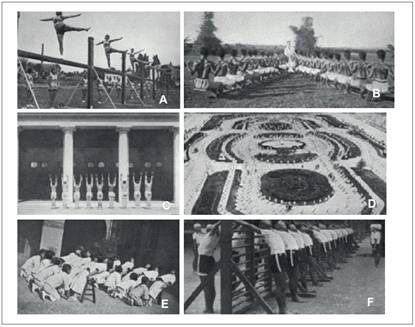

Source: https:Riksföreningens för Gymnastikens Främjande Arsbok, 1934

IMAGE 7 Swedish Gymnastics around the world - A: Romania, B: Dutch India,C: Greece, D: Brazil, E: China, F: Japan

We could also highlight the Institute’s efforts to be present in the international spaces of exchange of experiences in the “contact zones” (PRATT, 1999). The International Congress of Physical Education of Paris in 190036 and 191337 are examples.

VESTIGES OF SWEDISH GYMNASTICS IN BRAZIL

In Brazil, the practice of gymnastics, particularly the Swedish, already occupied the discourses in theses and medical treatises, which emphasized the “new method” as efficient and adequate. This fact is clear in the opinion of Dr. Rego Cesar on the book by Schenström (1876), in the Brazilian Annals of Medicine (1876)38 and also in the works of intellectuals and politicians, such as Rui Barbosa’s famous opinion of 188339 in which he highlights the example of Sweden, regarding school and military gymnastics.

However, it did not immediately become a theme or gained space to be read / seen also by people who did not attend political and academic events, but obviously literate and had access to newspapers.

In Brazil, on July 24, 1892, an extensive, full-page report, published in Jornal do Commercio, a newspaper from Rio de Janeiro, and three months later republished in the newspaper A ordem (10/22/1892), in Minas Gerais, calls the attention to the gymnastics method which, created in Sweden, achieved unthinkable results in that country. The article describes, in detail and in accessible language, the characteristics of Swedish gymnastics, its conception by Ling, the creation of the Stockholm Gymnastics Institute and its operation. Throughout the text, the writer tries to show how Swedish gymnastics is appropriate, because of its harmonious characteristics, its democratic character, its simplicity, for not presenting much acrobatics, for being natural and requiring little effort, for giving emphasis on breathing and being hygienic. Also, because it requires amplitude of movements, having a slow and progressive action, for being a gymnastics of attitudes, and strongly inspired by a feeling of aesthetics and harmony. Furthermore, it would also be more appropriate for women. The article is a defense and an invitation for the adoption of Ling’s rational gymnastics.40

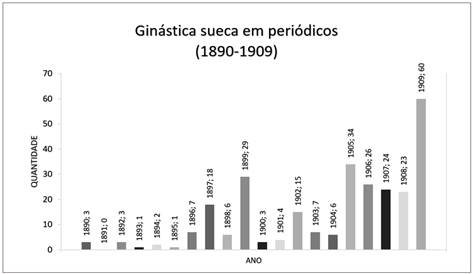

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the Swedish gymnastics slowly begins to occupy the pages of newspapers and magazines, as we can see in the following graph:41

Source: Brazilian Digital Journal Library (Biblioteca Nacional)

GRAPH 1 Number of Swedish Gymnastics publications in journals per year

Besides quantity, which increases significantly, there is another aspect to be emphasized, which is the issue of language. We can take the newspapers, as a symptomatic place where, in a two-way street, proclaim in their pages what the theme of culture is, however, at the same time, they produce this culture. If we take language (understood as the incorporation of terms and expressions) as one of the “symptoms” that some phenomenon is being incorporated in the culture of a time and a place, it is worth to pay attention, for example, at how the expression “Swedish gymnastics” or simply “the Swedish” is being incorporated into everyday language and not only in the specialized one. The expression leaks from “competent discourse”, and reaches newspapers intended for children, sections aimed at the female audience, chronicles and short stories. Whether to refer to a bodily practice, or to be used as a synonym of discipline, the word/expression is passed forward as if it were common and everyone understood it.42

Therefore, to imagine how it was possible for the Swedish gymnastics to gain such visibility in the Brazilian newspapers, is somehow to think about the routes traveled by this practice, all the way from Stockholm, to finally arrive in Brazil.

Our research shows that the Swedish gymnastics gained visibility here, especially in three forms: (1) in the discourse of intellectuals in defense of the method,43 (2) in the popularization of this knowledge through the gymnastics manuals and (3) in the circulation of subjects. Of these three forms, rational gymnastics brought changes in matrix thinking - therefore, understanding the forms of its dissemination, its transformations and permanence is important.

About writing manuals, we know that there was a powerful process of producing materials that vulgarized the knowledge about Swedish gymnastics. A rich set of printed material, with characteristics of manuals, was produced in the Portuguese language. The effort of teachers, but also of military and doctors, was remarkable, to write and disseminate Swedish gymnastics, in an effort to systematize and apply its practice. The idea was that teachers needed Portuguese language material to help them.

The manuals presentation was quite inviting. A simple, small, objective printed text, arranged in lessons easy to apply, with a shallow theoretical foundation and a systematization of practical lessons, containing many drawings that facilitated their understanding. The didactic manuals played an important role of circulation and appropriation of knowledge about gymnastics, since it was necessary to simplify it, considering the excess of details in its execution and the details for its practice.44

In Brazil, although historiography paid little attention to the subjects who came to our lands from Stockholm, and the role they played in the dissemination of this practice, they certainly came, and here they accomplished their task, going to different places, an important strategy for its diffusion. Perhaps, a little later than in other countries, since this movement occurred with more intensity after the twenties, in the twentieth century.

Although there is no mechanical relation between the displacement of these subjects and the increase of Swedish gymnastics in the world, nor in Brazil, to pay attention to the subjects, to follow their trajectories, is, in some way, to close the objective lens, embodying the story. As reminds Ângela de Castro Gomes (1993), the ideas in circulation, “do not walk alone in the streets”, they are mediated by an agent. Even though the circulation of knowledge, in this case of gymnastics, has gone through different and unusual ways which, as we have seen, go through the translation of materials, publication of manuals, spaces of meetings and contacts, subjects that mediated the transit of this knowledge.

This is the case, for example, of Fritjof Detthow and other subjects that disembarked in Brazilian lands. In 1919, newspapers announced the receipt of a telegram45 on the coming of a delegation of Swedish teachers to teach in São Paulo. There are also announcements46 that show that in these lands there were teachers, since the first decades of the twentieth century, trained at the Institute and working with Swedish gymnastics. Mme. Will, Mme. Ester Leo, Sven Kellander, Artur Linderdahl, Mme. Maria Grushka are some of the names that appear in the sources.

Fritjof Detthow was born in 1886, in the town of Ulricehamm, Sweden. He becomes a military man and works in the Swedish army until 1918, when he retires with the rank of captain. Having studied and graduated at the GCI from 1913 to 1917, Fritjof comes to Brazil in 1919, hired by the State of São Paulo “to implement Swedish gymnastics in schools”.47

In the city of São Paulo he settled with his wife and two children and began working for the General Directory of Public Instruction (later General Directory of Education), as technical assistant of Physical Education,48 receiving salaries from the Interior Office of the State of São Paulo.49 His relationship with the Board of Directors involves him in several actions: surveys of São Paulo schools in 1931,50 courses to the São Paulo professorship on the Swedish gymnastics and gymnastics theory throughout the 1920s and 1930s, involvement with the III National Conference on Education in 1929, enthusiasm in the organization of the I Brazilian Congress of Physical Education, among other important actions. Over time, this relationship will allow Detthow to establish contacts with important institutions, like the Department of Physical Education of the State of São Paulo,51 with the School of Physical Education52 and also with important educators. There is evidence of a solid social network attended by him, notably of people in the educational field of São Paulo. In school education, the Swedish professor will work in places of great visibility: in the Caetano de Campos Normal School, where he is a teacher and where there are many records of his actions.53

In several interviews he gives to the newspapers, Detthow highlights the experience that Sweden had in the implementation of gymnastics and physical education, the importance of the GCI in these actions and in the training of teachers. His presence and bond with the educational field generate important changes in the schools of São Paulo in what concerns the teaching of gymnastics, based on the Swedish system: adoption of individual records, classes organized by aptitude, ability and organic condition.54

Source: Correio de São Paulo, nº 165, December 23, 1932

IMAGE 8 Frijtof announces its project of Physical Education in the schools of São Paulo

Concomitantly with his work with the State, the Swedish teacher gives private Swedish gymnastics classes. The several announcements published in São Paulo newspapers, beginning in 1921, and testimonies, show that the teacher had assembled a room with equipment of the Swedish gymnastics system.55 There are also ads of private teachers “trained by Frijtof Detthow”.56 There are reports that he has performed at various festivities of the Scandinavian Society and other charity institutions, rehearsing dances and numbers of Swedish gymnastics.57 In the late 1920s, he acquired the Jaguaribe Institute, an important institution that served the São Paulo elite, offering, among other activities, Swedish medical gymnastics.58

During this time, Fritjof will also write, not only in newspapers, but also in journals of the educational field, in Brazil and abroad: in the Education Magazine (Organ of the Committee of the General Directory of Teaching of São Paulo),59 Revista Escuela Moderna (Spain)60 and in Monitor magazine (Argentina)61 there are articles by the Swedish professor. There is also the record of articles in magazines of the cultural area like the Vanitas,62 mundane and illustrated magazine, that indicates articles of Detthow.

The compilation of sources carried out so far indicates that Fritjof Detthow enjoyed an important recognition in São Paulo and developed a quite vigorous job of dissemination and insertion of the Swedish gymnastics. It is noteworthy that throughout this time there are records of travels he made to the lands of Ling to be updated and have news of the advance of rational gymnastics so as to share them in Brazil. These trips, registered in newspapers, had the support of the government of São Paulo, which included commissioning the teacher for the trips.63

Detthow also worked in scouting,64 was a translator (he even published Madame Dupret’s novel, We Were Six, in Swedish)65 and he also became involved with scientific excavation teams, mainly during the late 1930s through the 1940s. During that time, he never lost the bond with the Swedish government, representing it in festivities, awards and official acts.66

Fritjof Detthow lived a period of many transformations in Brazil, in a broad way, and in São Paulo, particularly. They were turbulent times that involved changes in both political terrain (local upheavals, revolts and involvement with the Second War), cultural changes (changes in habits and customs) and in the educational field (emphasis on the 1920s67 education reform). The teacher also went through a period of many transformations of the Swedish system itself, which was also in the process of modernization, trying less rigid new techniques and also sports.

CONCLUSION

The research made it possible to realize the intense and extensive work that the Stockholm Institute of Gymnastics executed for the education of bodies. Over time, the precursors of Swedish gymnastics have made large investments aiming at structuring a place, method and teacher training that could be a reference for the physical care of the body. Such care also slipped into morality and manners, after all, to educate the body through gymnastics was to educate the will as well.

Certain that they had found “the” effective method for educating, cultivating and preserving the body in good health, the Institute also established itself as a resonating place for Swedish gymnastics. It was necessary to spread the news to the world: to make gymnastics possible to be practiced by everyone, in many different places.

We have seen that the lingian gymnastics that arrives and circulates in Brazil (but also in other parts of the world), must be considered as a cultural object, as a practice that is not born or remains pure and that, in its circulation, through mediators, carries a transformative dimension (GRUZINSKI, 2001). Thus, the Swedish gymnastics that Fritjof Detthow brings to Brazil and tries to diffuse and implement, maintains deep relations and permanences with the one learned in the Institute, while, in contact with a new cultural and political scenario, it is transformed. The new place, now experienced by the Swedish teacher, certainly impacted his ideas on body and gymnastics education.

We believe that the results of this set of researches allow us to shed light on the history of body education, of physical education and the history of education in Brazil. They allow us to perceive the process of internationalization of knowledge and practices, a complex plot that involved the translation, appropriation, transformation, reinvention of European methods in their journeys until arriving in Brazilian lands. In this sense, the empirical material mobilized corroborates the idea, already pointed out by several theories, that in this transit there were, in a two-way street, exchanges, learning, appropriations and reinventions.

REFERENCES

ANDRIEU, G. L’homme et la force. França: Editions Actio, 1988. [ Links ]

ANDRIEU, G. La Gymnastique au XIX Siècle ou a naissance de l’education physique (1789-1914). França: Editions Actio , 1999. [ Links ]

AVELAR, A. C. Uma ginástica que também se lê: a produção do Compendio de Gymnastica Escolar de Arthur Higgins (1896-1934). Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Belo Horizonte: FAE/UFMG, 2018. [ Links ]

AZEVEDO, F. Da Educação Physica: o que ella é - a que tem sido - o que deveria ser. São Paulo: Weiszflog editores, 1920. [ Links ]

BAIA, A. C.; BONIFACIO, I. M. A.; MORENO, A. O tratado pratico de gymnastica de L. C. Kumlien: circulação, transformação e vestígios do método sueco de ginástica na educação dos corpos no Brasil (1895-1955). In: IXCBHE história da educação: global, nacional e regional. João Pessoa, 2017, p. 3757-3770. [ Links ]

BAIA, A. C. Revista Brasileira de Educação Física: a circulação das ideias de Ling e a ginástica Sueca no Brasil (1944-1952). Projeto de Pesquisa (Pós-Doutorado). Belo Horizonte: FAE/UFMG, /MG, 2018. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, R. Reforma do ensino primário e várias instituições complementares da instrução pública. Obras completas. v. X, tomo I ao IV. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Saúde, 1947. [ Links ]

BONIFÁCIO, I. M. A. Circulações da ginástica sueca: um olhar a partir de L. G. Kumlien (1895-1933). Projeto de Pesquisa (Mestrado). Belo Horizonte: FAE/UFMG, 2018. [ Links ]

BUI-XUÂN, G.; GLEYSE, J. De L’emergence de L’education physique: Georges Demeny et Georges Hebert - um modele conatif aplique au passé. Paris, Hatier, 2001. [ Links ]

CABRAL, P. L. C. Fundamentos do método sueco de ginástica: tradução de ideias (1834-1896, Suécia/Brasil). Projeto de Pesquisa (Autônomo). Belo Horizonte/MG, 2017. [ Links ]

CANTARINO FILHO, M. R. A Educação Física no Estado Novo: história e doutrina. 1982. 217 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, 1982. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, L. M; CORREIA, A. C. A recepção da Ginástica Sueca em Portugal nas primeiras décadas do século XX: conformidades e dissensões culturais e políticas. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, v. 37, n. 2, 2015, p. 136-143. [ Links ]

CASTELLANI FILHO, L. Educação Física no Brasil: a história que não se conta. Campinas: Papirus, 1988. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, M. A invenção do cotidiano I: as artes do fazer. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1994. [ Links ]

DEMENY, G. L’Éducation physique en Suéde mission de 1891. 10ª ed. Paris: Société d’Éditions Scientifiques; 1901. [ Links ]

FARIA, R. B. Luiz Furtado Coelho e sua trajetória profissional como professor e divulgador da ginástica sueca em Portugal. Projeto de Pesquisa (Iniciação Científica). Belo Horizonte: FAE/UFMG, 2016. [ Links ]

GEORGII, A. A Biographical Sketch of the Swedish poet and gymnasiarch, Peter Henry Ling. London, 1854. [ Links ]

GHIRALDELLI JUNIOR, P. Educação Física progressista. São Paulo: Loyola, 1988. [ Links ]

GIMÉNEZ, R. R. Una conciencia y un corazón rectos en un cuerpo sano: educación del cuerpo, gimnástica y educación física en la escuela primaria uruguaya de la reforma. In: SCHARAGRODSKY, Pablo. (comp.) La invención del “homo gymnasticus”: Fragmentos históricos sobre la educación de los cuerpos en movimiento en Occidente. Buenos Aires: Prometeo, 2011. p. 477- 496. [ Links ]

GLEYSE, J. ; DALBEN, A. ; SOARES, C. L. . Estudo comparativo da recepção do Método Natural de Georges Hébert no Brasil e na França. In: XIIICongress of the International Society for the History of Physical Educationand Sport and XII Brazilian Congress for the History of Physical Education and Sport. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Gama Filho, v. 1, 2013, p. 107-117. [ Links ]

GOELLNER, S. V. O método francês e a Educação Física: da caserna à escola. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação Física). Porto Alegre: UFRGS, 1992. [ Links ]

GÓIS JUNIOR, E. Ginástica, higiene e eugenia no projeto de nação brasileira: Rio de Janeiro, século XIX e início do século XX. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 19. n. 1, jan/ mar de2013, p.139-159. [ Links ]

GÓIS, JUNIORE. Georges Demeny e Fernando de Azevedo: uma ginástica científica e sem excessos (Brasil, França, 1900-1930). Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, v. 37, 2015, p. 144-150. [ Links ]

GOMES, A. C. Essa gente do Rio... os intelectuais cariocas e o modernismo. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 6, n. 11, 1993, p. 62-77. [ Links ]

GRUT, T. A. The Gymnastic Central Institute at Stockholm. In: International Congress on School Hygiene. Buffalo, 1913. [ Links ]

HAGELIN, O. Rare and Curious Books in the Library of the old Royal Central Institute of Gymnastics. Estocolmo, 1995. [ Links ]

HOLMSTRÖM, A. La Moderna Gimnasia Sueca - desde Ling hasta la Lingiada. Editorial Sohlman, Estocolmo, Suécia, 1949. [ Links ]

HONORATO, T. A Reforma Sampaio Dória: professores, poder e figurações. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 42, n. 4, out./dez.2017, p. 1279-1302. [ Links ]

JUBÉ, C. N. Educação, Educação Física e Natureza na obra de Georges Hébert e sua recepção no Brasil. (1915-1945). Tese (Doutorado em Educação) Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, SP, 2017. [ Links ]

LEFEBURE. L’Éducation physique en Suède. Bruxelles: H. Lamertin Éd; 1903. [ Links ]

LEFEBURE. Méthode de Gymnastique Éducative. Bruxelles: Guyot Frères Éditeurs; 1905. [ Links ]

LEONARD. F. E. A guide to the history of physical education. Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia e New York, 1923. [ Links ]

LINDROTH, J. Linganism and the natural method - the problem of continuity in Swedish gymnastics. In: 8th International Congress for the History of Sport and Physical Education. Uppsala e Estocolmo, 1979. [ Links ]

LING, P. H. Gymnastikens allmänna grunder. Upsala: Palmblad & Comp; 1834-1840. [ Links ]

LJUNGGREN, J. ?Por qué la gimnasia de Ling? El desenrrollo de la gimnasia sueca durante el siglo XIX. In: In: SCHARAGRODSKY, Pablo. (Org.) La invención del “homo gymnasticus”: Fragmentos históricos sobre la educación de los cuerpos en movimiento en Occidente. Buenos Aires: Prometeo , 2011. p. 37-52. [ Links ]

LUNDVALL, S. From Ling Gymnastics to Sport Science: The Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, GIH, from 1813 to 2013. The International Journal of The History of Sport. [s.l.], abr. 2015, p. 789-799. [ Links ]

MARINHO, I. P. Sistemas e Métodos de Educação Física. 2ª ed. São Paulo: Companhia Brasil Editora, 1958. [ Links ]

MARTINI, C. O. P. A ginástica sueca para mulheres: os cursos, as práticas e as possibilidades de formação e atuação profissional. Projeto de Pesquisa (Autônomo). Belo Horizonte/MG, 2018. [ Links ]

MELO, V. A. História da história da Educação Física e do esporte no Brasil: panorama e perspectivas. São Paulo: Ibrasa, 1999. [ Links ]

MELO, V. A.; PERES, F. F. A Gymnastica no tempo do Império. 1ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2014. [ Links ]

MELO, V. A.; PERES, F. F. Relações entre ginástica e saúde no Rio de Janeiro do século XIX: reflexões a partir do caso do Colégio Abílio, 1872-1888. Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos. v. 23, n. 4, 2016, p.1133-1151. [ Links ]

MORENO, A. A propósito de Ling, da ginástica sueca e da circulação de impressos em língua portuguesa. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, v. 37, 2015, p. 128-135. [ Links ]

MORENO, A. Corpo e ginástica num Rio de Janeiro - mosaico de imagens e textos. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2001. [ Links ]

MORENO, A. Ginástica Sueca no Brasil: presença nos manuais escolares e no pensamento pedagógico entre fins do século XIX e início do XX. Projeto de Pesquisa (FAPEMIG). Belo Horizonte: FAE/UFMG, 2016. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, C. F. M. Tratado de Educação Física - Problema Pedagógico e Histórico. - v. I. Lisboa: Bertrand, S/d. [ Links ]

POSSE, N. F. How gymnastics are taught in Sweden: the chief characteristics of the Swedish system of gymnastics - two papers. Boston: T.R. Marvin & Son; 1891(reimpressão). [ Links ]

PRATT, M. L. Os Olhos do Império: relatos de viagem e transculturação. Bauru, EDUSC, 1999. [ Links ]

PUCHTA, D. R. A escolarização dos exercícios físicos e os manuais de ginástica no processo de constituição da Educação Física como disciplina escolar (1882-1926). Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, 2015. [ Links ]

QUITZAU, E. A. ; SOARES, C. L. . Um manual do século XVIII: culto à natureza e educação do corpo em “Ginástica para a Juventude, de Guts Muths Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v. 16, 2016, p. 23-50. [ Links ]

QUITZAU, E. A. Associativismo ginástico e imigração alemã no Sul e Sudeste do Brasil (1858-1938). Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2016. [ Links ]

RAMOS, J. J. Os Exercícios Físicos na História e na Arte: do homem primitivo aos nossos dias. São Paulo: IBRASA, 1982 [ Links ]

REVEL, J. Microanálise e construção do social. In: REVEL, J. (org.). Jogos de escala: a experiência da microanálise. Trad. Dora Rocha. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 1998, p. 15-38. [ Links ]

ROMÃO, A. L. F.; MORENO, A. Das piruetas aos Saltos: As diferentes manifestações da Gymnastica no Rio de Janeiro da Segunda Metade do XIX. Cadernos Cedes(IMPRESSO), v. 38, 2018, p. 21-32. [ Links ]

ROMÃO, A. L. F. Tentativa de criação de um Método de Educação Física com “alma nacional” (Brasil, décadas de 1930 e 1940). Projeto de Pesquisa(Doutorado). Belo Horizonte: FAE/UFMG, 2018. [ Links ]

SANTANA, B. A. Ideias sobre Ginástica Sueca: o que dizem os manuais produzidos no Brasil e em Portugal (1880- 1930). Projeto de Pesquisa (Iniciação Científica). Belo Horizonte: FAE/UFMG, 2017. [ Links ]

SARREMEJANE, P. L’heritage de la méthode suédoise d’education physique em France: les conflits de méthode au sein de l’Ecole normale de gymnastique et d’escrime de Joinville au début du XXème siècle. Revista Paedagogica Historica, v. 42, n. 6, 2006, p. 817-837. [ Links ]

SCHARAGRODSKY, P. La constitución de la educación física escolar en la Argentina. Tensiones, conflictos y disputas con la matriz militar en las primeras décadas del siglo XX. In: SCHARAGRODSKY, Pablo. (comp.) La invención del “homo gymnasticus”: Fragmentos históricos sobre la educación de los cuerpos en movimiento en Occidente. Buenos Aires: Prometeo, 2011. p. 441-475. [ Links ]

SCHENSTRÖM, R. Gymnastique Médicale Suédoise. Paris, Librairie K. Nilsson, 1876. [ Links ]

SOARES, C. L.. Os Sistemas Ginásticos e a Formação da Educação Física Brasileira. In: VIICongresso Brasileiro de História da Educação Física, Esporte, Lazer e Dança. Gramado, v. 1. 2000, p. 44-52. [ Links ]

SOARES, C. L.. Uma educação pela natureza: o método de educação física de Georges Hébert. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, v. 37, 2015, p. 151-157. [ Links ]

SOARES, C. L. O pensamento médico-higienista e a Educação física no Brasil - 1850/1930. Dissertação ( Mestrado em Educação). São Paulo: PUC, 1990. [ Links ]

SOARES, C. L.; MORENO, A. Dossiê - Práticas e prescrições sobre o corpo: a dimensão educativa dos métodos ginásticos europeus. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, v. 37, 2015, p. 108-110. [ Links ]

TABORDA DE OLIVEIRA, M. A. Renovação historiográfica na Educação Física brasileira. In: SOARES, Carmen Lúcia (org.). Pesquisas sobre o corpo: ciências Humanas e Educação. São Paulo: Autores Associados, 2007, p.117-138. [ Links ]

WESTERBLAD, C. A. Ling, the founder of Swedish gymnastics: his life, his work, and his importance. Stockholm: Kungl. Boktryckeriet; 1909. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

A EstaçãoA Estação: Jornal Illustrado para a família (RJ) [ Links ]

A NaçãoA Nação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (SP) [ Links ]

A ordemA ordem (MG) [ Links ]

Anais do CongrèsAnais do Congrès International de L1èducations Physique [ Links ]

AnnaesAnnaes Brasilienses de Medicina [ Links ]

AnuárioAnuário do Ensino do Estado de São Paulo [ Links ]

CidadeCidade do Rio [ Links ]

CorreioCorreio de São Paulo [ Links ]

CorreioCorreio de São Paulo [ Links ]

CorreioCorreio Paulistano [ Links ]

DiárioDiário do Paraná [ Links ]

DiárioDiário Nacional [ Links ]

FolhaFolha da Manhã(SP) [ Links ]

JornalJornal do Commercio (RJ) [ Links ]

JornalJornal do Recife [ Links ]

O CommercioO Commercio de São Paulo [ Links ]

O EstadoO Estado de São Paulo [ Links ]

O JornalO Jornal(Maranhão) [ Links ]

O PaizO Paiz(Rio de Janeiro) [ Links ]

RevistaRevista Educação(São Paulo) [ Links ]

RevistaRevista El Monitor de la Educación comum (Argentina) [ Links ]

Revista Revista Escuela Moderna(Espanha) [ Links ]

4 We translated Stockholm Central Institute of Gymnastics (GCI) to Portuguese. For some time, the Institute was called Royal Gymnastics Central Institute. Throughout the text, we refer to the Institute using the acronym GCI, as is known worldwide.

5Pehr Henrich Ling (1776-1839) was the founder of Swedish Gymnastics. Further, the role of Ling in the creation of the Institute will be addressed.

6It is important to say that these authors wrote works that until today are considered important milestones in the writing of Physical Education history. If, in any way, we can set limits on the deal with History, today their works are mobilized as rich sources, which have allowed contemporary historians to construct other plots for the writing of history. In addition, in his works, there are significant clues of subjects, institutions, manuals, among others, for the development of new research problems.

7For Melo (1999), in this phase are included the authors Lino Castellani Filho (1988), Mário Cantarino Filho (1982) and Paulo Ghiraldelli Júnior (1988).

8Here there is no exhaustive survey of works that thematize the history of gymnastics. Undoubtedly, there are other research studies that could enter this list - a task that would require more care and a specific study of historiographical criticism. But this task is beyond the scope of this text.

10Certainly, as pointed out in note 5, other studies exist, but our goal was not to make an exhaustive survey of them.

11The GEPHGI, under the coordination of Dr. Andrea Moreno, brings together professors, PhD and scientific initiation students, being a sub-group of the Physical Education Memory Center (CEMEF) and works in the framework of the Center for Studies and Research in History of Education (GEPHE), both of UFMG.

14His name is found with different spellings in the research studies - Per Henrik Ling and Pehr Henrik Ling. We kept this spelling because it is the one that appears most frequently.

15Ling foi para Copenhagen em 1799, com 23 anos de idade. There, he entered University, improved his contact with different languages, got involved with writing poems and had contact with fencing and gymnastics. He returned to Sweden in 1804 (WESTERBLAD, 1909; GEORGII, 1854; LEONARD, 1923; PEREIRA (S/d); MARINHO, 1958). It is important to stress that these authors, by biographing Pehr H. Ling, mobilize documents belonging to the historical archive of the GCI, many in the Swedish language, and, in general, coincide in these statements.

16Upon returning to Sweden, Ling replaces the fencing professor at Lund University, where he remains for 8 years. There he also teaches gymnastics, and delves into studies of anatomy and physiology. Gaining the confidence of teachers and students, he was invited to exhibit his experiences in Gothenburg, Malmo and Christianstad. According to Leonard (1923), during his time in Lund, Ling experiments and organizes his method of instruction. He dedicated himself to understanding the human body and discovering its needs, to be able, after this stage, to select and apply the exercises that could meet those needs.

17According to Leonard (1923), Ling continued to teach fencing at the Karlberg Military School until 1825, and in 1821 he also acted as an instructor in gymnastics and fencing at the School of Artillery in Marieberg.

18Isaias Tegnér issued a letter introducing Ling, which was sent along with the precursor’s physical training project to the Swedish State. Isaias was known in the country for the song War Song for the Militia of Scania and for the Swedish Academy Award for his patriotic poem Svea, at a time when patriotism was a matter of extreme relevance in the Nordic region (LEONARD, 1923). However, it is good to remember that it was not without difficulty that Swedish educational gymnastics was able to convince of its importance; both Marinho (1958: 239) and Pereira (S/d, p.295), indicate that Ling had already made contact for the creation of the Institute that was denied, due to the existence of a thought that in Sweden there was a “sufficient number” of street entertainers and acrobats.

19In 1813, Sweden was under the government of Charles XIII, who was responsible for the creation of Stockholm Central Gymnastics Institute (PEREIRA, S/d, p. 280).

20According to Leonard (1923), in 1813, to establish the Institute, he received a subvention income to rent spaces and buy material and a monthly amount to occupy the position of director. At the end of 1815 the Swedish government allocated an amount for the improvement of the facilities, representing a sum of more than 20 times the initial investment, thereby demonstrating a certain belief in the Ling project. (LEONARD, 1923).

21With a front measuring about 12 meters, an arch was formed, with construction on one side of HamnGatan Street, of about 60 meters, and on BeridarebansGatan Street, approximately 72 meters. Near the center of street HamnGatan was the entrance, with the name “Central Institute of Gymnastics”.

23This division refers to the organization present in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From 1814 to 1818, at least, the direction and execution of classes were entirely Ling’s responsibility. The authorization for hiring employees came only in 1818, for reinforcement in the reception, meeting a growing demand.

25Defending Ling’s ideas, which he considered novel at the time, he propagated the thesis that the beneficial effects on the body are not only the result of changes in the muscular system, but mainly of the influence exerted on the nerves and blood vessels (PEREIRA, S/d; LEONARD, 1923).

26Ling (1940). In Portuguese, this work has been translated as “General principles of gymnastics”, “Manual of gymnastics” or “General basis for gymnastics”, as we can observe in Moreno (2015).

27P. J. Liedbeck (1802-1876), Ling’s son-in-law, was a student at the Institute and taught anatomy there (PEREIRA, S/d, p. 365)

28Ling’s other writings on gymnastics are short articles, fragmented writing, regulations with descriptions of different types of exercises. For the most part, his work is of dramatic poems, whose tone exalts the virtues of old Scandinavia (LINDROTH, 1979; GEORGII, 1854).

30Georgii, according to Leonard (1923), worked with anatomy knowledge in the 3 branches of gymnastics. He left the institute in 1949, when he went to London to disseminate the Swedish gymnastics. He established a private institution in the country and remained there for 28 years, before returning to Stockholm.

31According to Leonard (1923), the statutes foresaw that all teachers of the Institute should have graduated in the same institution. However, it is worth to emphasize that, over time, there were differences between the teachers and the successors of the method. One of the main divergences concerned the division of the method, and hence, of the Institute, into departments. This divergence was characterized by Lindroth (1979) as the lingian X natural method. The first represented by Hjalmar (and later by Torngren) in contraposition with Nyblaeus (and later Balck). In the first one, the educational method was considered complete and could be applied in the army or in school.

32The course, accomplished in three years, was divided as follows: one year for gym instructors, to work in the army, two years for gymnastics teachers, to work in schools; and an additional year for those who want to devote themselves to the practice of medical gymnastics, also known as gymnast-doctor, after which they were authorized to work in health prevention and cure (POSSE, 1891).

33In the cities where there were no financial conditions to hire graduate teachers, the Institute offered courses so that other teachers, without training in gymnastics, could apply a basic gymnastics (POSSE, 1891).

34According to Leonard (1923), the total number of foreign men at the Institute in the mid-1900s was about sixty. Even the number of women, according to the author, which was not so high before, increased every year, approaching the number of men. During the fall of 1900 there were male students from Greece, Norway, Denmark, Finland and the United States. There were women students from Russia, the Netherlands, and England.

36Annals of the Congrès International de L’éducation Physique. Paris, August 30 to September 6, 1900. Lars Mauritz Torngren, director of the Central Gymnastics Institute of Stockholm was present.

37Annals of the Congrès International de L’éducation Physique. Paris, March 17 to 20, 1913. Nils Fredrik Sellén, director of the Stockholm Gymnastics Central Institute, was present, performing practical presentations of the Swedish Gymnastics.

41This survey was carried out by consulting the database of the Brazilian Digital Journal Library, searching for the keyword gymnastica sueca, during the year of 2018.

42Gymnastica Sueca. Jornal do Commercio, Rio de Janeiro, 07/24/1892; A Gymnastica Sueca. A ordem, Minas Gerais, 10/22/1892; A Gymnastica Sueca. Cidade do Rio, Rio de Janeiro, 06/16/1897; A moda. A Nação: Orgam do Partido Republicano, São Paulo, 11/09/1897; Nossas Gravuras. A Estação: Illustrated Newspaper for the family, Rio de Janeiro, 09/30/1898; Echos. Jornal do Recife, Recife, 05/24/1905; Actualidades. O Paiz, Rio de Janeiro, 02/13/1909; The day of a man in 1920. O Commercio de São Paulo, São Paulo, 07/26/1909.

43As already mentioned, there is a growing discussion in the educational and political field on the relevance of the Swedish system to support school practices. We are talking about a Brazil, that had not developed its own method of gymnastics yet, and it has in Europe an important cultural and economic reference.

44In an article, Moreno (2015) discusses a set of manuals that disseminated the Swedish gymnastics in the Portuguese language. In addition to the manuals written by Pedro Manoel Borges, Antônio Martiniano Ferreira, Paulo Lauret, Arthur Higgins and Ludvig G. Kumlien, cited in this paper, we can also mention: Schereber, Manoel Baragiola, Domingos Nascimento, and Caldas and Carvalho (PUCHTA, 2015).

46In the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo, on February 14, 1921, it is the first news recorded of Swedish teachers’ names working with massages and gymnastics.

47This is the generic expression that appears in the sources, when referring to the Swedish professor.

49Fritjof Detthow lived in São Paulo until his death in 1947, at 61. The research still investigates until when the teacher keeps the relation with the State.

53Newspaper O Correio Paulistano, April 9, 1927; and Teaching Yearbook of the State of São Paulo, 1926, p. 314

67SÃO PAULO. Decree nº 3.356, of May 31, 1921. Regulates the law n.1.750, of December 8, 1920, which reforms public education. Legislative Assembly of São Paulo State, São Paulo, 1921. Available from: <http://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1921/decreto-3356-31.05.1921.html>. Accessed: Oct. 19, 2015. To learn more about the Sampaio Dória Reform , cf: Honorato (2017).

Received: December 12, 2018; Accepted: April 17, 2019

texto em

texto em