Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 08-Sep-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469820762

ARTICLE

"THE SUN OF FREEDOM"? THE EDUCATION OF ENSLAVED, FREEDMEN AND INGENUOUS (1871-1875)

1 Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ). Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. Researcher for CNPq and FAPERJ <gondra.uerj@gmail.com>

2PhD in Education from the Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ). Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. FAPERJ scholarship holder. <fnascimento1002@gmail.com>

In this article, we seek to give visibility to the speeches made in the House of Representatives and in the Senate about the approval of the Free Womb Law. After all, how did the enslaved population face the new situation and what measures were taken to abolish what some considered as the "blackest slavery: ignorance"? To explore this question, we analyze the debates that took place during the drafting, processing and approval of the Law of September 28, 1871, the so-called "Free Womb Law", based on documents from the House of Representatives and the Senate, produced during the administration of João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira at the Ministry of the Empire's Businesses (1871-1975). With this investment, we analyze some aspects related to the access to formal or informal schooling of blacks, enslaved, freedmen and ingénues. In order to reflect on the effects of this project, we consulted printed materials circulating at that time, such as Gazeta da Tarde (Evening Gazette), A Instrucção Pública (The Public Instruction), Illustração Brasileira (Brazilian Illustration) and Jornal do Commercio (Trade Newspaper), in which we found important information about the debates and positions of this reform in the legislative apparatus and in public opinion. The mentioned printed materials also functioned as important sources to understand aspects and challenges of the schooling of blacks, slaves and ingenuous in the focused period.

Keywords: Free Womb Law; João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira; Slavery; Ministry of the Empire Business

Neste artigo, procuramos dar visibilidade aos discursos proferidos na Câmara dos Deputados e no Senado acerca da aprovação da Lei do Ventre Livre. Afinal, como a população escravizada enfrentou a nova situação e que medidas foram tomadas para abolir o que alguns consideravam como a “mais negra escravidão: a ignorância”? Para explorar esta questão, analisamos os debates presentes na elaboração, tramitação e aprovação da Lei de 28 de setembro de 1871, a chamada “Lei do Ventre Livre”, tomando por base documentação da Câmara dos Deputados e do Senado, produzida durante a gestão de João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira no Ministério dos Negócios do Império (1871-1975). Com este investimento, analisamos alguns aspectos relacionados ao acesso à escolarização formal ou informal de negros, escravizados, libertos e ingênuos. Para refletir a respeito dos efeitos deste projeto, consultamos impressos que circularam à época, tais como: Gazeta da Tarde, A Instrucção Pública, Illustração Brasileira e Jornal do Commercio, nos quais localizamos índices importantes a respeito dos debates e posições desta reforma no aparato legislativo e na opinião pública. Os referidos impressos também funcionaram como fontes importantes para compreender aspectos e desafios da escolarização de negros, escravizados e ingênuos no período focalizado.

Palavras-chave: Lei do Ventre Livre; João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira; Escravidão; Ministério dos Negócios do Império

En este artículo, buscamos dar visibilidad a los discursos pronunciados en la Cámara de Diputados y en el Senado, sobre la aprobación de la Ley del Vientre Libre. Después de todo, ¿cómo afrontó la población esclavizada la nueva situación y qué medidas se tomaron para abolir lo que algunos consideraban la "esclavitud más negra: la ignorancia"? Para explorar esta cuestión, analizamos los debates presentes en la preparación, tramitación y aprobación de la Ley del 28 de septiembre de 1871, la llamada "Ley del Vientre Libre", basada en la documentación de la Cámara de Diputados y del Senado, elaborada durante la administración de João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira en el Ministerio de Negocios del Imperio (1871-1975). Con esta investigación se busca abordar algunos aspectos relacionados con el acceso a la educación formal o informal de las personas negras, esclavizadas, libres e ingenuas. Para reflexionar sobre los efectos de este proyecto, analizamos el material impreso que circulaba en la época, como: Gazeta da Tarde, A Instrucção Pública, Illustração Brasileira y Jornal do Commercio, en el que encontramos importantes índices sobre los debates y posiciones de esta reforma en el aparato legislativo y en la opinión pública. De la misma manera, el material impreso sirvió como fuentes importantes para comprender aspectos y desafíos de la escolarización de las personas negras, esclavizadas e ingenuas en el período en cuestión.

Palabras clave: Ley del vientre libre; João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira; Esclavitud; Ministerio de Negocios del Imperio

INTRODUCTION

The 27th of September!

Vincula servitii tandem sunt saeva remissa.3 C. L.

"The month of September, the month of spring and flowers, is doubly flattering to the great American Empire.

The 7th dawned to record in the list of independent nations the autonomy of the nascent Empire.

The 27th dissipated from the Brazilian horizon the only cloud that obscured its brightness.

The first consecrated the independence of a people.

The second came to illuminate freedom in its fullness.

Hail September 27th, you who came to launch a milestone on the road to civilization and progress!

From this day forward, those who are born in this beautiful American land, will be born for freedom, and the chains of serfdom, the shackles of slavery, the humiliation of captivity, will no longer kill at birth the most flattering hopes, the most gratifying aspirations!

Glory to the Brazilian nation, which by a noble effort was able to place itself next to the most important and civilized nations in the world.

Recognition and respect to the monarch who took upon himself the generous effort of making the grand idea of freeing slaves come true.

Gratitude to the Cabinet that fought against the unbridled fury of wounded interests; against that legion of spite, of ignoble ambitions, of retrograde ideas that gathered to impede his step.

Happy are the unborn, because for them the sun of freedom has dawned!

(ILLUSTRATED WEEKLY, October 1, 1871).4

Reforms are part of the political agenda, sometimes more general, sometimes more specific. The proposal to carry out a set of reforms during the process of building the national state was the solution found by the government to deal with the social challenges that intensified after the 1870s5. Resulting from a set of elements that had been in place for decades, the conjuncture that mobilized the political environment in the 1970s led the leaderships to take some measures to mitigate the effects of political instability and ensure a favorable public opinion for the monarchy. The set of actions promoted were important to reorganize the social forces and prevent or delay certain projects, such as the abolition of slavery and the establishment of the Republic. In this sense, one of the central points of the political agenda was the project of emancipation of the serf element. However, how to deal with this problem? Should there be liberation of the enslaved? Should it be a full emancipation? Should it be gradual? Of what kind? Should it not be realized? Why should it not take place? In either scenario, one question remained: how to manage the access of the enslaved population to the world of literate culture? Finally, how and how should the enslaved, the naïve, and the freedmen be educated? These are the central questions that inspired and guided this work.

In the general imaginary, being a slave had an almost direct correlation with the color of one's skin. In this key, the black person was sometimes confused with the condition of being a slave6, as can be observed in the 1826 session of the Chamber of Deputies, in which Vasconcellos7 stated: "the presumption is that a black man is always a slave". This statement from the tribune of the "old jail"8 was contested by his colleagues on the bench, with remarks such as: "To say that a man of the black race should be considered a slave every time he does not prove the contrary is absurd, it is an insult to humanity in the person of this wretch" [...] "Any man has the presumption of being free, because all were born that way". Shifting the debate to the level of Brazilian legislation, the deputy from Minas Gerais replied: "I spoke in the form of our legislation when I said that the presumption is that the black man is a slave: this is the presumption that exists in it, and I am not obliged to say more. I did not say that blacks should always be enslaved" (SOUSA, 2015, p. 52).

Schueler and Teixeira resume the discussion about the simple, direct and mechanical correlation between blackness and slavery. In considering the centrality of slavery and inequality in imperial society, these authors point out the complexity of the legal and social status of blacks, free and freedmen, with indications of social ascension by portions of the black population in urban areas. They also observed that many blacks got involved in the process for the end of slavery and in the fight for access to school, especially in the years 1870 and 1880 (SCHUELER; TEIXEIRA, 2015).9

In this paper, we invest in the debates in the House of Representatives and the Senate about the approval of the emancipation reform in 1871, a measure that would contribute to definitively dissociate the supposed pair blackness-slavery. By examining the process surrounding this norm and the gradualism it represented with regard to the elimination of the serf element, we can see the obstacles and disputes it caused. In order not to remain within the limits of the normative and the disputes around the legal and the legal, the other movement carried out in the work corresponds to the analysis of initiatives that enabled the access of the enslaved, blacks, freedmen and commoners to the literate culture, with evidence of the participation of various groups, people, associations and clubs, among others10.

HE WHO FIGHTS, FREES: BETWEEN THE ENSLAVED AND THE INGENUOUS

On September 29, 1870, the Cabinet of José Antônio Pimenta Bueno11, the Marquis of São Vicente, was organized, inviting João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira12 to manage the Empire's portfolio. On this occasion, the emancipation question was taking on new contours and it was necessary to face it. Initially, the referred Marquis was the one who stood out in the Council of State in this matter, for he had the honor of being one of the first government men "that in the slaves issue tried and succeeded to move our whole political mechanism, - Emperor, Council of State, Ministry, - to have been the first to formulate the set of measures that uprooted slavery from our soil in 1871" (NABUCO, 1899, p. 179). However, the Marquis of St. Vincent was not a party leader, an orator with the stamina that the parliamentary struggle demanded. Thus, he did not get the support of the conservatives and was openly opposed by the liberals (LYRA, 1978). On March 07, 1871, São Vicente passed the presidency of the Cabinet to José Maria da Silva Paranhos13, the Viscount of Rio Branco, who had more appropriate characteristics for the discussion required by the reform aimed at the emancipation of the slave element. When referring to Rio Branco, Alonso underlines: "Love of mathematics, experience in negotiation, modernizing zeal and proverbial cold blood made Rio Branco the captain capable of crossing the wild sea in which São Vicente was shipwrecked" (ALONSO, 2015, p. 54).

When organizing the Cabinet of the Secretary of State for the Affairs of the Empire14, Rio Branco kept João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira in the post of Minister of the Affairs of the Empire. At the beginning of his term, he offers clues as to the reason that led him to change all the portfolios in his Cabinet, except the one under Oliveira's responsibility. According to Nabuco, João Alfredo "in the very first session in which he addressed the Chamber as Minister of the Empire, conquered, in Rio Branco's phrase, the baton of Marshal" (NABUCO, 1899, p. 203).

Rio Branco would not reform as much as the abolitionists wanted, nor would he leave everything the way it was, as the "stuck" clamored (ALONSO, 2015). Operating in a scenario of increasingly polarized interests, the Viscount needed all the support possible, because there was a great resistance to the approval of a reform that would change the social, economic and educational structure of a country that had been built on the pillar of slavery. Reflecting on the influence of slavery in society, Joaquim Nabuco enumerates some elements that justified, in some respects, the "nature" of slavery:

Quite the opposite, on the contrary, when it was possible to extinguish the cancer and repudiate in the benefit of the inventory the servitude inherited from the metropolis, the arms were opened to African emigration, as it was said, that is, to the trafficking of blacks. All the crimes that the imagination can conceive, from the throwing of hundreds of living men into the sea to the death, in the hold, by suffocation, of so many other unfortunates, everything falls like an enormous responsibility of blood on our heads.

This is why today, when we want to get rid of this evil without shaking, we cannot.

It has the age of our country: we were born with it; we live with it. It is like a virus that has soaked into our blood for centuries.

Our whole social existence is fed by this crime: we grew up on it, it is the basis of our society. Where does our fortune come from? From our slave production. Suppress slavery today, you will have suppressed the country. This is how the moral law reacts. Our freedom made us choose the path of crime, we followed it: today when we want to get out of it we are nailed to it (NABUCO, 1988, p. 32).

With a long tradition, strongly anchored in the economy based on slave labor and customs, slavery assumed legitimacy, having been strongly institutionalized as shown in the study by Alonso (2015, p. 53): "Only fools would rebel against the natural order of things, which was not in force by the will of some, but by necessity of all. Criticism of "the natural order" was taking to the streets and entering parliament. Among the biggest supporters of the "senseless" project were Sales Torres Homem15, São Vicente, Bom Retiro16 and João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira (HOLANDA, 1972).

The resistance to the emancipation reform in the Chamber of Deputies, on the other hand, was led by Paulino de Souza17, with the collaboration of representatives such as José de Alencar18 and Ferreira Viana19, for example. The Conservative party was divided, as some conservative congressmen were in favor of the gradual emancipation of the serf element, despite the strong opposition front, led by Souza. Among the Liberals, the division was less noticeable, due to the absence of representatives in the Chamber of Deputies. In the Senate, the emancipation project found supporters such as Nabuco de Araújo20 and Paranaguá21. The opposition was supported by the militant Zacarias22, who fought every article of the reform (HOLANDA, 1972).

The impasse made the mayor bring together the government and the dissidents in an attempt to reach an agreement, without success. Paulino remained adamant and the government members did not negotiate the core of the project; the free womb. The sessions were obstructed by the minority, who used tricks: they prevented quorums, invented meetings at session times, and delayed deputies' watches, among other actions. This set of strategies sought to test the strength and organization of the emancipationists, insofar as it forced them to make an effort to put their entire base in the Chamber. According to the observations of Angela Alonso (2015), to face this situation, Corrêa de Oliveira seems to have had a great participation. According to her, the other batch of deputies, trickier, joined thanks to the halter of the Minister of the Business of the Empire, who, as a kind of "ministerial lightning rod", hunted deputies at home, put sentries so that they would stay in the session, even dragging a deputy with fever to the plenary.

As can be seen, the project's passage through the House of Representatives was not smooth. The minister from Pernambuco was in the front, urging the statesmen to attend the sessions. According to Barreto (1884, p. 85), "The minister of the Empire, Councilor João Alfredo, whose energy powerfully influenced the less courageous governors", was one of those who most helped the President of the Council. His tenure in the ministerial portfolio, the longest in the Empire, earned him the reputation of:

An intelligent, hardworking, enterprising, broad-sighted administrator, very concerned with public education and the capital's improvements, but what earned him priceless laurels was his collaboration in the law of September 28, 1871. At the time, he was called the taciturn leader of the closings, a regimental resource that the government made great use of to avoid delaying debates. [...] His assistants had another role reserved for them. And no one performed his better than João Alfredo, gathering and disciplining the majority, bringing them into the chamber and making them support the government's action (LYRA, 1978, p. 211, emphasis added).

The way the ministers conducted the emancipation project was being observed in several instances. The effort that the Ministry erected to achieve success in the approval of the proposal was observed by Senator Souza Franco23 in a heated discussion with Rio Branco in the Senate:

Mr. Souza Franco - I congratulate you for the fact, but not for the way, because you promote this great humanitarian act and advantageous to the Empire; tearing it by force to the chamber of deputies, and dragging your friends, representatives of the nation, under the caudine forces. [...]

Mr. Viscount of Rio Branco (President of the Council): - I have already complained against this.

Mr. Souza Franco - So that it may be recorded in the annals that the slaveholding Brazil decided not to decree the manumission of its slaves, but it was not spontaneous. The strong arm of Mr. Viscount of Rio Branco (this name shall remain in our memory) snatched it from the representatives of the nation. This is what S. Ex. in the Jornal do Commercio. [...]

Mr. Viscount of Rio Branco (President of the Council): - Who said that the Council was being forced? Just the opposite is said; I was even censured for my moderation by the noble Senator for Bahia, who said that I had disarmed the Ministry.

Mr. Zacarias - Yes, sir. [...]

Mr. Souza Franco - Then you must retreat. Ex. must retreat for lack of enthusiasm and will not pass the emancipation law.

Mr. Viscount of Rio Branco (President of the Council): - So we must take it by force, according to you? (ANAIS DO SENADO, May 17, 1871, p. 113).

The discussions about the emancipation project were equally heated in the Chamber of Deputies, as shown by the debate that took place in the session of May 16, 1871, in which Mr. Saraiva24 questioned

Yes, if for the emancipation of the slave... emancipation, no; the project does not deal with the emancipation of the actual enslaved, and only with extinguishing the source of slavery without prejudice to the masters. If to achieve such a prudent reform, and which is not political, the Ministry struggles with so many difficulties, what embarrassments will it not find as soon as it tries to make the freedom of vote, and thus threaten the hope that the conservative party has to keep the power for a century or more? (Senate Annals, May 16, 1871, p. 94).

The radicalization and polarization of the speeches brought up issues that were not on the agenda, but presented themselves as a problem to be solved by the ministry, indicating a redirection of the debate. In this case, Mr. Saraiva brought up for discussion the electoral reform, another item on the reform agenda of the period.

The August 2nd session was marked by generalized disorder. Article 4 of the bill was under discussion. Mr. Paulino requested a roll-call vote, in which article 4 was approved with 59 votes in favor and 39 against. As a strategy, to prevent the vote on the 5th article, the dissidents spoke about other subjects, such as electoral reform. The president warned that the agenda was different, without having the desired effect. There was a reaction from the government members, who requested the session's extension. After the procedural discussions and many comments, from both the opposition and the situation, the governors managed to move on to the debate on the 5th article.

The opposition accused the chief of staff of subservience to the emperor (ALONSO, 2015). At this point, Rio Branco asked the President to call the speaker to order. The insults continued until Rio Branco, exalted by the words he had heard, exclaimed, "V. Excellency is in no state to deliberate." Everyone stood up, shouting loudly. The Speaker of the House addressed the President of the Council saying, "You Minister cannot use those words in relation to a member of the House. Only the Speaker of the House has that right." Rio Branco tries to explain that he had called the President's attention to the speaker's words, but it was useless, for disorder had become widespread. Feeling unable to reestablish order, the President of the Chamber suspended the session, after declaring his resignation from office (HOLANDA, 1972).

The Ministry's efforts to approve the reform, the conservative party's division, the heated sessions and the Chamber's president's resignation made 1871 a year marked by turbulence between the ruling and dissenting parties, with the institute of slavery as the neuralgic point. The construction of very marked positions leads us to "think about the symbolic dimension of political power, about how the State uses theatrical devices to represent and stage the power that it effectively exercises" (SCHWARCZ, 2001, p. 7).

Concerns and fears were literally driving the debates in society. There was a lot at stake, as the free womb was represented as a threat to the economy, as it could break farmers and merchants. At the same time, if it failed in its goals, it would ruin politics, with the discredit derived from its failure. As highlighted by Alonso (2015), the free womb would cause classes such as commerce and farming, which firmly supported the monarchy, to be able to divorce themselves from it.

After the long and untimely debates in the House, on August 29, the bill with the amendments was sent to the Senate, where the discussions were a little calmer. When it was sanctioned by the imperial princess regent, it became Law 2,040 of September 28, 1871, known as the Free Womb Law.

On October 15, 1871 the Magazine Semana Ilustrada (Illustrated Week Magazine) published a "notice" about a painting commemorating the September 28th Decree, drawn up by the Imperial Artistic Institute of Rio de Janeiro:

Source: Semana Ilustrada (RJ), October 15, 1871, ed. 566, p. 7.

Image translation:

NOTICE. The IMPERIAL ARTIST INSTITUTE of Rio de Janeiro has published a large commemorative picture of the decree of September 28th, 1871, representing the portraits of H.M. the Emperor, H.H. the Princess Regent and those of the Ministry of March 7th; and in emblems the liberation of slaves, agriculture, commerce, colonization and immigration, the allegorical figures of Gloria and History.

The title of the painting is: HONOR AND GLORY TO THE MINISTER OF MARCH 7, 1771, because it was he who laid the cornerstone of the great building of the abolition of the servile element, a fact that in the whole world will produce the most brilliant impression and whose results will reflect on Brazil as, until now, only the declaration of Independence in the fields of Ypiranga did, placing it alongside the most civilized nations of the world.

For sale at the IMPERIAL INSTITUTO ARTISTICO, Primeiro de Março Street (March 1st) (formerly Right) n. 21.

Price per painting 10$000.

Figure 1 - Semana Ilustrada. Commemorative Board.

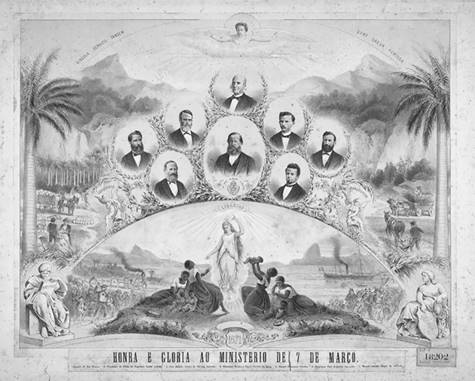

The ad describes the representations projected on the board entitled "Honor and Glory to the Ministry March 7, 1871. A tribute to the main agents who, in the political game, disputed the project in the Chamber's plenary. The opinions were divided, a part of society and statesmen clamored for the reform, which would change the lives of the enslaved population and their children, but would also directly affect commerce and agriculture. In this sense, to defend or be against emancipation meant to support different national projects. For the advocates of the gradual abolition of slavery, the measure expressed the desire for freedom and equality for all Brazilians as an indispensable element for the formation of a civilized Nation. For the opponents, the project constituted a kind of negative, a risk to the order, instituted under the aegis of the labor of the enslaved.

In the aforementioned "notice" there is a description of a set of elements that represented slavery, they are: emblems the liberation of the enslaved, agriculture, trade, colonization, immigration, the allegorical figures of Glory and History. By highlighting these elements in the picture (figure 2), the reader is thrown into a well-defined symbolic universe25.

Source: Biblioteca digital luso-brasileira (Luso-Brazilian digital library). Available at: http://objdigital.bn.br/acervo_digital/div_iconografia/icon1208241/icon1208241.jpg. Accessed on: 01 jan. 2021.

Figure 2 Honor and Glory to the Ministry March 7, 1871.

The centrality of the figure of the Emperor, Princess Isabel and the components of the March 7th Ministry in the painting serves to fix the image of these agents. It is also an attempt to highlight the protagonists of an event aimed at changing the social, economic, political, cultural, and educational configuration of the country. It is, finally, an attempt to inculcate in society a collective memory, which "is essentially mythical, deformed, anachronistic, but constitutes the lived experience of this never-finished relationship between the present and the past" (LE GOFF, 1990, p. 22-23).

In seeking to constitute a collective memory of the emancipation policy, gradual in character, the picture merges elements of nature, industry, Catholic religion, black women in a gesture of gratitude, at the same time indicating that the civilizing task and the path to progress was associated with two other phenomena: colonization and immigration. Thus, the tripod of a new policy of support for the Empire was assembled.

The writer of the ad attributed to the Free Womb Law a status similar to that of the Independence of Brazil, as was also registered in Semana Illustrada, highlighted in the epigraph of this article. It is a matter of considering the freedom of the enslaved and of the Nation as equivalent, since to free a portion of the population, the enslaved, should assume the meaning of completing an unfinished task, both resulting from many mediations, conflicts and death26.

Machado de Assis27, an attentive observer of public life, frequented the sessions of Parliament and in his chronicles made some satires and criticisms of the government. In March 1877 he wrote in the Magazine Illustração Brasileira (Brazilian Illustration Magazine): "In representative countries public life is mainly in the Chambers. Who doesn't remember the sessions of 1871? Life is struggle; where there is opposition, there is contrast, there is life" (Illustração Brasileira, March 1, 1877, ed. 17, p. 9).

As an additional highlight of this "place of memory" (NORA, 1993), it refers to the Latin emblems. The commemorative picture recovers the Latin phrase, published 14 days earlier in the Magazine Semana Illustrada, with the addition of a new motto: In hoc signo vinces. Located on the coat of arms of the Imperial State, between the image of the emperor and the word liberty, this phrase was also inscribed on the Brazilian silver coins of the Empire of Brazil, with various values; multiplying indefinitely the message in a non-disposable support. On one side, the figure of the emperor. On the other, the coat of arms and the illustratedmotto, which seeks to synthesize a kind of destiny of the regime: win!

Source: Brazilian Mint Available at: http://www.moedasdobrasil.com.br/moedas/catalogo.asp?s=105&xm=462 Accessed on: 01 Jan. 2021.

Figure 3 Silver Coins- In hoc signo vinces

In a free translation, the expression reproduced in various media means "With this sign you shall overcome". What signs does it seem to refer to? There are indications that it refers to a set of signs that make up the painting, and here we must emphasize the convergence with the sign of freedom. This, in turn, is associated with the central figure of Dom Pedro II, flanked by the body of ministers, composed of seven men, anointed by celestial figures. In the margins, history and glory, encompass a prodigious nature, hard-working and productive people in agriculture and commerce, whose increase is connected to the end of the servile element. Finally, the enslaved women appear in a grateful, subservient position, which ends up erasing the diverse strategies activated by the enslaved population, a very strong trait in the historiography of education, according to studies such as that of Fonseca (2007).

The liberation of children born from the womb of slaves, starting with the Law of September 28, 1871, constitutes, therefore, a milestone in the history of slavery, with diverse effects, being worth noting some of those that affected part of the enslaved population, especially those who were formally born free.

BETWEEN LASHINGS AND BOOKS: THE EDUCATION OF BLACKS, SLAVES AND INGENUOUS

What to do with the productive forces that became free, those degraded by the slavery system that, from then on, would be freed from the bonds of slavery and from the private control of the lordly power? (SCHUELER, 2005, p. 20, emphasis added).

The question presented by Schueler was related to the educational debates of the second half of the 19th century, especially after the Law of September 28, 1871. In this sense, the education of the naïve started to be discussed in several instances of the Brazilian Empire, in search for solutions for the education of the unborn. The sentence published in the journal A Instrução Pública (The Public Instruction), 1872, illustrates the public opinion of the time about emancipation: "The Law of September 28 was the harbinger of general freedom for the enslaved: let us now get together and work vigorously for the abolition of the blackest slavery: ignorance" (A Instrução Pública, 1872, p. 5).

Public officials sometimes criticized the Law of September 28, using the instruction of the ingenuous as an obstacle, as occurred in the Senate in 1879:

Mr. Marquez do Herval (Minister of War) - Gentlemen, I wish that everyone in this country were doctors....Mr. Baron of Cotegipe - No bull in this house of wasps (laughs).

Mr. Marquez do Herval (Minister of War) - ... I wish that even the little black boys, the ingenuous ones of the September 28th law, were educated and trained (laughter), but, gentlemen, since we don't have enough to support the army; since we don't have enough to support a fleet whose ships are mostly useless; since we don't have enough to give roads to agriculture; since we don't have enough to give useful arms to agriculture, since agriculture lacks arms, and we haven't been asked to give anything but young men... (Applause; laughter). [...]

Mr. Marquez do Herval (Minister of War) - ... who come to Brazil for the weight of gold and don't want to work....

Mr. Marquez do Herval (Minister of War) - ... ... not having so many needs to meet, we should not only take care of educational establishments (ANAIS DO SENADO, February 7, 1879, p. 70).

The debate focuses on one of the most discussed issues in both Chambers, during and after the passage of the emancipation project: the education of the unborn. As can be seen, this is a session from 1879, eight years after the promulgation of the Free Womb Law, an occurrence which indicates that the education of the unborn did not end with the approval of the law of September 28, 1871.

The struggles and movements around definitions of citizenship, including among blacks and mestizos, between freedom and slavery are indicative of the cleavages that characterized a hierarchical, aristocratic, and monarchical society that maintained, for example, the monopoly over land and slaves, as stated in the Constitution of 1824, which recognized an old colonial tradition.

Regulation No. 1.331-A, of February 17, 1854, maintained the prohibition of enrollment and attendance to schools by subjects submitted to the slavery regime. However, several studies in the field of History of Education point to the presence of slaves who could read, write, and count in 19th century society. In the nineteenth century, several educational forces configured spaces and networks of formal and informal sociability, which favored the insertion of poor, devoid, enslaved, freedmen and ingenuous in the literate world (SEBRÃO, 2015; FONSECA & BARROS (orgs), 2016; MAC CORD; ARAÚJO & GOMES (orgs), 2017; LOPES, 2020).

In studies regarding the issue of instruction and education of children born after the Free Womb Law, Lopes (2012) points out that the Manifesto of the Brazilian Society against Slavery characterizes the referred Law as conservative because it respects the interests of the masters, assuring them the property of their enslaved28. At the same time, the aforementioned Manifesto recognizes the emancipation of the unborn as a blow to the slave system, by being described as the "Law of Emancipation", a mode of representation that would have induced the belief, outside the country, that Brazil had freed, at once, about one and a half million slaves.

The author corroborates the statement that the Free Womb Law legitimated the return of the children of slaves to captivity, condemning them to the same condition as their parents, given the fact that the owner could preserve responsibility over the unborn child until the age of 21. Lopes points out that the issue of underprivileged children and the issue of the free children of enslaved women were simultaneously posed in the final decades of the 19th century. For her, the education of the ingenuous was articulated to the problems related to poor and devoid children, which, in a way, represented the failure of a more egalitarian education policy regarding the insertion of ingenuous in a society based on free labor.

The author resumes the arguments of the Minister José Antônio Saraiva, when this statesman had affirmed that, due to the small number of minors delivered to the State, it was not necessary to think of specific educational establishments for children born from the free belly, marking his preference for appropriate establishments for the education of orphaned and disabled minors, institutions that should also serve the ingenuous Two institutions in the Neutral Municipality were created to fulfill this function, the Santa Isabel Agricultural Asylum and the Homeless Boys Asylum (LOPES, 2012). According to the studies of (NASCIMENTO, 2016), the education of the ingenuous seems to have availed itself of the strategy of an education articulated to the training for work:

The imperial society was concerned about the fate of this social layer, the children born from the free womb, and the educational control of this new model of childhood should be part of a social framework organized on the moral and civilizing precepts in course. The solution was not simple. Some traces point to measures adopted to ease this problem, such as the creation of colleges, mainly, the professional schools (NASCIMENTO, 2016, p. 157).

In 1875, the Minister João Alfredo inaugurated the Asylum for Disabled Boys29 for the reception of abandoned minors, orphans and ingenuous. The institution was to offer primary and vocational education. In 1874, in the report presented to the Legislative Assembly, Minister João Alfredo announced the creation of the Asylum for Disabled Boys, which would meet the articles 62 and 63 of the Regulation of 1854, which dealt with the withdrawal to the asylum institution, children in a state of poverty and living in begging. As long as the law had not been established, the children could be handed over to parish priests, curates, or even to district teachers. After receiving first grade education, the boys would be sent to the apprentice companies of the arsenals or to public or private workshops, by contract.

Despite notifying the creation of the asylum as a response to the legislation in force, the project prepared during João Alfredo's ministerial administration, according to paragraph 5 of Project 73/1874 established

Professional schools will be created in the municipalities of the provinces of the Empire, in which the sciences and their applications that best suit the prevailing arts and industries will be taught. The study plans of these schools shall be organized so that the students, who wish to do so, may, at the end of the course, complete their studies in the establishments mentioned in § 12 - III, taking into account the exams of the subjects they have already learned.

§ 12. the government may:

III. - Assist the private establishments of free primary and professional education of the same municipality that prove themselves worthy of this favor, with preference being given to those that propose to maintain night courses for adults, and the respective directors being subject to the same obligations as public teachers in relation to the Inspector of Education (PROJETO 73/1874, p. 2-3).

It can be seen that the Ministry did not wait for the approval of the aforementioned project by the Chamber of Deputies30 to create an asylums and professionalizing institution for the reception of poor, underprivileged and orphaned boys31, which would also serve to receive those born of the free womb.

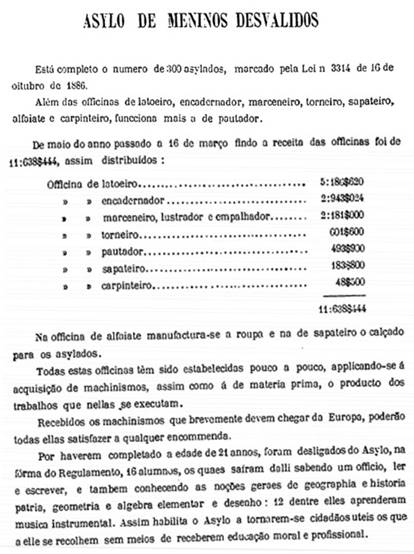

To get an idea of the effect of this measure, fifteen years after the promulgation of the Free Womb Law, the Report of the Minister of the Empire presented the following results about the Asylum for Disabled Boys:

Source: Report of the Minister of the Empire 1886, p. 58-59.

Image Translation:

HOME FOR DESTITUTE BOYS

The number of 300 asylums set by Law 3314 of October 16, 1886 is complete.

In addition to the workshops of cobbler, bookbinder, joiner, woodworker, lathe operator, shoemaker, tailor and carpenter, there is also a workshop for the tariff.

From May of last year to March 16 last, the revenue of the workshops was 11:638$444, distributed like this:

Tinsmith workshop --- 5:186$620

Bookbinder's workshop --- 2:943$024

Cabinetmaker's workshop, polisher and stuffer --- 2:181$000

Turnery workshop --- 601$600

Tariff workshop --- 493$900

Shoemaker's workshop --- 183$800

Carpenter's workshop --- 48$300

Total: 11:638$444

The tailor's workshop manufactures clothing, and the shoemaker's workshop makes shoes for the asylums.

All these workshops have been established little by little, applying the acquisition of machineries, as well as of raw material, the product of the works that are executed in them.

Once they receive the machineries that will soon arrive from Europe, they will all be able to satisfy any order.

For having completed the age of 21 years, 16 students were discharged from the Asylum, according to the Regulation, and left there knowing a trade, reading and writing, and also knowing the general notions of geography and national history, geometry and elementary algebra and drawing: 12 of them learned instrumental music. The Asylum thus enables those who come to it without the means to receive a moral and professional education to become useful citizens.

Figure 4 Asylum for Disabled Boys

The number of 300 asylums received in the institution corresponded to the maximum amount allowed by Law No. 3114 of October 16, 1886. It can be seen that there were no vacant positions in the institution, indicating that the number of children in a state of abandonment and poverty in the city was high. Probably, the institution did not attend all the underprivileged boys of the city32.

The workshops were diversified and operated in order to obtain results, in the sense of meeting some of the asylums' needs such as clothes and shoes. The purchase of machines seems to have been another investment made with the resources obtained by the services performed by the boarders in the professionalizing workshops, which, in the year 1886, totaled 11:638$44433.

The asylums solution, however, is not the alternative to account for the effects of the Free Womb Law, with a potential increase in the population's demands for schooling, especially when education is represented as a condition to overcome barbarism and achieve citizenship/civilization, an argument mobilized by several social agents.

Rui Barbosa, for example, in "Discursos Parlamentares Sobre a Emancipação dos Escravos" (Parliamentary Discourses on the Emancipation of Slaves), in the session of July 13, 1871, takes up José de Alencar's34 speech.

We want the redemption of our brothers, as Christ wanted it. It's not enough to say to the creature, hampered in his intelligence, crushed in his conscience: You are free; go; roam the fields like a beast! ....

No, gentlemen: it is necessary to enlighten the blunted intelligence, elevate the humiliated conscience, so that one day, when the moment comes to grant you freedom, we can say: You are men, you are citizens. We have redeemed you not only from captivity, but also from ignorance, vice, misery, animality, in which you were lying! (ALENCAR, apud BARBOSA, 1945, p. 77).

In the end, Alencar asks: "And how to free the captive, before educating him? Barbosa denounces the sophistry employed by José de Alencar who, through "seductive words", defended an impossible previous preparation. In this case, Alencar's rhetorical expedient was adopted to oppose the emancipation project, using as argument the State's incapacity to invest in the instruction of the ingenuous. In this logic, that of the slavocrats, it made no sense to liberate the unborn.

The education of the ingenuous and the (in)ability of the State to provide for the education of those born of the free belly became central to the debates of those who advocated in favor of the norm, as well as those who opposed it. In the 1871 session, an opponent spoke out on the matter, highlighting the limits of the State in issues related to the provision of services, treatment and education of the unborn:

Mr. Baron of Villa da Barra35 - I condemn the basis of the free womb, because the government cannot take charge of the upbringing, treatment, and education of these ingenuous in order to later lead them into society as free citizens with all their prerogatives and rights (ANAIS DA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS, July 11, 1871, p. 97).

The opposition used another argument to combat the project, drawing attention to the fact that the upbringing and education of the ingenuous would be under the responsibility of the slave owner, another facet of the argument of the inability of the State and Civil Society to respond satisfactorily to the freedom of the unborn.

Sr. Souza Reis36 - Therefore, the noble deputies can see that the repugnance that exists for the liberation of the womb is not because, as the noble deputy who preceded me said, the sordid interests of the slave owners are speaking to their souls, no; this is not the reason; but because the slave masters cannot, without sacrifices of all kinds, bear the heavy burden of raising and educating the children of such slaves, as free men, in the bosom of their farms, where they will live with their parents, siblings and many other slaves destined to work. (Supported by the minority).

This is the great inconvenience of this idea of the proposal (ANAIS DA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS, July 11, 1871, t. V, p. 76).

This deputy, however, tried to give greater visibility to the debate that took place inside the Chamber of Deputies, using the publication of his speech on the servile element, delivered on July 21, 1871. The speech of the deputy for the 1st district of the province of Pernambuco, in justification of his vote against the attempt to hasten the extinction of slavery, states that it could not be maintained in perpetuity, but that, at that juncture, such an act would bring about the ruin of the country. The arguments of risk, danger, ruin, and legality organize the Pernambuco parliamentarian's narrative, so as to modulate public opinion and reinforce the positions of the "stuck". At the end, as a synthesis of the position he embodies and defends, he points out:

If, however, the government wants to go further, and can overcome all the difficulties that will present themselves, then, respecting the constitutional principle, establish the means to raise and educate those born to slaves after the law, but leave the freedom to the masters to use this means to free those who generously want to be free, sending them to establishments created by the government.

The project under discussion, Mr. President, greatly alters the existing legislation with regard to the relationship between masters and slaves. (Seconded.)

This is a point on which the proposal is clearly worthy of all consideration, because it seems to me a great danger to alter the legislation in this respect.

Regarding the relations between masters and slaves, let's respect what exists; let's do what we want, if we can do it, if the government has the means to do it, if we can count on the guarantee of individual security and public tranquility, but let's not change the current legislation regarding the relations between masters and slaves (REIS, 1871, p. 30).

As we can see, one of the ways to oppose the emancipation project consisted in addressing the issue of the education of children born from the womb of enslaved women after the promulgation of the law, considering the limits of the government in offering services to this part of the population. What limits was the deputy from Pernambuco referring to? He was referring to two of them; the ability to indemnify and the reception of the ingenuous in proper institutions, as foreseen in the second article of the law.

Article 2 The Government may deliver to associations authorized by it, the children of female slaves, born since the date of this law, which are yielded or abandoned by their masters, or removed from their power in virtue of art. 1 § 6º.

§ 1º The said associations will have the right to free services for minors until the age of 21 years, and may rent these services, but will be obligated

1º To raise and treat the same minors;

2º To constitute for each one of them a fund, consisting of the quota that is reserved in the respective statutes for this purpose;

3º To find them, after the time of service, an appropriate placement.

§ 2º The associations that deal with the previous paragraph will be subject to the inspection of the Orphans' Judges, regarding the minors.

§ 3. The provision of this article is applicable to houses for exposed children, and to persons whom the Orphan Judges entrust with the education of these minors, in the absence of associations or establishments created for this purpose.

§ 4. The Government has the right to order the collection of these minors to public establishments, transferring in this case to the State the obligations that § 1 imposes on authorized associations (Law No. 2040 of September 28, 1871).

As can be seen, the creation of an institutional apparatus is foreseen to enroll the unborn in certain institutions and families/people to prevent the dangers of uselessness and ignorance. However, the problems arising from the conceptions of society and slavery were far from being settled.

The sharpening of positions does not imply the affirmation of an inaugural act, as if access to the literate universe was about to begin with those born of the free womb. The fear was of the intensity and of the alteration of the constituted order37. As recent studies have shown, portions of the black, freed, and even enslaved population had access to the world of letters. Some traces show that blacks and slaves participated in the schooling process, as we can see through an initiative that took place in the 1830s. Back in 1839 there was a literate slave, Cosme Bento das Chagas, known as the "emperor of freedom", who opened a school of first letters, located on the Yellow Lagoon farm, to teach 3,000 blacks who had run away from the farms or who had escaped from the slave settlements in the Codó region, in the Maranhão Province38. This occurrence indicates the existence of multiple forms of education and strategies of access to schooling and learning of letters by blacks and slaves throughout the eighteen hundreds (GONDRA; SCHUELER, 2008)39.

In the Court, the journal A Instrucção Pública (The Public Instruction), in 1873, provides other clues by reporting the education of slaves of both sexes, at the initiative of an owner:

Primary Instruction - We have been written: Mr. Commander Joaquim José de Souza Breves40, wealthy farmer from the province of Rio de Janeiro, has just ordered the establishment in his several farms of classes of first letters for the education of his slaves that where minors of both sexes (A INSTRUCÇÃO PÚBLICA, March 18, 1873, ed. 20, p. 160).

The experience of schooling slaves was developed in various ways, formal or informal. Two elements draw attention in this article. First, the fact that the landowner ordered to establish classes in several farms, which would increase the number of enslaved girls and boys instructed in first letters. Secondly, we can highlight the effect of the legislation passed two years earlier, an indicator of the landowner's willingness to comply with the law and maintain his extensive plantation, a guarantee of the riches obtained from the cultivation of the "black gold", a common way to refer to coffee.

It is worth remembering that there were other ways of inserting slaves into literate environments. In 1870, Policarpo Leão41 published a book with his conceptions about the slave element. In this publication, the author offers clues about the presentation of slaves' works in an exhibition in Rio de Janeiro in 1865: "In the exhibition, which took place in Rio de Janeiro in the year 1865, masters were rewarded, only because their slaves presented very good works, due to the slaves' talent and dedication". This information was used to support the six arguments he used in favor of the free classes42 (LEÃO, 1870, p. 9-10).

Newspaper advertisements of the time, on the other hand, constitute important sources to think about the education of blacks and the enslaved population in the 19th century, as pointed out by Lopes (2017, 2020) and Silva (2018). These authors located advertisements from various newspapers that indicated the existence of enslaved people who could read, write, and count. Some advertisements signal the existence of enslaved people who had trades, such as carpenter, tailor, and shoemaker. Other ads point to the existence of those who could translate French, as well as musicians.

In the printed materials of the late 1870s, it is possible to find the sale of slaves with their children (ingénues). An example can be read in the Jornal do Commercio, of 1877, in which it was announced:

For 1:500$, a black woman of 18 years, who irons perfectly, washes, sews, cooks with an oven and stove and makes sweets, with an ingenue of six months, and plenty of milk from the first birth: three little black girls of 14, 16 and 17 years, can iron clothes perfectly and of all service, at 1:300$, 1:400$ and 1:500$. Informed at Rua de S. Pedro (S. Peter St) n. 246 (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, January 1, 1877, ed. 1, p.1).

Six years after the Free Womb Law was promulgated, however, some landlord practices remained unchanged, such as the sale of female slaves and their children, freed by force of law. It is observed that the fact of having milk in abundance added value to the "product" to be sold, as they could serve as wet nurses for the owners' children or even be rented to fulfill this function.

In a reading of Dr. Alambary Luz's presentation speech in the Revista Instrução Pública (Public Instruction Magazine), Schueler points out that

In a society that was becoming progressively more complex, from the point of view of both ethnic-racial differentiations and the social conditions of its individuals, where the confusion between free, freedmen, and slaves was growing, especially in the largest urban centers, the editor-in-chief of the pedagogical journal perceived that the transformations that had occurred influenced the political direction of governments and, above all, claimed for new arrangements and new strategies for social ordering and control [. ...] it was clear that the development of education was directly related to the transformations resulting from the growing social complexity and the intensification of political, economic and social struggles in the 1870s - among them, the intensification of the debates about slavery and about the Law of September 28, 1871 (known as the free-birth law) and the consequent reformulation of the concepts and practices around labor (SCHUELER, 2005, p. 15).

It can be seen that there was a relationship between the social status of the individual, whether free, freed or slave, the political struggles and the education of this part of the population. The enslaved were legally excluded from the official education policies, although it is possible to see anti-disciplinary gestures, establishing other possible ones inside the formal interdiction.

In the 1880s, for example, some private individuals, especially those linked to the abolitionist movement, invested in the creation of schools for freedmen. At the same time, the printed press urged abolitionist associations to found schools as an important expedient to force and organize another tradition. As a result, abolitionists, clubs and associations created the night schools and free schools of popular instruction, such as the Club of Freedmen of Niterói, schools of first letters with abolitionist teachers, the Free Night School of Flowers Street and the Night School of Cancella (ALONSO, 2015).

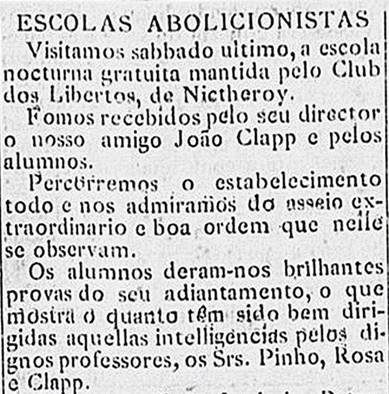

The Gazeta da Tarde newspaper of 1883 published an article about the visit made by José do Patrocínio43 to the Free Night School, maintained by the Clube dos Libertos de Niterói, created by João Fernandes Clapp44.

Source: Gazeta da Tarde (Evening Gazette). April 17, 1883, ed. 86, p. 1.

Image Translation:

ABOLITIONIST SCHOOLS

Last Saturday we visited the free night school maintained by the Freedmen's Club of Nictheroy.

We were welcomed by its director, our friend João Clapp, and by the students.

We walked through the whole establishment and admired the extraordinary cleanliness and good order that is observed there.

The students gave us brilliant proofs of their progress, which shows how well those intelligences have been directed by the worthy teachers, Mr. Pinho, Mr. Rosa and Mr. Clapp.

Figure 5 Gazeta da Tarde (Evening Gazette). Abolitionist Schools.

The note published in the Gazeta da Tarde45 advertises the Free Night School and the Freedmen's Club of Nictheroy. The latter institution was created by members of the abolitionist movement and had significant participation in the process of abolition of slaves.

The physical space and hygiene of the school were highlighted by the writer. These were aspects highlighted with great importance, because it was a time when the priority was to reform and build a country under the sign of civilization, which implied the adoption of a set of preventive measures, one of them being to keep the subjects, the city and environments clean and sanitized. Disorder, in turn, whether physical or moral, should be medically and scientifically combated (GONDRA, 2004).

The "intellectual advancement" of students was praised as another positive feature of the school, an element that determined the good quality of an institution designed to serve the poor and freedmen. In the sequence, the writer invites/convokes the population to contribute to the abolitionist causes:

Unite the abolitionist associations, found schools, and the regeneration of the homeland will be the faster the greater was the education of the people.

The preference of the pupils in these schools is a great proof that the slave, restored to society, did not leave the abyss of captivity to throw himself into another - ignorance.

They also want the light.

The memory of the visit we made will be eternal, and those who go to that school will find our names in the visitors' book, an honor we had when we engraved them on its pages (GAZETA DA TARDE, April 17, 1883, ed. 86, p. 1).

The writer makes a direct appeal to the collectives gathered in favor of abolition to found schools, in the register that the regeneration of the homeland had a direct and positive correlation with the education of the people. It was not enough just to leave the abyss of captivity. It was also necessary to overcome the abyss of ignorance. It is an argument that strongly articulates the two pairs, as a necessary condition to abolish the double bondage: that of slavery and that of ignorance. Initiatives, however, prior to the appeal of 1883 had already been put into practice in several provinces of the Empire, pointing to movements that attest to the participation of blacks, enslaved and freedmen in the literate culture, according to a survey organized by Alonso (2011).

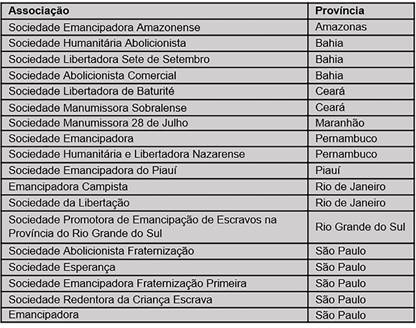

Source: Alonso, 2011, p. 176.

Image Translation:

Left Column:

Association

Amazon Emancipation Society

Abolitionist Humane Society

Libertadora Society September 7

Abolitionist Commercial Society

Baturité Liberating Society

Sobralian Manumissioner Society

July 28th Manumissioner Society

Emancipator Society

Nazarian Humane and Liberating Society

Emancipator Society of Piauí

Emancipator Society of Campista

Liberation Society

Society for the Promotion of the Emancipation of Slaves in the Province of Rio Grande do Sul

Abolitionist Fraternization Society

Hope Society

Emancipation Society Fraternization First

Redemptive Society of the Slave Child

Emancipator Society

Right Column:

Province

Box 1: Abolitionist Associations in Brazil - 1860 to 1871.

The abolitionist movement assumed a complex and heterogeneous configuration in Brazil, although they built a common agenda; the end of the serf element and the necessary formation of the freed population. According to Alonso (2011), the movement did not end with the achievement, partial, represented by the law of September 28, 1871. According to her, other collectives were created in the post-freedom period, with quite diverse tactics and profiles, resorting, for example, to flowers, votes and bullets, as well demonstrated in her study.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In this study, we observed that the actions of the public power in the process of freeing the enslaved were marked by moments of great instability. The complex disputes over the direction of the Brazilian Empire acted as a major obstacle in the process of approving the reform of the so-called Free Womb Law, Law No. 2040, signed on September 28, 1871. Considered a milestone in the process of abolishing slavery in Brazil, this measure is part of the set of actions that sought to minimize the effects of captivity in the Empire, such as the Euzébio de Queiroz Law (1850) and the Sexagenarians Law (1885).

The Free Womb Law declared free the children of enslaved women born in Brazil, as of the date of the law's approval. In addition, it determined that the children should remain in the possession of their mothers' masters, obliging them to raise them until they were eight years old. After this period, they could either hand the child over to the government, with the right to compensation, or use the services of the freeborn until the age of 21. In practice, it meant the gradual abolition of slavery, considering that it would be necessary to wait for the next generation, born in the country, for everyone to effectively attain freedom. The gradualism did not lessen the criticism of the abolitionists, who demanded the immediate and complete extinction of the servile element.

Politicians disputed among themselves, amidst the "order and disorder" of the plenary and society, the destiny of many lives. Merchants and farmers pressured the statesmen to legislate in such a way that they would not be harmed. For them, the reform should not be passed. In this way, they would maintain their commercial and financial control over the lives of the enslaved population. In this case, the defeat of the slaveholders was by a margin of 20 votes, 65 in favor and 45 against, which implied the opening of a new chapter in the history of slavery and the project of the end of captivity, even if from a gradualist perspective, as many reformists advocated.

In the 19th century, although in a residual way, reading and writing were present in the lives of a small part of the enslaved population, blacks, freedmen and ingénues. The abolitionist movement, as well as that of teachers and even of farmers, contributed for a fraction of the poor, black and enslaved population to have access to the literate world. It is important to realize that the fact that the public authorities prohibited the enrolment of enslaved people in official schools did not function as a complete obstruction, insofar as the condition of property and all the violence that this condition imposed on the enslaved did not prove to be sufficiently rigid to prevent access to and diffusion of literate culture for a part of this population. Chains, fetters, whips, stoning, pitchforks, pillorying, among other techniques of subjection, also coexisted with unexpected expedients, more or less visible insubordination that, in the end, favored the diffusion of elements of the written culture and of experiences of freedom, even if in a very unequal society, founded and nurtured by the institution of slavery.

From the evidence of our present, the sun of freedom has not yet been seen by many. For many others, with many restrictions. As Belchior registered, many still "have bled too much" and "cried for dogs". However, while acknowledging the deaths of "last year", he cultivates the hope of not dying anymore: "Last year I died, but this year I won't die"46. Hope, however, that comes up against the numbers of exclusion, imprisonment, and murder of black men and women, heirs of so much violence, routinely reported in Brazil and in other countries, not to mention what is not in the newspapers or even in alternative media47. Thus, by giving visibility to the strategies and experiences of part of the black population in the sphere of literate culture, we seek to call attention to undo generalizations and pernicious erasures and, at the same time, observe the actuality of an uncomfortable agenda that, in the end, denounces the limits of democracy and the equal dissemination of rays of light.

REFERENCES

A Instrucção Pública. Rio de Janeiro. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.bn.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

Academia Brasileira de Letras. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.academia.org.br/academicos/jose-de-alencar/biografia . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

Academia Brasileira de Letras. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.academia.org.br/academicos/machado-de-assis/biografia . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

ALENCAR, José de. Discursos proferidos na sessão de 1871 da Câmara dos Deputados. Rio de Janeiro: Tipografia Perseverança, 1871. [ Links ]

ALENCAR, José de. Câmara dos Deputados. 13 de julho de 1871 apud BARBOSA, Rui. Discursos Parlamentares Sobre a Emancipação dos Escravos. Obras completas de Rui Barbosa. Rio de Janeiro: MEC, 1945. Vol. XI, 1884, Tomo I. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://docvirt.com/docreader.net/DocReader.aspx?bib=ObrasCompletasRuiBarbosa&PagFis=4645 Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

ALONSO, Angela. Associativismo avant la lettre - as sociedades pela abolição da escravidão no Brasil oitocentista. Sociologias. Porto Alegre, ano 13, nº 28, p. 166-199, set./dez. 2011. [ Links ]

ALONSO, Angela. Flores, votos e balas: o movimento abolicionista brasileiro (1868-1888). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015. [ Links ]

ARANTES, Adlene. S. Colônia Orfanológica Isabel: uma escola para negros, índios e brancos (Pernambuco 1874-1889). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v. 9, n. 20, p. 105-136, 2009. [ Links ]

AZEVEDO, Celia Maria Marinho de. Onda negra, medo branco: o negro no imaginário das elites-século XIX. 2ª edição.São Paulo: Annablume, 2004. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Andreson Carlos Elias. O Instituto Paraense de Educandos Artífices e a morigerância dos meninos desvalidosna Belém da belle époque. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Universidade Federal do Pará, Pará, 2011. [ Links ]

BARRETO, Rozendo Moniz. Elogio Histórico: Jose Maria da Silva Paranhos. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. Universal de H. Laemmert,1884. Biblioteca digital luso-brasileira. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/handle/id/242468 . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BLAKE, Augusto Victorino Alves Sacramento. Diccionario Bibliographico Brazileiro. Rio de Janeiro. Conselho Federal de Cultura, 1970. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://digital.bbm.usp.br/handle/bbm-ext/22 . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Anais da Câmara dos Deputados. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www2.camara.leg.br/a-camara/documentos-e-pesquisa/diariosdacamara . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Anais do Senado. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.senado.leg.br/publicacoes/anais/asp/IP_AnaisImperio.asp . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição Politica do Imperio do Brazil (25 de Março de 1824). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao24.htm . Acesso em: 02 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto n. 1.331-A de 17 de Fevereiro de 1854. Reforma Couto Ferraz. Aprova o Regulamento para a reforma do ensino primário e secundário do Município da Corte. Disponível emDisponível emhttps://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1824-1899/decreto-1331-a-17-fevereiro-1854-590146-publicacaooriginal-115292-pe.html . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei 2.040, de 28 de setembro de 1871. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/handle/id/496715 . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 3.314, de 16 de Outubro de 1886. Fixa a Despesa Geral do Império para o exercício de 1886-1887 e 2º semestre do ano da 1887. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/leimp/1824-1899/lei-3314-16-outubro-1886-543171-publicacaooriginal-53205-pl.html#:~:text=Fixa%20a%20Despeza%20Geral%20do,1887%2C%20e%20d%C3%A1%20outras%20providencias . Acesso em: 02 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Projeto de Lei n. 10.391/2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.camara.leg.br/proposicoesWeb/fichadetramitacao?idProposicao=2178337 . Acesso em: 02 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Relatório do Ministro do Império. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.crl.edu/ . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Relatório Presidente de Província do Rio de Janeiro. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.crl.edu/ . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Maria Alice Rezende de. O quinto século. André Rebouças e a construção do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Revan: IUPERJ-Universidade Cândido Mendes, 1998. [ Links ]

CASTRO, Ramiro Berbet de. Histórico e descripção dos edifícios da Cadeia Velha, Palacio Monröe e Bibliotheca Nacional. Rio de Janeiro: Brasil Educação, 1926. [ Links ]

CERQUEIRA, Bruno da Silva Antunes de. D. Isabel I, a Redentora. Textos e documentos sobre a imperatriz exilada do Brasil em seus 160 anos de nascimento. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Cultural D. Isabel a Redentora, 2006. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Beatriz Rietmann da Costa. “Quem dá aos pobres, empresta a deus”: Apontamentos para uma história do Asylo dos Inválidos da Pátria. Revista Contemporânea de Educação. Rio de Janeiro. v. 4, nº 7, p. 26-42, 2009. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Marcus V. Educação e escravidão: um desafio para a análise historiográfica. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v. 2, n. 2 [4], p. 123-144, 2002. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Marcus V. A arte de construir o invisível: o negro na historiografia educacional brasileira. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v. 7, n. 1 [13], p. 11-50, 2007. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Marcus Vinícius; BARROS, Surya Aaronovich Pombo de(Orgs.). A história da educação dos negros no Brasil. Niterói: EdUFF, 2016. [ Links ]

FRANCHINI NETO, Helio. Independência e morte - Política e guerra na empacipação do Brasil (1821-1823). Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 2019. [ Links ]

Gazeta da Tarde. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.bn.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

GOMES, Marcelo Augusto Moraes. A Espuma das Províncias - um estudo sobre os Inválidos da Pátria e o Asilo dos Inválidos da Pátria, na Corte (1864-1930). 2007. 643f. Tese (Doutorado em História Social). Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas-USP. São Paulo, 2007. DOI: 10.11606/T.8.2007.tde-05072007-144427. [ Links ]

GONDRA, José Gonçalves. Artes de civilizar: medicina, higiene e educação escolar na Corte Imperial. 1ed. Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ, 2004. [ Links ]

GONDRA, José Gonçalves; SCHUELER, Alessandra Frota Martinez. Educação, poder e sociedade no Império brasileiro. 1ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

GONDRA, José Gonçalves. A emergência da escola. 1. ed.São Paulo: Cortez, 2018. [ Links ]

HOLANDA, Sérgio Buarque. O Brasil Monárquico: do Império à República. São Paulo: DIFEL/Difusão Editorial S.A. História Geral da Civilização Brasileira; t. 2, v.5. 1972. [ Links ]

Illustração Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.bn.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 01 jan 2021. [ Links ]

Jornal do Commercio. Rio de Janeiro. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.bn.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 01 jan 2021. [ Links ]

LE GOFF, Jacques. História e memória. Trad. Bernardo Leitão... [et al.] - Campinas. Editora da UNICAMP, 1990. [ Links ]

LEAL, Maria das Graças de Andrade. Educação e trabalho; raça e classe no pensamento de um intelectual negro. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v. 20, n. 1, p. e123, 2020. [ Links ]

LEÃO, Polycarpo Lopes. Como Pensa Sobre o Elemento Servil. Typographia Esperança. Rio de Janeiro, 1870. [ Links ]

LOPES, Katia G. Cordeiro. A presença de negros em espaços de instrução elementar da cidade-corte: o caso da Escola da Imperial Quinta da Boa Vista. 2012. 138f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Políticas Públicas e Formação Humana). Faculdade de Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2012. [ Links ]

LOPES, Kátia G. C. Escravizados letrados nos anúncios do Diário do Rio de Janeiro (1821-1829). In: Anais IXSeminário Internacional Redes Educativas e Tecnologias. Rio De Janeiro/UERJ/Proped, 2017. [ Links ]

LOPES, Kátia G. Cordeiro. “Dai-lhes mestres e dai-lhes officinas”: O acesso de negros livres, libertos e “sujeitos de pés descalços” à cultura letrada no Rio de Janeiro oitocentista, Rio de Janeiro. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2020. [ Links ]

LOPES, Luiz Carlos Barreto. Projeto Educacional Asilo de Meninos Desvalidos: Rio de Janeiro (1875-1894) - uma contribuição à história social da educação no Brasil. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1994. [ Links ]

LOURENÇO, Thiado C. P. O Império dos Souza Breves nos Oitocentos: Política e escravidão nas trajetórias dos Comendadores José e Joaquim de Souza Breves. 2010. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) -Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, 2010. [ Links ]

LYRA, Tavares. Instituições Políticas do Império. Brasília. Editora Universidade de Brasília, 1978. [ Links ]

MAC CORD, Marcelo; ARAÚJO, Carlos Eduardo; GOMES, Flávio(orgs). Rascunhos cativos: educação. Escolas e ensino no Brasil escravista. Rio de Janeiro: 7 letras, 2017. [ Links ]

MARQUES, Jucinato de Serqueira. Os desvalidos: o caso do Instituto Profissional Masculino (1894-1910). Uma contribuição à História Social das instituições educacionais da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. 1996. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1996. [ Links ]

NABUCO, Joaquim. A escravidão. SILVA, Leonardo Dantas (Org.). Recife: FUNDAJ - Editora Massangana, 1988. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/download/texto/jn000061.pdf Acesso em: 01 jan 2021. [ Links ]

NABUCO, Joaquim. Um Estadista do Império - Nabuco de Araujo - sua vida, suas opiniões, sua época. Tomo III (1866-1878). Rio de Janeiro: Ed. H. Garnier, Livreiro-Editor. (1899). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/item/id/179441 . Acesso em: 01 jan 2021. [ Links ]

NARCIZO, Rodrigo Mota. Educação destinada a habilitar os educandos a serem bons defensores da pátria”. Objetivos e práticas pedagógicas da Escola Premunitória 15 de novembro. Anais IIICongresso Brasileiro de História da Educação, 2004. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.sbhe.org.br/novo/congressos/cbhe3/Documentos/Individ/Eixo3/196.pdf . Acesso em: 01 jan 2021. [ Links ]

NASCIMENTO, Fátima Aparecida do. “Porta de todas as inteligências e carreiras”: Instrução, Trabalho e Ciência no Ministério de João Alfredo Corrêa de Oliveira (1870-1875). 2016. 306f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2016. [ Links ]

PASCHE, Aline et al.. ‘Pela iluminação do passado’. Livros e educação no contexto do Cinquentenário da Independência (capital brasileira, década 1870). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v. 20, n. 1, p. e126, 2020. [ Links ]

NORA, Pierre. Entre memória e história: a problemática dos lugares. São Paulo: Projeto História, nº. 10, p. 7, 1993. [ Links ]

PAVÃO, Eduardo Nunes Alvares. “O Asylo de Meninos Desvalidos (1875-1894): Uma instituição disciplinar de assistência à infância desamparada na Corte Imperial”. XXVIII Simpósio Nacional de História, 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://encontro2014.rj.anpuh.org/resources/anais/27/1364660408_ARQUIVO_Infanciadesvalida.pdf . Acesso em: 01 jan 2021. [ Links ]

PERES, Eliane. Sob(re) o “silêncio das fontes”... A trajetória de uma pesquisa em história da educação e o tratamento das questões étnico-raciais. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v. 2, n. 2 [4], p. 75-102, 2002. [ Links ]

PINTO, Ana Flávia Magalhães A Gazeta da Tarde e as peculiaridades do abolicionismo de Ferreira de Menezes e José do Patrocínio. AnaisXVIIISimpósio Nacional de História. Florianópolis, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://anpuh.org.br/uploads/anais-simposios/pdf/2019-01/1548945029_4dcf197cc369bb8fa8b106751ecf5a1f.pdf . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

REIS, Eliane de Mesquita Sabino. “Tornar-se útil a si e aos outros”: a Escola Quinze de Novembro (Rio de Janeiro - 1899-1925). Monografia. Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Faculdade de Educação, 2019. [ Links ]

REIS, Joaquim de Souza. O elemento servil em 21 de julho de 1871. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia Villeneuve & Cia, 1871. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/bitstream/handle/id/242837/000560430.pdf?sequence=1 . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

Revista Illustração Brasileira. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.bn.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 02 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

RIZZINI, Irma. A pesquisa histórica dos internatos de ensino profissional: revendo as fontes produzidas entre os séculos XIX e XX. Rio de Janeiro: Revista Contemporânea de Educação, v. 4, n. 7, 2009. [ Links ]

SÁ NETTO, Rodrigo de. A Secretaria de Estado dos Negócios do Império (1823-1891). Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Nacional. Memória da Administração Pública Brasileira, 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.arquivonacional.gov.br/images/virtuemart/product/A-Secretaria-de-Estado-dos-Neg%C3%B3cios-do-Imp%C3%A9rio.pdf . Acesso em: 01 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Felipe, GONDRA, José; LOPES, Kátia. Forma(ta)r o povo, plasmar a nação: acordos, desconcertos, atravessamentos (1823-1827). In: LIMEIRA, Aline SILVA; Edgleide GONDRA, José(orgs). Independência & Instrução no Brasil: História, memória e formação (1822-1972). Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ (no prelo). [ Links ]

SANTIAGO, Bruna Oliveira. Cultura visual e imprensa no século XIX: um estudo das imagens da escravidão na Semana Illustrada. XVIISimpósio Nacional de História. Natal, 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.snh2013.anpuh.org/resources/anais/27/1371310780_ARQUIVO_CulturavisualeimprensanoseculoXIX_corrigido.pdf . Acesso em: 01 jan 2021. [ Links ]

SCHUELER, A. F. M. A Imprensa Pedagógica e a Educação de Escravos e Libertos na Corte Imperial: impasses e ambigüidades da cidadania na revista Instrução Pública (1871-1889). Cadernos de História da Educação (UFU), nº. 4, p. 13-25 - jan./dez. 2005. [ Links ]

SCHUELER, A. F. M.; TEIXEIRA, Giselle. Educar os Pobres e os Negros: Representações, Práticas e Propostas de Educação na Imprensa Periódica na Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (1870-1889). Revista Eletrônica Documento/Monumento, v. 15, p. 135-145, 2015. [ Links ]

SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. O Império em Procissão: ritos e símbolos do Segundo Reinado. Rio de Janeiro. Ed. Jorge Zahar. 2001. [ Links ]