Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 10-Mar-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698229524

ARTICLE

TEACHERS TRAINING IN THE HIGHER EDUCATION INTERFACE - RURAL AREA EDUCATION: ANtALYSIS FROM THE UNIOESTE EXPERIENCE

1PhD in Education. Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB). Amargosa, BA, Brazil. <alexverderio@outlook.com>

2PhD in Humanities and Social Sciences. Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB). Amargosa, BA, Brazil. <janainezs@yahoo.com.br>

3Doctoral student in Education. Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná (UNIOESTE). Cascavel, PR, Brazil. <jcvncampos@gmail.com>

4Doctoral student in Education. Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM). Maringá, PR, Brazil. <valterleitemstpr@gmail.com>

This article analyzes the route and effectiveness of the undergraduate courses in alternation for rural area teachers in training in the Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná (UNIOESTE), focusing on the insertion and stay of the popular sectors in state universities. The empirical reference are the experiences from the Pedagogy courses for Rural Area Teachers and the Degree in Rural Area Education, finished between 2004-2017 at UNIOESTE, which had 137 graduates. In addition to the experiences, the analysis focused on their monographs showed that when talking about the reality questions of insertion from the students-researchers show the relation between show the relation between Higher and Basic Education from the teachers training. The analyzed training experiences imprint contributions in the attribution of new meanings to the social role of universities that focus on the resizing of the access, content and form in Higher Education in its interface with Rural Area Education.

Keywords: Superior Education; Rural Area Education; Alternation Regimen; Popular Sectors Inclusion

Analisa o percurso e a efetividade dos cursos de graduação em alternância para formação de educadoras e educadores do campo na Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná (Unioeste), com foco na inserção e permanência dos setores populares na Universidade pública. A elaboração tem como referencial empírico as experiências dos cursos de Pedagogia para Educadores do Campo e Licenciatura em Educação do Campo, concretizadas entre 2004 - 2017 na Unioeste e que promoveram a formação de 137 estudantes. Além das experiências, a análise voltou-se para as Monografias elaboradas nos cursos que, ao tratar de questões da realidade de inserção dos estudantes-pesquisadores evidenciam a relação entre Educação Superior e Educação Básica do Campo a partir da formação de educadores. As experiências formativas analisadas imprimem contribuições na ressignificação da função social da Universidade que incidem no redimensionamento do acesso, do conteúdo e da forma na Educação Superior em sua interface com a Educação do Campo.

Palavras-chave: Educação Superior; Educação do Campo; Regime de Alternância; Inclusão de Setores Populares

Analiza el curso y la efectividad de carreras de graduación en alternancia para formación de educadores del campo en la Universidad Estatal del Oeste de Paraná (Unioeste), con foco en la inserción y permanencia de sectores populares en la universidad pública. La elaboración tiene como referencial empírico las experiencias de carreras de Pedagogía para Educadores en contextos rurales y Licenciatura en Educación en el Contexto Rural, realizadas entre 2004 - 2017 en la Unioeste y que promovieron la formación de 137 estudiantes. Además de las experiencias, el análisis volcó-se para las monografías elaboradas en estas carreras que, al tratar de cuestiones de la realidad de inserción de los estudiantes-investigadores evidencian la relación entre Educación Universitaria y Educación Básica en contextos rurales a partir de la formación de educadores. Las experiencias formativas analizadas imprimen contribuciones en la resignificación de la función social de la Universidad que inciden en el redimensionamiento del acceso, del contenido y de la forma en la Educación Universitaria en su interfaz con la Educación en Contexto Rural.

Palabras clave: Educación Universitaria; Educación en Contextos Rurales; Régimen de Alternancia; Inclusión de Sectores Populares

INTRODUCTION

The Public University in Brazil was founded as a space restricted to the education of the ruling elites. This understanding is affirmed across historically situated studies which keep their analytical relevance, such as Álvaro Vieira Pinto (1994) and Marilene Chauí (2001), allowing for the verification of elements outlining the role of the University within the Brazilian context and, at the same time, unequivocally underline its eminently exclusive character.

However, in the early years of the 21st century, this elitist and conservative conception of the Brazilian Public University started being questioned by movements comprised of sectors of the popular classes that, until then, had been denied access to higher education. This scenario was strengthened, in particular, with the political agreements signed in Brazilian society. Thus, in the last fifteen years - the first of the 21st century - the Brazilian Public University started taking into consideration some claims of the working class regarding higher education. In this process, quotas for black and indigenous students, as well as the insertion of students from public schools, have been given special attention. Such actions have been permeated by countless disputes and contradictions, but, in turn, produced important changes in the profile of the Brazilian university student. This reconfiguration took place as an echo of a set of public policies intended to achieve this result, as reflected across the studies recorded by Loss et al. (2018) and Loss and Vain (2018).

Among the public policies implemented for this purpose, stand out the ones related to the struggle for Rural Education. Their effects have also reached the University, which boosted the incorporation and implementation of actions addressed to the working people of rural areas, shaping and boosting the interface between Higher and Rural Education in the context of Brazilian public Universities. It is in this context that the struggle for Rural Education in Brazil, even in the face of countless losses and setbacks, has produced effective action within the scope of the conquest of public policies in a complementary and reciprocal way - at all levels and spheres - and the guarantee of educational processes, always mediatized and tensioned within the class society, but also related to the perspectives and demands of the rural workers involved in the struggle. This process is both sustained and supportive of the action carried out by rural workers, above all, through their social organizations. Within this framework,

[...] the struggle for Rural Education is understood as the articulation of diverse subjects committed to the education of rural workers in Brazil, having as a central element the subjects which they bring to the forefront in the proposition and in the realization of an education that meets their interests and, while connected to counter-hegemonic educational processes, places itself within the social transformation and human emancipation perspective.

Thus, the struggle for Rural Education starts from the very diversity of rural workers in Brazil and the educational practices and perspectives forged within their social struggles. The struggle for Rural Education is different within the class unit. It is neither homogeneous nor uniform but has a materiality of origin that imbues it with both identity and unity (VERDÉRIO, 2018, p. 66-67).

While immersed in continuous clashes, this contradictory scenario instigates the reflection and analysis processes carried out in the controversy amidst achievements and setbacks, ruptures and conservatism, where the old and the new are placed at the same time in the Public University, which is tensioned on a daily basis within the context of the class struggle. If, on the one hand, the Public University is contingent on expanding its capillarity and the openness for the insertion of diverse subjects who, until then, had not been able to attend it; at the same time, it is surrounded by the authoritarian, oligarchic, and violent patterns promoted by Brazilian and capitalist societies in general (CHAUÍ, 2001).

In the context of promoting studies and research to qualitatively analyze this insertion, the Programa de Desenvolvimento Acadêmico Abdias Nascimento (Academic Development Program Abdias Nascimento), ruled by the SECADI/CAPES Notice No. 02/2014, has been placed as a concrete possibility for the analysis and systematization of elements concerning the inclusion and permanence of Popular Sectors in Higher Education. With the investigative perspective adopted in the research, taking into consideration the insertion and permanence actions developed by UNIOESTE, especially between 2004 and 2017, we opted for an analysis focused on the actions carried out within the Higher and Rural Education interface sustained by a partnership with Rural Popular Social Movements that brought into the Public University a portion of the Brazilian society which, until recently, did not have any perspective of access to Higher Education.

Thus, the Rural Education Research Axis was created, in line with the research proposal tied to the Abdias Nascimento Program, aimed at analyzing the training of rural educators at UNIOESTE in partnership with the Rural Popular Social Movements.

In addition to the organic link with the analyzed training processes, documentary research and bibliographic research stood out among the methodological procedures.

As the first empirical references, the National Education Program on Agrarian Reform (PRONERA) and the Support Program for the Licentiate degree in Rural Education (PROCAMPO) were considered in their effectiveness with UNIOESTE, which allowed the formation of rural educators to be completed in higher-level courses, organized alternately. The analysis of these two Programs - PRONERA and PROCAMPO - and of some of their actions that, among others, comprise the public policy for the Rural Education in Brazil, had the comprehension produced collectively in the struggle for Rural Education as a key analysis, understanding that it is from the organized struggle of rural workers that the State, through its public policies, will answer to the demands of different social sectors in face of their claims. In this way, public policies are characterized as mediatized and continuously tensioned actions, sometimes guided by the hegemonic orientation of the State, sometimes guided by the struggles of the working class, in this case, the rural workers and their organizations.

Based on the data produced and the analysis on the effectiveness of PRONERA and PROCAMPO, the profile of the public that joined Higher Education programs at UNIOESTE through the Pedagogy for Rural Educators and Licentiate in Rural Education courses was analyzed. For this purpose, a mapping of the subjects participating in the four classes of the two courses at the University was elaborated. As empirical references of the research were taken: The Living Memorials elaborated in the process of selecting the classes, the Undergraduate Thesis, and the documents related to the courses filed at the University.

From the production of research data and with the analysis of the profile of the constituent public of each undergraduate course class in Rural Education at UNIOESTE, it was also possible to establish a profile of the academic-scientific production of those who were involved. In these terms, there was the core element of analysis and comprehension that the understanding that the link with Higher Education within the interface with Rural Education in the context of UNIOESTE had the connection to Rural Popular Social Movements as a reference of insertion and permanence. This key to reading and understanding has been evidenced from the analysis of the 137 Undergraduate Thesis produced by the Pedagogy for Rural Educators and Licentiate degree in Rural Education students from UNIOESTE.

Taken as a whole, the data produced allowed the perception that the insertion in graduation through the effectiveness of affirmative public policies and inclusion opens a range of possibilities for practical-theoretical reflection on the educational actions developed within the scope of Rural Popular Social Movements and Rural Basic Education translated, among others, through the elaboration of the Undergraduate Thesis.

THE TRAINING OF RURAL EDUCATORS AND THE AFFIRMATION OF THE PUBLIC POLICIES ON RURAL EDUCATION: PRONERA AND PROCAMPO

Public policies on Rural Education have been perceived by the Brazilian State as a result of the struggle, organization, and mobilization of rural workers in the perspective of enforcing their right to education. In this context are highlighted two Government Programs focused on Rural Education in its interface with Higher Education: PRONERA and PROCAMPO.

PRONERA was instituted on April 16, 1998, through Ordinance No. 10, from the extinct Ministério Extraordinário da Política Fundiária (Extraordinary Ministry of Land Policy) (SANTOS, 2012), and presented to Brazilian society at the I Conferência Nacional de Educação do Campo (1st National Conference on Rural Education), which also took place in 1998. It should be noted that:

The initial period of the experiment - between 1998-2002 - is marked by an intense conflict, as the National State and its Minimal State policy conflicted with popular initiatives such as the very one under analysis. It is interesting to observe this contradiction, as it is precisely at the moment of greater intensity in the fight against social movements, and when public policies are scarce for the population as a whole, that a popular public policy initiative advances (GHEDINI et al., 2018, p. 265-266).

Based on this context, PRONERA aims to:

Strengthening the education provided in areas of Agrarian Reform by stimulating, proposing, creating, developing, and coordinating educational projects while adopting methodologies geared to the specificity of the rural areas, with a view to contributing to the promotion of social inclusion with sustainable development in Agrarian Reform Settlement Projects (BRAZIL, 2016, p. 18).

PRONERA is a milestone in the structuring of Rural Education in Brazil, also within the public policy scope. Its effectiveness makes it “[...] the first large-scale action by the Brazilian State in the perspective of constituting an emphatic response to the struggle for Rural Education; it marks a new understanding regarding governmental actions directly related to social claims.” (VERDÉRIO, 2018, p. 96).

Among the innovations introduced by PRONERA stands out the tripartite management model, with the participation of members of the federal government, universities, and social movements [...]. Higher education institutions have a strategic role within the Program, as they accumulate mediation roles between social movements and the Instituto de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (INCRA, Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform), of administrative-financial management, and pedagogical coordination of the projects. The social movements are responsible for mobilizing communities, while INCRA’s Regional Superintendencies (SRs) deal with financial monitoring, logistical support, and interinstitutional articulation. In theory, the state and municipal education departments should support the implementation of the projects, ensuring their continuity, which rarely is the case (ANDRADE; DI PIERRO, 2004, p. 22-23).

Presidential Decree No. 7,352 of November 4, 2010, in turn, established PRONERA as an integral part of the public policies for Rural Education. According to information collected from INCRA’s official website, throughout its eighteen years of existence, PRONERA has enabled the training of more than 185 thousand young people and adults beneficiated from the Programa Nacional de Reforma Agrária (National Agrarian Reform Program) (INCRA, 2016). In addition to the direct beneficiaries’ program, other people potentially assisted by PRONERA are:

Teachers and educators, with an effective or temporary contract with the Municipal and/or State Education Departments, carrying out educational activities in direct service to the beneficiary families in schools located both in the settlements and their surroundings and who serve the settled community, which should be confirmed by a document issued by one of the bodies mentioned. (BRAZIL, 2016, p. 21).

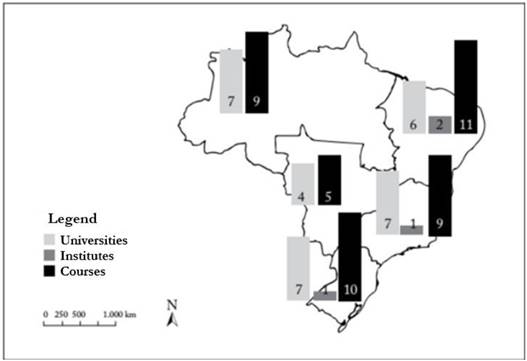

Map 1 presents a panorama allowing for the sizing of the PRONERA’s scope at the national level with its rotational undergraduate courses carried out between 1998 and 2011.

While expressing concrete actions for the access and permanence of people from popular sectors in the Brazilian Public University, the panorama presented in Map 1 also registers PRONERA’s character as a driver of the interface between Higher and Rural Education. This character affects the design and capillarity of public policies for Rural Education within the national territory, especially through undergraduate courses for the rotational training of rural educators, including the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators offered by UNIOESTE in partnership with the Rural Popular Social Movements and PRONERA itself.

According to data from the II Pesquisa Nacional sobre a Educação na Reforma Agrária (II National Survey on Education in Agrarian Reform) (IPEA, 2015), 320 courses were carried out through PRONERA between 1998 and 2011, 167 of which were Youth and Adult Elementary Education courses, 99 were High School courses, and 54 were Higher Education courses.

Horácio (2015), in turn, noted that there have been nineteen classes of the Pedagogy of the Earth rotational course in Brazil between 1998 and 2014. The classes were carried out through PRONERA and involved twelve public Universities. This data allows for the assessment of the training of rural educators in rotational undergraduate courses as an achievement for the struggle for Rural Education driven by PRONERA since 1998.

Just like PRONERA, as of 2008, PROCAMPO assumed the role of fundamental action by the Federal Government in promoting and carrying out the training of rural educators in Brazil, culminating with the establishment of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education in State and Federal Universities, and Higher Education Institutes.

According to Ramos et al. (2004, p. 5), the proposal for the Licentiate degree in Rural Education and PROCAMPO’s formulation were initially processed within the Grupo Permanente de Trabalho em Educação do Campo (Permanent Working Group on Rural Education), “[...] established under the scope of MEC by Ordinance No. 1,374 of 06/03/03, with the attribution of articulating the Ministry’s actions pertaining to Rural Education [...]”. One of the results achieved by this Permanent Working Group was the formulation of the original draft of the Full Licentiate Degree in Rural Education (MEC, 2006), which subsequently supported the undertaking of the first four pilot experiences6 of the implementation of the course in Brazil.

From the realization of the pilot experiments in 2008 and through the Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização, Diversidade e Inclusão (SECADI, Secretariat of Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion), MEC published the first public notice for the implementation of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education at Universities willing to submit their proposals. With the first call from PROCAMPO, 27 proposals were selected to carry out the course in fourteen states of the federation, plus the Federal District (BRAZIL, 2008). Among the proposals approved PROCAMPO’s 2008 call for proposals, there was the one presented by UNIOESTE campus Cascavel.

In April 2009, MEC published the Call Notice No. 09, thus constituting PROCAMPO’s second public notice. Considering the courses approved by the 2008 call, together with the courses approved by the 2009 call, MEC announced the participation of 33 Higher Education Institutions in PROCAMPO until 2010. According to Brazil (2010), the execution of the two public notices promoted the assembly of 56 classes of the course and a total of 3,358 places made available for the training of rural educators in the Licentiate degree in Rural Education rotational courses by areas of knowledge.

In March 2012, PROCAMPO became part of the Programa Nacional de Educação do Campo (PRONACAMPO, National Rural Education Program). Within the scope intended by MEC’s action, PRONACAMPO, both proposed and managed by SECADI, was characterized as “[...] an articulated set of actions to support the education systems for the implementation of Rural Education policies, as provided in the Decree No. 7,352, of November 4, 2010” (BRAZIL, 2013, p. 1). With PRONACAMPO’s establishment within the scope of the training of rural educators in undergraduate courses, among others, the two structural elements of Licentiate courses in Rural Education in Brazil were reaffirmed: the rotational regime and the training by areas of knowledge.

According to information compiled by Verdério (2018), from Ordinance No. 72, of December 21, 2012, which disclosed the result of the third selection of proposals submitted to PROCAMPO, it appears that the third call for proposals included a set of 44 Federal Universities across nineteen Brazilian states, plus the Federal District.

According to Map 2, Map appears that with the third call for PROCAMPO there was a significant increase in the offer of vacancies and implementation of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education in Brazil. This significant increase was causally related to the facilitation provided by PROCAMPO’s third call for bids, which ensured that the Federal Universities adhered to the call for bids for the hiring of fifteen permanent professors and three administrative technicians, together with an initial financial support of BRL 4,000.00 student/year. MEC’s willingness MEC to make the hiring of teachers and educational technicians available through public tender, plus the initial funding resources for the constitution of the classes, boosted PROCAMPO and the expansion of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education as a priority action by MEC within Federal Universities.

SOURCE: Leal et al. (2019, p. 47).

Map 2: Territorialization of undergraduate courses in Rural Education, Brazil

According to Molina et al. (2019, p. 10) and as demonstrated in Map 2, there are 44 undergraduate courses in Rural Education in progress in Brazil, spread across 31 Universities and four Federal Institutes of Education. Also, according to the data systematized by Verdério (2018), until 2018, when considering all Universities (State and Federal), Federal Education Institutes, and other Higher Education Institutions involved with PROCAMPO, a total of 53 Higher Education Institutions in Brazil have developed or were working on the development of experimentation with the Licentiate degree in Rural Education, organized in areas of knowledge and carried out under the rotational regime.

UNIOESTE AND THE TRAINING OF RURAL EDUCATORS: PEDAGOGY FOR RURAL EDUCATORS AND LICENTIATE DEGREE IN RURAL EDUCATION

The demand for rotational undergraduate courses in Paraná has its most elaborated expression based on the performance of the Articulação Paranaense por uma Educação do Campo (APEC). It was at the II Conferência Estadual de Educação do Campo (2nd State Conference on Rural Education), which took place in November 2000 in Porto Barreiro, PR - Brazil, that such claim took off and reached public institutions of higher education within the state.

The claim for the “Creation of the Pedagogy of the Earth course in the State of Paraná” was recorded in the Carta de Porto Barreiro (APEC, 2000, p. 56). This need had already been pointed out by the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST, Landless Rural Workers Movement) since the institution of PRONERA, in 1998. However, it was the holding of the II Conferência Estadual de Educação do Campo that boosted this demand, bringing it to the forefront of the struggle for Rural Education in Paraná. UNIOESTE was among the various promoters of the Conference, which favored the development of the course within the University.

The initial projection of a rotational undergraduate course to train rural educators at UNIOESTE, together with the demands of the rural workers, gained momentum during the strike initiated by the employees of Paraná State Universities in the early 2000s.

Between 2001 and 2002, universities in Paraná endure a long period of strikes. Amidst this process, a group of UNIOESTE civil servants got involved in the debate concerning the social role of the university, especially in the area where it is located, a conversation that culminated in the recommendation of a seminar to discuss the agrarian issue. With this event comes the proposition that the elaboration of a project for the training of rural educators should be a priority (UNIOESTE, 2006, p. 02).

The claim by rural workers - expressed in the Carta de Porto Barreiro - in direct connection with the internal disposition of UNIOESTE - brought about by their participation in the 2nd Conference and by the strike movement that intensified the debate on the university’s social role - together with PRONERA’s effectiveness produced the initial objective conditions for the gestation of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators. Subsequently, these initial elements, together with the experience accumulated by UNIOESTE through the Pedagogy of Earth course emerged as a cornerstone for the proposition of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education at the University under PROCAMPO.

UNIOESTE is a state Public University with a multicampus character that has its scope distributed across the Western and Southwestern regions of Paraná, consolidated by its five campuses located in the municipalities of Cascavel, Foz do Iguaçu, Francisco Beltrão, Marechal Cândido Rondon, and Toledo.

UNIOESTE was constituted as a state public institution of Higher Education in 1994, from “[...] the congregation of isolated municipal colleges created in Cascavel (FECIVEL, 1972), Foz do Iguaçu (FACISA, 1979), Marechal Candido Rondon (FACIMAR, 1980), and Toledo (FACITOL, 1980).” (UNIOESTE, 2017). In 1998, its fifth university campus was established with the incorporation of FACIBEL, located in the municipality of Francisco Beltrão. According to information presented on the institution’s official website (UNIOESTE, 2017), it covers 94 municipalities, 52 of which are located in the West and 42 in the Southwest of Paraná.

According to information available through Data Bulletins (UNIOESTE, 2019), it appears that, between 2004 and 2017, the University offered four rotational undergraduate classes for the training of rural educators, three of them linked to PRONERA and one to PROCAMPO. Considering data concerning campus Francisco Beltrão, where the first class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators took place between 2004 and 2008, it seems that, of the 560 enrollments relevant to degree courses on the campus in the academic year of 2007, 36 were related to the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators, started in 2004. The 36 enrollments amount to 6.4% of all enrollments for undergraduate courses at the Francisco Beltrão campus in 2007.

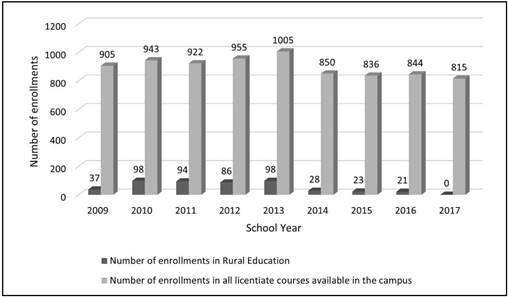

In 2009, when the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators was transferred to Cascavel campus and the agreement with PROCAMPO is signed for the implementation of a class for the Licentiate degree in Rural Education, it is clear that UNIOESTE is becoming a strong hub for the training of rural educators. As a result - demonstrated in Graph 1 -, there is an increase in the number of enrollments for the licentiate undergraduate courses offered on the University’s campus in Cascavel.

SOURCE: Prepared by the authors (2019).

Graph 1: Students enrolled in Licentiate courses at UNIOESTE’s campus in Cascavel 2009 - 2017

According to the information in Graph 1, it is demonstrated that the implementation of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators and Licentiate degree in Rural Education at UNIOESTE’s campus in Cascavel became a fundamental factor for the insertion of popular sectors, especially rural workers, in Higher Education. It is also noteworthy that these actions constituted an element of important representativeness regarding the percentage of enrollments in undergraduate courses offered by the University’s campus in Cascavel, which started to offer the two rotational training courses for rural educators concurrently at UNIOESTE.

Also, according to the synthesis shown in Graph 1, it is highlighted that the peak of insertion and incidence of training courses for rural educators in alternation at UNIOESTE occurred in the academic years of 2010 and 2011, with the concomitant completion of the course of Pedagogy for Educators of the rural - PRONERA - and of the course of Degree in Education of the rural - PROCAMPO. In 2010, the 98 enrollments pertaining to the two courses represented 10.4% of the total enrollments for the campus’s licentiate courses. In 2011, 94 enrollments in both courses made up for 10.2% of the total enrollments for the campus’s licentiate courses. Bear in mind that, of the nine courses offered by the University in the years mentioned, two were focused on Rural Education and provided in a rotational regime, offered in specific classes, and carried out as a pedagogical experiment and as a result of the design of the public policies for Rural Education.

The Pedagogy course for Rural Educators and Licentiate degree in Rural Education, among other actions, highlight UNIOESTE’s protagonism and pioneering, together with the Rural Popular Social Movements, in the interface of Higher and Rural Education and the offer of rotational courses in Paraná, allowing for the insertion of a segment of the popular sectors that had not been able to access Higher Education until then.

As previously noted, the first rotational class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE took place between 2004 and 2008, on the Francisco Beltrão campus. This was the first class of the Pedagogy of the Earth course in Paraná and was comprised of the students participating in the Antonio Gramsci class7.

According to the Political-Pedagogical Project (PPP) of the course (UNIOESTE, 2004 and 2013), all three classes of the Pedagogy for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE aimed at training educators to work in the early years of Elementary School and Child Education, as well as Youth and Adult Education.

The struggle for the creation of this first rotational course in Paraná originated in the II Conferência Estadual por uma Educação do Campo, held in 2000. The favorable ruling of the Pedagogical Council of PRONERA for the creation of the course took place on October 13, 2003. On October 28 of the same year, through Resolution 145/2003 of its Conselho de Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão (CEPE, Teaching, Research, and Extension Council), UNIOESTE managed to approve the PPP of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators, as a Licentiate course in special regime linked to the Centro de Ciências Humanas (CCH, Human Sciences Center) of the Francisco Beltrão campus and facilitated by the agreement with PRONERA. The course was scheduled to start in the academic year of 2004. With Resolutions No. 090/2003-COU and 091/2003-COU of October 30, 2003, UNIOESTE’s Conselho Universitário (COU, University Council) approved the financial impact and sanctioned the creation of the course.

After approval in its internal instances, the University requested authorization from the Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (SETI, Department of Science, Technology and Higher Education) to operate the course. With that, through Official Letter 750 of December 5, 2003, SETI forwarded it to the Conselho Estadual de Educação do Estado do Paraná (CEE, State Council of Education of the State of Paraná) for analysis and ruling. The verification Commission instituted by the CEE on March 3, 2004, by Decree No. 04, 2004, issued a favorable opinion on the course in May of that year. The visit of the CEE Commission to UNIOESTE took place on March 22, 2004. In their report, the Commission suggested adjustments to the PPP and the need to provide some structural conditions for the course, especially the need to acquire a collection covering the bibliographies listed on the course’s PPP.

On May 7, 2004, based on the rapporteur’s favorable vote authorizing the course to operate as a pedagogical experiment, the CEE’s Câmara de Educação Superior (Higher Education Chamber) unanimously approved the rapporteur’s vote, followed by unanimous approval by the CEE Plenary. With the authorization for the course to operate through Resolution No. 076/2004-CEPE of May 18, 2004, UNIOESTE initiated procedures related to the course’s functioning concerning its program, teachers, teaching agenda for the curricular components, and candidates who would be allowed to participate in the course selection process.

As part of its Ruling, CEE requested from UNIOESTE the creation of a Working Group, which was instituted by the University through Resolution No. 077/2004-CEPE of May 18, 2004. Besides welcoming representatives from the University, the Working Group also comprised representatives from the municipality of Francisco Beltrão and the State Government of Paraná, the Comissão Regional de Atingidos por Barragens do Rio Iguaçu (CRABI, Regional Commission for People Affected by Dams of the Iguaçu River), the Associação de Estudos Orientação e Assistência Rural (ASSESOAR, Association of Studies, Orientation and Rural Assistance), and MST. The Working Group had the core task of monitoring the course implementation.

The prep stage for the selection process for the constitution of the course was held at ASSESOAR’s headquarters in Francisco Beltrão in June 2004. The Entrance Exam for the constitution of the class took place on the 24th and 25th of the same month at UNIOESTE’s Francisco Beltrão campus. The selection process involved writing an essay - in the form of a Living Memorial - and answering ten Portuguese questions, ten Mathematics questions, and five questions in the subjects of History, Geography, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, and Spanish. 55 candidates registered for the Entrance Exam, with 53 participating in both exam days. Six candidates failed the test on the publication of notice No. 011/2004 on June 30, which released the results of the Entrance Exam.

The academic activities of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE started in August 2004 with 46 students enrolled. It was perceived as a loss, as there had been a demand of approximately five hundred educators who needed training across various municipalities of Paraná. The course would meet 10% of the total demand estimated in its first edition (UNIOESTE, 2004, p. 6), however, it set off with four idle seats.

The characteristics of the course, as it is set in a rotational regime between university and community time, allowed for the public funding of accommodations, meals, and travel costs through PRONERA. With the provision of these resources, the course was made accessible to a heterogeneity of students from different areas of Paraná, one student from the state of São Paulo, three students from the state of Santa Catarina, and one from the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The class consisted of students coming from 26 peasant communities related to the Movimento de Atingidos por Barragens (MAB, Movement of People Affected by Dams), CRABI, MST, ASSESOAR, and Casas Familiares Rurais (CFR’s, Rural Family Houses).

There were twelve dropouts over the four years of the course for the most varied reasons, pervaded by the lack of interest in the area of activity, personal and economic difficulties that made it impossible for the students to carry on with their studies. There has been a transfer request, allowing for the insertion of a student into the course. Therefore, 35 students, 21 women, and 14 men completed the training offered in the first class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE.

From the analysis of the data referring to the students’ place of residence, as verified in the Living Memorials, at the beginning of the course, and through their links with the Social Movements, it seems that most of the graduating students of the Antonio Gramsci class had their insertion in MST Camps and Settlements, with 28 students presenting such background. As for the 2008 graduates, 15 students resided in Camps for rural workers fighting for land, 11 in Agrarian Reform Settlements, two in Resettlement Communities Affected by Dams, two had a connection to CFR’s, four resided in Family Farming Peasant Communities, and it was not possible for us to identify the place of residence of the remaining student.

While analyzing the PPP of the first class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE - Antônio Gramsci class - when dealing with the course’s purposes, it is clear that the configuration of this course constituted a new experience, with its own singular identity, “a new form of organization”, a singularity that is affirmed through the differentiation of its own subjects (UNIOESTE, 2004, p. 11). This subject specificity is already affirmed through the course admission as, in order to join the course, in addition to participating and being approved in the Entrance Exam, each student needed a referral from their Community or Social Movement - a Letter of Referral, to be presented to the Course Coordination. Based on this criterion, the students who participated in the Antonio Gramsci class had in their own insertion in Rural Communities one of the very elements that enabled them to join the course. This implied and intensified the political-pedagogical engagement in the development of the course, binding it to a rural and social project. This willingness to continually reaffirm the insertion in the Rural Communities was one of the axes of the training process initiated, being intrinsically linked to the structuring of the course under the rotational regime between university and community time.

Thus, since the beginning of the course, the students who participated in the Antonio Gramsci class for the Pedagogy of the Earth course maintained organic ties with Social Movements, Community Organizations, and Rural Communities, enhancing their insertion in the course and their Community based on effective participation in educational processes, whether through formal education, as is the case of Itinerant Schools8, Technical Courses in Agroecology Training Centers,9 and CFR’s, or even in non-formal processes, with their participation in cooperatives and community activities of formative character. According to the data produced in the present research, it was found that, at the beginning of the course, only seven students were not related to formal education processes.

The second class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE - the Nadja Krupskaya class10-, took place between 2009 and 2012, at the Cascavel campus. However, although this group took place during the period mentioned, its idealization took place still within the first group framework. From the evaluation of the results in exercise with the first class and the very social need for training of rural educators, in 2005, the Rural Popular Social Movements and teachers of the course started the claim for the opening of the second class of the course together with UNIOESTE’s and PRONERA internal instances.

The process that would culminate in the realization of the Nadja Krupskaya class was initiated with the public mobilization to enroll for the selection process, with an indication of it taking place in November 2006. However, due to the non-conclusion of the agreement between PRONERA and UNIOESTE, the Entrance Exam for the composition of the second class was postponed with no prediction of a new date. This led the Rural Popular Social Movements, through the students enrolled for the entrance exam, to occupy and organize a camp on the premises of UNIOESTE’s campus in Francisco Beltrão as a way to push for the implementation of the course. The camp at the University lasted approximately 45 days, with a series of training activities and negotiation processes, resulting in the achievement of the entrance exam disclosed through notice No. 110/2006-GRE of December 18, 2006.

Given the delay in signing the agreement, which only took place on December 31, 2008, and as a result of internal referrals to the University, the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators was then transferred to UNIOESTE’s campus in Cascavel. Thus, considering the time gap between the 2006 Entrance Exam, held at the Francisco Beltrão campus and the celebration of the agreement, a new Entrance Exam was carried out to complete the constitution of the class. The second entrance exam took place on April 1, 2009, in Cascavel and was published in Public Notice No. 030/2009-GRE of March 24, 2009. Still in March 2009, the University received the first financial transfer, providing the conditions for the beginning of the first stage of its second class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators. While analyzing the profile of the public that accessed and constituted the second Class of Pedagogy of the Earth in UNIOESTE, named Nadja Krupskaya class by the students themselves, it is clear that there is a youthful group, with ages ranging from 18 to 38. It is worth mentioning that in 2009, about 20% of the class was 18 years old. The graduated from this class consisted of 24 women and 11 men from 25 municipalities, being 23 from Paraná and two from Santa Catarina. Regarding the Communities and Social Movements connected to the students, the Nadja Krupskaya class was constituted by students from MST, the Movimento de Mulheres Camponesas (MMC, Movement of Peasant Women), and different rural contexts, being nineteen from Agrarian Reform Settlements, one from a Resettlement Community Affected by Dams, one from a Traditional Community, and fourteen from Camps for rural workers fighting for land.

An impacting data regarding the profile of the students who took part in the Nadja Krupskaya class was identified through the analysis of the Living Memorial that accompanied the Entrance Exam as part of the selection process. According to the data systematized from the Living Memorials, rural workers face a widespread denial of access to Higher Education, with 85% of the graduates of the Nadja Krupskaya class being the first of their families to have access to it.

Throughout the course, there have been 15 dropouts until 2010 as a result of different factors related to family issues, access, and permanence in the stages, regardless of all the possibilities provided by the rotational regime.

As for the students’ insertion, it was found from the research carried out that, until 2010, out of the 35 students in the Nadja Krupskaya class, 13 students had not constituted any form of insertion and professional performance within the school environment, eight of which contributed to non-formal training processes in the Community or Social Movements they participated. Thus, the students’ performance profile in 2010 can be characterized as follows: five worked as educators in Youth and Adult Education; 14 as educators at Itinerant Schools; two worked at Ciranda Infantil11; two at the Pedagogical Team at the Agroecology Training Center; three contributed to the organization of Youth Groups in their Communities; five worked in the Education and Training Sector of their respective Social Movement, and; four had no link or systematic insertion with any training activity.

The insertion in the course, in line with the formative intentionality proposed, which was established through the reciprocal connection between university and community time, allowed for the realization of experiences and insertion of the students who were part of the Nadja Krupskaya class in educational activities in the last two years of the course. The intentionality proposed by the course, anchored by the needs of their community of origin or other rural communities, allowed the students to outline an initial professional performance as pedagogues, mainly in educational processes aimed at Early Childhood, Youth, and Adult Education, or in Rural Schools in areas of Agrarian Reform, essentially in Itinerant Schools.

The third class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE, - namely the Anatolli Lunachaski class12, took place between 2013 and 2017, at the campus in Cascavel. The implementation of this third class of the Pedagogy of the Earth course at the University within the scope of PRONERA was approved by Resolution No. 201/2012-CEPE of November 29, 2012. The entrance exam for admission to the course, with the opening of fifty vacancies, had its result published on April 18, 2013, by Public Notice No. 043/2013-COGEPS. Out of the 118 candidates who registered for the Entrance Exam for the constitution of the third class, 49 candidates showed up on the day of the exams.

The PPP for the third class - namely, the Anatolli Lunachaski class - (UNIOESTE, 2013), supported by the experience with the two previous classes - Antonio Gramsci and Nadja Krupskaya - was approved by Resolution No. 115/2013-CEPE of May 23 of 2013. The course took four years, with a total workload of 3,464 hours carried out full-time, in a rotational regime in eight physical class stages. The course started on June 6, 2013, with 48 enrolled students, 40 women, and 8 men. As in the case of the Nadja Krupskaya class, this third group of Pedagogy of the Earth at UNIOESTE took place at the campus in Cascavel. The novelty for this new group was the building of housing quarters within UNIOESTE’s campus. During the four years, the Anatolli Lunachaski class had their accommodations allocated next to UNIOESTE’s Employees Community Center - Cascavel, attached to the campus’s sports court.

Another peculiarity of the Anatolli Lunachaski class was that its constitution, in addition to the selection through the Entrance Exam, also included the insertion of students via the Sistema de Seleção Unificada (SISU, Unified Selection System), being that, out of the 48 students participating in the class, 12 joined the University through SISU. Yet another particularity regarding the effectiveness of the class, there was the financial management process of the course for the third class, with resources transferred by PRONERA to provide financial support for travels, accommodation, and meals during the university hours, made possible through students’ scholarships. This required a greater commitment from students in the collective management of the course, otherwise many would be harmed if each student applied the money from the scholarships for personal interests, for example. For three years, the class ordered food from restaurants close to UNIOESTE. With the implementation of the University Restaurant at the campus in Cascavel on the last year of the course, they started having meals subsidized by the policy implemented by the University, with the structuring and operation of the University Restaurant, which included all students on campus.

The students who took part in the Anatolli Lunachaski class had links with the following Social Movements: MST, MMC, Rural Youth Ministry (PJR), Movimento de Libertação dos Sem Terra (MLST, Liberation Movement for the Landless Rural Workers), and Movimento Nacional de Luta pela Moradia (MNLM, National Movement for Housing). This way not only did the students who joined the course do it as individuals in the formative process, but also brought a history of struggle with them, whether for land, education, health, housing, or other issues and claims by their Social Movements. These students’ origins are also diverse, with 44 of them coming from Paraná, one from the state of São Paulo, one from the state of Santa Catarina, and two from the state of Espírito Santo.

Based on the analysis of data concerning the profile of the students at the beginning of the course, there is a panorama that expresses that, out of the 48 students who participated in the class from the beginning, a total of 26 were connected to Camps for rural workers fighting for land and Agrarian Reform Settlements organized by MST. Throughout the course, there were 27 dropouts that, as happened with the other classes, were a result of the lack of interest in the area of activity, issues of personal, familial, or economic nature, as well as the difficulties of access and permanence in the stages, elements that made it impossible to complete the course. Out of the 21 alumni, there were 18 women and three men from sixteen rural communities located in four different states, as a student moved to the state of Mato Grosso do Sul during the course. Among the graduates, 11 resided in Agrarian Reform Settlements, eight in Camps for rural workers fighting for land, one was Resettled into a Community Affected by a Dam, and it was not possible for us to identify the place of residence of the last student, but she was related to an Agricultural Family House. With this panorama as a reference, the interface of Higher and Rural Education configured through the relationship between University, Rural Popular Social Movements, and PRONERA stands out as a founding element in the insertion of popular sectors into the Public University and the design of a public policy on Rural Education that meets the historical demands of the rural workers.

The Licentiate degree in Rural Education, which enabled the assembly of a class at UNIOESTE, was held between 2010 and 2014. This was the second specific undergraduate course for training rural educators offered by the University. According to the PPP of the course (UNIOESTE, 2008), the training provided by the Licentiate degree in Rural Education at UNIOESTE aimed to train educators to work in the final years of Elementary School and High School, enabling them to work in the areas of knowledge of Agrarian Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Mathematics. This class of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education course was named Paulo Freire by its students13.

The Licentiate degree in Rural Education at UNIOESTE was carried out as of Public Notice No. 2, of April 23, 2008, which aimed to select projects from Public Institutions of Higher Education for PROCAMPO. The proposal presented by UNIOESTE, aimed at offering thirty positions for qualification in the areas of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, and thirty for the area of Agrarian Sciences, according to the conditions laid down by PROCAMPO’s notice, had its approval disclosed by notice No. 3 of October 6, 2008. The partnership between MEC and UNIOESTE, which allowed for the transferring of funds for the course, took place under Agreement No. 742005/2008 of December 31, 2008. However, considering the bureaucratic difficulties related to the transferring of financial resources, the course could not be initiated in 2008.

In 2009, concurrently with the effort for guaranteeing financial resources from MEC, together with the Rural Popular Social Movements, UNIOESTE demanded authorization to run the course from the Government of Paraná. This achievement was enforced through Decree No. 6,357 of February 26, 2010, which declared the Governor’s authorization for the beginning of the course.

As happened with the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators, the selection for the composition of the class of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education at UNIOESTE included the completion of an Entrance Exam, with tests in two dimensions. The first focused on analyzing and proving the candidates’ general knowledge, while the second consisted of the elaboration of an essay. The tests took place on March 21, 2010. The test was comprised of objective, multiple-choice questions. The questions were focused on High School general contents, including Biology, Physics, Geography, History, Spanish, Chemistry, Portuguese, and Mathematics. The elaboration of the essay consisted in the production of a Living Memorial focused on their relationship with Rural Education and took into consideration the organization and structure of the text, as well as the correct use of orthographic and grammatical resources.

Considering the processes that UNIOESTE was already carrying out with the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators, for the enrollment in the Entrance Exam for the Licentiate degree in Rural Education, the candidates had also to present a Letter of Referral for insertion into the course. 159 candidates enrolled for the Entrance Exam for the Licentiate degree in Rural Education at UNIOESTE, being 45 candidates for the qualification in Agrarian Sciences, and 114 for Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

According to the result of the Entrance Exam published by edict No. 074/2010-GRE of April 5, 2010, for the Licentiate degree in Rural Education at UNIOESTE, the vast majority of the students integrating the Paulo Freire class were somehow related to educational activities within formal or non-formal spaces. The Paulo Freire class initially consisted of sixty students, of whom 46 completed the course, being 29 women and 17 men. The students who had graduated from the Licentiate degree in Rural Education at UNIOESTE, in their totality, maintained links with 36 Rural Communities located in 29 municipalities in five Brazilian states, of which 31 were from Paraná, seven from Espírito Santo, four from Mato Grosso do Sul, two from Santa Catarina, and two from Tocantins.

The participation of students linked to seven Social Movements was registered in Paulo Freire class. Out of the students who started the course, 32 had ties with the MST, six with the PJR, one with the MNLM, two with the MAB, two with the MMC, two with the MLST, and one student was linked to the Movimento dos Pequenos Agricultores (MPA, Small Farmers Movement).

Out of the 46 who completed their course at UNIOESTE, obtaining a Licentiate degree in Rural Education, 26 graduated in the area of Agrarian Sciences, and 20 of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. Seven women and seven men did not complete the course for different reasons. Eleven maintained a link with the MST and three with the MNLM. The highest rate of non-completion of the course was among students in the area of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

According to Verdério (2018), the non-adherence to the area of qualification knowledge, linked to the needs of permanence, especially in university time periods, together with the fragile level of connection of dropouts with Social Movements, as well as the weakness in insertion in educational practices developed in Rural Communities, were the main determining reasons for the non-completion of the course.

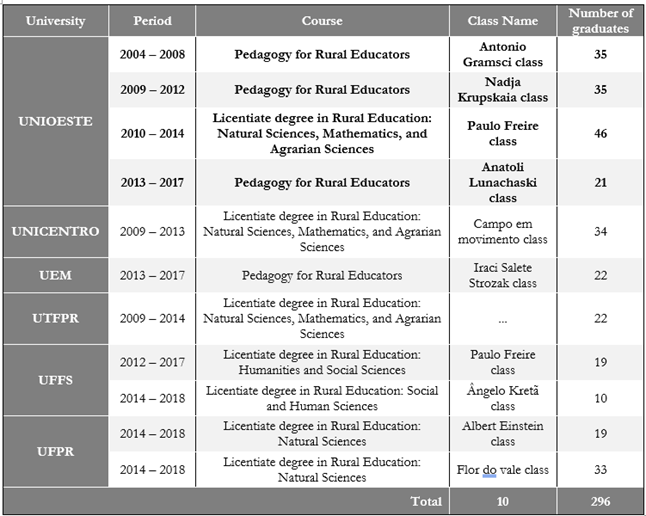

According to Chart 1, when considering the realization of undergraduate courses in the rotational regime for the training of rural educators, there is a direct relationship between the experiences analyzed and the process of constitution and affirmation of the public policies for Rural Education, above all, the effectiveness of PRONERA and PROCAMPO in the insertion and permanence of rural workers in Higher Education, which, in turn, is supported by its interface with Rural Education.

SOURCE: Authors’ organization (2019).

Chart 1: Graduating undergraduate alternating courses Paraná 2004 - 2019

UNIOESTE, as a pioneering Public University and a protagonist, together with the Rural Popular Social Movements in the state of Paraná, in offering rotational undergraduate courses, is also a fertile space in the training of rural educators. This is demonstrated in Chart 1, as out of the 296 graduates from undergraduate courses for the training of rural educators organized in rotational regime concluded in Paraná by the year 2019, 137 attended courses at UNIOESTE. In other words, the percentage of rural educators graduating from Rural Education courses at UNIOESTE in relation to the total number of graduates from courses across Paraná is higher than 46%.

Considering the elements that supported the results of the experience related to the training of rural educators at UNIOESTE, we can affirm the effectiveness of the actions initiated in the context of the struggle for Rural Education in Brazil. Thus, the interface between Higher and Rural Education, enhanced by PRONERA and PROCAMPO, has produced important achievements in terms of access and permanence of the popular classes in Brazilian public universities. This is reflected in the experience carried out at UNIOESTE, which, between 2004 and 2017, enabled the insertion, permanence, and completion of training processes in graduation for 137 subjects organically linked to rural workers and the educational practices that concern them.

THE ACADEMIC-SCIENTIFIC PRODUCTION OF STUDENTS IN ROTATIONAL COURSES AT UNIOESTE IN THE INTERFACE OF HIGHER AND RURAL EDUCATION

Considering the profile of the 137 graduates from the undergraduate courses for the training of rural educators in a rotational regime at UNIOESTE, paying special attention to their links with the Communities and with the Social Movements, and from the analysis of their Undergraduate Thesis, as per the synthesis presented in Chart 2, it is clear that the monographs prepared by all students pervaded issues related to two major theme groups: 1) Formal Educational Practices - School and Rural Education and 2) Non-Formal Educational Practices - Social Movements and Rural Education. Given the diversity of topics covered and the scope of the studies that supported the elaboration of the monographs analyzed, the two theme aggregating groups were split into 32 theme subgroups.

SOURCE: Authors’ organization (2019).

Chart 2: Themes of the monographs elaborated in the training courses for rural educators at UNIOESTE 2004 - 2017

In line with the distribution of monographs among the two groups and the 32 theme subgroups listed in Chart 2, there is a strong adherence to studies oriented towards Formal Educational Practices - School and Rural Education or, in other words, on the issue of school education itself. The number of works in this group amassed 93 monographs among the four classes. In turn, studies focused on Non-Formal Educational Practices - Social Movements and Rural Education, even if at a lower rate, also had an impact on the works of the four classes, resulting in a total of 44 monographs.

When considering the three classes of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators - Antonio Gramsci, Nadja Krupskaia, and Anatolli Lunachaski classes -, by relating the objects of study and the spaces of insertion and performance of the student-researchers verified at the initial moment of the courses and in the Living Memorials, also concerning their elaborations and Undergraduate Thesis titles, we can verify that, out of the 68 works that constituted the Theme Group of Formal Educational Practices - School and Rural Education, 54 obviously express the relationship between the student-researchers’ origins and the chosen study objects. This link is also evident in the Theme Group for Non-Formal Educational Practices - Social Movements and Rural Education, since out of the 23 studies analyzed, 19 approach the relationship between the insertion of student-researchers and the objects researched. In the context of the Licentiate degree in Education - Paulo Freire class, this was the subject of eighteen out of the 25 works gathered in the Theme Group of Formal Educational Practices - School and Rural Education; a reciprocal relationship is evidenced, expressed, above all, through the connection and insertion of student-researchers into the processes and spaces that supported their respective objects of study. Likewise, regarding the Licentiate degree in Rural Education, seventeen of the 21 works that are linked to the Theme Group Non-Formal Educational Practices - Social Movements and Rural Education cover the relationship between the objects of study and the insertion and performance of student-researchers in spaces constituted as locus and that sustained their research objects.

Thus, it appears that 108 of the 137 monograph works prepared by students of the Rural Education courses offered at UNIOESTE express the reciprocal relationship between the origin and the insertion of the student-researchers and their objects of study through the textual record of the actual works. As an example of this relationship, three monographic works that emphasize this relationship are highlighted. In the case of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators, the work entitled “Reading and writing practices: a study at Escola Rural Municipal Herbert de Souza”, by a student from the Antonio Gramsci class, stands out. In it, the author strikingly records their bond with the object of study selected, either through acting in Youth and Adult, Early Childhood, or Elementary Education, turning to the difficulties related to the process of reading and writing in such contexts. When considering this trajectory as a rural educator, the student-researcher points out in this work that “[...] it was clear that I could never forget them, because I realized that, in my career as an educator, such things should not happen. So I started acting in a way that awakened the child’s will to learn how to read and write” (MENDES, 2008, p. 6). Written by a student in the Nadja Krupskaya class, the research entitled “Disabled people: possibilities and challenges of their insertion into the scholar routine of Zumbi dos Palmares Itinerant School” stands out. In it, the author registers through elaboration that the experience as an educator at the school researched allowed for the identification of the difficulty of access for students with special educational needs (RODRIGUES, 2012), with this subject being selected as the research theme for their Undergraduate Thesis. Paulo Freire class of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education, the work that stands out is titled “The relationship between work and education in the pedagogical practice at the CEFFA Bley”, in which the student-researcher registers that their link with the researched reality “[...] made a relationship beyond a contractual formality possible while also providing a militant relationship, committed to contributing to the development of this experience.” (FAVERO, 2014, p. 8).

In this sense, the comprehension that the subjects researched at the Rural Education courses carried out through PRONERA and PROCAMPO at UNIOESTE maintained connections with concrete problems experienced within the communities where the students are inserted. This data highlights the contribution of the training courses for rural educators held at UNIOESTE in the perspective of advancing the education of rural workers, culminating in the training of professionals with both political commitment and technical competence, capable of contributing to their Communities with a professional performance in the sense of promoting and qualifying the educational processes initiated.

Thus, considering the research processes initiated by students of the Pedagogy of the Earth and Licentiate degree in Rural Education courses at UNIOESTE, as well as the results of the monographs analyzed, the organic link between the researched objects and the existing challenges to advance the educational work within Rural Communities stands in the spotlight. This element stands out as a differential produced collectively in the education of the rural educator, rescuing and affirming the social commitment of the researcher and the research process, insofar as it offers a socially referenced return to the Community life.

FINAL THOUGHTS

By attributing materiality to the Higher and Rural Education interface through the inclusion and permanence of rural workers in undergraduate courses organized with this intention, the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators and Licentiate degree in Rural Education courses at UNIOESTE bring research themes relevant for students in training, as well as the Communities and Popular Social Movements of the rural to the internal environment of the University and academic-scientific production. This becomes evident as the research problems generated reflect questions posed by the reality of the insertion and performance of student-researchers who, even before joining the undergraduate course, act themselves as rural educators, whether within formal spaces or non-formal education programs immersed in the rural reality.

Thus, considering the interface between Higher and Rural Education in training courses for rural educators in a rotational regime implies a connection with the materiality of the background of the subjects of the struggle for Rural Education considering the advances, challenges, and implications that it creates within the Public University. The inclusion and permanence of popular classes in Higher Education in its interface with Rural Education carries out the potential to problematize, systematize, and understand reality, with a view to expanding access to knowledge and, at the same time, inquires about the social role of the University, as it is pushed to offer a socially qualified return in the face of the contradictions and the issues afflicting the rural workers’ existence, with an emphasis to their right to education at all levels.

In this way, rotational undergraduate courses carried out through PRONERA and PROCAMPO contribute to the achievement of a new meaning to the social function of the University linked to a popular character and the democratization of Higher Education in three complementary dimensions: access (MARTINS, 2012), content, and form (FRIGOTTO, 2011). The first of the dimensions concerns access, insofar as they expand positions for students from the working class, historically excluded from this educational level. The second is linked to the content, since, through the materiality of the origin of the people subject to the struggle for land and Rural Education, problematizations and themes produced and demanded from the contradictions of the Brazilian rural areas are introduced at the University. And last but not least, there is the dimension of form, which, by constituting and affirming the rotational regime as a concrete possibility for the access and permanence of rural workers at the University, they produce a curricular organization that supports training processes articulated in two spans of time that are intertwined, the Rural Community of insertion and the University, the latter, working as a space to be intentionally and collectively occupied by those subjects who are collectively produced within their organizations and class struggles; the rural workers.

REFERENCES

ANDRADE, M. R.; DI PIERRO, M. C. A construção de uma política de Educação na Reforma Agrária. In: ANDRADE, M. R. et al. (Org.). A Educação na Reforma Agrária em Perspectiva: uma avaliação do Programa Nacional de Educação na Reforma Agrária. São Paulo: Ação Educativa; Brasília: PRONERA, 2004. p. 19-35. [ Links ]

APEC - ARTICULAÇÃO PARANAENSE POR UMA EDUCAÇÃO DO CAMPO. Carta de Porto Barreiro. IIConferência Estadual por uma Educação Básica do Campo, Porto Barreiro/PR, 2 a 5 de novembro de 2000. In: MANCHOPE, E. C. P.; LISBOA, E.; HENRIQUES, M. J. R. (Orgs.) Articulação Paranaense: “Por uma Educação do Campo”. Temáticas abordadas na IIConferência Estadual. Porto Barreiro: APEC, 2000. (Caderno 2, Articulação Paranaense por uma Educação do Campo). [ Links ]

BAHNIUK, C.; CAMINI, I. Escola Itinerante. In: CALDART, R. S. et al. (orgs.). Dicionário da Educação do Campo. Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo: EPSJV, Expressão Popular, 2012. p. 331-336. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização e Diversidade. Edital nº 2, de 23 de abril de 2008. 2008. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/edital_procampo.pdf . Acesso em: 12 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conheça as Universidades participantes do PROCAMPO 2010. 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=6463-procampo-2010-tabela&category_slug=agosto-2010-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em: 12 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário. Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária. Manual de Operações do PRONERA. Aprovado pela Portaria/INCRA/P Nº 19, de 15.01.2016. Brasília-DF. 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.incra.gov.br/sites/default/files/uploads/reforma-agraria/projetos-e-programas/pronera/manual_pronera_-_18.01.16.pdf . Acesso em: 22 fev. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Portaria nº 86, de 1º de fevereiro de 2013: Programa Nacional de Educação do Campo - PRONACAMPO, 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://pronacampo.mec.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 14 set. 2017. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, J. C. de et al. Vozes da Educação do Campo na interface com a Unioeste - Ensino Superior: inclusão e permanências dos Setores Populares. Cascavel: TV IMAGO, 2019. (Coletânea de Vídeos). Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCw5WgyTakBLJwu5QGjDvLwg. [ Links ]

CHAUÍ, M. Escritos sobre a Universidade. São Paulo: Ed. UNESP, 2001. [ Links ]

FAVERO, C. A relação trabalho e educação na prática pedagogica do CEFFA do Bley. 2014. 74 f. (Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso) - Curso de Pedagogia para Educadores do Campo da Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná, Francisco Beltrão, 2014. [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, G. Projeto societário contra-hegemônico e educação do campo; desafios de conteúdo, método e forma. In: MUNARIN, A. et al. (orgs). Educação do campo: reflexões e perspectivas. 2. ed. Florianópolis: Insular, 2011. [ Links ]

GHEDINI, M. C. et al. Formação de Educadores do Campo: interface entre a Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná e os Movimentos Sociais Populares do Campo. In: LOSS, A. S.; VAIN, P. D. Ensino Superior: palavras, pesquisas e reflexões entre movimentos internacionais. Curitiba: CRV, 2018. p. 273-295. [ Links ]

HORÁCIO, A. de S. Licenciatura em Educação do Campo e Movimentos Sociais: análise do curso da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. 2015. 156 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Viçosa - UFV, Viçosa/MG, 2015. [ Links ]

IPEA - INSTITUTO DE PESQUISA ECONÔMICA APLICADA. II PNERA- Relatório da II Pesquisa Nacional sobre a Educação na Reforma Agrária. Brasília, DF: IPEA, 2015. [ Links ]

LEAL, A. A. et al. Cartografia das Licenciaturas em Educação do Campo no Brasil: expansão e institucionalização. In: MOLINA, M. C.; MARTINS, M. F. A. (orgs.). Formação de formadores: reflexões sobre as experiências da Licenciatura em Educação do Campo no Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2019. p. 39-53. [ Links ]

LOSS, A. S. et al. (Orgs.). Ensino Superior “em movimento”: aproximações da inclusão pelos princípios da educação popular. Curitiba: CRV , 2018. [ Links ]

LOSS, A. S.; VAIN, P. D. (Orgs.). Ensino Superior e inclusão: palavras, pesquisas e reflexões entre movimentos internacionais. Curitiba: CRV , 2018. [ Links ]

MARTINS, J. F. A Pedagogia da Terra: os Sujeitos do Campo e do Ensino Superior. Revista Educação, Sociedade & Culturas, nº 36, 2012. p. 103-119. [ Links ]

MEC - MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Secretaria de Educação Superior. Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica. Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização e Diversidade. Coordenação Geral de Educação do Campo. Minuta Original Licenciatura (Plena) em Educação do Campo. 2006. In: MOLINA, M. C.; SÁ, L. M. (Orgs.). Licenciaturas em Educação do Campo: registros e reflexões das experiências-piloto (UFMG; UnB; UFBA e UFS). Belo Horizonte: Autêntica , 2011. (Coleção Caminhos da Educação do Campo, 5). p. 357-364. [ Links ]

MENDES, E. P. Práticas de leitura e escrita: um estudo na Escola Rural Municipal Herbert de Souza. 2008. 41 f. (Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso) - Curso de Pedagogia para Educadores do Campo da Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná, Francisco Beltrão, 2008. [ Links ]

MOLINA, M. C.; SÁ, L. M. (Orgs.). Licenciaturas em Educação do Campo: registros e reflexões a partir das experiências piloto. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica , 2011. (Coleção Caminhos da Educação do Campo, 5). [ Links ]

MOLINA, M. C. et al. A produção do conhecimento na licenciatura em Educação do Campo: desafios e possibilidades para o fortalecimento da educação do campo. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 24, 2019. Diponível em: Diponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/v24/1809-449X-rbedu-24-e240051.pdf . Acesso em:20 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

PINTO, Á. V. A questão da Universidade. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 1994. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, E. K. Sujeitos com deficiência: possibilidades e desafios de sua inserção no cotidiano escolar da Escola itinerante Zumbi dos Palmares. 2012. 56 f. (Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso) - Curso de Pedagogia para Educadores do Campo da Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná, Cascavel, 2012. [ Links ]

RAMOS, M. N. et al. Referências para uma política nacional de Educação do Campo. Brasília: Secretaria de Educação Média e Tecnológica, Grupo Permanente de Trabalho de Educação do Campo, 2004. [ Links ]

ROSSETTO, E. R. A; SILVA, F. T. de. Ciranda Infantil. In: CALDART, R. S. et al. (orgs.). Dicionário da Educação do Campo. Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo: EPSJV, Expressão Popular , 2012. p. 125-127. [ Links ]

SANTOS, C. A. dos (Org.). Educação do Campo e políticas públicas no Brasil: o protagonismo dos movimentos sociais do campo na instituição de políticas públicas e a Licenciatura em Educação do Campo na UnB. Brasília: Líber Livro; Faculdade de Educação/Universidade de Brasília, 2012. [ Links ]

UNIOESTE. Resolução n 083/2004-CEPE. Aprova o Projeto Político Pedagógico do Curso de Pedagogia para Educadores do Campo, do Centro de Ciências Humanas - Campus de Francisco Beltrão. Cascavel, PR: Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná, 2004. [ Links ]

UNIOESTE. Resolução nº 050/2009-CEPE: Projeto Político-Pedagógico do Curso Especial de Licenciatura em Educação do Campo. Cascavel, PR: Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná , 2009. [ Links ]

UNIOESTE. Projeto Político Pedagógico do Curso de Pedagogia para Educadores do Campo. Cascavel, PR: Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná , 2013. [ Links ]

UNIOESTE. Boletins de Dados. 2019. Disponíveis em: Disponíveis em: https://www5.unioeste.br/portalunioeste/proplanejamento/dir-de-avaliacao-institucional/divisao-de-informacao/boletin-de-dados . Acesso em: 03 out. 2019. [ Links ]

VERDÉRIO, A. A pesquisa em processos formativos de professores do campo: a Licenciatura em Educação do Campo na UNIOESTE (2010 - 2014). 2018. 362 f. Tese (Doutorado) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educaçãoda Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2018. [ Links ]

6The experiments were carried out following an invitation from MEC to four Federal Universities, namely: Universidade de Brasília (UnB), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA) and Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS). According to Molina and Sá (2011), this action enabled and resulted in PROCAMPO’s own configuration.

8Itinerant Schools are “[...] schools located in camps kept by the MST, a social movement based on the demand for access to land, articulating it to a project for social transformation”. (BAHNIUK; CAMINI, 2012, p. 331).

9Training Centers are spaces located in settlements or regions that aim at the professional and cultural development, as well as the schooling of the settlers and campers. They house various training activities within the scope of professional technical training in areas of interest to the population in areas of agrarian reform, such as technical courses in agroecology and community health, which are either duly legalized or applied in partnership with other educational institutions, as well as courses aimed at political-ideological formation.

10Nadja Krupskaya (1869 - 1939). Educator and leader of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Integrated the People’s Commissariat for Education during the Soviet revolutionary process. As an honor to her legacy, her name was given to the second class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE.

11“Ciranda Infantil is an educational space for MST children organized by MST and maintained by cooperatives, training centers, and by MST itself within its settlements and camps” (ROSSETTO; SILVA, 2012, p 127).

12Anatolli Lunachaski (1875 - 1933). Playwright, literary critic, and leader of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Integrated the People’s Commissariat for Education during the Soviet revolutionary process. As an honor to his legacy, his name was given to the third class of the Pedagogy course for Rural Educators at UNIOESTE.

13Paulo Freire (1921 - 1997). Brazilian educator, pedagogue, and philosopher. Patron of Brazilian education. As an honor to his legacy, his name was given a class of the Licentiate degree in Rural Education course at UNIOESTE.

5The translation of this article into English was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES-Brasil.

Received: October 03, 2019; Accepted: January 07, 2021

texto em

texto em