Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 06-Nov-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469826560

ARTICLE

AFFECT/ SOCIALLY SITUATED COGNITION/CULTURES/LANGUAGES IN USE (ACCL) AS A UNIT OF ANALYSIS OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

1 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Federal University of Minas Gerais) (UFMG). Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. mafa@ufmg.br ou mafacg@gmail.com.

2 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Federal University of Minas Gerais) (UFMG). Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. vfaneves@ufmg.com.

This article aims to discuss the theoretical and methodological discussion of the cultural development of infants and young children through the method of Unit of Analysis from the point of view of Cultural-Historical Theory in dialogue with Ethnography in Education. This dialogue, in which one approach interrogates and extends the other, has enabled the construction of a synthesis of interpretation of the classrooms as an indivisible totality - the unit of analysis [affect/socially situated cognition/cultures/languages in use] (ACCL). We start from the assumption that affections are the essence of the human, that from them derives our cognition, our capacity to know what is produced as cultures, by semiotic mediation, by languages in use, in social situations of development. It is fundamental to say that these concepts act dialectically, opposing each other and, at the same time, constituting each other. Only on the basis of a dialectical logic that admits internal contradictions between objectification and individual appropriation of cultures could this unit of analysis be thought out and put into practice in our research. Thus, our focus is on understanding what affects babies and young children in the sense of creating something new in their development, considering that the language of the human person is not only constituted in orality, but also in other manifestations, such as gestures, facial expressions, body movements, among others. Thus, babies and small children have bodies that speak, feel, think, and play, producing meanings for the world.

Keywords: Unit of Analysis, Cultural-Historical Theory, Ethnography in Education; Socially Situated Cognition; Affect

ste artigo tece uma discussão teórico-metodológica acerca da compreensão do desenvolvimento cultural de bebês e crianças pequenas por meio do Método da Unidade de Análise do ponto de vista da Teoria Histórico-cultural em diálogo com a Etnografia em Educação. Este diálogo, em que uma abordagem interroga e amplia a outra, possibilitou a construção de uma síntese de interpretação das salas de atividades como uma totalidade indivisível - a unidade de análise [afeto/cognição social situada/culturas/linguagens em uso] (ACCL). Partimos do pressuposto de que os afetos são a essência do humano, que deles deriva nossa cognição, nossa capacidade de conhecer o que se produz como culturas, pela mediação semiótica, pelas linguagens em uso, em situações sociais de desenvolvimento. É fundamental dizer que esses conceitos atuam dialeticamente, uns se opondo aos outros e, ao mesmo tempo, constituindo uns aos outros. Somente com base em uma lógica dialética que admite contradições internas entre a objetivação e a apropriação individual das culturas é que essa unidade de análise pôde ser pensada e colocada em prática em nossas pesquisas. Dessa forma, nosso foco está em compreender o que afeta os bebês e as crianças pequenas no sentido de se criar algo novo em seu desenvolvimento, considerando que a linguagem da pessoa humana não se constitui apenas na oralidade, mas também em outras manifestações, como nos gestos, nas expressões faciais, na movimentação corporal, dentre outros. Assim, bebês e crianças pequenas possuem corpos que falam, que sentem, que pensam, que brincam produzindo sentidos para o mundo.

Palavras-chave: Unidade de análise, Teoria Histórico-cultural, Etnografia em Educação; Cognição social situada; Afeto

Este artículo hace una discusión teórico-metodológica acerca de la comprensión del desarrollo cultural de bebés y niños pequeños por medio del Método de la Unidad de Análisis desde el punto de vista de la teoría Histórico-cultural en diálogo con la Etnografía de la Educación. Este diálogo en el que un abordaje interroga y amplía al otro, posibilitó la construcción de una síntesis de interpretación de las salas de actividades como una totalidad indivisible - la unidad de análisis [afecto/cognición social situada/culturas/lenguajes en uso] (ACCL). Partimos del presupuesto de que los afectos son la esencia de lo humano, que de ellos deriva nuestra cognición, nuestra capacidad de conocer lo que se produce como culturas, por la mediación semiótica, por los lenguajes en uso, en situaciones sociales de desarrollo. Es fundamental decir que esos conceptos actúan dialécticamente, unos oponiéndose a otros y, al mismo tiempo, constituyendo unos a los otros. Solamente, con base en una lógica dialéctica que admite las contradicciones internas entre la objetivación y la apropiación individual de las culturas es que esa unidad de análisis puede ser pensada y colocada en práctica en nuestras investigaciones. De esa forma nuestro foco está en comprender lo que afecta a los bebés y a los niños pequeños en el sentido de crear algo nuevo en su desarrollo, considerando que el lenguaje de la persona humana no se constituye apenas en la oralidad, sino, también, en otras manifestaciones, como en los gestos, en las expresiones faciales, en el movimiento corporal, entre otros. Así, bebés y niños pequeños cargan cuerpos que hablan, que sienten, que piensan, que juegan produciendo sentidos para el mundo.

Palabras clave: Unidad de Análisis; Teoría Histórico-cultural; Etnografia de la Educación; Cognición social situada; Afecto

INTRODUCTION

What should we analyze in order to understand the cultural development of infants and young children? The Cultural-Historical Theory helps us to answer this question through the concept of unit of analysis (VIGOTSKI, 1931/1995b). Thus, some questions concern us: What is a unit of analysis from the Cultural-Historical Theory point of view? What are the implications of investigating units of analysis, in contrast to an analysis by elements, for a research program that proposes to understand the process of cultural development of a group of infants and toddlers? These questions reveal the path built individually and collectively throughout our investigations, in a dialogue between Cultural-Historical Theory and Ethnography in Education. Such dialogue, in which one approach questions and extends the other, enabled the construction of a synthesis of analysis and interpretation of the classrooms as an indivisible totality - the unit of analysis [affect/ situated social cognition/cultures/ languages in use] (ACCL) (GOMES, 2020).

Initially, we will briefly introduce the research program "Childhood and Schooling". Next, we will explain the concepts of cultural development and social situation of development, as well as the unit analysis method proposed by Vygotsky (1932/2018). Finally, we will discuss the unit of analysis ACCL.

RESEARCH PROGRAM: CHILDHOOD AND SCHOOLING

The longitudinal research program "Childhood and Schooling" aims to understand the process of cultural development of a group of twelve infants and toddlers from the moment of their entry into the Municipal School of Early Childhood Education Tupi (EMEI Tupi) in 2017 until they move to elementary school in 2022. The program is developed through research projects that focus on unique themes that make up the experiences (perizhivanya1) of these babies, such as the entry process in the EMEI Tupi, the imitation processes, the construction of the autonomy of psychomotor movements, imagination and play, literacy practices, the constitution of subjectivity, the curriculum experienced in this context, friendship relations, and experiences with cultural artifacts.

The monitoring of the class is done by the researchers of the group, based on Ethnography in Education and on the Cultural-Historical Theory, by means of participant observation, field notes, and, mainly, filming. Of the two hundred school days each year, we observed 42% in 2017, 35% in 2018, and 43% in 2019. In 2020, class observation was interrupted in March due to the pandemic caused by COVID-19. We remained in the class between 7:30 am and 5 pm on most of the 227 days observed. The empirical material of the Program consists of 904 hours of videorecords, photographs, three notebooks with field notes standardized by the research group, and the individual field notebooks of each researcher.

We briefly point out that the filming happened from the beginning to the end of all the days observed, being essential for the historical follow-up of the infants and toddlers' cultural development process. Filming allows "collecting, archiving, retrieving, and analyzing ethnographic records to construct accounts of everyday classroom life" (BAKER; GREEN and SKUKAUSKAITE, 2008, p. 77).

We outline some principles that guide the theoretical and methodological procedures adopted in a dialogue between Cultural-Historical Theory and Ethnography in Education. One of these principles refers to the fact that the elaboration of research problems and the method are developed together (SPRADLEY, 1980; CORSARO, 1985: ZANELLA et al., 2007, among others). Thus, specific issues, not initially foreseen, emerged from the empirical work. For example, it was possible to follow the genesis of singing games in the classroom (SILVA and NEVES, 2020), as well as the relations between reading, writing and subjectivity in this context (NEVES, GOMES and DOMINICI, 2021), among other issues. It becomes evident the need to study the higher psychological functions in their initial stage, or rather, in their genesis (FONTES et al., 2019).

Another principle refers to the fact that the fieldwork is conducted in a sustained and engaged manner (CORSARO, 1985), over a long period of time, in search of an explanatory and analytical description, or a "thick description", in the terms of Geertz (1989, p. 17). Through the logic of ethnographic research, it is possible to seek an understanding of the community through the point of view of its members and to describe the interpretations they give to the events that surround them, i.e., an emic perspective (which takes into account the point of view of the research participants) and an ethical perspective on the part of the researchers. Ethics in research with infants and young children implies the construction of an unconditional respect for the Other (NEVES and MÜELLER, 2021). There is an explicit recognition that the lives of the people (teachers, babies and families) we follow are unrepeatable and that we have the privilege of experiencing rich and diverse moments with them. An ethical issue that presents itself poignantly concerns the interpretation of events and, in particular, the actions and speech of infants and young children. Drawing limits to what is possible to be interpreted becomes fundamental, once the ways of communication and construction of meanings throughout the experiences at EMEI Tupi are not always accessible to the researchers. In this sense, there is an incessant search for a sensitive look to what is possible, or not, of interpretation.

A fourth principle refers to the relations between the researched people's points of view and the social-historical context in which these groups are inserted. Corsaro (1985) considers as one of the fundamental aspects of ethnography the fact that it is microscopic and, at the same time, holistic. That is, there is an explicit intention to relate the observed events to the broader context, recognizing that interactions between subjects are marked by "encounters between the local and the global" (STREET, 2003). In fact, the aim here is to understand, from different perspectives, the process of cultural development in a context of collective care and education and, equally, to understand some aspects of the world in which babies, teachers and families share their experiences. In this sense,

All and any human activity that is the focus of psychological investigation requires, for its understanding and explanation, a look at the meanings that they have for the people in relation, a look that considers the inseparability of the person from its conditions of possibilities and the historical reality of the context in which they actively participate (ZANELLA et al., 2007, p.31).

Associated with the understanding of the historical and social reality of the context where babies, teachers and their families are - sociogenetic analysis (GÓES, 2000) -, a micro genetic analysis is carried out, that is, "a detailed analysis of a process in order to configure its social genesis and the transformations of the course of events" (GÓES, 2000, p. 11. Emphasis added). The micro genetic analysis implies the method of the unit of analysis that, in turn, requires "to detach from the integral psychological whole certain features and moments that preserve the primacy of the whole" (VYGOTSKI, 1931/1995a, p. 99-100). We will explain the relevance of this method in the next section, as well as discuss, in the third section of this article, the dialectical interweaving of the concepts affect, socially situated cognition, cultures, and languages in use.

CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AND THE SOCIAL SITUATION OF DEVELOPMENT: CONCEPTS INTERTWINED BY EXPERIENCES

We consider the child as a social being that becomes an individual in a historical, dialectical, and discursive process. This individual being, which is social, becomes human, singular, in the process of culturally developing, in the relationship with other humans in a path that is neither linear nor progressive. We assume, together with Vygotsky (1932/2018), that this development is complex, contradictory, and presents moments of evolutions, involutions, and revolutions. In order to become development, something new needs to emerge (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p.33), there is a cultural metamorphosis, which is not given by birth. In this process, the biological and the cultural unify. Thus,

The development of the child is a process of constitution and emergence of man, of the human personality, which is formed through the uninterrupted appearance of new particularities, new qualities, new traits, new formations that are prepared in the preceding course of development and are not present, already ready, in small and timid sizes, in the previous steps (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p.35).

But, how to study this development? For Vygotsky (1932/2018), one must construct a method of studying child development that is premised on "the study of the unity of development; [this study] covers not just one aspect of the organism, of the child's personality, but all aspects of one and the other" (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 37/38). This implies the "decomposition of the complex whole into distinct moments that constitute and form it." (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 38). Therefore, the method of unit of analysis is not a method that adopts the analysis of decomposition into elements, into elementary constituent parts that are unrelated to each other and form the whole as a summation. For Vygotsky (1932/2018), there is a fundamental dialectical tension in this method, since it is defined by the contradiction of the unit of analysis being, on the one hand, part of a whole and, at the same time, containing essential characteristics of the whole. This analysis in units does not represent a generalization, but "can explain different properties of a complex totality" (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 41) and requires establishing the relationships between the parts and the whole. Thus, it is at the collective level that the individual contributions of children, not just teachers, affect the nature and direction (CASTANHEIRA, 2004) of infants' and young children's cultural development.

The analysis of child development in units presupposes that, in addition to being descriptive of symptoms (external characteristics of development), it is also explanatory, that is, "in interpreting the symptoms, by contrasting them, we must arrive at the developmental processes that cause them" (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 49). This specificity of the method of analyzing the units of child development had a "comparative genetic character" (Vigotski, 1932/2018, p. 53). That is, since we cannot observe the development of the child's mind itself, "we can only compare [contrast] the development of his mind at this instant and six months from now, then another six months and another six months" (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p.53). To carry out this analysis, we used the methodology of longitudinal, holistic, contrastive, and ethnographic research. We prefer the use of the term contrasts, and not the use of comparisons, in order not to hierarchize the different singular manifestations of children's development, nor to establish a single standard of development that could lead us to establish superiorities and inferiorities among children.

Therefore, we study the cultural development of infants and young children through the method of the unit of analysis in a global, analytical, contrastive genetic way, in the sense of studying the developmental processes that underlie the different ages, allowing us to clarify the path a child takes from one stage to another. Thus, we explicit similarities and differences in these paths, because, if we only present similarities, we will be in "search of the 'same', which erases change, the becoming, evolution, and leads to reductionism in one sense or the other. If, on the contrary, we recognize only the differences, we will have the irreducible singularity and no more knowledge will be possible" (THONG, 2007, p.11).

According to Veresov and Fleer (2016), "a dialectical and holistic understanding requires a logic of analysis by units and their intrinsic relationships to the whole, rather than a logic of mechanical interactions between elements." (p. 331/332). Such an understanding underlies the Vygotskian argument that the higher psychological functions, cultural in origin, products of the historical development of human beings, do not appear in social relations, but as social relations. Therefore, "what is internalized from social relations are not the material relations, but the meaning they have for people" (SIRGADO, 2000, p.66). Thus,

Vygotsky establishes a relationship of equivalence, not identity, between social relations as structures of society and social relations as the social structure of personality. It is a difference not of nature, but of mode of operation according to whether it is a matter of relations of the person in the public, interpersonal world, or in the private, personal world (SIRGADO, 2000, p. 16).

It is possible to understand that if these functions appear as social relations, transformations occur in the relations between the higher psychological functions. Therefore, the development process provokes not only the emergence of qualitatively new results, but a new structure of functions that indicates a systemic reorganization (FONTES et al., 2019).

In this sense, we can think of the dialectical unity [speech/thought] that forms a system of senses and meanings of words (MAHN, 2019). One function transforms into the other, no longer being just speech and thought organized in isolation. The word, as a concept, modifies itself, carries generalization, which is a property of thought; in turn, thought restructures itself through speech. Therefore, transformation occurs both in speech and in thought, and they are no longer separate elements. A system of senses and meanings of the word is formed, a complex dialectical unit of child development, promoting the emergence of something new in this development.

However, from the point of view of the Cultural-Historical Theory, development can only happen in a social situation of development, when the higher psychological functions (logical or artificial memory; voluntary attention, speech, thinking, imagination, etc.) appear as social relations, providing the description and explanation of something new in child development. In other words, the higher psychological functions are initially social relations that become psychological functions. The higher psychological functions constitute the social relations that, when appropriated by the children, are transformed into higher psychological functions of each of them, one constituting the other in the social situations of development.

The social situation of development can be understood as the environment in which the child lives; more precisely, we are interested in knowing the role and significance of this environment in her development. In the beginning of children's lives, the womb is their privileged environment, which expands at birth, articulating itself around narrow spaces, such as their room, or collective room, depending on the family's choice or the conditions imposed by the social situation in which they are born; passing to the other rooms of the house, to other family and friends' houses, and, in the case of the infants and toddlers in our research, the EMEI Tupi. Thus, at each age group, the social development situation changes, because what counts is not only the environment itself, but the relationship children produce with it. As changes occur in children, the environment also changes, constituting children's experiences, "that is, it is not this or that moment, taken independently of the child, that can determine its [environment] influence on later development, but the moment refracted through the child's experience" (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p.75).

This implies recognizing that the same social development situation can be experienced differently by each of the children in the classrooms, and that it is necessary to

To be able to find the relationship between the child and the environment, the child's experience, how he/she becomes aware, gives meaning, and relates affectively to a certain event. Let us say that this is the 'prism' that defines the role and influence of the environment in the development of the child's character, in his psychological development, and so on (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 77. Emphasis added).

From this perspective, the experience is a unit of analysis,

(...) in which one represents, in an indivisible way, on the one hand, the environment, what one experiences - the experience is always related to something that is outside the person - and, on the other hand, how I experience it [...] it is important to know not only which are the constitutive particularities of the child, but which of them, in a given situation, played a decisive role in defining the child's relation to a given situation, while in a different situation, other [particularities] did so (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 78).

Therefore, when investigating the child's relations with the social situation of development, we argue that her changes and reactions will depend on the particularities of each one, on how they affectively relate to the situation, as well as on their level of understanding, of becoming conscious, of attributing meanings to what happens in that situation.

The process of attributing meanings to what happens in the environment necessarily implies the development of the meaning of words, since we relate to people through the mediation of speech (or the mediation of sign language or tactile language). At each age, meanings change, depending on the child's degree of awareness of these meanings, which carry with them the affective and cognitive marks of the culture and languages in use in the various social situations of development. In this sense, generalizations must be made, which, in the case of babies, are not generalizations as concepts in themselves, but of a more concrete, visual and factual character (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018). Thus, to understand the meanings attributed by the child to her experiences, it is necessary to analyze the social situation of development

(...) as a source of development for the forms of activity and the higher characteristics specifically human, [...] because it is in the environment that exist the characteristics historically developed and the peculiarities inherent to man by virtue of his heredity and organic structure. They exist in every man because he is a member of a social group, is a historical unit living at a certain time and under certain historical conditions (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 90).

However, the development of the child does not repeat the preceding historical development of the human being (phylogenesis and sociogenesis), because in ontogenesis, children live with adults and other children. It is in living with others that they will be able, for example, to obtain the final or ideal forms of speech development, enabling them to appropriate what was once a form of relationship with the environment as a social relationship, a form of collaboration with other people, and transform speech into their internal heritage, into individual internal functions, that is, into higher psychological functions. Such functions arise from speech as a means of relation, from the externalized activity that took place between the child and other people. This research assumes, therefore, the micro genetic character.

According to Oliveira (2009), Vigotski talks about four genetic domains that interact in the formation of the psychism: phylogenesis, ontogenesis, sociogenesis, and micro genesis (p. 42/43). Wertsch (1985, p. 55) argues that Vigotski, in line with H. Werner's studies, identified two types of micro genesis. The first of these pertains to the formation of psychological processes in the short term, which would require repeated observations of the person in performing certain tasks. The second type of micro genesis is the unfolding of a conceptual or perceptual act over the course of a fraction of a second. Gomes (2020), based on Vigotski and Luria (1996) and Oliveira (2009), argues that

Vigotski dedicates himself to this fourth genetic domain before he died, by rejecting the determinist view of human development, both biological and cultural, and thus seeks to understand the idiosyncrasies, the unexpected, the particularities of each cultural group or cultural community, approaching the anthropological studies of his time (GOMES, 2020, p. 42).

Thus, we justify our focus on micro genesis: "micro" because our focus is on a thorough analysis of the cultural development of 12 infants/toddlers; and "genetic" because we seek to understand these developments as processes whose origin and transformations need to be understood historically, dialectically, and discursively. Our gaze is focused on the particularities of each infant/toddler, avoiding both the biological and the cultural determination of these developments (OLIVEIRA, 2009; GÓES, 2000). In the words of Vygotsky (1931/1995a, p. 64): "in recent years [the 1930s, 20th century], psychology has overcome its fear of the everyday appreciation of phenomena and has learned through insignificant minutiae to discover how the great is manifested in the small".

In the next section, we will discuss the dialectical unit [affect/socially situated cognition/cultures/languages in use] (ACCL), fundamental to the micro genetic analysis we undertook. The ACCL unit, therefore, is a theoretical-methodological synthesis that guides our investigations of the children's cultural development processes at EMEI Tupi.

[AFFECT/ SOCIALLY SITUATED COGNITION/CULTURES/LANGUAGES IN USE] (ACCL)

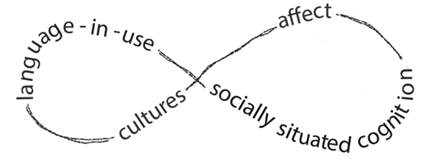

The anchoring in the Cultural-Historical Theory in dialog with Ethnography in Education allowed us to build the synthesis of analysis and interpretation of the cultural development of the 12 infants/toddlers at EMEI Tupi: the dialectic unit [affect/socially situated cognition/cultures/ languages in use] (ACCL). We elaborated this unit of analysis because it allows us to understand the child in her totality and singularities, in line with Vygotsky's search for an understanding of the relations between higher psychological functions in a complex system. Therefore, it is not about taking these dimensions as isolated elements; but, on the contrary, they constitute an indivisible unit, as represented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 seeks to explain the inseparability of the dimensions that make up the ACCL unit. We understand that the starting point of child development are the emotions, that is, the emotional relationships established with the social situation of development. We argue, based on Wallon (2008), that the construction of the person and of knowledge begins in the affective or emotional period, when "affectivity is practically reduced to the physiological manifestations of emotion, which is, therefore, the starting point of the psychism" (DANTAS, 1992, p. 85). Thus, "this beginning of the human being by the affective or emotional stage, which incidentally corresponds so well to the total and prolonged imperiousness of his childhood, directs his first intuitions towards others and places sociability in the foreground" (WALLON, 2008, p. 120) - constituting what we call specifically human. Through the bodily manifestations of emotions, in a socially and situated situation of development in the family and school environments, we constitute people with possibilities to think, speak and understand the world. According to Wallon (2008), the psychogenesis of motor skills (motor is always synonymous with psychomotor) is confused with the psychogenesis of the person - "reason is born from emotion and lives from its death" - and it is this paradox that constitutes the human being through the transformation of "emotion into intellectual activation" (DANTAS, 1992, p. 86).

According to Dantas (1992), for Wallon, "emotional activity is complex and paradoxical: it is simultaneously social and biological in nature; it performs the transition between the organic state of being and its cognitive, rational stage, which can only be achieved through cultural mediation, that is, social" (WALLON, 1972, apud DANTAS, 1992, p. 85). Thus, for Wallon (1959)

Affective consciousness is the form through which the psychism emerges from organic life: it corresponds to its first manifestation. Through the immediate bond that it establishes with the social environment, it ensures access to the symbolic universe of culture, elaborated and accumulated by men throughout their history. In this way, it is she who will allow the possession of the instruments with which cognitive activity works. In this sense, it gives rise to it (WALLON, 1959, apud DANTAS, 1992, p. 86).

The body manifestations of emotions in babies and small children are the starting point that affects and binds people, enabling them to access the symbolic universe of culture. Spinoza's (1991) elaborations about the human body help us in this understanding. Chauí clarifies the conception of human body for this author:

What is the human body? [...] It is a structured unit: it is not an aggregate of parts, but a unity of the whole and balance of interconnected internal actions of organs, therefore it is an individual. Above all, it is a dynamic individual, because the internal balance is obtained by continuous internal changes and continuous external relations, forming a system of centripetal and centrifugal actions and reactions, so that, by essence, the body is relational: it is constituted by internal relations between the organs, by external relations with other bodies, and by affections, that is, by the ability to affect other bodies and be affected by them without destroying itself, regenerating itself with them and regenerating them. The body, a complex system of internal and external movements, presupposes and places the interbodyness as origin (ESPINOSA, 1991, apud CHAUÍ, 1995, p. 54 italics are ours).

According to Chauí (1995), when arguing for the body as an individual and, at the same time, relational, constituted by internal relations among organs and external relations with other bodies and by affections, Espinosa (1991) criticizes the Cartesian idea of substantial union, as well as the Platonic idea of the soul as a ‘pilot’ of the body and the Aristotelian conception of the body as organ of the soul, that is, the soul as the body's leader and the body as the soul's instrument. For Spinoza, body and soul are not in a hierarchical command relationship. "Body and soul are isonomic, that is, they are under the same laws and under the same principles, expressed differently" (CHAUÍ, 1995, p. 58). Espinoza (1972) refuses the idea of faculties of the soul, stating that "the soul is, therefore, thinking activity that is realized as imagination, will, and reflection" (idem, p. 58). In the words of Espinoza (1991),

We are the unity of a corporal complex (the thousands of bodies that constitute our body) and a psychic complex (the innumerable ideas that constitute our mind or soul). [...] The soul is then defined as the consciousness of the affections of its body and the ideas of these affections; it is consciousness of the body and consciousness of itself. The use of the word constitute, leads to the understanding that it is in the nature of the soul to be internally connected to its body because it is activity of thinking it (either through imaginative ideas, through reflective ideas, or through desires) and it [body] is the object thought (imagined, conceived, understood, desired) by it [soul]. The connection between soul and body is not something that happens to both, but is what both are when they are human body and soul. The soul is the idea of the bodily affections (ESPINOSA, 1991, apud CHAUÍ, 1995, p. 60. Our emphasis).

In this way, we reiterate that when we elaborate the ACCL unit, we are considering "the human body and soul" that are not in connection, but that are one. Thus, there is no way to understand the cultural development of infants/toddlers without considering that it is through bodily affections (emotions, desires, imagination, will, will) that the human being is mobilized towards someone or something since the first days of life, because they essentially depends on the other to survive. In those first days, and throughout the first year of life, "most motor manifestations will consist of gestures directed at people (appeal): manifestations, now full of nuances, of joy, surprise, sadness, disappointments, expectation, etc." (DANTAS, 1992, p. 39).

In its first year of life, the baby's emotional communication is its main activity, in which the "affective perception, that is, emotions and perception are still undifferentiated from each other" (VIGOTSKI, 1932/2018, p. 99). This emotional communication relates to a first systemic formation of human consciousness in which the baby perceives those other cares for him (TOASSA, 2006, p. 73). It will be in the relationship with cultures, with people, that children and babies will differentiate themselves and in the following years other functions, such as memory, attention, speech and thought, will gain predominance in child development, coexisting with each other, constituting themselves mutually.

In this sense, the incompleteness of the human being leads Wallon (2008) to state that we are organically social beings, that is, the human being, to update its organic structure, needs culture, the other, the semiotic mediation, as Vygotsky (1934/1996) would say. This implies strengthening the argument for the elaboration of the unit of analysis ACCL, based on Vigotski's statement:

Thought does not arise from itself or from other thoughts, but from the motivational sphere of our consciousness, which encompasses our inclinations and our needs, our interests and impulses, our affections and emotions. Behind every thought there is an affective-volitional tendency. [...] the real and complete understanding of full thought is only possible when we discover the hidden affective-volitional plot behind it (VIGOTSKI, 1934/1996, p. 342).

Thus, to uncover the affective-volitional web that constitutes thought, it is necessary to uncover the social situation of infants' development-which moves us toward examining what is meant by socially situated cognition intertwined with affect, cultures, and languages in use. Roth and Jornet (2017) argue:

(...)

thinking is not a mere subjective activity, as seen in the experience that thoughts come to us (“it thinks”) and that thoughts are subject to an organic development. The whole being is becoming in the course of its life. This is the organizing principle, for example, when Vygotsky writes that the understanding of thinking requires us to view the person in its full life, where the motives and interests of the person come into play, and where intellect and affect are but two manifestations of the unit of person acting in the environment. (ROTH and JORNET, 2017, p. 22. Emphasis in original).

Brown, Collins and Duguid's (1989), studied by Barrenechea (2000), argue that

(...) the cognition of a knowledge has a situated nature because there are parts relevant to its understanding that lie in the context of activity of this knowledge. These parts, however, underlie the culture of knowledge and the value system that this culture employs to use knowledge in different situations (BROWN, COLLINS and DUGUID'S, 1989 apud BARRENECHEA, 2000, p. 42).

Along the same vein, Agar (1994/2002) argues that we have to break the circle around language and connect it with culture (AGAR, 2002), changing our view of the world and of school and non-school practices. For this, language and culture cannot be seen or studied separately. According to Agar, language is in all varieties, in all forms of daily life and constructs a world of meanings. Language fills the empty spaces between us with sound; culture forges human connection through them [empty spaces]. Culture is in language and, language is loaded with culture (AGAR, 2002, p. 28).

For this author, there is no separation between language and culture, grammar, sounds and meanings, so he creates a neologism - languaculture - with the intention of emphasizing the "necessary connection between these two parts, whether of the other or mine, or as always when it becomes personal, something that belongs to both of us" (AGAR, 2002, p. 60). Thus, "langua in languaculture refers to discourse not just words or sentences, and culture in languaculture refers to meanings that include and go beyond what dictionaries and grammar offer" (AGAR, 2002, p. 96. Emphasis in original).

This implies considering culture as a complex system of meanings and senses, as knowledge of myself and the world. Neither language nor culture are closed in their own spaces. In this perspective, culture can help us understand the differences in the use of spoken, written, body language, eye gazes, gestures, etc. Therefore, culture "is something we create, something we invent to fill in the gaps between me and others, it is something we produce in consciousness, it is an intellectual object, which includes thought, intellect, emotions, contradictions and ambiguities" (AGAR, 2002, p. 138).

In this sense, it is not always easy to understand what the other says, how he says it and what are the contextual references on which he relies. For this, it is necessary to seek, as one of the principles of ethnography, the rich points of languaculture. Rich points are those moments when the participants in a conversation take different positions in relation to the same situation. Such differences cause strangeness, or even discomfort, and are supported by the cultural context experienced by each of these participants and, in this sense, give visibility to these diverse contexts and to the diverse experiences of people. Thus, the development understood as drama (VIGOTSKI, 1929/2000) can become visible through the rich points.

Through the "rich points, norms, expectations, roles and relations, rights and duties of belonging and participation of the members become visible to the members [of that culture] and also to ethnographers" (GREEN DIXON, ZAHARLIC, 2001/2005, p. 42). For Agar (2002), when we come across rich points and seek a common understanding, we enter the world of languaculture which, in turn, enables the dismantling of the circle around language, producing languages in use in the social situations of development, that is, in the lived experiences.

Thus, it is through discourse, understood here as languages in use or languacultures, that we can understand the babies' corporal affections. According to Kelly and Licona (2018), "discourse is language in use and includes spoken and written languages, uses of signs and symbols, and non-lexical elements of communication such as body language and eye gaze" (p.11/12). Extending this understanding, we again bring in affection and thought in Espinoza (1991):

The possibility of the soul's reflective action is found, therefore, in the structure of affectivity itself: it is the desire for joy that propels it toward knowledge and action. We think and act not against the affections, but thanks to them. For the first time, after centuries - that is, since Aristotle and Epicurus - philosophy stops demonizing the affections, to take them as the essence of the human (ESPINOSA, 1991, apud CHAUÍ, 1995, p. 71).

Following in this direction, Oliveira (2016) argues with Espinosa (1933/2010) that

(...) affect is action or passion. It concerns the 'affections of the body, by which its potency to act is increased or diminished, stimulated or restrained, and, at the same time, the ideas of these affections' (SPINOSA, 1933/2010, p.98). The bodies, in the Spinozian view, mutually affect each other, so that the human mind knows the human body only from the ideas of the affections that affect the latter (OLIVEIRA, 2016, p.107).

However, subjective experiences are not capable of producing, by themselves, the satisfaction of the person's needs. One must produce personal meanings, intertwined with social meanings, and seek rational, logical, and practical means to satisfy these needs (VIGOTSKI, 1934/1996). In Monteiro's (2015) words,

(...) the affective-cognitive unit is expressed in the form of social meanings, which in their genericity represent the human symbolic universe, becoming meaning to the extent that it unifies the meaning to the purpose of the activity of the individual who thinks, feels and acts in a unique way (MONTEIRO, 2015, p. 150).

In this way, affect and socially situated cognition are constitutive of people in their relations with cultures, with the world, intersubjectively, discursively. That is, the process of becoming conscious of oneself and the world comes from the production of senses and meanings, through the spoken and written languages, the body, the eye gaze, the symbols and cultural signs.

In this sense, we argue that the cultural development of children implies the creation and use of signs for the production of meaning. Children, in this process of development, are able to formulate their own thoughts and understand the speech of others, moving from naming things by means of word-phrases to combining words with the use of social and personal meanings. In this way, "speech is neither a simple articulation of words according to the rules of language, [...] nor a mere expression of the various states of individual consciousness, [...] and, it is not reduced to the code, [...] it is a social event" (PINO, 2005, p. 143). As Bakhtin (1929/1992) argues, the word is the common territory of the speaker and the listener, it is a speech act in a social situation, it is an enunciation, it addresses an interlocutor (p. 113) and "without a social orientation of an appreciative character there is no mental activity; even a newborn baby’s crying is oriented towards his mother" (p. 114).

Thus, one must focus on the contextualization cues of discourses-verbal, nonverbal, and prosodic (GUMPERZ, 2002). It is necessary to focus on what affects babies and young children in order to create something new in their development, considering that the language of the human person is not only constituted in orality, but also in other manifestations, such as gestures, facial expressions, body movements, among others. Thus, even the young infant is able to communicate with the other, with the world and share meanings (OLIVEIRA, 2016).

This leads us to argue for a conception of body as language, which produces social and personal meanings, that is, "The virtue of the body is to be able to affect in countless simultaneous ways other bodies and to be affected by them in countless simultaneous ways [...]" (CHAUÍ, 1995, p.68/69).

From this perspective, babies and young children carry bodies that talk, that feel, that think, that play, not being docile bodies conditioned.

FINAL THOUGHTS

When we take as a premise that the affections are the essence of the human, that they generate our cognition, our ability to know, but to know what is produced as cultures, by semiotic mediation, by the languages in use, in social situations of development, there is no other way than the use of the theoretical and methodological construct [affect/socially situated cognition /cultures/languages in use] - ACCL. This implies understanding that this unit of analysis, "as a semantic system, of the sense-meaning relationship, in human consciousness" (MONTEIRO, 2015, p. 185), may lead us to the understanding of the unique cultural development of each of the twelve infants/toddlers in our research at EMEI Tupi, as well as other babies and young children, considering the dialectical relationship between the local and the global.

It is fundamental to say that these concepts act dialectically, opposing each other and, at the same time, constituting each other. Only based on a dialectical logic that admits internal contradictions between objectification and individual appropriation of cultures can this unit of analysis be thought and put into practice in our research. Only through the dialectical logic that admits the existence of contrary concepts constituting one another can ACCL gain existence as a provisional synthesis, which here gains materiality in the fields of research with infants and young children. Since we believe that human psychological processes, which are essentially historical, social and cultural, cannot be explained based on universal and abstract theories that apply to all human beings, it is necessary to understand "the dialectic that is also historical of human thought processes" (DUARTE, 2001, p. 14).

This dialectical and historical movement allows us to analyze the uniqueness of babies and young children in order to understand them integrally, without being "sacrificed, just like that, to the general laws and statistics of large numbers" (PINO, 2005, p. 185), that is, in a micro genetic perspective of the analysis of the units of the drama of children's cultural development.

REFERENCES

AGAR, Michael. Language Shock: understanding the culture of conversation. New York: Macmillan, 2002(Original, 1994). [ Links ]

BAKER, W. Douglas; GREEN, Judith; SKUKAUSKAITE, Audra. Video-enabled ethnographic research: a microethnographic perspective. In: WALFORD, G (ed.) How to do educational ethnography, 2008. p. 77-114. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail (Volochinov). Marxismo e Filosofia da Linguagem. 6 ed. Tradução: Michel Lahud e Yara Frateschi Vieira. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1992. (Original, 1929-1930). [ Links ]

BARRENECHEA, Cristina A. Cognição situada e a cultura da aprendizagem: algumas considerações. Educar, Curitiba, n.16, p. 139-153, 2000. [ Links ]

CHAUÍ, Marilena. Espinosa: uma filosofia da liberdade. São Paulo, Editora Moderna, 1995. [ Links ]

CASTANHEIRA, Maria Lúcia. Aprendizagem Contextualizada: discurso e inclusão na sala de aula. Belo Horizonte: Ceale; Autêntica, 2004. [ Links ]

CORSARO, William A. Friendship and peer culture in the early years. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex, 1985. [ Links ]

CORSARO, William A. Sociologia da Infância. 2 ed.Tradução: Lia Gabriele Regius Reis. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. [ Links ]

DANTAS, Heloysa. A afetividade e a construção do sujeito na psicogenética de Wallon. In: La Taille, Yves de (org.). Piaget, Vygotsky, Wallon: teorias psicogenéticas em discussão. São Paulo: Summus, 1992. [ Links ]

DUARTE, Newton. Vigotski e o “aprender a aprender” - crítica às apropriações neoliberais e pós-modernas da teoria Vigotskiana, São Paulo: Editora autores Associados, 2001. [ Links ]

ESPINOSA, Benedictus de. Pensamentos Metafísicos - Tratados de Correção do Intelecto; Ética. Seleção de textos Marilena Chauí. São Paulo: Nova Cultural, 1991. [Os Pensadores]. [ Links ]

FONTES, Flávio Fernandes et al. Psicologia histórico-cultural, Perezhivanie e além: uma entrevista com Nikolai Veresov. Educ. Soc., Campinas, v. 40, e 0184797, 2019. [ Links ]

GEERTZ, Clifford. A interpretação das culturas. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 1989. [ Links ]

GÓES, Maria Cecília Rafael de. A abordagem microgenética na matriz histórico-cultural: uma perspectiva para o estudo da constituição da subjetividade. Cadernos CEDES, Campinas, v. 20, n. 50, p. 9-25, abr. 2000. [ Links ]

GOMES, Maria de Fátima Cardoso. Memorial - Trajetórias de uma Pesquisadora e suas Apropriações da Psicologia Histórico-Cultural e da Etnografia em Educação. Curitiba: Brazil Publishing, 2020. [ Links ]

GREEN, Judith Lee; DIXON, Carol; ZAHARLICK, Ann. Ethnography as a Logic of Inquiry.In: FLOOD, J; LAPP, D; JENSEN, J; SQUIRES, J (Eds.) Handbook for Research on Teaching the English Language Arts. 2 ed. New Jersey: LEA, 2001. p. 201-224. [ Links ]

GUMPERZ, John. Convenções de contextualização. In: RIBEIRO, Branca. Telles; GARCEZ, Pedro (org.) Sociolinguística Interacional. São Paulo: Loyola. 2002. p. 55-76. [ Links ]

KELLY, Gregory J.; LICONA, Peter. Epistemic practices and Science Education. In: MATHEWS, Michael R. (Ed.), History, philosophy and science teaching: New research perspectives. Springer International Publishing, AG, 2018. p. 139-165. [ Links ]

MAHN, Holbrook. Vygotsky’s “Speaking/Thinking System of Meaning”: An Essential but Overlooked Concept - University of New Mexico. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.academia.edu/547620/Vygotsky_s_Speaking_Thinking_System_of_Meaning_An_Essential_but_Overlooked_Concept >. Acesso em: 01 set. 2019. [ Links ]

MONTEIRO, Patrícia Verlingue Ramires. A unidade afetivo-cognitiva: aspectos conceituais e metodológicos a partir da Psicologia Histórico-cultural, p. 193. Dissertação (Mestrado em Psicologia) Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2015. [ Links ]

NEVES, Vanessa Ferraz Almeida; GOMES, Maria de Fátima Cardoso; DOMINICI, Isabela Costa. Literacy in the Making: Integrating Infant’s Emotions, Embodiment, and Cognition in a Brazilian Early Childhood Education Center. In: KATZ, Laurie; WILSON, Melissa. (Org.). Understanding the worlds of young children. 1ed. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, 2021, v. 1, p. 13-36. [ Links ]

NEVES, Vanessa Ferraz Almeida; MÜELLER, Fernanda. Ética no encontro com bebês e seus/suas cuidadores/as. Comissão de Ética em Pesquisa na ANPED. Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Educação (org.). Ética e pesquisa em Educação: subsídios. 1ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: ANPEd, v. 2, 2021. p. 94-101. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA Luciana da Silva de. Um lócus de constituição do humano: vivências e afecções de bebês e educadoras na creche. 2016. p. 278. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2016. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Marta Kohl. Cultura & Psicologia: questões sobre o desenvolvimento do adulto. São Paulo: Aderaldo & Rotschild, 2009. [ Links ]

PINO, Angel. As marcas do humano: às origens da constituição cultural da criança na perspectiva de Lev S. Vigotski. São Paulo: Cortez, 2005. [ Links ]

ROTH, Wolff-Michael; JORNET, Alfredo. Understanding Educational Psychology. A Late Vygotskian, Spinozist Approach. Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 1ª ed., 2017. [ Links ]

SILVA, Elenice Brito Teixeira; NEVES, Vanessa Ferraz Almeida. Os estudos sobre a educação de bebês no Brasil. Educação Unisinos, São Leopoldo, v. 24, n. 1, p. 1-19, 2020. [ Links ]

SIRGADO, Angel Pino. O social e o cultural na obra de Vigotski. Educ. Soc., Campinas, v. 21, n. 71, p. 45-78, jul. 2000. [ Links ]

SPRADLEY, James P. Participant observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1980. [ Links ]

STREET, Brian. What's "new" in New Literacy Studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Current Issues in Comparative Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, Vol. 5(2), p.77-91, 2003. [ Links ]

THONG, Tran. Prefácio. In: WALLON, Henri. A criança turbulenta: estudos sobre os retardamentos e as anomalias do desenvolvimento motor e mental. Trad. Gentil Avelino Titton. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2007. p. 09-39. [ Links ]

TOASSA, Gisele. Conceito de consciência em Vigotski. Psicologia USP, [S. l.], v. 17, n. 2, p. 59-83, 2006. [ Links ]

VERESOV, Nicholai; FLEER, Marilyn. Perezhivanie as a theorical concept for researching Young children’s development. Mind, Culture, and Activity, v. 23, n. 4, 325-335, 2016. Disponível em: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2016.1186198>. Acesso:14/07/2020. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev Semiónovitch. Manuscrito de 1929. Educ. Soc., Campinas, v. 21, n. 71, p. 21-44, jul, 2000. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev Semiónovitch. 7 Aulas de L. S. Vigotski: sobre os fundamentos da Pedologia. [Trad. Zoia Prestes e Elizabeth Tunes], Rio de Janeiro: E-papers, 2018(Original, 1932). [ Links ]

VYGOTSKI, Lev Semiónovitch. Análisis de las Funciones Psíquicas Superiores. In: Obras Escogidas: Problemas del Desarrollo de la Psique, Tomo III, Madrid: Aprendizaje: Visor, 1995a, p.97-120. (Original, 1931). [ Links ]

VYGOTSKI, Lev Semiónovitch. Método de Investigación. In: Obras Escogidas: Problemas del Desarrollo de la Psique, Tomo III, Madrid: Aprendizaje: Visor, 1995b, p.47-96. (Original, 1931). [ Links ]

VYGOTSKI, Lev Semiónovitch. Pensamiento y Palabra. In: Obras Escogidas: Problemas de Psicología en General, Tomo II, Madrid: Aprendizaje: Visor, 1996, p.287-348. (Original, 1934). [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev Semiónovitch; LURIA, Alexander R. Estudos sobre a história do comportamento: símios, homem primitivo e criança. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1996. [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. As origens do caráter na criança. São Paulo: Difel, 1972. [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. Le rôle de l’autre dans la conscience du moi. Enfance, v. 12, n.3-4, 1959. p.277-286. [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. Do ato ao pensamento: ensaio de psicologia comparada. Trad. Gentil Avelino Titton. Petrópolis: Vozes , 2008. [ Links ]

WERTSCH, James V. Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985. [ Links ]

ZANELLA, Andréa Vieira et al. Questões de método em textos de Vygotski: contribuições à pesquisa em psicologia. Psicol. Soc., Porto Alegre, v. 19, n. 2, p. 25-33, Aug. 2007. [ Links ]

1Usually the Russian terms ‘perezhivanie’ (singular) or ‘perizhivanya’ (plural) have been translated into English as ‘experience’ or ‘lived experience’, which does not capture the complexity of this Vygotskyan notion. Thus, we clarify that as we use the term ‘experience’, we are referring to the notion of ‘perizhivanie’ throughout this paper.

* The translation of this article into English was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG - through the program of supporting the publication of institutional scientific journals.

Received: December 04, 2020; Accepted: June 01, 2021

texto em

texto em