Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 17-Ago-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698231147

ARTIGO

SEXUAL EDUCATION: A TEACHING SEQUENCE FOR A YAE SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

1Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (UFU). Uberlândia, MG, Brasil. <daniellyferreira001@hotmail.com>

2Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (UFU). Uberlândia, MG, Brasil. <neusa.ensino@gmail.com>

This article is part of a pedagogical-intervention research developed in a master's course. The objective was to investigate sexuality conceptions of Youth and Adult Education (YAE) students during Science classes, as well as to propose a Didactic Sequence (DS) for Sexual Education (SE) in a school located in a settlement, in the rural area of Monte Alegre de Mina, a town in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Initially, we did a literature review on the Internet searching for: "sex education in YAE in settlement schools", "sex education in YAE and the Freirean approach", and for "gender and sexuality in settlement YAE". However, there were no results for this search. Thus, this research is justified due to the lack of discussions that align the triad YAE, SE, and settlement school. Data collection used questionnaires. The results present suggestions and possibilities for discussing sexuality themes, including gender, based on students’ experiences. It is suggested the development of DS adapted to the transversality of the sexuality themes and the reality of the students in the triad context of SE, YAE, and settlement school.

Keywords: sex education; sexuality; YAE; elementary school II; settlement school

Este artigo é parte de uma pesquisa de intervenção pedagógica desenvolvida em um curso de mestrado. O objetivo foi investigar as concepções de sexualidade de alunos(as) da Educação de Jovens e Adultos (EJA) durante as aulas de Ciências, bem como propor uma Sequência Didática (SD) para a realização da Educação Sexual (ES) em uma escola alocada em um assentamento, na zona rural do município de Monte Alegre de Minas/MG. Incialmente, foi realizada uma revisão da literatura em buscas na internet pelas expressões “educação sexual na EJA em escolas de assentamento”, “educação sexual na EJA e a abordagem freiriana” e por “gênero e sexualidade em EJA de assentamentos”. Porém, não houve resultados para esta busca, e a realização desta pesquisa justifica-se devido à ausência de discussões que alinham a tríade EJA, ES e escola de assentamento. A coleta de dados foi realizada por meio de um questionário. Os resultados apresentaram sugestões e possibilidades de discussão das temáticas da sexualidade, inclusive de gênero, a partir das vivências destes(as) alunos(as). Sugere-se a elaboração de uma SD que se adeque à transversalidade das temáticas da sexualidade e à realidade dos(as) estudantes no contexto da tríade ES, EJA e escola de assentamento.

Palavras-chave: educação sexual; sexualidade; EJA; Ensino Fundamental II; escola de assentamento

Este artículo es parte de una investigación de intervención pedagógica desarrollada en un curso de maestría. El objetivo fue investigar las concepciones de sexualidad de los estudiantes de Educación de Jóvenes y Adultos (EJA) durante las clases de Ciencias, así como proponer una Secuencia Didáctica (SD) para el logro de la Educación Sexual (ES) en una escuela asignada en un asentamiento, en la zona rural del municipio de Monte Alegre de Minas/MG. Inicialmente, se realizó una revisión de la literatura sobre búsquedas en Internet de las expresiones "educación sexual en EJA en escuelas de asentamiento", "educación sexual en EJA y el enfoque freiriano" y "género y sexualidad en EJA de asentamiento". Sin embargo, no hubo resultados para esta búsqueda y la realización de esta investigación se justifica debido a la ausencia de discusiones que alineen la tríada EJA, ES y la escuela de asentamiento. La recolección de datos se realizó mediante un cuestionario. Los resultados presentaron sugerencias y posibilidades para discutir los temas de sexualidad, incluso de género, basados en las experiencias de estos estudiantes. Se sugiere el desarrollo de SD que se adapte a la transversalidad de los temas de sexualidad y la realidad de los estudiantes en el contexto de la ES, EJA y la tríada de asentamiento escolar.

Palabras clave: educación sexual; sexualidad; EJA; escuela primaria II; asentamiento escolar

INTRODUCTION

This paper is part of a master's thesis research in Science and Mathematics Teaching at a Brazilian federal university. This study deals with the theme of Sexual Education (SE) for the final years of Elementary School (EF), in the Youth and Adult Education (YAE) modality, in the night shift, of a settlement school in the rural area, in the city of Monte Alegre de Minas/MG. Its objective was to propose and elaborate a Didactic Sequence (DS) for these students with the theme of sexuality, based on theoretical knowledge in the light of Freirian emancipation, which is based on dialogic and humanist education when considering the reality of (a) student.

When considering YAE as a space for dynamic experiences, permeated not only by one type of sexuality, but by several, coming from different subjects and experiences, between young people and adults with questions, controversial and missing situations that need to be discussed and reflected in the classrooms, what can we say, then, about the questioning of themes that permeate the sexuality of students from SE II classes, in the YAE modality, in a settlement school in the state public network in Minas Gerais?

In an attempt to satisfy such questions in this teaching modality, the opportunity to carry out the present research in Nature Science classes arose, considering that these subjects have knowledges learned in their daily lives, which are shared in the way of experiencing their bodies, educate their children and deal with the other culturally and socially. Such knowledge highlighted the need to develop a pedagogical material that considered the real needs of this social group, since there is no specific material that supports the particularity of this study.

The research was based on the theoretical references of Louro (2007; 2016) and Foucault (1988), among other authors such as Rael (2007), Weeks (2016) and Silva (2015; 2018), who address issues pertinent to sexuality and gender in education. The theme was also sought in educational documents, such as the Law of Guidelines and Bases for National Education - LDBEN - (BRASIL, 1996), and, with regard to Science Teaching, in the National Curriculum Parameters (PCN) - Cross-cutting Themes (BRASIL , 1998) and in the Common National Curriculum Base - BNCC - (BRASIL, 2016; 2017; 2018).

Likewise, the research was supported by authors who criticize these educational documents, such as Altmann (2001), Julião, Beiral and Ferrari (2017), Costa (2017), Machado (2017), Silva and Arantes (2017) and Souza Júnior (2018). In Freire (1987), the discussion of education for popular masses was sought regarding the Pedagogy of the Oppressed and the principles of education in the Social Movement of Rural Workers without Land (MST).

Regarding the thematic discussion of this study, a systematic and in-depth literature review was carried out at the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Education (ANPED) in the Working Group (WG) - 23 Gender, Sexuality and Education -, considering the expressions “sexual education in YAE in settlement schools”, “sexual education in YAE and the Freirian approach” and by “gender and sexuality in YAE in settlements”. However, there were no results for this search, motivating the present study, which aligns the triad YAE, SE and settlement school. Next, searches were conducted on the internet for the same expressions and the works of authors such as Prado and Reis (2012), Soares and Gastal (2012), Santiago (2014) and Zanatta et al. (2016) were found, with which we will dialogue.

The present research was submitted to the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Beings (CEP), of the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU), and approved on 10/23/2018, under the number 83997318.0.0000.5152.

SEXUAL EDUCATION AT SCHOOL

According to Louro (2016), sexuality, as a construction for all human beings, can be understood as the subject's social, sexual and gender identity shaped by social and cultural instances, which Foucault (1988) named “historical dispositive”.

Hence,

[...] it should not be conceived as a kind of nature's data that power is tempted to put in check, or as an obscure domain that knowledge would try, little by little, to unveil. Sexuality is the name that may be given to a historical dispositive: not the subterranean reality that is difficult to apprehend, but the great surface network in which the stimulation of bodies, the intensification of pleasures, the incitement to speech, the formation of knowledge, the reinforcement of controls and resistance, are linked to each other, according to some great strategies of knowledge and power (FOUCALT, 1988, p. 100).

Justifying the social, cultural and even political dimension, Louro (2016) argues that, although it is a common characteristic, sexuality is not a natural process experienced equally by bodies, since there is a plural condition that emerges from the collective, from a social construction, which is reflected throughout the citizen's life. For this author, regarding the naturalness of sexuality,

[...] when this ideia is accepted, it is meaningless to argue about its constructed character. Sexuality would be something “given” by nature, inherent to the human being. Such conception is usually anchored in the body and on the assumption that we all live our bodies, universally, in the same way. However, we may understand that sexuality involves rituals, languages, fantasies, representations, symbols, conventions... Deeply cultural and plural processes. In this perspective, there is nothing exclusively "natural" in this field, starting with the conception of body itself, or even nature (LOURO, 2016, p. 11).

In this context, sexuality is seen as a historical dispositive of social and cultural formation and intersects different environments, including religion, the media, family and school (BRASIL, 1998; RAEL, 2007; ZANATTA et al., 2016). Thus, the marks that are acquired by people in these social instances refer to everyday situations and experiences related to the construction of their social, sexual and gender identities (LOURO, 2016).

According to Louro, all these social spaces carry out the pedagogies of sexuality, that is, the "discipline of bodies" (LOURO, 2016, p. 17), which reiterate the identities and practices of the "desired norm" (LOURO, 2016, p. 18), which sometimes subordinates, sometimes denies or refuses other identities and practices considered divergent, alternative and contradictory - thus, in addition to social identities (race, nationality, class, etc.), sexual and gender identities are included here with unstable, historical and plural character. And, in the process of identity recognition, the attribution of differences with their cultural patterns is inscribed (LOURO, 2016).

In this context, the family in its Process of SE is an important factor in the building of sexuality knowledge, which is established by affective bonds of trust. It is the first social instance in which sex education occurs.; moral values, attitudes, religious beliefs and opinions are taught in (BRASIL, 1998). Even the family that does not speak, discuss or sexually educate their children is performing a SE that is silenced, through which family members understand that sexuality is a private and particular subject that does not deserve or should not be discussed or spoken. However, sexuality still exists and is present in the bodies of subjects who deny or silence it in their discourses, being, therefore, shared in social spaces and also modeled by the media (LOURO, 2016; WEEKS, 2016).

The media, in its several formats, conveys information attributed to the mold of values and behaviors passed on by the family, sometimes reinforcing shared knowledge, sometimes with new information, sometimes perpetuating prejudices (BRASIL, 1998). Even "cartoons, due to their circulation, constitute an important cultural artifact of the 21st century (...), conveying certain discourses about gender, sexuality, race." (RAEL, 2007, p. 160, 162).

The school, as an important social instance and space for experiences and formation of various types of sexuality, should enable the discussion and reflection of the knowledge, values and attitudes already established about sexuality (ZANATTA et al., 2016). Its function is to complement, inform, problematize and politicize the diversity of looks, and not to replace or underestimate the function of the family (BRASIL, 1998). In this perspective, Soares and Gastal (2012) state that science classes are an appropriate space for conducting SE crosswisely.

However, these spaces are not fixed places, but dynamic, flexible and plural environments, in which marks are acquired from the social relationships and interactions experienced there, and in which the referred pedagogies establish the "discipline of bodies".

Regarding the pedagogical discussion of SE in the school, it is legally supported by curricular documents: first, by the PCN since 1997, and currently by BNCC, approved in December 2017.

The PCN are educational guidelines that address all areas of knowledge and crosswise topics linked to them in an interdisciplinary way. Crosswise themes are daily relevant themes which permeate the student's reality and the different curricular disciplines, characterizing interdisciplinarity.

The pedagogical perspective of the work of SE adopted by the PCN is that students can experience "sexuality with pleasure and responsibility" (BRASIL, 1998, p. 311), being the sexuality one of the themes for health promotion referenced in this document.

However, Altmann (2001) points out flaws in the PCN when contemplating sexuality in school curricula. The author mentions that the pedagogical intervention of this crosswise theme aims at self-care and self-discipline of bodies through the modeling of behaviors, hygienist attitudes, preventive to STIs/AIDS, unwanted pregnancy, especially in adolescence and also curative, by providing a safe and pleasurable experience of sexuality related to health, not making a historical relationship for the deconstruction of gender discrimination and prejudice.

Although the document admits diverse manifestations of sexuality, it does not problematize the category of sexuality from the point of view of its historical constitution, in the same way as in relation to other categories, such as homosexuality and heterosexuality. (...) Defending sexuality as something related to pleasure and life does not say much and is not enough to unlink it from taboos and prejudices (ALTMANN, 2001, p. 581).

In line with Altmann (2001), Louro (2007) points out that, regarding the gender and sexuality discussion in school curricula, this still attributes an antireflexive view: the heterosexual norm establishes that the distancing from this pattern means becoming different, eccentric.

A singular notion of gender and sexuality has supported curricula and practices of our schools. Even if many ways of living genders and sexualities are admitted, there is consensus that the school institution has an obligation to guide its actions through a pattern: there is only one adequate, legitimate, normal mode of masculinity and femininity and a single healthy and normal form of sexuality, heterosexuality; moving away from this pattern means seeking the deviation, leaving the center, becoming eccentric (LOURO, 2007, p. 43-44).

Similarly, for Souza Junior (2018), the discussion of sexuality in PCN does not induce a pleasurable reflection or a pluralistic experience, but rather a solution for unwanted pregnancy among young people and contamination by the AIDS virus that the country experienced. For him, "the mentioned debates about sexuality had the effect of bringing them closer to ideas of risk and threat, due to the problems that society had been presenting, such as the growth of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, instead of providing paths to pleasure and life” (SOUZA JUNIOR, 2018, p. 19). Therefore, a “very relevant discussion for that time and now” (SILVA; ARANTES, 2017, p. 5).

Nowadays, the proposal of the PCN has been replaced by that of BNCC. BNCC is a document that emphasizes the national regulation of the different teaching modalities of Basic Education with the pedagogical purpose of an integral citizen formation, taking into account the local, social, regional and sociocultural characteristics of the school community (BRASIL, 2018), including for individuals who did not have the opportunity to complete their studies at an appropriate age with the school term (COSTA, 2017).

In its initial version, it considers "the approach to contemporary issues that affect human life on a local, regional and global scale, preferably transversally and integratively[...] highlighting themes such as sexuality, gender and cultural diversity" (BRASIL, p. 13-14, 2016b). However, in its latest version, approved in December 2017, BNCC excludes issues related to gender, leaving only a few issues related to sexuality, such as differences between biology, reproduction, contraception and preventive and curative measures (SOUZA JUNIOR, 2018).

Santos, Pereira and Soares (2018) warn that this reformulation by "suppressing these themes in BNCC reflects a conservative view, as a threat to the so-called 'traditional family', but above all it disconsiders the accumulation of debates, research and achievements of social movements in search of equity of rights." (SANTOS; PEREIRA, SOARES, 2018, p. 11).

For Souza Junior (2018), "there was a setback on the discussion about gender and sexualities (...) responding to the requests of the fundamentalist/traditional bench present at the National Congress" (SOUZA JUNIOR, 2018, p. 19), which demonstrates the plastering of the theme in curriculum documents.

Silva and Arantes (2017) discuss that, even though sex education is suppressed in the latest version of the BNCC, this document is the guide of school curricula at national level; thus, regional, cultural and social particularities should be considered, implicitly understanding that it is up to schools to include or not the discussions on the theme.

These same authors argue that "this discussion is necessary, since these themes were being viewed with a little more naturalness and seriousness and, if there is a withdrawal, the whole process built can generate a setback" (SILVA; ARANTES, 2017, p. 1).

In YAE modality, it is worth noting that both reference documents present the lack of common proposals regarding the specificity of sexuality themes, considering the presence of young people, adults and the elderly. Then, there is a need to think, reflect and empower educational practices in this model.

The lack of documentary contribution and discussion on how to work sexual diversity also affects the settlements' schools, whose proposal is based on the Freirian emancipatory pedagogy, which excels in dialogue, autonomy and the liberation of oppressive methods by considering the student's reality (ZANATTA et al. 2016).

Zanatta et al. (2016), when considering the reality of the settlement schools, believe the solution may lie in the adoption of a flexible teacher's posture based on dialogue, avoiding unilateral posture, authoritarianism and prejudice. In this scenario, the different approaches on how the sexuality theme may be discussed enable the sensitization and motivation of the student, provoking his interest and reflection of their behavior and, consequently, their possible interaction in activities, such as workshops, dynamics, discussions, etc., which provide and guarantee an understanding seen by another dimension.

Thus, the school is a privileged space for reflection and formation of the political and social awareness of students, since young people and adults have a baggage of knowledge (BRASIL, 1998; FREIRE, 1987). Therefore, the treatment of themes related to sexuality in YAE is necessary, because they are also educators of the other, contributing to personal, cultural, historical, social and political development.

EDUCATION OF YOUNG PEOPLE AND ADULTS AND THE DISCUSSION ABOUT SEXUALITY

YAE permeates all levels of Basic Education in the country, in a short time, from Literacy to High School, offering a free, nightly and adequate education to the student's conditions, in private and preferably public networks, ensuring their access and permanence in school. This teaching modality offers short-term studies "aimed at those who did not have access or continuity of studies in elementary and high school in their own age" (BRASIL, 1996, p. 15). For Julião, Beiral and Ferrari (2017),

With LDB, YAE is now conceived as a modality of Basic Education, which gives it a different dimension from the old one, since it allows the overcoming of the concept of a light, compensatory and superfluous offer of schooling. (JULIÃO, BEIRAL and FERRARI, 2017, p. 3).

Based on these authors, LDBEN is understood to attribute educational characteristics specific to the student in the teaching and learning process, according to their needs, interests and daily experiences, adding flexibility and quality to the teaching and, thus, ensuring the dialectic between education and citizenship, making the full development of the student.

As for YAE students, they are part of a specific and dynamic school group consisting of young people, adults and elderly. According to Prado and Reis (2012), Zanatta et al. (2016) and Costa (2017), usually all are workers in the search for better living conditions through studies, satisfied with the completion of elementary and high school.

However, Santiago (2014) warns that "YAE does not exist only to fill needs, it is a right of individuals who bring specific school trajectories and unique life histories" (SANTIAGO, 2014, p. 1). Thus, Silva (2015, 2018) argues that meeting the specificities of young people and adults is to deepen reflections of these subjects in the pedagogical proposals of YAE modality.

However, talking about YAE means talking about the subjects who demand this modality, contributing to the perception of education as a subjective right of all young, adults and elderly subjects, regardless of age, social class, gender, race/color, sexual condition, being a resident of the countryside, the periphery, villages or slums.

As for the reasons that led these subjects not to complete regular studies, Prado and Reis (2012), Zanatta et al. (2016) and Costa (2017) mention some: financial difficulties, maternity, non-reconciliation between time to study and time to work, lack of interest in classes, lack of motivation, learning difficulties and difficult access to school, etc.

However, it is undeniable that these subjects, even though they have not completed their studies, present different knowledge and experiences regarding the different identities that form and constitute the school space (COSTA, 2017). Such knowledge, many of them essential and inherent to life, such as themes related to sexuality, are ignored in YAE modality, impairing "the development of the autonomy of the subjects, their trajectories of empowerment and recognition of themselves" (COSTA, 2017, p. 2), in the return of this audience to the classrooms. When addressed, they refer only to a clinical dimension of the bodies treated in YAE textbooks, leaving aside the social and cultural dimensions of sexuality (ZANATTA et al. 2016).

By understanding the school as a sociocultural space (COSTA, 2017) and a space for interaction and formation of several subject identities (LOURO, 2016; WEEKS, 2016; COSTA, 2017), it is impossible not to discuss the transversality around the themes of sexuality, which, in turn, goes beyond the biological aspect.

Teachers are the ones with the approach and discussion of themes related to the need and experiences of the student, as well as the globalization of relevant issues of the present day, including social movements. Thus, it is understood that discussions about sexuality and gender in school spaces are supported through didactic activities performed by teachers. According to Barreiro and Martins (2016), these debates become an important educational measure for the construction of knowledge. In this context, Julião, Beiral and Ferrari (2017) add that "to consider the full development of the person is to make him/her realize that sociocultural belonging is built together with school assumptions articulated with their longings and experiences" (JULIÃO; BEIRAL; FERRARI, 2017).

SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

Settlement schools, different from traditional rural schools, arise in the context of conquering education, which gives greater guarantee and stability in the struggle for land tenure. When incorporated into the public school system, that is, when they become regularized, these schools are now named Countryside Schools (EC) (MEIRELLES; SALLA, 2014).

The school claimed by social movements seeks the promotion and guarantee of social rights of a significant portion of the society which has historically been excluded from fully exercising its citizenship. The CE arises in opposition to the capitalist educational logic (MOLINA; Sa, 2012).

For Machado (2017), LDBEN, although emerges in the context of the democratization of the country's education and guides the elaboration of a pedagogical proposal, does not relate with pedagogical practices considering the adaptations of place, region, peoples, etc. In fact, it promotes a standardization, removing the individual capacities and potentialities from the students, resulting in a standard education system.

Thus, the CE allocated in agrarian reform settlements and linked to the MST have their pedagogical political proposals based on Freire's pedagogy, through which dialogue is the instrument for knowledge, autonomy and praxis. In this perspective, the main contribution of the Freirian approach comes from Pedagogy of the Oppressed, whose humanistic and liberating conception contributes to the social transformation of the oppressed subject before the reflection of the oppressive factors to which he was imposed, providing a critical and ethical reflection of its reality (MST, 2006).

Therefore, pedagogical practices must begin from the interest, need and knowledge of the countryside student from his trajectory of struggle for social space, so that he is able to understand his reality and social transformation. Yet, CS are social spaces of active participation, research, action and reflection, theory and practice, teaching and research (ZANATTA et al., 2016).

However, the school located in Roseli Nunes III settlement is an extension of a state public school and, therefore, it is not yet recognized as CS, since it does not have its own Pedagogical Political Project (PPP), education professionals are not trained for the reality of the countryside and, in this social space, the local reality of the students is not taken into account.

METHODOLOGY

The present research, in the form of pedagogical intervention, involves "the planning and implementation of interferences (changes, innovations) - aimed at producing advances, improvements, in the learning processes of the subjects who participate in them - and the subsequent evaluation of the effects of these interferences." (DAMIANI et al., 2013, p. 58).

For Damiani et al. (2013), pedagogical intervention assumes a qualitative character because it is governed by principles, procedures and criteria, whose "intention is to describe in detail the procedures performed, evaluating them and producing plausible explanations about their effects based on the relevant data and theories" (DAMIANI et al., 2013, p. 59).

Also according to the author, pedagogical interventions are applied researches that aim to contribute to the resolution of practical problems. In this context, according to Fachin (2006) and Bell (2008), the questionnaires can be used as auxiliary research instruments applied at the beginning and end of the investigation.

In line with Fachin (2006), Bell (2008) and Damiani (2013), Martins (2006) and Carvalho (2006) point out the research methodology emerges from the questions to be solved and the questionnaires are only a data collection instrument that aim to raise topics to be solved through dialogue. Therefore, discursive interactions in the teaching and learning process, in their historical and social context, are believed to bring with them reflections and new perspectives to the known problem (MARTINS, 2006).

After the authorization of the school board for participation in the research, the target audience of this study became aware of this initiative through the research professor, in the classes of Natural Sciences. For students, the Free and Informed Consent Form (TCLE) was made available, based on resolutions no. 466/12 and No. 510/16, recommended by the National Research Ethics Commission (CONEP) of the National Health Council (CNS) belonging to the Ministry of Health (MS).

The methodology had two phases: application of a questionnaire and elaboration of the Didactic Sequence (DS). In the first phase, the questionnaire sought to characterize the research subjects according to age, religion, sex, color, etc., and also in relation to their conceptions about sexuality, how they acquired information and what questions or curiosities they had about the subject. This information helped to make up the next phase of elaboration of the activities, considering the nature of the experiences in the rural area, their needs and topics of interest.

The questionnaire was elaborated and developed by the researcher after completed reading on the subject and on the methodology for preparing questionnaires described by Bell (2008), containing open questions and in the form of lists (with options to mark). Data collection occurred through the applied questionnaires, considered by Fachin (2006) and Bell (2008) as data instruments, one applied at the beginning of the investigation.

Data analysis occurred through properly coded questionnaires. Each participant was identified by an Arabic numbering, gender and period he attended to YAE, i.e., Q1F, 1st YAE; Q2F, 2nd YAE; and, thus, successively, ensuring the anonymity of the participant.

After the coding of questionnaires, the answers of the participants were transcribed and organized according to the identification in ascending order of each participant. It is worth noting that, after the transcription of the data, the questionnaires were discarded, ensuring confidentiality. With the performed analysis, the thematic possibilities to be addressed in the activities for DS emerged.

The second phase had the planning of a systematic DS in based on theoretical references, whose purpose was to work on themes and meet the suggestions given by the students.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Profile of YAE students in the settlement school

All 26 students from the settlement school agreed to participate in the research. Of this group, one student belonged to the 1st Period, six students to the 2nd Period, eight students to the 3rd Period and 11 students belonged to the 4th Period of the YAE modality, with ages between 27 and 82 years old, eight male and 18 female.

According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the classification of the population by age groups follows: individuals between 0 and 19 years old are considered young; subjects from 20 to 59 years old are considered adults; and people who are 60 years old or more are considered elderly (IBGE, 2010). Therefore, the participants were grouped into two of the IBGE age classification categories. Two students were considered elderly, and the others, representing the majority, fit the classification of adults.

Of the subjects surveyed, 20 were part of the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), and their lots/agricultural properties were installed in the settlement named Roseli Nunes III; and six belonged to Banco da Terra, both land organizations of the governmental program of agrarian reform.

All people surveyed were of Brazilian origin, although they came from different regional locations in the country, and have attended school at some previous stage of their lives - in childhood, adolescence or youth. They had different marital status, varying in greater numbers among married people (10); stable union (6); single (6); divorced (2); and widows (2). Thus, they also diverged regarding religion, being represented, respectively, by evangelicals (11); Catholics (10); spiritists (4); and no belief (1). Regarding skin color, they declared themselves as white (12); brown (8); and blacks (6). As for the profession, most were rural producers (24), due to their settler condition; and others were local artisan (1) and mason (1).

The exploratory investigation regarding the profile of young people and adults was in line with the work of Prado and Reis (2012) and Silva (2015): all the subjects surveyed were workers, diversified in terms of religious beliefs; they immigrated from different locations, performed different activities and even shared the daily work routine with night studies.

Hence the importance of YAE's education professionals to recognize the uniqueness of each student, considering their life experiences in the teaching-learning process, in the delivery of programmatic or complementary content, that have assimilation and meaning in life of that student bribed by a dominant society (FREIRE, 1987). Among these contents, the themes of sexuality were present as an inherent attribute of each subject, considering their cultural and social background.

In this context, Silva (2018), in his study on Sexual Diversity in Youth and Adult Education (YAE), emphasizes that

[...] recognizing the subjects' specificities means legitimizing the personal, cultural and social characteristics, as well as the desires, dreams, expectations and subjectivities of each student. It means listening to them about their individualities and, mainly, considering differences, including sexual orientation and gender identities (SILVA, 2018, p. 1).

According to Prado and Reis (2012) and Silva (2015, 2018), Damiani et al. (2013) point out that qualitative research goes beyond the identification of characteristics, providing a view of the problem, which was obtained thanks to the exploration of its particularities. Such variables, present in the subjects' existence, allow the approach of themes with scientific foundations, which give meaning to everyday and distinct knowledge of this group of students.

Conceptions about sexuality

When introducing future discussions in the design of higher education activities, these began with the open-ended question What do you know about sexuality? According to the answers, it was possible to define sexuality as a concept present in the knowledge of these students. Below, some conceptions of sexuality are highlighted.

It's sex (carnal pleasure). (Q2F, 2nd YAE)

I know about transsexuality, because of that soap opera where the girl turns into a boy. (Q4M, 2nd YAE)

I think man with man is not normal, but we can't disagree either, because they like it. (Q7F, 2nd YAE)

It is whether one is female or male. (Q8F, 3rd YAE)

Sexuality is a particularity, each person has the sex with which she is identified. (Q20M, 4th YAE)

I know that the behavior has to be prevented. (Q23F, 4th YAE)

It's sex, behavior, type of clothing, posture, but I can't explain it by writing. (Q25F, 4th YAE)

All participants were able to say what sexuality is, in the way they experienced and experience it. In addition, the reflexes of the sexual education of each of the subjects are felt in social interactions, such as at school, for example.

According to the students' records, it was possible to highlight that the conceptions of sexuality expressed two main highlights: sex for obtaining pleasure from the body through the satisfaction of erotic desire; and gender in the different ways of being a man and being a woman, which was associated with sexual orientation, labeling of behavior and embodiment of the genitals.

Sexuality, considered synonymous of sex, just for carnal pleasure, of the sexual act itself, of intercourse, goes back to the biologist and reproductive character. However, sex, as stated by Foucault (1988), is only an attribute of sexuality. Gender, in turn, opens a discussion on the comparison with the normality patterns seen between men and women, a normality that is stereotyped by society and linked to respect, sexual diversity and power relations.

For Foucault (1988), sexuality should be the principle for opening the discussion on power relations, being flexible and articulated in social dialogues.

Sexuality should not be described as a rebellious urge, alien by nature and unruly by necessity, to a power which, in turn, runs out of steam in its attempt to subdue it and often fails to dominate it entirely. It appears more as a particularly dense crossing point through power relations; between men and women, between young and old, between parents and children, between educators and students, between priests and lay people, between administration and population. In power relations, sexuality is not the most rigid element, but one of those endowed with the greatest instrumentality: it can be used in the greatest number of maneuvers, and can serve as a point of support, of articulation to the most varied strategies (FOUCAULT, 1988, p. 98).

For Louro (2016), sexual and gender identities are affirmed or silenced by the most different social instances, among them, the family, religion, media and school, legitimizing some and repressing others, exercising what this author names as pedagogies of sexuality.

In this sense, "all these instances carry out a pedagogy, make an investment that often appears in an articulated way, reiterating hegemonic identities and practices while subordinating, denying or refusing other identities and practices" (LOURO, 2016, p. 25). Thus, the school, as an instance that dictates its pedagogies of sexuality, should be a place of knowledge, reflection and not a place of concealment of knowledge and restriction.

Therefore, each respondent carries their own concepts about what sexuality is to the detriment of their experiences. Hence the importance of appropriately adding information to this existing knowledge in the deconstruction of stereotypes and taboos for the promotion of knowledge and autonomy of students.

Sources of information on sexuality

Among the instances in which the participants acquire information about sexuality, they stated they aggregate such knowledge in television programs (20.5%), such as movies, soap operas, etc., followed by the family (17, 9%), circles of friends (16.7%), magazines (15.4%) and the internet (15.4%), as well as through other means of information dissemination, such as school (12.8%) and, finally, religion (1.3%).

It is evident how the television media influences the formation of self-knowledge in relation to even the family, in which sex education should be a reason for dialogue and understanding. “The media, in its multiple manifestations, and with great force, assumes an important role, helping to shape views and behaviors” (BRASIL, 1998, p. 292), although it also informs, moralizes and reinforces stereotypes, in the same way as school, family and religion do.

Therefore, the importance of the school is highlighted, indicated as the fifth social instance for the formation of students' knowledge, based on their experiences and knowledge conditions. It is up to the school to work with respect for differences, dialogue about beliefs, taboos and myths; to stimulate the discussion of values associated with sexuality, without judging or violating the behavior of students and the patterns of sexual education that each family offers to their children (BRASIL, 1998).

In this context, it is up to YAE, considering the specificities and experiences of its students, to share common sense knowledge with clarifying and reflective information, avoiding possible normalizing judgments conceived and passed on in society as a whole - not failing to state that the family is the social instance in charge of the sexual education of their children, with the school facing the possibilities of discussing different views of sexuality (BRASIL, 1998).

As already stated by Louro (2016), there are many social instances that carry out the so-called pedagogy of sexuality, including religion, a social instance that dictates norms and regulates bodies through their beliefs.

Questions and interests about sexuality

At the end of the questionnaires, the students registered their arguments, questions and suggestions for themes to be worked on, which helped with the discernment of sexuality themes to be worked on didactically for the outcome of this first stage of the research.

Next, the records that indicated the themes of sexuality addressed are highlighted.

How does a woman date each other? And also the man? (Q2F, 2nd YAE)

Not knowing how to differentiate the top gender from the bottom “gender” in homosexuality. I don't understand that a homosexual is born a homosexual, for me he becomes a homosexual. (Q4M, 2nd YAE)

I myself ask myself “why is she born female and wants to become male?” Or the other way around, vice versa. A person who is born a man and wants to become a woman. (Q6F, 2nd YAE)

What is sexuality, we don't understand this word very much. (Q8F, 3rd YAE)

I would like to know if sexuality is the same thing as wearing tight, short clothes, walking rolling. (Q9M, 3rd YAE)

All, because I don't know how to talk about any. (Q12F, 3rd YAE)

My curiosity is to know why teenagers are more passionate about sexuality. (Q15F, 3th YAE)

I would like to have sex with two women together. (Q21M, 4th YAE)

I have questions about a man who is married to a woman and has a desire to be with other women. (Q23F, 4th YAE)

I'm curious to know what it feels like for a man to want another in his mouth. (Q24M, 4th YAE)

About abortion, homosexual, bisexual, virginity. (Q25F, 4th YAE)

Again, both the misunderstanding of the term sexuality and the dissidence of heterosexual orientation, gender intelligibility and the excessive desire for sexual practice became notorious. These records above suggested some thematic activities linked to the transversality of sexuality, mainly gender expressions and identities, sexual orientations and the discussion of practices considered strange in the social field, such as abortion and polygamy, for example; unlike the study by Zanatta et al. (2016), in which sex education with teenagers was distinguished by the emphasis on medication and on the reproduction of bodies.

It is worth noting that, in this question, one participant recorded her opinion in writing about the thematic proposal of this research, taking a stand against the objective of the study.

The theme is very bad, it's not doing any good. (Q7F, 7nd YAE)

As for this resistant position to the sexuality discourse, Silva (2015) argues that

[...] there is a great gap in this theme to be explored, inside and outside the educational field, since intolerance to sexual diversity implies not only the denial of the right to education, but also the denial of other subjective rights, including the right to life (...) Reflecting on the ways in which education, especially that of young people and adults, acts in the maintenance, or not, of sexual hierarchies, nowadays, seems indispensable and necessary to me. (SILVA, 2015, p. 8).

According to the PCN (BRASIL, 1998), the modification of postures and attitudes towards the topic “it will be through dialogue, reflection and the possibility of reconstructing information, always guided by respect for oneself and for the other, that the student will be able to transform, or reaffirm, concepts and principles, significantly building his own code of values.” (BRASIL, 1998, p. 307).

Reinforcing the attitude towards dialogue, Freire (1987) emphasizes “it is not in silence that men make themselves, but in words, at work, in action-reflection” (FREIRE, 1987, p. 44). For this author, the reflection of the dialogue makes the subject active; and the opposite, if denied, makes dialogue impossible, and do not contribute to his action-reflection, which he names praxis. In other words, it is through dialogue that men and women transform the world, which becomes humanized.

Second phase: elaboration of DS

Zabala (1998) defines DS as “a set of ordered, structured and articulated activities for the achievement of certain educational objectives, which have a beginning and an end known to both teachers and students” (ZABALA, 1998, p.18 ).

This author names DS activities as didactic units, programming units or pedagogical intervention units to

[...] refer to the sequences of activities structured to achieve certain educational goals. These units present the virtue of maintaining an unitary character and bringing together all the complexity of the practice, at the same time as they are instruments that allow the inclusion of the three phases of every reflexive intervention: planning, execution and evaluation. (ZABALA, 1998, p.18).

For Freire, before carrying out any pedagogical activity, it is necessary to consider the social and cultural reality of the subjects, their knowledge and oppressive factors, so that education can then take place in a humanistic and emancipatory way.

The pedagogy of the oppressed, as a humanist and liberating pedagogy, will have two distinct moments. The first, in which the oppressed unveil the world of oppression and commit themselves in praxis, with its transformation; the second, in which, once the oppressive reality has been transformed, this pedagogy ceases to belong to the oppressed and becomes the pedagogy of men in a process of permanent liberation (FREIRE, 1987, p. 23).

In this conception, considering that the student carries some knowledge with him/her, the activities of DS were elaborated from the discussion of Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed; the continuity of sexual education was treated as a permanent didactic strategy for reflection.

When considering the experiences, DS was elaborated from the demands of the students, their experiences, the nature of work in the rural area, contemplating their questions, curiosities and interests in sexuality themes. This information provided in the questionnaire served as the basis for the development of sequential activities.

The elaborated DS thematic suggestion contains activities organized in a sequential manner and relevant to the reality of the students and offers different ways of teaching and learning so that the participants can empower their knowledge in order to answer possible questions and curiosities.

The DS was developed with the insertion and adaptation of activities taken from other sources (notebooks, guides, books), which are mentioned, and by activities elaborated by the researcher teacher.

Next, the DS thematic proposal is presented. It is divided into three activities organized between text reading, dynamics and a workshop for the YAE classes.

Part 1

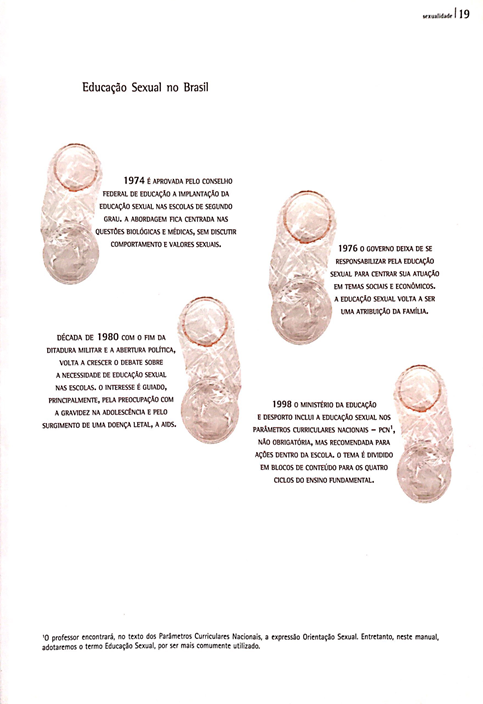

Text: What is sexuality?

This is an “icebreaker” activity, in which participants must speak orally about the word in question. It is not mandatory that everyone speaks out, only those who feel free to speak.

Informal conversation begins from the need to deconstruct that talking about sexuality is talking about sex and the reason for sex education in the school environment. The activity is an adaptation and extraction of the teacher's training notebook, Sexuality, pleasure in knowing (ECOS, 2001).

Length: 90 minutes.

Objective: Conceptualize what is sexuality, sex and sex education.

Material: Blackboard, chalk and copies of the text Sexuality, values and prejudices.

Development:

The teacher should ask the participants to speak, without censorship, what comes to mind when they hear or encounter the word sexuality (20 minutes).

As they speak, write the words on the board.

After the words are said by all students and transcribed on the blackboard, differentiate, explain and clarify what is sexuality, sex and sexual education (25 minutes).

Next, give a copy of the text Sexuality, values and prejudices taken from the training booklet Sexuality, pleasure in knowing (ECOS, 2001, p. 16-19) for each participant. The text should be read and discussed with the students in order to deepen their knowledge about the issues arising from the words that generate this activity: sexuality, sex and sexual education. In addition, the text presents a history of Sexual Education in Brazil, enabling students to know about it (45 minutes).

Part 2

Group dynamics: Stereotypes and Gender Roles

Length: 90 minutes.

Objectives:

- Understand how men and women are socially represented.

- Relate gender stereotypes with the learning that is acquired throughout life, in different fields of knowledge.

- Understand the importance of assertive communication to ensure gender equality.

Materials:

- Images of female and male characters from Disney cartoons known to the subjects.

- Copies of texts portraying case studies on gender roles.

Development:

Divide the class into pairs.

Introduce students to different female and male cartoon characters.

Ask some students to briefly tell the story of each of the cartoon characters presented.

Ask each pair to reflect on the questions presented below. The pairs will have 30 minutes to carry out the reflection. At this point, give each pair a sheet of A4 paper and a pen to take notes on their reflections.

Discussion questions

What is the dominant feature in male characters?

What is the dominant characteristic in female characters?

What role does the character play?

Who is most often assigned the “role” of hero/heroine?

Who is most often assigned the “role” of helpless?

Who is the strongest character?

Who is the most delicate character?

V. After reflection, provide each pair with a case on gender roles. Ask the pairs to read their case and find an answer to the situation exposed.

VI. After each pair finds the solution for their case study,they must read and present to the other students, presenting the solution found. At that moment, the teacher should ask the other pairs to question the solutions found and the group that is presenting to defend their solution, through convincing arguments. Repeat the process until all cases are presented and discussed. This moment lasts about 45 minutes.

VII. Finally, based on the “Discussion Questions”, promote a short 15-minute debate on the importance of gender roles in human relations.

Discussion questions

1. Is it easy or difficult to look at the roles of men and women in a new and untraditional way? Why?

How do men or women accept changes to traditional gender roles? Why?

Would your parents come up with the same or different solutions?

What is the most difficult case study? Why?

If you could make a change in the male gender role, what would it be? And in the role of the female gender, which would it be?

Case 1

Tomé is about to ask Joana, for the first time, if she wants to go out with him, when she turns to him and asks: “Tomé, the open market of the settlement community is going to start today and I really wanted to go and I would like you to go with me. Are you free tonight?” Tomé has no plans for the night and he really wanted to go to the fair with Joana, but he would have liked to invite her. He thinks to answer that he is busy.

What can Tomé say or do?

Case 2

Carlota was offered the possibility of becoming a tractor driver for the community seated in a corn plantation owned by the cooperative association. She is all happy and runs to tell João, her fiance. They had planned to get married the following year and ,this way, she could begin earning good money for their life together. João listens to her in silence and at the end says “I don't think I can marry a tractor driver, Carlota. What will people say? You will have to choose between me and this profession!”

What can Carlota do?

Case 3

Samuel wants to buy a doll for his nephew's birthday, but his friend José says “Don't even think about it!” Samuel explains that the doll can help his nephew to take care of someone and be affectionate, but José argues that it will only make the boy become a “little girl”! Samuel knows he's right, but he's worried about what José might tell his friends in the settled community.

What should Samuel do?

Case 4

Paula and Fernando have been dating for several months and things have been going well between them. Her parents approve this relationship and at the settlement's school she is known to be his girlfriend. However, lately Fernando has been putting more pressure on Paula than she can handle. When she says “No” he tells her that her role, as a woman, is to please him and make him happy.

What can Paula tell him?

Case 5

Sandra and Mário are fighting over their sister Patrícia and her husband Roberto. Sandra has noticed that Patrícia has lately appeared with huge bruises on her arms and shoulders, having even appeared with a black eye in the last week. Mário tells er that Patrícia has been “out of the shell” a lot and that this is Roberto's way of showing her who's in charge at home. Sandra looks at Mário and shakes her head. She thinks violence is never the solution.

What can Sandra do?

Case 6

Carmen decided to have sex with her boyfriend, Gabriel. So, she decides to go into town and look for a pharmacy to buy condoms, but her friend Tânia tells her “women don't buy condoms! This is the function of men”.

What can Carmen say and do?

Case 7

In the settlement, Susana and Miguel have been together for about a year. When they decide to take a walk at the fair in the settled community, to which they belong, Miguel always pays for all the purchases and makes most of the decisions regarding where they go, what they do and what they buy. In Susana's civic education class, the role of women concerning the bill split, dates and their role in the decisions of the couple's plans has been discussed . Both Susana and Miguel work collectively in the settled community and earn little money. Joining their money to pay for what they do together makes sense to Susana, but Miguel gets furious just thinking about it. He says she doesn't think he's man enough to take care of her.

What can Susana say to Miguel?

Source: Adaptation of extraction of Presse 3rd Cycle Notebook. Northern Regional Health Administration, IP Department of Public Health. P. 101-108.

Part 3

Workshop: Sexual and reproductive rights

Objective: To know sexual and reproductive rights (SRR) and to evaluate the extent to which they are respected in our realities.

Length: 90 minutes.

Materials: Audiovisual resources (notebook, data show, speaker and video distinguishing the DSR, copies of informative texts, EVA poster, craft paper, cardboard or A4 paper, markers, masking tape).

Development:

a) Conduct a dialogued expository class on Sexual and Reproductive Rights (SRR) in slideshow (Power-Point resources) lasting 25 minutes. Then, to confirm the understanding of SRR and differentiate them from each other, present the video of the series “Fala direto comigo”, available on You Tube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3VpAL5iDfI ), which lasts for 3 minutes and 27 seconds.

b) After the presentation of the class, divide the students into three groups. They should create two dramatized situations: one in which there was disrespect for sexual and/or reproductive rights, and another in which these rights were respected. At that time, distribute support texts on SRR to the groups, such as Maria da Penha Law, the Declaration of Human Rights, etc., that help or serve as a suggestion for group dramatizations (10 minutes).

c) Each group should perform the role play for each case in 3 minutes.

d) After the presentations, the teacher should discuss the issues that emerge with the participants and, from there, carry out the necessary clarifications to clarify doubts and curiosities.

Source:

Adapted from Sexual rights and reproductive rights (slides). ARENDT, Hannah. Available at: http://www.sociedadesemear.org.br/arquivos/20111025145137_direitossexuaisedireitosreprodutivos.pdf. Accessed on: May 27, 2017.

Adapted and extracted from Health and prevention in schools: guide for the training of health and education professionals/Ministry of Health, Secretariat of Health Surveillance. Brasília: Ministry of Health, 2006. p. 83-86 - (Series A. Standards and Technical Manuals).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

During the readings of the referential contributions that support SE at school, there was a fragmentation and not a continuity of the proposals between the PCN and the BNCC - a fact that reinforces the need for a document supporting the discussions on sexuality and gender, in the classrooms of YAE modality, as well as giving autonomy to the teacher's work so that he/she can discuss and reflect on the context that his/her students experience, in the current political and social scenario. Specifically, for socially disadvantaged populations, such as social movements' settlement schools.

In the exposed, the settlement schools are social spaces of active and participative subjects, with multiple bodies and types of sexuality, marked by their origins and beliefs. Disregarding these subjects would be standardizing them to an inadequate education, forgetting their identities, particularities and diversities, as countryside subjects.

Through the educational proposal of SE, it appears that YAE subjects, specifically from this settlement school, demanded clarification and reflections on the social and cultural construction of sexuality based on their experiences.

In this sense, YAE, consisting of different subjects, should not be considered a mere reward for studies not completed during childhood or adolescence, but rather as a space for discussion and reflection on the daily lives and experiences of students.

Thus, the activities of the DS suggested, according to the particularities of the participants, intend to contribute to the awareness of the sexuality concept, to the understanding and respect for gender differences, signaling the importance of sex education in the school environment. .

Therefore, DS activities, in addition to considering the context of students from settlement schools, should be a continuous pedagogical intervention developed over the YAE periods. Due to its relevance, it appears that performing SE under the historical and cultural perspective of a particular social group means breaking the barriers imposed in school spaces.

Finally, it is suggested that other research and pedagogical interventions should be carried out on the subject, in order to broaden the approach in SE, YAE and settlement school/EC set.

REFERENCES

ALTMANN, Helena. Orientação sexual nos Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais. Estudos Feministas. 2º semestre./2001p. 575-585. [ Links ]

BELL, Judith. Criando e aplicando questionários. In: Projetos de Pesquisa. Guia para pesquisadores iniciantes em Educação, Saúde e Ciências Sociais. 4ª ed. Porto Alegre: ArtMed, 2008, p. 119-133. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil: texto constitucional promulgado em 5 de outubro de 1988, com as alterações determinadas pelas Emendas Constitucionais de Revisão nos 1 a 6/94, pelas Emendas Constitucionais nos. 1/92 a 91/2016 e pelo Decreto Legislativo no 186/2008. - Brasília: Senado Federal, Coordenação de Edições Técnicas, 2016. 496 p. ISBN: 978-85-7018-698-0. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/bitstream/handle/id/518231/CF88_Livro_EC91_2016.pd f. Acesso em: 17 jan. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, DF, 20 de dez.1996. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/lei9394_ldbn1.pdf . Acesso em:19 out. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais: Pluralidade Cultural, orientação sexual. Secretaria de Educação Fundamental. Brasília: MEC/SEF, 1998, 436 p. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução nº. 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprova as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2012/Reso466.pdf . Acesso em:1º jun. 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução nº. 510, de 07 de abrilde 2016a. Aprova as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2016/reso510.pdf . Acesso em:28 maio 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Proposta preliminar. Versão final. Brasília: MEC, 2016b. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_publicacao.pdf . Acesso em: 08 out. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Proposta preliminar. Versão final. Brasília: MEC, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br . Acesso em: 12 out. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Versão final. Brasília: MEC, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_EI_EF_110518_versaofinal_site.pdf . Acesso em: 29 dez. 2019. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Anna Maria Pessoa de. Uma metodologia de pesquisa para estudar os processos de ensino e a aprendizagem em sala de aula. In: SANTOS, Flávia Maria Teixeira dos; GRECA, Ileana María(Orgs.). A pesquisa em ensino de ciências no Brasil e suas metodologias. 1ª ed. Ijuí: Unijuí, 2006, v. 1, p. 13-47. [ Links ]

COSTA, Carolina da Purificação. Gênero e Educação de Jovens e Adultos (EJA): reflexões a partir das orientações curriculares da SEC-BA. In: Seminário Internacional Fazendo Gênero 11 & 13th Women’s Worlds Congress. Anais...Florianópolis, 2017, ISSN 2179-510X. 12 p. [ Links ]

DAMIANI, Magda Floriana et al. Discutindo pesquisas do tipo intervenção pedagógica. In: Cadernos de Educação | FaE/PPGE/UFPel. 2013, p. 57-67. [ Links ]

FACHIN, Odília. Fundamentos de Metodologia/Odília Fachin. 5ª ed. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2006. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. História da sexualidade I: a vontade de saber mais. Tradução de Maria Thereza da Costa Albuquerque e J. A. Guilhon Albuquerque. 13ª ed. Rio de Janeiro, Edições Graal, 1988. 149 p. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. 17ª Ed.Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1987. 107 p. [ Links ]

IBGE, Instituto de Geografia e Estatísticas. 2010. [ Links ]

JULIÃO, Elionaldo Fernandes; BEIRAL, Hellen Jannisy Vieira; FERRARI, Gláucia Maria. As políticas de Educação de Jovens e Adultos na atualidade como desdobramento da constituição e da LDB. In: P O I É S I S - Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação- Mestrado - Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina. Unisul, Tubarão, v. 11, n. 19, p. 40 - 57, Jan./Jun.2017. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.portaldeperiodicos.unisul.br/index.php/Poiesis/index . Acesso em:17 jan. 2019. [ Links ]

LOURO, Guacira Lopes. Currículo, gênero e sexualidade - O “normal”, o “diferente” e o “excêntrico”. In: LOURO, Guaciara Lopes; FELIPE, Jane; Goellner, Silvana Vilodre (Orgs.) Corpo, gênero e sexualidade: um debate contemporâneo na educação. 3ª ed. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2007. p. 41-52. [ Links ]

LOURO, Guacira Lopes. Pedagogias da sexualidade. In: LOURO, Guacira Lopes(Org.). O corpo educado: pedagogias da sexualidade. 3ª Ed.Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2016. p. 7-34. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Luane Cristina Tractz. Da educação rural à educação do campo: conceituação e problematização. In: Educere - XIII Congresso Nacional de Educação. IV Seminário Internacional de Representações Sociais, Subjetividade e Educação - SIRSSE. VISeminário Internacional sobre Profissionalização Docente (SIPD/CÁTEDRA/UNESCO). Anais...ISSN 2176-1396. 2017. p. 18322-18331. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Isabel. Dados como diálogo: construindo dados a partir de registros de observação de interações discursivas em salas de aula de ciências. In: SANTOS, Flávia Maria Teixeira dos; GRECA, Ileana María(Orgs.). A pesquisa em ensino de ciências no Brasil e suas metodologias. 1ª ed. Ijuí: Unijuí, 2006, v. 1, p. 297-321. [ Links ]

MEIRELLES, Elisa; Fernanda, SALLA. As escolas e o MST. In: Revista Nova Escola. Ano 29, Edição 274, Agosto 2014 (Revista Digital). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://novaescola.org.br . Acesso em:29 jan. 2019. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Mônica Castagna; SÁ, Laís Mourão. Escola do Campo. In: Dicionário da Educação do Campo. CALDART, Roseli Salete et al(Orgs). Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo: Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio, Expressão Popular, 2012. p. 326-333. [ Links ]

MST, Princípios da Educação no MST (Caderno de Educação nº 8), 1996. 29 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.reformaagrariaemdados.org.br/biblioteca/caderno-de-estudo/mst-caderno-da-educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o-n%C2%BA-08-%E2%80%93-princ%C3%ADpios-da-educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o-no-mst . Acesso em: 02 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

MST, Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra. 2006. [ Links ]

PRADO, Di Paula Ferreira; REIS, Sônia Maria Alves De Oliveira. Educação de Jovens e Adultos: o que revelam os sujeitos?In: XVIENDIPE - Encontro Nacional de Didática e Práticas de Ensino. Anais... UNICAMP, Campinas, SP, 2012. 11 p. [ Links ]

RAEL, Claudia Cordeiro. Gênero e sexualidade nos desenhos da Disney. In: LOURO, Guaciara Lopes; FELIPE, Jane; Goellner, Silvana Vilodre(Orgs.) Corpo, gênero e sexualidade: um debate contemporâneo na educação. 3ª ed.Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2007. p. 160-171. [ Links ]

SANTIAGO, Nilda Gonçalves Vieira. A Educação de Jovens e Adultos numa perspectiva de letramento. 2014. 9 p. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Nathany Ribeiro Lima dos; PEREIRA, Sara; SOARES, Zilene Moreira Pereira. Documentos curriculares oficiais assegurando a abordagem de gênero e sexualidade para a educação básica: um olhar para o ensino de ciências. In: VSimpósio Gênero e Políticas Públicas. Anais...Universidade Estadual de Londrina. 2018. 16 p. [ Links ]

SILVA, Jerry Adriani da. Educação de Jovens e Adultos - EJA, diversidade sexual, pessoas LGBTs e processos de socialização. In: VSeminário Nacional Formação de Educadores. Anais... Faculdade de Educação, Unicamp, Campinas/SP. 2015. 17 p. [ Links ]

SILVA, Jerry Adriani da. Diversidade Sexual na Educação de Jovens e Adultos (Eja). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. In: Revista Cátedra Digital. ISSN: 2525-7110. 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://revista.catedra.puc-rio.br/index.php/diversidade-sexual-na-educacao-de-jovens-e-adultos-eja/ . Acesso em:01 jul. 2018. [ Links ]

SILVA, Maria José da; ARANTES, Adlene Silva. Questões de gênero e orientação sexual no currículo, a partir da BNCC. In: IVCongresso Nacional de Educação- CONEDU, Anais... 2017. 9 p. [ Links ]

SOARES, Marina Nunes Teixeira; GASTAL, Maria Luiza de Araújo. Educação sexual para jovens e adultos: contribuições ao ensino de Ciências à luz de uma abordagem emancipatória. In: SBEnBio - Associação Brasileira de Ensino de Biologia. IV ENEBIO e II EREBIO da Regional 4. Anais...Goiânia, 18 a 21 set.2012. 9 p. [ Links ]

SOUZA JUNIOR, Paulo Roberto. A questão de gênero, sexualidade e orientação sexual na atual Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC) e o movimento LGBTTQIS. In: Revista de Gênero, Sexualidade e Direito. e-ISSN: 2525-9849. Salvador, v. 4, n. 1, p. 1-21, Jan/Jun.2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.indexlaw.org/index.php/revistagsd/article/download/3924/pdf . Acesso em: 21 abr. 2019. [ Links ]

WEEKS, Jerffrey. O corpo e a sexualidade. In: LOURO, Guacira Lopes(Org.). O corpo educado: pedagogias da sexualidade. 3ª Ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2016. p. 35-81. [ Links ]

ZABALA, Antoni. A prática educativa: como ensinar. Trad. Ernani F. da Rosa - Porto Alegre: ArtMed, 1998. 224p. ISBN 978-85-7307-426-0. [ Links ]

ZANATTA, Luiz Fabiano et al. A educação em sexualidade na escola itinerante do MST: percepções dos(as) educandos(as). In: Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 42, n. 2, p. 443-458, abr./jun. 2016. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1517-9702201606144556 [ Links ]

Received: November 17, 2019; Accepted: September 01, 2020

texto em

texto em