Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 20-Jan-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469823861

Article

THE TEACHING OF INTERTEXTUALITY IN THE FINAL YEARS OF ELEMENTARY SCHOOL1

2Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) (Campinas State University). Campinas, SP, Brasil. <eldersonsantos@hotmail.com>

3Universidade Estadual do Ceará (UECE) (Ceará State University). Fortaleza, CE, Brasil. <helenamarinho.uece@gmail.com>

This paper aims to discuss possibilities of working with intertextuality in the final years of elementary school. Specifically, we seek to: a) analyze the characteristics of different intertextual processes (plagiarism, quotation, paraphrase, allusion, reference, parody and pastiche) in order to associate them with the teaching of intertextuality, and b) demonstrate, through exemplary analysis, different possible approaches to this phenomenon, considering the audience of the delimited teaching cycle and the distinct and diverse properties of each intertextual process considered. It is taken, for support of such research, Cavalcante (2019), Marcuschi (2008), Marquesi, Pauliukonis and Elias (2017) and Santos and Teixeira (2017) when discussing the approach between text and teaching. In Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010), the concept of intertextuality and how it unfolds through intertextual processes is discussed. Cavalcante, Brito, and Zavam (2017) are sources that ground the analysis of intertextuality for the sake of teaching, and, in Nobre (2014), it is possible to understand how each intertextual process is organized, constitutionally and functionally. In methodological terms, this is a qualitative research that, as to its objectives, can be classified as exploratory and, as to technical procedures, bibliographical. In this work, by dialoguing the authors mentioned above, a theoretical discussion is carried out which proposes the narrowing of the relationship between intertextuality and teaching, applying such discussion to a specific example, whose analysis contributes to guide the understanding of the investigation and to think about its use in the classroom.

Keywords: Linguistics; Portuguese Language; Text Production; Intertextual Processes; Elementary School

Objetiva-se discutir possibilidades de trabalhos com a intertextualidade nos anos finais do Ensino Fundamental. Especificamente, busca-se: a) analisar as características de distintos processos intertextuais (plágio, citação, paráfrase, alusão, referência, paródia e pastiche), a fim de associá-las ao ensino da intertextualidade, e b) demonstrar, através de análise em exemplário, diferentes possíveis abordagens desse fenômeno, considerando o público do ciclo de ensino delimitado e as distintas e diversas propriedades de cada processo intertextual considerado. Toma-se, para amparo de tal investigação, Cavalcante (2019), Marcuschi (2008), Marquesi, Pauliukonis e Elias (2017) e Santos e Teixeira (2017) ao se discutir a aproximação entre texto e ensino. Em Genette (2010) e Piègay-Gros (2010), discute-se o conceito de intertextualidade e como esse se desdobra através de processos intertextuais. Cavalcante, Brito e Zavam (2017) são fontes que fundamentam a análise da intertextualidade em prol do ensino, e, em Nobre (2014), é possível compreender como cada processo intertextual se organiza, constitucional e funcionalmente. Em termos metodológicos, trata-se de uma pesquisa qualitativa que, quanto aos seus objetivos, pode ser classificada como exploratória e, quanto aos procedimentos técnicos, bibliográfica. Neste trabalho, ao se fazer dialogar os autores supramencionados, realiza-se discussão teórica a qual propõe o estreitamento da relação intertextualidade e ensino, aplicando, em seguida, tal discussão a exemplário específico, cuja análise contribui para orientar o entendimento da investigação e para se pensar o emprego desta à sala de aula.

Palavras-chave: Linguística; Língua Portuguesa; Produção de texto; Processos intertextuais; Ensino Fundamental

Nuestro objetivo es discutir las posibilidades de trabajo con la intertextualidad en los últimos años de la escuela primaria. Específicamente, nosotros buscamos: a) analizar las características de diferentes procesos intertextuales (plagio, cita, paráfrasis, alusión, referencia, parodia y pastiche), para asociarlos con la enseñanza de la intertextualidade, y b) demostrar, a través del análisis en ejemplos, los diferentes enfoques posibles de este fenómeno, considerando la audiencia del ciclo docente delimitado y las distintas y diversas propiedades de cada proceso intertextual considerado. Marcuschi (2008), Marquesi, Pauliukonis y Elias (2017), Santos y Teixeira (2017) y Cavalcante (2019) se utilizan para apoyar esta investigación cuando se discute la aproximación entre el texto y la enseñanza. Genette (2010) y Piègay-Gros (2010) discuten el concepto de intertextualidad y cómo se desarrolla a través de procesos intertextuales. Cavalcante, Brito y Zavam (2017) son fuentes que apoyan el análisis de la intertextualidad a favor de la enseñanza, y en Nobre (2014) es posible entender cómo se organiza cada proceso intertextual, constitucional y funcionalmente. En cuanto a la metodología, esta es una investigación cualitativa que, en términos de sus objetivos, puede clasificarse como exploratoria y, en términos de procedimientos técnicos, bibliográfica. En este trabajo, al dialogar con los autores mencionados, se lleva a cabo una discusión teórica que propone el fortalecimiento de la relación entre intertextualidad y docencia, aplicando luego esta discusión a algunos ejemplos específicos, cuyo análisis contribuye a orientar la comprensión de la investigación y a piensar en el uso de esto en el aula.

Palabras clave: Lingüística; Lengua portuguesa; Producción de textos; Procesos Intertextuales; Educación Primaria

INITIAL CONSIDERATIONS

From the moment we are born to the end of our adult life, we are immersed in texts. Just as languages, in the way we use them, are constituted as social (human), making humans linguistic beings, the production and interpretation of texts seem to be intrinsic to language. In such a way, when we listen, speak, sign, read or write, we produce and interpret texts, (re)signifying and (re)constructing the world around us. In this spectacle that is our "being text in the world", a phenomenon has called the attention of researchers for decades: the relationships that texts establish among themselves. Then, in the Philosophy of Language, Literature and Linguistics, the study of intertextuality arises, which has in authors such as Bakhtin (1997), Beaugrande and Dressler (1981 apud VAL, 2006) and Kristeva (2005) its founders, and in several other studies, such as those based on Genette (2010), Koch, Bentes and Cavalcante (2008) and Piègay-Gros (2010), its unfoldings.

This research, in line with the reflections briefly dealt with in the previous paragraph, focuses on the intertextual phenomenon. Working to narrow the relationship between intertextual studies and Basic Education, we start from the following problem: how to work the intertextual processes with students from 6th to 9th grade in elementary school? We assume, based on the explanation of Cavalcante, Brito, and Zavam (2017), that the awareness about how to flag and mobilize the relations between texts can have positive repercussions on the production and textual interpretations of students, given that it expands and diversifies the possibilities of constructing the meanings of texts. We aim, therefore, a) to analyze the characteristics of distinct intertextual processes (plagiarism, quotation, paraphrase, allusion, reference, parody and pastiche), in order to associate them with the teaching of intertextuality, and b) to demonstrate, through exemplary analysis, different possible approaches to this phenomenon, considering the audience of the defined teaching cycle and the distinct and diverse properties of each intertextual process considered.

It is worth explaining that, while we recognize that with each new interpretation and textual production several other texts come into play for these acts to take place, we prefer, analytically, to see intertextuality from intertextual processes. This stance aligns us with researchers such as Cavalcante (2012), Cavalcante and Brito (2011), Cavalcante, Brito, and Zavam (2017), Faria (2014), Genette (2010), Nobre (2014), Piègay-Gros (2010), Souza-Santos (2020), and Souza-Santos and Nobre (2019).

In line with what was discussed in the previous paragraph, we use such category (that of intertextuality) to refer to the intertextual relations manifested/effected in texts through intertextual processes, such as: plagiarism, allusion, reference, quotation, paraphrase, parody, imitation, and appropriation of style (authorial and/or genre). Thus, although we are aware of the perspectives adopted by the founding researchers of the theme, we depart from them, referring to these textual relations intrinsic to the constitution of texts as dialogical, polyphonic, enunciatively heterogeneous relations, but not necessarily as intertextual (under the labeling of the term intertextuality)4.

We adopt this position because we understand that intertextual processes allow interlocutors to act on their texts in a more or less conscious way. Thus, we argue that the intertextual processes generate and modify meanings in texts, contributing to the argumentative constructions projected by the subjects that mobilize them, either through plagiarism, in which the subject incorporates another text to his own, using intertextual movements to camouflage this practice, passing through the citation, intertextual process in which we activate the other, generally, as a resource to authority, reaching the parody, phenomenon in which we generate a text from another, giving origin to a ludic manifestation (humorous, satirical, critical) and, above all, argumentative; without leaving aside, of course, the other intertextual processes.

Given the great importance of intertextuality for textual construction, we believe that this phenomenon can and should be worked with students since elementary school. Around this issue, we visualize that we can contribute with the works that sought to narrow the relationship between the intertextual phenomenon and Basic Education, especially with Elementary School, as well as we understand that, with this study, we corroborate to reduce the existing gaps in the area regarding this narrowing, because, although existing, the scientific productions that specifically focus on this discussion are still scarce.

As for the methodology, our study has a qualitative approach, according to Goldenberg (2004), because it seeks to interpret scientific phenomena considering social, historical, ideological, cultural factors, etc. As for the objectives, this work can be classified as exploratory. For this conceptualization, we rely on Gil (2002). The author explains that research whose objectives have this characterization is characterized by working towards the deepening of the discussion of problem(s) related to a certain theme(s), aiming to make it (them) more explicit. Exploratory research can also result in the formulation of hypotheses, which the testing will demonstrate the plausibility of explaining certain phenomena. Moreover, the scholar teaches us that exploratory research usually takes the form of a literature search.

Following this discussion, our research, by discussing the approach to intertextual processes in the final years of elementary school, in order to help teachers deal with this issue, contributes to the deepening of studies that link intertextuality and teaching. In this way, we explore the problem that consists in the scarcity of studies that guide teachers in the approach of such strategy of textual construction (intertextuality) to education, especially in the final years of elementary school. We project, therefore, the possibility that our exploration will result in a discussion that will contribute to the reduction of the negative effects that this problem can bring about.

As for the technical procedures that guide our data collection and analysis, this research can be characterized as bibliographical. This classification takes into account the teachings of Gil (2002). The author explains that researches framed in this technical procedure not only rely on bibliographic material to weave the theoretical discussion, but, going beyond, find in scientific/academic texts (theses, dissertations, books, articles, essays, etc.) a niche for collecting the data to be investigated, as well as procedural instructions that guide data analysis.

The delimited sample consists of five intertextual processes, which we studied in order to understand which of their characteristics are more likely to be worked on in each grade of the educational stage we are focusing on. They are: plagiarism, quotation, paraphrase, allusion, reference, parody, and pastiche. Each process is then analyzed according to the characteristics already studied by the authors to whom we refer. Next, these characteristics are addressed in examples, with the purpose of demonstrating how intertextual processes can be worked on in Elementary II.

The investigation of the characteristics of each intertextual process, in turn, is based, above all, on the analytical parameters arising from the research of Nobre (2014). The author, analyzing Cavalcante (2012), Genette (2010), Koch (2009), Piègay-Gros (2010) and Sant'Anna (2003), proposes that the investigations so far woven about the intertextual phenomenon have seen it from two parameters, which are subdivided, they are: functional parameter and constitutional parameter; the former subdivided in subversion, in playful or satirical regime and in capture, for convergence or divergence; the latter subdivided in compositional parameter (copresence and derivation), formal (reproduction, adaptation and mention) and referential (explicitness and implicitness).

The analysis is structured through a triad. Thus, we address, concomitantly, the characteristics of each selected intertextual process, analyze such processes and their characteristics based on examples of texts actually produced, and reflect on how is the approach to intertextuality in elementary school. This analysis, although it does not allow us to draw definitive steps for the approach of intertextuality in this period of education (that is, our study has no pretensions of being prescriptive), can contribute significantly by supporting teachers motivated to deal with this phenomenon in their classrooms. This work, therefore, has a theoretical character, given that we dialogue authors such as Cavalcante (2019), Marcuschi (2008), Marquesi, Pauliukonis, and Elias (2017), Santos and Teixeira (2017), Genette (2010), Piègay-Gros (2010), Cavalcante, Brito, and Zavam (2017), and Nobre (2014), proposing ways to strengthen the relationship between intertextuality and teaching.

In order to carry out the investigation we propose, our article is divided as follows. First, we situate the discussion on intertextuality in relation to text studies. In this way, we seek to deal with the association between text and teaching, pointing out the relevance of the phenomenon in the context of such discussion. Then, we move on to the study of intertextuality based on Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010). Thus, we approach the intertextual processes, focusing on plagiarism, citation, paraphrase, allusion, reference, and parody. Finally, preceding the conclusion, we develop our analysis by discussing the analytical parameters of Nobre (2014), describing the characteristics of each intertextual process and associating them to the work in Elementary II.

TEXT AND TEACHING

When reflecting on the conceptualization of text, Cavalcante (2019, p. 319) tells us that this "[...] is a negotiated construction in the use of language in a socio-historical contextualized situation". Therefore, we can understand that the text, to be effective as such, demands, on the part of the subjects, not only the mobilization of the linguistic system, which makes effective the use of language (whether verbal or not), but also "[...] involves [...] non-linguistic aspects, knowledge stored in memory that are constantly updated, and the defining sociocultural experiences of communication situations and the roles that subjects can assume" (MARQUESI; PAULIUKONIS; ELIAS, 2017, p. 7).

The mobilization pointed out in the previous paragraph, in turn, takes place in favor of interaction, the project of saying, the desire to communicate and be understood, and, for this, it is always contextualized, in this historical and social here and now. Text is, therefore, as Textual Linguistics researchers have argued, a communicative event: unique to each new mobilization of the linguistic system (when a speaker interprets or produces a new text); unique to each new situation of interaction; unique to each new social-historical here and now.

When we read a bus sign or the label of a product, when we watch a video on a social network, when we share a meme on an instant messaging platform, when we listen to the melody of a song on our cell phone, when we observe two people talking in a public place in sign language, or paintings, poems, images, songs, etc., we are immersed in texts, which we produce and/or interpret. Through them we act in the world, and, through them, the world affects us.

It is this reality that allows us to analyze that, in our society, texts occupy a primordial role, and it is in texts that human language can be truly observed, since it is in texts that human language develops. This justifies the prominent place that this category has gained in Textual Linguistics studies, as well as in other branches of Linguistics, such as Discourse Analysis (critical or French line), Functionalism and Sociolinguistics.

Marcuschi (2008), in this line of reasoning, argues that it is necessary to consider textual comprehension as social, rather than individual, work. The author, in such a way, argues:

Understanding is not only a linguistic or cognitive action. It is much more a form of insertion in the world and a way of acting on the world in relation to the other within a culture and a society. To get an idea of the difficulty of understanding well, just consider that in less than half of the cases people come out satisfactory in tests taken in class or in contests, which is repeated in many situations in everyday life. We often hear complaints such as: 'I didn't really mean that'; 'You don't understand me'; 'The author didn't say that,' and so on. However, it is worth asking what was being said or what the author meant. There are, therefore, bad and good comprehension, or better, bad and good comprehensions of the same text, the latter being cognitive activities that are laborious and delicate (MARCUSCHI, 2008, p. 229-230, emphasis added).

The scholar emphasizes the text, its understanding and, consequently, its construction as a social activity. It is, therefore, prudent to argue the importance of the insertion of the text in the school environment. Marcuschi (2008) points out that it is not about thinking this manifestation only from a normative point of view, preparing students for tests, exams, through exercises without contexts, copy and repetition, but, in fact, knowing the place of textual understanding in our society, give students the necessary framework for them to understand and be understood in human exchanges that occur in texts and mediated by texts.

The role played by textual manifestations in the context of human relations, as treated in the discussion we have outlined so far, contributes to explaining the prominent place it has also gained in the school environment. More than a category of analysis of Textual Linguistics, the text has been, in school, more or less rightly, the object of work of teachers, not only of Portuguese Language. This is how the contents of other subjects are dealt with in written, read, spoken, visualized, signaled or sensed texts. The text, from this perspective, allows us to put human knowledge in context, that is, it is the texts that make it possible to situate the knowledge in a historical and social moment, linked to human action and other knowledge, constituting a web of meanings that relates these to practices, hypotheses (scientific or not) and other texts.

Facing this discussion, reflecting on the role of the Portuguese Language teacher, Santos and Teixeira (2017, p. 426) point out that:

Although leading the student to expand the skills of reading and writing is not attributed solely to the Portuguese language teacher, without a doubt, it is he who can most systematically help develop the communicative/discursive competence of the learner - the main objective of language teaching. This competence can be understood as the ability to understand and produce texts considering certain effects of meaning and the situation of communicative/discursive interactions (TRAVAGLIA, 1996). To achieve this goal, in his pedagogical practice, he must abandon the phrasal perspective, which for many years dominated (and, in many schools, still dominates) the teaching of Portuguese, to favor a broader perspective: that of the text and its properties.

Given this reality, in recent decades, researchers and teachers have sought to make the discipline of Portuguese Language a space for the text5. Such a tendency aims to take advantage of all the potentialities that such manifestation carries and can contribute, in a very positive way, to the development of students' abilities of interpretation and action in the world (their daily family, school, etc.). In this context, scholars of Textual Linguistics (and other branches of Linguistic Science, such as Functionalism, Sociolinguistics, Discourse Analysis, already mentioned) have called attention to the fact that working text is not to direct the teaching to lose phrases or sentences that, although in context, are analyzed in isolation (SANTOS; TEIXEIRA, 2017). Thus, the study of the categories of textual constitution linked to teaching emerges.

We can cite as categories listed in Textual Linguistics for the study of textual constitution: "[...] text plan and textual sequences; [...]; text types; referential processes and coherence; intertextuality, its forms and functions; discursive topic, cohesion and coherence; multimodality; and genres [...]" (MARQUESI; PAULIUKONIS; ELIAS, 2017, p. 8). Recognizing the particular treatment given by this branch of Linguistics to these resources of text construction, Santos and Teixeira (2017) emphasize that it is from them that this area explains the textual functioning, being important that language classes, in order to develop the communicative and discursive competence of learners, take them as a basis for the development of classes. The authors teach that:

Thus, LT [Textual Linguistics] explains the rules of operation of text in use and provides a theoretical framework that accounts for the phenomena involving the production and reception of texts in the process of interaction of individuals through verbal language. It can, therefore, in Portuguese language classes, support activities with texts that, in fact, help students develop communicative/discursive competence (SANTOS; TEIXEIRA, 2017, p. 428-429).

In this work, aligned with this orientation, we emphasize intertextuality, which we will discuss in the next section. This category contributes so that we can investigate the role of the relations that texts establish among themselves for the construction of text meanings. These relations are beyond the discursive or enunciative spheres (although they presuppose them), in which dialogical, polyphonic or enunciatively heterogeneous relations are found. In this sense, contemporary studies on intertextuality have focused on understanding how relations between texts actually manifest themselves (mainly through intertextual processes). Thus, by putting texts in dialogue, as well as understanding how to flag these relationships, learners have in hand one more tool that helps them manage the argumentation of their texts and the texts they interpret.

INTERTEXTUALITY

Texts can (and usually do) dialogue with each other. Hence the notion of intertextuality. This concept was first coined by the semiotician Julia Kristeva (2005), in the context of Literary Semiotics studies. For this, the scholar is based on the Bakhtinian notion of dialogism. The Soviet scholar allows us to understand that all our language manifestations are not free of ideology, linking one to another in a network of infinite, dialogical relations. Kristeva (2005, p. 68), in turn, states that Bakhtin was the first to address, in literary theory, what we could call intertextuality, that is, the fact that every text is built as "[...] a mosaic of citations [...]" and the fact that every text is an "[...] absorption and transformation of another text [...]".

The notion of intertextuality, after presented by Kristeva (2005), is polished in the research of Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010), distancing itself from the initial notion that allowed confusion between this concept and the concept of dialogism. From these two scholars comes much of the developments that this category has gained, not only in Literature, the medium of studies in which it is born (and to which these researchers are linked), but also in Textual Linguistics, according to the research of Cavalcante (2012), Cavalcante and Brito (2011), Cavalcante, Brito, and Zavam (2017), Faria (2014), Koch, Bentes, and Cavalcante (2008), Nobre (2014), Souza-Santos (2020), and Souza-Santos and Nobre (2019).

Genette (2010) analyzes intertextuality as one of the manifestations of the phenomenon he called transtextuality. Textual transcendence, therefore, would account for every relationship of one text with another, in a "[...] manifest or secret manner [...]" (GENETTE, 2010, p. 11). The author divided this category into five others: intertextuality, paratextuality, metatextuality, hypertextuality and architextuality. Thus, intertextuality was able to explain the "[...] effective presence of a text in another [...]" (GENETTE, 2010, p. 12). Its manifestation would occur through citation, canonical form of intertextuality, through plagiarism, misappropriation of parts of another's text, and allusion, inferable intertextual relationship, not expressed directly.

Paratextuality was used to explain the relationship that a text has with its paratexts (footnotes, title, epigraphs, references, etc.). Metatextuality, in turn, explained the relationship between a text and the commentary that arises from it. This practice was directed, mainly, to literary critics' comments on works. Hypertextuality concerned the phenomenon existing when a text originates another, through transformation (parody, travesty and transposition) and imitation (pastiche, charge and forgery). Architextuality, on the other hand, explains the relationship that a text has with other texts of the same genre. This relationship tends to occur implicitly and is usually expressed when subjects recognize a text as belonging to a particular genre.

Two of these categories deserve our particular attention, as they have influenced later studies on the relations between texts. The first is what the author calls intertextuality and the intertextual processes it encompasses: citation, plagiarism and allusion. The second is hypertextuality, used to deal with the relations between texts in which one gives rise to another, in a movement of derivation.

The intertextuality thought by Genette (2010) was able to explain the relations between texts that are organized through copresences, i.e., those taken from a passage of source text placed in others (as occurs in citations, a canonical example of copresence). Hypertextuality, in turn, could occur through transformation or imitation, being organized through regimes (functions). In this way, the scholar listed the ludic, satiric and serious regimes. As transformation (of content) in the ludic regime, there would be parody. As a transformation (of content) in a satirical regime, we would have transvestment. As a transformation (of content) in a serious regime, we would have transposition. As for imitations, as an imitation (of style) in a ludic regime, we would have transposition. As imitation (of style) in a satirical regime, we would have the charge. And as imitation (of style) in a serious regime, we would have forgery.

Later, Piègay-Gros (2010) reorganizes these categories. She proposes, in such a way, to expand the term intertextuality, so that it could contemplate both categories named by Genette (2010) as intertextuality and hypertextuality. The author explains that intertextuality could occur, therefore, as copresence (what Genette [2010] had treated as intertextuality proper) and as derivation (treated by Genette [2010] as hypertextuality).

The copresence, for Piègay-Gros (2010), intertextual movement in which we have part of a text in another, could happen in an explicit way (the citation and the reference) and in an implicit way (the plagiarism and the allusion). The derivation, intertextual movement in which one or more texts originate another, was reduced by the scholar to parody, burlesque travesty (derivations by transformation) and pastiche (derivation by imitation of style). We will resume, explain and exemplify these categories in the analysis section.

Alongside Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010), we understand that it is necessary to approach intertextuality as a specific category of textual construction (not only of the literary text, as developed by these scholars, but of texts in general). From Genette (2010), in turn, we distance ourselves, because we do not take the position of considering intertextuality as one of the manifestations of the phenomenon treated by him as transtextuality. Thus, we understand, like Piègay-Gros (2010), that intertextuality can be analyzed as the very category to account for the relations between texts. Moreover, we corroborate the position in assuming such category as didactically divided into copresence relations and derivation relations. This position will be taken again later on, when we reflect on intertextual relations.

Based on Piègay-Gros (2010), in this study, in our analysis section, we deal with plagiarism - understanding it, according to Souza-Santos (2020), not only as occurring by copresence, but also by derivation -, allusion, reference and citation. Moreover, we also deal with parody, contemplating both what the author treated as parody itself and the burlesque travesty, since it is sometimes impossible to distinguish ludic and satirical transformations, given the proximity of these two categories (SOUZA-SANTOS, 2020).

We also include pastiche in our discussion. Moreover, we added paraphrase, a form of putting texts in dialogue recurrent in the educational and academic environment, occurring both by copresence and derivation, but that was not addressed by the researcher. The treatment of this intertextual process occurs in Cavalcante (2012), Cavalcante, Faria and Carvalho (2017) and Souza-Santos (2020).

ON INTERTEXTUAL PROCESSES AND THE WORK OF INTERTEXTUALITY IN THE FINAL YEARS OF ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Nobre (2014) investigates that intertextual relations, so far studied by researchers dedicated to the topic, were analyzed from, briefly, two parameters (as we have already advanced in previous sections): a functional parameter and a constitutional parameter. To reach this conclusion, the author took as a basis both the issues addressed by Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010) and the studies of Cavalcante (2012), Koch (2009) and Sant'Anna (2003). This systematization makes it possible to evaluate as intertextual processes the citation, the reference, the allusion, the plagiarism, the paraphrase, the parody, the burlesque travesty and the pastiche. We activate the study of this author, in this article, because we consider that it contributes to our understanding of which characteristics these intertextual processes have as more prototypical, whether related to the functions they occupy in textual construction, or related to the constitution they take when they gain body.

For Nobre (2014), based on Genette, it is possible to analyze a constitutional parameter, divided into imitation and transformation. Besides this, we would also have a compositional parameter, divided into intertextuality and hypertextuality, by Genette, and the processes of copresence and derivation, by Piègay-Gros. Under a functional parameter, it is possible to investigate the serious and playful/satirical regimes, by Genette, the paraphrastic and parodistic axes, by Sant'Anna, and the processes of capture and subversion, by Koch. Based on Koch and Piègay-Gros, we can think of a referential parameter, organized in explicitness and implicitness.

The researcher, emphasizing the fact that such categories are not classificatory, but rather of orientation to the analysis of intertextual processes, subordinates the compositional and referential parameters to the constitutional parameter. Nobre (2014) adds the formal parameter, subdividing it into reproduction, adaptation, and mention. He excludes imitation and transformation in the constitutional parameter (this parameter is now divided into broad intertextuality and strict intertextuality) and, under the functional parameter, he also excludes paraphrastic and parodistic axes. The criteria for the additions and exclusions made, however, are not explained by the researcher.

We have, from this reorganization, the functional parameter on one side and the constitutional parameter, subdivided, on the other. Thus, it is expressed: the functional parameter can be seen as by capture, for convergence or for divergence, and as by subversion, in a ludic regime or in a satiric regime; from the viewpoint of the constitutional parameter, we have broad intertextuality and strict intertextuality. Strict intertextuality includes the compositional parameter, which includes copresence and derivation, the formal parameter, which includes reproduction, adaptation, and mention, as well as the referential parameter, which is expressed through explicitness or through implicitness.

We propose that, to understand how these categories listed by Nobre (2014) are useful to the study of intertextual processes, it is necessary to link them to examples, which, in addition to allowing to demonstrate, from these parameters, the intertextual processes being configured, also make it possible to understand the particularities of each intertextual process. In this sense, next, we discuss the intertextual processes by copresence and by derivation, like Piègay-Gros (2010), giving special attention to plagiarism, citation, paraphrase, allusion, reference, parody and pastiche.

We adopted this sequence because we evaluate, as we pointed out at the beginning of this section, that it allows us to start from the intertextual relationship with which we first have contact throughout our training as learners, plagiarism (the very ignorance that students have of how to put texts in dialogue can lead to the production of texts with copy or text-copy), passing through more concrete intertextual processes, the relations by copresence, and, therefore, easier to visualize, such as the quotation and the paraphrase, arriving at the allusion and the reference, which, although abstract, because they take place between specific texts, can be located more precisely. Next, we analyze parody, an intertextual process carried out mostly by derivation, which, by producing criticism, humor, satire, from a complex movement in the constitution of the resulting text, may demand from the students, greater skills, for its production and interpretation. Finally, we investigated the pastiche, derivation that occurs not between specific texts, but from the imitation of several texts that make up the style of an author, being, in such a way, more abstract, demanding from the students, greater knowledge of the world and of how the intertextual processes are organized.

Plagiarism

The following example consists of excerpts from an essay of the National High School Exam (ENEM) (Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio, shortened as Enem is a non-mandatory, standardized Brazilian national exam, which evaluates high school students in Brazil.), produced in 2016, in which it is possible to verify, from the comparison with the source texts, the realization of plagiarism. The case has gained wide repercussion, since it occurred in an essay evaluated with a score of 1000 by the exam (maximum score that a participant can obtain in such an evaluation). Besides drawing our attention because it occurred in a text that was awarded top marks by Enem (which causes strangeness because it is structured through the misappropriation of another's text, with no reference to its authorship) and, moreover, it allows us to discuss the use of previously elaborated formulas for the production of essays in college entrance exams and competitions, such occurrence also allows us to reflect on plagiarism (or copy, as we can also call it), as a recurrent intertextual relationship in our schools. Let's do the analysis.

Source: https://abrilguiadoestudante.files.wordpress.com/2017/05/plagio-site.png. Accessed 8 Dec. 2019.

Figure 1 Enem 1000 grade essay with plagiarism

Text in English:

Copied essays vs. original essays

The text below, in black, is the one that scored a thousand on Enem 2016 and copied two essays written in 2014 and 2015. On the sides, in color, are the plagiarized passages:

Brás Cubas, the deceased-author of Machado de Assis, says in his "Memórias Póstumas" that he had no children and did not transmit to any creature the legacy of our misery. Perhaps today he would realize his decision was right: the attitude of many Brazilians towards religious intolerance is one of the most perverse faces of a developing society." -> Brás Cubas, the deceased author of Machado de Assis, says in his "Memórias Póstumas" that he had no children and did not transmit to any creature the legacy of our misery. Perhaps today he would realize his decision was right: the posture of businessmen and advertisers regarding advertising for children is one of the most perverse faces of a society that despises ethical values in the name of stimulating consumption (Original text: Professor Rafael Cunha)

"There is no doubt that the constitutional issue and its application are among the causes of the problem. According to Aristotle, politics must be used so that, through justice, balance is achieved in society. In a similar way, it is possible to realize that, in Brazil, religious persecution breaks this harmony; although the principle of isonomy is foreseen in the Constitution (...)". -> There is no doubt that the constitutional issue and its application are among the causes of the problem. According to Aristotle, politics must be used in such a way that, through justice, balance is achieved in society. Similarly, it is possible to realize that, in Brazil, aggression against women breaks this harmony, since, although the Maria da Penha Law has been a great progress in relation to the protection of women, there are loopholes that allow crimes to occur, such as the many victims who do not denounce themselves because they are intimidated. (Original text: Student Raphael de Souza)

"According to Durkheim, social fact is the collective way of acting and thinking. By following this line of thought, it is observed that the preparation of religious prejudice fits the sociologist's theory, since if a child lives in a family with this behavior, he tends to adopt it also because of the group experience (...)". -> According to Durkheim, a social fact is the collective way of acting and thinking, endowed with exteriority, generality and coercivity. According to this line of thought, gender prejudice can be fitted into the sociologist's theory, since if a child lives in a family with this behavior, he tends to adopt it also because of the group experience (...) (Original text: Student Raphael de Souza)

"(...) Thus, we will be able to transform Brazil into a socially developed country, and create a legacy that Brás Cubas could be proud of." -> Thus, we can, little by little, open the curtains of the capitalist world for our children, so that they can become really conscious consumers in the future and a legacy that Brás Cubas could be proud of. (Original text: Professor Raphael Cunha)

Plagiarism, as Souza-Santos (2020), Souza-Santos, Brito and Cavalcante (2019) and Souza-Santos and Cavalcante (2019) discuss, corresponds to the act of appropriating parts of another text or the text as a whole, with or without modifications of parts, in favor of the text that proposes its own, without reference to the authorship of the source text. Such an arrangement is generally assessed socially as illicit and discredited. This practice can occur either by copresence (a piece of text inserted into another text) or by derivation (a text that gives rise to another text). In the example in question, we verified the predominance of reproductions of two texts, which add to the additions of the student participant of Enem, in favor of the text that he proposed as his responsibility, that is, his authorship. Such model of plagiarism, therefore, can be considered (constitutionally and functionally) one of the most common to be analyzed circulating in society, being a prototypical example of misappropriation.

Thus, from the organization of the parameters underlying intertextual relations worked by Nobre (2014), seen from the constitutional point of view, such an occurrence is a strict intertextuality, which takes place between specific texts, being, in terms of composition, a copresence, in formal terms, we verify reproduction and, in referential terms, an implicit intertextuality (for being absent the authorship marking of the source text). Analyzed from the point of view of the functional parameter, it is possible to evaluate a capture for convergence, that is, the ideas of the source texts are seized in the intention of the arguments that the producer of the text-plagiarism produced, serving, therefore, as reinforcement to the arguments he supports.

We consider it valid to call attention to the reality that many students, especially at the beginning of the schooling process, for not knowing the intertextual normalization (how to put texts in dialogue, citing, paraphrasing, alluding, marking the text-other with typographic marks and/or reference to authorship), recurrently produce texts fruit of copying. Thus, as an example, we can cite the school papers that students prepare by copying and pasting information from the Internet. Here, plagiarism should be treated as a pedagogical issue, considering, from such observation, that students know that putting texts in dialogue is important to build their texts (although they do not know how), being able to perform the necessary movements to accomplish such practice, as the movements of putting texts in relation through co-presence or derivation, reproducing, adapting or mentioning the source texts.

Plagiarism, therefore, can be the first intertextual relationship to be worked on in the classroom. Its approach can begin as early as the 6th grade, starting with the students' textual productions that constitute copies, or that contain parts of copies. Through such work, it is possible to address issues related to the illicit nature of the practice, how it is socially evaluated, stimulating debates on the organization of genres, on ethics, and on the circulation of information. In addition, it is extremely relevant to give students tools to reformulate their texts, producing, especially, citations and paraphrases. At this moment, it is important to lead students to recognize the productivity of these intertextual processes against the discredit of plagiarism.

The citation

The citation, according to Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010), is the most common intertextual process to be found in textual manifestations that circulate in society. It consists in taking an excerpt from a given source text, that is, it is a copresence, literally reproducing the quoted excerpt, referring its authorship to the proper author. Piègay-Gros (2010) points out that the quotation commonly produces an ornamentation effect, i.e., it is mobilized to demonstrate a certain erudition of the subject that triggers it or an effect of recourse to authority, being used by the subject with the purpose of supporting its positions in authors considered prestigious in the subject in question. Thus, this intertextual resource is recurrent in texts from the scientific/academic, journalistic, and even school discourse domains. The following example, on the other hand, presents the quotation circulating in a portrayal of everyday interaction in a classroom. Let's do the analysis.

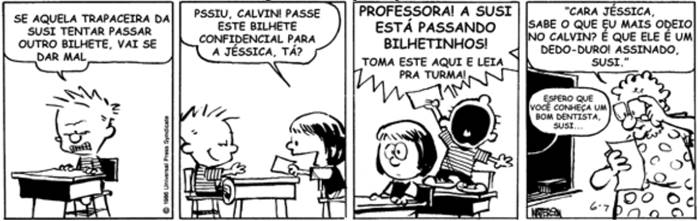

Source: https://nova-escola-producao.s3.amazonaws.com/zzmyv6v5smkctnryhfsgq9qaw9uyvhcqfvfhmtepayzv3x8crez8anrdja3b/calvin-97.gif. Accessed 8 Dec. 2019.

Figure 2 Example of quotation

Text in English:

First Square: If that scammer Susi tries to pass another note, she's going to get it wrong.

Second Square: Pssiu, Calvin! Pass this confidential note to Jessica, will you?

Square Three: Teacher! Susi is passing out notes! Take this one and read it to the class!

Fourth Square: "Dear Jessica, do you know what I hate most about Calvin? It's that he's a cheapskate! Signed, Susi”

I hope you know a good dentist, Susi.

In the text, belonging to the comic strip genre, a situation is portrayed in which the character Susi asks her classmate, Calvin, to pass on a note to Jessica. Previously, Calvin had already planned how to act (in a kind of revenge plan) if Susi made such a request. After the request, he takes the note and shouts to the teacher, telling her that he had passed the note on to his classmate and demanding that the teacher read the content of the text to the whole class. The teacher reads the message written by the girl, which, from then on, appears in the comic strip as a quotation: being a reproduction of the note, typographically demarcated with quotation marks, with reference to Susi's authorship. The message justifies to Jessica why her colleague (the author of the note) hates Calvin: the fact that he is a "stoolie. At the end of the text, Calvin threatens Susi, stating that he hopes she has a good dentist.

Besides portraying the quotation being manifested in an everyday situation, common to children, the previous example allows us to analyze how such an intertextual process is recurrently used by artists (especially writers) in the production of their texts. This use, sometimes, is not for ornamentation or to appeal to authority, but to express to the readers or listeners of their texts thoughts or speeches of characters, making, in the body of the work, distances or approximations between the posture of the narrator(s) and the other characters.

Whether in the construction of more scientific texts, as in school works, or in the construction of more literary texts, as in songs, short stories, comic strips or novels, it is extremely relevant to work on citation in the classroom. As we have seen when dealing with plagiarism, this can be inserted in the 6th grade of elementary school as an alternative to copying ipsis litteris, but it can also be worked on throughout the other grades that follow. In this way, students should be instructed to reproduce the voice of others, indicating the proper authorship. In this process, it is possible to work on the fact that such mobilization is useful both to trigger text-other and make it valid as a valid argument to their ideas, what Nobre (2014) treats, from the perspective of the functional parameter, as capture for convergence or to argue against the quoted passage, what this author points out as capture for divergence.

Paraphrase

Paraphrasing is an intertextual process that can appear both as copresence (this is the case of paraphrasing in articles and reports, for example), as presented by Cavalcante, Faria, and Carvalho (2017), and as derivation (this is the case of paraphrasing in summaries and in specific cases of reviews, for example), as argued by Cavalcante (2012). Here, we treat such an intertextual process as in its condition of copresence. In this configuration of realization, the paraphrase is too close to the citation, changing only the fact that it adds reproductions with adaptations, not being only reproduction as it is. In addition, it occurs making explicit the source of the intertext and, generally, capturing the argumentation in a movement of convergence.

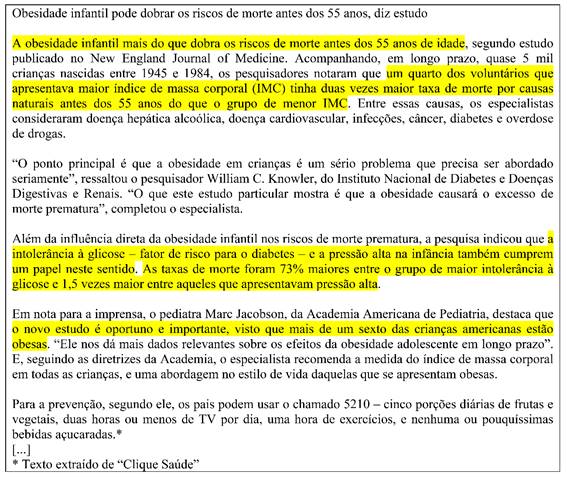

The following text brings paraphrases in its composition, which are marked by yellow stripes. Let's see.

Source: https://escolakids.uol.com.br/portugues/texto-de-divulgacao-cientifica.htm. Accessed on: January 5, 2020.

Figure 3 Example of a paraphrase

Text in English:

Childhood obesity may double death risks before age 55, study says

Childhood obesity more than doubles the risk of death before age 55, according to a study

published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Accompanying, in the long term,

almost S mi

children born between 1945 and 1984, the researchers noted that a quarter of the volunteers who

volunteers with the highest body mass index (BMI) had twice the rate of death from natural causes

causes before age 55 than the group with the lowest BMI. Among these causes, the experts

alcoholic liver disease, cardiovascular disease, infections, cancer, diabetes, and drug overdose.

of drugs.

"The bottom line is that obesity in children is a serious problem that needs to be addressed

seriously addressed," said researcher William C. Knowler of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Digestive and Kidney Diseases. "What this particular study shows is that obesity will cause excess

premature death," added the expert.

In addition to the direct influence of childhood obesity on the risks of premature death, the research indicated that the

glucose intolerance - a risk factor for diabetes - and high blood pressure in childhood also play a

a role in this regard. Death rates were 73 percent higher among the more glucose intolerant

glucose intolerance group and 1.5 times higher among those with high blood pressure.

In a press release, pediatrician Marc Jacobson, of the American Academy of Pediatrics, points out that

the new study is timely and important, since more than one sixth of American children are obese.

obese. "It gives us more relevant data about the long-term effects of adolescent obesity."

And, following Academy guidelines, the expert recommends measuring body mass index

in all children, and a lifestyle approach in those who are obese.

For prevention, according to him, parents can use the so-called 5210 - five daily servings of fruits and

vegetables, two hours or less of TV a day, one hour of exercise, and no or very few sugary drinks.

sugary drinks. *

* Text extracted from "Clique Health"

The example in question provides information about childhood obesity, data from studies on how this condition affects children and how it can be prevented. It is, therefore, a text of scientific dissemination. It draws our attention to the fact that we can analyze, in its constitution, paraphrases (also commonly called indirect quotations) that, in addition to the quotes, trigger results of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, as well as statements from researchers, which support the discussion outlined in the disclosure text. This reality allows us to investigate some characteristics of paraphrasing that are relevant to be worked on in elementary school.

We saw that copying (plagiarism) can be one of the first forms of relating different types of texts, which we can work on in Elementary School. The students, already aware of the construction of texts (after all, these surround them since the first seconds after birth) know that putting texts in dialogue is a possible and often necessary reality. Copying, however, as an illicit and non-productive practice, should be avoided. Faced with this condition, the paraphrase (like the citation, as we have already discussed) appears as a possibility of triggering other texts, especially those that allow supporting and strengthening arguments (capture for convergence), without the need to mobilize plagiarism.

Another characteristic of paraphrase is the fact that it is an intertextual process that allows the activation of texts (positions, opinions, arguments) of authorities. Thus, this intertextual relationship can be found in texts from discursive domains linked mainly to scientific/academic, school and journalistic environments. It is also worth considering that, although close (especially in functional terms, since both relations are commonly captured for convergence or, not commonly, for divergence), the quotation and the paraphrase differ, especially in terms of the constitution they assume when manifesting themselves. If, in the quotation, the reproduction of a passage of another text is a necessary condition for its existence, in the paraphrase, as mentioned above, reproductions and adaptations are added, marked or not typographically, not being, therefore, a reproduction ipsis litteris, being present the due reference to another's authorship.

We believe that, in view of these characteristics, it is possible to start working with paraphrasing in the 6th grade of elementary school. First, this intertextual process appears as an alternative to copying. Its approach, as well as that of citation, can advance throughout the entire Elementary School, dealing with how it allows the use of authority and the reorganization of information, speeches and scientific data from other texts used by characters or authors when constructing their texts. It is worthwhile to advance, throughout the 7th, 8th, and especially the 9th grades, in the discussion of how paraphrasing helps in the construction of scientific/academic texts, in which it is often necessary to support arguments (as in the example in Figure 3). This practice can also be linked to the preparation of summaries, reviews, and other genres in which paraphrasing can occur by derivation.

Allusion

The allusion is an intertextual process that, as we dealt with when investigating the citation and paraphrase, also occurs by copresence, being, in such a way, the triggering of text excerpt from another text in the construction of the text now manifested. Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010) agree that this way of putting texts in relation is more implicit, since it indirectly refers the reader or listener to the triggered text, without typographical markings or conventional demarcation of reference to authorship. Brito, Falcão, and Souza-Santos (2017) explain that this indirect remission occurs through clues, which usually allow the recognition of this intertextual process by the subjects that have access to it. In constitutional terms, therefore, allusion is a copresence that manifests itself through the mention (usually, the mention of terms or phrases from other texts) not typographically marked of the text placed in dialogue. Let's analyze the following example.

Source: https://i2.wp.com/www.umsabadoqualquer.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/brinca-2.png. Accessed 8 Dec. 2019.

Figure 4 Example of allusion

Text in English:

You can't play with God (literal translation, meaning both God is not to be trifled with, and in the comic, one can’t actually play with God)

This example is part of the set of comic strips Um sábado qualquer sábado (Any Saturday), which usually reflectively address issues related to religions. In order to provoke such reflection, the texts carry, mainly, satire, humor and criticism (direct or not) to religious principles (regardless of religion) and the relations of human beings with their beliefs. In the text in question, there is the character God on a seesaw, sad for being lonely. Moreover, the strip says "You can't play with God!", which is a clear allusion to the popular saying reproduced by subjects of Christian belief as a warning when "playing" with God (taking attitudes contrary to the Christian creed). Note that, in fact, the allusion here is used to subvert the most common sense used when the phrase is used (making, in this way, a literal interpretation of the statement). Instead of sounding like a warning, the strip shows that God (with a childish aspect), for not having anyone to play with, would be sad.

This discussion helps us to reflect on some of the most common characteristics of allusion. This intertextual process, as we can see in the example, manifests itself, generally, without typographical markings or explicit references to the authorship of the text in question. Thus, in the text studied, we note that there are no quotation marks, italics or bold to mark the alluded passage, nor are there references to the authorship of the intertext (which, in this case, would be generic, because it is a popular saying).

How, then, would the recovery of such an intertextual process take place? It is worth considering, first, that there will not always be its recognition (this condition also applies to the other intertextual processes), and there are subjects who, when interpreting a text with allusion, will not realize the intertextual relationship and will make other interpretations of the information present. However, the allusion is constituted by leaving clues so that it can be recovered; in the case analyzed, the clues are the very context in which the statement is placed (a comic strip of critical reflections on religion, which carries the image of the character God playing on a seesaw), as well as the fact that it is a known phrase in the community where it is propagated, i.e., the Brazilian society, of religious majority known to be Christian, which would facilitate its recovery.

The allusion, therefore, allows the placement of texts in dialogue without the need to clearly delimit such placement. This reality makes possible the construction of veiled criticism, either to the text alluded to, or as a resource for the realization of criticism of another text or situation. As we can see, because it is indirect, this intertextual process demands specific world knowledge from those who interpret it, which contributes to the recovery of the triggered intertext, as well as to the understanding of what the meaning of the triggering of that intertext would be when placed in the text in question. These conditions lead the allusion to be very common in texts of the literary-musical domain, such as in songs, poems, short stories, novels, comic strips, cartoons, etc.

We note that, although it occurs between specific texts, being a co-presence, the allusion requires, both in its elaboration and in its interpretation, greater skills from students, both in terms of their own understanding of intertextual processes, and in terms of knowledge of various texts, which can be triggered in the form of allusion. Thus, we believe that this intertextual process can be worked on, mainly, in the 7th and 8th grades of elementary school. This is because working on it in the 6th grade could be too early, since in this grade the notion of intertextual processes is being introduced, starting with copying, moving on to citation and paraphrase. In 7th grade, students would already be able to recognize intertextual relations by copresence, being able to assimilate allusion to citation and paraphrase, as well as to recognize specific allusions that are related to their realities. In 8th grade, on the other hand, it is expected that the advance in readings and world experiences will allow students to recognize and produce a greater number of allusions, not only in literary or musical texts, but also for the construction of more argumentative texts (i.e., that aim at argumentation).

The reference

The reference, as well as the allusion, consists in a remission to another text that, although not marked typographically, is explicit because it is given through the placement, in the intertext, of names of characters, contexts, titles or names of authors of specific works. Thus, as Souza-Santos and Nobre (2019) point out, allusion and reference carry proximities that sometimes allow us to view these two intertextual processes as one. The reference is, thus, an intertextuality by copresence, for being an excerpt from another specific text. Besides the mention, it formally has the characteristic of being constituted by reproduction. This intertextual process, compared to the allusion, is more explicit, because it allows a more precise recognition of the intertext used in the construction of the respective process. For better understanding, let's discuss an example.

Source: https://www.letras.mus.br/sitio-do-picapau-amarelo/1432329/. Accessed on: January 5, 2020.

Figure 5 Example of reference

Text in English:

Sitio do Pica-Pau Amarelo (Yellow Woodpecker Farm) - Gilberto Gil

Banana marmalade, guava bananade

Quince guava

Yellow Woodpecker Farm

Yellow Woodpecker Farm

Cloth dolls are people, corn cobs are people

The rising sun is so beautiful

Yellow Woodpecker Farm

Yellow Woodpecker Farm

Rivers of silver, pirate

Sidereal flight in the woods, a parallel universe

Yellow Woodpecker Farm

Yellow Woodpecker Farm

In the land of fantasy

In a state of euphoria

Jumping jack city

Yellow Woodpecker Farm

Above, we could read a song, composed and performed by Gilberto Gil, which was played in the openings of the cartoon Sítio do Picapau Amarelo (Yellow Woodpecker Farm), produced and reproduced by the Brazilian Globo Television Network, based on the work of the same name by Monteiro Lobato. In the song, we can analyze the reference, as an intertextual process, being used to link the text of the song with the text of the cartoon and Monteiro Lobato's work. Thus, the passages highlighted in bold, such as the expressions "Sítio do Pica-Pau Amarelo", "Boneca de pano é gente" and "Sabugo de milho é gente" (Yellow Woodpecker Farm, A rag doll is a person, Corn cobs are people) refer, respectively, to the title of the work, to one of its characters (the cloth doll named Emília) and to the personified corn cob (named Visconde de Sabugosa - Viscount of Sabugosa). In addition to such passages, the song triggers recurring spaces in fantastic literature (and common to the world of Sítio do Picapau Amarelo), a genre to which the work of the famous Brazilian writer belongs, which can also be seen as an intertextual element, being an example of intertextuality lato sensu (KOCH; BENTES; CAVALCANTE, 2008), whose purpose is to bring the musical text closer to its literary and television version.

We can understand, based on the example, that the reference, as an intertextual process, is built through the activation of characters and contexts of another text, which allow a more precise recovery of the source of the intertext, even if such source is not exposed, or the intertext precisely delimited. This reality makes this intertextual process more common in texts from the literary-musical domain, as well as the allusion. We analyze that these conditions contribute to the fact that this intertextual relation can, along with allusion, be worked on in 7th and 8th grade of elementary school. Such work allows us to demonstrate how intertextual processes that are similar, but differentiated by the degree of explicitness, end up behaving in different ways in the texts in which they are placed.

Parody

Parody, unlike quotation, allusion and reference, is an intertextual process that most commonly occurs not by copresence, but through derivation by transformation (in other terms, it is a text that arises based on the transformation of another). It should be noted, however, that, as we pointed out in relation to plagiarism and paraphrase, it is possible to find examples of parody that occur by copresence, these cases are called detournement (CAVALCANTE, 2012). In formal terms, parody usually adds reproductions and adaptations.

In addition, the parodistic text usually makes explicit, even if more indirectly, the reference of the text from which it departs. This happens both so that the subjects recover the source and, in this way, can achieve the meanings projected by the author of the parody, and also so that the parodied text is not seen as a copy. We list as common functions to this intertextual process the playfulness (according to Genette [2010, p. 39], playfulness is a construction that aims at "[...] entertainment or [a]pleasurable exercise"), humor (to provoke laughter through constructions not necessarily satirical), satire (to provoke laughter through ridiculing constructions) and criticism (political, social, personal, etc.). For better understanding, let's study an example.

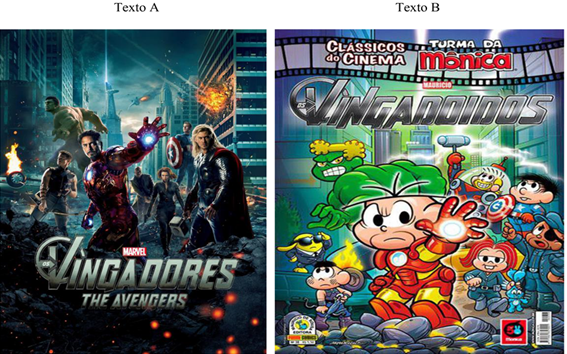

Source: Avengers, available at: https://image.tmdb.org/t/p/original/enkqrpdhnvheno66j4uj9szruts.jpg, and Turma da Mônica (Monica and Friends), available at: https://cdn.ome.lt/t-lizhmun-_0qlk714z8iwf5g7k=/837x0/smart/uploads/conteudo/fotos/vingadores-monica.jpg. Accessed 8 Dec. 2019.

Figure 6 Example of parody

Text in English:

Left (Text A): Marvel Avengers

Right (Text B): Movie Classics Monica and Friends Avencrazy

In the example analyzed, it is possible to note precisely that the text of Turma da Mônica (Monica and Friends) (text B) is configured as a parody of the poster advertising the movie Avengers (text A). Such understanding is possible because the images of text B are arranged in the same structure (arrangement of characters and scenery) of text A, configuring a reproduction. Moreover, it also reproduces the main characteristics of the characters present in the Avengers text, such as the color of Iron Man's clothes, the color of the Hulk character, the figure of Thor's hammer and Captain America's shield. The style of construction of the characters, in turn, was adapted, featuring traces typical of the style of the drawings present in the Turma da Mônica ((Monica and Friends) comic books. In addition, the title of the movie was also adapted in the B text, so Avengers became Avenged. All this complex constitution is mobilized so that parody manifests itself and allows the construction of the effects already listed (in the text in question, humor predominates).

From these considerations, we can analyze that understanding how to interpret and produce parodies can stimulate both the critical interpretation of texts by students and can be a fun activity, given the playfulness and humor, attracting their interests. Parody, based on the characteristics discussed in this section, is common in texts of the literary-musical domain and usually appears in children's songs, often known by the students.

Working with this intertextual process requires that students first have an understanding of what intertextuality is and how it manifests itself through intertextual processes. Parody, as Faria (2014) points out, can be constituted through a set of copresences, so before working on it, it is necessary to address intertextual processes, such as plagiarism, citation, paraphrase, allusion, and reference. In this way, we evaluate that the parodistic text can be inserted in the 8th grade, approaching texts mainly linked to the students' realities, and have its work continued in the 9th grade of elementary school, discussing its constitution and the functions it carries (focusing on the argumentative construction that humor and satire can generate, commonly foundations of criticism). An interesting activity related to this intertextual process is to ask students to produce parodies with a critical function based on songs or other artistic works they are interested in.

Pastiche

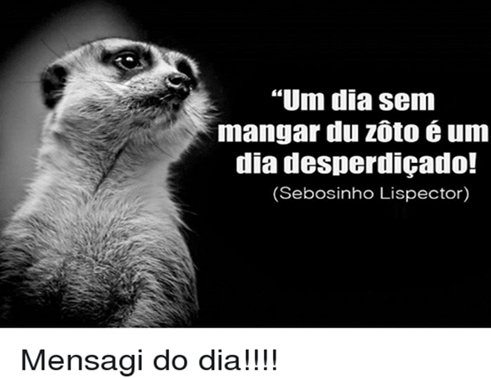

Pastiche is the production of a text that is based not on a specific textual manifestation, but on multiple texts by an author, with the purpose of imitating his style. We have, therefore, a derivation by imitation. This differs from parody in that, while in parody one text gave rise to another, here, given the difficulty of abstracting an authorial style from a single text, it is a set of texts that gives rise to another. This intertextual process is also more common in the literary-musical field and its predominant functions are playfulness, humor, satire and criticism. For a better understanding, let's analyze the following example.

Source: https://pics.me.me/um-dia-sem-mangar-du-zoto-%c3%a9-um-dia-desperdicado-1866982.png. Accessed 8 Dec. 2019.

Figure 7 Example of pastiche

Text in English:

"A day without mocking others is a wasted day! (Greasy Lispector)

Message of the day!!!!

The text analyzed above is a meme published by Suricate Greasy page. Initially, it can be noticed, by the reference placed as corresponding to the authorship of the sentence, that the speaker of the text aimed to imitate the style of Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector. Moreover, the "quoted" sentence carries some characteristics commonly present in the text of the modernist author, such as the reflective character regarding everyday situations and the more melancholic and intimate content. This example in question shows us how such an intertextual relationship did not occur between the resulting text and another specific text by Clarice Lispector. In fact, the analyzed meme was based on the author's style when it was created. The intertextual relationship here was between the derived text and the multiple texts, not precisely locatable, from which Lispector's style was abstracted.

Evaluating the characteristics of this intertextual process, we conclude that it can be worked on mainly in the 9th grade of elementary school. In this grade, students will already be able to understand intertextual relations not only by copresence, but also by derivation. Thus, they will have less difficulty interpreting and producing examples of pastiche. In addition, the fact that students in this grade carry greater reading and world knowledge contributes to their ability to recognize authors' styles, as well as to imitate them.

In this sense, teachers can, as an activity, instigate students to imitate styles of authors (whether writers, painters, photographers, etc.) they know and are interested in (which stimulates readings of multiple texts and the mobilization of diverse intertextual processes in the search for their interpretations and for the sake of the intertextual productions then elaborated).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

We were able to discuss, throughout this work, how the intertextual processes (specifically plagiarism, quotation, paraphrase, allusion, reference, parody and pastiche) can constitute themselves and what functions they can carry, seeking to tie the predominant characteristics in each of them to the work of intertextuality in the final years of elementary school. We start from the understanding, already discussed in Cavalcante, Brito, and Zavam (2017), that working with the relations between texts, educating students to recognize the intertextual processes and use them, can positively expand the skills focused on interpretation and textual production, so important not only throughout schooling, but throughout life.

Tracing an investigation that could be able to support what we have proposed, we understand that the approach between text studies and teaching is too relevant and necessary. It is through the text that we express and feel the language, from the initial phase of life to its end. Thus, besides being related to language development, text is also directly inserted in everyday human exchanges, whether in a news article or in a conversation (or in other manifestations). Texts allow us to defend ideas, to which we link arguments, or even express sensations and feelings, to which we can link melodies, rhythms and body expressions.

Still around the discussion resumed in the previous paragraph, we could also understand that we cannot work on such an important manifestation (the text) reducing it to the study of loose phrases and decontextualized sentences or considering it as an agglomeration of sentences. Thus, Textual Linguistics has listed categories that make it possible to broaden textual analysis and are able to stimulate a dynamic teaching, socio-historically situated and directed towards argumentation. Among these categories, which include referencing, topical organization, multimodality, coherence, cohesion, textual sequences and textual genres, there is intertextuality, a specific theme on which we focus in this research.

To discuss intertextuality, we adopted Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010). Such choice was not because we were unaware of other scholars linked to the subject or because we deny the recent and important advances linked to the study of such category by text linguists, we resorted to these two authors for having been pioneers in the investigation of the manifestation of intertextuality as an intertextual process. Thus, the studies by Genette (2010) and Piègay-Gros (2010) are fundamental for us to analyze how each process is organized, its main characteristics, and how they enter the texts.

Next, we begin our analysis by addressing the parameters from which the intertextual processes have been studied by researchers. These parameters help us think about how each process manifests itself recurrently, thus expressing characteristics. With this analytical movement, our purpose was to link these characteristics to the approach of intertextuality in elementary school. In this way, we turned to each selected process, discussed, based on theoretical references, its particularities and assimilated them to the Elementary II grades, analyzing examples that allow us to visualize this assimilation.

We emphasize that the indications made throughout the analysis should not be interpreted in a normative or prescriptive way. In this sense, they serve only to guide teachers (as suggestions) as to how to work with these processes in Elementary II. Teachers can (and should) adapt them to the realities of the classrooms with which they have contact, adding or deleting intertextual processes of the years considered. The texts used for this approach should, preferably, be inserted in the students' realities, with themes related to their daily lives. Furthermore, we warn that the work with intertextuality should not end in Elementary School, this stage of education being only the beginning of the work with this category.

The promoted research highlights the fact that the production and interpretation of texts can be stimulated when working with intertextuality. Furthermore, intertextuality highlights the social character of language and texts, evidencing the construction of the subjects as members of specific cultures, of which the texts are part and to the construction of which they contribute. This, it should be noted, plays a fundamental role in the refinements and recognitions of the relations between texts, considering that such refinements and recognitions demand cultural knowledge to be effective. This reality reflects the process by which we are constituted as members of a culture, internalizing language and appropriating it, giving, each in his or her own way, authorial marks to the texts.

From our research, other investigations may arise and/or be based on it. Thus, we consider that intertextual processes other than the ones selected here can be included in future works that perform similar analysis, seeking to bring intertextuality and teaching closer together. In addition, it is possible to expand the reflections outlined, broadening the investigation on the intertextual processes on which we focus, developing work centered on specific processes. Discussions that address how learners can mobilize intertextual relations for the argumentative construction of texts, as we see in Koch and Elias (2016), are not only pertinent, but also important and necessary.

REFERENCES

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Estética da criação verbal. Tradução de Maria Ermantina Galvão G. Pereira. 2. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1997. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular: educação é a base. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Educação, 2018. [ Links ]

BRITO, Mariza Angélica Paiva; FALCÃO, Maria Dayanne Sampaio; SOUZA-SANTOS, José Elderson de. Apelo a um exterior: as alusões como estratégias argumentativas. Revista de Letras, Araraquara, v. 2, n. 36, p. 23-35, 2017. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTE, Mônica Magalhães. Os sentidos do texto. São Paulo: Contexto, 2012. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTE, Mônica Magalhães. Por uma análise argumentativa na Linguística Textual. 2018. In: VITALE, María Alejandra et al. (Org.). Estudios sobre discurso y argumentación. Coimbra: Grácio, 2019. p. 319-338. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTE, Mônica Magalhães; BRITO, Mariza Angélica Paiva. Intertextualidades, heterogeneidades e referenciação. Linha D’Água, São Paulo, v. 24, n. 2, p. 83-100, 2011. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTE, Mônica Magalhães; BRITO, Mariza Angélica Paiva; ZAVAM, Aurea. Intertextualidade e ensino. In: MARQUESI, Sueli Cristina; PAULIUKONIS, Aparecida Lino; ELIAS, Vanda Maria(Org.). Linguística Textual e ensino. São Paulo: Contexto, 2017. p. 109-127. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTE, Mônica Magalhães; FARIA, Maria da Graça dos Santos; CARVALHO, Ana Paula Lima de. Sobre intertextualidades estritas e amplas. Revista de Letras, Araraquara, v. 2, n. 36, p. 7-22, 2017. [ Links ]

FARIA, Maria da Graça dos Santos. Alusão e citação como estratégias na construção de paródias e paráfrases em textos verbo-visuais. 2014. 118 f. Tese (Doutorado em Linguística) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Linguística, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, 2014. [ Links ]

GENETTE, Gérard. Palimpsestos: a literatura de segunda mão. Tradução de Cibele Braga, Erika Viviane Costa Vieira, Luciene Guimarães, Maria Antônia Ramos Coutinho, Mariana Mendes Arruda e Mirian Vieira. Belo Horizonte: Viva Voz, 2010. [ Links ]

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. 4. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2002. [ Links ]

GOLDENBERG, Mirian. A arte de pesquisar: como fazer pesquisa qualitativa em Ciências Sociais. 8. ed.Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2004. [ Links ]