Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.37 Belo Horizonte 2021 Epub 01-Mar-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469824977

SCHOOL SPACES AND ARCHITECTURES

ARCHITECTURAL SPACE AND THE REGULATION OF CHILDREN'S BODIES: CLASSROOMS, LATE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY

1PhD in History. Research Professor at the National Pedagogical University. Mexico City, Mexico. <r_menindez@yahoo.com.mx>

The decade of the nineties of the nineteenth century represented an important moment for education in Mexico, driven by a group of teachers, hygienists, doctors, architects and educators who proposed and promoted changes in primary education. One of these changes was in the area of school space, that is, in the construction of school buildings. The objective of this article is framed in a context of modernization promoted by the government of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), and seeks to study the transformation that the school space underwent, focusing the analysis on the classrooms, a place where children spent an important part of their lives and where children's behavior was organized. The school building was conceived as a space of protection and formation for the child's body, which was accompanied by furniture, school materials and textbooks. The writing of this work is supported by sources from the Historical Archives of Mexico City, Public Instruction, School Plans; Newspaper Library of the National Pedagogical University, Mexico; Digital Newspaper Library (UNAM).

Key words: Classrooms; Porfiriato; architectural space; children's bodies

La década de los noventa del siglo XIX representó un momento importante para la educación en México, impulsado por un grupo de maestros, higienistas, médicos, arquitectos y educadores que se plantearon y promovieron cambios para la educación primaria. Uno de estos cambios se dio en al ámbito del espacio escolar, es decir en la construcción de edificios escolares.

El objetivo de este artículo se enmarca en un contexto de modernización promovida por el gobierno de Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), y busca estudiar la transformación que el espacio escolar experimentó, centrando el análisis en las aulas, lugar donde el niño pasaba un importante tiempo de su vida y en donde se daba el ordenamiento de los comportamientos de los niños. El edificio escolar se concibió como un espacio de protección y formación para el cuerpo del niño, el cual fue acompañado por el mobiliario, los materiales escolares y los libros de texto. La escritura de este trabajo cuenta con el soporte de fuentes de los Archivo Históricode la Ciudad de México, Instrucción Pública, Planos de escuelas; Hemeroteca de la Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, México; Hemeroteca Digital (UNAM).

Palabras clave: Salones de clase; porfiriato; espacio arquitectónico; cuerpo de los niños

Os anos noventa do século XIX representaram um momento importante para a educação no México, impulsionado por um grupo de professores, higienistas, médicos, arquitetos e educadores que consideraram e promoveram mudanças no ensino fundamental. Uma dessas mudanças ocorreu no campo do espaço escolar, ou seja, na construção de prédios escolares. O objetivo deste artigo é, enquadrado em um contexto de modernização promovido pelo governo Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), estudar a transformação que o espaço escolar sofreu, focalizando a análise nas salas de aula, onde a criança passava um período importante de sua vida e onde eran dados os ordenamentos sobre o seu comportamento. O prédio da escola foi concebido como um espaço de proteção e treinamento para o corpo da criança, acompanhado por móveis, material escolar e livros didáticos. A redação deste artigo se baseou em fontes do Arquivo Histórico da Cidade do México, Instrução Pública, Planos escolares da Hemeroteca da Universidade Nacional Pedagógica do México e da Biblioteca de Jornal Digital (UNAM).

Palavras-chave: Salas de aula; porfiriato; espaço arquitetônico; corpo infantil

INTRODUCTION2

The schools that were founded in the capital of the country throughout the 19th century were generally established in rented houses and neighborhood rooms, therefore, the conditions of the schools were precarious. The educational authority was aware of the deficiencies, but lacked the economic resources to address the situation, which is why the practice continued for several years. When the government of General Porfirio Díaz took office in 1876, most of the schools in Mexico City presented a deplorable panorama, particularly their material aspect was a cause for criticism and complaints. However, two situations would be fundamental for the transformation of school spaces. The first was the celebration of the Pedagogical Hygienic Congress of 1882, and the second was the conclusions of the Public Instruction Congresses of 1889-1890 and 1890-1891, which were considered by the educational policy of the Diaz regime that paid special attention to the construction of school buildings under modern standards. The construction of school buildings followed the recommendations of the hygienists, and the educational bureaucracy joined this interest since they needed to solve the issue of the incorporation of children to schools, in the face of an increase in population and a legislation that promoted compulsory schooling.

The objective of professionals and politicians was to establish an education linked to the industrialization process that was being imposed in the world. From this point of view, the aim was to train hard-working, healthy, clean citizens, respectful of the authorities, disciplined, orderly, and lovers of their homeland. The space for this purpose was the school, and therefore the schooling process was favored. The political will and the favorable economic situation allowed investment in the construction of schools and the provision of school furniture and materials, especially in urban areas; rural areas were included in a limited way by this process of transformation.

THE MODERN SCHOOL AND ARCHITECTURAL SPACE

The school at the end of the twentieth century was the place for the intellectual, moral and physical formation of children, these ideas were nourished by the theoretical reflections of some authors, as was the case of Herbert Spencer, "expresses his preference for a scientific education as opposed to the literary and artistic education customary at the time. He accepts science as the center of all education and indicates the learning process, recommending that it be taught in accordance with evolutionary postulates, [...] in the moral sphere, he takes up Rousseau's ideas on consequences or natural reactions as the only initial basis of the discipline (BERRIO, 1996, p. 159) and also attaches great value to physical education, since the preservation of health is a duty that should be promoted. Spencer's principles of intellectual education are complemented by Pestalozzi's ideas regarding the pedagogical value of play. The educational project of the Porfiriato finds a strong component of the new pedagogical and even sociological currents such as positivism, which can be observed in the school architecture as the bearer of a discourse. In these school spaces not only school contents were learned, i.e. geometry, reading, writing. They also learned forms of behavior, conduct and values. In this sense, Martinez Boom notes "the school's own actions consist of: distributing space in such a way that it orders, differentiates and even integrates in order to provide regulation and surveillance mechanisms; it also orders time by subdividing it, programming the act, decomposing the gesture" (2014, p. 39).

The idea of schooling children and keeping them in confined and monitored spaces is not just a mere pedagogical approach. In this regard Michel Foucault points out "[...] the school building should be an operator of behavior, [...]"; the building itself should be an apparatus for surveillance (1978, pp. 177-178). We can say that it is also a well-studied political approach and, in this sense, the educational project was and is today directly linked to a State project. Antonio Viñao mentions:

Bureaucratic rationalization -division of time and school work- and the rational management of collective and individual space make the school a place where the location, displacement and encounter of bodies, as well as the ritual and the symbolic, take on special importance. It is a segmented, parceled institution, surveillance and control -coordination- is only possible through communication [...] the spatial visibility of unifying symbolic elements, the ritualization of the main activities that take place in it (1993-1994, p. 28).

Following this guideline, states in both Europe and Latin America and some authors have reported the case of Australia and Great Britain. David Kirk notes that "In the late nineteenth century schooling had two main institutional imperatives: the first was the imposition of social order so that the school itself could function effectively. The second was its orientation to create docile as well as productive citizens to contribute to the prosperity of the economy and the propagation of the race (in Foucault's words, the [docility-utility]" (1978, p.40), created and organized a whole institutional framework (which required a legal framework) and at the same time promoted national systems of public instruction. Thus, the right and obligation to elementary education was considered by most of the world's legislations. In other words, school and compulsory education went hand in hand in order to achieve the education of children. Compulsory schooling was decreed by the Mexican State since 1865 with the Law of Public Instruction of December 27, 1865, which stated that primary education is compulsory. Later, on December 2, 1867, with the issuance of the Organic Law of Public Instruction by Benito Juarez, it was noted that primary education in Mexico is secular, compulsory and free (MENESES, 1998, p. 190, 222). The issue of compulsory education was a defining factor for the growth of public schools. As the 19th century progressed, and particularly during the administration of Porfirio Díaz, the number of children attending school increased not only because of compulsory education, but also because of demographic growth and urban growth. Between 1877 and 1911, there were 62 elementary schools, and by 1911, 418 were reported. This was the case in Mexico City, but there was also an important growth in other states.

The school environment was especially cared for by hygienists, teachers, pedagogues, architects, doctors and authorities, and the design, planning and construction of school buildings began. As we have already pointed out, pedagogical ideas coming from Europe influenced the policy on school spaces. Authors such as Juan Enrique Pestalozzi, with his objective method, introduced the term intuition (DIAZ, 1986), defined as the creative and spontaneous act through which the subject is capable of representing the world around him; all intellectual activity brought the forms of thought into direct contact with everything within the child's reach. According to this method, the child's activity should be productive, the child should be the center of school activity, he should learn. Another influence on the conception of school spaces came from the ideas of Frederick Fröbel, which complemented those of Pestalozzi, by introducing play as an element for the stimulation of learning. School buildings considered spaces for this purpose, such as playgrounds, play areas and gymnastics rooms. This second author contributed to pedagogy from the child's point of view and emphasized that "intuition, the starting point of all teaching, is made up of three elements: form, number and name. With them, meaningful learning of all subjects is linked (BERRIO, 1996, p. 89).

At the end of the 19th century, the construction of school buildings was not only a proposal, it had become a necessity in view of the demand for schools for a large number of children, as well as the arrival of the graded school. Therefore, school buildings were required to be constructed and as Marianne Helfenberger points out, "the implementation of compulsory schooling in the 19th century gave rise to intense debate and innovative solutions for school buildings in which masses of children's bodies had to be accommodated in order to solve logistical and bureaucratic challenges" (2016, p. 1).

The modern school took its first steps, its protagonists: students, teachers, principals, supervisors, janitors, janitors, cleaning staff at the time called "servants", were housed in a specific space, the school building. The school construction project considered all the necessary spaces to accommodate the students for several hours (the children spent between six and seven hours at school, the schedules began at 8:00 a.m. and ended at 5:00 p.m. with two hours for lunch), conceiving each space with a specific function. There were classrooms, patios, bathrooms, water troughs, playgrounds, gardens in some cases, libraries, the principal's room, kitchen, among others. The school space was not only conceived to accommodate the aforementioned school actors, the fundamental thought was in the creation of a disciplinary and control space, following Martínez Boom, "its daily practices insistently aim to distribute in space, order in time, concentrate in its form, socialize in play, compose in bodies a productive force whose effects represent economic and political utility" (2014, p. 41). The conception of a school building implied a series of aspects to consider and all of them important without being one less than the other: economic, pedagogical, disciplinary, hygienic, medical, architectural, technological, artistic, ideological. All these aspects interact in order to establish a school building model that obeys a temporality and expresses a social discourse. David Kirk points out "The design of school buildings, and in particular the organization of classrooms, created spaces that students could occupy only in specific ways, legitimizing certain behaviors and prohibiting others" (2007, p. 42).

We can note that every architectural space communicates a thought and a rationality, as Agustín Escolano points out: "it is a program, a kind of discourse that institutes in its materiality a system of values, such as order, discipline and vigilance, some frameworks for sensory and motor learning and a whole semiology that covers different aesthetic, cultural and even ideological symbols" (1993-1994, p. 100). The conceptualization of school spaces is not neutral, it is nourished by key elements, where pedagogy, politics, architecture, economics, hygiene are intertwined to build a model and an educational discourse. For example, the graduate school needs a specific school space that houses many students of different ages and grades. According to Escolano, "disciplinary specialization is an integral part of the school architecture and is observed both in the separation of classrooms (grades, sexes, student characteristics) and in the regular arrangement of desks (with corridors), facts that facilitate the routinization of tasks and the economy of time (1993-1994, p. 100). The formation of a child is not only in the plans and contents of the curricula, in the textbooks, in the subjects, in the school materials; it is also found in the space; it educates and transmits values, meanings, rituals, behaviors, conducts and visions of the world. In this sense, as Georges Mesmin notes, "school architecture is a silent form of teaching, architecture is an educator" (1973, P. 104).

In Mexico, all this packaging of ideas is shown in the policies and discussions of educators. There were two transcendental meetings for Mexican education, the first was the celebration of the Hygienic Pedagogical Congress (1882), which was convened by the Superior Health Council. Doctors and teachers participated, the "eminent hygienist Ildefonso Velasco during the inaugural speech stated: education exclusively intellectual, without attending class schedules, conditions of the bedrooms, the dining room, ventilation, illumination, the temperature of the establishment the appropriate school furniture, such as tables and seats, books and the type of paper as well as the diseases or alterations that these aspects cause in children" (CERINO, 2016, p. 85-86). The congress placed on the discussion table the attention to children's bodies in relation to their link and interaction with the school space, the books, the furniture, the teaching method, the school activities and work, and the avoidance of children catching diseases transmitted by other children. Therefore, the distance and distribution among schoolchildren was also taken care of. Everything was aimed at taking care of the children's health and thus having strong and employable future citizens.

The second major meeting was the organization of: The Congresses of Public Instruction (1889-1890, 1890-1891). These emphasized their discussions around the pedagogical theme of the school building, the classroom and all the spaces of the school. These discussions had an impact on educational policy, which considered various issues, including school architecture. Guidelines and regulations were established for the school space and the attention to the children's bodies, their distribution and movement in this space.

The school required an area designed especially for such use, with the intention of linking discipline, the values of liberal society in the school place, but above all the space becomes a social laboratory. Thus, school architecture was conceived as the expression of the type of education that was desired to be projected not only to children and teachers, but to the entire nation. The school was to be seen as the space of knowledge, order, cleanliness, sanitation, work and under that logic, the first school buildings were designed with majestic constructions that became emblematic places, in order to show the importance given to teaching, but above all, the idea was to convince how good it would be to have children in schools. However, most of the schools did not have such complete buildings, some were more modest and even very austere. What does stand out is that the school established in a certain area undoubtedly gave a certain connotation to that place, both in terms of the school and the impact on the community. The State's project promoted a school architecture that expressed the ideals of modernity, in accordance with architectural ideas mainly from France.

The construction of school buildings in the country was the result, as we have already mentioned, of diverse and complex historical, political, economic, medical, pedagogical, hygienic and cultural processes, which had expressed the values of the time and the place that society assigned to childhood. The physical spaces also responded to the predominant type of pedagogy and the forms and methods of teaching. Thus, each method had required a type of physical space to develop its educational methodologies, whether it was a house, a neighborhood room or a large classroom that could accommodate many children. For example, the Lancasterian or mutual teaching school system required large spaces and a certain type of furniture, long benches where more than 20 children could sit, little or no decorations, perhaps only a clock on the wall and the typical accessories of such a system.

On the other hand, schools run by a single teacher taught their classes in a single room to very few students, had little furniture -which in most cases was not appropriate for school use- and their teaching methods were based on the use of memory. For their part, municipal schools tended to leave the neighborhood room to establish themselves in houses or neighborhoods that included several rooms, as well as a kitchen, a room for the director and, in some cases, even bathrooms for the children. The director lived in the school itself. In the plans of the schools, we always observed a space for this purpose. However, a problem arose, since the teacher's family also lived in this reduced space and this was a reason for criticism from teachers and officials who expressed their disagreement in pedagogical magazines, as was the case of the article published by the teacher Lucio Tapia, "The teacher's family should not be housed in the school premises"3.

As new pedagogical and hygienic ideas were introduced, the school space tended to be transformed, gradually giving way to larger spaces, decorated, with adequate furniture, distribution of the area to include a patio, bathrooms, water troughs and other places for the care and organization of the children during the time they were in school, and here we have the fundamental axes for the creation and conception of the school: time and space, which we will see present in the regulations and in the educational policy from the nineteenth century to date.

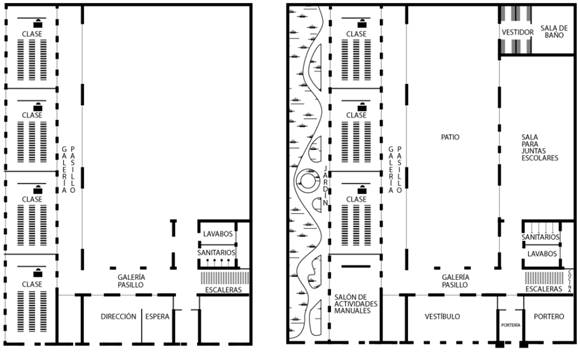

The classrooms represented the most important place in the whole school; they were strategically placed to observe, care for, supervise and order the children. Therefore, the architectural plan places this space as a priority. Another point to highlight is the movement within the space and where the courtyard occupied a central role, as it was placed in the center and all classrooms maintained a connection with the central courtyard (See image 1). The new guidelines for the school space and for the attention of the children's bodies became a reality with the construction of these school buildings.

Source: Prepared by the author and Mayela Crisóstomo with data from Normal Teaching Magazine (Revista La Enseñanza Normal), Year I, No. 1, 1904.

Image 1:

Translation of Left Image: School Project - Upper Floor Type Scale 1:100, Classroom, Directory, Waiting Room, Corridor Gallery, Stairs, Washbasins and Toilets

Translation of Right Image: School Project - Ground Floor Type Scale 1:100, Classroom, Garden, Corridor Gallery, Manual Activities Room, Lobby, Entrance, Doorman, Stairs, Kitchen, Washbasins and Toilets, School Meeting Room, Dressing Room, Bath Room

What is it in the State's interest to take care of its future citizens? Everything points to the care of children's mental and physical health. Following this logic, a school health policy was promoted, where hygiene established the guiding line that included: vaccination, medical check-ups and treatments and especially the teaching of body care through cleanliness, indications were given on bathing, washing and ironing clothes4, exercise and the teaching of gymnastics, a subject that was introduced in the curriculum of elementary and higher education since 1886 and at the same time was introduced as a subject in the curriculum of the normal school (MENESES, 1998).

All these ideas of attention and care for the body were reflected in the programs of various subjects such as natural sciences, physiology and hygiene, civics, morality, urbanity, anatomy, and reading. Special mention should be made of the textbooks that were written to teach these school disciplines, some of which were written by doctors, writers, but also by teachers who graduated from normal schools, as was the case of the Escuela Normal de Maestros in Mexico City, Orizaba and Xalapa. Among some of the books that circulated in the schools we have the books written by doctors: Dr. Luis E Ruíz, Elements of natural history, Hygiene booklet (Elementos de historia natural, Cartilla de Higiene); Pedro García Alcántara, Treatise on school hygiene, Theoretical and practical guide for the use of inspectors, teachers, boards, architects, doctors and all those involved in the hygienic regime of schools, construction of premises and furniture, and acquisition of scientific material for the same. (Tratado de higiene escolar, Guía teórico- práctico para el uso de los inspectores, maestros, juntas, arquitectos, médicos y cuantas personas intervienen en el régimen higiénico de las escuelas, construcción de locales y mobiliario, y adquisición de material científico, para las mismas); George G. Goff, Children's health (La salud del niño); Rafael de la Peña, Notions of higiene (Las nociones de higiene). And the textbooks written by teachers: Toribio Velasco, Knowledge of nature, Human subjects (Conocimiento de la naturaleza, Temas sobre el hombre); Luis G. León, Physiology and Hygiene, School Hygiene Primer and the Elements of Hygiene and Domestic Medicine. (Fisiología e Higiene, Cartilla de higiene escolar y los Elementos de Higiene y medicina doméstica); Celso Pineda, The strong child: readings about hygiene., written for children (El niño fuerte: lecturas acerca de la higiene, escritas para niños); this same author continued to address the issues of citizenship education and wrote the book The citizen child. Readings on civic instruction (El niño ciudadano. Lecturas acerca de la instrucción cívica).

Ruggiano Gianfranco points out "about the case of schools in Uruguay that, the body has been schooled from the moment it became part of the curriculum" (2013, p. 67). The object of the whole approach was to have physically flexible citizens, with agility, muscular strength and disciplined. The school as a concept is materialized in a space such as the school building; there a series of practices, behaviors and knowledge are woven that begin with the child's body and its mobility in the school space.

CLASSROOMS AND THE REGULATION OF BODIES

How were the classrooms before the intervention of hygienism, how did the children move inside the classroom? Some articles published at the time, the reports of the schools that were presented in the reports of the City Council, presented a difficult and precarious panorama, especially for the schools that were in poor areas, without communication routes and lacking water. For these, the panorama was desolate, the overcrowding of the children attending classes presented conditions of lack of cleanliness, hygiene and skin diseases or infectious-contagious diseases.

Some teachers, concerned about the issue and to show teachers and parents the need to address this problem, wrote important articles that were published in pedagogical magazines, as was the case of Primary Education (La Enseñanza Primaria), as well as in some national newspapers. Among some of the titles are the following: Luis de la Brena, Reflections on the medical inspection in the official schools of the Federal District, Personal hygiene. (Reflexiones sobre la inspección médica en las escuelas oficiales del Distrito Federal, El aseo personal); Jesús Sánchez, Medical Inspection and School Hygiene (La inspección Médica y la higiene de la Escuela); Celso Pineda, Principles of Hygiene, Tuberculosis at school. (Principios de Higiene, La tuberculosis en la escuela); John J. Cronin MD, The physician in the official school. The beneficial results of medical examination in children (El médico en la escuela oficial. Los benéficos resultados del examen médico en los niños); Rodolfo Menéndez, The school anti-tuberculosis defense; El Mundo Newspaper, Hygiene of sight, Light, reading and writing (, La defensa antituberculosa escolar; Periódico El mundo, Higiene de la vista, La luz, la lectura y la escritura) 5.

When legislation on educational hygiene was established (derived from the hygienic and pedagogical congresses), some schools had more adequate spaces, but many others did not achieve the changes proposed by the hygienists. In reality, there was a great differentiation between schools, depending mainly on their location. Those that were located in the center of the city or close to communication routes, where the streetcars passed, had better conditions, for example: they had more space, classrooms for each grade, a patio, kitchen, teacher's bedroom, and if the school-house allowed it, a small library was placed. In contrast, the schools that were located in the outskirts of the city had limited space, and most of these schools were located in areas that were not recommended by hygiene specialists, since some of them were next to cemeteries and jails, and some were even located inside the cemetery itself.

The promoters of hygiene and modern pedagogy saw school hygiene as part of public hygiene, hence the importance given to school buildings and their internal distribution, including classrooms. In this regard the following comment:

It seems useless to us to say that the place where a building is to be erected must be healthy, dry; this is an illusion; they must be high, isolated, far from any building or place that could be harmful as hospitals, cemeteries; they must be perfectly ventilated and receive good light for which they must be far from any object that could prevent this. Regarding the building, the first condition is that it be of a single floor so that it has ventilation [...] the classrooms; these must have as first condition, that of being ample so that they can contain the necessary air capacity and that this can be renewed easily because where the air is not renewed it becomes unbreathable, takes a bad smell and from here comes heaviness, headache and other annoyances that many times are attributed to the intellectual work to which the pupil is subjected. The walls should not be papered, nor painted with oil and stucco; the best thing is, in Mexico, where all the low buildings are humid, to cover the walls with tiles, these diminish the humidity. As for the capacity of the classrooms, it should be in relation to the number of students, but this should not be prolonged indefinitely. As for the illumination; a darker place must be sufficiently illuminated, so that it is possible to read and write, for this it is necessary that there is a great number of windows that occupy from a fifth to a sixth of the total surface of the walls: this varies much, because on hygiene as in all the concrete sciences there is great diversity of opinions, but what has been said is what is generally accepted by the Councils of Hygiene6.

The subject of school spaces gained importance in the urban strata of Mexican society at the end of the century, motivating teachers, doctors, architects, and hygienists to publish several articles, mainly in the magazines Normal education, The modern school, Annals of school hygiene, Primary Education, and Mexican School (La enseñanza normal, La escuela moderna, Anales de higiene escolar, La enseñanza primaria, y la Escuela mexicana).

Emphasis was given to writing articles on classrooms, dust, health effects due to the proximity of factories, light, ventilation, air, crowding, among others. The outstanding teacher Gregorio Torres Quintero wrote an article entitled "The Classroom" (“El salón de clase”) in which he presented to teachers and children what this space was, noting all the details, the materials that could be used for construction. The article fulfilled a double function: to show what a classroom was and to teach in the subject of lessons of things, which was taught in the curriculum of primary education. Through this description we can know what these school spaces were like and in particular the classrooms, and he noted:

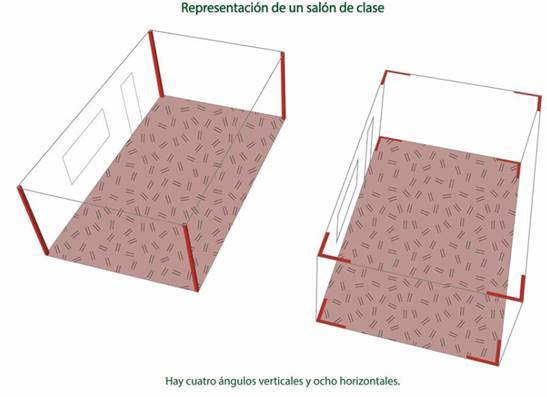

The classroom has a floor, walls and ceiling. The walls are vertical, the floor and ceiling are under our feet, the walls around us and the ceiling above our head. There is wall from the front, from the right, and from the left and from the back. The whole floor, like the walls and ceiling, are flat surfaces. There are six of them. Two planes that meet form an angle (an example is presented in Image 2). There are four vertical and eight horizontal angles (See Image 3). Three planes that meet form a corner: there are eight corners. The floors can be made of wood, brick, tiles, stone, cement, etc. Some are covered by carpets. The walls may be upholstered or painted, or have no covering at all. They are constructed of wood, sod, adobe, brick, stone, etc. Some ceilings are covered by a ceiling. They can be made of brick, wood, thatch, zinc, tile or slate. They are flat, pyramidal, conical, etc. (they can be seen in Image 4). The hall also has doors and windows. Air and light enter through them. In some ceilings there are skylights or lanterns. The living room contains furniture. To build a salon requires not only masons, but also various other types of workers7.

Professor Torres Quintero offered a splendid and very detailed explanation of a classroom and a school; from the type of materials (wood, brick, stone, straw, zacate tiles, adobe, paint, etc.), the structural organization (floors, walls, windows, ceilings, doors, etc.), the distribution of the elements that make up the space and the actors involved in its construction. The article shows a description from the point of view of a teacher, not that of an architect. His objective was to teach and show his students what a classroom and a school were; let us think that many of these children had never been in a classroom or a school, especially those from rural or poor areas of the cities. Therefore, this description was focused primarily on the child. Professor Quintero did not intend to give directions for the construction of school buildings; it is not a class for the construction of school buildings. It was really a rigorous approach to what he saw, it was an observation of how a teacher structures the idea of a classroom.

While it is a very thorough writing, his narrative goes further by showing not only children but also teachers, principals, parents and even educational and political authorities, the importance of building schools with materials, dimensions, places and specific environments for the movement of children and their learning in optimal space. An article that denotes the interest of teachers in the subject of school architecture and its links with teaching subjects, as was the case of the subject of lessons of things.

Source: Prepared by Engineer Víctor Alberto Rivera Álvarez with information from The Primary School Magazine (Revista La Enseñanza Primaria) August 15, Mexico, 1901.

Image 2

Image Translation: Classroom, There are six, Two planes that meet at an angle.

Source: Prepared by Engineer Víctor Alberto Rivera Álvarez with information from The Primary School Magazine (Revista La Enseñanza Primaria) August 15, Mexico, 1901.

Image 3

Image Translation: Representation of a classroom, There are four vertical angles and eight horizontal ones.

Source: Prepared by Engineer Víctor Alberto Rivera Álvarez with information from The Primary School Magazine August 15, Mexico, 1901.

Image 4

Image Translation: Classroom ceilings, Roofs are flat, pyramidal and conical.

The policy on the construction of school buildings insisted, in particular, on the measurements of classrooms, ventilation and air in classrooms, school furniture, the distribution of spaces, construction materials for school buildings and hydraulic installations, among others. Another of the topics of various works was the illumination of classrooms, aspects that concerned hygienists and ophthalmologists, who wrote detailed papers on the subject and that reflected in part the great influence of Western countries. An example of such articles was the following:

On one point the hygienists agree: in rejecting completely the lighting provided by open windows, with equal dimensions on the two lateral walls of the room, because this produces on the reading and writing paper, varied games of light and shadow highly harmful to the sight. In rejecting bilateral lighting, opinions are only divided on this other point: whether the lighting should be unilateral left only or bilateral differential with maximum left. In Germany and the United States, the opinion of oculists and hygienists is in favor of left unilateral illumination, as being the most suitable for giving an exact idea of the shape of objects and as not producing the crossed rays and variations of sunlight of illumination from both sides. To this question of lighting, two others are intimately linked: the orientation of the rooms and their dimensions. Regarding the orientation, I must say that the orientation to the West is absolutely rejected, for being the worst of all: this precept is easy to obey in the construction of rural schools where it is easy to choose the orientation, but in the cities it is more difficult, without being impossible, for having to adapt to the direction of the streets. To obtain good lighting, it is necessary that the surface of the windows represents at least 1/3 of the surface of the floor, and that everything is arranged in such a way that each pupil can see at least 0.30 centimeters of sky from his table-bench, starting from the upper edge of the window. Rules that it is necessary not to forget: it will never be allowed that the light falls directly on the faces of the children, for being this highly harmful to them. Night classes should be avoided as much as possible: for small children. I have said that to the question of lighting is intimately linked another: that of the dimensions of the study rooms. So that all the children of a class can hear well the teacher and see well from their seat, the signs and letters drawn on the blackboard, it is necessary that the dimensions of a room do not exceed 9 to 10 meters of length by 6 or 7 meters of width and 4.5 to 5 of height, which gives capacity for up to 50 children, thus avoiding the accumulation of students, with all its fatal consequences8.

Hygiene specialists recommended that there should be one classroom for each grade and, if there were a high number of children per level, then it was recommended to have two classrooms for each grade; therefore, these houses should have a specific space for each activity. In relation to this point, the Public Instruction Commission of the City Council, by agreement, established the following:

As far as possible, the organization of the municipal schools shall be improved.

The main bases under which the new schools will be organized will be the following:

Whenever a new school is established, the Town Council will be consulted on the respective expense.

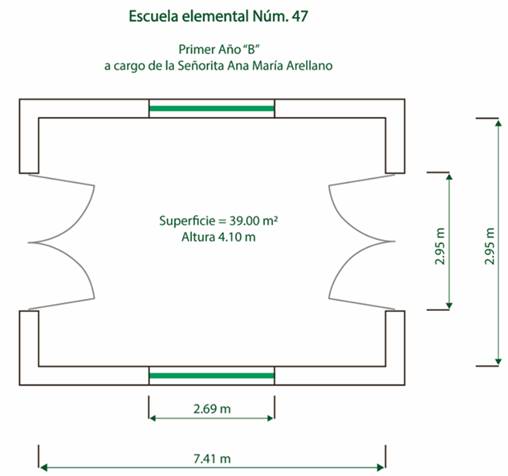

Such was the case of Elementary School No. 47, which in 1898 had an enrollment of 198 children and by 1905 increased to 344. The school had two classrooms per grade and the largest number of children was concentrated in the first year with 70 students10. This school had an important growth rate and was considered one of the large schools. In addition, it was one of the first to consider the distribution of classrooms and the measurements they should have, so that light and ventilation would be adequate. Also, this school had several exits to prevent children from getting hurt. The following are the measurements of each of the classrooms, as well as the number of doors and their orientation. This is part of the obsession with light, air and ventilation. It can be seen in Image 5.

Both doctors and architects considered that the classroom was the center of the school, so that is where most of the changes and remodeling suggested by the hygienists were deployed, although the 1 m2 or little more than 1.25 cm. between each student. In view of the demand due to the demographic increase, spaces had to be made available for the installation of schools, and remodeling work began, which included painting them white, changing the glass, fixing doors, fences, patios, etc.

Although the physical space of the schools was given special attention, it was intimately related to another topic of interest: discipline and control of the bodies in the classroom. The behavior of children in the school space was considered by the Pedagogical Hygiene Congress. Some points were recommended and it was pointed out that "the student will be subjected, as far as possible, to the method called discipline of consequences, and it will be sought that the student contracts the habit of doing good. The educator will not use this regime, whenever the actions of the children may cause them serious consequences". (MENESES, 1998, p.366). The theme is pursued with concrete actions and very soon they were put into practice in schools.

Source: Prepared by the author and Engineer Víctor Alberto Rivera Álvarez with data from AHCM, Public Education Branch, no. 2548, exp. 6, April, 1906.

Image 5

Image Translation: Elementary School Num. 47, First Year “B” under Ms. Ana María Arellano, Surface, Height

The classroom is the place where children will have their greatest interaction. Therefore, it is in that place where cleanliness, air, light and order will have to be taken care of and this implies having adequate furniture, in order to allow better learning. Writing, reading, attention to the teacher, visualization of the blackboard, everything was related to the school building and its conditions. Several articles were also written about these topics in the pedagogical magazines of the time, for example: Gregorio Torres Quintero's “The Blackboard” ("La pizarra") published in the magazine La enseñanza primaria (Primary School).

All these elements must prevail in order to be a teaching space for the child, a space of construction of a new citizen and of the values that will give him a vision and location as a citizen child, who must be clean, healthy, orderly, disciplined, obedient, hardworking, compliant, punctual, respectful of the authorities, lover and defender of his homeland.

The relationship between body and school building leads us to several approaches to the construction of the body of school-age children, which allow us to delve into the way the body is distributed in the school, particularly in the classroom, and this is linked to school furniture and materials. The issue of furniture highlights and enriches this discussion around the regulation of children's bodies (see the works of CORNELIA DINSLER / DANIEL WRANA, 2016) the spatial location of each child, at what distance each child should and could be placed in the classroom, for this purpose they had a desk specially designed for this purpose, the child becomes a number, an important figure for the State; from the figure would depend the budgets and supports to schools.

As part of the classroom organization, "the desks were arranged so that all students faced the blackboard and the teacher at the front of the classroom. It was easy to recognize in this type of organization the power relationship" (KIRK, 2007, p. 44).

The architect, the doctor and the teacher represented prominent figures in the educational scenario. Their function, the health of children's bodies. A whole international organization designed the conceptualization of order, discipline, docility, regulation of children. The school building is conceived as a space of protection and training for the child's body, it is a separate place, enclosed to teach a new model of behavior and moral and physical. The children formed in the new schools with modern spaces, furniture, methods and textbooks will form the new generations of Mexicans of the recently arrived XX century.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The school space and especially the school architecture was part of the modernization program promoted by the government of General Porfirio Díaz. It sought to reorganize and clean up the school space in order to establish a new rationality for school life. Schools in Mexico were subject to an internal arrangement, which tried to delimit and separate school spaces and children. In order to separate them from the poverty, disease, hunger and backwardness identified with this problem, they were separated from the closed doors of the school and classrooms.

School architecture was defining from government regulations, the type of buildings that would serve as a model for the design of school spaces and prevailed for several decades of the twentieth century. The classrooms were its core; they became the school's axis of power, as it was in this space that the child was pedagogically, socially, mentally, physically and ideologically formed.

The premises of school hygiene were based on the idea of separating the healthy child from the sick child, whether physically or socially. To isolate poverty, which was the carrier of the disease and had to be treated. Therefore, it was necessary to delimit, mark, segregate, isolate, delimit, separate and control. Sick children had to be confined in special schools, until they were free of any disease or illness, they could be reintegrated into the space of the healthy. In order to have a healthy and homogeneous society, Spencer's approaches were present in this conceptualization of isolating misery and disease and building a society that only accepts the healthy. In the school building, the spaces destined for cleanliness were well defined and occupied a central role in the school plan: bathrooms, toilets, sinks, bathrooms, dressing rooms, water troughs. Cleanliness and hygiene rules had to be taught in the school in a practical way. The presence of doctors, teachers and pedagogues had the task of monitoring and controlling children's bodies and minds, and this body of specialists was the "recognized authority to make decisions regarding the possible health or illness of the child, discovering anomalies and pointing out deviations or irregularities" (DEL CASTILLO, 2006, p.115). Legislation and regulations regarding school buildings were especially attended to by the State in order to educate the child from a space, furniture and new pedagogical methods.

The classroom was a space where children's bodies were regulated and taught under new school practices and new paradigms. Pedagogy and medicine met to form and heal children's bodies, in a period that was defining for the construction of new approaches to children's bodies and their movement in the classroom and throughout the school building. These bodies in movement left the classroom at the conclusion of their studies or simply upon leaving school. These children were trained to be the citizens that the nation required; that is, clean, healthy, disciplined, orderly, obedient, docile, strong, standardized children who would serve their nation and allow the national welfare, the discourse of a whole regime and perhaps of a whole century.

REFERENCES

Archivo Histórico de la Ciudad de México, Ramo, Instrucción Pública, Planos de escuelas, 1904 [ Links ]

Memorias del Ayuntamiento. Ciudad de México, México, 1890 [ Links ]

Hemeroteca, Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. México [ Links ]

Hemeroteca Digital, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [ Links ]

REFERENCES

La enseñanza normal. D. F. Ciudad de México, México, 1904, 1906 [ Links ]

Anales de higiene escolar. D. F. Ciudad de México, México, 1893 [ Links ]

La enseñanza primaria. D. F. Ciudad de México, México, 1901, 1911 [ Links ]

DEL CASTILLO, A. Conceptos, imágenes y representaciones de la niñez en la ciudad de México 1880-1920. México: El Colegio de México, 2006. [ Links ]

BERRIO, J. La educación en tiempos modernos. Madrid, España: Editorial Actas, 1996. [ Links ]

CERINO, H. La higiene escolar en la formación de profesores durante el Porfiriato; una aproximación a su estudio a través de sus textos. En: ORTIZ, Francisco Hernández (Ed.) El patrimonio histórico educativo: Los libros de higiene escolar, pedagogía, economía doméstica y geografía en la formación del profesorado. México: Ediciones del Libro, BECENE, 2016, p. 78-97. [ Links ]

DIAZ, A. Pestalozzi y las bases de la educación moderna. México: El Caballito, 1986. [ Links ]

DINSLER, C. y WRANA, D. Transformation of the school desk and forms of subjectivation. En Ponencia, Panel Nr. 60.17 Regulating Human Bodies in Architectural Settings - Historical Perspectives on Educational Practices in School Buildings and Residential Rooms. ISCHENr. 38, Education and the Body, CHICAGO, 2016. [ Links ]

ESCOLANO, A. La arquitectura escolar como programa. Espacio-escuela y curriculum. En: HERNANDEZ DÍAZ, José María (Ed.), Historia de la Educación, Vol. XII-XII. Salamanca, España: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 1993-1994, p. 97-120. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, M. Vigilar y castigar. México: Siglo XXI Editores, 1978. [ Links ]

HELFENBERGER, M. The school building and the body in 19th century Switzerland. En: Ponencia, Panel Nr. 60.17 Regulating Human Bodies in Architectural Settings - Historical Perspectives on Educational Practices in School Buildings and Residential Rooms. Conference, ISCHENr. 38, Education and the Body, Chicago, 2016. [ Links ]

KIRK, D. Con la escuela en el cuerpo, cuerpos escolarizados: la construcción de identidades internacionales en la sociedad post-disciplinaria (traducido por Graham Webb). Ágora para EF y Deporte, nº 4-5, p. 39-56, 2007. [ Links ]

MARTINEZ, A. Escuela y escolarización. Del acontecimiento al dispositivo. En: Alberto Martínez Boom y José M. L. Bustamante Vismara, Escuela pública y maestro en América Latina. Historias de un acontecimiento, Siglos XVIII-XIX. Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros, 2014, p. 61-91. [ Links ]

MENESES, E. Tendencias educativas oficiales en México, 1821-1911. México: Universidad Iberoamericana/Centro de Estudios Educativos, 1998. [ Links ]

MESMIN, G. L’enfant, l’architecture et l’espace. Paris/ Francia: Caterman, 1973. [ Links ]

RUGGIANO, G. Escolarización del cuerpo y de los cuerpos. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, N.o 62. (1022-6508) - OEI/CAEU, 2013, pp. 57-68. [ Links ]

TORRES, G. El salón de clase. La enseñanza primaria. D. F. Ciudad de México, México, agosto, 1901, pp. 49-64. [ Links ]

VIÑAO, A. Del espacio escolar y la escuela como lugar: propuestas y cuestiones. En: HERNÁNDEZ DÍAZ, José María(Ed.), Historia de la Educación, Vol. XII-XII. Salamanca, España: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca , 1993-1994, pp. 17- 74. [ Links ]

2My thanks to Engineer Víctor Alberto Rivera Álvarez for his support in the preparation of the architectural images. The translation of this article into English was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG - through the program of supporting the publication of institucional scientific journals.

4An article on the subject, written by teacher María Martínez Ríos, " The fording and ironing ", Volume v. Mexico, April 15, 1906, was published in the magazine Primary Education. The teacher Teresa Guerrero, wrote the article entitled " Bathroom".

6‘’School Hygiene’’ (“Higiene escolar”) in Conference given by Dr. José Torres at the Mexican Society for Pedagogical Studies. The Mexican school (La escuela mexicana), t. VI, No. 16, October, 1893, pp. 277-278.

7Gregorio Torres Quintero, “The Classroom” (“El salón de clase”) in The Primary Education (La enseñanza primaria), 1901, August 15, p.7

8"Eye Hygiene in Schools" (“Higiene de la vista en las escuelas” ) in Normal education (La enseñanza normal), year 7, May, 1906, pp. 242-243.

Received: August 24, 2020; Accepted: November 07, 2020

texto em

texto em