Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 03-Ago-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698228757

ARTICLE

CHALLENGES OF UNIVERSITY STUDENT PERMANENCE: A STUDY ABOUT THE TRAJECTORY OF STUDENTS ASSISTED BY STUDENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS

1Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo (TJSP). Limeira, SP, Brasil. <eliana.nae@gmail.com>

2Departamento de Saúde Coletiva (DeSCo) - Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM). Uberaba, MG, Brasil. <keipinezi@gmail.com>

This article discusses student permanence in Brazilian public higher education based on a study conducted at the Federal University of São Paulo. In the study, we sought to understand how a group of college students assisted by student assistance programs build their academic trajectory, considering their asymmetric socioeconomic background. This article analyzes part of the data from the in-depth interviews carried out in this research. It can be observed that the trajectory of students coming from social classes different from those that traditionally occupied the public university coexists with contradictions that make their permanence in the university a constant challenge. Elements of the material world, linked to financial subsistence, and symbolic, linked to the perception of belonging, indicate that the passage through the public university does not guarantee, in itself, changes in the way these students are perceived from the social "place", although these perceptions do not prevent students from overcoming the symbolic barriers of discrimination and exclusion and seeking ways to equalize the standard condition of the university student.

Keywords: student permanence; student assistance; public university

O presente artigo discute a permanência estudantil no ensino superior público brasileiro a partir de um estudo realizado na Universidade Federal de São Paulo. No estudo realizado, buscou-se compreender como um grupo de estudantes universitários atendidos por programas de assistência estudantil constrói sua trajetória acadêmica, considerando a origem socioeconômica assimétrica. Foi analisada, neste artigo, parte dos dados de entrevistas em profundidade realizadas nesta pesquisa. Observa-se que a trajetória de estudantes provenientes de classes sociais diferentes das que tradicionalmente ocuparam a universidade pública convive com contradições que tornam sua permanência na universidade um desafio constante. Elementos do mundo material, ligados à subsistência financeira, e simbólicos, ligados à percepção de pertencimento, indicam que a passagem pela universidade pública não garante, em si, mudanças na forma como esses estudantes são percebidos a partir do “lugar” social, embora essas percepções não impeçam que estudantes ultrapassem as barreiras simbólicas de discriminação e exclusão e busquem formas de equiparação à condição standart do estudante universitário.

Palavras-chave: permanência estudantil; assistência estudantil; universidade pública

El artículo analiza la permanencia de los estudiantes en la educación superior pública brasileña de un estudio realizado en la Universidad Federal de São Paulo. En el estúdio, buscamos comprender cómo un grupo de estudiantes universitarios asistidos por programas de asistencia estudiantil construyen su trayectoria académica, considerando el origen socioeconómico assimétrico. En este artículo se analizó parte de los datos de las entrevistas en profundidad realizadas en esta investigación. Se observa que la trayectoria de estudiantes de diferentes clases sociales que aquellos que tradicionalmente ocuparon la universidad pública coexiste con contradicciones que hacen la permanencia en la universidad sea un desafío constante. Elementos del mundo material, vinculados a la subsistencia financiera, y simbólicos, vinculados a la percepción de pertenencia, indican que el paso por la universidad pública no garantiza cambios en la forma en que estos estudiantes son percibidos desde el “lugar” social. Sin embargo, estas percepciones no impiden que los estudiantes superen las barreras simbólicas de discriminación y exclusión y busquen formas de equipararse con la condición padrón del estudiante universitario.

Palabras clave: permanencia estudantil; asistencia estudiantil; universidad pública

INTRODUCTION

The public Higher Education Policy in Brazil has traditionally been elitist and insufficient in relation to the demand for vacancies and the need for professional qualification of the population, besides having developed in a discontinuous process. According to Almeida (2017, p. 6), historically "the extension of schooling was marked by improvisation and precariousness, insufficient supply of vacancies, low educational achievement of those who managed to attend school, and restrictions to access according to the individual's social class belonging". However, in recent decades, starting in 2003, a counter-reform movement in education was proposed with the purpose of counteracting this historical process, combining political strategies in the field of higher education in Brazil, which can be observed by the following elements: expansion of public universities in the country, expansion of opportunities and openings, changes in the processes of evaluation and selection for admission to public universities, and financial support for the maintenance of students with trajectories of social vulnerability in the university.

These strategies have been put into practice in the last decade, especially from 2007 to 2012, with the increase of investments in public policies related to the expansion of vacancies in federal institutions of higher education, materialized in the Support Program for Restructuring and Expansion Plans of Federal Universities, known as REUNI, established in 2007 by Presidential Decree No. 6096.

In this program, a management contract was established for federal public universities with performance goals for receiving financial investments. Such propositions had the purpose of creating conditions for the expansion of access and permanence in federal public higher education, whose guidelines and goals foresaw, among other issues, the reduction of evasion and retention, besides the occupation of idle vacancies and the expansion of inclusion and student assistance policies, in order to promote the gradual elevation of graduation rates.

If the evaluation of the proposal's impacts is a historical task for the future, understanding the concrete unfoldings in terms of social insertion and the new requalification provided by the public university, some elements can be understood within the spectrum of incidents in this process. It is on elements of this process that this work focuses, with focus on the particular and collective elaboration about them that involves, therefore, social meanings and personal meanings and how this elaboration is indicative of mechanisms that can help reflect and understand the social condition in which these students are inserted.

This article exposes part of the results of a research about the permanence of popular students in the Brazilian public university. The specific objective was to understand how students from these strata built their university trajectory. This trajectory is constructed from the perspective of the senses and meanings attributed by students assisted by Student Assistance programs at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP).

These social processes were examined based on a qualitative research that comprised a successive approach to the issues surrounding student permanence in higher education. This approach was empirically undertaken by observing students in university spaces and by means of individual interviews with a group of 15 students assisted by the Student Assistance programs at UNIFESP. In order to have access to information with the specific quality that was sought after, i.e., debugged from a trajectory that had already been followed - and, therefore, with more experienced elements -, the decision was made to conduct interviews with students enrolled in their last year of the seven3 undergraduate courses existing at the Baixada Santista campus of the Federal University of São Paulo and served by the Student Assistance programs. The interviews were conducted between July 2015 and March 2016. The observation, on the other hand, was carried out continuously and systematically in the classroom between April and November 2015. The intention was, therefore, to build a panorama based on the experience of staying at the university and the relations with the student assistance policy based on the self-perception and self-declaration of these participants.

This choice was motivated by the idea that these students would already be able to evaluate their academic path through the various dimensions that have constituted their trajectory and attribute more clearly the meanings to the education process, as well as to the role of the Student Assistance policy in the course of their graduation. This could contribute to the discussions related to the academic path, with its variations and singularities experienced throughout the undergraduate years, which, as it was possible to verify, in fact happened.

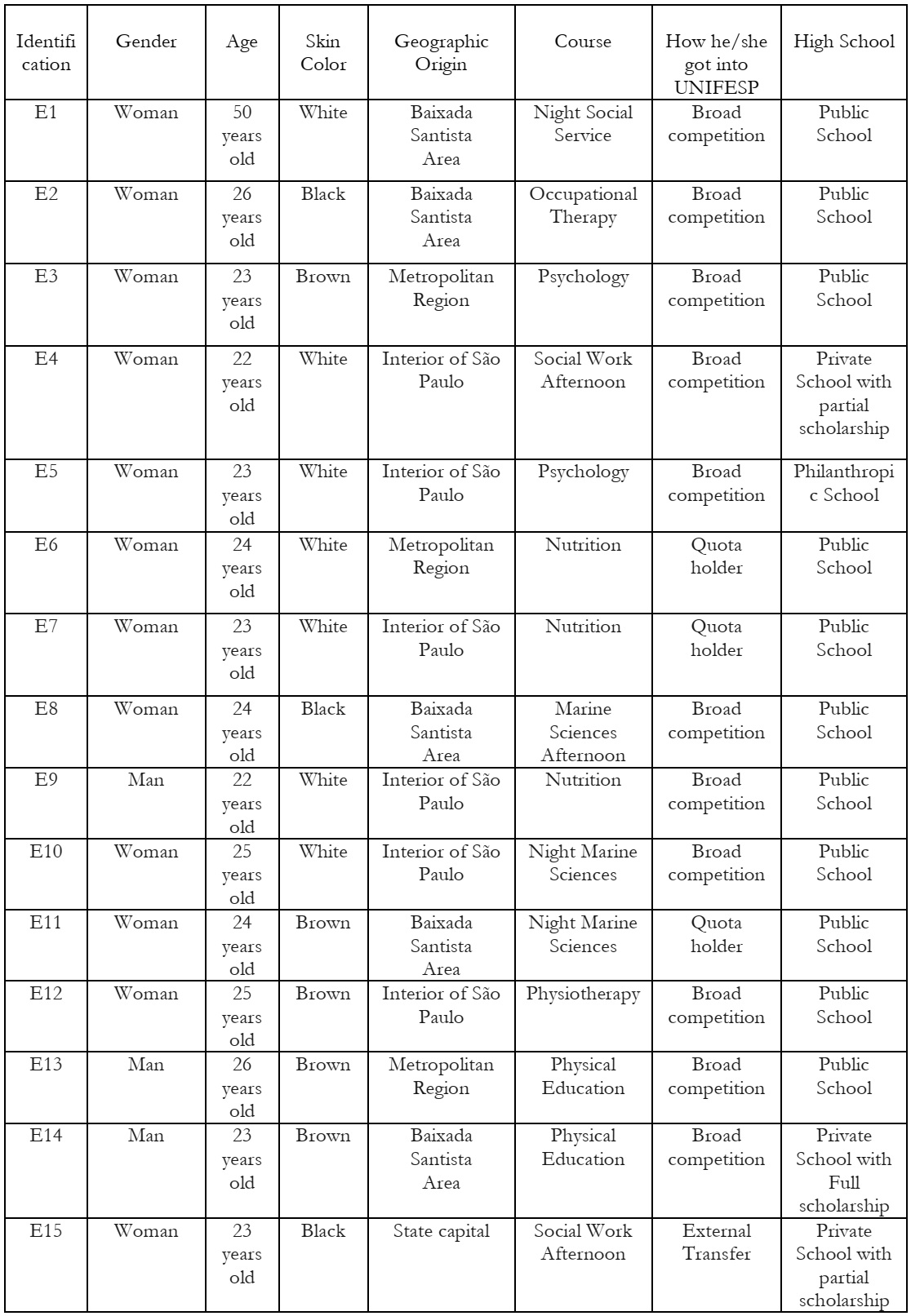

All participants were single and from the state of São Paulo; of these, 73% had attended high school in public educational institutions and only one (had children. The totality of the research participants makes up the first family generation to have access to higher education. At the time, although none of them had a regular paid job, 77% had a history of work prior to entering the university, and 60% declared themselves black or mulatto. As for the form of admission to the university, 80% did not enter through a quota system4. It is worth noting that most entered the university in the expected age range (NIEROTKA; TREVISOL, 2019), that is, between 18 and 24 years, which means that the group does not present a late entry into higher education.

In this text, our analysis is focused on part of the interviews conducted with the students presented in the tableabove.

To obtain the empirical material, a survey of the senses and meanings attributed to the academic trajectory by some of the assisted students, under the mediation of the Student Assistance policy, was built, which allowed access to the material and symbolic issues of this insertion and student permanence, enabling a reading about the limits and potentialities of the formal construction of the student assistance policy from the point of view of these same students. The narratives present in the discourse of the interviewees allowed us to approach dimensions that are not usually raised by quantitative data.

It is possible to say that this group of students is different from the traditional pattern of the so-called heirs (BOURDIEU; PASSERON, 2014), a social group for whom admission to university constitutes a habitus, in which the theme of university accompanies the family and school routine, as well as the relationship they have with knowledge and school products. These represent social segments that, until recently, had little circulation in the university environment. As Teixeira (2011, p. 46) points out, "getting into higher education is by no means something 'natural' for this group, unlike what is observed in the middle and intellectualized classes".

In view of this, entry into higher education shows a variation in the trajectory of this group, in a way that puts them in a different social position in relation to their parents and family. However, it should be emphasized, also according to Bourdieu (2007), that the university is a space where social inequality and segmentation still persist and can be visualized, since the sociocultural differences between groups are legitimized. This is the differentiation or social resource that Bourdieu (2007) entitled "cultural capital", a source of distinction and privilege among social segments, based on a distinctive family and school culture.

We recall that, according to Bourdieu, the school system is "one of the most effective factors of social conservation, because it provides the appearance of legitimacy to social inequalities, and sanctions the cultural heritage and social endowment treated as a natural gift" (BOURDIEU, 2007, p. 41). The ideology of personal merit, in this context, seeks to justify by the supposed commitment or individual qualities the contradiction between those who succeed and those who fail and, therefore, conceal "the mechanisms of elimination that act throughout the cursus" (BOURDIEU, 2007, p. 41), the real reasons for social inequalities also within universities.

UNIVERSITY TRAJECTORY AND EXPERIENCES

For the analysis of the interviews, we opted for the presentation in articulated axes that would allow the examination and interpretation of the narratives and reports in such a way that they could reconstruct the university trajectory of the students in question. A second level of analysis, which also affects the way the understanding of these processes was proposed, is linked to the observations made with the students in the university space. The students, in interviews, reconstructed their experiences as university students and recounted a large part of the situations that involved and involve their permanence in the university. On the other hand, some elements of student coexistence, which do not pass through the sieve of student discourse, could also be identified by the observations. Together, the two levels of data survey provided analytical conditions that allowed the constitution of two axes of analysis, namely: 1) material permanence; and 2) symbolic permanence.

It is known that the discussion about access/access to the university, especially the public university, is intrinsically linked to the issue of student permanence, especially in a context of diversification of the students' profile promoted by the expansion program of the Federal Institutions of Higher Education. Therefore, the category permanence has permeated this entire work and, consequently, presents itself as the main and indispensable axis of the analysis and will be the focus of the discussion to be presented. Despite the interrelation between admission and permanence, it is emphasized that the discussion in this article will focus on student permanence and not on admission.

Student permanence, as Santos (2009) emphasizes in his study about the trajectory of black students at the Federal University of Bahia, has two interrelated dimensions, namely: one defined as material and the other as symbolic, but both involve imbricated forms of existence of students inside the university. For clarification purposes, we called Material Permanence the one that involves the production of material life and Symbolic Permanence the one that encompasses the symbolic conditions, the social representations, in order to cohere with the perspective presented by Santos (2009).

The material permanence

At first sight, the financial condition is the first and determining obstacle that becomes evident to students from the lower social classes for the development of their undergraduate course, having been the most mentioned and problematized in the interviews and in the moments of observation. The concrete daily survival and the way of making it possible objectively permeates the entire academic trajectory of these students and, sometimes, can remove from the student the necessary concentration to respond to the studies. According to Portes (2006, p. 227), it is possible to say that

If the economic condition is not determinant of the actions and practices of the poor student - in a past and in a present -, it is a real, acting component, mobilizing feelings that commonly produce suffering in this type of student and threaten their permanence in the institution.

To meet their material needs, a student assistance program was institutionally created as one of the strategies and support to keep these students in the university space.

It is worth mentioning that, traditionally, UNIFESP did not have regular services and/or programs focused on student assistance before the consolidation of its university expansion project in 2010. Student assistance is a recent concern in the institutional scope, differently from what is observed in most Federal Education Institutions (IFES). It is materialized based on the National Program of Student Assistance (PNAES), from 2008, which assigns specific resources for all IFES to subsidize local permanence/student assistance programs.

This program is the main mechanism for the operationalization of the student assistance policy at UNIFESP and aims to create conditions for students in a situation of socioeconomic vulnerability to stay in school and take full advantage of their academic education.

Over the last few years, the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the Student Assistance program have been improved and other indicators besides income have been incorporated for the construction of vulnerability profiles in order to guarantee that the financial aid made available by the Student Assistance program would meet the needs of these students based on the principle of equality of conditions.

Aid is granted based on the degree of vulnerability identified in the global population of students who meet the per capita family income requirements of up to one and a half minimum wages. For the purpose of granting financial aid, socioeconomic vulnerability is conceived as a set of situations that may compromise the student's permanence at Unifesp (Federal University of São Paulo). Such situations may include absence or difficulty in accessing basic public goods and services and/or social rights. The proposed aid amounts related to the identified vulnerability levels have the following parameters as reference: profile V- R$160,00; profile IV- R$ 213,00; profile III- R$ 373,00; profile II- R$586,00; and profile I- R$ 746,00.

This financial support is structured as a crucial tool for entering college life, for continuing it, as well as for concluding the course chosen. In this regard, there was a consensus among all the interviewees regarding the importance and significance of the Student Assistance program for their material permanence at the university.

[…] So, I was a little afraid that I wouldn't be able to pay the rent, support myself and everything else. At UNIFESP, I managed to finish the course because if it wasn't for the scholarship, I wouldn't have finished the course, because I wouldn't have been able to afford to stay in Santos. (E6, Nutrition student, full-time, 25 years old).

[...] Because I think that if I did not have the aid, I would not be able to go to college even living in Santos. Because I really can't afford it. If I went to college and didn't have a scholarship, I would literally be screwed completely. Because I would have to walk back and forth. To eat, I don't even know how I would eat at college, because my father would have to work hard, my mother would also have to work hard. Of course, for those who have money it is easy, you come to another city and your father pays for everything and life goes on. But, in my condition, social assistance, the SSC (Student Support Center) helped me a lot, a lot, a lot. (E14, Student of Physical Education, full-time, 24 years old).

There was a recurring speech among all those interviewed about the concern with financial support, which demonstrates the situation of social vulnerability to which they are exposed and the dependence on a social program that enables them to occupy social spaces from which they are usually excluded, as is the case of the university. Specifically, the Student Assistance program is closely linked to the immediate material needs of these students, since it has been constituted as an alternative for minimizing the daily concern of guaranteeing the cost of housing, food, transportation, the acquisition of didactic material and other basic expenses for maintenance in the university space. However, as Portes (2001, p. 177) points out

In this case, it is not a bias of the researcher's look or a reduction of all the manifestations of the poor university student researched to a material condition. It is precisely the satisfaction of basic needs that can free this subject for other ventures constitutive of a good school education, the construction of identity and affirmation in the world, besides ensuring the school advantages that they all accumulated in an environment hostile to ventures of this nature.

As observed, the most immediate and possible way for these students to face material needs was to seek insertion in the Student Assistance program offered by the institution; it is noted that the institutional financial aid already appeared in the narratives as an initial subsistence plan even before they entered the university.

If I didn't have a scholarship, I wouldn't have... One of the key points, when I discovered the university; because I discovered the public university and what it would bring me, which was the permanence allowance. There are universities that have housing. So, I was counting on all this. Even at the time of the pre-university preparatory course people said: ah, but you are going so far away, how are you going to support yourself? Then I said: No, I'll stay at the university, it has this benefit. They said: But if you don't get in? But I: No, there's no way I won't get in, I need it. If I don't have it, I don't know how it will be. I was confident that I would have this benefit. (E12, Student of Physiotherapy, full-time, 25 years old).

I did a lot of research, I came here before, I tried to study how this reality was, but only because I knew that I would have (student) assistance and I would minimally be able to get a scholarship, because if I didn't, it would be unreal. I would go through this whole process and I would be sucking my thumb at home, upset because I wasn't going to come. Because you have no way of living, it doesn't exist. (E15, Social Work student, afternoon period, 23 years old).

For the group of students who had been working prior to entering the university and, consequently, still played the role of contributor and/or responsible for the household budget, the concern was even greater. The dilemma of reconciling the work activity that these students already had before entering university revealed itself as a significant issue and incompatible with the university trajectory in most of the cases observed, especially for those who sought undergraduate courses whose curricula require full-time dedication.

[...] in my high school... Second and third year, I worked. So, I worked and studied at night. So, I was taking school, I didn't fail any subject or year. We don't study as we should study, because I was tired, the whole day working and at night I went to school, so it was very complicated. So, when I saw that I lived this phase of my life that was work and study, I said to myself: "I won't be able to go. Because university is a much more serious thing, so I won't be able to do it. (E6, Nutrition student, full-time, 25 years old).

[...] at the time, as I was the income of my house practically, because I had worked in a supermarket for six years. And I had a very high position, so it was all like this: I was the one who bought the house. Most of the expenses at home were my own. And then I had to talk to my parents. There was no way. In the beginning it was very difficult. (E11, Marine Sciences student, night shift, 21 years old).

[...] I had passed a public contest and then I was in a dilemma: study or work? Study or work? Because I needed to help at home, but at the same time I needed to study. So, I tried during the first year to keep both together. I could stop on the weekends, but I could see that it was not enough. (E2, Occupational Therapy student, full time, 26 years old).

Researcher: And was it possible to reconcile the work day with the course?

E2: No, because I was always late for work. And it was still in Praia Grande. Which is far! My God! It was a long day, leaving here to go there. It would take me two hours to get there. And I would get in at three in the afternoon there to leave at eleven at night. But here I would leave at four o'clock in the afternoon, when I did. So much so that I got a failing grade because of this. I got a PD for attendance. Although I attended classes, I got attendance because I didn't sign the attendance lists. (E2, Occupational Therapy student, full-time, 26 years old).

In the narratives above, the restrictions that the daily work activity presented to these students' academic development pretensions were present, which would compromise the university experience in a full way. This situation constituted one more challenge for these students. It is worth pointing out that, in the universe of student workers interviewed, all of them, at some point in the course, either at the beginning or during the undergraduate course, had to decide between maintaining their work and staying at the university, given the impossibility of reconciling the two activities. For these students, quitting their jobs would mean making their family situation even more precarious. On the other hand, at this moment of definition, the role of the students' families was highlighted when they supported and gave symbolic support for this decision, even if the students in question played the role of providers and/or contributors to the domestic budget.

[...] And then, it was a very difficult decision. My parents helped me a lot. They said: "You have to study. So, if you have to quit your job, and we have to work two jobs for you to study, that's fine! No problem!" That's what I ended up doing. Although I spent a month martyring myself. What am I going to do? And now what? I have to work to help at home, and study too. I can't reconcile the two. I'll have to choose one. Either I work, or I study. But they (parents) said: "study! We'll manage to take care of the house, the bills, and if we need to help you at the university. I ended up leaving my job, I resigned. And I stayed here alone. (E2, Occupational Therapy student, full-time, 26 years old).

It was possible to see that, although there was no family tradition of access to higher education, the families of the students in question understood the university as a possibility for later obtaining better opportunities in the job market. There was an "educogenic" strategy (one that understands school or education as a fundamental strategy for social ascension). (SILVA, 2003), in which schooling occupied a significant portion of family concerns, aiming at building a project of professional ascension for their children; in this context, university education is seen as a strategy for social ascension. They understood that access to higher education would confer economic power and, consequently, income, which, in general, is directly related to schooling. As Santos (2009, p. 69) points out, formal education was the driving force for the changes in the living conditions of these families:

In the case of less well-off families, and in general black, the university represents a great achievement, since in their imaginary it was absent, distant, unlikely. The entrance of a member of these families into higher education and their permanence in it have two meanings: one that is individual and the other that is group, since being a university student means the possibility of changes in their future and in the social environment in which this individual circulates.

The possibility of not working and not having to contribute to the family budget thanks to the solidarity among family members would allow the student to invest in the continuity/progression of his schooling. This situation had direct repercussions on the better use and experience of the university space, but also on the symbolic dimension of the permanence of this student, since it would allow him to concentrate only on academic activities. It should be emphasized that the fact of being able to remain only studying and experiencing the university can have repercussions both on the quality in terms of education and on the time to complete the chosen course, thus contributing to the fact that the student with the analyzed profile can more easily complete his undergraduate degree in the minimum time required.

In the same line of discussion, other authors, such as Silva (2013), consider that the conditions of permanence in higher education have a direct relationship with how students organize and use the time available to them; that is, working and studying or just studying can have repercussions with regard to the participation of students in activities such as research, extension, scientific events, among others. That said, this circumstance portrays a new study-work relationship with qualitative repercussions in terms of the constitution of their university careers. In these cases, the assistance allows, even partially, the material subsistence and minimizes the need for family financial support. This means that, although the income from the student's labor activity is no longer part of the family budget, on the other hand, the access to student assistance resources makes possible the relative exemption of these families that, for the most part mainly for those who have their expenses increased by the fact that they can no longer live with their families, since the university campus is located in the metropolitan region of Baixada Santista, whose distance makes the daily commute to the family residence, usually located in other regions of the state, unfeasible.

It is known that in most cases the institutional financial aid is not enough to cover all the necessary material expenses, especially those that involve the expense of renting property, since the Baixada Santista campus is located in a metropolitan region with a high cost of living, often higher than that of the students' region of origin. This is a recurring issue that ends up being reflected in the daily university life of these students.

Good academic performance as a strategy for material permanence

It can also be observed that most participants in the research expressed a great commitment to the course chosen and to their education and, consequently, to their academic performance. A good income coefficient was also a symbolic and material permanence strategy, since, besides indicating a good use of the academic contents, it also enables better conditions to compete for and access academic scholarships5. The Nutrition student (E6) reports having used this expedient:

Whether you want it or not, the performance coefficient is a question that they (the faculty) evaluate too, right? So, I also wanted to be among the best in the class because I knew that this had some weight when we were looking for some kind of scholarship for scientific initiation or extension. And so, I kept on dedicating myself! And so far, I am satisfied. (E6, Nutrition student, full-time, 25 years old).

Thus, at the same time that they fulfilled the workload of complementary activities required by the curricular matrices of their courses, the students in question added points to their educational path and, finally, ensured an addition regarding the possibility of extraordinary resources to fund their material maintenance, a strategy in the same way pointed out by the Social Service student (E15):

[...] I started to dedicate myself. That's when I replaced my salary, which was the value of an (academic) scholarship, I worked like crazy to earn the scholarship value. If we are going to earn the same thing, let's do academic work that will really answer what I came to do and it's not making sense (referring to the quality of training outside the classroom, a differential of the public university in relation to the private university where she previously attended). (E15, Social Work student, afternoon period, 23 years old).

From this perspective, by engaging in para-academic activities, students stay longer at the university, and this becomes a device to appropriate "a more intellectually and institutionally complex world, to understand and make use of the intricacies surrounding the rules and their practices, to transit in a broader and more multiple universes of relationships, in meanings, values and conduct" (TEIXEIRA, 2011, p. 48). This interpretation is also explained by the Psychology student (S3) when evaluating the scope of welfare aid in relation to the prospects of claiming academic scholarships and subsidizing their stay at the university:

[...] But I only managed to do a good PIBIC6 project because I didn't have to work four years in the bar until two in the morning. So, it was a strategy that is not only mine. I built strategies directly and indirectly and that were also built here in this relationship, you know? And that ends up not being just a bank. There is no way. Every time I thought about the (welfare) assistance I received and explained it to someone, it came to my mind a lot. It's a help for me to stay. So, there is the concern that I stay. Let's stay and think how to do it. (E3, Psychology student, full-time, 23 years old).

Enjoying an academic scholarship has doubly stimulated the permanence of these students, since, at the same time that this reduces material concerns, it also provides an opportunity for full-time presence at the university and, consequently, a better appropriation of the academic culture. This condition, according to Almeida (2006), allows students to make fuller use of the services and possibilities offered by the university, bringing them closer to the condition of other students who are better off in socioeconomic terms.

The awarding of scholarships for monitoring, university extension, and/or scientific initiation is a relevant factor both in terms of the hierarchies established among the students and the distinction they imply in the curriculum, and also as university education. Moreover, students appropriate the university space, guaranteeing themselves an active insertion in this new environment, making it familiar and diverse. In Coulon's (2008, p. 42) perspective, these students become members, which "designates the natural domain of the group or its organization." According to Guesser (2003, p. 163), membership:

[...] is not only an entity that belongs to a certain group, but on the contrary, it is an entity that shares the social construction of that certain group. In other words, a member is an individual who dominates the group's common language, who interacts with others based on networks of meaning established in the interactional processes, who understands the social world in which he is inserted without great rational efforts, but only by the natural belonging of his socialization.

There is, therefore, a reconfiguration of the social space of the public university with the insertion of students from the lower social strata and coming from distinct life trajectories, in face of not only their socioeconomic reality, but also with regard to the symbolic capital distinct from the hegemonic groups that represented the university's clientele until then.

The symbolic permanence

In spite of the material conditions of existence already pointed out and that cover the axis of material permanence, it is deemed necessary to broaden the discussion beyond the analysis of economic and financial aspects that involve the trajectories of this new university public, in a symbolic perspective that considers the meanings, the interactions, the appropriation of university space and student affiliation. In Santos' (2009, p. 159) perspective, to remain symbolically requires "the individual's constancy in higher education that allows for its transformation, sharing with peers, and belonging to the university environment. Symbolic permanence involves effective integration into all aspects of academic life, transcending quantitative inclusion. However, this distinction between symbolic and material was made only for analysis purposes, since they are dimensions that go together and are interconnected.

As far as the symbolic permanence is concerned, situations of prejudice experienced, the subtle differentiations to which these students were submitted in the university daily life, and the strategies to overcome possible stigmas were addressed. In contrast to the conception of the construction of a symbolic permanence, we noticed the existence of explicit and non-explicit contents that indicate situations of prejudice of several orders, which were experienced and narrated by these students. There were countless perceptions of discrimination listed that deserved to be highlighted in the analysis.

The Social Service student (S1) calls attention to the teachers' statements about REUNI and the new student population entering public universities. In the discussions that took place in the collegiate body of the course, in which she was a student representative, this student captures the criticism of the probable decline in the quality of education, resulting from the process of expansion and diversification of the form of entry to the university, which allowed the entry of "unfit and unprepared" students to the academic path:

[...] A critic, I remember talk about REUNI, you know! I remember statements from female professors. And then, when I started to understand what REUNI was, I saw the criticism, where it was. Those who are having access to public universities, who no longer go... What is it? That it won't be of excellence because it has to meet the demand that is coming and the demand is from a bunch of assholes. And that made me angry! The disappointment started from there. Do you mean that I am part of this bunch of morons, who barely know how to write? Hold on, I'll show you something else! (E1, Social Service student, night shift, 51 years old).

We recall here the words of Coulon (2008, p. 68):

To say that 'they do not have a level' is like relocating the question of the manifestation of their habitus and, more than that, their possibility of intellectual affiliation to higher education. These students suffer a rupture that distances them, a little more, from what is required in higher education, in terms of vocabulary, conceptualization, reading and writing habits, thinking, in short, a set of intellectual operations that characterize the academic work.

It was also possible to perceive, in the speeches, that there is an expectation in relation to an idealized student. It is expected that the new student arrives "ready-made," loaded with desirable attributes to the academic environment, which makes students from popular groups feel "out of place, eternal debtors of the ideal, which, by the way, is rarely found in the halls of colleges and institutes" (ALMEIDA, 2006, p. 9). It can be noticed that this model of student that still remains in the imaginary of part of the academic community is the one that represents students who come from an elite that, until recently, exclusively occupied the public university space: white, male, aged between 18 and 20, urban dwellers, descendants of European immigrants, coming from a private high school and who would not have worked until then.

Along these lines, what was unprecedented was the report of another Social Work student (S15) - the only one among the interviewees who entered through an external transfer process, and not through the Unified Selection System (SISU). She brings in her narrative the experience of the "transfer" student, who enters at a different moment in the course and with a previous unequal academic trajectory. This is especially the case for those who come from private higher education institutions. She says that the university still doesn't know how to deal with this student profile or how to receive them. The student also emphatically mentions the prejudiced situations experienced when she identified herself as an external transfer student: "people turned their noses up at me.

I had the feeling that I had gone under the door, that is different, that is the difference when you come from transfer. When you come from transfer, people look at you with a great uncertainty, with a face like: we will see! So, this is very difficult, because besides accessing something that is rightfully yours, you have to keep proving to people that you have to be here. (E15, Social Service student, afternoon shift, 23 years old).

For this student, there is, in a tacit way, a message that indicates the view that the transfer student did not make an effort and entered the public university "under the door. Therefore, the student who entered through a method other than SISU has an unfavorable symbolic condition that puts into suspicion the right and legitimacy of studying in a public university.

The student (S15) also highlights the hierarchy of treatment that exists in relation to the institutions from which the "transferred" students came. For those who came from other federal universities or even from private but prestigious institutions, there was a respectability that was not offered to those who came from private institutions without tradition, or, as the student defined it, from "uni-scholars", so that there was a clear differentiation of treatment based on the institutional origin of the students.

Because he came from UFOP, from UFRJ, from other federal universities. Even from PUC, for example, which is private, but it is PUC! And then... How sensational! The professors say: let's introduce ourselves, you are new, I see you here. Your name is always strange on the list, that zone. Of course, everyone will know that you did not come from SISU. Ah, where did you come from? Everyone says. Then you are always in the same room with the other transfers because you have to take the same damn subjects. Ah, I came from UFRJ, I came from UFOP, I came from I don't know where... (the teachers say:) ah, that's great! I have a professor who is a friend there... And you? Ah, I came from UNINOVE. Oh, cool... So, such a book... I swear! I swear! Today I take it with a dose of humor. But it was scary. All (the teachers) were like that! All of them. "Ah, we'll see, won't we?" This "we'll see" is too much! Anyway, we are there, between the weak and the wounded. (E15, Social Service student, afternoon period, 23 years old).

We observe the predominance of a situation of veiled prejudice, which is not directly explicit and is often naturalized through discursive and cultural processes.

A similar issue was expressed by other students who entered through the process of reserve seats, read quotas7, and uttered situations in which they omitted their condition of quota holder. This behavior sought to avoid possible scenarios that could lead to discriminatory actions also associated with discussions about the logic of merit and its relationship with the supposed "quality" of the undergraduate courses - or, as Santos (2009) points out, because there is in common sense a negative association between student quota and competence/performance, despite studies and data to demystify this thesis. This is clear in the recurring silencing by the quota students in relation to the identification as such, which represents the feeling of not belonging and lack of legitimacy in relation to the university space. E6, when asked about her expectations regarding admission at the university, mentions the concern about not following the course mainly due to her condition of quota holder:

[...] sometimes we feel that because we are a quota student, from public school... Sometimes people have a prejudiced view: 'Oh, but the quality of education will drop'... And I have always tried to prove the opposite. Because we know that it may be so, but not just because the student came from public school. (E6, Nutrition student, full-time, 25 years old).

[It's even with the issue of quotas too. I never told people, for example, that I got in through the quota. Because there are people who do not agree. (E7, Nutrition student, full-time, 23 years old).

In the same perspective, the Marine Sciences student (E11) reported an episode experienced in class, in which a professor mentioned that she was against the presence of quota students at the university, as well as against the availability of research scholarships to Northeasterners, because, in her evaluation, these students did not know how to use these resources. The professor also justified that some researchers from the South and Southeast regions of the country were more "hard working", studied more and, therefore, deserved greater investments in relation to those from the other regions of the federation. According to the student's account, for the teacher in question, the quota holders were occupying the place of people who studied "for real".

This description only corroborates the evaluation made by Santos (2009, p. 165): "by doing so, these educators stereotype their students and place them in a situation of inferiority in relation to their colleagues. Thus, the figure of the teacher in this process is doubly central, since his actions can either weaken or collaborate positively to the symbolic and also effective permanence of the student in the university. Along these lines, the author adds that:

Stigma is an element in the list of obstacles faced by students in their attempt to stay in the university. The self-esteem of being a university student is antagonistic to the cases of exclusion and prejudice that these young people face in their academic trajectory. The very term "quota holders" is considered by many students (heard in our research) as pejorative and full of excluding signs (SANTOS, 2009, p. 16).

Such situations represent tensions and contrasts experienced in everyday university life. They show the constraints experienced by these students in the relationship with the professors and/or with other colleagues and also with the student model that refers to that coming from the elite and that occupied the public university benches almost exclusively - a model rooted in the imaginary of part of the professors. The interviewees' sensitivity to the pejorative comments about the relationship between the entrance of students from the lower social classes and the supposed decrease in the "quality" of the public university courses is perceptible, and its direct relationship to the logic of merit, since, for some educators, these students would have taken the place of other supposedly better prepared students. This situation is also evident in relation to transfer students from other universities, mostly those coming from less prestigious private institutions.

The feeling of having "come in under the door" (expression used by a student to refer to how students are labeled) represents feeling like an intruder, like the one who enters somewhere without having the right, without being invited or wanted (COULON, 2008). In this manner, this student is not raised to the condition of equal to the others in the sense of rights and, therefore, is not seen as worthy of the benefit of studying in a public university. Such a context configures, therefore, a situation of social humiliation that carries in itself repercussions from the point of view of the logic of exclusion, under a class perspective and in the student's intersubjective sphere. The entrance of these students in the public university, by itself, does not solve issues related to social exclusion, as Rhodes (2014, p. 37) highlights

[...] social inequality and prejudice would not, therefore, be eliminated through the expansion of opportunities or financial aid, because inequality is also characterized as a permanent threat to existence: a stereotypical place, which can prevent subjects from recreating themselves, transforming themselves.

Therefore, it is possible to say that the university is still organized as a space hostile to diversity and, consequently, as non-subsidiary to the symbolic permanence of the new social groups it is willing to serve - or, as Rhodes (2014) also points out, despite the discourses of democratization of higher education present in laws and decrees, exclusion within universities persists in the form of actions of prejudice and discrimination. Although there has been progress with the expansion of the possibility of access to public higher education and the consequent reduction of exclusion via restricted access, there is evidence that exclusion still takes place within the public higher education system.

However, contrary to what one might imagine, it can be noticed that the situations of prejudice experienced were constituted as a mobilizing force for these students to deconstruct the prejudices and the uncertainties about their presence and permanence in the university.

[...] I was not used to this frenetic rhythm of being all day long in college. Of having to study a lot! You have to dedicate yourself to it to the maximum. If you don't dedicate yourself, you won't succeed. Some people have it easier. In my case, I thought I needed to dedicate twice as much as I did. Because I didn't understand anything the professors said. And the university is like this: "turn around, my son!" (E2, Occupational Therapy student, full-time, 26 years old).

The need to prove good academic performance to be recognized and accepted was preponderant, which was consolidated as a strategy for these students to overcome the feeling or experience of prejudice experienced by the condition of being a quota holder and/or with deficient education in terms of previous education.

We can notice in E2's account that the language used, as can be seen by some terms present there, shows a certain distance from the language of the traditional university environment; that is, the cultural capital, concept elaborated by Bourdieu (2007), of these "new" students is not the same detected among the profile of students who commonly met and find themselves in this social space. This means another issue related to differentiation, but also a hindrance for the adaptation of these students in the new symbolic universe that represents the public university. However, as Almeida (2006) had already observed, although at first, they did not have the cultural repertoire valued in the academic environment, these students, despite the difficulties to take the course ahead, ended up developing dispositions such as determination, dedication, and proactive attitude, which boosted their university trajectories. It was possible to verify that there was an intense investment on the part of this group in favor of good academic performance and quality professional training, a strategy that would guarantee prestige and legitimacy before the other players in the academic community.

Comparative studies, as pointed out by Zimerman, Pinezi & Silva (2015), on quota holders and non-quota holders in public universities demonstrate this same situation in which initially there is great difficulty for quota holders to keep up with the pace of studies, presenting a lower performance than non-quota holders. However, generally between one and two years, the performance of quota students tends to be equal to that of non-quota students.

Still from the standpoint of symbolic permanence, the relationships and interactions that were designed throughout the observed academic trajectories called our attention, as opposed to the mentioned situations of discrimination. It is believed that these also had repercussions on the affiliation and belonging process of the students who participated in the research. This includes interpersonal relationships between students and professors, as well as the relationship or involvement with extracurricular activities that were frequently mentioned in the observed narratives.

Regarding the relationship with the faculty, there was a report from the Occupational Therapy student (S2), who highlighted the role played by two professors at the beginning of the course, a time when she had difficulty with the academic content, having to reconcile the undergraduate course with her work. These professors perceived his difficulties and offered him incentives and guidance for his studies. This, in her evaluation, was essential for her to remain at the university in a period of uncertainty and adversity, especially because the student, at that moment, was forced to reconcile her formal labor activity with her academic activities. Another Social Work student (E4) also mentions that her professors were careful with regard to the students' difficulties in relation to the course, showing themselves to be accessible to dialogue. The Nutrition student (E8) reports having always been encouraged by professors to continue studying and to develop research projects, and this contributed significantly to her student affiliation process. In the same vein, another Marine Sciences student (E10) reports having felt welcomed by the professors, and the university, for her, has become a familiar environment, despite all the infrastructure limitations existing in the newly created course.

[...] The teachers are always helping you, any of them. If you need equipment, a book, they will always help you. I don't know if it's because this course started out small, with few people, and then it grew. (E10, Marine Sciences student, afternoon period, 26 years old).

The role of pedagogical orientation and counseling also played by the professors was crucial when faced with the anguish and doubts in relation to the possibilities of action of the interdisciplinary baccalaureate, a new course modality and little known outside the academic environment.

For authors such as Tinto (1987 apudRHODES, 2014), the informal contact between teachers and students, beyond the mere formality of academic and intellectual work, contributes to the educational development and, consequently, to the affiliation process and the symbolic permanence of these students. Portes (2001, p. 208) points out that "the occupation of different university spaces, even if it happens slowly and gradually, as the subject feels more 'adapted', appears as an important element for sustaining the academic trajectory and the formation of identity of our young people". In this aspect, it was possible to observe that, among all the participants in this research, only one student reported not having been involved in research projects, extension and/or monitoring. All the others have had extra-classroom experiences, and some have also participated in academic mobility programs. As far as academic scholarships are concerned, with the exception of the aforementioned student, all the other interviewees had obtained scholarships for the activities and/or projects in which they had participated during their undergraduate studies. It is possible, therefore, to infer that, contrary to expectations, these students were able to respond to academic demands, having been recognized for their ability and commitment and, thus, constituted their processes of student affiliation.

On this, Machado (2011, p. 170) points out that:

In view of the discourses of democratization of federal institutions of higher education, which transformed the possible scenarios of enunciation, both of the students and of the other people who constitute them, at the same time that the hegemonic modes of production of identities are fragmented, by the very diversity that starts to compose this institution, the desires to consume a same mode of subjectivation, characterized by the young intellectual/professional, competitive and who proves their merits, are consolidated.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Upon reflecting on the process of restructuring and expansion experienced by the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) in the last ten years, more than the quantitative perspective, manifested in the increase in the offer of openings and courses, this work proposed a look at the new university public that has been present with more force in the academic space in the last decade and that, historically, was on the margins of higher education, especially in an institution that was traditionally constituted among the elite.

Beyond the statistical data on admittance and permanence, here the gaze was shifted to the daily life of these students, to the relationship with university activity, the financing of student life, material life, and their relations on a symbolic level in the university space. In short, we looked at the academic trajectory of a group of students in its several interfaces.

It is reinforced that, given the interest of this research to focus on the process of permanence in the public university of students from the lower social classes, the narratives of the students exposed here point out that their trajectory goes beyond the rupture and overcoming of barriers to entry, which demanded, on the part of these students, mechanisms of struggle against prejudices and limitations present in the university environment, as was pointed out in the analysis.

Far from pretending to give finished answers to the questions raised, the work was able to highlight "the emergence of unequal processes produced by the distinct experiences and utilization of the course according to the social classes to which individuals belong" (ALMEIDA, 2006, p. 4), as well as the social inequalities internal to the university, bringing the reflection on the possibilities of institutional intervention, with the aim of ending or mitigating this panorama.

The narratives of the students that could be known show successful trajectories, despite the several obstacles and mishaps experienced not only from a material point of view, but also from a symbolic one. These are students who did not carry, in Bourdieu's (2014) terms, the cultural capital valued and expected in the university environment, but built a capacity for autonomous and often solitary work in order to meet the daily academic demands and move towards the completion of their courses.

The analysis of the interviews also shows that the Student Assistance programs are fundamental for providing not only the permanence of students from popular social classes, by offering subsidies for the satisfaction of immediate material needs, but are also decisive for the very admission of these candidates. Besides this, these students, being less pressured by the struggle for material survival, can participate more actively in university life, which, in turn, enables them to get involved in academic projects, to build their identity in the academic environment, and to develop future endeavors in professional terms. As can be seen, the material and symbolic dimensions are juxtaposed.

On the symbolic level, one can see, through the narratives, that quota students and transfer students, especially coming from private institutions, express their perception of how differently they are treated by professors and by classmates. The discrimination suffered by these students is expressed in the words of professors and classmates, who classify quota students and transfer students from private institutions as the ones responsible for a supposed "drop in quality" in education. In turn, this discrimination has an impact on the opportunities for extracurricular activities, such as research, in which these students are often overlooked. Feelings of not belonging and lack of legitimacy appear unanimously in the narratives of these stigmatized students.

It should be emphasized that the process of student permanence goes beyond the guarantee of minimum conditions offered by the government, which only allows these new groups to attend courses. This premise could be corroborated through the interviews, some of which are analyzed here. In spite of the objective material issue as the first and relevant hindering factor, the permanence is a complex circumstance, since symbolic and immaterial issues are also as impeding to the academic paths as those related to university affiliation. Therefore, the effective permanence or the condition of university membership are linked to the relationships that the student will be able to establish inside the university, as already pointed out by Coulon (2008).

The propositions of Fraser (2002) about social justice are evoked here, which can also be thought of, in the scenario studied, as inclusion to mitigate social inequalities, in this case through education. Fraser points out that justice needs to be seen in a bifocal way, that is, through two different lenses at the same time, where one of them is justice referring to fair economic distribution and the other is the one linked to reciprocal recognition, in terms of identity and citizenship, in social spaces. It is agreed, as shown in this analysis, that if these two lenses or dimensions are taken in a watertight way, they do not lead to a full understanding of what social justice is and the possible ways to achieve it.

Therefore, the recognition and valuing of diversity, together with the transformation of the material or distributive structure, as Fraser proposes, can enable social spaces, such as the university, to be more plural, inclusive, and transformative. Student permanence, in this perspective, goes beyond the dimension of materiality, and is "like the act of continuing that allows not only the constancy of the individual, but also the possibility of existence with his peers" (SANTOS, 2009, p. 4), requiring, by extension, with regard to inequalities, both material redistribution and recognition of differences.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Wilson Mesquita. Desigualdades Educacionais. In: ZIMERMAN, Artur (Org.). Os ‘Brasis’ e suas Desigualdades. 1a. ed. São Bernardo do Campo: Editora da UFABC, 2017, p.03-26. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Wilson Mesquita. Esforço contínuo: Estudantes com desvantagens socioeconômicas e educacionais na USP. Dissertação (Mestrado em Sociologia). São Paulo: Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, 2006. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Escritos da Educação. 9. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2007. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre; PASSERON, Jean Claude. Os Herdeiros: os estudantes e a cultura. Florianópolis: Editora da UFSC, 2014. [ Links ]

COULON, Alain. A Condição de Estudante: a entrada na vida universitária. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2008. [ Links ]

FRASER, Nancy. A justiça social na globalização: Redistribuição, reconhecimento e participação. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, Coimbra, n. 63, p. 07-20, out. 2002. [ Links ]

GUESSER, Adauto Herculano. A etnometodologia e a análise da conversação e da fala. Revista Eletrônica dos Pós-Graduandos em Sociologia Política da UFSC, Florianópolis, v. 1, n. 1, p. 149-168, ago./dez. 2003. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/emtese . Acesso em:10 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Jardel Pelissari. Entre Frágeis e Durões: Efeitos da política de assistência estudantil nos modos de subjetivação dos estudantes da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Dissertação (Mestrado em Psicologia). Curitiba: Faculdade de Psicologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, 2011. [ Links ]

NIEROTKA, Rosileia L.; TREVISOL, Joviles V. Ações Afirmativas na Educação Superior: a experiência da Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul. Chapecó: Editora UFFS, 2019. [ Links ]

PORTES, Écio Antônio. Trajetórias escolares e vida acadêmica do estudante pobre da UFMG: um estudo a partir de cinco casos. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Belo Horizonte: Faculdade de Educação da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2001. [ Links ]

PORTES, Écio Antônio. Algumas dimensões culturais da trajetória de estudantes pobres no ensino superior público: o caso da UFMG. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, Brasília, v. 87, n. 216, p. 220-235, maio/ago. 2006. [ Links ]

RHODES, Carine de Almeida Arruda. Crônicas do Cotidiano Universitário: Um Estudo Sobre os Sentidos da Experiência da Graduação no Discurso de um Grupo de Acadêmicos da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Dissertação (Mestrado em Psicologia). Curitiba: Faculdade de Psicologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, 2014. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Dyane Brito Reis. Para além das cotas: A permanência de estudantes negros no e Ensino Superior como política de Ação Afirmativa. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Salvador: Faculdade de Educação da Universidade Federal da Bahia, 2009. [ Links ]

SILVA, Jailson de Souza e. Por que uns e não outros? Caminhada de jovens pobres para a universidade. Rio de Janeiro: Sete Letras, 2003. [ Links ]

SILVA, Paula Nascimento da. Do ensino básico ao superior: A ideologia como um dos obstáculos à democratização do acesso ao ensino superior público. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). São Paulo: Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, 2013. [ Links ]

TEIXEIRA, Ana Maria Freitas. Entre a Escola Pública e a Universidade: longa travessia para jovens de origem popular. In: SAMPAIO, Sônia Maria Rocha (Org.). Observatório da vida estudantil: primeiros estudos. Salvador: EDUFBA , 2011, p. 27-51. [ Links ]

ZIMERMAN, Artur; PINEZI, Ana Keila& SILVA, Sidney Jard. Success or failure of affirmative action in higher education in Brazil? The UFABC case. Revista InterSciencePlace, v. 10, n. 2, abril/jun. 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.interscienceplace.org/isp/index. php/isp/article/view/344/318 . Acesso em:10 nov. 2018 [ Links ]

3 The courses offered are: Physical Education, Physiotherapy, Nutrition, Psychology, Occupational Therapy, Social Work, Interdisciplinary Bachelor of Science and Technology with emphasis in Marine Sciences (BICTMAR). The first five are offered full-time, and the others, with classes in the afternoon and evening.

4At the time these students entered UNIFESP (2011-2012), the institution had implemented a vacancies reservation program (Resolution 23/2004), as an affirmative action. The offer of vacancies in undergraduate courses was increased by 10%, and these vacancies would be reserved for students who had attended high school entirely in public schools and for self-declared black, brown, or indigenous people.

5They include scholarships linked to university extension activities, scientific initiation, monitoring programs, tutorial education programs (PET) and institutional management incentive program (BIG/PRAE).

6The Institutional Scientific Initiation Scholarship Program (Brazilian Portuguese abbreviation PIBIC) aims to support the Scientific Initiation policy developed in Teaching and/or Research Institutions, by granting Scientific Initiation (IC) scholarships to undergraduate students integrated into scientific research. The IC scholarship quota is granted directly to the institutions, which are responsible for selecting the projects of the supervising researchers interested in participating in the Program. The students become fellows upon the recommendation of their supervisors.

7Between 2005 and 2012, the vacancy reservation policy instituted at UNIFESP increased by 10% the number of vacancies offered in its undergraduate courses, which were intended for students coming from public schools and self-declared black, mixed race, or indigenous students.

Received: July 24, 2019; Accepted: March 25, 2021

texto em

texto em