Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.36 Belo Horizonte 2020 Epub 30-Jul-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698218538

ARTICLE

LITERATURE REVIEW: WORKSHOPS

1Universidade Federal de Tocantins (UFTO). Palmas, TO, Brasil. Email: <fjfelipe1982@gmail.com>.

2Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP/Rio Claro). Rio Claro, SP, Brasil. <mr.camargo@rc.unesp.br>.

This is a bibliographical review on workshops as an educational modality. We analyzed 256 scientific articles from journals contained in the evaluation area of Education in the Sucupira Platform of CNPq that had the term workshop either in the title, keywords or abstract. They were categorized and described according to their objectives and modes of execution: job workshop, didactic workshop, pedagogical workshop, reading and writing workshop, artistic workshop and therapeutic workshop. Of the articles surveyed, only six focused on analyzing the practice of workshops as an educational modality; the rest employed workshops as a means of developing diverse themes. Finally, we argue that the practice of workshops in the field of education can prove to be a fruitful instrument for the production of knowledge, subjectivation and emancipation processes.

Keywords: educational processes; teaching methodology; non-formal education; workshop

Trata-se de uma revisão bibliográfica sobre oficinas enquanto modalidade educativa. Foram analisados 256 artigos científicos oriundos de periódicos contidos na área de avaliação Educação na Plataforma Sucupira do CNPq que possuíam o termo oficina, seja no título, nas palavras-chave ou no resumo. As oficinas foram categorizadas e descritas de acordo com seus objetivos e modos de execução: oficina de trabalho, oficina didática, oficina pedagógica, oficina de leitura e escrita, oficina artística e oficina terapêutica. Dos artigos levantados, somente seis tinham como foco de análise a prática de oficinas enquanto modalidade educativa; os restantes empregaram as oficinas enquanto meio para o desenvolvimento de temas diversos. Por fim, argumentamos que a prática de oficinas no campo da Educação pode se revelar um instrumento profícuo para a produção de conhecimentos, processos de subjetivação e emancipação.

Palavras-chave: processos educacionais; metodologia de ensino; educação não formal

Esta es una revisión bibliográfica de los talleres como modalidad educativa. Se analizaron 256 artículos científicos de revistas contenidas en el área de evaluación de Educación en la Plataforma Sucupira de CNPq que tenían el término taller, ya sea en el título, en las palabras clave o en el resumen. Se clasificaron y describieron según sus objetivos y modos de ejecución: taller, taller didáctico, taller pedagógico, taller de lectura y escritura, taller artístico y taller terapéutico. De los artículos encuestados, solo seis se centraron en la práctica de talleres como modalidad educativa; el resto utilizó los talleres como un medio para desarrollar diferentes temas. Finalmente, sostenemos que la práctica de talleres en el campo de la Educación puede resultar un instrumento útil para la producción de conocimiento, procesos de subjetivación y emancipación.

Palabras clave: procesos educativos; metodología de enseñanza; educación no formal

INTRODUCTION

Scientific events generally reserve space in their schedule for a type of activity in which congressmen extrapolate the usual listener position and share the responsibility for carrying out the work. That is, workshops. In reality, this educational modality is not restricted to academic meetings, nor to any specific field of knowledge. Workshops are held in a wide variety of educational contexts: in universities, schools, hospitals, clinics, parks, on the street. However, when consulting scientific literature, we noticed that few publications are dedicated to conceptualizing them: texts predominate in which workshops are the means for the development of a theme, hardly the object of study in question.

In view of these considerations, we prepared this study based on a bibliographic survey on workshops. This endeavor comes from the doctoral thesis “Comedy or If a workshop in a doctoral thesis or Notes...”, defended by the first author of this study, whose purpose is to argue in favor of the practice of workshops as an emancipatory educational modality, from conducting reading and writing workshops based on Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy.

We intend, from the studies gathered here, to discuss the various meanings referring to the term workshop, how they are organized and shown to the participants, as they vary according to purposes and spaces of realization. It is noteworthy that, because it is a survey obtained from search tools and databases of varied scientific journals, the researched articles sometimes reveal different points of view on the subject.

The survey was conducted from the Sucupira Platform by Fundação Capes (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal do Nível Superior - https://sucupira.capes.gov.br)3 . In it, it is possible to consult the journals evaluated by field of knowledge. For this survey, we selected the journals classified among strata A1-B2 in the Quadrienium Classification Event 2013-2016, Education assessment area. From this list, in April 2016, we accessed, one by one, the electronic addresses of classified journals. On the search screen, we searched for the term “workshop” in the title, abstract, or keywords of the articles. All those articles that resulted from this search process were included in folders, organized by journal for further analysis.

It is noteworthy that not all journals returned articles that met our search criteria; in addition, some journals did not even have search engines on their websites, or apparently had failed to execute the search request. In such cases, invariably, such journals were discarded from the scope of the research. The option to use Sucupira Platform over Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) is because we understand that many Brazilian journals are not indexed in this scientific collection platform.

Subsequently, we read the articles. Those who had the term “workshop” without the details of the proposal executed or that referred directly to a workplace, a proper noun, and whose bias was not educational, were excluded. At the end, 256 articles were analyzed.

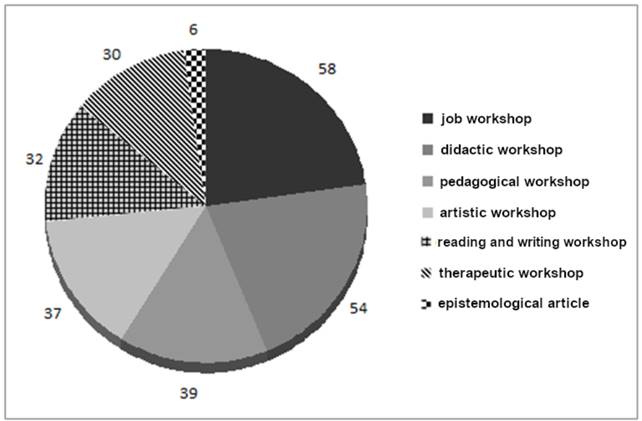

These 256 articles were classified according to the workshop execution methodology. We distinguished the following methodological categories: didactic workshop, artistic workshop, job workshop, pedagogical workshop, therapeutic workshop and reading and writing workshop. Although the methodological execution of the same workshop may bring artistic and didactic elements, for example, in our view, each workshop has the predominance of one of the components, hence the insertion in this or that category.

However, before the background of each methodological group is described more fully, we will divert the focus of the discussion to show some quantitative data that illustrate the current panorama on the development of workshops in Brazil.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

Once in possession of the 256 surveyed articles, which had the term “workshop” either in the title, abstract or keywords, they were organized into a spreadsheet in order to facilitate obtaining the desired information through filters.

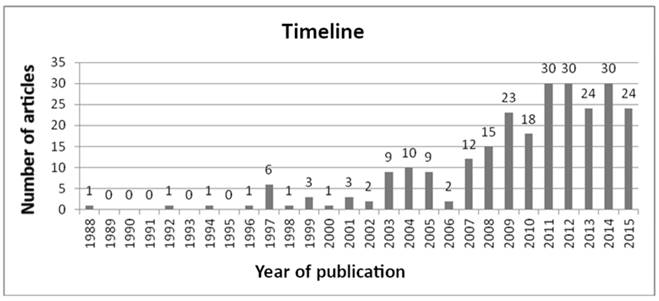

The first feature we consider is the year of publication of the articles. The chart below corresponds to the distribution of publications over time:

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors.

Figure 1 Distribution of publications over time.

As soon as we look at the chart, we notice the increase in the number of publications from the year 2007. We attribute this slight growth, among other reasons, to the fact that it coincides with the advent of online dissemination of scientific journals, initiating the tendency to encourage publication in this format, rather than the conventional one, in print.

Even so, some magazines have digitalized their printed collection and, for this reason, we have noticed the practice of workshops as an educational modality in Brazil since 1988, with the publication of the article Workshop on Literary Creation by Luiz Antonio de Assis Brasil, in Letras de Hoje, a PUC-RS publication. There was then a production gap until the early 1990s, interrupted by the publication of Physics Workshops: An Experience in Continuing Education, by Eduardo Adolfo Terrazzan and Ernst Wolfgang Hamburger, in the Brazilian Journal of Physics Education in 1992. From then on, with the exception of 1993 and 1995, we found at least one study published per year to date. However, it should be emphasized, once again, that the material analyzed in this investigation results from articles available online, that is, we cannot affirm the inexistence of publications prior to the year 1988, since they may have occurred via print editions not yet digitalized.

In this early period, the 1990's, we highlight 1997, with six publications, a relatively larger amount than the other years. This fact stems from the release of issue 27, volume 15, of the Perspectiva journal, edited by the Federal University of Santa Catarina, whose title is Libertarian Pedagogy, where half of the twelve articles published mention the use of workshops as an educational strategy.

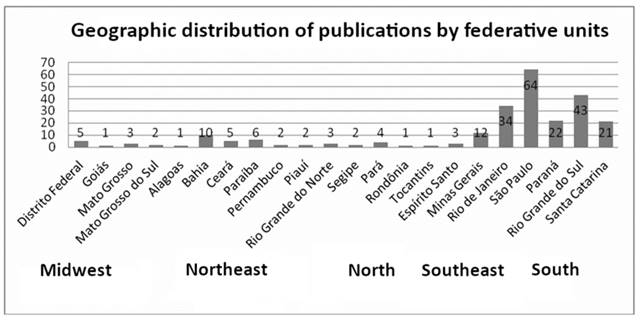

As for geographic distribution, the chart below lists the number of articles per Brazilian federative unit.

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors

Figure 2 Geographic distribution of publications by federative units.

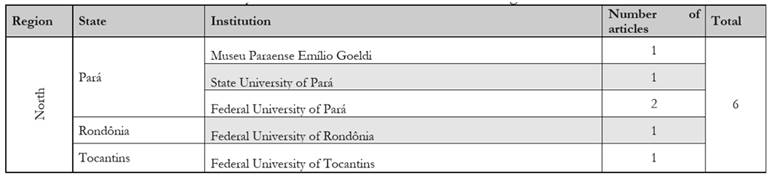

Note the simple scientific production that refers to workshops in the Northern Region of Brazil (2.44% of the total). Only three states (Pará, Rondônia and Tocantins) reported the occurrence of studies, and only the state of Pará, in this region of the country, has more than one article. Acre, Amapá, Amazonas and Roraima did not compute a single article.

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors

Chart 1 Publications by State and Institutes of the Northern Region

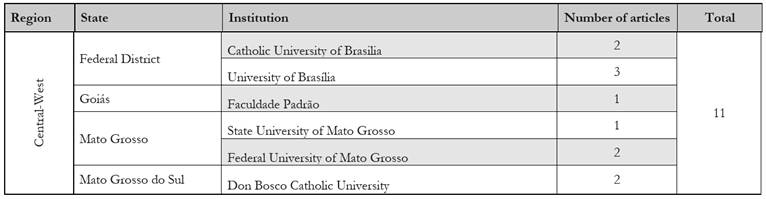

All states in the Central-West Region showed studies in this scope, although not many (4.45% of the total). Federal District stands out, due to the articles produced by the University of Brasília and the Catholic University of Brasilia.

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors

Chart 2 Publications by State and Institutes of the Central-West Region

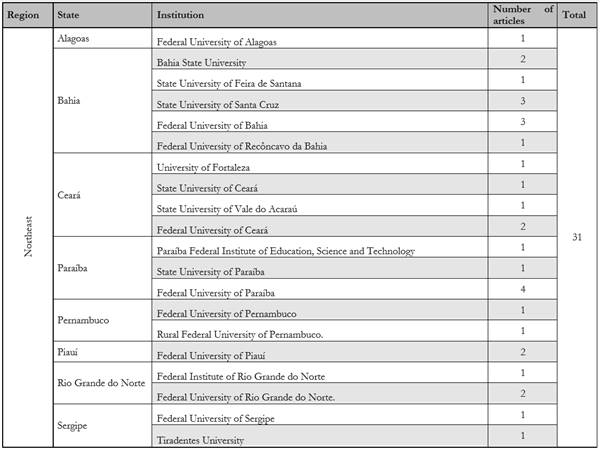

The scientific production, in this aspect, intensifies from the Northeast Region (12.55% of the total). Although the state of Maranhão does not have any studies, all other states have publications, and only the state of Alagoas has only one registered article. Bahia stands out for being the state with the highest occurrence of studies outside the Southern portion of the country, due to institutions such as the Federal University of Bahia and Santa Cruz State University, with three publications each. However, regarding the Northeastern institution with the largest number of articles, the post goes for the Federal University of Paraíba, with four.

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors

Chart 3 Publications by State and Institutes of the Northeast Region

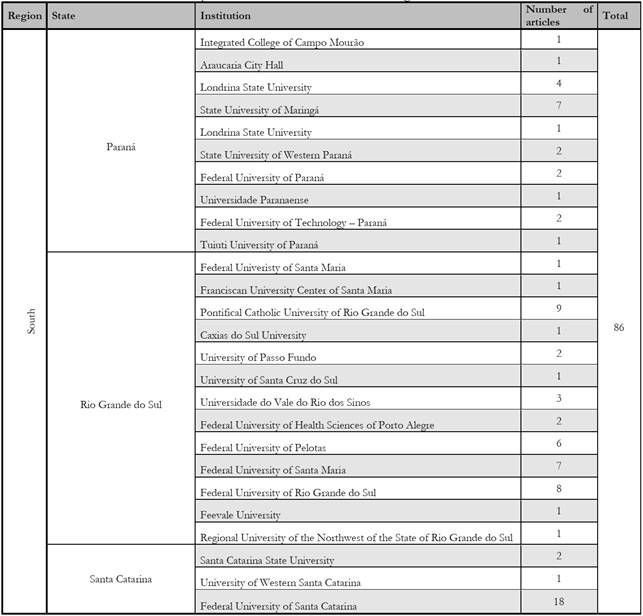

Statistically, one in three studies addressing workshops comes from the South Region (34.82% of the total). Half of them are produced in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, that is, forty-three articles. The institutions that contributed the most to this index were the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (9 articles), the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (8 articles), the Federal University of Santa Maria (7 articles) and the Federal University of Pelotas (6 articles). Paraná and Santa Catarina are states with similar quantities of productions, 22 and 21, respectively. In Paraná, institutions run by the state itself stand out, the State University of Maringá (7 articles) and the State University of Londrina (4 articles). Santa Catarina contains the institution with the second highest index of publications on workshops on a national scale, the University of Santa Catarina (18 articles).

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors

Chart 4 Publications by State and Institutes of the South Region

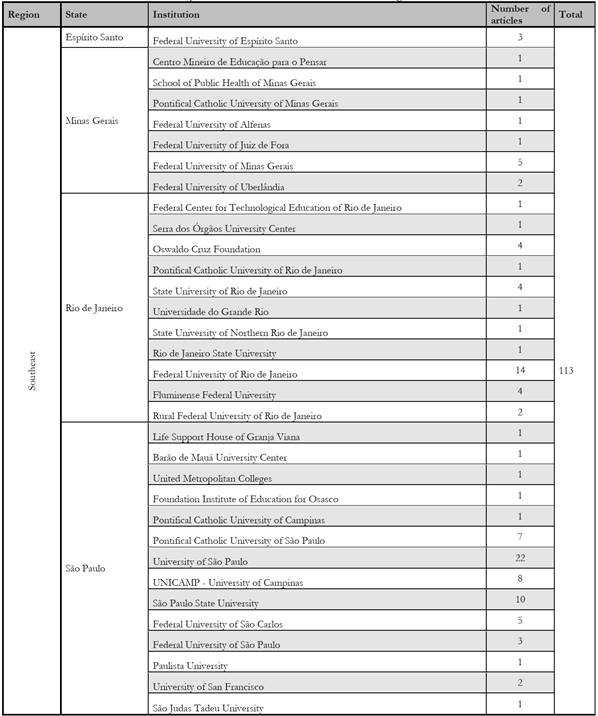

Finally, the Southeast Region, with a productivity rate slightly lower than half of the national general (45.74% of the total). Espírito Santo is the state with the least amount of studies, with only 3 articles, all derived from the Federal University of Espírito Santo. Then, Minas Gerais has 12 articles, five of which originated at the Federal University of Minas Gerais. Rio de Janeiro, with 34 articles, is the third largest state in terms of publications, fourteen of which come from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. São Paulo is the state that most produced studies referring to workshops, with 64 articles. Practically two thirds of this amount (40 articles) comes from the three state-run universities, the University of São Paulo (22 articles), the São Paulo State University (10 articles) and the University of Campinas (8 articles).

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors

Chart 5 Publications by State and Institutes of the Southeast Region

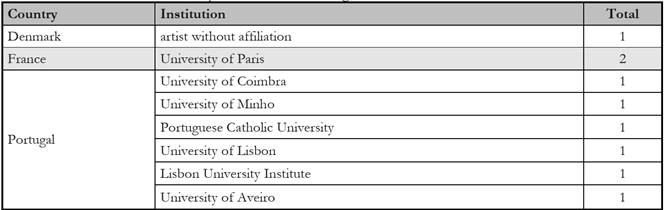

We also highlight the scientific production of foreign authors whose articles were published in Brazilian journals. Portuguese journals evaluated by CAPES were also used in the survey:

Source: Sucupira Platform. Compilation by the authors

Chart 6 Publications by authors linked to foreign institutions

The holding of workshops as a way of performing Education has, in theory, certain particularities: freedom of creation and autonomy of execution, among others. From this premise derives the multiplicity of objectives, achievements, perspectives, etc. that a workshop can encompass.

We sought to group the articles surveyed according to the way the workshops were conducted, categorizing them. However, this categorization is not intended to restrict the scope of action of a particular workshop; on the contrary. The same workshop can even have characteristics that indicate different categories. However, when analyzing the articles individually, we chose to fit them into a single category, according to the aspects that, in our view, best reflected the workshop proposal. In this study, we distinguish seven categories of articles explicitly explained by the mode of implementation:

Didactic workshop: |

Its purpose is to disseminate specific knowledge. Usually occurs through oral exposure. Lecturers are often the focus of the workshop. |

Artistic workshop: |

predominance of artistic making. The person who conducts the workshop proposes the activity, but the participants are generally free to develop the proposal. |

Job workshop: |

It is characterized by dialogue and doing around an issue. There is no predetermined end, the proposal unfolds according to events. Power between workshops and participants is often egalitarian. |

Pedagogical workshop: |

focused on the continuous formation of teachers. |

Therapeutic workshop: |

focused on the psychological treatment of its participants. |

Reading and writing workshop: |

focused on the practice of reading and writing. |

Workshops, spaces in production: |

articles that address conceptual questions about the workshop theme, as object of research, bibliographical surveys, etc. |

The following graph shows the distribution of articles according to categories:

FROM ARTICLES TO WORKSHOPS

Below, we will portray the workshop categories, one by one, in descending order in relation to the quantity of works, from citations extracted from the articles that compose this study. Before the description, however, we have included a brief synthesis, between parenthesis, to drive understanding of the category as a whole.

Job Workshop (58 articles)

(Knowledge production combined with the debate of ideas - activities that encourage problematization - participants guide the course of conversations - search for understanding - autonomy and knowledge production)

In job workshops, the focus is generally on the production of knowledge combined with the debate of ideas. From previously elaborated problems, the group of workshop and participants gathers to talk and conjecture about possible referrals to the topics in question.

The circle and dialogue workshop found space at the peoples' summit for debate and information exchange (...) where dynamically topics such as social justice, environmental justice, gender equity, ecological economics, universities and sustainable cities were on the agenda. Participation of listeners was voluntary, where everyone was invited to participate in the debates, the flow of people was constant and the workshops took place continuously, where many different people participated in some or all stages of the proposed activity that morning (REIS et al., 2014, 367).

In some cases, various practices are used as devices that encourage problematization. Usually, participants are asked, through the use of common instruments, to produce something at their discretion. Then, as they observe the assembled works, the debate begins.

In the Photo Workshop, workers produce photographs of their work situations to be analyzed by the group itself, and confrontations occur, as researchers/work analysts and photographers comment and analyze work activities (PACHECO et al, 2012, p. 261).

It is usually up to the workshopper to conduct the dialogue. However, it is not uncommon for participants, based on their own demands, to steer the conversation.

(...) the evaluation parameters and limits are determined through an interactive and negotiation process that involves the research subjects (CAMATTA et al, 2011, p. 4407).

It is natural, precisely because it is a meeting between people, that the worked themes can generate heated discussions and clashes between opposing positions. Thus, one purpose that stands out in this workshop category is the search for understanding.

(...) Workshops, as we conceive them, can work as a strategy for producing consensus (...) when there is no unanimity of opinion on a given subject, either because there is no data related to the theme, or because existing data are controversial with each other (CAMPOS et al, 2010, p. 226).

Thus, by enabling dialogue, confronting ideas, problematizing issues that are relevant to those involved in the process, workshops are mechanisms that favor autonomy and the production of knowledge.

Breaking the hierarchy of relationships is, through available tools, proposed by the workshop, providing the construction/elaboration of knowledge that is performed in the relationship with those involved and in the act of doing things together (PREVE, 1997, p. 167).

Didactic Workshop (54 articles)

(Alternative practices to oral exposure - to confront participants with the object of study - to organize acquired knowledge - to contribute to intellectual emancipation - to promote knowledge as cultural diversity or extensive action.).

Didactic workshops are, in general, alternative means to the oral exposition that characterizes a classic class. Although some workshops in this category still use this didactic resource, most of them start from an experiment or are dedicated to teaching how to produce something, step by step, as a strategy to foster the dissemination of specific knowledge among participants.

A current methodology adopted by me, as a teacher of the subject, is to provide a range of practical activities options that students can perform (...) such experiments have been very significant from the point of view of experimenting the worked content and discussed in the classroom (BARROS, 2009, p. 302).

This premise of didactic workshops, which is to confront participants immediately with the object of study in question, instigates learning, since it shortens the distance between subject and knowledge, making the understanding of reality even more palpable.

In the laboratory space, the student faces real problems, so they think, reflect and analyze scientific theories in light of concrete questions. Other than that, the experimental activities create in the classroom a playful space, capable of motivating the students to study the sciences (RINALDI & GUERRA, 2011, p. 655).

Moreover, according to the themes and the ways in which they are approached, didactic workshops can prove to be useful tools to organize the acquired knowledge beyond the curricular disciplines, privileging the holistic over the systematized but fragmented knowledge.

Thematic workshops seek to treat knowledge in an interrelated and contextualized way, involving students in an active process in the construction of their own knowledge (Silva et al, 2014, p. 483).

And precisely because it favors the active construction of knowledge, didactic workshops contribute to the intellectual emancipation of the participants: even if the workshopper is the coordinator, the way work develops provides autonomy. In particular, it appears that such freedom even broadens the scope of the subject matter.

What encouraged me most in this didactic transposition work was the possibility of dealing with an extremely discriminated subject in our curriculum (...) (POLI, 2009, p. 226).

Well, if it is possible to see that didactic workshops are efficient mechanisms for the promotion of the extensive knowledge, the argument that cultural diversity among the participants collaborates to further increase the educational process is also important.

All members of the group can participate in the workshops, regardless of age, culture or interests, as the method allows discussing a wide range of details for which their experiences and knowledge are important (GIASSI, 1997, p. 153).

Pedagogical Workshop(39 articles)

(They improve teaching practice - deepen the knowledge related to curricular subjects - they work with fundamental aspects of Education, that permeate all school subjects - they are aimed at the educator's own self-criticism - they produce diverse didactic material).

Pedagogical workshops, unlike the other categories, have a specific target audience: teachers. The analyzed articles, almost totally, are addressed to educators of regular public education. Generally, the activities focus on the process of continuing education, while improving teaching practice and stimulating research.

(...) It is characterized as a space for training and professionalization, since the main objective is the theoretical training of teachers, enabling the transformation of subjects in the appropriation process of theoretical knowledge and its form of teaching organization. It is also a space for research, as it becomes a privileged place to investigate the teaching learning movement in the process of elaboration, development, analysis and synthesis of teaching activities (MORAES et al., 2012, p. 141).

There are different approaches in this category of workshops. The predominant one is where teachers deepen their knowledge on the subjects they teach, under the coordination of a specialist who, in turn, is guided by the current scientific references.

From the discussion and analysis of different proposed activities, teachers were suggested to develop, in a mediated way and based on the references shown above, teaching proposals appropriate to the reality of their classrooms (MORETTI, 2011, p. 388).

Another possibility, however, brings together teachers who do not necessarily belong to the same field of knowledge: they are workshops that work with fundamental aspects of Education, which permeate all school subjects. For example, reading and writing:

The main objective of the workshops was to offer participants a framework for the development of pedagogical work with reading and writing, from the perspective of textual genres, associated with the practice of activities and realization of work projects. The whole process was developed in a critical-reflexive line, from the integration of teachers' previous knowledge to the appropriation of new knowledge and contextualized practices (PAVIANI & FONTANA, 2009, p.80).

There are, however, pedagogical workshops that do not simply aim to discuss ways of teaching certain concepts or developing unique characteristics of students; there are workshops that are designed for the educators' own view of themselves, workshops, for example, that address the ways in which this educator can communicate with the world, with their students:

The organization, design and implementation of the workshop as a vehicle for teachers' professional development, aimed at improving participants' knowledge and skills regarding the use of appropriate and efficient feedback, promoting positive feelings regarding the importance of feedback strategies and also the effective application of such strategies in the classroom, with reflection on them (FONSECA et al., 2015, p. 180).

Anyway, since the workshop is a space that encourages action, creation, reflection, etc., it is natural that some materials are produced throughout its development. Often, these productions emancipate themselves from their creators to reverberate in other classrooms in the form of teaching materials.

During the execution of the workshops, innovative materials were produced that were subsequently used in teachers' classes in different subjects, and today they constitute a collection of school didactic material (ABÍLIO et al., 2012, p. 184).

Artistic Workshop (37 articles)

(Actions follow according to the moods of the people involved - autonomy in the deliberation of the proposal - plurality among the participants - question of authorship.).

Here is an account of an unusual journey into the world of Theater in Science Education, to the feverish and vibrant world of a collective process of Peter's scenic montage and the sea or how fish will fly. (...) A cartography of the ways in which theater provides other ways of thinking about Science teaching (OLIVEIRA, 2012, p. 561).

One moment please! Do you enact in Science classes? Maybe in a… theater workshop! In art workshops, the actions, events, wills, desires that come from experimentation follow the moods and horizons of the people involved.

As the exact way the workshop would be given was not defined, the first meetings had as their objective, above all, the decision, together with the users, on how this activity would work (MENEZES et al., 2008, p. 25).

Although not a rule, we identified in the artistic workshops an autonomy in the deliberation of the methodological proposal by the group of participants, that is, it is not usual for the workshop's directions to follow a pre-established script. From the choice of material, to what will be produced; how to work; or even the option for idleness: it is the wills that usually guide the unfolding of the workshop. One moves from the proposal to freedom of action.

The workshop (...) was directed to a group of students without film education, coming from areas as different as speech therapy, physiotherapy, biology, psychology, education and journalism. Only from the study of Godard's essay film could they construct their own scripts, as well as a critical reflection on writing in the cinema (LEANDRO, 2003, p.682).

Since autonomy is a potential feature, another trait that we find in art workshops is plurality among participants. It is expressed by the diversity of ages, occupations, goals… Crucial, in this type of workshop, is the implicit agreement between them, motivated by the enthusiasm of being part of the event, upon which the success of the undertaking will depend.

On the other hand, with regard to these participants, the studio is a space for representations, image production, transfiguration, revelation, exercise and the updating of the imagination. Also a place for the unpredictable, the Atelier constitutes a “language event”, in which different levels of social representations interact, intersect, overlap, mix, clash, and exchange. As a plastic reality, dilated in time and space, it gathers motivations, effects and repercussions that go beyond the strictly associative universe (TURRA-MAGNI, 2010, p.65).

Because it is a production space where creativity is privileged, which brings together plural and autonomous personalities, one aspect comes up and raises questions: the question of authorship. If doing is collective, how are individual marks distinguished in the conceived work? Otherwise, if each of the present people produces something essentially his/her own, and then expose it to the group, what ensures correspondence with the workshop's initial purpose?

One of the lines of work developed by the company are workshops for the creation of life stories with children in public schools, which include collective oral performances, in which the children themselves narrate the stories they collectively created from lived experiences. The project involves aesthetic, subjective, cultural and political reflections, and its focus on working with children is to help them develop and report personal narratives and to show them in scenic terms. In this project, authorship is closely linked to the sharing of stories and their power to create communities in the classroom, in which social and cultural differences are not confused with prejudice (…) (GIRARDELLO, 2015, p.19).

Reading and Writing Workshop (32 articles)

(Exercise of language - encourages production but does not focus on assessing the material produced - welcomes those in the early stages of literacy - enhances the degree of criticality)

In reading and writing workshops, as the name implies, the focus is on activities related to the exercise of language. It is common to perform these in schools, but they are not restricted to the school space. Some workshops are devoted exclusively to reading; others to writing. There are also those that combine the two operations.

The workshop begins by reading and discussing literary, journalistic, poetic text, etc. Then, it is time to write about what was discussed, or about another topic, if this was the choice of the participants. Then, each one reads what they have written for others to comment on (BORGES, 2008, p. 53).

Although school is the privileged space for reading and writing in workshops, due to the fact that they are group activities, the group does not evaluate performances, such as those recorded in exams and grades, but the encouragement and the demystification of the act of reading and writing.

The group willing to workshop meets weekly for reading and writing practice; However, this is different from the school: by freeing the subjects of writing and the directions of reading, it is offered to the participant a place of reader and writing-writer regardless of what is right/wrong, good/bad (LANGE, 2010, p. 166).

Precisely because it is a space, among other things, to encourage reading and writing, workshops also welcome those in the early stages of literacy.

First, I clarified to the interns that fluency in reading would not be a condition for attending the workshop and that those who had difficulty following could understand the story by listening, because we would do more than one reading aloud (BOECHAT & KASTRUP, 2010, p. 31).

Of course, the exercise of reading and writing provides participants with an improvement in the degree of criticality when faced, for example, with headlines in newspapers, magazines and advertisements.

With regard specifically to the analysis of the journalistic text, the work with workshops provides participants with the identification and classification of this heterogeneous textual modality, and, from the recognition of the alleged journalistic impartiality and objectivity, the identification of the linguistic resources used to mark or to mask the newspaper's intentions (BENITES, 2001, p. 34).

Thus, reading and writing workshops are characterized as an exceptional space for the formation not only of readers, but autonomous people, who build their own worldviews and continually seek emancipation.

The workshop focuses on the relationship with writing — dynamic and open notion — which includes the aspects related to the Subject and the sociocultural environment to which it belongs and in which Writing exists and assumes itself sometimes in its personal (self) relational and social (for others) nature, link and expression of the subject's relationship with himself, with others, with the world (CARDOSO & PEREIRA, 2015, p. 89).

Therapeutic Workshop (30 articles)

(Psychological attendance to participants - they contribute to the participant's judgment of themselves - are not intended only for those suffering from mental illness or disorder - designed according to the psychological current on which they are based).

Therapeutic workshops have as their purpose the psychological attendance to the participants. They are mostly conducted by health professionals. Activities may involve artistic elements, being supported by a conversation wheel or even based on a game, for example; however, what is always in view is the organization of a favorable environment for participants to comment.

This project aimed to build a therapeutic listening space for children with psychological distress in which the playful and the symbolic served as a support for them to get in touch with their psychical reality (COSTA et al, 2013, p. 237).

By bringing together a group of people who have a common condition, the use of playful and artistic components in the workshop activities can contribute to maintaining the participants’ judgment of themselves, as well as the view that others make about them.

In this way, the drug user, generally recognized/reduced only to the role of dependent, can, through the performance presentation in the theater therapy workshop, be seen and recognized as an “other” by the attending audience, that is, can access another “other” that is also him (LIMA, 2008, p. 99).

As in a symbiote movement, in which participant and “other” — whether health professional, family, audience, etc. — combine experiences arising from workshop activities, sometimes we lose sight of who is intended for therapy, as it is difficult to pass unscathed to the event.

The workshops made this space possible — to tell and retell; to listen and be moved, and, in this movement, to reconstruct identities (MENEGHEL et al., 2005, p. 114).

Given its eminently focused character on primary health care, therapeutic workshops are mainly held in hospital institutions (clinics, psychosocial care centers, etc.). However, they are not intended only for those suffering from illnesses or psychical disorders. There are also workshops for family members of health system users.

(...) in order to create an art and creation space for caregivers to have the opportunity to express and reflect on the feelings generated from the birth of a disabled child, as well as the possibility of finding support to understand their role with their children (PEREIRA et al., 2009, p. 169).

Finally, it is emphasized that the planning of therapeutic workshops takes place according to the psychological current on which it is based. Moreover, as the health professional coordinators are often researchers or students in formation, the investigative dimension of such workshops is noteworthy.

Psychotherapeutic Workshops are based on a psychoanalytic mode of intervention that uses mediating materialities in light of the theory developed by D.W. Winnicott and have been characterized by representing a space that privileges both community service and the development of clinical research (GATTI et al., 2015, p. 31).

WORKSHOPS: SPACES IN PRODUCTION

Of the 256 analyzed studies, six of them were classified as empirical articles, that is, those that study the term workshop as an educational alternative, although they do not use or propose the execution of a specific workshop to argue in favor of this educational modality.

Bernardina Leal (2006), in an article entitled Workshop, promotes the practice of workshops, although recognizing that, because it is “always less formal than the usual school and academic dimensions, more active and provocative” (ibid, p. 69), it turns out not being duly recognized, as it “diverges from the well-known academic work legitimized by the characteristics of isolation, detachment and privacy” (Ibid, p. 70). In contrast, according to the author, the workshop “materializes (...) the art of involvement” (Ibid, p.70), since “It occupies public spaces. It is collective. It exposes itself. It does not fear being contaminated by people. On the contrary, it needs them. It consists of words, ideas, emotions and feelings lacking bodies to embody” (ibid, p.70). However, this group practice, an essential feature of any workshop, brings, according to the author, an apparent contradiction, since it “is collective, in that it welcomes common, intersubjective meanings, but is also individuating, because it requires thinking that do not repeat or imitate another's, a thinking as free as possible” (ibid, p. 72). Also according to the author, it is the result of this confrontation of collective and individuating aspects between, which is “the proper space of the workshop. It is still its appeal to us: come in, get in, dare. Come with us. Be my guest. Come in among us” (ibid, p. 73). Finally, the author emphasizes the premise of involvement that a workshop demands from its participants: “You cannot attend it from outside, like a lecture. In a workshop, one enters or does not enter, nor understands the appeal. We answer the call. We are the incoming” (ibid, p.73).

Maria Oly Pey (1997), in the article Workshop as an educational modality, enters the school universe by discussing the potentialities of using workshops in formal teaching spaces. From the outset, she states that the modality “breaks with the disciplinary school functioning of time because the Workshop does not fit the rhythms and temporal routines of formal education” (Ibid, p. 47). In addition, she reiterates that the workshop also breaks with the curricular organization: “It is an educational process that ignores evaluation as judgment and the truth policy of school content” (ibid, p. 47). This is because, according to the author, “the production of the Workshop does not start from the reproduction of knowledge, but from the production of a knowledge of resistance to disciplinary knowledge” (ibid., p. 47). The author argues that the theoretical-methodological foundation is based on what she understands as a project-process, in which “the workshop defines itself with initial objectives, but does not close the circuit of the possible exploration of knowledge” (ibid, p.50). Such an opening stems from the fact that the same workshop project will never be applied identically, “because each new group that works with it adds unique facets of understanding and research” (ibid, p.50). In conclusion, the author emphasizes the intellectual production character of the workshops: “They involve natural experience (knowledge) and thought experience (reflection) to produce work that materializes in products and/or authorship” (ibid, p. 51).

Graciela Ormezzano (2006), in the article Visual language in special education, addresses the use of workshops for the mentally disabled public. Although the study has this specificity, we understand that the statements shown by her can also contribute to the general argument about the practice of workshops:

In the space-time of the workshop, personal and interpersonal experiences are promoted, based on a creative and driving action for the development of the four basic functions of consciousness: thought, feeling, sensation and intuition (ORMEZZANO, 2006, p.277).

In addition to privileging cognitive functions, the author emphasizes the relationship of equality that is established between people in a workshop, regarding the role of teachers and the breakdown of hierarchy with participants:

The modality of the workshop is opposed to the traditional ways of educating, it is defined by group production and rejects the teacher's authority as the only way of knowing, promoting social intelligence and collective creativity, in which the teacher is one of the group, a facilitator, a work advisor (Ibid, p.277).

The remaining three articles move towards a perspective of therapeutic workshops, focused on the health and well-being of the participants. Teresa Cristina Paulino de Mendonça (2005), in the article Workshops on mental health: report of an experience in hospitalization, addresses the use of these educational practices within psychiatric hospitals. For the author, the workshops “seek to move towards, allowing the subject to establish bonds of self-care, work and affection with others, determining the political-social purpose associated with the clinic” (Ibid, p. 628). In this sense, with activities planned in such a way that the participants turn their eyes to themselves, they “come to be seen as an instrument for enriching the subjects, valuing expression, discovering and expanding individual possibilities and access to cultural goods” (ibid, p.628). Following, the author is dedicated to describing the function of the workshop coordinator, which is “to welcome the sounds, the speech, the forms, the acts, stating that there is a subject there with something to say and do, with interest for this something and striving for meaning in this doing” (ibid., p. 631). Naturally, as these therapeutic workshops are conducted in hospitals, the author aims at coordinators working in the health area; however, we understand that her description of the coordinating function includes other categories of workshop, since she states that:

Coordinating a workshop is listening to a language that is often wordless, through which these productions can institute channels of exchange and encounter and create new existential universes. Activities should be designed, planned and guided by ethical and aesthetic parameters and by an interdisciplinary team, conciliating the various discourses (MENDONÇA, 2005, p.631).

Ana Carolina de Assis Moura Ghirardi and Léslie Piccolotto Ferreira (2010), in the article Voice workshops: reflection on speech therapy practice, continue with the discussion about workshops applied in the health field, but in this specific case, in speech therapy clinics. According to the authors, the workshops “mostly seek to unite health, social life and culture, and transform the concept of health, as well as the concepts of health, quality of life and inclusion” (ibid, p. 170). However, due to the fact that the workshops are widely used in the health area, but without any programmatic systematization, the authors observed that, in this field, “the workshops have been shown as a diverse construction space, and consequently with some terminological undefinition” (ibid. 170). This lack of definition is highlighted in the extensive survey on the practice of workshops in the speech-language field shown by the authors, concluding that “it can be evidenced that some educational initiatives, by using the name ‘workshop’, probably intend to highlight the difference between this modality and lectures, since workshops include body and vocal practices with the participants” (ibid, p. 171).

Finally, Ariadne Cedraz and Magda Dimenstein (2005), in the article Therapeutic Workshops in the Psychiatric Reform Scenario: Deinstitutionalizing Modalities or Not?, debate, also in the field of health, if therapeutic workshops indeed contribute to the participants' emancipation. In a very critical study, the authors, at first, show their view on the function of these educational practices; according to them, workshops “need to follow the same paths as creative processes, since they are intended to accommodate singularities” (ibid, p. 309). However, their research led them to state that “(...) despite being interesting, transformative, mobilizing — therapeutic or not — workshops take a place in the everyday gear which, instead of giving way to other possible worlds, it feeds back the machine of production of subjectivities that agency the occupation of minds in order to exercise productive and continuous vigilance” (ibid, p. 315). Thus, despite the benefits that are usually announced when a workshop is offered, the authors have found that they can also act to effect control over the subjects, and they conclude by arguing that “the workshop can be many things but a device disciplinarian whose function is to produce subjects who behave according to what society expects" (Ibid, p. 317).

CONCLUSION

Although we have raised a wide range of works related to the practice of workshops as an educational modality (256 articles), the detailed reading of these texts shows that the definition of the term workshop as a concept in the field of education is far from reaching consensus.

We understand that the difficulty of determining what is a workshop arises precisely from the freedom of creation of its coordinator and the potential for action of those who participate. After all, it becomes emblematic to establish definition criteria for a practice itself, free of standardized settings.

In fact, the only premise for conducting a workshop is to bring together a group of people willing to develop it. In addition, there are no restrictions on location, age, gender, profession, field of knowledge, etc. Evidently, depending on the object to be discussed, there is a tendency to group people interested in the respective theme.

In a simple effort to systematize, we seek to group the workshops into categories: workshops, artistic workshops, didactic workshops, pedagogical workshops, therapeutic workshops and reading and writing workshops. As we reiterated earlier, certain workshops may contain elements that indicate more than one category, but, according to their objectives and modes of implementation, we chose to fit them into the category that stood out. Opting for direct citation of articles, rather than a more explanatory description on our part, is justified since we understand that it emphasizes the authors' arguments and illustrates their views on workshop planning, organization and execution.

We realize that the workshops operate in a more structured way in the Health field. Many of the analyzed articles were conducted in hospitals, clinics and, in particular, in Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS). Although we are not qualified to point out the appropriate reasons, since our view is focused on the field of Education, the reading of the respective articles suggests that the increase in the practice of workshops derives, in part, from the implementation of the Unified Health System (SUS) and the achievements of the anti-asylum struggle movement.

In the field of Education, we see from this review the possibility of workshops as effective spaces for knowledge production, because it is clear from the analyzed articles that the educational moments derived from these practices are conceptualized in the triangle “encounter, event, experience”. That is, an innovative education that goes beyond the mere transmission of knowledge which and seeks, through experimentation, to bring participants to the center of the proposition: beyond the issue of protagonism, to make them co-responsible for educational action.

In addition to this idea of education by the community, we argue for ways of doing that involve almost equal positions of power (and, consequently, emancipation) between the coordinating workshoppers and the performinh participants, combining spaces of freedom of creation and autonomy of execution, whence the multiplicity of objectives, achievements, perspectives, etc.

REFERENCES

ABÍLIO, F. J. P.; FLORENTINO, H. S.; RUFFO, T. L. M. Educação Ambiental no Bioma Caatinga: formação continuada de professores de escolas públicas de São João do Cariri, Paraíba. Pesquisa em Educação Ambiental, [S.l.], v. 5, n. 1, p. 171-193, jul. 2012. [ Links ]

BARROS, F. B. B. Abram as portas. Precisamos entrar... Cadernos de Educação. Pelotas, n. 33, p. 301-309, maio/ago. 2009. [ Links ]

BENITES, S. A. L. Abordagem do texto jornalístico na escola: uma proposta de oficina. Acta Scientiarum: Human and Social Sciences, Maringá, v. 23, n. 1, p. 33-42, 2001. [ Links ]

BOECHAT, M.; KASTRUP, V. A experiência com a Literatura numa instituição prisional. Psicologia em Revista, [S.l.], v. 15, n. 3, p. 22-40, mar. 2010. [ Links ]

BORGES, S. A função da escrita na psicose. Estilos da Clínica, Brasil, v. 13, n. 25, p. 52-63, dec. 2008. ISSN 1981-1624. [ Links ]

CAMATTA, M. W.; NASI, C.; ADAMOLI, A. N.; KANTORSKI, L. P.; SCHNEIDER, J. F. Avaliação de um centro de atenção psicossocial: o olhar da família. Ciênc. saúde coletiva[online], v. 16, n. 11, pp. 4405-4414, nov. 2011. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, R. T. O.; MIRANDA, L.; GAMA, C. A. P.; FERRER, A. L.; DIAZ, A. R.; GONÇALVEZ, L.; TRAPÉ, T. L. Oficinas de construção de indicadores e dispositivos de avaliação: uma nova técnica de consenso. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, Rio de Janeiro, v. 10, n. 1, p. 221-241, jan./abr. 2010. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, I.; PEREIRA, L. A. A relação dos adolescentes com a escrita extracurricular e escolar - inclusão e exclusão por via da escrita. Trab. linguist. apl.[online], v. 54, n. 1, pp. 79-107, 2015. [ Links ]

CEDRAZ, A.; DIMENSTEIN, M. Oficinas terapêuticas no cenário da Reforma Psiquiátrica: modalidades desinstitucionalizantes ou não? Revista Mal-Estar e Subjetividade[online], v. 5, n. 2, p. 300-327, set. 2005. [ Links ]

COSTA, A. M.; CADORE, C.; LEWIS, M. S. R.; PERRONE, C. M. Oficina Terapêutica de contos infantis CAPSi: relato de uma experiência. Barbarói, Santa Cruz do Sul, n. 38, p. 235-249, jan./jun. 2013. [ Links ]

FONSECA, J.; CARVALHO, C.; CONBOY, J.; SALEMA, H.; VALENTE, M. O. Feedback na prática letiva: uma oficina de formação de professores. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, Minho, v. 28, n. 1, pp. 171-199, 2015. [ Links ]

GATTI, A. L.; WITTER, C.; GIL, C. A.; VITORINO, S. S. Pesquisa qualitativa: grupo focal e intervenções psicológicas com idosos. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão[online], v. 35, n. 1, p. 20-39, 2015. [ Links ]

GHIRARDI, A. C. A. M.; FERREIRA, L. P. Oficinas de voz: reflexão sobre a prática fonoaudiológica. Distúrbios da Comunicação, São Paulo, v. 22, n. 2, p. 169-175, ago. 2010. [ Links ]

GIASSI, M. G. Educar para um ambiente melhor. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 15, n. 27, p. 147-158, jan./jun. 1997. [ Links ]

GIRARDELLO, G. Horizontes da autoria infantil: as narrativas das crianças na educação e na cultura. Boitatá, Londrina, n. 20, p. 14-27, jul./dez. 2015. [ Links ]

LANGE, M. B. Caminhares: fragmentos sobre oficinas de escrita e interrogações sobre os ensinares e os aprenderes. Conjectura: Filosofia e Educação, Caxias do Sul, v. 15, n. 3, p. 165-174, 2010. [ Links ]

LEAL, B. Oficina. Revista Sul-Americana de Filosofia e Educação - RESAFE[online], n. 6/7, p. 69-75, maio2006/abr. 2007. [ Links ]

LEANDRO, A. Lições de roteiro, por JLG. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 24, n. 83, p. 681-701, ago. 2003. [ Links ]

LIMA, A. F. Dependência de drogas e psicologia social: um estudo sobre o sentido das oficinas terapêuticas e o uso de drogas a partir da teoria de identidade. Psicologia & Sociedade, Psicol. Soc. [online], v. 20, n. 1, pp. 91-101, 2008. [ Links ]

MENDONÇA, T. C. As oficinas na saúde mental: relato de uma experiência na internação. Psicol. cienc. prof. [online], v. 25, n. 4, pp. 626-635, 2005. [ Links ]

MENEGHEL, S. N.; BARBIANI, R.; BRENER, C.; TEIXEIRA, G.; STTEFEN, H.; SILVA, L. B.; ROSA, M. D.; BALLE, R.; BRITO, S. G. R.; RAMÃO, S. Cotidiano ritualizado: grupos de mulheres no enfrentamento à violência de gênero. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, Rio de Janeiro, v. 10, n. 1, p. 111-118, 2005. [ Links ]

MENEZES, M. P.; TEIXEIRA, I.; YASUI, S. O olhar fotográfico como proposta de cuidado em saúde mental. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, Rio de Janeiro, v. 60, n. 3, p. 23-31, 2008. [ Links ]

MORAES, S. P. G.; ARRAIS, L. F. L.; GOMES, T. G.; GRACILIANO, E. C.; VIGNOTO, J. Pressupostos teórico-metodológicos para formação docente na perspectiva da teoria histórico-cultural. Revista Eletrônica de Educação, São Carlos, v. 6, n. 2, p. 138-155, nov. 2012. [ Links ]

MORETTI, V. D. A articulação entre a formação inicial e continuidade de professores que ensinam matemática: o caso da Residência Pedagógica da Unifesp. Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 34, n. 3, p. 385-390, set./dez. 2011. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, T. R. M. Encontros possíveis: experiências com jogos teatrais no ensino de Ciências. Ciência & Educação, Bauru, v. 18, n. 3, p. 559-573, 2012. [ Links ]

ORMEZZANO, G. A linguagem visual na educação especial. Revista Educação Especial, Santa Maria, n. 28, p. 275-286, 2006. [ Links ]

PACHECO, A. B.; BARROS, M. E. B.; SILVA, C. O. Trabalhar o mármore e o granito: entre cores e ritmos.Cadernos de Psicologia Social do Trabalho, São Paulo, v. 15, n. 2, p. 255-270, dez. 2012. [ Links ]

PAVIANI, N. M. S.; FONTANA, N. M. Oficinas pedagógicas: relato de uma experiência. Conjectura: Filosofia e Educação, Caxias do Sul, v. 14, n. 2, p. 77-88, maio/ago. 2009. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, A. C.; CESARINI, M. M.; BILBAO, G. Oficina de criatividade com pais de crianças deficientes. Revista da Abordagem Gestáltica [online], v. 15, n. 2, p. 169-178, jul./dez. 2009. [ Links ]

PEY, M. O. Oficina como modalidade educativa. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 15, n. 27, p. 35-63, jan./jun. 1997. [ Links ]

POLI, I. S. Oriki em salas de aula da cidade de São Paulo. Acolhendo a Alfabetização nos Países de Língua Portuguesa, São Paulo, v. 3, n. 6, p. 224-229, ago. 2009. ISSN 1980-7686. [ Links ]

PREVE, A. M. H. A oficina de sexualidade como busca por uma prática convivencial. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 15, n. 27, p. 159-174, jan. 1997. ISSN 2175-795X. [ Links ]

REIS, G. H.; BRANDELERO, F.; CARNIATTO, I.; PEREIRA, L. S. REA-PR tecendo sonhos: enlaçando a governância das universidades em redes na Rio+20 - rumo as comunidades sustentáveis. REMEA - Revista Eletrônica do Mestrado em Educação Ambiental, Rio Grande: FURG, [S1], p. 363-382, maio 2014. [ Links ]

RINALDI, E.; GUERRA, A. História da ciência e o uso da instrumentação: construção de um transmissor de voz como estratégia de ensino. Caderno Brasileiro de Ensino de Física, Florianópolis, v. 28, n. 3, p. 653-675, jan. 2011. ISSN 2175-7941. [ Links ]

TURRA-MAGNI, C. Nova pobreza e paradoxos da política de inclusão social francesa: considerações a partir de uma oficina cerâmica no Socorro Católico. Antropolítica, Niterói, n. 29, p. 55-77, 2010. [ Links ]

SILVA, G. S.; BRAIBANTE, M. E. F.; BRAIBANTE, H. T. S.; PAZINATO, M. S.; TREVISAN, M. C. Oficina temática: uma proposta metodológica para o ensino do modelo atômico de Bohr. Ciênc. educ., Bauru[online], v. 20, n. 2, pp. 481-495, 2014. [ Links ]

Received: January 12, 2019; Accepted: August 19, 2019

texto en

texto en