Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 13-Abr-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698229231

ARTICLE

ORGANIZATION OF PEDAGOGICAL WORK IN RURAL SCHOOL OF THE STATE OF MATO GROSSO AT THE YEARS 1980 AND 1990

1Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso (UEMAT). Cáceres, MT, Brazil. ilma.ferreirmachado@gmail.com

2Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso (UEMAT). Cáceres, MT, Brazil. logentil2@gmail.com

This article seeks to analyze how the pedagogical work in rural school of the state of Mato Grosso was configured in the 1980s and 1990s. This study is based on the critical-dialectical approach and the qualitative research, having as instrument the semi-structured interview with 23 teachers. The results indicate that the schools did not have a defined pedagogical proposal. The pedagogical work was based on the orientations of the departments of education and on the teachers’ school experiences; although education in the period was focused on instructional aspects, some teachers tried to perform humanized teaching based on collaboration with students and parents. From the 1990s, pedagogical work started to take place in a more systematic and critical way, seeking to incorporate research as a pedagogical principle and the reality of the rural world as a living laboratory and as factor for the promotion of the theory-practice relationship and learning. We conclude that the pedagogical work of the rural school, during this period, is marked by enormous challenges in terms of the very existence of these schools, the guarantee of rural workers’ access to school education and the precarious working conditions - physical structure, teaching resources and professional recognition and training. Brazil’s democratization process opens the way to think public policies for rural education, which grew in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Keywords: rural area education; pedagogical work; Mato Grosso

Busca-se, neste texto, analisar como se configurava o trabalho pedagógico em escolas do campo do estado de Mato Grosso, nas décadas de 1980 e 1990. O estudo pauta-se na abordagem crítico-dialética e na pesquisa qualitativa, tendo como instrumento a entrevista semiestruturada, realizada com 23 professores. Os resultados apontam que as escolas não tinham uma proposta pedagógica definida; o trabalho pedagógico baseava-se nas orientações das secretarias de educação e nas experiências escolares dos professores; embora a educação no período em questão estivesse centrada nos aspectos instrucionais, alguns professores tentavam realizar um ensino humanizado, pautado na colaboração com alunos e pais/mães. A partir dos anos de 1990, o trabalho pedagógico passa a ocorrer de forma mais sistematizada e crítica, buscando incorporar a pesquisa como princípio pedagógico e a realidade do campo como laboratório vivo e fator de promoção da relação teoria-prática e da aprendizagem. Conclui-se que o trabalho pedagógico das escolas do campo, no período aqui recortado, é marcado por enormes desafios em termos da própria existência dessas escolas, da garantia de acesso dos trabalhadores rurais à educação escolar e da precariedade das condições de trabalho - estrutura física, recursos didáticos e formação/reconhecimento profissional. O processo de democratização do Brasil abre caminhos para se pensar em políticas públicas para a educação do campo, o que se intensificará no fim dos anos de 1990 e início dos anos 2000.

Palavras-chave: educação do campo; trabalho pedagógico; Mato Grosso

Este artículo busca analizar cómo se configuró el trabajo pedagógico en las escuelas rurales del estado de Mato Grosso en las décadas de 1980 y 1990. El estudio se basa en el enfoque crítico-dialéctico y la investigación cualitativa, teniendo como instrumento la entrevista semiestructurada, realizada a 23 docentes. Los resultados indican que las escuelas no tenían una propuesta pedagógica definida; el trabajo pedagógico se basaba en las orientaciones de las secretarías de educación y en las experiencias escolares de los docentes; aunque la educación en el período en cuestión se centró en aspectos de instrucción, algunos maestros trataron de llevar a cabo una enseñanza humanizada, cimentada en la colaboración con estudiantes y padres de familia. A partir de la década de 1990, el trabajo pedagógico se realizó de una manera más sistemática y crítica, buscando incorporar la investigación como un principio pedagógico y la realidad del campo como laboratorio vivo y factor de promoción de la relación teoría-práctica con el aprendizaje. Se concluye que el trabajo pedagógico de las escuelas rurales durante este lapso de tiempo está marcado por enormes desafíos para la existencia misma de estas escuelas, la falta de garantía para el acceso de los trabajadores rurales a la educación escolar, precarias condiciones de trabajo, estructuras físicas deficientes, escasos recursos didácticos, al igual que formación y reconocimiento profesional. El proceso de democratización del Brasil abre caminos para pensar políticas públicas para la educación en contextos rurales, lo que se intensificará a finales de la década de 1990 y principios de la década de 2000.

Palabras clave: educación en contextos rurales; trabajo pedagógico; Mato Grosso

INTRODUCTION

School education in the countryside in Brazil dates back to the second reign and its historical development follows the evolution of the country's socioagrarian structures (CALAZANS, 1993), marked by the concentration of land and wealth. This explains, in large part, why such education was never a concern of the rulers and the agrarian elite. The advent of the coffee monoculture, combined with the end of slavery provoked a small impulse in this area, showing the need for more specialized workers, corresponding to the qualification desired by large landowners.

The movement known as pedagogical ruralism, in the 1930s, advocated a "typical rural school", with curricula and methods suited to regional peculiarities. Praised as an alternative to traditional educational proposals, in reality this movement had as its political-ideological foundation the adjustment or rooting of man to the countryside, in order to meet the country's rural vocation and "free" it from urban swelling and the possible social problems brought about by this phenomenon (CALAZANS, 1993). In later periods, European and North American educational projects were imported to the Brazilian countryside, emphasizing technical training articulated to the principles of the capitalist market. Many projects were implemented by the private initiative or by the state, always in an attempt to submit the countryside to the logic of capital (VENDRAMINI, 2009; CALDART, 2010).

Until the last decades of the 20th century, the educational proposals dealt with the simple transposition of an urban educational model to the countryside, in reality preconizing its end, given the accelerated urban development driven by technological advances, the expansion of agribusiness (MOLINA; FERNANDES, 2004) and the globalized economy. There was an intention to limit the education of rural subjects to practice for practice's sake, not prioritizing scientific and technological knowledge, since it was understood that the peasant's logic of production and work should be eliminated (CALDART, 2010).

Research on education in the countryside (VENDRAMINI, 2009; PERIPOLLI, 2010; MOLINA; ANTUNES-ROCHA, 2014; SOUZA, 2018) has been conducted, but there are few studies on pedagogical processes in field schools in Mato Grosso in the 1980s and 1990s. In light of this, we formulated the following research question: How and under what conditions have been the organization of the pedagogical work of field schools in the 1980s and 1990s in the state of Mato Grosso? Thus, our main objective is to analyze how the pedagogical work was configured in field schools in the state of Mato Grosso within this period.

According to Rocha (2010), in the 1980s there were 254,586 children in the mandatory school age group in the state of Mato Grosso, but 80,103 were out of school, because the 1,844 school units were not enough to meet the demand. In 2017, according to data from the School Census, the educational system in this state served 878,515 students, considering the public and private networks. Mato Grosso has an area of 903,546.42 km² with enormous regional differences and uneven territorial occupation. In 1978, it had 2,020,581 inhabitants (ROCHA, 2010) and, 40 years later, a total population of 3,441,998 inhabitants (IBGE, 2018). The demographic density is 3.3 inhabitants per km², with 81.9% of the population living in the urban area and 18.1% in the rural area4.

We refer this work to the critical-dialectical approach and qualitative research (GAMBOA, 2012). We start from the assumption that understanding reality implies a rigorous analysis of the objective and subjective dimensions that it contains and the contradictions that permeate it, not allowing mechanical and closed definitions about a given phenomenon, but provisional syntheses and subject to new questionings. Thus, we consider "the real individuals, their action and their material conditions of life, both those they encountered and those they produced by their own action" (MARX, 2009, p. 23).

In this research we analyzed both documents about educational policies related to field education in one way or another in the state of Mato Grosso and semi-structured interviews5 with teachers of field education in the 1980s and 1990s. In this text, we analyzed only the data obtained through interviews about the organization of the pedagogical work, its principles, methods, material and didactic resources, the relationship among the people involved in the educational process, and the articulation with political-administrative instances. we organized the data into four intertwined dimensions: working conditions, orientation and supervision of pedagogical work, educational principles and foundations, and organization of the pedagogical work. the teacher training is a "transversal" axis into the discussion on the organization of the pedagogical work.

The subjects of this research were 23 teachers of field education in the 1980s and 1990s, from five mesoregions (from this point on called just regions) of the state: north, center-south, southeast, southwest, and northeast. These teachers were identified and located either by consulting the archives of the State Secretariat of Education of Mato Grosso (Seduc/MT) or indication of people involved with field education. In the Northeast region, we interviewed educators from the municipalities of São Félix Araguaia and Cascalheira; in the Southwest region, educators from Mirassol D'Oeste and Tangará da Serra; in the Center-South region, educators from Cuiabá and Cáceres; in the North region: educators from Comodoro, Sinop and Nova Canaã; and in the Southeast region, educators from Rondonópolis and São José do Povo. We interviewed five teachers in each region, except in the center-south region, where only three participated;. The interviewees were identified by the initial letters of their names, followed by the region and year of the interview. They lasted from one to two hours, in a single session with each participant, and were recorded and transcribed. About 80% of the interviewees were female, including the teacher trainers. The time they have worked in field education varies from one to 20 years, with three female teachers having worked in the 1970s and four only in the 1990s. Two teachers were retired, but continued to work in social projects on a voluntary basis.

WORKING CONDITIONS

In this dimension, we highlight aspects such as infrastructure, conditions of access to school and teacher training.

In the 1980s elementary education level prevailed among interviewes, as 11 out of the 19 teachers held such degree. In the 1990s, training in high school predominated and by the end of that decade training in higher education emerged among them. According to Rocha (2010, p.30), "in 1979, only 138 out of the 2,217 teachers working in rural areas in Mato Grosso, had teaching qualification". In the 1980s, there were cases of people who were not even the minimum age allowed (18 years) for hiring, as reported by a teacher from the southeast region: “I worked with a colleague who took classes, but I was the one who went to school” (Fa.SE, 2014); and another from the northeast region: “At the time, there were other girls who also entered very young because there was no older people available” (Li.NE, 2015).

The profile of the interviewed teachers indicate the almost non-existent attention paid to the training of teachers in field schools in Brazil until the end of the 20th century. The interviewees did not point out the existence of specific policies for field education in that period, what existed “was for the whole network, there was nothing just for the countryside.” (Lu.SO, 2014). Therefore, the educators of this type of education were “served” by generalist policies: “it seemed that it was all from the urban area, there was not much difference. So, field education was never treated with a different look, I never noticed it ”(Ma.N, 2015). Training, when it took place, was thought of in a general way, "for" teachers, and not with them, without distinction between urban and rural. We did not identify the collective movement to plan the education/training of workers based on their social, political and human interests, or the struggle for a specific right within the larger struggle for rights (CALDART, 2015).

For a long time, teaching was an occupation associated with the idea of mission in Brazil and this meant there was no great concern with training, especially for the initial years of schooling. Across the country, teachers in this phase and especially those in the urban area were trained mostly until high school leve, in the so-called “Normal Course” (aimed at teaching). Law 4.024/61 allowed the training of teachers at middle, high shool and university levels, differentiating only the nomenclature and the level of performance. Those with middle school level were called primary school regents; the ones with school level were called primary school teachers; and those who obtained a university training became high school teachers.

According to some interviewees, given the difficulties of life in the rural area at that time, it became more complicated to be a teacher in field schools.

I started my activism (education, right?) in 82-83 in Alto Araguaia [...] I remember that the bus left us on the road and then to get to the farm we went on horseback, we hung a suitcase in this horse and arrived at school [...] most of my students came on horseback as well [...] (Fa.SE, 2014).

I started teaching in two periods [...] I had to go on foot, it was very difficult [...] I had road difficulties, flooding at school (Jo.N, 2014).

Structural difficulties in rural/field education are also reported by Davis and Gatti (1993), Molina et. al (2009) and Ribeiro (2010). In this context, the so-called “rural schools” were installed on farms, they were usually (in many places still are) constituted by a classroom where children of different stages of schooling were gathered under the guidance of a single teacher. The whole organization and functioning of the school was performed by the teacher who, in addition to teaching, took on the daily activities of cleaning and preparing meals, as well as administrative activities for his school unit, as pointed out by Rocha (2010) and corroborated by statements from this school. search:

It was in 1991 when I went to school!. I got there, I had to clean the school, prepare school meals, teach classes for 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th grade all mixed up; there was no water, I had to fetch it from the stream. And I got there early, by bike, it was 25 km to go and 25 km to get back, so I used to ride 50 km here on the Cuiabá road to go to this school to teach (Wi.SE , 2015).

Until 99, a teacher's job in the classroom was everything: teacher, secretary, grocer, janitor, everything. All work was carried out by the teacher, sometimes in partnership with students, there was cooperation [...] because you couldn't handle everything. At that time, our salary was very small [...] (Ce.N, 2014).

In addition to the work overload, the little professionalization of the teacher's work is evident. The precarious conditions of teaching work and the functioning of schools portray the historical neglect faced by rural education, since those who would have access to it were the children of workers, and not of the great landowners, who studied in city schools and even abroad. The municipalization of elementary school also caused “an omission in relation to the field school, as most of the city halls did not have sufficient resources to maintain them” (CASAGRANDE, 2007, p.60).

At the end of 1980 and in the 1990s, a period of intense urbanization in the state of Mato Grosso, some lay teacher training programs and projects were organized by Seduc/MT (those who did not have qualifications for teaching), including those called rural schools. Among the projects that aimed at qualifying for teaching, we can mention Inajá (1987), Homem Natureza (1990), GerAção (1997) and Tucum (1995) - specifically for indigenous teachers (ROCHA, 2010).

ORIENTATION AND SUPERVISION OF PEDAGOGICAL WORK

In this item we analyze how the teachers developed the pedagogical work, what orientations they received for this and how the institutional relations took place.

We understand pedagogical work as “the mode of organization that the school assumes in the task of thinking and producing the relations of knowledge between subjects and the concrete world, the world of socially productive work” (MACHADO, 2003, p.246), which is related to the mode of socioeconomic organization of the society in which the school is inserted. According to Frizzo (2008), it is somewhat risky and even difficult to reduce the meaning of the work carried out in schools to a practice - pedagogical or teaching - because in this way the axis of problematizing the pedagogical work moves from the quality of intellectual human activity to a human praxis. Pedagogical work “is a social practice that acts on the configuration of individual and group human existence to realize the characteristics of human beings in human subjects” (FRIZZO, 2008, p. 5). the organization of the pedagogical work does not happen randomly and naively, but is supported by “a set of philosophical, political and epistemological principles that define school norms and actions” (machado, 2009, p. 10) that guide pedagogical practices and relationships between school subjects. the organization of the pedagogical work is a dimension of pedagogical theory, which contains proposals to materialize pedagogical work and is associated with an educational theory that involves the concept of education, society and subjects, supported by a historical project of society (FREITAS, 1995) . It encompasses the global pedagogical work of the school - political pedagogical project (PPP) - and of the classroom, which implies to think about the contents, methodologies and purposes that link such actions. It means thinking about the curriculum with pedagogical knowledge and practices that will be prioritized: the organization of teaching, school time and assessment.

According to the speeches of the interviewed teachers, the political-pedagogical orientations that field schools received in the 1980s and 1990s came from Seduc/MT and the Municipal Education Secretariats (SME), observing the recommendations and indications of the Ministry of Education. Education (MEC). Initially, the orientations were carried out through visits and pedagogical advice to schools, with a frequency varying from 15 to 60 days; later, they also began to take place through courses. The precariousness of transport and roads made it difficult for schools to access consultancy services, as well as teachers to SMEs.

There wasn't much pedagogical support, because the schools were small and a little isolated from the SME and the pedagogical coordination. It was always very far away! If we needed any resources from the school management, we had to travel a few hours by bicycle or hitchhiking to try to solve these shool problems (Ze.CS, 2014).

Other interviewees also state that in the 1980s, periodic visits by SME representatives to field schools prevailed:

We even had visits from the secretary, who was willing to participate in the process with us, to work on literacy step by step. It was a very rigid issue, the school days. They would schedule the meetings in a center, pick us up in the schools and take us there, where we made works and many kinds of posters [...] There was a supervisor who went every month, but if we had some problem in the school, the visit was more frequent (Ce.NE, 2014).

There was coordination of the secretary, who went to the rural schools in a van [...] and visited to see how you were working, what was the process, "the basics", if the children presented good performance [...] (Fa. SE,2014)

According to a teacher from the center-south region, the school always received visits from the SME; when necessary, this teacher went to the SME, where there was a person responsible for her school, with whom she tried to solve administrative and pedagogical problems. She made contacts with other teachers and schools, which helped a lot, as she “even got materials to improve classes” (Or.CS, 2014). We observed that the teacher “obtained” materials, so there was no policy for supplying material to field schools.

There are minor controversies in the testimonies of teachers from the same region on the form of pedagogical orientation; they mention orientation and group planning, but also about the lack of accompaniment: “To start the school year, there was a pedagogical week, where we usually came to the city to participate [...] or else all field schools met in a pole ”(Ze.CS, 2014). This same teacher explains that, after this period "there was no pedagogical accompaniment, we received visits from the principal, the coordinator, but this was every two months or more, depending on the distance from the schools".

The character of the pedagogical orientation on the part of SMEs is also registered by a teacher from the northern region:

[...] we received instructions from the SME and from the coordinator of the field schools, who was called the director of field and rural schools. She then decided to gather teachers from different communities and each one talked about his/her experience, but there was no pedagogical or scientific training [...] The training was like this: "What are the difficulties?", "What is each one doing?" [...] It's a kind of prescription often necessary for us to get out of some situations [...] (Mi.N., 2015).

We realized that there was no defined supervision or continuing education policy, but punctual actions to meet needs and attempts to solve some problems, including those related to literacy, sometimes through the exchange of experiences. Rocha (2010) registered that there was a training proposal undertaken by the state in the mid-1970s (New Methodologies Project), whose specific concern was literacy, approval and failure rates in the early years, but that did not reach the entire territory of the state of Mato Grosso.

The challenges of the pedagogical orientation process in the 1980s are also registered by training teachers. A teacher from the center-south region, municipality of Mirassol D'Oeste, argued that in the beginning annual education planning was centralized: teachers from rural schools traveled to the city to participate, for four or five days, in this activity, leaving the family in the countryside. However, as of the third day, an emptying began to occur, as the teachers' husbands went to look for them, demobilizing the training process and making it difficult to appropriate the theoretical and practical foundations covered. What happened in the end is that many teachers went to training courses “to fulfill their obligation, but at school they followed the didactics suggested in the book they adopted. So, planning was a formality ”(Ma.CS, 2014). Thus, the SME training team in that municipality decided to change its strategy, gathering teachers and conducting training in closer centers, including thinking about training according to the “possibilities of the place” (Ma.CS, 2014), such as practices of continuing education called training, qualification or even recycling courses. They gained greater emphasis and institutionality in the 1990s.

The meaning of continuing education refers to that ocurring in studies and/or specific reflections on educational processes, conceptions, practices and references, as well as in the set of experiences lived by teachers, whether they are provided (reflections and experiences) by training or qualification courses, whether they come from daily professional practices in educational institutions or from their experiences in other social spheres (GENTIL, 2005, p.64).

A training teacher reported that she tought a teacher how to plan for each day of the week, but it was not something that involved a more elaborate and in-depth discussion: “It was a very early process and I was in my early twenties. In addition, I was learning to be a field supervisor in this situation, in this context ”(Ma.SE, 2015). We associate the speech of this trainer with the idea of learning while teaching (c, 2002), although in a somewhat intuitive way.

It is worth noting that in the 1980s, the Law of directives and bases (LDB) number 5,692/71 was in force, which increased the compulsory schooling from four to eight years of age and started to emphasize teaching of a professional and technical nature in high school, in contrast to humanistic teaching. The approval of LDB 9.394/1996, brought was a reorganization of the educational structure and an expansion of the concept of education, which started to include both formal and non-formal spaces, and also to make references to education in rural spaces (Article 28) . This law also included mandatory teacher training at a higher level.

In the 1990s, the didactic-pedagogical guidelines were expanded, as this teacher reports: “We used to come to the center of Comodoro every beginning and middle of year as there were courses for the literacy process” (Ce.N , 2014). Many of these courses were held on school holidays: “During the holidays we had longer meetings in which sometimes teachers from other places came ... we were never free in the holidays, we always had 15 days of activity in July”(Li.NE, 2015). Preferably the orientation to teachers took place during the pedagogical weeks with more institutional and targeted continuing education training, including collective exercise, but also with visits by SME technicians to field schools.

We didn't have much people to turn to. During this period, you should write down your doubts and wait for the payday when they used to come, right? But it worked [...] As time went by, visits improved. They came, gave suggestions and took notes. Then on the next visits they wanted to see what you did with the suggestions, i.e., the results. Always this proposal: “That day I was here and I gave the suggestion, what has improved in relation to that student?” [...] (Ca.SO, 2014).

Training in and through practice seemed to have been the keynote of that period, with predominance of what Tardif (2007) calls experiential and cultural knowledge, to the detriment of disciplinary knowledge or professional training, since teachers

[...] in their professional activities were supported by several forms of knowledge: curricular knowledge, derived from school programs and textbooks; disciplinary knowledge, which constitutes the content of the subjects taught at school; the knowledge of professional training, acquired during initial or continuing training; experiential knowledge, derived from the practice of the profession and, finally, cultural knowledge inherited from their life trajectory and their belonging to a particular culture, which they share to a greater or lesser degree with students (TARDIF, 2007, p. 297).

The aforementioned statements provide elements to minimally understand how the institutional relations of attendance, orientation and pedagogical monitoring between SMEs and field schools took place, as well as permiting to identify how problematic the organization of the pedagogical work was. Educational management during this period was centered on the figure of the municipal secretary of education and the teaching regional offices, established by Seduc/MT, within the scope of the Senior Management and Advisory Group. Monitoring of field schools was carried out periodically by advisors or supervisors, linked to SMEs; most of the time, teachers do what they can by themselves, relying only on the help of parents and students. How could they think about a more critical perspective with collective work and the self-organization of educators in this situation of isolation in which they found themselves most of the time?

EDUCATIONAL PRINCIPLES AND FOUNDATIONS

In this dimension of analysis, we seek to identify which principles teachers used in their educational practices. Some of these principles could be apprehended in the interviews, based on the aforementioned theorists: “I remember that it relied very much in the literacy area, authors mentioned a lot were Emília Ferreiro and Vygotsky” (Ca.SO, 2014).

The period of democratization in Brazil brought up many questions and theoretical debates, among them some related to literacy, whose indexes constituted a problem. It became possible to overcome the previously prevailing technicity, turning to the learning subject, and not only at the teaching techniques. Constructivist and sociointeractionist theories gained visibility; research as a methodological axis gained strength in this period in teacher training projects conducted in Mato Grosso, especially by the Unicamp professors' advisory (GENTIL, 2002).

A training teacher, active in the 1980s, refers to the principles of liberating education:

[...] the Paulo Freire method was not applied in full, but his ideas motivated us, our daily work was based on Paulo Freire’s ideas. The planning was based on his ideas, on the objectives of raising awareness, politicizing and making children critical and autonomous, aware of the problems they were experiencing (Ml.NE, 2014).

What can be seen from the speeches is that the meetings and training courses of the late 1980s and early 1990s tried to introduce updated perspectives for the time, those that turned to the understanding of students as subjects of learning, except for LOGOS II, which adopted a technicist perspective.

Regarding the interviewees, we can say that, in large part, the act of instructing did not detach from the act of educating and sought to establish a relationship between instructional content and the students' daily life. Teachers, with recognized authority by the community, helped to form values and worldviews, most of them linked to the need of respecting others and parents, solidarity and involvement in the distribution of tasks in the organization of the school space.

It was very good that time when the students helped with the cleaning, washed the lunch boxes. Even if you lost that time, you won in another aspect, such as being responsible at an early age, taking care, keeping things clean, ok? But not today when, they seem to find everything ready and don't care, they throw garbage on the floor [...] (Lu.SO, 2014).

In a way, in these pedagogical practices, a work-education relationship was configured as an educational principle, making work as something necessary for the maintenance of school life and as an activity from which “no one can escape”, but not necessarily as an emancipating educational principle (FRIGOTTO; CIAVATTA; RAMOS, 2011; SILVA; ANDRIONI; MACHADO, 2017). Work, in its emancipatory conception, implies questioning social and productive relations, the capitalist mode of production, with a view to building measures to overcome the relations of exploitation of man by man and forging a socialist society.

In the northeast region (Araguaia), which was characterized by intense land conflicts, pedagogical work sought, already in the 1980s, to articulate the discussion on the issue of the struggle for land with school education, problematizing the reality of families as a way of defining generating themes and words, which were approached from the Paulo Freire’s perspective of cultural circles, as evidenced by a training teacher:

[...]the generating words were the highlight of literacy [...] it is what Paulo Freire called the culture circle, which is in the book Pedagogy of the Oppressed. The culture circle sometimes lasted for days, projected [the generating words] and then emerged the debate [...] they had already been prepared, there had been a research that had raised these keywords [...] (Ju.NE, 2015).

We also register an indication of training project in a more critical perspective in the speech of this training teacher:

[...] I have seen field education not as the education that I see today in many schools - just reading and writing - but this was a much more complete education, i.e., one that worked a lot on political, public and state issues. It was so that to me the school of [...] was the most complete school that you can imagine, because there we worked all the contents with great quality, but there were also all the political and social problems of that community, of that district, and the school was responsible, it brought this discussion, the forwarding of proposals, the interventions that had to be done, everything was discussed at school [...] (Ml.NE, 2015).

At the end of the 1990s, the delineation of field education in areas of settlement of agrarian reform connected to the MST became evident, with some principles and practices along the lines of the movement, in a critical perspective, with more explicit objectives, although under construction.

[...] whoever went to work in these settlements was already for this purpose and already knew that the field education was going to be different. They said "we have to do it differently". The planning was collective, where ideas came upon, but we took the whole SME plan, we didn't drive away from it, just adapted it. For example, if I was to pass a problem to the student, I'd adapt it by talking about the field, valuing the field, bringing our reality to it. [...] (Mg.SE, 2015).

The issues pointed out in the previous interview are close to the principles assumed by field education, which proposes to work current matters (PISTRAK, 2002), seeking to understand the major issues or problems of social practice (work, economics, culture) that concern subjects of a given community. They need to be understood and transformed through the committed intervention of subjects that have a praxiological character, established by close articulation of the school with the lives of students and their families. This is an aspect which the organization of the pedagogical work cannot neglect, as the school's focus is on human and emancipatory training

We understand that the pedagogical work needs to start from problematizations, aiming at raising awareness about human values, the experience being constantly recreated from cultural contents and seeking democratic forms of social interaction. Therefore, “the concept of education must include a vision of the future that considers the human condition as an essential object of all pedagogical work” (FRIZZO, 2008, p. 6-7).

ORGANIZATION OF THE PEDAGOGICAL WORK

The data from the interviews show that there was no pedagogical proposal or an explicit pedagogical project for field schools; the guidelines came from the pedagogical secretariats/advisories/supervisions and served to help organize the course plans at the beginning of each year (in the pedagogical week) which, in turn, have been translated into the activities that the teachers developed with the students during the academic year. A teacher from the central-south region expresses her unseasyness regarding the fact that rural schools have to follow the proposal and the form of organization of the urban school:

One of the facts that marked me a lot was in relation to the school calendar, [...] the calendar that we received at the field school was that of the urban area, so it was not focused on our reality of the countryside. There was a moment when I called the school principal to change the school's vacation period, due to the cotton harvest that was taking place and the students were away from classes to harvest cotton, this was in the 1980s [...] The principal got concerned with SME, with the secretary [...] and I decided to face the problem on my own and changed the school holidays (Ze.CS, 2014).

It is interesting to note the discomfort of this teacher when realizing that the school organization, mirrored in urban standards, did not favor the relationship between the school curriculum with the life and work of the community or the work-education articulation. Sometimes such aspects appeared in the proposals of some training courses that were concerned with the understanding of the school's surroundings and had reality as a dimension that needed to be explored.

In a research on rural school, Davis and Gatti (1993) referred to the little “institutionality” of the school, even with the ritualization of activities, certainly starting from the traditional/capitalist school model. However, from the evidence collected in the interviews, we can say that the format of the relations was standardized, very institutional, especially regarding knowledge, although fragile in terms of content domain. Generally, there was an external requirement and compliance with planning and content pre-defined by SMEs that was minimally charged in terms of learning assessment; and also the teacher's authority as a recognition and mark of this institutionality.

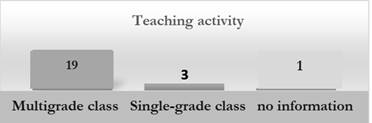

The organization of teaching was configured by the existence of the only teacher and the multiseries classes - marks of the teaching performance of most of the participants of this research, as shown in Chart 1, as follows.

A teacher from the center-south region (Or. CS) said that she worked with around 30 students with different levels of learning. To be able to serve everyone, she divided the classroom environment with two blackboards, thus forming two classes, one facing each blackboard. This kind of work was also adopted by a professor from the southeast region in the early 1990s: “I got there and took the books from a shelf. The 1st grade contents were placed on the 1st grade blackboard, and the 2nd grade contents on the 2nd grade blackboard, following the books. Then I gave the exercises also in that way, that’s how I worked”(Wi.SE, 2015).

The inexperience and lack of specific training impelled some teachers to act based on their experiences as students (experiential knowledge), without greater discernment about their pedagogical practice, as was the case of a teacher from the Northeast region (Li.NE, 2015): “When I started working there was a study up to the 4th grade, so what did I know? After all, I knew how to teach ‘a, b, c,’ because that was what I had learned, right? ”. Educators from other regions also spoke of the lack of training and even age, to assume the teaching role:

We had no guidance from anyone to prepare classes. It was necessary to prepare classes based on what we learned as students. If I learned the four operations, or reading and interpreting problems, I have to make the student reach the fourth year doing the same thing (Ja.N, 2015).

[...] in 1980/81 I almost received a summons to assume the classroom of a small school on a village called the Comunidade de São Sebastião, 13 km from Colíder [...] I, at that time, was only 17 and had attended up to the 8th grade. So I was considered a trained person [...] (Mi.N, 2015).

Other statements portray the reality of the teacher and the lay teacher, the way of organizing the pedagogical work and the difficulty of working with multi-grade classes:

[...] as I was a layperson in the area, what did I do? I divided the classroom into four groups. I put one group in each corner of the room, we couldn't use the blackboard, so I used big placards of brown paper. We called it a traveling notebook, we went on changing pages, turning it over and in the next class we did other activities. At the end of the week, we had a bunch of paper that was used as if it were a slate (Va.NE, 2015).

There was very young, adult and married students, so there was a real mix of students, which also made it difficult [...] The older people sometimes served as monitors for the younger ones. But there was a classroom that we found difficult, because the younger students got in the way, according to the older ones (Ci.N, 2014).

The statements deal with situations from the 1980s and 1990s, but it is worth noting that schools or multiserial classes are supported by the Article 23 of LDB 9.394/96, which refers to different forms of teaching organization. However, it was with the approval of Resolution CNE/CEB Number. 2/2008 that direct mention was made of multi-grade schools. They are formed mainly in rural locations with few students per grade. Thus, “in the same class, students with different ages and educational levels are found” (OLIVEIRA; OLIVEIRA, 2015, p. 225). These authors, based on a survey carried out in more recent years, also noted the difficulty of teachers in dealing with this form of school organization - the multiseries - with regard to planning and the teaching-learning process, since “it requires elaboration of varied strategies, to attend not only the different needs of contents, but also to the great variation of interests and modes of interaction resulting from the differences of students’ age groups”(OLIVEIRA; OLIVEIRA, 2015, p. 225).

In the analysis of the research data, the contradiction of the multi-grade classes is evident: for the management and communities, it was the guarantee of the school's existence; however, for teachers with little training, it was an increase in difficulties. Nevertheless, forms of interaction between students of different grades were promoted, which practically obliged the teacher to adopt a different pedagogical practice:

[...] the mixed classroom, the multi-grade classroom, I don't think it's reprehensible, it's possible to learn, and this came to happen in the classroom where I worked, those who finished earlier helped the others [...] I’m not sure if the older kids were at a disadvantage, I think so regarding the contents of the fourth grade, you know? But if we turn to Paulo Freire, who said that "who teaches also learns", then maybe they were alsolearning, right? (Mi.N, 2015).

Today [...], the multi-grade classes are very frowned upon, they say that the student doesn't learn, but in fact he does learn [...] (Ca.SO, 2014).

The studies by Hage (2006) and Arroyo (2010) contribute to a deeper analysis of this theme, highlighting the potential of multi-grade classrooms, as well as the need for public policies for the qualitative development of the pedagogical work in these spaces. It was recurrent among the interviewees that they gave individualized attention to the students and adopted the strategy of "assigning more tasks" to each student who finished before the others. However, we noticed that there were moments of more collective and collaborative work in which the "more advanced" students helped the beginners: "the student who knew a little more helped others, he had room to contribute. It was interactive, I think they didn't even have the notion that each one was in a different grade" (Yo.SO, 2014). The speech of a teacher from the north region goes in this same direction: "So it was that mutual help: the student who could read helped the one who couldn't, just like this, right? (Ja.N, 2016). Among the activities that enabled the "doing together", one interviewee mentions:

[...] multiplication tables, it was something done together, reading also, but the specific content [...], some could be done, but others couldn’t. Text production, text interpretation... At that time we were learning to work with the generating theme, then there was tha division of contents and the discussion was done with all students (Ca. SO, 2014).

However, one teacher trainer warned that some teachers insisted on using the traditional teaching method. There was resistance to "following" SME guidelines by some teachers in the training courses and pedagogical orientations:

I remember an area coordinator of the time that used to say: "Look at the poor teacher, she just guides the students", i.e., she applies the method of globalization, of the wording. But before that she had already used the old method, teaching by syllabification. So, all of them used the primer “Caminho Suave” (Smooth Path) and the syllabification process a lot, that was what they really used (Jb.SO, 2014).

There was a great rejection, but as there was inspection, they used the old method of teaching through syllabus (syllabification) and warned the students like this: “Look if an inspector comes here, you will say that we went to the chicken farm and there you mentally wrote the words. The generating theme was chicken farm, so you wrote down what you saw, chicken, chicks and so on.” But the actual teaching [...] was by the old method, alphabetical and syllabification system (Jb.SO, 2014)

We infer from the interviews that the main goal of the teachers was to instruct students in learning and mastering letters and accounts. This required the teaching staff to transmit content through oral explanation and demonstration, with examples and didactic materials, and also to use the methodology of studying the environment or experiential laboratory6 . However, as we highlighted earlier in this text, along with the instructional training, there was, in one way or another, education and values formation. Despite the possible "resistance" of the teachers, it is worth noting that the precariousness of didactic materials was a common characteristic of field education in the regions researched. Teaching materials and resources are understood as the set of "pedagogical products used in education and specifically as instructional material that is produced for teaching purposes" (BANDEIRA, 2011, p.14).

According to the teachers, the schools received primers for literacy, but rarely textbooks for the other grades. So the teachers resorted to colleagues and to the "leftovers" of materials from urban schools: "It was more difficult for things to arrive in rural areas, so we were left just with leftovers (Li.NE, 2015). These difficulties were also reported by a teacher from another region: "[...] we had access to almost nothing at that time, but learning happened, right? We had nothing, no placards, no cardboard, we used the registration forms to make placards" (Lu.SO, 2014). However, some interviewees said that the school "received notebooks and pencils from the SME" (Or.CS, 2014). Teachers used magazine clippings, visual resources such as placards (used light cardboards), reading sheets, mobile alphabet.

[...] we’ve got a lot of material [...], we’ve got reading bags, and those folders that came with suggestions for generating themes for us to develop in the field (Va.NE, 2015).

Chalk. Mimeograph. Stencil. It was something widely used at that time. Then it got better, right? Light cardboard, too. Kraft paper and other materials. Initially, textbooks were scarce. But over time, no (Ca.SO, 2014).

Regarding textbooks and primers, it should be noted that in the early 1980s, the orientations of the II Education and Culture Sector Plan for the years 1975 to 1979 were still in force, which provided, for elementary and middle school, to implement the "project of development of new methodologies applicable to the teaching-learning process" (CARDOSO, 2012). As a way to address the high dropout rates and improve the quality of education, this goal was added to the reformulation of curricula, training of teaching staff, expansion and improvement of the physical network of schools and improvement of the planning process and school administration. Rural education appears associated with the concern about the low rate of schooling in Brazil due to the insufficient number of schools in rural areas, whose solution was proposed by the expansion of the educational offer in this context. Seduc-MT developed a subproject in this area, which culminated in the elaboration of didactic material observing the specificities and regional culture, such as the Primer Ada e Edu7. In this way, we agree with Oliveira et al. (1984, apud CARDOSO, 2012, p.111) when they say that "the textbook is part of the arsenal of instruments that make up the school institution, which in turn makes up the educational policy, which is inserted in the historical and social context.

In the northeast region, more specifically in the micro-region of Araguaia, there were experiences of formulation of their own primer, as one of the interviewed teachers reports: "[...] The primer was part of the process, in the 1980s, it was the Capybara primer" (Ml.NE, 2014). In this region, in 1984, the primer Estou lendo8 (I am reading) often recognized by the generating themes of its lessons (pumpkin, capybara, puma) instead of its "official" name.

However, textbooks did not reach the schools in the various regions of the state of Mato Grosso in the same way:

We had materials and everything, but it wasn't like education in the urban area [...] our materials, generally, were collections requested for the school and we didn't have more consistent material with our reality. For the rural areas, the themes were not worked on directly with the state. So it was kind of a globalized education, right? (Ce.N, 2014).

According to Sacristán (2000), the teaching media, especially books, are the agents that present the pre-designed curriculum, the translators of the curriculum to teachers. Therefore, curriculum policy should ask itself what kinds of media can be more useful to instrumentalize the curriculum, to be effective in helping teachers and in developing his/her professionalization, besides questioning the existence of an indirect (and external) control over the curriculum. Added to this is the contribution of professional training to understand the curriculum issues and improve pedagogical practice.

It is a common speech among the interviewees that the pedagogical work began to signalize improvement with the training courses. The data indicates that the state of Mato Grosso had countless teacher training experiences that also involved field training courses, such as: Logos II, Homem Natureza, Parceladas, Geração, Inajá, Tucun etc.

It was very simple. I was taken away from my job [...] I was a farmworker and suddenly I became a teacher. So I had the level of the students that I worked with, the fourth grade, and I kept acquiring knowledge through courses and training. Before the Projeto Homem Natureza, I also took LOGOS, from 5th to 8th grade. Every weekend I came from there to here for the disciplines(Ca.SO, 2014).

Thus, in the 1990s, the way of organizing the pedagogical work, especially in relation to the methodologies used by teachers in many field schools, came to be closely related to the principles and practices that permeated the training courses that these teachers took part in, such as the "Projeto Homem Natureza", which allowed the pedagogical practice in the rural school to be "focused exactly on the student's experience in that school or community space [...] the environment itself, where the school was inserted was what we had as an experiential laboratory" (Yo.SO, 2014). The statement of another teacher highlights the work with projects: "[...] until 1995 we didn’t have projects, we worked more on content and concepts. We started to develop projects after 1995, with the GerAção project" (Ce.N, 2015). Thus, the teacher training courses, developed especially after the approval of the LDB and the FUNDEF, caused changes in the organization of the pedagogical work of schools, both in the country and in the city, because they included more problematizing teaching methodologies, paving the way for what is expected from a more critical perspective of reality, with possibilities of overcoming the fragmentation of knowledge and pedagogical actions.

The teachers' pedagogical practice, in many cases, included leaving the classroom and doing research in the surroundings of the school. Thus, as stated by a teacher (Ce.N, 2014), it was possible to modify the class development issue, so that it would be "more tangible and not that thing centered only on theory that you don't come to practice". The relationship between theory and practice, school and life, was sought. She also highlights the influence of the teacher trainer of the Projeto Geração in the constitution of this way of working, given the motivation to develop activities, especially in science, using research and other spaces in the field, besides the classroom. A similar statement is registered in the speech of teacher "Yo", from the southwest region.

Another form of organization of the pedagogical work was characterized by the generating themes and the problematization of reality, based on the social issues of the community, which fulfilled the classroom.

[...] there was a problem (of land conflicts). So we had to work with these children and their parents, grandparents, uncles, and neighbors, a complete, whole training far beyond than just writing, but to think and understand their surroundings and the problems that the family was involved in. So we searched for texts that contributed to understand all that (Ml.NE, 2015).

We worked with the generating theme, we elaborated it and developed its content on a weekly basis (Va.NE, 2015).

The study by Davis and Gatti (1993) about the classroom dynamics in a rural school indicated that the process of knowledge appropriation was characterized by transmission, memorization and repetition; the process of knowledge construction was not made explicit, since the teacher "did not always dominate the contents she was going to transmit" (DAVIS; GATTI, 1993, p. 80). It is worth saying that in the 1980s and early 1990s traditional teaching predominated in Brazil, with the basic requirement that the teacher transmitted the contents well and that the students demonstrated, through tests, that they had learned what was transmitted by the teacher. Certainly, this type of teaching did not manifest itself in the same way in all schools, assuming different characteristics due to each place, composition of the classes, students and profile of the teachers. However, the testimonies of the teachers from the state of Mato Grosso, highlighted in this text, oppose the reality presented by Davis and Gatti and attest how dynamic this process was, and that was not only the reproduction and transmission of knowledge, but also a process of creation/production and even a confrontation with the academicist logic, different from the reality and needs of the students.

n the interviews conducted in this research, we came across few situations similar to the one described by Davis and Gatti (1993), in which the process was configured more as transmission/repetition than knowledge construction. This situation was conditioned by the limiting factors to which the teachers were exposed and that, to a large extent, were due to insipient training and pedagogical support. The following speech serves to illustrate this situation:

We didn't have instruction and didn't have a pedagogical team supporting us. The planning that we did required a more trained teacher [...] we received the books to work [...] at that time the teacher followed a lot what the parents asked. There was one main focus, which was to read, write and interpret, there wasn't much else to do [...] especially until the end of 1980, I received this request from the parents. In the meetings they said that the child had to know how to read and calculate, read well and write well, the rest you leave alone. Calculate, interpret and read well was the parents' request and we worked more focusing on this. If it were a fourth grade child, he/she had to know how to write a note, a letter, an official letter (Ja.SO, 2014). (our emphasis)

As we can infer from this statement, another factor to be considered is that the context in which the school was located, the form of dialogue that was established between parents and school, as well as the "demands" they made, ended up influencing and even shaping the pedagogical practice and the teaching work. This issue refers to Sacristán's (2000, p.202) thought about the complexity of the structure of pedagogical practice: "practice is something fluid, fleeting, difficult to understand in simple coordinates and, moreover, complex, as multiple determinants, values, and pedagogical uses are expressed in it". Among these determinants we highlight the institutional, organizational, methodological traditions, the physical and material conditions, and the actual possibilities of the teachers. Therrien (1991) argues that rural lay teachers, in the exercise of their functions, in one way or another, ended up taking into account the interests of workers in terms of their struggles, culture and forms of production, which came to constitute their social knowledge, making them subjects of heterogeneous pedagogical practices (GARCIA; MACHADO, 2017).

In the context under analysis, we found that the relationship between school and community was a factor that contributed greatly to the structuring and functioning of the school. There was a great proximity between the community (parents, mainly) and school/teacher, even because the teacher was the only worker in the school and, more than ever, needed to rely on the community to make the institution work. Teachers often provided firewood for the stove to prepare meals, pruned the bushes and cleaned the school yard: "[...] at that time we had nothing, but little wood stove, so the parents helped, for example, with firewood; if we had to do a joint effort to clean the yard, they helped. We also had a vegetable garden that we grew [...]" (Lu.SO, 2014). The participation of parents in the political and pedagogical management of the school was also noteworthy, as in the case of schools located in rural settlements.

[...] even the names of the schools were chosen by the parents. So everything was gathered and discussed in the school space, the parents participated and decided about the school [...] When there was lack of water [...] the parents brought water to make the lunch, helped and participated in everything. The school was the center, the place where masses were celebrated and the association meetings were held. So, the school was the center of the settlement, of the movement (Mg.SE, 2015).

Parents were always very present in the school, we always called them and they came [...] So there was very strong responsibility, where there was the MST [...] (Ma.SE, 2015)

In the various testimonies collected, it is evident the enormous respect that parents/community had for the school and the teacher at that time, which led to great feedback when they were called to talk about the development of their children and about the school.

CONCLUSIONS

in this text, we analyzed the processes related to the organization of the pedagogical work in field schools in the state of mato grosso, in the 1980s and 1990s, considering four articulated dimensions: working conditions, orientation and supervision of pedagogical work, educational principles and foundations, and organization of the pedagogical work.

The narratives presented in this research indicated that there were few effective conditions to monitor the pedagogical work developed in field schools. The predominant objective of the SMEs was to guarantee the functioning of these schools, visiting them whenever possible and offering basic orientation for their functioning, delivering school meals, some didactic material, and giving suggestions in case of any difficulty presented by the teacher. Thus, in their daily work, the teachers individually sought solutions to the problems that arose, by trial and error, most of the time with sporadic help. However, such difficulties did not prevent the SMEs from demanding a teaching plan, as well as results, which often included the application of tests and examinations to ensure what the students had learned.

Teachers worked under adverse conditions, starting with insufficient professional training - most of them had the equivalent of elementary school in the 1980s and high school in the 1990s, so learning how to teach took place in the very act of teaching, mediated by continuing education courses and initial training. Another difficulty was the problems of transportation and commuting from field to city, as teachers were often isolated due to the poor road conditions and long distances. Finally, there was the fact that resources and didactic materials arrived in an inconstant and regimented way in most schools, which led teachers to seek materials from colleagues and to reuse material from other schools.

regarding the organization of the pedagogical work - space-time, classroom organization, curricular organization, methodologies, etc. - based on the teachers' testimonies, we found the predominance of multi-grade classes; the use of methodologies focused on transmission/memorization of content mixing individualized attention to the student with group/collective activities and also the use of participatory and investigative methodologies, based on the study of the environment and experiential laboratory; and the curricular organization by fragmented subjects, work projects and generating themes, noting the influence of teacher training courses in the adoption of a curricular perspective and pedagogical practices more open to criticisms.

We must agree with Sacristán (2000) when he states that the pedagogical practice is a complex work, since the school and the teacher have to respond, with the curriculum, to diverse social and cultural needs, implying the connection of very diverse knowledge to the teacher at the time of acting; the conditions of professional training were not the most adequate, as well as those in which he performed his work. For this reason, not all teachers were able to plan their curricular practice based on general guidelines, principles and knowledge. Teachers began to use "pre-elaborations" to "pre-plan" their practice (SACRISTÁN, 2000, p.149), i.e., pre-elaborations of the curriculum for teaching, which were present in the accumulated professional tradition and in what external agents offered to the elaborated curriculum.

In the midst of the challenges and contradictions experienced in field education in the 1980s and 1990s, it is worth mentioning the social function fulfilled by rural schools in providing access to systematized knowledge and cultural socialization for the children of rural workers. In that period it became evident that this teaching modality was not conceived in its specificities by public agents and public policies, being inserted, in a secondary way, in general education policies. It is worth remembering that this is a period when field education was called rural education, whose specificity was only mentioned in the LDB of 1996, in its article 28, even though the social movements of the countryside had already waved to the constitution of a field education project, which would really happen in the 1st National Meeting of Educators of Agrarian Reform (ENERA) in 1997, Luziânia, state of Goiás. The configuration of field education as a conception and recent public policy is present in the speeches of the interviewed teachers, which are highlighed as follows:

It has been a little while since we had this vision of showing the population that the countryside is a specific place that should be valued and known as such, and that it is also the place for people to remain in their environment. So there would be no rural exodus, which happens a lot due to devaluation [...] (Ce.N, 2014).

[...] field education has been emerging since the 2000s, with conferences, conquests of the current struggle present there, with several trainings for that. There is the continued training of field education, the initial training [...] Field education is not (only) training for the countryside, it is training to humanize and politicize its subjects (Ma.SE, 2015).

As evidenced in the interviews, the field education is the result of workers' struggles, articulated around the social movements of the field. The field education is inserted in a logic of emancipatory education, which presupposes the existence and the potentialization of theoretical and practical instruments that enable the subjects to a critical appropriation of knowledge, of science, in the perspective of better understanding the reality and training that projects the human and social development, both in personal and collective dimensions. Therefore, it is an education linked to a conception of omnilateral training, in the perspective of improving all the creative potentialities of the person and, because of it cannot be done without articulating education, work, culture, and technology. In this conception, "the field assumes the dimension of historical space in the dispute for land and education, overcoming the rural that does not consider peasants as subjects producers of knowledge, culture, language, art, and history" (RIBEIRO, 2013. p. 3).

We do not advocate a specific school for the countryside, but the field education and of and its subjects, in recognition of specificities that were historically disregarded in the supposed universalization of rights. We speak of a diverse field - of family farmers and peasants, of indigenous, riverine, and quilombola communities, among others - which requires enabling the full operation of schools on the part of the State, as established in the national policy for field education and its complementary laws. On the part of education professionals, students, and parents, a straight action is required, as an exercise of collective and democratic participation, in order to materialize, in the scope of each community, an educational project corresponding to the perspective of building a new sociability in the countryside and in the city.

We hope that this study brings more visibility to field education, making possible the comprehension of experienced processes and providing indicators for other necessary actions, such as the proposition of more consistent policies, which recognize the knowledge already produced and the diversity of the field, besides registering part of the history of education in the state of Mato Grosso, whose social and economic life is primarily based on the activities developed in the countryside.

REFERENCES

ARROYO, Miguel. G. Prefácio: Escola de direito. In: ANTUNES-ROCHA, Maria Isabel; HAGE, Salomão M. (Org.). Escola de direito: reinventando a escola multisseriada. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2010. p. 9-14. [ Links ]

BANDEIRA, Denise. Materiais Didáticos. Curitiba, PR: IESDE, 2009. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.academia.edu/10850993/Materiais_did%C3%A1ticos . Acesso em:29 maio 2019. [ Links ]

CALAZANS, Maria Julieta C. Para compreender a educação do Estado no meio rural - traços de uma trajetória. In: THERRIEN, Jacques; DAMASCENO, Maria N. (Org.). Educação e escola no campo. Campinas: Papirus, 1993. p.15-42. [ Links ]

CALDART, Roseli S. Iseminário com as escolas de inserção dos estudantes. In: CALDART, Roseli S. (Org.). Caminhos para a transformação da escola. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2010. p.13-22. [ Links ]

CALDART, Roseli S. Sobre a Especificidade da Educação do Campo e os desafios do Momento Atual. 2015. Disponível em: file:///C:/Users/Windows/Downloads/EdoC-DesafiosMomentoAtual-Roseli-Jul15%20(6).pdf. Acesso em:04 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, Cancionila J. Cartilha Ada e Edu: produção, difusão e circulação. Cuiabá: EdUFMT, 2012. [ Links ]

CASAGRANDE, Nair. A pedagogia socialista e a formação do educador do campo no século XXI: as contribuições da Pedagogia da Terra. 2007. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Faculdade de Educação. Porto Alegre, 2007. [ Links ]

DAVIS, Cláudia; GATTI, Bernadete. A dinâmica da sala de aula na escola rural. In: THERRIEN, Jacques; DAMASCENO, Maria N. (Org.). Educação e escola no campo. Campinas: Papirus , 1993. p.75-135. (Coleção magistério. Formação e trabalho Pedagógico) [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia. 25ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2002. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Luís C. Crítica da organização do trabalho pedagógico e da didática. Campinas: Papirus , 1995. [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, Gaudêncio; CIAVATTA, Maria; RAMOS, Marise N. O trabalho como princípio educativo. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.pb.iffarroupilha.edu.br/site/midias/arquivos/201179171745208frigotto_ciavatta_ramos_o_trabalho_como_principio_educativo.pdf . Acesso em: 28 fev. 2019. [ Links ]

FRIZZO, Giovanni. O trabalho pedagógico como referência para a pesquisa em educação física. Revista Pensar a Prática, v. 11, n. 2, Goiânia: Editora da UFG, 2008. p.1-10. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.revistas.ufg.br/fef/article/view/3535 . Acesso em: 29 maio 2019. [ Links ]

GARCIA, Luana S.N.; MACHADO, Ilma F. Retrato do ensino rural no município de Cáceres, nas décadas de 1980 e 1990. Revista Pedagogia, UFMT, nº 7 Jul/Dez 2017. p.134-141. [ Links ]

GENTIL, Heloisa S. Formação docente - no balanço da rede entre políticas públicas e movimentos sociais. Dissertação de Mestrado. PPGE/UFRGS. Porto Alegre, 2002. [ Links ]

GENTIL, Heloisa S. Identidades de professores e rede de significações - configurações que constituem o “nós, professores”. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Programa de Pós-graduação da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, 2015. 302p. [ Links ]

GAMBOA, Silvio S. Pesquisa em educação: métodos e epistemologias. 2. ed. Chapecó: Argos, 2012. [ Links ]

HAGE, Salomão M. Movimentos sociais do campo e afirmação do direito à educação: pautando o debate sobre as escolas multisseriadas na Amazônia paraense. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos. Brasília, v. 87, n. 217, set./dez. 2006. p. 302-312. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Ilma F. A organização do trabalho pedagógico em uma escola do MST e a perspectiva de formação omnilateral. Tese (Doutorado). Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Faculdade de Educação. Campinas, 2003. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Ilma F. Um projeto político-pedagógico para a escola do campo. Cadernos de Pesquisa Pensamento Educacional, n. 8, vol. 4, jul.-dez., 2009. p.1-10. [ Links ]

MARX, Karl. A Ideologia Alemã. São Paulo: Expressão Popular , 2009. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Monica C.; OLIVEIRA, Liliane L.N.A.; MONTENEGRO, João L.A. Das desigualdades aos direitos: a exigência de políticas afirmativas para a promoção da equidade educacional no campo. Brasília: CDES/Sedes, 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.gepec.ufscar.br/publicacoes/ . Acesso em:11 jul. 2019. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Monica C.; FERNANDES, Bernardo M. O campo da educação do campo. In: MOLINA, Monica C.; AZEVEDO DE JESUS, Sônia M. (Orgs.). Contribuições para a construção de um projeto de educação do campo. Brasília, DF: Articulação nacional por uma educação do campo, 2004. p.32-53. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Monica C.; ANTUNES-ROCHA, Maria Isabel. Educação do campo: história, práticas e desafios no âmbito das políticas de formação de educadores - reflexões sobre o Pronera e o Procampo. Revista Reflexão e Ação, Santa Cruz do Sul, v.22, n.2, jul./dez.2014. p.220-253. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://online.unisc.br/seer/index.php/reflex/index . Acesso em: 04 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Maria Rita D.; OLIVEIRA, Nazareno S.S. Classes multisseriadas: práticas, memórias e formação docente. Revista Margens Interdisciplinar. v. 9, n. 12, UFPA: Editora Campus de Abaetetuba, p.224-233, 2015. [ Links ]

PERIPOLLI, Odimar J. Um olhar sobre (o campo) a educação no/do campo: A questão das especificidades do ensino. Revista da Faculdade de Educação, Ano VIII nº 13, Jan./Jun. Cáceres: Ed. Unemat, 2010. p.51-62. [ Links ]

PISTRAK, Moisey. Fundamentos da escola do trabalho. São Paulo: Expressão Popular , 2002. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Marlene. Movimento camponês: trabalho e educação. São Paulo: Expressão Popular , 2010. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Marlene. Política educacional para populações camponesas: da aparência à essência. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 18n. 54jul.-set. 2013. P.669-796. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/v18n54/09.pdf. Acesso em: 03 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Simone A. Formação de professores em Mato Grosso: trajetória de três décadas (1977-2007). Cuiabá: EdUFMT , 2010. [ Links ]

SACRISTÁN, José G. O currículo: uma reflexão sobre a prática. Porto Alegre: ARTMED, 2000. [ Links ]

SILVA, Rose M.; ANDRIONI, Ivonei; MACHADO, Ilma F. Ensino médio integrado: acirrar contradições e abrir brechas. Revista Labor. Edição Especial. vol. 02, nº 18. Fortaleza/CE, nov. 2017, p.78-92. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Maria Antônia de. (Org.). Escola pública, educação do campo e projeto político-pedagógico. Curitiba: UTP, 2018. [ Links ]

TARDIF, Maurice; LESSARD, Claude. O Trabalho Docente: elementos para uma teoria da docência como profissão de interações humanas. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2007. [ Links ]

THERRIEN, Jacques. A professora leiga e o saber social. In: Brasil, ME. Professor leigo: institucionalizar ou erradicar. São Paulo: Cortez, 1991. [ Links ]

VENDRAMINI, Célia R. Educação do campo: uma educação virada para o futuro? In: CANÁRIO, Rui; RUMMERT, Sonia M. Mundos do trabalho e da aprendizagem(Org.). Lisboa: EDUCA, 2009. p.97-106. [ Links ]

4Available at: http://www.seplan.mt.gov.br/documents/363424/11245058/Cen%C3%A1rio+Socioecon%C3%B4mico+v+1.0.01+conclu%C3%ADdo+20190329.pdf/05c8f4d6-4bbb-ff02-c122-e6518a6ae1a8. Access in: Nov, 30 2020.

5We used semi-structured interviews as a procedure to obtain information, i.e., oral sources of specific data, according to defined objectives. At no time we intended to study the local memory.

6Study of the environment or experiential laboratory - methodologies that propose to take the environment in which the natural and social phenomena are contained as a source of study and research, using observation and experimentation for the production and/or appropriation of knowledge.

7On this subject, see Cancionila Janzkovski Cardoso, Cartilha Ada e Edu: produção, difusão e circulação. Cuiabá: EdUFMT, 2012.

8On this primer, see the Master's Dissertation: Cartilha do Araguaia “... Estou lendo!!!”: Seu circuito de comunicação (1978-1989), by Alessandra P. Carneiro Rodrigues. Graduate Program in Education, Federal University of Mato Grosso, University Campus of Rondonópolis, 2012.

Received: October 07, 2019; Accepted: December 11, 2020

texto en

texto en