Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 15-Abr-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698233148

ARTIGO

CONTRIBUTIONS OF COLOMBIAN SOCIAL WORK TO POPULAR EDUCATION WITH THE OLDER ADULTS IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON

1Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá, Colômbia. <jmerchanp@unal.edu.co>

2Universidade do Estado do Pará. Belém, PA, Brasil. <joaocolares@uepa.br>

This article is the result of a Participatory Action Research carried out during a professional internship in Social Work at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, in the pedagogical activities of the Núcleo de Educação Popular Paulo Freire of the Universidade do Estado do Pará at a long-term institution for older adults (ILPI - Instituição de longa permanência para idosos) in the city of Belém-Brazil. It aims to critically reflect and socialize the theoretical and methodological contributions made in the Colombian Social Service to the Popular Education with Older Adults in the city of Belém-Brazil. To this end, participatory methodologies and techniques (social cartography and the problem tree) are exposed as a transdisciplinary dialogue between Colombian Social Work and Popular Education, which allows the creation of scenarios of popular awareness with older adults of Belém. The results update the debate on Popular Education and Participatory Action Research, evidencing its validity together with a population segment little investigated in educational studies, the older adults protected by the State.

Keywords: Social Work; Popular Education; Participatory Action Research; Problem Tree; Social Cartography

Este artículo es resultado de una Investigación-Acción Participativa realizada durante una pasantía profesional de Trabajo Social de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia en las actividades pedagógicas del Núcleo de Educação Popular Paulo Freire de la Universidade do Estado do Pará, en una Instituição de longa permanência para idosos (ILPI) en la ciudad de Belém-Brasil. Tiene como objetivo reflexionar críticamente y dar a conocer los aportes teórico-metodológicos que se realizaron desde el Trabajo Social Colombiano a la Educación Popular con Idosos(as) en la ciudad de Belém-Brasil. Para ello, se exponen las metodologías y técnicas participativas (la cartografía social y el árbol de problemas) como un diálogo transdisciplinar entre el Trabajo Social Colombiano y la Educación Popular que permite que se fomenten escenarios de concientización popular con personas de la tercera edad de Belém. Los resultados actualizan el debate sobre la Educación Popular y la Investigación-Acción Participativa, evidenciando su vigencia junto a un segmento poblacional poco investigado en los estudios educacionales, las y los idosos tutelados por el Estado.

Palabras clave: Trabajo Social; Educación Popular; Investigación-Acción Participación; Árbol de Problemas; Cartografía Social

Este artigo é resultado de uma Investigação-Ação Participativa realizada durante um estágio profissional de Serviço Social da Universidad Nacional de Colombia nas atividades pedagógicas do Núcleo de Educação Popular Paulo Freire da Universidade do Estado do Pará em uma Instituição de longa permanência para idosos (ILPI) na cidade de Belém-Brasil. Tem como objetivo refletir criticamente e socializar os aportes teórico-metodológicos que se realizaram a partir do Serviço Social Colombiano à Educação Popular com Idosos(as) na cidade de Belém-Brasil. Para tanto, expõem-se as metodologias e técnicas participativas (a cartografia social e a árvore de problemas) como um diálogo transdisciplinar entre o Serviço Social Colombiano e a Educação Popular, que permite que se formem cenários de conscientização popular com pessoas da terceira idade de Belém. Os resultados atualizam o debate sobre a Educação Popular e a Investigação-Ação Participativa, evidenciando sua vigência junto a um segmento populacional pouco investigado nos estudos educacionais, os idosos tutelados pelo Estado.

Palavras-chave: Serviço Social; Educação Popular; Investigação-Ação Participativa; Árvore de Problemas; Cartografia Social

INTRODUCTION3

I pray to God

That pain may not be indifferent to me

That one day death not find me

Lonely without having done what I wanted4

It is unfair that eight people have the same wealth as the poorest half of humanity5. It is unfair that the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer and more poorer. It is unfair that poor children are twice more likely to die before the age of 5 and that they have twice the rate of malnutrition among children under 5 years old. It is unfair that girls are six times more likely to stay out of school and that they are 10% less well paid in adulthood than men6. Each deprivation, resulting from gender, class, race or ethnicity exacerbates the effect of the others (UNICEF, 2016) but...When do two or more coincide?

There are real conditions of oppression and inequality that are daily experienced, which are full of pain, anguish, despair, sadness and hopelessness. These situations and conditions are an important factor in the development of each person. However, as Paulo Freire (2006) states, we are conditioned beings - by genetic, social, historical, class and gender issues - these conditionings mark us and we use them as a reference, but we are not defined by them. These conditions do not define people, a destiny is not already determined; there is a possibility of transformation, the possibility of a more humane and fairer world, and that is why there are fields of knowledge such as Social Work and Popular Education.

This possibility of social transformation is exposed by Paulo Freire all along his life, and in his works he proposes a serious and committed exercise of popular conscientization based on education. This ethical-political proposal for social transformation is founded on the awareness of the oppressed, the "target" subjects of Popular Education and Social Work.

Social Work must respond to the legitimate demands and recognized rights of individuals, families, groups and communities, especially the vulnerable sectors; at the same time, it must promote processes of transformation and construction of the social structure (CONETS, 2015).

Social Work promotes the defense of Human Rights and dignity, so this work was based on Brazil’s Statute for Older Adults (BRAZIL, 20037, which promotes and encourages fundamental rights. The work of the Paulo Freire Center for Popular Education (NEP - Núcleo de Educação Popular Paulo Freire), from the Universidade do Estado do Pará (UEPA), is based on the right to education (Art. 20), in which "Older adults have the right to education, culture, sports, leisure, entertainment, shows, products and services that respect their peculiar condition of age" (BRASIL, 2003, p.18).

This article and the process it describes respond to the personal and professional commitment of the authors and NEP to work to promote a dignified life for the most vulnerable social groups. It is based on the idea that:

The political dimension of the ethical-political project of social service is positioned in favor of equity and social justice, in the perspective of universal access to goods and services related to social policies and programs; the expansion and consolidation of citizenship are explicitly posed as a guarantee of civil, political and social rights of the working classes (NETTO, 2006. p. 16).

Thus, this article aims to show that participatory methodologies and techniques (social cartography and the problem tree) achieve a transdisciplinary dialogue between Colombian Social Work and Popular Education that allows the promotion of popular awareness scenarios in vulnerable populations, such as the third age people - hereinafter older adults - of an Long-stay institution for older adults (ILPI - Instituição de longa permanência para idosos) in Belém.

CONTEXT OF POPULAR EDUCATION WITH OLDER ADULTS

NEP: Paulo Freire Center for Popular Education

The Paulo Freire Center for Popular Education (NEP - Núcleo de Educacão Popular Paulo Freire) is a teaching, research and extension group of the Universidade do Estado do Pará (UEPA), formed by students (undergraduate and graduate) and professors associated with UEPA. It was created in 1995 by the student organization PROALTO8 and since 2002 it is constituted as NEP.

The NEP bases its popular educational practice on the philosophy (ethical-political) and on Freirean theoretical-methodological assumptions, and is currently affiliated to the Council for Popular Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (CEAAL - Consejo de Educación Popular de América Latina y el Caribe). It develops its activities inside and outside UEPA, in schools, ILPI, hospitals, social assistance centers, urban and rural communities.

This group “develops educational actions with several social segments linked to the popular classes: children, young people, adults, and older adults, in different institutions: hospitals, community centers, nursing homes, and schools. This educational work is dimensioned as a social pedagogy, which considers integrating its educational actions with hospital and peripheral communities, with the non-schooling spaces understood as spaces for inclusive education and popular participation” (MOTA NETO; OLIVEIRA, 2017, p.24).

The NEP is based on dialogue, humanization, questioning, lovingness, respect for orality, praxis, criticality, action based on the generating themes, and the use of varied learning situations as pedagogical presuppositions. At present, the NEP has several lines of research and is constituted by the following working groups:

Milk Bank: whose educational work is aimed at teaching literacy to mothers and fathers of children hospitalized in a public hospital in Belém.

Playroom and Support House: the project works with children, young people and women from a shelter for people from the interior of the state who go to Belém for medical treatment for a long period of time in public hospitals. Its action consists of pedagogical and psychological work with boys, girls, women, young people and adults in this hospital environment.

Special Education Group: develops pedagogical work with students with cognitive disabilities in several public schools in Belém.

Group of Studies and Works on Freirian Philosophy: has been teaching philosophy to children since 2007.

Long-Stay Institution for Older Adults: it is a place where people work with a Freirean perspective, with speech circles, readings, and productions based on the realities of the older adults under the protection of the State.

The Long-Stay Institution for Older Adults (ILPI - Instituição de Longa Permanência para Idosos) is an institution9 for older adults in Belém-Pará. It currently houses 38 older adults in situations of vulnerability and social risk, generally with low socioeconomic status, between 60 and 100 years old and without a support network. They are men and women, physically and economically dependent and semi-dependent. This home has an interdisciplinary team of physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses and social workers who provide specialized assistance to the older adults.

The NEP has been carrying out its pedagogical activities at ILPI since 2006, with a work in which words and dialogue are the main protagonists. During these years, research and undergraduate and master’s degree works in which the older adults are protagonists of the processes of knowledge production have been developed, such as the participatory research of Milene Leal (2017) on the school educational trajectory of the older adults based on their memories.

As with children, it is a pedagogical challenge to keep the older adults’ attention for long periods of time; their thoughts are short term and they easily forget things. The NEP has been developing discussion circles about the territory, traditions, food, and memory, every Tuesday from 9:00 am to 11:00 am. In order to continue with the theme and identify the generating themes for the annual work of the NEP in the institution, it was decided to carry out an exercise of reading and analysis of realities with the older adults, using social cartography and the problem tree, based on the methodology of Participatory Action Research (IAP - Investigación-Acción Participativa).

These techniques were proposed and discussed with the popular pedagogues/educators of the NEP, recognizing the valuable knowledge they already had with them: the older adults of the ILPI like to talk about their past, their tastes, their stories, their Belém and all the cultural baggage that this place means. They like to feel heard, observed and recognized as subjects who carry with them interesting stories, incredible travels, and a life that matters. For this reason, techniques were proposed to incite memory with a specific meaning, to achieve an awareness of oneself, and of a “we”, particular life experiences charged with a common experience: being an older adult in the ILPI.

CONCEPTUAL APPROACH

Social Work: for human rights and social justice

Colombian Social Work is conceived under two epistemological dimensions, in which it develops and defines itself: the professional and the disciplinary dimension. In its professional dimension, Social Work is a social practice that seeks to intervene in social problems, evidenced in human suffering or unfavorable states-situations for human dignity; and in the disciplinary dimension, Social Work is a research practice focused on the theoretical production about social problems (MALAGÓN, 2012).

A social problem is initially an ethical issue since the idea of problem refers to something socially undesirable that implies deprivation or suffering. “For this reason, every social problem implies a negative value judgment, a statement that brings to light evil in any of its expressions: infamy, injustice, inequity, lack of love, lack of solidarity, violence” (MALAGÓN, 2003, p.19).

This is closely linked to an issue of human rights insofar as we are talking about dignified living conditions, and Social Work is committed to an ethical action based on the perspective of human dignity, quality of life, integral health, development and happiness.

Thus, social work is a profession-discipline that analyzes, studies and intervenes in social problems, as evidenced in poverty, suffering, inequality, and countless situations that degrade the human condition. These are situations and concrete conditions (gender, class, race, age, sexual orientation, among others) that have an important influence on the life of each person, however - as mentioned above - do not determine them. Therefore, Social Work - and Popular Education - has an ethical, political and critical social character, because it works with people who live in situations of dehumanization, poverty, discrimination, suffering and seeks the guarantee of their rights and social justice.

Social Work develops in the field of interactions between subjects, institutions, social organizations and the State, in a dialogical and critical manner. It involves intervention referents that constitute the axis that structures the professional practice, giving it a social and political sense to promote social transformation processes (CONETS, 2015, p. 22).

Social Work applies research and intervention in an articulated manner; there is no intervention without research, nor research without social intervention. It is the profession that is characterized by making context analysis with a deep and critical reading of reality and at the same time provides tools for transformation at the micro level - in processes such as Popular Education with the older adults - or at the macro level - as in the formulation, implementation and evaluation of services, plans, programs, projects and social policies aimed at the preservation and defense of human rights and social justice.

The being of Social Work configures, on the one hand, the recognition of the “other” and of “the others” as social and political subjects capable of transforming social realities in the processes of formation, participation, mobilization and collective action; and, on the other hand, the recognition of the structural and conjunctural conditions of the social realities in which the same subjects, the organizations, the institutions and the State are being developed daily (CONETS, 2015, p. 22).

Hence, the defense of Human Rights and social justice are fundamental elements for Social Work in the process of context reading; thus Social Work

is positioned in favor of equity and social justice, in the perspective of universal access to goods and services related to social policies and programs; the expansion and consolidation of citizenship are explicitly put forward as a guarantee of civil, political and social rights of the working classes (NETTO, 2006, p.16).

Based on the premise that social Work is to guarantee and promote Human Rights, which it works against injustice and social inequality, against situations of violence, oppression, poverty, hunger, and unemployment, it was decided to focus on a transforming methodology. That is why we work based on Popular Education and the postulates of Paulo Freire.

Popular Education10, beyond theory, a political choice

According to Marco Mejía (2013), quoted in “Popular Education and Latin American decolonial thinking in Paulo Freire and Orlando Fals Borda” (Educação popular e pensamento decolonial latino-americano em Paulo Freire e Orlando Fals Borda) by Mota Neto (2015), Popular Education is a historical accumulation that becomes a movement and a political-pedagogical proposal. It is characterized by its open political intentionality towards the interests of the people, their struggles and objectives, aimed at a project of social emancipation (2015, p. 106).

Popular Education is not only a professional choice, but also a choice of life. It is a position that crosses, questions, challenges, defies and demands the profession and the life of each subject who decides to assume it. Popular Education is a way to contribute to build relationships from love, listening and the words. Hence, Paulo Freire’s work is not only for pedagogues, but for all oppressed human beings who experience injustice and choose to act in relation to it.

Popular Education is at the same time a movement (a practice, an experience, a process of struggle) and a paradigm (a discourse, a theory, an ideology), that aims, via education, to empower the popular classes to face diverse modes of oppression, thus fighting for a solidary and inclusive society (MOTA NETO, 2015, p. 117).

Popular Education “is an intentional way of doing education from the interests of the popular sectors and a way of contributing to the processes of social transformation” (MARIÑO; CENDALES, 2004, p.10). It is hope, it is life, it is movement, it is justice, it is feeling, it is joy, it is strength, it is love. Popular Education goes through the lives of each person who assumes it, Popular Education is an invitation to transformation and not from a perspective of assistance, Popular Education recognizes the political character of each subject.

METHODOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

The strategies of Popular Education are multiple and diverse, they have their methodological axis in the action-reflection-action, working with them allows to generate dialogic processes with committed and solidary attitudes in the struggle for a dignified life. In the following, it is shown how awareness, the objective of Popular Education and Social Work, becomes a method and a point of dialogue between these two fields of knowledge through IAP (Investigación-Acción Participativa) - Participatory Action Research.

Awareness is in the method

At a conceptual and methodological level, it is considered that the reading of realities or contextualization of the subjects in the world is a fundamental part of the research or intervention processes of Social Work. This reading realities is a process of conscientization, in which the subject is capable of reading and being read, in order to transform the world.

This process of conscientization is important since conscience is the presentation and elaboration of the world; it is the “capacity of the human being to be distant from things in order to make them present, immediately present” (FREIRE, 2005, p. 13)11 and think about them. “But none of them becomes aware separately from the others; awareness is constituted as awareness of the world [...] “ (FREIRE, 2005, p. 15) and awareness of oneself. Thus, awareness is ultimately awareness of the world, with an intrinsic relationship between conquering oneself, becoming more oneself, and conquering the world, making it more human.

The human beings, as a historical subjects and immersed in culture, language, communication and other human relations that allow them be awareness of themselves, of their existence, have the possibility to think of themselves in time and intervene in the world. It is not possible to understand human beings outside of their relationships with the world; indeed, their way of acting is a function of how they perceive themselves in the world. That is why, by participation and dialogue, we seek to problematize reality and transform it (FREIRE, 2005).

Therefore, the most coherent method with the proposal and commitment of Freirian Social Work and Popular Education, in which participation and construction from and for the community is the Participatory Action Research (IAP - Investigación-Acción Participativa)12. IAP was the methodology presented and applied during the process, together with the techniques: social cartography and the problem tree, which made it possible to identify and objectify the reality experienced by the older adults of the ILPI.

Participatory Action Research (IAP - Investigación-Acción Participativa): building from Social Work and Popular Education

According to Ezequiel Ander-Egg (2003), IAP is a methodology that has the purpose of producing profound social transformations, including the promotion of popular participation processes, whether in terms of mobilization of human resources or protagonism of the popular sectors. This is why this methodology is relevant to the NEP’s pedagogical processes, since not only is teaching work is done, but also research and direct intervention processes are carried out with and for the community.

Participatory Action Research implies the simultaneity of the process of knowing and intervening, including the participation of the people involved in the program of study and action.

As research, it is a reflective, systematic, controlled and critical procedure aimed at studying some aspect of reality, with an express practical purpose. As action, it means or indicates that the way of carrying out the study is already a mode of intervention and that the purpose of the research is oriented to action, which in turn is a source of knowledge. As participation, it is an activity in the process of which both the researchers and the people to whom the program is addressed are involved, who are no longer considered as simple objects of research, but as active subjects who contribute to know and transform the reality in which they are involved (ANDER-EGG, 2003, p. 4-5).

IAP is characterized by principles of dialogue, action, reflection, and participation. According to Calderón and López (2013): 1) The horizontal relationship between learner and educator in which it is recognized that each one has a knowledge; 2) The practice of conscience based on collective reflections; 3) The rediscovery of popular knowledge in which the accumulated knowledge of social collectives is recognized, ordered, validated and empowered; 4) Action as a central element of training; 5) Active and critical participation in the reflections of the actors that allows the possibility of acting with equality, being the educator-researcher a member of the collective, who puts his or her knowledge at the service of such reflection (strengthening and systematizing it) (CALDERÓN; LÓPEZ, 2013, p.5-6). These principles are articulated with the assumptions of Social Work and Freirian Popular Education that the NEP manages.

IAP as a method of awareness raising is the bridge on which Social Work and Popular Education are made. This bridge is based on the active participation of the subjects, since it allows reflection-action in which the cognitive subjects are capable of analyzing, questioning and transforming their reality.

Thus, during the intervention period, the generating themes were identified and chosen by the participants, and in turn the actions were directed towards these themes. The participation of the subjects was evidenced in the identification of generating themes and in the problematization of them, since these themes are part of their reality and place them as protagonists.

Techniques

Given the dynamics of the group, social cartography and the problem tree were applied as participation techniques in which the spoken word and non-verbal language (drawings) prevail, and by recording, socializing and interpreting them, the value of the knowledge that the subjects and communities have within themselves is recognized.

Social cartography

Social cartography is a methodological tool that through the individual and collective construction of maps provides a comprehensive reading of reality by rescuing the oral narration and memory of a group or community. There are three types of maps: the eco-systemic-population map, which refers to territorial relations; the temporal-social map, which explores the tensions of the past, present and future; and the thematic map, which shapes specific problems and planning (BARRAGÁN GIRALDO, 2016. p.257)13.

It was proposed to start with social cartography as a work methodology in ILPI because it allows the dialogue proposed by Popular Education, and it is based on the notion of territory14.

Problem tree

In this section, the Problem Tree will be presented as a technique that is part of the methodology used in the diagnostic phase of social work intervention projects, useful for the pedagogical scenarios of the NEP.

Social Work is characterized by the planning, execution and evaluation of social intervention and research projects. These intervention and social research projects can be guided by different methodologies. The logical framework approach is generally applied in social investment projects, since it is characterized by organizing projects in a synthetic manner by means of objectives, results and activities. These projects are characterized by having: concrete and verifiable aims and purposes; precise, planned and interconnected activities to achieve the purpose; concrete results (which are based on the situation to be transformed); established resources; the time determined for their execution; and the people responsible for the execution of the activities.

For this, the project must be developed in a cycle or stages: identification, formulation, execution-monitoring and evaluation. Identification is the phase that interests us, because it is in the phase when problems affecting the community are identified and the objectives or alternative solutions are proposed.

However, as we are in Popular Education scenarios, the rigidity and “effectiveness” of social projects with the logical framework approach are not assertive in the dynamics of Popular Education of the NEP, so this technique is applied from the IAP.

The main principle of IAP could be summarized as research and knowledge of reality in order to be able to act; that is, to study the problems, needs and interests of the population involved in order to seek social transformation with and from them.

This is why it is fundamental to recognize the problems and interests of the population. Initially, social cartography was proposed; however, due to the dynamics of the older adults group, it became evident that the motivation and collective initiatives were low, and more oriented and motivating activities were needed. Thus, it is proposed to articulate the technique of drawing and map the problems (as suggested by social cartography) in the location and classification of the problem tree technique.

The problem tree is a “participatory technique that helps develop creative ideas to identify the problem and organize the information collected, generating a model of causal relationships that explain it. This technique facilitates the identification and organization of the causes and consequences of a problem [...] The trunk of the tree is the central problem, the roots are the causes and the top is the effects. The logic is that each problem is a consequence of those below it and, in turn, is the cause of those above it, reflecting the interrelationship between causes and effects” (MARTÍNEZ; FERNÁNDEZ, 2008 p. 2).

Description of the process

The group of popular educators in charge of the process at ILPI is led by two NEP pedagogues. They have maintained the pedagogical work in the institution and actively supported the co-construction of the process during the Social Work internship. During this time, seven meetings were held in which, as the group and its individual and collective interests were recognized, proposals for participation and dialogue were developed jointly with the educators and older adults.

Recognition and identification

In the first and second 15 sessions, an observation, listening, recognition and identification exercise was carried out. During the first session, the educators conducted the activity of presentation and introduction to the group. In order to achieve horizontality, they chose to participate together with the older adults in the same activity. This allowed the participants to get to know the educators better.

This observation shows that the mood of the older adults decreases with time and participation is not active; not everyone present participates in the activities. It was identified that this group is characterized by getting tired quickly and speaking individually, there is no collective listening, each participant speaks to the educators individually and their participation in the group16 is restricted.

Social Cartography: Belém in the Past

The individual and collective elaboration of a map of Belém in the past was indicated. The group was asked to individually elaborate the neighborhood or the places where everyone lived, and then, they were instructed to build the map of Belém together. The individual instruction was understood and executed, however, participation was not very active during the process of the collective map, they almost did not speak when asked in group; in the end, in the drawing of the collective map they chose to draw individually, not elaborating a common work.

During the collective moment we tried to encourage the group to draw freely, but it was not possible; they used to work with simple and mechanical instructions. So for the following sessions the methodology had to be modified, so that the instructions were easy to understand with an invitation to think and reflect on their realities.

Two important events are highlighted from this session: first, the educators arrived one hour before the activity to prepare the space in the maloca, and found that Mr. Manuel was already there waiting for them. “Mr. Manuel showed the Charter of the Statute of the Older Adults, which provides their rights. And while the work tables were being organized, a conversation was held on the importance of knowing the rights of the older adults”17. This dialogue was valuable because it evidenced Mr. Manuel’s interest in the activities and the intention of them, by identifying in the NEP the relevance of Human Rights and the importance of recognizing them as subjects of rights.

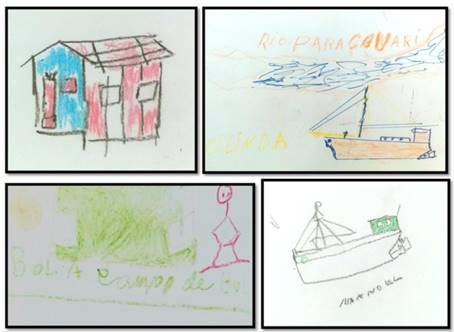

Second, the importance of the territory in the constitution of the lives of each older adult “the participants of the experience remember the places of work, some evoke their places of birth, the places where they used to work… One of them worked on Nazaré Avenue, others at the market, at the railway terminals; they also remembered the river, the beach, the soccer fields, their homes and the people who were part of these places, the women, grandmothers, fishermen” (NEP, 2018) (Figure 1). The importance of places is not only constituted by the physical space, but also by the people and particular elements that characterize it; territories are constituted by a network of relationships, meanings, situations full of stories, emotions and life. See figure 1 18.

Mr. Manuel19 talked about what he drew, he drew a boat and a house, when the educator asked him what this drawing represented, he explained that it represented everything he had already done and the places he traveled to. His drawing - he says - refers to the happy moments of his life, when he worked on the boats, the work that sustained his family and that today he misses so much. Mr. Manuel loves to talk about his travels and always recognizes himself as a sailor - in present time (NEP, 2018, p. 4).

Social cartography: past-present

In the first part of this session, it was decided to take up social cartography in the past in order to delve a little deeper into the subject of the places that constituted the past of the older adults of ILPI. It was proposed to remember the drawing they did, and participation was encouraged with questions about the drawings.

Given that the older adults did not have the same participation to speak in public as with the educators, it was decided to listen individually to each participant, and then the educators quickly socialized what each one spoke, redirecting the questions and giving voice and protagonism to each older adult. This proposal was successful, because they began to speak more fluently, however, it was noted that attention was only obtained when an educator was speaking and not when any of the older adults was participating, so the group was challenged to listen to the others with the same attention.

In a second moment they were instructed to make a map of the present, of the places that they currently like, the instruction was delimited to the places of the institution, considering that it is the space they currently inhabit. Most of them drew the maloca, scenario in which the activities are developed, and they said that they like them because “here we take a breath of fresh air, we talk and do activities that distract us”; “here we listen to music and do activities, it is a way to get away from the noise of the main hall of the house. Although all the places here are good, the people are good and we are well-treated here”, Mr. Manuel drew the roof of the maloca, he emphasized that it was an indigenous structure -circular- and he liked it (Figure 2), they also drew places of interaction such as the television room and the dining room. The group member, Josefa, expresses her interest in food and the pleasure in the “dining room” where they eat, watch TV and talk, she says she likes açaí with tapioca, and with great emotion - opening her eyes and tasting her lips - she remembers the cupuaçú jam with bread, flour, and tapioca with cheese and butter (NEP, 2018).

Social cartography was useful to identify objective and subjective realities of each older adults and the group in relation to the topics discussed. For example, when talking about what they like and what they don’t like, the topic of food was discussed; when “Mrs. Antonia draws a plate of rice, beans, flour and water, she said that she doesn’t like that because that’s what she always eats when she has no money, that’s all she has to eat” (NEP, 2018, p. 3). Thus exposing how difficult her economic situation was and her relationship with food.

Mrs. Antonia makes reference to food quality as something important. It is evident that food is something transversal in the older adults, not only in the past, because of the food typical of the region (such as açaí and fish) to which they no longer have access, and which are fundamental in the constitution of their territorial identity as a paraense20, but also the problematization of the quality of food. In the past, for various social and economic reasons, they did not have access to quality food, eating only water, rice, beans and flour; when now their breakfast is always “banana jam” and they do not have access to açaí in a “free” way.

Social cartography invited us to think about the ways in which we can decolonize hegemonically instituted fields of knowledge in order to constitute subjectivity (BARRAGÁN GIRALDO, 2016, p. 259). For example, during the social cartography sessions, Mr. Manoel, Mrs. Olinda, and Mr. José were characterized by constantly drawing the boats, as elements in common, and as an element that “represents life”. Mr. Manuel says “it represented everything I already did and the places where I traveled to” (Figure 3). Thus, boats are seen as a common territory, for the people who worked on them during their lives, but also for the rest of the participants, who had boats in their landscape, because they were an important means of transportation in Belém, or because many times the family economic dynamics were involved in the dynamics of the boats21.

Initially, this social cartography exercise was intended to be historically charged, in order to situate the participants as historical subjects, active in their own reality. However, due to the group dynamics22 , the expected participation and collective work in relation to the territorial problematization was not achieved, so the development of cartography as a technique was continued and it was proposed to work on the Problem Tree from the Participatory Action Research as a methodology, in order to identify the generating words and themes, an input for the work process during the rest of the year.

Current social cartography - Problem tree

This session was important because a real work of collective listening was achieved, everyone remained silent and really listened to what their peers were talking about. Usually, as was reported about the first meetings, a collective silence prevailed when the educators asked the group to speak, or everyone spoke at the same time and they did not listen to each other. On this occasion, they listened and started talking, respecting each other’s speaking time.

It was also significant because the challenge of the first cartography session, in which all those present in the activities were active and participative subjects, was achieved that day because they actively participated; when Mr. Manuel identified the triggering theme (Figure 4) ‘health as a problem’23, Mrs. Josefa also said “I also have a diabetes problem”, and Mrs. Filo also said that she had diabetes problems, Mrs. Maria said that she did not have diabetes but high blood pressure, then everyone began to talk about their physical ailments (NEP, 2018).

When they started the conversation by asking about the causes of ill health, or what it means to be sick, they emphasized care, and the consequences, delved into pain that goes beyond the body, and the importance of family and friends (support networks) in situations of pain.

After placing health as a central theme, the participants recognize as causes: lack of basic sanitation, referring to garbage in the street; lack of drinking water and medicines; sedentary lifestyle; rain; poor nutrition etc. As consequences they affirm that not having health “everything is bad” there is discomfort, pain not only in the body but pain in the soul; there is an atmosphere of sadness and suffering in the person and in the family; there is a lot of stress and one has to be looking for a cure (NEP, 2018, p. 4).

By means of social cartography and the problem tree, problems experienced individually and collectively by the older adults were identified. They also mentioned violence as an important issue, and although the older adults did not “directly” feel the violence transmitted by the city’s news programs, they know what is going on. On that day, different types of violence were discussed: gender violence “Mrs. Brandão drew a girl and exposed physical violence, abuse and child labor (especially child domestic labor of girls)24; [...]Mrs. Filomena emphasized the violence and danger that blind people face when they are alone in the street”. This evidences how each person spoke from their locus of enunciation, in this case they spoke as women, and as persons with disabilities. The interesting about this session was that the participants reached a consensus on health as an issue that affects everyone. They recognized that many of the problems they experienced individually were also collective experiences.

Problem tree - objectives

In this session, a sensitization activity was carried out, prior to the objectives tree. The participants were instructed to close their eyes and listen to the song “Eu só peço a Deus” (I pray to God) by Mercedes Sosa and Beth Carvalho, a song that invites to reflection and also to action. After this moment, they were asked to draw or write a letter to someone in the future, informing what is really important, what should be protected and maintained over time. Participants responded: “it is important to go out to work, make money”; “health, good home, happiness, bread, life, the walks, the fridge full of food”; “health, being free of diabetes, high blood pressure” (here, just like the previous session, several people also manifested having diabetes and other people high blood pressure, hypertension); “help to live well”; “play, the sun, because it gives us life and dries clothes, food, and Pará (the place where I live, where I was born)” ; “work in the boats, it is everything I did”; “the boat represents life”; “God is important to me because he helps me to live well”; “someone from the future, take care of the others” (NEP, 2018).

At this point, the importance of the contribution of each one of them was socialized, and at the end, the conclusion was reached that health is one of the common themes for human well-being, and that, although the letters have been prepared individually, there are common elements such as the importance of food and work in everyone’s life.

The tree session was taken up again, and the issue of health was further problematized. During the conversations, the topic of work and child labor arised. The relationship between health and old age was discussed, in which old age is problematic because of its relationship with health, however, it is also affected by a question of social class, because as one of the participants said “the poor are the ones who die waiting in line at the hospitals”. They were asked who worked when they were children and they all nodded in agreement, Mrs. Filomena and Maria raised their hands and said that they had to transport clothes and wash other people’s clothes. Mr. Edimarino said he had to transport clothes from Pedreira to Ver-o-peso25 (approximately 5 km), several times a day and that he was tired when he arrived.

To close this session, they were asked to propose possible solutions to all the problems they had stated, to which they responded: taking medicine, eating well, sleeping, getting up early, get some fresh air in the morning, doing physical education, walking, watering plants, and having a good relationship with God (spirituality) are necessary actions for good health (NEP, 2018).

Farewell and closing of the process

Since the time of the academic stay ended, a cultural closing was held with music and traditional food: açaí with tapioca26, exposing the work done during the last two months: Social Work, Popular Education, social cartography, the tree of problems and the IAP, as part of an exercise of reading realities, photographs and visual material resulting from the process were exhibited and an invitation was extended to continue working on the reading-reflection and action of reality (Figure 5).

It was remembered how these last cares they mentioned (eating well, sleeping, getting up early, get some fresh air in the morning, walking, among others) are important and have a relationship with the recognition of their territory, their dynamics and the development of their lives, the sessions in which they talked about the experiences of child labor and the possibilities of self-care that older adults had during their lives and that they have now were evoked. They proposed the self-care and care for others as the possibilities of being and doing in the present, having the NEP as an ally.

After a moment of music, acknowledgements and informal conversations with the guests (teachers and participants of the NEP and external musicians), it was decided to play guitar and sing the song “Só peço a Deus” (I pray to God), thus closing the process.

REFLECTIONS ON PRACTICE

The main contribution made by the Social Work internship to the NEP educational scenarios at ILPI is the implementation of participatory techniques and methodologies in diagnostic exercises, contextualization, and reading of realities; which leave as input and starting point, at a conceptual and methodological level, the design of educational projects with emphasis on social action.

At the methodological level

Social cartography and the problem tree under IAP are useful participation techniques for diagnostic processes and reality reading in work groups, under a critical view of Popular Education. With the ILPI older adults group, these techniques were successful because there was a clear interest in talking about their territory, their life histories and their individual and collective experiences, past and present. The following is a brief description of the main contributions of these techniques in this process.

The cartography

Cartography was proposed as a mean to recover the word. It is a technique that made it possible to articulate the knowledge and activities already developed at ILPI and to propose the territory and its dynamics as a problematizing and thematic axis. With the cartography, conflicts were visualized and located, such as food; identity patterns of the population were identified, such as the fruits and the river, and situations such as the different types of violence were denounced.

Territory was considered to be a subject that generates insofar as it contains elements that construct subjectivity. Territory is a social construction that develops from the meanings and uses that individuals construct on a daily basis, based on common histories, uses and meanings (FERNANDO; GIRALDO, 2016). As evidenced in the first social cartography session, when we talked about Belém (Pará), we talked about constituent elements of the city, the state and even the country, such as mango, açaí and tapioca, elements that were and are part of its life history.

Social cartography made it possible to recognize events that remain in the group’s memory, and led to an understanding about the present and to outline future possibilities for action.

The problem tree

The Problem Tree technique was proposed to locate and organize the problems identified by the older adults and propose a pedagogical action-research project for the rest of the year. For this reason, the following generating words are presented, as a result of the classification of the problems and needs that older adults considered appropriate to analyze in order to find solutions to these problems. This task is carried out on the basis of specific issues and immediate experiences presented by the population and simultaneously collected and organized together with them in the problem tree.

One of the most important contributions of Social Work (and of pedagogues) is to systematize and give back to people the contextualized problematic experiences, showing that there are not individual and abstract needs, problems and interests, but that they are all directly or indirectly related to each other27. This technique also made it possible to systematize the problems in generating themes, and at the same time subjects were placed as an active part of this network of relationships, thus placing them as participating subjects and transformers of their own reality. In addition, it should be noted that the methodology (IAP) allowed significant experiences that resulted from the process as a commitment to a pedagogy towards the human.

Towards the pedagogy of the human

It is bold to say that an awareness-raising exercise was achieved in the short time that was shared with the older adults. However, considering that “awareness is the critical insertion of the oppressed in the oppressive reality, and by objectifying this reality, the subjects can act on it” (FREIRE, 2005, p. 42), it can be affirmed that through social cartography and the tree of problems an exercise of critical insertion in reality was carried out, which is only the first step for a critical pedagogy.

The pedagogy proposed by Paulo Freire as pedagogy of the human has two distinct moments: the first, in which the subjects unveil the world of oppression and commit themselves in praxis to its transformation through a critical reading of reality; and the second, in which the subjects expel the myths created and developed in the oppressive structure (FREIRE, 2005). During the process with the older adults, this first moment of reading and critical analysis of reality was achieved.

During the development of the activities, several emotional and reflective moments arose, both individually and collectively. Considering that “The place of encounter and recognition of consciences is also the place of encounter and recognition of oneself” (FREIRE, 2005, p. 20), two important moments stand out: when talking about child labor and care for others.

When asked who among them worked when they were children, they all nodded in agreement. Mr. Edimario provoked a debate about capitalist society and class struggle, he emphasized that “poor’s people life is not easy”, he explained why work and money are so important. He continued the stories, explaining that he worked since he was 9 years old, he helped his mother carrying clothes buckets on his head, he lied to his mother saying he was going to school, meanwhile he was working as a seller at the Ver-o-Peso Market. This day, several people began to narrate their childhoods, which were marked by work, scarcity, abandonment and even begging, the group was immersed in a collective nostalgia, they remembered their hurt childhoods… The group provoked and maintained a deep silence, and with a voice of hope Mrs. Josefa closes the space “but it is forbidden now, now the children must go to school”.

The second moment of deep reflection felt in the group was when in the problem-objective tree they were instructed to draw and write a letter “for someone in the future”, indicating what was important in the past, now, and what should be preserved for the future. Mrs. Rosinha in her drawing says that it is important for her to “take care of others”, and everyone was asked if this is important or not. Everyone said yes, and then they were immediately asked if they take care of others, or of their colleagues. The group reacted by looking at the floor and giving a mumbled negative response. The silence of the group was respected and the invitation was made to build in their present everything that was, is and will be important to them.

The aim is for the educator and the learner to establish an authentic way of thinking and acting, thinking of themselves and the world simultaneously, without dichotomizing this thinking from the action (FREIRE, 2005). Based on the relationships recognized by the older adults in the social cartography and the problem tree, it was possible to identify the relationships (with the problem tree) and the meanings (with the social cartography) of the constituent elements of themselves as individuals and as a group. These techniques make it possible to problematize and resignify the significant and constitutive elements and situations of people, based on an exercise of critical reflection about reality.

The group achieved critical insertion in reality, as these techniques allowed the older adults to analyze how their life stories and experiences responded to a specific historical context with specific socio-cultural dynamics, which have allowed their lives to pass through a matrix of oppression crossed by poverty, in this case.

In the cartography, Mrs. Antonia related that her house was made of mud, very simple. Mr. Manuel points out his stilt house, and Antonia talked about the economic needs her family experienced, the looks and the listening became empathic, remembering her own experience.

Mr. Edimarino emphasized the disrespect towards the older adults and the authoritarian education, stating that “Poor’s life isn’t easy”. Besides, he explained that work is so important, “because it gives us money” and everything would be different with or without money. In turn, Filomena brings up the class struggle discussion, stating that the “Poor person is humiliated; they [the politicians] only do what they want. It’s hard to change other people’s minds. It’s necessary a change in everyone. Not everyone, some people change, others don’t, there are arrogant people, who think they are better” (NEP, 2018, p. 8).

The discussion was restarted when working with the problem-objective tree. They were asked to propose solutions to the problems identified during the meetings, mainly health; however, they did not participate very much. For this reason, they chose to talk about Paulo Freire and the importance of reading the world in order to read and transform reality. One of them stated that “I did not know how to read, and that is why I was and I am a stupid. I didn’t go to school because I went to Ver-o-Peso to work, to make some money. One day my mother saw me, and she told me that’s why I didn’t learn and wouldn’t learn, if I wanted to be like that all my life” (NEP, 2018, p. 9).

The dialogue was not reduced to the act of reading books or written words, but was directed to reading as part of an exercise of a critical reading of the world, of reality. A short story was presented in which the lecture received other meanings. This story was based on an observation on the way to ILPI: two children of approximately 7 and 9 years old, very early in the morning walking on the streets of Belém, harvesting mangoes to sell them later. After remembering their own childhoods, they were invited to think about the children who work in the streets since they were very young, they were asked if these children know what it means to work, to get money; if they know how to work to bring some food to their homes; and if they don’t know what life is like. The older adults answered yes. Based on this, it was suggested that just as children who work since they are very young understand how the world “works”, a precarious world in which they have to work to obtain food, it is also necessary for people to understand what they have to do to have a dignified life. But part of this pedagogy is not merely to understand “how the world works”, but to problematize it, to problematize their own experiences, to see them, describe them, analyze them in order to transform them. This is the aim of Popular Education. And therefore, their own life experiences were problematized, which at first seemed individual, and in the end resulted in common experiences.

A critical insertion in reality was achieved by discovering, as stated by Freire and Betto (1994), that there is no personal crisis, but personal ways of feeling collective crises. The older adults admitted that although each one lived their lives independently, their life histories are marked by common experiences of oppression, poverty, abandonment, child labor and health, deteriorated in part by the impossibility of caring for their own lives and bodies. This analysis allowed us to reflect on the present and the possibilities for action by the older adults in terms of selfcare and care for others. During the conversations it became evident how the older adults assumed themselves as subjects requiring care. From these dialogues it was proposed to them in their routine at ILPI, to be caretakers of themselves, of others (listening, sharing and talking with the colleague) and of the other (the plants, the home) as a political commitment.

Regarding the participation of the older adults, motivation was raised as a challenge and the motivation of them was questioned as in the case of a work team. At times - particularly at the beginning - the older adults were not very participative or justified their passivity with “not knowing”. In cartography, for example, Mrs. Maria, at one point, was insecure about starting to draw the map and said that she did not know how to paint. Later, at the collective moment, several participants responded that they did not know how to draw a map, even when they had already advanced their individual drawing. Why do they not want to participate? How can we awaken their curiosity?” In view of this, Freire (2005, p. 55-56) states that:

This fatalism, prolonged in docility, is the result of a historical and sociological situation and not an essential characteristic of the people’s way of being [...] self-devaluation is another characteristic of the oppressed that results from their introjection of the oppressors’ vision of them. Hearing so much about themselves being incapable, that they know nothing, that they are sick, all this ends up convincing them of their “incapacity”.

To this end, it must considered that what mobilizes the population is the satisfaction of their primary needs, their problems and everything that contributes to their personal, family, group or community satisfaction. It is about identifying the problem areas and, within them, identifying the specific problems that we want to and can solve. In this process, health was the mobilizing theme. For this reason, the following categories are proposed as key words and themes to continue working with the older adults of ILPI.

At the theoretical level

It is necessary to read the world and understand reality in order to transform it. With this process, social cartography and the problem tree were used as participatory techniques in which the knowledge, interest and experiences of the older adults are rescued and analyzed from a critical perspective. As stated by Santos (2018, p. 544):

Only the past as an option and as a conflict is capable of destabilizing the repetition of the present. Maximizing this destabilization is the aim of an emancipatory educational project. For that it has to be, on the one hand, a project of memory and denunciation and, on the other hand, a project of communication and complicity.

Ensuring that the older adults improved their participation in the spaces by talking about their interests, their current and historical problems, is considered a great success of the process, in addition to rescuing the following categories based on the dialogues and analysis of the older adults.

The problem tree allowed the identification of the relationships between the categories Health and Work as a basis for a deep and serious academic review. 28. It begins with old age as a fundamental category in order to locate the subjects in the space-time they are currently living at an individual and collective level. The group chose health as the central theme because it is a problem that is experienced by all of them. The category of work is proposed because it is a topic that was present in almost all the sessions without being planned (by the educators) and work is considered a constitutive element of the human being. Finally, gender is proposed as a theme since there are several women in the group and many of them have experienced sexual, physical and symbolic violence and have resistance against men.

As a result of the internship, we intend to propose the categories resulting from the identification process as a summary of themes to develop with participatory perspectives or methodologies. This being an input for the joint elaboration of a pedagogical intervention project for the future.

Thus, at the methodological level, it is suggested to continue working with the Participatory Action Research proposed by Orlando Fals Borda and Paulo Freire, where research is based on action and action is based on research.

Continuing with the importance of reading reality, it is proposed to first work on old age, as a condition in which the older adults find themselves, and as part of the process of understanding that pedagogues must carry out before, during and after the pedagogical work.

Old age, health, work and gender

We propose to conceptualize old age and at the same time question why it is problematic (if they assume it to be problematic).

Monica de Assis (2005) quoting Ferrari (1999) states that: Human aging is a universal, progressive and gradual process. It is a diverse experience among individuals, for which a multiplicity of genetic, biological, social, environmental, psychological, and cultural factors contribute. There is no linear correspondence between chronological age and biological age. Individual variability and differentiated aging rhythms tend to be accentuated according to the opportunities and constraints existing under given social conditions (p. 2-3).

Old age is a heterogeneous reality for each person, but if it is possible to find points of convergence between the social, environmental and cultural factors of each older adult, a collective conception of the meaning of old age in the ILPI can be constructed. It is suggested to start by identifying how the older adults conceive the relationship between old age and health -a category identified by them-; health and work29; old age and gender. And from there, work from an intersectional perspective is recommended. “The idea of ‘intersectionality’ aims to capture the structural and dynamic consequences of interaction between two or more forms of discrimination or systems of subordination [such as class, race, age, etc.]” (UNZUETA, 2010, p. 25).

It is suggested to consider: historical and cultural times, social classes, personal histories, educational conditions, lifestyles, genders, professions and ethnicities, which allow us to understand old age as the result of a network of situations in permanent interaction with multiple dimensions of living. “The observation of differentiated aging patterns and the search to understand the determinants of longevity with quality of life have motivated studies in the line of understanding what would constitute good aging” (ASSIS, 2005, p. 2).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Social Work internship in the process of Popular Education with older adults provided several theoretical and methodological lessons. One of vital importance is the flexible methodology, which can be adapted to the needs and desires of the group, in order to guarantee the appropriation and participation of the group in the process, in this case two techniques were applied in order to achieve the objective of reading and analyzing the reality with a critical and collective character.

At the methodological level, it is also important to highlight listening among all participants as a fundamental element in the development of the educational processes. Allowing the participants to play an active role enabled them to take ownership of the space in a different way, which resulted in greater and better participation by the older adults.

Based on the relationships recognized by the older adults in the social cartography and the problem tree, it was possible to identify the relationships (with the problem tree) and the meanings (with the social cartography) of the constituent elements of themselves, as individuals and as a group.

Health was the generating theme, because Mr. Manuel was able to symbolize it in the right way, and it is also a problem that all older adults live or have experienced. When they analyzed the causes and consequences historically, they showed that in many cases the care they refer to for good health is also part of a privilege and economic/class possibilities. As they used to say “poor’s life isn’t easy”. Growing up in difficult economic conditions, child labor and systematic violence on the bodies of the older adults allowed us to understand that there are social phenomena, such as child labor and poverty, which are experienced from our particular life stories.

These techniques made it possible to problematize and give new meaning to the elements and situations that are significant and constitutive of people, based on an exercise of critical reflection about reality. Turning the process into an awareness-raising exercise, in which the method: IAP-Participatory Action Research was the point of dialogue since it was built from Popular Education and Social Work. It can be affirmed that by means of social cartography and the problem tree, an exercise of critical insertion in reality was carried out, which is only the first step towards a critical pedagogy.

Finally, it should be noted that this article is the result of the systematization and analysis of the process as a sample of reciprocity with the NEP group and the older adults of the ILPI. In this experience, giving back to people the contextualized problematic experiences, allowed us to understand that there are no individual and abstract needs, problems and interests, but that they are all directly or indirectly related to each other. That is why an intersectional analysis between categories is necessary, under a clear ethical and political perspective: the struggle for a dignified life.

REFERENCES

ANDER-EGG, Ezequiel. Repensando la Investigación-Acción Participativa. Buenos Aires: Editorial Distribuidora Lumen SRL, 2003. [ Links ]

ASSIS, Mônica de. Envelhecimento ativo e promoção da saúde: reflexão para as ações educativas com idosos. Revista APS, vol. 8, n. 1, p. 15-24, jan./jun. 2005. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Estatuto do Idoso. Lei no 10.741, de 1º de outubro de 2003. Dispõe sobre a Política Nacional do Idoso, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

CALDERÓN, Javier.; LÓPEZ, Diana. Orlando Fals Borda y la investigación acción participativa: aportes en el proceso de formación para la transformación. Memoria del I Encuentro hacia una Pedagogía Emancipatoria en Nuestra América realizado en el Centro Cultural de la Cooperación Floreal Gorini, 2013. [ Links ]

CONETS. Codigo de Ética para los Trabajadores Sociales en Colombia. Consejo Nacional de Trabajo Social. Ley 53 de 1977. Decreto reglamentario N°2833 de 1981. Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [ Links ]

ESCOBAR, Arturo. Sentipensar con la tierra: Nuevas lecturas sobre desarrollo, territorio y diferencia. Medellín: Ediciones UNAULA, 2014. [ Links ]

FERNANDO, Diego; BARRAGÁN, Giraldo. Cartografía social pedagógica: entre teoría y metodología. Revista Colombiana de Educación, n. 70, p. 247-285, 2016. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogía de la autonomía: saberes necesarios para la práctica educativa. México: Siglo XXI, 2006. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. 42ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2005. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo; BETTO, Frei. Essa escola chamada vida. São Paulo: Ática, 1994. [ Links ]

LEAL, Milene Vasconcelos. Trajetória educativa escolar: memória de idosos. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). 118f.Universidade do Estado do Pará, Belém, 2017. [ Links ]

MALAGÓN, Edgar. Trabajo Social: ética y ciencia. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2003. [ Links ]

MALAGÓN, Edgar. Fundamentos de Trabajo Social. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2012. [ Links ]

MARTÍNEZ, Rodrigo; FERNÁNDEZ, Andrés. Árbol de problema y áreas de intervención. México: CEPAL, 2008. Recuperado el 02 de Mayo de 2018, de : Recuperado el 02 de Mayo de 2018, de : https://serviciosenlinea.comfama.com/contenidos/servicios/Gerenciasocial/html/Cursos/Cepal/memorias/CEPAL_Arbol_Problema.pdf [ Links ]

MEJÍA, Marco Raúl. Posfácio - La Educación Popular: una construcción colectiva desde el sur y desde abajo. In: STRECK, Danilo; ESTEBAN, Maria Teresa (Orgs.). Educação Popular: Lugar de construção social coletiva. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2013. [ Links ]

MOTA NETO N, João Colares da. Educação popular e pensamento decolonial latino-americano em Paulo Freire e Orlando Fals Borda. 368f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, 2015. [ Links ]

MOTA NETO, João Colares da.; OLIVEIRA, Ivanilde Apoluceno de. Contribuições da educação popular à pedagogia social: por uma educação emancipatória na Amazônia. Revista de Educação Popular, v. 16, n. 3, p. 21-35, 2017. [ Links ]

NEP. Relatório das atividades pedagógicas na ILPI. Belém: NEP, 2018. [ Links ]

NETTO Paulo, José.. A construção do Projeto Ético-Político do Serviço Social. In: TEIXEIRA, M. et al (Orgs.) Serviço Social e Saúde: formação e trabalho profissional. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006. [ Links ]

OXFAM. Ocho personas poseen la misma riqueza que la mitad más pobre de la humanidad. 2017. Recuperado el 20 de mayo de 2018, de: Recuperado el 20 de mayo de 2018, de: https://www.oxfam.org/es/sala-de-prensa/notas-de-prensa/2017-01-16/ocho-personas-poseen-la-misma-riqueza-que-la-mitad-mas [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. Educación para otro mundo posible. In: SANTOS, B. S. Construyendo las Epistemologías del Sur: para un pensamiento alternativo de alternativas. (vol. 2). Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2018. [ Links ]

VÁZQUEZ, Guillermo. Elementos para una interpretación filosófica del joven Marx. Revista Controversia, n.115-6, p. 55-63, 1983. [ Links ]

UNICEF. Estado mundial de la infancia. 2016. Recuperado el 20 de Mayo de 2018 de : Recuperado el 20 de Mayo de 2018 de : https://www.unicef.org/spanish/publications/files/UNICEF_SOWC_2016_Spanish.pdf . [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE COLOMBIA. Guía para la formulación de proyectos considerando la metodología del Banco de Proyectos de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia (BPUN). Medellín: Centro de Publicaciones Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Medellín, 2016. [ Links ]

UNZUETA, María Angeles Barrère. La interseccionalidad como desafío al mainstreaming de género en las políticas públicas. Revista Vasca de Administración Pública, n. 87-88, p. 225-252, 2010. [ Links ]

3The translation of this article into English was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES-Brasil.

5OXFAM (2017). Ocho personas poseen la misma riqueza que la mitad más pobre de la humanidad. Access on: May 20, 2018. Available at: https://www.oxfam.org/es/sala-de-prensa/notas-de-prensa/2017-01-16/ocho-personas-poseen-la-misma-riqueza-que-la-mitad-mas

7“The National Policy for Older Adults (PNI - Política Nacional do Idoso), instituted by Law nº 8.842, in January 4th, 1994, regulated by Decree No 1.948, in July 3rd, 1996, and the Older Adults Statute, law No 10.741/2003, regulate the rights assured to people aged 60 years or more. The Older Adults Statute is intended to regulate the rights assured to people aged 60 years old or more”.

8Programa de Alfabetização de Jovens e Adultos: Processo social para libertação (PROALTO - Youth and Adult Literacy Program: Social Process for Freedom)

9Regulated by Chapter II of the Statute for the Older Adults, Federal Law No. 10.741 of October 1, 2003.

10This paper discusses the Popular Education with initial capital letters, because we refer to educational works with a Freirian perspective and not in the sense of public instruction for all, another possible conception of popular education. (MOTA NETO, 2015).

11The references are translations or literal interpretations of the book “Pedagogia do Oprimido” (2005), Editorial Paz e Terra, by Paulo Freire (in Portuguese).

13At the beginning it was proposed to work on temporal social cartography, and later on thematic cartography, however, in the execution of the sessions it resulted in a combination of historical and thematic cartography.

14Understood as a socialized and culturized space in which the environmental, economic, political, cultural, social and historical issues of the subjects converge. Territory is defined "as a collective space, composed of all the necessary and indispensable places where men and women, young and old people, create and recreate their lives [...] a living space where ethnic, historical and cultural survival is guaranteed" (ESCOBAR, 2014, p. 88).

15Of the seven meetings, six developed concrete activities inside the institution. The second meeting was held in the Parque Estadual do Utinga, in Belém, and in addition make some activity, a listening and dialogue exercise was carried out with the older adults during the walk through the park. This was a continuation of the exercise of recognition and identification of the population.

16This refers to the fact that the older adults prefer to talk to the educators, and when the whole group is asked to speak, participation decreases.

21Based on this, it was suggested to take the boat (the ports, the ships) as a generating theme or element of analysis with which to build knowledge from them and for them, not only as a memory strategy but also as an articulating element with the work and the territory, since Belém is characterized by a busy maritime movement.

23This moment was significant because Mr. Manuel drew a heart and the instruction was to draw what they consider problematic, when we asked why he drew a heart, he answered that he suffers from heart disease, has problems with blood pressure and diabetes. The fact that he drew a heart aroused the curiosity of all the participants (Figure 4).

24Child domestic labor is a very frequent phenomenon here in Pará, and consists in the fact that GIRLS leave their homes at a very young age to work in the homes of families in the city. This phenomenon exposes the girls to greater vulnerability and they may suffer abuse and violence of all kinds.

25Pedreira is a neighborhood in the western part of Belém and Ver-o-Peso is one of the oldest public markets in Brazil, located in the Cidade Velha district in eastern Belém.

26Tapioca is the flour extracted from the cassava root, a food of indigenous origin widely consumed in the region. Açaí with tapioca was chosen because these foods have a symbolic value for the older adults, and are considered their favorite foods.

28In one of the sessions this was discussed with the older adults and the influence of child labor on the health of the older adults of the ILPI was discussed and proposed as a powerful topic for a future research-action on the causes of their current health problems. For example, the great majority have diabetes problems, it would be interesting to make an individual and collective analysis of the causes of diabetes, and if this is reduced to a genetic factor, or if it is also related to the issue of care in adult life and the possibilities of self-care in people with precarious socioeconomic conditions (such as the older adults).

29Work is proposed as a category of analysis because it was present in the sessions as a constitutive element for the older adults’ identity in the ILPI. From a Marxist perspective, work is the premise of all human history; it is an economic-anthropological category. Marx affirms that work is the direct activity of the human being on nature, and it is in the product of work where the energy of the human being is objectified. This objectification is given by the recognition of labor and the value of the product by others. Work allows the creation of the symbolic world; this symbolic world is modified according to the time, however, the products generated by work are going to mean in the subjectivation of the person, as a construction of identity and otherness (VÁZQUEZ, 1983).

Received: February 13, 2020; Accepted: August 27, 2020

texto em

texto em