Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 03-Mayo-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469825012

PAPER

REPERTORY OF ACTIONS AND EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCES: INTELLECTUALS AND PROJECTS IN DISPUTE FOR EDUCATIONAL MODERNITY (BRAZIL, 1920S)

1Instituto Federal Catarinense(IFC). Rio do Sul, SC, Brasil. solange.hoeller@ifc.edu.br

2Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, SC, Brasil. <m.daros@ufsc.br>

This text, in the field of educational history, focuses on intellectual and cultural history to understand five educational conferences held in Brazil in the 1920s - the Interstate Conference on Primary Education (Rio de Janeiro, 1921); the Congress of Primary and Normal [Teacher] Education (Paraná, 1926); the First Congress of Primary Instruction (Minas Gerais, 1927); the First State Conference of Primary Education (Santa Catarina, 1927); and the First National Education Conference, which was promoted by the Brazilian Association of Education (ABE) (Curitiba, 1927). The conferences are considered part of a repertoire shared by five intellectuals: Orestes de Oliveira Guimarães, Antonio de Sampaio Dória, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa, Antonio de Arruda Carneiro Leão, Francisco Luís da Silva Campos, and Manoel Bergström Lourenço Filho, who are considered representatives of projects in dispute for educational modernity, highlighting the expansion, gratuity, and mandatory features of primary education. The research question is: how can we consider these conferences as part of a repertoire that mobilized intellectuals in defense and dispute of concepts and projects, in an effort to establish the meanings that would guide educational modernity in Brazil in the 1920s? The theoretical methodological approach and analyses involve the concepts of modern and modernity, repertoire, intellectuals, and representation. Reaching educational modernity in Brazil in the period required articulations and actions which, in theory, would guarantee reaching certain goals, such as the expansion of a primary compulsory free education.

Keywords: Educational conferences; educational modernity; primary education

Este texto constitui uma abordagem na área da História da Educação, tendo como fio condutor a história intelectual e cultural, procurando compreender cinco conferências educacionais ocorridas no Brasil nos anos de 1920: Conferência Interestadual do Ensino Primário (Rio de Janeiro, 1921); Congresso de Ensino Primário e Normal (Paraná, 1926); Primeiro Congresso de Instrução Primária (Minas Gerais, 1927); Primeira Conferência Estadual do Ensino Primário (Santa Catarina, 1927); Primeira Conferência Nacional de Educação, promovida por intermédio da ABE (Curitiba, 1927). A proposta considera as conferências educacionais como integrantes de um repertório compartilhado por seis intelectuais: Orestes de Oliveira Guimarães, Antonio de Sampaio Dória, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa, Antonio de Arruda Carneiro Leão, Francisco Luís da Silva Campos e Manoel Bergström Lourenço Filho, compreendidos como representantes de projetos em disputa pela modernidade educacional, com destaque para a expansão, gratuidade e obrigatoriedade do ensino primário. Apresenta-se a seguinte questão-problema: como pensar as conferências educacionais como integrantes de um repertório que mobilizou sujeitos - intelectuais - em defesa e disputa de concepções e projetos, no intento de estabelecer em que sentidos e significados a modernidade educacional deveria estar assentada no Brasil dos anos de 1920? O percurso teórico-metodológico e as análises realizadas circundam os conceitos de moderno/modernidade, repertório, intelectuais e representação. Atingir a modernidade educacional, em relação ao Brasil, no período indicado, exigiu articulações e ações que, em tese, garantiriam o pretendido, dentre elas estavam os aspectos da expansão, gratuidade e obrigatoriedade do ensino primário.

Palavras-chave: Conferências educacionais; modernidade educacional; ensino primário

El hilo conductor de este texto es la historia intelectual y cultural de la educación. Analiza cinco conferencias educacionales que ocurrieron en Brasil en la década de 1920: la Conferencia Interestatal de Enseñanza Primaria (Río de Janeiro, 1921); el Congreso de Enseñanza Primaria y Normal (Paraná, 1926); el Primer Congreso de Instrucción Primária (Minas Gerais, 1927); la Primera Conferencia Estatal de Enseñanza Primaria (Santa Catarina, 1927), y la Primera Conferencia Nacional de Educación, promovida por la ABE (Curitiba, 1927). Ellas forman parte de un repertorio compartido por seis intelectuales: Orestes de Oliveira Guimarães, Antonio de Sampaio Dória, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa, Antonio de Arruda Carneiro Leão, Francisco Luís da Silva Campos y Manoel Bergström Lourenço Filho. Ellos son representantes de proyectos en la disputa por la modernidad educacional, donde se destacan la expansión, gratuidad y obligatoriedad de la enseñanza primaria. Se plantea la siguiente cuestión: ¿Cómo pensar dichas conferencias como integrantes de un repertorio que movilizó intelectuales en la defensa y disputa entre concepciones y proyectos para establecer los sentidos y significados sobre los cuales debería basarse la modernidad educacional en el Brasil de los años 1920? La trayectoria teórica y metodológica y los análisis realizados giran alrededor a los conceptos de moderno/modernidad, repertorio, intelectuales y representación. Alcanzar la modernidad educacional, en relación a Brasil, en el período en cuestión exigió acciones y articulaciones que, en tesis, garantizarían lo pretendido. Entre ellas, los aspectos de la expansión, gratuidad y obligatoriedad de la enseñanza primaria.

Palabras clave: Conferencias educacionales; modernidad educacional; enseñanza primaria

INTRODUCTION

An investigation from the perspective of the history of education into projects in dispute for educational modernity is presented here with focus on five educational conferences, which took place in Brazil in the 1920s: Interstate Conference on Primary Education (Rio de Janeiro, 1921); Congress of Primary and Normal Education (Paraná, 1926); First Congress of Primary Education (Minas Gerais, 1927); First State Conference on Primary Education (Santa Catarina, 1927); First National Conference on Education, promoted through ABE (Curitiba, 1927). Six intellectuals who participated of the events are highlighted: Orestes de Oliveira Guimarães, Antonio de Sampaio Dória, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa, Antonio de Arruda Carneiro Leão, Francisco Luís da Silva Campos and Manoel Bergström Lourenço Filho.

In order to take educational conferences as a possibility to investigate projects for Brazil, which marked the education required for the nation, the concepts of modern/modernity, repertoire, intellectuals and representation flowed into the theoretical-methodological path followed.

The central purpose of this study is to investigate aspects and elements that intertwine in to think about the educational conferences (CIEP-RJ; CEPN-PR; ICIP-MG; ICEEP-SC; ICNE-ABE) as members of a repertoire that mobilized subjects - intellectuals - in defense and dispute of conceptions and educational projects in an attempt to establish on which senses and meanings the educational modernity should be based. In this discussion, expansion, gratuity and compulsory schooling for primary education will be presented as possibilities of analysis for the understanding of educational modernity in 1920s’ Brazil.

The term educational conferences, used in this text, includes both what is identified in the sources as “conference” and what brings the nomenclature of “congress”; both with the adjective “primary education” and “primary or normal education” or “education”.

Le Goff (1990; 1997, p.2) addresses issues related to the concepts of modern, modernity, modernization and modernism. Regarding what may correspond to modern, he highlights the historical and polysemic character of the ancient/modern pair, informing that this pair was developed in an equivocal and complex context. He states that “[...] each of the terms and corresponding concepts was not always opposed to each other: 'old' can be replaced by 'traditional' and 'modern', by 'recent' or 'new' [... ]” and also “[...] because either can be accompanied by laudatory, pejorative or neutral connotations ”.

For the author, this pair - ancient/modern - and its historical and dialectical game are generated between what is modern, where the awareness of modernity is born from the sense of rupture with the past. Old still shifts to other comparatives: modernity, modernization, modernism (LE GOFF, 1990; 1997).

In 1920sz Brazil, the ideals of modernity/modernity were discussed at the same time that the country sought to match up with new modernization techniques in different sectors of society, whereas in other areas a modernist movement was discussed. It is possible to assume that what constitutes the old/modern pair - in the 1920s' Brazil - implies embracing the meanings of what it itself represented the modern (as consciousness of modernity), modernization (as modern techniques that responded to the needs of the historical moment), modernism (the transformations suggested and carried out in the cultural field, especially in the field of arts).

The Conferences - composition and proposition - can be proposed as elements that comprised the modern/modernity in the 1920s, since, also with them and through them, the achieving of educational renewal was intended. Such spaces were also made concrete by discussions, debates, clashes between subjects who explained their ideas, conceptions and projects that aimed at the new, the progress, surpassing the limits of what was old or traditional, in short, reaching educational modernity.

As representation of modernity, the new and the progress, each of the educational conferences was loudly announced to the initiatives that proposed it, marking the event as a symbol of what it was intended to achieve for the nation, through the education and culture of Brazilian people. The idea of representation, approached here, benefits from the perspective of Chartier (1990; 1991; 1995; 2001; 2004), who confirms that “[...] all history, whether it is economic, social or religious, requires study representation systems and the actors they generate ”(CHARTIER, 2004, p. 19). Representation as “[...] intellectual schemes, which create the figures from which the present can acquire meaning, the other can become intelligible and the space can be deciphered” (CHARTIER, 1990, p. 17).

Of the five occurrences taken in this analysis, three different initiatives are observed in this regard: Federal government (CIEP-RJ) actions; three proposals (CEPN-PR, ICIP-MG, ICEEP-SC) by the state governments of Paraná, Minas Gerais and Santa Catarina, also considering that each one presents its singularities; and another, (ICNE-ABE) by ABE’s initiative.

Issues concerning childhood, renewing principles for education, proximity of treated topics and the same organizer or the same initiative for any of the events are also recognized in dialogue with works related to educational conferences. The temporal proximity of these events is justified by the context of the 1920s and by the fact that these elements can bring conferences closer together in terms of content and form in a certain proportion.

However, the discussion presented in this text is not established by the initiative of gathering events and opting for a larger universe of conferences, in relation to other existing works. We propose that the educational conferences taken can be analyzed by their intersection in the context of the 1920s, placing them, a priori, in a repertoire that was articulated in an attempt to consolidate proposals or projects for educational modernity, which would be also attuned to the modernity intended for the nation.

Therefore, educational conferences may be thought of as a whole, even if they started from different initiatives, were organized by the same subjects or by different subjects, presented some specific themes or of a somewhat similar character, occurred in common or different geographical areas, among other aspects.

It is possible to take educational conferences as a whole, as it is permissible to think of a repertoire of which they were part and which allowed to raise their occurrences and situate them in the context of the 1920s. Bringing together and analyzing these conferences allow us to perceive the representation, strength and projection that they achieved or that they intended to achieve and, as singular events in some aspects, they were not isolated or independent from other occurrences or actions in the approached repertoire. Similarly, the subjects who participated in these events were articulated with a context beyond the educational conferences, which include other forms of representation, participation and actions in the broader political and social spaces, as we seek to demonstrate through the involvement of the highlighted intellectuals with the movement for educational reforms in Brazil.

Tilly proposed the concept of repertoire from the 1970s, initially characterizing it as a repertoire of collective actions based on the theory of political mobilization, rejecting economic, deterministic and psychosocial explanations of collective action.

In the 1970s and 1980s, repertoire is understood as "patterns of action" under the ideia that there is "a familiar repertoire of collective actions that are available to ordinary people" in a given historical period. But it was up to question: "Is repertoire common to the entire era shared by all, or relative to actors in particular? (...). How do members of social life know, handle, and transform repertoires?" (TILLY apud ALONSO, 2012, p. 23).

In the text Contentions repertoires in Great Britain, 1758-1835, Tilly (1995, p. 27) reframed the expression as confrontation repertoire, while seeking to answer the questions mentioned previously: "Like their theatrical counterparts, collective action repertoire does not mean individual performances, but means of interaction between peers or larger sets of actors. The company, not an individual, maintains a repertoire."

Tilly, McAdam and Tarrow (2009, p. 24), with a refinement of Tilly's early ideas from the 1970s, argue that repertoires "are not simply the property of moving actors; they are an expression of the historical and current interaction between them and their opponents."

The repertoire of the 1920s, in Brazil, was understood by some elements or actions that are articulated to the subjects - intellectuals - highlighted: educational conferences; educational reforms; occupation of positions/functions in the field of Education and sphere of public administration; dissemination of ideas through printing or discourses (theses or discourses published in educational conferences, articles in magazines or press).

Orestes Guimarães, Sampaio Dória, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa, Carneiro Leão, Francisco Campos and Lourenço Filho are considered actors in this repertoire and, due to the resonance of their actions, they may be acknowledged as intellectuals who claimed educational modernity, proposing projects aligned with the ideals intended by the nation.

The concept of intellectual, coined from the propositions of Sirinelli (1986; 1992; 1998; 2003), may be defined by a variable geometry based on invariants, which implies two meanings that are not always necessarily unrelated. One meaning puts the intellectual in a broad and sociocultural conception that "[...] includes the 'creators' and cultural 'mediators' and "[...] both the journalist and the writer, the secondary teacher and the scholar " and also "[...] a part of the potential students, creators or 'mediators', as well as other categories of culture 'recipients'". The second definition of a narrower political nature is based on the idea of intellectual engagement in the city life (SIRINELLI, 2003, p. 242, 1986).

Dismissing analyses of the history of ideas, based on the internal logic of thought systems, Sirinelli (1986, p. 98) quoted Jacques Julliard (1984), recalling the obvidaity: "ideas do not walk naked on the street" (JULLIARD apud SIRINELLI, 1986, p. 98). He opposed biographical works of individual trajectories which did not consider the historical context of biographies such as affinities, approaches, choices, affiliations and other aspects of daily life, marked by sensitivities, which allow us to understand "how ideas come to intellectuals" (SIRINELLI, 2003, p. 256).

Sirinelli (1986, p. 102) states that it is possible to reconstruct itineraries, making a comparative study of the paths taken by intellectuals from a "common matrix" that can be institutional (attending the same educational institution), politics (affiliation to a political party or adhering to ideologies that lead to some common actions) or another matrix that promotes approaches or allows us to perceive aspects of the itineraries of individuals inserted in social and collective life.

REPERTOIRE, INTELLECTUALS AND EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCES: CULTURAL, INTELLECTUAL AND POLITICAL AMBIENCE

The understanding of intellectuals in the context of the 1920s seeks their arguments regarding the performance of the subjects - Orestes de Oliveira Guimarães, Antonio de Sampaio Dória, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa, Antonio de Arruda Carneiro Leão, Francisco Luís da Silva Campos and Manoel Bergström Lourenço Filho - before the possibility of interference in broader social spaces and transformations required by the culture path, having education and primary school as one of its purposes.

These protagonists are seen as those who present a trajectory of school education, professional performance and linkages that allowed them to act on certain fronts in which culture and education were understood as elements for the intended reformulations, such as investiments in educational conferences. However, the actions of these intellectuals were not limited to educational conferences. Therefore, educational conferences represent one of the places and actions - inserted in a broader repertoire - that were shared by them.

The discussion of shared actions and places does not implie that all subjects lived together or participated simultaneously or jointly in all the occurrences exposed, although, in certain cases, this is corresponding. Some intellectuals were in or attended the same conferences, actions or occupied common places.

Shared experiences cannot be taken as a homogeneous block, as it is seen in the following charts. Rather, they must be perceived by their approaches and singularities that converged so that intellectuals were involved with educational conferences and inserted in a repertoire that converged to a project of educational modernity for Brazil.

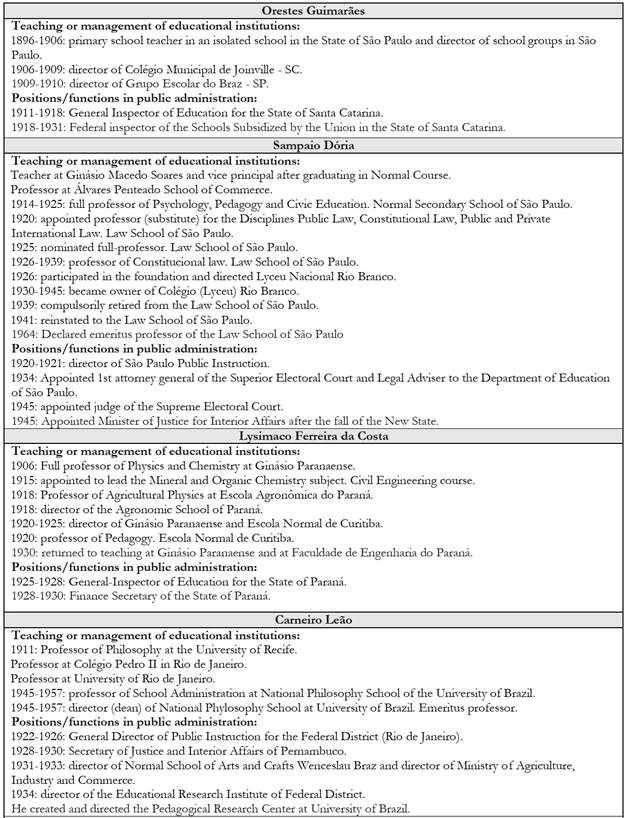

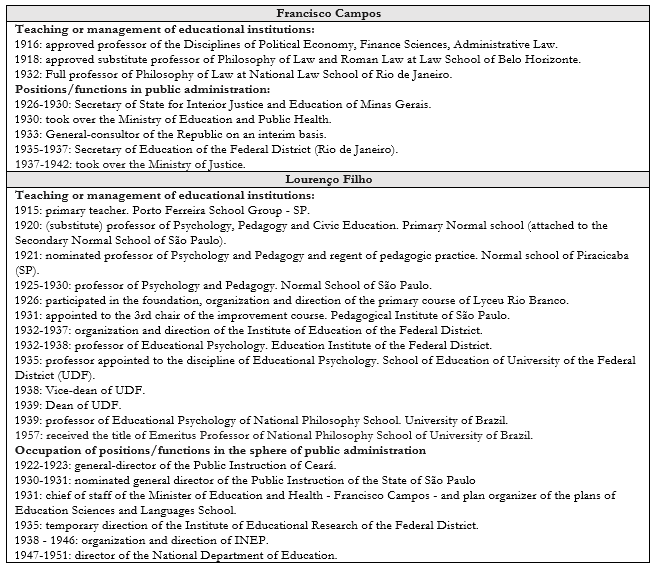

Source: Table elaborated for this research from sources and references cited at the end of this text.

Chart 1 Biographical data of intellectuals: city, state and year of birth/death and formation.

Of the six intellectuals, not all of them enjoyed favorable economic resources, but what brings them closer is the cultural value preserved by the family environment (of origin) that, with greater or lesser economic condition, allowed education to have a privileged place.

Not all are part of the so-called "generation born with the Republic", in the sense of being born after the year 1889, however, the proximity between them can be marked by the identification that all had part or all of their graduation and mainly professional performance in the context of republican Brazil.

We highlight the approximation of these intellectuals by common experiences, outlined by the social, cultural and political ambience of the 1920s, which placed them in a condition to participate and propose in the spaces of educational conferences, also perceiving other elements that made up the repertoire of which they were part.

Chart 2 Biographical data of intellectuals: teaching, management in educational institutions, public positions.

Source: Table elaborated for this research from sources and references cited at the end of this text.

Chart 2 continuation

The biographical notes suggest they were intellectuals who went through the 1910s and 1920s - some beyond these periods - working in the field of education, at regional level, in their states, or at national level, and who had articulations with the political, educational and cultural areas, some of them inside and outside the country.

However, it is also worth mentioning that all were involved, in the 1920s, with the repertoire delimited by the elements signposted here: educational conferences, educational reforms, occupation of positions/functions in the field of Education and the sphere of public administration and dissemination of ideas through printing or discourses.

Still as common traces of their trajectories, it is perceived, reserved the particularities of each case, that these subjects who were ahead or participated in educational conferences were the same as those who, along with others: held positions in the sphere of the federal public administration or the states; participated in the journalistic press or as authors; draft opinions on political or education-related issues; organized collections of didactic works or appeared in the literary and cultural circuit of the country, publishing their ideas, giving speeches and conferences; they maintained articulation with the government of their states, with the federal government, with civil entities or organizations - associations, leagues, academies, etc. - of national performance or projection.

It is noteworthy they accumulated or went through activities in different instances: some were politicians (with party affiliation), jurists, poets, writers and some worked in newspapers.

All were teachers and performed public and administrative functions related to education - they were inspectors or directors of public education in Brazilian states or in the federal district - they were involved in reformist movements or movements that intended educational renewal at state or federal level and participated in educational conferences, composing what is indicated here as members of a repertoire.

In this perspective, their proposals within the conferences did not start from isolated positioning, but were marked by their linkages, connections and displacements built within a repertoire that had several actions, elements and subjects.

As for the five educational conferences investigated and the highlighted intellectuals, Orestes Guimarães had greater participation, in terms of presence. His performance at CIEP-RJ was intense. As first secretary, he was at the head of the Conference by decision of the federal government. Guimarães participated in the preparatory committee and the nine sessions of preparation of the event, in all fourteen ordinary sessions and in the closing sessions (BRASIL, 1922). He was ahead of the bylaws' drafting and the organization of ICEEP-SC and part of the organizing committee of the event in 1927. He was 1st secretary (in the 1st preparatory session) and proposed a thesis on manual labor. As delegate, Guimarães represented the state of Santa Catarina in ICNE-ABE and was president of 2nd commission of responsible analysis for the proposals concercning primary education in the same year, presenting the same thesis that he had presented in ICEEP-SC.

Sampaio Dória attended to CIEP-RJ as representative of the Nationalist League of São Paulo and since he was not part of the event preparation committee, he was only in the usual sessions. Dória was the participant who most gave speeches (four) and composed the same analysis committee of Orestes Guimarães, presenting memory4 and countermemory5, which can be understood from complaints made, as it will be seen. He also represented Lourenço Filho through the General Plan of Pedagogical Practice, which was held at Normal School of Piracicaba6, of which Lourenço Filho was a mentor and teacher.

Carneiro Leão was part, along with Orestes Guimarães, of the organizing committee of CIEP-RJ. Appointed as representative of the Federal Government along with the standing committees, he was present in 22 of the 25 sessions that took place. Carneiro Leão presented a thesis on the organization and purposes of the National Education Council and was the rapporteur of the 5th review committee in charge of evaluating this theme.

Like Carneiro Leão, Francisco Campos' involvement took place only in a conference. At ICIP-MG, he was ahead of the preparatory and organizing committee; he was the president of the event and delivered an opening speech.

Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa has his name linked to three conferences. He was the organizer of CEPN-PR and ICNE-ABE and gave speeches in the opening sessions of these events. For CEPN-PR, Lysimaco was appointed as vice president, but took over the position of president almost during the entire event - replacing Caetano Munhoz da Rocha, governor of the state, and spoke at the closing session. At ICNE-ABE, he was an organizer and part of the 3rd committee, with the task of evaluating "general themes". In the section marked with the title of guests in the Internal Rules of ICEEP-SC (SANTA CATHARINA, 1927a), his name appeared as the first on the list of especially invited people, but he did not attend. However, he sent messages of congratulations and appointed a representative.

Lourenço Filho's participation in two conferences is acknowledged. He did not attend to CIEP-RJ, but his ideas circulated through the memory presented by Sampaio Dória. He shared, in person, the ICNE-ABE space with Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa and Orestes Guimarães.

Through the7 references mentioned, the intellectuals are considered actors of actions that make up the repertoire, situated as participants of a generation that has part of their school education and professional performance in the republican period, whose constructed and experienced itineraries put them in a position to think, represent or propose in conferences. They are also recognized by the political engagement in the life of society, by placing themselves as spokespersons of the people, denouncing the problems and proposing solutions or possibilities of intervention in the educational area, as well as in the broader social space.

EDUCATIONAL MODERNITY: EXPANSION, GRATUITY AND OBLIGATORINESS FOR PRIMARY EDUCATION

Dealing with the conferences' mobilizers implies evaluating them for their wider character and understanding that their manifestations were directed, a priori, to deal with questions concerning the nation through culture and education - considering the required renovating ideals - within the context of the 1920s, in the perspective of taking Brazil to the routes of modernity.

Taking into account the relevance of the treatment to primary education as one of the preponderant aspects to accomplish projects for the nation, the expansion, gratuitousness and obligatoriness of this education level are presented as a possibility to guarantee the claimed nation identity and educational modernity.

Expansion, gratuitousness and obligatoriness of the primary education should be among the highlighted points of the agenda, considering the overcoming of the pointed delays aspects of the new and current, in short, representatives of the educational modernity.

Without enough schools - expansion -, without the gratuitousness of the same and without the obligatoriness of frequency, how to execute projects for the modernity of the nation through education? How to instruct, in the sense of literacy, or how to educate in the perspective of modeling new conducts of the good and useful citizen to the nation, based on Brazilian culture and national elements, without schools and without imposing children to attend them? The elaboration of proposals to the educational area would be of no use if there were not enough schools in sufficient proportion or if, there were, but the children did not attend to them.

In these arguments, directly or indirectly, the educational conferences brought to light such aspects, as it was the case with the thesis “Diffusion of primary education. Formula for the Union to help spread this teaching; relative obligatoriness of primary education; its conditions”, analyzed by the 1st CIEP-RJ commission.

The most striking criticisms were those from Sampaio Dória. He started by complaining about the lack of appreciation of his memory and, afterwards, proceeded with the criticism, point by point, of the presented conclusions. He asked why the Union should only be in charge of the subsidy and argued: “does the direct installation of federal schools within the conditions indicated by us in the 'Memory' that we present attack the greatness of the Nation?” (BRASIL, 1922, p. 99-100).

Others also commented - among them Carneiro Leão and Orestes Guimarães - on the conclusions issued, however, they did so in a more lenient way and some even with praise for the work done. Even so, there were several amendments that, at times, found participants consonant in some points and disagreeing in others.

Sampaio Dória presented an amendment (no. 4) opposing some points presented by the Organizing Committee of CIEP-RJ, proposing it to be attended in the following terms: “School attendance is free and mandatory for children from seven to 14 years old [...] ” and the following children were exempted from this obligation:

a) children who live beyond two kilometers from the school, or if there is no vacancy in existing schools up to this distance; b) those incapable or attacked by contagious or repulsive disease; c) indigent people, as long as the Government does not provide them with essential clothing for decency and hygiene; d) those who receive, at home, or in private schools, instruction identical to that given in public primary schools (BRASIL, 1922, p. 107).

Amendment no. 4, by Sampaio Dória, was put to vote and the author was opposed to the positions that deservedly considered what he requested, but stated that the country could not, at that moment, decree such a measure with the required amplitude. He countered, saying the reasons given by the commission did not seem acceptable. The amendment was put to vote and was rejected, “against the votes of Misters Sampaio Dória, Orestes Guimarães, Americo Motta, D. Esther de Mello and D. Maria Reis Santos” (BRASIL, 1922, p. 120).

While, in the case above, Sampaio Dória and Orestes Guimarães were in agreement, in the vote on the amendment of the representative of the state of São Paulo, Freitas Valle and these were on opposite sides regarding the percentage of Union subsidy for the expansion of primary education. Sampaio Dória was in the favor group of the amendment; Orestes Guimarães, along with Carneiro Leão and others, voted against it. The amendment was approved by twelve votes to ten (BRASIL, 1922, p. 121).

As for the amendment proposed by Orestes Guimarães, it seems that it was approved, however, Sampaio Dória declared that he had voted in favor, but with restrictions regarding the inspection of teaching (BRASIL, 1922, p. 118). Sampaio Dória, resuming the matter at the ninth ordinary session, claimed that “After verifying that my proposal had not been examined by the 1st committee [...], I reiterated my memory as an amendment in full session under the same terms: direct provision of primary schools with inspection and supervision under the responsibility of the States,”. It was also possible, according to Sampaio Dória, that “the Conference reconsider the mistake of wanting to institute a double inspection: federal and state. May their hands not hurt ”(BRASIL, 1922, p. 202).

Sampaio Dória declared at the sixth ordinary session of the CIEP-RJ that “if we can judge and foresee the measures we suggest in reform or amendment to the opinions of the commissions through voting on Saturday, those will be rejected without hesitation. The commission's rapporteur will oppose what has not come out of himself ", but, even so, he would continue to" propose what is necessary to the opinions of the commissions in faithful reiteration to the ideas of our (his) memory "(BRASIL, 1922, p 145).

The final opinion of the 1st commission - which can be read as one of the educational projects in dispute for Brazilian primary education, in conjunction with the commitment delegated to the Union - was voted and approved in the seventh ordinary session, deliberating, with minor wording adjustments, on compulsory education:

1st The Interstate Primary Education Conference recognizes the competence of the National Congress to decree the mandatory education; 2nd The current country situation does not include the enactment of this measure in an absolute character; 3rd Participants or companies that have factory or industrial establishments that employ minors in their service and private individuals that employ them in domestic services must teach the first letters; 5th those who violate what is provided by the previous conclusion will be punished according to the law determination (BRASIL, 1922, p. 153).

The approved opinion of the first CIEP-RJ thesis maintained, in great proportion, what the 1st commission had exposed in its first version. We may also notice the conciliatory tone maintained, which did not establish the mandatory nature of primary education in an absolute way, allowing to consider the observations made about the budgetary difficulties or the geographic conditions of the country. In the same way, the age range circumscribed by the mandatory nature and the duration of the primary course were not defined.

However, the final approved opinion was not enough to calm the spirits of those present at CIEP-RJ. Sampaio Dória spoke again, claiming that his “so maligned reform” (1920) not only did not mutilate, but had integrated the São Paulo school system. The criticisms, however, have been fixed in its

only vulnerable point, its poor Achilles heel is this reduction of free primary education and the requirement to attend two years only. However, do not confuse the reduction of primary education with the reduction of gratuity. Due to the reform of education in São Paulo, primary education raised there from 6 to 7 years in 10 schools; gratuity has been reduced to two years. Moreover, which is almost everything, that reform, of which I am the main author, made a dizzying advance towards the ideal. Yes, because S. Paulo was the model of public education among us, now more than ever, except for the reduction of gratuity, it is there that Brazil will have to seek the best standard of primary and normal education. If we venture on different paths, we will do poorly done work (BRASIL, 1922, p. 146)

Situated in the same repertoire, educational reforms were evoked within the conferences and intertwined arguments related to the aspects of school expansion, gratuity and mandatory education, also generating tension and debates.

Henrique da Silva Fontes - representative of Santa Catarina at CIEP-RJ - mirrored the São Paulo reform with the Santa Catarina context, rebutting Sampaio Dória's statements which said that the São Paulo reform was an innovation. Regarding the seven-year primary course, he stated that, in Santa Catarina, this had already been proposed since 1911 by the reform inspired and carried out by Orestes Guimarães. He went on to praise Guimarães and his condition, while Sampaio Dória interrupted the speech, refuting that he had not mentioned “innovation”, but that the state had raised primary education to seven years; he had also not referred to Santa Catarina, nor to Henrique da Silva Fontes, questioning: “When and where did I refer to you? I didn't make any personal references ”(BRASIL, 1922, p. 155).

The asides demanded that Henrique da Silva Fontes addressed the highest authority of CIEP-RJ, noting: “Mr. President, when at the last session, others and I wished to give asides to the speaker, you asked us not to disturb him. I don't think there are double standards here. I ask for the application of the same measure”. After having his request granted, he proceeded by citing that Sampaio Dória had mentioned that he was a defender of three or four year schools run by a single teacher, which did not represent his ideas or the reality of Santa Catarina. Again, Sampaio Dória interspersed: “Once again, I did not make any personal references” (BRASIL, 1922, p. 156).

Even in the face of heated spirits, Sampaio Dória continued to intervene, giving his opinion and imposing his presence. “It is said at this Conference that I am a supporter of reduced primary education for two years and that is it. I never preached such absurdity and heresy. On the contrary, whenever I have had an opportunity, I have expressed myself in the opposite sense ”(BRASIL, 1922, p. 182). He maintained that he agreed with the other participants that the primary school should be aimed at children aged seven to fourteen years old. However, this issue was still subject to further criticism by Carneiro Leão and Orestes Guimarães, which may indicate that the issue did not end in a friendly atmosphere.

Sampaio Dória's performance in the referred reform was criticized by Carneiro Leão when he was at the head of public instruction in the Federal District (1922-1926). The reformist actions of Carneiro Leão, in Rio de Janeiro, were compiled by him in 1926, under the title “Teaching in the capital of the country” and the criticisms are registered::

Thus, any campaign that seeks to fix the primary course in Brazil in 2, 3 or 4 years is unfounded and even dangerous. São Paulo itself, which, for financial reasons, decided to solve the problem by reducing the free internship, went back and established primary education in 6 years, including 2 years of the complementary course. (LEÃO apud SILVA, 2006, p. 75).

Carneiro Leão explained, in the Project (no. 238) of his reform in the Federal District, that primary education would be mandatory and would last for four years in the fundamental stage and two years in the complementary stage, as long as there were subsidized public or private schools able to receive the entire school population from seven to fourteen years old, within each school perimeter.

If Carneiro Leão criticized the Reform of Sampaio Dória in São Paulo, Silva (2006) notes that the reality in Santa Catarina was a factor that deserved praiseworthy comments, noting that the organization of teaching in Santa Catarina, among other favorable characteristics, was composed of “[. ..] kindergarten, elementary school and complementary course of three years, providing a popular education with period of nine full years ”(LEÃO apud SILVA, 2006, p. 76).

When questioning the Brazilian reality, Raul Gomes, in a thesis at ICNE-ABE, questioned the federal government's responsibilities and the states' responsibilities regarding the expansion and mandatory nature of primary education. The proponent presented a broad statistical report, both in a geographic perspective - of the different Brazilian states - as well as in history, to demonstrate that the mandatory schooling appeared as a “dead letter” in the relevant legislation, because, despite being foreseen years ago, it had not found a “systematic and lasting execution in any state of Brazil” until that oment and questioned:

[...] if the tiny State of Santa Catarina, in an admirable test of the comprehension and scope of the sacrifices employed in popular education, invested 20% of its income in education in 1921, why wouldn’t Brazil of 1934, whose degree of evolution and achieved progress [...]reserve, for the stupendous and redemptive task of incorporating the entire six-year class, the tiniest and simple percentage of 8% on the sum of the general revenue? (ASSOCIAÇÃO ..., 1927, p. 572; 583).

However, due to the recognition given by some - Carneiro Leão and Raul Gomes among them- to the Santa Catarina context, which contained in its legislation the provision for mandatory schooling and mentions to high investments in the educational area, this cannot be interpreted as if Santa Catarina had addressed these issues. It is noteworthy that the reality present in the Santa Catarina context, in the 1920s, still demanded innumerable solutions to the problems of public education. The reality was little disapointing in several aspects, including the lack of regular attendance by students to classes, which undermined the question of obligatoriness (HOELLER, 2009).

ICEEP-SC participants, like Orestes Guimarães, signed a petition, highlighting the Decree of December 4, 1926 and emphasizing the need for the state to “strictly comply with the precepts of the alluded decree regarding attendance at schools for children under 14 years old”. Following the petition made, Orestes Guimarães stated that he approved the mandatory measure and regretted that the “decrease in enrollment in the 3rd and 4th years of public establishments is (which was) due to the use of minor’s labor”. He extended his comments, condemning the São Paulo reform promoted by Sampaio Dória, in 1920, which reduced primary education to two years, in that state, in 1920 (SANTA CATHARINA, 1927b, p. 105-106 emphasis added).

The Public Instruction Regulation - derived from the actions taken by Lourenço Filho in the educational reform in Ceará - deliberated on issues similar, in some points, to other reforms concerning nomenclatures or certain aspects. However, despite the similarities in subjects and nomenclatures, Lourenço Filho's understanding of public education in Ceará, represented in the Regulation, differs from that of São Paulo, proposed by Sampaio Dória, and is close to the defenses of Carneiro Leão and Orestes Guimarães. Regarding the free and mandatory nature of primary education, it was provided for in “Art. 36 - Illiterate children from 7 to 12 years old are obliged to attend school free of charge ”(CEARÁ, 1922). As for exempt cases and penalties, Lourenço Filho considered it very similar to Sampaio Dória’s reform.

Moreno (2003, p. 56) points out that the obligation of primary education was on the agenda for discussion of the scenario of Paraná throughout the 1920s and, among the reformers, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa was the only one who oscillated favorably on compulsory education, so much that one of the official theses of CEPN-PR - an event organized by Lysimaco - was established in terms that questioned: is there a need to make elementary education strictly compulsory in Paraná?

Tensions were also revealed at CEPN-PR around the (im)possibilities of having compulsory school in Paraná contemplated. The thesis of Segismundo Antunes Netto - lens of the Normal School and School Inspector of Ponta Grossa - defended the compulsory education in the opinion of the analysis commission, recognizing the need to spread “the light of the alphabet, making it compulsory” in Paraná (PARANÁ, 1926a ). However, the thesis provoked heated debates among those present, as recorded in the minutes of the event and the newspaper Estado do Paraná. The “thesis was reported by Professor N. Meira de Angelis. After the discussion ended, professor José Cardoso, director of the Jacarezinho school group, made a brilliant speech against the obligation”(ANGELIS, 1926, s. P.).

Despite the asides, this thesis and two others that dealt with the same theme were approved, as they argued that “compulsory education must necessarily be part of legislation and be embodied in the customs of countries that want to live in the fullness of life of civilization, progress and the greatness of humanity ”. However, it was argued that it was necessary to “first fix the walls and then put the roof on the gigantic building, so that we would not go through the embarrassment of seeing the collapse of the law of compulsory education later”, as it was still necessary to invest in expanding the number of schools, especially in rural areas, and in their technical equipment (PARANÁ, 1926a).

The Minas Gerais event - ICIP-MG - was designed in conjunction with the reform of public education in the State of Minas Gerais, authorized by the state government, in 1926, whose responsibility, as already highlighted, was under Francisco Campos, who called the event to think the reform that he implemented in 1927, after the event.

From the actions derived from the educational reform of 1927, promoted by Francisco Campos within the ICIP-MG, the expansion of schools to the state was proposed and the compulsory attendance in primary education was defined, according to the age group of seven to fourteen years old, extending up to sixteen years old for individuals who, at fourteen, were not qualified in primary school subjects, providing such measure, cases similar to those presented by the reforms of Orestes Guimarães (SC), Lourenço Filho (CE) and Carneiro Leão (PE), assigning similar penalties (MINAS GERAIS, 1926; 1927a; 1927b; 1927c).

The analyzed repertoire and the highlighted intellectuals, both the educational conferences and the educational reforms, as well as the defenses and arguments of the highlighted intellectuals in other circumstances, lead to consider the need to propose educational projects that collaborate with the desire for progress and modernity of the education and the Brazilian nation.

Such projects should include aspects that could guarantee education, contributing to the formation of citizens who were in line with what was desired. Educational modernity consisted of overcoming the existing condition, towards the future and progress, requiring sufficient schools to meet the demand; in addition to expanding the range of the population attending primary school - from seven to fourteen years old -; deciding for gratuity - at the expense of public authorities -; and compulsory attendance of the population of primary school age.

Intellectuals, as actors in the repertoire demarcated in the 1920s, did not shy away from discussions and debates involving such issues, since progress and modernity, without the scope for educational improvement, would not be possible. How to form conducts, through the primary school, without schools in sufficient proportion, without gratuity and reach to the entire population and without the compulsory attendance? Without the preservation of these elements, a project of educational modernity would be destined, a priori, to fail.

However, we do not intend to infer, with the statements made in this discussion, that the demands claimed have been fully met. However, the elements of expansion - both in the number of schools and in the age group to attend as well as the free and compulsory elementary education - for sure appeared on the 1920s’ debates’ agenda in Brazil, allowing to interpret certain aspects of the representation of projects for educational modernity.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

We may affirm that there is a tendency to hold events - congresses, commissions, conferences - in which subjects come together to articulate, defend, dispute concepts and formulate proposals, believing that they can respond to the needs in the local, regional and national educational scope.

Educational conferences, both in the 1920s and in other past decades, as in more current times, represented by CONAE movement (BRASIL, 2014; 2018), may be understood as public places for exhibition, explanation and discussion of educational projects that converge or, in certain cases, dispute different propositions.

The differences between the current historical moment and the occurrence of events in the 1920s being reserved, it is important to reflect on different historical realities about educational projects and proposals. This reflection can assist in the understanding of the Brazilian historical-educational process and comprehension of what was and what is in evidence in the field of Education and how it can be considered a project of nation in certain proportion, since educational conferences cannot be understood by an isolated perception of the larger context that represented or represents the Brazilian educational reality.

Specifically, regarding the events analyzed in this text, the climate between affirmation of proposals, confirmation of positions and the requirement to understand the pertinence or not of the ideas of the participants and the search for demarcation of places in the conferences can be attributed to all of them.

Sampaio Dória, at CIEP-RJ, was not only the one who did not escape the confrontations, but also the one who, on several occasions, caused such confrontations. We may suggest that he was the most combative participant in this event and, at the end of the day, of the others analyzed here. This does not mean that he was the one who most effectively imposed his proposals. His posture reflects his eloquent speaker profile, but it also reflects his condition in the educational and political scene of that moment, which was, in a way, weakened by his poorly understood reform - according to his statements - and his quick passage through the board of the public instruction of São Paulo.

The other two intellectuals - Orestes Guimarães and Carneiro Leão - present at CIEP-RJ, at that time enjoyed a more comfortable and prestigious position in the educational and political scene - exercised functions in the administrative sphere of the federal government - and during the conferences they had acted as organizers, thesis proponents and rapporteurs of analysis commissions of which they were members. Such positions dispensed, in certain cases, the need to request a prominent place in that event and put them more in tune with what was presented in the ordinary sessions, since their theses had already been previously discussed during the nine preparatory sessions, in which they were always present.

Bringing his memory to CIEP-RJ allowed Sampaio Dória not only to defend his educational project for Brazilian primary education and the commitment delegated to the Union, but also to justify and counter the criticism that he had received for his reform, making the conference a public space for the defense of his actions and for the explanation of the inability to understand them by those he called “rumormongers”. Thus, the memory was always mentioned, along with the aspects of the reform that had been promoted in São Paulo in the previous year.

As stated in the sources, the reforms of Orestes Guimarães (Santa Catarina - 1911/1913) and Sampaio Dória (São Paulo - 1920) were not preceded by educational conferences that justified them. However, they were taken to CIEP-RJ in an exalted manner, either by defenders of the purposes, in the case of the first, or by their own mentor, in the case of the second.

The educational reforms recalled demonstrate the articulation of the actions of intellectuals with the spaces of educational conferences, making it clear that both - reforms and conferences - participated in the repertoire of the 1920s, of which intellectuals were part. Furthermore, they helped to design educational projects for the country.

It is noteworthy that the principles of expansion, gratuity and obligatoriness of primary education could not be left out of the proposals of the 1920s, as they were principles that, in theory, would guarantee the effectiveness of projects for educational modernity and, by extension, for the modernity of the nation.

The free and compulsory primary school for the age group of seven to fourteen years old was seen as a privileged locus for the cultivation of national feelings, conscience and identity. At the same time, it should contemplate ideals of an education renewed by the new means and new ends of education, for the formation of the Brazilian and Republican citizens that Brazilian society demanded for that moment, according to the rhetoric of the period.

The reformist movement of the 1920s, of which intellectuals - Orestes Guimarães, Sampaio Dória, Lourenço Filho, Carneiro Leão, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa and Francisco Campos - were part, is representative of the issues related to the expansion, gratuity and obligatoriness of primary education, as well as the educational conferences were places of circulation of these ideas and make it clear that what was proposed by them added to the voices of other subjects at that time.

It can also be inferred that educational conferences, present in the repertoire of the 1920s in Brazil, represent possibilities for interpreting projects for the nation and for educational modernity through the theses debated and the subjects who claimed the changes required for that period, in articulation with other elements and actions of that repertoire.

REFERENCES

ALONSO, A. Repertório, segundo Charles Tilly: história de um conceito. Sociologia & Antropologia. v. 02, n. 03, p. 21-41, 2012. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, F. A. A obrigatoriedade da instrução pública na província do Ceará. In: VIDAL, D. G.; SÁ, E. F.; SILVA, V. L. G. (Orgs.). Obrigatoriedade escolar no Brasil. Cuiabá: EduFMT, 2013. p. 47-62. [ Links ]

ANGELIS, N. M. O professor pontagrosense homenageado O Estado do Paraná. Cutitiba, 24 dez. 1926. Curitiba. [ Links ]

ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE EDUCAÇÃO. I Conferência Nacional de Educação: Curitiba, 1927a. Publicação organizada por COSTA, M. J. F. F.; SHENA, D.; SCHMIDT, M. A. MEC. SEDIAE/INEP. IPARDES. Brasília, 1997. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e Cultura. Conferência Nacional de Educação, 2018 - orientações para as conferências municipais, intermunicipais, estaduais e distrital. Brasília-DF, março de2018. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://conae.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/doc_orientacoes_conferencias.pdf > .Acesso em: 27 abril 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Annaes da Conferência Interestadual de Ensino Primário. Rio de Janeiro: Emp. Industrial Editora “O Norte”, 1922. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e Cultura. Documento Referência - CONAE. Brasília, 2014. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://fne.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/documentoreferenciaconae2014versaofinal.pdf >. Acesso em:24 abril 2020. [ Links ]

CEARÁ. Regulamento da Instrução Pública do Estado. Ceará, 1922. In. VIEIRA, A. L.; FARIAS, I. M. S. (Orgs.). Documentos de política educacional no Ceará: Império e República. Colaboração: NOGUEIRA, D. L. et al. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, 2006. (Col. Documentos da Educação Brasileira), p. 153-159. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, R. A história cultural: entre práticas e representações. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand, 1990. [ Links ]

CHATIER, R. Cultura escrita, literatura e história. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2001. [ Links ]

CHATIER, R. O mundo como representação. Estudos Avançados, 5(11), p. 173-191, 1991. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.revistas.usp.br/eav/article/view/860 >. Acesso em: 18 julho 2020. [ Links ]

CHATIER, R. El mundo como representación: estúdios sobre historia cultural. 2. ed. Barcelona: Gedisa, 1995. [ Links ]

CHATIER, R. Leituras e leitores da França no Antigo Regime. São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 2004. [ Links ]

HOELLER, S. A. O. Escolarização da infância catarinense: a normatização do ensino público primário (1910-1935). 210 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2009. [ Links ]

HOELLER, S. A. O.; DAROS, M. D. Método de ensino para escola primária: discursos na Primeira Conferência Estadual do Ensino Primário (Santa Catarina, 1927). In: IXCONGRESSO LUSO-BRASILEIRO DE HISTÓRIA DA EDUCAÇÃO (COLUBHE): Rituais, Espaços & Patrimônios Escolares2012, Lisboa,. Anais... Lisboa: Instituto de Educação da Universidade de Lisboa, 2012. p. 1-10. [ Links ]

JULLIARD, J. Le facisme em France. Annales Economies, Sociétés, Civilisations, 39(4), p. 849-981, juillet-acoût, 1984. [ Links ]

LE GOFF, J. Antigo/moderno. In: Enciclopédia Einaudi, Lisboa, IN-CM, (reed.), vol.1. Memória-História, 1997. p. 370-392. [ Links ]

LE GOFF, J. História e memória (1924). Trad. Bernardo Leitão et al. Campinas: Editora da UNICAMP, 1990. [ Links ]

LOURENÇO FILHO, M. B. A formação de professores: da Escola Normal à Escola de Educação. (Org.) Ruy Lourenço Filho. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais, 2001. (Col. Lourenço Filho). [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Lei n. 926. Autoriza a reforma do Ensino Primário no Estado de Minas Gerais. Palácio da Presidência do Estado de Minas Gerais. Uberaba, 1926. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Regulamento do Ensino Primario. 15 de outubro de 1927. Aprovado pelo Decreto n. 7.970. Palácio da Presidência do Estado de Minas Gerais. Uberaba, 1927c. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Revista do Ensino. Orgam Official da Directoria da Instrucção. Ano III, n. 21, maio e junho. Belo Horizonte, 1927a. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS Revista do Ensino. Orgam Official da Directoria da Instrucção. Ano III, n. 22, agosto e setembro. Belo Horizonte, 1927b. [ Links ]

MORENO, J. C. Inventando a escola, inventando a Nação: discursos e práticas em torno da escolarização paranaense (1920-1928). 140 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. Universidade Federal do Paraná, Cutitiba, 2003. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Congresso de Ensino Primário e Normal (teses). Acervo: Memorial Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa. Curitiba, 1926a. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório da Secretaria Geral do Estado do Paraná apresentado ao Exmo. Dr. Caetano Munhoz da Rocha, Presidente do Estado, por Alcidez Munhoz, Secretário Geral do Estado, referente aos serviços do exercício financeiro de 1925-1926. Curityba: Livraria Mundial, França & Cia. Ltda, 1926b. [ Links ]

RIO DE JANEIRO. Projeto n. 238. Reforma da Instrução Pública do Distrito Federal. Distrito Federal (RJ), 1926. In. SILVA, J. A. P. Carneiro Leão e a proposta de organização da educação popular brasileira no início do século XX. 131 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Maringá: 2006. (Apêndice C). [ Links ]

SANTA CATHARINA. Annaes da 1ª Conferência Estadual do Ensino Primário. 31 de julho de1927. Florianópolis, Off. Graph. da Escola de Aprendizes de Artífices, 1927b. [ Links ]

SANTA CATHARINA. Regimento Interno da Conferência de Ensino Primário. Gabinete da Imprensa Official. Florianópolis, 1927a. [ Links ]

SILVA, J. A. P. Carneiro Leão e a proposta de organização da educação popular brasileira no início do século XX. 131 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação.Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Maringá, 2006. [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, J. F. As elites culturais. In: RIOUX, J. P.; SIRINELLI, J. (dirs.). Para uma história cultural. Traduzido por Ana Moura. Lisboa: Editorial Estampa, 1998. p. 349-363. [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, J. F. Histoire des droites em France. v. 2, Cultures, Paris: Gallimard, 1992, p. III-IV [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, J. F. Intellectuels et passions françaises: manifestes et petitions au XXe. siecle. (França): Fayard, 1990. [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, J. F. Le hasard ou la nécessité? Une histoire en chantier: l'histoire des intellectuels. In: Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire. n. 9, p. 97-108, janvier-mars, 1986. [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, J. F. Os intelectuais. In: RÉMOND, R. Por uma história cultural. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2003. p. 231-269. [ Links ]

SOUZA, G.; ANJOS, J. J. T. A criança, os ingênuos e o ensino obrigatório no Paraná. In. VIDAL, D. G.; SÁ, E. F.; SILVA, V. L. G. (Orgs.). Obrigatoriedade escolar no Brasil. Cuiabá: EduFMT , 2013. p. 189-208. [ Links ]

TILLY, C. Coerção, capital e Estados europeus. São Paulo: Edusp, 1996. (Col. Clássicos). [ Links ]

TILLY, C. Contentions repertoires in Great Britain, 1758-1834. Social Science History, 17: 2, Supplied by The British Library, 1993. p. 253-280. [ Links ]

TILLY, C. Getting together in Burgundy (1675-1975). CRSO Working Paper U128, Center for Research on Social Organization, Universidad de Michigam, maio, 1976. [ Links ]

TILLY, C. Itinerários em análise social. Tempo Social, São Paulo, v. 16, n. 2, p. 299-302, 2004. [ Links ]

TILLY, C. McADAM, D.; TARRROW, S. Para mapear o confronto político. Trad. Ana Maria Sallum. Lua Nova, São Paulo, n. 76, p. 11-48, 2009. [ Links ]

TILLY, C. Contentious repertoires in Great Britain, 1758-1834. In: Traugott, Mark (org.). Repertoires and cycles of collective action. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995, p. 15-42. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, A. L.; FARIAS, I. M. S. (Orgs.). Documentos de política educacional no Ceará: Império e República. Colaboração: NOGUEIRA, D. L. et al. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, 2006. (Col. Documentos da Educação Brasileira). [ Links ]

4Memory: the term is used to express the propositions of the participants of CIEP-RJ which originated from the six theses that were treated in this event.

5Countermemory: term coined by Sampaio Dória - recorded in the Anais - rebuts the comments made about what he presented in his memory.

6Ruy Lourenço Filho (apud LOURENÇO FILHO, 2001, p. 5) registers that his father (Manoel B. Lourenço Filho) took “the document his master and professor Antonio de Sampaio Dória, who would represent represent the Nationalist League of São Paulo, in CIEP-RJ. Sampaio Dória presented his memory about national education and the plan elaborated by Lourenço Filho attached. The day after the conference, Professor Lourenço Filho became a national name."

7Sirinelli (1986; 1990; 1992; 1998; 2003); Tilly (1976; 1993. 1996; 2004) and McAdam, Tarrrow, Tilly (2009).

The translation of this article into English was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG - through the program of supporting the publication of institucional scientific journals

Received: August 29, 2020; Accepted: October 05, 2020

texto en

texto en