Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 09-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469824551

ARTICLE

THE (NON) COMPLIANCE OF MUNICIPAL EDUCATION PLANS TO SPECIFIC TEACHER TRAINING AT A HIGHER LEVEL

1Federal University of Tocantins (UFT). Tocantinópolis, TO, Brazil. <locatelli@uft.edu.br>

he present paper addresses the treatment given to teacher training in municipal education plans. It aims to analyze the municipalities’ commitment to specific higher education training and its possible approximations with the tendency to make initial teacher training more flexible. The research, predominantly documental in nature, covered ten municipal education plans in the northern region of the state of Tocantins and collected information corresponding to what is recommended by Goal 15 of the PNE (2014). It is observed, in the proposals of the local educational planning, greater adherence or repercussion of the demands that originated in the national plan and a lower incidence of own initiatives. A significant part of the analyzed municipal plans adopts a posture of indirect or partial commitment to specific higher education, making the indicator that reveals the fulfillment of the goalless evident. There is also a reasonable acceptance or repercussion of technicist tendencies for teacher training, emphasizing the value of practical experiences and ignoring the defense of university/theoretical/scientific and critical training.

Keywords: Teacher training; practical experience; municipal plans

O artigo aborda o tratamento dado à formação docente nos planos municipais de educação. Tem como objetivo analisar o comprometimento dos municípios com a formação específica de nível superior e suas possíveis aproximações com tendências de flexibilização da formação inicial do professor. A pesquisa, de caráter predominantemente documental, abarcou dez planos municipais de educação da região Norte do estado do Tocantins e levantou informações correspondentes ao que preconiza a Meta 15 do PNE (2014). Constata-se, nas proposições do planejamento educacional local, maior adesão ou repercussão das demandas que tiveram origem no plano nacional e menor incidência de iniciativas próprias. Parte significativa dos planos municipais analisados adota uma postura de comprometimento indireto ou parcial com a formação específica de nível superior, tornado menos evidente o indicador que revela o cumprimento da meta. Constata-se, ainda, uma razoável aceitação ou repercussão de tendências de caráter tecnicistas para a formação do professor, enfatizando a valorização de experiências práticas e ignorando a defesa da formação universitária/teórica/científica e crítica.

Palavras-chave: Formação docente; experiência prática; Planos municipais

El artículo analiza el tratamiento dado a la formación del profesorado en los planes de educación municipal. Su objetivo es analizar el compromiso de los municipios con la formación específica de la educación superior y sus posibles aproximaciones con tendencias de flexibilidad en el desarrollo académico profesional del docente. La investigación, de carácter predominantemente documental, cubrió 10 (diez) planes de educación municipal en la región norte del estado de Tocantins y recabó información correspondiente a lo que defiende el Objetivo 15 (2014) del PNE. En las propuestas locales de planificación educativa, existe una adherencia significativa a las demandas que se originaron a nivel nacional y una baja incidencia de iniciativas propias. También se observa que una parte importante de los planes municipales analizados adopta una actitud de compromiso indirecto con la educación superior específica, sin establecer los pasos y plazos para lograr el objetivo. También existe una aceptación o repercusión razonable de las tendencias, de carácter técnico, que ponen en perspectiva la importancia de la educación universitaria, con una sólida solidez teórica, científica y crítica de los fundamentos de la educación y que enfatizan la valorización de las experiencias prácticas.

Palabras clave: Formación docente; La experiencia práctica; Planes municipales

INTRODUCTION

The teacher training issue for basic education in higher education is not something resolved in Brazilian reality. At the beginning of 20th century, this discussion was already in place, gaining evidence with the ‘Pioneers Manifesto of New Education’. According to Cury (2003, p. 132) "The importance awareness of primary teaching was very highlighted in the ‘Pioneers Manifesto of New Education’”. This debate, held in a context of claiming education as a nation project and based on science, also raised the understanding of the teacher's work as something complex, which required scientific and philosophical training, overcoming the idea of a merely technical or doctrinal activity. This elevated the teacher's work to a level close or equivalent to other professions of recognized academic and intellectual tradition.

The recognition of the teaching work specificities and dimensions, as well as the definitions (legal requirements) about the training requirements for the teaching exercise in Brazil reveal a reality with several obstacles and dilemmas. The obstacles are related to different factors, among which are those of a more comprehensive nature, such as the country's historical economic inequality, the high social and educational debt to a large part of the population, and the hegemonic understanding of education itself, which figured more as an individual good and at economic interests’ service than as a collective good and at humanity’s service. The dilemmas, as analyzed by Saviani (2011), express embarrassing situations with opposing outcomes, as is the case of technical teacher training versus literate teacher training, or the model that privileges cultural-cognitive content versus the didactic-pedagogical model. Such situations, among others, manifested in official documents, do not contribute to a "safe orientation and do not guarantee the elements for a consistent training." (SAVIANI, 2011, p. 14).

In the present paper, in which we present the results on teacher training in municipal education plans, we also deal with national policy particularities on specific higher education training. The historical and legal aspects analysis of this national policy, seen from a perspective that defends the teaching work autonomy and valorization reveals conceptions and tendencies that affect all elaboration spheres and educational policy execution.

Teacher education, especially since the 1990s in Brazil, has been strongly influenced by a tendency to devalue theoretical/scientific/academic knowledge under the pretext of valuing the teachers’ knowledge developed in their daily lives (DUARTE, 2003). This trend is correlated to the set of educational reforms of the period. They brought a strong management intervention to the public school system, with external evaluations, ranking, parents’ (clients’) control, volunteerism and accountability, corroborating the teaching work restructuring. As a reforms’ result, according to Oliveira (2004), we can verify the teachers’ disqualification and devaluation. "The current reforms tend to remove their autonomy, understood as a condition to participate in their work’s conception and organization." (OLIVEIRA, 2004, p. 1132).

If, on one hand, the valorization of practical or everyday experience is presented in the sense of bringing teacher education closer to the school, on the other hand, it weakens the narrative in defense of specific and intellectual higher education for teachers. Such orientation has been established, not only by a criticism of theoretical initial training, but in defense of the so-called knowledge or competencies, which will be acquired in quick training and practical immersions, easily developed and certified by schools or other institutions, not necessarily universities.

Thus, in the present paper, without intending to generalize, we seek to evaluate how this debate has echoed in local reality. How have countryside small cities, with their specificities and limitations, understood their role in teacher education? How are they reflecting or participating in national and international trends and orientations? Which initiatives, intentions or local actions reveal their autonomy, particularities or singularities?

The empirical data related here were extracted from a broader survey within the scope of the project s research on teacher training at a subnational level. In the present case, the cut seeks to reveal ten municipalities’ commitment in the north of Tocantins’ State with specific higher level teacher training. The analysis considers local education planning specificities in face of the actions and guidelines contained in Goal 15 of the National Education Plan (PNE, 2014).

We evaluated the municipalities participation based on three types of manifestations: 1) initiatives that refer to PNE’s actions indicating local manifestation or adherence; 2) municipal initiatives related to the process of specific higher education training for their teaching staff; and 3) PNE’s (2014) strategies indicating federal government actions, trends, or guidelines, in some cases, incorporated in municipal plans, indicate adherence to the intentions and directions of the national plan or even inconsistencies and weaknesses in the local planning process.

HIGHER EDUCATION FOR TEACHING IN BRAZIL

When we deal with teacher training from a university education point of view (higher or 3rd degree), the Brazilian education history takes us back to the mid-1930s, when institutions that dealt with teaching profession preparation in São Paulo and in the Federal District were incorporated by universities. According to Tanuri (2000), in 1934, the Institute of Education of São Paulo was incorporated by São Paulo University and, in 1935, Teachers' School was incorporated by the University of the Federal District. In both cases, according to the author, the main objective was to deal with students’ pedagogical training coming from the arts, sciences and philosophy areas.

We must also make reference to the Pedagogy course that was created by the decree 1,190, of April 4, 1939. It was a three-year undergraduate course, like other courses created within the School de Philosophy, Sciences and Literature scope, established by law number 452, of July 5, 1937, which was renamed as National School of Philosophy. All bachelor students who regularly concluded the didactics course, according to article. 20 of the aforementioned decree, would be granted with a bachelor's degree according to their study’s field. In the pedagogy’s course, this aimed "[...] the double function of forming bachelors, to act as education technicians, and licensees, intended for teaching in normal courses." (TANURI, 2000, p. 76)

The 1930s initiatives, although important as a historical landmark for the recognition of the teaching work specialty and complexity, were not decisive and comprehensive enough in the sense of promoting, throughout the country, higher education as an indispensable requirement for the teaching activity in all education levels. In the same way, without ignoring the importance of the manifesto, we must consider that the movement was clearly linked to the epistemological progressive education principles. This, as we know, rather than valuing the appropriation of scientific/philosophical/academic knowledge, defended the production of knowledge by the student. This same epistemological basis, according to Duarte (2003), underlies the trend of the reflective teacher, dominant in Brazilian educational policy guidelines for teacher training from the 1990s on.

In the mid 1990s, more than 60 years after the manifesto, at the creation of the current Directives and Bases of National Education Law (LDB 9394/96) it is determined, according to article 62, that "The training of basic education teachers will be done at a higher level, in a full degree course [...]" (BRASIL, 1996). However, contradicting this same determination and weakening the narrative that took all levels of teaching, a theoretical and intellectual activity, it was admitted, as a minimum necessary training for the teaching exercise in early childhood education and initial series of elementary education, those trained in high school.

It is also worth remembering that, even with the new wording of the LDB article 62, by law number 12,796, 2013, the determination does not change in essence, i.e., it continued to admit as minimum training, "for the teaching exercise in early childhood education and in the first five (5) years of elementary education" a high school education. The new wording only changed the nomenclature, which previously referred to the first four grades of elementary school and now refers to the first five years, following the change that occurred at this level of education.

It is also necessary to remember that LDB’s (9394/96) §4, article 87, transitional provisions, determined that "Until the end of the Education Decade, only teachers with higher education qualifications or trained through in-service training will be admitted." (BRASIL, 1996). However, even though doubts remain as to what is meant by "graduated by in-service training," we may see that the determination to only hire teachers with higher education qualifications was not complied with, as it was revoked by law number 12,796/2013. (BRASIL, 2013)

In this sense, currently, although a large number of teachers in early childhood education and primary education already have a college degree, and the allegation of a shortage of trained personnel no longer holds up as something generalized, no legal provision prevents or hinders the hiring of teachers without such a degree in these basic education stages. Thus, the long decision delay that should have forbidden the hiring of teachers without higher education and the policy of expansion and (un)regulation of teacher education in Brazil, which tends toward a profession technicism, become convergent. The defense and valorization discourse of practical experience has become clearly functional to this reality.

Several studies in the teacher education area have dealt with light training and technicist or practice-focused trends. Some authors, as is the case of Cunha (2013), emphasize the importance of the so-called "epistemology of practice as the articulating axis of training." (p. 621), especially in a context in which theorizing is derived from the school’s concrete reality. But the author also admits this model identification "with an inconsequent criticism, easily criticized for the possibility of constituting itself apart from theory." [mainly] "In the current context, in which globalizing and economicist policies push for a massive and rapid training, this is a significant threat." (CUNHA, 2013, p. 621)

Regarding teacher education research field, we must highlight two issues raised by Zeichner (2009), the first is that studies on teacher education, although have had good evolution in recent decades, constitute a "relatively new field that draws on many different disciplines and responds to an evolving policy context." (p. 34) and the second takes us back to the fact "[...] that research on teacher education has had very little influence on policymaking and practice in teacher education courses." (ZEICHNER, 2009, p. 35)

Thus, particularly regarding the municipal education networks, considering the diverse realities that intersect teacher education (as well as hiring/action/evaluation), we emphasize that this is an open field for research and, above all, lacking approximations not only with the set of national and international studies already published, but also with the normative legal basis that guides educational policies.

We can notice that some initiatives in the scope of Brazilian educational policy in the last decade have been presented in order to give some answers to the question. They reveal advances and setbacks. Among others, we consider to be the case of decree 6,755, of January 29, 2009; of the National Education Plan (PNE), law number 13,005, of June 25, 2014; and of the resolutions: CNE/CP number 2, of July 1, 2015 and CNE/CP number. 2, of December 20, 2019, which institute the National Curricular Guidelines for Undergraduate Courses.

Regarding the decree number 6,755, of January 29, 2009, which establishes the National Policy for Teaching Professionals Training in Basic Education, we believe that its main advances are in the search to development of action articulation related to the countryside’s teacher training and to expand the federal government presence in this area. On the other hand, the initiative became limited by dealing only with in-service training or continuing education. As Gatti (2014, p. 34) observes, "[...] it is directed only to the professionals training already in service and to continued training, leaving untouched fundamental issues regarding the teachers’ initial training."

In the National Education Plan (PNE 2014), the first teacher training reference at a higher level takes place in Goal 1.8 and aims to "promote the initial and continuing training of early childhood education professionals, ensuring, progressively, the attendance by professionals with higher education. As it is seen, although important, since it does not ignore the need for such training for early childhood education teachers, this reference brings an indeterminacy that is "to guarantee progressively". There is, therefore, no deadline for this to be met and no obligation regarding this service.

In Goal 15, of the same PNE, the proposition is clearer and more determined, as it aims to ensure, within one year of the plan’s term, a national policy for the training of education professionals, "ensuring that all basic education teachers have specific higher education training, obtained in a degree course in the area of knowledge in which they work. (BRASIL, 2014) It is clear, therefore, that the referred "national policy" should ensure higher education. It is also understood in the statement that the established deadline of one year is not for all teachers to have higher education, but to establish the national policy.

The deadline for specific higher education training universalization, according to the determination contained in Goal 15 of the PNE (2014), comes to be understood as the decade’s end. Although we cannot rule out other interpretation possibilities, this understanding has been predominant. The evaluation cycles reports of the PNE already released, of 2016 and 2018, consider that the

Goal 15 of the National Education Plan (PNE) aims to ensure that all basic education teachers have specific higher education training, obtained in a degree course in the field of knowledge in which they work [...] (BRASIL, 2018, p. 253)

We must point out that the appropriate college-level education for teachers of early childhood education and the early years of elementary school, according to the understanding presented in the evaluation cycles reports, is a bachelor's degree with pedagogical complementation in pedagogy. The pedagogy course or another specific degree is not necessarily required. According to what is presented in the report, all over Brazil in 2016, 46.6% of the early childhood education teaching staff had teachers with higher education degrees appropriate to the field of knowledge they taught. In the early years of elementary education, this percentage rose to 59%. (BRASIL, 2018).

It is also noteworthy this same PNE (2014) commits to a curricular reform of undergraduate courses that seek to "ensure the focus on student learning" (GOAL 15.6) and also to "develop teacher training models for professional education that value the practical experience [...] through the provision [...] of courses aimed at complementation and didactic-pedagogical certification of experienced professionals” (GOAL 15.13). (BRASIL, 2014). These propositions, in our understanding, reveal contradictions of the referred plan. They open space for the argument that reduces the teaching work to practical skills, technical work, and the investment on training. They are possibilities that extend to the education networks in the sense of relativizing the commitment to be assumed with specific higher education, with the teacher’s scientific, academic, and intellectual preparation.

In the guidelines’ case, established by resolution CNE/CP number 2 of July 1, 2015, we must highlight that the final result of its preparation represented important mobilization and participation of several national actors. It was a proposal that sought to establish a reasonable agreement between different currents of thought, that took some steps in the direction of confronting the lightened formations of undergraduate courses and that sought more appropriate ways to address the traditional dichotomy between theory and practice. According to Hypolito (2019, p. 197) "It is a proposal that tries to solve an old impasse in training courses: align the increase of general workload with the increase of theoretical foundation hours and also the increase on practice hours, without training dichotomy."

It is also noteworthy that in the 2015 curriculum guideline, the academic organization of the university type, i.e., that works with teaching, research and extension, will gain some prominence. Here, even without prescribing that university institutions should be taken as a specific (or mandatory) place for teacher training, there is the recognition that higher education institutions that deal with this training should contemplate the tripod of academic training.

Article 4. The higher education institution that offers programs and courses of initial and continuing education to the teaching profession, respecting its academic organization, must contemplate, in its dynamics and structure, the articulation between teaching, research and extension to ensure effective standard of academic quality in the offered training, in line with the Institutional Development Plan (IDP), the Institutional Pedagogical Project (IPP) and the Course Pedagogical Project (PPC). (BRASIL, 2015)

However, even though we consider this article to be an important advance for the Brazilian reality, the caveat that accompanies the statement calls our attention: "respecting its academic organization". In our understanding, such distinction, which prevents the general application of the rule as a principle, ends up allowing what should be the exception to become the rule.

However, even though the resolution CNE/CP number 2, of July 1, 2015 has received "broad support from entities representing educators, translated into several manifestations favorable to its immediate term." (BAZZO AND SCHEIBE, 2019, p. 671), it was not effectively implemented. The political and conjunctural changes that took place in Brazil from 2016 on, with wide impact on public educational policies, favored consecutive and unjustified extensions in its implementation process. And, finally, in December 2019, new guidelines for teacher training are instituted, now under the Common National Curricular Base for Basic Education (BNCC) direction.

The new National Curriculum Guidelines for teacher training, resolution CNE/CP number 2, of December 20, 2019, in the wake of what was established in the BNCC, adopt the development of competencies as the main basis for the new training proposals. This logic, according to Duarte (2003), is along the same lines as the so-called "practice epistemology" and the "reflective teacher", which, according to the author, "doubly deny the act of teaching, that is, the transmission of school knowledge: they deny that this is the teacher's task as well as deny the teacher trainers task." (DUARTE, 2003, 620)

The sudden appearance of this new directive, with little or no dialogue with society, was not well accepted by organizations representing educators. The National Association for Training of Education Professionals (ANFOPE) manifested stating that "This 'new' resolution is another educational setback because it mischaracterizes teacher training affronting the National Common Base conception of teacher training courses, which indissolubly articulates the training and appreciation of education professionals, historically defended by ANFOPE." (ANFOPE, 2019b).

With the 2019 guidelines, the practitioner perspective gains more centrality in the national guidelines and actions for teacher training. This perspective adopts the school as the locus of training and practical experience as its main foundation. For Freitas (2020, p. 02),

In a total disassociation from the positions presented by educators in their entities [...] the CNE makes it clear that it is in tune with propositions of technical and practical nature, as they are exclusively referenced in the BNCC determinations for Basic Education, removing from the Universities the possibility of solidly constituted training in the field of educational and pedagogical sciences.

In addition, the author emphasizes the mercantilist character of this "new" training policy, which favors private institutions responsible today for the vast majority of undergraduate courses openings, and its distance from what would be required of a university education properly speaking. Thus, it is not a question of a new policy, but of the reinforcement or re-edition of the orientations that advanced in the 1990s Brazilian educational policy. In this case, "teacher training, moving from a training centered on theoretical, scientific, academic knowledge to a training centered on reflective practice, centered on reflection-in-action." (DUARTE, 2003, p. 619)

THE NORTH OF TOCANTINS STATE MUNICIPAL EDUCATION PLANS AND THE SPECIFIC HIGHER EDUCATION TRAINING

We will now evaluate the proposals of the municipalities in Tocantins countryside referring to teacher training in their education plans. We emphasize that, although municipal plans are important documents to know the local education reality, they do not always correspond well to what is lived or to the actions effectively carried out. In the same way, it is understood that the national and local political and economic conjuncture affects not only the way of doing things, but also the priorities and objective conditions of each reality.

Before dealing properly with the analysis of the municipal plans, we will make a brief presentation of the northern region of Tocantins State and the municipalities chosen. This region is located in the extreme north of the State and borders the States of Pará and Maranhão. Historically known as the ‘Bico do Papagaio’ Region, in allusion to its geographic shape delimited by the Tocantins and Araguaia rivers, the region gained notoriety for the repercussion of its agrarian conflicts in the 1980s and 1990s.

As one of the State’s micro-regions, the ‘Bico do Papagaio’ is composed by 25 municipalities and a population of approximately 200 thousand inhabitants. For the present research we chose the ten largest municipalities considering the number of inhabitants. This option favored the work because of the greater structure of school networks, the larger number of students, more resources and, consequently, greater possibilities for educational planning.

The municipalities chosen were: Araguatins (estimated population - 35,761 people), Augustinópolis (estimated population - 18,412 people), Ananás (estimated population - 9,549 people), Araguanã (estimated population - 5,729 people), Axixá (estimated population - 12,130 people), Itaguatins (estimated population - 5.864 people), Palmeiras do Tocantins (estimated population - 6,658 people), Praia Norte (estimated population - 8,432 people), São Bento do Tocantins (estimated population - 5,324 people), and Tocantinópolis (estimated population - 22,870 people) (IBGE, 2017).

The research conducted used only municipal education plans of the ten municipalities. They were prepared and published in compliance with article 8 of law 13,005 of July 25, 2014. In this case, such plans, elaborated or adapted within one year from the promulgation of the aforementioned law, should be "[...] carried out with broad participation of representatives of the educational community and civil society." (§ 2º). Therefore, they are public documents, with acts of enactment by the local executive power, which are available to researchers, educational community, and general population.

In the aforementioned plans study, considering the research objective of analyzing the commitment of the region's municipalities to specific higher education training, considering their actions based on the PNE, their own actions, and the perspective of valuing practical experience as an alternative for training, we limited ourselves to the evaluation of municipal goals and strategies that presented a direct correspondence with Goal 15 of the PNE (2014).

The goals composition analysis referring to teacher training in the municipalities led us to the following observation: of the ten plans analyzed, four do not make any changes in the wording of Goal 15 of the PNE (2014), being simply a copy of the National Plan; one repeated the same wording of Goal 15 adding only that it would "ensure adherence" to the national teacher training policy; one proposes to ensure training (initial and continued) under the terms of the legislation; two deal with ensuring that all teachers have specific higher education training, ensuring training or making partnership with the Union or State; and two establish deadlines or stages for 100% of teachers to have completed higher education.

It can be seen, therefore, that of the sample analyzed, two municipalities (20%) have a proactive stance, defining stages and deadlines, according to local reality, so that all teachers have a college degree. It is understood that this posture will favor community understanding and facilitate the goal monitoring by the subjects involved. In the other cases, there is little clarity in the proposals, or even a search to avoid future charges. These are formulations with little commitment from the local government and with generic aspects such as ensuring national policy adherence; ensuring teacher training under the legislation terms; ensuring that everyone has specific higher education training; or simply repeating the national goal wording.

The strategies analysis related to the goal that deals with teacher training in municipalities makes us identify three manifestations types that largely summarize the presence or the proposal of these federated entities for their teaching staff training: in the first manifestation type we gathered an initiative set that, present as strategies in the PNE (2014), demand some manifestation or local initiative; in the second type we identified own initiatives or propositions, originating from specificities or local needs; and in the third we found a set of manifestations, which even not demanding or not fitting an action by the municipalities, were assumed as local plans strategies reflecting what is set in the PNE (2014).

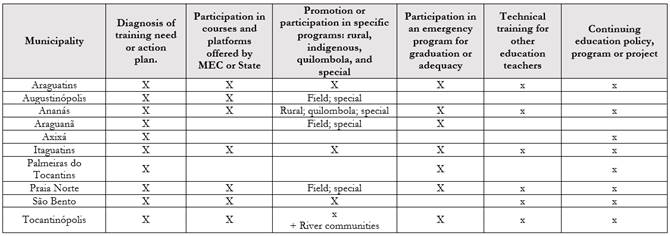

In the first case, based on national plan strategies, we related them to a set of six demands or initiatives that refer to an adherence or manifestation by the States or municipalities. The first demand we identified is assumed by all the analyzed plans; it deals with making a diagnosis of the training needs or developing an action plan. Therefore, it must be considered that each of the municipalities participating in the research, in compliance with what is determined in their own Municipal Education Plan (PME), has or should have a diagnosis or local action plan for training their teaching staff.

Regarding the other demands, as we can see in Chart 1, none of the municipalities analyzed had the adherence of all of them. Out of the ten studied plans, seven committed themselves to participating in courses and platforms offered by the MEC, as well as to emergency programs for graduation or adequacy of training; six reflected the commitment to promote technical training for education professionals other than teachers; and eight assumed the development of a continued training policy, program, or project, as well as the promotion or participation in specific teacher training programs: for rural, indigenous, ‘quilombola’, and special education. In this last case, besides the two municipalities that were silent on this demand, others referred only to teachers’ training for rural and special education. Specific training for indigenous teachers is present in four of ten municipal plans analyzed, and training for quilombola teachers in five. One municipality refers to specific training for river communities teachers.

Source: own preparation based on Municipal Education Plans in the North of Tocantins.

Chart 1 Approach on teacher training actions, contained in the PNE/Meta 15, which suggest greater possibilities for action in the municipalities.

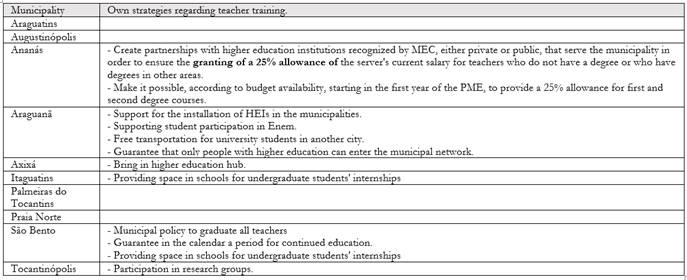

The second manifestations group analyzed in municipal plans of the Northern region of Tocatins State deals with initiatives for teacher training. In this case, as can be seen in Chart 2, six municipalities, or 60% of the analyzed plans, present some initiative that originates from local choices. As we can see, these actions such as support for internships for undergraduate students in municipal schools, the installation of Higher Education Institutions (HEI) or distance education centers (DE) in the municipality, funding for network teachers in training, support for university students in other cities, among others.

From this set of possible actions, which reveal some local protagonism in terms of teacher training, we consider that three of these initiatives are distinct or innovative in front of the set of proposals observed. They are also proposals that allow a closer relationship between teacher training and appreciation in local contexts. The first one refers to guaranteeing the entrance into the municipal network only with higher education, a strategy observed in the municipality of Araguanã. The second is the guarantee, in the school calendar, of a period for continued education, as proposed by the municipality of São Bento. And the third is the partnerships encouragement with higher education public institutions for the participation of education professionals in research centers, as foreseen in the plan of Tocantinópolis. Above all, "guaranteeing entry into the municipal network only with higher education" becomes a relevant measure for local reality. If it comes into effective, it can define parameters for hiring, valorization of university education, and make it possible to enter the teaching career with higher education from the beginning of one's professional life. It is unfortunate that this initiative was observed in only one of the plans analyzed.

Source: own preparation based on Municipal Education Plans in the North of Tocantins.

Chart 2 Teacher training actions of the municipality's own initiative.

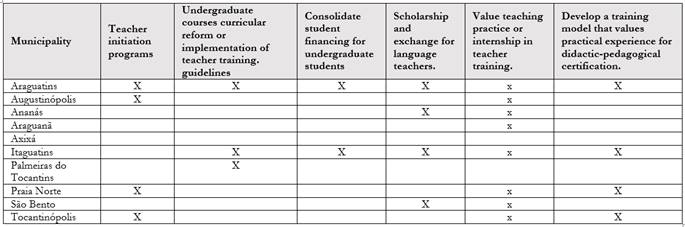

The analysis of the municipal plans led us to observe a third set of manifestations. These are propositions that, despite being part of the set of strategies in the PNE (2014), would not be directly imbricated in the attributions or intervention capacity of municipalities. In other words, they are initiatives within the national teacher training policy scope, in which the local government's capacity to participate is null or extremely limited.

In this sense, the strategies observed in the PMEs, in several cases, boil down to expressions of support, encouragement, dissemination or collaboration. These are, therefore, strategies of the PNE (2014) that refer to the federal government's own actions or, in some cases, shared with state governments. However, as we can see in Chart 3, several of these strategies became part of municipal plans, possibly revealing some local difficulty in understanding their own attributions or the interest in valuing or strengthening initiatives they deem relevant, even though they are largely outside their scope of action.

As we can see in Chart 3, four municipalities have manifested themselves in the sense of disseminating, supporting or encouraging a teaching initiation program; three deal with the curricular reform of undergraduate courses, and two with the consolidation of student financing for undergraduate students. We understand that these three activities are almost completely beyond the possibilities of the municipalities action. The adoption of these strategies in municipal plans is only a support formality, not contributing to the objectivity and clarity needed in relation to the initiatives that should synthesize the efforts of these federation entities. Since their proposition and execution are outside the scope of local decisions and initiatives, in the same way, it is not possible to hold them responsible for eventual non-compliance.

Source: own preparation based on Municipal Education Plans in the North of Tocantins.

Chart 3 Approach to teacher training actions contained in the PNE/Goal 15, which would not necessarily be the responsibility of the municipality.

In the case of language teachers scholarships and exchanges, which we found in four of the analyzed plans, we found that three of them refer to encouraging or stimulating the participation in programs created in other governmental spheres and one proposes to institute such a scholarship for its teachers. Therefore, the vast majority either have not expressed any opinion on this possibility or will limit themselves to federal or state government initiatives.

In the same chart we highlight two other manifestations that also remind us of limited possibilities of municipalities actions. However, in this case, we see not only a greater possibility of participation by the local government, but also another important motivation beyond the difficulties of local understanding of its role and possibilities. In a certain sense, we should reflect here that the hegemonic discourse, which has sought in teacher training (supposedly lacking in practical experience) the explanation for external evaluations failures, has been impacting local realities and had repercussions in municipal education plans.

Regarding teaching practices or internships in teacher training valorization, which is present in nine of the ten analyzed plans, and the development of a training model that values practical experience for didactic and pedagogical certification, which is present in four, one wonders about the real possibilities for municipalities to work with these issues. How would it be possible for the education networks in question, which are not responsible for higher education and have not participated in teacher training curricular decisions, to commit themselves to value practices or internships in teacher training? Likewise, in what way would it be possible for these federal entities to develop teacher training models that value practical experience for didactic and pedagogical certification?

In the teaching practices or teacher training internships valorization case, we can initially wonder about the competence of the municipal school system in this matter. But beyond that, if we make a greater comprehensive effort, we can assume something related to the hiring process. It would be the case that the competitions or selection processes would require proof of internships and teaching practices. However, such an association seems unlikely to us.

In relation to the development of models that value practical experience for didactic-pedagogical certification, in view of the issues considered above, we have here not only a very controversial proposition, but also one that is clearly in favor of technical primacy as the foundation of the teaching work, a trend in the current formatting process that has clearly gained space in the educational planning of several municipalities. Considering the municipal plans analyzed, if we rule out inattention or misunderstanding of the theme, there are 40% of those that intend to implement/adhere to didactic-pedagogical certification processes, based on the valorization of practical experience.

However, we should also ask ourselves about the significance of the adherence of the municipalities to these strategies. In these last two themes’ case, we are struck by their relationship with speeches favoring the flexibilization of specific university training for teaching. According to Feldfeber (2007), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and other international organizations seek to guide educational policies in order to attract, train, and retain the "best" teachers. Among the main recommendations, according to the author, is "To reinforce teachers’ knowledge and skills, which includes making their initial training more flexible, adapting it better to the school centers needs and reinforcing their professional perfectioning off their career" (FELDFEBER, 2007, p. 452).

The initial teacher education programs criticism as incapable of providing answers to the learning challenges, especially in the universalization of public schooling context, serves as "justification" for the reduction of public investments, the advance of private initiative, and the defense of the school as the teacher education privileged place. According to Diniz-Pereira (2015), research produced in different contexts of the Brazilian reality is used by conservative groups to relativize the importance of initial training in the teaching practice or the school transformation. According to the author, "These groups defend, therefore, the flexibilization and/or deregulation of the so-called "initial training" or, further, that it should be carried out in the shortest possible time, in higher education institutions less expensive than universities." (p. 146).

We should remember that this perspective gains support in the teacher training curriculum guideline 2019, resolution CNE/CP number 2, of December 20, 2019, (BRASIL, 2019), when it deals, in article 21, with pedagogical training for unlicensed graduates. In this article, besides a reduced workload of 760 hours, we verify the possibility of a training focused exclusively on practice. We also observe, in this provision, the absence of other important guidelines such as the form of regulation (evaluation) of the courses and the type of institutions that will be qualified to provide this training.

This trend was described by Saviani (2011, p. 13) when he defines the difference between technical teacher and educated teacher.

Now, the technical teacher is understood as one who is able to enter a classroom and, by applying conduct rules and the knowledge to be transmitted, be able to perform to the students' satisfaction. The educated teacher, on the other hand, is the one who masters the scientific and philosophical foundations that allow him to understand the development of humanity and, from there, carry out a profound work of formation of the students entrusted to him.

According to the author, governments have been committed to training technical teachers because this reduces costs and training time. In addition, we can add that the policy of making teachers' work more flexible (through precarious contracts and outsourcing), and of training teachers through rapid training, would contribute to making teaching even more of a transitional activity for people trained in any area. In this case, recent graduates could dedicate two or three years on a voluntary basis, with some scholarship or with a temporary contract in a school. According to Hypolito (2019), this model that seeks to deregulate teacher training is not incompatible with what the Common National Curriculum Base (BNCC) proposes. For the author, in this case, "teacher training done in university courses, based on teaching and research, is threatened and may be replaced by another, done in courses that are in fact light and cheap." (2019, p. 199)

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Regarding teachers’ specific higher education, even considering that this is a responsibility not attributed to the municipalities, they are the ones who will deal directly reality with the teaching work reality in the local education network. It is through this government sphere that not only several forms of teachers’ hiring pass, but also the evaluations and interests related to the career and remuneration in early childhood education and part of the elementary school. These are issues that involve the resources availability, the correlation of forces of the subjects involved, and the understanding of local public administration. The defense of a specific higher education for the entire teaching staff is linked to several political and conjunctural conditions.

The survey reveals quite clearly a number of weaknesses in local planning. These are situations in which it seems that the responsibilities for teacher training have not been properly understood, or in which there has been a deliberate attempt to dodge responsibilities. Proof of this is that part of the analyzed plans only repeats the wording of the national goal or, in some cases, it is a matter of generic formulations with little or no commitment. It is important to note that only two of the analyzed plans establish, in the wording of the corresponding target, the deadlines or stages for 100% of their teachers to have specific higher education training.

The research also stands out the clear difficulty regarding the local planning autonomy. Most of the surveyed municipalities did not present any action or strategy for teacher training that reflected their own actions. And even those that do present something not linked to the PNE strategies, in the vast majority of cases, lack a more relevant action to consolidate a teaching staff with higher education. It is important to point out that, among the municipal plans that presented some of their own initiatives for teacher training, only one will take a stance in the sense of hiring only teachers with higher education.

Finally, it can be seen that with different degrees of understanding, capacity for defense or critical evaluation, the municipalities reflect the national trends and contradictions in teacher training. This reality can be noticed (in the case of municipal education plans) even before the repercussions of the BNCC and the new teacher training guideline (resolution CNE/CP number 2, of December 20th, 2019). Thus, the trend that exalts practical training and the school as the locus of training, reducing the importance of intellectual/academic/university training, which is largely welcomed by municipal education plans. The low municipalities commitment to deadlines and stages for specific higher education training and the repercussion of strategies from the PNE (2014), which emphasized teaching practices in training or the appreciation of practical experience in pedagogical certification, confirm this assertion. It is understood that the lack of practices in teacher training discourse, serving as a justification for the results failure in external evaluations, has also contributed to hide the importance of other determinants, such as temporary contracts, the families’ socioeconomic conditions, and the teachers’ appreciation and working conditions.

REFERENCES

ANANÁS. Lei nº 502/2015, de 03 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação - PME e dá outras providências. Câmara Municipal de Ananás, 03/06/2015. [ Links ]

ANFOPE. A Anfope repudia a aprovação pelo CNE da Resolução que define as novas Diretrizes Curriculares para Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica e Institui a Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Formação), em sessão realizada no dia 07 de novembro, sem divulgação. Em um plenário esvaziado. [página online], 2019b.Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.anfope.org.br/anfope-repudia-a-aprovacao-pelo-cne-da-resolucao-quedefine- as-novas-diretrizes-curriculares-para-formacao-inicial-de-professores-da-educacao-basica-einstitui-a-base-nacional-comum-para-a-formacao-in/ . . Acessado em03/12/2019 [ Links ]

ARAGUANÃ. Lei nº 293/2015, de 01 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação de Araguanã e determina outras providências. Gabinete do Prefeito, 01 de junho de2015. [ Links ]

ARAGUATINS. Lei nº 1190/2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação, na conformidade do artigo 162 da Lei Orgânica do Município de Araguatins, Estado do Tocantins. Publicada no quadro de aviso da prefeitura em 23/06/2015 2015. [ Links ]

AUGUSTINÓPOIS. Lei 630/2015, de 22 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação para o decênio 2015-2025. Gabinete do Prefeito, 22 de junho de 2015. [ Links ]

AXIXÁ. Lei nº 469/2015, de 29 de maio de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação para o decênio 2015-2025 e dá outras providências. Gabinete do Prefeito, 29 de maio de2015. [ Links ]

BAZZO, Vera; SCHEIBE, Leda. De volta para o futuro...retrocessos na atual política de formação docente. Revista Retratos da Escola, Brasília, v. 13, n. 27, p. 669-684, set./dez. 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://retratosdaescola.emnuvens.com.br/rde Acesso em 07 de maio de 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL, IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2017| v4.3.51. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/to/tocantinopolis/panorama Acesso em11 de maio de 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 6.755, de 29 de janeiro de 2009. Institui a Política Nacional de Formação de Profissionais do Magistério da Educação Básica, disciplina a atuação da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Capes no fomento a programas de formação inicial e continuada, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 30 jan. 2009. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei 9.394/96. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Brasília: MEC, 1996. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, de 23.dez.1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 12.796, de 4 de abril de 2013. Altera a Lei no 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para dispor sobre a formação dos profissionais da educação e dar outras providências. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília, 5 de abril de2013. [ Links ]

BRASIL. PNE. Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação PNE e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília, 26 de junho de2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 1º de julho de 2015. Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação inicial em nível superior (cursos de licenciatura, cursos de formação pedagógica para graduados e cursos de segunda licenciatura) e para a formação continuada. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 2 de julho de2015- Seção 1 - pp. 8-12 [ Links ]

BRASIL. DECRETO-LEI Nº 1.190, DE 4 DE ABRIL DE 1939. Dá organização à Faculdade Nacional de Filosofia. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Decreto-Lei/1937-1946/Del1190.htm > Acesso em 14/04/2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Relatório do 2º Ciclo de Monitoramento das Metas do Plano Nacional de Educação - 2018. - Brasília, DF : Inep, 2018. Disponível em: <Disponível em: htpp://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/publicacoes >. Acesso em 23/04/2020 [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Relatório do 1º ciclo de monitoramento das Metas do PNE: biênio 2014-2016. - Brasília, DF : Inep, 2016. Disponível em:<Disponível em:htpp://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/publicacoes >. Acesso em 23/04/2020 [ Links ]

BRASIL. LEI Nº 452, DE 5 DE JULHO DE 1937. Organiza a Universidade do Brasil. Diário Oficial da União - Seção 1 - 10/7/1937, Página 14830. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/lei/1930-1939/lei-452-5-julho-1937-398060-publicacaooriginal-1-pl.html . Acesso em: 26/06/2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução CNE/CP Nº 2, de 20 dezembro de 2019. Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica e institui a Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Formação). Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 23 de dezembro2019. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Maria Isabel da. O tema da formação de professores: trajetórias e tendências do campo na pesquisa e na ação. Educação. Pesquisa., São Paulo, n. 3, p. 609-625, jul./set.2013. [ Links ]

CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil. A formação docente e a educação nacional. In: OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade. (org.). Reformas educacionais na América Latina e os trabalhadores docentes. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2003, p. 125-142. [ Links ]

DINIZ-PEREIRA, Júlio Emílio. Formação de professores, trabalho e saberes docentes. Trabalho & Educação, Belo Horizonte, v. 24, n.3, p.143-152, set-dez, 2015. [ Links ]

DUARTE, Newton. Conhecimento tácito e conhecimento escolar na formação do professor (Por Que Donald Schön não entendeu Luria) Educ. Soc., Campinas, vol. 24, n. 83, p. 601-625, agosto2003. [ Links ]

FELDFEBER, Myriam. La regulación de la formación y el trabajo docente: un análisis crítico de la “agenda educativa” en América Latina . Educ. Soc., Campinas, vol. 28, n. 99, p. 444-465, maio/ago.2007. Disponível em<http://www.cedes.unicamp.br> [ Links ]

FREITAS, Helena Costa Lopes de. CNE ignora entidades da área e aprova Parecer e Resolução sobre BNC da Formação. Revista Educar Mais, v. 4, n.º 1, 2020. [ Links ]

GATTI, Bernadete Angelina. Formação inicial de professores para a educação básica: pesquisas e políticas educacionais. Estudos de Avaliação Educacional. São Paulo, 25 (57), 24-54, jan./abr, 2014. [ Links ]

HYPOLITO, Álvaro Moreira. BNCC, Agenda Global e Formação Docente. Revista Retratos da Escola, Brasília, v. 13, n. 25, p. 187-201, jan./mai.2019. Disponível em: <http://www.esforce.org.br> [ Links ]

ITAGUATINS. Lei nº 189/2015, de 15 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação para o período de 2015-2025 e dá outras providências. Gabinete do Prefeito, 15 de junho de2015. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade. A reestruturação do trabalho docente: precarização e flexibilização. Educ. Soc., Campinas, vol. 25, n. 89, p. 1127-1144, Set./Dez. 2004. Disponível em <http://www.cedes.unicamp.br> [ Links ]

PALMEIRAS DO TOCANITINS. Lei nº 261/2015, de 17 de junho de 2015. Institui o PME - Plano Municipal de Educação no município de Palmeiras do Tocantins e dá outras providências. Gabinete do prefeito, 17 de junho de2015. [ Links ]

PRAIA NORTE. Lei nº 172/2015, de 24 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação e dá outras providências. Gabinete do Prefeito Municipal de Praia Norte, Estado do Tocantins, aos 24 dias do mês de junho de2015. [ Links ]

SÃO BENTO. Lei nº 245/2015, de 22 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre o Plano Municipal de Educação de São Bento e dá outras Providências. Publicado no quadro de aviso da prefeitura em 22 de junho de 2015. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Demerval. Formação de professores no Brasil: dilemas e perspectivas. Poíesis Pedagógica, Catalão, v.9, n.1 jan/jun. 2011; pp. 07-19. [ Links ]

TANURI, Leonor Maria. História da formação de professores. Revista Brasileira de Educação, núm. 14, p. 61-88, mai./ago, 2000. Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27501405 [ Links ]

TOCANTINÓPOLIS. Lei nº 963/2015, de 19 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação - PME e dá outras providências. Publicado na Secretaria de Administração e fixado em local de costume em 19 de junho de2015. [ Links ]

ZEICHNER, K. M. Uma agenda de pesquisa para a formação docente. Tradução: Cristina Antunes. Form. Doc., Belo Horizonte, v. 01, n. 01, p. 13-40, ago./dez.2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://formacaodocente.autenticaeditora.com.br Acesso em01/03/2016 [ Links ]

Received: August 08, 2020; Accepted: December 02, 2020

texto em

texto em