Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 16-Mar-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469824481

SCHOOL SPACES AND ARCHITECTURES

LEARNING TO INHABIT THE SCHOOL ARCHITECTURE OF THE NEW URBAN ORDER (FEDERAL DISTRICT, MEXICO, 1932)

2Dirección de Difusión de Ciencia y Tecnología del Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Mexico City, Mexico. <cortegai@ipn.mx>

In 1932, the team of technicians led by the functionalist architect Juan O'Gorman developed a school architecture project for the popular neighborhoods of the Federal District (Mexico). One of these schools, the Emiliano Zapata elementary school (now recognized as a national artistic monument), was built in a neighborhood founded in the north of Mexico City as part of an urban expansion strategy promoted by businessmen and the Mexican government. Its builders believed that the school building was the means to transform the popular classes of Mexican society and promote a modern urban order. Functionalist school architecture generated heated discussions between engineers and architects about the impact of this type of building on the urban landscape and on the taste of its inhabitants. However, its promoters assured that eventually the popular classes would learn to inhabit the new school buildings and overcome the illiteracy and insalubrity that affected both their bodies and their minds.

Key words: School architecture; Learning; Modernity; Urban order; Juan O'Gorman

En 1932, el equipo de técnicos dirigido por el arquitecto funcionalista Juan O’Gorman desarrolló un proyecto de arquitectura escolar para las colonias populares del Distrito Federal (México). Una de esas escuelas, la escuela primaria Emiliano Zapata (actualmente reconocida como monumento artístico nacional), fue construida en una colonia fundada en el norte de la ciudad de México como parte de una estrategia de expansión urbana impulsada por empresarios y por el gobierno mexicano. Sus constructores pensaban que el edificio escolar era el medio para transformar a las clases populares de la sociedad mexicana e impulsar un orden urbano moderno. La arquitectura escolar funcionalista generó discusiones acaloradas entre ingenieros y arquitectos sobre el impacto de este tipo de edificios en el paisaje urbano y en el gusto de sus habitantes. Sin embargo, sus promotores aseguraban que eventualmente las clases populares aprenderían a habitar los nuevos edificios escolares y superarían el analfabetismo y la insalubridad que afectaban tanto a sus cuerpos como a sus mentes.

Palabras clave: Arquitectura escolar; Aprendizaje; Modernidad; Orden urbano; Juan O’Gorman

Em 1932, a equipe de técnicos liderada pelo arquiteto funcionalista Juan O´Gorman desenvolveu um projeto de arquitetura escolar para os bairros populares do Distrito Federal (México). Uma dessas escolas, a Escola Primária Emiliano Zapata (atualmente reconhecida como monumento artístico nacional), foi construída em um bairro fundado no norte da Cidade do México como parte de uma estratégia de expansão urbana promovida por empresários e pelo governo mexicano. Seus construtores pensaram que o prédio da escola era o meio de transformar as classes populares da sociedade mexicana e promover uma ordem urbana moderna. A arquitetura funcionalista da escola gerasse discussões acaloradas entre engenheiros e arquitetos sobre o impacto desse tipo de construção na paisagem urbana e no gosto de seus habitantes. No entanto, seus promotores garantiram que, eventualmente, as classes populares aprenderiam a habitar os novos edifícios da escola e superariam o analfabetismo e a insalubridade que afetavam seus corpos e mentes.

Palavras-chave: Arquitetura escolar; Aprendendo; Modernidade; Ordem urbana; Juan O'Gorman

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this article is to stimulate historical reflection on the learning of the human body to inhabit a type of school architecture. I refer to the functionalist school architecture promoted by architect Juan O'Gorman as part of the development of a modern urban order in the first half of the twentieth century. For this purpose, I initially undertake a retrospective walk to the Industrial neighborhood, where the Emiliano Zapata Elementary School was built in 1932, in order to locate it in a strategy of colonization and political neutralization aimed at giving a new regime to the Federal District (Mexico). Subsequently, I refer to the efforts of practical intellectuals (mainly engineers and architects) to design a new urban order through a series of technical acts, such as the foundation of a modern colony and the construction of a functionalist elementary school that would eradicate from the body of its inhabitants the affectations caused by the old order. Then I focus on the vision of those same intellectuals on the learning or habituation of the popular classes to inhabit a school architecture that, they assured, would transform their bodies affected by the old regime into physically and intellectually healthy bodies. Along the way, I turn to the ideas of André Le Breton, Zygmunt Bauman and Michel Serres to understand the configuration of the human body in the projects developed by the promoters of modernization. In this article I will stop referring to the Porfiriato (1880-1910), the period of the revolution (1910-1920) and the post-revolutionary regime (from 1920 onwards) as temporal parameters. I will speak of an old order and a new order because the construction of modernity has been a long-term process that traverses these moments, linking them. Finally, the article also aims to contribute to the discernment of the relations of mutual molding of the subjects -of their bodies- with the materiality and technology of the school, and of the school with the city, based on the study of modern school architecture within the socio-cultural history of education3.

WALKING TO THE OTHER EXTREME

The identification of eleven schools, out of the 21 that the technical team headed by Juan O'Gorman designed in 1932 for several towns and popular neighborhoods in Mexico City, led me on a journey in three planes: a documentary one (in the Mexico City's Historical Archive Map Library), a virtual one (through Google Earth) and another one through the streets of Mexico City. The journey on these maps was a bodily experience. However, I will only refer to the experience of walking through the streets of Mexico City in search of one of the functionalist school buildings, that of the Emiliano Zapata Elementary School, declared a national artistic monument in 2018 [Presidency of the Republic, 2018: 69-70], or what was left of it.

Le Breton described the act of walking in these words:

'Like all human enterprises, even that of thinking, walking is a bodily activity, but it involves more than any other breathing, tiredness, will, courage in the face of the harshness of the route or the uncertainty of arrival, moments of hunger or thirst when no fountain is to be found within reach of the lips, no shelter, no farm to relieve the traveler of the fatigue of the journey.' [Le Breton, 2011: 31]

His words reminded me that the historian, before having consecrated himself or resisting the consecration that anchors him to the pedestal, is matter that moves through the world, even if his corporeality -excluded in the rationalist dictum- is not named. Each path he begins is a rehearsal: he follows the tracks, hesitates, asks for advice, moves forward, clings, deviates, goes backwards, gets lost, abandons the march, arrives....

So, one Friday in August 2019 I took the route that would take me to the Emiliano Zapata elementary school, located in the Industrial neighborhood in the north of Mexico City. As I left the Potrero station of the Collective Transportation System-Metro I sharpened my senses to perceive the signs that would lead me more than eighty years ago.

Each step introduced me to a neighborhood founded in 1926 on one side of the Guadalupe Causeway, in the municipality of Guadalupe Hidalgo (now the municipality of Gustavo A. Madero). At that time, Mexico City was expanding towards the four cardinal points of the Federal District. The subdivision of the old haciendas surrounding the city and the political neutralization of the municipal governments were two concatenated factors of urban planning in the first half of the 20th century, although, as Ariel Rodríguez Kuri [1996] points out, their neutralization began in the eighties of the previous century with the gradual loss of powers of the City Council of Mexico.

The division of the vacant land of the haciendas for colonization and urbanization was a lucrative business in which businessmen and public officials participated. The land of the Ahuehuetes hacienda, where the Industrial Colony was founded, was acquired by a tripartite partnership formed by the engineer Alberto Pani, who served as Secretary of Finance in the government of Plutarco Elías Calles and was dedicated to the reorganization of the national financial system, the banker Agustín Legorreta, director of Banco Nacional de México S.A., and the engineer Roberto Rodríguez. Between the three of them, they paid 120,000 pesos for 120 hectares of the hacienda [Pani, 2003: 303].

According to functionalist urbanism, the geometric and standardized lot system was a way to prolong cities in an orderly fashion. Le Corbusier, whose techno-political approaches were promoted by young Mexican architects since the 1920s, proposed replacing the old, irregular and confused layout of cities with successive groups of houses winding along diagonal avenues in keeping with the spirit of mass production of the industrial era [Le Corbusier, 1925: 47]. According to Le Corbusier's functionalist doctrine [1925], the imposition of this urban order would bring welfare for the inhabitants of any metropolis.

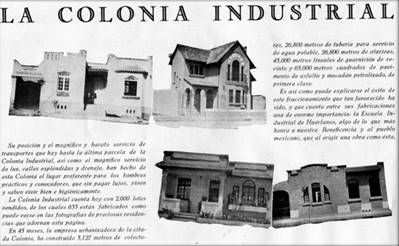

In accordance with these ideas, the urbanizing company promoted the Industrial Colony as a place to li Corbusier e well and hygienically, without luxuries, since it had streets paved with asphalt and oiled macadam, electricity, drainage, drinking water and public transportation, especially an electric tramway station [Images 1 and 2]. The foundation of this type of colonies coincided with the Federal District government's attribution to favor the construction of hygienic houses for the habitation of the humble classes, although under the modality of renting [Federal Executive Branch, 1928-1929, article 24, IX], and was an incentive for the increase of the population and the widening of the city thanks to its sanitary infrastructure and the urban services it had [Department of National Statistics (DEN), 1935: 20].

Continuing with Pani's autobiographical testimony, more than three thousand six hundred houses, four parks, a market, a school and a movie theater were built in the Industrial Colony between 1926 and 1945 [Pani, 2003: 304]. But a photograph from 1955, kept in the photo library of the National Institute of Anthropology and History, shows the existence of a precarious dwelling, built with wooden sheets, in a street of the new colony [Image 3].

The existence of a shack represented the permanence of chaos, the absence of form in the midst of the new urban order. In 1933 two young functionalist architects, Juan Legarreta and Álvaro Aburto, observed the existence of a few modern cities, with large avenues, buildings and monuments, in a country whose people lived mostly in round rooms and jacales with grass roofs and reed walls [SAM, 1933]. For both architects, these rooms reflected the dematerialized life of a people who could not overcome nature -dangerous because it was unhealthy- because they suffered from the lack of technical intervention in their way of life.

At the time of its foundation, the Industrial colony belonged to the municipality of Guadalupe Hidalgo, but a series of reforms undertaken by the federal government replaced the municipal governments (whose authorities were elected by the inhabitants of the locality) with delegations of the Federal District Department (DDF).

The Organic Law of 1928-1929 stipulated that the government of the delegations corresponded to the Head of the DDF, who would exercise it through delegates appointed by him in agreement with the President of the Republic. Each delegate was assisted by subdelegates. who represented him in the towns that were not the head of the delegation and by an advisory council made up of the "main interests of the locality" [Federal Executive Branch, 1928-1929, chapter X]. The delegate had the power to choose among the associations of merchants, industrialists, real estate owners, tenants, peasants, professionals, public and private employees, workers and mothers, those who represented those interests [Federal Executive Branch, 1928-1929, chapter X].

The reform of the political regime of Mexico City was aimed at governing a city that was constantly expanding due to the growth of the surrounding towns and the formation of new colonies as a result of the intervention of multiple interests [DEN, 1935]. Vicente Lombardo Toledano, who did not agree with the de-municipalization of the Federal District, recognized that governability was a technical and political issue common to the great cities of the world, since their growth had inevitably generated a crisis in their system of government and administrative organization [Lombardo, 1928: 17].

Seen in this light, I dare to suggest that the reform was intended to prevent, through a new political organization of the capital's society, the occurrence of anything; for example, another revolution, which was seen by intellectuals of different tendencies as a synonym of disorder or catastrophe caused by the irruption of dissatisfied and irrational popular classes. For Juan O'Gorman, the popular classes were a people "lacking in elementary reasoning" who lacked comfortable and hygienic living quarters [Society of Mexican Architects (SAM), 1934: 15]. For another architect, Manuel Amábilis, it was a rebellious people with disoriented aspirations [SAM, 1934: 9].

This reform politically neutralized Mexico City for almost nine decades, until its inhabitants were able to elect their mayors again in 2018. Thus, the expansion of the city and its political control were concatenated in a project that sought to give a new order to a dynamic city that in 1930 was recognized as one of the main cultural, commercial and business centers of America and the world. In order to support it as a modern, orderly, hygienic and harmonious city, the federal government decreed the Planning and Zoning Law of the Federal District in 1933, according to which Mexico City would be divided into classified zones according to the functions and uses for which they were intended [Federal Executive Branch, 1933: 5-7], including residential, commercial and industrial zones.

As part of the reorganization imposed on Mexico City, the Industrial Colony passed from the jurisdiction of the Guadalupe Hidalgo Delegation (which disappeared in 1931) to the Azcapotzalco Delegation [Federal Executive Branch, 1931, article 7].

In the 1930 census, the Azcapotzalco Delegation was the second most populated in Mexico City, with 40 thousand inhabitants and one of the highest urban population indexes (60.5%), far below the one million inhabitants of Mexico City (whose population was considered totally urban). Most of the inhabitants of the delegation, almost 50%, were concentrated in the village of Azcapotzalco, and the rest lived in ranches, haciendas and towns with no more than 300 inhabitants. We can assume that most of the heads of households (men) did not own the place where they lived. In Mexico City, the norm was to live in a rented house [DEN, 1935].

Azcapotzalco shared with the San Angel Delegation the third place in the illiteracy rate in Mexico City because 32% of its inhabitants over the age of 10 could neither read nor write. In contrast, Mexico City and Coyoacán had the lowest illiteracy rate in Mexico City, 20% and 27% respectively. In other delegations such as Cuajimalpa, Iztapalapa and Milpa Alta, whose population was mostly rural, the illiteracy rate was 47%, exceeding 70% among women over 30 years of age. In the case of Azcapotzalco, illiteracy among women over 10 years of age exceeded that of men by more than six percentage points [DEN, 1935].

The same census gives us an image of the Industrial Colony different from the one promoted by the developers of the land on which it was founded four years earlier. The item relating to the population distributed by localities does not include the name of the Industrial colony. Instead, it provides the number of inhabitants (278) of the first and second sections of the Hacienda de los Ahuehuetes. The second section, inhabited by 81 people, corresponded to the land occupied by the new colony [DEN, 1935].

Thus, the Industrial Colony, whose streets were named after some of Mexico's main industries, was just an enclave, perhaps still a project of the city's expansion over a territory made up of ranches, haciendas and towns. On one side of one of its streets, called Monterrey Smelter, the Mexico City government built in 1932 a functionalist building for the Emiliano Zapata elementary school (an icon of revolutionary agrarianism), with a capacity to house 1,000 children. The Ministry of Public Education argued that the construction of schools like this one would solve the deficit of buildings caused by the rapid increase of the population of the Federal District [Secretary of Public Education (SEP), 1932: 55].

However, the disparity between the capacity of the school (one thousand children), in a delegation whose illiteracy rate exceeded 30%, and the number of inhabitants of the Industrial colony (less than one hundred) stands out. But serving the school population of the area (not only of the colony at birth) and stimulating the colonization of the land of the Hacienda de los Ahuehuetes, could be two articulated objectives. A modern, ample and hygienic school was part of the urban infrastructure and public services that developers and governments mentioned to stimulate the settlement of the recently occupied territories, won from the rural world.

The walk ended in front of the Emiliano Zapata elementary school; whose building was later divided to house another elementary school (the Jesus Romero Flores Elementary School). There I was able to observe what remains of the 1932 building: the façade, the blind wall, the masonry, the classrooms and the floor plan [Images 4 and 5]. Inside the Emiliano Zapata school, the murals of Pablo O'Higgins on labor, the workers' struggle and social problems are in serious deterioration.

Source: Photograph by the author.

Image 5 Side façade of Emiliano Zapata Elementary School, 2019. [Currently corresponds to the Jesús Romero Flores school].

From these clues I try to imagine the building, following the functionalist doctrine that guided its design, as a machine, as a tool developed to satisfy the need for economical, comfortable and hygienic rooms of the future inhabitants of the Colonia Industrial S.A. project. As I do so, I turn to Bauman's [2015: 38-39] ideas about designs in the history of the modern era as portraits of a future reality different from the one known to the designers, who did not count, because it was precisely about the future, what the world that would emerge at the other end of their construction efforts, the end at which I find myself standing, would be like.

OVERCOMING THE BURDENS OF FILTH AND IGNORANCE

In 1932 the Industrial Colony and the Emiliano Zapata elementary school embodied the project of a future order built on the basis of technical progress. Technique, defined then by the Madrid philosopher José Ortega y Gasset [2004] as the effort dedicated to design that which does not exist in man's nature (assigning it a masculine character), was seen as the means to overcome a reality that disgusted and frightened intellectuals who served as state intellectuals and public officials, and who wished to set the popular classes on the path of a modernity of which they were promoters [Fiorucci and Rodríguez, 2018].

Such a process demanded the performance of a type of practical intellectual who would assume the task of building the new social order through the transformation of nature, applying the laws of science, as stated by the engineer Agustín Aragón at the beginning of the twentieth century [Aragón, 1900: 73]. That practical intellectual was the engineer, whose technical training and virile behavior endorsed him as the builder of modernity, unlike the sentimental architects or artists, who -according to Le Corbusier [1925] and Juan O'Gorman [SAM, 1933]- represented the old regime and were incapable of undertaking the new task.

In the urban reform projects, modernity was proposed as the overcoming of an outdated regime whose remnants could be found in every corner of the Federal District, obstructing the construction of the new urban order. For this reason, the work of engineers consisted of correcting the effects of the old regime (disorder and chaos) through their works, and eradicating its subsistence in the new urban order in order to avoid a new catastrophe or a revolution led by the dispossessed and illiterate.

In this sense modernity, as Bauman suggests, is a process of construction of a new order permanently confronted with the past that one wishes to overcome. But the new order, insofar as it is a future order, is a yearning that its promoters feed compulsively and addictively because the suppression of the old regime seems an endless task [Bauman, 2015: 45-46].

The engineer Alberto Pani, who since the first decade of the twentieth century was committed to lend his technical services to form a new order, denounced the chiaroscuro of the old regime. As an agent of the new regime, he was of the opinion that the material and cultural progress, sometimes apparent, of the Federal District during the old order, contrasted with the abundant existence of specimens corresponding to the most primitive historical stages of civilization [Pani, 2003: 201]. In the same sense, Félix Palavicini, another engineer added to the cause of the new regime, described Mexico City in 1916 as a capital in which sumptuous palaces of marble and granite rose, without art, and through whose asphalted streets walked the subjects created by the old regime: "the ragged and lousy Indians" [Secretariat of Culture, 2016:702].

Pani judged that the actions of the old regime in terms of popular education and public health, areas he considered proper to civilized societies, had been superficial and inefficient and wondered what beneficial effects a school poorly equipped with technical and material elements could have on the habits and character of the children of the lower town in the face of the "powerful atavistic influence and the even more powerful influence of the unhealthy and immoral environment they aspire to, in the tenement houses... in all the moments of their lives and from the moment they are born" [Pani, 2003: 111-112].

In short, the illiteracy and unhealthiness of the popular classes were the fate of the old regime and its inheritance to the new order. A legacy that a young architect, Juan O'Gorman, wished to eradicate through a technical, engineering architecture that could count on the support of the federal government.

In 1933, O'Gorman observed an absolute disorder in the architecture of Mexico City as a result of an irrational way of proceeding based on the taste and feelings of both the owners (who formed a minority) and the architects (who were at the service of that minority). He charged that in one street it was possible to find a classical, a Louis XI, a pseudo-colonial and a modernist building, and he compared the houses of the new middle-class neighborhoods, such as the Racetrack, to an anarchist picture without order or science [SAM, 1934: 11-13].

For O'Gorman, on the other side of that city were the Mexican people; a majority whom he described as ignorant, lacking education and elementary reasoning, and whose life was, consequently, poor, miserable and tragic [SAM, 1934]. These people lived in pigsties, in poorly built, shabby and imperfect houses.

In view of this situation, it was evident to O'Gorman that the Federal District required the intervention of a technical architecture that would satisfy -through measurable and standardized procedures- the basic needs of the majority of its inhabitants. An architecture that would free the people from their main enemies, nature and fanaticism, by providing them with better living quarters. A modern architecture that would enable them to overcome what in their view were "burdens of filth and ignorance" [SAM, 1934: 15].

For the modernizing engineers and architects, the old regime was still alive in the city, in its historical and monumental architecture and in the primitive customs, in the unregulated behavior, in the unhealthy habits and in the dematerialized life of the people (euphemism with which they referred to the poor). For these practical intellectuals, the founding of the Industrial Colony and the construction of the Emiliano Zapata elementary school were technical acts that would correct the disastrous effects of the old regime and underpin a new urban order. In his opinion, the materialization of the colony and the school, and of other colonies and other similar schools, would positively transform the inhabitants of the Federal District. By intervening in children through school architecture, they had in mind the design of a future subject. For the Secretariat of Public Education, it was a plan to socialize urban education and to intensify the cultural effort in the countryside [SEP, 1932: 56].

In general, the construction of schools was part of the planning projects of the Federal District. In 1935, the recently formed DF Regulatory Plan Committee concluded that one of the problems to be solved was the adequate distribution of schools taking into account the density of the school population, the accessibility of the area and the availability of open spaces, gardens and playgrounds [Regulatory Plan Committee, 1935: 64]. After all, as stated by architect Carlos Contreras, promoter of these planning initiatives, the idea was to make Mexico City "a model of cleanliness and order" [Contreras, 1928: 4]. However, despite all these desires, the practical intellectuals could not be certain of what the subject that would emerge at the other end of their construction efforts would be like.

CREATING TASTE, ACCUSTOMING THE BODY

In the 1920s Le Corbusier published Vers une architecture, a techno-political program that guided the modernizing projects of functionalist architects such as Juan O'Gorman. For them, who also included Juan Legarreta and Álvaro Aburto, technical architecture, also called functional architecture, was the means by which a new social order could be formed. However, as Le Corbusier [1925] recognized, the state of mind to build and inhabit houses in series had yet to be created in architects and, even more so, in a population persuaded by old-style architecture. In other words, functionalist architects had the task of forming the taste and disposition to inhabit those houses built in the manner of industrial production. In Europe, intellectuals such as Ortega and Gasset [1992] and Walter Benjamin [2003] believed, from different philosophical positions, that this was a new era for art, that of industrial production, which would introduce changes in the perception or sensibility of the subjects, both artists and the public.

The architecture of the new rooms had a formative function: to train its inhabitants, to educate their senses, to condition their bodies, to accustom them to the new material reality and to the other bodies with whom they would live face to face in a territory bounded by partition walls and reinforced concrete. The modernizing architects wanted to achieve with their new designs what the previous designs could not: to overcome the burdens and atavisms that afflicted the popular classes. Their goal was to transform the poor, following the bio-political route of hygienism [Suárez, 2005], into physically and morally healthy beings through technical architecture.

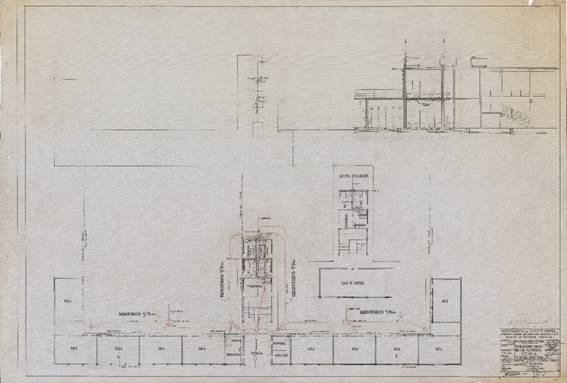

O'Gorman stated before his colleagues of the Society of Mexican Architects that his purpose was to give physical and moral hygiene to the people through the economic and standardized construction of comfortable school buildings, with large windows and sufficient shower baths [SAM, 1934]. According to O'Gorman's project, the Emiliano Zapata elementary school, built with reinforced concrete and brick on the grounds of the Industrial neighborhood, would house one thousand children in twenty classrooms located on two floors. The building would have a library, dining room, infirmary, meeting room, administration, janitor's room, WC and shower bathrooms for women and men [Image 6]. The electrical and sanitary installations, drainage, drinking water supply and the ventilation of the classrooms by means of masonry arranged on the side façade of the school (in the blind wall), would guarantee the proper functioning of the building and the health of its inhabitants as dictated by the functionalist canon [SEP, 1932].

Source: Mexico City's Historical Archive Map Library.

Image 6 Plan of the Emiliano Zapata Elementary School, 1932.

Other architects and engineers, considered representatives of the "old spiritual structure," had a negative perception of technical architecture and of the school buildings designed by O'Gorman.

Architect Manuel Amábilis rejected any attempt to subject architecture to a standardized production process, "to the narrow rigidity of a pre-established geometric layout" whose result could only be the construction of buildings without beauty [SAM, 1934: 8]. The engineer Raúl Castro Padilla agreed with him, who was of the opinion that O'Gorman's school buildings were examples of a peristaltic architecture that only expressed pauperism [SAM, 1934: 29]. For Castro Padilla, O'Gorman's work lacked imagination and effort because he had limited himself to copying architectural elements standardized by merchants and industrialists and to thinking in cubes or parallelepipeds with holes and prison bars [SAM, 1934: 29-30].

Similarly, architect Silvano Palafox believed that the worker, the peasant and the proletarian would feel uncomfortable, unhappy and dissatisfied with this type of rooms [SAM, 1934: 40], which -according to Federico Mariscal- were a sign of the retrogradation of architecture to the gregarious instinct of the horde or clan [SAM, 1934: 27]. Palafox equated the inhabitant of the new constructions -which he and his colleagues described as the result of irrational aspirations stimulated by the destruction of the old regime- with a savage who upon hearing Beethoven's Ninth Symphony "would come out shrieking, because he would feel deeply hurt by such music" [SAM, 1934: 40] [SAM, 1934: 40].

Other architects recognized the formative role of O'Gorman's architecture, despite not fully sharing his functionalist orientation. Manuel Ortiz Monasterio asserted that in general the social role of architecture was to educate, moralize and improve society [SAM, 1934: 20]. In particular, he believed that O'Gorman's school buildings, together with the plastic work of the muralist painters, played an important role in the preparation of "a strong, healthy, simple and joyful generation, capable of being moved by truth, goodness and beauty, and of forging noble ideals that would elevate it above the clumsy and hard conceptions of matter" [SEP, 1932: 66].

O'Gorman was not unaware of the formative function of his architecture, and, in a reply to the critics of functionalism, he affirmed, making an analogy between the new designs and language, that people would get used to hearing beautiful things that at first seem ugly. For the Secretary of Public Education, the acceptance of this architecture was a matter of time [SEP, 1932: 64].

OTHER POSSIBILITIES

Getting used to the new school architecture implied the incorporation of its materiality. That the displacement and the disposition of the body, of the senses, in the comfortable and hygienic rooms that would replace the jacales, huts and pigsties, would become unconscious acts because unconsciousness, as proposed by Michel Serres [2011], is to forget the materiality of the body and the relationship of mutual molding that it establishes with things and objects. In the body, learning consists of:

Complicated chains of postures are so easily incorporated into his muscles, bones and joints that he buries the memory of this complexity in a simple oblivion. And then, as if without knowing it, he reproduces these series of positions faster than he assimilated them [Serres, 2011: 82].

But this silent learning has its balance, its counterweight, in the inventive production, in the variation of bodily gestures. Serres assumes that the body also learns to be able to do almost everything [Serres, 2011: 53]. In such a way that the body of the popular classes, in which the practical intellectuals wished to intervene through technical architecture to eradicate ballast and atavisms in order to build a new urban order, could become accustomed to O'Gorman's functionalist schools and learn to evade the walls built in series by modernity.

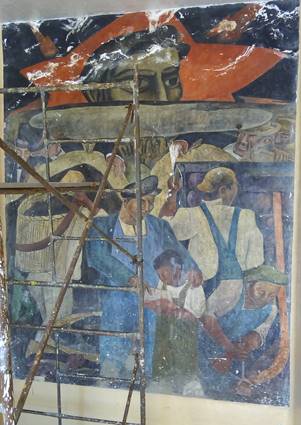

In 1933 the American-born painter Pablo O'Higgins depicted these bodies on the walls of the Emiliano Zapata elementary school. Following the political-pedagogical program of Mexican muralism [Lear, 2019], O'Higgins, who was a disciple of Diego Rivera, embodied his desire to lead working children along a path that would free them from exploitation and ignorance thanks to the guidance of a dark, healthy, virile, workers' leader, with a grim gesture and dressed in overalls, who offers them a red book and indicates the path of the proletarian demonstration they should follow.

But in "The reality of work and its struggles" and in "Life and social problems", the gesture of the children varies [Images 7 and 8]. While two children work in the production of glass, one completely naked and the other with his torso uncovered, another, outside a mine, fixes his attention on the part of the red book that his mentor - the workers' leader - indicates to him. Still others, a boy and a girl (the only woman in the two scenes), suggest other possibilities. Although the worker leader extends a red book to them with his right hand and with his left-hand points to a proletarian demonstration, both children look away. They do not pay attention to the worker, the book or the demonstration. They look away from the painting, in the opposite direction to their mentor's indications, because they are attracted by something else.

Source: Photograph by the author.

Image 8 Pablo O'Higgins, "The reality of labor and its struggles", 1933.

I observe them from the world that emerged at the other end of the efforts dedicated to build, eight decades ago, a modern city, an industrial colony, a functionalist school and a body free of ballast and atavisms, physically and intellectually healthy. A world in which, despite the compulsive efforts of the modernizers of yesterday, continued by the modernizers of today, disorder continues to manifest itself. To eradicate it, as in a never-ending story, we continue to design technical, architectural and pedagogical interventions.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

As I initially proposed, the article was intended to stimulate historical reflection on the learning of the human body to inhabit a type of school architecture and to contribute to the discernment of the relationships of mutual molding of subjects with technology and the materiality of the school (particularly of its architecture and of this with the city). The founding of the Colonia Industrial, in 1926, and the construction of the Emiliano Zapata Elementary School, in 1932, were two events that allowed me to expose how the school could have influenced urban expansion by stimulating the colonization of the uncultivated land of the old haciendas that surrounded Mexico City, and how the promoters of the new urban order thought that the school would contribute to the transformation of its inhabitants by accustoming them to inhabit the new architectural reality that the school embodied. However, I recognize that the article provided a partial perspective: the projects, ideas and opinions of a few intellectuals committed to architectural design and the development of a modern urban order in the first half of the 20th century, and for whom technical acts of this type were a means of eradicating the burdens of the ancient régime, insalubrity and illiteracy, from the lives of the popular classes whom they viewed with contempt. At all times I indicated that things could happen in a different way from that planned by those intellectuals, as suggested by the photograph of the wooden sheet hut in the Industrial neighborhood, and the divergent gesture of the children in the mural by Pablo O'Higgins in the Emiliano Zapata school, but there is a lack of studies that provide us with the testimony, the perception, the experience of inhabiting the new school architecture on the part of those for whom it was intended, which constitutes a methodological challenge for the history of school architecture.

REFERENCES

Aragón, A. (1900). Función de los Ingenieros en la vida social contemporánea. El Arte y la Ciencia, revista mensual de Bellas Arte e Ingeniería, 2 (5), 73-74. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. (2015). Vidas desperdiciadas. La modernidad y sus parias. Paidós. [ Links ]

Benjamin, W. (2003). La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica, Editorial Itaca. [ Links ]

Bueno, Maria de Fátima Guimarães (2009). A história da educação: a cidade, a arquitetura escolar e o corpo, Cadernos do CEOM, 21 (28), 243-278. [ Links ]

Comité del Plano Regulador (1935). Informe que rinde el Comité del Plano Regulador integrado por el arquitecto Carlos Contreras, ingeniero José A. Cuevas y arquitecto Carlos Tarditi, a la Comisión de Planificación del Distrito Federal. Planificación, órgano de la Asociación Nacional para la Planificación de la República Mexicana, 3 (3-6), 59-72. [ Links ]

Contreras, C. (1928). Plano Regulador del Distrito Federal. Planificación, órgano de la Asociación Nacional para la Planificación de la República Mexicana, 1(13), 4. [ Links ]

Cordoví Núñez, Yoel (2012). Cuerpo, pedagogía y disciplina escolar en Cuba: dispositivos de control desde los discursos higienistas (1899-1958) . Tzintzun. Revista de Estudios Históricos, (56), 93-136. [ Links ]

DEN (1935). Censo de Población. 15 de mayo de 1930. Distrito Federal, Departamento de la Estadística Nacional. [ Links ]

Dussel, Inés (2019). La cultura materia de la escolarización: reflexiones en torno a un giro historiográfico, Educar em Revista, 35 (76), 13-29. [ Links ]

Fiorucci, F. y Rodríguez, L. (2018). Intelectuales de la educación y el Estado: maestros, médicos y arquitectos. Universidad Nacional de Quilmes. [ Links ]

González Mello, Renato y Dorotinsky Alperstein, Deborah (coordinadores) (2010). Encauzar la mirada. Arquitectura, pedagogía e imágenes en México 1920-1950, México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM. [ Links ]

Julien, Marie Pierre; y Rosslin, Céline (2005). La culture matérielle, París, La Découverte. [ Links ]

Lear, J. (2019). Imaginar el proletariado. Artistas y trabajadores en el México revolucionario, 1908-1940. Libros Grano de Sal. [ Links ]

Le Breton, D. (2011). Caminar: un elogio. Un ensayo sobre el placer de caminar, La Cifra Editorial. [ Links ]

Le Corbusier (1925). Vers une architecture, Les Éditions G. Crès et Cie. [ Links ]

Lombardo Toledano, V. (1928). “La supresión del Ayuntamiento Libre en el Distrito Federal”, en: Planificación, órgano de la Asociación Nacional para la Planificación de la República Mexicana, tomo 1, número 9, pp. 17-24. [ Links ]

Ortega y Gasset, J. (1992). La deshumanización del arte e Ideas sobre la novela. Velázquez-Goya, Editorial Porrúa. [ Links ]

Ortega y Gasset, J. (2004). Meditación de la técnica y otros ensayos sobre ciencia y filosofía, Madrid, Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Pani, A. (2003). Apuntes autobiográficos (II volúmenes) Senado de la República. [ Links ]

Poder Ejecutivo Federal (1931). Decreto que modifica la Ley Orgánica del Distrito y Territorios Federales. Diario Oficial, Órgano del Gobierno Constitucional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, LVXVII (47), 1-6. [ Links ]

Poder Ejecutivo Federal (1928-1929). Ley Orgánica del Distrito y los Territorios Federales. Diario Oficial, Órgano del Gobierno Constitucional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, LI-LII (47-4). [ Links ]

Poder Ejecutivo Federal (1933). Ley de planificación y zonificación del Distrito Federal y territorios de la Baja California. Diario Oficial, Órgano del Gobierno Constitucional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, LXXVI (14), 5-7. [ Links ]

Presidencia de la República (2018). Decreto por el que se declara monumento artístico la Escuela Primaria Emiliano Zapata. Diario Oficial de la Federación, 782 (14), 69-70. [ Links ]

Recio, Carlos Mario (2009). Escuela, espacio y cuerpo, Revista Educación y Pedagogía, 21 (54), 129-139. [ Links ]

Rodríguez Kuri, A. La experiencia olvidada. El Ayuntamiento de México: política y gobierno, 1876-1912. El Colegio de México, UAM-Azcapotzalco. [ Links ]

SAM (1934). Pláticas de arquitectura, 1933. Sociedad de Arquitectos Mexicanos. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Cultura (2016). Diario de los debates del Congreso Constituyente 1916-1917 (tomo 1). Secretaría de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México. [ Links ]

SEP (1932). Escuelas primarias 1932 en: Arias Montes, V. (Coordinador) (2005). Juan O’Gorman. Arquitectura escolar 1932. UNAM, UAM-Azcapotzalco. [ Links ]

Serres, M. (2011). Variaciones sobre el cuerpo. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Suárez y López Guazo, L. (2005). Eugenesia y racismo en México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

3In the history of education in Latin America, the human body -and specifically the child's body- has been studied through its representation in publications, books and school textbooks, the imposition of coercive measures and the generation and application of pedagogical strategies related to physical education and sex education. The hygienist policies, practices and discourses of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, aimed at the normalization of children's bodies through public schools, are the axis of its coverage. However, the relationship between the molding of the child's body and the materiality of the school - furniture, clothing, teaching materials and the building - are generally implicit, silent, incorporated [Julien and Roselin, 2005]. In the case of school architecture, fewer have explicitly addressed these shaping relationships. Among them, the links between architecture, pedagogy and hygiene stand out in the conformation of a regulatory and disciplinary intentionality of real estate on the physiology and expressions of children's bodies [Bueno, 2009; Recio, 2009; González and Dorotinsky, 2010; Cordoví, 2012]. In this article, comprised in what has been called the material turn in the historiography of education [Dussel, 2019], we suggest that the relations of the school building with the human body are relations of mutual molding that give rise to different possibilities.

Received: August 04, 2020; Accepted: October 14, 2020

texto em

texto em