Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 05-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469820016

ARTIGO

RELIGIOUS EDUCATION IN THE NATIONAL COMMON CURRICULAR BASE: SOME CONSIDERATIONS

1Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais (PUC Minas). Bolsista CAPES. Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. <tacianabrasil@yahoo.com.br>

This article discusses Religious Education at the National Curriculum Common Base (BNCC), a resulting document from public education policies in Brazil´s period of redemocratization. In accordance with the provisions of the Federal Constitution of 1988, education must form citizens capable of living in a democratic society. However, historically, Religious Education has always been linked to confessional and political interests. Even so, it was included in the BNCC. Through documentary research, we sought to understand the process of building this document, the changes undergone by the Religious Education proposal throughout this process, and the skills and abilities that the student has to develop through the subject. We concluded that the inclusion in the BNCC is a possibility of epistemological development of Religious Education never before experienced. The democratic process of building the BNCC gave it greater legitimacy, and the curricular choices suit it to the goals for education in a democratic and citizen society.

Keywords: Religious Education; National Common Curricular Base; Skills; Abilities

Este artigo discute sobre o Ensino Religioso na Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC), documento resultante das políticas públicas de educação no período da redemocratização brasileira. Atendendo ao previsto na Constituição Federal de 1988, a educação deve formar cidadãos aptos à vivência em uma sociedade democrática. Porém, historicamente, o Ensino Religioso sempre foi ligado a interesses confessionais e políticos. Ainda assim, foi contemplado na BNCC. Através de pesquisa documental, procurou-se compreender o processo de construção do documento, as alterações sofridas pela proposta para o Ensino Religioso ao longo do processo, e as competências e habilidades que se espera que o aluno desenvolva através do conteúdo. Concluiu-se que a presença na BNCC possibilitou um desenvolvimento epistemológico para o Ensino Religioso nunca experimentado até então. O processo democrático de construção do documento conferiu-lhe maior legitimidade, e as escolhas curriculares feitas o adequam aos objetivos para a educação em uma sociedade democrática e cidadã.

Palavras-chave: : Ensino Religioso; Base Nacional Comum Curricular; Competências; Habilidades

Este artículo aborda la Educación Religiosa en la Base Común del Currículo Nacional (BNCC), un documento resultante de las políticas de educación pública en el período de la redemocratización brasileña. De conformidad con las disposiciones de la Constitución Federal de 1988, la educación debe formar ciudadanos capaces de vivir en una sociedad democrática. Sin embargo, históricamente, la Educación Religiosa siempre ha estado vinculada a intereses confesionales y políticos. Aun así, lo mismo se incluyó en el BNCC. A través de la investigación documental, buscamos comprender el proceso de construcción de este documento, los cambios sufridos por la propuesta de Educación Religiosa a lo largo de este proceso y las pericias y habilidades que se espera que el estudiante desarrolle a través del contenido. Se concluyó que esta era una posibilidad de desarrollo epistemológico de la Educación Religiosa nunca antes experimentada. El proceso democrático de construcción del BNCC le dio mayor legitimidad, y las elecciones curriculares lo hicieron adecuado para los objetivos de educación en una sociedad democrática y ciudadana.

Palabras clave: Educación religiosa; Base Curricular Nacional Común; Pericias; Habilidades

INTRODUCTION

Historical target of controversies (CURY, 2004), Religious Education is the only curricular subject provided for in the Brazilian Constitution (BRASIL, 2017a). Its offer was initiated in the colonial period and continued during the Empire, always under a Catholic confessional model (SAVIANI, 2010). With the Republic Proclamation, there was a first moment of secular impetus in education, that caused the elimination of the subject. This initiative, however, did not last long. Soon the offer of the subject returned to schools, to remain until today (CUNHA, 2013).

The offer or suppression of Religious Education in Brazilian public schools has always had a political bias. The interests and desires of the population and educators were never taken into account when establishing legislation on the subject. Thus, one of the characteristics of Religious Education in Brazil is, precisely, the incipient epistemological construction (CURY, 2004).

However, from the 1970s onwards, there was a greater tendency towards the theoretical construction of Religious Education. There was still no national determination on the subject. But resolutions, decrees and state laws guided your practices. Many education departments have created study and orientation teams, which have prepared curricula proposals for the different grades. In some states, Religious Education was ecumenical or interfaith (CURY, 2010).

In addition, several entities were created to discuss the subject, such as the Council of Churches for Religious Education - CIER, in 1970; Religious Education of Public Schools - EREP, in 1972; Interfaith Education Association - ASSINTEC, in 1973; and the Interfaith Commission for Religious Education - CIERES, in 1975 (JUNQUEIRA, 2002). As a result of the work of these organizations, in 1995, in a CIER meeting, the Permanent National Forum for Religious Education - FONAPER was founded, with the objective of guaranteeing the provision of Religious Education at all levels of education, respecting diversity and the religious option of students. For this, the organization proposed to work with the Teaching Systems, assisting in the construction of appropriate curriculum, which expressed the ethics of human dignity (FONAPER, 1995).

Despite the efforts of these organizations in favor of the epistemological construction of Religious Education, Brazilian educational systems still lacked an official and national position on the model, objectives and teacher training for the subject. Especially after redemocratization, with the promulgation of the so-called Citizen Constitution (BRASIL, 2017a) and all the educational legislation that followed it.

Throughout the history of Brazilian education, Religious Education has always collaborated to maintain a country project, acculturing and shaping students according to the project intended by the governing elites (CUNHA, 2013). With the re-democratization, this type of use of subject would no longer be adequate, since the constitutional text values individual freedoms and the cultural and ethnic diversity of the population as a factor in the composition of the nation. Even so, the Constitution provides for its offer.

In this article, we discuss the first curricular document proposed by the Ministry of Education, at the national level, which guides the Religious Education: the National Common Curricular Base (BNCC). Created under the aegis of redemocratization and educational legislation pertinent to this time, the BNCC is characterized by a long process of construction, allowing consultations with the population, teachers and specialists in each knowledge area.

This paper describes the BNCC creating process, focusing on the evolution of Religious Education proposal in the document. We also analyzed the skills and abilities attributed to Religious Education in the document approved version.

We achieve these objectives through documentary research, consulting mainly legal texts, educational guidelines, preliminary versions of the BNCC, provisions of the National Education Council, websites on the construction of the BNCC, among others. We also consulted authors who helped to understand the texts under analysis.

The relevance of this text is marked by the lack of analysis of an original and unique curricular proposal in the history of Brazilian education, with regard to Religious Education. When consulting renowned authors who talk about BNCC, such as Cury, Reis and Zanardi (2018), Pacheco (2018), and Veiga and Silva (2018), we apprehende that Religious Education only appears in Pacheco (2018). Even so, the author criticizes the subject´s confessional model. This is not the model advocated by the BNCC. Therefore, we realize the need for research that adequately studies the propositions of this remarkable document on Religious Education as subject and knowledge area.

THE BNCC CREATING PROCESS

To understand the emergence of BNCC, observe the established educational policies after the re-democratization of Brazil. The first document to discuss about it is the Federal Constitution (BRASIL, 2017a), followed by the Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education (LDBEN) nº 9.394 of 1996 (BRASIL, 1996) and by Law nº 13.005 of 2014, which establishes the National Education Plan (BRASIL, 2014a).

The Chapter III, Section I of the Magna Carta (BRASIL, 2017a) determines a set of principles that govern education in the country. Among these, Article 210 establishes that “Minimum contents for basic education will be fixed, in order to ensure common basic training and respect for cultural and artistic, national and regional values” (author translation). This text, according to Cury, Reis and Zanardi (2018), is particularly important for the valorization of national culture in educational processes, safeguarding the diversity that exists internally in our country. For the authors, the document presents a proposal for “equality in difference” (p. 57, author translation).

LDBEN 9394/96 also presents the concept of curricular basis present in the Constitution. This law explains how the Republic objectives would be achieved through education (CURY; REIS; ZANARDI, 2018). Article 9 instructs that it is the responsibility of the Union, in collaboration with the States and Municipalities, to establish competencies and guidelines that guide the curriculum and minimum content for Basic Education. Without instituting a mandatory and determined character, article 26 adds that these premises will be realized through the creation of a common national base, which must be complemented to meet the peculiarities of education systems, school institutions and regional and local characteristics. LDBEN 9394/96 expresses the expectation that school education will be contextualized to the reality of the population - thus valuing the principles of plurality, diversity and non-discrimination, already provided for in the Constitution.

In a first attempt to meet these intentions, the National Curriculum Parameters (PCN’s) were promulgated in 1996. It is a collection of ten volumes. The first is an introduction to the document; six books are intended for the knowledge areas, namely: Portuguese Language, Mathematics, Natural Sciences, History, Geography, Art, Physical Education and Foreign Language; and three volumes dedicated to Transversal Themes - Ethics, Cultural Plurality and Sexual Orientation, Environment and Health (BRASIL, 1997). Macedo (2014) argues, regarding this document, that it would be a support material for teachers and managers, without any obligation to use it.

Although the PCN’s have represented an advance in the definition of scholar content at the national level, the way in which subjects and teaching and learning methodologies were chosen, without the participation and performance of schools, has been the target of much criticism (CÂNDIDO; GENTILINI, 2017). In addition, and directly related to the theme of this article, the document did not provide any guidance or direction to the only subject provided for in the constitutional text: Religious Education.

Thus, in 1997, FONAPER published a proposal for National Curriculum Parameters for Religious Education, aiming to establish a unique identity for the subject. Seeking to overcome the challenge of confessionality, a definition of religion was adopted related to the reconstruction of meanings by reading the elements of the religious phenomenon (FONAPER, 2009). Although this curricular proposition has been widely used by teachers in the field, it has never had government officiality, since it was published as a parallel document, a response to the absence of subject in the PCN’s.

Continuing with the evolution of Brazilian educational legislation, the National Education Plan (PNE), expressed in Law No. 13,005 of 2014 (BRASIL, 2014a), made a commitment to eliminate educational inequalities. In this regard, it established strategies to face the main problems: access and permanence, regional inequalities, training for work, exercise of citizenship. The document consists of twenty goals, grouped in the Ministry of Education's dissemination material (BRASIL, 2014b) in four sets: structural goals to guarantee the right to quality basic education; goals for reducing inequality and valuing diversity; goals for valuing education professionals; and goals for higher education.

The need for a national base is reaffirmed in the PNE, in the structural goals for guaranteeing the right to quality basic education. Goal 2, in its strategies 2.1 and 2.2, determines that a public consultation be carried out in order to establish learning and development objectives that will compose a common national curriculum basis. Goal 7, strategy 7.1 reaffirms the need for inter-federative participation in the process, thus ensuring respect for regional, state and local diversity. Thus, the base to be formulated should have a national character, but it should be added - and never exempted - from content due to its regional characteristics.

In June 2015, Ordinance No. 592 of the Ministry of Education established a Committee of Experts to prepare the proposal for the Common National Curricular Base. 116 specialists were appointed by the National Council of Education Secretaries - CONSED and by the National Union of Municipal Education Directors - Undime, from all units of the Federation (BRASIL, 2015b). These were divided into 29 commissions, which should contain at least 2 specialists in the knowledge field, 1 secretary manager or teacher with experience in curriculum and 1 teacher with experience in the classroom (MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO, 2018a). The commission should produce a preliminary document by the end of February 2016. From then on, it would undergo popular evaluation and be reviewed by the same commission (BRASIL, 2015b).

To write the preliminary version of the National Common Curricular Base, experts consulted curriculum documents that were already being used in the states, the Federal District and municipalities across the country (MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO, 2018d). In addition, more than a hundred documents, such as legislation, materials for teacher training, annals of events, reports, periodicals and national and international curricular proposals were used to foster discussions about the text under construction (MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO, 2018b).

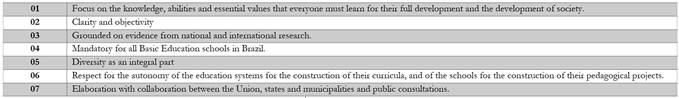

The Movement for the Common National Base reports, on its website, the election of seven principles to guide the construction of the Base, expressed in Chart 1.

Source: prepared by the author with data extracted from MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM (2017c).

Chart 1 Guiding principles for the construction of the Common National Curricular Base

Initially, as reported in Ministério da Educação (2016b), the preliminary text should be written between February and September 2015. Next, a public consultation would take place between September 2015 and March 2016, which would support a revision of the text to be delivered in April 2016. The process would continue with municipal and state seminars to discuss the text. The results of these seminars would guide the composing of the final form of the document, which would be passed on to the National Education Council in June 2016.

At the end of the composing process for the 2nd version, the seminars pointed out the need to revise many elements (MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM, 2017d). Thus, the Minister of Education instituted, through Ordinance No. 790 (BRASIL, 2016c), the BNCC Steering Committee and High School Reform. This committee was responsible for monitoring the discussion process of the 2nd version of the Base, and forwarding the final version to the National Education Council.

According to Ministério da Educação (2018a, s.p.), the third version of the document intended to solve "problems related to the clarity and relevance of the learning objectives identified in version two of the Base and pointed out during the seminars" (author translation). They also sought to articulate general learning objectives with those for each area and specific for each subject.

On April 6, 2017, the Ministry of Education delivered the 3rd version of the BNCC to the National Education Council (MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM, 2017a). After analysis and a series of public hearings, the Base was approved by 20 votes to three (MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM, 2017b). Resolution CNE / CP nº2 (BRASIL, 2017b) instituted and guided the implementation of the document throughout the country.

The 2017 version of BNCC presents guidelines for Early Childhood and Elementary School. Only in December 2018 was the document on High School approved. BNCC organizes Elementary School in five areas of knowledge that group the curricular subjects, namely: Language, with the subjects Portuguese Language, Art, Physical Education and English Language; Mathematics area, with the Mathematics subject; area of Natural Sciences, with the Science subject; Humanities area, with the subjects of Geography and History; and the area of Religious Education, with the same subject (BRASIL, 2018).

Popular participation is an important factor in the BNCC composing process. The animadversion regarding the lack of popular consultation in the National Curriculum Parameters are definitely not applicable to the BNCC. Three levels of consultation were carried out. In the first version, 12 million contributions were achieved through public consultation. In the second version, 27 state seminars provided the opportunity for 9,000 teachers to contribute. The Management Committee, made up of seven members and seven alternates, also offered their contribution. Finally, the document was analyzed by the National Education Council and public hearings. The BNCC assessment and composing process is also represented, in Portuguese, in Figure 1.

Authors such as Aguiar (2018) consider that the BNCC's composing process is “the result of disputes of conceptions and procedures (…) influenced, above all, by actors outside the government” (AGUIAR, 2018, p. 734). It is a fact that many non-governmental entities influenced the document construction process, especially after the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, the change of the ministerial body and changes in the formulation and revision methodology. However, we must remember that, for the first time, there was a popular consultation for the construction of a curriculum document. Even though other social actors have influenced the formulation of the BNCC - certainly, much more than the population - the simple possibility that citizens have an opinion on the document, during its composing, can be considered an important step in the democratization of curricula.

The deadline for implementing BNCC in the classroom is up to two years after its approval - a period that was used by the Ministry of Education to establish a dialogue with the education networks about the necessary implementation and preparation steps (MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO, 2018 ). The contextual adaptation character of the BNCC does not make it moldable, but it is an invitation for school institutions, school networks and education systems to choose their own forms of organization and proposals for progression. They just need to fulfill all the rights and learning objectives instituted at the BNCC.

Essential learning, called competencies at BNCC, can be defined as

the mobilization of knowledge (concepts and procedures), abilities (cognitive and socioemotional practices), attitudes and values, to solve complex demands of everyday life, the full exercise of citizenship and the world of work. (BRASIL, 2017b, p. 4. Author translation.).

Competencies are one of the essential elements of the BNCC. Through them, it becomes possible to offer an identity of knowledge to all students of Brazilian Basic Education. According to Cury, Reis and Zanardi (2018), this characteristic is a differential of the document, which aims to correct the inequality of opportunities by offering identical content in all schools.

In addition to combating inequality, BNCC also aims to be a project of society. The document proposes a integral education model, which offers varied knowledge, but which also promotes self-knowledge and otherness, expanding the worldview and enabling the reading of reality and recognition of one's cultural identity. Thus, BNCC assists in the transformation of society, promoting a more democratic bias (NEIRA; ALVIANO JÚNIOR; ALMEIDA, D., 2016).

THE EVOLUTION OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION AT BNCC

As previously stated, the BNCC had a process of writing and revision in several stages, with three versions for the text: the initial (BRASIL, 2015a), the second, already revised (BRASIL, 2016a), and the third, approved (BRASIL , 2018).

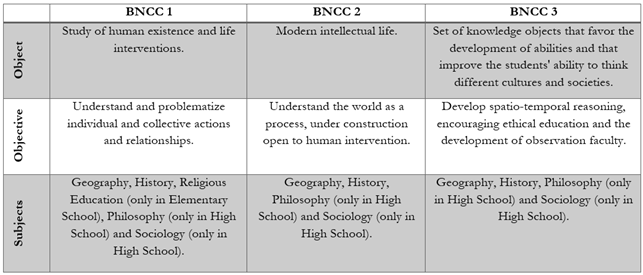

Although Religious Education appears in the three versions of the text, important changes can be seen between the versions. Starting with the fact that in the first two versions (BRASIL, 2015a, 2016a) the Humanities area is composed of the subjects History, Geography, Religious Education, Philosophy and Sociology, while the approved version (BRASIL, 2018) separates Religious Education as a knowledge area. This amendment encourages the observation of differences between the three versions of the BNCC.

In its first version (BRASIL, 2015a), the Base defines that the Humanities object is study human existence and interventions on life. Its main assumption attributes to the human being the protagonism for its existence. On these principles, each subject contributes to the construction of knowledge specificities. Throughout Elementary School, Geography, History and Religious Education cooperate in the process of understanding and problematizing individual and collective actions and relationships. The analysis of religious processes and phenomena and the questioning of religious institutions are among the area objectives.

The second version (BRASIL, 2016a, p. 152-153) defines “modern intellectual life, which problematizes, in its dimensions, the world made and / or affected by human action”. The composition of the subjects is identical to the previous version, and they have a problematic, formative and transforming function

individuals and social and power relations, thinking, knowledge and religions, cultures and their norms, policies and laws, historical times and processes, spatial forms of cultural and political organization and relations ( including representations) with nature (BRASIL, 2016a, p. 153. Author translation.).

We concluded, therefore, that religions would also be analyzed in the Humanities, according to the second version.

The third version (BRASIL, 2018) lists a set of knowledge objects, aiming to develop the abilities described in the document and improve the ability to think about different cultures and societies. Religious Education is no longer part of the Humanities area. Adapted in his own area, he became responsible for discussing all issues related to the religious phenomenon as a constitutive element of individual and collective meaning narratives, as well as the dynamics of human societies. This organization contradicts what had been deliberated in the first two versions of the BNCC.

It is clear, therefore, that the withdrawal of Religious Education from the area of Humanities represented a limitation in the prediction of dialogue. With the subjects united under the same area, and sharing learning objectives, the influence of religion in the construction of individual and collective meanings should necessarily collaborate for the work carried out in order to understand the human being, social processes and institutions. When creating a specific area for Religious Education, the final version of BNCC (BRASIL, 2018) removes the discussion about the religious phenomenon from this process. This curricular option impoverishes the Humanities, by exempting it from the discussion about the influence of the religious phenomenon in society; burdens Religious Education by imposing discussions that would be more appropriate to Geography or History; and limits teaching work, since different areas do not share specific learning objectives.

On the other hand, considering the lack of legitimacy and epistemological crises faced by Religious Education (CURY, 2004), establishing a specific area can help in the process of consolidating the assumptions of its secular model throughout the national territory. The visibility attributed to the subject, associated with the curricular unification, can produce beneficial effects to its theoretical and methodological construction.

It is necessary, however, to note that the same Resolution that institutes and guides the implementation of BNCC (BRASIL, 2017b) creates the possibility of returning Religious Education to the Humanities area, as shown in the following excerpt:

Art. 23. The CNE, upon proposal of a specific commission, will decide whether religious education will be treated as an area of knowledge or as a curricular subject in the area of Humanities, in Elementary School. (BRASIL, 2017b, p. 12. Author translation.)

In fact, on October 8, 2019, less than two years after the publication of the final version of the BNCC, the Council decided that Religious Education is no longer a knowledge area, and becomes, as curricular subject, part of the Humanities (BRASIL, 2019a; 2019b). If this decision had been taken before the approval of the BNCC, it would have been possible to choose a wording closer to the 2nd version of the Base, maintaining the benefits of a closer dialogue between Religious Education and other subjects in the Humanities. We therefore question how this interchange between the subjects will take place in future BNCC reviews.

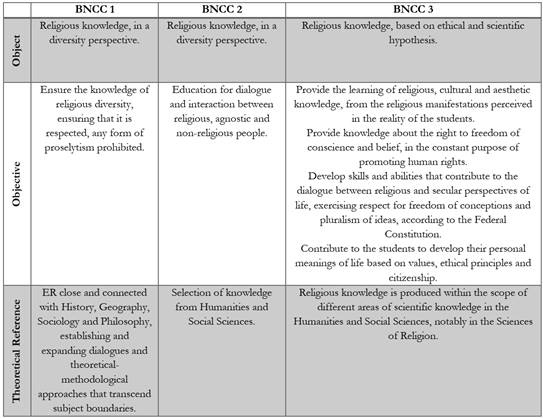

When analyzing the assumptions for Religious Education in the different versions of the National Common Curricular Base, we perceive an agreement about the Religious Education object, delimited as religious knowledge. Only the focus was changed: in the first two versions, the perspective of diversity in the analyzes was prioritized (BRASIL, 2015a, 2016a); while the final version values ethical and scientific assumptions (BRASIL, 2018).

Regarding the Religious Education object, it is important to note that this is an issue on which there is no agreement, neither between researchers in the area, nor between teachers (SCHOCK, 2012). Even so, the BNCC writers did not waver about the object definition in any version of the text. We must remember that, as seen in Chart 2, there is no consensus between the three versions of the document about the Humanities object, showing that it was possible to discuss and change the epistemological elements according to the desired purpose.

Source: Elaborated by the author with data extracted from Brasil (2015a, 2016a, 2018)

Chart 2 Comparison between the versions of the text in the area of Humanities at BNCC

Source: Elaborated by the author with data extracted from Brasil (2015a, 2016a, 2018)

Chart 3 Parallel between the versions of the Religious Education text in the National Common Curricular Base

Regarding the assumptions for Religious Education listed in the approved version of BNCC (BRAZIL, 2018), it is possible that the change in focus was due not only to epistemological issues. The invocation of ethical and scientific assumptions may have the purpose of indicating that the area no longer corresponds to the Religious Teaching of a confessional model experienced in the past, but to a scientific treatment of the religious question, accessible to all students.

We emphasize that, during the process of writing the text of the Common Base National Curriculum, as a result of Direct Action of Unconstitutionality n. 4.439, related to the provision of confessional Religious Education (PEREIRA, 2010), the Federal Supreme Court decided, by majority of votes, that Religious Education in public schools could have a confessional nature (STF…, 2017). Despite this decision, none of the versions of the text considered the adoption of this model for the subject. No models such as the interfaith and the ecumenical were considered. Even so, the text does not problematize the concept of laicity.

We think that the absence of debate about the concept of secularity in the BNCC text may have an explanation related to the identity and belonging of the editors in the area/subject. As indicated by Cunha (2016), all of them were members of FONAPER - including, one of them was its national coordinator. One of the objectives of FONAPER's work is precisely to promote secular models of school Religious Education. Perhaps, because they are used to the discussion in an environment of training and activism, the writers have considered it unnecessary to take the discussion to the text, just applying the concepts.

Over the past 25 years, FONAPER has had a considerable epistemological evolution. The National Curriculum Parameters for Religious Education (FONAPER, 2009) were strongly influenced by Theology and Comparative Religions. Over the past few decades, the institution's epistemological formulation has evolved towards a model of Religious Education whose laicity is based on the appreciation of diversity, as can be read in the text by Ricardo de Oliveira (2020), published on the institution's portal.

It is concluded, therefore, that the editors chose not to take the discussion about the concept of laicity into the document - although they did not, at any time, have the contradiction. In future BNCC reviews, it would be important to insert this discussion. First, because it helps the reader to understand the objectives of Religious Education. Then, because the epistemological development expected for the subject may foster other theoretical currents, and FONAPER's premises may cease to be hegemonic in our country.

Resuming the discussion about the objectives for Religious Education, we noticed that they were changed during the BNCC editing process. If the objectives are what you want to achieve through the object, and if the object has practically not been changed, why have the objectives changed so severely? The first and second versions of the document (BRASIL, 2015a, 2016a) basically deal with respect and coexistence between individuals with different religious options, while the final version (BRASIL, 2018) presents a list composed of four objectives, related to knowledge religious, freedom of belief, religious dialogue and building a sense of life. We consider, therefore, that the crisis of definition of the object of Religious Education was not adequately problematized by the editors of the area, reappearing in the definition of the eligible objectives.

The choice of the theoretical references that supports school Religious Education is also not unanimous among the versions of the BNCC. In the first version (BRASIL, 2015a), when the subject was still part of the Humanities, its proximity and connection with the other members of the area stimulated dialogues and approaches that should go beyond its disciplinary boundaries. The second version (BRASIL, 2016a) understands that Religious Education will be referenced in a selection of knowledge from the Humanities and Social Sciences. The third and definitive version (BRASIL, 2018) understands that religious knowledge, the object of the subject, is “produced within the scope of the different areas of scientific knowledge of the Humanities and Social Sciences, notably the Science(s) of Religion(s) ”(BRASIL, 2018, p. 434. Author translation).

We emphasize that the definition presented by the first and second versions of the BNCC (BRASIL, 2015a, 2016a) do not consider Religious Education a didactic transposition of the Sciences of Religion (JUNQUEIRA, 2013), but a differentiated approach to the themes that will be developed by the Humanities. The third version of the text (BRASIL, 2018) marks the Sciences of Religion as the preferred space for the production of knowledge. The definition of a science as a reference can be considered a gain for the subject, since it marks its scientific identity and validation. And, to a certain extent, it provides a space for the construction of knowledge separate from the other subjects of the Humanities - which is, at least, ironic, since for CAPES the Sciences of Religion are part of the Greater Humanities Area (MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, 2018c).

RELIGIOUS EDUCATION IN THE FINAL BNCC VERSION: CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT SKILLS AND ABILITIES

As a curricular proposal, BNCC establishes general competences that should be pursued in the entire educational process. Each knowledge area has its own specific skills, which must dialogue with the general ones. Like other areas, Religious Education has its own specific skills:

SPECIFIC SKILLS OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION FOR FUNDAMENTAL EDUCATION

Know the structuring aspects of different traditions / religious movements and philosophies of life, from scientific, philosophical, aesthetic and ethical assumptions.

Understand, value and respect the religious manifestations and philosophies of life, their experiences and knowledge, in different times, spaces and territories.

Recognize and take care of yourself, the other, the community and nature, as an expression of the value of life.

Coexist with the diversity of beliefs, thoughts, convictions, ways of being and living.

Analyze the relationship between religious traditions and scenes from culture, science, technology and the environment.

Debate, problematize and take a stand against the discourses and practices of intolerance, discrimination and religious violence, in order to ensure human rights in the constant exercise of citizenship and the culture of peace. (BRASIL, 2018, p. 435. Author translation.).

Comparatively analyzing the specific competences in the Human Sciences area, we realize that they dialogue directly with those of Religious Education. The importance of identity, recognition of social and cultural affiliation, respect and appreciation of diversity, care for nature and the common welfare are expressed in both areas, and could easily dialogue if they comprised a single body of learning objectives . This, however, was not the choice of the team that organized and drafted the final version of the BNCC - which limited the possibilities of dialogue for Religious Education, but gave it greater clarity as to its own competencies.

The content to be worked on in Religious Education, to achieve the skills described above, was organized into three thematic units. The Identities and Alterities unit, which occurs only in the early years of Elementary School, emphasizes the perception and respect for differences, and the construction of identity. The Religious Manifestations unit discusses symbols, rites, spaces, territories and religious leaders, aiming to offer knowledge about the different traditions and respect for different religious experiences and manifestations. Finally, the Religious Beliefs and Philosophies of Life Unit works with the myths, beliefs, narratives, doctrines and traditions of religious groups and philosophies of life.

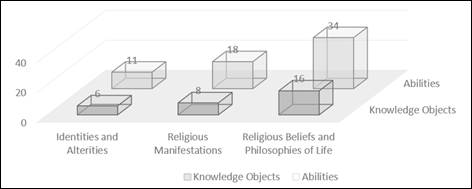

Each Thematic Unit has Knowledge Objects, which contain Abilities that the student aims to develop through the subject. There are a total of 30 Objects and 63 Abilities, distributed as follows:

Table 1 Objetos de Conhecimento e Habilidades por Unidade Temática

| Identities ans Alterities | Religious Manifestations | Religious Beliefs and Philosophies of Life | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Knowledge Objects | Abilities | Knowledge Objects | Abilities | Knowledge Objects | Abilities |

| 1º | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| 2º | 5 | 1 | 2 | - | - | |

| 3º | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | - | - |

| 4º | - | - | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| 5º | - | - | - | - | 3 | 7 |

| 6º | - | - | - | - | 3 | 7 |

| 7º | - | - | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| 8º | - | - | - | - | 4 | 7 |

| 9º | - | - | - | - | 3 | 8 |

| TOTAL | 6 | 11 | 8 | 18 | 16 | 34 |

Source: Elaborated by the author with data extracted from Brasil (2018)

Table 1 shows that the Identities and Alterities Thematic Unit only appears in the first three years of Elementary School, not returning at any later time. The Religious Manifestations Unit appears from the 1st to the 4th year, returning punctually in the 7th. Religious Beliefs and Philosophies of Life, on the other hand, appear for the first time in the 4th year, and remain until the 9th, being the only Thematic Unit studied in most years (5th, 6th, 8th and 9th).

The quantitative difference in Objects and Abilities between the Religious Education Thematic Units is crucial, as can be seen from the graph:

Source: Elaboratedby the author with data extracted from Brasil (2018)

Figure 2 Knowledge Objects and Abilities by Thematic Unit

The observation of these data leads to the formulation of hypotheses that explain them. At first, it is necessary to question the fact that the units Identities and Alterities and Religious Beliefs and Philosophies of Life never appear in parallel in the same grade of Elementary School. It is possible that the unit was considered an introduction to the other. Thus, at the beginning of Elementary School, an introduction to religious thought would be made, considering one's own identity and respect for difference, and then proceeding to the analysis of beliefs in general. The Religious Manifestations unit, in this case, would be responsible for establishing a link between those who would carry the guiding thread of the subject.

In addition to this hypothesis, a quantitative analysis of the data may suggest that greater importance was attached to the Thematic Unit Religious Beliefs and Philosophies of Life (34 Abilities), followed by Religious Manifestations (18 Abilities), and finally by Identities and Alterities (11 Abilities). In this case, we assume that the focus of analysis of religious knowledge, which is the object of the Religious Education at BNCC, is the thought expressed in beliefs and philosophies, to the detriment of the practices present in religious manifestations. The recognition of one's own identity and alterity, in this case, would be important for the adoption of a personal position on the theme, without, however, disrespecting the others.

Jointly considering the form of dispersion of Thematic Units over the years of Elementary School, as well as the quantitative aspects of Knowledge Objects and Abilities of each Unit, the existence of a trajectory for the development of the skills sought at BNCC is confirmed. The educational process begins with the perception of differences and the construction of an identity, continues with the recognition of actions and practices linked to the religious phenomenon, and develops towards the understanding of religious or philosophical thinking that motivates individuals in their actions.

This thesis can be corroborated once again through the analysis of the vocabulary chosen for the construction of the Abilities in each Thematic Unit. In Identities and Alterities, in the early years of Elementary School, verbs are used that make up a semantic field specific to the theme: identify, welcome, recognize, value, distinguish, respect, characterize. In Religious Manifestations, although the vocabulary is quite similar, two verbs that refer to the recognition of the religious phenomenon are presented: exemplify and discuss. The Unit Religious Beliefs and Philosophies of Life, which has the broadest vocabulary of the three, is the only one that uses verbs that refer to reflection and taking a personal position: analyzing, debating and developing.

Table 2 - Quantitative of verbs used in Religious Education Abilities at BNCC

| Identities and Alterities | Religious Manifestations | Religious Beliefs and Philosophies of Life | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identify | 6 | 9 | 10 |

| Reconognize | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| Respect | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Welcome | 1 | 1 | - |

| Value | 1 | - | 1 |

| Distinguish | 1 | - | - |

| Characterize | 1 | 3 | - |

| Exemplify | - | 2 | 1 |

| Discuss | - | 1 | 5 |

| Analyzing | - | - | 6 |

| Debating | - | - | 1 |

| Developing | - | - | 1 |

Source: Elaborated by the author with data extracted from Brasil (2018)

The vocabulary chosen for the formulation of Religious Education Abilities is consistent with the epistemological proposal presented by BNCC. The verbs that are most repeated are those related to the observation of the religious phenomenon: to identify and recognize. We emphasize the occurrence of verbs that refer to reflection and critical positioning - an element that suggests that the objective of the educational process is the adoption of a personal purpose by the student, and not the imposition of any religious faith.

The writers' choice regarding the establishment of a development trajectory that starts from personal recognition to the analysis of the phenomenon, as well as the adoption of a vocabulary that denotes a critical position of the student emphasize the non-denominational option of this pedagogical proposal. In addition, we must remember that not only religious beliefs, but also philosophies of life - such as atheism and agnosticism - are covered by the BNCC. This characteristic goes beyond the old criticism of the trans-confessional and inter-confessional models of Religious Education (DANTAS, 2004), which validated religious thinking to the detriment of philosophies of life.

This option, together with the emphasis on otherness and respect for differences, highlights the agreement of Religious Education presented at BNCC with the Federal Constitution (BRASIL, 2017a) and with all educational legislation that follows its principles, such as LDBEN 9394 / 96 (BRASIL, 1996) and the National Education Plan (BRASIL, 2014a). Its aspect of valuing identity and diversity is consistent with the model of nation sought after the period of redemocratization. Despite all the historical controversies regarding school Religious Education (CURY, 2004), the proposal for the subject presented at BNCC (BRASIL, 2018) serves the same purposes presented in the documents that establish the objectives of school education as a whole, helping in the construction of identity, citizenship and a critical and reflective attitude towards elements of common life.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

It is well known that, throughout the history of Brazilian education, the BNCC was the first curricular document whose composing considered a popular consultation. It is equally important that Religious Education was maintained in the document after popular consultation. Such permanence can be considered a first step to resolve doubts arising from the subject's controversial trajectory. After so many public consultations and specialists, the Ministry of Education has endorsed that Religious Education, under an appropriate model, can contribute to training for the exercise of citizenship.

The trajectory of construction of the Religious Education text at BNCC had more comings and goings than documents from other knowledge areas and subjects. None of these has ever been questioned or omitted in any of the preliminary versions of the BNCC (FONAPER, 2020). This is not surprising, given the plurality of proposals experienced so far. The unification promoted through the BNCC is very important, since it leads to the epistemological development of the area, the possibilities of teacher training and the methodological proposals.

It is clear that the subjects listed for Religious Education at BNCC value multiculturalism and religious diversity. In the meantime, we highlight the insertion of philosophies of life in the debate about different religiouness. We also noticed that the learning objectives outlined prioritize the recognition and appreciation of the student's identity, as well as his critical reflection and positioning regarding the their own meaning narrative.

We recognize, however, that the BNCC composing process had limitations. Just as, historically, school Religious Education had complexities and inconsistencies. However, the permanence of the subject in BNCC, especially after popular consultations, gives it new perspectives. Greater legitimacy, epistemological growth and utility in the process of developing citizenship and recognizing diversity are part of these expectations.

Today, society is full of examples of how to use religious discourse in an aggressive, prejudiced and exclusive way. We hope that the presence in public schools of a Religious Education that values diversity in all its aspects promotes a social construction in which these intolerances no longer find space. It is hoped that Religious Education will enable students to recognize themselves and develop their own identity, but also introduce them to other identities and possibilities, raising awareness of the value of diversity and respect for differences.

The presence of Religious Education in BNCC and in public education has as main positive points the discussion about the search for meaning (religious or not) for the construction of the students' identity and life project, the contemplation of the diversity of possibilities, and their recognition as equally valid. In these aspects, and not in confessionalism, the provision of Religious Education must be based on public schooling.

REFERÊNCIAS

AGUIAR, Márcia Ângela da S. Política educacional e a Base Nacional Comum Curricular: o processo de formulação em questão. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 18, n. 13, p. 722-738, set./dez.2018. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.curriculosemfronteiras.org/vol18iss3articles/aguiar.pdf >. Acesso em:01 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. 1ª versão. Brasília: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, 2015a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://historiadabncc.mec.gov.br/#/site/inicio >. Acesso em:23 set. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. 2ª versão revista. Brasília: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, 2016a. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://historiadabncc.mec.gov.br/#/site/inicio >. Acesso em: 23 set. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. 3ª versão. Brasília: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, 2018. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/abase >. Acesso em:30 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição. (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília: Supremo Tribunal Federal, Secretaria de Documentação, 2017a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/legislacaoConstituicao/anexo/CF.pdf >. Acesso em: 30 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.005 de 25 de Junho de 2014. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 26 jun. 2014a. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm >. Acesso em: 17 set. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394 de 20 de Dezembro de 1996. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 23 dez. 1996. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/Ccivil_03/leis/L9394.htm >. Acesso em:30 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Súmula de pareceres. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 20 dez. 2019a, p. 142. Disponível em: < Disponível em: https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/sumula-de-pareceres-234647974 >. Acesso em: 19 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Gabinete do Ministro. Portaria nº 592, de 17 de Junho de 2015. Institui Comissão de Especialistas para a Elaboração de Proposta da Base Nacional Comum Curricular Diário Oficial da União, ed. 114, Brasília-DF, 18 jun. 2015b, p. 16. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=21361-port-592-bnc-21-set-2015-pdf&category_slug=setembro-2015-pdf&Itemid=30192 >. Acesso em: 19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASILMinistério da Educação. Gabinete do Ministro.. Portaria nº 790, de 27 de Julho de 2016. Institui o Comitê Gestor da Base Nacional Comum Curricular e reforma do Ensino Médio. Diário Oficial da União, ed. 144, Brasília-DF, 28 jul.2016c, p. 16. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://imprensanacional.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/21776972/do1-2016-07-28-portaria-n-790-de-27-de-julho-de-2016-21776889 >. Acesso em:19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Parecer do Conselho Nacional de Educação nº CP 8. Relator: Ivan Cláudio Pereira Siqueira. Brasília, 08 de outubro de2019b. Disponível em: < Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=138411-pceb008-19&category_slug=janeiro-2020&Itemid=30192 >. Acesso em:19 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Planejando a próxima década: conhecendo as 20 metas do Plano Nacional de Educação. Brasília: Ministério da Educação / Secretaria de Articulação com os Sistemas de Ensino, 2014b. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://pne.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/pne_conhecendo_20_metas.pdf >. Acesso em:17 set. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Fundamental.. Parâmetros curriculares nacionais: introdução aos parâmetros curriculares nacionais. Brasília: Ministério da Educação e Cultura / Secretaria de Educação Fundamental, 1997. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/ >. Acesso em:01 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Parecer do Conselho Nacional de Educação nº CP 2. Relator: Eduardo Deschamps. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 22 dez. 2017b, p. 41-44. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=79631-rcp002-17-pdf&category_slug=dezembro-2017-pdf&Itemid=30192 >. Acesso em: 19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

CÂNDIDO, Rita de Kássia; GENTILINI, João Augusto. Base Curricular Nacional: reflexões sobre autonomia escolar e o Projeto Político-Pedagógico. Revista Brasileira de Política e Administração da Educação, Goiânia, v. 33, n. 2, p. 323-336, maio/ago. 2017. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/rbpae/article/view/70269 >. Acesso em:18 set. 2018. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Luiz Antônio. A entronização do ensino religioso na Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 37, n. 134, p. 266-284, jan./mar.2016. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.cedes.unicamp.br >. Acesso em: 19 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Luiz Antônio. Educação e religiões: a descolonização religiosa da Escola Pública. Belo Horizonte: Mazza, 2013. [ Links ]

CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil. Ensino Religioso na escola pública: o retorno de uma polêmica recorrente. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 27, p. 183-191, set./dez. 2004. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-24782004000300013 >. Acesso em: 20 set. 2017. [ Links ]

CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil. Ensino Religioso: retrato histórico de uma polêmica. In: CARVALHO, Carlos Henrique de; GONÇALVES NETO, Wenceslau (Orgs.). Estado, Igreja e Educação: o mundo ibero-americano nos séculos XIX e XX. Campinas: Alínea, 2010. p. 11-50. [ Links ]

CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil; REIS, Magali; ZANARDI, Teodoro Adriano Costa. Base Nacional Comum Curricular: dilemas e perspectivas. São Paulo: Cortez, 2018. [ Links ]

DANTAS, Douglas Cabral. O Ensino Religioso escolar: modelos teóricos e sua contribuição à formação ética e cidadã. Horizonte, Belo Horizonte, v. 2, n. 4, p. 112-124, 1º sem.2004. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/horizonte/article/view/583 >. Acesso em:21 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

FONAPER. Carta de Princípios. Florianópolis, 1995. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.fonaper.com.br/carta-principios.php> . Acesso em: 17 set. 2017. [ Links ]

FONAPER. Ciclo de Debates 25 anos FONAPER: o Ensino Religioso na Base Nacional Comum Curricular. YouTube, 23 de julho de 2020. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VM_Wptpl1U&t=8s >. Acesso em: 23 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

FONAPER. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais: Ensino Religioso. 9. ed. São Paulo: Mundo Mirim, 2009. [ Links ]

FONAPER, Sérgio Rogério Azevedo. Ciência da religião aplicada ao Ensino Religioso. In: PASSOS, João Décio; USARSKI, Frank(Orgs.). Compêndio de Ciência da Religião. São Paulo: Paulinas, Paulus, 2013. p. 603-614. [ Links ]

JUNQUEIRA, Sérgio Rogério Azevedo. O processo de escolarização do Ensino Religioso no Brasil. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2002. [ Links ]

JUNQUEIRA, Sérgio Rogério Azevedo; NASCIMENTO, Sérgio Luís do. Concepções do Ensino Religioso. Numen: revista de estudos e pesquisa da religião, Juiz de Fora/MG, v. 16, n. 1, p. 783-810, jan./jun. 2013. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://numen.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/numen/article/view/2141 >. Acesso em:19 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. Base Nacional Curricular Comum: novas formas de sociabilidade produzindo sentidos para educação. Revista e-Curriculum, São Paulo, v. 12, n. 03, p. 1530-1555, out./dez. 2014. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://revistas,pucsp.br/index.php/curriculum >. Acesso em:18 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC). [S.l.]: Perguntas frequentes, 2018a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://historiadabncc.mec.gov.br/#/site/faq >. Acesso em: 19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Biblioteca. [S.l.]: Preparação, 2018b. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://historiadabncc.mec.gov.br/#/site/biblioteca >. Acesso em:19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior. Sobre as áreas de avaliação. Brasília: Avaliação, 2018c. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://capes.gov.br/avaliacao/sobre-as-areas-de-avaliacao >. Acesso em:26 ago. 2018. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Princípios que nortearam a Base Curricular estão na Constituição. [S.l.]: Educação Básica, 2016b. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://portal.mec.gov.br/ultimas-noticias/211-218175739/34281-principios-que-nortearam-a-base-curricular-estao-na-constituicao >. Acesso em: 19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Propostas curriculares pelo Brasil. [S.l.]: Preparação, 2018d. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://historiadabncc.mec.gov.br/#/site/propostas >. Acesso em:19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM. Base é entregue ao Conselho Nacional de Educação - Confira tudo![S.l.]: Novidades sobre a Base, 2017a. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://movimentopelabase.org.br/acontece/base-entregue-cne/ >. Acesso em:19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM. Linha do tempo. [S.l.]: Movimento pela Base Nacional Comum, 2017b. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://movimentopelabase.org.br/linha-do-tempo/ >. Acesso em: 19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM. Quem somos. [S.l.]: Movimento pela Base Nacional Comum, 2017c. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://movimentopelabase.org.br/quem-somos/ >. Acesso em:19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

MOVIMENTO PELA BASE NACIONAL COMUM. Seminários Estaduais da BNCC: posicionamento conjunto de Consed e Undime sobre a segunda versão da Base Nacional Comum Curricular. [S.l.]: Análises da 2ª versão, 2017d. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://movimentopelabase.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2016_09_14-Relato%CC%81rio-Semina%CC%81rios-Consed-e-Undime.pdf >. Acesso em:19 set. 2018. [ Links ]

NEIRA, Marcos Garcia; ALVIANO JÚNIOR, Wilson; ALMEIDA, Déberson Ferreira de. A primeira e segunda versões da BNCC: construção, intenções e condicionantes. EccoS Revista Científica, São Paulo, n. 41, set./dez. 2016, p. 31-44. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=71550055003 >. Acesso em: 18 set. 2018. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Ricardo de. Ensino Religioso: cultura e inclusão. [S.l.]: Espaço Pedagógico, 2020. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://fonaper.com.br/ensino-religioso-cultura-e-inclusao/ >. Acesso em:19 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

PACHECO, José. Reconfigurar a escola: transformar a educação. São Paulo: Cortez, 2018. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, Deborah Macedo Duprat de Britto. Ação Direta de Inconstitucionalidade nº 4439, de . 2010 Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/geral/verPdfPaginado.asp?id=635016&tipo=TP&descricao=ADI%2F4439 >. Acesso em:19 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Dermeval. História das ideias pedagógicas no Brasil. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2010. [ Links ]

SCHOCK, Marlon Leandro. Aportes epistemológicos para o Ensino Religioso na escola: um estudo analítico-propositivo. 2012. 317 f. Tese (Doutorado) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Teologia, Escola Superior de Teologia, São Leopoldo, 2012. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://tede.est.edu.br/tede/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=372 >. Acesso em:01 set. 2017. [ Links ]

SIQUEIRA, Giseli do Prado. O Ensino Religioso nas escolas públicas do Brasil: implicações epistemológicas em um discurso conflitivo, entre a laicidade e a confessionalidade num estado republicano. 343 f. Tese (Doutorado) - Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, 2012. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufjf.br/jspui/handle/ufjf/1967 >. Acesso em: 19 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

STF conclui julgamento sobre ensino religioso nas escolas públicas. Brasília: Notícias STF, 2017. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/cms/verNoticiaDetalhe.asp?idConteudo=357099 >. Acesso em:31 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Ilma Passos Alencastro; SILVA, Edileuza Fernandes da. Ensino Fundamental: gestão democrática, projeto político-pedagógico e currículo em busca da qualidade. In: VEIGA, Ilma Passos Alencastro; SILVA, Edileuza Fernandes da (Orgs.). Ensino Fundamental: da LDB á BNCC. Campinas: Papirus, 2018. p. 43-68. [ Links ]

Received: April 11, 2020; Accepted: August 20, 2020

texto en

texto en