Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 10-Mar-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698231575

ARTICLE

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION AND THE WORK WORLD AS PERCEIVED BY MIDDLE-LEVEL TECHNICAL COURSE STUDENTS1

1 Professor at the Faculty of Education and the Graduate Program at Universidade Federal of Rio de Janeiro. Researcher at the Marxism and Education Studies Group (COLEMARX). Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. <brunogawry@gmail.com>

This text synthesizes part of a field research that addresses the motivations, perceptions and expectations of middle-level technical courses students inquired about the professional training process and the situation of the work world. First, the article contextualizes the policies directed to Professional Education, in order to understand how this teaching modality has been expanded since the early 21st century, and how transformations have taken place in the current scenario of the work world. Next, the research results are presented, with a view to characterizing the participating subjects and their considerations about the field of work and education analysis. The interpretation of students' speeches was insightful into how aspects of human subjectivity are dimensions developed through social relations and these material expressions represent the subjects' form of involvement with the world and how they project their future possibilities. At last, final considerations are made as a synthesis of the text.

Keywords: Students; Technical Professional Education of Middle Level; Work and Education

O presente texto sintetiza parte de uma pesquisa de campo que aborda as motivações, percepções e expectativas de estudantes de cursos técnicos de nível médio em questionamento sobre o processo de formação profissional e a conjuntura do mundo do trabalho. Inicialmente, o artigo contextualiza as políticas direcionadas à Educação Profissional, de modo a perceber como essa modalidade de ensino tem sido expandida desde o início do século XXI, e como tem se dado as transformações no atual cenário do mundo do trabalho. A seguir, são apresentados os resultados da pesquisa, tendo em vista a caracterização dos sujeitos participantes e suas considerações acerca do campo de análise de trabalho e educação. A interpretação das falas dos estudantes foi reveladora sobre como aspectos da subjetividade humana são dimensões desenvolvidas através das relações sociais e que essas expressões materiais representam a forma de envolvimento dos sujeitos com o mundo e como projetam suas possibilidades futuras. Por fim, são tecidas as considerações finais como síntese do texto.

Palavras-chave: Estudantes; Educação Profissional Técnica de Nível Médio; Trabalho e Educação

Este texto resume parte de una investigación de campo que aborda las motivaciones, percepciones y expectativas de los estudiantes técnicos de secundaria en cuestión sobre el proceso de formación profesional y la coyuntura del mundo del trabajo. Inicialmente, el artículo contextualiza las políticas dirigidas a la Educación Vocacional, con el fin de comprender cómo esta modalidad de enseñanza se ha ampliado desde principios del siglo XXI y cómo ha ido cambiando en el escenario actual del mundo del trabajo. A continuación, se presentan los resultados de la investigación, considerando la caracterización de los sujetos participantes y sus consideraciones sobre el campo del análisis del trabajo y la educación. La interpretación de las declaraciones de los estudiantes fue reveladora sobre cómo los aspectos de la subjetividad humana son dimensiones desarrolladas a través de las relaciones sociales y que estas expresiones materiales representan la participación de los sujetos en el mundo y cómo proyectan sus posibilidades futuras. Finalmente, las observaciones finales se hacen como una síntesis del texto

Palabras clave: Estudiantes; Formación técnica de grado médio; Trabajo y Educación

INTRODUCTION

Middle-Level Technical Professional Education (EPTNM) in Brazil is crossed by a historical dispute in the educational field, regarding its dualistic formative and systemic structure. In the analytical axis that deals with discussions in the field of Work and Education, polytechnic education and unitary school are at the base of the problematizations against dual school, when considering the centrality of the work category and its historicity in the capitalist production mode and for understanding education as a historically constituent of human formation, see the legacy of the Working Group representative of that field in ANPEd. The affiliation of the text with the field of Work and Education problematizes the ideological cement promoted by the economic conception of education, its contradictions and mediations posed by educational policy guidelines, and in view of the objective conditions of Brazilian social formation and the current political and economic context that established significant changes in the work world (ANTUNES, 2018; ALVES, 2013). Furthermore, it conceives the contradictory character of EPTNM in view of determinations that imply duality of the educational system and the formation of the Brazilian workforce, mostly focused on simple labor.

From the perspective of the ruling class, on which the economic conception of education (human capital) is based, EPTNM is lifted to a condition of redemption of Brazilian ailments, as it is supported by assumptions that bring “unappealable” evidence that EPTNM is able to leverage the country's economic and social development, since it would “naturally” generate greater productivity for the economic sectors and a faster and more compensatory financial return rate for those who are willing to obtain such training.

In this regressive framework, it is understood that the premise (and the promise) that underlies the economic conception of education - which establishes a causal relationship between extended schooling years with improvement in income and work conditions for the working class and the country's economic social development - is not confirmed in the face of concrete reality. This premise proves to be wrong because this conception tries to explain the economic base through processes that touch it, such as education, for example. In this way, education becomes a determining pole to explain why the country does not reach a certain level of economic development. In our view, this is an inversion that seeks to justify that the deleterious effects of poor development are explained by insufficient or inadequate qualification of the workforce and not that the processes of exclusion and inclusion of workers in the market are organically linked to the process of production and reproduction of capital from certain historical circumstances, as will be shown in the next section.

Other determinations are brought about by the contradictions of the current historical situation. Within the scope of public education policies, since the 1990s, the expansion of schooling in the Brazilian population and the broader access of the popular strata at all levels of schooling are well known. However, this process has been taking place at a juncture that affects material expressions in work relations through precariousness, fragmentation, informality and uncertainties and that have been affecting young workers in particular.

In Brazil, EPTNM in the integrated modality (an explanation of the modalities will appear later) is predominantly offered in public schools. It is a formative conception that has been quite successful in the processes of large-scale assessment and entrance into higher education, especially in federal institutions. Although the public that occupies the vacancies of these institutions is not exclusively from the most impoverished strata of the working class and do not necessarily want to obtain technical qualifications to work in their area of training, it is necessary to consider that there is a significant contingent of the working class that aspires a most immediate entrance into the labor market and which yearns for better job positions, in view of the specialized qualification in a given economic activity. In this perspective, EPTNM establishes a crossroads for these students, because, at the same time that this technical training involves the pressing need for entering the labor market, depending on material and subjective conditions, professional insertion can delay and even suppress the yearning to enter higher education.

Therefore, the central question posed within the scope of this article is to understand how students in the process of professional training are realizing their future possibilities of entering the labor market, especially by identifying elements that influence their formative choice and, consequently, their school trajectory. To this end, the text is organized as follows: I) it presents an overview of policies concerning professional education and the work world; II) a report of the results of the field research aimed at understanding the motivations, perceptions and expectations of EPTNM students about professional training and entry into the work world; and III) final considerations.

As a support for the analysis of students' motivations, perceptions and expectations, the contributions of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and Pierre Bourdieu (each in their own way) were used as interlocutors that individuals’ consciousness is strongly influenced by material relations of production and the place individuals occupy in it. It should be added that the results of other researchers with similar investigations in the field of Work and Education and Sociology of Education were compared for interpreting the present authored research.

OVERVIEW OF POLICIES ON PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION AND THE WORK WORLD IN BRAZIL: OBVIOUS CONTRADICTIONS

It is understood as clarifying that the reference to Professional Education refers to chapter III of the Guidelines and Bases of National Education Law No. 9.394/1996 (BRASIL, 1996), originally called “Of Professional Education” and later significantly changed on account of Law No. 11.741/2008 (BRASIL, 2008), which gave a new dimension to the educational modality, including changing the title of the chapter to “On Professional and Technological Education”. Basically, the LDB chapter comprises articles 39 to 42 and covers different levels and modalities of professional and technological education3. Its structure includes courses at three levels of complexity: initial and continuing education, generally linked to professional qualification courses; Middle-Level Technical Education; and undergraduate and graduate professional technological education. Such levels of complexity in the studies won these nomenclatures in Decree nº 5.154/2004 (BRASIL, 2004), as will be described below.

Undergraduate and graduate Professional Technological Education is offered only to those who have completed high school and have rules that regulate their workload, objectives and other specificities, based on the sectors and areas of economic activity. Initial and continuing education, on the other hand, is offered in conjunction with the education of young people and adults and aims to increase worker qualification, although its certification does not confer a degree that allows to ascend in regular schooling. Such a prerogative makes initial and continuing education free from curriculum regulation because it is a non-formal educational modality (CARNEIRO, 2015).

Middle-Level Technical Professional Education (EPTNM), which this article deals with, can be offered in three ways: integrated, concurrent and subsequent. The first covers those students who have the same enrollment in the same institution, both in high school and professional training with integrated curriculum. The second form deals with that student who attends both levels of education at the same time, in different institutions or in the same institution, but with different enrollment, without course integration. The third concerns students who are taking Professional Education but have already finished high school.

EPTNM data shows that between 2002 and 2018, the number of enrollments more than tripled. The School Census of 2002, the last year of the then president Fernando Henrique Cardoso's term, the technical middle-level courses reached 565,042 enrollments. In 2007, the beginning of Lula da Silva's second term in the Presidency, there were 682,431 enrollments. The 2018 data, on the other hand, show that there are 1,868,817 enrollments in Brazil (INEP, 2003; INEP, 2008; INEP, 2019), which means that around 10.6% of high school students in Brazil are enrolled in some technical course in professional education4.

Due to the relative quantity that is considered very low by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (according to the OECD report, the countries that make up the Organization have an average of 44% of secondary education), since the 2000s, the federal government has launched initiatives aimed at expanding EPTNM. In the motto of the launch in 2007 of the Education Development Plan (PDE), which advocated joint initiatives between federal entities, the Public Call MEC/SETEC n. 002/2007 welcomed proposals to support the implementation of new federal institutions of Professional and Technological Education, through a partnership between MEC and municipal managers. In this way, municipalities would receive a teaching unit and should provide physical space for the construction of the school and other actions that would make its implementation feasible, justified by an investment strategy that combined education, economic development and territoriality. Also in the context of the PDE inception, the Brasil Profissionalizado program was launched, with a view to stimulating secondary education integrated with Professional Education in state education networks, through the provision of resources for the expansion of their own network (CAIRES and OLIVEIRA, 2016).

The following year, through Law 11,892/2008, the Federal Network for Professional, Scientific and Technological Education was established, which resulted in the creation of 38 Federal Institutes of Education, Science and Technology from the merger of the Federal Technological Education Centers (CEFETs), federal agrotechnical schools, and technical schools linked to federal universities. From the construction of 150 schools foreseen in the MEC/SETEC Call plus 208 technical schools by the end of the 2011-2014 period, a total of 562 campuses in Brazil were intended to be reached, numbers that are uncertain to be obtained. However, it is certain that the budget for Professional and Technological Education was increased from R$2.2 billion in 2003 to R$9 billion in 2013 (SANTOS and RODRIGUES, 2015), which denoted the prioritization of investment for this modality of education.

Despite the significant growth in the 16-year period, it is registered that the peak of enrollments at EPTNM in Brazil was 2014, with 1,886,167 enrollments, that is, precisely the end of the investment period of expansion of the Federal Network. That year, the National Education Plan (PNE 2014-2024) was enacted, which stipulated goal 11, a specific goal for the number of EPTNM enrollments to be tripled by the end of the decade and that at least 50% (fifty percent) of the expansion to be offered in the public segment (BRASIL, 2014). This goal considers the role of the Federal Institutes and in the state public education networks as strategic, although it also matches the forecast for expansion of EPTNM through private entities of Sistema S. Therefore, in absolute numbers, this goal implies that, in 2024, the Brazilian educational system will reach almost five million enrollments, in view of the 1,666,138 enrollments in 2013, the reference year for the current PNE. Judging by the number of enrollments since PNE was in force, the envisaged expansion does not indicate that it will be achieved5.

It is important to contextualize that such political orientations took place in a context in which Brazil had reached a higher level of economic growth, with the creation of new jobs and greater formalization in the employment relationship, which, consequently, generated a growing clamor that Professional Education should be further expanded to support a virtuous cycle. In this sense, the predominant discursive framework was that, on the one hand, technical courses would meet the aspirations of the working class children, especially from the lower classes, to have access to more qualified training and to put them in better conditions to sell their workforce. On the other hand, it would also meet the demands of the business community, which propagated the discourse that a “blackout of labor” was occurring in Brazil, which, from the point of view of the companies, would have created difficulties to hire a qualified workforce to take the available positions.

In this context, at the initiative of the federal government, Law No. 12,513/2011 instituted Pronatec (National Program for Access to Technical Education and Employment) as an attempt to consolidate the expansion of the Network itself. Other initiatives were also part of this policy, such as offering scholarships to students and workers (Bolsa Formação), financing for private educational entities (Fies Técnico/Fies Empresa), free agreement with Sistema S, support for expansion of state networks of professional education and distance learning (e-Tec), all of them coordinated by the Ministry of Education Secretariat of Professional and Technological Education (CASSIOLATO and GARCIA, 2014).

Pronatec, despite predicting an increase in the expansion of the Federal Network itself, prioritized the provision of scholarships for students and workers in private educational institutions. Between 2011 and 2014, Pronatec reached eight million enrollments, under the condition that 92% of the resources used in the budgetary action 20RW (support for professional, scientific and technological training) were allocated to Sistema S6, which totaled an amount of R$5.88 billion for this business organization (COSTA, 2015), a finding reiterated by Motta and Frigotto (2017), who reached similar numbers. Another assertion regarding the program was that, between 2011 and 2014, Pronatec, when reaching the initially set goal of 8 million enrollments, did so with the proportion of 2.3 million (28%) in EPTNM courses (minimum of 800 hours) and 5.8 million (72%) in Initial and Continuing Training courses (FIC - on average, 160-hour courses). These data show the fragility of the discourse that presupposes a causal link between education and economic development, since most of the enrollments in the Program were destined to quick and simple training courses, with low added value.

Under the presidential term of Michel Temer, as of May 2016, the federal government announced two measures to restructure Pronatec: the Progredir plan, which consisted of offering 160-hour professional qualification distance courses, under the pretext of quick insertion in the job market and opening one’s own business; and the creation of MedioTec, as a supplementary action to the aforementioned program, where an amount would be passed on to educational institutions to cover the costs of student training at EPTNM. The target audience was aimed at the population considered “socially vulnerable” and beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família program. In both cases, it is possible to affirm that the programs had an irrelevant impact, especially as compared to the actions carried out by the PT and Lula governments.

Finally, in relation to the initiatives related to EPTNM, but no less important at the national level, the enactment of Law 13,415/2017, which instituted a reform in High School. This established a proposal for the reorganization of this education stage, in which a limit of 1,800 hours common to the curriculum content is defined (maximum 60% of the workload for a minimum total of 3,000 hours), and, later, students must opt for available training itineraries, one of which is technical and professional training. This reform in the organization and rationale for high school is still moving towards issuing greater regulations and definitions on its implementation, so it will not be further elaborated in this article. However, I consider it important to point out that this reform brings out the claim of the ruling class to form suitable workers to the current conditions of the labor market - characterized by insecurity and intensification of exploration of the workforce - in order to develop life skills in young people, especially to make “good decisions” about their life project in a world marked by instabilities and uncertainties (MOTTA; LEHER; GAWRYSZEWSKI, 2018). It is a formative proposal that departs from all the historical accumulation built by the ANPEd Work and Education WG in favor of high school integrated with professional training, whose main proposition is curricular integration around the science, culture, work and technology axis, which is based on the educational principle of work.

It can be said that actions aimed at EPTNM induce, albeit briefly, a reflection on contemporary production processes. As demonstrated, there has been a significant expansion of EPTNM in the last 15 years, in which such expansion was justified to meet a supposed businessmen’ need to build stocks of more qualified workforce in order to increase the productivity potential of companies. However, although schooling at secondary and higher levels had a relative growth in the first decade of the 21st century, Deitos and Lara (2016, p. 177) consider that “contradictorily, the production process requires qualification levels per occupation that, relatively, move in disagreement with the education levels required by the economic sectors”. The data compiled by the authors referring to the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD) between 2002 and 2011 revealed that the requirements for occupation by level of schooling changed little, with low and medium level of qualification (79%) predominating. The synthesis of the data presented by the authors above provides elements to conclude that there is a mismatch between the business community discourse about the “blackout of qualified labor” and the actual options for hiring and/or occupying Brazilian workers by the business community. This conclusion may explain that the greater emphasis on the provision of FIC courses from Pronatec may be related both to the raising of public funds provided by the institutions of Sistema S and to the actual demand for workforce in Brazil.

It is important to pay attention to the fact that in the current political-economic situation, of flexible accumulation under the aegis of neoliberalism, the productive structure was changed, becoming more flexible, with reduced jobs and, as a result, the precariousness of work was intensified. As shown by the research by Alves (2013) and Antunes (2018), among others, combined elements of the Fordist organization pattern and flexible accumulation, production on demand in lean companies, wages linked to productivity and the intensification of new technologies have potentiated processes of deterioration in work relationships. In this sense, the intensification of competitiveness in the international market has permanently placed the agenda of Labor Reform on the part of the business community, in order to further reduce the costs of the workforce; which leads to more loss of labor rights. The very president Jair Bolsonaro, commenting that in the face of so many rights provided to the worker, “[...] entrepreneurs hire as little as possible and pay as little as possible”, and so workers should opt for “fewer rights and more employment or all rights and unemployment” (BOLSONARO, 2019), sets the tone for what would be the engine of the growth of Brazilian capitalism: the expropriation of rights and overexploitation of the workforce. Fontes (2010) understands that the current expression of expropriation of rights is part of a historical process in which new ways of extracting more value will be introduced through the capture of resources of wage origin, in order to transform them into capital.

It is not by chance that there has been a systematic investment in the propagation of reports and interviews with “experts” in the mainstream media to justify the reforms, in addition to the dissemination of materials through social networks (even appealing to facts and arguments that violate any principle of rationality) and the holding of academic events and editorial publications that have very well-defined purposes. It can be said that this is a movement that combines speeches with a character of coercive persuasion (“there will be no money to pay for the retirement of the next generations”) and consented coercion (“inevitably more deaths will occur”), in order to legitimize to workers government actions against the workers themselves (coercion achieved). To this movement, Fontes (2010, p.55) understands that:

It was about introducing a new “normality”: to segment each situation or right that became a priority target and to dwell on it exhaustively, by all media means. The international plan was always presented as a model, both for the best (the good example) and for the worst (the tragedy).

For this reason, the Labor Reform agenda, in the quest to “modernize and flexibilize” the relations between bosses and employees, often refers to examples of the countries of central capitalism that have already approved legislative changes in this regard (especially, in this case, European countries) or that no longer had broad social protection and combativeness on the part of the unions (cases of the United States, China, Japan and Asian countries in general). The promise, therefore, is that, by following the same path (in spite of disregarding historical and social contexts), Brazil would be able to leverage economic growth and resume hiring workers. Under this justification, in 2017, two laws that made up the labor agenda were approved: Law No. 13,429/2017, known as the Outsourcing Law; and law No. 13,467/2017, referred to as Labor Reform. Briefly, the former allows the universalization of outsourcing, previously restricted only to occupations considered as a means and not as the end of the activity of a certain company (for example, a teacher in relation to a school); the latter is more comprehensive and modifies several provisions provided for by the Consolidation of Labor Laws, but which can be summarized on the premise that individual or collective agreements can prevail over the content provided by law, therefore, qualification as flexible. Although it is not our aim here to examine the content of the aforementioned legislation, the fundamental thing to note is that they express the dominant class’ worldview, even though through direct representatives or disseminated as common sense by the working class, the most vulnerable one to the effects of the new “morphology of work in Brazil” (ANTUNES, 2018).

The consequence of the process of deterioration of work relations in Brazil, in addition to not producing the results promised by the labor reform actions, has greatly affected young people. The PNAD/IBGE of the second quarter of 2019 found that the unemployment rate of the population between 18 and 24 years old is 25.8%, that is, more than double the 12% of the total average (IBGE, 2019), a level that has remained above 25% for at least four years.

The growing number of young people who are not in a situation of work occupation, added to those who, due to discouragement, do not even look for work and also interrupt their studies, has been classified as young people neither-nor, since they would be in a condition of indeterminacy about their own lives, since they would be simultaneously outside the education system and any guarantee of formality in the work market. For many of these young people (although also mature and elderly adults) the alternative that has been presented as an immediate option is occupations linked to services by applications. There is still no list of consistent academic research on this very recent working condition, but it is estimated that around four million people have been dedicated to services by applications. In general, companies that provide services through applications present themselves as intermediaries between consumers and suppliers through self-employed workers who freely associate with the company, accepting the conditions of digital platforms. This new stage of labor relations has been given the name of “uberization of work”, as it deepens the model of outsourcing and subcontracting, as the worker becomes a kind of “permanent nano-entrepreneur-of-himself available for work.” (ABÍLIO, 2017, n/p).

Therefore, in the face of a not very promising scenario in the work world, but of expanding possibilities through schooling (although it has been demonstrated that the government does not necessarily prioritize a more robust level of training), the aim of the next section is to understand how EPTNM students base their motivations, perceptions and expectations about their possible inclusion in the work world and the professional training received through the technical course.

MOTIVATIONS, PERCEPTIONS AND EXPECTATIONS OF EPTNM STUDENTS

After outlining the profile of EPTNM in Brazil and the public policies carried out and underway in the last 20 years, as well as analyzing the determinations and contradictions posed by the political situation in the work world, in this section I will describe EPTNM students’ motivations, as well as how they are perceiving their professional training process and building future expectations, by conducting field research. Accordingly, the current section is organized in order to: I) describe methodological procedures; II) identify participants; III) report research results through focus groups.

Methodological procedures

The field research was carried out between the second semester of 2017 and the first semester of 2018. In total, seven middle-level technical courses were visited, all maintained by public education institutions, two of which linked to the state government sphere and the others, the federal sphere. Six of the courses belonged to the integrated modality, and one, in the night shift, to the subsequent modality. It is emphasized that, because the research involved direct interaction with human beings, the project was submitted and approved by a research ethics committee at Plataforma Brasil through (opinion number 2,224,740), in June 2017. As agreed with the interviewed subjects, all participants and their respective institutions will be kept anonymous, since this identification does not lead to qualitative gains for the development of the research.

At the end of all visits, 115 students were directly contacted. The selection criterion for participation in the study was having completed at least 50% of the respective course, so as to be in a more favorable condition to judge the training received in the educational institution, and some of them had already participated or were participating of internships in companies. First, these students were asked to answer a questionnaire that characterized their socioeconomic and family profile and about the motivations, perceptions and expectations about aspects related to both the work world and professional training, the heart of this text. Some of those who signaled positively in the questionnaire were invited to participate in a group session, through the research technique called focus group, which was carried out in only four of the seven courses, either because of students’ lack of interest or impracticability of the procedure due to academic calendar constraints.

The focus group technique involves organizing a discussion group to discuss a particular topic after receiving relevant stimuli for this purpose. A process of interaction within the group on a subject of common interest is expected from the participants. As the dynamics unfolds, there is an opportunity to expose and confront beliefs, values and knowledge. For this, the researcher in question performs an action to make the researched object knowable along the dynamics, regardless of his own belief, which implies that the purpose in the focus group is, according to Gomes (2005, p. 279) “ [...] extract from the attitudes and responses of the group participants feelings, opinions and reactions that would result in new knowledge”.

In the case of the present study, the group sessions took place in the respective educational institutions, and the responsible researcher and one or two assistant researchers attended the four sessions held. After the interviews were carried out and transcribed, an analysis was carried out to identify trends and relationships in the responses. For each answer, the topics and keywords most mentioned by the interviewees were organized, which allowed grouping these speech fragments and then determine relationships between the topics covered and build an interpretation regarding the purpose of the research.

Identification of subjects

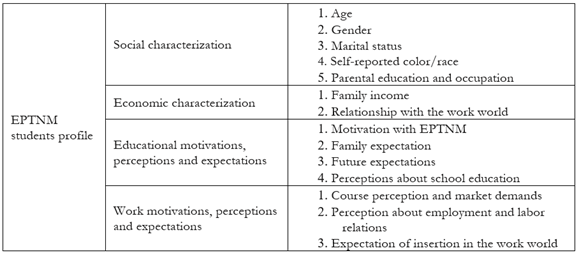

As explained in the previous section, 115 EPTNM students were contacted, who initially answered a two-page questionnaire. The first page was structured around a questionnaire that characterized the socioeconomic and family profile. The next page contained questions about understanding the motivations, perceptions and expectations of EPTNM students about aspects related to the work world and professional training. The structure of the questionnaire is summarized in the Box below:

For the purposes of exposure in this text, socioeconomic and family characterization will be based on the questionnaires, and motivations, perceptions and educational and work expectations will be based on the contents of focus groups, since they could be further developed in this dynamic.

The specific survey carried out for this research indicated that 68 (59%) respondents identified themselves as male. Two thirds of the respondents were aged between 16 and 18, which seems to explain that 107 self-reported as single, 108 did not have children, and 105 live with relatives.

Regarding skin color/race, 50 (43.5%) respondents self-reported as White, 26 (22.6%) as Brown, and 29 (25.2%) as Black. In this case, the number of people who identify themselves as Black is much higher than the Professional Education universe measured by the School Census in the state of Rio de Janeiro, which indicates around 6% - just over 10,000 students of the total universe of 170,870 - self-reporting as such (INEP, 2019). As this is not an immediate research objective, this finding will not be explored, but I do indicate the relevance of understanding the factors that may influence the result in these EPTNM schools belonging to the state and federal education network.

Regarding parental schooling, occupation and income, although such questions were answered, the process of evaluating the answers lead to the conclusion that the layout and formatting of the questionnaire did not favor the safe and reliable provision of answers by the students regarding these items, especially because it refers to people other than the respondents themselves and to questions that the public does not always feel comfortable answering, such as the family income issue. On this account, it was decided to discard the reporting of these data, even though such data, it should be noted, were not ignored at the time of the survey.

When asked to answer about their relationship with the world of work, 62 respondents replied they did not have any work experience, but 45, i.e., almost half of the research universe, had or at some point had an occupation, although, at the time of the survey, only 26 declared they were currently exercising any work activity. The occupations most cited by students were trainees (9) and equal numbers (9) of TAs and scholarship holders. This is possibly due to the characteristics of the researched educational institutions, which provide this type of academic and professional training to their students. Of those who reported experience with the work world, 19 started their activities before the age of 18, but as highlighted above, a significant portion in jobs related to their own professional training, although a small sample declared having had low-skilled occupations, such as motorcycle courier, painter and telemarketer. In this sense, this finding differs, for example, from the research by Marcassa and Conde (2017), who investigated young students, mostly from high school, in a poor social territory in Florianópolis. The researchers showed that, for their interlocutors, work was a reality for almost 70% of them, a third started working before the age of 16 and their occupations are predominantly informal or in such low-skilled jobs as car washer, assistants for general services, clerks, waiters or delivery men for bars and restaurants and telemarketers on working loads that sometimes exceed forty hours a week.

Focus groups

From here, issues related to motivations, perceptions and educational and work expectations of EPTNM students will be explored. The sessions held had a previously thought-out script, but due to interviewees' manifestation, the order and emphasis for each theme followed the flow of the discussion itself. However, in all sessions the debate started with the question about motivation and factors that led them to choose the respective courses. Certainly, in addition to some degree of identification with the course, other factors were much more emphasized than personal taste, such as influence and/or imposition by parents.

Since my childhood, my mother has had a lot of guidance, you know, in the choices I make related to everything in life, it was no different with the issue of schooling and studying. I was always pretty guided and everything, as I grew up and saw the importance of everything, I started talking to her about the career issue [...] My mother, she was an electronics technician and that would be my choice, but I studied the area a little and realized I was not quite into it, it was not something that delighted me and I would end up doing it just because she did. Then I got my act together and I decided to go into Buildings (School A student).

I chose it because my father said that I had to take a technical course for securing a job when I graduated from high school (School C student).

I chose by indication. I have a family member who takes the course and liked it, so I decided to take it (School C student).

From the statements it is possible to see that family has a significant weight in mobilizing young people to choose a public technical education institution to attend high school. This family school mobilization is understood by Nogueira, Resende and Viana (2015, p. 763), in a sociological perspective, as “[...] a set of practices and attitudes aimed at the successful schooling of children”. Families concern in choosing a “good school” for their children to attend high school, therefore, may be associated with parents’ or family members’ experiences or knowledge, who see the institution as a “quality reference” to open a wider range of opportunities of both study and work. For this reason, there is a clear link between the institution's reputation and a supposed favorable condition to enjoy better opportunities in the world of work.

The school opens a lot of doors for the middle-level and technical (School C student)

Besides, (name of the institution) has a name, right? You end up studying at a federal college, which has a tradition, which has a reputation, so you already get a differential. [A student interrupts him: The company already looks at you with different eyes. They usually accept it, it's more open to the folks from (name of the institution)] (School C student).

It is then possible to interpret that the influence on students' choice of career by their families, even though it may be related to some extent with their children's “wills and aptitudes”, they take a material form through the experiences acquired from the objective conditions in which individuals find themselves. For this reason, Pierre Bourdieu harshly criticizes the term “parental will” as an explanatory factor in students’ choice of destiny and training, as this term neglects the concrete relationships that give materiality to individuals’ choices.

The attitudes of members of different social classes, parents or children and, in particular, attitudes towards school, school culture and the future offered by schooling are, to a large extent, the expression of the implicit or explicit system of values that they owe to their social position (BOURDIEU, 2015, p. 51).

By segmenting the choices and destinies between social classes, Bourdieu brings to the fore an ascetic ideal of social ascension on the part of middle-class families, who devote every kind of effort and encouragement to obtain their children's school and professional success, whereas the working class, in view of its material deprivations, adjusts its level of aspiration from its possibilities of reward, because of the

[...] interiorization of the destiny objectively determined (and measured in terms of statistical probabilities) for the whole social category to which they belong. This destiny is continually remembered through the direct or mediate experience and the intuitive statistics of the defeats or partial successes of the children in their environment [...] (BOURDIEU, 2015, p.52).

Another notion that was explored with the students was how they perceive the relationship between the training received at the educational institution and adherence to the so-called “demands of the labor market”. The highlighted speeches emphasize that students have a perception that, although they recognize that their respective courses give them a knowledge base, they only partially provide training that can enable them to enter the profession, above all, due to the distance between aspects that simulated professional practice in a more realistic way.

Well aligned, indeed, fully satisfactory (School A student)

I think the course could be updated in terms of both teachers and its register. I think that's what (another student) said, I think it provides a basis, but we get out of here at square one [...] I think things have to keep up with market demands, this issue about sustainable construction and people, the is nothing about it. We don't have any kind of lecture, we don't have any kind of technical visit as she said (School B student).

I think we have a cool base, there are cool things, but some refinement is lacking (School C student)

I already hear from some people that: “Oh, at Senai, mechanical folks are better; here you are better professionals.” Not neglecting a change, the person knows part A or part B, here we know how part A and part B work. (School C student)

I thought I was going to travel [laughs]

I wanted to travel and thought I would have more languages (Two school D students)

When talking about the situation of the work world, students unanimously perceive that they live in a historic time of difficulty getting formal jobs and precarious labor relations. However, their statements reveal heterogeneity as to how to deal with the situation. While the majority points out the difficulty of the current scenario in the world of work, school A student’s perception is that the crisis situation would favor the hiring of technicians, precisely because they are below the social division of labor, which would require less investment with the workforce.

In times of crisis, the employer does not have so many resources, or if he does, he does not want to apply his resources by hiring this type of professional [with a higher education]. He wants someone to meet his particular demand, at a more affordable price and that's what the technician is. The technician is quite equipped for that, about 80% to 90%, at a reduced price (School A student)

Our area is not at its peak. Here, our class, before look for [jobs] at middle-sized workshops, we look for at dealerships, bigger places and we really saw that it is difficult. Sometimes we don't even go through the entrance door (School C student)

Folks are looking for a lot of internship in the maintenance area because it is the one that is hiring the most, but [...] in my opinion, the market is a little complicated (School C student)

Nobody is being successful, then nobody is taking time to travel, then nobody is hiring us (School D student)

The sense of life projection in EPTNM students was also addressed, that is, something that individuals propose to achieve in some dimension of their life. However, considering that the majority of the research universe has adolescents and young adults as interlocutors, such projects are transformed along individuals' own maturation and discovery. Possibly several projects are born, while others die or are put aside in the face of situations of the present time that shape aspirations into levels of concrete possibilities of achievement or not. Fundamentally, it is about a relation of life project and time, especially in relation to the future that becomes the result of a becoming that “[...] appears linked by a double thread, the choices and decisions of the present” (LEÃO; DAYRELL; REIS, 2011, p. 1072). This premise can be perceived, for example, in the research by Correa and Cunha (2018) with high school students in the state education system of Minas Gerais, when, urged to express themselves on how they are challenged to analyze and make decisions that will have any impact on their future, one of the young people said:

[...] what do I want to do? I decided what I do not want to do anymore, but I don't know what I want to do now. And all ENEM preparation starts, from ... looking at the college that will be suitable for me, places that ... will recur, if I am going to a boarding school, if I'm going to keep on going home even at a college with a campus, without a campus, it's... what I'm doing... And if I start working, how am I going to reconcile this and school... then there is a whole preparation that you have to do, but at the same time you... you do not know where to start this. (CORREA; CUNHA, 2018, p. 14-15)

In the authored research carried out in this text, the following students' speeches provided different possibilities and analyses.

I find it difficult to talk about projection, since Brazil is in crisis [...] in the current situation I do not have many expectations, I try to change the direction of my thoughts and focus on other things that may be more interesting (School B student).

I like working in the workshop where I already did an internship and I like it, but I do not want it for life [...] So it's something like that, a technical course in general, it's kind of a limbo between school and college, because a lot that we learn here, we will not learn outside (School C student).

In my case, the technical course as technical is an area that I want to follow, I want to live and work in a workshop, one day I want to have my own workshop (School C student).

I saw the technical [course] as a way to discover me, an opening to something I want later on, I also want to study engineering, like most here, but the specific area of engineering, my Automotive Maintenance course, made me see which area I want to pursue (School C Student).

If I could choose without any concern, the best part would be to become a blogger (School D Student).

As it was possible to verify in students’ speeches, there is no homogeneity in the aspirations of life project, although the relationship with the future time is present. The school B student was the most pessimistic one, as she considered that the country's economic situation would be a factor that would limit her expectations of future projection, shaping her life (at that moment) to a condition of suspension of plans. With regard to school C students, they showed satisfaction with the technical course and the possibility that it offers as a professional horizon. Finally, the school D student, reflecting a certain frustration due to the inability of her course to provide more experiences related to professional training, projects a certain imagery to a reality beyond her own, because, inevitably, it would be at least more pleasurable than the lived one. In this sample of responses, it can be seen that the technical course does not necessarily appear as a professional end for everyone, even though they recognize the quality of their training.

Complementing the previous excerpts, it was possible to notice that, although some students show pessimism or a certain disbelief due to the economic crisis, widely disseminated by the communication channels, several of them attribute to themselves the responsibility for entering the world of work, using a speech aimed at developing their own skills and qualities as a way to guarantee a good place in the market.

From the moment I graduate I already know what I like and do not like within the area. Then it is about going after an internship, a job in what I like best so that I can already enter the job market (School A student).

You have to be determined... so, you have to be focused too (School C Student)

I think I'm too young to decide what I have as a professional goal, but I always keep in mind that I cannot stop studying, because I think that the more I specialize, the more the doors will be open for me (School C student)

I think that's how it is, in my case, where I work, those who are dedicated and do the job well done, those get a promotion. (Student C school)

It is concluded that the future is portrayed as a time horizon that is made achievable by individuals’ inherent willingness to pursue their goals, based on a kind of fiber that allows them to be prepared to face all kinds of adversity and affording a sense to act in the present. As understood by Leccardi (2005, p. 36, emphasis added) “In this perspective, the future is the space for the construction of a life project and, at the same time, for self-definition: as one projects what will be done in the future, it is also projected, in parallel, who one will be”.

With regard to students’ motivations, perceptions and expectations about technical courses and educational institutions, the historical materialism developed by Marx and Engels (2007) in “The German Ideology” offers a robust contribution. First, the authors state that human existence and the way to satisfy its needs is the assumption of human history itself, as it is “[...] a fundamental condition of all history, which even today, as well as for millennia, has to be performed daily, every hour, simply to keep men alive”(MARX; ENGELS, 2007, p. 32).

However, it is necessary to emphasize that this explanatory approach to human life recognizes that, although humans make themselves human from the bonds they encounter in their material life, they are active subjects in the historical process. That is, at the same time that the human being depends on material conditions in place, regardless of his will, his ability to act throughout history can change his reality, thus generating new conditions of life.

The way in which men produce their means of subsistence depends first of all on the nature of the actual means of subsistence they find in existence and have to reproduce. This mode of production must not be considered simply as being the production of the physical existence of the individuals. Rather it is a definite form of activity of these individuals, a definite form of expressing their life, a definite mode of life on their part. As individuals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production, both with what they produce and with how they produce. The nature of individuals thus depends on the material conditions determining their production. (MARX; ENGELS, 2007, p.88).

The reasoning about the individuals, therefore, does not understand them as a mere effect of economic determinations, but as part of a process of human formation in which there is no subject without an object and vice versa, that is, at the same time as the immediate material conditions forge the objectification of human life, this, in turn, enables forms of subjectification. Marx and Engels strive to elucidate that the construction of subjectivity that is expressed in consciousness is socially constructed, in a given social formation and consequent historical time, because “All social life is essentially practical” (eighth thesis on Feuerbach). Consciousness, therefore, would be built based on the circumstances experienced by individuals and not as an isolated activity.

Men are the producers of their conceptions, ideas, etc. -- real, active men, as they are conditioned by a definite development of their productive forces and of the intercourse corresponding to these, up to its furthest forms. Consciousness [Bewusstsein] can never be anything else than conscious existence [bewusste Sein], and the existence of men is their actual life-process (MARX; ENGELS, 2007, p.94).

In this case, Marx and Engels understand that expressions of subjectivity commonly related to the individuality of the human being, such as will, aptitude, effort, gift, are not explained by a natural abstract essence and that ends in the individuals themselves, but through material conditions in which these individuals are formed as social beings. This understanding, which completely removes the vision of an atomized individual, gives protagonism to praxis as an instance of realization of the humanization of the human being himself.

The development of an individual is determined by the development of all the others with whom he is directly or indirectly associative, and that the different generations of individuals entering into relations with one another are connected with one another, that the physical existence of the latter generations is determined by that of their predecessors, and that these later generations inherit the productive forces and forms of intercourse accumulated by their predecessors, their own mutual relations being determined thereby. In short, it is clear that development takes place and that the history of the single individual cannot possibly be separated from the history of preceding or contemporary individuals, but is determined by this history (MARX; ENGELS, 2007, p. 422).

That is, supported by Marx and Engels, it is argued that the material expressions of human subjectivity, such as will, thought, vocation and life project are aspects forged by contracted social relations and this set of developed and manifested capabilities represents the ways in which individuals are involved with the world and the possibilities for future developments.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Throughout the text, it was sought to establish that EPTNM is immersed in a field of disputes that tries to attribute formative meanings to it and how this type of education is related to the educational context and the work world. This is because education, as a part of capitalist social relations, therefore, markedly contradictory, also carries with it this contradiction, because, on the one hand, the business community requires the training of the workforce to be aligned with its assumptions, which are recurrently pragmatic to a certain historical time and to a pattern of production organization, access to qualified technical education is also a demand of the working class, both in relation to postulating a salary base that allows them to have a more comfortable material subsistence and enjoying the right to education, aiming at self-development.

From what was described in the article, it appears that EPTNM has had a significant expansion since the 21st century, especially since 2007, with the resumption of investment by the federal government in the construction of teaching units and the campus of the Federal Institutes, as well as the myriad of actions and programs to raise EPTNM as an axis to sustain the maintenance of the resumption of economic development. However, the expansion of EPTNM and the very constitution of the Federal Network for Professional, Scientific and Technological Education came up against structural factors typical of Brazilian capitalism. Although the fractions of the dominant class require a more educated workforce, it would not be necessary for complex training to reach such high levels, as the pattern of work occupations is still sustained with low and medium schooling levels. Thus, concurrent with the expansion of EPTNM, driven by federal institutions in the form of integrated high school, large resources were also allocated to training in professional qualification courses promoted by private establishments, especially linked to the S System.

This whole meander regarding EPTNM occurs in a historical context of intense precariousness of work and expropriation of rights. The discursive lexicon engendered by its defenders and widely disseminated by the media is based on an imaginary that the relaxation of labor laws and reforms in the functioning of the State will promote the purge of the economic crisis, and, consequently, the resumption of jobs. Such phraseology about the world is based on the fact that the dominant social relations are expressed as ideas, because “The ideas of the ruling class are, in each epoch, the dominant ideas, that is, the class that is the dominant material force of society is, at the same time, its dominant spiritual strength” (MARX; ENGELS, 2007, p. 47). Therefore, they are ideas that, instead of revealing the materiality of the world, hide them and produce inversions that seek to justify why certain measures would be necessary (for example, labor reform is seen as necessary for the resumption of jobs for the working class, but it serves to lower capitalists' labor costs).

Faced with a regressive and unfavorable situation, we sought to hear how EPTNM students express their motivations, perceptions and expectations regarding professional training and possible entry into the work world. It is argued in this text that individuals’ conscience is strongly influenced by the material relations of production and the place that individuals occupy in it. Therefore, their subjective expressions, such as choice, will, aptitude, among others, are related to their objective means of life. However, the human being as a social being capable of recreating and transforming his means of objectification, also has the ability to alter the subjectivity with which he feels and interprets life. Therefore, there is a rejection of any kind of economic determinism as a direct relation to the formation of human consciousness.

Students, through interviews, identified and some even valued the family's influence on their choices and destinies; they judged the limits and possibilities of the training processes to which they are submitted; they interpreted that the capital crisis brings them concrete difficulties for the present time and in any type of future projection, which is also part of the process of self-formation of individuals who are in a kind of rite of passage into adulthood; and, even in the midst of difficulties imposed by situations beyond their direct control, they believe that they can resort to strategies to overcome them. This brief synthesis of the results of the field research made it possible to highlight the EPTNM students' elaboration about their present and projection perspectives, which becomes somewhat challenging, considering the regressive historical situation in the world of work and education. However, if uncertainty and unpredictability are evident in the present time, the ability to recreate and transform human beings, especially the inventiveness of the youngest, offers a possibility of a turnaround for better days.

REFERENCES

ABÍLIO, Ludmila C. Uberização do trabalho: subsunção real da viração. Blog da Boitempo, publicado em: 22 fev. 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://blogdaboitempo.com.br/2017/02/22/uberizacao-do-trabalho-subsuncao-real-da-viracao/ . Acesso em:23 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

ALVES, Giovanni. Dimensões da precarização do trabalho: ensaios de Sociologia do Trabalho. Bauru: Canal 6 Editora, 2013. [ Links ]

ANTUNES, Ricardo. O privilégio da servidão: o novo proletariado de serviços na era digital. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 23 dez.1996. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9394.htm , acesso em 20 out. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 5.154, de 23 de julho de 2004. Regulamenta o § 2º do art. 36 e os arts. 39 a 41 da Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, DF, 2004, 26 jul. 2004. Disponível em Disponível em http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2004/decreto/d5154.htm . Acesso em:20 out. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 11.741, de 16 de julho de 2008. Altera dispositivos da Lei no9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para redimensionar, institucionalizar e integrar as ações da educação profissional técnica de nível médio, da educação de jovens e adultos e da educação profissional e tecnológica. Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, DF, 17 jul. 2008. Disponivel em:Disponivel em:http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2008/lei/l11741.htm . Acesso em: 20 out. 2020. [ Links ]

BOLSONARO, Jair. Com a palavra [Entrevista a Leda Nagle]. Publicado em: 5 ago. 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLLxBxN87ZE . Acesso em:22 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. A escola conservadora: as desigualdades frente à escola e à cultura. In: NOGUEIRA, M. A; CATANI, A (orgs.). Escritos de educação. 16 ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2015, p. 43-72. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação - PNE e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, edição extra, Brasília, DF, 26 jun. 2014. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/lei/2014/lei-13005-25-junho-2014-778970-publicacaooriginal-144468-pl.html . Acesso em: 30 mar. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Relatório do 2º ciclo de monitoramento das metas do PNE: biênio 2016-2018. Brasília: INEP, 2018. [ Links ]

CAIRES, Vanessa.; OLIVEIRA, Maria Aparecida. Educação Profissional brasileira: da Colônia ao PNE 2014-2024. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2016. [ Links ]

CASSIOLATO, Maria Martha; GARCIA, Ronaldo. Pronatec: múltiplos arranjos e ações para ampliar o acesso à educação profissional. Brasília, Rio de Janeiro: IPEA, 2014. [ Links ]

COSTA, Fernanda. A execução orçamentária do Programa Nacional de Acesso ao Ensino Técnico e Emprego (Pronatec) entre 2011 e 2014. In: Marx e Marxismo 2015: insurreições, passado e presente, 2015, Niterói. Anais..., Niterói, 2015. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO, Moaci. LDB fácil: leitura crítico-compreensiva, artigo a artigo. 23 ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2015. [ Links ]

CORREA, Licinia; CUNHA, Maria Amália. A política educativa e seus efeitos nos tempos e espaços escolares: a reinvenção do ensino médio interpretada pelos jovens. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, n. 34, e182749, 2018. [ Links ]

DEITOS, Roberto.; LARA, Angela. Educação profissional no Brasil: motivos socioeconômicos e ideológicos da política educacional. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 21, n. 64, p. 165-188, jan./mar. 2016. [ Links ]

FONTES, Virgínia. O Brasil e o capital-imperialismo: teoria e história. Rio de Janeiro: ESPJV, UFRJ, 2010. [ Links ]

GOMES, Alberto. Apontamentos sobre a pesquisa em educação: usos e possibilidades do grupo focal. Eccos, São Paulo, v. 7, n. 2, p. 275-290, jul./dez. 2005. [ Links ]

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua - Segundo trimestre de 2019. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/2421/pnact_2019_2tri.pdf , acesso em 23 set. 2019. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sinopse Estatística da Educação Básica. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2003. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://inep.gov.br/sinopses-estatisticas-da-educacao-basica . Acesso em: 16 set. 2019. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sinopse Estatística da Educação Básica. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2008. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://inep.gov.br/sinopses-estatisticas-da-educacao-basica . Acesso em: 16 set. 2019. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sinopse Estatística da Educação Básica. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://inep.gov.br/sinopses-estatisticas-da-educacao-basica . Acesso em:16 set. 2019. [ Links ]

LEÃO, Geraldo; DAYRELL, Juarez; REIS, Juliana. Juventude, projetos de vida e ensino médio. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 32, n. 117, p. 1067-1084, out./dez. 2011. [ Links ]

LECCARDI, Carmen. Por um novo significado do futuro: mudança social, jovens e tempo. Tempo Social, São Paulo, v. 17, n. 2, p. 35-57, nov. 2005. [ Links ]

MARCASSA, Luciana; CONDE, Soraya. Juventude, trabalho e escola em territórios de precariedade social. In: Reunião Nacional da Associação Nacional de Pesquisa em Pós-Graduação em Educação, 38, 2017, São Luís. Anais [...]. Rio de Janeiro: ANPEd, 2017. [ Links ]

MARX, Karl; ENGELS, Friedrich. A Ideologia alemã. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2007. [ Links ]

MOTTA, Vânia; FRIGOTTO, Gaudêncio. Por que a urgência da Reforma do Ensino Médio? Medida Provisória nº 746/2016. Lei nº 13.415/2017. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 355-372, abr./jun.2017. [ Links ]

MOTTA, Vânia; LEHER, Roberto; GAWRYSZEWSKI, Bruno. A pedagogia do capital e o sentido das resistências da classe trabalhadora. Ser Social, n. 43, p. 310-328, jul./dez. 2018. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, Cláudio; RESENDE, Tânia; VIANA, Maria José. Escolha do estabelecimento de ensino, mobilização familiar e desempenho escolar. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 20. n. 62, p. 749-772, jul./set. 2015. [ Links ]

OCDE. ORGANIZAÇÃO PARA A COOPERAÇÃO E DESENVOLVIMENTO ECONÔMICO. Education at a Glance 2018: OECD Indicators. Paris: OCDE, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://download.inep.gov.br/acoes_internacionais/eag/documentos/2018/EAG_Relatorio_na_integra.pdf . Acesso em:22 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Jailson; RODRIGUES, José. (Des) Caminhos da política de expansão da Rede Federal de Educação Profissional, Científica e Tecnológica: contradições na trajetória histórica. Marx e o Marxismo, Niterói, v.3, n.4, p.88-112, jan/jun.2015. [ Links ]

1The translation of this article into English was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES-Brasil.

4It should be noted that the 2018 annual report of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which is called Education at a Glance, informs that Brazil, in 2016, had 9% of high school enrollments in professional education (OECD, 2018). However, the quantity reported does not even match the official figures reported by the Brazilian State, given that, in 2016, a total of 8,133,040 enrollments were made and that, of these, 531,843 were integrated and 329,033 were concomitant, which makes a total of 860,876 enrollments (INEP, 2019). It is not possible to point out whether the source of the error was the Brazilian State or the international organization, but there is a mistake.

5The other target that directly refers to Professional Education is target 10, which defines offering at least 25% of enrollments in Youth and Adult Education integrated with Professional Education. In recent years, integrated enrollments peaked in 2015, with 3% and, since then, have decreased to half the proportional quantity (BRASIL, 2018).

6Designation made to the group of institutions that make up the entities linked to the services provided in the training and professional qualification and social and recreational activities of each Brazilian economic segment. The respective institutions are linked to the National Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock of Brazil, National Confederation of Commerce, National Confederation of Industry, National Confederation of Transport, and the National Cooperative System.

Received: July 12, 2019; Accepted: October 02, 2020

texto em

texto em